THE POLITICS OF REREGULATION: GLOBALIZATION,

DEMOCRATIZATION, AND THE TAIWANESE

LABOR MOVEMENT

CHANG-LING HUANG

Since the early 1990s, Taiwanese workers have faced two simultaneous trends: democ-ratization and globalization. These two trends have different, if not exactly opposite, implications for the labor movement. Democratization has empowered the working class and made its members more effective in the political process. Globalization, however, has led to an increase in the flexibility of the labor market and made workers more vulnerable to changes in the economic environment. This paper begins with a discussion of the general characteristics of Taiwan’s labor movement and the general impact of globalization on labor institutions. Then, by examining the transformation of Taiwan’s labor institutions in recent years, and specifically the process of union reorganization and the revisions of the Labor Standards Law, the paper shows how, against the back-ground of globalization, Taiwanese workers have used their newly acquired political power to maneuver between different political forces and set the development course for the labor movement.

I. INTRODUCTION

T

HE March 2000 presidential election resulted in the Kuomintang (KMT), the party that ruled Taiwan for more than half a century, turning power over to the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP). Although the KMT lost the elec-tion, it still controlled the majority in the Legislative Yuan, the highest legislative body in Taiwan’s political system. This situation has created a series of power struggles between the executive and legislative branches and has led to numerous debates over Taiwan’s constitutional framework.A bill to revise the Labor Standards Law was the first main battleground between the ruling and opposition parties. Not long after its inauguration, the new govern-ment presented a bill to the Legislative Yuan seeking to reduce the legal limit of work hours from the current forty-eight hours per week to forty-four. To show that

––––––––––––––––––––––––––

An earlier Chinese version of this paper was presented at the Conference on Civil Society, Social Movement, and Democratization on Both Sides of the Taiwan Strait, Boston University, Cambridge, Mass., April 24–25, 2001.

the party still had the power to control national policies in spite of having lost the presidential election, the KMT members revised the bill in the Legislative Yuan and further reduced the legal limit to eighty-four hours every two weeks. Within the next six months, the new government—to the surprise and with the opposition of many labor activists—made three attempts to reverse the bill back to forty-four hours a week. Those in labor movement circles, including the unions and labor organizations that were close to the DPP, formed the “Coalition for 84 Work Hours” to oppose the government’s attempts. The issue was eventually settled at the end of December, when a law was enacted mandating eighty-four work hours every two weeks, with the new regulations to be put into practice in 2001.

Because of the change in government, the work-hour-reduction bill attracted much media attention. The media focused on the political struggles between the govern-ment and the opposition in passing the bill. For the Taiwanese workers, however, the struggles began long before the turnover of the ruling party. Taiwanese workers since the early 1990s have faced two simultaneous trends: democratization and globalization.1 These two trends have different, if not exactly opposite, implica-tions for the labor movement. Democratization empowered the working class and made it more effective in the political process. Globalization, however, increased the flexibility of the labor market and made workers more vulnerable in the eco-nomic environment. In the following sections, I will first discuss the general char-acteristics of Taiwan’s labor movement and the general impact of globalization on labor institutions. And, then, by examining the transformation of Taiwan’s labor institutions in recent years, especially the process of union reorganization and the revisions of the Labor Standards Law, I will demonstrate how, against the back-ground of globalization, Taiwanese workers have used their newly acquired politi-cal power to maneuver between different politipoliti-cal forces and set the development course for Taiwan’s labor movement.

II. DEMOCRATIZATION AND THE TAIWANESE LABOR MOVEMENT

By conventional standards, the Taiwanese labor movement is weak. In terms of both organizational strength and mobilizational capacity, the movement is nowhere 1Scholars give different definitions for a completed democratization process. For example, Mainwaring, O’Donnell, and Valenzuela (1992) divide the democratization process into two stages. The first stage is from the breakdown of the authoritarian regime to the establishment of a popu-larly elected government, followed by a second stage to the establishment of a democratic regime. Linz and Stepan’s (1996) concep of democratization is similarly defined. Others, like Huntington (1991), argue that whether or not the ruling authoritarian government leaves office is an important criterion. Huntington holds that two political turnovers must have taken place for democracy to be consolidated. Przeworski and Limongi (1997) argue that democracy prevails only when the au-thoritarian party experiences the loss of either the highest executive office or control of the legisla-tive organ of the government. According to Przeworski and Limongi’s definition, Taiwan did not become a democracy until after the March 2000 presidential election.

to be compared to its counterpart in many developing countries. Many have attrib-uted the acquiescence of Taiwanese workers to either the highly decentralized in-dustrial structure (Koo 1989; Shin 1994, pp. 247–83) or the long-term political control of the authoritarian KMT government (Hsu 1987; Choi 1989). It is argued that the predominance of the small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in the economy makes collective action difficult, and that the state repression makes col-lective action impossible. These two popular arguments have obvious limits when we consider empirical evidence. Northern Italy, similarly dominated by SMEs, has been one of the most strike-prone regions in the world. The Republic of Korea, which has similarly repressed its working class under long-term authoritarian rule, has one of the most militant working classes in the world. The acquiescence of the Taiwanese working class is actually a result of the interplay between a neo-mercan-tilist industrial policy and Taiwan’s postwar politics (Huang 2000).

The relationship between democratization and the Taiwanese labor movement is quite straightforward: democratization brought about the labor movement, not the other way around. Though the workers did not play a significant role in bringing about democratization, they exerted an unprecedented level of labor militancy after the onset of democratization in 1987, when the government lifted the four-decade martial law. Between 1987 and 1989, the Taiwanese state and employers were en-gaged in a process of adjustment after being confronted with successive waves of strikes.

At the beginning, the KMT’s Central Standing Committee passed a resolution in August 1987 to revise the Labor Dispute Adjustment Law and to encourage the enterprises to adopt a formal bonus system (Pang 1990, p. 28). The government also established the Council of Labor Affairs, a ministry-level agency in charge of labor issues.2 The establishment of the council led the government to direct more administrative resources to solving or preventing labor disputes. One of the very first steps the council took was to design a detailed questionnaire for each local government’s Bureau of Labor Affairs to fill out whenever important labor disputes arose within its jurisdiction.3 The government also dispatched delegates and pro-government union cadres overseas to study how other countries resolved labor dis-putes.

Capitalists, facing increasing demand from the working class and the transfor-mation of the state’s role in democratization, responded in three ways. First, after 2Chao (1991, p. 86) points out how confused the state was during the reorientation process: the government changed its decision three times within six months about which administrative levels should be expanded in the administration of labor affairs.

