Yu, C.-S., Tao, Y.-H., Ex

pl

or

i

ng

t

he

Fi

r

m’

s

De

c

i

s

i

on

on

e

-Marketplace

- A Network-Economics Perspective, International Conference of

Information Management, Taipei, Taiwan, May 28, 2005

Exploring the Firm’

s Decision on e-Marketplace

- A Network-Economics Perspective

C. S. Yu,Institute of Business Administration and Department of

Information System, Shih Chien University

Y. Tao,Department of Information Management, National University of

Kaohsiung

Abstract

This study explores whether and how the network economics affect an e-marketplace adopter’sdecision on staying in or existing from the current e-marketplace as well as a candidate’sdecision on planning to or not to join an e-marketplace. Accordingly, eight hypotheses are developed. 2500 firms were sampled from Top 1000 firms and NeiHu Technology Park Factor analysis for a survey, and 202 valid responses were collected. The questionnaire items were analyzed via Factor analysis. The hypotheses were tested against t-Test, which validated six of the hypotheses. A conclusion and implications are also discussed at the end.

Key terms: e-marketplace; network economics; network market, firm’s decision

1. Introduction

Speedy e-commerce development and e-technology breakthrough have accelerated online transactions conducted in both intra-business and inter-business processes within past few years. As a result, a large portion of traditional buying and selling activities has been shifted into the electronic buying and selling on cyberspaces named electronic marketplaces (e-marketplaces). From the viewpoint of economics, an e-marketplace reduces the search cost that buyers have to pay to find suitable products, prices, and related data as well as the marketing cost that sellers

have to pay to attract prospect customers and promote products. Depending on the role of the owner, there are three types of e-marketplaces: buyer-driven, seller-driven, and independent e-marketplaces. In which, the first two types of e-marketplaces are also called participant-owned e-marketplaces. Buyer-driven e-marketplaces are established by a consortium of buyers that are looking to procure products from their upstream suppliers via the Internet, while sell-driven e-marketplaces are established by a consortium of suppliers that aim to sell their products to their downstream via the Internet. Independent e-marketplaces are those established by the third parties who are neutral and simply aim to generate revenues through operating the marketplace on behalf of buyers/sellers.

Just as the development of the B2C e-commerce, dot-coms only can survive when they are able to give consumers’ economic advantages, usually savingor making money. For buyers, saving money is the main motives of conducting business on the Internet. It is widely recognized that buyers can do huge catalogue searches in few seconds, easily compare prices between multiple vendors, and configure products with the lowest transaction costs. For sellers, making money is the critical reason of launching business on the websites. They can reach large customers worldwide at no additional cost, easily create sizeable catalogues virtually, build complicated customer orders in minutes, and offer better customer services with automated tools, such as promptly offering the customer e-mailconfirmation when receiving each customer’s order, punctually fulfilling the order when the order is scheduled, etc.

Based on the above discussion, it is obvious that the determinant for e-marketplaces successfully competing with traditional (physical) demand-supply channels depends heavily on how much economic benefit can be delivered to the customers. Although the factor of economics is vital for B2B developments in the e-marketplace, among numerous literatures only few academic articles have investigated e-marketplaces from the perspective of economics (Gebauer, 1999; Hung, 2002), particularly network economics (Yu, 2004). Accordingly, unlike most of e-marketplace studies that emphasized on business performance, customer’s satisfaction, competitive strategy, specified industry analysis, technology adoption, etc., this work investigates e-marketplace from the perspective of network economics.

2. Literature Review

(or service) increases in correspondence to the rise in the number of consumers (Economides, 1996). For instance, if the number of consumers of a product (or service) is lower than 1,000, the value of the product (or service) may be only around US$ 1.8. This value can climb to $2.6 if the number of consumers exceeds 2,000, and may jump to $4 when the number of consumers boosts to 3,000. That is, the market formed with consumers of this product (or service) hold a special economic phenomenon named network economics. In this so-called network market, the effectiveness of the product (or service) will increase every time as long as a new consumer is added to the network. The analysis of network market can even date back to 1970s (Squire 1973, Rohlfs 1974). The typical examples of a product that exhibits network market are telephone, telecommunication, television, newspapers, electronic mail systems, packaged computer software, bulletin board system, online game, .NET Messenger service such as MSN, and the like.

