Enhanced critical current density

in the pressure-induced magnetic

state of the high-temperature

superconductor FeSe

Soon-Gil Jung1, Ji-Hoon Kang1, Eunsung Park1, Sangyun Lee1, Jiunn-Yuan Lin2,

Dmitriy A. Chareev3, Alexander N. Vasiliev4,5,6 & Tuson Park1

We investigate the relation of the critical current density (Jc) and the remarkably increased

superconducting transition temperature (Tc) for the FeSe single crystals under pressures up to

2.43 GPa, where the Tc is increased by ~8 K/GPa. The critical current density corresponding to the

free flux flow is monotonically enhanced by pressure which is due to the increase in Tc, whereas

the depinning critical current density at which the vortex starts to move is more influenced by the pressure-induced magnetic state compared to the increase of Tc. Unlike other high-Tc

superconductors, FeSe is not magnetic, but superconducting at ambient pressure. Above a critical pressure where magnetic state is induced and coexists with superconductivity, the depinning Jc abruptly increases even though the increase of the zero-resistivity Tc is negligible, directly

indicating that the flux pinning property compared to the Tc enhancement is a more crucial

factor for an achievement of a large Jc. In addition, the sharp increase in Jc in the coexisting

superconducting phase of FeSe demonstrates that vortices can be effectively trapped by the competing antiferromagnetic order, even though its antagonistic nature against superconductivity is well documented. These results provide new guidance toward technological applications of high-temperature superconductors.

The technological application of superconductors hinges on how to preserve a zero-resistance state at high temperature while maintaining large electrical currents. The discovery of copper-based high-temperature superconductors (HTSs) brought great excitement not only because of its unconventional superconduct-ing nature, but also because of its high superconductsuperconduct-ing transition temperature (Tc), which was expected

to open the door for revolutionary applications at temperatures higher than liquid nitrogen temperature (= 77 K) (refs 1–3). A key issue for practical applications of superconductors is the necessity to increase the value of the depinning critical current density (Jc), at which magnetic flux lines (or vortices) start to

flow and energy dissipation occurs. For decades, several approaches effectively enhanced the Jc of HTSs

by introducing and/or manipulating the extrinsic defects that suppress superconductivity4,5. Because the

1Department of Physics, Sungkyunkwan University, Suwon 440-746, Republic of Korea. 2Institute of Physics, National Chiao Tung University, Hsinchu 30010, Taiwan. 3Institute of Experimental Mineralogy, Russian Academy of Sciences, Chernogolovka, Moscow Region 142432, Russia. 4Low Temperature Physics and Superconductivity Department, Physics Faculty, Moscow State University, 119991 Moscow, Russia. 5Theoretical Physics and Applied Mathematics Department, Institute of Physics and Technology, Ural Federal University, Ekaterinburg 620002, Russia. 6National University of Science and Technology “MISiS”, Moscow 119049, Russia. Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to S.-G.J. (email: prosgjung@gmail.com) or T.P. (email: tp8701@skku. edu)

Received: 15 June 2015 Accepted: 14 October 2015 Published: 09 November 2015

OPEN

www.nature.com/scientificreports/

flux lines have a normal state within the core, they tend to be pinned at defects where superconductivity is suppressed, i.e., extrinsic pinning effects.

Another possible approach to improve the Jc is associated with an intrinsic property of materials, e.g.,

a coexisting order with superconductivity as an intrinsic pinning source. Recently, it has been proposed that magnetism may be conducive to holding the vortex, which leads to the enhancement of the Jc

(refs 6–11). Several high-Tc superconductors, such as La2−xSrxCuO4 and Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2, are candidate

materials for the intrinsic pinning because superconductivity occurs in the vicinity of an antiferromag-netically ordered state6–8. Superconductivity in those materials, however, requires a chemical substitution

that inherently induces defects or site disorder, intertwining the effects of impurities and intrinsic pin-ning on Jc. In addition, it is still controversial if the magnetic order arises from macroscopically phase

separated domains or from an intrinsic coexisting phase on a microscopic level. Therefore, in order to clarify the role of the intrinsic pinning on Jc, it is crucial to perform a systematic study on a high-Tc

compound that is superconducting in stoichiometric form and tunable between superconducting and magnetic ground states by non-thermal control parameters.

