Sleep Quality and Morningness-Eveningness on Shift Nurses

Min-Huey Chung1, 2; Fu-Mei Chang, RN, PhD3; Cheryl C. H. Yang, PhD4;Terry B. J.

Kuo, MD, PhD4; Nanly Hsu, RN, PhD3

1

Institute of Medical Sciences, Tzu Chi University, Hualien; 2School of Nursing, National Defense Medical Center, Taipei, Taiwan. 3 School of nursing, Tzu Chi University, Hualien; 4 Institute of Brain Science, National Yang-Ming University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Running Title: morningness-eveningness on sleep quality –Chung et al. Keywrods: shift, nurse, morningness-eveingness, sleep

Address correspondence to: Nanly Hsu, School of Nursing, Tzu Chi University, No. 701, Chung

Yang Road, Section 3, Hualien 97004, Taiwan; Tel: 886 3 8565301 (ext.7034); Fax: 886 3 8580639;

ABSTRACT

Aim and objective. The aim of the study was to analyze, while controlling for identified covariates, the effects of morningness-eveningness on global sleep quality

and components of sleep quality for shift nurses.

Background. Shift nurses had greater difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, thus resulting in higher rates of retiring from hospital. Existing research has addressed the

effects of manpower demand and personal preferences on shift assignment; however,

the concept of endogenous rhythms is considered rarely.

Methods. This analysis included 137 nurses between the ages of 21 and 47. Nurses completed the Horne and Ostberg questionnaire to assess morningness-eveningness

and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) questionnaire to measure self-reported

sleep quality over the last month. The 18-point Chinese version had a Cronbach’s

reliability coefficient of 0.79 overall and 0.86, respectively. This study analyzed

correlates of sleep quality by comparing the groups with better or worse sleep quality

according to the median of PSQI. Univariate and multivariate analyses were used for

the risk factors of worse sleep quality.

Results. The result showed that the strongest predictor of sleep quality was morningness-eveningness not the shift schedule or shift pattern for nurses under

controlling the variable of age. Greater age and longer years employed in nursing

was properly controlled; evening types working on shifting jobs had higher risk of

poor sleep quality compared to morning types.

Conclusion. Morningness-eveningness was the strongest predictor of sleep quality under controlling the variable of age in shift nurses.

Implications for clinical practice. Our results suggested that determining if nurses were attributed to morning or evening types is an important sleep issue before

deciding the shift assignment.

Introduction

Nurses work under a shift work system (day shift, evening shift and night shift) in

response to patient needs. The shift work system disturbs the natural human circadian

rhythm and causes lack of sleep (Knauth et al. 1980), which directly or indirectly

lowers work efficiency. According to the stressor model by Olsson et al.(1990)

stressors brought by the shift system are occupational stressors, personal factors, and

non-occupational stressors. Occupational stressors included the shift system (speed

and hours) and workload. Personal factors consisted of sex, age, and circadian rhythm

types. Non-occupational stressors involved the level of stress in daily living. These

stressors cause tremendous pressure on shift workers and arouse physical and

psychological reaction; furthermore, they cause sleep disturbances and circadian

rhythms disorders. At last, the health of these workers is under duress and the vicious

cycle may cause nurses to quit their jobs. Therefore, it is necessary to continuously

study nurses’ work shift system.

The effect of shift work on worker health is determined by personal factors; for

instance, the individual biological clock and circardian rhythm. Brain resititution and

sleep are influenced by personal inner factors, such as age, circardian rhythm,

physical condition and flexible sleep habits. In other words, the shift worker tends to

work problems of pilots and indicated that age and circardian rhythm were the main

factors contributing to work shift assignment and fatigue. Age, circardian rhythm type

and sleep disturbance effectively influence work performance. The circardian rhythm

types could be categorized as Morning-types (M-types), Evening-types (E-types)and

in between the Intermediate type. The M-types get up early and sleep early, while the

E-types are active during the night and can not get up early.

