行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 期中進度報告

奇數訂價對消費者行為影響之研究:消費者注意、價格處

理、及購買效果(1/2)

計畫類別: 個別型計畫 計畫編號: NSC91-2416-H-004-004- 執行期間: 91 年 08 月 01 日至 92 年 07 月 31 日 執行單位: 國立政治大學企業管理學系 計畫主持人: 樓永堅 共同主持人: 別蓮蒂 報告類型: 精簡報告 處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 92 年 6 月 2 日

The Research Program of the Impact of Odd Pricing on

Consumer Behavior: Attention, Processing, and Purchasing

奇數訂價對消費者行為影響之研究:消費者注意、價

格處理、及購買效果(1/2)

Lou, Yung-Chien Bei, Lien-Ti

ABSTRACT

A price with right-most digit nine is the most frequent pricing strategy when promoting products. Therefore, a general assumption concerning the effects of odd pricing has been that 9-ending price can effectively attract buyers’ attentions and further prompt them to engage purchase behavior. However, two experiments employed in this article discovered that 9-ending price seemed not to significantly attract Taiwanese consumers’ attention, and this insignificant attention getting effect appeared in different price lengths. The present research has important implications for models of consumers’ processing of 9-ending price information and provides a basis for a cross-cultural extension of comprehensive models of information processing in odd pricing.

中文摘要

廠商促銷商品時,9 尾數的訂價策略可謂為最普及的方式,因此,在奇數定 價影響之理論中,普遍認定 9 尾數的價格可有效的吸引購買者的注意力,並且進 一步刺激其做出購買決策。然而,本計畫目前完成的兩個主要的實驗均顯示 9 尾數的價格似乎並沒有顯著地吸引台灣消費者的注意力;同時,對於不同的價格 長度,9 尾數亦無造成顯著的不同。本研究對於台灣地區的消費者處理 9 尾數之 價格資訊有一重要的方向,並為奇數定價之資訊處理模式提供一跨文化性的衍 生。Keywords: Odd Pricing, Consumer Perception, Just Noticeable Difference Threshold, symbolic meanings

OBJECTIVE

Even though a large number of studies have demonstrated the significant popularity of the 9-ending prices among retailers, and its effectiveness on consumers’ price memory, on sales, and on symbolic meanings, they were exclusively implemented in western culture. Also, the first stage of consumers’ process of the price information, perceiving or getting attention was neglected. Therefore, the purpose of this research is to systematically examine how individuals in an eastern Asian culture respond to 9-ending prices, especially how they devote their attention to the odd prices.

THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS

Adopting odd digit 9 as right-most price-ending digit is a common way for product promotion, and the end of promotion is to encourage consumers’ purchase behaviors. According to AIDA model, shoppers process price information from Attention, Interest, Desire, and Action (Philips, 1997). In this article, we focus on the first stage in price processing procedure to examine the attention getting effect off odd digit 9 as right-most price-ending digit.

At the attention getting stage, consumers are attracted by marketing approaches, e.g. seller promoting, broadcasting in store, POP, or bright color (Lamd, Hair, and McDaniel, 1996). Therefore, the odd digit pricing method, using digit 9 as right-most price-ending digit, is a marketing promotion way to attract consumers’ attention. Moreover, when shoppers entering a store, the environment make them have selective attention (Mowen and Minor, 1998), and repeated information help them build awareness and accumulate knowledge (Naipaul and Parsa, 2001); therefore, highly repeated information more easily accounts for attention getting effects (Lamd, Hair, and McDaniel, 1996). Based on the observation of a previous research, 9 is the most frequent price-ending digit (Lou, Yung-Chien, 1999) adopted by retail merchants. Thus, we hypothesize as following:

H1: Products with digit 9 as the right-most price-ending digit get more attention than those with the digit 0.

