New Financial Politics in Taiwan, Thailand, and Malaysia

Chengtian Kuo

Department of Political Science National Chengchi University

This paper is supported by the National Science Council of Taiwan, NSC 88-2418-H-004-001-S4.

Abstract

Based on the analytical framework of new institutionalism, this project compares the financial politics and institutional relationships in Taiwan, Thailand, and Malaysia. Financial politics and institutions include both those of banking and security markets. The major finding is that the financial crisis in these three countries was a result of the oligopolistic alliance among the state, political parties, conglomerates, and local factions. The alliance excluded the direct participation of foreign financial institutions and caused the distortions of local financial markets. However, institutional similarities and differences among these three countries existed. In Taiwan, the KMT had continually controlled the state, and been a major player in the banking and security markets. Being controlled by the KMT, the state financial regulators, such as the Central Bank and Securities and Futures Commission, could not effectively monitor and punish violators of market rules. New conglomerates established new banks and security companies. They earned handsome profits via privileged information and avoided state regulations through their representatives in the Legislature. Local factions contributed to the deterioration of local financial institutions, because of their close connections with the KMT and conglomerates during elections. Both Thailand and Malaysia had a similar institutional system as in Taiwan. But in Thailand, a non-autonomous state, patronage party system, financial conglomerates, and expensive local factional politics caused the financial crisis. By contrast, Malaysia suffered less and recovered faster than Thailand did. This was due to the fact that the Malaysian state was relatively autonomous, the UMNO had dominated its members and opposition parties, local factional politics was weaker, even though privileged conglomerates had weaken Malaysian financial systems.

Keywords

A Crisis Lurking behind the Success

The 1997 Asian financial crisis revealed that Asian economic miracles are not all the same. The Taiwanese miracle looked more durable than those of other first-tier Newly Industrializing Economies (NIEs) such as South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore, as well as those of the second-tier NIEs such as Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia. Many Taiwanese economists, then, rushed to find the economic reasons for Taiwan's resilience. These reasons included a successful industrial upgrading in the late 1980s, the prevalence of small and medium-sized enterprises, high domestic savings, a sound corporate financing, diversified export markets, and a foreign exchange reserve of over US$900 billion.1 It is true that, in terms of growth rates, Taiwan did better than its Asian neighbors after the crisis broke out. Taiwan registered a 4.9% growth rate, as compared to Korea's -7.0%, Hong Kong's -5.0%, Singapore's 0.7%, Malaysia's -7.5%, Thailand's -8.0%, and Indonesia's -15.3%.2

However, lurking behind the cozy growth rates were serious structural problems in Taiwan's credit and stock markets, which were reflected by other indicators. Taiwan's stock price indexes dropped 33.7% from June 1997 to June 1998, which was lower than Hong Kong's -37.4%, Malaysia's -45.1%, and Indonesia's -43.1%, but higher than South Korea's -23.3%, Singapore's 28.2%, Thailand's -31.2, and the Philippines' -30.4%. The figure after June 1998 was even worse for Taiwan: Taiwan registered a continuous drop of -20.7%, while all other Asian neighbors registered two-digit growth rates between 11.0% (Philippines) and 91.8% (South Korea). Even Indonesia's figure of -7.6% looked more benign than Taiwan's. The exchange rate fluctuations told a similar story in comparison. From June 1997 to June 1998, the Taiwan dollar depreciated 13.9%, a drop greater than Hong Kong's 0%, a little smaller than Singapore's -15.3%, and much smaller than those of all other Asian countries. However, most of the currencies of other Asian countries bounced back faster than Taiwan's after June 1998. The Taiwan dollar's exchange rate appreciated by 6%, higher only than Singapore's 1.1% and Hong Kong's 0.1%, and lower than South Korea's 14.4%, Thailand's 12.9%, Malaysia's 7.5%, and Indonesia's 39.3% (Central

1

Paul C.H. Chiu, "ROC's Experiences in Responding to the Asian Financial Crisis," Economic Review, International Commercial Bank of China, no.304 (1998), pp. 1-7; Jiatong Shea, "Taiwan and the Asian Financial Crisis," The Central Bank Quarterly, no.20(June 1998),pp.5-10; International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Economic Outlook (Washington, DC: IMF,1998).

Bank of China 1999).3

The durability of the Taiwanese miracle was further undermined by two more facts. One is that Taiwan had similar financial crises before the 1997 crisis broke out. Since 1990 Taiwan had experienced almost yearly stock market crashes (averaging drops of about 44% in value). The other is that, in the period of 1997-1998, George Soros was present neither in Taiwan's stock market nor in its foreign exchange market. Nor was foreign capital important in Taiwan's stock market. Because of tight regulations, foreign capital constituted less than four percent of the total market value in early 1999.4

I do not suggest that international factors played no role in Taiwan's crisis in 1997-1998. Indeed, the reduction of trade with other Asian nations and a competitive devaluation pressure after July 1997 caused substantial damage to the trade-dependent Taiwanese economy. However, these international factors alone cannot well explain those economic crises before 1997 and the stagnation of the non-trade sectors after 1997 in the Taiwanese case, for which domestic institutional factors are probably a better explanation.5

Why Did Malaysia Do Better Than Thailand?

This paper also aims to provide a political-institutional explanation for why the relatively dynamic economies of both Thailand and Malaysia suffered devastating blow from the 1997 financial crisis, and why Malaysia seemed to suffer less and recovered faster than Thailand did. In terms of the initial impact of the crisis on the economy, Thailand's real GDP growth rates for 1997 and 1998 were -1.3% and -9.4% respectively, as compared to its impressive averaged annual growth rate of 9.6% between 1986 and 1996. Its foreign exchange reserves were almost depleted from about US$30 billion in the mid-1990s to US$0.8 billion in August 1997. Thai currency depreciated from 26 baht to a dollar in March 1997 to 54 baht per dollar in

3

Central Bank of China. 1999. Monthly Report of Financial and Statistical Data, Taiwan, January 1999. Taipei: Central Bank of China.

4 United Daily News, February 20, 1999, p.1. 5

Yunhan Chu also offers a political-institutional explanation for the Taiwanese case. However, he underestimates the problems in the credit and stock markets, while overestimating the autonomy and capacity of the Taiwanese state. See Yunhan Chu, "Surviving the East Asian Financial Storm: The Political Foundation of Taiwan's Economic Resilience," in The Politics of the Asian Economic Crisis, ed. T.J. Pempel, (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1999).

January 1998. The index of Securities Exchange of Thailand dropped from 705 points in March 1997 to 459 points a year later.6

In Malaysia, its real GDP growth averaged 8.7% from 1991 to 1996. In 1997 and 1998, the growth rates were 7.8% and -7.5%. Malaysia's currency, ringgit, fell from RM2.5 per dollar in July 1997 to RM4.88 a dollar in January 1998, a loss of almost 50% of its value. Its foreign exchange reserve fell from US$28 billion in June 1997 to US$11.7 billion in May 1998. The KLSE stock market index fell from 1271 in February 1997 to 477 in January 1998; the market value of stocks lost about 66%.7

In terms of recovery, Thailand's GDP registered a positive 4.2% in 1999. Its currency rebounded to 37.8 baht to a dollar (45% of its pre-crisis value), foreign exchange reserves increased to US$31.9 billion, and stock market index rose by 12% as compared to the previous year. By contrast, Malaysia seemed to have a stronger recovery. Its GDP grew by 5.4% in 1999, ringgit's exchange rate rose to 3.8 per dollar (54% of its pre-crisis value), the amount of foreign exchange reserves was US$32.2 billion, and the stock market index rose by 79% as compared to the previous year.8 The Malaysian recovery was even more impressive given the fact that it did not ask for financial assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF). On 20 August 1997, when both the baht and Thai foreign exchange reserves hit the bottom, Thailand received from the IMF a $17 billion rescue loan (out of the $50 billion multiyear package loan).9

Focusing on international factors, economic explanations for the Asian financial crisis have come from both left and right. The leftists, represented by Bello, blamed the Asian financial crisis on too much and too fast capital liberalization. 10The rightists, represented by the IMF, criticized the Asian countries for too little and too slow liberalization. This paper suspects that both criticisms might have missed the target. 11The fact that serious financial crises had occurred in both Thailand and

6

www.mof.go.th/ther_2/index_ther.html, 4/12/2000; FEER 7/9/98, 67.