The binary high-Tc superconductor FeSe is a promising candidate to probe the effects of the intrinsic

pinning and the Tc on the Jc, because superconductivity which appears at ~10 K without introducing a

hole or electron in the parent compound is greatly tunable up to 37 K by application of pressure12,13. In

addition, an emergence of magnetic state at pressure ~0.8 GPa makes it a more interesting material in its basic properties and application issues14,15. A T

c above 100 K in FeSe monolayer shows its promising

potential for the possibility of application16. In the following, we report the evolution of the critical

cur-rent density (Jc) of FeSe single crystals as a function of pressure in connection with the increase of Tc.

The current-voltage (I− V) characteristic curves as well as temperature dependences of the electrical resistivity show a sharp contrast across the critical pressure (Pc = 0.8 GPa) above which μSR

measure-ments reported a pressure-induced AFM state that coexists with superconductivity14,15. There are a few

interesting behaviours. First, the superconducting (SC) transition is sharp at low pressures, but becomes broader in the coexisting SC state for P > Pc. Secondly, temperature dependence of the critical current

density follows the prediction by the δTc-pinning at low pressures (P < Pc), while the δl-pinning becomes

more effective at higher pressures. Thirdly, amplitude of Jc is strongly enhanced in the coexisting state.

The fact that physical pressure does not induce extra disorder suggests that the enhancement in Jc as well

as the change in the pinning mechanism in the coexisting phase arises from the antiferromagnetically ordered state.

Results

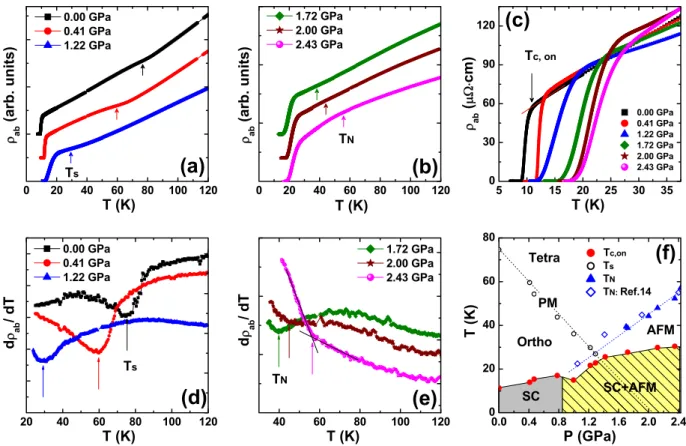

Figure 1(a,b) representatively shows the in-plane electrical resistivity (ρab) of FeSe as a function of

tem-perature for several pressures. For clarity, ρab(T) for different pressures was rigidly shifted upwards. At

ambient pressure, a change in the slope of ρab occurs at 75 K due to the tetragonal to orthorhombic

struc-tural phase transition. Unlike other iron-based superconductors, this strucstruc-tural transition is not accom-panied by a magnetic phase transition. The structural transition temperature (Ts), which is assigned

as a dip in dρab/dT, progressively decreases with increasing pressure at a rate of − 36.7 K/GPa and is

not observable for pressures above 1.3 GPa where Ts becomes equal to the superconducting transition

temperature Tc, as shown in Fig. 1(d). With further increasing pressure, an additional feature appears in

the normal state as a dip or a slope change in dρab/dT, as shown in Fig. 1(e). In contrast to Ts, this new

characteristic temperature linearly increases with pressure and is nicely overlaid with the TN determined

from μSR results14, showing that the resistivity anomaly arises from the paramagnetic to

antiferromag-netic phase transition, as described in Fig. 1(f).

Figure 1(c) presents that the temperature for the onset of the superconducting transition (Tc,on)

grad-ually increases with increasing pressure at a rate of 8 K/GPa. Also, the transition width Δ Tc, which was

defined as the difference between the 90 and 10% resistivity values of the normal state at Tc,on, decreases

with increasing pressure at low pressures because of the enhanced superconductivity under pressure. At pressures P > 0.8 GPa, where superconductivity coexists with a magnetically ordered state on a micro-scopic scale14,15, Δ T

c becomes broader even though Tc,on increases with increasing pressure. The

dichot-omy between Tc,on and Δ Tc in the coexisting phase suggests that the pressure-induced antiferromagnetic

phase acts as an additional source for breaking Cooper pairs.

