【Original article】

Prevalence of and risk factors for musculoskeletal

complaints among Taiwanese dentists

Running title: Musculoskeletal disorders among dentists

Tzu-Hsien Lin

1,2, Yen Chun Liu

3, Tien-Yu Hsieh

3, Feng-Ying Hsiao

1,

Yi-Chen Lai

1, Chin-Shun Chang

4*1 Department of Dental Hygiene, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan

2 Department of Occupational Safety and Health, China Medical University, Taichung, Taiwan 3 Department of Oral Hygiene, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

4 Global Center of Excellence for Oral Health Research and Development, Kaohsiung Medical

University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

*Corresponding author. Global Center of Excellence for Oral Health Research and Development, Kaohsiung Medical University, 100 Shih-Chuan 1st Road, San Ming District, Kaohsiung 80708, Taiwan.

E-mail: csc1201@seed.net.tw

Tel: 886-925-095895 Fax: 886-2-24245576

Abstract

Background/purpose: The prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) was investigated among

dentists in Taiwan, and risk factors for MSDs were evaluated for symptoms in different parts of the body.

Materials and methods: The Nordic Musculoskeletal Questionnaire (NMQ) modified by the Taiwan

Institute of Occupational Safety and Health was completed by 197 dentists (146 males and 51 females) from members of three groups: the Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (n = 33), the Association of Family Dentistry (n = 55), and the Taichung County Dental Association (n = 109). The reported symptoms were compared by means of a Chi-squared test according to various risk factors.

Results: More than half of respondents had experienced symptoms in the shoulders (75%), neck

(72%), and lower back (66%) in the year before the survey. Three parts of the body with lower prevalences (13%~15%) of trouble were the hips/thighs/buttocks, knees, and ankles/feet. Seven percent of respondents indicated no trouble in any part of their bodies. The prevalence of trouble in the neck increased when the number of days worked per week increased. Risk factors (p < 0.05) included working in a medical center for the shoulders; working with no more than one dental assistant, having a body height of > 178 cm, and having a mean working time of > 10 min/patient for the elbows; being < 36 years old, having < 11 years of experience, and having a mean time for forward bending or using a handpiece/scaler per patient for the wrists/hands; working 7 days per week for the lower back and knees; having a patient load of > 20 patients/day and being > 35 years old for the hips/thighs/buttocks; and a having mean working time of > 48 h/week for the lower back.

Conclusions: The participating Taiwanese dentists seemed to suffer a high prevalence of MSDs,

especially of the shoulders, neck, and lower back. There were various associated factors and correlations with MSDs in each part of the body.

Introduction

The issue of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) is an important occupational health problem in all sectors, including healthcare industries and modern dentistry.1 MSDs can affect the body's muscles,

joints, tendons, ligaments, and nerves from the neck to the feet. Health problems range from discomfort, minor aches and pains, to more-serious medical conditions resulting in significant social and economic consequences, such as reduced quality of dental treatment, absence from work, and even leaving the profession.2,3

Several reports reviewed the prevalence of MSDs among dentists and dental hygienists.1-3

Prevalences of MSDs among dental-care teams range 46%~93% around the world.2 The most-often

affected part of the body of dental professionals might be the shoulder (21%~81%), and the prevalence of neck pain was in the range of 19.8%~68%. The lowest value (19.8%) was reported among Saudi Arabian dentists in a 2003 report,4 but that had increased to 67.9% in a 2008 report.5 However, there is

still no clear information about the prevalence of MSDs among Taiwanese dentists.

In addition to studies concerned with MSDs among dental professionals, some surveys focused on problems among dental and dental-hygiene students.6,7 Compared to professionals, students had a

lower prevalence of MSDs, indicating the prevalence of MSDs would increase when students graduated and began to develop their professional dental careers.

Since dentists continue to suffer a high prevalence of MSDs and related studies are still quite limited, we need to fully understand the nature of MSDs among Taiwanese dentists, and identify causative factors and correlations with MSDs.1,2 In this study, the prevalence of MSDs was investigated

among dentists in Taiwan, and risk factors for MSDs were evaluated for symptoms in different parts of the body.

