1Department of Nursing, Kang-Ning Junior College of Nursing, Taipei; 2Department of Chest, Veterans General Hospital,

Taipei; 3Department of Psychology, National Taiwan University, Taipei; 4School of Nursing, National Defense Medical

Center, National Defense University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Received: 21 April 2003 Revised: 5 June 2003 Accepted: 2 September 2003

Reprint requests and correspondence to: K.Y. Wang, Associate Professor and Dean, School of Nursing, National Defense Medical Center, National Defense University, No. 161, Section 6, Min-Chuan East Road, Taipei 114, Taiwan.

E

FFECT

OF

M

EDICAL

E

DUCATION

ON

Q

UALITY

OF

L

IFE

IN

A

DULT

A

STHMA

P

ATIENTS

Muh-Lan Yang,1 Chi-Huei Chiang,2 Grace Yao,3 and Kwua-Yun Wang 4

Background and Purpose: Previous studies revealed that many asthma patients did not understand how to manage their disease, which in turn affected their quality of life. This study investigated the effect of asthma education on quality of life in Taiwanese adults with asthma.

Methods: A before and after quasi-experimental design was used. A total of 85 asthma patients were recruited from the asthma clinic of a medical center in northern Taiwan using purposive sampling. Among these patients, 31 were assigned to the experimental group and 54 to the control group. The experimental group received four 1-hour sessions of group education, while the control group received no instruction. Data were collected at 2 different stages: enrollment (baseline), and at 1 month after enrollment. All subjects completed the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire and the Asthma General Knowledge Questionnaire for Adults. Data were analyzed using independent-samples t test and paired t test.

Results: After completing the asthma education sessions, the mean scores on asthma knowledge significantly increased from 19.65 to 23.06 (p < 0.001) in the experimental group. The mean scores for overall quality of life significantly increased from 5.06 to 5.42 (p < 0.01). The mean scores in the symptom domain and the exposure to environmental stimuli domain also significantly increased from 5.07 to 5.46 (p < 0.01) and 4.94 to 5.52 (p < 0.001) after education. However, the mean scores of the control group on the same questionnaire did not change significantly.

Conclusion: Asthma education can significantly improve asthma knowledge and quality of life in adult asthma patients. Key words: Ambulatory care; Asthma education; Outpatient clinic; Patient education; Quality of life

J Formos Med Assoc 2003;102:768-74

Although enormous human and material resources have been spent on asthma treatment and research, asthma mortality is still high, in part because patients lack asthma knowledge and are unable to deal with the attacks.1 Chang et al2 indicated that death caused by asthma attack was common because patients underestimated the severity of the asthma attack and did not understand how to control it. Meeberg noted that medical professionals should not only treat diseases but also acknowledge the importance of the patients’ quality of life.3 The distress and confinement brought about by asthma are impediments to quality of life,4 and enhancing patients’ understanding of asthma and asthma control is an effective strategy for reducing the severity of asthma attacks.

Many studies have shown that medical education of asthma patients can improve asthma symptoms, reduce hospitalization and emergency counseling

times, and lower economic expenditures. Quality of life of asthma patients was often used as the basis for evaluating limitations caused by the disease and evaluating the effect of treatment.5–8 The aim of this study was to determine whether education could be used to improve the quality of life of asthma patients in Taiwan.

M

ethods

Patients

This study used a before and after quasi-experimental design. A total of 85 asthma patients were recruited from the asthma clinic of a medical center in northern Taiwan using purposive sampling. These patients were divided into an experimental group (n = 31) and a control group (n = 54), the control group being of a

larger size to allow for loss of patients to follow-up. Subjects in the experimental group received usual care and completed four 1-hour sessions of group education, while the control group received usual care. The inclusion criteria were as follows: 1) age between 18 and 80 years; 2) asthma diagnosed by physicians in departments of the same hospital; 3) alert mental status and no severe mental or cognitive disorders; 4) no serious impairment of the sense organs confirmed on physical examination and evaluation; 5) ability to communicate in Mandarin or Taiwanese; and 6) literacy. A written, informed con-sent form was obtained from each patient and this study was approved by the hospital review committee after an evaluation of ethical considerations.

