Comparing the Effects ofTwo Types of Drama Activities on Technology Students' English Leaming . 245

Comparing the Effects of Two Types of

Drama Activities on

.

Tech

n

ology

Students' English Learni11g

. :f*-

J}f

-:!to

-¥Jl

fJli;f4-~t*- ~J.t m

71'"$%,%

Abstract

This study reports the results of the comparison of two types of student drama activity applied to two English conversation classes in an university of technology in central Taiwan. They are: (a) staging a play With script created by students and edited by the teacher; (b) enacting a ready-made script. The study begins byexam ining at the beginning of the conversation course learners' initial level of oral English competence, and their initial perspectives towards English learning, it then applies the self-created script approach to the test-group and the ready-made script ap proach to the control- group during the one semester course. At the end of the course, it examines the differences in the teaching/learning effect of both groups of learners by comparing their current English performance and their current perspectives to wards English learning to see whether the drama activity is actually facilitating in English teaching/learning. Results reveal that the test-group's opinions differ signifi

cantly from the control-group's in the folloWing aspects: (a) the degree to which subjects' learning is positively influenced by teacher-student interaction; and (b) subjects' self-rated English listening- and speaking-abilities. In addition, the post

test reveals that the test-group outperforms the control-group. This study aims to provide English teachers-particularly in the field of general education-with some reference regarding the use of drama activities in enhancing students' learning effec tiveness.

Keywords: drama activity, self-created script, ready-made script

*~H~ §':tE~~

El EIJ&~*Arn&~mi}]