Materials and methods

The standardized Nordic musculoskeletal questionnaire (NMQ)8,9 was administered to dentists. The

NMQ was translated into a Chinese version,10 and its reliability was found to be acceptable.11,12 An

anatomical diagram with nine specifically shaded areas was included in the NMQ, including the neck, shoulders, upper back, lower back, elbows, wrists/hands, hips/thighs/buttocks, knees, and ankles/feet. A 1-year recall of MSDs was used in this study, as this was shown to be an appropriate time-scale in Taiwan,10 Japan,13 Korea,14 Saudi Arabia,5 Australia,15 and Denmark.16 In addition, the questionnaire

contained general items, such as gender, age, seniority, and working conditions, including the work place, frequencies and duration of work tasks, number of dental assistants, and durations of being in a bent position and using handpieces.

The NMQ was distributed to members of three dental professional groups, including the Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AOMS), the Association of Family Dentistry (AFD), and the Taichung County Dental Association (TCDA) when they attended the annual conference of the respective associations in 2009.

Data analysis

A database was designed using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA), and data were analyzed using SPSS vers. 13.0 software (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive data are reported as frequencies and percentages. Reported symptoms were compared by means of a Chi-squared test according to the various risk factors.5 The 95% confidence interval (CI) of the prevalence rate of musculoskeletal

95% CI = 1.96 x n q * p ; (1)

where p is the prevalence rate, q is 1 - p, n is the sample size, i.e., 197, and 1.96 is the z-value for a confidence interval of 95%.

Results

Clinical practice characteristics

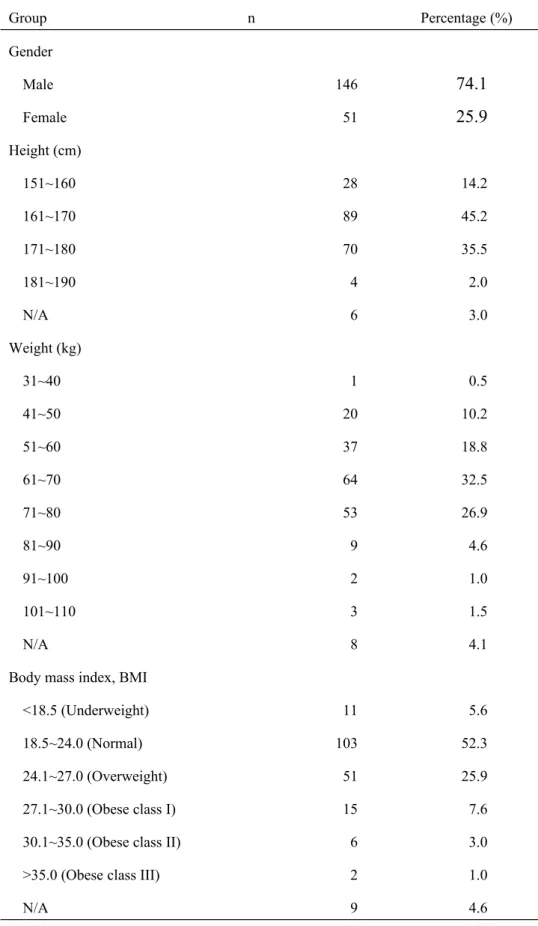

During the conferences, effective responses from 197 dentists were received. Tables 1 to 4 summarize dentists’ background information and professional characteristics. Among the respondents, 146 (74.1%) were male and 51 (25.9%) were female (Table 1). Nearly half of the dentists (45.2%) were 161~170 cm tall, and more than one-third (35.5%) were 171~180 cm tall. Four dentists were taller than 180 cm. Values of the body mass index (BMI) of over half (52.3%) of the dentists were in a normal range (18.5~24.0), and 11.6% were obese.

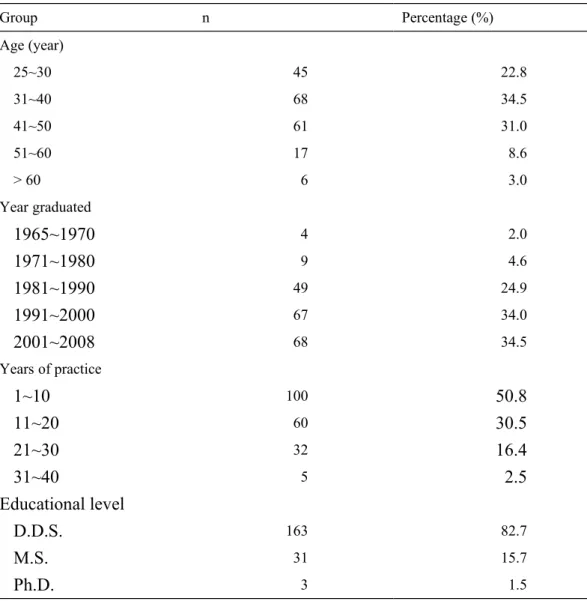

Over one-third (34.5%) were 31~40 years old, and had graduated between 2001 and 2008 (34.5%) and 1991~2000 (34.0%) (Table 2). More than 50% had worked for less than 10 years, an additional 30.5% had worked for 10~20 years, and 19.3% had worked for more than 20 years. Nearly one-fifth (17.2%) of participants had a master's or PhD degree.