3The council did not specify what should be considered as “important labor disputes,” according to one chief of the Bureau of Labor Affairs, but generally the local government would report disputes that fit to one of the following conditions: (1) the number of involved workers exceeded a certain threshold such as fifty or one hundred, (2) there were “outside forces” involved such as social movement activists or local politicians, and (3) there were physical confrontations.

initial reluctance, some businessmen, especially employers in the upstream, capi-tal-intensive industries accepted workers’ demands to be a party in routine negotia-tions. This was the case in the petrochemical industry after bonus struggles in 1988 and 1989.4 Second, many employers began to hire private security personnel to prevent labor movement activists from entering the plants and to confront workers whenever necessary.5 Third, some capitalists threatened to have a capital strike. As Block (1977) argues, capitalists, as a ruling class under capitalism, did not have to rule, they could withhold investment. At a symposium held in January 1989, eight leading capitalists openly expressed their dissatisfaction with the government’s in-action toward what they called social disorder, namely, the environmental and labor movements (Jingji ribao, January 4, 1989). The most threatening move came from Wang Yong-Qing, founder and owner of the Formosa Plastic Group, Taiwan’s larg-est business group. In February he announced that the group would temporarily suspend all investment plans in Taiwan, and that a planned oil refinery, for which the government had fended off pressure from the environmental movement, would probably be constructed in mainland China instead.

Wang’s announcement, as well as similar threats from other capitalists, com-pelled the government to show the business community its determination in main-taining production order. One month after Wang announced his capital strike, the government, at the risk of international and domestic criticism, expelled an Irish Priest, Neil Magill, for his involvement in the labor movement.6 The pressure on the labor movement was also exacerbated by divisions within the movement. The Workers’ Party, established in November 1987, split over ideological differences after one year. The socialist-oriented faction left the party to establish the Labor Party in December 1988. The cleavage proved to be costly to the nascent labor movement: in the December 1989 election, the chairman of the Workers’ Party lost his seat in the Legislative Yuan.7

The Taiwanese state and capitalists completed their readjustment toward the working class no later than in the spring of 1990, when the newly appointed pre-mier had a military background. The prepre-mier announced that the government not only would improve the investment environment, but would also no longer tolerate any “social movement troublemakers” who disturbed the social order. By 1990, however, the nascent labor movement also found its place in both local as well as national politics. The current three major activist organizations in the labor move-4The eighteen firms in Kaohsiung County’s Lin Yuan Petrochemical Industrial District all devel-oped collective bargaining routines with their unions. The items for bargaining, however, at least up until 1994, were strictly limited to wage-related issues.

5Many union cadres and activists mentioned in interviews that companies began to hire private security forces in 1988.

6Before coming to Taiwan, Father Magill had lived in Korea and was active in the labor movement there.

ment were all established between 1987 and 1989.8 The Taiwan Labor Front, reor-ganized from the Taiwan Legal Aid for Labor, was established in 1987 and has enjoyed a close relation with the DPP. The Coalition of Independent Unions was established in 1988 and cooperated with the DPP county magistrate in the Taipei County in the early 1990s and later the KMT mayor in Taipei City in the late 1990s.9 The Association of Labor Rights was established in 1989 and has had a close rela-tion with the pro-socialist Labor Party.

The strikes that occurred in a wave between 1987 and 1989 were short-lived, mainly because the organizational strength of the labor movement was limited. While union cadres and labor activists worked hard to build the organizational strength of the working class, they also took advantage of any opportunity that would allow them to penetrate the political establishment. The political establish-ment, on the other hand, also intended to incorporate the labor movement. The most telling evidence came in January 1999, when newly elected mayors in both Taipei City and Kaohsiung City, the two largest cities in Taiwan, appointed labor movement leaders to head the Bureau of Labor Affairs in their governments. Given that these two cities are under the rule of different political parties, in Taipei the KMT and in Kaohsiung the DPP, the two mayors’ decisions showed that, twelve years after democratization began, the political establishment in Taiwan was taking initiatives to accommodate labor movement demands.

III. GLOBALIZATION AND LABOR INSTITUTIONS

Current understanding of the impacts of globalization on the labor institutions draws heavily from the French regulation school, or its American equivalent, the theories of the social structural accumulation or flexible specialization (Piore and Sable 1984; Lash and Urry 1987; Kotz, McDonough, and Reich 1994).10 The basic logic of these different, but rather similar and much overlapping, theories is this: different stages of the development of capitalism are shaped by different regimes of accumu-lation. Each of these regimes is supported by a specific mode of reguaccumu-lation.

8Because the KMT government had repressed union activities for a long time, Taiwan’s labor move-ment before and in the early period of democratization was largely led by the activist organizations. These organizations usually consisted of intellectuals who supported labor rights and individual workers who had a strong labor consciousness. With limited resources, these organizations focused more on policy advocacy than union organization. By the mid-1990s, when Taiwan’s democracy became more consolidated, labor unions also became more active in the labor movement as well as in politics. The increasing strength of the labor unions, however, did not reduce the importance of the activist organizations. These organizations have remained active in Taiwan’s labor movement, fighting for the labor rights together with labor unions.

9Founders of the Coalition of Independent Unions later established the Workers Action for Law Enactment. Therefore, to put it more accurately, the cooperative relation is actually between the Workers Action for Law Enactment with the Taipei City and Taipei County governments. 10For the difference among these theories, see Hirst and Zeitlin (1991) and Kotz (1994).

The world economy since the 1930s and throughout much of the postwar era was dominated by a Fordist accumulation regime based on mass production, using un-skilled labor and producing standardized products. Thus, the two major economic regulations in the advanced industrial democracies have been the Keynesian eco-nomic policy that ensures demand for labor and the welfare policy that ensures demand for goods. Fierce competition in the world market, however, gradually gave producers incentives to differentiate their products and fragmentize their produc-tion process. Such changes made the producproduc-tion process more flexible and required a new mode of regulation. Therefore, the change of regulation is about reregulation, not deregulation, as is sometimes claimed or portrayed by liberal economists.11

If flexibility is the core issue of economic restructuring, then supposedly the predominance of SMEs in Taiwan’s economy leaves little room for the economy to be restructured. The highly developed network of subcontracting systems, espe-cially in the labor-intensive industries, made both employment and production ex-tremely flexible even before globalization became a popular topic for discussion (Shieh 1989). However, Taiwanese workers are still affected by globalization be-cause it increases the flexibility of the labor market at the global level and changes the bargaining position between the firms in the advanced countries and the devel-oping countries.