'fl'ME~§ 1W*JilI%iJ~§€i~~'IN:l:jtCP , J.;)t~.~AW;JF ElEIJ~IJ*AJiX~Umi}]:tE~~)(;t~:n[§jpJT~~Zl~j5iJ 0 *utf~B"J1J~t:

~~~M~~.~.m~~Zw~.~~m~~~~~~~N&A~~~~~ ~~~t:

'

f&1&~-*jtEjz.fjcp~~...t~~f.irn~~mi}]~Jiffi~~;r£i(t~t~;r£iW~%1J;r£I.)

Z*~ .t~~*a~ 0, M*~.~

, l:t~~;r£i~~

§ 1W~~~~U],&AtJ~~*~~~$'~OO.M~-rn~mi}]~~~.~M~~~~*o*utf~~ *ID'[~J.rJiffi

El

EIJ~IJ*Arn~u$i}]1&Z~.~;r£iW.,Jiffi;JF El EIJ&U*AJiX&IJmi}]1&Z

~%IJ;r£i~t~fT~1J[§j~~it:1fmr~:Z/f[QJ , E!D

: (-) ,

:3b5[U1t§!B~gffi~HitJ~A*~z~Wf~N& ( = ) ,~mlJ1t~ltW~~~B"J~gtJZEl!ltw1ti 0 Itt

5'} , 1&1JVJz~*~~.~;r£i~~%IJ;r£i~l]'11:~ 0 *~~~g~1;!:!;~~~WCP~g€i ~*I~1t~~~fflrn~~.m~Z~~'~~~*~Z*~~~o

In

t

rod

In I

ing wher 2000; J( Warden, of teachi 2002,Li

r

is highly been qUi1 tive spoo municati' only able found thr that deve Are enhancinl Wenger. J Duff, 198: 1987; W€ acteristic process, b pects of 1 facilitate~ (Maley 1]o

As MadHlComparing the EtTects oi'Two Types of Drama Activities on Technology Students' English Leam ing . 247

Introduction

In private technology colleges or universities, major difficulties teachers are fac ing when teaching English conversation are, among others, large classes (Altschuler.

2000; Jou and Kai, 1995; Ho, 2002; Hsu, 2001; Hudson 1994 ; Lin, 2003; Lin and Warden, 1998), limited time (Ho, 2002; Long and Porter, 1985: 208), limited amount of teaching equipment as well as students' low motivation to speak English (Ho, 2002, Lin 2002) . With learners of up to 60 in a two- or three-hour-a-week class, it is highly impossible to have good, indiVidual teacher-student interaction, and it has been quite unavoidable that students are being taught in predominantly non-interac tive spoon-fed settings. Students yearn to learn English in a more interactive or com municative way (Altschuler, 2000), they hope to be able to speak instead of being only able to read and write English (Lin, 1996: 118; Sy, 1995). As Jong (2001) has found through a survey, students at technology colleges throughout Taiwan believe that developing speaking ability is their greatest need.

A reView of the literature shows that drama actiVities contribute considerably to enhancing learners' communicative competence (see, for example, Ernst-SlaVit and Wenger, 1998; Griffee 1986; Holden,1982; Hsu,1975; LindsaY,1974; Maley and Duff, 1982; Moss, 1971; Schewe and Shaw, 1993; Somers. 2001; Stern, 1983; Via, 1987; Wessels, 1987). Drama actiVities' lively actions and highly cbntexualized char acteristics not only attract students' attention, give students great joy during the process, but also engage students in real dialogue and help students to explore as pects of real language use which generate meaningful communication and in turn facilitates language acquisition. While drama is beneficial for developing oral sJrJlls (Maley and Duff, 1982), it has been the author's observation that without careful planning as well as some techniques for dealing with large size class students, a drama actiVity may end up less fruitfully (Lin, 2003).

c

Do drama activities havp positive value or negative impact on the learners in an EFL setting like Taiwan') Vie may not have a definite and reliable answer until spe

cific empirical research has been undertaken. This study investigates the use and

('ffects of two types of drama activity in the conversation class and compares their

contribution, from students' perspective, to English learning. The following sections explore the benefits that drama activities bring to the classroom. Then, the respective procedures for the emfJloYiTlont are introduced, stUdents' responses to the survey com pared, and analyzed.

Literature Review

In the article "Experiential language learning: expanding student learning styles through drama" (1999), Luo suggests that motivation to take ariother English course is not related to learning styles, but significantly related to the learner's foreIgn lan guage performance. Luo's research results show that

"the performance of English short plays exactly fits the students With concrete expeJience oJientation and active expeJimentation ortentatlon in terms of their learning style. Moreover, the performance of plays was most likely to enhance the tendency to interactive learning, especially for those students With abstract conceptualization orientation." (p. 9)

According to Griffee (1986), "It is easier for us to acquire language when we have a context in which we can hear and understand'" Learning through action is a dynamic tool in the hands of a prepared teacher, and ... minidramas extend and amplify that dynamic '" (p. 23). The pedagOgical contributions of actions include many (p. 19), among others: actions focus students' attention on meaning'" ac tion aids memory" . finally, listening and acting corrects the situation where often students who can read, write, and even speak English are unable to understand nor mal spoken English (Palmer and Palmer 1925) .

Descr: come their Wu's (199l me tho dolo profound p gues that 11 environme glish as a: Brum learners, it act the dial prOvided s( creation an working tog Written crea easily. In hE mini - play iE speaking co builds a call talking to a outlining ani of English IE efited from

c

Researci

This st1 1. Wha' 2. Inw

3. Is StlComparing the E!Teets ofTwo Types ofDrama Activities on Technology Students' English Learning . 249

Described in nice detail by Shimizu (1993), Japanese learners are able to over come their existing barriers to communication by means of drama-based methods. In Wu's (1998: 19) discussion, Goalen's (1996) research regarding drama as teaching methodology is mentioned and commented on as having convinced people with its profound pedagOgical value through reliable quantitative study. Yan (1997: 119) ar gues that learners' low motivation is the main problem in Taiwan's English learning environment. Yan advocates making drama a part of curriculum when teaching En glish as a second language so as to enhance learners' motivation and learning effect.

