行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 期末報告

海外銷售子公司負責人任用決策之研究-以台灣企業為例

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型

計 畫 編 號 : NSC 101-2410-H-004-187-

執 行 期 間 : 101 年 08 月 01 日至 102 年 10 月 31 日

執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學企業管理學系

計 畫 主 持 人 : 于卓民

公 開 資 訊 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,2 年後可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 103 年 01 月 02 日

中 文 摘 要 : 多國企業之海外子公司是否能克服文化障礙、充份運用當地

資源來達成母公司所交付的任務、遵守母公司所訂之各種規

範以達成母公司之策略目標,子公司負責人扮演著重要角

色。然而目前文獻中有關子公司主管的任用,多是考量母國

籍員工、地主國籍員工及第三國籍員工三種方案,但台灣企

業因為缺乏國際性人才,因此外部挖角產業高手亦是常見的

方式,而運用此方式之策略面與管理面的考量,均與任用公

司內部幹部不同,因此挖角宜列入任用決策中之另一重要選

項。 再者,目前文獻的研究樣本主要是以製造子公司或是製

造與銷售子公司混合,但製造子公司與銷售子公司在性質與

運作上截然不同,負責人所需執行的任務與需具備的條件自

也不同,因此本研究擬探討母公司在任用海外銷售子公司負

責人時,會受到那些因素影響,以及各因素的相對重要性為

何。 此外,目前有關海外直接投資(FDI)的研究,主要是以

順向 FDI 為主,但近年來新興經濟體中越來越多的企業開始

進行逆向 FDI,而逆向 FDI 中多國企業所遭遇的問題,是西

方的多國企業所未曾遇見的,此亦會影響到子公司負責人之

派任考量,因此本研究擬探索母公司在進行逆向 FDI 或順向

FDI 時,對海外銷售子公司負責人的指派,所考慮因素是否

不同,以及不同的原因為何

中文關鍵詞: 海外銷售子公司、子公司負責人、順向直接投資、逆向直接

投資、任用決策

英 文 摘 要 : More and more firms from developing countries (LDCs)

have located their investments in developed countries

(DCs) (i.e., upstream FDI). However, few researchers

have examined sales subsidiaries which are different

from manufacturing subsidiaries. This study uses a

case study approach to examine how the sales

subsidiaries of Taiwanese high-tech firms structure

their sales channels and manage their channels in

DCs. The findings show that:

LDCMNCs tend to use multiple sales channels, to work

with large national distributors, and to adopt high

touch channels to market products;

To reduce channel conflict, less powerful LDCMNCs

adopt multiple independent channel systems;

Due to limited resources, LDCMNCs try to design

channel conflict prevention mechanisms, emphasize

more on building distributors relationships and use

financial/high-power incentives to motivate

distributors.

2. Track: Cross-cultural Management and International

HRM

Title: Top management teams, leader succession &

organizational culture'Managing Channels by Foreign

Sales Subsidiaries: The Case of Firms from Developing

Countries Operating in Developed

Countries,'Hsiao-Wen Lin, Chwo-Ming J. Yu and Hui-Yu Chiu

Following the path of multinational corporations

(MNCs) from developed countries (DCs), more and more

firms from developing countries (LDCs) have engaged

in foreign direct investment (FDI), especially in DCs

(i.e., upstream FDI). However, only a few researchers

have examined the issues related to upstream FDI.

Furthermore, in examining firms' activities in host

countries, most researchers have taken manufacturing

subsidiaries as taken-for-granted research samples.

Only a few studies put sales subsidiaries into

consideration.

Using a case study approach, this study addresses two

research questions: (1) what is the process of

setting up sales subsidiaries in DCs by Taiwanese

high-tech firms and how these subsidiaries operate? ,

and (2) how do Taiwanese high-tech firms select the

first country managers for sales subsidiaries in DCs?

英文關鍵詞: foreign sales subsidiaries, upstream FDI, country

研究計畫名稱:

海外銷售子公司負責人任用決策之研究-以台灣企業為例

計畫編號:

101-2410-H-004-187, 2012.08.01 至 2013.07.31

報告人: 于卓民

內容:

本計畫之研究成果已於 2013 年七月於

Academy of International

Business 之年會發表。兩篇文章之相關資訊如下:

1. Track: Developing Country Multinational Companies Issue: Capability learning

and the external environment of developing economy MNEs

Title:“Factors Affecting the Staffin01g of General Managers of Foreign

Subsidiaries,” Hsiao-Wen Lin, Chwo-Ming J. Yu , and Hui-Yun Chiu

More and more firms from developing countries (LDCs) have located their

investments in developed countries (DCs) (i.e., upstream FDI). However, few

researchers have examined sales subsidiaries which are different from manufacturing

subsidiaries. This study uses a case study approach to examine how the sales

subsidiaries of Taiwanese high-tech firms structure their sales channels and manage

their channels in DCs. The findings show that:

LDCMNCs tend to use multiple sales channels, to work with large national

distributors, and to adopt high touch channels to market products;

To reduce channel conflict, less powerful LDCMNCs adopt multiple

independent channel systems;

Due to limited resources, LDCMNCs try to design channel conflict prevention

mechanisms, emphasize more on building distributors relationships and use

financial/high-power incentives to motivate distributors.

2. Track: Cross-cultural Management and International HRM

Title: Top management teams, leader succession & organizational culture

“

Managing Channels by Foreign Sales Subsidiaries: The Case of Firms from

Developing Countries Operating in Developed Countries,”Hsiao-Wen Lin,

Chwo-Ming J. Yu and Hui-Yu Chiu

Following the path of multinational corporations (MNCs) from developed countries

(DCs), more and more firms from developing countries (LDCs) have engaged in

2

foreign direct investment (FDI), especially in DCs (i.e., upstream FDI). However,

only a few researchers have examined the issues related to upstream FDI.

Furthermore, in examining firms’ activities in host countries, most researchers have

taken manufacturing subsidiaries as taken-for-granted research samples. Only a few

studies put sales subsidiaries into consideration.

Using a case study approach, this study addresses two research questions: (1) what is

the process of setting up sales subsidiaries in DCs by Taiwanese high-tech firms and

how these subsidiaries operate? , and (2) how do Taiwanese high-tech firms select

the first country managers for sales subsidiaries in DCs?

Factors Affecting the Staffing of General Managers of Foreign Subsidiaries ABSTRACT

Following the path of multinational corporations (MNCs) from developed countries (DCs), more and more firms from developing countries (LDCs) have engaged in foreign direct investment (FDI), especially in DCs (i.e., upstream FDI). However, only a few researchers have examined the issues related to upstream FDI. Furthermore, in examining firms’activities in host countries, most researchers have taken manufacturing subsidiaries as taken-for-granted research samples. Only a few studies put sales subsidiaries into consideration. Using a case study approach, this study addresses the following two research questions: (1) what is the process of setting up sales subsidiaries in DCs by Taiwanese high-tech firms and how these subsidiaries operate? , and (2) how do Taiwanese high-tech firms select the first country managers for sales subsidiaries in DCs? The research findings would enhance our understanding of upstream investment and offer managerial implications for LDCMNCs when operating sales

subsidiaries in DCs.