Measurements

Patients were asked to complete a personal infor-mation form with questions on gender, age, marital status, level of education, residential status, religion, economic status, first attack of the disease, drug treatment status, and disease severity.

Asthma medical education scheme

The course content was derived from the US National Institutes of Health manual on asthma diagnosis and treatment,9 suggestions of researchers and other health professionals, and the results of a literature survey. The main contents included 4 topics: understanding asthma, self-evaluation and rating of asthma severity, understanding asthma drugs, and self-management. The expert validity of our choices was confirmed by examination. Four pulmonary physicians each taught a 1-hour lesson on each of the 4 topics.

Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire

This study adopted the questionnaire developed by Juniper et al in 1992 based on the characteristics of asthma, also known as the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, to evaluate the effectiveness of medical education.10 The questionnaire had 4 parts: activity limitation, symptoms, emotional function status, and exposure to environmental stimuli. With regard to scoring, this questionnaire had a total of 32 items with a Likert scale score from 1 to 7 for each item. The total score could range from 32 to 224, and the mean score from 1 to 7. The lower the score, the more damage to quality of life. From previous studies, the instrument showed good reliability and validity.11–14 For this study, because this questionnaire had not been used domestically, 5 expert asthma treatment professionals examined and validated the question-naire after translation and reverse translation. Each item of the questionnaire was modified according to advice from each expert. To determine the test

reliability at the stage of pilot study, Cronbach’s alpha was determined using 15 asthma patients. The results were 0.93 for the overall quality of life, 0.75 for activity limitation, 0.91 for symptoms, 0.85 for emotional function status, and 0.37 for exposure to environmental stimuli. At the stage of pre-intervention, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.96 for overall quality of life, 0.89 for activity limitation, 0.93 for symptoms, 0.86 for emotional function status, and 0.76 for exposure to environmental stimuli.

Asthma General Knowledge Questionnaire

for Adults

The level of disease knowledge pre- and post-medical education was evaluated using the Asthma General Knowledge Questionnaire for Adults, a 31-item questionnaire developed by Royal North Shore Hospital.15 The tested contents included the cause of asthma, the pathophysiology of asthma, asthma drugs, evaluation of asthma severity, symptom management, and stimulant control and movement. A dichotomous system was used for scoring this questionnaire, with 1 point counted after answering 1 item correctly, and 0 points counted if the answer was incorrect or un-certain. The maximum score was 31 points. A higher score indicated better asthma knowledge. The test results of Allen and Jones in 1998 showed this questionnaire to be a reliable and valid tool that could be used to evaluate medical education implemen-tation.16 For this study, because use of this question-naire had not been previously reported in research from Taiwan, 5 experienced asthma treatment professionals examined and validated the question-naire after translation and reverse translation. The questionnaire was modified according to the advice of each expert. The Kuder-Richardson 20 (KR20) was used to test reliability and gave a value of 0.75 in a pre-investigation assessment and 0.74 in this study.

The personal information form, the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire, and the Asthma General Knowledge Questionnaire for Adults were collected 1 hour before the course commenced. The course started after the asthma education manuals were distributed, and concluded with a 30-minute discussion that allowed the patients to share their experiences with each other, and for pulmonary physicians to answer patients’ questions. One month after the course, the patients were asked to complete the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire and Asthma General Knowledge Questionnaire for Adults again, at the clinic or at home.

Data were collected from the control group pre-intervention and 1 month after the pre-intervention. Each patient was given a complementary copy of the asthma education manual after completing the program.

Statistical analysis

The data collected in this study were processed and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows version 8.0 computer software package. The results of patient characteristics, asthma knowledge, and asthma quality of life scoring were expressed as percentages or mean ± standard deviation and were analyzed by frequency distribution, chi-squared test, and independent-samples t test. Paired

t test was carried out to evaluate the effect of asthma

education on patients’ quality of life. In addition, analysis of covariance was used to adjust for differences in the basic characteristics of patients. A value of p < 0.05 was taken as the significance level.