The effectiveness of a network market can be direct or indirect. Direct effectiveness is derived from consumers of the same product while indirect effectiveness is derived from a diverse range of products or an increase in complementary products and services. Since some differences between network and common markets are generated from the external characteristics of the network while others are the result of market competition (Glimstedt, 2001; Brynjolfsson and Kemerer, 1996), theories on network externality or transition cost need to be explored for comprehension. Using network externality or transition cost to explore their effects on technology/e-commerce/telecommunication/Internet is not a new concept and has been extensive discussed by many scholars (Clemons and Kleindorfer, 1992; Choi, 1994; Wang and Seidmann, 1995; Economides, 1996; Choi and Thum, 1998; Hoppe, 2000; Kauffman et al., 2000; Au and Kauffman, 2001). One common practice of these works is that individual user is used as an analysis unit.

2.1 Network externality

In economics, when the action of a person (or company) can directly impact anotherperson’s(orcompany’s)economic utility,then thisperson (orcompany)is deemed to haveanetwork externality on otherpersons’(orcompanies’)behaviors (Allen, 1988; Brynjolfsson and Kemerer, 1996; Au and Kauffman, 2001). This externality can impact positively or negatively. Positive externality means that the affected person’s(orcompany’s)economicutility willbeincreased whilenegative externality displays a reduction in the economic utility of the affected persons (or companies). Network externality is only a component of external characteristics of

network market, which was first formally introduced by Rohlf’s(1974)and laterwas clearly described by Katz and Carl (1985). Network externality is a phenomenon –it depicts the utility derived by the consumer from the product (service) and the rises/fall in concert with a change in the number of consumers using the product (service). Farrell and Saloner (1986) highlighted in their study that network externality exists not only in a single product (service) but also in other compatible products (services) and that the benefits to existing consumers will increase when others consume compatible products (services) e.g. mobile phone networks, computer operating systems, IBM compatible computer, and so on.

The positive impact of network externality depicts the utility of the product (service) increases with the increase in the number of consumers. The increased number of people using this product will attract consumers who have not yet used the product. This is a positive influence of network externality. However, as more and moreconsumersuseacompany’sproductorservice,theconsumerwilleventually feel‘lessloved’dueto thehigh demand forservicefrom alimited poolofresources. This is the negative influence of network externality. According to Farrell and Saloner (1985), network externality yields four types of effects:

(1) Reinforcement in product quality: Reinforcement in product quality means that the quality of the product is increasing when the market share of the product is growing.

(2) Reinforcement in after-sales service: Reinforcement in after-sales service means that when a product’s market share increases the quality of after-sales service reinforces.

(3) Reinforcement in cost reduction: The popularity of a product (service) will cause numerous similar products’ (services’) production, which triggers extensive competition in the market.

(4) Negative impact of overcrowding: The increase in consumers might adversely impact the production capability, service personnel and information systems designed to serve the original market scale.

2.2 Transition cost

In an environment in which technology evolves stochastically over time, any potential user who makes a technology choice must consider whether the best available technology today will remain a good technology in the future. This is particularly important when the technology choice is largely an irreversible one. The

possibility of being stranded by other people who adopt a different and incompatible technology is increasing. Consequently, transition cost is considered as the cost of switching from one technology to another. Jackson (1985) contended transition cost involves the psychological, material and economic costs incurred by the customers when they switch suppliers. Since the transition cost can also originate from the consumer’s need for compatibility between the newly purchased product and an earlier investment, these investments could be material investments, such as investments in human resources, long term capital investments or investment in a company’sworkflow (Jackson,1985);orpsychologicalinvestmentslike emotional attitude or acknowledgement (Weiss and Anderson 1992).

To a business, transition cost is the outlay to be incurred when the customer switches from the incumbent supplier to a new one (Heide and Weiss 1995). Every business, either a global conglomerate or a family-run business, is subject to a myriad of choices. This in turn gives rise to transition costs. The only difference between the costs incurred by a global conglomerate and a family-run business is the actual outlay and the impact of the transition on the company. When an individual switches from one mail service to another, it only involves the transition of a mail account with minimal transition costs. On the other hand, if a company intends to switch to a different mobile phone supplier, then the transition cost might be relatively higher. By the same token, if a company plans to switch from an existing e-procurement platform to another, then the transition cost is expected to include contract exit cost, depreciation on existing infrastructure, retraining of personnel, loss of accumulated discounts and bonuses, etc (Shapiro and Varian, 1998). Accordingly, if the estimated transition cost is high, the chances of a company switching e-marketplaces will be lowered. Referring to the Klemperer’s(1995) study, there are six types of transition costs, including compatible cost with existing infrastructures, switching cost among suppliers, training cost, uncertainty cost of an unused product, loss of discounts, bonuses, member credits and other incentives, and psychological cost.