INTRODUCTION

Multinational corporations (MNCs) from developing countries (LDCs) operate internationally deems not new phenomenon, numerous professionals have examined the presence of LDCMNCs (Agmon and Kindleberger 1977; Heenan and Keegan 1979; Kumar and McLeod 1981; O’Brien 1980). However, only a few studies have paid attention on how these firms fight against in the market under developed countries (DCs) context. Past research on foreign direct investment (FDI) tends to focus on the investing behavior of firms from DCs (Makino, Lau, and Yeh 2002). Therefore, the studies on FDI and management of foreign subsidiaries by MNCs can be classified based on the level of economic development of a host country as horizontal FDI if a host country is a DC or downstream FDI if a host country is a LDC. In recent years, the emergence of MNCs from LDCs (e.g., HTC and Asus) has again raised the attention of researchers. Unlike MNCs from DCs which tend to be larger, with strong brand names and ample resources, MNCs from LDCs usually have limited resources and thus what they do in DCs may be different from what MNCs from DCs do in these DCs.

Downstream FDI refers to MNCs conducting investment in countries with lower degree of economic development comparing with their home countries, while upstream FDI means that MNCs conducting investment in countries with higher degree of economic development comparing with their home countries (Kwok & Reeb 2000; Makino et al. 2002). For upstream FDI, MNCs from LDCs encounter dual problems, liability of foreignness (Hymer 1967) and liability of country of origin (Chang, Mellahi & Wilkinson 2009). Thus, how MNCs operate in DCs may not be applicable to MNCs from LDCs do in DCs and current literature seldom elaborates this issue. This study intends to shed some lights on this issue.

In addition, most researchers in international business do not distinguish between manufacturing subsidiaries and sales subsidiaries (Colakoglu and Caligiuri 2008; Belios and Bjorkman 2000) and only a

few studies take sales subsidiaries as the study samples. However, the motivations of investment, capital needed, and management of subsidiaries are different. For example, the major responsibility of a sales subsidiary is to market imported products from a parent company to distributors or consumers in a host country (Yu & Liao 2005). Therefore, management expertise of the country manager needed is different for manufacturing and sales subsidiaries. There are two other challenges for sales subsidiaries. First, though low cost is an attraction, products marketed should have some differentiation, especially for industrial users (Yu & Liao 2005). And second, to market products successfully, the impact of local cultural and social factors should be considered (Wang, Jaw & Huang 2008). These challenges would be more amplified for the case of upstream investment.

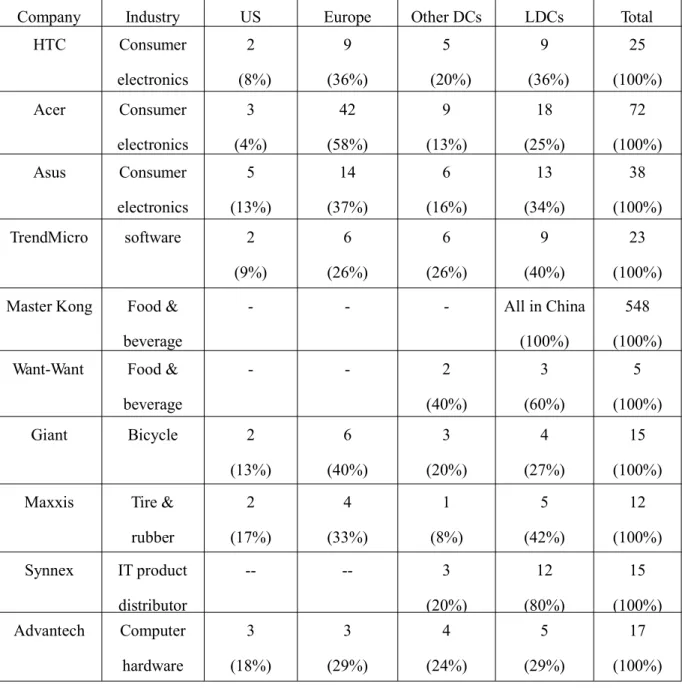

Numerous firms from Taiwan have started to market their products internationally and set up foreign sales subsidiaries. Table 1 shows the distribution of host countries where the 10 leading firms have sales subsidiaries. It is clear that, except for the two food and beverage firms, most firms have mainly located their sale subsidiaries in DCs. This reflects the importance of foreign sales subsidiaries in DCs for Taiwanese firms, a developing country. This also suggests the adequacy of examining the issue of upstream FDI, in terms of sales subsidiaries, by using Taiwanese firms as samples. Two research

questions of this study: (1) what is the process of setting up sales subsidiaries in DCs by Taiwanese high-tech firms and how these subsidiaries operate? , and (2) how do Taiwanese high-high-tech firms select the first country managers for sales subsidiaries in DCs? We hope that the research findings can shed some lights on our understanding of upstream investment particularly for developing countries who are trying to expand globally.

The research is organized as follows: the first section introduces the study background and research questions; the second section review previous literature; the third section contains the research

paper.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The Establishment of Foreign Sales Subsidiaries

The international business literature has often treated foreign subsidiaries as the research sample; however, only a few has studied issues related to foreign sales subsidiaries. Many studies have focused on the location choice as well as the entry modes of subsidiaries; a few studies have examined the processes of setting up sales subsidiaries and post-establishment management.

When conducing FDI, the location choice is extremely because it affects later success or failure of the operations in a host country. MNCs investing in a host country may be motivated by exploiting location-specific advantages or their firm-specific advantage (Delios and Beamish 2001; Luo 2000). Chen and Chen (1998) found that the major purposes for Taiwanese firms to invest in developed countries are to build up brand image, gain product technologies and acquire distribution network. When firms from developing countries invest in developed countries, they not only want to exploit their own assets but also to explore new assets (Thomas, Eden and Hitt 2002). Makino et al. (2002) also found that Asian MNCs tend to engage in asset-search and market-search activities in developed countries but to source local production resources (such as cheap labor) in developing countries. Thus, the motivations for Asian MNCs investing in developed and developing countries are different.

MNCs can adopt different entry modes for different reasons. Exporting, licensing and FDI are all possible alternatives (Rugman 1982). FDI can also be divided into mergers & acquisition, joint ventures and wholly-owned greenfield investment (Khoury 1979; Kogu and Singh 1998). MNCs acquire local firms for reasons such as entering a market quickly, gaining complementary capabilities, and acquiring

marketing channels in host countries (Andersson and Svensson 1994; Brouthers and Broithers 2000; Zehan 1990). Many studies have examined the factors affecting MNCs’ entry mode decision, for examples, cost and price (Yu and Tang 1992), ownership advantages, location advantages, the degree of internationalization (Woodcock, Beamish and Makino 1994), host country institutional environment, and internal institutional environment (Davis, Desai, and Francis 2000). However, these studies do not explore or discuss the conditions under which firms from developing countries (e.g., Taiwan) establishing sales subsidiaries in developed countries (e.g., the US). With this purpose, the study elaborates sales- subsidiaries related issues in developed countries only in light of our limited knowledge about them.

Appointing General Managers (GM) for Sales Subsidiaries

The staffing of a GM, the key management position of a foreign sales subsidiary, has always been a debate in international human resource management. MNCs need to decide whether to appoint expatriates from the home countries as the GM or to hire nationals to lead sales subsidiaries. Because of the

importance of this decision and the impact on implementing the headquarters strategies in host countries, the factors affecting the decision need to be elaborated (Edstro¨m and Galbraith 1977; Harzing 2001; Konopaske, Werner, and Neupert 2002; Scullion and Collings 2006).

Edstro¨m and Galbraith (1977) and Harzing (2002) indicated three reasons for staffing a GM’s position with an expatriate:

(1) Filling positions: the more important the job vacancy, the more the need for know-how transfer, and MNCs are more inclining to hire home country nationals when they are in short of suitable local talents.

(2) Management development: through the assignment to develop expatriated managers’ capability and to increase their international perspective, experience and management skills.