between two similar stimuli (Mowen and Minor, 1998), also influences shoppers’ judgments toward prices during the process of selective attention. Weber’s Law further interpreted the different perceptions of changes from different price lengths. Weber’s Law suggests that the JND varies in direct proportion to the size of the stimulus, so that the stronger the stimuli the more incident stimuli should be added to identify difference. The formula of JND can be presented as JND = I*K, I is Intensity of stimuli, and K is a constant. Applied to the pricing strategy, I represents regular price, and K represents the percentage of discount, so JND is the minimum value of price changes perceived by shoppers. Additionally, as the number of price digits increases, the frequency of prices with digit 9 as right-most price-ending digit decreases (Lou, Yung-Chien, 1999). Therefore, shoppers’ selective attention decreases as the frequency of price-ending digit 9 decreases while intensity of stimulus decreased followed with the increase of price digits. These led to make the second hypothesis:

H2: The digit 9 as the right-most price-ending digit derives more attention getting in prices with short digit length than with long digit length.

From classical conditioning reasoning, attention toward 9-ending price could be aroused by the association of 9-ending price and on-sale information. A match between a stimulus and a preattentively primed memory representation could make the attention effect more significant (Ohman 1979). Therefore, the effects of on-sale tag will be examined in experiment 2 to test whether reinforce the 9-ending prices’ attraction or generate more attention than those prices without on-sale tag. That is, in addition to hypotheses 1 and 2, the relevant hypothesis is:

H3: Products with 9-ending price and on-sale tag get more attention than those prices without on-sale tag.

EXPERIMENTAL METHOD & RESULTS

Experiment 1 To prove our hypothesis, two experiments are designed to assess

whether products with the digit 9 as the right-most digit in price get more attention than those with the digit 0 do and whether or not the 9-ending price derives more attention in short digit prices than in long-digit prices.

In the first experiment, a 2 (price-ending digit [9] vs. [0]) 3 (price lengths: 2, 3, and 4 digits) within-subjects factorial design is used and placed in a virtual store.

Focus group, one pretest and series of pilot studies are conducted to select manipulative objects and to modify the layout and design of virtual store to be viewed and shopped as a user-friendly Internet store for the main study. The principle of experiment 1 is to reflect a true virtual store and shopping environment through providing all related information, including prices, brands, models, product descriptions and pictures. Six product categories, CD player, desk lamp, umbrella, fan, battery, and refill were selected for this survey based on the former pretest and pilot studies.

Thirty-eight college students took part in experiment 1. The significant results were found in the tests of brands’ preference and purchase intention for umbrella and CD player. In addition, the effects of product types were interacted with price endings and price length on the attention. The source of product effect was refill. Thus, the data of umbrella, CD player, and refill were eliminated from further analysis.

The results of main study were thus based on the data of desk lamp, fan, and battery. As presented in Table 1, there was no significant difference in the frequency of selecting 9-ending prices. Although items with 9-ending prices were clicked more often for product descriptions, the magnitudes of the distribution difference were not clear enough. The attention getting effect was not supported. However, 9-ending price seemed to have a positive effect on respondents’ purchase intention at marginally significant level (2=3.51, p=0.06).

TABLE 1. Frequencies of Chosen Prices with Ending Digit in 0 or 9

First Click Two Clicks Purchase Decision

frequency percentage frequency percentage frequency percentage

Prices ending in 9 65 57% 119 52% 67 59%

Prices ending in 0 49 43% 109 48% 47 41%

Total 114 100% 228 100% 114 100%

2=2.25 p=.13 2=.44 p=.50 2=3.51 p=.06

Note: Each subject had three answers from three test product categories as first choice and contributed six answers as all of their choices.