Shift assignement is decided mainly by the manpower demands in hospital wards

and personal preferences; but the endogenous rhythm concept is not considered. Most

studies examined the effect of shift work on sleep (Coffey et al. 1988; Niedhammer et

al. 1994; Poissonnet & Veron 2000; Skipper et al. 1990) or focused on examining correlates of simulated shift work (Cajochen et al. 1995; Dijk et al. 1991; Finelli et al.

2000). Few studies focused on the effects of morningness-eveningness on sleep

quality, particularly in practical shiftwork nurses. We studied the sleep pattern of five

different work shifts, including day shift (07:30-15:30), evening shift (15:30-23:30),

night shift (23:30-07:30), day shift to evening shift or night shift (fast clockwise), and

night shift to day shift or evening shift (fast counter-clockwise). The aim of the study

was to analyze, while controlling for identified covariates, the effects of

morningness-eveningness on global sleep quality and components of sleep quality for

Method

The present analysis included 137 nurses between the ages of 21 and 58 enrolled in

the total. Seventy-four subjects were in their twenties, 42 subjects were in their thirties

and 21 subjects were between the ages of 40 and 58. All subjects were screened to be

clear of any personal history of psychiatric, neurological, sleep or medical disorders.

Subjects read and signed an informed consent that provided detailed information

about the nature, propose and risks of this study.

The personnel in each ward were informed about the study orally by the author at

three different personnel meetings. A contact person at each casualty department was

selected to answer any questions about the study. After the informed consent was

obtained from all women, the researcher would check the missing data to ask nurses

fill it again. The PSQI (Buysse et al. 1989) is a questionnaire that measures

self-reported sleep habits over the last month. It is a global measure with seven

components; perceived sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency,

sleep disturbance, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. The score for

each component ranges from 0 to 3, and the sum is a global score that ranges form 0

to 21. As those who took sleep medication were excluded, only six components were

used, with global scores form 0 to 18. Higher scores indicated poorer sleep quality.

of music on individual elements of sleep could be determined.

A score of 5 (indication poor sleep) yield a diagnostic sensitivity of 89.5% and a

specificity of 86.55, with an internal consistency of α =0.83, and test-retest reliability,

r=0.85(Buysse et al. 1989). The Chinese language of PSQI had α =0.72 and a split

half reliability of 0.84(Wang 1997). In this study, the 18-point Chinese version had a

Cronbach’s reliability coefficient of 0.79 overall and a split half reliability of 0.74 for

the six component scores. Using instrument translated into Chinese, several variables

were measured on their duty to determine whether they would confound the effects of

morningess-eveningness on sleep.

Participants were asked whether or not they had a bedtime routine, napped after

lunch, used herbal tea to sleep. Heart rate and blood pressure were measured by the

investigator in the first visit. Subjects completed the Horne and Ostberg (1976)

questionnaire in order to assess the morningness-eveningness. This questionnaire

establishes five behavioral categories (English version scoring): definitively morning

types (score=28-32), moderately morning types (score=23-27), neither types

(score=16-22), moderately evening types (score=11-15) and definitively evening

types (score=6-10). For the purpose of this study we reduced the categories from

five to three: morning type (score=23-32), neither type (score=16-22) and evening

For maximizing the statistical power, worse sleep quality was defined by being higher

than the median of PSQI (8). For basic comparisons, socio-demographic characteristics,

feature of nursing work nature (years of duty, shift schedule, and shifting pattern), blood

pressure, tea/coffee drinking habit and morningness-eveningness type were statistically

examined by using t-tests for continuous variables and Chi-square tests for categorical

variables. The major area of interest for worse sleep quality was the

morningness-eveningness type for nurses with shifting work hours. Other factors were

considered as potential confounders in the advanced statistical explorations in this study.

Afterwards, we utilized univariate logistic regressions to estimate the relative risk of each

variable on worse sleep quality. After that, potential confounders were involved in

constructing the final model of detecting the effect of morningness-eveningness type for

sleep quality among nurses. To explore which components would be sensitive to

individual morningness-eveningness types of the nurses, we performed linear regressions

by separating PSQI components to detect the effect of morningness-eveningness type for

each component. SPSS 12.0 for Windows was utilized to perform all the statistical

analyses and the significance level (P value) was set as 0.05.