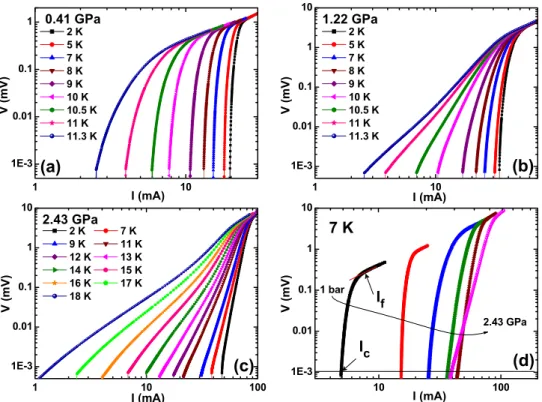

Correlation between the anomalous broadening in the Δ Tc and the magnetic phase is further

sup-ported by a qualitative difference in the current-voltage (I−V) curves of FeSe across the critical pressure

Pc. As shown in Fig. 2(a–d), the voltage curve sharply decreases with decreasing current at 0.41 GPa,

i.e., the pressure where superconductivity itself only exists. In the coexisting phase (P > Pc), on the other

hand, the voltage curve develops a knee with decreasing current. Figure 2(d) summarizes pressure evo-lution of the transition broadening in the I−V curve at 7 K. These anomalous broadenings in the I−V curves are also considered due to the pressure-induced antiferromagnetic state.

Discussion

Two characteristic critical currents, Ic and If from the I−V curves, are marked by the two arrows in

Fig. 2(d). The depinning critical current (Ic) was obtained from the 1 μV criterion where the

vorti-ces start to move and the free-flux-flow (FFF) current (If) was obtained from the point where vortices

temperature dependence of the critical current densities Jf and Jc estimated from If and Ic, respectively.

Both Jf and Jc were significantly improved with increasing pressure. The FFF current density Jf(T), which

is concerned with thermally activated flux flow with increasing Tc,on, is best explained by the empirical

relation Jf(T) ~ [1 − (T/Tc,on)n], with n = 2.6 ± 0.2 indicated by solid lines in Fig. 3(a). The curves all

col-lapse onto a single curve, as shown in Fig. 3(c), which cannot be explained by the depairing current density (Jd) given by Jd(t) ∝ (1 − t2)3/2(1 + t2)1/2 (dashed line)18, nor by the Joule heating, Jheating (Δ T ∝ J2)

which is caused by the contact resistance (dotted line)19. Rather, they collapse onto the curve expected

from the δTc-pinning mechanism (solid line), Jf(t) ∝ (1 − t2)7/6(1 + t2)5/6, suggesting that the temperature

dependence of the FFF current density is primarily determined by spatial variations in Tc (refs 20,21).

Figure 3(b) shows the pressure evolution of the depinning critical current density (Jc), usually called

the critical current density, as a function of temperature. At 1.8 K, the lowest temperature measured, Jc

increases in commensurate with Tc,0 with increasing pressure, while Jc in the coexisting phase is strongly

enhanced from 1.89 kA/cm2 at 0.41 GPa (red circles) to 3.24 kA/cm2 at 1.22 GPa (blue triangles). Here,

we used the zero-resistivity SC transition temperature (Tc,0) with applied current density (J) ~ 1 A/cm2.

Resistance is not zero any more above the Jc where vortices start to move, which is significantly

influ-enced on the pinning properties of samples, such as pinning strength, density of pinning sites, and so on. Therefore, the Jc comparison by the Tc,0 is reasonable than the comparison by the Tc,on. Considering

that the increase in Tc,0 is negligible at 1.2 GPa, the anomalous jump in Jc as shown in Fig. S1 in SI,

deviates from the trend in Jc as a function of Tc,0, underlining that an additional source of pinning

is indeed required to explain this anomaly. The possibility of the enhancement in Jc due to improved

grain boundary connectivity has been reported in some high-Tc cuprate superconductors22,23 or in the

iron-based polycrystalline superconductor Sr4V2O6Fe2As2 (ref. 24). Because the studied FeSe samples

are single crystalline specimens, however, the lack of a weak-link behaviour in the field dependence of Jc rules out the possibility of grain boundary as the additional pinning source (see Fig. S2 in SI).

