SIGBPS Workshop on Business

Processes and Services

(BPS'13)

December 15, 2013

Milan, Italy

Table of Contents

Multi-agent Based Cooperative Framework for Managing Information Systems

Security Risk···4 Nan Feng, Minqiang Li, Fuzan Chen, Jin Tian

Towards a Multi-level Framework to Analyze Mobile Payment Platforms···9 AvinashGannamaneni, Jan Ondrus

Linking IT-Enabled Collaboration and Performance in the SME Context:

The Role of Responsiveness Capabilities···14 Hsin-Lu Chang, Daniel Yen Shueh, Taiwan Kai Wang

Fostering a Seamless Customer Experience in Cross-Channel Electronic Commerce···21 Jaeki Song, Miri Kim, Jeff Baker, Junghwan Kim

The Effects of Firms' Resources and Value Co-creation Activities on Mobile

Service Innovation···27 Miri Kim, Jaeki.song, Jason.triche

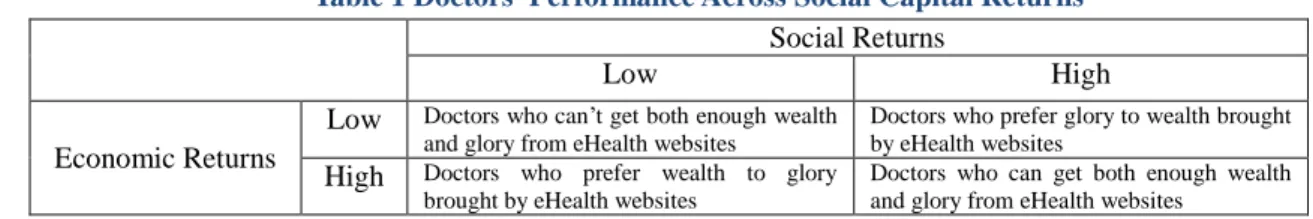

Exploring the Impact of Social Capital Investment on Doctor's Returns

on eHealth Website···33 Shan Shan Guo, Xitong Guo

Ambidexterity in Software Product Development: An Empirical Investigation···39 Kannan Mohan, Balasubramaniam Ramesh

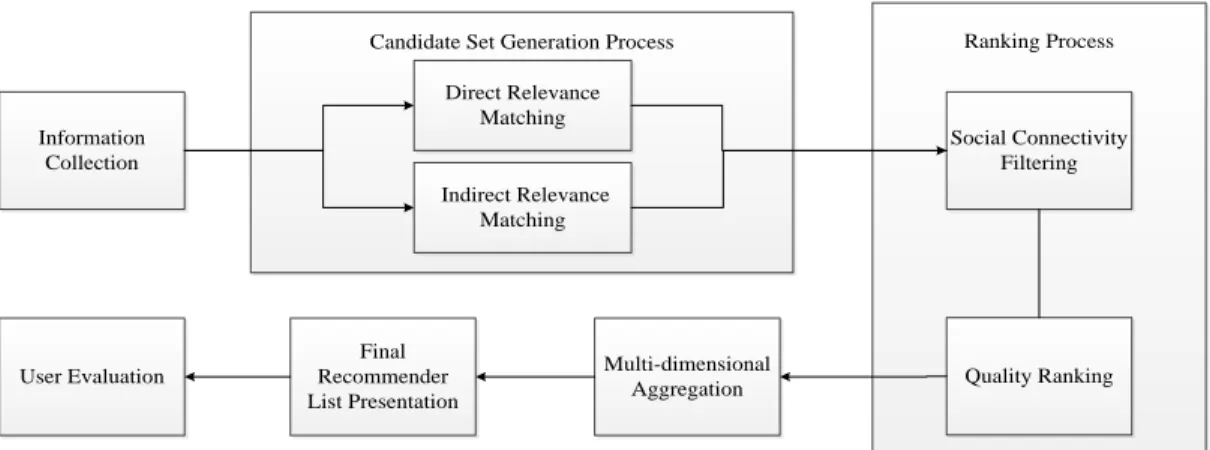

An Integration Process Model for Supervisor Recommendation Services···46 Mingyu Zhang, Jian Ma, Chen Yang, Hongbing Jiang, Zhiying Liu, Jianshan Sun

An Architecture for Integrating Cloud Computing and Process Management···52 Daniel E. O’Leary

Third-Party Recommendation From Online Recommendation Agents:

The Think Aloud Method and Verbal Protocol Analysis···58 Yani Shi, Chuan-Hoo Tan, Choon Ling Sia

How Patient Adopt Online Healthcare Information? An Empirical Study of

Online Q&A Community···63· Jiahua Jin, Xiangbin Yan, Yumei Li, YiJun Li

Exploring Impact of Research Social Networking Services on Research Dissemination···69 Haidan Liang, Jian Ma, Thushari Silva1, Mingyu Zhang, Xu Yunhong, Huaping Chen

Business Rules, Decisions and Processes: Five Reflections upon Living Apart

Together···76 Jan Vanthienen, Filip Caron and Johannes De Smedt

Use of Business Network Analysis for Identifying Financial Fraud Features···82 Chen Zhu, Jinbi Yang, Wenping Zhang, Choon Ling Sia, Stephen S.Y. Liao

Ever-Changing Workarounds: A Model for Workaround Management Lifecycle in

Healthcare Workflow···88 Shaokun Fan, Yu Tong, J. Leon Zhao

Exploring the Potential of User Segmentation in CQA···94 Jiawei Wang, Yiyang Bian, Yujing Xu, Stephen S.Y. Liao

Investigation on the relationship between China’s social media and the purchases

made on the e-Commerce platforms for better promotion strategies···99 Terence Chun-Ho Cheung

Survival Analysis on Hacker Forums···106 Xiong Zhang, Chenwei Li

OWSDR: An Ontology-based Web Service Discovery and Selection System···111 Wenping Zhang and Raymond Y.K. Lau

Multi-agent Based Cooperative Framework for Managing Information

Systems Security Risk

Nan Feng*,Minqiang Li, Fuzan Chen, Jin Tian

College of Management and Economics, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, P. R. China *Corresponding author. Tel.: +86-22-27404796; fax: +86-22-27404796.

E-mail address: fengnan@tju.edu.cn

Abstract: Given the increasing collaboration between organizations, the information sharing

across the allied organizations is critical to effectively manage information systems security (ISS) risk. Nevertheless, few previous studies on ISS take the issue of information sharing into account. In this paper, we develop a multi-agent based cooperative framework (MACF) to assess the risk level of each allied organization’s IS and support the decision making of proactive security treatment in a distributed environment. In MACF, each analysis agent corresponding to an organization’s IS encapsulates a Bayesian network (BN) supporting the flexible information sharing with other analysis agents. Moreover, for an organization’s IS, the encapsulated BN is utilized to model its security environment and dynamically predict its security risk level, by which the control agent can choose an optimal action among alternatives to protect the information resources proactively.

Keywords: information systems security; information sharing; multi-agent; Bayesian networks

1. Introduction

Organizations’ heavy reliance on information systems (IS)requires them to manage the security issues associated with those systems. Nowadays, risks related to information systems security (ISS) are a major challenge for many organizations, since these risks mayhave dire consequences, including corporate liability, loss of credibility, and monetary damage (Cavusoglu, Cavusoglu, and Raghunathan 2004). Ensuring ISS has become one of the top managerial priorities in many organizations.