R

esults

Patient characteristics

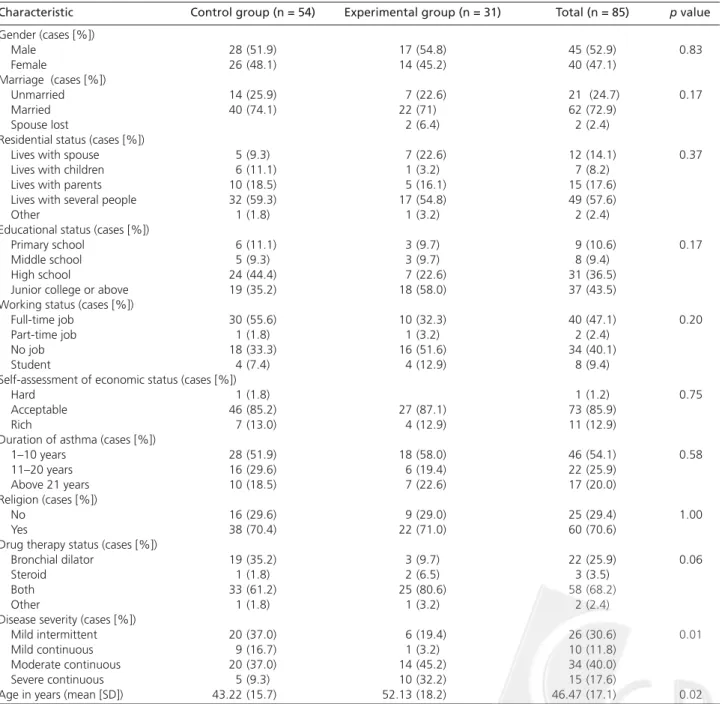

The majority of patients were male, married, had junior college level education or above, lived with several family members, followed a religion, were economically self-supporting, had suffered from asthma for 1 to 10 years, used bronchial dilator and steroid drug therapy simultaneously, and had moderate persistent asthma. The mean age of the patients was 46.5 years.

Comparison of characteristics between the 2 groups was made by chi-squared test and independent-samples

t test. Table 1 shows that there was no significant Table 1. Distribution and comparison of patient characteristics in experimental and control groups.

Characteristic Control group (n = 54) Experimental group (n = 31) Total (n = 85) p value

Gender (cases [%]) Male 28 (51.9) 17 (54.8) 45 (52.9) 0.83 Female 26 (48.1) 14 (45.2) 40 (47.1) Marriage (cases [%]) Unmarried 14 (25.9) 7 (22.6) 21 (24.7) 0.17 Married 40 (74.1) 22 (71) 62 (72.9) Spouse lost 2 (6.4) 2 (2.4)

Residential status (cases [%])

Lives with spouse 5 (9.3) 7 (22.6) 12 (14.1) 0.37

Lives with children 6 (11.1) 1 (3.2) 7 (8.2)

Lives with parents 10 (18.5) 5 (16.1) 15 (17.6) Lives with several people 32 (59.3) 17 (54.8) 49 (57.6)

Other 1 (1.8) 1 (3.2) 2 (2.4)

Educational status (cases [%])

Primary school 6 (11.1) 3 (9.7) 9 (10.6) 0.17

Middle school 5 (9.3) 3 (9.7) 8 (9.4)

High school 24 (44.4) 7 (22.6) 31 (36.5)

Junior college or above 19 (35.2) 18 (58.0) 37 (43.5) Working status (cases [%])

Full-time job 30 (55.6) 10 (32.3) 40 (47.1) 0.20

Part-time job 1 (1.8) 1 (3.2) 2 (2.4)

No job 18 (33.3) 16 (51.6) 34 (40.1)

Student 4 (7.4) 4 (12.9) 8 (9.4)

Self-assessment of economic status (cases [%])

Hard 1 (1.8) 1 (1.2) 0.75

Acceptable 46 (85.2) 27 (87.1) 73 (85.9)

Rich 7 (13.0) 4 (12.9) 11 (12.9)

Duration of asthma (cases [%])

1–10 years 28 (51.9) 18 (58.0) 46 (54.1) 0.58 11–20 years 16 (29.6) 6 (19.4) 22 (25.9) Above 21 years 10 (18.5) 7 (22.6) 17 (20.0) Religion (cases [%]) No 16 (29.6) 9 (29.0) 25 (29.4) 1.00 Yes 38 (70.4) 22 (71.0) 60 (70.6)

Drug therapy status (cases [%])