Brumfit (1979) has emphasized that language teaching is not packaged for learners, it is made by them. According to Lindsay (1974), students will be keener to act the dialogues out if they can manage in pairs to write them-the teacher having provided some models. Maley and Duff (1982) have stated that the combination of creation and imagination relies on the working together on the students' side ; by working together, students learn to create their own parts. According to Raz (1969), written creative work by advanced pupils helps them to absorb structures and idioms easily. In her presentation of a case study, Ho (2002) has reported that self-created mini-play is conSidered to be helpful for language recall, for creativity and in boosting speaking confidence. She has stated that the process of creating a mini-play together builds a collaborative learning environment in which students learn from observing or talking to one another (p. 338) . In the process of discussing characters and plot, outlining and drafting their own script, rehearsing different roles and actions, a group of English learners are described by Ernst-Slavit and Wenger (1998) to have ben efited from creative drama.

Research Questions

This study attempted to answer the following questions:

1. Wbat general effects do the two types of drama activity have on students? 2. In what areas does a self-created SCript benefit language acquisition?

learning consistent with actual learning outcome?

Study Design

To investigate the difference between two types of drama activities, namely: (a) staging a play with script created by students and edited by the teacher; and (b) enacting a ready-made script, two conversation classes in an university of technology in Taiwan were chosen for this preliminary study' The study began by examining at the beginning of the conversation course learners' initial level of oral English compe tence, and their initial perspectives towards English learning. For these purposes, an oral interview and a pre-drama survey were conducted to all the .students. In the survey, questions about students' current perspectives about English learning were included. The survey was handed out for students to complete in class, and the data were collected immediately. The differences in the perception of teaching/ learning effect by both groups of subjects were examined by comparing their perspectives about English learning at this stage.

The study then applied the self-created script approach to the test-group and the ready-made script approach to the control-group during the one semester course. At the end of the course, it examined the differences in the teaching/learning effect of both groups of learners by comparing their current English performance and their current perspectives towards English learning to see whether the drama activity is actually facilitating in English teaching/learning. For these purposes, the final on stage performance of both of thp. groups was observed and compared, and a post drama survey was handed out at the end of the drama performance for students to complete in class. The data were gathered immediately' This execution was intended to facilitate the author in comparing the range of difference in students' perspectives about English learning at this stage.

The Course, Subjects, and Classroom Activi

t

ies

were sal gram at the semi study. T were mt senior h universi1 the stud ThE generall~ bus that hours, th they hac

Comparing the EtTecb ofTwo Types of Drama Activities on Technology Students' English Learning . 251

The two classes (test-group and control-group) that participated in the study

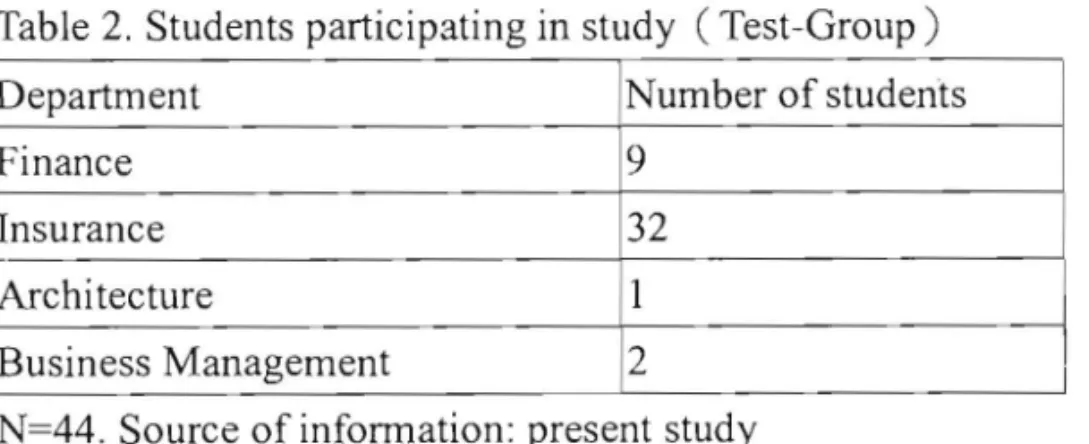

were sophomore students of English conversation course in a four-year college pro gram at Chaoyang University of Technology. Each class met two hours a week over the semester starting in September, 2001. A total of 93 students participated in the study. The demographic data revealed that about three-fifths (60.6%) of the group were male. Students had studied the language for an average of 6 years in junior and senior high schooL All in all, the participants seemed to be a fairly typical group of university students beginning their second year of language study. The distribution of the students participating in the study is shown in Tables 1 and 2:

Table 1. Students participating in study (Control-Group)

Department N umber of students

Film 7

Information Management 21

Accounting 8

Environmental Protection 13 N=49. Source of information: present study

Table 2. Students participating in study (Test-Group)

Department Number of students

Finance 9

Insurance 32

Architecture 1

Business Management 2

N=44. Source of information: present study

The text for both of the classes was New Interchange 2A The text matched

generally their English level of competence and was an integrated, multi-skills sylla

bus that links topics, communicative functions, and grammar. During normal class hours, the test-group students were able to ask the teacher for help for a.ny difficulties they had encountered in their process of script writing. And when there were no

Pre- (

problems left to be solved, they were given-similar as the control-group-instruction of the textbook During the semester, two written examinations related to the introduced materials of the textbook were administered to ensure subjects minimal learning of basic structures.

Procedure

BeSides regular learning activities, two types of drama activities were applied to the two groups of learners in academic year 2001-2002. They are: (a) staging a play With script created by students - at the beginning of the course, the test-group stu