7 Neac.gov.my/neac/publications/curr.shtml, Neac.gov.my/neac/publications/action3r.shtml, 4/12/2000. 8 Taiwan Economic Research Institute, 1999, 2000, Guoji Jingji Dongtai Zhibiao (Indicators of

International Economic Currents), Nos. 564, 580, Taipei.

9

In 1997 and 1998, both Thailand and Malaysia received bilateral aid from Japan. However, due to Japan's larger investments in Thailand than in Malaysia, Thailand received more than three times the amount of aid than Malaysia did (www.mofa.go.jp/policy/oda/summary/1999/d_g2_02.html, 7/10/2000).

10

Walden Bello,."East Asia: On the Eve of the Great Transformation?" Review of International Political Economy, Vol.5, No.3 (Autumn 1998): 424-44.

11 Stanley Fischer, "The Asian Crisis: A View from the IMF." Address at the Midwinter Conference of

Malaysia before 1997 suggests that the 1997 financial crisis be in large part due to domestic reasons. The financial attack by international speculators, such as George Soros, was only the last straw breaking the camel back. In the early 1990s, Thailand's economy ran into deep recession due to overheated investment in the real estate and stock market. In Malaysia, the economy suffered from high ratio of non-performing loans in the mid-1980s. Therefore, the major cause of the Asian financial crisis is more domestic than international. This domestic cause is the rise of new financial politics in these Asian nations.

New Financial Politics and New Institutionalism

For many Third World countries, a new breed of financial politics emerged in the 1980s, which gradually replaced the old industrial and financial politics and became the cornerstone of political economy in these countries.12 Susan Strange has analyzed in detail the rise of international "casino capitalism" in the 1980s, which caused significant declines of state power over the financial capitalist in Western countries.13 With the proliferation and fast expansion of financial instruments in world markets, capital became divorced from production and assumed a life of its own. This financial revolution made possible that profits derived from capital transaction could be independent from and larger than industrial or agricultural production. Also, a distinctive nature of the international capital flow after the 1980s was the dominance of freewheeling private capital over public loans, which were closely monitored by governments and the IMF. The rapid expansion of private capital greatly increased the instability of domestic and international financial systems.14

The political and economic impact of the new financial revolution is most prevalent on Third World countries and has also generated significant differences

www.imf.org/external/np/speeches/1998/012298.htm.

12 The most representative work on the old financial politics is probably the book edited by Stephan

Haggard, Chung H. Lee, and Sylvia Maxfield, eds., The Politics of Finance in Developing Countries (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993). The old financial politics refers to the politics involved in the distribution of credit to industrial production, while the new financial politics is different not only in terms of sectors (banking, securities, and foreign exchanges) but also in terms of institutions. For the sake of simplicity, I treat the old financial politics as part of the industrial politics. Financial politics is also different from money politics in that the former refers to state-business connections in the financial businesses, while the latter is not restricted to financial businesses.

13 Susan Strange, Casino Capitalism (Oxford, U.K.: B. Blackwell, 1986).

14 Miles Kahler, "Introduction: Capital Flows and Financial Crises in the 1990s." In Miles Kahler, ed.

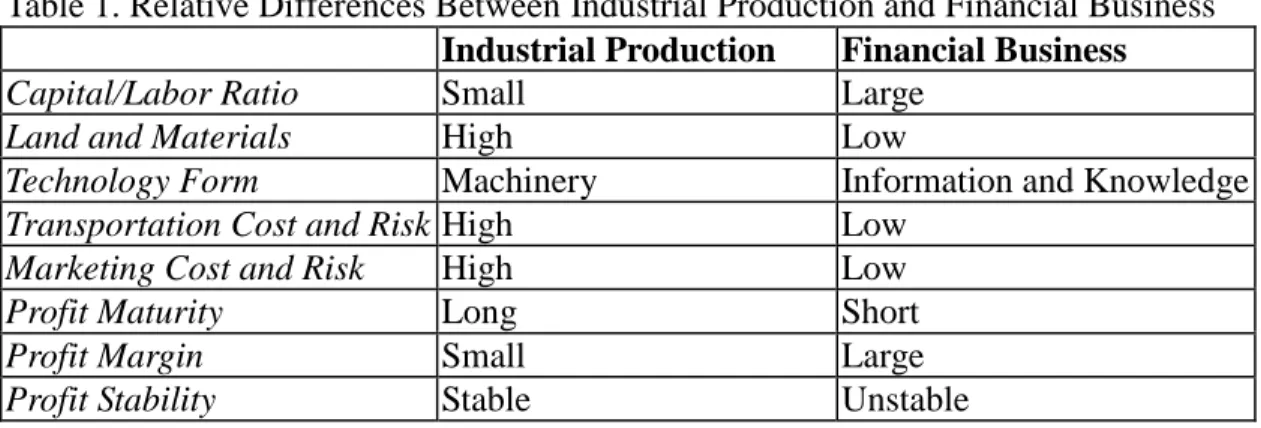

between the old industrial politics and the new financial politics. Table 1 summarizes the relative differences between industrial production and financial business (mainly banking, security investment,15 and foreign exchange transaction). Based on the comparison between industrial production and financial business, Table 2 contrasts the differences between industrial politics and financial politics.

[Table 1 about here]

In the past, capital and labor were treated equally as the main production factors. Neither alone can generate profit for the owner. For most Third World countries, their comparative advantage in labor-intensive industries means that their capital/labor ratio is relatively low. Industrial production requires land to build factories and materials to produce final products. The major technology form exists in machinery. The transportation of voluminous materials, machinery, and final products necessarily incurs various costs and risks. Once the products are made, they needed to be marketed and sold to downstream producers or consumers, which again incurs certain costs and risks. The profit maturity is comparatively long between the production order is received and the final profit being realized. For instance, an industrial firm may receive an overseas order in the winter, look for materials, loans, workers, and machinery in the spring, process the materials in the summer, ship the products to overseas markets in the autumn, and finally receives its payment in the winter. The profit margin for standardized labor-intensive products, which most Third World exports consist of, is usually low between 3% to 6%. While the profit margin is low, the demand for such low-end industrial products is often quite stable, thus creating stable income streams for producers.

By contrast, financial business (e.g., banking, security investment, and foreign exchange transaction) requires a relatively large amount of capital and small number of employees (composed mainly of financial analysts, accountants, and lawyers). This results in a relatively large capital/labor ratio for the financial business. It requires relatively little office space and almost no material inputs. The main technology form is the information about various financial markets and the knowledge to conduct

15 "Security" is a broader term than "stock." Securities consist of government bonds, corporate

debentures, shares (stocks), and a few other financial instruments. Except for specific identification, "security" and "stock" will be used interchangeably.

financial transactions in particular business environments. Because of the development of modern communication system, the transfer of capital across borders incurs very little physical cost and risk - those caused by unexpected political interference excluded. The profit margin in financial business is relatively large. Security investments in matured economies can expect a return of more than 10%. It is usually higher in those fast-growing economies. Foreign exchange speculation can generated even higher returns as evidenced by the windfall profits earned by international speculators in the European currency crisis in the early 1990s and the Asian currency crisis of 1997. High profit margin also means great instability in income stream, which is the nature of the casino capitalism Susan Strange referred to.

These significant differences between industrial production and financial business lead to quite different dynamics between industrial politics and financial politics. Table 2 summarizes these differences.