(3) Organization development: home country national CMs can ensure the smooth and effective coordination, control and communication between headquarters and subsidiaries.

However, there are two major drawbacks for hiring home country national GMs:

(1) Higher possibility of expatriate failure: the possibility of early returns and the turnover rate is twice higher than that of domestic firms (Naumann 1992); and

(2) High cost (Harvey 1985; Shaffer et al. 1999; Tsang 1999; Wederspahn 1992) of foreign

assignments; in addition, it limits the promotion opportunities for host country nationals, leading to lower productivity and higher turnover rates.

On the other hands, Dowling, Schuler, and Welch (1999) pointed out the advantages for hiring host country national GMs:

(1) Eliminating language barriers, avoiding adaptation problems of expatriate executives and their families and requiring less cost of cultural awareness training;

(2) Reducing the political interference of the host country governments; and

(3) Lowering staffing cost and boosting morale of local employees.

Employing local GMs also has its own problems. First, there are language barrier and conflict between local GMs and headquarters due to cultural differences and national pride. Second, accessing to other subsidiaries’operational experience may be a challenge for local managers. Third, the search cost for a suitable person may be costly and the concern for knowledge or advantage leakage is high. And finally,

local GMs may take inappropriate actions which may damage the reputation of the parent firms.

To summarize, the characteristics of an MNC (Bird, Tayler, and Beechler 1998; Delios and Bjorkman

2000; Dowling, Welch, and Schuler 1999; Harzing 2001; Prahalad and Doz 1981; Widmier, Brouthers, and Beamish 2008) and characteristics of a host country (Bebenroth, Li, and Sekiguich 2008; Delios and Bjorkman 2000; Harzing 2001; Schotter and Beamish 2011; Tseng and Liao 2009; Widmier et al. 2008) are the two major factors affecting the staffing decision for foreign subsidiaries for MNCs. The analytical framework proposed by Harzings (2001) which divides the influential factors into home country/parent company level and host country/subsidiary level is to be more comprehensive. For the home

country/parent company level factors, a parent company tends to assign home country national GMs when there are greater power distance between the two countries involved, greater uncertainty avoidance (Bebenroth et al. 2008), greater cultural distance (Colakoglu and Caligiuri 2008; Tseng, and Liao, 2009), in the early stage of internationalization (Bird et al. 1998; Dowling and Schuler 1009), insufficient host country experience (Widmier et al. 2008), more significance of knowledge-transfer, higher intensity of R&D (research and development) and marketing, more excessive resources (Tseng and Lioa 2009), and

for fully ownership (Schotter And Beamish 2011).

Studies seldom have paid attention to the level of host country factors, particularly for the factors affecting MNCs’staffing decisions as well as the cost comparison between locally recruited managers and expatriates (Harzing 2001). In addition, MNCs would be more incline to hire local executives when the market risk of the host country is high, the higher the local average GDP (gross domestic product) (Widmier et al. 2008), higher population (Bebenroth et al. 2008), stronger host country policy restrictions (Delios and Bjorkman 2000), better location advantages (Tseng and Liao 2009) and lower FDI legitimacy (Schotter and Beamish 2011).

The dependence on the parent firm and the importance of a subsidiary for corporate strategy are the two subsidiary level factors affecting the appointment decision. Prahalad and Doz (1981) indicated that when subsidiary needs to rely on parent company’s capital, technology and management, headquarters would assign home country nationals to head that subsidiary. Nevertheless, after a subsidiary has

developed its own technique and management capabilities, host country nationals would be appointed to key positions. Gupta and Govindarajan (1991) further stressed that a subsidiary’s strategic importance would influence the control posture of a parent company. From a development path, even expatriates serve as executives in the early years of a subsidiary, with the development of a subsidiary, parent companies would raise the number of host country national managers. Furthermore, when a subsidiary exports more (Bebenroth et al. 2008), headquarters relies more on a subsidiary for strategy

implementation (Belderbos and Heikltjis 2005) and a subsidiary gains stronger capability (Tseng and Lioa

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Most international business studies mainly sample manufacturing subsidiaries in foreign markets as the research object; however, the issues regarding how foreign sales subsidiaries operate and manage have seldom been explored. To understand how Taiwanese firms manage their sales subsidiaries in developed countries, we adopted a case study approach. As noted by Eistenhardt (1989), case study is a suitable method for exploring phenomenon because this method stresses an intensive analysis of an individual unit. Eistenhardt (1989) proposed eight steps for organizing and conducting case study successfully: (1)

determining and defining the research questions; (2) selecting cases; (3) collecting data; (4) conducting the research in the field; (5) analyzing the data; (6) comparing across cases for similarities and differences; (7) drawing propositions; and (8) engaging in conversation with relevant literature.

When the line between researched phenomenon and reality remains unclear and relying on multiple sources to gather information, case study is an appropriate approach (Yin 1994). In addition, Yin (1994) suggested three principles in conducting case study: (1) exploiting various sources of information; (2) building case study database; and (3) ensuring the ultimate proof have certain degree of connection. Therefore, for a complex and unknown issue such as the management of overseas sales subsidiaries, a multi-case study, coupled with secondary data, would be useful for gaining insight for future research as well as for offering new research directions.

Taiwan has been recognized as one of the Asia Tigers for its solid economic development. Up to the present, Taiwan’s high-tech firms have played an important role for supplying components and products to the world and some of them have penetrated into the markets in DCs. Thus, the study used Taiwanese high-tech corporations which have sales subsidiaries in DCs as the research sample. Furthermore, these companies need to fulfill the qualification below to be selected to underline the characteristic of channel

management in host countries:

1. The firm needs to manufacture and market products with its own brand name, i.e., purely serving as suppliers to OEMs are excluded; and

2. Foreign subsidiaries with main functions such as manufacturing, R&D, after-sale services and financial transactions are excluded.

To take into account the fact that a general manager may be replaced by a national over time, we focused on the staffing decision when a subsidiary was founded. The two selected cases were all subsidiaries located in DCs. We used face-to-face interviews to gather first-hand information and only executives who were familiar with the operations of a particular subsidiary or were highly involved with the management of a particular subsidiary were qualified to be the interviewees. Before an interview, an e-mail outlining the questions asked was sent to the interviewee and after the interview, phone calls or e- mails were used to gain further information. In addition, firms’ related reports and internal publications were also used for triangulation and clarification.

Brief Case Introduction

Founded in 1979, Company A specializes in producing a variety of bio-pharmaceutical equipments, such as bottle unscramblers, counters and cap retorquers, and chromatography equipments. Company A has 175 employees and has built a solid reputation as a supplier in the industry. The firm has clients in several countries and sales subsidiaries in the United States, China and India.

Establishing in 2002, Company B operates in the photonic industry and has about 148 employees in Taiwan. Its DLP (digital light processing) projector is a leading brand in world market. It has sales

subsidiaries in Hong Kong, Shanghai, the US, Canada, England, Germany, France, Norway, Spain and the Netherlands.

CASE FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

In this section, the case findings about the four sales subsidiaries will be presented first and followed by the case findings.

Case Finding

The sales subsidiaries of Company A in the United States

Entering the US. In 1997 Company A planned to sell its labeling machine in the US due to the large

size of the market for consumer goods. With more than 150 global players, the competition in the marketwas very intense. To differentiate from competitors, Company A took a customer survey and, based on the survey results, designed a new type of labeling machine which can deliver quality assurance function. The firm decided to set up a sales subsidiary instead of relying on sales agents to operate in the US for two reasons. First, interacting with customers is more direct and less information distortion would be encountered with a sales subsidiary. In addition, executing the firm’s marketing strategy would be more thorough for a sales subsidiary.