Bronchial dilator 19 (35.2) 3 (9.7) 22 (25.9) 0.06

Steroid 1 (1.8) 2 (6.5) 3 (3.5)

Both 33 (61.2) 25 (80.6) 58 (68.2)

Other 1 (1.8) 1 (3.2) 2 (2.4)

Disease severity (cases [%])

Mild intermittent 20 (37.0) 6 (19.4) 26 (30.6) 0.01

Mild continuous 9 (16.7) 1 (3.2) 10 (11.8)

Moderate continuous 20 (37.0) 14 (45.2) 34 (40.0) Severe continuous 5 (9.3) 10 (32.2) 15 (17.6)

difference between the 2 groups in gender, marriage, residential status, education level, working status, self-assessment of economic status, period of suffering from asthma, religion, or drug treatment. However, there were significant differences between the 2 groups in age and disease severity. No correlation was found between age and quality of life scores in the 2 groups (correlation coefficient, –0.035 for the experi-mental group and 0.027 for the control group). In addition, 1-way analysis of variance showed no signifi-cant correlation between disease severity and quality of life scores in either group. These results indicate that age and disease severity had no influence on quality of life.

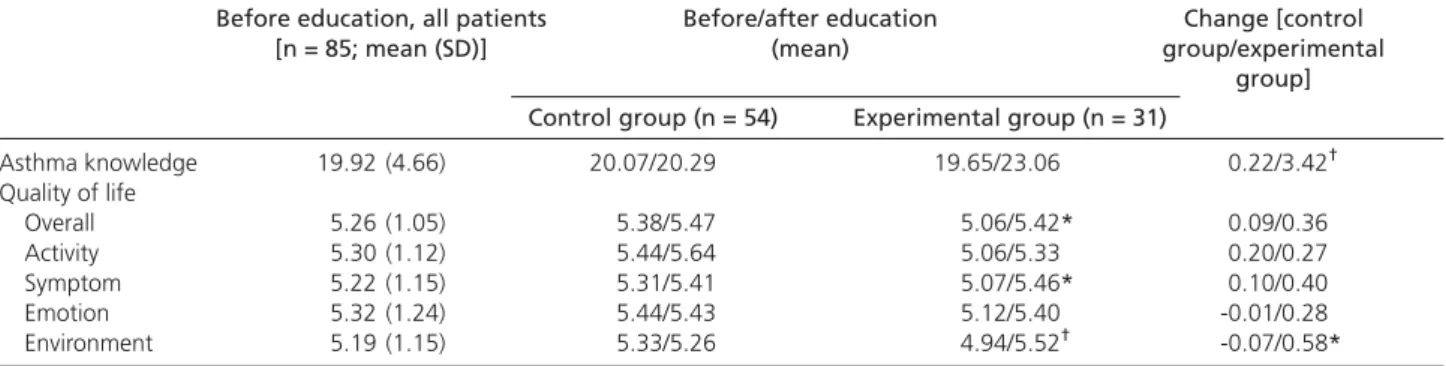

Patient status before asthma education

The mean knowledge score of patients before asthma education is shown in Table 2. The mean overall quality of life score was 5.26 points. Among the 5 aspects of quality of life assessed by the instrument, the highest mean value was the emotional function score of 5.32 points and the lowest mean value was the exposure to environmental stimuli score of 5.19 points (Table 2).

Before asthma education, the asthma knowledge and asthma quality of life scores of the 2 groups were not significantly different (p > 0.05).

After adjusting for age and disease severity, no significant differences on the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire were found overall (F = 1.607, p > 0.05), or in activity limitation (F = 1.679, p > 0.05), symp-toms (F = 0.905, p > 0.05), emotional function status (F = 0.953, p > 0.05), or exposure to environmental stimuli (F = 2.638, p > 0.05). These results indicated that after adjusting for age and disease severity, quality of life scores of the groups were similar before asthma education.

Effect of asthma education on quality of life

Table 2 compares the knowledge and quality of life scores before and after asthma education. The

asthma knowledge, overall asthma quality of life, symptoms, and environmental exposure to stimuli scores of the experimental group changed signifi-cantly following asthma education, while these scores did not change in the control group (p > 0.05). The mean difference of the asthma knowledge and exposure to environmental stimuli scores was signifi-cantly different between the 2 groups. After asthma education, no significant difference was found between the 2 groups in general scores, and scores for activity limitation, symptoms, and emotional function (p > 0.05).