Rather, the simultaneous enhancement in Jc and appearance of antiferromagnetism indicate that the

Figure 1. Electrical resistivity and phase diagram of FeSe single crystals. (a,b) In-plane electrical

resistivity (ρab) is plotted as a function of temperature for selective pressure. Arrows mark the structural

(Ts) and antiferromagnetic phase transition (TN) in (a,b), respectively. ρab for different pressures was

rigidly shifted upwards for clarity. (c) ρab is magnified near the superconducting transition region, where

Tc,on is defined as the onset temperature of the SC phase transition. (d,e) First temperature derivative

of the resistivity is shown as a function of temperature. Arrows mark Ts and TN in (d,e), respectively.

(f) Temperature-pressure phase diagram of FeSe. SC, AFM, and PM stand for superconducting,

antiferromagnetic, and paramagnetic phase, respectively. Tetra and Ortho are the acronym of tetragonal and orthorhombic crystal structure.

www.nature.com/scientificreports/

pressure-induced magnetic state leads to an inhomogeneous SC phase and is conducive to the trapping of magnetic flux lines. With further increase in pressure, both Jc and Tc,0 increase.

The additional flux pinning caused by the antiferromagnetic (AFM) order in the FeSe is reflected in the different temperature dependence of Jc across the critical pressure Pc. As shown in Fig. 3(d), the

normalized self-field critical current density Jc(t0) as a function of the reduced temperature (t0 = T/Tc,0)

is well described by the δTc-pinning mechanism (solid line) for P < Pc, where the Tc fluctuates due to

defects, such as Se deficiencies and point defects, which are the main sources for trapping the vortices. For P ≥ Pc, however, Jc(t0) shows a completely different behaviour: the curvature of Jc near Tc,0 is positive,

while it is negative at lower pressures. Also with increasing pressure, Jc deviates further away from the

δTc-pinning and at 2.43 GPa becomes close to the curve predicted by δl-pinning (dashed line), Jc(t) ∝

(1 − t2)5/2(1 + t2)−1/2, suggesting that spatial fluctuations in the mean free path (l) of the charge carrier

becomes important for flux pinning at high pressures21. As shown in Fig. S3 in SI, the pressure-induced

crossover in Jc(T) is almost independent of the magnetic field, indicating that the vortex pinning within

the AFM phase is robust against variations in the magnetic field strength.

A similar crossover from δTc-pinning to δl-pinning has been reported in MgB2 when additional

pin-ning sources, such as grain boundaries or inclusions of nanoparticles by chemical doping, were intro-duced25 or hydrostatic pressure was applied26. In the present study, a broadening of superconducting

transition with the pressure-induced AFM state is important for the crossover. A possibility of enhanced mean free path (l ∝ ξ) fluctuations due to the competition between superconducting and AFM order parameters and change in the superconducting coherence length (ξ) with pressure may be closely related to the crossover because the disorder parameter that characterizes the collective vortex pinning proper-ties is proportional to ξ and to 1/ξ3 for δT

c- and δl-pinning, respectively21,26. As shown in Fig. S4 in SI,

the values of the upper critical field Hc2(0) increase with applied pressure, indicating that the change in

ξ may be of some relevance to the crossover.

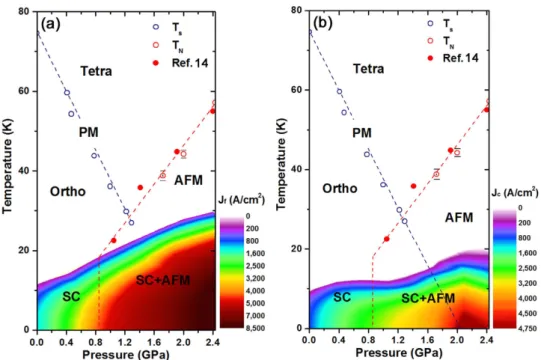

Figure 4(a) shows a contour plot of the free-flux-flow current density (Jf) for FeSe as a function of

temperature and pressure at zero field, where the colours represent different values of Jf. Also plotted

are the structural and the magnetic phase boundaries that are obtained from the electrical resistivity measurements; these boundaries are consistent with those reported in previous works14,15. The contour

of Jf monotonically increases with an increase in Tc by pressure, while Jc deviates from the monotonic

pressure evolution of Jf. Instead, the contour of Jc reflects the appearance of the pressure-induced AFM