In 1997, after careful financial evaluation, Company A decided to acquire one of its previous US sales agents and to retain the four employees working in the agent (i.e., the founder and three staffs, all host country nationals). To expand business quickly, the firm purchased a spacious warehouse for housing inventory, partnered with 25 machinery manufacturers to provide customers one-stop shopping service, and negotiated with financial institutions to extend credits for these manufacturers.

Appointing the country manager. Company A believed that the success of a sales subsidiary is highly

dependent on the capabilities of its the general manager (GM). After careful evaluation, Company A decided to invite the founder of the acquired sales agent to be the GM. The decision was based on five reasons:

(1) The owner has better understanding of the company and its employees. In addition, to ease liability of foreignness and cultural distance, it would be beneficial to hire the owner to head the operations.

(2) With the same cultural and language background, the barrier of communication would not be an issue and the founder could respond to customers’needs promptly. The founder also had better knowledge of the government regulations and market which increase the speed of response and acquisition of market information.

(3) With years of working and entrepreneurial experience as well as professional capabilities, the founder would be more devoted to the work.

(4) An expatriate from Taiwan has the advantage of penetrating the local firms running by Chinese. However, firms not running by Chinese are the major customers in the US and a national (the founder) would be more appropriate to expand into this sector.

(5) A trust had been built between Company A and the founder over several years of cooperation. This reduces the cost of communication and governance and increases the adaptability between the parent company and the subsidiary.

Functioning of the sales subsidiary. Company A empowered the GM of U.S sales subsidiary after its

establishment. The major tasks of the sales subsidiaries were:

(1) executing parent company’s overall strategy and marketing activities; (2) market expansion and purchase order-handling;

(4) understanding the needs of customers and building better relationships with customers; and

(5) brand promotion, channel control and channel management.

To promote a less known brand in a competitive market, Company A decided to form a strategic alliance with dozens of small- and medium-sized machinery manufactures in the US. Compared with other competitors, this approach offered customers the convenience of purchasing several equipments in one deal and enjoying timely after-sale services offered by alliance partners. This chain-store type business model increased the firm’s brand awareness quickly. As a result, in a short period of time, 65 manufacturers nationwide joined the alliance. However, managing the alliance was a challenge because it was an informal organization with no legal status, the GM spent lots of effort to keep the alliance

working.

The sales subsidiary of Company B in the United Kingdom

Entering UK. Realizing the potential of projector applications in home entertainment, Company B

entered the consumer market in 1996, after it had built a reputation in selling LCD (liquid crystal display) projectors to business clients, such as IBM and Compaq.

Company B foresaw the potential of projectors market in Europe and decided to enter the UK. In 2002, it set up the first overseas sales subsidiary by acquiring a sales arm in UK from its parent business group. It kept all of the sales arm’s employees because of their knowledge of the country though this knowledge was not directly related to the projectors market. The operations in UK have been successful. Not only the brand awareness has been increased, the sales subsidiary has also become the regional headquarters in Europe.

Appointing the country manager. Before setting up the sales subsidiary, Company B sent a Taiwanese

to develop the British market. The decision was based on four reasons: (1) they need someone that the headquarters can trust; (2) they need someone who has completely loyalty to the headquarters; (3) they need someone that they can easily communicate with; and (4) they feel that the cost would be lower compared with hiring a Breton. After a period of operation, it found out that the market had great potential and, with the growing of the local business, more space for storage and more customer services were needed. Hence it acquired the sales arm from its parent business group and converted the local firm into a sales subsidiary.

Company B selected the Taiwanese who was responsible for market development to head the UK sales subsidiary. The executive had seniority in Company B and had a good track record. Company B believed that the risk of operation in the UK would be reduced with such a trusted and capable person. Initially Company B relied on distributors heavily in the UK to build ties with customers. To strengthen the relationships with the distributors and emphasize the commitment to local operations, the country manager was replaced by a Breton later. However, the regional managing director’s role of the former country manager still enables him to exercise control over this sales subsidiary.

Functioning of the sales subsidiary. Serving as a regional headquarters in Europe, the sales

subsidiary in the UK is in charge of the following tasks related to the region: providing customer services for maintenance, developing products, promoting products and brand, offering education and training programs, and offering quality assurance. A unique role played by the marketing department is its handling of tasks ranging from setting up website, printing catalogs, hosting presses to managing product launching conferences.

products and gather the latest market information so that Company B is able to serve the market better. Therefore, constant training local sales persons and supervising product team and technique team to carry out the strategy of the headquarters are daily work. The country manager needs to report to the

headquarters about its accordance with the annual plan, budget, key performance indicators, cash flows and market information.

DISCUSSION

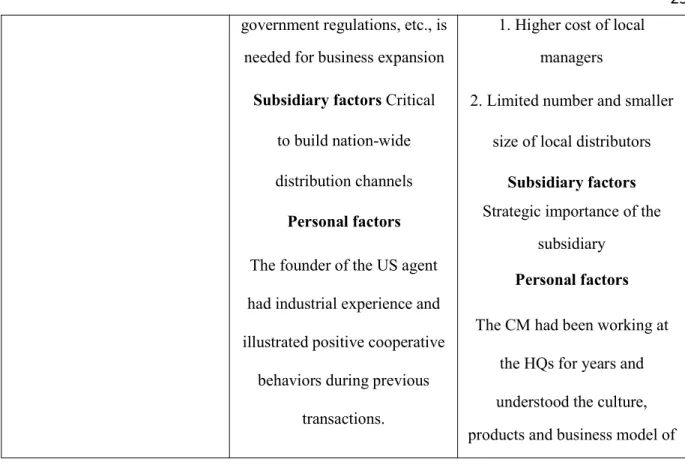

From the case summary in Table 2, we can reach the following conclusions:

1. The market size of a country is the primary consideration for setting up a sales subsidiary.

2. A firm would engage in certain activities before setting up a sales subsidiary in a host country, including: (1) conducting research to evaluate the market entered, entry mode and capital needed, etc.; (2) assigning a country manager; (3) preparing the operations of an office by purchasing some facilities; and (4) recruiting and training local employees.

3. Acquiring either a local sales agent or other firm which a parent company is familiar with, enables a parent firm to get the resources needed for quick entry.

4. The major functions of a sales subsidiary are: (1) collecting market information; (2) expanding business and sales operation; (3) providing after-sales services; (4) establishing and training local sales, product and technical teams; (5) setting annual business plan, budget and KPIs; (6)reporting marketing and operational information to parent companies; and (7) maintaining effective communication with parent companies. Regarding the specifics of what a sales subsidiary does, we can group them into five areas—product, price, distribution channel, promotion, and administration management—as shown in Table 2.

5. Parent company factors, host country factors, and subsidiary factors affect the decision of a parent company in selecting country managers for sales subsidiaries. The most important personal factor for a candidate to be considered for a country manager’s position, in addition to his/her professional capability,

is whether he/she has earned the trust of the parent company.

Regarding the difference in staffing the country manager between the two companies (i.e., Company A appointed the founder of its sales agent and Company B appointed an expatriate from Taiwan), we have the following observations:

1. When a parent company has limited capability to control the operations in a host country, when the cultural distance between the home and host countries is high, and when intensive communication with the parent company is needed, a parent company tends to assign an expatriate who used to be working at the HQs to be the general manger in a host country. On the contrary, when a parent company lacks international talents and when local knowledge is important for business expansion, a parent company tends to recruit an outsider working at a host country, to head a sales subsidiary in a host country.