Results

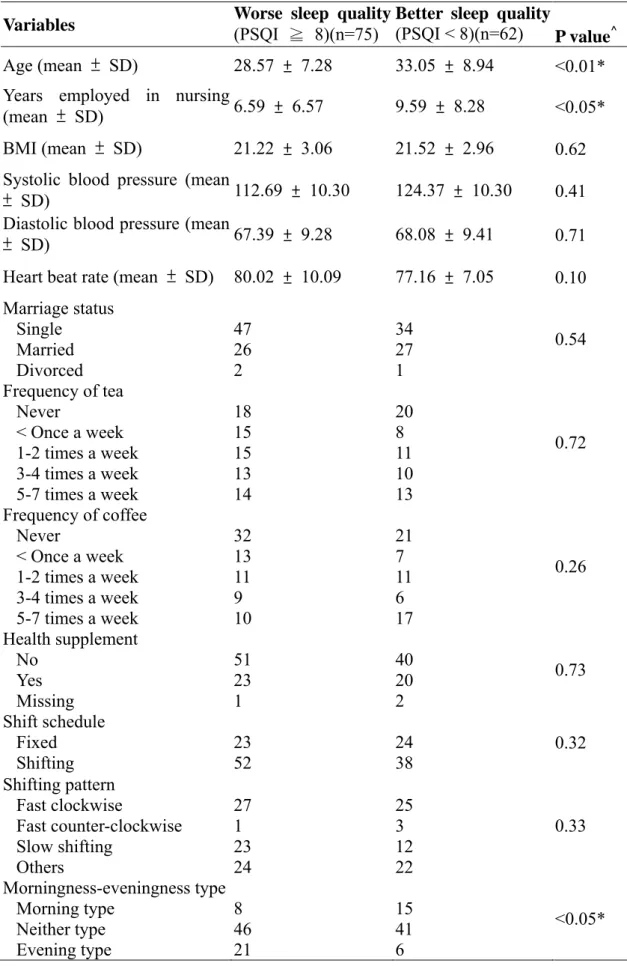

the results from comparing the baseline of two groups. Age, years of duty, and

morningness-eveningness types were significantly different between the groups with

and without worse sleep quality. Specifically, older nurses and longer employment

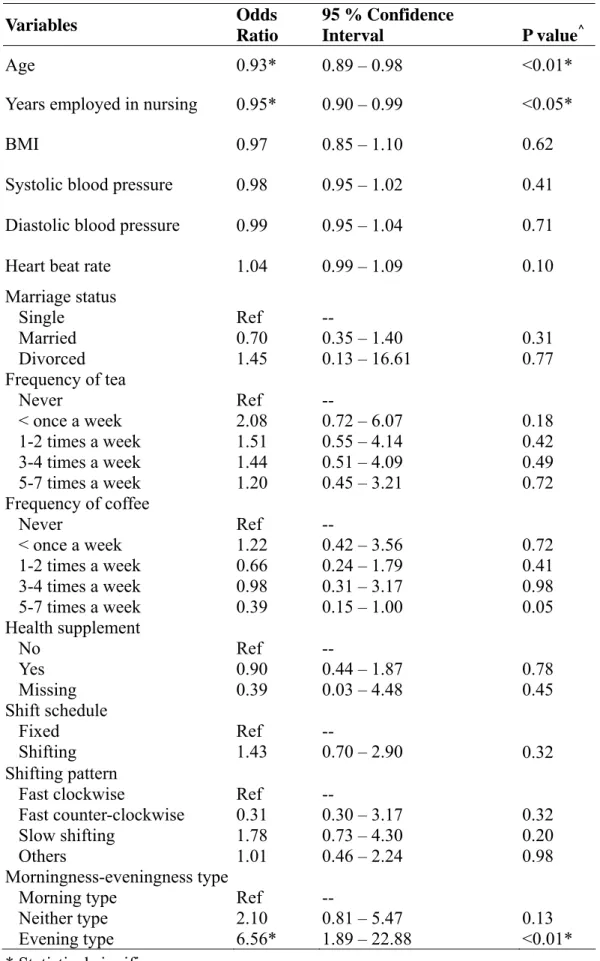

duration showed decreased risk for worse sleep quality (OR = 0.93, 95% CI:

