Chinese foreign direct investment to Germany - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) 論文題目 Thesis Topic Chinese Foreign Direct Investment to Germany Student: Bernd Burkhardt Advisor: Tang Ching-Ping. 研究生:白安本 指導教授:湯京平. 國立政治大學 亞太研究英語碩士學位學程. 政 治 大. 立. 碩士論文. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 A Thesis. y. Nat. Studies. n. al. C. er. io. sit. Submitted to International Master’s Program in Asia-Pacific. i n U. v. h eChengchi National n g c h i University. In partial fulfillment of the Requirement For the degree of Master in China Studies. 中華民國 2012 年 6 月 July 2012. II.

(3) Abstract China successfully attracted massive inflows of foreign direct investment since the beginning of its open door policy in the late 1970s. Recently however, this trend has been reversed and China itself became a major supplier of FDI for other parts of the world. This development is part of a larger strategy termed The Go Global Policyofficially adopted in the tenth five-year plan and creating a host of OFDI-friendly policies for Chinese enterprises. While China primarily invests into other developing and emerging economies, it also slowly emerges as an investor in developed marketsa development furthered by its massive holdings of foreign reserves. In particular Germany has developed into one of the primary locations attracting Chinese OFDI.. 政 治 大 countries, little is known about its activities in developed markets like Germany. 立 This case study based research paper concludes that Chinese FDI to Germany is. While extensive attention has been devoted to Chinese OFDI flows to developing. ‧ 國. 學. largely limited to urban- and industrial clusters. While M&A in industrial clusters is the fastest growing entrance strategy for the Chinese, the takeover process is. ‧. increasingly welcomed by German companies seeking to be taken over for own strategic reasons. The Chinese capacity to preprocess at low prices, access to the. y. Nat. sit. Chinese market and supply with funds are all key factors in shaping such a consensus-. er. io. based M&A. However, as European governance provides for a variety of social and. al. governmental stakeholders, the investment process is also highly regulated. Given a. n. v i n loophole on European level,C the federal Republic has been able to extend its hengchi U capabilities to direct and impinge upon Chinese FDI across all sectors. As this. potential for regulation is largely not employed in practice, conflict between social and governmental stakeholders becomes increasingly likely, as unions already point to malpractice and violations by Chinese investors. Furthermore, hollow Chinese investments on municipal level may cause a general bias towards OFDI from China, which will make approval of future projects unlikely.. Key Words: Foreign Direct Investment, OFDI, Go Global Policy, China. III.

(4) TABLE OF CONTENTS. List of Figures and Tables ........................................................................................VI Abbreviations ............................................................................................................VII 1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................1 1.1 Motivation ...........................................................................................................1 1.2 Research Objective .............................................................................................3 1.3 Research Design ..................................................................................................4. 政 治 大 1.5 Organization of 立 Chapters ....................................................................................7. 1.4 Literature .............................................................................................................6. ‧ 國. 學. 2. Theories of Foreign Direct Investment ..................................................................8 2.1 Terminology and Distinction ..............................................................................8. ‧. 2.2 Categories of FDI ................................................................................................9. sit. y. Nat. 2.3 Motivations behind Foreign Direct Investment ..................................................9. er. io. 3. Theoretical Approaches toward FDI ...................................................................12. al. n. v i n C h Path Hypothesis 3.2 The Investment Development e n g c h i U ................................................14 3.1 The Eclectic Paradigm ......................................................................................12 3.3 Critique of Dunning’s Approach ......................................................................15 3.4 Latecomers and Born Globals ..........................................................................16 4. Foreign Direct Investment from Emerging Economies .....................................18 4.1 Development of FDI from Emerging- and Developing Countries ...................18 4.2 New Parameters for FDI from Emerging Countries .........................................20 4.3 Geographic Distribution of Emerging Country Investment ..............................23 5. China’s (Economic) Rise .......................................................................................26 5.1 China’s Economic Development ......................................................................26 5.2 China’s Evolving Role in a Global Economy ...................................................29 5.3 Motivation behind Chinese Investments ...........................................................31 IV.

(5) 5.4 China’s OFDI Policy .........................................................................................33 5.5 The Chinese Sovereign Wealth Fund CIC ........................................................38 5.6 Geographic Distribution of Chinese FDI ..........................................................40 5.7 Chinese FDI to developed economies: Europe .................................................43 6. Chinese Investment to Germany ..........................................................................50 6.1 Between Facts and Fallacies .............................................................................50 6.2 What do they do, where do they do it and how? ...............................................55 6.2.1 Sector Focus ............................................................................................55 6.2.2 Regional Focus .......................................................................................57 6.2.3 Post-acquisition management and employment structure ......................62. 治 政 大 6.4 Case Studies of Chinese M&A in Germany .....................................................66 立I: Kelch&Links ....................................................................67 6.4.1 Case Study. 6.3 Frameworks for M&A Transactions in Germany .............................................64. ‧ 國. 學. 6.4.2 Case Study II: Schiess .............................................................................69 6.4.3 Case Study III: Putzmeister ....................................................................71. ‧. 7. Governmental Stakeholders .................................................................................73. Nat. sit. y. 7.1 Institutions matter .............................................................................................73. er. io. 7.2 Government Intervention in FDI ......................................................................76 7.2.1 European Capacity in Foreign Investment ..............................................76. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. 7.2.2 Federal Capacity in Chinese Foreign Direct Investment ........................79. engchi. 7.2.3 State Capacity in Foreign Direct Investment ..........................................83 7.2.4 Social Stakeholder Capacity in Chinese Foreign Direct Investment ......89 8. Conclusion ..............................................................................................................91 8.1 Outlook .............................................................................................................96 9. Literature ................................................................................................................99 Appendix ...................................................................................................................114. V.