2. When the level of economic development of a host country is higher than that of the home country, when local market knowledge is important and when host government regulations are tight, a parent company tends to appoint a national of the host country to be the country manager of a sales subsidiary. However, when the compensation cost is too high from the perspective of a parent company, an expatriate from the home country, which is a developing country, would be assigned as the country manager of a sales subsidiary in a developed country.

3. When a sales subsidiary has strategic importance to a parent company, an expatriate would be a preferred choice for the head of the subsidiary. Compared with a selective channel strategy, a parent company tends to hire national in a host country to head a sales subsidiary if an intensive channel strategy is adopted.

Thus, we can derive a general proposition for the appointment of a country manager for a foreign sales subsidiary:

subsidiary located in a developed country by a parent firm from a developing country.

Proposition 2: Subsidiary factors affect the staffing decision of a country manager for a sales subsidiary located in a developed country by a parent firm from a developing country.

Proposition 3: Host country factors affect the staffing decision of a country manager for a sales subsidiaries located in a developed country by a parent firm from a developing country.

Proposition 4: Personal factors affect the staffing decision of a country manager for a sales subsidiary located in a developed country by a parent firm from a developing country.

CONCLUSION

As more and more firms from developing countries become internationalized, setting up sales subsidiaries in developed countries is gaining strategic importance, so does the importance of managing foreign sales subsidiaries. Due to insufficient research regarding foreign sales subsidiaries, we have limited knowledge about how they are setting up and how they are managed. For instance, location selection/entry mode and appointment of country manager are all categorized as the fields of international business and international human resource management; the main function of a sales subsidiary belongs to international marketing management. In fact, only a few studies have focused on the actual operations of foreign subsidiaries in host countries, especially in developed countries. Thus, this study aims to base on a more holistic perspective to explore the issues regarding the staffing of country managers for sales subsidiaries and the process and functions of sales subsidiaries in developed countries for firms from

developing countries (i.e., upstream FDI).

The case findings of the four companies based in Taiwan can shed some light on the understanding of upstream investment and operations of sales subsidiaries overlooked by previous literature. We hope that the four propositions derived can be further refined for empirical test. Our findings are also helpful to practitioners. We show them how to make the decisions when setting up foreign sales subsidiaries are considered, how to structure foreign sales subsidiaries, and how to manage distributors in developed countries.

We caution the readers to read our paper with the following limitations in mind: (1) limitation on generalization to other industries: all companies examined were in high-tech industries and whether the findings are applicable to other industries need further study; (2) limited cases examined: four sales subsidiaries in developed countries were examined only for a few issues and more detailed country-focused studies are needed to have deeper understanding of sales subsidiaries; and (3) the inter-relationships among decisions (variables) are more complex than examined: several variables, such as motivation for investment, choice of entry mode, appointment of country manager, channel management, etc. are related and a more comprehensive framework is needed for examining the relationships among these variables. The three limitations can be examined further in future studies.

REFERENCES

Agmon, T. and Kindleberger, C. (eds.) (1977), Multinationals from Small Countries, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Andersson, T. and Svensson, R. (1994), “Entry Modes for Direct Investment Determined by the Competition of Firm-Specific Skills,” Scand. J. of Economics, 96(4), 551-560.

Bebenroth, R., Li, D. and Sekiguchi, T. (2008), “Executive Staffing Practice Patterns in Foreign MNC Affiliates Based in Japan,” Asian Business and Management, 7, 381-402.

Belderbos, R. A. and Heijltjes, M. G. (2005), “The Determinants of expatriate Staffing by Japanese Multinationals in Asia: Control, Learning and Vertical Business Groups,” Journal of International

Business Studies, 36(3), 341-354.

Bird, A., Taylor, S. and Beechler, S. (1998), “ATypology of International Human Resource Management In Japanese Multinational Corporations: Organizational Implications,” Human Resource Management, 37(2), 159-172.

Brouthers, K. D. and Brouthers, L. E. (2000), “Research Notes and Communications Acquisition or Greenfield Start-Up? Institutional, Cultural and Transaction cost Influences,” Strategic Management

Journal, 21, 89-97.

Brown, J. R. and Day, R. L. (1981), “Measures of Manifest Conflict in Distribution Channels,” Journal of

Marketing Research, 18, 263–274.

Cavusgil, S. T. Deligonul, S., and Zhang, C. (2004), “Curbing Foreign Distributor Opportunism: An Examination of Trust, Contracts, and the Legal Environment in International Channel Relationships,”

Journal of International Marketing, 12(2), 7–27

Chang, Y.Y., Mellahi, K., and Wilkinson, A. (2009), “Control of Subsidiaries of MNCs from Emerging Economies in Developed Countries: The Case of Taiwanese MNCs in the UK,” International Journal

of Human Resource Management, 20(1), 75-95.

Chen, H. and Chen, T. (1998), “Network Linkages and Location Choice in Foreign Direct Investment,”

Journal of International Business Studies, 29(3), 445-468.

Wise. (in Chinese)

Colakoglu, S. and Caligiuri, P. (2008), “Cultural Distance, Expatriate Staffing and Subsidiary

Performance: The Case of US Subsidiaries of Multinational Corporations,” The International Journal

of Human Resource Management, 19(2), 223-239.

Davis, P. S., Desai, A. B., and Francis, J. D. (2000), “Mode of International Entry:An Isomorphism Perspective ,” Journal of International Business Studies, 31, 239-258.

Delios, A. and Bjorkman, I. (2000), “Expatriate Staffing in Foreign Subsidiaries of Japanese Multinational Corporations in the PRC and the United States,” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 11(2), 278-293.

Dowling, P. J., Welch, D. E. and Schuler, R. S. (1999), International human resource management:

Managing people in a multinational context. 3 ed., Ohio: South- Western College Publishing.

Edström, A. and Galbraith, J. (1977), “Transfer of Managers as a Coordination and Control Strategy in Multinational Organizations,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 22, 248-163.

Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989), “Building Theories from Case Study Research,” Academy of Management

Review, 14(4), 532-550.

Frazier, G.L. and Antia, K.D. (1995), “Exchange Relationships and Interfirm Power in Channels of Distribution,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 23, 321-326.

Gorchels, L., Edward, M. and Chuck, W. (2004), The Manager’s Guide to Distribution Channels.1st

ed.,New York, N.Y.: McGraw Hill Companies,Inc.

Gupta, A. and Govindarajan V. (1991), “Knowledge Flows and the Structure of Control within Multinational Corporations,” Academy of Management Review, 16, 768-792.

Harvey, M. G. (1985), “The Expatriate Family: An Overlooked Variable in International Assignments,”

Columbia Journal of World Business, 20, 84-92.

Harzing, A. W. K. (2001), “Who’s in Charge: An Empirical Study of Executive Staffing Practices in Foreign Subsidiaries,” Human Resource Management, 40(2), 139-158.

Heenan, D.A. and Keegan, W.J. (1979), “The Rise of Third World Multinationals,’ Harvard Business

Hymer, S. (1976). The International Operations of National Firms: A Study of Foreign Firect Investment, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Hultink, E.J. and Atuahene-Gima, K.(2000), “The Effect of Sales Force Adoption on New Product Selling Performance,” Journal of Product Innovation Management, 17(6), 435-450.

Kasulis J.J., Morgan F.W., Griffith D.E. and Kenderdine J.M. (1999), “Managing Trade Promotions in the Context of Market Power,” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(3), 320-332. Kasulis, J. J. and Spekman, R. E. (1980), “A Framework for the Use of Power,” European Journal of

Marketing, 14, 180-191.

