Statin Use and the Risk of Pancreatic Cancer

A Population-Based Case-Control Study

Hui-Fen Chiu, PhD,* Chih-Ching Chang, MD, PhD,Þ Shu-Chen Ho, MS,þ Trong-Neng Wu, PhD,§||

and Chun-Yuh Yang, PhD, MPH||¶

Objectives:The aim of this study was to investigate whether the use of statins was associated with pancreatic cancer risk.

Methods: We conducted a population-based case-control study in Taiwan. Data were retrospectively collected from the Taiwan National health Insurance Research Database. Cases consisted of all patients who were 50 years or older and had a first-time diagnosis of pancreatic cancer for the period between 2003 and 2008. The control subjects were matched to cases by age, sex, and index date. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated by using multiple logistic regression.

Results:We examined 190 pancreatic cancer cases and 760 control subjects. The unadjusted OR for any statin prescription was 1.07 (95% CI, 0.72Y2.06), and the adjusted OR was 0.87 (95% CI, 0.56Y1.36). Compared with no use of statins, the adjusted ORs were 1.06 (95% CI, 0.61Y1.85) for the group having been prescribed statins with cumulative defined daily doses less than 114.33 and 0.71 (95% CI, 0.39Y1.30) for the group with cumulative statin use of 114.33 defined daily doses or more. Conclusions: This study does not provide support for a beneficial association between usage of statin and pancreatic cancer.

Key Words: pharmacoepidemiology, statins, pancreatic cancer, case-control study

(Pancreas 2011;40: 669Y672)

S

tatins are inhibitors of 3-hydroxy-3-methyl glutaryl coen-zyme A reductase, which is a key encoen-zyme in the rate-limiting step in cholesterol synthesis.1 Statins are commonly used as cholesterol-lowering medications and have shown effectiveness in the primary and secondary prevention of heart attack and stroke.2,3The extensive evidence has led to widespread use ofthese drugs.

Rodent studies indicate that statins are carcinogenic.4 In contrast, several recent studies of human cancer cell lines

and animal tumor models indicate that statins may have che-mopreventive properties through the arresting of cell cycle pro-gression,5 inducing apoptosis,1,6 suppressing angiogenesis,7,8

and inhibiting tumor growth and metastasis.9,10Results of

meta-analysis and observational studies revealed either no asso-ciation11Y18 or even a decreased cancer incidence.19Y27 The

reasons for the varying results are unclear but may relate to methodological issues, including small sample size and short follow-up periods.28

Statins are generally well tolerated and have a safe side effect profile, with the most concerning adverse effects being hepato-toxicity and myohepato-toxicity.29 Few epidemiologic studies have in-vestigated the association between statin use and risk of pancreatic cancer. Four studies reported a statistically nonsignificant inverse association between statin use and pancreatic cancer risk.11,13,18,21

A recent nested case-control study, however, found that statin use is associated with a significant reduction in the risk of pancreatic cancer among half a million veterans.26

Because a large number of people use statins on a long-term basis, and because epidemiologic evidence for a link between statin use and risk of pancreatic cancer is limited, we undertook the present study in Taiwan to evaluate the association between statin use and pancreatic cancer risk.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Data Source

The National Health Insurance (NHI) program, which pro-vides compulsory universal health insurance, was implemented in Taiwan on March 1, 1995. Under the NHI, 98% of the island’s population receives all forms of health care services including outpatient services, inpatient care, Chinese medicine, dental care, childbirth, physical therapy, preventive health care, home care, and rehabilitation for chronic mental illness. In cooperation with the Bureau of NHI, the National Health Research Institute (NHRI) of Taiwan randomly sampled a representative database of 1,000,000 subjects from the entire NHI enrollees by means of a systematic sampling method for research purposes. There were no statistically significant differences in age, sex, and health care costs between the sample group and all enrollees, as reported by the NHRI. This data set (from January 1996 to December 2008) includes all claim data for these 1,000,000 subjects and offers a good opportunity to explore the relation between the use of statins and risk of pancreatic cancer. This database has previously been used for epidemiological research, and information on prescrip-tion use, diagnoses, and hospitalizaprescrip-tions has been shown to be of high quality.30Y32

Because the identification numbers of all individuals in the NHRI databases were encrypted to protect the privacy of the individuals, this study was exempt from full review by the institutional review board.