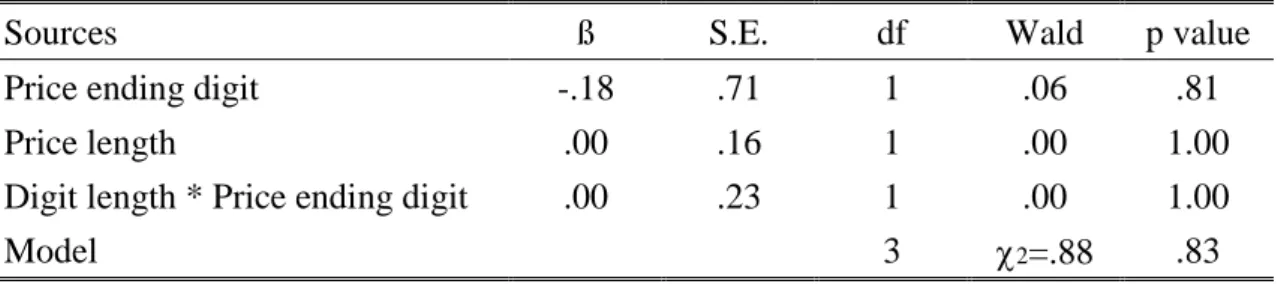

From the results for the attention getting effect of 9-ending prices shown in Table 2, none of the main effect of price ending or price length or the interaction was significant. According to these results, 9-ending prices could not get significantly more attention while respondents were shopping in the virtual store. The effect of 9-ending price was not extinguishing with the length of price either. Both hypotheses

1 and 2 were not supported in this experiment.

TABLE 2. The Influences of Price Ending and Price Length on 9-ending Prices’ Attention Getting Effects (Two Clicks)

Sources ß S.E. df Wald p value

Price ending digit -.18 .71 1 .06 .81

Price length .00 .16 1 .00 1.00

Digit length * Price ending digit .00 .23 1 .00 1.00

Model 3 2=.88 .83

Experiment 2 In addition to the hypotheses tested in Experiment 1, Experiment 2,

employed by two stages, also examines the effects of on-sale tag, whether reinforce the 9-ending prices’ attraction or generate more attention than those prices without on-sale tag. Price information is the only stimulus in this design to magnify the effect of a 9-ending price. Two boxes with price labels are set up for respondents’ choices to assess consumers’ attention. A 2 (price-ending digit [9] vs. [0]) 3 (price lengths: 2, 3, and 4 digits) 2 (with on-sale tag or without) between-subjects experimental design is used in Experiment 2.

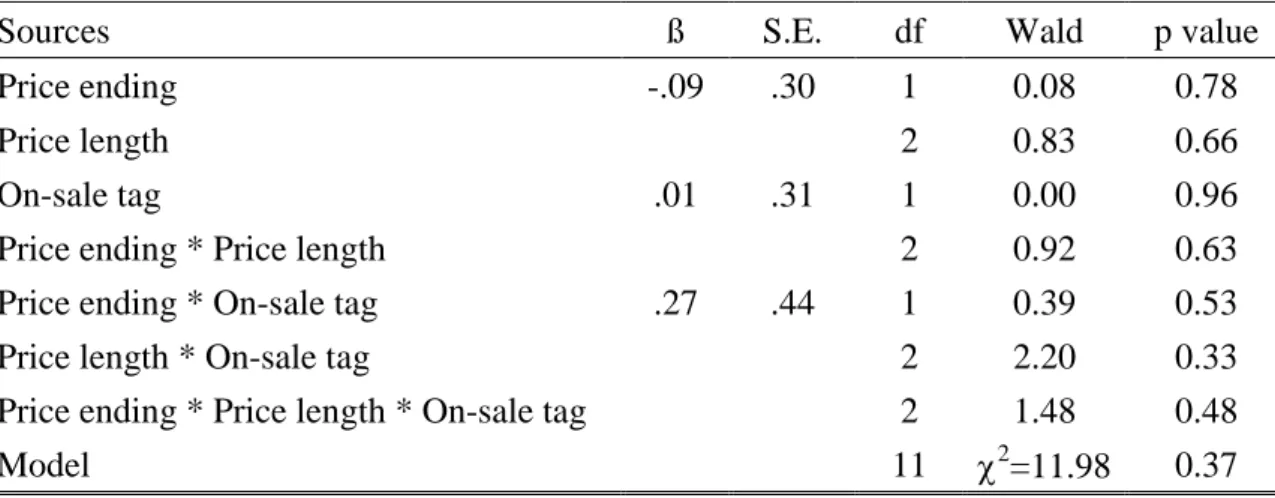

In Stage 1, 363 undergraduate students participated in this experiment. There were 30 or 31 subjects in each cell. In Table 3, the model is insignificant (2