3. Research Hypotheses and Questionnaire Design

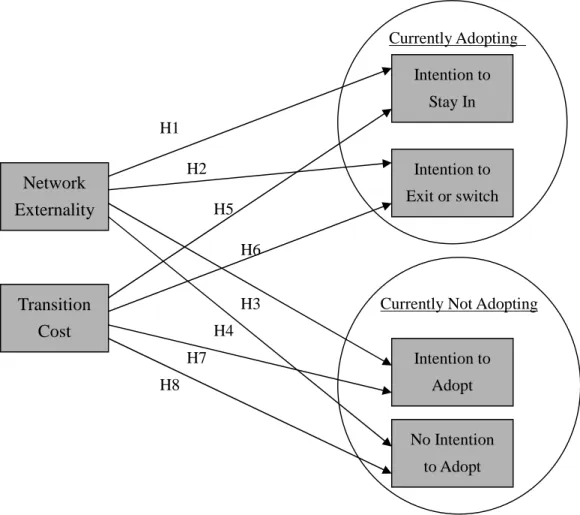

Based on the literature above, our research structure is established with eight hypotheses developed as sketched in Figure 1:

H1: There is no significant relationship between network externality and an adopted-firm’s decision to continuously stay in the current e-marketplace.

H2: There is no significant relationship between network externality and an adopted-firm’s decision to exist or switch to another e-marketplace.

H3: There is no significant relationship between transition cost and an adopted-firm’s decision to continuously stay in the current e-marketplace.

H4: There is no significant relationship between transition cost and an adopted-firm’s decision to exist or switch to another e-marketplace.

H5: There is no significant relationship between network externality and a not-adopted-firm’s decision to plan to adopt an e-marketplace within a year. H6: There is no significant relationship between network externality and a

not-adopted-firm’s decision to continuously not join any e-marketplace.

H7: There is no significant relationship between the transition cost and a not-adopted-firm’s decision to plan to adopt an e-marketplace within a year. H8: There is no significant relationship between the transition cost and a

not-adopted-firm’s decision to continuously not join any e-marketplace.

Figure 1. Research Structure

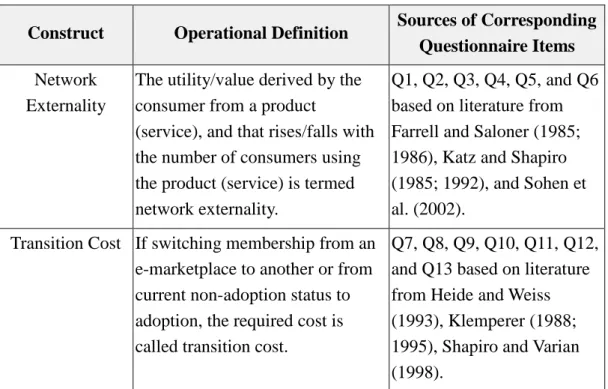

Two constructs of network externality and transition cost are defined in Table 1 Corresponding questionnaire items used to assess network externality and transition

Intention to Stay In Intention to Exit or switch Network Externality Transition Cost No Intention to Adopt Intention to Adopt H5 H6 H8 H7 H1 H2 H3 H4 Currently Adopting

cost are drawn from related literature as shown in Table 1, which are evaluated on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The questionnaire comprises two sections. The first section contains 13 questions as summarized in Tables 1, and is to investigate the two constructs perceived by responded companies. The second section, with 12 questions, is to collect basic data for each responded company and understand whether the responded firm has joined an e-marketplace, which type of e-marketplaces they joined, and they are planning to stay, exit, or switch if they already participate in e-marketplaces as well as they are planning to adopt or continuously not adopt e-marketplaces if they not yet adopt e-marketplaces

Table 1. Definition and Sources of Research Constructs

Construct Operational Definition Sources of Corresponding Questionnaire Items

Network Externality

The utility/value derived by the consumer from a product

(service), and that rises/falls with the number of consumers using the product (service) is termed network externality.

Q1, Q2, Q3, Q4, Q5, and Q6 based on literature from Farrell and Saloner (1985; 1986), Katz and Shapiro (1985; 1992), and Sohen et al. (2002).

Transition Cost If switching membership from an e-marketplace to another or from current non-adoption status to adoption, the required cost is called transition cost.

Q7, Q8, Q9, Q10, Q11, Q12, and Q13 based on literature from Heide and Weiss (1993), Klemperer (1988; 1995), Shapiro and Varian (1998).