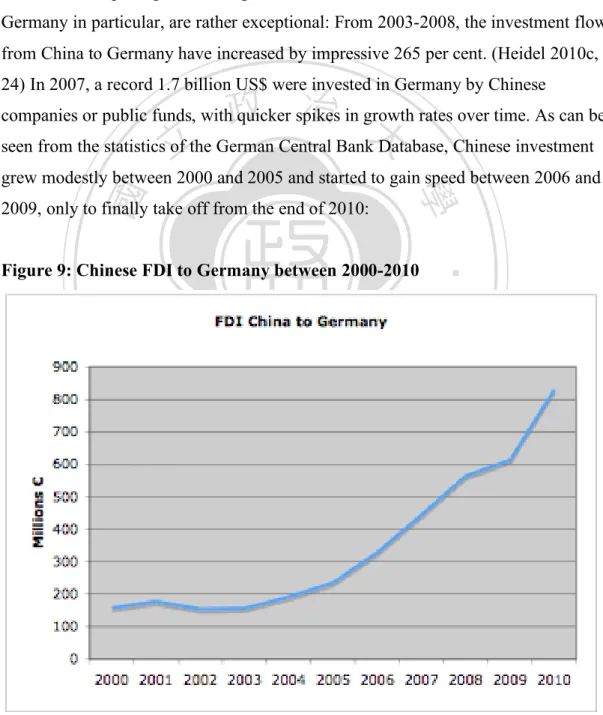

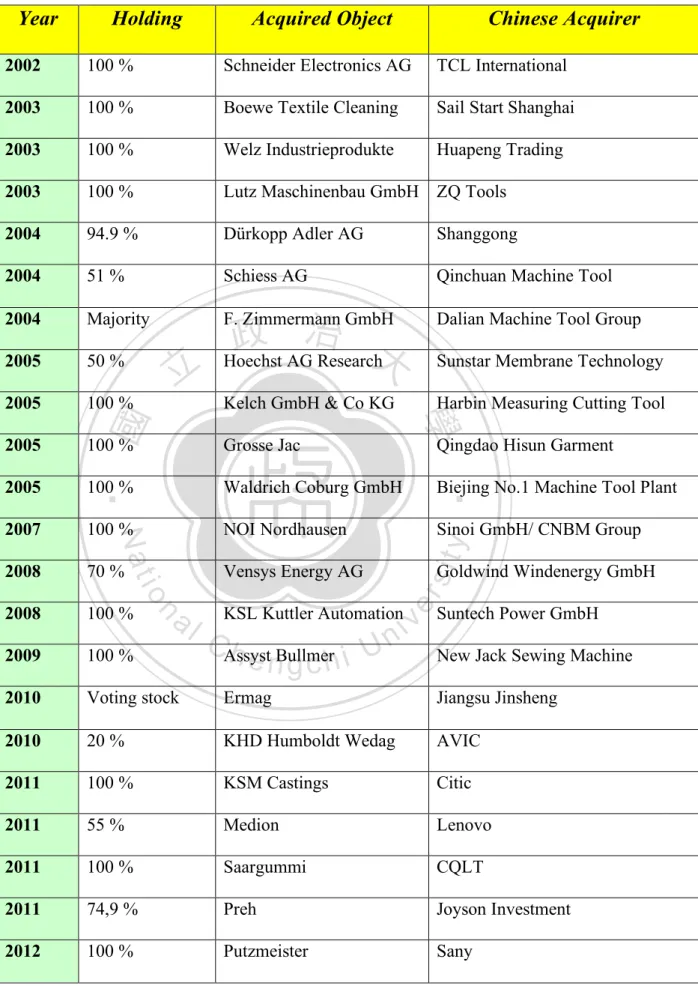

(6) List of Figures and Tables. Figure 1: The Eclectic Paradigm (Eschlbeck 2006/ Dunning 1981), P.13 Figure 2: The Pattern of the Investment Development Path in 5 Stages (Dunning/ Narula 1996), P.15 Figure 3: FDI Outflows from developing and transition economies 1980-2005 UNCTAD 2006), P.18 Figure 4: Estimated Holdings of US: Financial Assets by BRIC Countries (Swartz 2010), P. 21 Figure 5: OFDI Outflows BRIC economies 2004-2010 (UNCATDstat 2012), P.24. 政 治 大 Figure 7: China’s Outward 立 Direct Investment and Cross-Border Acquisitions, 1982Figure 6: BRIC FDI Outflows are taking off (UNCTADstat 2012), P.25. ‧ 國. 學. 2006 (Nicolas/ Thomsen 2008), P. 35. Figure 8: Chinese Investment in the European Union (Heidel 2010b), P.45 Figure 9: Chinese FDI to Germany between 2000-2010 (German Central Bank), P.50. ‧. Figure 10: List of Chinese Acquisitions in Germany between 2002-2012, P.53. y. Nat. Figure 11: Chinese Investment Projects in Germany 2003-2008 (Handtke 2009), P.55. sit. Figure 12: Chinese companies in Germany by federal state, P.60. al. er. io. Figure 13: Population Clusters with highest number of Chinese companies in. n. v i n Ch Figure 14: Share of German Employees companies in Hesse e n gincChinese-invested hi U Germany (Ppulations Labs 2011), P.61 2009 (Wang 2008), P. 64. Figure 15: Hierarchical Structure of German governance and its relation to the European Union (Gerlach 2010), P.76 Figure 16: The federal governance of Germany (Gerlach 2010), P.82 Figure 17: Investment Flows to German Federal States (German Central Bank 2009), P. 87 Figure 18: Structure of Investment Promotion North-Rhine Westphalia (NRW Invest 2012), P.88 Figure 19: Structure of Investment Promotion Hesse (Hessen Agentur 2012; FRM 2012), P.89 Figure 20: Structure of Investment Promotion Hamburg (HWF 2012), P. 90. VI.

(7) Abbreviations. BIT- Bilateral Investment Treaty BMWI- German Federal Ministry of Economics and Technology BRIC- Brazil, Russia, India, China CEO- Chief Executive Office CIC- China Investment Corporation DAX- German Stock Index DB- Deutsche Bank. 政 治 大. EME- Emerging Market Economy. 立. EP- European Parliament. FDI- Foreign Direct Investment. ‧ 國. 學. GIGA- German Institute of Global and Area Studies. GTAI- Germany Trade and Invest (National German Investment Promotion Agency). ‧. IMF- International Monetary Fund. y. Nat. MNC- Multinational Corporation. n. al. er. io. NDRC- National Development and Reform Commission. sit. MOFTEC- Ministry of Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation. v. OECD- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Ch. OFDI- Outward Foreign Direct Investment. engchi. i n U. PRC- People’s Republic of China. SAFE- State Administration of Foreign Exchange SETC- State Economic and Trade Commission SEZ- Special Economic Zones SME- Small and medium enterprises SOE- State-Owned Enterprise SWF- Sovereign Wealth Fund TNC- Transnational Corporation UNCTAD- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development WTO- World Trade Organization. VII.

(8) 1. Introduction 1.1 Motivation “China is taking over the European Union- and we Europeans sell our soul.” 1 - German EU Commissioner Günther Oettinger. The emergence of Foreign Direct Investment is a central result of ongoing economic. 政 治 大. globalization. Investment flows between countries establish new contexts of economic exchange and integration. Formerly, triad countries like Japan, Germany or the United. 立. States exclusively dominated Foreign Direct Investment, making the Western World. ‧ 國. 學. the central source of FDI. (Dunning/ Kim/ Park 2008, 1) During the early 1980s, new players from East- and Southeast Asia started to emerge. These co-called tiger states;. ‧. usually referring to Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan; started to intensify their investment relations with the outside world rapidly. (Mathews 2006, 5) Only recently. sit. y. Nat. have new players entered the stage and gained hold in this type of capital movement, stirring much concern. The emerging BRIC economies (Brazil, Russia, India and. io. n. al. er. China) all have their staggering size and rapid speed of development in common-. i n U. v. leading to the assumption they will eventually move beyond their mere potential.. Ch. engchi. (Deng 2008, 17) One of the most discussed examples is China, which started to appear as an investor in developing countries early on, but recently also extended its activity into the developed markets. (Schüller/ Turner 2005, 11) China has been successfully attracting Foreign Direct Investment since the beginning of its open door policy in the late 1970s. For the first time, in 1993, China became the largest single recipient of Foreign Direct Investment among all developing economies, continually improving its rank among all other nations since 2006.2. 1. Original: China übernimmt die EU, und wir Europäer verkaufen unsere Seele. Quoted from: SZ 09.13.2011 2 UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2004 (Annex table B.1, pp. 367 /370); UNCTAD Investment Brief Number 1, in 2007 China was ranked No. 2 (after the U.S.) in 2004. 1.

(9) As mentioned above, China however is not only experiencing an inflow of FDI, but has itself become a major source of FDI for other parts of the world. This development is part of a larger strategy dubbed The Go Global Policy (走出去, Zǒuchūqù), which was officially adopted in the tenth five-year plan of October 2001. (Cheng/Ma 2008, 8) In the following years, Chinese companies have set up shop abroad and entered foreign markets as investors. Accordingly, Chinese outward investment rose from around 2.7 $ billion in 2002 to 56.5 $ billion in 2009, while direct investment rose from 29.9 $ billion to 245.7 $ billion for the same time-span.3 Extensive research exists with regards to FDI flowing from China to countries of the Global South (such as in Asia, Africa and Latin America), yet little research has been. 政 治 大. undertaken on the role of China as a source of outward FDI (OFDI) to developed markets in particular.. 立. With the establishment of the China Investment Corporation, a Sovereign Wealth. ‧ 國. 學. Fund with resources of more than US $200 billion, Chinese OFDI has received growing scrutiny in the US and Europe. (Berger/ Berkofsky 2008, 2) And indeed,. ‧. Germany has in the past years developed to become one of the primary locations. y. Nat. attracting Chinese OFDI. (Cheng et al 2008, 13) Media have picked up on the story. sit. and reacted with a mixture of fear and enthusiasm to the new development. The notion. al. er. io. that China will eventually buy up German companies’ technological advantages, and. v. n. particularly target them for their know-how, creates negative sentiments in the wider. Ch. public. (Milleli/ Hay 2008, 12). engchi. i n U. Since then, media and politicians warned of a Chinese buying spree in Germany. Where China’s economic potential and staggering growth rates are concerned, outward direct investment from China may soon become an important factor for further economic development in Germany. (Chow 2010, 60) While there is a multitude of research on the Going Global Strategy and OFDI to Germany, there is no actual in- depth analysis of the integration between the Chinese and the German economies. Some cases underline the potential dangers of inviting Chinese FDI in, while others highlight the positive impact this has had on German companies in. 3. Refer to: 2009 Statistical Bulletin of China‘s Outward Foreign Direct Investment. Ministry of Commerce, http://hzs.mofcom.gov.cn/accessory/201009/1284339524515.pdf. 2.

(10) financial distress. (Chuang 2010, 18) Largely left in the dark however, remains the capacity of Germany’s governmental and social actors to regulate and shape Chinese OFDI. This study aims to bridge the gap between a wider discussion of Chinese OFDI flows and the largely ignored roles of managing institutions in government and society alike.. 1.2 Research Objective While Chinese Outward Foreign Direct Investment is by no means a new phenomenon, little research has been undertaken with regards to the managing. 治 政 China to Germany have shifted quite considerably;大 now ranging between suspicion 立more important that such a study be undertaken at this point and fear; it seems all the. capacity of governmental and social actors in Germany. As perceptions of OFDI from. ‧ 國. 學. in time. OFDI from China is not simply a free-flowing phenomenon, happening largely on its own terms in the respective recipient countries, but is subject to- and. ‧. regulated by local legal frameworks and vested interests of different stakeholders. Therefore the study of these stakeholders and their respective roles -embedded into a. sit. y. Nat. wider discussion of Chinese OFDI- will contribute to a more thorough understanding. io. n. al. er. of these developments.. i n U. v. The possibilities of- and roles played by governmental and social stakeholders alike. Ch. engchi. are an exciting and highly relevant question. This thesis takes a wider perspective, thus not only narrowing itself to the analysis of the individual actors, but also embedding it into a wider discussion of China’s OFDI rationale, trends, perspectives, resistances and overall developments to Germany. For this purpose, the development of OFDI flows from China to Germany needs to be analyzed before the background of standard theory of direct investment determinants, the general investment behavior of companies, and FDI flows from developing and emerging economies. Since China’s economy is highly susceptible to state influence, the particularities of Chinese OFDI need to be discussed and taken into consideration here.. 3.