Kim, K and Oh, C. (2002), “On Distributor Commitment in Marketing Channels for Industrial Products: Contrast Between the United States and Japan,” Journal of International Marketing, 10(1), 72–97. Khoury, S.J. (1979), “International Banking: A Special Look at Foreign Banks in the US”, Journal of

International Business Studies, 10(3), 36-52.

Kogut, B. and Singh, H.(1988), “The Effect of National Culture on the Choice of Entry Mode,”

Journal of International Business Studies, 19, 411-432.

Konopaske, R., Werner, S. and Neupert, K. E. (2002), “Entry Mode Strategy and Performance: The Role of FDI Staffing,” Journal of Business Research, 55, 759-770.

Kotler, Philip and Keller, Kevin (2006), Marketing Management:Analysis, Planning, Implementation, and Control, 12th ed., New Jersey: Prentice Hall.

Kumar, K. and McLeod, M.G. (eds.) (1981), Multinationals from Developing Countries, Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath.

Kwok, C. C. Y. and Reeb, D. M. (2000), “Internationalization and Firm Risk: An Upstream-Downstream Hypothesis,” Journal of International Business Studies, 31, 611-629.

Luo, Y. (2000), “Dynamic Capabilities in International Expansion,” Journal of World Business, 35, 355– 378.

Makino, S., Lau, C. and Yeh, R. S. (2002), “Asset Exploitation versus Asset Seeking: Implications for Location Choice of Foreign Direct Investment,” Journal of International Business Studies, 33(3), 403-421.

Naumann, E. (1992), “A Conceptual Model of Expatriate Turnover,” Journal of International Business

Studies, 3, 491-531.

O’Brien, P. (1980), “The New Multinationals: Developing Country Firms in International Markets,’

Futures, 12, 4, 303–316.

Prahalad, C. K. and Doz, Y. L. (1981), “An Approach to Strategic Control in MNCs,” Sloan Management

Review, 22(4), 5-13.

Rosenbloom, B. (1999), Marketing Channels: A Management View, 6thed., New York: Dryden Press.

Rugman, A.M. (1982), New Theories of the Multinational Enterprise. New York: St. Martin’s Press. Schotter, A. & Beamish, P. W. (2011), “General Manager Staffing and Performance in Transitional

Economy Subsidiaries: A Subnational Analysis,” The International Studies of Management and

Organization, 41(2), 55-87.

Scullion, H. and Collings, D. (2006), Global staffing, London: Routledge.

Shaffer, M. A., Harrison, D. A. and Gilley, K. M. (1999), “Demisions, Determinants, and Difference in the Expatriate Adjustment Process,” Journal of International Business Studies, 30, 557-581.

Tarique, I., Schuler, R., and Gong, Y. (2006), “A model of Multinational Enterprise Subsidiary Staffing Composition,” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(2), 207-224.

Thomas, D.E., Eden, L. and Hitt, M.A. (2002), “Who Goes Abroad? International Diversification by Emerging Market Firms into Developed Markets,” Paper presented at the Academy of Management Annual Meeting at Denver, CO.

Tsang, E. W. K. (1999), “The Knowledge Transfer and Learning Aspects of International HRM: An Empirical Study of Singapore MNCs,” International Business Review, 8, 591-609.

Tseng, C. and Liao, Y. (2009), “Expatriate CEO Assignment: A study of Multinational Corporations’ Subsidiaries in Taiwan. International Journal of Manpower, 30(8), 853-870.

Wang, C. Y. P., Jaw, B., and Huang, C. (2008), “Towards a Cross-Cultural Framework of Strategic International Human Resource Control: The Case of Taiwanese High-Tech Subsidiaries in the USA,”

The International Journal of Human Resource Management,19(7), 1253-1277.

Wederspahn, G. M. (1992), “Costing Failures in Expatriate Human Resources Management,” Human

Widmier, S., Brouthers, L. E., and Beamish, P. W. (2008), “Expatriate or Local? Predicting Japanese’ Subsidiary Expatriate Staffing Strategies,” The International Journal of Human Resource

Management, 19(9), 1607-1621.

Woodcock, C. P., Beamish, P. W., and Makino, S. (1994), “Ownership-Based Entry Mode Strategies and International Performance,” Journal of International Business Studies, 25, 253-273.

Yin, R. K. (1994), Case study research: design and methods, Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Yu, C. J. and Liao, T. (2005), “ Determinants of the Selection of Controlling Mechanisms for Foreign Subsidiaries: The Case of Taiwanese Firms,” Chiao-Da Management Review, 25(2)27-56. (in Chinese) Yu, C. J. and Tang, M. (1992), “International Joint Ventures:Theoretical Considerations,” Managerial

and Decision Economics, 13, 331-342.

Zejan, M. C. (1990), “New Ventures or Acquisitions: The Choice of Swedish Multinational Enterprises,”

TABLES

Table 1 Location of foreign sales subsidiaries of 10 leading Taiwanese brands (firms)

Company Industry US Europe Other DCs LDCs Total

HTC Consumer electronics 2 (8%) 9 (36%) 5 (20%) 9 (36%) 25 (100%) Acer Consumer electronics 3 (4%) 42 (58%) 9 (13%) 18 (25%) 72 (100%) Asus Consumer electronics 5 (13%) 14 (37%) 6 (16%) 13 (34%) 38 (100%) TrendMicro software 2 (9%) 6 (26%) 6 (26%) 9 (40%) 23 (100%) Master Kong Food &

beverage

- - - All in China

(100%)

548 (100%) Want-Want Food &

beverage - - 2 (40%) 3 (60%) 5 (100%) Giant Bicycle 2 (13%) 6 (40%) 3 (20%) 4 (27%) 15 (100%) Maxxis Tire &

rubber 2 (17%) 4 (33%) 1 (8%) 5 (42%) 12 (100%) Synnex IT product distributor -- -- 3 (20%) 12 (80%) 15 (100%) Advantech Computer hardware 3 (18%) 3 (29%) 4 (24%) 5 (29%) 17 (100%)

25

Company A Company B

Established time of headquarters

1979 2002

Core products Labelers and bio-pharmaceutical machinery

Commercial and home-use projectors

Revenue in 2010 NT$ 206 million NT$ 3,763 million

Time setting up the salesMotivation of entry The US, 1997 UK, 2002 The biggest consumer market

with derived demand for labelers

The biggest market for LCD projectors with high-income

level

Entry mode Acquisition Acquisition

Activities before salesubsidiaries establishment

1. Evaluation of market potential of several countries 2. Local market research 3. Evaluation of financial capability

4. Evaluation of entry mode

1. Evaluation market potential of several countries

2. Local market research 3. Evaluation of financial capability

4. Evaluation of entry mode Background of the first GM American, founder of the U.S.

agent

Taiwanese, expatriate from Taiwan

Background of current GM America, locally promoted Breton, locally promoted The considerations of hiring the

1stGM

Parent company factors: 1. Insufficient

international talents a t the HQs

2. Difficulty in recruiting in the US Host country factors 1. The concern for local

Parent company factors 1. Relying someone the HQs can trust due to lack of auditing

capability and system 2. Needing someone who understands the HQs well and

can communicate with HQs easily

23

Table 2 Case Summary for Company A and B government regulations, etc., is

needed for business expansion Subsidiary factors Critical

to build nation-wide distribution channels Personal factors The founder of the US agent had industrial experience and illustrated positive cooperative

behaviors during previous transactions.