The management of ISSrisk is distributed across the allied organizations and requires a great deal of collaborative activity (Bulgurcu et al. 2010).For example, to detect the risk of network-based distributed attacks, cooperation among the allied enterprises is imperative in a supply chain environment. Thus, the development of models for information sharing among the inter-connected IS becomes very important for ISS management. Furthermore, in the scenarios of ISS, the form of sharing information includes not only the hard findings, i.e. the observations, but also the soft findings, i.e. the beliefs or the probability distributions (Gal-Or and Ghose 2009). But, in existing literature, there are few researches taking the information sharing into account in the scenario of ISS management. The models, supposed by Spafford (2000) and Gal-Or (2009), can support the sharing of filtered raw data and binary decisions (e.g., yes/no) among the inter-connected IS, while they are not capable of sharing the security risk beliefs. This limitation often influences their reliability of results.

In this article, we propose a multi-agent based cooperative framework (MACF), in which each component corresponding to one organization’s IS is able to process its own data and to integrate local findings with the findings from other components. More specifically, each analysis agent in MACF encapsulates a Bayesian network supporting the sharing in the form of

both the soft findings and the hard findings with other analysis agents. According to an allied organization’s risk level yielded by the analysis agent, the control agent is capable to choose an optimal security action that minimizes the expected loss among alternatives.

2. Literature review

In recent years, an emerging research stream, utilizing multi-agent technology, attempts to address the ISS issues under distributed environment. Among these researches, the approach proposed by Boudaoud et al. (2000) provides a flexible integration of a multi-agent system in a classical networked environment to enhance its protection level against inherent attacks. Besides Boudaoud‘s approach, Helmer et al. (2003) designed and implemented an intrusion detection system prototype that involves lightweight mobile agents. The agents in the system travel between monitored systems in a network of distributed systems, obtain information from data cleaning agents, classify and correlate information, and report the information to a user interface and database via mediators. More recently, adopting the adaptive agent model, Xiao (2009) put forward a security-aware model-driven mechanism by using an extension of the role-based access control model. The major contribution from the approach is a method for building adaptive and secure multi-agent system, following model-driven architecture.

Although these previous studies are highly informative and provide the groundwork for the field of ISS risk management, little attention has been devoted to the security information sharing under distributed environment. Few researches (Spafford and Zamboni, 2000; Gal-Or and Ghose, 2009) achieve the information sharing among the inter-connected IS through the sharing of the hard findings (i.e. the observations), but they are not adequate for supporting the sharing of the soft findings (i.e. the beliefs or the probability distributions). Therefore, our study mainly focuses on addressing the issue that how an allied organization can share the security information in the form of the soft findings as well as the hard findings with other allied members and effectively support the decision making for security practitioners to protect the information resources ina distributed environment.

3. Multi-agent based cooperative framework

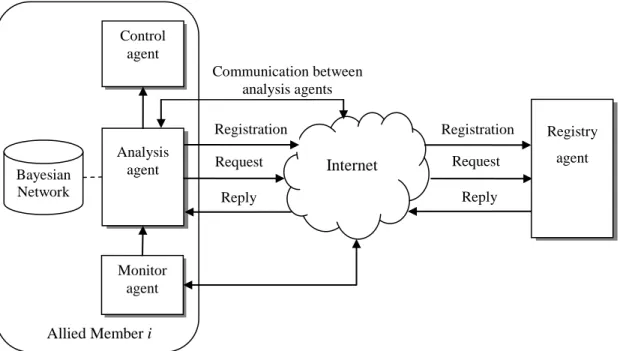

Basically, MACFis made up of someinter-connectedIS, which are called as “allied members’’. Foreach allied member,there are three kinds of agents:monitor agent, analysis agent and control agent. Suppose that there are nallied members and one registry agent. Then Fig. 1 demonstrates the MACF architecture, in which the interactions among the analysis agent and the registry agent of MACF are shown. Specifically, the agent actions and their corresponding messages are given in Table 1.

Fig. 1.MACF architecture (1 ≤ 𝑖 ≤ 𝑛).

Table 1. The agent actions and their corresponding messages. Message Message content Agent action

Registration message (from analysis agent to registry agent)

the registering agent’s agent-id; IP address;list of

published variables (output variables) and their possible states;digital signature and certificate

Each analysis agent must register with the registry agent. The registry agent issues an acknowledgment message upon successfully entering the new agent in its database.

Search request (from analysis agent to registry agent)

the requester’s agent-id; IP address; the required input variables

Each analysis agent has a set of input variables. To find agents capable of providing required input data, the analysis agent sends a search request to the registry agent.The message is digitally signed by the requester. Registry agent’s

reply

(from analysis agent to registry agent)

the requested variable name; the agent-id of the agent publishing the variable; its IP address and status

Upon receiving a search request, the registry agent verifies that the request is legitimate before searching its database to determine which agents can supply the requested variables and the status of these agents.

Internet Registration Request Reply Registry agent Analysis agent Registration Request Reply Communication between analysis agents Bayesian Network Control agent Monitor agent Allied Member i

Belief subscription request

(between analysis agents)

the requester’s agent-id; requester’s IP address; requested input variable name; the duration ofsubscription time; the desired time interval between subsequent updates;the request-id; the timestamp of the request

Upon receiving the list of agents capable of providing the required input from the registry, the subscribing agent sends requests directly to these agents.The message is digitally signed by the requester.

Belief-update message

(between analysis agents)

the request-id, the sender’s id, the probability distribution of the requested variable

Upon receiving a belief subscription request the publishing agent sends regular updates within the agreed intervals and duration of the subscription. The message is digitally signed by the publisher.

The functionsof each agent are described as follows:

(1) Monitor agent: The monitor agent performs either online or offline processing of log data, communicates with the application systems, and monitors IS resources. The IS profile and deviations generated by the monitor agent can be utilized by the analysis agent as the new evidences (facts and beliefs derived from observations) to update its encapsulated BN.

(2) Analysis agent: The analysis agent encapsulates a BNwhich is used to estimate the probability of each risk level of an allied member based on the operation of belief updating.The nodes of the BN are variablesthat describethe security environment of an allied member. In MACF, the variable can be divided intoinput variable, output variable, and local variable. An analysis agent,to obtain more security information associated with its input variables, can subscribeto the output variables publishedby other analysis agents providing the beliefs of their output variables as the new evidences. Therefore, once the new evidence is obtained through the monitor agents, the analysis agent is able to makeits encapsulated BN modify its own beliefs in real time and import or export beliefs from or to other encapsulated BNs.

(3) Control agent: The control agent belonging to one allied member chooses the action that minimizes the expected loss.Suppose that the control agent has m possible security actions and there are six risk levels (from l0 to l5) for each allied member. Then the

expected loss of each action is defined as follows:

5 = 0 =

, , =1, , 0 , 5 i i j j j E lo s s a lo s s a l P l i m j (1)whereloss(ai, lj) is the loss function of the ith action with respect to lj risk level; P (lj) is

the probability of the allied member that suffers the lj risk level. According to Eq. (1),

the control agent select the action, Min (Eloss (ai)), with the minimum expected loss to

protect its information resources.

(4) Registry agent: The registry agent maintains information about the published variables for each analysis agent. It is required that all analysis agents of MACF must register with the registry agent. The registry agent also maintains the location and current status of all theregistered agents. Agent status is a combination of two parameters alive and

reachable. The status of a communication link between any two agents is determined by attempting to achieve a reliable communication between them.

4. Conclusions

In future research, the proposed framework will be applied to a real life supply chain environment, in which there aresix allied members with inter-connected information systems,to illustratehow our model can be employed to manage security risks in distributed information systems.

Acknowledgements

The research was supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars of China (No.70925005) and the General Program of the National Science Foundation of China (No.71271149, No.71101103, No.61074152, and No.71001076).