One of the major issues Taiwanese workers have faced since the late 1980s has been plant closure. This phenomenon has hit workers hard in the labor-intensive industries, because firms in this sector tended to be more sensitive about labor cost. However, seeking cheap labor was not the only reason why Taiwanese firms moved overseas. Many firms did so because of the encouragement or the request of their buyers.12 In the old days, a producer in developing countries like Taiwan simply produced consumer goods and sold them to trading companies in advanced coun-tries. These trading companies then sold the goods to retailers.

Since the 1980s, with improved transportation and communication technologies, retailers in advanced countries began to bypass the trading companies and started developing their own labels. Brand name companies in the meantime also began to outsource their production and focus on marketing and distribution. Under such 11Part of the reason why reregulation is depicted as deregulation is because this logic has been used to explain the recent trend toward the decentralization of collective bargaining and welfare reform in the advanced industrial democracies. This is most clear in Sweden’s case. Ulf Laurin, chairman of the Swedish Employers’ Association (SAF), made a major policy statement on February 16, 1990 concerning the future of collective bargaining. He said: “After a long-term-illness, the Swed-ish model is dead. . . . The course for our wage policy is totally clear. It is focused upon decentrali-zation—with the intent of providing a dominant role for firm level bargaining” (Pestoff 1995, p. 157).

12One example is the investment decision of Pao Cheng Enterprise, Taiwan’s leading footwear manu-facturer and a major contractor of brand name footwear companies. Under the suggestion of Nike, Pao Cheng made investment in Vietnam instead of completely focusing on mainland China (“Quan fangwei” 2000, p. 61).

circumstances, many developing country producers gradually became subcontrac-tors for retailers or brand name companies in the advanced countries. Such change has weakened the bargaining position of the former, since retailers and brand name companies control market access and can shop around the world to minimize costs.13 In other words, firm strategies for Taiwanese producers are considerably affected by the firms’ position in the international division of labor since most of these pro-ducers are well integrated into world production networks.

Taiwanese firms’ moving overseas undoubtedly exerted a considerable impact on Taiwan’s labor market. The unemployment rate since the early 1990s has steadily increased from around 2 per cent to the current 5 per cent,14 and plant closure or business reduction since the late 1990s has been the major reason for unemploy-ment (DGBAS 2001b). The structural transformation is also revealed by the reason why workers chose part-time jobs. According to the government census data, 15.7 per cent of the part-time workers chose part-time jobs because they could not find full-time jobs. Among the unemployed workers, those who used to work as indus-trial labor showed the highest unemployment rate (DGBAS 2001a).

For workers, the changes in the bargaining position of the local firms implies that major actors in the globalization process are beyond their reach. Though workers cannot turn the tide of globalization and prevent the firms from moving overseas, the political horizon widened by democratization, however, provides them with opportunities to make the state more responsive to their needs. As we will see in greater detail in the discussion below, union cadres and labor activists are quite skillful in linking labor politics with electoral politics. This ability allows them to achieve greater policy influence than what is permitted by the limited organiza-tional strength of the working class.

IV. REREGULATING THE LABOR INSTITUTIONS

Two cases of reregulation of labor institutions will be discussed in this section: the changes in the union organization and the revision of the Labor Standards Law. The changes in the union organization have a direct impact on the development of the labor movement because they indicate how workers’ interests are articulated and represented. The revision of the Labor Standards Law has a direct impact on the labor market because it changes the labor conditions. For union reorganization, union cadres and labor activists cooperated with the DPP. In the revision of the 13During an interview, one owner of a footwear plant told me that the power shift was quite clear in terms of price setting. Producers had much more power in setting the price before they became the subcontractors of big retailers or brand name companies.

14According to the most recent government statistics, the unemployment rate in September 2001 was 5.26 per cent. This figure was announced on October 23, 2001 at the website of the Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics: http://www.dgbasey.gov.tw/census~n/four/n9.htm.

Labor Standards Law, union cadres and labor activists cooperated with different political parties at different times.

A. Changes in Union Organization

The experiences of advanced industrial democracies reveal that the pattern and configuration of a country’s labor movement are highly correlated with its union organization, which is a result of the historical process (Zolberg 1986, pp. 397– 456; Fulcher 1988; Joseph 1992). Union organization, especially the degree and nature of its fragmentation, is also closely related to its response to economic re-structuring and employers’ strategy of reorganizing work (Golden and Pontusson 1992). As Pontusson (1992, p. 12) has pointed out, union organizational structures seem to have a direct bearing on whether workers rely on collective bargaining as a show of marketplace power, or pursue their interests by legislative means, that is, through the exercise of political power.

In the same way as in the advanced industrial democracies, union organization has been a major means for organized workers in Taiwan to fight for their class interests. Organized workers have tried to make the organizational structure of their unions correspond to the differentiated interests within the working class. As will be discussed in the following paragraphs, during the reorganization process, orga-nized workers successfully used a seemingly unimportant arena, namely, the local politics, to achieve their goal of establishing a new national federation of unions.

Before discussing reregulation process, I shall clarify some features in the evolu-tion of union organizaevolu-tion in Taiwan. First, it has been claimed that labor control in Taiwan is based on state corporatism (Hsu 1987), and I have argued against this claim elsewhere (Huang 1997). It is true that labor representation is monopolized in Taiwan, and the union structure has a corporatist outlook. However, state-spon-sored union federations in Taiwan do not have any control over their member unions. They have neither the ability to articulate working class interests, nor the means to discipline their supposed member unions. Most importantly, wage and employ-ment are not regulated by any corporatist arrangeemploy-ment.

Second, before democratization, Taiwan did not experience much change in the development of union organization. Since the early 1950s, unions have been orga-nized along two lines. For workers who work for the same employer and at the same workplace, unions are organized at the enterprise level (industrial unions).15 For workers who belong to the same occupation but do not have the same employ-ers or the same workplace, unions are organized based on occupational categories (occupational unions). Both kinds belong to regional union federations, and the 15To be more precise, these unions are organized at the plant level instead of enterprise. That is, if an enterprise has multiple plants, then each plant will have its own union, and the unions are not allowed to merge into one. These unions have to register as different unions, and, if the plants are located in different jurisdictions, they will belong to different regional union federations.

regional union federations in turn are members of the national confederation, the Chinese Federation of Labor (CFL).

