Factors Associated with Peptic Ulcer in Taiwan:A case-control study

全文

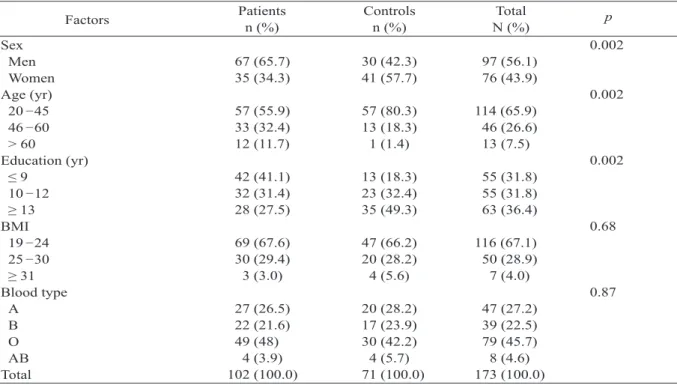

(2) 2. Factors Associated with Peptic Ulcer Disease. Table 1. Comparison of socio-demographic factors between patients and controls Patients Controls Total Factors n (%) n (%) N (%) Sex 67 (65.7) 30 (42.3) 97 (56.1) Men 35 (34.3) 41 (57.7) 76 (43.9) Women Age (yr) 57 (55.9) 57 (80.3) 114 (65.9) 20 45 33 (32.4) 13 (18.3) 46 (26.6) 46 60 12 (11.7) 1 (1.4) 13 (7.5) > 60 Education (yr) 42 (41.1) 13 (18.3) 55 (31.8) ≤9 32 (31.4) 23 (32.4) 55 (31.8) 10 12 28 (27.5) 35 (49.3) 63 (36.4) ≥ 13 BMI 69 (67.6) 47 (66.2) 116 (67.1) 19 24 30 (29.4) 20 (28.2) 50 (28.9) 25 30 3 (3.0) 4 (5.6) 7 (4.0) ≥ 31 Blood type 27 (26.5) 20 (28.2) 47 (27.2) A 22 (21.6) 17 (23.9) 39 (22.5) B 49 (48) 30 (42.2) 79 (45.7) O 4 (3.9) 4 (5.7) 8 (4.6) AB 102 (100.0) 71 (100.0) 173 (100.0) Total BMI = body mass index (kg/m2).. Therefore, this study investigated the socioeconomic and lifestyle factors that may be associated with peptic ulcer disease among adults in Taiwan. MATERIALS AND METHODS. We conducted a case-control study at the China Medical University Hospital (CMUH) from 2001 to 2002. All outpatients aged 18 years and older who had visited the gastroenterological clinic and underwent endoscopic examination at the CMUH were potential study subjects. Patients in whom gastric and duodenal ulcers were diagnosed for the first time were recruited. Controls were composed of people with no PUD who had been randomly selected from the same clinic. We used a questionnaire to interview patients and controls in person. At the initiation of each interview, the interviewer explained the purpose of the study and asked if the interviewee was 18 years of age or older; participants were then asked for information on age, height, weight, blood type, lifestyle such as smoking status and alcohol drinking, specific dietary habits such as spice and vinegar consumption, and family history of the disease.. p 0.002. 0.002. 0.002. 0.68. 0.87. All variables were categorized for data analyses. We first compared the demographic difference in age, education, and BMI (body mass index) between patients and controls. Dietary patterns, including regular meals and the intake of spice and vinegar were compared. Our study also investigated the association between lifestyles such as alcohol drinking, smoking, coffee consumption and areca quid chewing, and family history of PUD. The Fisher's exact test was used when cell sizes contained less than 5 subjects in the chi-square test. Test statistics were considered statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05. All analyses were completed using the statistical package SAS version 8.1 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA). RESULTS. The study participants comprised 102 patients and 71 controls; there was a male predominance in the patient group (65.7% vs 42.3%, p = 0.002) (Table 1). Patients were also older (p = 0.002) and had received less education (p = 0.002) than those in the control group. Table 2 shows the comparison of dietary factors between patients and controls. There was no.