Reference

Boudaoud, K., Labiod, H., Boutaba, R., Guessoum, Z. 2000. Network security management with intelligent agents”, IEEE Security Management (I), pp. 579–592.

Bulgurcu, B., Cavusoglu, H., Benbasat, I. 2010. “Information Security Policy Compliance: An Empirical Study of Rationality-Based Beliefs and Information Security Awareness”, MIS Quarterly 34(3), pp. 523-548.

Cavusoglu, H., Cavusoglu, H., and Raghunathan, S. 2004. “Economics of IT Security Management: Four Improvements to Current Security Practices”, Communications of the Association for Information Systems (14), pp. 65-75.

Gal-Or, E., Ghose, A. 2009.“The economic incentives for sharing security information”, Information Systems Research 16(2),pp. 186–208.

Helmer, G., Wong, J. S. K., Honavar, V., Miller, L., Wang, Y. 2003.“Lightweight agents for intrusion detection”, Journal of Systems and Software 67(2), pp. 109–122.

Spafford, E. H., Zamboni, D. 2000. “Intrusion detection using autonomous agents”, Computer Networks, 34(4),pp. 547-570.

Xiao, L. 2009. “An adaptive security model using agent-oriented MDA”, Information and Software Technology, 51 (5), pp. 933-955.

Towards a Multi-level Framework to Analyze Mobile Payment Platforms

Avinash Gannamaneni

ESSEC Business School, France; University of Mannheim, Germany

avinash.gannamaneni@gmail.com

Jan Ondrus

ESSEC Business School, France ondrus@essec.edu

Abstract:

Despite highly optimistic expectations over the past decade, mobile payments are yet to take off successfully. Repeated failures show that mobile payment platforms are complex to launch. We propose a multi-level framework for analyzing the success and failure factors mobile payment platforms. We use a longitudinal case of mobile payments in South Korea to illustrate the framework. Our results show that three consecutive failures could be explained by essential conditions that were not fulfilled at different levels of the framework. The current attempt displays better potential at each level. Ultimately, the outcome of this fourth attempt is likely to be more positive than for the other previous ones.

Key Words: Mobile payments, multi-sided platforms, multi-level analysis 1. Introduction

Because of the centricity of mobile phones in our lives, the idea of paying for goods and services using mobile phones emerged. The motivation behind mobile payments is to converge the two most indispensable items we carry everyday: our mobile phone and our wallet. Theconcept of mobile payment was received enthusiastically by the corporate world. Over the years, numerous attempts of launching mobile payment services were made by different actors including mobile network operators (MNOs) and financial institutions. In early 2000s, a few optimistic analysts and researchers joined the bandwagon by declaring that mobile payments could be the next killer application in mobile commerce (Rosingh et al., 2001; Zheng and Chen, 2003). However, at the same time, others already started to discuss the challenges for mobile payments to become reality (van der Heijden, 2002; Wrona et al., 2001). The number of early initiatives that failed raised concerns. The last decade of trials and pilots confirmed the difficulties of successfully launching commercial implementations of mobile payments. Academics from different disciplines have been conducting research on various mobile payment issues for the last decade.Despite a number of such studies, this emerging phenomenon still raised numerous questions. The complexity of the questions calls for multi-perspective analyses (Ondrus et al., 2005). Unfortunately, explaining one dimension or level at a time only offers a partial understanding on what the challenges are. Few studies have looked at mobile payments from a more holistic point of view while most of them have focused on only one specific aspect. For example, some researchers tackled the economic (Au and Kauffman, 2008) and strategic (Dahlberg et al., 2008) aspects. In this paper, we propose the use of a holistic multi-level framework to better understand the factors that lead to success or failure. We use a longitudinal case study from South Korea to illustrate how platforms could evolve over time and succeed.

2. Multi-level Framework

Mobile payment platforms are considered to be multi-sided as they bring together more than one group of users of the platform (sides): consumers and merchants. Moreover the platform is created through the collaboration of multiple interdependent actors hailing from different industries. Depending on the type of solution involved, mobile payments call for the involvement

of mobile network operators (MNOs), banks, financial institutions, payment networks, payment service providers, technology providers, mobile handset manufacturers, payment terminal manufacturers and other third parties.

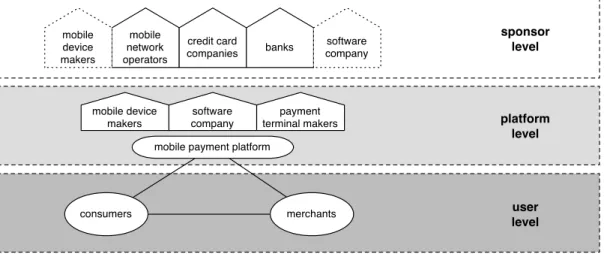

In order to classify the actors of the mobile payment ecosystem, we adopt a multi-level classification adapted from Eisenmannet. al. (2009). We partition the mobile payment platform into three distinct levels: i) sponsor level, ii) platform level, iii) user level. The sponsor level encompasses the roles and dynamics involving platform sponsorssuch as MNOs and financial institutions. The platform level includes the different points of contact of the users with the platform including the technological solution itself. Theuser level is concerned with the two groups of users of the platform: consumers and merchants. Figure 1 summarizes the different actors who could be involved in mobile payment platforms at each of these three levels. We will use this multi-level framework below to analyze a case of mobile payments.

Figure 1: Mobile payments as multi-sided platforms 3. Mobile Payment Case: Moneta

We studied the case of Moneta, a mobile proximity payment solution launched by SK Telecom in South Korea in 2002. Data was collected through interviews with executives from SK Telecom involved in the strategic decision making process behind Moneta. This was coupled with archival data including internal corporate documents, consulting reports and press articles. SKT is persistent with mobile payments. During the last decade, they invested heavily in three successive attempts (2002-2003-2006/7)under the brand name of Moneta. A fourth attempt is on-going.

3.1. Attempt 1 (Feb 2002-2003)

Early 2000s, mobile handsets in South Korea were CDMA-based. No SIM card was required for this technology. In its first attempt, Moneta involved specially designed mobile phones with a full size smartcard reader along with a Moneta credit card. The Moneta card was co-branded by Visa and issued by five domestic credit card companies and banks. Merchants were equipped with a card reader which could read Moneta cards. In order to make a purchase, consumers had to carry both the phone and the card. About 300,000 handsets were sold and 1 million plastic cards were issued. Unfortunately, the users who bought the compatible handsets rarely used the mobile payment service, which made this attempt fail.

Table 1. Multi-level analysis of Attempt 1

Level Analysis

compatible with existing the existing credit card system. Financial institutions did not share the same goals with SKT and perceived Moneta to be a threat to their traditional business. SKT was forced to manufacture their own card.

Platform Multiple proprietary mobile payment solutions were being offered by other players (K-merce by

rival MNO KTF, ZOOP by a start-up Harex). It meant that merchants had to install multiple dongles at their point of sale (POS). It became a significant setback to merchants in terms of costs. Both consumers and merchants were wary of adopting any of these proprietary solutions before a winner would emerge as the “de facto” standard nationwide.

User Users had to invest significantly to join Moneta (i.e., consumers: buying an appropriate handset;

merchants: installing dongles at payment terminals). In addition, consumers had to carry both their card and mobile handset to make a purchase. Hence there were no added benefits for the users to switch to mobile payments at this stage because of the lack of convenience.