0.89-0.98; OR = 0.95, 95% CI: 0.90-0.99, respectively). It was noteworthy that E-

types revealed a significantly increase risk of worse sleep quality (OR = 6.56, 95% CI:

1.89-22.88). None of the other risk factors showed a significant effect on sleep quality,

in terms of PSQI (Table 2). For precise estimation of the effects in our study

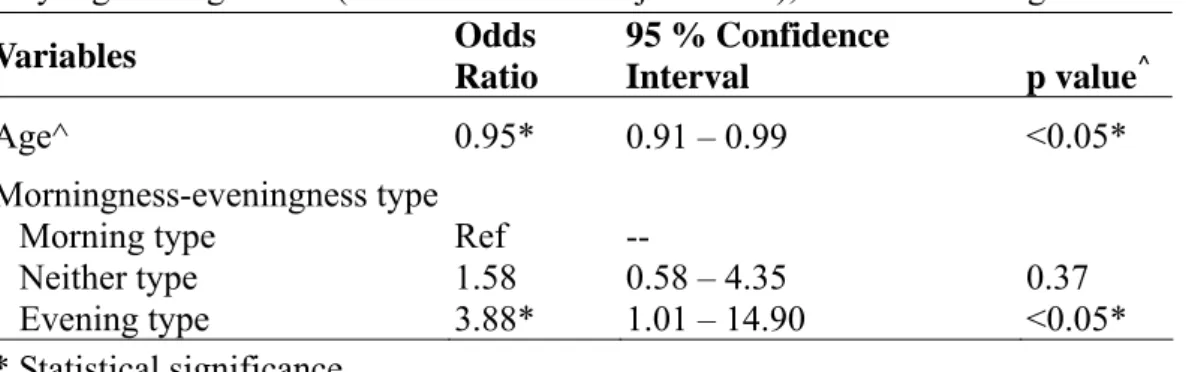

(morningness-eveningness type), confounding control was achieved for age and years

of duty. Because of the collinearity between age and years of duty, their 95% CIs were

widened and the statistical significance lost in multivariate analyses. Thus, in Table 3,

we decided to control the age as the only confounder and achieved the best relative

risk estimation for morningness-eveningness types (evening type OR = 3.88, 95% CI:

1.01-14.90, relative to morning type). Consequently, when age was properly

controlled, E-type nurses working on shifting jobs had a higher risk for poor sleep

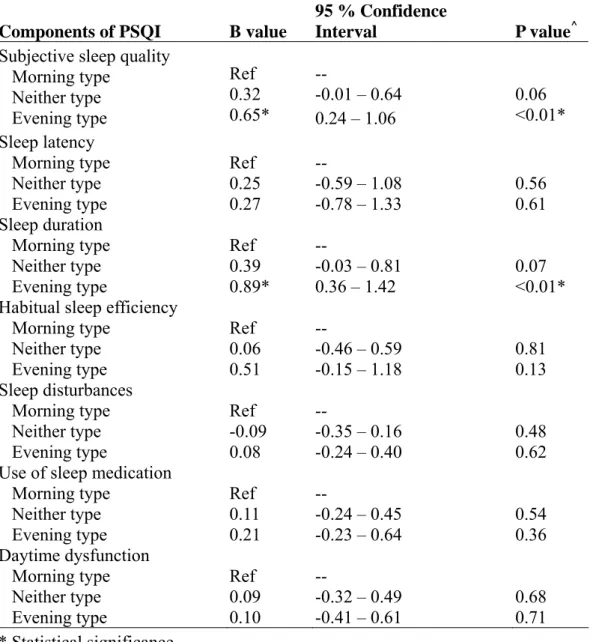

quality. To further explore the PSQI components, the scores of component 1

(subjective sleep quality) and Component 3 (sleep duration) were significantly raised

for E-type nurses. Namely, nurses with evening type had apparent poor subjective

in bed was significantly lower than the ones of morning type.