=11.98, p=.37). None of the main effect or interaction effect was significant. In Table 4, it is seen that 60% of the respondents in the 0-ending price group selected the 0-ending ones (i.e., 100, 500, and 1000) over the reference price ones (i.e., 110, 550, and 1100); while 61% of the respondents in the 9-ending price group chose the 9-ending ones (i.e., 99, 499, and 999) over the reference price ones. The 1% gap made no statistical differences on getting respondents’ attentions, so, H1 was then not supported. The same, there was no interaction effect to support H2 that 9-ending prices’ attention getting effect would be stronger in short prices than in long prices. On-sale tag had no influence on attention getting either or help 9-ending prices with attention getting.

Some extra findings were discovered regarding to respondents’ attitudes toward selected products. The three-way interactions of 2*3*2 ANOVA results were significant for product quality evaluation (F(2)=3.14, p=.04) and product preference (F(2)=2.71, p=.07) (also shown in Figures 2 and 3). Basically, 2-digit 9-ending (i.e., $99) with on-sale tag and 0-ending without on sale ($100) were better than $99 without on-sale and $100 on sale. It could be explained that an on-sale price $100 was not attractive and not cheap, but respondents might infer a product on sale for $99 was

much better or worth much more than $99. Also, respondents tended to think the quality of $500 products were superior to $499 products. However, they preferred products that marked $499 not on sale or $500 on sale. For the highest pair of prices, the product quality without on-sale tag was better than with on-sale tag on. When it was priced $999, no on-sale tag was more preferable. It seemed that $499 or $999 itself was a symbol of “on-sale.” The special sale mark with 9-ending price together might cause the inference that the product was inferior. On the other hand, while the product was really some trivial items, “on-sale for $99” might provide a “great deal” or “good bargain” image for respondents. The symbolic effects of a 9-ending price (Schinder 1991) need to be further studied in Taiwan.

TABLE 3. The Influences of Price Ending, Price Length, and On-Sale Tag on 9-ending Prices’ Attention Getting Effects

Sources ß S.E. df Wald p value

Price ending -.09 .30 1 0.08 0.78

Price length 2 0.83 0.66

On-sale tag .01 .31 1 0.00 0.96

Price ending * Price length 2 0.92 0.63

Price ending * On-sale tag .27 .44 1 0.39 0.53

Price length * On-sale tag 2 2.20 0.33

Price ending * Price length * On-sale tag 2 1.48 0.48

Model 11 2=11.98 0.37

TABLE 4. The Distribution of Price Selection under Each Condition

Price ending Price length On-sale tag

0-ending 9-ending 2-digit 3-digit 4-digit w on-sale tag w/o on-sale tag Valid N= 180 183 79 60 81 183 180 Reference price 40% 39% 38% 50% 49% 41% 38% Test price 60% 61% 41% 50% 51% 59% 62%

In our first focus group discussion by household wives before the two experiments, half of the participants expressed that they were strongly attracted by 9-ending price signs in a marketplace. We would like to know if college students’ price consciousness might be lower than household wives might. Therefore, another similar experiment was run on both college students and women who were main

shoppers in households next.

Stage 2 replicated the same experimental method and procedures but showed price labels of NT $100 and NT $99 together as a pair outside the boxes. The result of the student group showed no significant difference between the chosen rate of NT $100’s box (39%) and NT $99’s box (61%) with 2=1.58 (p>.20). However, the result of woman group expressed a different attitude toward these two prices, where $100 ($70%) elicited significantly higher attraction than $99 (30%) (2

=4.8, p<.03), an opposite pattern from previous assumption. Therefore, the price consciousness issue was not related to attention.

CONCLUSION

Consistent results from both experiments showed that products with 9-ending prices do not effectively attract respondents’ attention or generate different reactions in three price lengths in Taiwan. The reason may be due to the popularity of 9-ending prices among retailers in Taiwan; therefore, Taiwanese consumers may accumulate enough knowledge from previous shopping experience to rationally judge the relationship between price and product quality. Thereby, multinationals need to redesign their pricing presentation when marketing to consumers in different cultures. The findings even reveal that some consumers express negative attitudes toward the products with 9-ending prices when a 9-ending price is combined with an on-sale tag in a long price.