(3) Hwang-Huel Wang, et al.. 3. Table 2. Comparison of dietary factors between patients and controls Patients Controls Factors n (%) n (%) Spicy food consumption* 64 (62.7) 45 (63.4) Yes 36 (35.3) 26 (36.6) No Vinegar consumption 33 (32.4) 34 (47.9) Yes 69 (67.6) 37 (52.1) No Daily meal 7 (6.9) 4 (5.6) 2 meals 77 (75.5) 60 (84.5) 4 meals 18 (17.7) 7 (9.9) ≥ 4 meals Regular breakfast 41 (40.2) 21 (29.6) Yes 61 (59.8) 50 (70.4) No Regular lunch 75 (73.5) 60 (84.5) Yes 27 (26.5) 11 (15.5) No Regular dinner 54 (52.9) 44 (62.0) Yes 48 (47.1) 27 (38.0) No After meal 19 (18.6) 13 (18.3) Working 80 (78.4) 51 (71.8) Resting 3 (3.0) 7 (9.9) Walking Change in diet for GI discomfort 44 (43.1) 20 (28.2) No 58 (56.9) 51 (71.8) Yes 102 (100.0) 71 (100.0) Total *2 missing. GI = gastrointestinal.. significant difference between patients and controls in the consumption of coffee, spicy food, daily meals, regular lunch, and regular dinner; however, controls were more likely to use vinegar (47.9% vs 32.4%, p = 0.04). Patients were less likely to change their dietary habits compared with controls (56.9% vs 71.8%, p = 0.005). The proportion of areca quid chewers (14.7% vs 2.8%, p = 0.01) and tobacco smokers (44.1% vs 23.9%, p = 0.016) was higher in the patient group than in the control group (Table 3). Patients also had a much higher rate of selfperceived stress (75.5% vs 45.0%, p < 0.0001). Compared with controls, patients had a higher rate of parental history of the disease (31.4% vs 18.3%, p = 0.01); on the other hand, the PUD prevalence rate in spouses of controls was higher than in spouses of patients (21.1% vs 8.8%, p = 0.0001). Multivariate logistic regression revealed that males had a higher risk (odds ratio, OR =. Total N (%). p 0.93. 109 (63.0) 62 (35.8) 0.04 67 (38.7) 106 (61.3) 0.32 11 (6.4) 137 (79.2) 25 (14.4) 0.15 62 (35.8) 111 (64.2) 0.09 135 (78.0) 38 (22.0) 0.24 98 (56.6) 75 (43.4) 0.16 32 (18.5) 131 (75.7) 10 (5.8) 0.04 64 (37.0) 109 (63.0) 173 (100.0). 2.99) of developing peptic ulcer disease than females (95% confidence interval, CI = 1.13 to 7.90). People who had received 9-years or less education had a higher risk of developing peptic ulcers compared with those who had received more than 13 years of education (OR = 6.76, 95% CI = 2.15 to 21.3). People with self-perceived stress were at higher risk of developing PUD than those who reported no stress (OR = 4.96, 95% CI = 2.03 to 12.1). People with a parental history of PUD were at higher risk than those with no parental history (OR = 2.81, 95% CI = 1.03 to 7.62). People whose spouses had a PUD history (OR = 0.21, 95% CI = 0.06 to 0.75) were at lower risk compared with people whose spouses did not have a history of PUD. DISCUSSION. A study in Shanghai found that men and the elderly were at increased risk of developing peptic ulcer [18]. Patients in the present study.