[Table 2 about here]

In developing countries, the implication of low capital/labor ratio for industrial politics centers around class politics, e.g., the encouragement of entrepreneurship, the allocation of scarce capital, and the suppression of or compensation for the labor, which expands with labor-intensive industrialization. Class politics occurs when the state decides to which entrepreneurs the incentive policies will apply, and whether the state chooses to suppress or compensate the workers. Industrial entrepreneurs will lobby for assistance from the state to resolve problems of land acquisition and material imports. The assistance can take the form of low taxes on land acquisition or use, redrawing of zoning areas, and low tariffs on material imports. Political maneuver is required in the formulation and implementation of all these policies. Since most of the technology of industrial production in developing countries is imported, entrepreneurs can lower their cost of production by asking for low tariffs on technology imports. The politics of tariff adjustment is involved again. The import of machinery, raw materials, and the export of final products require reliable and efficient transportation systems. Therefore, the state needs to engage in long-term and extensive infrastructure building. Politics occurs during infrastructure project design, contracting, and implementation process. Since most developing countries do not have the capacity to do marketing and retailing in world markets, the cost and risk of

marketing is handled by trading companies from industrialized countries or by OEM (original equipment manufacturing) arrangements with foreign buyers. Because the maturity of profit for industrial production is relatively long, entrepreneurs need state assistance in the provision of hard currencies to buy raw materials, technology, and to pay workers, taxes, and transportation costs. The politics of preferential loans emerges at this juncture. The profit margin for industrial production is relatively small for the standardized export products of developing countries. Therefore, if entrepreneurs intend to maximize their profit, they need to engage in tax evasion or the lobbying for low taxes at all stages of production. Finally, since the profit of industrial production is often determined by world market fluctuation, the government can help the industries to weather the market fluctuation through assistance measures. This leaves a large room for political decision as to which industry or firm, and how much the assistance should be provided. State assistance may not come when the collapse of a few firms does not affect the industry as a whole, or when the collapse of a few industries (e.g., sunset industries) does not seriously affect the whole economy. If the state does provide assistance, other firms or industries may form political pressure to stop or to expand such assistance, thus, enlarging the state's political cost for such action.

By contrast, financial business entails a different set of political consideration and behavior. Class conflict is diffused because winners and losers in the financial business are determined less by their class nature than by their asymmetrical access to privileged information. Due to the high capital/labor ratio, the state faces less pressure from the employees of financial business than that of labor-intensive industries. Even if it does, political pressure generated by the white-collar employees of financial business may be less explosive than that of industries. Financial politics emerges when owners of financial business need the state's assistance to expand their capital supply via loose monetary policies or expanded business activities. The lobby activities will concentrate in a few monetary and regulatory agencies of the state. The financial business does not need to spend much political effort to acquire land and resources. Because the technology form of financial business exists in knowledge or information, owners of financial business will compete for privileged information in order to maximize their profits. Political bargaining occurs between financial business owners and a few monetary and regulatory agencies. Since there is little transportation cost and risk associated with financial transaction, little politics is involved here.

Similar is the politics associated with marketing cost and risk. Due to its relatively short profit maturity, the success of financial business is highly dependent on privileged information from the state. The legitimate profit margin of financial business is relatively large, especially that of the security market. However, financial business owners can further maximize their profit by manipulating accounting and tax information. The politics occurs when the state decides to enforce its regulations or to collaborate with the financial business owners by cooking the accounting books. Even for the banking business in which interest rates are regulated by the state, the profits generated from manipulating collateral assessment, lenient loan standards, and distorted accounting procedures can be enormous. Also, to protect this large profit from competitors, existing owners will lend strong support for market entry restrictions, especially against foreign players. Finally, since financial business provides capital to all other businesses in the economy, and it is sensitive to contagion effect, the state has little choice but to offer quick and comprehensive assistance to the financial business when a major financial crisis occurs. The political cost for such assistance is widely distributed across the unorganized taxpayers through tax increase, or to the future taxpayers through long-term government bonds.

From the above comparison, financial politics stands out differently from industrial politics in terms of the small number of key decision-makers involved, large and unstable profit, and relative simplicity of state-business interaction. It addresses to the major concerns of new institutionalism more than industrial politics does.16 In developing countries where the public/private sphere is not clearly divided, financial politics offers a fast track to fame and fortune. All it takes is to engage in the collection of privileged information from the state and to prevent the state from effectively implementing its monitoring and enforcement mechanisms. The collective action of collusion is relatively easy to reach since the number of key decision-makers is small, while the cost of collusion is evenly distributed across the unorganized or future taxpayers.

As suggested by Haggard and Maxfield in their analysis of the financial politics

16 This paper follows the neo-institutional analysis. The major works include: Sue E.S. Crawford and

Elinor Ostrom, 1995, "A Grammar of Institutions." American Political Science Review, 89 (3 September): 582-600; Douglas C. North, Structure and Change in Economic History (New York:W.W.Norton, 1981); Douglas C. North, Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 1990); Oliver E. Williamson, Markets and Hierarchies:Analysis and Antitrust Implications (New York: The Free Press, 1975); Oliver E. Williamson, The Economic Institutions of Capitalism (New York : The Free Press, 1985).

in Third world: "the effectiveness and efficiency of government action depend heavily on the 'disciplinary capacity' of the state and that no general rules on the benefits of liberalization can be established without reference to the broader institutional and political milieu."17 The actual operation of financial politics may vary across developing countries according to the internal attributes of and interaction among the institutional actors of the state, political parties, conglomerates, and local factions. For the state, I will examine the political independence and administrative capacity of the regulatory agencies for financial business, i.e., the central bank, the finance ministry, and security exchange commission. However, the independence and capacity of regulatory agencies does not come out automatically, it is formulated and conditioned by party politics. The nature of the ruling party and the relationship between the ruling party and opposition parties may define the scope and intensity of financial politics.

Since the state is rarely insulated from the society in most developing countries, the power and composition of the conglomerates may affect the operation of financial politics, which by nature is a game for the chosen few. With the "Third Wave of Democratization" knocking on the door of developing countries, elections become more competitive for political parties. Local factions, which serve as canvassers of votes, may affect the election outcome one way or the other. In order to pay off the local factions for both legitimate and illegitimate vote canvassing in increasingly competitive elections, ruling political parties are more likely to expand the room for financial politics to cover campaign expenses. Finally, similar to protectionist industrial politics, financial politics is prevalent when the domestic financial markets are concentrated and when foreign financial players are restricted or excluded from the markets.

The following sections will compare the cases of Taiwan, Thailand and Malaysia to elucidate the above theoretical arguments. The time period being examined is from the 1980s to the 1990s, with more emphasis on the 1990s. The last section summarizes the comparison and draws policy implications for financial reforms.

Major Actors and Their Institutional Attributes in

17 Stephan Haggard, Chung H. Lee, and Sylvia Maxfield, eds., The Politics of Finance in Developing

Taiwan

18I define the scope and major arguments of this paper in the following ways. First, among Taiwan's financial markets, I study the credit market and the stock market, excluding the insurance market and the informal financial market. In the credit market, the major actors are individual and corporate borrowers, public and private banks, foreign bank subsidiaries, credit unions, farmers' and fishermen's associations (their credit departments), as well as their regulators such as the Central Bank, the Ministry of Finance, the Legislature, and related semi-public enterprises. In the stock market, the major actors include individual and corporate investors, stock and investment companies, foreign investors, and government funds, as well as their regulators. In addition to these actors, our research focus and major arguments concentrate on those formal and informal institutions, which influence and constrain the interactions among these actors. Formal institutions include relevant constitutional provisions, laws, executive orders, and organizational structures. Informal institutions consist of norms, habits, and mutual expectations. These actors and institutions together constitute the Taiwan financial markets of this paper.