(11) The analysis of Chinese OFDI to Germany needs to comprise of statistical aspects beyond the theoretical discussion. How large has Chinese FDI become, how has it developed and what are the characteristics of its sector- and geographical distribution? Furthermore the motivation of Chinese companies needs to be taken into consideration- is there any sector focus that requires specific attention? Only with a thorough understanding of the background of Chinese OFDI, its size and motivations, can a fruitful discussion of its local management be undertaken. Without this background, conclusions on the management capabilities of German stakeholders fall short of acknowledging the complex and comprehensive parameters determining Chinese FDI flows.. 立. 政 治 大. 1.3 Research Design. ‧ 國. 學. As stated above, this study will attempt an examination on a currently insufficiently. ‧. explored subject. The actual setting of the issue to be discussed is one of wider. y. Nat. political and economic relevance, since developments in economic relations between. sit. states are concerned. While for many years investment exclusively flowed from the. er. io. Northern hemisphere to the Global South, and then later on from South to South, we. al. v i n C h as to providing therefore aims to make a contribution e n g c h i U further in depth analysis in this n. still know little about the specifics of South to North investment flows. This research sense. Germany and China are both economic heavyweights with increasing. cooperation that now flows both ways. There is little research available on where this relationship may be leading before the background of increasing OFDI. The access of Chinese companies and Chinese state funds will likely impact increasingly on Germany, yet we know little about the capability of the German government and society (let alone the EU) to respond to- and influence these OFDI flows. In the light of the diverse body of literature available with regards to the topic, in the first half this study employs a deductive approach- starting from basic theoretical models of Foreign Direct Investment and then closing in on the topic of Chinese OFDI in several steps.. 4.

(12) First, primary data is employed to provide a general overview of developments and the nature of OFDI flows from China to Germany. This is done through theoretical literature, existing research and statistical data from multiple sources. Since variations exist with regard to congruence of data, statistics are employed to provide insights into general trends. After this, secondary data such as existing research papers, journals, books, and media sources are utilized to enhance further the outcomes of this analysis. They further contribute towards the analysis of Chinese OFDI in terms of quality as well as its spatial- and sector distribution. The second half of the paper is primarily based on case study research, secondary data an additional expert interview. The interview has been conducted in a wider fieldwork. 治 政 releases were supplied through the federal Ministry大 of Economics. 立. with a high-ranking official from a state ministry of Economics. Furthermore, press. ‧ 國. 學. Secondly, the role of social agents in Chinese OFDI is assessed through secondary data. Since their means of influence are clearly stated by law, case studies suffice to. ‧. highlight their role. For social actors in particular, media analysis was used as a helpful tool in exploring their capabilities and strategies vis-à-vis Chinese investment.. sit. y. Nat. er. io. To sum up, the research will discuss the topic along four basic research questions: •. How has Chinese OFDI to Germany developed?. •. What can be said with regards to nature, quality and size of Chinese OFDI to. n. Germany? •. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. What is the spatial- and sector distribution of Chinese direct investments in Germany?. And as my central research question: •. What influence is the German government (or the regional states/ or EU) able to exert on Chinese investment today and in the future? What is the influence of social agents (esp. workers unions) on Chinese investment in Germany?. 5.

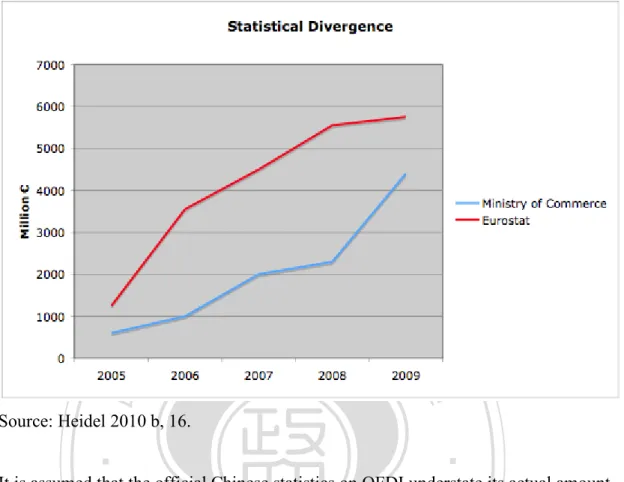

(13) 1.4 Literature The first chapters of this analysis will be based on existing research that is available in abundance, albeit its individual limitations. The study of direct investment is a comparatively young discipline, emerging around the 1960s and 1970s. Several theoretical models have developed as groundwork for this discussion, most notably John H. Dunning’s elaborations on FDI. As his theoretical assumptions have undergone considerable critique (as FDI and its stakeholders have evolved over time), diverging theoretical models will be taken into consideration as well. Yet his Eclectic Paradigm and Investment Development Path Hypothesis have remained the foundation of any discussion on Foreign Direct Investment.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. A host of literature exists on the specifics of FDI from emerging economies and China in particular. These range from theoretical discussion to case based studies. The very basic assumptions however, are mostly derived from the United Nations Conference. ‧. on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) which not only provides a numerical analysis. y. Nat. but furthermore a qualitative review of emerging economies’ FDI activity. Further. sit. statistical discussion is based on not only UNCTAD’s statistical program. n. al. er. io. UNCTADstat but also on the statistical data provided through the German Central. i n U. v. Bank, Chinese official statistics, and the European Statistical Agency Eurostat.. Ch. engchi. Third, literature on China’s specific and particular economic development and FDI formation is available in abundance. This entails literature from an economics- as well as a developmental perspective. In particular the discussion of China’s Outward Foreign Direct Investment and China’s Go Global Policy by Li Zhaoxi (in Larcon 2009) are employed to explain the specific configuration of Chinese FDI activity. Li Zhaoxi’s discussion, published in cooperation with the École des Hautes Études Commerciales de Paris and Tsinghua School of Economics and Management, is the most current publication on the Chinese OFDI regime. Academic literature on Chinese OFDI flows to Germany has remained more or less sparse until to date. While various publications exist, their respective depth, extent and. 6.

(14) reach is limited, leading to fragmented analysis. Nonetheless, several papers by nongovernmental institutions such as the German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), the EU-China Civil Society Forum, the German Center for Market Entry and Bertelsmann Stiftung all elude on the topic. Correspondingly, the later half of the paper on respective management roles of German stakeholders in government and society is based on individual research and fieldwork.. 1.5 Organization of Chapters. 治 政 and practical) is explained and motives of OFDI are 大discussed. This is followed by a discussion of the most立 important theoretical models and explanations. The general Step one is a theoretical introduction to OFDI as such. The basic concept (theoretical. ‧ 國. 學. theoretical excursion is followed by an in-depth discussion of OFDI flows from BRIC countries and provides further clarifications on the context of Chinese OFDI. This. ‧. chapter provides a basic introduction to the state of the Chinese economy, its Going Global Policy and China’s Sovereign Wealth Fund.. sit. y. Nat. io. er. The second half comprises the main body of the research. It brings together the findings of existing literature on Chinese OFDI and includes for a thorough analysis. n. al. i n U. v. of Chinese OFDI to Germany. Thereafter the study concludes with an assessment of. Ch. engchi. development, nature, quality and size of Chinese OFDI to Germany. In its course, questions of spatial- and sector distribution of Chinese OFDI in Germany are addressed. The chapter does further aim to provide several short case studies of Chinese companies, which offer exemplary insights into the results reaped from the macro-perspective analysis. The last step rounds up the analysis by shedding light on the ability of governmental and social stakeholders to shape and influence the inflows of OFDI from China. This section explains their roles in past and present, as well likely future developments. Furthermore, it assesses the conflict potential between the different spheres of institutions engaged and the trends that can be derived from the analysis.. 7.

(15) 2. Theories of Foreign Direct Investment 2.1 Terminology and Distinction The common understanding of the term Foreign Direct Investment is that of a capital investment (i.e. acquisition of a substantial share of a company) with the aim of exerting influence on the management. (Duce 2003, 2) Often several aims prevail, yet control is central to the definition of direct investment. (Haas, Neumair & Schlesinger 2009, 80) FDI can either take the form of equity capital investment, reinvestment of profits, investment of real assets as well as financial- and business loans. The direct investment is only termed “foreign”, if giver and receiver do not reside in the same. 政 治 大 capital is transferred from 立one actor to another. This capital can take many forms,. country and a monetary flow across borders is created. In Foreign Direct Investment,. ‧ 國. 學. including not only money, but also goods, trademarks, knowledge or technology.. The term FDI needs to be distinguished from that of Portfolio Investment. Portfolio Investment only aims to reap profit and diversify risks, yet has no interest in creating. ‧. actual managerial control on the side of the investor. Portfolio Investments are. y. Nat. furthermore capital based, i.e. they do not entail the transfer of intangible assets.. er. io. sit. (Neumair 2006, 41-60). al. n. v i n C h it is difficult toUestablish any clear notion of the at first sight. In managerial practice, engchi. Admittedly, the ambiguity of the term Foreign Direct Investment may not be realized term “influence / control” that is central to FDI. Following a definition by the International Monetary Fund, a direct investment requires at least 10 per cent shareholding from abroad to be termed Foreign Direct Investment. Other sources suggest a number of around 25 per cent with regards to a credible influence to be exerted. The German Central Bank has long followed this approach, but has returned to the 10 per cent threshold in 1999. (IMF 2004) This paper will therefore proceed in accordance to the established term of understanding of 10 per cent.. 8.