(4) 4. Factors Associated with Peptic Ulcer Disease. Table 3. Comparison of lifestyle and family disease history between patients and controls Patients Controls Total Factors n (%) n (%) N (%) Areca quid chewing 15 (14.7) 2 (2.8) 17 (9.8) Yes 87 (85.3) 69 (97.2) 156 (90.2) No Alcohol drinking 23 (22.5) 9 (12.7) 32 (18.5) Yes 79 (77.5) 62 (87.3) 141 (81.5) No Smoking 8 (7.8) 5 (7.0) 13 (7.5) 2 meals 37 (36.3) 12 (16.9) 49 (28.3) 4 meals 57 (55.9) 54 (76.1) 111 (64.2) ≥ 4 meals Coffee drinking 39 (38.2) 29 (40.8) 68 (39.3) Yes 63 (61.8) 42 (59.2) 105 (60.7) No Self-perceived stress 77 (75.5) 32 (45.0) 109 (63.0) Yes 25 (24.5) 39 (55.0) 64 (37.0) No Parental PUD history 32 (31.4) 13 (18.3) 45 (26.0) Yes 44 (43.1) 47 (66.2) 91 (52.6) No 26 (25.5) 11 (15.5) 37 (21.4) Unknown Maternal PUD history 13 (12.7) 11 (15.5) 24 (13.9) Yes 60 (58.8) 50 (70.4) 110 (63.6) No 29 (28.5) 10 (14.1) 39 (22.5) Unknown Spouse PUD history 9 (8.8) 15 (21.1) 24 (14.4) Yes 74 (72.5) 32 (45.1) 106 (63.5) No 13 (18.7) 24 (33.8) 37 (22.2) Unknown/unmarried 102 (100.0) 71 (100.0) 173 (100.0) Total PUD = peptic ulcer disease.. were older and had received less education than those in the control group. The National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) in the United States demonstrated a dose-response relationship between education and the risk of peptic ulcer [3]. In the GLOBE study, van Oort et al [19] reported that inequalities in education can explain mortality and unhealthy lifestyle; therefore, they stated that less-educated people may be at a higher risk for developing the disease [13]. Our study found that people educated 9-years or below had a higher risk of peptic ulcer (OR = 6.76, 95% CI = 2.15 to 21.3) compared to those educated more than 13 years and above. Lifestyle and dietary habits are considered important factors in peptic ulcer disease [13]. A Japanese study of men aged 45 years and older revealed that current smokers are at higher risk of both gastric (relative risk (RR) = 3.4, 95% CI =. p 0.01. 0.10. 0.02. 0.73. < 0.0001. 0.01. 0.08. 0.0001. 2.4 to 4.7) and duodenal ulcers (OR = 3.0, 95% CI = 1.9 to 4.7), compared with nonsmokers [12]. Another study found that the cure rate of duodenal ulcer disease was higher in nonsmokers than in smokers (95% vs 53%, p < 0.01) [11]. However, a perspective study failed to confirm their finding this beneficial effect [20]. In this study, we found that patients have a higher incidence of tobacco smoking and areca quid chewing. Our study showed that the odds ratio of PUD was 2.92 (95% CI = 1.38 to 6.18) for people who have smoked; however, it was not significant in the multivariate logistic regression. Kato et al reported a similar finding for risk of gastric ulcer in Japanese smokers compared with nonsmokers (OR = 1.7, CI = 1.2 to 2.5) [12]. Our finding that areca quid chewing is associated with peptic ulcer has not been reported previously. On the other hand, people with lower education may have.

(5) Hwang-Huel Wang, et al.. 5. Table 4. Odds ratios for factors associated with peptic ulcer in the multivariate logistic regression Factors Crude OR (95% CI) Adjusted OR (95% CI) Sex 1.0 1.0 Female 2.62 (1.40-4.88)** 2.99 (1.13-7.90)* Male Age (yr) 1.0 1.0 20 45 0.99 (0.50-1.96) 0.89 (0.33-2.42) 46 60 3.42 (1.07-10.87)* 4.56 (0.89-23.4)* > 60 Education (yr) 1.0 1.0 ≥ 13 1.74 (0.84-3.61) 2.03 (0.75-5.52) 10 12 4.04 (1.82-8.95)** 6.76 (2.15-21.3)*** ≤9 Vinegar consumption 1.0 1.0 No 0.52 (0.28-0.97)* 0.44 (0.19-1.01) Yes After GI discomfort 1.0 1.0 Changing diet 1.93 (1.01-3.70)* 2.03 (0.85-4.82) No Areca quid chewing 1.0 1.0 Never 6.98 (1.56-31.27)* 1.50 (0.21-10.72) Yes Smoking status 1.0 Never 1.52 (0.47-4.92) 0.67 (0.15-3.06) Ex-smoker 2.92 (1.38-6.18)* 1.40 (0.48-4.07) Current smoker Self-perceived stress 1.0 1.0 No 3.75 (1.96-7.19)*** 4.96 (2.03-12.1)*** Yes Parental PUD history 1.0 1.0 No 2.52 (1.12-5.71)** 2.81 (1.03-7.62)* Yes 2.63 (1.22-5.65)** 4.02 (1.40-11.5) Unknown Spouse PUD history 1.0 1.0 No 0.26 (0.10-0.65)* 0.21 (0.06-0.75)* Yes 0.34 (0.17-0.71)** 0.26 (0.09-0.75)* Others *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. GI = gastrointestinal; PUD = peptic ulcer disease.. unhealthy lifestyle was not considered in this study and it showed some limitations. The prevalence of areca quid chewing among patients in the present study was slightly higher than that in the general population in Taiwan. Stress and family history of PUD have been shown to be associated with the risk of PUD [18,21]. Patients in the present study did have higher rates of selfperceived stress and parental PUD than controls. As a result, it is possible that stress (including social stress) may play an important role in initiating ulcer disease [22]. Compared with non-drinkers, men who drink one cup of coffee per day have a significantly elevated risk of developing gastric. cancer [23], although a previous study suggested coffee drinking seems to be of no importance [24]. In this study, we failed to find an association between coffee drinking and the disease. We found that vinegar may be a beneficial factor though it was not significant in the multivariate logistic regression (OR = 0.44, 95% CI = 1.01). Vinegar is regarded as a good dietary source of antioxidant [23] but no study has ever reported an association between vinegar and decreased risk of peptic ulcer disease. Regular intake of breakfast has been observed as one of a number of healthrelated behaviors associated with improving health status [25]; we found that consumption of breakfast on a regular basis has a beneficial effect.