..

dents were given the opportunity to discuss what topiC they preferred for the drama activity. As guidance, they were first provided With some options, e.g., in the restaurant, in the airport, in the department store or in the hotel, etc. Students were free to generate some other ideas, if they Wished. Any topiC would fit the purpose as long as

it was a real world situation or context. After consensus was reached, students were

asked to begin thinking about the topiC and to gather related information outside of class whenever possible. The draft of students' self-created script was required to be

edited by the teacher; (b) enacting a ready-made sCript-students were reqUired to

act out a ready-made play out of their own choice. Both types of the drama actiVity

(a) were performed on a group basis which comprised four to five members;

(b) were about ten minutes in length; (c) served as a final oral test.

The evaluation criteria of the activities were announced at the beginning of the

course so as to be assisting students in the direction of preparing the task The criteria

covered both linguistic and paralinguistic area and credit was given to both teamwork

and individual effort (see appendix 1 ).

pants a similar 1 validity . group 0 the aud

gradeS

~

Pre-In

tively. ticipant Engiish in strum give thSurve

Comparing the Eifects ofTwo Types of Drama Activities on TechnologyStudents' English Le(Jming , 253

Pre- and final-test

An oral interview serving as pre-test was administered to both groups of partici pants at the beginning of the course for evaluation of whether the two groups are of similar level of oral English competence (see appendix 2) for information regarding validity and reliability of this test, including the construction, administration and scor ing details). A final-test, in this case, the drama performance, was administered at the end of the semester. For inter-rater reliability, two other teachers - Without being informed of the differences in the procedures of the application of the two types of drama activity-were invited to partiCipate in the grading of the drama performance of both of the groups. The criteria (see appendix 1) for the evaluation/ grading of the performance have been agreed upon by the invited teachers. The grade of each drama group of both of the classes was derived from the mean of the three scores given by the author and the invited teachers. Table 3 is a summary of the comparison of the grades of both of the tests of the two groups.

Pre- and Post-Survey

In addition to the administration of the pre- and final-tests, a pre-survey and a post-survey (listed in the folloWing) concerning participants' current views about English learning were administered at the beginning and end of the semester, respec tively. This execution was intended to facilitate the author in discovering-from par ticipants' perspective- more facts about the range of difference in several aspects of English learning after the application of the two versions of drama activity. Both of the instruments were in a five-point Likert-type scale format so that respondents could give their perceptions of importance for each from one (low) to five (high).

Survey Instruments

duced in English, and then translated into Chinese. Back-translation (Green and White, 1976) was adopted to confirm the level of accuracy and make proper adjust ments. The process included the original English being translated into Chinese by a native Chinese-speaking researcher, and then translated back into English by a na tive Chinese speaker with good English skill, who was not involved with the research. Adjustments were made and the process was repeated for reasonably good matching of the original and translated English versions.

In order to establish an appropriate and useful survey instrument, two essential characteristics of measurement considered and measured in this research study were validity and reliability. In order to determine the validity of the survey instruments in this research study, a judgmental analysis was used. Two experts in the field of re search design and drama activity as teaching approach were invited to examine two types of validity: face validity and content validity. A preliminary questionnaire of the survey was first designed by the author. It was grounded on the condition that the survey questions used did not cause any ambiguity by over 90% of the respondents.

Two experts in the field of research design and drama activity as teaching approach examined the questionnaire and made recommendations about the proper scaling techniques and wording of options in the items of the questionnaire. The survey ques tionnaire was field tested with several students in Chaoyang University of Technology, it included two sections : a five-point Likert-type rating and demographics. Reliability

analysis and ANOVA analysis were chosen as statistic methods for data processing and analysis. Adopting SPSS/ PC+, a reliability analysis has been conducted with the result of Alpha=.8298. Table 4 and 5 show the results of the pre- & post-survey of two different groups.

Data Analysis and Discussion

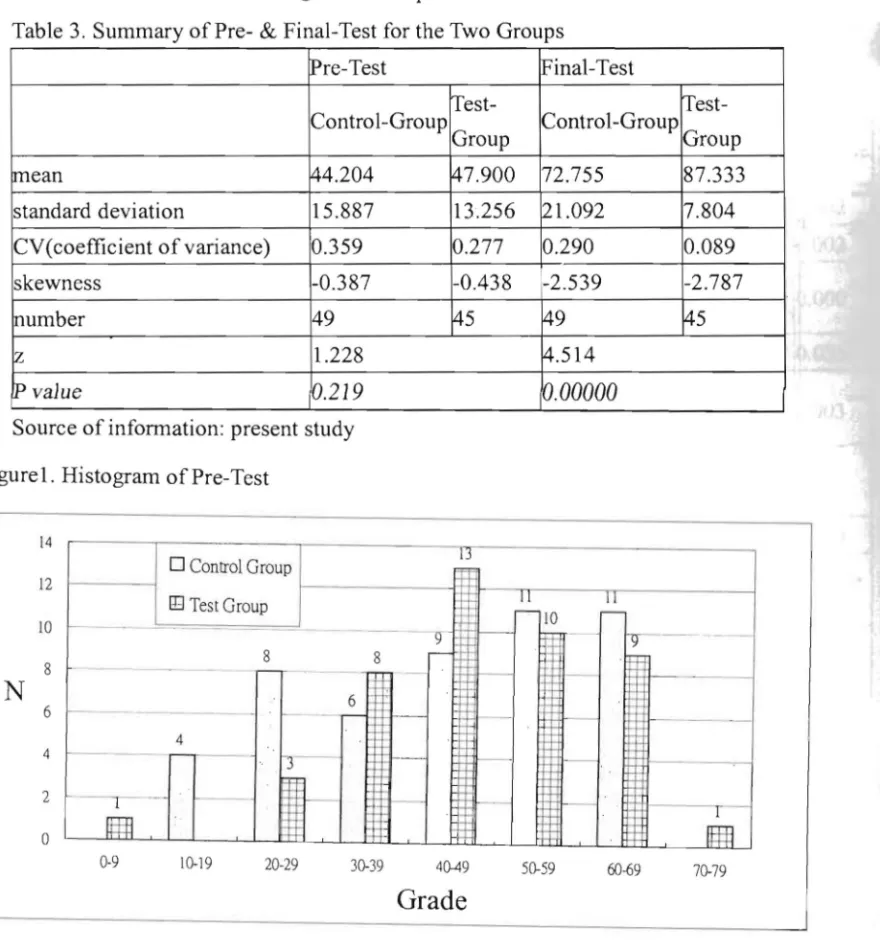

Pre-Test

Z-test was used to find any differences between the two groups. Table 3 shows that the difference of the means and standard deviation of these two groups are not

statistil The da averagE tence. I Table : ean standa CV(co skewn umbe valUl Source Figurel. H 14 \

\2\

10 8N

6 4 2o

Source cComparing the ElTecl~ ofTwoTypes of Drama Activities on Technology Students' English Learning . 255

statistically significant, which come very close at p=0.219 or Z=1.22 8<ZO.025=1.96. The data proVide inconclusive information for deciding which class had the higher average score, indicating that the two groups are at similar level of English compe tence. Figure 1 shows the histogram of the pre-test.