Identification of Cases and Control Subjects

Cases consisted of all patients who were aged 50 years or older and had a first-time diagnosis of pancreatic cancer

O

RIGINAL

A

RTICLE

Pancreas

&

Volume 40, Number 5, July 2011 www.pancreasjournal.com669

From the *Institute of Pharmacology, College of Medicine, KaohsiungMedical University, Kaohsiung; †Department of Environmental and tional Health, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan; ‡Institute of Occupa-tional Safety and Health, College of Health Sciences, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung; §Graduate Institute of Environmental Health, China Medical University, Taichung; ||Division of Environmental Health and Occu-pational Medicine, National Health Research Institute, Miaoli; and ¶Faculty of Public Health, College of Health Sciences, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan.

Received for publication November 22, 2010; accepted January 5, 2011. Reprints: Chun-Yuh Yang, PhD, MPH, Faculty of Public Health, Kaohsiung

Medical University, 100 Shih-Chuan 1st Rd, Kaohsiung, Taiwan 80708 (e-mail: chunyuh@kmu.edu.tw).

This study is based in part on data from the National Health Insurance (NHI) Research Database provided by the Bureau of NHI, Department of Health, and managed by the National Health Research Institute. The interpretation and conclusions contained herein do not represent those of Bureau of NHI, Department of Health, or National Health Research Institute. This study was partly supported by a grant from the National Science Council, Executive Yuan, Taiwan (NSC-96-2628-B-037-039-MY3).

Copyright* 2011 by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

(International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clin-ical Modification code 157) over a 6-year period, from January 1, 2003, to December 31, 2008, and who had no previous diagnosis of cancer.

Control subjects comprised patients who were admitted to the hospital for diagnoses that were unrelated to statin use in-cluding orthopedic conditions, trauma (exin-cluding wrist and hip fractures), and other conditions (acute infection, hernia, kidney stones, cholecystitis).13,33

Wrist and hip fractures were excluded because previous studies have reported a reduced risk of osteo-porosis among statin users.34Y37We identified 4 control patients per case patient. Control patients were matched to the cases by sex, year of birth, and index date, and they were without a pre-vious cancer diagnosis. For control subjects, the index date (date of hospital admission) was within the same month of the index date (date of first-time diagnosis of pancreatic cancer) of their matched case. Under the conditions of detecting an odds ratio (OR) of 0.5 with 80% power at the 5% significance level, 20% of the population aged 50 years or older is statin users and that a control-to-case of 4 is planned; the minimum number of cases required was estimated to be 169.

Exposure to Statins

Information on all statin prescription was extracted from the NHRI prescription database. We collected the date of pre-scription, the daily dose, and the number of days supplied. The defined daily doses (DDDs) recommended by the World Health Organization38were used to quantify usage of statins. For each year of the study period, the cumulative usage (in milligrams) for each statin was calculated based on all prescription dis-pensed in that year. The yearly usage was divided with the quantity corresponding to 1 DDD. Cumulative DDDs were estimated as the sum of dispensed DDD of any statins (lovastatin, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, fluvastatin, simvastatin, or atorvastatin) from January 1, 1996, to the index date.

Potential Confounders

For all individuals in the study population, we obtained potential confounders that are documented risk factors for pancreatic cancer, including diabetes mellitus (code 250) and chronic pancreatitis (code 577.1),39recorded between January 1, 1996, and index date. In addition, we also obtained pre-scription data for other lipid-lowering drugs (including fibrate, niacin, bile-acidYbinding resins, and miscellaneous) and med-ications that potentially could confound the association be-tween statin use and cancer risk. We defined users of the previously mentioned medications as patients with at least 1 prescription over 1 year before index date. Furthermore, the number of hospitalizations 1 year before index date was treated as a confounder.

Statistics

For comparisons of proportions, McNemar W2 statistics were used. A conditional logistic regression model was used to estimate the relative magnitude in relation to the use of statins. Exposure was defined as patients who received at least 1 pre-scription for a statin at any time between January 1, 1996, and the index date. In the analysis, the subjects were categorized into 1 of the 3 statin exposure categories: nonusers (subjects with no prescription for any statins at any time between January 1, 1996, and the index date), users of doses equal to or less than the median, and users of doses greater than the median based on the distribution of use among control subjects. Odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using patients with no exposure as the reference. Analyses were performed using the SAS statistical package (version 8.02; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). All statistical tests were 2-sided. PG 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