Discussion

This study was employed questionnaires to measure morningness-eveningness and

sleep quality of shift nurses. It was to analyze correlates of sleep quality by comparing

these groups with better or worse sleep quality according to the median of PSQI (8).

Univariate and multivariate analyses were used to identify the risk factors of worse

sleep quality. The result showed that the strongest predictor of sleep quality was the

subject’s natural morningness-eveningness sleep pattern not the shift schedule or shift

pattern. Although this result could not confirm the relationship of cause and effect in

sleep quality, we indicated that considering morningness-eveningness type of nurses

was an important issue for sleep quality in rotating shift nurses.

The study found a significant change in age and years of duty on sleep quality in

shift nurses (table 1). This result was consistent with previous studies(Carrier et al.

1997). After further analyzing the results, we found that older age and longer years of

duty decreased the risk of worse sleep quality. This result was not in line with that

increasing age associated with less time asleep or increased number of awakenings

during the sleep period(Carrier et al. 1997). However, this result was consistent with

According to Harma (1993) greater tolerance to shift work was related with more

control hours of work through individual choice with regard to shift system

acceptability. This study may imply that more experienced nurses could have greater

tolerance to shift work, which allows them sleep well.

M-types show a preference for waking at an early hour and experience alertness

early in the day. E-types show a preference for sleeping at latter hours and function

better in the afternoon and evening (Giannotti et al. 2002). Previous studies indicated

that E-types find adjustment to night shifts easier (Paine et al. 2006). Therefore, it is

better to understand the effect of morningness/eveingness on sleep quality for nurses

before knowing their acceptability and adjustment to shift work. This study surveyed

the relationship among morningness-eveningness type, shift pattern and sleep quality.

We differentiated the shift schedule by checking the nurse’s actual duty time to make

the shift pattern parameter more precise. This result showed that shift schedule or shift

pattern was not correlated with sleep quality. However, the sleep quality was

correlated with morningness-eveningness. This finding may hint nurses working at

night or arranging shift schedule should assess their endogenous type (morningness

and eveningness) at first. Whether shift work reflects morningness-eveingness sleep

habit or it influence shift work is interesting and warrants further exploration.

Especially, nurses with evening type reflected negative extremes on two areas:

subjective sleep quality and sleep duration; however, changes declined on the rest five

areas: sleep latency, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping

medication and daytime dysfunction. These findings may be explained as follows:

First, E-types tend to vary considerably their sleep/ waking time and sleep length

(Ishihara et al. 1992; Kerkhof 1985; Monk et al. 1994). They delayed their sleep wake

schedules more than morningness type. This study showed that E-types sleep from

1AM to 4 AM and wake up from 10AM to 2PM, while M-types sleep from 10 PM to

12 PM and wake up from 6AM to 8AM in the day shift and off duty time. We

confirmed that E-types had more changeable sleep-wake schedules than M-types.

Second, E-types were related with a greater need for sleep (Taillard et al. 1999). This

study indicated the sleep length of E-types around 5 hours to 8 hours in the day shift

and evening shift, but around 10 to 12 hours in their days off. E-types had more

irregular sleep-waking time, this situation resulted in a sleep debt during their day

shift and extended their sleep duration in their off time.

We analyzed correlates of sleep quality and tried to understand changes of

morningness-eveningness for shiftwork nurses as a reference. A longitudinal survey

would propose more efficient suggestions. We hope that shift problems of doctors and

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by Tri-service General Hospital Foundation in Taiwan

(Research Grant TSGH-C94-095).

References

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF, 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR & Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28, 193-213.

Cajochen C, Brunner DP, Krauchi K, Graw P & Wirz-Justice A (1995) Power density in theta/alpha frequencies of the waking EEG progressively increases during sustained wakefulness. Sleep 18, 890-894.

Carrier J, Monk TH, Buysse DJ & Kupfer DJ (1997) Sleep and

morningness-eveningness in the 'middle' years of life (20-59 y). J Sleep Res 6, 230-237.