1. Higher cost of local managers

2. Limited number and smaller size of local distributors

Subsidiary factors Strategic importance of the

subsidiary Personal factors The CM had been working at

the HQs for years and understood the culture, products and business model of

Managing Channels by Foreign Sales Subsidiaries: The Case of Firms from Developing Countries Operating in Developed Countries

ABSTRACT

Many firms from developing countries (LDCs) have engaged in foreign direct investment (FDI). Interestingly, some firms locate their investments in developed countries (DCs) (i.e., upstream FDI), instead of in countries economically similar to or less than their home countries (i.e., downstream FDI). However, only a few researchers have examined issues related to upstream FDI. Furthermore, when examining FDI, most studies have focused on manufacturing subsidiaries instead of sales subsidiaries. Using a case study approach by focusing on the behaviors of Taiwanese firms, we address two research questions: (1) what are the channel strategies adopted by sales subsidiaries of Taiwanese high- tech firms (i.e., LDCMNCs) in DCs? , and (2) how do these s u b s i d i a r i e s manage their channels in DCs? Our findings show that: (1) LDCMNCs tend to use multiple sales channels, to work with large national distributors, and to adopt high touch channels to market products; (2) to reduce channel conflict, less powerful LDCMNCs adopt multiple independent channel systems; and (3) due to limited resources, LDCMNCs try to design channel conflict prevention mechanisms, emphasize more on building distributors-relationships and use financial/high-power incentives to motivate distributors.

INTRODUCTION

Although the presence of multinational corporations (MNCs) from developing countries (LDCs) has long been reported (Agmon & Kindleberger, 1977; Heenan & Keegan, 1979; Kumar & McLeod, 1981; O’Brien, 1980), relatively little research has been conducted on how these firms operate in developed countries (DCs). Studies on FDI and management of foreign subsidiaries by MNCs from DCs (DCMNCs) can be classified based on the level of a host country’s economic development as either horizontal FDI if a host country is a DC or downstream FDI if a host country is a LDC. In recent years, the emergence of MNCs from LDCs (LDCMNCs) (e.g., HTC Corporation and ASUSTeK Computer Inc., two firms based in Taiwan) has again raised the attention of academics, particularly on how they enter DCs and compete in DCs. Figure 1 illustrates the types of FDI based on the location of a host county and the home country of a MNC. DCMNCs engage in horizontal F D I a n d d o w n s t r e a m F D I w h i l e LDCMNCs engage in horizontal FDI and upstream FDI. Downstream FDI refers to MNCs conducting investment in countries with lower degree of economic development comparing with their home countries, while upstream FDI means that MNCs conducting investment in countries with higher degree of economic development

comparing with their home countries (Kwok & Reeb, 2000; Makino, Lau, & Yeh, 2002). For upstream FDI, however, LDCMNCs encounter dual problems, namely, liability of foreignness (Hymer, 1967) and liability of country of origin (Chang, Mellahi & Wilkinson, 2009). Hence, applying previous understanding of DCMNCs to LDCMNCs seems inappropriate.

Most research in international business do not distinguish between manufacturing subsidiaries and sales subsidiaries (Belios & Bjorkman, 2000; Colakoglu & Caligiuri, 2008). Nevertheless, using sales subsidiaries as research samples remain rare. The motivations of investment, capital needed, roles and functions of subsidiaries as well as management of subsidiaries should be different. For sales subsidiaries, they may encounter two challenges. First, though low price is an

attraction, products marketed should have some differentiation, especially for industrial users (Yu & Liao, 2005). Second, to market products successfully, the impact of local cultural and social factors should be taken into consideration (Wang, Jaw, & Huang, 2008). These challenges would be more severe for upstream

FDI. Channel of distribution decision plays an essential role in marketing strategy (Rei1980; Dickson, 1983). Channel strategy is particular important in the international context when new entrants who (1) have limited access to traditional host-country distribution or (2) cannot transform their home-country distribution experience to the host country due to cultural differences (Kim & Daniels, 1991; Kim, 1993). With this in mind, the study intends to enhance our understanding of upstream FDI by answering to two questions: how LDCMNCs structure and manage their channels in DCs.

In recent years, many firms from Taiwan have started to market their products internationally. Table 1 shows the distribution of host countries where the 10 leading brands (firms) have sale subsidiaries. It is clear that, except for the two food and beverage firms which mainly serve the Chinese market, most firms have located the majority of their sale subsidiaries in DCs. This reflects the importance of foreign sales

subsidiaries in DCs for firms from Taiwan, a developing country. To summarize, this study addresses the following two research questions by examining the behaviors of Taiwanese firms: (1) what are the channel strategies adopted by the sales subsidiaries of Taiwanese high-tech firms (i.e., LDCMNCs) in DCs? , and (2) how do these subsidiaries manage their channels in DCs? It is hoped that the research findings would contribute to current understanding of upstream investment theoretically and provide operational guidelines for firms from LDCs intending to expand sales in DCs.

We organize the paper as follows: the first section introduces the background of the paper and the research questions; the second section reviews the literature; the third section describes the

research methodology; the fourth section reveals and discusses the research findings; and the last section concludes the paper.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Managing marketing mix is important to firms. Among product, price, place and distribution, channel management is particular challenging for sales subsidiaries in host countries. Marketing channel or

distribution channel can be regarded as the process of transferring particular products or services from producers to consumers (EI-Ansary & Stern, 1972). Two general research areas of marketing channels

(Frazier, Sawhney, & Shervani, 1990); one relates to the structure of a channel, answering the question of how the channel is generally organized to fulfill its basic purpose of creating value for a firm’s customers, while the other relates to the behavior dimensions of the channel, addressing the question of how channel members perceive, build, and deal with inter-firm relationships that exist within channel.

Channel Structure

In early days, most academics applied the transaction cost theory (TCE) to discuss “make- or-buy” issues (Coase, 1937; Williamson, 1979; Williamson, 1981). The TCE argues that when making the

make-or-buy decision, firms need to take into account both the sales volume and possibility of being taking advantage by others firms, into consideration. Anderson and Coughlan (1987) and Kim and Daniels (1991) pointed out that ownership of transaction-specific assets, service requirements, product differentiation, cultural similarly would be more likely for a manufacturer to adopt a direct selling approach. Some studies followed a functional approach and claimed that distributors in host countries are in a better position to fulfill contact efficiency function, information providing function and customer service function. While the TCE perspective does not consider the marketing capacity of external distributors, the functional

approach reduces validity when transaction cost issues are concerned. Kim (2001) proposed to integrate both the TCE and functional approach in order to increase explanatory power.

With the advent of the Internet, multichannel strategies have become one of the popular means in B2B marketing. Multichannel strategies help firms to interact with clients. B2B marketers often adopt

multichannel strategies (Moriarty & Moran, 1990) while customers choose the channels to fulfill their needs by their own preferences (Sharma & Mehrotra, 2007). Several advantages of multichannel strategies include increasing number of potential clients, p r o v i d i n g better customer services and generating higher levels of satisfaction (Moriarty & Moran, 1990). Notwithstanding these benefits, multichannel strategy may also incur disadvantages including channel conflict. Multichannel strategy contains numerous modes, for

examples, using vertical integration (i.e., direct sales) and independent distribution concurrently (i.e., termed dual channel system) or only using several types of independent distributors (e.g., distributors for medical