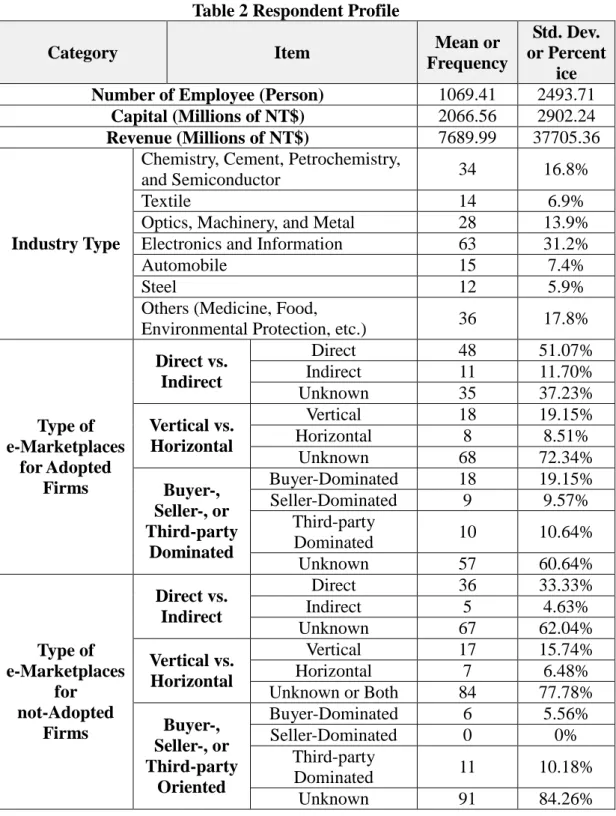

4. Statistics Analysis and Hypotheses Test

2500 firms were sampled from top 1000 Taiwanese firms and the resident firms of Nei-Hu Technology Park in Northern Taiwan during the period of mid June and late October, 2004. A questionnaire was to sent to each of the 2500 firms, and a total of 295 responses were received, but 93 of them were invalid due to incomplete answers, which translated to an 8.08% of valid response rate. Among the 202 valid responses, 94 responses have already joined at least one e-marketplace. The profile of these 202 firms is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2 Respondent Profile

Category Item Mean or

Frequency

Std. Dev. or Percent

ice Number of Employee (Person) 1069.41 2493.71

Capital (Millions of NT$) 2066.56 2902.24

Revenue (Millions of NT$) 7689.99 37705.36 Chemistry, Cement, Petrochemistry,

and Semiconductor 34 16.8%

Textile 14 6.9%

Optics, Machinery, and Metal 28 13.9% Electronics and Information 63 31.2%

Automobile 15 7.4%

Steel 12 5.9%

Industry Type

Others (Medicine, Food,

Environmental Protection, etc.) 36 17.8% Direct 48 51.07% Indirect 11 11.70% Direct vs. Indirect Unknown 35 37.23% Vertical 18 19.15% Horizontal 8 8.51% Vertical vs. Horizontal Unknown 68 72.34% Buyer-Dominated 18 19.15% Seller-Dominated 9 9.57% Third-party Dominated 10 10.64% Type of e-Marketplaces for Adopted Firms Buyer-, Seller-, or Third-party Dominated Unknown 57 60.64% Direct 36 33.33% Indirect 5 4.63% Direct vs. Indirect Unknown 67 62.04% Vertical 17 15.74% Horizontal 7 6.48% Vertical vs. Horizontal Unknown or Both 84 77.78% Buyer-Dominated 6 5.56% Seller-Dominated 0 0% Third-party Dominated 11 10.18% Type of e-Marketplaces for not-Adopted Firms Buyer-, Seller-, or Third-party Oriented Unknown 91 84.26%