(16) 2.2 Categories of FDI Foreign Direct Investment takes several distinct forms. First a line needs to be drawn between fully controlled enterprises and those where only partial ownership is held. Fully controlled enterprises are usually termed Greenfield Investments, since they are either the product of a company foundation (be it a subsidiary or representative office) or result from the acquisition of an already existing company. If a plant previously employed for another industrial purpose is remodeled in the investment process, this is termed Brownfield Investment. It entails a significant change in the means of production and personnel. (Lukas 2004, 83) The second form of FDI is the partial holding (below 100 per cent) by a foreign. 政 治 大 between two or more companies, usually termed Joint-Venture or a partial acquisition 立 as well as partial consolidation. Today, acquisition and consolidation are most often investor. This can either be the case in the foundation of a cooperative venture. ‧ 國. 學. termed Mergers & Acquisitions.. ‧. Furthermore, OFDI can be separated into horizontal and vertical investments.. y. Nat. Horizontal investment refers to investments within the same or similar part of the. sit. value chain of a parent company. Vertical investments refer to either a position in the. er. io. value chain that lies before or after the position of the parent company. This means. al. v i n C h activity of theUparent company. before and after the actual production engchi n. that vertical investment would either engage in raw materials or in sales, both located. 2.3 Motivations behind Foreign Direct Investment Foreign Direct Investment can furthermore be categorized according to its motivation. Overall, several motivations at the same time may apply for a single case. The first category of objectives is market-seeking. In this case, FDI has the aim of developing or maintaining economic activity with a foreign market. This investment can on the one hand be done with the aim of furthering export activity (exportoriented market seeking) or on the other with the domestic market in mind (internal. 9.

(17) market seeking) if the investment primarily furthers activity in this internal market. Suppliers often internationalize with this objective in mind. If their customers outsource abroad they are forced to undertake market-seeking investment in order to ensure their competitive positioning in the outsourcing market of their customers and on the domestic market alike. For suppliers in such constellations, this investment may further be encouraged through custom duties, import quotas and additional taxes if they keep production domestic yet need to supply at competitive prices to their customers abroad. Secondly FDI may be efficiency-seeking. This type of investment aims to improve cost- and profit structures through the remodeling of the value chain. The effective. 政 治 大 profitable. This type of investment is largely known under the term “Outsourcing”立 i.e. the relocation of production facilities into countries with lower labor cost. This has balance between different markets and locations helps a company to remain. ‧ 國. 學. particularly been the case for companies from developed countries that move their labor-intensive manufacturing or services abroad in order to cut costs.. ‧. y. Nat. Third, FDI may be resource-seeking. The motivation behind such investment aims to. sit. ensure the supply with resources needed for production purposes. These may include. er. io. natural resources like oil and gas or pre-processed parts for further production. This. al. type of direct investment has gained increasing prominence with regards to mineral. n. v i n C hMost countries notUonly control the export quota for products, so called “rare earths”. i e n g cbuthalso their domestic production of this resource, place large investments in extracting companies in Australia, to name just one example. Fourth, FDI may be asset-seeking. This type of investment aims to secure man-made assets, such as knowledge or technology. As these are man-made products, they come in forms like patents or brands that contain their own market value, but can also come in the form of management know-how or technological expertise. Fifth, FDI may be encouraged by various other aspects. Countries acknowledge the importance of foreign direct investment in developing their economy. Most countries therefore vie for investors through monetary or regulatory incentives. Monetary. 10.

(18) incentives can either come in the form of subsidies or tax reductions and regulatory incentives mostly in the form of particularly soft legal regulatory frameworks (for example in environmental standards or company foundation procedures) for foreign investors. Many countries are furthermore actively promoting themselves through national investment agencies and even cities try to attract investors through regional marketing. Not only the host country plays a prominent role in shaping an investment decision, but also the OFDI framework of the sending country. The investment may be politically encouraged through governmental agencies, consultancy, financial aid and preferable access to capital or simply be ordered as in the case of many State-Owned Enterprises (SOE).. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 11. i n U. v.

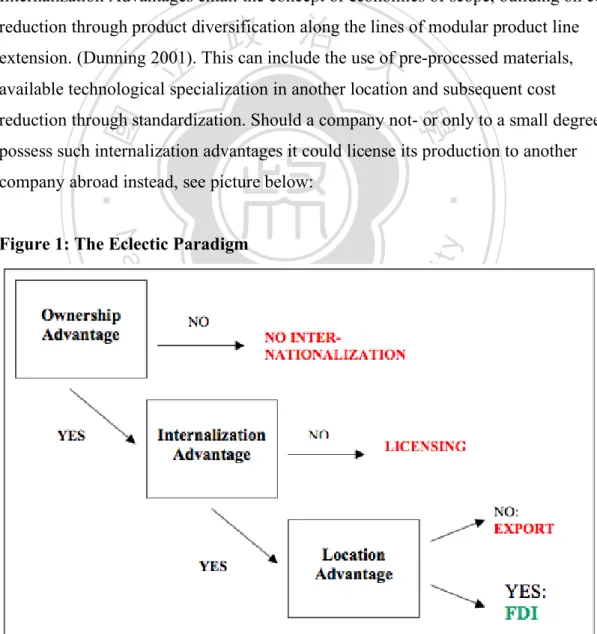

(19) 3. Theoretical Approaches toward FDI 3.1 The Eclectic Paradigm The standard literature explains FDI flows as being based on market imperfections. This means that companies entering a foreign market need to possess advantages over the local competition. (Vernon 1966, Kindleberger 1969, Johanson/ Vahlne 1977) The most prominent theoretical framework applicable to this strand of theory is Dunning’s Eclectic Paradigm (as has been developed and laid out in his publications in the years 1974, 1978, 1981, and 2005). According to his theory, firms only employ FDI if three specific advantages are available: The Ownership-Advantage, the. 政 治 大. Location-specific Advantage and the Internalization- Advantage.. 立. ‧ 國. 學. The Ownership Advantage is based on the understanding that companies need to possess firm-specific advantages over their competitors. Often, this advantage builds on the assumption of economies of scale: a company is able to realize larger profit. ‧. from their product than a local competitor could. A company may also hold exclusive. y. Nat. rights of patents, brands, or management skills that are intangible assets. The company. sit. could also have better access to resources or suppliers than its competitors. If the firm. er. io. is choosing to set up a foreign subsidiary, this company may further have competitive. al. n. v i n C h downsizing the U home country- thereby effectively e n g c h i cost of operations. The ownership access to controlling, marketing and accounting through its holding company in the. advantage can also be constituted by aspects as simple as size of a company, as large companies have much easier access to resources that allow for market dominance. Taken together, these advantages must outbalance the market constraints such as costs for communication or cost of fending off discrimination in the host market. The Location Advantage refers to factors that make it more desirable for a company to set up shop in a foreign market, rather than just supplying it through exports. It is based on the spatial distribution of sourcing markets, price variations on these markets (i.e. through taxes and duties), quality standards, productivity (of labor, energy, resources, etc.) as well as costs deriving from transport and communication. A company may for example translate favorable transportation costs between two. 12.

(20) locations into a Location Advantage- effectively making prices competitive with regards to local competitors. Advantages can however also be persisting within a fixed location, meaning stable political conditions, trade barriers that keep out competitors or tax incentives. Thus location advantages refer to the overall framework of FDI in its relation to geographic position. The Internalization Advantage exists when internal production operations across borders are cheaper than sourcing in the free market. Moving into another market through the means of direct investment can effectively help safeguard quality standards or copyrights that may well be infringed in a licensing process. Secondly, Internalization Advantages entail the concept of economies of scope, building on cost. 治 政 extension. (Dunning 2001). This can include the use大 of pre-processed materials, available technological立 specialization in another location and subsequent cost. reduction through product diversification along the lines of modular product line. ‧ 國. 學. reduction through standardization. Should a company not- or only to a small degree possess such internalization advantages it could license its production to another. ‧. company abroad instead, see picture below:. Nat. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Figure 1: The Eclectic Paradigm. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Source: Eschlbeck 2006, 223; in accordance with Dunning 1981, 32.. 13.