Figure 2. Evolution of transport properties of FeSe single crystals under pressure. (a–c) Logarithmic

plots of the current-voltage (I−V) results at pressures of 0.41, 1.22 and 2.43 GPa. The I− V curves become broader at pressure above 0.8 GPa, where an AFM phase is induced. (d) Pressure evolution of the isothermal I−V curves at 7 K. The depinning critical current (Ic) is estimated by using the criterion of 1 μV, and the

free-flux-flow critical current (If) is the value of the current at the inflection point, both of which are

phase, as shown in Fig. 4(b). The Jc as well as the Tc,0 gradually increases with increasing pressure,

how-ever near the critical pressure where AFM phase is induced, Jc shows a high increase compared to Tc,0, as

mentioned in Fig. 3(b). We note that Jc shows a dome shape centred around 2.1 GPa, the projected critical

pressure where the tetragonal to orthorhombic structural phase transition temperature is extrapolated to

T = 0 K inside the dome of superconductivity27. A Possibility of flux pinning by structure transition had

been reported in the superconducting A15 compounds such as V3Si (refs 28,29), and further work is in

progress to better understand the role of structural fluctuations in producing the peak in Jc.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we studied the correlation between superconducting transition temperature and critical current density for the high-Tc superconductor FeSe. Both Tc,on and Jf increase with pressure, which

is insensitive to the presence of AFM states, on the other hand, the superconducting transition width becomes considerably broader with the emergence of the AFM phase, and Jc is prominently enhanced in

the coexisting phase. This behaviour reflects that the AFM phase not only provides an additional source of vortex pinning, but also makes the system susceptible to the inhomogeneous SC phase. Even though these observations are only specific to FeSe, they are expected to guide theoretical as well as experimental efforts to better understand the vortex pinning in the high-Tc superconductors where competing orders

coexist on a microscopic scale. Further, when combined with well-known extrinsic pinning techniques, intrinsic magnetic pinning will provide a blueprint for greatly enhancing the critical current density, thereby bringing one step closer to the technological applications of high-temperature superconductors. Figure 3. Critical current densities of FeSe and the flux pinning mechanism under pressure. (a,b) The

free-flux-flow critical current density Jf(T) monotonically increases with increasing Tc,on by pressure and is

well explained by the relation 1 − (T/Tc,on)2.6±0.2 over the entire pressure ranges (solid lines). On the other

hand, the depinning critical current density Jc(T) reveals a large enhancement at 1.22 GPa (solid triangles)

even though the Tc,0 is similar to the value at 0.41 GPa (solid circles). Δ Jc is the jump in the critical current

density at 1.22 GPa, which accounts for about 70% increase from that at 0.41 GPa. (c) Normalized Jf(t) is

plotted as a function of the reduced temperature t (= T/Tc,on) for several pressures. All the curves collapse

together, indicating that the underlying mechanism for the Jf is independent of enhanced Tc,on by pressure.

The Jf(t) curves follow the prediction by δTc-pinning (solid line) – see the text for detailed discussion. (d)

Normalized Jc(t0) is plotted as a function of another reduced temperature t0 (= T/Tc,0), where Tc,0 is the

zero-resistance transition temperature. Jc(t0) closely follows the prediction from δTc-pinning at low pressures,

while it deviates from δTc-pinning at pressures above a critical pressure (= 0.8 GPa), above which a magnetic

state is induced. With further increase in pressure, Jc(t0) crosses into a region where δl-pinning dominates its

www.nature.com/scientificreports/

Methods

The c-axis-oriented high-quality FeSe1−δ (δ = 0.04 ± 0.02) single crystals with a tetragonal structure

(space group P4/nmm) were synthesised in evacuated quartz tubes in permanent gradient of temperature by using an AlCl3/KCl flux. The synthesis technique used to fabricate the FeSe single crystals and their

high-quality are described in detail elsewhere30,31. The current-voltage (I−V) characteristics of FeSe were

measured under hydrostatic pressures of 0.00, 0.41, 1.22, 1.72, 2.00, and 2.43 GPa. The physical pressure was applied by using a hybrid clamp-type pressure cell with Daphne 7373 as the pressure-transmitting medium, and the value of the pressure at low temperatures was determined by monitoring the shift in the Tc of high-purity lead (Pb) as a manometer. The I−V characteristic measurements under pressure

were performed in the physical property measurement system (PPMS 9T, Quantum Design), where the electrical current was generated by using an Advantest R6142 unit and the voltage was measured by using an HP34420A nanovoltmeter. The depinning critical current (Ic) was obtained from the 1 μV

criterion instead of 1 μV/cm in the I−V curves due to a small size of FeSe single crystals10,32. A few

layers of FeSe in the FeSe single crystals were easily exfoliated by using adhesive tape, which is similar to the exfoliation technique that is used for graphene33. The size of the measured crystals is typically