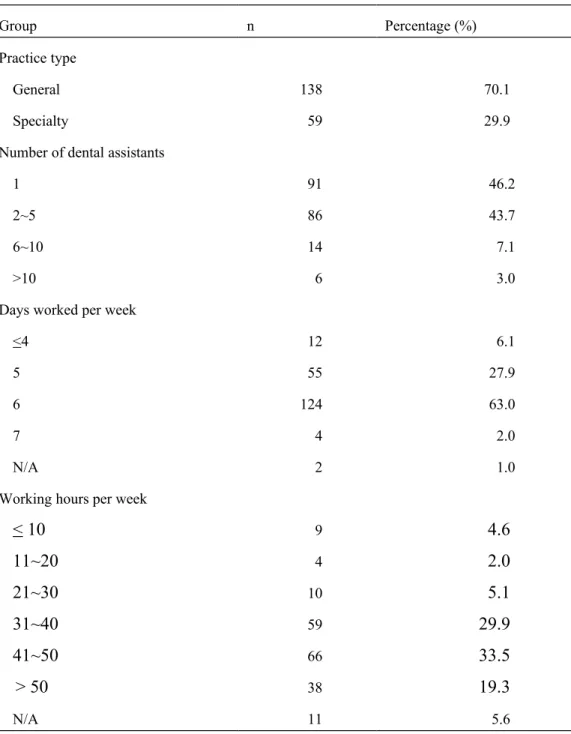

Among the 197 dentists, 59 (29.9%) said that they worked in a specialty, almost all of whom were in oral surgery (Table 3). About one-half (46.2%) worked with one dental assistant, and also nearly another one-half (43.7%) had two dental assistants. Nearly two-thirds (63.0%) worked 6 days/week, i.e., only being off on Sundays. Four dentists (2%) worked every day. Over one-third (33.5%) worked 41~50 h/week, 29.9% worked 31~40 h/week, and 19.3% over 50 h/week. The other three shorter working-hour groups, including ≤ 10, 11~20, and 21~30 h/week, together comprised 11.7%.

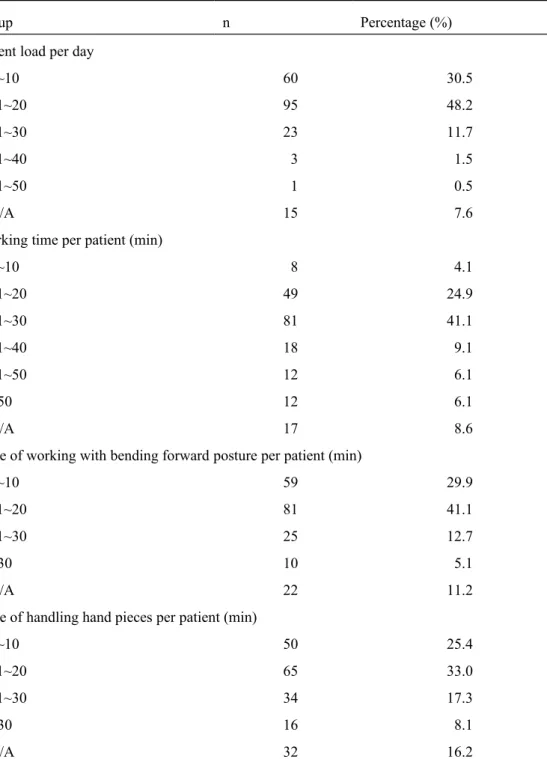

Nearly half (48.2%) of the dentists treated 11~20 patients/day, and another 30.5% treated no more than ten patients/day (Table 4). Over 40% (41.4%) of dentists treated each patient in 20~30 min, and about one-quarter (24.9%) used 11~20 min per patient. During treatment, more than 40% (41.1%) of dentists bent their body forward for an average time of 11~20 min/patient. About 30% (29.9%) of dentists bent forward for < 10 min. About one-third (33.0%) of dentists used handpieces for 11~20 min/patient. About a half (25.4%) used handpieces for < 10 min/patient.