Secondly, the KMT (Kuomingtang, the nationalist party) maintains more cooperative than conflictive relationships with other major actors in the financial markets.19 I assume that the ultimate organizational goal of the KMT is to maintain its status and privileges as the ruling party. Although internal conflicts exist within the party, the KMT must suppress them and has successfully done so in order to mobilize enough votes in elections. In Taiwan's peculiar electoral history, rules, and culture, this means the KMT has to pump in massive amount of money to engage in legal (e.g., propaganda) and illegal (e.g., bribing voters and vote-collectors) mobilization activities. 20 Where does the money come from? Since political liberalization began

18 This section is a revised version of Chengtian Kuo, Shangmao Chen, and Zonghau Huang, 2000,

"The Politics of Taiwan's Financial Reforms." Manuscript.

19 On Taiwan's institutional relationships among the state, the KMT, conglomerates, and local factions,

see Chengtian Kuo, and Tzengjia Tsai, “Differential Impact of the Foreign Exchange Crisis on Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea.” Issues and Studies, 34(11/12, 1998), pp.144-180.

20 Central to Taiwan's electoral history, rules, and culture is the single-nontransferable-vote rule

(SNTV). The island is divided into many medium-sized electoral districts. Each district can elect one or more representatives, depending on the size of the district. The SNTV system encourages the formation of local factions for vote mobilization. Vote-collectors (zhuangjiao) are those local vote-mobilizers who, through their networks of relatives and friends, can deliver a guaranteed amount of votes for candidates.

in the 1980s, the clandestine transfer of government funds to the KMT's coffers has been greatly reduced, due to the enhanced monitoring by opposition legislators. Alternatively, through its expanded party enterprises,21 the KMT began to find profit opportunities from the enlarged and lucrative financial markets in order to finance rising campaign expenses. Party legislators, bureaucrats, and KMT party enterprises assumed the responsibility of fund raising. The KMT has manipulated various formal and informal institutions to extract campaign funds at the expense of the public, and thus contributed to the major distortions of Taiwan's financial markets.

Thirdly, the state has become both a passive and active collaborator in distorting Taiwan's financial markets. During the martial law period, the bureaucracy dominated the Legislature in the economic policymaking process. Furthermore, the scale of and the number of participants in the financial markets were small. Laws and regulations governing the financial markets were few and simple. However, by the end of authoritarian rule, the Legislature had asserted its control over the bureaucracy. The bureaucracy became increasingly subject to the political influence of legislators and had to tolerate, and even collaborate with, the distortions of the financial markets. Critical among the government bureaucracies is the Central Bank, which since the 1970s has lost its financial leadership and political independence. Taiwan's current political environment does not allow for administrative neutrality. The bureaucracy will continue to tolerate the market distortions, with occasional implementation of superficial reforms. But when major economic crises occur, a committed new leader emerges, or the ruling party changes hands, the bureaucracy will be able to reclaim its neutrality and effectively monitor and regulate the financial markets.

Fourthly, Taiwan's conglomerates grew rapidly in the mid-1980s and have become major players in Taiwan's policy-making process.22 Those conglomerates, which make profits based on market protection or government licensing, tend to become actively involved in politics in order to protect or expand their established interests. These business activities include real estate development, construction, petrochemicals, steel, transportation, insurance, stocks, and banking. These

21 Lizhen Qiu, "Guomingdang Dangying Jingji Shiye Fazhan Lishi Zhi Yenjiu 1945-1996" [A Study of

the History of the KMT Economic Enterprises 1945-1996] (MA. Thesis, National Taiwan University, 1997) and Ganlin Xu , "Zhenzhi Zhipei Huo Shishang Luoji" [Political Domination or Market Logic]. Taiwan Shehui Yenjiu Jikan 28 (December 1997), pp. 175-208, provided detaile studies of the history of the KMT enterprises.

22 For a succinct history of Taiwan's conglomerates, see Chenpu Duan ed., Taiwan Zhanho Jingji

conglomerates influence policymaking through campaign contributions to friendly legislators, or by sending their own representatives to legislative bodies at various levels. These representatives then dominate the relevant committees, assuming the roles of both umpire and player. In addition, these representatives can take advantage of the supervisory role of the legislature over the bureaucracy in order to influence the implementation of specific laws. Since there is no effective norm or law governing the conflict of interests at various levels of representative bodies, the political and economic influence of conglomerates will continue to grow in Taiwan's political economy.

Due to the nature of financial transactions, the distorting influence of conglomerates is most prominent in these financial markets. In contrast to the importance of fixed capital in agricultural, mineral, and manufacturing production, the access to and control over relevant information is critical to the operation of financial markets. In the credit market, information access and control will affect the credit of borrowers and the value of collateral, the trust of depositors on banks, and the supervision of government agencies over credit institutions. Similarly, in the stock market, information access and control will influence stock prices and the ability of government agencies to monitor illegal trading activities. I do not suggest that conglomerates can always get access to the right information and process it correctly. Nor do I suggest that conglomerates have no conflict of interests among them. I do suggest, however, that by establishing strong political and economic networks, Taiwan's conglomerates have much better access to these kinds of information than average economic actors, and have made exorbitant profits at the expense of the latter. Fifthly, during the authoritarian rule, Taiwan's local factions played a critical role in local elections (at the provincial, county, city, and town levels).23 In order to maintain its legitimacy, the KMT had to form a patron-client relationship with local factions. With democratization proceeding rapidly in the 1980s and 1990s, the political influence of local factions expanded as well, and spilled over to the financial markets. So far, however, the influence (and distorting effect) of local factions has been limited to local credit markets, such as credit unions, farmers' associations, and fishermen's associations. They have had only very limited or indirect influence over the national credit and stock markets. Therefore, this paper will not elaborate on the

role of local factions, except in the case of local credit market.

Finally, financial liberalization is skewed in Taiwan's financial markets. The liberalization of capital flow proceeded at a fast pace in the 1980s. But various investment barriers have persisted against those foreign firms that intend to build up market networks in Taiwan. These investment barriers include the limitation on foreign ownership of local banks and stocks, high capitalization requirements, the limited scope of business activities, etc. The constraints imposed on foreign firms in the financial markets have protected local banks and stock companies from significant competitive pressure. But the "hot money" circulating in the financial markets has indirectly served to aggrandize the influence of the oligopolistic alliance, which is the dominant player in the markets.

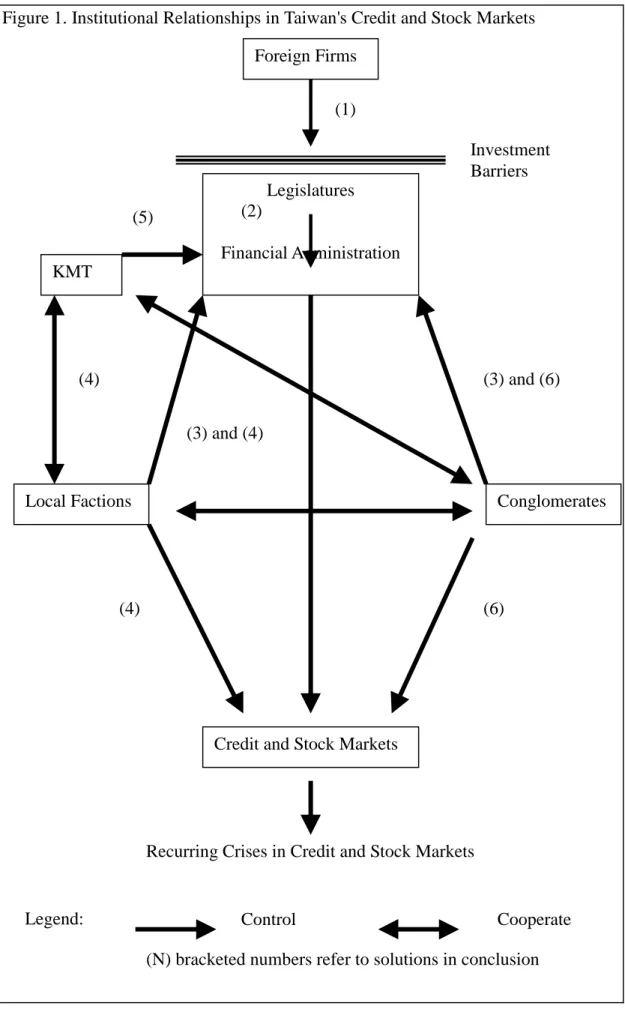

Figure 1 summarizes the above description of major actors and their relationships.