590 × 210 × 5 μm3. Quasi-hydrostatic pressure was achieved by using a clamp-type piston-cylinder

pres-sure cell with Daphne oil 7373 as the prespres-sure-transmitting medium. The magnetic fields were applied parallel (H//ab) to the ab-plane of the samples.

References

1. Nishijima, S. et al. Superconductivity and the Environment: a Roadmap. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 26, 113001 (2013). 2. Hull, J. R. Applications of High-temperature Superconductors in Power Technology. Rep. Prog. Phys. 66, 1865–1886 (2003). 3. Larbalestier, D. C., Gurevich, A., Feldmann, D. M. & Polyanskii, A. High-Tc Superconducting Materials for Electric Power

Applications. Nature 414, 368–377 (2001).

4. Baert, M., Metlushko, V. V., Jonckheere, R., Moshchalkov, V. V. & Bruynseraede, Y. Composite Flux-line Lattices Stabilized in Superconducting Films by a Regular Array of Artificial Defects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 3269–3272 (1995).

5. Civale, L. et al. Vortex Confinement by Columnar Defects in YBa2Cu3O7 Crystals: Enhanced Pinning at High Fields and Temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 67, 648–651 (1991).

6. Zaanen, J. Superconductivity: Technology meets quantum criticality. J. Nature Mater. 4, 655–656 (2005).

7. Prozorov, R. et al. Coexistence of Long-range Magnetic Order and Superconductivity from Campbell Penetration Depth Measurements. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 22, 034008 (2000).

8. Prozorov, R. et al. Intrinsic Pinning on Structural Domains in Underdoped Single Crystals of Ba(Fe1−xCox)2As2. Phys. Rev. B 80, 174517 (2009).

Figure 4. Phase diagram of the critical current densities, Jf and Jc. (a) The free-flux-flow critical current

density (Jf), above which vortices flow freely, is plotted as a function of temperature and pressure. Here,

the colour represents the absolute value of Jf. The magnetic and the superconducting (SC) transition

temperatures based on the resistivity measurements are also plotted. For reference, we show the phase transition temperature from paramagnetic (PM) to antiferromagnetic (AFM) states based on the μSR measurements in ref. 14 (solid red circles). (b) A contour map of the depinning critical current density (Jc) is

9. Gammel, P. L. et al. Enhanced Critical Currents of Superconducting ErNi2B2C in the Ferromagnetically Ordered State. Phys. Rev.

Lett. 84, 2497–2500 (2000).

10. Weigand, M. et al. Strong Enhancement of the Critical Current at the Antiferromagnetic Transition in ErNi2B2C Single Crystals.

Phys. Rev. B 87, 140506(R) (2013).

11. Refal, T. F. Antiferromagnetism and Enhancement of Superconductivity. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2, 149–152 (1989). 12. Hsu, F. C. et al. Superconductivity in the PbO-type Structure α-FeSe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. (USA) 105, 14262 (2008).

13. Mizuguchi, Y., Tomioka, F., Tsuda, S., Yamaguchi, T. & Takano, Y. Superconductivity at 27 K in Tetragonal FeSe under High Pressure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 93, 152505 (2008).

14. Bendele, M. et al. Coexistence of Superconductivity and Magnetism in FeSe1−x under Pressure. Phys. Rev. B 85, 064517 (2012). 15. Bendele, M. et al. Pressure Induced Static Magnetic Order in Superconducting FeSe1−x. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 087003 (2010). 16. Ge, J. F. et al. Superconductivity above 100 K in Single-Layer FeSe Films on Doped SrTiO3. Nat. Mater. 14, 285–289 (2015). 17. Gupta, S. K. et al. I−V Characteristic Measurements to Study the Nature of the Vortex State and Dissipation in MgB2 Thin Films.

Phys. Rev. B 66, 104525 (2002).

18. Kunchur, M. N., Lee, S.-I. & Kang, W. N. Pair-breaking Critical Current Density of Magnesium Diboride. Phys. Rev. B 68, 064516 (2003).