Third, organizational strength of Taiwanese workers cannot be evaluated by the unionization rate, especially when it is compared with other countries. For example, it is generally recognized that Korean workers are better organized, but Taiwan’s unionization rate, especially in recent years, has been consistently higher than that of Korea (Table I). The reason is that the Taiwanese government since the early 1980s has significantly relaxed the process of licensing newly established occupa-tional unions. This policy allows easy access to government subsidized labor health insurance. Before the national health insurance was launched in 1995, since the government did not specifically require occupational unions to verify their mem-bers’ working status, many people, working or not, joined an occupational union to acquire health insurance. Thus, the high unionization rate is misleading, and is not a good indicator of the organizational strength of Taiwanese labor.

The objective of Taiwanese workers in union reform is to separate the represen-tation of industrial unions from that of the occupational unions in the regional and national federations, so that each can capture the administrative resources the state puts aside for the federations. There are two reasons for this objective. The first is that since different interests of different types of unions can be articulated, the workers understand that they have a clear stake in the reform. The second reason is related to the nature of labor disputes, the mediation process of these disputes, and their implication for the development of the labor movement.

The interests of the Taiwanese industrial workers are different from those of the occupational unions. As mentioned above, many members of the occupational unions

TABLE I

UNIONIZATION RATEIN KOREAAND TAIWAN

Year Korea Taiwan

1966 21.2 16.7 1971 19.7 16.9 1975 23.0 20.0 1980 20.1 24.5 1985 15.7 29.5 1990 21.7a 43.3

Sources: For Korea, Shin (1994, p. 303); for Korea 1990, KLI (1992); for Taiwan, calculated based on Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics, Yearbook of Labor Statistics of the Republic of China, 1971 and 1991 editions.

aUnionization rate is calculated by dividing the number of union members by the number of people employed in non-farm business.

in Taiwan joined the unions in order to obtain health insurance. Among these so-called occupational workers, many were self-employed professionals or entrepre-neurs of SMEs. Since members of the occupational unions are generally indiffer-ent, if not opposed, to the interest of the working class, this system is not beneficial to the labor movement.

Even more frustrating for industrial workers is that, at the regional and national federation levels, elected union officials usually belong to the occupational unions. This is so not only because the number of occupational unions usually far exceeds that of the industrial unions, but also because the leaders of the occupational unions tend to be members of or have close ties with the KMT. The unorganized nature of the occupational unions also leads industrial union leaders to consider that the oc-cupational unions actually have fewer members and should not be entitled to dis-proportionately more resources as under the current system.

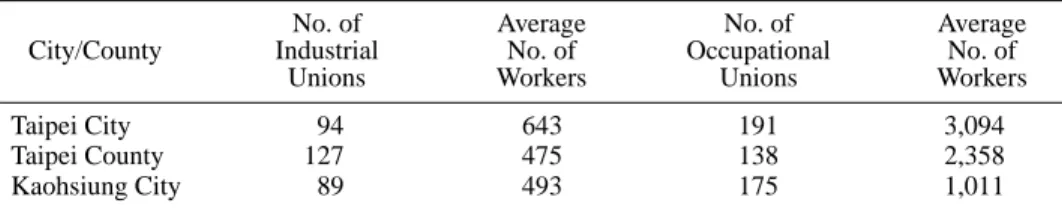

Within the labor movement circles, there have been discussions about changing the election rule from the current one union–one vote to proportional representa-tion based on membership size (Chen 1993). Some activists consider that this will allow industrial unions to win the union federation election. But this assumption is wrong. Among the twenty-three counties and cities at which level a regional union federation is formed, the average occupational union has more members than the average industrial union. As shown in Table II, it is clear that even for the three largest industrial cities/counties, the number of occupational unions not only ex-ceeds that of the industrial unions, but membership in the former is larger than in the latter. In other words, the industrial unions would be in the minority under either election scheme, and thus would not gain electoral victory by merely fighting for a new system of union election.

The second reason for the union organization reform is interwoven with the rela-tionship among politics, labor disputes, and the development of the labor move-ment. Though the central government wields much power, Taiwan has had a long history of relative local autonomy even before democratization. When the ruling KMT government moved from mainland China to Taiwan in 1949, the party

se-TABLE II

NUMBERSAND AVERAGE MEMBERSHIP SIZEOF OCCUPATIONAL UNIONSAND INDUSTRIAL UNIONSIN THREE CITIES/COUNTIESIN TAIWANIN 1992

Taipei City 94 643 191 3,094

Taipei County 127 475 138 2,358

Kaohsiung City 89 493 175 1,011

Sources: Calculated from the Council of Labor Affairs (1993, pp. 8–9). City/County Average No. of Workers No. of Occupational Unions No. of Industrial Unions Average No. of Workers

cured its rule through a comprehensive patronage system. The KMT granted local elites regionally monopolized economic privileges in exchange for their political loyalty, and made local elections the arena for local resource competition (Wu 1987; Chen and Chu 1992). Therefore, despite the authoritarian rule in Taiwan that lasted until 1987, local politicians in Taiwan have been accustomed to providing services and responding to their constituencies (Chao and Kau 1993).

The Labor Dispute Mediation Law requires that labor disputes be mediated in the jurisdiction where they occur. Thus the county and city bureaucrats in charge of labor affairs are used to play a pivotal role in solving disputes. Since democratiza-tion, an increasing number of workers have been asking help from their local elected politicians when they are in dispute with their employers. County and city bureau-crats find that dealing with the involvement of these politicians is annoying but unavoidable, since they can pressure the county/city government from the council. Because politicians can side with either the employers or the workers, “the most annoying thing,” according to a county official, is “when both sides bring politi-cians into the process” (Huang 1993).16

The increasing trend of investment of local politicians in the mediation process brings a challenge to the labor movement. The easier it is for individual workers to solve disputes by eliciting help from politicians, the less likely they are to collec-tively solve problems or link their personal grievances with those of other workers. Moreover, politicians tend to refer the disputes to activist organizations. Activists and union leaders realize that focusing their limited resources on individual dis-putes is costly and not in the interests of the whole working class, unless this ser-vice can be provided en masse to a large number of workers. But most of these disputes involve only a small number of workers. In other words, the activists are put in such a position that they cannot refuse to help troubled workers, but they also cannot afford to waste their resources on disputes that will not have a cumulative effect on the labor movement.

Under such circumstances, labor activists felt an urgent need to increase resources for the labor movement. One way to achieve this objective is to capture the admin-istrative resources the government set aside for union organization because all the union federations at the county/city level receive subsidies from the county/city government and sometimes the central government.17 The activists’ rationale is this: if they can help the industrial unions that are more autonomous and independent to win the union federation elections, then cadres of these industrial unions, as leaders 16Local politicians themselves do not attend the mediation meetings, unless the disputes involve a large number of workers or locally powerful companies. They usually send one of their aides to attend the mediation meetings.