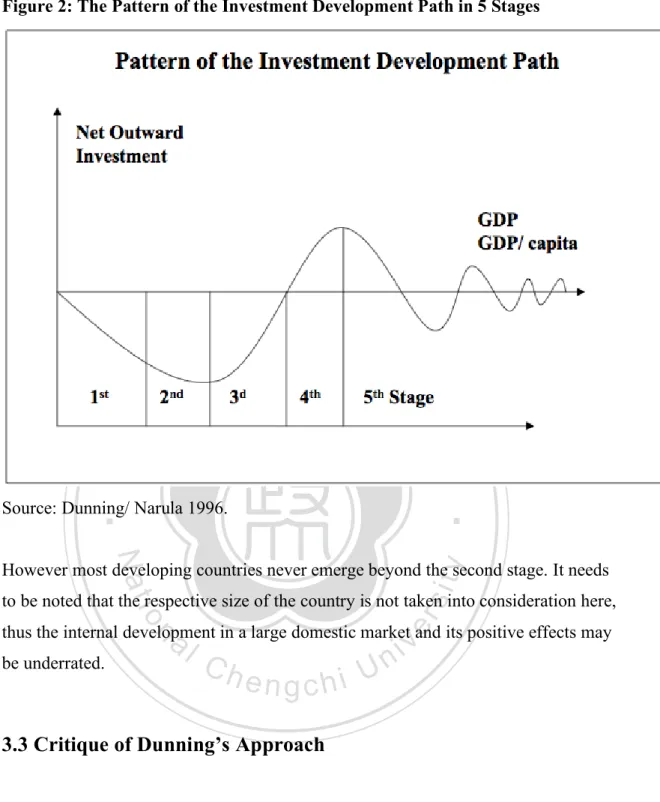

(21) 3.2 The Investment Development Path Hypothesis Dunning further proposed that the stage of development is correlated with OFDI- the richer a country, the higher its levels of OFDI: the Investment Development Path Hypothesis. Dunning hereby provides the basic analytic framework for Foreign Direct Investment analysis. (Dunning et al 2008) His observation is that developing countries undergo certain stages in their outward investment, which are linked to their own stage of development. According to the respective developmental stage of the country, the OLI advantages all show differing variations. Dunning distinguishes four phases. In the first phase, the development level of the. 政 治 大. economy is low. The local companies have little or no comparative advantages and. 立. thus do not enter international markets as investors. Neither can the country provide. ‧ 國. 學. for any incentive to draw in investment from abroad. Outward and inward investment flows remain small.. In the second phase, the gross domestic product is rising slowly. Foreign companies. ‧. are increasingly taking an interest and undertake asset-exploiting investments (i.e.. y. Nat. they tap into the local consumer market or cheap labor market). The comparative. al. er. io. Therefore outward FDI are still not growing.. sit. advantage however remains small and they are only engaging in export activities.. n. v i n C h Thereby the local capabilities of national companies. e n g c h i U companies develop their own The third phase sees the start of learning processes, which improve the overall. advantages and are ready to enter the international markets as investors. However the inward investment by foreign investors remains comparatively dominant. Only in stage four can the national companies reap such substantive OLI advantages from their development that the outward investment increases over the inward investment. This experience is largely mirrored by entities like Singapore or Hong Kong. (See Figure 2 below). 14.

(22) Figure 2: The Pattern of the Investment Development Path in 5 Stages. 政 治 大. 立. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. Source: Dunning/ Narula 1996.. y. Nat. sit. However most developing countries never emerge beyond the second stage. It needs. al. er. io. to be noted that the respective size of the country is not taken into consideration here,. n. thus the internal development in a large domestic market and its positive effects may be underrated.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 3.3 Critique of Dunning’s Approach The Eclectic Paradigm and Investment Development Path Hypothesis by Dunning both provide a solid groundwork for the discussion of Foreign Direct Investment. However the approaches established by Dunning have their limitations. Dunning based his assumptions on the experience of private companies from developed economies. As we see a surge in OFDI from countries with a large share of State-Owned Enterprises, it is questionable whether this theory can capture the actual parameters of state roles played in the Foreign Direct Investment of such companies.. 15.

(23) Furthermore, the experience of many emerging economy companies contradicts to large parts the basic assumptions of the Investment Development Path Hypothesis. While Dunning acknowledges their emergence in his publication of 2009, their very early emergence on the global stage basically contradicts his hypothesis. And finally, Dunning’s theorem seems somewhat outdated with regards to the abundance of possibilities for companies to go abroad today. His hypotheses do not include cooperative forms of market entrance strategies currently employed by many companies- including Joint-Ventures or various forms of Franchises.. 政 治 大. 3.4 Latecomers and Born Globals. 立. New theoretical approaches have been created to capture the emergence of OFDI from. ‧ 國. 學. emerging economies. The prime example are the tiger states during the 1980s. Two theories emerged to best capture the phenomenon: The Born Globals and the. ‧. Latecomer Theory.. y. Nat. sit. The concept of Born Globals assumes that there is a subset of companies, usually very. er. io. young, which internationalize quickly based on cooperation with market leaders.. al. These companies may have been founded by managers already in possession of. n. v i n sufficient experience and vital C contacts U business, but this is not a h e n gin cinternational i h general rule. Through their cooperation with firms from developed markets, skills are transferred while organizational structures remain flexible. (Madsen/ Rasmussen/ Servais 1997) The main characteristic of a Born Global is thus its ability to innovate and expand internationally quickly. The Latecomer Theory assumes that companies from emerging economies derive an advantage from their structural flexibility. Their perspective is inherently global since they are not constrained by previous structural buildups. Thus they can easily innovate and incorporate new ideas, thereby internationalizing fast paced. (Buckley/ Cross/ Tan/ Xin/ Voss 2007) Considering the framework they operate in, their very lack of. 16.

(24) structural borders (i.e. established forms and processes) allows them to change quickly and thus become highly efficient and adaptive to their surrounding. These new global companies have certain aspects in common. First, they purchase complementary assets such as brand names or technology in order to expand quickly without much time spent on R&D activities. Second, they reap advantages from lower production costs in their home-countries, which they later employ on the foreign market. Third, they form transnational networks to help them innovate quickly and learn. Fourth, they expand at rapid pace and catch up to established companies while circumventing the traditional steppingstones of development.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. 17. i n U. v.

(25) 4. Foreign Direct Investment from Emerging Economies 4.1 Development of FDI from Emerging- and Developing Countries The overall development of Foreign Direct Investment flows has been staggering in its speed and its expanse since the 1980s. Starting at a level of around US$ 50 billion per year between 1980-85, flows have grown by factor forty until 2007. (Sauvant/ Maschek/McAllister 2009, 1) A large share of these flows is now emerging from former developing countries. Had they between 1995 and 2000 on average accounted for a mere 0.3 per cent of global flows, their share reached 2.4 per cent of flows in 2007 and subsequently increased to 3.1 per cent in 2008. (Sauvant et al 2009, 2). 政 治 大 Therefore it can be said立 that OFDI is no longer exclusively coming from developed. ‧ 國. 學. countries, but has been extended through new stakeholders from developing and. transitioning economies. (UNCTAD 2007, 1) These types of economies increasingly develop Multinational Corporations (MNCs) and thus increase their FDI outflows and. ‧. share in global outflows. (see graph below). y. Nat. sit. Figure 3: FDI Outflows from developing and transition economies 1980-2005. n. al. er. io. In US$ billions and per cent (excl. Bermuda, British Virgin- and Cayman Islands). Ch. engchi. Source: UNCTAD 2006.. 18. i n U. v.

(26) The liberalization of foreign direct investment regimes has had a great impact on the worldwide environment for Foreign Direct Investment. In a similar vein, advancements in logistics and communication technology have allowed for increasing transnational cooperation to emerge: “Driven by information technology and its mutually reinforcing wealth creating interaction with globalization, both the internal and external business environments are being transformed. Business is becoming less hierarchical, faces shorter product life cycles, industrial restructuring based on deconstructed value chains, new competitors from unexpected sources and countries, virtual corporations (…)” (Aggarwal 1999, 83). 治 政 大developed countries, but has This has not only had a positive impact on firms from likewise made it easier 立 for companies from developing- and transitioning markets to ‧ 國. 學. adjust their strategies accordingly and move abroad as investors.. ‧. According to Sauvant et al (2009), OFDI flows from emerging or transitioning markets have developed with particular speed starting from 2003- however remained. Nat. sit. y. mainly driven not by developing economies, but by emerging- or transitioning. er. io. economies, such as the Russian Federation, India or China. (Gammeltoft 2008, 8) As Dilip Das notes, this development goes hand in hand with a wider economic revival of. n. al. Ch. these nations on the global stage:. engchi. i n U. v. „Towards the end of 2007, after the post-sub-prime mortgage crisis in the United States (US) economy, it seemed increasingly evident that the global economy was on the cusp of a defining historic transformation; economic power was in the process of making a secular shift from the industrial economies to China and the major emerging- market economies (EMEs).“ (Das 2008, 3) As will be shown subsequently, it is particularly these emerging economies, that have extended their reach beyond their direct vicinity into the global markets and were among the first to enter the developed countries as investors.. 19.