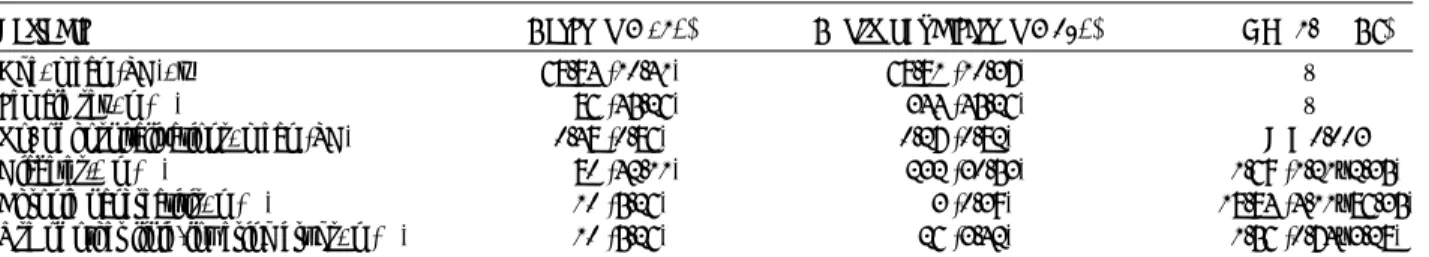

Records from 190 pancreatic cancer cases and 760 selected matched control subjects are included in the analyses of pan-creatic cancer risk. Table 1 presents the distribution of demo-graphic characteristics and selected medical conditions of the pancreatic cancer cases and control subjects. The mean ages were 68.84 years for pancreatic cancer cases and 68.81 years for the control subjects. The pancreatic cancer case group had a significantly higher rate of diabetes and chronic pancreatitis. Use of other lipid-lowering drugs was not significantly different be-tween patients and control subjects (5.25% vs 3.42%).

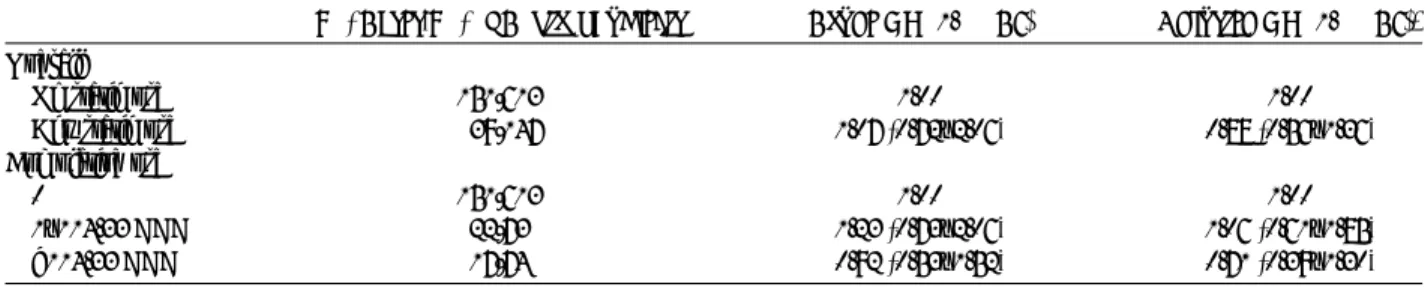

The relationship between the use of statins and pancreatic cancer is shown in Table 2. The prevalent use of any statin was similar in pancreatic cancer cases and control subjects (crude OR, 1.07; 95% CI, 0.72Y2.06). After adjustments for possible confounders (matching variables, diabetes, chronic pancreatitis, number of hospitalizations, and use of other lipid-lowering drugs), patients who received any prescriptions of statins had a 13% reduction in risk of pancreatic cancer compared with nonusers (adjusted OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.56Y1.36). When statin use was categorized by cumulative dose, the adjusted ORs were 1.06 (95% CI, 0.61Y1.85) for the group with cumulative statin use less than 114.33 DDDs and 0.71 (95% CI, 0.39Y1.30) for the group with cumulative statin use of 114.33 DDDs or more compared with nonusers. No association was found between cumulative statin use and pancreatic cancer risk.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based case-control study, we found that statin drug use was not associated with the risk of pancreatic cancer. Our findings are consistent with 4 recent studies that

TABLE 1. Demographic Characteristics of Pancreatic Cancer Cases and Control Subjects

Variable Cases (n = 190) Control Subjects (n = 760) OR (95% CI) Age, mean (SD), y 68.84 (10.41) 68.81 (10.37) V Female sex, n (%) 86 (45.26) 344 (45.26) V No. of hospitalizations, mean (SD) 0.48 (0.86) 0.27 (0.82) P = 0.003 Diabetes,* n (%) 80 (42.11) 232 (30.53) 1.69 (1.21Y2.35) Chronic pancreatitis, n (%) 10 (5.26) 3 (0.39) 18.84 (4.11Y86.35) Use of other lipid-lowering drugs, n (%) 10 (5.26) 26 (3.42) 1.56 (0.74Y3.28)

*Values are expressed as percentage of the presence of underlying comorbidity of diabetes.