[Figure 1 about here.]

Distortions in Taiwan's Financial Markets

This section will describe the distortions in Taiwan's financial markets, including both the credit market and the stock market. The main problems with the credit market are the high percentage of non-performing loans, the expansion of bad loans, and the frequent occurrence of bank-runs. The major problem with the stock market is its frequent and large price fluctuations, a detailed description follows.

The Credit Market

24By February 1999, the average percentage of non-performing loans25 in Taiwan's seven largest public banks was 4.91%, about US$9.45 billion, a new record in

Bianqian [Factional Politics and Taiwan's Political Development] (Taipei: Yuedan ,1995).

24 In Taiwan, the official definition of credit (financial) institutions include domestic (large) banks,

medium business banks, local branches of foreign banks, credit unions (cooperative associations), farmers' associations (their credit departments), fishermen's associations (their credit departments), investment and trust companies, postal savings system, and life insurance companies, see Taiwan Statistical Data Book, (1998), pp.149-50.

25

According to the revised definition of the Ministry of Finance, non-performing loans include two parts: one is the amount of principals not paid back on due days; the other is the amount of loans whose interest has not been paid for more than three months. The percentage of non-performing loans is the amount of such loans divided by the total amount of all loans. See Xuewen Li “Sheme Shi Yufang Bilu” [What is the Percentage of Non-Performing Loans?], Shangye Zhoukan, no.501, (1997), p.64..

Taiwan's banking history.26 The sixteen new private banks accumulated on average 3.49% non-performing loans in their portfolio, totaling about US$2.37 billion.27 These numbers will continue to rise, as many of these loans were used indirectly to finance failed stock speculation last year28 and the economic toll of the September 21 earthquake skyrocketed.

Although these numbers were relatively small as compared to those of other Asian countries (all exceeded 10%) after the exchange crisis broke out, the comparisons should also be made within the country. Before 1993, the average percentage of non-performing loans in Taiwan's private and public banks was kept below 1%. By 1994, the percentage had increased to 1.5%, and it increased by 1% per year afterwards to 4.47% in 1998.29 At that rate, the percentage will approach those of other Asian countries in just five years. The earthquake of September 21 will be gas on the fire.

The worsening of the credit structure was even more serious at the local level. According to statistics published by the Central Deposit Insurance Corporation of the Finance Ministry, the average percentage of non-performing loans in farmers' associations was 6.7% in 1996. The number increased to 9.2% in 1997, and 11.7% in 1998. The same statistics for credit unions increased from 6.13% in 1996 to 7.8% in 1998. The total amount of such loans was estimated to be over US$5 billion.30

As a result of the increase in non-performing loans, the amount of bad loans rose sharply. The amount of bad loans is calculated by the difference between the amount of non-performing loans and the amount of collateral attached to the loans. Before the 1980s, Taiwan's banks adopted very stringent collateral conditions for loans. Loans required collateral (real estate, machinery, liquid assets, etc.) of about the same value as the amount of the loans, and banks usually deliberately undervalued these assets. Therefore, banks incurred very little loss even if borrowers were defaulted. Since the 1980s, however, due to the institutional factors discussed in the next section, banks began to relax the collateral conditions by lowering the value requirement and by more generously assessing the value of collateral. Furthermore, as stock market transactions expanded in the 1980s, banks began to accept stocks as collateral.

26 For simplicity, the exchange rate between the US dollar and the Taiwan dollar is calculated at 1:32. 27 In 1992, the government allowed the establishment of new private banks. Before then, most of

Taiwan's banks were state-owned.

28

China Times, March 16, 1999, p.1.6.

Therefore, when the stock market crashed in 1998 and stock prices tumbled by half, the banks wound up with a larger amount of bad loans than they expected. By the end of 1998, a conservative estimate of the amount of bad loans of all banking institutions (national and local) was about US$94 billion, half of the total amount of non-performing loans.31

In September 1998, as a result of the increase of non-performing loans and bad loans, Moody's Investors Service downgraded the credit ranking of Taiwan's ten banks.32 Uncertainty in the credit institutions have led to twenty five bank-runs at national banks and local credit institutions, an average of about once every other month, since August 1995.33

The Stock Market

Taiwan's stock market was established in 1962. But its size and the number of participants were small before the mid-1980s. The stock market indices were below 1,000; the total stock value was no more than US$17 billion; and fewer than 474,000 people participated in the market. Since 1987, the year the martial law was lifted, stock prices have inflated rapidly. In February 1990, the stock market index reached its all-time high of 12,682, the total stock value was more than US$193 billion (1989 figure), and more than 4.2 million people became stock buyers. But in the next eight months, the index fell to 2,485, and the total stock value fell by 56.6% to US$83.8 billion. The 1990 stock crash was not unique in Taiwan's stock market. From 1990 to 1998, there was on average one big crash every year. The average percentage of the drop in value was about 44%.34

In addition to the above statistics, four sets of statistics reveal the weaknesses of Taiwan's stock market. First, from 1988 to 1997, Taiwan's stock turnover rate averaged about 350%, much higher than its counterparts in Singapore, Hong Kong, New York and Tokyo, where the number was usually below 100%. The high turnover

30 See <http:/www.cdic.gov.tw/list.html>, April 1999; and China Times, March 30, 1999, p.1, 6. 31 China Times, March 10, 1999, p.1.

32

Shuping Ren, “Yinhang Yingjianye Mianlin Yanzhong Chongji” [Banks and Construction Companies Facing Serious Challenge], Shangye Zhoukan, no.564 (1998), pp.31-32.

33 See Ruixiang Wang, “Gaixuan Fengbao Zheng Weixie Nonghui Jinrong” [Re-election Storm Is

Threatening the Finance of Farmers' Associations], Shangye Zhoukan, no.476 (1997), pp.30-32; and United Daily News, July 8, 1999, p.3

34 Renhe Lin, Gupiao Touzi De Weiji Chuli [The Crisis Management of Stock Investment] (Taipei:

Lian-Jing, 1998); and Taiwan Stock Exchange Corporation on the Internet at < http://w3.tse.com.tw>, March, 1998.

rate means that most of Taiwan's investors are short-term speculators. Secondly, the stock price/dividend ratio for the same period of time averaged about 32:1, lower than Japan's 54:1, but higher than those of Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, and New York, all of which were below 20:1. The high price/dividend ratio implies that Taiwan's stocks are over-priced. Thirdly, from 1988 to 1997, about 28% of investors' capital came from short-term loans borrowed from various investment companies. After 1993, the figures fluctuated between 35% and 42%. The high ratio of loans in stock investment makes stock prices extremely sensitive to short-term changes in political and economic conditions.35 Finally, the average rate of fluctuation (the highest index minus the lowest in one year) of Taiwan's stock market for the period of 1989 to 1998 was 5.25%, higher than New York's 2.1%, Tokyo's 3.1%, Singapore's 3.0%, and Korea's 3.6%.36

Institutional Causes of Financial Market Distortions

The above description of the distortions in Taiwan's financial markets demonstrated that the 1997-1998 economic recession in Taiwan was not caused solely, if at all, by international speculators. Structural weaknesses made Taiwan's financial markets susceptible to changes in the external environment. Symptoms of such structural weaknesses had appeared frequently before the 1997 exchange crisis broke out. In other words, economic recession on the 1997 scale had happened before in Taiwan and will happen again if these structural distortions are not properly analyzed and tackled. This section argues that the oligopolistic institutional relationships among the KMT, conglomerates, local factions, and representatives are the major cause for Taiwan's financial market distortions.The Credit Market

Nationalist scholars may blame the distortions of Taiwan's credit market on excessive competition.37 From 1989 to 1998, the total number of credit institutions in Taiwan was 452, with 5,574 branch offices. On average, the branch offices have

35

Republic of China Stock Statistics 1997.