3.2. Attempt 2 (Nov 2003-2005)

In November 2003, SKT introduceda SIM slot for financial chip on their CDMA phones. Six major credit card companies participated in this project. Consumers had to purchase these specially designed phones to be able to use Moneta’s services at affiliated stores equipped with Moneta. Merchants had to attach a proprietary dongle supplied by SKT to their existing POS terminal to be able to read Moneta chips. Over the course of this attempt, 400,000 merchants were equipped with the dongle. SKT tried to push the technology to consumers by making most of their handsets compatible with Moneta. By 2005, SKT sold more than 4.9 million Moneta enabled handsets. However, only 300,000 Moneta chips were issued to consumers who registered for the service. This attempt failed as only 21% of these registered users actually made a purchase using their handsets.

Table 2. Multi-level analysis of Attempt 2

Level Analysis

Sponsor To convince financial institutions to join Moneta, SKT offered them the possibility to

manufacture their own SIM sized chips. Therefore, financial institutions would not lose ownership of their customers. Although major credit card companies joined the platform, they did not promote it actively to their customers.

Platform No change from Attempt 1.

User Despite the perfect fusion of the phone and the credit card chip, users still did not perceive any

added value in using Moneta over existing credit cards. Moreover users still had to invest in appropriate hardware to be able to join the platform (i.e., consumers had to choose phones compatible with Moneta). In addition, the solution was inconvenient for consumers who use multiple credit cards as they had to change the “SIM” chip to use another card.

3.3. Attempt 3 (2006-2007)

Starting in 2006, Visa and Mastercard launched PayWave and Paypass proximity payment platforms based on Near Field Communication (NFC). The two platforms are compatible with both contactless cards as well as mobile payments. The result was a more standardized payment ecosystem in South Korea, where each MNO previously had its own proprietary mobile payment solution. After the mobile telecommunication networks evolved from CDMA to WCDMA in 2006, SKT supplied multi-functional SIMs which could store credit card data. Consumers could download multiple credit cards as well as other applications over the air onto their SIMs. In May 2007, SKT formed an alliance with Visa and started issuing SIM cards with a contactless payment feature. Initially, there was resistance from banks and financial institutions to offer their credit card applications over the air. However, in April 2008, SKT formed another alliance with

Shinhan bank, one of the largest banks in South Korea in order to jointly offer and market Moneta. This attempt raked in 2.6 million subscribers. Despite impressive initial figures, the usage of Moneta’s services was too low and the service eventually failed.

Table 3. Multi-level analysis of Attempt 3

Level Analysis

Sponsor SKT issued its own SIM cards. As a result, financial institutions were again afraid of losing

ownership of their customers. SKT had difficulties convincing all major institutions to join the platform. Moreover, SKT and financial institutions could not agree on revenue sharing. SKT wanted to take 1% of the total 2.5% transaction fees while the financial institutions did not want to give away anything to SKT. Furthermore, there was a complete lack of respect between the MNOs and the financial institutions which manifested in the form of various public bickerings.

Platform NFC emerged as the standard and all the rival proprietary solutions became interoperable with

each other. Merchants no longer needed to install any additional dongles. Consumers had NFC equipped handsets when they upgraded their devices as most of the third generation phones were enabled with NFC.

User All technology issues were solved as many consumers had NFC-enabled handsets. Merchants

automatically received NFC-compatible payment terminals during upgrades. Moneta offered various additional applications, including the extremely popular T-Money (for public transport) and some loyalty schemes. Overall, Moneta offered an additional value over existing payment schemes.

3.4. Post-Moneta: Hana SK Card

In 2010, SKT secured a 49% stake in Hana card, a top-three Korean credit card, and rebranded it as Hana SK card. SKT was able to attract 500,000 subscribers for the Hana SK card’s mobile wallet within a year of its launch (i.e., touted as the biggest figure for mobile wallets in the world). As of January 2013, SKT seems to be leading the mobile wallet race in South Korea with a combined annual growth rate of 661.7% since it was launched. This figure points towards an optimistic future for mobile payments in South Korea with a potential for mass adoption.

Table 4. Multi-level Analysis of Hana SK card

Level Analysis

Sponsor Since both MNO and financial institution are now owned by the same entity (SKT), the problems

related to effective coordination between platform sponsors are solved.

Platform Solved in Attempt 3. User Solved in Attempt 3.

4. Discussion

After analyzing the different attempts of Moneta through the use of a multi-level framework, we uncovered a number of factors responsible for the success or failure of mobile payment platforms. Firstly, at the sponsor level, there is a need for effective cooperation between MNOs and financial institutions for mobile payments to succeed. This must be achieved through sharing the same goals, agreeing on value sharing, and respecting each other. Secondly, at the platform level, all competing rival platforms must reach a consensus on an industry wide standard. Failure to do so would result in multiple proprietary solutions and it is likely that most of them would fail, especially in a fragmented market with no clear dominant MNO or financial institution. Finally, at the user level mobile payments must offer a significant value addition over existing payment schemes to entice users to join the platform. Merely merging phone and credit card is not sufficient to succeed as we have learnt from the case of Moneta.

multi-level framework to analyze the success and failure factors of multi-sided platforms, especially mobile payment platforms. Multi-sided platforms are complex by nature. Looking at one dimension at a time does not provide enough depth to explain success or failure of these platforms in a convincing manner. Second, we provide better explanations and justifications why Moneta kept failing in South Korea over the years. We hope that the insights presented in this paper could help practitioners to better design and manage multi-sided platforms. Special efforts must be made to satisfy factors at every level in order to increase their likelihood of success. In a further research, we aim at testing this framework on more cases/platforms in different contexts in order to validate its relevance in better understanding multi-sided platform design. We expect to extract more success and failure factors from the cases at each level. As a result, we could provide a list of success factors that need to be carefully examined during the design of any multi-sided platform.

5. References

Au, Y.A., Kauffman, R.J., 2008. The economics of mobile payments: Understanding stakeholder issues for an emerging financial technology application. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 7, 141–164.

Collins, C., Smith, K., 2006. Knowledge exchange and combination: the role of human resource practices in the performance of high-technology firms. Academy of Management Journal, 49(3) 544–560.

Dahlberg, T., Huurros, M., Ainamo, A., 2008. Lost Opportunity–Why Has Dominant Design Failed to Emerge for the Mobile Payment Services Market in Finland? Proceedings of the 41st Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

Eisenmann, T.R., Parker, G., Van Alstyne, M., 2009. Opening Platforms: How, When and Why?, in: Gawer, A. (Ed.), Platforms, Markets and Innovation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Ondrus, J., Camponovo, G., Pigneur, Y., 2005. A Proposal for a Multi-Perspective Analysis of the Mobile Payments Environment.The Fourth International Conference on Mobile Business (ICMB).

Ondrus, J., Lyytinen, K., Pigneur, Y. “Why Mobile Payments Fail? Towards a Dynamic and Multi-perspective Explanation“, 42th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS’09), IEEE Computer Society, 5-8 Jan 2009, Hawaii, USA

Rosingh, W., Seale, A., Osborn, D., 2001. Why Banks and Telecoms Must Merge to Surge [WWW Document]. strategy+business. URL http://www.strategy-business.com/article/17163?gko=4cda6 (accessed 6.23.13).

van der Heijden, H., 2002. Factors Affecting the Successful Introduction of Mobile Payment Systems, in:.Presented at the Proceedings of the 15th Bled eCommerce Conference, Bled, Slovenia, June 17-79.

Wrona, K., Schuba, M., Zavagli, G., 2001.Mobile Payments — State of the Art and Open Problems, in: Link.Springer.com, Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, Berlin, Heidelberg, 88–100. Zheng, X., Chen, D., 2003.Study of Mobile Payments System. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Electronic Commerce (CEC), Newport Beach, CA, USA, June 24-27.