After adjusting for the factors of age and disease severity, Asthma Quality of Life scores overall (F = 2.697,

p > 0.05), and for activity limitation (F = 0.211, p > 0.05),

symptoms (F = 1.736, p > 0.05) and emotional function scores (F = 2.671, p > 0.05) did not significantly change after asthma education for both groups, while the exposure to environmental stimuli score improved in the experimental group (F = 11.140, p < 0.01).

D

iscussion

In the experimental group of this study, the mean knowledge score prior to asthma education was 19.92 points, which was lower than that (25.5 points) obtained by Allen and Jones in 1995 using a similar Asthma General Knowledge questionnaire for adult asthma.17 Possible reasons for this difference might be related to cultural background, value systems, and health beliefs. Such differences would likely affect the motivation for acquiring related disease infor-mation. With regard to quality of life scores, the patients’ mean score before the experiment was 5.26 points, which was similar to the results reported by some studies.11,13,18–20 However, the results for mean score in this study were higher than in previous studies.21,22 A possible reason might be that this study included patients with mild to severe disease. In addition, these patients had not been hospitalized Table 2. Comparison of asthma knowledge and quality of life questionnaire scores between experimental and control

groups before and after asthma education.

Before education, all patients Before/after education Change [control [n = 85; mean (SD)] (mean) group/experimental

group] Control group (n = 54) Experimental group (n = 31)

Asthma knowledge 19.92 (4.66) 20.07/20.29 19.65/23.06 0.22/3.42† Quality of life Overall 5.26 (1.05) 5.38/5.47 5.06/5.42* 0.09/0.36 Activity 5.30 (1.12) 5.44/5.64 5.06/5.33 0.20/0.27 Symptom 5.22 (1.15) 5.31/5.41 5.07/5.46* 0.10/0.40 Emotion 5.32 (1.24) 5.44/5.43 5.12/5.40 -0.01/0.28 Environment 5.19 (1.15) 5.33/5.26 4.94/5.52† -0.07/0.58* *p < 0.01, †p < 0.001.

recently for acute asthma attack or deterioration, and so would be expected to have higher quality of life scores than patients recently hospitalized for acute asthma attack, patients visiting the emergency department, and patients with moderate to severe asthma.

Asthma knowledge scores of the experimental group increased by an average of 3.42 points (p < 0.05), while those of the control group did not change significantly. This result is similar to some previous studies.17,23–26 In addition, the change in knowledge scores in this study was significantly different between the 2 groups, unlike the results of a study by Abdulwadud et al.27 Differences in the time elapsed between education and scoring in the 2 studies, which was 6 months after education in the study of Abdulwadud et al27 and 1 month in this study, might have affected the results. While the 1-month interval after education in this study was short enough for patients to remember the educational content clearly, it appears to have been too short for control patients to improve their knowledge.

Regarding asthma quality of life, the mean symp-tom scores of experimental patients after education changed significantly after education, while those of the control group did not. This result is similar to some previous studies.28–31 Similar to our results, Kotses et al29 found that symptoms experienced by asthma patients (including wheezing, dyspnea, chest tightness, and coughing) declined significantly after asthma education, while no significant decrease was experienced by control patients. In addition, Synder et al showed that asthma symptoms improved after asthma education, and asthma attacks recurred significantly less often,30 results also identical to this study. Wilson et al showed that the number of days asthma symptoms lasted was significantly reduced after education,31 which also is consistent with this study. These studies indicate that asthma education can improve disease status and reduce the occurrence of asthma symptoms.

With regard to the exposure to environmental stimuli, both this study and that by Wilson et al31 showed significant improvement after asthma edu-cation. After taking the course, asthma patients made greater attempts to control their environment and avoid allergen contact, thus reducing the frequency and severity of allergen contact and exposure, and thereby reducing the number of asthma attacks. In the study of Huss et al,32 allergen prevention and treatment were provided to asthma patients as a part of their medical education course, and the results showed that the symptoms of asthma were improved by self-management. These results agree with those of our study, indicating that effective prevention and

treatment behavior can be implemented by patients, thus reducing the number of asthma attacks after instruction on prevention and treatment.