Coffey LC, Skipper JK, Jr. & Jung FD (1988) Nurses and shift work: effects on job performance and job-related stress. J Adv Nurs 13, 245-254.

Dijk DJ, Brunner DP & Borbely AA (1991) EEG power density during recovery sleep in the morning. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 78, 203-214.

Finelli LA, Baumann H, Borbely AA & Achermann P (2000) Dual

electroencephalogram markers of human sleep homeostasis: correlation between theta activity in waking and slow-wave activity in sleep. Neuroscience 101, 523-529.

Gander PH, DE nguyen BE, Rosekind MR & connell LJ (1993) Age, circadian rhythms, and sleep loss in flight crews. Avitation, Space and Evironmental Medicine 64, 189-195.

Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Sebastiani T & Ottaviano S (2002) Circadian preference, sleep and daytime behaviour in adolescence. J Sleep Res 11, 191-199.

Harma M (1993) Individual differences in tolerance to shiftwork: a review. Ergonomics 36, 101-109.

Ishihara K, Miyake S, Miyasita A & Miyata Y (1992) Morningness-eveningness preference and sleep habits in Japanese office workers of different ages. Chronobiologia 19, 9-16.

review. Biol Psychol 20, 83-112.

Knauth P, Landau K, Droge C, Schwitteck M, Widynski M & Rutenfranz J (1980) Duration of sleep depending on the type of shift work. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 46, 167-177.

Monk TH, Petrie SR, Hayes AJ & Kupfer DJ (1994) Regularity of daily life in relation to personality, age, gender, sleep quality and circadian rhythms. J Sleep Res 3, 196-205.

Niedhammer I, Lert F & Marne MJ (1994) Effects of shift work on sleep among French nurses. A longitudinal study. J Occup Med 36, 667-674.

Olsson K, Kandolin I & Kauppinen-Toropainen K (1990) Stress and coping strategies of three-shift workers. Le Travail Humain 53, 213-226.

Paine SJ, Gander PH & Travier N (2006) The epidemiology of

morningness/eveningness: influence of age, gender, ethnicity, and

socioeconomic factors in adults (30-49 years). J Biol Rhythms 21, 68-76. Poissonnet CM & Veron M (2000) Health effects of work schedules in healthcare

professions. J Clin Nurs 9, 13-23.

Skipper JK, Jr., Jung FD & Coffey LC (1990) Nurses and shiftwork: effects on physical health and mental depression. J Adv Nurs 15, 835-842.

Taillard J, Philip P & Bioulac B (1999) Morningness/eveningness and the need for sleep. J Sleep Res 8, 291-295.

Wang YW (1997) Effect of Acupressure on the sleep disturbance of Taiwanese elderly. Unpublished doctoral dissertation Case Western Reserve University,

Table 1 Basic characteristics and comparisons of the groups with better or worse sleep quality by the median of PSQI (N= 137)

Variables Worse sleep quality(PSQI ≧ 8)(n=75) Better sleep quality (PSQI < 8)(n=62)

P value^ Age (mean ± SD) 28.57 ± 7.28 33.05 ± 8.94 <0.01* Years employed in nursing

(mean ± SD) 6.59 ± 6.57 9.59 ± 8.28 <0.05* BMI (mean ± SD) 21.22 ± 3.06 21.52 ± 2.96 0.62 Systolic blood pressure (mean

± SD) 112.69 ± 10.30 124.37 ± 10.30 0.41 Diastolic blood pressure (mean

± SD) 67.39 ± 9.28 68.08 ± 9.41 0.71

Heart beat rate (mean ± SD) 80.02 ± 10.09 77.16 ± 7.05 0.10 Marriage status Single Married Divorced 47 26 2 34 27 1 0.54 Frequency of tea Never < Once a week 1-2 times a week 3-4 times a week 5-7 times a week 18 15 15 13 14 20 8 11 10 13 0.72 Frequency of coffee Never < Once a week 1-2 times a week 3-4 times a week 5-7 times a week 32 13 11 9 10 21 7 11 6 17 0.26 Health supplement No Yes Missing 51 23 1 40 20 2 0.73 Shift schedule Fixed Shifting 23 52 24 38 0.32 Shifting pattern Fast clockwise Fast counter-clockwise Slow shifting Others 27 1 23 24 25 3 12 22 0.33 Morningness-eveningness type Morning type Neither type Evening type 8 46 21 15 41 6 <0.05*

variables

Table 2 Univariate analyses for the risk factors of worse sleep quality (PSQI ≧ 8) by logistic regressions (N= 137) Variables Odds Ratio 95 % Confidence Interval P value^ Age 0.93* 0.89 – 0.98 <0.01*