Linking IT-Enabled Collaboration and Performance in the SME Context: The

Role of Responsiveness Capabilities

Hsin-Lu Chang hlchang@nccu.edu.tw

National Chengchi University, Taiwan

Daniel Yen Shueh daniel76308@gmail.com National Chengchi University, Taiwan Kai Wang kwang@nuk.edu.tw National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan Abstract

The service economy has been expanding recently, with small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) playing an important role. Previous research has shown that responsiveness is one of the most important strategic capabilities for SMEs to enhance their performance. How to define responsiveness and how to develop it in the SME context, however, are seldom discussed. A review of the literature leads us to propose the three dimensions of responsiveness in the SME context, which are market sensing, customer linking, and promptness. In addition, we propose that IT-enabled collaboration would facilitate this capability. We develop a research framework to examine the relationshipsamong IT-enabled collaboration, responsiveness, and organizational performance. To verify our research framework, a case study deployed in the Mt. Pillow Leisure Agricultural Area in Yilan County, Taiwan will be carried out. This paper is a work-in-progress and the aim is to contribute to the literature by defining responsiveness capabilities in the SME context and providing a framework for examining the relationships between IT-enabled collaboration, responsiveness capabilities, and organizational performance. The results of this study not only help SMEs in developing their responsiveness capabilities but also guide them to retain competitive advantage in the service economy.

Keywords: SMEs, IT-Enabled Collaboration, responsiveness capabilities, service performance, leisure agriculture.

1. Introduction

Responsiveness is one of the most important strategic capabilities that should be considered for enhancing the performance of service organizations [39, 43]. It contributes to organizations’ capability to deal with changes in customer demands [33, 44] and enhances organizational performance [38]. Customers are becoming more sophisticated in their needs and are increasingly demanding a higher standard of service. Therefore, when considering levels of performance as part of setting customer service objectives, service providers must take responsiveness into account as an important capability [29].

Responsiveness is critical for SMEs to remain competitive and sustain high performance. A primary task for resource-limited SMEs in emerging economies has been to develop low-cost and easily implemented measures to improve their sustainability and to increase the chances of success when facing rapid and often unforeseen changes in the external environments.

One strategic response to increasing uncertainty is to establish collaboration between SMEs using information technology (IT) [3, 12, 34]. A well-developed capability to create and sustain fruitful collaborations gives organizations a significant competitive edge [31]. Through IT-enabled collaboration, SMEs can become more responsive by searching and collecting information quickly and efficiently from their partners and customers, thus improving their sustainability [21, 41, 45].

both SME partners and customers in enhancing SMEs’ responsiveness to improve their performance. The current study aims to investigate the relationships between IT-enabled collaboration, responsiveness, and organizational performance. This study proposes that the performance of SMEs could be improved through IT-enabled collaboration, with the relationship between these two constructs mediated by responsiveness. This study aims to answer the following questions: (1)Why is responsiveness so important for SMEs? (2)How will IT-enabled collaboration enhance SMEs’ responsiveness? (3)How does responsiveness relate to organizational performance?

2. Conceptual Background and Hypotheses Development

Responsiveness involves three capabilities. Market-sensing capability is a process for learning about present and prospective market environments. Market-sensing can be divided into three processes: sensing activities, sense-making activities, and reflection [4, 5]. Sensing activities include the acquisition of information on consumers, competitors, and other channel members. Sense-making activities involve the interpretation of gathered information based on past experiences and knowledge. Reflection means the utilization of the gathered and interpreted information in decision-making.Customer-linking capabilityrefers to the ability to develop and manage close customer relationships and is among the most valuable capabilities of any organization [4].An organization’s customer-linking capability creates a potential competitive advantage in business [30]. Well-managed customer relationship creates a great opportunity to increase customer value and provides a way to systematically attract, acquire, and retain customers [19].Given the importance of promptness, many definitions have emerged [9, 24, 32, 33]. Among all these definitions, Kidd has provided the most comprehensive one: A prompt organization is a fast-moving, adaptable, and robust business. Such a business is founded on processes and structures that not onlysupport speed, adaptation, and robustness buy alsofacilitate a coordinated business capable of achieving competitive performance in a highly dynamic and unpredictable environment to which the current practices are poorly suited.

Responsiveness is especially important for SMEs to maintain customer loyalty because SMEs face an endless stream of competition from larger companies that have the richer resources to be “on call” for their clients constantly. Such competition demonstrates the importance of fast response to and efficient communication withthe market, partners, and customers for SMEs to achieve business success.

Collaboration is an effective way for SMEs to achieve better performance and long-term survival [3, 12, 34]. Collaboration can be conducted either horizontally with SME partners or vertically with customers, using IT to share information more efficiently and effectively to improve coordination and collaboration activities [2, 22].

Appropriate use of information is fundamental to the ability of sensing market requirements because if an organization does not have adequate and accessible resources and information, it stands at a competitive disadvantage [11]. Haeckel and Nolan [10] stressed that information technology is critical to managing conditions that are too turbulent to make sense of. IT-enabled collaboration thus allows resource-limited SMEs to acquire and share information efficiently and effectively, thus strengthening their ability to sense the market. Therefore, we hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1-a: IT-enabled collaboration with SME partners has a positive impact on market-sensing capability.

Although customer relationships are viewed as an intangible resource that may be relatively rare and difficult for others to replicate [13, 37], the capability of SMEs to acquire and manage customer information is limited due to their smaller scale. By coordinating information and activities with strategic partners, a SME can develop more ways to attract customers, and

become more responsive to customer requests and build greater customer loyalty and better customer relations [30, 40]. Therefore, we predict that customer-linking capability can be improved by collaboration through information technology:

Hypothesis 1-b: IT-enabled collaboration with SME partners has a positive impact on customer-linking capability.

SMEs usually lack promptness because they lack resources to cultivate such capability. To enhance promptness, it is important to strengthen communication and collaboration and improve decision-making processes [25]. SMEs can acquire necessary resources and capabilities by forming alliances [6]. IšoraItė[36]indicated that organizations involved in alliances are better able to utilize resources to improve their speed to the market and the speed in serving customers. Information technology makes such coordination feasible [18]. Paulraj and Chen [28] stated that IT-enabled collaboration increases information processing speed by providing an intermediary platform for partners to share knowledge, provide timely information, and transcend each firm’s boundaries. We thus hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1-c: IT-enabled collaboration with SME partners has a positive impact on promptness.

Unlike large organizations, SMEs do not have the resources to engage in formal market research [17]. For SMEs to sense the market precisely and adapt to it, they must collaborate with their customers to collect a significant amount of data and analyze it. This analysis will provide them with better insight into customer requirements and expectations, ultimately resulting in services that are more suited to the market [16]. With the help of information technology, SMEs are able to gather, store, access, and analyze customer data to effectively make strategic business decisions [42]. Therefore, we hypothesize that IT-enabled collaboration with SME customers provides an environment for SME organizations to collect and analyze market data from customers and thus enhances the capability of organizations to sense the market.

Hypothesis 2-a: IT-enabled collaboration with SME customers has a positive impact on market-sensing capability.

One usual but crucial reason for an organization to conduct customer-linking activities iscustomers’ low satisfaction with services and products [1, 8]. However, linking to customers is a time-consuming and resource-demanding process for SMEs. It is therefore essential for SMEs to enhance their customer-linking capability by collaborating with customers through a friendly, accessible, and directly interactive channel so that customers feel comfortable to give feedback [16]. Füller et al. [7]indicated that organizations can be able to form new channels to collaborate with customers, effectively share knowledge, and manage relationshipswith the help of IT. As a result, IT-enabled collaboration with customers may reduce the distance between resource-limited SMEs and customers. Thus, we develop the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2-b: IT-enabled collaboration with SME customers has a positive impact on customer-linking capability.