Wilson et al31 showed that patients felt that physical activity was less limited 5 months after completing their asthma education course. Moreover, Osman et al33 showed that patients were less frequently interrupted when sleeping at night, and activity limitation during the day also significantly decreased 12 months after asthma education. Although in this study activity limitation was also decreased after asthma education, this decrease did not reach signifi-cance, which might have been related to differences in the interval between education and assessment. In this study, the assessment was done 1 month after asthma education, and asthma patients might require longer times to adjust their activity patterns. Regarding emotional function status, Jenkinson et al34 found that 12 months after asthma education, the feelings of disability among attendees were significantly re-duced. In addition, Wilson et al31 showed that asthma symptoms were significantly improved 12 months after group medical education in adults with moderate to severe asthma. The study of Kotses et al29 showed that while feelings of disability were reduced 1 to 2 months and 5 to 6 months after asthma education, they were significantly reduced 5 to 6 months after education, and more confidence was gained in the self-management of asthma. However, quality of life 1 to 2 months after education did not improve significantly, indicating that a relatively longer period of time may be necessary before improvement in emotional function is apparent. In this study, emotional function scores increased, though not significantly.

With regard to quality of life of the patients in the 2 groups, the change in exposure to environmental stimuli score reached significance, but quality of life in general and other aspects of quality of life scores were not significantly different. These results were somewhat different from 3 previous studies27,35,36 which showed that changes in quality of life scores were not significantly different after asthma education. These differences might have been due to the timing of assessment of quality of life after education, and a longer follow-up period might have revealed a greater effect. In our study, the control group had significantly higher mean quality of life scores in general and in all aspects of quality of life before education than the experimental group. These mean quality of life scores increased after the asthma education such that they were not significantly different between the 2 groups. However, the scores for exposure to environmental stimuli increased significantly only in the experimental group.

Because asthma is greatly influenced by external environment and climate, generalization of these results to all asthma patients should be done cautious-ly. The disease severity among our subjects varied considerably and future studies are needed with patients having disease of more specific severity. In addition, in this study, patients were recruited by purposive sampling and this may have resulted in bias. Random assignment should be used to control deviation between groups in future study. Owing to limitations on personnel and time, a 4 × 1-hour session program was adopted in this study. Future studies involving individual or small group instruction with medical education continued for several weeks would allow the influence of the number of participants and time of instruction on quality of life to be evaluated. In addition, because resources and time were limited, we only tested 1 month after asthma education was completed, and the long-term effect of medical education was not evaluated. Future studies involving long-term follow-up could provide useful information on the long-term effect of asthma medical education on disease control and quality of life.

R

eferences

1. Gianaris P, Golish JA: Changing strategies in the management of asthma. Postgrad Med 1994;95:105-9.

2. Chang KY, Jou HL, Lin JS, et al: The old friend – review of asthma.

Taiwan Medical Journal 1995;38:55-62. [In Chinese].

3. Meeberg GA: Quality of life . A concept analysis. J Adv Nurs 1993;18:32-8.

4. Quirk FH, Jones PW: Patient’s perception of distress due to symptoms and effects of asthma on daily living and an investigation of possible influential factors. Clin Sci 1990;79: 17-21.

5. Bousquet J, Knani J, Dhivert H, et al: Qualtiy of life in asthma.

Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994;149:371-5.

6. Jones PW: Quality of life, symptoms and pulmonary function in asthma: long-term treatment with nedocromil sodium examined in a controlled multicentre trial. The Nedocromil Sodium Quality of Life Study Group. Eur Respir J 1994;7:55-62.

7. Lawrence G: Asthma self-management programs can reduce the need for hospital-based asthma care. Respir Care 1995; 40:39-43.

8. Reynolds D, Ward C: Intensive training. Nurs Times 1994;90: 46-7.

9. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma. National Institutes of Health Pub No 97-4051. Bethesda, MD, 1997.

10. Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Epstein RS, et al: Evaluation of impairment of health related quality of life in asthma: Development of questionnaire for use in clinical trials. Thorax 1992;47:76-83. 11. Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Ferrie PJ, et al: Measuring quality of life

in asthma. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;147:832-8.

12. Rowe BH, Oxman AD: Performance of an asthma quality of life questionnaire in an outpatient setting. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993; 148:675-81.