36

Lining Dai, “Toushi Zhengquan Shichang—Wenti Yu Duice” [Analyzing the Stock Market: Problems and Policies], Zhengquan Guanli 12:.9(1994), pp.1-15, and by authors' calculation.

increased by 225 every year since 1991.38 Although excessive competition may be one of the major causes for the low profit rates of these banks, it cannot fully account for their high ratios of non-performing loans. The oligopolistic alliance among the KMT, conglomerates, local factions, and representatives directly or indirectly encouraged these banks to accumulate bad loans.

First, the KMT was a major player in the credit market. During the authoritarian rule, the KMT maintained convenient access to the state's coffers to support a huge party machinery and astronomical campaign expenses. With the pace of democratization proceeding rapidly, the KMT had to find alternative sources of finance. Thus, the KMT expanded its party enterprises during the 1980s, and entered the banking and investment fields.39

The KMT's financial center is the Business Management Committee (BMC, Dangying Shiye Guanli Weiyuanhui), which was created in August of 1993 by the Fourteenth National Party Congress to coordinate the expanded party enterprises. By 1994, the KMT "had invested in 104 firms divided into ten special categories and administered by seven holding companies, as follows: (1) Central Investment Holding Company: financial, petrochemical, and general enterprises. (2) Kuang-Hwa Investment Holding Company: gas and technology enterprises. (3) Chii-sheng Industrial Company: construction and land development. (4) Jen-Hwa Investment Holding Company: special projects. (5) Kingdom Investment Holding Company: insurance. (6) Asia Pacific Holdings: overseas enterprises. (7) Hua-Hsia Investment Holding Company: communications. By the end of 1998, the total assets of KMT enterprises amounted to US$200 billion, which ranked fifth among Taiwan's 100 largest conglomerates. Through these holding companies, the KMT has been able to control and manage four banks: the Gaoxion Enterprise Bank, the Zhonghua Development Industrial Bank, Fanya Bank, and Huaxin Commercial Bank.40 In 1999, the Zhonghua Development Industrial Bank, which was the vault of the KMT's enterprises, ranked first among Taiwan's 150 financial institutions both in terms of net

News, March 1, 1999, p.4.

38 <http://www.boma.gov.tw/sat05doc.htm>, April, 1998. 39

The KMT's Central Investment Holding Company (Zhongyang Touzi Gongsi) was established in 1971. But its earlier investments concentrated on its own subsidiaries and petrochemicals. In the 1980s, all KMT holding companies rapidly diversified their portfolios to cover other sectors, especially the financial sector. See Ganlin Xu, "Zhenzhi Zhipei Huo Shishang Loji", pp.175-208.

profit rate (before tax) and of return on assets.41 Thus, the KMT was not only the largest banking institution in Taiwan, but also among the most profitable. This reminds us of Imelda Marcos' famous response to a reporter's question about the profitability of crony enterprises in the Philippines back in the early 1980s: "They are smarter people."

Secondly, conglomerates dominated the credit market. All sixteen new banks were established by Taiwan's conglomerates, with important political figures on these banks' boards of directors or as their shareholders.42 The political connections helped these banks to get operating licenses. About half of them, however, immediately adopted very lenient loan policies toward their subsidiary enterprises and toward these political figures.43 Most of these loans later became non-performing loans or bad loans. An epitome of these banking problems is the Fanya Bank, which was established by the Changyi Conglomerate in central Taiwan. The father (Tianshen Yang) and son (Wenxing Yang) of the conglomerate have served as representatives in local and national legislatures. In the 1990s, the bank provided large amount of dubious loans to local and national politicians for two purposes. One was to get legislative approval of large-scale construction project, including a gigantic entertainment park and an expensive subway system. The other was to climb up the political ladder. In 1994 Wenxing Yang successfully ran for the office of vice-speaker of the provincial assembly, defeating the candidate nominated by the KMT party central. But the Fanya Bank ran into deep trouble since and was taken over by the KMT in 1999.

Thirdly, local factions controlled the local credit market. During the authoritarian rule, the KMT formed a patron-client relationship with local factions. Local factions mobilized their relatives and friends to support KMT candidates (usually factional leaders) to confer legitimacy to the immigrant party from China. In exchange, the KMT granted licenses to these factions to operate oligopolistic businesses, such as credit unions, farmers' associations (including the credit department), fishermen's associations (including the credit department), and

41 Shangye Zhoukan, no.603 (1999), pp.76-131. 42

Shangmao Chen, Taiwan Yinhang Zhengce De Zengzhi Jinji Fenxi [A Political- Economic Analysis of Taiwan's Banking Policies] (MA. Thesis, National Chengchi University, 1998), pp.89-95.

43 Although banking regulations prohibit these new banks from lending money to their directors, some

banks circumvent regulations by lending money to each other's directors, with tacit agreements of such transactions reached under the table.

transportation companies.44 Local factions employed these oligopolistic rents to consolidate their factional cohesion and to buy votes in elections.

During the 1980s, the opposition party, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) made large gains at various levels of election by ideological appeals to independent voters. The pressure from the DPP and the SNTV voting rule made KMT candidates more dependent on factions for basic support. As competition among candidates increased, the price of votes rose as well. In the 1998 legislative election, the price of each vote averaged about US$80. The average number of votes required to elect a legislator was about 40,000. So, the initial cost for each candidate was about US$3.2 million. In addition, since candidates did not contact their voters directly, but via vote-collectors at different administrative levels, it was easy to add another US$3 million or more to the campaign expenses in order to beat the offer of their opponents.45

The cash flow for these election purposes usually came from local credit institutions, which were not subject to close supervision by the central government. Before each election, legislative candidates with over-valued collateral would apply for loans from credit institutions. After the election, these credit institutions would continue to give out easy loans to campaign contributors. Thus, non-performing loans and bad loans accumulated until bank-runs occurred.

Fourthly, representatives helped legalize credit market distortions. Before 1986, the Legislature was filled with representatives elected in mainland China before 1949, and had little influence in national policymaking process. In 1986, after a constitutional revision, the Taiwanese were able to elect one-third of the legislators. In 1992, the people of the island elected all legislators, with the exception of a few overseas representatives. Legislators began to assert their legislative power over the financial administration, especially after the lifting of martial law in 1987.

The financial administration lost its political autonomy in banking policies in two areas. One was the decline of the Central Bank's political autonomy in credit policies. Before the 1980s, the Central Bank was the highest authority in Taiwan's banking matters. In 1979, the Central Bank changed its institutional affiliation from the most powerful Presidency to the Executive Yuan, which was subject to legislative

44

Mingtong Chen, and Yunhan Chu, Quyuxing Lianhe Duzhan Jingji Difang Paixi Yu Shengyiyuan Xuanju [Regional Oligopolistic Economy, Local Factions, and Provincial Assembly Elections] (National Science Council Report, 1992), p.89.

45 The first book recording in detail the KMT's vote-buying machinery is written by a 24-year party

supervision and political influence. During the episode of licensing new banks in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Central Bank did not participate in the policymaking and implementation process; it was the Ministry of Finance that orchestrated the entire process. Then, in the revision of the banking law in April 1997, the Central Bank was further downgraded as an equal, if not lower, partner of the Ministry of Finance. Finally, in terms of the composition of the Central Bank's board of directors, I have found the rapid expansion of directors who were either government officials directly subject to political pressure or representatives of private banks. Together, they outnumbered state-owned bank officials and scholars on the board.46 The presidency of the Central Bank has also seen three turnovers in the past ten years, as compared to twice in the previous forty years.47 In other words, legislators preferred to work with and expand the power of the Ministry of Finance, which was subject to legislative supervision, than with the Central Bank, which had a tradition of political autonomy.