Chiu et al Pancreas

&

Volume 40, Number 5, July 2011670

www.pancreasjournal.com * 2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkinsreported no associations between statin use and overall pancre-atic cancer risk.

In a case-control study conducted using the General Prac-tice Research Database in the United Kingdom, Kaye and Jick11 reported an OR of 0.8 (95% CI, 0.4Y1.6) for pancreatic cancer in relation to current statin use. Graaf et al21used a pharmacy

database in the Netherlands to define exposure and observed a similar OR (OR, 0.89; 95% CI, 0.24Y3.34) for pancreatic cancer in relation to statin prescriptions. Data from 3 centers in Phila-delphia, New York, and Baltimore in the United States revealed a modest reduction in pancreatic cancer risk (OR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.3Y1.40) associated with regular statin use, but statistical sig-nificance was not reached.13Recently, Haukka et al18used data from Finland to evaluate statin use and also report no association between statin use and pancreatic cancer risk (relative risk, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.95Y1.02).

Whereas the findings of our study were consistent with the direction of the association (inverse) reported in 4 observational studies,11,13,18,21a study by Khurana et al26found a statistically significant and dramatically stronger association (OR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.30Y0.46). There are at least 2 differences between our study and the study of Khurana et al. First, the study population in the study of Khurana et al consists solely of veterans with active access to health care, and thus, they were more likely to be prescribed a statin than the general population. Statin use was present in 33.8% of the study population. For this study, this number was 19.34%. Second, the previously mentioned study was conducted among a study population that was predomi-nantly male (98.5% of the cases are men). Future studies may want to consider examining whether the protective effect occurs only among males.

The results of our study are consistent with the assumed biologic mechanism of statins, although the mechanism whereby statin use may decrease pancreatic cancer risk is not well under-stood. Several potential mechanisms have been investigated, including the following: (1) inhibiting downstream products of the mevalonate pathway, primary geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) and farnesylpyrophophosphate (FPP).40Y42 Derivatives

of the mevalonate pathway GGPP and FPP are important in the activation of a number of cellular proteins, including small guanosine-5¶-triphosphate-binding proteins, such as K-ras, N-ras, and the Rho family.40Y43 Statins interfere with the production

of GGPP and FPP and disrupt the growth of malignant cells, eventually leading to apoptosis.1(2) Statins inhibit the activation of the proteosome pathway, limiting the breakdown of both p21 and p27, allowing these molecules to exert their growth in-hibitory effects and in turn to retard cancer cell mitosis.10,44,45

One of the strengths of our study is the use of a comput-erized database, which is population based and is highly

repre-sentative. Because we included all patients newly diagnosed with pancreatic cancer from 2003 to 2008, and because the control subjects in this study were selected from a simple random sampling of insured general population, we can rule out the possibility of selection bias. Statins were available only on pre-scription. Because statin use data were obtained from a historical database that collects all prescription information before the date of pancreatic cancer, recall bias for statin use was avoided.

Several limitations of the present study should be noted. First, although we adjusted for several potential confounders in the statistical analysis, a number of possible confounding variables, including body mass index and smoking, which are associated with pancreatic cancer were not included in our database. Second, we were not able to contact the patients di-rectly about their use of statins because of anonymization of their identification number. Using pharmacy records repre-senting dispensing data rather than usage data might have in-troduced an overestimation of statin use. However, there is no reason to assume that this would be different for cases and control subjects. Even if the patients did not take all of the statins prescribed, our findings would underestimate the effect of statin use. Third, lovastatin and pravastatin (available in 1990), simvastatin (available in 1992), and fluvastatin (avail-able in April 1996) became avail(avail-able before patient enrollment in the database. Prescriptions for these drugs before 1996 would not be captured in our analysis. This could have underestimated the cumulative DDDs and may weaken the observed association. In addition, some exposure misclassifi-cation was likely caused by the fact that information on pre-scription was available only since 1996. Such misclassification, however, was likely to be nondifferential, which would tend to underestimate rather than overestimate the association. Fourth, we are unable to separately analyze the risks for users of distinct statins because of the relatively small number of cases and the relatively small number of statin users. Fifth, data on the ac-curacy of discharge diagnoses are not available in Taiwan. Potential inaccurate data in the claims records could lead to possible misclassification. However, there is no reason to assume that this would be different for cases and control sub-jects. Lastly, as with any observational study, residual con-founding by unmeasured factors that are different between cases and control subjects is also possible. However, the con-founding effect of medical attention could be corrected for by introducing the number of hospitalizations into the conditional logistic regression model.