Table 3. Summary of Pre- & Final-Test for the Two Groups

IPre-Test lFinal-Test ~est- ~est-Control-Group Control-Group Group Group mean 44.204 47.900 72.755 87.333 standard deviation 15.887 13.256 ~1.092 7.804 CV(coefficient of variance) 0.359 0.277 0.290 0.089 skewness -0.387 -0.438 -2.539 -2.787 Inumber 49 145 ~9 145 iZ 1.228 ~.514 fP value 0.219 ~. OOOOO

Source of information: present study

Figure1 . Histogram of Pre-Test

14 12 10 8

N

6 4 2 o 40-49 50-59 60-69 70-79 D Control Group u 1" ([J TestGroup - - - g 8 8 - - ~- ' -6 r--- - - -- -4 1 - - -- - r - - 3 -- _.- - -- I-m

0-9 10-19 20-29 30-39 r -II II r - IO r -~ - -p: - I-- -~.-I-- -~---~~m

Grade

Final-Test

According to z-test, Table 3 shows that the difference of means and standard

deviation of these two groups are statistically Significant, which come at p=O.OOO or Z=4.514>ZO.025=1.96. The data provide the information that the average score of the test-group is higher than that of the control-group, suggesting that the test-group has made better performance than the control-group. Figure 2 shows the histogram of

final-test.

Figure 2. Histogram of Final-Test

45 40 40 ~ -35 30 N 25 20 15 10 0 -.3 _..

I l

0-9o

Control Group r - - - - 6J Test Group 15 15 . .--- r - - 5 2 --~ 3 _h1EBl

60-69 70-79 80-89 Grade --I-I+H-I---I II 90-99Source of information: present study

Pre-

jTc

G1'Cmp) Question NUl 1. The degree 2. The degree 3. The degr( learned. 4. The efficieJ 5. The degree influenced yo 6. The degree ositively infl 7. Your curren 8. The necess for your Engli 9. The degree English info**:p<o.o

Comparing the EfTecL~ ofTwoTypes of Drama Activities on Technology Students' English Learning . 257

Pre-

and Post-SulVey

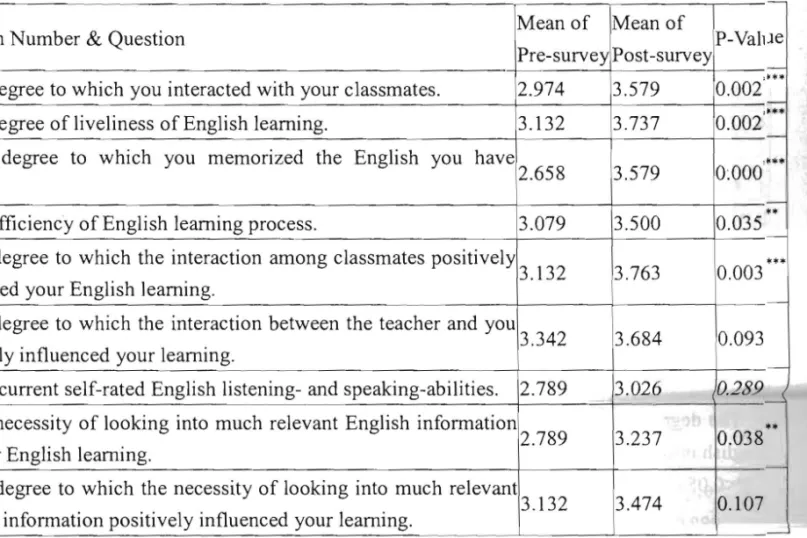

Table 4 and 5 show the results of the pre- &post-survey of two different groups Table 4. Results of Pre- & Post-Survey Questions of English Learning (Control Group)

Number & Question

.The degree to which you interacted with your classmates. The degree of liveliness of English learning.

The degree to which you memorized the English you

The efficiency of English learning process.

The degree to which the interaction among classmates positivel ed your English learning.

The degree to which the interaction between the teacher and yo

. 'vely influenced your learning.

,Your current self-rated English listening- and speaking-abilities.

The necessity of looking into much relevant English informa your English learning.

The degree to which the necessity of looking into much relev information positively influenced your learning.

**:P<O.05 ···:P<O.Ol

Table 5. Results of Pre- & Post-Survey Questions of English Learning (Test-Group)

Mean of Mean of )

Question Number & Question Pre-surv Post-sur P-Value

I

ey vey

1. The degree to which you interacted with your classmates.

3.444 4 0.004'" ]

2. The degree of liveliness of English learning. 3.667 4.194 0.001'"

j

3. The degree to which you memorized the English you have learned.

0.00

I···

2.667 3.389

4. The efficiency of English learning process.

I

0.011·· 3.194 3.611

I

5. The degree to which the interaction among classmates positively

0.001···

3.611 4.194

influenced your learning.

6. The degree to which the interaction between the teacher and you

0.026··

3.722 4.083

positively influenced your English learning.

0.037"· 7. Your current self-rated English listening- and speaking-abilities. 3.111 3.639

8. The necessity of looking into much relevant English infonnation for

0.000•••

1

2.889 3.806your English learning.

9. The degree to which the necessity of looking into much relevan t

0.218

3.611 3.861

English infonnation positively influenced your learning. I

**:P<0.05 ·":P<O.OI

Source of information: present study

A general look at the results above shows that both types of drama actiVity are regarded positively by the subjects. The results of Question 1 revealed that the ratings of both control-group (pre-survey M=2.974, post-survey M=3.579, P<O.Ol) and test group (pre-survey M=3.444, post-survey M=4, P<O.01) are significantly higher, sug gesting that both groups of learners regard that they have made greater interaction

with U '1"t\~ T~ M=3. SUNe: regarc of live r sUNeJ posH learns tating reveal M=3.B are sig cation The r6 M=3.1 survey regard drama surveJi post-s learne there learnil are nG

1

Comparing the EITects ofTwo Types of' Drama Activities on Technology Students' English Leaming , 259

with their classmates after the application of their respective type of drama activity. The results of Question 2 revealed that the ratings of both control-group (pre-survey M=3.132, post-survey M=3.737, P<O.Ol) and test-group (pre-survey M=3.667, post survey M=4.194, P<O.O 1) are significantly higher, suggesting that both groups of learners regard that, after the application of their respective type of drama activity, the degree of liveliness of English learning has been increased.

The results of Question 3 revealed that the ratings of both control-group (pre survey M=2.658, post-survey M=3.579, P<O.Ol) and test-group (pre-survey M=2.667, post-survey M=3.389, P<O.Ol) are significantly higher, suggesting that both groups of learners regard that the application of their respective type of drama activity is facili tating in their memorization of previously learnt English. The results of Question 4 revealed that the ratings of both control-group (pre-survey M=3.079, post-survey M=3.500, P<0.05) and test-group (pre-survey M=3.194, post-survey M=3.611, P<0.05) are significantly higher, suggesting that both groups of learners regard that the appli cation of their respective type of drama activity is efficient as English learning process. The results of Question 5 revealed that the ratings of both control-group (pre-survey M=3.132, post-survey M=3.763, P<O.Oi) and test-group (pre-survey M=3.611, post survey M=4.194, P<O.O 1) are significantly higher, suggesting that both groups of learners regard that the kind of interaction among classmates that their respective type of drama activity has created has positively influenced their English learning.