The other area where the financial administration revealed the loss of political autonomy to the Legislature was the revisions of the banking law. Before the 1980s, banking law revisions were minor,48 infrequent, and led by the financial administration; the Legislature usually rubber-stamped the bills. Since the mid-1980s, new legislators elected in Taiwan have asserted their political power by revising critical articles in the administration's bills or by submitting their own reform bills. In the 1985 banking reform, the Legislature revised four of the twenty-five articles proposed by the administration. In the 1989 reform, the administration proposed seventeen articles; sixteen were revised. And in the 1995 reform, the Legislature itself proposed and passed two important items of banking reform, against the wishes of the Ministry of Finance.49

Why would the Legislature assert its political power? It was because a small group of legislators were closely associated with the banking industry through directorship, shareholding, or loan relationships. Furthermore, since no effective conflict-of-interest laws have existed in the Legislature, most of these legislators joined the Legislature's Finance Committee, which had authority over banking policies. When new banks applied for licenses in the late 1980s, nine legislators were

46 Central Bank, Zhonghua Mingguo Zhongyang Yinhang Zhi Zhidu Yu Gongnen [Institutions and

Functions of the ROC Central Bank] (Taipei: Central Bank, 1991), pp.152-65.

47 Shangmao Chen, Taiwan Yinhang Zhengce De Zengzhi Jinji Fenxi, p.151. 48

The only exception during this period was the 1975 banking reform, whose purpose was to overhaul the 30-year-old banking law.

shareholders of ten different banks. During the administration's evaluation process, these legislators frequently voiced their concerns and made specific proposals to protect the interests of those conglomerates that owned these banks. What did these legislators get in return? They purchased the unlisted stocks of the banks at about US$3 a share. Once the new banks were established and listed their stocks, their stock prices immediately doubled or tripled.50

In 1992, when the Taiwanese elected all legislators, the number of legislators with banking background increased: twenty-seven had formal relationships with banks or credit unions. Among the twenty-seven legislators, twenty were shareholders of the new banks; sixteen were directors or supervisors of banks, credit unions, or other financial institutions. After the 1995 election, fifteen legislators were directors or supervisors of financial institutions. The 1998 election brought in twenty-one legislators with banking interests.51

Finally, the role of foreign banks in Taiwan's banking industry has been limited. Since the banking liberalization of the 1980s, foreign banks have established more subsidiaries in Taiwan and their banking activities have increased as well.52 However, the Taiwanese government has maintained some critical constraints on foreign banks and prevented foreign banks from taking a larger share of Taiwan's banking market. The major constraints are a high capitalization requirement, high reserve ratio, and limited scope of banking activities. For instance, not until 1994 did the government lift the regulation that foreign banks could not accept Taiwan dollar deposits and had to wait for two years before establishing each additional branch. Before 1994, foreign banks could establish branches only in Taipei and Kaohsiung, not in other cities or in the countryside. Only three new branches were allowed annually for all foreign banks. Currently, there remain restrictions on the amount of Taiwan dollar deposits, foreign employees, the capitalization of bank branches, the establishment of bank subsidiaries, and other banking affairs.53

49 Shangmao Chen, Taiwan Yinhang Zhengce De Zengzhi Jinji Fenxi, p.149.

50 Junyi Li, Choulou De Lifayuan [The Ugly Legislature] (Taipei: Formosa., 1995), p.158. 51

Tiancai Kang, and Jinchuan Zheng, “Liwei Jinquan Guanxi Quanmian Jiepou” [An Analysis of the Relationships Between Legislators and Business], Shangye Zhoukan, no.587 (1999), pp.32-48.

52 For the history of Taiwan's banking liberalization, see Junbao Yen, Taiwan Diqu Yinhang Fazhan

Sishinian [The Forty Years of Development of Taiwan's Banks] (Taipei: Zhonghua Zhenxinsuo,1991).

53

Wei Ding, "Taiwan Jinron Huanjing Bianqian Dui Waishang Yinhang De Chongji Yu Yingxiang" [The Shock and Impact of the Transformation of Taiwan Financial Environment on Foreign Banks] ( MA. Thesis, National Taiwan University, 1995); and Ministry of Finance, Changyong Jinron Fague Huibian [Collection of Financial Regulations Frequently Used] (Taipei: Bureau of Monetary Affairs,

In fact, in terms of percentage, the influence of foreign banks has increased little since the 1980s. The number of local branches of foreign banks increased from twenty-one in 1980 to forty-three in 1990 and to sixty-nine in 1997. But the ratio of foreign bank subsidiaries to domestic bank subsidiaries increased little, from 4% in 1980 to 6% in 1990, and declined to 4% in 1997. The amount of loans provided by foreign banks subsidiaries increased from US$2.7 billion in 1980 to US$6.1 billion in 1990 to US$12.6 billion in 1997. But during the same period of time, Taiwan's credit unions, farmers' and fishermen's associations, and medium business banks each had exceeded foreign bank subsidiaries not only in terms of the amount of loans but also in terms of the growth rates of such loans. Hence, the percentage taken by foreign bank loans of the total of all such loans declined from 32% in 1980 to 13% in 1990 to 12% in 1997.54 Indeed, there has been banking liberalization, but foreign banks have not been able to improve their small market shares in Taiwan due to the local oligopolistic alliances.

Thus, the 1997-1998 banking crisis in Taiwan was caused less by external factors than by the oligopolistic alliance among the KMT, local factions, conglomerates, and representatives, with the administration as a tacit collaborator. The KMT controlled four banks to expand its financial and political influence. Conglomerates established new banks to subsidize their subsidiaries and to consolidate political connections. Local factions survived on the oligopolistic rents of local credit institutions in order to finance campaign expenses. Therefore, a symbiosis of the KMT, representatives, local factions, and conglomerates existed. The financial administration, with declining political autonomy since democratization began in the 1980s, could not but collaborate with this financial oligopoly.

The Stock Market

Taiwan's economists have described Taiwan's stock market as a bubble economy. They explain the distortions of Taiwan's stock market in terms of information asymmetry and irrational expectations. Most of Taiwan's stock buyers are individuals. They tend to follow the signals of a few volume investors or television stock advisers. When stock prices far exceed their normal levels (e.g., the price/dividend ratio is higher than 20:1), individuals investors continue to buy stocks, Ministry of Finance, 1998).

even borrowing money to do so, until the bubble bursts. Then, they sell their stocks in panic even when prices are far below their normal levels.55

Taiwan's economists are correct in their description and explanation of the weaknesses of Taiwan's stock market. But the fundamental problem with the distorted market structure was the oligopolistic alliance among the KMT, the conglomerates, and representatives. Together, they exerted political influence on the operation of Taiwan's stock institutions, such as the monitoring institution of the Taiwan Stock Exchange Corporation, the monitoring and enforcement institutions of the Securities and Futures Commission, the macroeconomic policies of the Central Bank, and the security policies of the Finance Ministry.56

First, conglomerates dominated the stock market. In August 1988, the government liberalized the stock market and permitted the establishment of new stock companies. In the next two years, 349 new stock companies were established. Almost each of the top 100 conglomerates owned a stock company. For conglomerates, there were four layers of profits associated with owning a stock company. One was the lucrative profit of stock transactions. The other was the reduction of management fees for stock transactions. The third one was the profit gained from manipulating the prices of the conglomerate's stocks. And finally, the conglomerate could explore other investment markets through the stock company.57

In order to maximize each layer of the above profits, conglomerates built up political connections. These conglomerates needed to know in advance whether an important policy that would affect stock prices might pass or be defeated in the Legislature, so that they could buy and sell stocks before the market reacted. They needed to know whether the Ministry of Finance proposed the increase or reduction of taxes on stock transactions. When a conglomerate engaged in illegal stock transaction, it needed political guardians to interfere with the investigation by government authorities. And finally, many conglomerates competed for government procurement projects. A successful bid would raise the prices of the conglomerate's stock prices.