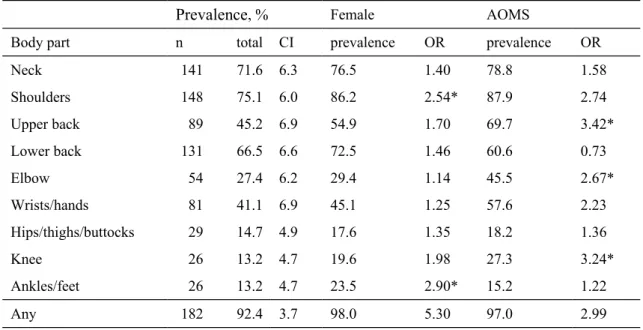

Prevalences of MSDs among Taiwanese dentists

Self-reported prevalences (%) of musculoskeletal complaints for nine parts of body in the past year among Taiwanese dentists are shown in Table 5. More than one-half of respondents had experienced symptoms in the shoulders (75.1%), neck (71.6%), and lower back (66.5%) in the past year. Three parts of body with lower prevalences (13%~15%) of trouble were the hips/thighs/buttocks, knees, and ankles/feet. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were in the range from 3.7%~6.9%.

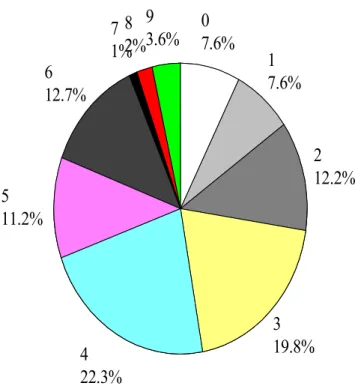

The distribution of the number (0~9) of body regions with musculoskeletal complaints for dentists (n = 197) is shown in Fig. 1. Fewer than ten percent (7.6%) of respondents indicated that they had had no trouble in any part of their body during the past year. Around 3.6% indicated musculoskeletal trouble in all nine parts of their body. Most participants reported musculoskeletal troubles at three (19.8%) or four (22.3%) parts of their bodies.

Risk factors for MSDs among Taiwanese dentists

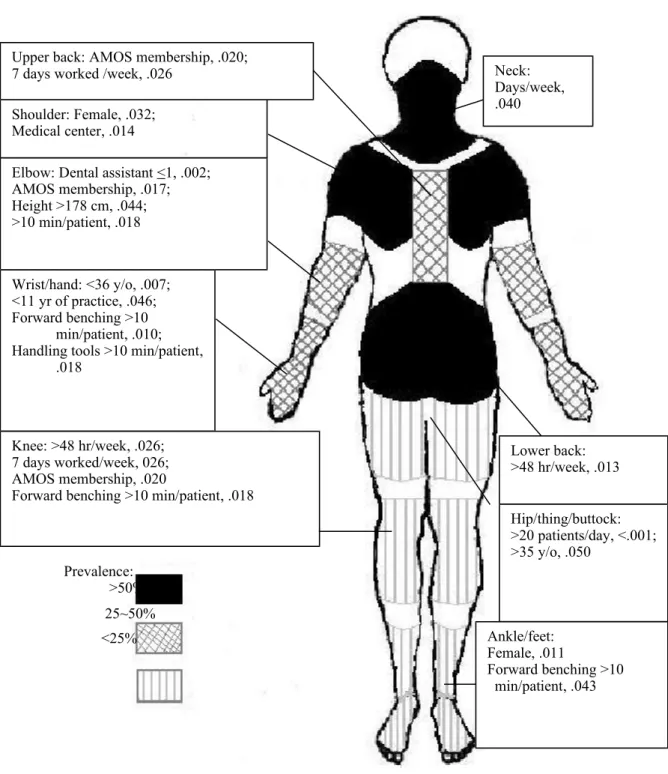

Risk factors (p < 0.05) included being female for disorders of the shoulders and ankles/feet; having a body height of > 178 cm, working with no more than one dental assistant, and having a mean working

time >10 min/patient for the elbows; having < 11 years of clinical experience and being aged < 36 years for the wrists/hands; having a patient load of > 20 patients/day and being aged > 35 years for the hips/thighs/buttocks; working in a medical center for the shoulders; having AOMS membership for the upper back, elbows, and knees; working 7 days/week for the upper back and knees; having a mean working time of > 48 h/week for the lower back and knees; bending forward for > 10 min/patient for the wrists/hands, knees, and ankles/feet; and having a mean time of using a handpiece/scaler of > 10 min/patient for the wrist/hand.