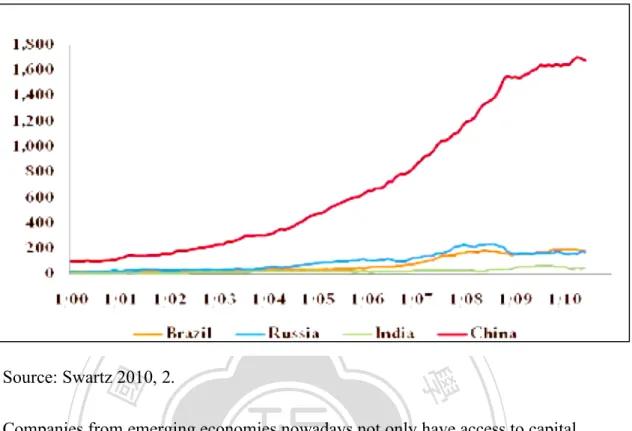

(27) 4.2 New Parameters for FDI from Emerging Countries While formerly restraining the outflow of capital, developing- and transitioning economies have recently started to liberalize and even actively promote OFDI outflows. Several factors have contributed to this development: One prominent factor is the large deposits of foreign reserves some former developing countries have been able to build up over time. These give them the financial means to send their companies abroad to make crucial investments in foreign markets. While many countries have amassed these reserves in similar fashion, they are particularly pronounced in the case of China. (Swartz 2010, 1) Its combined. 政 治 大. reserves in 2010 measured US$ 2.7 trillion and thus are nearly three times the. 立. combined value of those held by Russia, India, and Brazil together:. ‧ 國. 學. „In the near future, in view of the pressure generated by China’s bursting foreign reserves (US$ 1.4 trillion by September 2007) on its money supply. ‧. and its exchange rate, it is now China’s official policy to encourage. io. er. to the official policy speak.“(Cheng et al 2008, 23). sit. y. Nat. foreign reserves to leave the country: “To open the flood gate,” according. al. n. v i n C h economic crisis.UThe crisis itself lending even economies to invest abroad despite engchi The amassed foreign reserves make it possible (or even a necessity) for emerging more momentum to the already large financial means:. „SOEs in countries with high foreign currency reserves, in particular, remain in a position to expand abroad, the regulatory environments of host countries permitting. Their ability to take a long- term horizon helps in this regard, and the fact that asset prices in a number of potential host counties are low or in distress encourages cross-border M&As“ (Sauvant et al 2009, 12) Most often discussed is the large-scale engagement of China with US financial assets. Here again, China is leading the pack. (see graph below). 20.

(28) Figure 4: Estimated Holdings of US Financial Assets by BRIC Countries in US$ billions, 2000-2010. 政 治 大. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Source: Swartz 2010, 2.. Companies from emerging economies nowadays not only have access to capital. ‧. through their government, but are furthermore increasingly able to access it through. y. Nat. advanced market institutions such as listings at the US stock exchanges. (Khanna/. sit. Palepu 2004, 4) By moving abroad, they effectively overcome the restraints of their. n. al. er. io. domestic environments. (Luo/ Tung 2007, 484) Local restraints mostly exist in the. i n U. v. form of underdeveloped financial institutions and banking systems.. Ch. engchi. A second explanation for the increasing FDI outflows is global competition emerging on the home-markets of emerging- and developing country MNCs. The increasing competition from outside forces them to go abroad in search for market access and to secure knowledge to safeguard their respective position on the home market. China is exemplary for this situation: „Chinese market-seeking investments are common in both developing and developed countries. One of its main reasons is excessive competition in the domestic market, based on the large number of foreign TNCs entering and investing in China. This has caused profit margins to fall and resulted in overcapacity in some mature industries, such as textiles or clothing,. 21.

(29) pushing Chinese firms to find new markets overseas (...).“ (Krusievicz 2011, 7) However, type of investment activity, its formation and structural components, differ according to the respective economic parameters in host countries. (Khanna et al 2004, 1) Another aspect is the increasing need to secure resources vital to the sustained economic growth in an emerging economy. Again, China is a case in point. Chinese companies, channel a large share of their investment into resource extraction activities in other developing countries:. 政 治 大 „Of particular interest to the West is China’s growing expansion into 立 Africa’s oil markets (…) China is actively seeking resources of every kind;. ‧ 國. 學. copper, bauxite, uranium, aluminium, manganese, iron ore etc. are all objectives for acquisition for Beijing.“ (Taylor 2007, 3). ‧. y. Nat. These resources are needed for China’s manufacturing- and heavy industry.. sit. Other emerging economies likewise follow an interest based investment policy. India. er. io. - in concurrence with its economic focus on IT- channels large shares of its OFDI into. al. high-tech- and knowledge intensive industries. (Luo et al 2007, 487) Russia,. n. v i n somewhat similar to China, C has mainly invested into h e n g c h i U resources and strategic commodities- not least with regards to its geo-strategic positioning in regions such as Central Asia. (Gammeltoft 2008, 11) Brazil also developed its OFDI in line with its economic structure- channeling its OFDI into oil, gas, metals, mining, cement and food/ beverages. (Sauvant et al 2009, 8-9) Thus, investment behavior not only reflects upon a country’s means for investment, be they financial or other, but also on needs and long-term strategies.. 22.

(30) 4.3 Geographic Distribution of Emerging Country Investment The geographic distribution of emerging OFDI flows shows a clear trend towards Asia becoming the predominant source of OFDI outflows. It has thus overtaken both Latin America and the Caribbean in this regard. These investments are largely channeled into other developing or emerging economies. (Battat/ Aykut 2005, 1; Aykuth/ Ratha 2004, 154) Most notable are the investments undertaken by Chinese and Indian investors in Africa, where they focus on a wide range of industries but primarily on the extraction of natural resources and production of foodstuffs such as grains and palm oil. (Rocha 2007, 23; Meier zu Selhausen 2010, 22). 政 治 大 Nevertheless, companies from emerging- and developing countries increasingly also 立 invest in the developed markets. These flows mostly include investments into service. ‧ 國. 學. industries, and trade supporting industries. China underlines this fact through its large trade supporting investments in developed markets for its multinational companies:. ‧. y. Nat. „In developed countries, an access to markets remains one of the main. sit. motivations for investment. (...) Chinese investments were mainly. er. io. defensive market- seeking, e.g. FDI following trade, as firms set up. al. v i n Cforh later entrants, after customer loyalty, while 2000, they were mainly engchi U aimed at raising company profiles in a large market, where growth n. foreign affiliates in order to serve their customers better and to increase. potential for their companies had been identified, e.g. trade following FDI.“ (Krusiewicz 2011, 8) According to Sauvant et al (2009, 4) the number of developing economy Multinational Companies is above 21,000, while those from transition economies measured a total of 2,000. Out of the firms from developing economies, around 3,500 were from China, 1,000 from Russia, 815 from India and 220 from Brazil. This particular group of Brazil, Russia, India and China is also referred to as the BRIC countries. This group among developing- and transitioning economies has. 23.