In summary, the results of this study do not provide sup-port for an association between statin use and pancreatic cancer risk. Given the widespread use of statins, it is prudent public health policy to continue monitoring cancer incidence among

TABLE 2. Associations Between Statin use and Pancreatic Cancer Risk in a Population-Based Case-Control Study, Taiwan, 2003Y2008

No. Cases/No. of Control Subjects Crude OR (95% CI) Adjusted OR (95% CI)* Overall

No statin use 151/613 1.00 1.00 Any statin use 39/147 1.07 (0.72Y2.06) 0.88 (0.56Y1.36) Cumulative use

0 151/613 1.00 1.00

1Y114.33 DDD 22/73 1.23 (0.73Y2.06) 1.06 (0.61Y1.85) 9114.33 DDD 17/74 0.92 (0.53Y1.52) 0.71 (0.39Y1.30)

*Adjusted for diabetes, chronic pancreatitis, number of hospitalizations, and use of other lipid-lowering drugs.

Pancreas

&

Volume 40, Number 5, July 2011 Statin and Pancreatic Cancer* 2011 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins www.pancreasjournal.com

671

statin users of such a commonly used drug, particularly as durations of use are increasing.13

REFERENCES

1. Wong WW, Dimitroulakos J, Minden MD, et al. HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors and the malignant cell: the statin family of drugs as triggers of tumor-specific apoptosis. Leukemia. 2002;16:508Y519. 2. Hebert PR, Gaziano JM, Chan KS, et al. Cholesterol lowering with statin

drugs, risk of stroke, and total mortality. An overview of randomized trials. JAMA. 1997;278:313Y321.

3. Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomized trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267Y1278.

4. Newman TB, Hulley SB. Carcinogenicity of lipid-lowering drugs. JAMA. 1996;275:55Y60.

5. Keyomarsi K, Sandoval L, Band V, et al. Synchronization of tumor and normal cells from G1 to multiple cell cycles by lovastatin. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3602Y3609.

6. Dimitroulakos J, Marhin WH, Tokunaga J, et al. Microarray and biochemical analysis of lovastatin-induced apoptosis of squamous cell carcinoma. Neoplasia. 2002;4:337Y346.

7. Weis M, Heeschen C, Glassford AJ, et al. Statins have biphasic effects on angiogenesis. Circulation. 2002;105:739Y745. 8. Park HJ, Hong D, Iruela-Arispe L, et al.

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors interfere with angiogenesis by inhibiting the geranylgeranylation of RhoA. Circ Res. 2002;91:143Y150.

9. Alonso DF, Farina HG, Skilton G, et al. Reduction of mouse mammary tumor formation and metastasis by lovastatin, an inhibitor of the mevalonate pathway of cholesterol synthesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;50:83Y93.

10. Kusama T, Mukai M, Iwasaki T, et al.

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors reduce human pancreatic cancer cell invasion and metastasis. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:308Y317.

11. Kaye JA, Jick H. Statin use and cancer risk in the General Practice Research Database. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:635Y637.

12. Dale KM, Coleman CI, Henyan NN, et al. Statins and cancer risk: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2006;295:74Y80.

13. Coogan PF, Rosenberg L, Strom BL. Statin use and the risk of 10 cancers. Epidemiology. 2007;18:213Y219.

14. Browning DR, Martin RM. Statins and risk of cancer: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Int J cancer. 2006;120:833Y843. 15. Bonovas S, Filioussi K, Tsavaris N, et al. Statins and cancer risk:

a literature-based meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis of 35 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4808Y4817. 16. Setoguchi S, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, et al. Statins and the risk of lung,

breast, and colorectal cancer in the elderly. Circulation. 2007;115:27Y33.

17. Kuoppala J, Lamminpaa A, Pukkala E. Statins and cancer: a lsystematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2008;44:2122Y2132.

18. Haukka J, Sankila R, Klaukka T, et al. Incidence of cancer and statin usage-record linkage study. Int J Cancer. 2010;126:279Y284. 19. Cauley JA, Zmuda JM, Lui LY, et al. Lipid-lowering drug use and

breast cancer in older women: a prospective study. J Womens Health. 2003;12:749Y756.