(6) 6. Factors Associated with Peptic Ulcer Disease. on preventing PUD. In a longitudinal study of adults in America [21], persons who perceived themselves as being stressed were found to be 1.8 times more likely to develop peptic ulcers (95% CI = 1.3 to 1.5). We found a higher rate of self-perceived stress among patients than among controls (75.5% vs 45.0%, p < 0.0001) in this study. After adjusting for related factors, people who perceived themselves as being stressed were found to be 4.96 times more likely to develop peptic ulcers (95% CI = 2.03 to 12.1). In Shanghai, family history (parental and/or maternal) of peptic ulcer disease was shown to be associated with increased risk of PUD [18]. However, we found a higher rate of PUD history in spouses of controls than those of patients. To our knowledge, no other report declaring this type of association has been published. Because men are more likely to have the disease than women, we believe that women's husbands are more likely to be PUD patients. The results reported in this study have shown that low socioeconomic status is associated with PUD, and that family history may actually reflect the socioeconomic status. Self-perceived stress is also a risk factor for developing PUD. ACKNOWLEDGMENT. This study was supported by the China Medical University in Taichung, Taiwan (grant number CMC90NTR-01). REFERENCES. 1. Chan FK, Leung WK. Peptic-ulcer disease. [Review] Lancet 2002;360:933-41. 2. Do m i n i t z J A , P ro v en za le D . P re v ale nc e of dyspepsia, heartburn, and peptic ulcer disease in veterans. Am J Gastroenterol 1999;94:2086-93. 3. Sonnenberg A, Everhart JE. The prevalence of selfreported peptic ulcer in the United States. Am J Public Health 1996;86:200-5. 4. Shieh MJ, Wang CI, Wong JM. ABO blood groups in peptic ulcer disease. Biomed Eng 1998;10:49-52. 5. Higham J, Kang JY, Majeed A. Recent trends in. admissions and mortality due to peptic ulcer in England: increasing frequency of haemorrhage among older subjects. Gut 2002;50:460-4. 6. Olbe L, Hamlet A, Dalenback J, et al. A mechanism by which Helicobacter pylori infection of the antrum contributes to the development of duodenal ulcer. Gastroenterology 1996;110:1386-94. 7. Bytzer P, Teglbjaerg PS, Danish Ulcer Study Group. Helicobacter pylori--negative duodenal ulcers: prevalence, clinical characteristics, and prognosisresults from a randomized trial with 2-year follow-up. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:1409-16. 8. Harvey RF, Spence RW, Lane JA, et al. Relationship between the birth cohort pattern of Helicobacter pylori infection and the epidemiology of duodenal ulcer. QJM 2002;95:519-25. 9. Kalaghchi B, Mekasha G, Jack MA, et al. Ideology of Helicobacter pylori prevalence in peptic ulcer disease in an inner-city minority population. J Clin Gastroenterol 2004;38:248-51. 10. Rosenstock S, Jorgensen T, Bonnevie O, et al. Risk factors for peptic ulcer disease: a population based prospective cohort study comparing 2416 Danish adults. Gut 2003;52:186-93. 11. Korman MG, Hansky J, Eaves ER, et al. Influence of cigarette smoking on healing and relapse in duodenal ulcer disease. Gastroenterology 1983;85:871-4. 12. Kato I, Nomura AM, Stemmermann GN, et al. A prospective study of gastric and duodenal ulcer and its relation to smoking, alcohol, and diet. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:521-30. 13. Everhart JE, Byrd-Holt D, Sonnenberg A. Incidence and risk factors for self-reported peptic ulcer disease in the United States. Am J Epidemiol 1998;147:52936. 14. Eastwood GL. The role of smoking in peptic ulcer disease. J Clin Gastroenterol 1998;10(Suppl 1):19-23. 15. Kurata JH, Elashoff JD, Nogawa AN, et al. Sex and smoking difference in duodenal ulcer mortality. Am J Public Health 1986;76:700-2. 16. Andersen IB, Jorgensen T, Bonnevie O, et al. Smoking and alcohol intake as risk factors for bleeding and perforated peptic ulcers: a population-based cohort study. Epidemiology 2000;11:434-9. 17. Cheng KS, Lin CW, Chou FT, et al. Characteristics of Helicobacter pylori infection in peptic ulcer. Chin Med Coll J 1999;8:47-53. 18. Wang JY, Liu SB, Chen SY, et al. Risk factors for.