Figure 2 shows the nine parts of the body with various symbols to indicate different ranges of prevalences of musculoskeletal complaints. Risk factors for each part are also indicated in the figure. There were no statistically significant differences for areas of practice (city/country), marital status, or educational level.

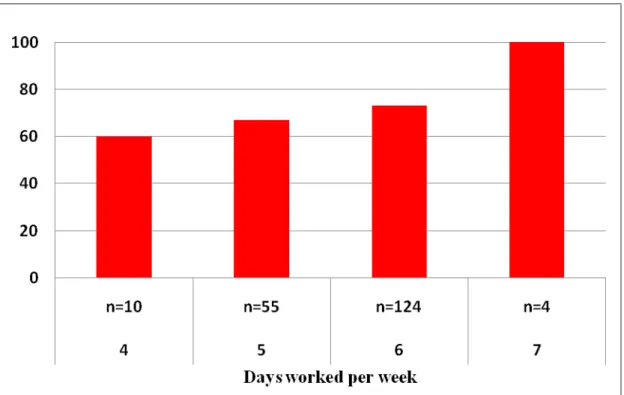

The prevalence for troubles in the neck increased when the number of days/week worked increased from 4 to 7 days (p = 0.040, Fig. 3). The parameter, days/week worked, might be a risk factor for trouble in the neck.

Discussion

Prevalences of MSDs among Taiwanese dentists

The Nordic standardized questionnaire has been used for analyzing musculoskeletal symptoms since 1987,8 and is an internationally respected instrument for evaluating musculoskeletal complaints.11 It is a

self-reported survey method, and disorders include aches, pains, and discomfort in the musculoskeletal system,16 which might not be diagnosed as a disease by physicians.

In this study, members of the AOMS were chosen to be the group of specialty dentists, the AFD was regarded as one of the largest specialty associations, and the TCDA was considered a local association. The questionnaire survey was conducted during their respective annual meetings, and dentists who joined the meetings were considered to be active and representative member of their associations.

Ratios of gender and specialty in our study were similar to those of a recent survey in Taiwan (p = 1.000 and 0.202, respectively).17 The ratio of female participants in this study (25.9%) might also be

similar to characteristics of the population of dentists in Taiwan. According to equation (1), the 95% CI of the prevalence depends on the sample size and prevalence, not the total number of the target population. CIs shown in Table 5 ranged 3.7%~6.9%. If we had doubled the sample size to 400, the range of CIs would have been 2.6%~4.9%.

There were 7.6% of respondents who reported no trouble in any part of their bodies during the past year. This means at least one body part of 92.4% of dentists experienced pain. There were 92.3%, 83%, 78%, 78%, and 64% of dentists who reported similar complaints in studies from Iraq,18 Saudi

Arabia,5 Sweden,2 Thailand,19 and Australia.19 The prevalence among Taiwanese dentists seemed to be

higher than figures from those studies. In one study that conducted an MSD survey among US dental hygienists,2 the total prevalence was 93%, which was almost the same as that found in our study. Since

there are still no dental hygienists in Taiwan, all of the tasks of dental hygienists, such as scaling and [wrong word?]vanishing, are performed by dentists in Taiwan. Consequently, prevalences of MSDs were similar between Taiwanese dentists and US dental hygienists.

The participating Taiwanese dentists seemed to suffer a high prevalence of MSDs, especially of the neck, shoulders, and lower back, with prevalence in the range of 66%~75%. These three body parts being susceptible to MSDs was indicated in several review articles.1-3 Our results were slightly higher

than outcomes obtained from a questionnaire survey of Danish dentists, which respectively reported 65% and 59% of 1-year prevalences of neck/shoulder and low-back pain.16

The part of body with the highest prevalence (75.1%) in our research was the shoulders. Among shoulder-related surveys, prevalence rates of disorder were 53%, 52%, 46%, and 21% for dentists in Australia, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia,5 and the US, and 81% and 60% for dental hygienists in

Sweden and the US.2 Based on those reports, our survey might have the highest prevalence of neck

trouble among dental personnel around the world, and it was only slightly lower than that among Swedish dental hygienists.