13. Leidy NK, Coughlin C: Psychometric performance of the asthma quality of life questionnaire in a US sample. Qual Life Res 1998; 7:127-34.

14. Oga T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, et al: Comparison of responsiveness of different disease-specific health status measures in patients with asthma. Chest 2002;122:1228-33. 15. Browne G: Asthma education handbook. Royal North Shore

Hospital, Sydney, Australia, 1986.

16. Allen RM, Jones MP: The validity and reliability of an asthma knowledge questionnaire used in the evaluation of a group asthma education self-management program for adults with asthma. J Asthma 1998;35:537-45.

17. Allen RM, Jones MP, Oldenburg B: Randomized trial of an asthma self-management programme for adults. Thorax 1995;50: 731-8.

18. Juniper EF, Buist AS, Cox FM, et al: Validation of a standardized version of the asthma quality of life questionnaire. Chest 1999; 115:1265-70.

19. Gibson PG, Talbot PI, Toneguzzi RC, et al: Self-management, autonomy, and quality of life in asthma. Chest 1995;107: 1003-8.

20. Rutten-van M, Custers F, Dooslaer EK, et al: Comparison of performance of four instruments in evaluating the effects of salmeterol on asthma quality of life. Eur Respir J 1995;8: 888-98.

21. Blixen CE, Tilley B, Havstad S, et al: Quality of life, medication use, and health care utilization of urban African Americans with asthma treated in emergency departments. Nurs Res 1997;46: 338-41.

22. Apter AJ, Reisine ST, Barrows E, et al: The influence of demographic and socioeconomic factors on health related quality of life in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1999;103:72-8. 23. Wigal JK, Stout C, Brandon M, et al: The knowledge, attitude,

and self-efficacy asthma questionnaire. Chest 1993;104:1144-8. 24. Garrett J, Fenwick JM, Taylor G, et al: Prospective controlled evaluation of the effect of a community based asthma education centre in a multiracial working class neighbourhood. Thorax 1994;49:976-83.

25. Hilton S, Anderson H, Sibbald B, et al: Survey: controlled evaluation of the effect of patient education on asthma morbidity in general practice. Lancet 1986;1:26-9.

26. Rinsberg KC, Wiflund I, Wilhelmsen L: Education of adult patients at an asthma school: effects on quality of life, knowledge and need for nursing. Eur Respir J 1990;3:33-7.

27. Abdulwadud O, Abramson M, Forbes A, et al: Evaluation of a randomized controlled trial of adult asthma education in a hospital setting. Thorax 1999;54:493-500.

28. Moudgil H, Marshall T, Honeybourne D: Asthma education and quality of life in the community: a randomized controlled study to evaluate the impact on white European and Indian subcontinent ethnic groups from socioeconomically deprived

areas in Birmingham. Thorax 2000;55:177-83.

29. Kotses H, Bernstein I, Bernstein D, et al: A self-management program for adult asthma. Part 1: development and evaluation.

J Allergy Clin Immunol 1995;95:529-40.

30. Snyder SE, Winder JA, Creer TJ: Development and evaluation of an adult asthma self-management program: wheezers anonymous. J Asthma 1987;24:153-8.

31. Wilson SR, Scamagas P, German DF, et al: A controlled trial of two forms of self-management education for adults with asthma. Am J Med 1993;94:564-76.

32. Huss K, Salerno M, Huss RW: Computer-assisted reinforcement of instruction: effects on adherence in adult atopic asthmatics.

Res Nurs Health 1991;14:259-67.

33. Osman LM, Abdalla MI, Beattie JAG, et al: Reducing hospital admission through computer supported education for asthma patients. BMJ 1994;308:568-71.

34. Jenkinson D, Davison J, Jones S, et al: Comparison of effects of a self management booklet and audiocassette for patients with asthma. BMJ 1988;297:267-70.

35. Kauppineu R, Sintonen H, Vilkka V, et al: Long-term (3-year) economic evaluation of intensive patient education for self-management during the first year in new asthmatics. Respir

Med 1999;93:283-9.

36. Perneger TV, Sudre P, Muntner P, et al: Effect of patient education on self-management skills and health status in patients with asthma: a randomized trial. Am J Med 2002;113:7-14.