The results of Question 8 revealed that the ratings of both control-group (pre survey M=2.789, post-survey M=3.237, P<0.05) and test-group (pre-survey M=2.889, post-survey M =3.806, P<O.O 1) are significantly higher, suggesting that both groups of learners regard that, under the application of their respective type of drama activity, there is the need of looking into much relevant English information for their English \~'O.n\\l\'?,. '\'\\~ \~?:'u.\\?:' 0\ Qu.e?:'\lon \d, however, revealed that the ratings of both groups

are not significantly higher, suggesting that both groups of learners regard that the necessity of looking into much relevant English information is not particularly helpful

in their English learning.

drama activities, some differences were found in certain aspects, particularly in the

areas of: (a) the degree to which the interaction between the teacher and the partici

pants positively influenced their learning (Question 6, pre-survey M=3.722, post

survey M= 4.083, P <0.05) ; and (b) participants' self-rated English listening-and

speaking-abilities (Question 7, pre-survey M=3.111 , post-survey M=3.639, P <O.05)

. As could be seen from Table 5, the test-group subjects ratings of the two questions

have made statistically significant differences after the application of the drama activ

ity adopting self-created script. While in the control-group, no significant difference

could be found from subjects' ratings of the two questions.

Based on the analysis of both groups of subjects' oral pre-test and final per

formance, starting from relatively equal level of oral profiCiency, the test-group has

made greater progress in the final performance. And judging from the results of the

comparison between pre- and post-survey of both of the groups, it seems that gener

ally speaking, both types of drama activity are regarded pOSitively by the subjects, and

that both groups of learners regard that: (a) they have made greater interaction With

their classmates; (b) the degree of liveliness of English learning has been increased;

(c) drama activity is facilitating in their memorization of previously learnt English;

(d) drama activity is efficient as English learning process; and (e) the interaction

among classmates has positively influenced their English learning. By adopting self

created script drama activity, the folloWing differences were found: (a) the teacher

students interaction seems to be more influential on the subjects learning; and (b)

the subjects regard themselves as having made progress in English listening- and speaking-abilities. Finally, both groups of learners regard that the necessity of looking into much relevant English information is not particularly helpful in their English learning.

In summary, both types of drama activity seem to be, from subjects' perspectives:

(a) effective in producing interaction among students which is regarded by students

as positively influential on their learning; (b) faCilitating students memorization of

previously learnt English; and (c) an effiCient English learning process. The self

cree lear add! acti\ whil activ of dr the il to stl

Cor

conVE Engli1 1t the! to the dram2 actiVit positi\ effect Iinterac

Possiblcreated script type of drama activity seems to be benefiCial ill the areas of: (a)

Comp~ring the meets ofTwo Types or Drama Activities on Technology Students' English Leilming , 26 1

creating teacher-students interaction which seems to be influential on students '

learning; and (b) promoting students' English listening- and speaking-abilities. In addressing the question of whether students' perception towards the effects of drama activities on English learning is consistent with actual learning outcome, it seems that, while both groups of students C consider favorably their respective type of drama

activity, the test-group's students - under the application of self-created script type of drama activity- outperform the control-group in the final performance. This has the implication that self-created script type of drama activity may be more beneficial to students' learning outcome.

Conclusion

This study investigates the use and effects of two types of drama activity in the conversation class and compares their contribution, from students' perspective, to English learning. It explored the benefits that drama activities bring to the classroom. :t then introduced the respective procedures for the employment. Students' responses to the survey were compared and analyzed, The results revealed that both types of drama activity were regarded favorably by the students, particularly due to drama activities' (a) positive influence on bringing about interaction among students; (b) positive influence on increasing liveliness of English learning; and (c) facilitative effect on students' memorization of previously learnt English.

While both types of drama activity were regarded favorably by the students, according to the grades of the final drama performance of both of the groups, self created script type of drama activity may be more beneficial to students' learning

outcome. In addition, the test-group's perspectives towards the application of drama activity differ significantly from the control-group's in the following aspects: (a) the degree to which subjects' learning is positively influenced by teacher-student interaction; and (b) subjects' self-rated English listening- and speaking-abilities. Possible reasons for test-group's higher rating of teacher-student interaction's posi tive influence on their learning may be that, in creating their own script of the drama,