17The Tainan County Federation of Unions is a good example. In 1992, only 45 per cent of the union’s budget was derived from member union dues. Approximately 31 per cent of the budget consisted of subsidies from either the county government or the central government (Tainan County Federation of Unions, Annual Report, 1991, 1991, pp. 56–57).

of the union federations, can have the resources and capacities to play a more active role in resolving the labor disputes that take place within their counties or cities. This strategy will not only remove the labor activists and their organizations from the awkward position mentioned above, it will also contribute to strengthening the labor movement because union federations can gradually replace local politicians for workers to rely on when workers are in dispute with their employers (Kuo 1995). Talks about separating union representation at the regional level began in the early 1990s. In 1994, the Taipei County Federation of Industrial Unions (TCFI) was established. Though the Council of Labor Affairs, the equivalent of the Minis-try of Labor, declared the TCFI illegal, the county government, by having a differ-ent interpretation for an article of the trade union law,18 granted the TCFI legal recognition. Within the next few years, organized workers in other counties and cities followed suit, submitting applications to their local governments. As Table III shows, eight out of twenty-one cities and counties had their city/county federations of industrial unions established by March 1998.

With the exception of Kaohsiung City, all the counties and cities listed in Table III were governed by the DPP, the opposition party at that time, when these federa-tions were established. That they could be established in spite of the central government’s disapproval, and that they also received subsidies from local govern-ments showed how union leaders and labor activists took advantage of the political differences between the local government and the central government. Though the city had a KMT mayor at that time, politicians in Kaohsiung City threatened to freeze the city budget in order to have the federation established because union leaders had made it clear that whether or not the federation could be established would be an election issue (Zeng 1996a, p. 6; 1996b, p. 8). It was therefore not 18The county official in charge of granting the legal recognition has not only a pro-labor record in his

service but also a legal background.

TABLE III

CITY/COUNTY FEDERATIONSOF UNIONSIN TAIWAN

City/County Date of No. of Unions/ Local Government Establishment No. of Members Subsidies Received (NT$)

Taipei County Apr. 11, 1994 38/12,000 2,300,000

Tainan County Nov. 15, 1995 35/10,000 600,000

Kaohsiung County Feb. 2, 1996 39/10,000 700,000

Yilan County Feb. 24, 1997 21/6,000 240,000

Taipei City Mar. 7, 1997 49/47,000 410,000

Kaohsiung City Mar. 21, 1997 36/45,000 820,000

Hsinchu County Aug. 31, 1997 21/47,000 Amount unclear

Miaoli County Feb. 21, 1998 13/7,893 100,000

surprising that their application for establishing the federation was approved before the 1998 mayor election.

Based on these county/city federations of industrial unions, efforts at establish-ing a national federation of industrial unions were also made. The Taiwan Confed-eration of Trade Unions (TCTU) was established on May 1, 1999. This was an apparent attempt to challenge the current Trade Union Law, which only allowed one union federation at the national level. The organizing efforts reached fruitful results after the presidential election, because during his campaign President Chen Shui-bian promised to grant the TCTU legal status.

The electoral victory of the DPP also led to a drastic leadership change in the officially sanctioned and traditionally KMT-controlled Chinese Federation of La-bor. The KMT-nominated candidate lost the election for president of the confedera-tion, and the pro-KMT union cadres left the confederation to establish other na-tional-level union federations. Among them, the most significant one was the National Federation of Labor.19 Therefore, by the end of the summer of 2000 there were at least three national federations of unions: the Chinese Federation of Labor, the Taiwan Confederation of Trade Unions, and the National Federation of Labor. Be-ing the only legally sanctioned national federation, the Chinese Federation of La-bor has the largest membership of all three. The Taiwan Confederation of Trade Unions consisted mainly of unions from the state enterprises and large private en-terprises. The member unions of the National Federation of Labor tend to be occu-pational unions. The split or the proliferation of union federations at the national level was a direct challenge to the Trade Union Law. However, since President Chen made a campaign promise to legally recognize the Taiwan Confederation of Trade Unions, the revision of the Trade Union Law became a policy of the new government. In other words, though hampered by weak organizational strength, organized workers in Taiwan first forged a political partnership with the DPP at various locations, and then followed the party to the national political arena and forced a reregulation of union organization. Figure 1 illustrates the changes in the union organization in the past decade.

Though workers successfully established alternative federations of unions, the cooperative relation between the labor movement and the DPP was challenged when the DPP was no longer the opposition party. The change in the relation could be clearly seen in the revisions of the Labor Standards Law.

B. Revisions of the Labor Standards Law

In comparison with the changes in the union organization, the revisions of the Labor Standards Law more clearly showed the intertwined impacts of democratiza-tion and globalizademocratiza-tion on the labor movement. Like the experience they had in 19The National Federation of Labor played a significant role because its president was a member of

A. Before the mid-1990s

Chinese Federation of Labor

County /city federation of unions

Occupational unions Industrial unions

B. Between the mid-1990s and 2000

Chinese Federation of Labor

County /city federation of unions

County /city federation of industrial unions Occupational unions / industrial unions C. Since 2000 National Federation of Labor Chinese Federation of Labor Taiwan Confederation of Trade Unions

County /city federation of unions

County /city federation of industrial unions

Occupational unions /

industrial unions Industrial unions Industrial unions

union reorganization, labor activists and union cadres took advantage of the politi-cal differences between the ruling and opposition parties. However, after labor ac-tivists and union cadres successfully used political maneuvering to achieve their purpose, they realized that they still had to compromise under the constraints of globalization.

There were two stages in the revisions of the Labor Standards Law. The first stage covered the expansion of the application of the law, and the second stage the changes in the legal limit of work hours. The completion of the first stage resulted in the first important revision of the Labor Standards Law in 1996, twelve years after the law was put into practice. When promulgated in 1984, the law was applied to workers in the manufacturing sector only. Workers in the service and primary sectors were left unprotected. The revision in 1996 extended the application to all workers. During the process of the revision, the Bank Workers’ Union played an important role and successfully developed a cooperative relationship with the DPP members in the Legislative Yuan. Out of the worry that the government’s privatization plan would lead to a deterioration of the labor conditions in the state-owned banks, the Bank Workers’ Union in 1988 began to make appeals to the government, espe-cially the labor administration, to extend the application of the Labor Standards Law to the bank workers.20 Despite many efforts, the union could not persuade the government to make the change. The main opposition came from the bureaucrats in the Ministries of Economic Affairs and Finance who were concerned about the government’s financial cost and employers’ reaction.