devices and farm machinery) to serve different types of customers (e.g., clients in medical and agricultural sectors) concurrently (termed multiple independent channel system) (Dutta, Bergen, Heide, & John, 1995; Gabrielsson, Kirpalani, & Luostarinen, 2002; Hardy & Magrath, 1988, pp. 15-22; Kabadayi, 2011). Kabadayi (2011) uses the TCE perspective to explain why some manufacturers adopt dual channel systems while others choose multiple independent channel system. Dual channel system enables manufacturers to prevent independent distributors to take advantages of them due to lock-in effect and opportunism and thus it provides safeguard for manufactures. To summarize, dual channel system helps manufacturers to gather all pieces of useful information and use them to evaluate the performance of independent channel members as well as to control the behaviors of channel members. Bergen and Heide (1995) show that dual channel system assists firms in resolving channel conflict more swiftly and transmitting information more effectively between integrated channel and independent channel. However, Habrielsson, Kirpalani and Luostarinen (2002) hold an opposite view. They argue that dual channel system, in fact, heats up the competition

between manufacturers and distributors. They suggest that dual channel strategy would be more appropriate when manufactures have more bargaining power. Channel intermediaries are another consideration when manufacturers consider an indirect sales approach. In selling personal computers, channel intermediaries include wholesalers, resellers, and retailers. Resellers can be dealer chains (or corporate resellers), local dealers, indirect fax, telephone or Internet resellers and value-added resellers; retailers can be PC superstores, PC stores and general merchandising stores. Firms determine the types of channel intermediaries based on the size of their customers. Firms use small dealers or distributors for small customers, sales force or value-added resellers for medium-sized consumers, and key account sales force for larger clients (Sharma

& Mehrotra, 2007). Wholesalers often purchase large amount of products from manufacturers with the hope to receive special discount from list prices and sell to their customers. Valued -added Resellers (VARs) request product discount from manufacturers and add value to already existing solutions. Different from the two, system integrators (SIs) hire technical specialists to solve customers’ problems in some specific markets. SIs buy products directly from wholesalers or manufacturers. Often, manufacturers need to persuade SIs to purchase their products because SIs operate in some regions that manufacturers have

difficulty to enter. When doing business with SIs, fixed prices are always guaranteed by manufacturers as the development of solution for particular customers takes months even years to complete.

Each channel member provides distinctive value -added activities. For instance, Taiwanese high- tech firms use wholesalers, VARs and SIs as their main distribution channels. In the information technology industry, different distributors play different functions: wholesales have professional and technical personnel and they possess software services and data processing capabilities; VARs integrate software and hardware to solve the specific needs of a particular customer and thus provide end-users “one-stop shopping service”; and SIs are similar to VARs but offer professional services for complex, system-oriented or

solution-oriented products (Gorchels, Edward, & Chuck, 2004). However, “intermediary types” have various definitions depending on the industries or even the customers. Therefore, firms should pay attention to the functions or services offered by each intermediary instead of how it is called. According to Friedman and Furey (1999), the more complex a product, the greater degree for manufacturers to adopt “high t o u c h channels” (e.g., distributors, VARs, and direct sales force). High touch channels define as channels that can provide quality service and support to the needs of end-customers. Comparing with high touch channels, low touch channels (e.g., the internet, telemarketing, and retail stores) cost less but offer lower degree of interaction with customers (Friedman & Furey, 1999).

Channel Management

Channel management is an activity a MNC needs to engage after it determines its channel structure in a foreign market. A foreign firm needs to persuade channel members to perform certain sales and service activities so that its goals in a host market can be achieved. There is an extensive literature on channel management addressing several issues such as incentives, power, conflict and cooperation (EI-Ansary & Stem, 1972; Gaski, 1984; Gassenheimer, Sterling, &

Robicheaux, 1996; Hunt & Nevin, 1974; Rawwas, Vitell, & Bernes, 1997). This study will focus on conflict, relationship and incentives.

Conflict

Conflict management has long been considered as one important issue in channel behavior research. Levy (1981) holds that “the concept of conflict is central to marketing channel management”. Channel conflict is defined as a perceived situation in which the goals of distributors and manufacturers are not congruent (Etgar, 1979; Gaski,1984). It is manifested when two parties cannot make mutual agreement toward problems (Brown & Day, 1981). Without settling down the issue, channel cooperation, satisfaction, and performance would be affected (Duarte & Davies, 2003; Magrath & Hardy, 1989; Rosenbloom, 1973). Rosenbloom (1973) believes that conflict can have both advantages and disadvantages. While the former can stimulate management to review channels policies and activities, the latter reduces th e efficiency of distribution and lowers the performance of manufacturers. Kolter and Keller (2006) categorize three types of channel conflict: (1) horizontal channel conflict indicating conflict that members in the same channel level encounter; (2) vertical channel conflict referring to conflict that members in different channel levels face; and (3) multichannel conflict which is caused by having multiple distribution channels in the same market. Goal incompatibility, role incongruence, resource scarcity, perceptual difference in realities, expectation differences, decision domain disagreements, and communication difficulties have been identified as the causes of channel conflict (Cadotte & Stem, 1979; Etgar, 1979; Stem, EI-Ansary, & Coughlan, 1996). Magrath and Hardy (1989) indicate that channel length, variety and density are associated with conflicts: (1) channel length: conflict decreases when manufacturers have shorter channel length; (2) channel variety (single/dual/multiple): conflicts are lower for single channel or multiple channels with each channel member possessing distinctive competences; and (3) channel density (exclusive/selective/intensive): compared with exclusive and intensive channels, channel conflicts would be higher for selective channels because they generate greater uncertainty and a sense of territorial infringement among distributors. Magrath and Hardy (1989) further enumerate the conflict zones regarding to the channel design of manufacturers by pointing firms should adopt different ways to manage conflicts. . For instance, dual channel system is in the zone of high conflict and short channel length is in the zone of low conflict.

Relationship.

Friedman (2002) indicates that due to the complexity of multi-channels nowadays, firms attempt to reduce channel conflict always comes apart. Therefore, building and managing relationship is gaining importance. Channel cooperation is a joint effort with voluntary actions of members at different levels to achieve objectives mutually (Sibley & Michie, 1982; Skinner, Gassenheimer, & Kelley, 1992). A healthy cooperative relationship often brings benefits along, for examples, raising internal capabilities, and assisting members solve conflicts (Mehta, Larsen, & Rosenbloom, 1996). Moriarty and Kosnik (1987) recommend that manufacturers in high-tech industries need to build relationships with channels and customers. McKenna (1987) further expands their view and stresses that developing relationships can overcome fear, uncertainty and doubt (FUD) among channels. Morgan and Hung (1994) note that relationship marketing seems as an effective tool for partners to build long-term relationships. Relationship marketing indicates to “all marketing activities directed towards establishing, developing, and maintaining successful relational exchanges.” Studies have shown that relationship marketing actually helps manufacturers and distributors developing a stronger relationship and influences performance positively (Crosby, Evans, & Cowles, 1990; Morgan & Hun, 1994). A strong brand gives bargaining power to a manufacturer in B2B business (Glynn, 2010) and distributors tend to be cooperative (Kasulis, Morgan, Griffith, & Kenderdine, 1999). On the contrary, a weaker brand means that a manufacturer has to rely on deals to win the cooperation from distributors (Curhan & Kopp, 1987). From the resource-based view (RBV), brands undoubtedly can be considers as a market-based asset which creates relational rents from external business partners. For distributors, brands raise customer needs, increase sales volume and profit, and generate useful market information. The influence of brand has been studied extensively in the consumer literature (e.g. Krishnan, 1996) but only a few researchers pay attention to B2B context. To B2B buyers, brands can serve as a mechanism of risk reduction. Risk reduction is more important when a purchase is complicated and need additional services and supports (e.g., purchasing high-tech products) (Mudambi, 2002). Consequently, a manufacturers’ strong brand not only creates transactional value and reduces risk, but also increases the level of value expectation of buyers (McQuiston, 2004). In addition, strong inter- firm relationship helps