Whereas large organizations can employ a number of people to take care of their customers immediately, resource-limited SMEs usually struggle to respond quickly to the demands of their customers. For SMEs, a fast and efficient communication tool to learn about customers is vital if they are to achieve business success. Through collaboration with customers, SMEs are better able to learn about their customers in multiple ways by shortening the response time needed. Moreover, IT enables organizations to reduce the time required to share information and reduce response time to unforeseen events, thereby enhancing promptness [15, 25]. Therefore, we hypothesize that SMEs gain promptness through IT-enabled collaboration with customers.

Hypothesis 2-c: IT-enabled collaboration with SME customers has a positive impact on promptness.

segments and the segments where the rivals’ offerings may not be fulfilling customers’ needs [35]. These underserved and unsatisfied segments are good targets for organizations seeking new customers. Hult[14] and Morgan et al. [26] suggested that market-sensing capability provides market insights that enable organizations to reduce their costs through effective use of resources by better matching the organization’s resource acquisitions and deployments with customer and prospect opportunities. By doing so, SMEs are better able to forecast the value of different resources accurately, thus enabling them to manage resources in a better way to achieve higher performance [20]. Therefore, we propose hypothesis 3-a as follows:

Hypothesis 3-a: Market-sensing capability has a positive impact on SME performance.

SMEs may sometimes spend their limited resources and time on other tasks at the cost of customer satisfaction. This trade-off may lead SMEs to lose business to their larger competitors. Managing relationships with customers is therefore critical.

In the current study, customer-linking capability is defined as an organization’s ability to manage the relationship with its customers through direct contact. Direct customer contacts shorten service cycles and lower service costs. Nielsen [27] and Hooley et al. [13]pointed out that customer-linking capability enables the development and maintenance of strong customer relations and ultimately improves customer satisfaction and loyalty. As a result, we expect the following hypothesis to hold:

Hypothesis 3-b: Customer-linking capability has a positive impact on SME performance.

Due to the smaller scale and limited funds, SMEs need to determine the most efficient as well as effective market strategies for improving their performance. A firm’s promptness represents the strength of the interface between the organization and the market [23]. Organizations that are prompt in response to customer requirements demonstrate operational flexibility, which is able to eliminate waste in their operations, better direct their interactions with their customers to improve customer retention, and in general, reduce the costs incurred in servicing the customer base. We therefore argue that promptness can yield better SME performance in two ways, namely gaining profit by quickly adapting to market changes and reducing cost by eliminating waste from operations. Thus, we posit:

Hypothesis 3-c: Promptness has a positive impact on SME performance.

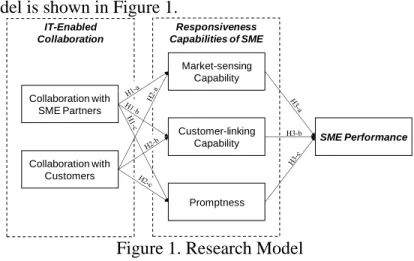

The research model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Research Model

3. Research Methodology

Leisure agriculture is a new trend of agricultural operations that combines local industry, cultural characteristics, leisure, natural ecology, and accommodations. With its unique geography and diverse cultural and natural resources, Taiwan possesses significant potential to develop leisure agriculture. However, SMEs involved in leisure agriculture are seldom able to collaborate to enhance their competitiveness. Operating independently, they continue to suffer from low

Customer-linking Capability Market-sensing Capability Promptness Collaboration with Customers Collaboration with SME Partners SME Performance Responsiveness Capabilities of SME IT-Enabled Collaboration H3-b

productivity, lack of innovation, and slow growth due to the lack of necessary resources to manage and fulfill customer needs efficiently.

Based on the discussion above, we believe that IT-enabled collaboration will enable SMEs to enhance their responsiveness capabilities to achieve a higher level of service performance.To better examine the relationships between IT-enabled collaboration, responsiveness capabilities, and performance, we plan to adopt the case study approach andperform in-depth analysis.

For the purpose of the current study, we selected eight SMEs in the Mt. Pillow Leisure Agriculture Area, Yilan County, Taiwan. These SMEs include farms, orchards, gardens, restaurants, natural landscapes, natural ecological areas, and accommodations. Due to space limitation, the detailed descroption of case companies is available on request from the first author.

Because the SMEs in the Mt. Pillow Leisure Agriculture Area do not yet have a unified IT-enabled collaborative platform, we extend the targeted platform to include tools that can provide a channel for SMEs to obtain and share information, directly communicate and interact, and engage in collaborative projects with customers and other SME partners. Therefore, the IT-enabled collaborative platforms we take into consideration include, among others, blogs, guestbooks, and Facebook. We will conduct two interviews for each case, each lasting approximately one to two hours. All interviews will be tape recorded and transcribed before the data analysis. To enhance the validity of answers, summaries of the major finding in each interview will be verified by the interviewees after each interview session. Moreover, to ensure the construct validity, internal validity, external validity, and reliability of the case study, Yin’s[85] case study tactics will befollowed.

4. Expected Contribution

The service economy has grown significantly in the last decade, and SMEs are an important part contributing to the growth in this sector. To serve customers in the turbulent environment, SMEs must enhance their responsiveness to retain long-term competitiveness.

Few published articles have addressed the issue of how to enhance SMEs’ responsiveness through IT-enabled collaboration. The current study aims to contribute to the literature by defining responsiveness capabilities in the SME context and providing a framework for examining the relationships between IT-enabled collaboration, responsiveness capabilities, and organizational performance. We believe that the results will not only help SMEs to develop their responsiveness capabilities but also offer SMEs a guide to retaining their competitive advantage in the service economy through IT-enabled collaboration.

References

[1] K. Atuahene-Gima, “The Influence of New Product Factors on Export Propensity and Performance: An Empirical Analysis”, Journal of International Marketing, 3(2), 1995, 11-28.

[2] A. Barua, P. Konana, A.B.Whinston, and F. Yin, “An Empirical Investigation of Net-Enabled Business Value”, MIS Quarterly, 28(4), 2004, 585-620.

[3] P. Bastos, “Inter-Firm Collaboration and Learning: The Case of the Japanese Automobile Industry”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, (4), 2001, 423-441.

[4] G.S. Day, “The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations”, Journal of Marketing, 58(4), 1994, 37-52. [5] G.S. Day, “Managing the Market Learning Process”, Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 17(4), 2002, 240-252.

[6] Z. Fernández and M.J. Nieto, “Internationalization Strategy of Small and Medium-Sized Family Businesses: Some Influential Factors”, Family Business Review, 18(1), 2005, 77-89.

[7] J. Füller, H.Mühlbacher, K.Matzler, and G.Jawecki,“Consumer Empowerment through Internet-Based Co-Creation”, Journal of Management Information Systems, 26(3), 2009, 71-102.

[8] J. Goldenberg, D.R. Lehmann, andD. Mazursky,“The Idea Itself and the Circumstances of its Emergence as Predictors of New Product Success”, Management Science, 47(1), 2001, 23-26.

[9] A. Gunasekaran,“Agile Manufacturing: AFramework for Research and Development”, International Journal of Production Economics, 62(1/2), 1999, 87-105.

[10] S.H. Haeckel, and R.L. Nolan,“Managing by Wire”, Harvard Business Review, 5(71), 1993, 122-132.