At the beginning of 1996, two events changed the strategy of the Bank Workers’ Union. After years of hard work, the union drew a promise from Hsieh Shen-Shan, then the chairman of the Council of Labor Affairs, that the Labor Standards Law would be revised to extend the application to the bank workers. Hsieh, a KMT member who came from a working class background and used to be a union leader, promised the union that he would resign from his position if the revision was not made before July 1 in that year. July 1 passed and the revision was not made. To deliver his promise, Hsieh resigned from his position, but was asked to stay by the premier. Hsieh’s attempted resignation was a signal to the union that their strategy to focus on persuading the administration had reached its limit. Around the same time, also at the beginning of 1996, two DPP members with backgrounds in the labor movement became legislators. The frustration with the government and the appearance of the two DPP members led the Bank Workers’ Union to change their strategy. Instead of focusing on persuading the administration, the union now fo-cused on lobbying legislators. The union soon developed a cooperative relation with the DPP legislators. One of the union leaders even became a member of the Taiwan Labor Front, the labor organization with which the two DPP members used 20For a good study on Taiwan’ privatization process, see Chang (2001). The following account on the

to be affiliated.21 After rounds of negotiations and compromises between the KMT and the DPP, the revision was finally made. The revised Labor Standards Law was applied not only to the bank workers but to all workers.

The cooperative relationship between the DPP and the labor movement was smooth in 1996 because the extension did not seriously hurt the political interests of either the KMT or the DPP. Unlike the DPP members, the KMT legislative mem-bers traditionally had a distant relation with the social movement sector. Though the KMT legislative members did not have any incentive to support the revision, neither did they have any particular reason to object to it. The scenario became different four years later, when the DPP and the KMT were locked in a fight over the work-hour-reduction bill.

Reducing the legal limit of work hours is the major content of the second-stage revision of the Labor Standards Law. The policy was first presented as a joint policy platform by four DPP candidates in the 1989 mayor and county magistrate election (Gu 2001, p. 13). Since the election was the first election for local administrative heads after the lift of the martial law, many policy platforms dealt with overall social and political reforms. The four DPP candidates proposed the concept of a “two-day-weekend” and wanted to reduce the legal limit of work hours from forty-eight to forty hours a week. Though all of these candidates were elected, the “two-day-weekend” policy was not implemented because it was not within the power of the mayor or county magistrate (Gu 2001, p. 14). In the mid-1990s, under the rule of the KMT, the Council of Labor Affairs considered reducing the legal limit of work hours but failed to enact it as a policy. It was not until the presidential election in 2000 that the “two-day-weekend” once again emerged as one of the DPP’s labor policies.22

There after, the DPP won the election and the new government was inaugurated. Labor movement leaders paid a visit to the new chairwoman of the Council of Labor Affairs. At that meeting, labor leaders demanded that the government vali-date its promise and reduce the legal limit of work hours. The government agreed to first reduce the legal limit to forty-four hours a week. When the government’s deci-sion regarding work-hour reduction was known, the KMT legislative members be-gan to consider further reducing the legal limit to eighty-four hours every two weeks mainly to show that they could still determine national policies. To maintain the integrity of the government bill and avoid being humiliated by the KMT, the new government asked leaders of the Chinese Federation of Labor as well as the Chi-nese Confederation of Industries to support the government’s bill. After some per-suasion and negotiation, leaders from both the labor union and the employers’ asso-21One was the general secretary and the other was the major policy advisor of the Taiwan Labor

Front.

22In addition to the DPP presidential candidate Chen Shui-bian, James Soong, another candidate, also proposed to reduce work hours.

ciation reached and signed an agreement to support the government bill. The media reported the agreement as the first successful tripartite agreement in Taiwanese history (Zhongguo shibao, June 14, 2000). Three days later, however, when the Legislative Yuan voted on the work-hour-reduction bill, the KMT’s version won in a landslide victory. Among the 115 members at present, 113 voted to support the KMT bill, including many DPP members (Zhongguo shibao, June 17, 2000).

The victory of the KMT version revealed an important aspect of Taiwanese labor politics: the organizational strength of either the union confederation or the weak-ness of the employers’ association. That was why the agreement signed by the lead-ers of the two federations did not have any real power. The KMT legislative mem-bers did not hesitate to challenge the government bill that supposedly was supported by both industrial and union leaders because they knew that such a move would not adversely affect them politically.

After the KMT’s version was passed in the Legislative Yuan, the government began to consider the possibility of delaying the implementation of the revised bill for a year. The Ministries of the Economic Affairs and Finance also began to dis-cuss with employers the impact of the reduced work hours on the economy. The discussion was focused on whether the government should make the work-hour reduction a “packaged deal.” For example, if the legal limit of the work hours was reduced, the employers would be allowed to have greater flexibility in allocating work hours. Another proposal by employers was to allow the reduced legal limit to be “phased in.” That is, instead of enforcing the new legal limit right after it was promulgated, the government would allow the employers to gradually reduce the work hours over a period of time, perhaps one or two years.

In July, the Chinese Federation of Labor announced its official stand: no “pack-aged deal,” no “phase-in,” and no delay. It should be noted that after the KMT nominated candidate lost the presidential election of the Chinese Federation of Labor in April, the newly elected president of the confederation had worked closely with labor activists of the Labor Party and the Association of Labor Rights. Because of the pro-unification and pro-socialist policies, the Labor Party and the DPP were almost diametrically opposed to each other. After the Chinese Federation of Labor announced its official stand, both the labor organizations and the employers’ asso-ciations held hearings, meetings, symposia, and public forums to express their opin-ions. The labor movement circle wanted the “Three Nos,” and the employers’ asso-ciations desired the packaged deal or the phase-in (Zhongguo shibao, July 18, 2001). In October, KMT party chairman Lian Chan met President Chen Shui-bian and suggested that the government should delay the work-hour reduction for two years. The suggestion was severely criticized by the union leaders and the KMT was con-demned for being inconsistent. The government then decided in November to present its original bill again as a revision to the KMT’s version. The day the government made the decision, the unions and labor movement organizations formed the

“Coa-lition for the 84 Work Hours” to defend the KMT version (Zhongguo shibao, No-vember 23, 2001). Leaders of the Taiwan Confederation of Trade Unions met the DPP legislative members with whom they had worked together on various labor issues. The union leaders who were friendly toward the DPP clearly indicated that they could not accept the DPP government’s attempt to revise the KMT’s version back to the government’s original version because it was a regressive move. On the other hand, leaders of the employers’ association met the KMT legislative members and asked the KMT to give up its version.