20. Boudreau DM, Gardner JS, Malone KE, et al. The association between 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A inhibitor use and breast carcinoma risk among postmenopausal women. Cancer. 2004;100:2308Y2316.

21. Graaf MR, Beiderbeck AB, Egberts AC, et al. The risk of cancer in users of statins. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2388Y2394.

22. Blais L, Desgagne A, LeLorier J. 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl- coenzyme

A reductase inhibitors and the risk of cancer: a nested case-control study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2363Y2368.

23. Poynter JN, Gruber SB, Higgins PD, et al. Statins and the risk of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2184Y2192. 24. Shannon J, Tewoderos S, Garzotto M, et al. Statins and prostate

cancer risk: a case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:318Y325. 25. Khurana V, Bejjanki HR, Caldito G, et al. Statins reduce the risk of

lung cancer: a large case-control study of US veterans. Chest. 2007;131:1282Y1288.

26. Khurana V, Sheth A, Caldito G, et al. Statins reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer in humans: a case-control study of half a million veterans. Pancreas. 2007;34:260Y265.

27. El-Serag HB, Johnson ML, Hachem C, et al. Statins are associated with a reduced risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in a large cohort of patients with diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1601Y1608. 28. Friis S, Poulsen AH, Johnsen SP, et al. Cancer risk among statin

users: a population-based cohort study. Int J Cancer. 2005;114:643Y647.

29. Tobert JA. Efficacy and long-term adverse effect pattern of lovastatin. Am J Cardiol. 1988;62:28JY34J.

30. Kuo HW, Tsai SS, Tiao MM, et al. Epidemiologic features of CKD in Taiwan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;49:46Y55.

31. Chiang CW, Chen CY, Chiu HF, et al. Trends in the use of antihypertensive drugs by outpatients with diabetes in Taiwan, 1997Y2003. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2007;16:412Y421. 32. Tiao MM, Tsai SS, Kuo HW, et al. Epidemiological features of biliary

atresia in Taiwan, a national study 1996Y2003. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:62Y66.

33. Coogan PF, Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, et al. Statin use and the risk of breast and prostate cancer. Epidemiology. 2002;13:262Y267. 34. Meier CR, Scheinger RG, Kraenzlin ME, et al. HMG-CoA reductase

inhibitors and the risk of fractures. JAMA. 2000;283:3205Y3210. 35. Wang PS, Solomon DH, Mogun H, et al. HMG-CoA reductase

inhibitors and the risk of fractures. JAMA. 2000;283:3211Y3216. 36. Rejnmark L, Plsen ML, Johnsen SP, et al. Hip fracture risk in statin

usersVa population-based Danish case-control study. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:452Y458.

37. Jadhav SB, Jain GK. Statins and osteoporosis: new role for old drugs. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2006;58:3Y18.

38. WHO Collaborating Center for Drugs Statistics Methodology. ATC Index With DDDs 2003. Oslo: WHO; 2003.

39. Hart AR, Kennedy H, Harvey I. Pancreatic cancer: a review of the evidence on causation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:275Y282. 40. Danesh FR, Sadeghi MM, Amro N, et al.

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors prevent high glucose-induced proliferation of mesangial cells via modulation of Rho GTPase/p21 signaling pathway: implications for diabetic nephropathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2002;99:8301Y8305. 41. Takemoto M, Liao JK. Pleiotropic effects of

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21:1712Y1719. 42. Blanco-Colio LM, Villa A, Ortego M, et al.

3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase inhibitors, atorvastatin and simvastatin, induce apoptosis of vascular smooth muscle cells by downregulation of Bcl-2 expression and Rho A prenylation. Atherosclerosis. 2002;161:17Y26.

43. Kusama T, Mukai M, Iwasaki T, et al. Inhibition of epidermal growth factor induced RhoA translocation and invasion of human pancreatic cancer cells by 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl- coenzyme A reductase inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4885Y4891.

44. Shibata MA, Avanaugh C, Shibata E, et al. Comparative effects of lovastatin on mammary and prostate oncogenesis in transgenic mouse models. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:453Y459.

45. Rao S, Porter DC, Chen X, et al. Lovastatin-mediated G1 arrest is through inhibition of the proteasome, independent of hydroxymethyl glutaryl-CoA reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1999;96:7797Y7802.

Chiu et al Pancreas