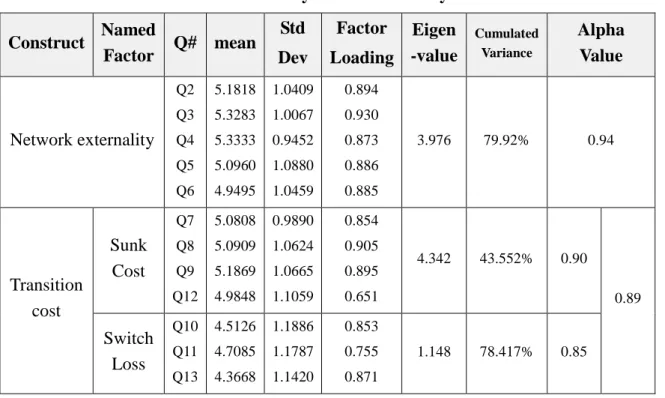

4.1. Reliability and Factor Analysis

content reliability is confirmed. Additionally, the computed Cronbach Alphas for all dimensions exceed 0.7377, indicating the content consistency within the questions relating to each of the factors. The criterion for each sorted question pertaining to each factor is that its eigenvalue must be greater than one and with an intra-factor loading greater than 0.6. Therefore, after conducting the factor analysis through the SPSS software, Q1 is discarded because of failing to meet the criterion and questions 7-13 are grouped into two factors under the construct “transition cost”as displayed in Table 3. Notably, each of two factors is named by best reflecting the context of corresponding items.

Table 3 Reliability and Factor Analysis

Construct Named Factor Q# mean Std Dev Factor Loading Eigen -value Cumulated Variance Alpha Value Network externality Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 5.1818 5.3283 5.3333 5.0960 4.9495 1.0409 1.0067 0.9452 1.0880 1.0459 0.894 0.930 0.873 0.886 0.885 3.976 79.92% 0.94 Sunk Cost Q7 Q8 Q9 Q12 5.0808 5.0909 5.1869 4.9848 0.9890 1.0624 1.0665 1.1059 0.854 0.905 0.895 0.651 4.342 43.552% 0.90 Transition cost Switch Loss Q10 Q11 Q13 4.5126 4.7085 4.3668 1.1886 1.1787 1.1420 0.853 0.755 0.871 1.148 78.417% 0.85 0.89

4.2 Hypothesis Testing

The eight hypotheses are tested against t-test via SPSS, which is summarized in Table 4. Clearly, Table 4 confirms that only hypotheses H1 and H2 are rejected. That is, the transition cost has no effect on either adopted- or not-adopted firm’s decision, in whatsoever way. However, the network externality does affect an adopted-firm’s decision to either continuously stay in current e-marketplace or to exit or switch to another e-marketplace.

Adopted-Firm’s Decision Not-Adopted-Firm’s Decision Intent to

Stay In

Intent to Exit

or Switch Intent to Adopt

No Intent to Adopt

Yes No Yes No Yes No Yes No

t-Value 5.357 4.756 N/A1 2.245* (H1) Network externality N/A 4.756 5.350 N/A -2.206* (H2) 4.844 4.836 N/A 0.024 (H3) Transition cost N/A 4.836 4.819 N/A 0.055 (H4) 5.355 5.014 N/A 1.354 (H5) Network

externality N/A N/A 5.047 5.015 0.142 (H6)

4.774 4.736 N/A 0.162 (H7) Transition cost N/A N/A 4.772 4.615 0.765 (H8) ***

P value < 0.001;**P value < 0.01;*P value < 0.05;1Not Applicable

5. Conclusions

This work explored the organizational decision on e-marketplace from the network-economics perspective. A big difference from previous studies is that we took an organizational view instead of individual decision behavior as an analysis unit. From the collected data, we discovered that the transition cost does not play a critical role in either e-marketplace-adopted or not-adopted firms. The main reason may be that current e-marketplaces are built upon open and standard Internet and Web-based technology with usually an annual-based membership, which implies that the sunk cost in e-marketplace decision is trivial and contract termination cost is also very low. As long as firms realize tangible benefits in terms of prospect commerce chance and size to be gained from switching to another e-marketplace, the transition cost, such as training cost, loss of accumulated discounts, bonuses, member credits or other incentives, is not a showstopper. Likewise, as long as concrete benefits to be gained from joining the e-marketplaces are not significant, a not-adopted firm will remain standby and be reluctant to adopt the e-marketplace in the near future.

Although the theory of network externality perfectly fits individualconsumer’s attitude-behavior, this study also unearthed that this theory may completely fit a

firm’s attitude-behavior. In other words, network externality only impacts an adopted-firm’sdecision on continuously staying in current e-marketplace or planning to exit or switch to another one. The major reason may be attributed to that the individual user decision is more easily swayed by emotion attachment or peer pressure, and usually is made in a relative short time. In contrast, a collective decision in an enterprise results in minimization of the subjectivity and emotion.

References

1. Allen, D., “New telecommunications services: network externalities and critical mass”, Telecommunications Policy, 1988, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 257-271.

2. Hung, T. L., “Factors influencing the entrance into electronic marketplaces in enterprises -from Transaction Cost perspective”, Master Thesis of Institute of Information Management, Yuan Ze University, 2002.