By mid-December a compromised version gradually emerged in the Legislative Yuan among members of other political parties. The compromised version stated that the legal work-hour limit would be eighty-four hours every two weeks. How-ever, if the union or more than half of the employees agreed, work hours could be forty-four hours a week after being proposed to, and reviewed by, the city or county government (“Basi gongshi” 2001, p. 24). When the compromised version first emerged, opposition parties, including the KMT, looked set to accept the compro-mised version. Led by the Chinese Federation of Labor, the Coalition for 84 Work Hours began negotiations with the opposition parties. The Coalition insisted that the legal limit be eighty-four hours every two weeks. If the workplace had a union, then the legal limit could be forty-four hours a week after the union agreed, but enterprises that did not have a union had to adopt the limit of eighty-four hours every two weeks (“Basi gongshi” 2001, p. 25).

The position of the Coalition for 84 Work Hours was clear: either workers ob-tained the reduction of work hours to its fullest extent or workers could take advan-tage of the opportunity to organize unions in their workplaces. The difference be-tween the coalition and the political parties, whether it was the DPP or any of the opposition parties, was that the coalition insisted that work hours could be deter-mined only by state regulation or union agreement. The so-called majority of the workers could not be regarded as an equivalent to a union, no matter what the definition of the majority was.23 This position was particularly important under Taiwan’s conditions because many workplaces did not have unions. The small size of the enterprises would make it very easy for the employers to obtain the agree-ment of “the majority of the workers.”

At the end of December, after the DPP and the opposition parties failed to reach a consensus on the legal limit of work hours, the chairman of the Legislative Yuan, a KMT member, used his discretion power and decided that the work-hour-reduc-tion bill was no longer an item of the Legislative Yuan agenda. The settlement was that the KMT version, eighty-four work hours for every two weeks, would be put into practice as of January 1, 2001.

The revision and the passage of the work-hour-reduction bill was a twisted and 23In the various compromised versions presented by the DPP as well as members of opposition

protracted process. It was clear that the labor movement benefited from the struggles between the government and the opposition parties. It was also clear that unions and labor movement organizations had not developed a stable relation with the political parties. The DPP’s repeated efforts in overturning the KMT version and the KMT’s inconsistency over the work-hour reduction both took place in the face of the opposition of the unions and labor movement organizations. Before the work-hour-reduction bill, union leaders and labor activists seldom cooperated with the KMT. However, in the process of defending the passed bill, union leaders and labor activists became the political partners of the KMT as well as of other opposition parties. The KMT’s version of the work-hour-reduction bill was defended because union leaders and labor activists successfully maneuvered in the narrow political arena afforded by the power struggles between the DPP and the opposition parties. The success had little to do with the organizational strength of the labor movement. Half a year after the new work-hour limit was put into practice, labor activists and union cadres found themselves making compromise under the constraint of globalization. In the summer of 2001, in the meetings of the Economic Develop-ment Advisory Committee, an ad-hoc committee summoned by President Chen to plan for Taiwan’s new development strategy, union cadres agreed to allow employ-ers to have greater flexibility in allocating work hours. Facing the high unemploy-ment rate, they also agreed to lift the restriction on using female workers for night shifts (EDAC 2001). Both changes were previously opposed by the same union cadres. This shows that globalization as an economic trend does exerts a constrain-ing effect on what can be achieved under democracy.

V. CONCLUSION

Under the trends of democratization and globalization, the Taiwanese labor move-ment since the 1990s has continuously faced the problem of limited organizational strength, though union leaders and labor activists became more skillful in political maneuvering. Successful political maneuvering can compensate for but cannot re-place the lack of organizational strength. Through the cases of union reorganization and the revisions of the Labor Standards Law, it appears that the objectives of the labor movement could be achieved with limited organizational strength, but only under two conditions: when there was a political difference between the major po-litical parties to exploit and when the trend of globalization did not become a coun-tering force.

Reregulation is an ongoing process. The Council of Labor Affairs has been re-viewing all the major labor regulations including the Trade Union Law, the Collec-tive Bargaining Law, and the Labor Dispute Mediation Law. With limited organiza-tional strength but with a wider political horizon, the Taiwanese labor movement in the future is likely to allocate more resources to lobbying rather than organizational

work. The risk of this strategy is that the gap within the working class will widen because marginalized workers—such as part-time workers, female workers, and unskilled workers—will have a much harder time to mobilize resources for effec-tive lobbying. The marginalized workers, however, will be affected most by the globalization process. How to bridge the gap between different types of workers thus remains a challenge for the Taiwanese labor movement.

REFERENCES

“Basi gongshi huodong dashiji” [The chronology of the activities of the Coalition for 84 Work Hours]. 2001. Laodong qianxian 33: 22–27.

Block, Fred. 1977. “The Ruling Class Does Not Rule.” Socialist Revolution 33: 6–28. Chang, Chin-Fen. 2001. Taiwan gongying shiye minyinghua: Jingji misi de pipan [The

privatization of state-owned enterprises in Taiwan: A critique of the economic myth]. Taipei: Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica.

Chao, Kang. 1991. “Labor, Community, and Movement: A Case Study of Labor Activism in the Far Eastern Chemical Fiber at Hsinpu, Taiwan, 1977–1989.” Ph.D. diss., Univer-sity of Kansas.

Chao, Yung-Mau, and Michael Y. M. Kau. 1993. “Local Government and Political Develop-ment in Taiwan.” In Depth 3, no. 1: 215–36.

Chen, Bao-Rong. 1993. Interview by the author. Union Cadre of the Daya Electric Cable Corporation.

Chen, Ming-tong, and Chu Yun-han. 1992. “Quyuxing lianhe duzhan jingji, difang paixi yu shengyiyuan xuanju: Yixiang shengyiyuan houxuanren beijing ziliao de fenxi” [Locally monopolyzed economy, local factions, and the Taiwan provincial election: An analysis of the background of the candidates for Taiwan provincial election]. Renwen ji shehui

kexue (Guojia kexue weiyuanhui yanjiu hui) 2, no. 1: 77–96.

Choi, Jang-Jip. 1989. Labor and the Authoritarian State: Labor Unions in South Korean

Manufacturing Industries, 1961–1980. Seoul: Korea University Press.

Council of Labor Affairs. 1993. Gonghui xiankuang diaocha baogao [A Survey on the current situation of unions]. Taipei: Council of Labor Affairs

Directorate-General of Budget, Accounting and Statistics (DGBAS). 2001a. News Release, August 14.