The part of body with the second highest prevalence in our research was the neck (71.6%). According to neck-related surveys, prevalence rates of disorders were 68%, 57%, 56%, 51%, and 28% of dentists in Saudi Arabia,5 Australia, Poland, the Netherlands, and the US.2 When dental hygienists

were the subjects of the survey, respective prevalence rates were 68%, 62%, and 28% for the US, Sweden, and Saudi Arabia.2,4 Taiwanese dentists seemed to have the highest prevalence of neck

troubles.

The part of body with the third highest prevalence in our research was the lower back (66.5%). According to back-related surveys, respective prevalence rates of disorders were 60%, 60%, 54%, 52%, and 45% for dentists in Denmark, Poland, Australia, Saudi Arabia,5 and the Netherlands.2

Respective prevalence rates of dental hygienists from the US, Sweden, and Saudi Arabia were 57%, 39%, and 21%.2 Under similar conditions, Taiwanese dentists also seemed to report the highest

prevalence of lower-back pain. The prevalence was also higher than that among Taiwanese urban taxi drivers (51%).10

The prevalence of wrist/hand pain was 41.1% in our survey, which was in the range of rates reported from Sweden (54%), Poland (44%), Australia (34%), and Saudi Arabia (19%).2,5 Respective

prevalences among dental hygienists was reported to be 69% and 64% in the US and Sweden.2 In

general, the prevalence of wrist/hand pain among dental hygienists is higher than that among dentists. Tasks of these two dental professions differ. Scaling is the major task of dental hygienists, and it usually requires more than 30 min to perform scaling on each patient. The task might cause pain in the wrist/hands region, especially when working without a break. However, Taiwanese dentists usually finish scaling and other treatments in 30 min (Table 4), and might not have such a high prevalence of wrist/hand problems as do dental hygienists in other countries.

There were various causative factors and correlations with MSDs for each part of the body. In general, the most important agents are likely poor posture and work habits.1 For example, bending

forward for more than 10 min while treating one patient was found to be a risk factor for MSD complaints in the wrists/hands among Taiwanese dentists (Fig. 2). Maintaining this kind of poor posture for an extended period might cause discomfort to the entire body, including the knees and ankles/feet (Fig. 2).

In our study, the odds ratios of female dentists reporting MSDs were > 1 for all nine parts of the body, and ranged 1.14~2.90 (Table 5). Prevalence rates among female dentists were statistically significantly higher than those of male dentists for the shoulders and ankles/feet (Fig. 2). This corresponds with reports from earlier studies in Thailand19 and New South Wales.20 In a Saudi Arabian

study,5 respective prevalence rates of pain in the shoulders and feet/ankles were 27.3% and 1.3% for

female dentists, and only 3.2% and 0% for male dentists. Musculoskeletal pain is also a major health complaint in the healthcare sector. A study suggested assessing musculoskeletal complaints among female hospital staff with separate items for neck/shoulders, the lower back, and extremities, including the ankles/feet.21

For wrist/hand disorders, Taiwanese dentists without pain had worked for 13.4 ± 8.7 years, compared to 11.1 ± 8.0 years for those with pain (p = 0.059). Results showed that dentists without MSDs were somewhat older or more experienced than those with disorders, which is similar to results from recent studies in Saudi Arabia5 and Thailand.19 When dentists have worked for a longer time,

experienced ones are probably more capable of adjusting their working positions and techniques in order to avoid musculoskeletal problems, compared to less-experienced ones, or they have simply developed copious strategies to help deal with pain.1 Another likely explanation is simply that dentists

with severe musculoskeletal problems have quit the profession, which is called the healthy-worker effect. However, confirming these hypotheses would require further investigation.

From the analysis of time-related factors, the critical length of time for developing MSDs might be 10 min (Fig. 2). Since dental treatments are usually longer than 10 min, it is not practical for most

dentists to complete treatments in 10 min. One study suggested a 10-min break during treatment.20

However, it usually occurs after treatment is completed, and the treatment has already lasted for more than 10 min. In the future, some effective and practical modifications should be developed and evidence-based evaluations carried out to reduce the prevalence of MSDs among dentists.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported, in part, by a grant from the Association for Dental Sciences of the Republic of China. Special thanks go to J. C. Liu, C. C. Shih, and C. S. Li for conducting the questionnaire survey and coding the data.

References

1.

Leggat PA, Kedjarune U, Smith DR. Occupational health problems in modern

dentistry: a review. Ind Health 2007;45:611-21.

2.

Hayes MJ, Cockrell D, Smith DR. A systematic review of musculoskeletal

disorders among dental professionals. Int J Dent Hygiene 2009;7:159-65.