Years employed in nursing 0.95* 0.90 – 0.99 <0.05*

BMI 0.97 0.85 – 1.10 0.62

Systolic blood pressure 0.98 0.95 – 1.02 0.41 Diastolic blood pressure 0.99 0.95 – 1.04 0.71 Heart beat rate 1.04 0.99 – 1.09 0.10 Marriage status Single Married Divorced Ref 0.70 1.45 -- 0.35 – 1.40 0.13 – 16.61 0.31 0.77 Frequency of tea Never < once a week 1-2 times a week 3-4 times a week 5-7 times a week Ref 2.08 1.51 1.44 1.20 -- 0.72 – 6.07 0.55 – 4.14 0.51 – 4.09 0.45 – 3.21 0.18 0.42 0.49 0.72 Frequency of coffee Never < once a week 1-2 times a week 3-4 times a week 5-7 times a week Ref 1.22 0.66 0.98 0.39 -- 0.42 – 3.56 0.24 – 1.79 0.31 – 3.17 0.15 – 1.00 0.72 0.41 0.98 0.05 Health supplement No Yes Missing Ref 0.90 0.39 -- 0.44 – 1.87 0.03 – 4.48 0.78 0.45 Shift schedule Fixed Shifting Ref 1.43 -- 0.70 – 2.90 0.32 Shifting pattern Fast clockwise Fast counter-clockwise Slow shifting Others Ref 0.31 1.78 1.01 -- 0.30 – 3.17 0.73 – 4.30 0.46 – 2.24 0.32 0.20 0.98 Morningness-eveningness type Morning type Neither type Evening type Ref 2.10 6.56* -- 0.81 – 5.47 1.89 – 22.88 0.13 <0.01* * Statistical significance

Table 3 Multivariate analysis for the risk factors of worse sleep quality (PSQI ≧ 8) by logistic regression (Total number of subjects: 137), controlled for age

Variables Odds Ratio 95 % Confidence Interval p value^ Age^ 0.95* 0.91 – 0.99 <0.05* Morningness-eveningness type Morning type Neither type Evening type Ref 1.58 3.88* -- 0.58 – 4.35 1.01 – 14.90 0.37 <0.05* * Statistical significance

Table 4 The effect of morningness-eveningness type by each component of Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) with linear regressions, adjusted by age (N=137)

Components of PSQI B value

95 % Confidence

Interval P value^

Subjective sleep quality Morning type Neither type Evening type Ref 0.32 0.65* -- -0.01 – 0.64 0.24 – 1.06 0.06 <0.01* Sleep latency Morning type Neither type Evening type Ref 0.25 0.27 -- -0.59 – 1.08 -0.78 – 1.33 0.56 0.61 Sleep duration Morning type Neither type Evening type Ref 0.39 0.89* -- -0.03 – 0.81 0.36 – 1.42 0.07 <0.01* Habitual sleep efficiency

Morning type Neither type Evening type Ref 0.06 0.51 -- -0.46 – 0.59 -0.15 – 1.18 0.81 0.13 Sleep disturbances Morning type Neither type Evening type Ref -0.09 0.08 -- -0.35 – 0.16 -0.24 – 0.40 0.48 0.62 Use of sleep medication

Morning type Neither type Evening type Ref 0.11 0.21 -- -0.24 – 0.45 -0.23 – 0.64 0.54 0.36 Daytime dysfunction Morning type Neither type Evening type Ref 0.09 0.10 -- -0.32 – 0.49 -0.41 – 0.61 0.68 0.71 * Statistical significance