———. 2001b. News Release, November 13.

Economic Development Advisory Committee (EDAC). 2001. “Jingji fazhan zixun weiyuanhui gongshi zhaiyao” [A summary of the consensus reached in the meetings of Economic Development Advisory Committee]. Taipei: EDAC.

Fulcher, James. 1988. “On the Explanation of Industrial Relations Diversity: Labour Move-ments, Employers and the State in Britain and Sweden.” British Journal of Industrial

Relations 26, no. 2: 246–74.

Golden, Miriam, and Jonas Pontusson, eds. 1992. Bargaining for Change: Union Politics in

North America and Europe. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press.

Gu, Wa-La. 2001. “Suoduan gongshi douzheng guocheng jiyao” [A summary of the struggle for reduction of work hours]. Laodong qianxian 33: 13–18.

Guo, Guo-Wen. 1998. “Xianshi chanye zonggonghui de chengli” [On the establishment of city/county union federations]. Laodongzhe 79: 16–18.

Hirst, Paul, and Johnathan Zeitlin. 1991. “Flexible Specialization versus Post-Fordism: Theory, Evidence, and Policy Implications.” Economy and Society 20: 1–56.

Hsu, Ji-Feng. 1999. “Wuoguo gonghui zuzhi canyu zhzhi guocheng zhi tantao: yi yinhangyuan gonghui yu laodong jizhunfa kuoda shiyong weili” [A study on the par-ticipation of our country’s unions in the political process: Using the example of the Bank Workers’ Union and the extension of the application of the Labor Standards Law].

Renwen ji shehui kexue jikan 11, no. 3: 395–433.

Hsu, Zheng-Guang. 1987. “Guojia tonghe zhuyi xia de laogong zhengce” [Labor policy under state corporatism]. Paper presented at the Conference on Industrial Relation, held by Academia Sinica, Taipei, October 14–15.

Huang, Chang-Ling. 1997. “State Corporatism in Question: Labor Control in South Korea and Taiwan.” Chinese Political Science Review 28: 25–47.

———. 2000. “Neo-mercantilist Policies and Sectoral Politics: Taiwan’s Acquiescent Work-ing Class.” Anthropology of Work Review 21, no. 3: 15–18.

Huang, Tian-Hou. 1993. Interview by the author. Chief of the Section of Labor Disputes and Mediation, Tainan County Bureau of Labor Affairs.

Huntington, Samuel. 1991. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth

Cen-tury. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press.

Joseph, Antoine. 1992. “Modes of Class Formation.” British Journal of Sociology 43, no. 3: 345–71.

Koo, Hagen. 1989. “The State, Industrial Structure, and Labor Politics: Comparison of Tai-wan and South Korea.” In TaiTai-wan: A Newly Industrialized State, ed. Hsin-Huang Michael Hsiao and Wei-Yuan Cheng. Taipei: National Taiwan University.

Korea Labor Institute (KLI). 1992. Major Indicators of Labor Statistics. Seoul: Korea La-bor Institute.

Kotz, David M. 1994. “The Regulation Theory and the Social Structure of Accumulation Approach.” In Social Structures of Accumulation: the Political Economy of Growth and

Crisis, ed. David M. Kotz, Terrence McDonough, and Michael Reich. New York:

Cam-bridge University Press.

Kotz, David M.; Terrence McDonough; and Michael Reich, eds. 1994. Social Structures of

Accumulation: The Political Economy of Growth and Crisis. New York: Cambridge

University Press.

Kuo, Cheng-Tian. 1995. Grobal Competitiveness and industrial Growth in Taiwan and the

Philippines. Pittsburgh, Pa.: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Lash, Scott, and John Urry. 1987. The End of Organized Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Linz, Juan J., and Alfred Stepan, eds. 1996. Problems of Democratic Transition and

Con-solidation: Southern Europe, South America, and Post-Communist Europe. Baltimore,

N.Y.: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Mainwaring, Scott; Guillermo O’Donnell; and Samuel Valenzuela, eds. 1992. Issues in

Democratic Consolidation: The New South American Democracies in Comparative Perspective. Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press.

Pang, Chien-Kuo. 1990. Wuoguo laogong yundong fazhan zhi qushi jiqi yinying cuoshi zhi

yanjiu [Research on the development trend of our country’s labor movement and the

government’s response]. Taipei: Research, Development, and Evaluation Commission; Executive Yuan.

Em-ployer Organizations and Trade Unions in Changing Industrial Relations, ed. Colin

Crouch and Frederick Traxler. London: Sage Publisher.

Piore, Michael, and Charles Sable. 1984. The Second Industrial Divide: Possibilities for

Prosperity. New York: Basic Books.

Pontusson, Jonas. 1992. “Introduction: Organizational and Political Economic Perspectives on Union Politics.” In Bargaining for Change: Union Politics in North America and

Europe, ed. Merriam Golden and Jonas Pontusson. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University

Press.

Przeworski, Adam, and Fernando Limongi. 1997. “Modernization: Theories and Facts.”

World Politics 49: 155–83.

“Quan fangwei youshi yingzhan xin quanqiuhua” [Meeting the challenge of the new glo-balization through advantages of all aspects]. 2000. Tianxia zazhi, tekan 28: 58–62. Shieh, G. S. 1989. “Heishou bian toujia: Taiwan zhizaoye zhong de jieji liudong” [From

black hands to boss: Class mobility in Taiwan’s manufacturing industry]. Taiwan shehui

yanjiu jikan 22: 11–54.

Shin, Kwang-Yong. 1994. Kyekup kwa nodong undong ui sahoe hak [The sociology of class and labor movements]. Seoul: Nanam Publisher.

Wu, Nai-teh. 1987. “The Politics of a Regime Patronage System: Mobilization and Control with an Authoritarian Regime.” Ph.D. diss., University of Chicago.

Zeng, Wen-Sheng. 1996a. “Zhuanfang gaoxiong shi chanye zonggonghui choubeihui zhaojiren” [A special interview with the chairman of the preparatory committee of the Kaohsiung City Federation of Industrial Unions]. Laodongzhe 83: 6–7.

———. 1996b. “Zhuanfang gaoxiong xian chanye zonggonghui lishizhang” [A special in-terview with the chairman of the Board of the Kaohsiung County Federation of Indus-trial Unions]. Laodongzhe 83: 8–9.

Zolberg, Aristide R. 1986. “How Many Exceptionalisms?” In Working-Class Formation:

Nineteenth-Century Patterns in Western Europe and the United States, edited by Ira