students' were required to discuss regularly with the teacher the problems they had

regarding sentence level production or pronunciation of certain words to avoid long

term memory of incorrect English usage after the project (Groenewold, 1993) . The reason why students perceived that they have made progress in English listening and speaking-abilities may be that, since they were allowed to put in the script what ever kinds of language use suitable for their communicative purposes, they had the opportunity to focus on learning whatever structures or vocabulary they were most interested in, hence more motivated to learn them by heart. Equally important, the students were involved in the process of decision-making regarding learning content and the production of the sentences they needed, instead of passively accepting what

ever teaching material written or chosen for them. This upholds Brumfit's and Johnson's

(1979) emphasis that language teaching is not packaged for learners, it is made by them. What Bidwell (1990), Kutiper (1988) and Lin (2002) have suggested may be applied here, namely, we should help our students turn their stories into plays. It is possible that students are more motivated to learn when they are in control of the learning process with some guidance from the teacher as a resource and facilitator;

and when students become negotiators with themselves, with other students, and with

the process itself (Richards and Rodgers, 1986: 77) they are forced to communicate

and cooperate with others. Further empirical studies on the procedures which pro

mote better cooperation among students, better teacher-student interaction as well as better learning effect in a drama-based teaching framework may be benefiCial.

Acknowledgement

Funding for this research was provided by the R.O.C. Government' s National Sci

ence Council.

References

Altschuler, L. 2000. Taiwan Topics. A Discussion Book About Taiwan for Inter

medi

tiona

fIuenLang

dram,Englis

culturE as Me Shaw, Horal

pr

sium 0and Ct

CComparing the ElTeets orTwo Types of Drama Activities on Technology Students' English Leaming . 263

mediate and Advanced Learner of English. Taiwan: King-An Publishing and Educa tional Institute.

Bidwell, S. M. 1990. Using drama to increase motivation, comprehension, and fluency. Journal of Reading 34/1 : 38-41, September.

Brumfit, C. J., and Johnson, K. (EdsJ 1979. The Communicative Approach to Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ernst-Slavit, G., & Wenger,

K

J. 1998. Using creative drama in the elementary ESL classroom. TESOL Journal 30-33, Summer.Goalen, P. 1996. The development of children' s historical thinking through drama. Teaching History 83: 19-26.

Griffee, D. T 1986. Listen and act: from simple actions to classroom drama. English Teaching Forum 18- 23, April.

Groenewold, p. 1993. Simulations for intercultural learning: learning a foreign culture and a foreign language with the help of invented characters. In Towards Drama as Method in the Foreign Language Classroom, eds. by Manfred Schewe and Peter Shaw, 81-101 . Frankfurt, Germany: Lang.

Ho, Y. K. 2002. Comparing the effects of three types of drama activities on the oral practice of technology students. Papers from the Eleventh International Sympo sium on English Teaching, ed. by Johanna Katchen, Leung Yiu-nam, Dai Wei-yang, and Chen Peng-hsiang, 336-347. English Teachers' Association/ ROC: Taipei.

Holden, S. 1982. Drama in Language Teaching. Harlow, Essex: Longman. Hsu, V. 1975. Play production as a medium for learning spoken Chinese. ERIC: EDl12667.

Hudson, E. (1994). TESOL methodology and the constraints of context. TESOL Matters 4/6: 21.

Hughes, A (1989). Testing for Language Teachers. Cambridge University Press. Kutiper, K. 1988. Finding the story in each of us through instructional media.

English Journal, March, 76-77.

Jong, J. m. 2001. Jih Shuh Shyue Yuann Ing Yeu Jiau Tsair Jiau Faa Van Jiow ( Research of English teaching materials and methodology for technology colleges J

"

c

Gwo Ke Huey Yan Jiow Jih Huah Baw Gaw ( National Science Council's end of project report) .

Jou, M. J. and Kai, 1. S. 1995. Ru Her Yeou Shiaw Yunn Yonq Yeu Yan Shyue Shyi Mo Nii Chyng Jing Yu Dah Ban Ing Yeu Huey Huah Keh (How to effectively apply language learning simulation context to large English conversation class) . Ren Wen Jyi Sheh Huey Shyue Ke Jiaw Shyue Tong Shiunn (Journal of Humanities and Science Teaching) 4, 6-27.

Lin, H J. 1996. The study of students' survey in the methodology for English Instruction. Journal of Chaoyang University of Technology 107-124.

Lin, H J., and Warden, C. A 1998. Different attitudes among non-English major EFL students. The Internet TESL Journal, ( On-line) , http://www.aitech.ac.jp/ -iteslj/ Articles/ Warden-Difference/, (October) .

Lin, H. J. 2003. A preliminary study of drama activity in large non-English major EFL Classrooms: a report of students' views. Chaoyang Journal of Humanities and SOCial SCiences. In print.

Lindsay, P. 1974. The use of drama in TEFL. English Language Teaching J our nal 29/1: 55-59, October.

Long, M. H., and Porter, P. A 1985. Group work, interlanguage talk, and second language acquisition. TESOL Quarterly 19/ 2: 207-228, June.

Luo,

Y.

P. 1999. Experiential language learning: expanding student learning styles through drama. Studies in English Language and Literature 6: 9-28.Madsen,

H.

S. 1983. Techniques in Testing. Oxford University Press.Maley, A, and Duff, A (1982). Drama Techniques in Language Learning. Cam bridge UniverSity Press.

Moss, W. E. 1971. The play' s the thing. English Language Teaching 161-164. Palmer, H. E., & Palmer, D. (1925). English Through Action. Tokyo: Kaitakusha. 43-44.