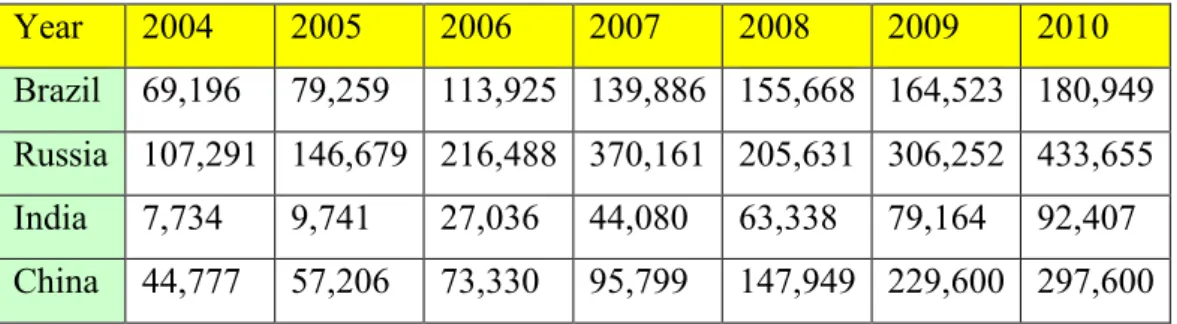

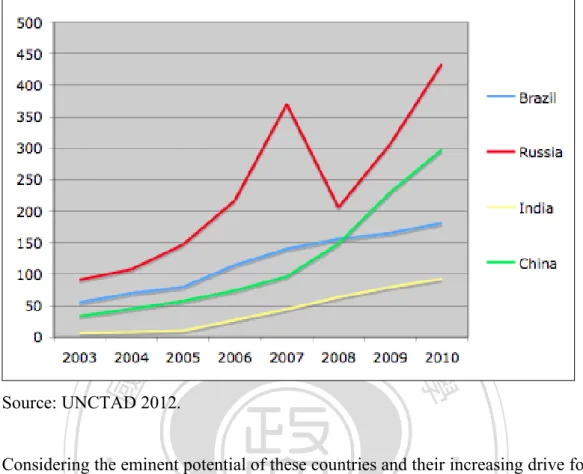

(31) experienced vast growth in recent years and now contributes 13 per cent of global GDP- highlighting the potential of emerging economies in worldwide FDI flows. (Deutsche Bank Research 2009, 1) Due to their overall economic importance, the BRIC countries are a special case. According to Deutsche Bank Research (2009, 1), these countries have (taken together) accumulated external assets surpassing US$ 4.1 trillion in 2007, which marks a 45 per cent year on year increase. Even though assets grow fast-paced, the outward FDI in flows and stocks from these countries remains small to date. Yet as their economic potential grows, so will likely do their OFDI outflow as they already account for the majority of the Southern FDI total. (Dicken 2007, 39) Furthermore, many BRIC. 政 治 大. countries actively seek to promote and further this development through policy. 立. reforms:. ‧ 國. 學. „Often, various liberalizing and promotional measures have been put in place by governments of emerging market countries in a phased manner,. ‧. starting with an approval process and ceilings for OFDI that are. sit. y. Nat. progressively set higher until they are abolished.“ (Sauvant 2005, 647). er. io. For China as well as India, their respective catch-up potential seems to leave sufficient. al. room for further expansion of OFDI- China nevertheless outpacing its peers Brazil. n. v i n C h2) A table of OFDIUfrom BRIC economies according and India. (DB Research 2009, engchi to UNCTADstat serves to exemplify this trend until 2010.. Figure 5: OFDI Outflows BRIC economies 2004-2010, in US$ millions Year. 2004. 2005. 2006. 2007. 2008. 2009. 2010. Brazil. 69,196. 79,259. 113,925 139,886 155,668 164,523 180,949. Russia 107,291 146,679 216,488 370,161 205,631 306,252 433,655 India. 7,734. 9,741. 27,036. 44,080. 63,338. China. 44,777. 57,206. 73,330. 95,799. 147,949 229,600 297,600. Source: UNCTAD 2012.. 24. 79,164. 92,407.

(32) Figure 6: BRIC outflows are taking off, in US$ millions. 學. ‧ 國. 立. 政 治 大. Source: UNCTAD 2012.. ‧. Considering the eminent potential of these countries and their increasing drive for. sit. y. Nat. investments in developed economies, the BRIC countries underline the paradigm shift in Foreign Direct Investment, as some emerging economies increasingly become key. io. n. al. er. players beyond their direct geographic vicinity. (Yeung/ Liu 2008; Khanna et al 2006;. i n U. v. Tung/ Luo 2007) While other countries have also facilitated extensive investments in. Ch. engchi. developed markets, the case of China needs to be seen before a somewhat different background given its size and economic vigor:. „China’s re-emergence and economic status is often compared to the growth performance of “miracle” Asian economies that came into their own during the post-War era and carved a niche for themselves in the global economy. While there are many commonalities, this comparison is not entirely correct because, unlike them, China’s economic ascent as it is progressing is going to be to the status of an economic superpower.“ (Das 2008, 4). 25.

(33) 5. China’s (Economic) Rise 5.1 China’s Economic Development The Chinese economy is the second largest economy worldwide. It recently surpassed Japan and Germany and has had the by far fastest growing economy for the past 30 years. Its growth rates average around ten per cent per annum- even projected into the future a steady growth of the same magnitude is foreseen, making it bound to become an economic superpower.4 The primary accumulation of the Chinese economy as we know it today has taken. 政 治 大 export-oriented economy, 立as has been the case for many of the second-tier newly. place between 1978 and 2008. This stage is characterized by the development of an. ‧ 國. 學. industrializing countries in Asia. The first region to be developed was the Pearl River Delta during the 1980s, followed by the Yangtze River Delta in the 1990s and the Bohai Bay area since 2000. Analyzed with consideration of Hu’s line5, dividing China. ‧. between Heilongjiang and Guangxi, one can find that the impact of development in. y. Nat. this stage has been greater on the eastern regions, which are home to the coastal. sit. development areas of Pearl River Delta, Yangtze River Delta and Bohai Bay area.. er. io. (Yang 1990, 231; Waters 1997, 76). al. n. v i n C hPRC underwent little Before the 1970s however, the e n g c h i U successful economic. development. In its early years, the People’s Republic relied on an economic policy closely resembling that of the Soviet Union. It promoted heavy industries and collectivization against all odds, leading to unsatisfactory results- reaching a peak in the Great Leap Forward campaign. The Great Leap, aiming to use a process of rapid industrialization and collectivization to jumpstart China into a modern communist society, led to economic devastation and famine. The country, closed off to the world, started to adjust its economic policies only after Deng Xiaoping attained the position of paramount leader after 1978. He opened China to the world and is considered to be. 4. Refer to: IMF (2011). World Economic Outlook Database, Report for Selected Countries and Subjects for further information. 5 黑河-腾冲线 (Hēihé-téngchōng xiàn). 26.

(34) the architect of economic reforms labeled as the “Socialist Market Economy”. (Shirk 1993, 24) After 1987, the Chinese government gradually allowed economic initiatives to emerge in Southern China. Within the coastal regions of the south, The People’s Republic established Special Economic Zones (SEZ). (Zeng 2010) In these zones, a liberal and market oriented economic setup was offered to investors. The primary aim of the SEZ was to attract foreign investments, or business activities by Chinese-foreign JointVentures. The production of an SEZ is primarily meant for exports and thus adheres to market principles. In a sense, these zones were early gateways for foreign investors into China, offering tax incentives and access to cheap labor beyond the borders of the. 治 政 大 among all developing countries: 立. SEZ. This developmental model has led China to become the largest recipient of FDI. ‧ 國. 學. “In recent years, FDI to China accounts for 1/4 to 1/3 of total FDI inflow to developing countries. Foreign investment has become an important. ‧. source for China’s investment in fixed assets. Its share in total annual investment in fixed assets grew from 3.8% in 1981 to its peak level of 12%. Nat. er. io. sit. y. in 1996.” (Fung/ Iizaka/ Tong 2002, 2). Induced by the inflow of capital, economic momentum emerged, which helped China. n. al. Ch. i n U. v. to position itself as the largest producer of consumer goods and simple industrial. engchi. products. China's economic development is to this day based around this industry. Exports and investment are crucial caterpillars for its growth – as has been the case in the last four decades. (DB Research 2011) China has come a long way since the early reforms started in 1978, which were directed at the agricultural sector. Price reform and financial rewards were to induce increasing initiative in farmers and rural enterprises. In 1984 this idea was extended to also cover the industrial sector- allowing companies to use any surplus production for their respective benefit. This move set in motion the growth of a fairly liberal market of foodstuffs and consumer goods, while at the same time maintaining a dual track system with an additional state controlled market in place. (Brandt 2008, 10). 27.

(35) At the XIV. Party Congress in the fall of 1992, the Socialist Market Economy was enshrined as the central economic policy objective. This affirmation towards continuous reform set in motion an unprecedented inflow of FDI from abroad. This went hand in hand with a gradual liberalization of China’s policies toward FDI. Before the establishment of four SEZs in Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Shantou and Xiamen, the National People’s Congress had already granted legal status to foreign investments in 1979.6 In 1984 fourteen other coastal cities and Hainan Province were awarded SEZ status and finally in 1986 wholly foreign owned enterprises were permitted to operate in China. (Fischer 2006) The adoption of the “Provisions of the State Council of the PRC for the. 政 治 大 freedom to import inputs such as materials and equipment, the right to retain and 立 swap foreign exchange with each other, and simpler licensing procedures (…)” (Fung. Encouragement of Foreign Investment”, entailing “(…) preferential tax treatment, the. ‧ 國. 學. et al 2002, 3), were the first crucial steps towards providing actual incentives to foreign investments rather than simply allowing them to operate. This in turn also. ‧. served the interest of the Chinese government. Beyond aspects of job creation, China. y. Nat. managed to link its FDI promotion activities to its domestic objectives. These. sit. objectives include technology transfer and progress in areas with substantial. er. io. weaknesses. Through a “Guiding Catalogue of Foreign Investment Projects”,. al. investments were channeled into areas of national interest to help upgrade products,. n. v i n C hand control pollution. improve efficiency, save energy (Perkins Coie LLP 2012; Fung engchi U et al 2002, 4). As can be seen from the discussion above, China has turned into the most important host to Foreign Direct Investments from Western Countries, as well as from Taiwanese and overseas Chinese businesses. Its policies towards FDI have developed gradually and over time, from mere permission of FDI inflows to active promotion and subsequent selection: „China’s policies toward FDI have experienced roughly three stages: gradual and limited opening, active promoting through preferential 6. Law of the People’s Republic of China on Joint Ventures using Chinese and Foreign Investment (1979). 28.

(36) treatment, and promoting FDI in accordance with domestic industrial objectives. These changes in policy priorities inevitably affected the pattern of FDI inflow in China.“ (Fung et al 2002, 5) However, China has not remained a manufacturing giant for cheap consumer products. As is already indicated above, China managed to upgrade its own industrial potential and extend its domestic capabilities, slowly moving up the value chain. Yet, as the traditional export markets for Chinese products undergo economic reshuffling and experienced continuous crisis since the year 2000, China was again forced to reconfigure its economic strategy.. 政 治 大. 5.2 China’s Evolving Role in a Global Economy. 立. ‧ 國. 學. In the eyes of most observers, China remains the manufacturing giant, responsible for sucking up a large share of industrial jobs in developed countries. However, as of. ‧. recently China has seen its development from global vacuum for investment put on reverse by the promotion of its domestic consumers market and by becoming a major. er. io. sit. y. Nat. investor to other countries itself.. The 12th Chinese five-year plan marks a decisive turning point in China’s economic. n. al. i n U. v. development. The country increasingly aims to develop its own consumers market and. Ch. engchi. set free the potential of its large population. Before the background of the severe Financial Crisis of 2008, the plan refocused attention away from increasingly problematic export destinations (US and EU) towards the domestic market. The new development path favors local consumption and key industries in services and particularly consumer products. (Xinhuanet 2011) As Guanyu Li and Jonathan Woetzel of McKinsey’s Shanghai office note: “China’s recently announced 12th fiveyear plan aims to transform the world’s second-largest economy from an investmentdriven dynamo into a global powerhouse with a steadier and more stable trajectory.” (Li/ Woetzel 2011) In order to create such a national consumers market, the 12th five-year plan aims to establish greater income parity and promotes inclusive growth to overcome the. 29.