(7) Hwang-Huel Wang, et al.. peptic ulcer in Shanghai. Int J Epidemiol 1996;25:63843. 19.van Oort FV, van Lenthe FJ, Mackenbach JP. Cooccurrence of lifestyle risk factors and the explanation of education inequalities in mortality: results from the GLOBE study. Prev Med 2004;39: 1126-34. 20. Aldoori WH, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, et al. A prospective study of alcohol, smoking, caffeine, and the risk of duodenal ulcer in men. Epidemiology 1997;8:420-4. 21. Anda RF, Williamson DF, Escobedo LG, et al. Selfperceived stress and the risk of peptic ulcer disease. A longitudinal study of US adults. Arch Intern Med 1992;152:829-33.. 7. 22. Piper DW, Tennant C. Stress and personality in patients with chronic peptic ulcer. [Review] J Clin Gastroenterol 1993;16:211-4. 23.Davalos A, Bartolome B, Gomez-Cordoves C. Antioxidant properties of commercial grape juice and vinegars. Food Chem 2005;93:325-30. 24. Ostensen H, Gudmundsen TE, Ostensen M, et l. Smoking, alcohol, coffee, and familial factors: any associations with peptic ulcer disease? A clinically and radiologically prospective study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1985;20:1277-35. 25.Smith A, Kendrick A, Maben A, et al. Effects of breakfast and caffeine on cognitive, performance, mood, and cardiovascular functioning. Appetite 1994;22:39-55..

(8) 8. 1. 2. 1. 1. 2. 2001. 2002 18. 102. 71. (44.1% v s 23.9%. p = 0.02). (14.7% v s 2.8%. 0.010) (OR = 6.76. 95% CI = 2.15-21.3). (OR = 4.96. 95% CI = 2.03-12.1) 2006;11:1-8. 404. 91. 2005. 7. 28. 2005. 11. 7. 2005. 10. 3. p =.

(9)

數據

相關文件

In addition to asthma, diseases associated with low bone turn over, such as hypothyroidism, can lead to increased stress on tooth roots following applied orthodontic loads and lead

Objectives This study investigated the clinical effectiveness of intervention with an open-mouth exercise device designed to facilitate maximal interincisal opening (MIO) and

In this report, we present a rare case of localized periodon- tal destruction between teeth 25 and 26, which was ultimately diagnosed as an actinomycosis (or

On the contrary, this case teaches that T1 hyperintensity and T2 hypointensity, when associated with other malig- nancy features in buccal space lesion such as low ADC values

A Dharma Service in Han Buddhism is a type of religious ritual constituted of elements such as scripture and mantra recitation, hymns, chanting, playing of Dharma instruments; all

◦ For single-purpose devices such as telephones, automobile fuel and ignition systems, air-. conditioning control systems, printers, and

a substance, such as silicon or germanium, with electrical conductivity intermediate between that of an insulator and a

Then they work in groups of four to design a questionnaire on diets and eating habits based on the information they have collected from the internet and in Part A, and with