Richards, J. C., and Theodore S. Rodgers. 1986. Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching, Cambridge University Press.

Schewe, M., &P. Shaw. 1993. Towards Drama as" Method in the Foreign Lan

guage Clas Sheu, Conversati( Shimi working~ Towards D Schewe aru Somel Fun Theatr Stem. That Work, House Publ Sy.B. language Ie TEFL Con!1

Via.R

drama. In Ir Cambridge Wesse second Group Topic: 1.

-Comparing t;ie Effects ofTwo Types or Drama Activities on Technology Students' English Learning . 265

guage Classroom. Frankfurt, Germany: Lang.

Sheu, J. J. 2001. Development of Web-based Courseware for Freshman English Conversation. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Tamkang University, Taipei.

Shimizu,

T.

1993. Initial experiences With improVised drama in English teaching: working against the historical neglect of fluency in language learning in Japan. In Towards Drama as Method in the Foreign Language Classroom, eds. by Manfred Schewe and Peter Shaw, 139-169. Frankfurt, Germany: Lang.Somers, J. W. 2001. A workshop on drama in language learning. Haohsiung :

Fun Theatre.

Stern, S. L. 1983. Why drama works : a psycholinguistic perspective. In Methods That Work, eds. by John W Oller, Jr., and Patricia

A

Richard-Amato. Rowley: Newbury House Publishers, Inc.Sy. B. M. 1995. Gender differences, perceptions on foreign language learning and language learning strategies. Conference Presentation in the Twelfth Annual RO.C. TEFL Conference.

Via, R A 1987. "The magic if" of theatre: enhancing language learning through drama. In Interactive Language Teaching, eds. by W. M. Rivers, 110-123. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wessels, C. 1987. Drama. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yan, J. C. 1997. Making drama a part of curriculum when teaching English as a second language. Dah Ren Journal 15: 119-128.

Appendix 1: Drama Activities' Evaluation Form

Group Members: _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ __ _ __ __ _

Topic:

1. Accuracy (20%) _ _ _grammar

I : 2. Fluency (2096) 3. Appropriacy (2096) _ _ _ Intonation _ _ _ Speaking naturally

4. Body language and faCial expression (1096)

5. Creativity (1096)

6. Props and costumes (1096)

7. Team cooperation

C1 0

96)Total : _ _ _ _ _ __

Appendix

2 :

Pre-Test (Oral Interview)

An oral interview with the same questions for both of the classes was used for the pre- test of this study. Following is a description regarding the validity and reliability of these two tests, which proceeds with the order of (a) construction and administra tion, and (b) scoring.

Construction and Administration. 'TWo testers/ scorers conducted a face-to-face

interview in a relaxed, quiet and informal setting. The testers/ scorers paid attention to behave neither harsh nor familiar, neither condescending nor intimidating. Care was taken that the testers/ scorers tried to be sincere, open, and supportive in manner. In

order to standardize the test for the candidates, a guided oral interview was used.

Wide varieties of elicitation techniques were used. Either/or questions, yes/ no ques tions, and information questions were included. In addition, items that provide infor

mation

given

Ispendi

viewVltension

two, on tasks ~langu8i

reasoDl

marks

8< ing wa compethave

th ofspee

thetwo

on a sUfluency

,

ten. CalComparing the Errect~ ofTwo Types of Drama Activities on Technology Students' English Learning , 267

mation that needs qualifying, revising or correcting were used. The candidates were given as many "fresh starts" (separate items) as possible. Care was taken to avoid spending too much time on one particular function or topic. The items on the inter view varied in difficulty, with easier questions coming early, however, to help relieve tension and allow the candidate to regain confidence, after a more challenging item or two, one or two easy questions was/were inserted. Candidates were given only the tasks and topiCS that would be expected to cause them no difficulty in their own language. The initial stages of the interview were made within the capacities of all reasonable candidates, for example, straightfOIward requests for personal details, re marks about the weather, and so on, were used.

Scoring. For the purpose of obtaining valid and reliable scoring, objectified scor ing was adopted, since in the area of speaking, the criteria of oral communicative

competence are less well defined, and the vast majority of language teachers do not have the sophisticated training needed to prOvide consistent, accurate holistiC grading of speeCh. Adopting part of the American FSI (Foreign Service Institute) procedure, the two testers/scorers concerned in each interview were required to rate candidates on a six-pOint scale for each of the following aspects: accent, grammar, vocabulary, fluency, comprehension. These ratings were then weighted and totaled and divided by ten. Care was taken that irrelevant features of performance were ignored, and any logically appropriate and comprehensible response was acceptable. Since speaking tests are always productive, partial credit was allowed for partially correct responses. For training of scorers, the descriptions of the above criteria levels were clearly written and the two testers/scorers were trained to use them. Recordings of past interviews were played to clearly represent different criteria levels. The two testers/

scorers independently assessed each candidate, and care was taken to avoid the situ ation that the testers/ scorers were seen to make notes on the candidates' perfor mance during the interview, Scoring was made immediately1. Recording of each ses sion was made to assist in the resolution of possible occurrence of disagreement between the scorers.