54 Taiwan Statistical Data Book 1998, pp.149, 163. 55

Zongxian Yu, and Jinli Wang, Taiwan Paomo Jingji [Taiwan's Bubble Economy] (Taipei: Zhongkuo Jingji Qiye Yanjiusuo, 1998).

56 For more detailed analysis of the operation of these stock institutions, see Zonghao Huang, Taiwan

Gupiao Shichang Zhi Zhengzhi Jingji Fenxi (A Political Economic Analysis of Taiwan's Security Market). Master thesis, National Chengchi University, 2000.

57 Shengyuan Zang, Cong Jinqian Youxi Yu Jinrong Jieyan Kan Taiwan Jinquan Zhengzhi Zhi

Xingcheng [A Look at the Formation of Money Politics from the Perspectives of Money Game and Financial Liberalization] (MA. Thesis, National Taiwan University, 1993).

All of the above information and profit opportunities could be obtained by supporting particular legislators or by sending their own conglomerate members to the Legislature, especially to the Legislature's Finance Committee and Economic Committee. Thus, I have found legislators actively interfering with the normal transaction of Taiwan's stock market, as described below.

Secondly, representatives interfered with market transactions. Zhenhuan Wang58 has found that among the 294 legislators elected between 1969 and 1992, half of them simultaneously held enterprise positions as presidents, vice presidents, CEOs, deputy CEOs, directors, supervisors, or consultants. In the 1980s and early 1990s, at least ten legislators (and/or their spouses), including the speaker and the vice speaker, owned or invested significantly in stock companies.59 The number of such legislators increased to fifteen after the 1998 election.60 These legislators have had high reelection rates and have been regular members of the Finance Committee, which makes policies regulating stock transactions.

Two incidents exemplify the legislature's interference with market transactions. One concerned the taxes imposed on the transaction of stocks and on stock companies. For tax fairness purposes, from 1988 to 1993, the Finance Ministry tried several times to raise the tax on stock transactions to 1.5%. But the Legislature not only defeated these proposals; on the contrary, it continued to lower the taxes to 0.3%. During the same period of time, the Ministry tried frequently to impose taxes on stock companies; all attempts failed.61

The other incident was the Hongfu Stock Company scandal in 1994. The company engaged in large-scale illegal stock transactions, with many legislators involved. The owner was also a legislator. When the Investigation Bureau searched the owner's house, at least eighteen legislators showed up to successfully interfere with the investigation. The investigation ended up with prosecutions of some minor managers. Other legislators involved in the scandal have continued to serve as legislators. The owner of the stock company was set free and became involved in a few scandals from time to time afterwards.62

Thirdly, the KMT became a major player in the stock market. In 1987, the

58 Zhenhuan Wang, Shui Tongzhi Taiwan [Who Governs Taiwan?] (Taipei: Juliu, 1996), p.149. 59 Junyi Li, Choulou De Lifayuan, pp.76-80.

60 Qinru Li, "Xiajie Liwei Caifu Shili Dapuguang" [Exposure of the Financial Power of the Next

Legislature], Xinxinwen, no.19 (1999), pp.51-59.

Taiwanese government lifted martial law. The opposition party was able to monitor the connection between the state's coffers and the KMT's. In response, the KMT reorganized its enterprises to find alternative sources of financing. Former Minister of Finance, Lide Xu, took up the mission as the newly appointed chairman of the Finance Committee of the KMT in August 1988. From 1988 to 1993, Xu successfully introduced a modern management system to KMT party enterprises in order to raise their competitiveness. Furthermore, Xu began to expand joint ventures among KMT enterprises as well as between KMT enterprises and private conglomerates. Stocks became critical instruments for such joint ventures.

In June 1993, the KMT established a new investment coordination committee, the Business Management Committee (BMC), as described in the previous section. The BMC enabled the KMT to institutionalize consultation with conglomerates with regard to joint ventures and political matters. In 1993, the Committee consisted of six KMT enterprise presidents, one scholar, and eight presidents or CEOs of private conglomerates. In 1996, two more conglomerate representatives were added. All ten private conglomerates derived their revenues mainly from protected domestic markets, such as real estate, construction, banks, and stock companies, which made political connections critical to their profits.63 Major producers of export-oriented electronic products were absent from the Committee. The Committee met once a month to respond quickly to market changes.

Through the seven holding companies and their joint ventures, the KMT was able to influence stock prices. In 1995, these seven holding companies controlled and managed three stock companies: Dahua, Fuhua, and Huaxin64. Two more stock companies, Zhonghua and Fanya, were added later to the KMT roster.65 If conglomerates had an advantage in manipulating stock information as described before, the KMT certainly ranked above all other conglomerates in information manipulation. For instance, Fuhua Stock Company was the largest stock company in Taiwan in 1999. In terms of net profit before tax, it ranked seventeenth among

62 Junyi Li, Choulou De Lifayuan, pp.80-82.

63 Shuzhen Tan, "Guomingdang Dangguanhui De Bimi Zhiyi" [One of the Secrets of the KMT

Business and Management Committee], Xinxinwen, no.480 (1996), pp. 90-93.

64

Yonghuang Liang, "121 Jia Dangzi Shiye Zonglan" [An Overview of the 121 Party Enterprises], Wealth Magazine ( April, 1995), pp. 102-108.

65 Huijuan Huang, "Yibaida Qiye Jituan Diaocha" [An Investigation of the Largest 100 Enterprises],

Taiwan's 150 financial institutions.66 In fact, in all the past stock crashes, KMT enterprises never suffered as severely as other conglomerates did. On the contrary, KMT enterprises usually made handsome profits during economic recessions, although less than during economic recoveries. The difference between conglomerates and the KMT was that as the ruling party, the KMT controlled the decisionmaking and policy implementation process of major economic policies that might affect stock prices.

Fourthly, the state could not but be a passive and active collaborator in stock market distortions. On the passive side, the state agencies, which might affect stock market transactions, did not have effective supervisory power. The Central Bank lost its political autonomy as described in the last section. The Securities and Futures Commission of the Finance Ministry, which was in charge of regulating stock market transactions, had not been an effective monitoring authority for three reasons. It had a small budget. Its staff members were few; the organization's bylaws authorized 242 staff members to deal with more than 400 foreign and domestic stock and investment companies.67 And its legal and political status in the bureaucracy was low; it was not an independent commission, nor did it have the rank of a department, as its counterparts in the United States and Germany do.

On the active side, the state formulated policies to stimulate stock prices before all presidential and legislative elections. These policies included the reduction of stock transaction taxes, the increased entry of government funds (pension funds, postal savings, social security funds, etc.) to the stock market, the lowering of administrative barriers against foreign capital, the Central Bank's loosening of the money supply, and the relaxation of other stock market regulations. The purpose was to create an image of the KMT's strong governing capability. It also served the KMT enterprises to make extra profits for campaign expenses. Once the elections were over, stock prices usually tumbled.68

Finally, foreign investors have not been major players in Taiwan's stock market. It is undeniable that the number of foreign investors and the amount of foreign capital in Taiwan's stock market have increased rapidly in the past ten years. Taiwan's

66

Shangye Zhoukan, no.603 (1999), pp.76-131.

67

<http://www.sfc.gov.tw>.

68 Mengxia Li, "Jieyenho Xuanju Yu Zhence Guanxi Zhi Jiantao" [A Study of the Relationships

between Elections and Economic Policies in the Post-Martial Law Period] (MA. Thesis, National Chengong University, 1997), pp.60-63.