3.

Morse T, Bruneau H, Dussetschleger J. Musculoskeletal disorders of the neck

and shoulder in the dental professions. Work 2010;35:419-29.

4.

Al Wazzan KA, Almas K, El Shethri SE, Al Quahtani MQ. Back and neck

problems among dentists and dental auxiliaries. J Contemp Dent Pract

2001;2:1-10.

5.

Abduljabbar TA. Musculoskeletal disorders among dentists in Saudi Arabia.

Pakistan Oral Dent J 2008;28:135-44.

6.

Melis M, Abou-Atme YS, Cottogno L, Pittau R, Upper body musculoskeletal

symptoms in Sardinian dental students, J Can Dent Assoc 2004;70:306-10.

7.

Werner RA, Franzblau A, Gell N, Hamann C, Rodgers PA, Caruso TJ, Perry F,

Lamb C, Beaver S, Hinkamp D, Eklund K, Klausner CP. Prevalence of upper

extremity symptoms and disorders among dental and dental hygiene students.

Can Dent Assoc J 2005;33:123-31.

8.

Kuorinka I, Johnson B, Killbom A, Vinterberg H, Biering-Sorenson F, Anderson

J, Jorgenson K, Standardized Nordic questionnaire for the analysis of

musculoskeletal symptoms, App Erg 1987;18:233-7.

9.

Dickinson CE, Campion K, Foster AF, Newman SJ, O’Rourke AMT, Thomas

PG. Questionnaire development: an examination of the Nordic musculoskeletal

questionnaire. App Erg 1992;23:197-201.

10. Chen JC, Chang WR, Chang W, Christiani D. Occupational factors associated

with low back pain in urban taxi drivers. Occup Med 2005;55:535-40.

11.

de Barros ENC, Alexandre NMC. Cross-cultural adaptation of the Nordic

musculoskeletal questionnaire. Int Nursing Review 2003;50:101-8.

12. Deakin JM, Stevenson JM, Vail GR, Nelson JM, The use of the Nordic

questionnaire in an industrial setting a case study. App Erg 1994;25:182-5.

13. Smith DR , Mihashi M, Adachi Y, Koga H, Ishitake T. A detailed analysis of

musculoskeletal disorder risk factors among Japanese nurses. J Safety Re

2006;37:195-200.

14. Kee D, Seo SR. Musculoskeletal disorders among nursing personnel in Korea.

Int J Ind Erg 2007;37:207-12.

15. Lusted MJ, Carrasco CL, Mandryk JA, Healey S. Self reported symptoms in the

neck and upper limbs in nurses. App Erg 1996;27:381-7.

16. Finsen L, Christensen H, Bakke M. Musculoskeletal disorders among dentists

and variation in dental work. App Erg 1998;29:119-25.

CS. Knowledge and practices of caries prevention among Taiwanese dentists

attending a national conference. J Dental Sci 2010;5:229-36.

18. Al-Sayagh GD. The occupational hazards and diseases among dentists in Mosul

City: musculoskeletal pain, eye problem and hepatitis, Al-Rafidain Dent J

2006;6:136- 43.

19. Chowanadisai S, Kukiattrakoon B, Yapong B, Kedjarune U, Leggat PA.

Occupational health problems of dentists in southern Thailand. Int Dent J

2000;50:36-40.

20. Marshall ED, Duncombe LM, Robinson RQ, Kilbreath SL, Musculoskeletal

symptoms in New South Wales dentists. Austr Dent J 1997;42:240-6.

21.

Bru E, Mykletun RJ, Svebak S. Assessment of musculoskeletal and other health complaints inTable 1. Background information of participating dentists (total N=197) Group n Percentage (%) Gender Male 146

74.1

Female 5125.9

Height (cm) 151~160 28 14.2 161~170 89 45.2 171~180 70 35.5 181~190 4 2.0 N/A 6 3.0 Weight (kg) 31~40 1 0.5 41~50 20 10.2 51~60 37 18.8 61~70 64 32.5 71~80 53 26.9 81~90 9 4.6 91~100 2 1.0 101~110 3 1.5 N/A 8 4.1Body mass index, BMI

<18.5 (Underweight) 11 5.6

18.5~24.0 (Normal) 103 52.3

24.1~27.0 (Overweight) 51 25.9

27.1~30.0 (Obese class I) 15 7.6

30.1~35.0 (Obese class II) 6 3.0

>35.0 (Obese class III) 2 1.0

Table 2. Age and seniority information of participating dentists (total N=197) Group n Percentage (%) Age (year) 25~30 45 22.8 31~40 68 34.5 41~50 61 31.0 51~60 17 8.6 > 60 6 3.0 Year graduated

1965~1970

4 2.01971~1980

9 4.61981~1990

49 24.91991~2000

67 34.02001~2008

68 34.5 Years of practice1~10

10050.8

11~20

6030.5

21~30

3216.4

31~40

52.5

Educational level

D.D.S.