[11] P. Herbig and A.T. Shao,“American Keiretsu: Fad or Future”, Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing, 1(4), 1993, 3-30.

[12] M. Hitt, D. Ahlstrom, M. Dain, E.Levitas, andL. Svobodina,“The Institutional Effects on Strategic Alliance Partner Selection in Transition Economies: China vs. Russia”, Organization Science, 15(2), 2004, 173-185.

[13] G.J. Hooley, G.E.Greenley, J.W.Cadogan, andJ. Fahy,“The Performance Impact of Marketing Resources,” Journal of Business Research, 58(1), 2005, 18-27.

[14] G.T. Hult,“Managing the International Strategic Sourcing Process as a Market-Driven Organizational Learning System”, Decision Sciences, 29(1), 1998, 193-216.

[15] H. Katayama andD. Bennett,“Agility, Adaptability and Leanness: A Comparison of Concepts and a Study of Practice”, International Journal of Production Economics, 60-61(20), 1999, 43-51.

[16] C. Kausch,ARisk-Benefit Perspective on Early Customer Integration,Springer, Berlin, 2007.

[17] H.T. Keh, T.T.M. Nguyen, and H.P. Ng,“The Effects of Entrepreneurial Orientation and Marketing Information on the Performance of SMEs”, Journal of Business Venturing, 22(4), 2007, 592-611.

[18] K. Kumar and H.G.V.Dissel,“Sustainable Collaboration: Managing Conflict and Cooperation in Interorganizational Systems”, MIS Quarterly, 20(3), 1996, 279-300.

[19] Y.C. Lin andH.Y. Su,“Strategic Analysis of Customer Relationship Management—AField Study on Hotel Enterprises”, Total Quality Management, 14(6), 2003, 715-731.

[20] R. Makadok,“Toward a Synthesis of the Resource-Based and Dynamic-Capability Views of Rent Creation”, Strategic Management Journal, 22(5), 2001, 387-401.

[21] E. Malecki and D. Tootle,“The Role of Networks in Small-Firm Competitiveness”, International Journal Technology Management, 11(1/2), 1996, 43-57.

[22] C. Martinez-Fernandez,Networks for Regional Development: Case Studies from Australia and Spain, PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2001.

[23] R. Mason-Jones and D.R.Towill,“Total Cycle Time Compression and the Agile Supply Chain”, International Journal of Production Economics, 62, 1999, 61-73.

[24] R.E. McGaughey,“Internet Technology: Contribution to Agility in the Twenty-First Century”, International Journal of Agile Management Systems, 1(1), 1999, 7-13.

[25] A.E.C. Mondragon, A.C. Lyons, andD.F. Kehoe,“Assessing the Value of Information Systems in Supporting Agility in High-Tech Manufacturing Enterprises”, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 24(12), 2004, 1219-1246.

[26] N.A. Morgan, D.W.Vorhies, andC. Mason,“Market Orientation, Marketing Capabilities, and Firm Performance”, Emerald Management Reviews, 30(8), 2009, 909-920.

[27] J.F. Nielsen,“Internet Technology and Customer Linking in Nordic Banking”, International Journal of Service Industry Management, 13(5), 2002, 475-495.

[28] A. Paulraj andI.J. Chen,“Strategic Buyer-Supplier Relationships, Information Technology and External Logistics Integration”, Journal of Supply Chain Management, 43(2), 2007, 2-14.

[29] A. Payne,The Essence of Service Marketing, Prentice-Hall, UK, 1995.

[30] A. Rapp, K.J.Trainor, andR. Agnihotri,“Performance Implications of Customer-Linking Capabilities: Examining the Complementary Role of Customer Orientation and CRM Technology”, Journal of Business Research, 63(11), 2010, 1229-1236.

[31] M. Rosabeth,“Collaborative Advantage: The Art of Alliances”, Harvard Business Review, 72(4), 1994, 96-108. [32] V. Sambamurthy, A. Bharadwaj, andV. Grover,“Shaping Agility through Digital Options: Reconceptualizing the Role of Information Technology in Contemporary Firms”, MIS Quarterly, 27(3), 2003, 237-263.

[33] H. Sharifi andZ. Zhang,“A Methodology for Achieving Agility in Manufacturing Organizations: An Intruduction”, International Journal of Production Economics, 62(1/2), 1999, 7-22.

[34] E. Sivadas and F.R. Dwyer,“An Examination of Organizational Factors Influencing New Product Success in Internal and Alliance-based Processes”, Journal of Marketing, 64(1), 2000, 31-49.

[35] S.F. Slater and J.C.Narver,“Intelligence Generation and Superior Customer Value”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 28(1), 2000, 120-127.

[36] M. IšoraItė, “Importance of Strategic Alliances in Company’s Activity”, Intellectual Economics, 1(5), 2009, 39-46.

[37] R.K. Srivastava, T.A.Shervani, and L. Fahey,“Market-Based Assets and Shareholder Value: A Framework for Analysis”,The Journal of Marketing, 62(1), 1998, 2-18.

[38] G. Stalk,“Time: The Next Source of Competitive Advantage”, Harvard Business Review, 66(4), 1988, 41-51. [39] G. Stalk and T.Hout,Competing against Time, Free Press, New York, NY, 1990.

[40] J.R. Stock,“Managing Computer, Communication and Information Technology Strategically: Opportunities and Challenges for Warehousing”,The Logistics and Transportation Review, 26(2), 1990, 133-148.

[41] L. Suarez-Villa,“The Structures of Cooperation: Downscaling, Outsourcing, and the Networked Alliances”, Small Business Economics, 10(1), 1998, 5-16.

[42] P. Swafford, S. Ghosh, and N. Murthy,“A Framework for Assessing Value Chain Agility”, International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 26(2), 2006, 170-188.

[43] R. Teare,“Hospitality Operations: Patterns in Management, Service Improvement and Business Performance”, International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 8(7), 1996, 63-74.

[44] A.S. Tsui,“Reputational Effectiveness: Toward a Mutual Responsiveness Framework”,in L.L. Cummings and B.M. Staw (Eds.), Research in Organizational Behavior, 16, 1994, 257-307.

[45] P. Varadarajan and M. Cunningham,“Strategic Alliances: A Synthesis of Conceptual Foundations”, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23(4), 1995, 282-296.

21

Fostering a Seamless Customer Experience in Cross-Channel Electronic

Commerce

Jaeki Song

Texas Tech University

jaeki.song@ttu.edu

Miri Kim

Sogang University

mirikim@sogang.ac.kr

Jeff Baker

American Univ. of Sharjah

jbaker@aus.edu

Junghwan Kim

Texas Tech University

Jun.kim@ttu.edu

ABSTRACT

Many companies have launched mobile channels as an extension of existing websites in order to enhance communication with customers. Despite employing multiple technologies, retailers have difficulty integrating web and mobile channels to deliver a consistent and seamless customer experience. Our initial empirical results suggest that customers’ perceived quality of channel integration is determined by the functional configuration of the mobile applications, by the perceived similarity across channels, and by the perceived quality of the website.

Keywords: e-commerce; m-commerce; mobile applications; cross-channel commerce; seamless

customer experience

1. INTRODUCTION

Mobile commerce is rapidly becoming a popular and valuable retail channel, with both consumers as well as producers realizing numerous benefits (Oracle, 2011). Retailers are finding that a mobile sales channel can function as an extension of their traditional web channel, creating additional value for stakeholders. More than 75% of consumers use two or more channels to research and complete transactions when they purchase a product or service, suggesting that “retailers need not necessarily serve up the identical experience in each channel, but rather they can optimize and connect channel interactions to deliver consistent user experiences” (Oracle 2011, p.4). Consequently, many retailers are investing in mobile services as a valuable channel for e-commerce, and plan their strategies to include websites, mobile sites, and mobile applications(Adobe 2010; Lamont 2012).