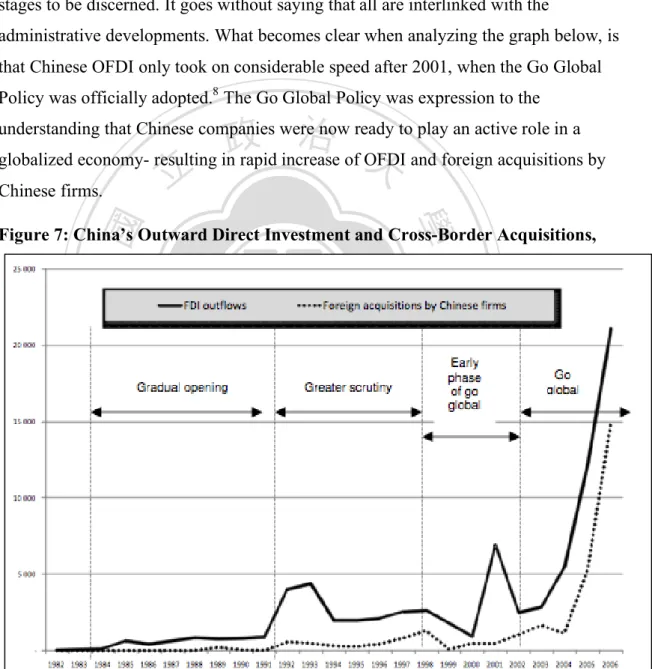

(37) growing wealth gap. To this end, China has developed two strategies. The first is to move up the value chain in the eastern regions, including promotion of advanced sectors: biotechnology, new materials, new energy (nuclear as well as solar and wind), new IT, and high-end manufacturing (particularly aerospace and telecom). (Stanley/ Xu 2011, 2) Simultaneously, China speeds up its development of the poor western regions started in 2000 by setting incentives for companies to move further inland.7 This will create jobs for former working migrants, increase the domestic customer base to the hinterland and encourage domestic spending. (KPMG 2011, 2) China also targets a higher quality growth, as questions of sustainability arise. While lifting millions out of poverty, China has paid a dear price by infringing on. 政 治 大 resource depletion through extensive energy use and related pollution of air, water and 立 land. Not only are current generations already suffering from exploitation of environmental standards and preservation. Development has come at the expense of. ‧ 國. 學. resources, but the cost to future generations is yet unknown. Therefore “(…) the low carbon sector, and other priority sectors identified in the plan, will benefit from. ‧. increased investment and incentives.” (Stanley et al 2011, 4). y. Nat. sit. China is increasingly focused on its own domestic markets with a potential customer. er. io. base above one billion people. Setting free its domestic potential would allow China. al. to decrease its dependency on overseas markets in Europe and the US. But China also. n. v i n Clucrative increasingly looks abroad for opportunities and starts to become U h e n ginvestment i h c an investor itself. When the Chinese government initiated its Open Door Policy in 1979, it had virtually no FDI outflows. Its FDI emerged slowly between 1982 and 1991, but the annual sum did not exceed $1 billion at any point (Buckley/ Clegg/ Cross/ Voss, Zheng 2007). This was due to government policies, which restricted both investment approval and foreign exchanges, and the weak competitiveness of Chinese firms. Outward investment policies were relaxed between 1991 and 1994, only to be tightened again until 1995, in order to cool the rate of domestic economic expansion. In 1998, the outflows declined again, because of the Asian Economic Crisis, which led to 7. 西部大开发, Xībù Dàkāifā.. 30.

(38) increased foreign exchange controls and an economic downturn in most neighboring countries. With the official introduction of an investment policy, Chinese FDI flows accelerated markedly. Since 2003, Chinese investments have accelerated even further, making China one of the fastest growing investors to the world (OECD, 2006). Through its investments, China actively pursues its interests abroad. As a transitioning economy however, China has interests different from those of developed nations. Its status as an emerging economic powerhouse and the related need for resources, knowledge and technology associated with such an economic rise, shape its investment policy abroad.. 政 治 大. 5.3 Motivation behind Chinese Investments. 立. ‧ 國. 學. Given China’s background as an emerging economy, we can identify three basic motivations with regards to investment flows from China. These interests are not. ‧. mutually exclusive, but may apply in concurrence with one another:. sit. y. Nat. The first is the efficiency motivation. China has accumulated the largest sum in foreign. io. er. reserves worldwide and is keen to put them to use in investment opportunities. (Buckley et al 2007) This aspect may be counted as one central push and pull factor,. n. al. i n U. v. severely affecting incentives to move abroad and the investment decision as such.. Ch. engchi. (Dunning et al 2008) This view is further extended by Liu/ Buck/ Shu (2005), who link the national development path to the individual investment decision. From this point of view, each investment corresponds to- and is in line with national development goals. OFDI would thus not only be a singular event, but heavily enmeshed with larger strategic implications. (Child/ Rodrigues n.d.) Second is the learning- or catch-up motivation. Companies from southern countries do not generally enjoy an advantage with regards to technology or knowledge- this is what sets them apart from the preceding surges in FDI. (Goshal/Bartlett, 2000) Theorists therefore state that the basic interest must be that of a catching up strategy. (Gammeltoft 2008) China promotes national champions, which enter the foreign market in order to improve their competitiveness and global reach (Berger et al 2008;. 31.

(39) Ramkishen, Kumar & Virgill 2006). As Matthews (2006) underlines, these companies have a clear strategic interest in investing abroad. In the case of China to developed country OFDI this must lie beyond the plain acquisition of resources of production and financial interests. (Deng 2004) Learning processes, especially when it comes to Chinese investment, may play a key role and could be the overriding factor for an investment decision. (Rui/Yip 2008; Milleli et al 2008) As Morck (2007) describes, Chinese companies increasingly need this intellectual capital in order to sustain against international competition on their home market too. Li (2009) adds that China is in need to acquire foreign technology abroad not only with regard to its position in the world market, but also in order to further the readjustment process of its growth mode towards sustainable development. (Chuang 2010). 政 治 大 The third is the market access motivation. Buckley et al (2007) find that the 立 acquisition of strategic intellectual capital initially played little role for Chinese OFDI.. ‧ 國. 學. Companies much rather pursued basic economic strategies, such as market share development. This may be especially true for a country like China. The Chinese. ‧. economy is based on export oriented growth, thus pursuing market access and. y. Nat. increasing market share in key markets like Europe may be one of the major. sit. motivations behind Chinese OFDI to developed countries. (Zhan 1995/ Buckley et al. er. io. 2007) Before this background the acquisition of local brands can be seen as a market. al. access strategy, using the brand value as a strategic asset for gaining market share by. n. v i n Cahwell established brand. selling own products through As Deng (2008) notes, the U i e h n g c is based on their need to acquire brands asset seeking conduct of Chinese companies that allow them to access markets via strong and well-established networks.. Chinese global investments are said to mostly focus on resource-seeking, which is in line with the need for supplies to sustain continuing economic growth. As some of the Chinese investment destinations, for example the European Union, largely do not possess such strategic assets the investment in such areas does not comprise a noteworthy aspect. It may however be said, that resources could be interpreted in a broader sense encompassing technological assets and knowledge. Thus the acquisition of technology or knowledge based products could be interpreted as resource-seeking investment as well.. 32.

數據

Outline

相關文件

You are given the wavelength and total energy of a light pulse and asked to find the number of photons it

Teachers may consider the school’s aims and conditions or even the language environment to select the most appropriate approach according to students’ need and ability; or develop

volume suppressed mass: (TeV) 2 /M P ∼ 10 −4 eV → mm range can be experimentally tested for any number of extra dimensions - Light U(1) gauge bosons: no derivative couplings. =>

incapable to extract any quantities from QCD, nor to tackle the most interesting physics, namely, the spontaneously chiral symmetry breaking and the color confinement..

• Formation of massive primordial stars as origin of objects in the early universe. • Supernova explosions might be visible to the most

The difference resulted from the co- existence of two kinds of words in Buddhist scriptures a foreign words in which di- syllabic words are dominant, and most of them are the

(Another example of close harmony is the four-bar unaccompanied vocal introduction to “Paperback Writer”, a somewhat later Beatles song.) Overall, Lennon’s and McCartney’s

DVDs, Podcasts, language teaching software, video games, and even foreign- language music and music videos can provide positive and fun associations with the language for