163 82.7M.S.

31 15.7Ph.D.

3 1.5Table 3. Professional characteristics of participating dentists (total N=197)

Group n Percentage (%)

Practice type

General 138 70.1

Specialty 59 29.9

Number of dental assistants

1 91 46.2

2~5 86 43.7

6~10 14 7.1

>10 6 3.0

Days worked per week

<4 12 6.1

5 55 27.9

6 124 63.0

7 4 2.0

N/A 2 1.0

Working hours per week

< 10

94.6

11~20

42.0

21~30

105.1

31~40

5929.9

41~50

6633.5

> 50

3819.3

N/A 11 5.6Table 4. Working characteristics of participating dentists (total N=197)

Group n Percentage (%)

Patient load per day

1~10 60 30.5 11~20 95 48.2 21~30 23 11.7 31~40 3 1.5 41~50 1 0.5 N/A 15 7.6

Working time per patient (min)

1~10 8 4.1 11~20 49 24.9 21~30 81 41.1 31~40 18 9.1 41~50 12 6.1 >50 12 6.1 N/A 17 8.6

Time of working with bending forward posture per patient (min)

1~10 59 29.9

11~20 81 41.1

21~30 25 12.7

>30 10 5.1

N/A 22 11.2

Time of handling hand pieces per patient (min)

1~10 50 25.4

11~20 65 33.0

21~30 34 17.3

>30 16 8.1

Table 5. Self-reported prevalence and confidence interval (CI) of musculoskeletal disorders among

Taiwan dentists (total N=197), and odds ratio (OR) for female dentists and members of Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons (AOMS)

Prevalence, % Female AOMS

Body part n total CI prevalence OR prevalence OR

Neck 141 71.6 6.3 76.5 1.40 78.8 1.58 Shoulders 148 75.1 6.0 86.2 2.54* 87.9 2.74 Upper back 89 45.2 6.9 54.9 1.70 69.7 3.42* Lower back 131 66.5 6.6 72.5 1.46 60.6 0.73 Elbow 54 27.4 6.2 29.4 1.14 45.5 2.67* Wrists/hands 81 41.1 6.9 45.1 1.25 57.6 2.23 Hips/thighs/buttocks 29 14.7 4.9 17.6 1.35 18.2 1.36 Knee 26 13.2 4.7 19.6 1.98 27.3 3.24* Ankles/feet 26 13.2 4.7 23.5 2.90* 15.2 1.22 Any 182 92.4 3.7 98.0 5.30 97.0 2.99 *p-value <0.05

9

3.6%

8

2%

7

1%

6

12.7%

5

11.2%

4

22.3%

3

19.8%

2

12.2%

1

7.6%

0

7.6%

Figure 1. Distribution of number (0-9) of body regions with musculoskeletal complaints for each

dentist (n=197). “0” indicates without any musculoskeletal trouble, and “9” indicates with musculoskeletal trouble at all the nine parts of body.

Figure 2. Prevalence and risk factors at nine parts of body among Taiwan dentists. The number shown

after the risk factor is p-value. Shoulder: Female, .032;

Medical center, .014

Upper back: AMOS membership, .020; 7 days worked /week, .026

Hip/thing/buttock: >20 patients/day, <.001; >35 y/o, .050 Ankle/feet: Female, .011 Forward benching >10 min/patient, .043 Elbow: Dental assistant <1, .002;

AMOS membership, .017; Height >178 cm, .044; >10 min/patient, .018 Wrist/hand: <36 y/o, .007; <11 yr of practice, .046; Forward benching >10 min/patient, .010; Handling tools >10 min/patient,

.018

Knee: >48 hr/week, .026; 7 days worked/week, 026; AMOS membership, .020

Forward benching >10 min/patient, .018

Prevalence: >50% 25~50% <25% Neck: Days/week, .040 Lower back: >48 hr/week, .013

Figure 3. The prevalence of pain at neck among Taiwan dentists with various days worked per week