At the same that retailers are learning to add mobile channels to their existing web channels, it has been noted that many companies find it difficult to deliver a consistent experience across the various electronic channels customers use (Fodor, 2012). For instance,57% of mobile web users would not recommend a business with a bad mobile site, and 40% of users have turned to a competitor’s site after a bad mobile experience (Compuware 2011). A bad experience on a mobile site or application also leaves consumers less likely to utilize or recommend a related website. Consistency in functionality, information, and visualization is important to customers. The research question we therefore seek to investigate is, “What are the factors that influence

22

customers’ perceptions regarding consistency across retailers’ various electronic channels?”

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT A Seamless Customer Experience: Perceived Quality of Channel Integration

Cross-channel commerce is a growing trend in retailing (Neilson, et al., 2006; Kwon and Lennon, 2009; Madaleno, et al, 2007). Customers are increasingly using multiple channels, including computers and mobile devices, to obtain information about products and services, or to complete a transaction (Oracle, 2011). Given the growing reality of cross-channel electronic commerce, researchers have begun to investigate the effects of channel integration on a variety of outcomes such as customer satisfaction and retention, as well as its effects on customer relationship management (CRM) (Bendoly, et. al., 2005; Yang, et al., 2013). Researchers have shown that firms with well-integrated channels are more successful than single-channel firms or than those with multiple, but poorly-integrated channels (Sousa et al. 2006). Channel integration can enrich customers’ experiences with retailers, and can strengthen customers’ overall perceptions regarding the image of a retailer (Kwon and Lennon, 2009). The development of multiple well-integrated electronic channels is thus a goal and a challenge for retailers.

Retailers realize that customer experience occurs during all moments of contact with the firm through multiple channel settings (Rosenbloom 2007; Sousa et al. 2006). Offering a seamless and consistent experience across channels is important because each interaction with a customer plays an essential role in enhancing (or degrading) the quality of the customer relationship (Madaleno et al. 2007; Payne et al. 2004). A seamless customer experience provides value not only to customers as they gain information and make transactions, but also to firms as they cultivate relationships with customers and potential customers. Therefore, this study aims to provide an understanding of how retailers offer a seamless customer experience across channels. Our research model shows how we plan to investigate customers’ perceptions of consistency and channel integration (see Figure 1). We suggest that customers’ perceived quality of channel integration is determined by the functional configuration of the mobile applications, by the perceived similarity across channels, and by the perceived website quality. We now describe in greater detail each of the relationships depicted in our model.

23

The Influence of Website Quality

Companies both large and small have online, virtual means for reaching customers (Rosenbloom 2007). Website quality has been identified as a key factor that influences the success of an e-commerce website, with website quality being defined as “the extent to which a website facilitate the efficient and effective shopping, purchasing, and delivery products and services” (Gounaris et al., 2005, p. 673) We suggest in this study that quality is important not only in traditional websites, but in all electronic channels. Customers’ experiences with existing channels necessarily influence how they cognitively or affectively perceive new channels (Zeithmal 2002). Therefore, we hypothesize:

H1. In cross-channel electronic commerce, website quality is positively associated with the perceived quality of channel integration.

Mobile applications lead to new opportunities and challenges for retailers. The limitations of mobile devices, including screen size, processing power, and limited functionality relative to laptop or desktop computers, are critical challenges for retailers. At the same time, portability, ubiquity, and familiarity with the device present several advantages (Buellingen et al. 2004; Steele 2003). With these opportunities and challenges in mind, we focus on two additional factors that may influence the perceived quality of channel integration: the functional configuration of the mobile application and similarity of the mobile application to other channels.

Functional Configuration of the Mobile Application

The functional configuration of the mobile application includes two elements as potential indicators: functional extensibility and functional complementarity. Functional extensibility refers to the extent to which a mobile channel extends the web channel’s functionality by adding new functions (Yang et al. forthcoming). That is, functional extensibility implies that mobile channels deliver different functions for achieving similar goals, which can be utilized in the website, with new or mobile-customized technologies. For example, the application for Amazon.com uses location management technology to determine where a shipper should deliver an item – this is an example of functional extensibility. Mobile applications are designed to provide many of the core functions used in websites in addition to different mobile networking technologies (Varshney et al. 2002). These technologies contribute to a function of the mobile application and result in better customer service by creating synergies (Rosenbloom 2007). Hence, regarding functional extensibility, we hypothesize:

H2a.In cross-channel electronic commerce, the functional extensibility of the mobile application is positively associated with perceived quality of channel integration.

Functional complementarity refers to the extent to which the basic functionality and essential

features of a mobile application support or complement the e-commerce activities customers can perform on a website. Providing complementary functions for customers to complete their intended activities is important to ensure superior customer experience (Mithas et al. 2007). For instance, a UPS customer can search for a particular shipping product (such as “Next-Day Air”), schedule a pick-up, and complete payment all online. Then, the customer can use the package tracking feature on the UPS mobile application. The use of this feature on the mobile application

24

complements the customer’s activities on the traditional website. Similarly, online ticketing, for air travel can be completed on a website, with the complementary activity of checking a flight’s arrival time performed via a mobile application(Buellingen et al. 2004). By providing customers with the features on a mobile application that complement those of the website, service providers enhance customer experience. Therefore, we posit that

H2b.In cross-channel electronic commerce, the functional complementarity of the mobile application is positively associated with the perceived quality of channel integration.

Perceived Similarity of the Mobile Application to Other Channels

Perceived similarity captures an individual’s beliefs about how similar elements are to each other

(Brown and Inouye, 1978). In this study, the similarity we are investigating is the similarity between e-commerce sales channels, particularly between mobile applications and websites. Perceived similarity has two indicators: information consistency and visual consistency.

Information consistency refers to the consistency between information exchanged with the

customer through different channels, including both outgoing and incoming information (Sousa et al. 2006). If inconsistency or conflict of the information across channels exists, this inconsistency will confuse the customer and may reduce the likelihood of purchase. Firms must provide quality across all channels, ensuring a coherent message with all information conveyed by different channels (Payne et al. 2004). Thus, we hypothesize:

H3a. In cross-channel electronic commerce, the information consistency of the mobile application is positively associated with the perceived quality of channel integration.

Visual consistency refers to the consistency of the relevant and comparable visual attributes,

including, visual aesthetics, image, font, order, and complexity, in mobile applications associated with retailers’ websites. The similarity of a mobile application to an e-commerce website may increase a customer’s uniform and comprehensive experience by enhancing the integrated interactions across channels (Ganesh 2004; Sousa et al. 2006). From a design process perspective, providing the user with consistency of the visual design is the most important factor in mobile application development (Buellingen et al. 2004; Kangas et al. 2005). When the design of an application is simple and operated by in a manner similar to a familiar website, the customer feels that the application is alsofamiliar, and is easy to use. Therefore, we hypothesize:

H3b.In cross-channel electronic commerce, visual consistency of the mobile application is positively associated with perceived quality of channel integration.

3. RESEARCH DESIGN Instrument Development

For the survey instrument, we identified existing measures that had been repeatedly tested and that possess strong content validity. For example, perceived quality of channel integration is measured by a consistent impression between mobile application and website, integration of the mobile application and website, and combination of mobile application and website as service across channels (adapted for our research domain from Payne et al., 2004 and Sousa et al., 2006)