However, there are also some findings in our experiment designs deserves further discussions. In the virtual store design of Experiment 1, it seems to decrease respondents’ motivations for concerning about money and prices from two perspectives. First, respondents are not price conscious in a virtual shopping environment as they usually do, so they do not reflect their attentions on the clicking behaviors. In addition, respondents make the decisions of clicking based mainly on the brands or their previous experiences; thus, the product information provided in the virtual store seems too much to reveal the importance of prices in Experiment 1. On the contrary, price information is over-interpreted by the respondents in the Experiment 2; their price choices are based on the cognition of previous shopping experience instead of their first impression toward the price stimuli.

Based on the strongly insignificant results of these two experiments, a general conclusion is drawn that 9-ending price is not so attractive to consumers due to the

fatigue effect of over-usage of 9-ending prices in Taiwan’s market. Retailers are suggested to consider other odd-prices, such as 6-ending or 7-ending, that may create more attention getting effect. However, more researches are needed before fully concluding the no effect of 9-ending and better effects of other right-most digits. Attention happens within a snap and represents a short moment of perception status. Learning from this study, the response time is a critical issue in experiment design. Also, there are so many factors may contribute to consumers’ focuses of attentions. It is suggested that further research may assess this topic with a different research design that can reflect attention status more precisely. It will also be interesting to examine if a 9-ending price has an attention getting effect in a western culture.

REFERENCES

Bader, Louis and James D. Weinland (1932), “Do Odd Prices Earn Money,” Journal of Retailing, 8 (January), 102-104.

Berry, John W., Ype H. Poortinga, Marshall H. Segall, and Pierre T. Dasen (1992), Cross-Cultural Psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Blattberg, Robert C. and Scott A. Neslin (1990), Sales Promotion, Concepts, Methods and Strategies, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Byrd, Gary R., Shirley Morgan Paige, Gary W. Guyot, and Vicki Heck (1990), “Performance of Field-Dependent and Field-Independent Subjects on a Rod and Frame Discrimination Task,” Perceptual and Motor Skills, 70 (June), 1089-1092. Dalyrimple, Douglas J. and George H. Haines, Jr. (1970), “A Study of the Predictive Ability of Market Period Demand-Supply Relations for a Firm Selling Fashion Products,” Applied Economics, 1(4), 277-285.

Gabor, Andre and Clive Granger (1964), “Price Sensitivity of the Consumer,” Journal of Advertising Research, 4 (December), 40-44.

Georgoff, David M. (1972), Odd-Even Retail Price Endings, East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University, pp.4-6; pp.183

Ginzberg, Eli (1936), “Customary Pricing,” American Economic Review, 26 (June), 296.

Hawkins, Edward R. (1954), Price Policies and Theory,” Journal of Marketing, 18 (January), 233-240.

Helgeson, Jams G. and Sharon E. Beatty (1987), “Price Expectations and Price Recall Error: An Empirical Study,” Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (December), 379-386.

Knauth, Oswald (1949), “Considerations in Setting Retail Prices,” Journal of Marketing, 14 (July), 1-12.

Kotler, Philip and Armstrong (1996), “Promoting Products: Marketing Communication Strategy,” in Principles of Marketing, 7th Ed., Prentice Hall International Editions.

Labmert, Zarrel V. (1975), “Perceived Prices as Related to Odd and Even Price Endings,” Journal of Retailing, 51 (Fall), 13-22, 78.

Lamb, Charles W. Jr., Joseph F. Jr. Hair, and Carl McDaniel (1996), Marketing, 3rd Ed., Ohio: South-Western College Publishing.

Lou, Yung-Chien (1999), Symbolic Meaning of Prices’ Rightmost Digit: The Analysis of Odd Pricing, Taipei: Hua-Tai Publishing.

Mason, J. Barry and Morris L. Mayer (1990), Modern Retailing: Theory and Practice, Homewood, IL: BPI/Irwin.

Mazumdar, Tridib and Kent B. Monroe (1990), “The Effects of Buyers’ Intentions to Learn Price Information on Price Encoding.” Journal of Retailing, 66(Spring), 15-32.