19. Xiao, Z. L., Andrei, E. Y., Shuk, P. & Greenblatt, M. Joule Heating Induced by Vortex Motion in a Type-II Superconductor. Phys.

Rev. B 64, 094511 (2001).

20. Blatter, G., Feigel’man, M. V., Geshkenbein, V. B., Larkin, A. I. & Vinokur, V. M. Vortices in High-temperature Superconductors.

Rev. Mod. Phys. 66, 1125–1388 (1994).

21. Griessen, R. et al. Evidence for Mean Free Path Fluctuation Induced Pinning in YBa2Cu3O7 and YBa2Cu4O8 Films. Phys. Rev.

Lett. 72, 1910–1913 (1994).

22. Tomita, T., Schilling, S., Chen, L., Veal, B. W. & Claus, H. Enhancement of the Critical Current Density of YBa2Cu3Ox

Superconductors under Hydrostatic Pressure. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 077001 (2006).

23. Bud’ko, S. L., Davis, M. F., Wolfe, J. C., Chu, C. W. & Hor, P. H. Pressure and Temperature Dependence of the Critical Current Density in YBa2Cu3O7−δ Thin Films. Phys. Rev. B 47, 2835–2839 (1993).

24. Shabbir, B. et al. Hydrostatic Pressure: A Very Effective Approach to Significantly Enhance Critical Current Density in Granular Iron Pnictide Superconductors. Sci. Rep. 5, 8213 (2015).

25. Ghorbani, S. R., Wang, X. L., Hossain, M. S. A., Dou, S. X. & Lee, S.-I. Coexistence of the δ l and δ Tc Flux Pinning Mechanisms in Nano-Si-doped MgB2. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 23, 025019 (2010).

26. Shabbir, B., Wang, X. L., Ghorbani, S. R., Dou, S. X. & Xiang, F. Hydrostatic Pressure Induced Transition from δ Tc to δ ℓ Pinning Mechanism in MgB2. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 28, 055001 (2015).

27. Miyoshi, K. et al. Enhanced superconductivity on the tetragonal lattice in FeSe under hydrostatic pressure. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 83, 013702 (2014).

28. Dew-Hughes, D. Flux Pinning Mechanisms in Type-II Superconductors. Phil. Mag. 30, 293–305 (1974).

29. Brand, R. & Webb, W. W. Effects of Stress and Structure on Critical Current Densities of Superconducting V3Si. Solid State

Commun. 7, 19–21 (1969).

30. Chareev, D. et al. Single Crystal Growth and Characterization of Tetragonal FeSe1−x Superconductors. CrystEngComm 15, 1989–1993 (2013).

31. Lin, J.-Y. et al. Coexistence of Isotropic and Extended s-wave Order Parameters in FeSe as revealed by Low-temperature Specific Heat. Phys. Rev. B 84, 220507(R) (2011).

32. Li, G., Andrei, E. Y., Xiao, Z. L., Shuk, P. & Greenblatt, M. Onset of Motion and Dynamic Reordering of a Vortex Lattice. Phys.

Rev. Lett. 96, 017009 (2006).

33. Novoselov, K. S. et al. Electric Field Effect in Atomically Thin Carbon Films. Science 306, 666–669 (2004).

Acknowledgements

We thank W. N. Kang, S. Lin, and J. D. Thompson for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of Korea grant funded by the Korean Ministry of Science, ICT and Planning (No. 2012R1A3A2048816). This work was supported in part by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Russian Federation within the framework of the Increase Competitiveness Program of the National University of Science and Technology “MISiS” (Contract No. K2-2014-036).

Author Contributions

S.-G.J., J.-H.K., E.P. and S.L. performed the I− V measurements at various pressures. D.A.C., J.-Y.L. and A.N.V. provided the FeSe single crystals. S.-G.J. and J.-H.K. analysed the data and discussed the results with all authors. The manuscript was written by S.-G.J. and T.P. with inputs from all authors.

Additional Information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at http://www.nature.com/srep Competing financial interests: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

How to cite this article: Jung, S.-G. et al. Enhanced critical current density in the pressure-induced

magnetic state of the high-temperature superconductor FeSe. Sci. Rep. 5, 16385; doi: 10.1038/srep16385 (2015).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Com-mons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/