Monroe, Kent B. and Lee, Angela Y. (1999), “Remembering Versus Knowing Issues in Buyers’ Processing of Price Information”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Volume 27, No.2, 207-225.

Mowen, John C. and Minor, Michael (1998), Consumer Behavior, 5th Ed., New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Naipaul, Sandra and H. G. Parsa (2001), “Menu Price Endings That Communicate Value and Quality”, Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, February, 26-37.

Negle, Thomas T. (1987), The Strategy and Tactics of Pricing: A Guide to Profitable Decision Making, Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Pretice-Hall.

Powell, Christine P. (1985), “An Experimental Investigation of Recognition as a Measure of Price Awareness,” Unpublished master’s thesis, Department of Marketing, Virginal Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksnurg, VA. Segall, Marshall H., Donald T. Campbell, and Melville J. Herskovits (1963),

"Cultural Differences in the Perception of Geometric Illusions," Science, 139 (February), p. 769-771.

Schindler, Robert M. (1991), “Symbolic Meanings of a Price Ending,” in Advances in Consumer Research, 18, Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, 794-801.

--- and Thomas Kibarian (1996), “Increased Consumer Sales Response through Use of 99-Ending Prices,” Journal of Retailing, 72 (2), 187-199.

--- and Patrick N. Kirby (1997), “Patterns of Rightmost Digits Used in Advertised Prices: Implications for Nine-Ending Effects,” Journal of Consumer Research, 24 (September), 192-201.

--- and Alan R. Wiman (1989), “Effect of Odd Pricing on Price Recall,” Journal of Business Research, 19 (November), 165-177.

--- and Lori S. Warren (1988), “Effect of Odd Pricing on Choice of Items from a Menu,” in Advances in Consumer Research, 15, ed. Michael J. Houston, Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, 348-353.

Simon, Hermann (1989), Price Management, Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier.

Stiving, Mark and Russell S. Winer (1997), “An Empirical Analysis of Price Endings Using Scanner Data,” Journal of Consumer Research, 24 (June), 57-67.

Solomon, Michael R. (1999) “Perception,” in Consumer Behavior, 4th Ed., Prentice Hall International.

Twedt, Dik Warren (1965), “Does the ‘9 Fixation' in Retail Pricing Really Promote Sales?” Journal of Marketing, 29 (October), 54-55.

Zeithamel, Valarie A. (1981), “Encoding of Price Information by Consumers: An Empirical Test of the Levels of Processing Framework,” In The Changing Marketing Environment: New Theories and Application, Eds. Kenneth Bernardt, Ira Dolich, Michael Etzel, William Kehoe, Thomas Kinnear, William Perreault Jr., and Kenneth Roering Chicago: American Marketing Association, 189-192.

SELF-EVALUATION

1. Accomplishment Schedule

In the first term of this study from August 1st, 2002 to July 31, 2003, we plan to investigate whether the right-most digit nine can get more attention than digit 0 by experiments. Three experiments have been designed to examine our hypotheses. We have finished two experiments and are focusing on the third one. One pretest and three pilot studies for the third experiment had been exerted. The main study of the third experiment is scheduled to implement at the mid June by over 150 undergraduate students. Therefore, we meet our schedule by an impressive pace.

2. Value for academic or pragmatic usage

As our research objective, the research results for the effect of the 9-ending prices are fruitful in western culture. Also, adopting odd digit 9 as right-most price-ending digit is a common way for product promotion in Taiwan. However, there is no academic basis to support the 9-ending prices is effective to Taiwan market. This research has important implications for models of consumers’ processing of 9-ending price information and provides a basis for a cross-cultural extension of comprehensive models of information processing in odd pricing.

3. Suitability for academic journal or patent

This paper has been submitted to the 2003 ACR conference.

4. Major finding

- 9-ending price is not so attractive to consumers due to the fatigue effect of over-usage of 9-ending prices in Taiwan’s market.

- Some consumers express negative attitudes toward the products with 9-ending prices when a 9-ending price is combined with an on-sale tag in a long price.