人格特質與倫理判斷在不償付卡費意圖上所扮演的角色

全文

(2) 人格特質與倫理判斷在不償付卡費意圖上所扮演的角色. 研 究 生:劉娜婷. 指導教授:丁 承 教授. 國立交通大學經營管理研究所博士班 中文摘要 過去二十年來,企業探討倫理相關議題的研究愈來愈熱門。過去的研究探討有關企 業倫理較多在行銷領域,特別是賣方(業者)的倫理議題。然而,在企業倫理的研究模 式中,若忽略買方(消費者)的角色,可能是不完整的。瞭解消費者為何會從事不倫理 行為有助遏止此行為的發生。有關消費者倫理的研究最初是由學者發展與整理各種消費 上有倫理問題的行為,詢問消費者認為這些行為的對錯與否,繼而形成消費倫理的量 表,即一般倫理判斷。一般倫理判斷共分為四個構面,分別為主動獲利於非法活動、被 動獲利於他人、主動獲利於有問題活動以及無傷害等四種倫理判斷。過去研究在探討一 般倫理判斷的相關研究不是探討不同國家的人民其倫理判斷的情況就是探討一般倫理 判斷的前因(例如:物質傾向、對企業的態度),較少研究將一般倫理判斷連結到倫理 的行為,探討四個倫理判斷的構面對某種倫理行為的影響。瞭解倫理判斷的四個構面如 何影響消費倫理行為是相當值得探討的議題。 本論文提出一個模式,同時探討人格特質(內外控與風險承擔傾向)、信用卡使用 之倫理判斷與不償付卡費行為意圖之關係。本研究探討具外控與風險承擔傾向人格特質 的人,可經由個人的倫理判斷而影響不償付卡費的意圖。另外,具外控特質的人也可能 較容易產生不償付卡費的意圖。藉由瞭解消費者為何不償付卡費的可能原因,有助發卡 機構減少信用卡的呆帳。有趣的是,關係行銷策略應有助於抑制被動不償付卡費之行為 i.

(3) 意圖的產生。 關鍵詞: 人格特質、內外控、風險承擔傾向、倫理判斷、不償付卡費意圖. ii.

(4) The Roles of Personality and Ethical Judgments in Intention to Not Repay Credit Card Expenses. Student:Na-Ting Liu. Advisor:Dr. Cherng G. Ding. Institute of Business and Management. National Chiao Tung University. Abstract. Concerns for ethical issues in business have dramatically increased over the last two decades. Much of the existing research on business ethics has focused on marketing and marketing related activities, especially on the seller side of the buyer/seller dyad. However, consumers are major participants in the business process and not considering them in ethics research may result in incomplete understanding of that process. An understanding of why some consumers engage in unethical behavior may be helpful in ultimately curtailing many questionable practices. The first consumer ethics studies established a ethics scale (general ethical judgments) that examined the extent to which consumers believe that certain questionable behaviors are either ethical or unethical, which consist of four dimensions: actively benefiting from an illegal activity, passively benefiting at the expense of others, actively benefiting from questionable actions, and no harm/no foul. Previous studies have examined the extent to which general ethical judgments are related to other variables (e.g., attitudinal characteristics and Materialism). However, very little attention has been given to. iii.

(5) the relationships between general ethical judgments and ethical behaviors. It is of great worth to understand how certain ethical judgments may be related to intention to not repay credit card expenses.. The dissertation proposed a model linking personality traits (locus of control and risk-taking propensity), ethical judgments regarding credit card use, and behavioral intention to not repay credit card expenses. External locus of control and risk-taking propensity can predict intention to not repay through ethical judgments. Furthermore, external locus of control can directly affect the intention. By understanding the causes of not repaying credit card expenses, financial service providers should be able to effectively reduce card bad debts. In particular, relationship marketing strategies are helpful to mitigate cardholders’intention to passively not repay.. Keywords: Personality, Locus of Control, Risk-Taking Propensity, Ethical Judgments, Intention to Not Repay Credit Card Expenses. iv.

(6) Acknowledgments I am deeply indebted to a number of people for their help in completing this dissertation. First of all, I would like to thank my dissertation advisor, Professor Cherng G. Ding, for his direction, assistance, and guidance throughout the process of the research. Words are inadequate to express my thanks to him that I have yet to see the limits of his wisdom, patience, and selfless concern for his students, and especially his pleasant characteristics as a mentor. Without his endless patience and kindness, I could not have been able to complete this thesis.. I would express special thanks to my Master’ s advisor, Professor Kuochung Chang, for providing detailed instructions and suggestions for this dissertation. I would also like to express my gratitude to Professor Chyan Yang, Professor Jin-Li Hu, Professor Chia Shen Chen, Professor Jyh-Shen Chiou, Professor Hai-Ming Chen, and Professor Fang-Tai Tseng for their valuable comments which made significant contributions to this thesis. Also, I am grateful to Ms. Hsiao in the Ph.D. program for her patience handling the process throughout my graduate studies.. Special thanks should be given to others who accompany me but not be mentioned for their friendship, diversions, and nourishment of body and soul during my years in NCTU. This work is dedicated to my parents. They always believe in me and encourage me to achieve my goals. Their compassion, generosity, and steadfast emotional support have been invaluable in helping me to focus on my academic pursuits. My sister and her families have always offered me their assistance and care. In addition, my heartfelt appreciation goes out to my best friend, eoe, for his companion and encouragement. Finally, this dissertation was partially funded by National Science Council, Taiwan (93-2416-H-009-003).. v.

(7) Table of Contents 中文摘要 .....................................................................................................................................i Abstract……………………………………………………………………….……………….iii Acknowledgments ......................................................................................................................v Table of Contents.......................................................................................................................vi List of Tables ............................................................................................................................vii List of Figures..........................................................................................................................viii Chapter 1 Introduction................................................................................................................1 1.1 Research Background ...................................................................................................1 1.2 Research Objective .......................................................................................................2 1.3 Organization of the Dissertation...................................................................................4 Chapter 2 Literature Review.......................................................................................................6 2.1 Ethical Judgments.........................................................................................................6 2.2 Ethically Questionable Behavior ..................................................................................7 2.3 Conceptual Framework.................................................................................................8 Chapter 3 Methods ...................................................................................................................18 3.1 Sample ........................................................................................................................18 3.2 Measures.....................................................................................................................18 Chapter 4 Results......................................................................................................................24 4.1 Measurement Model ...................................................................................................24 4.2 Structural Model .........................................................................................................28 Chapter 5 Discussion ................................................................................................................32 Chapter 6 Conclusions..............................................................................................................39 Appendix A...............................................................................................................................40 Appendix B...............................................................................................................................41 References ................................................................................................................................45. vi.

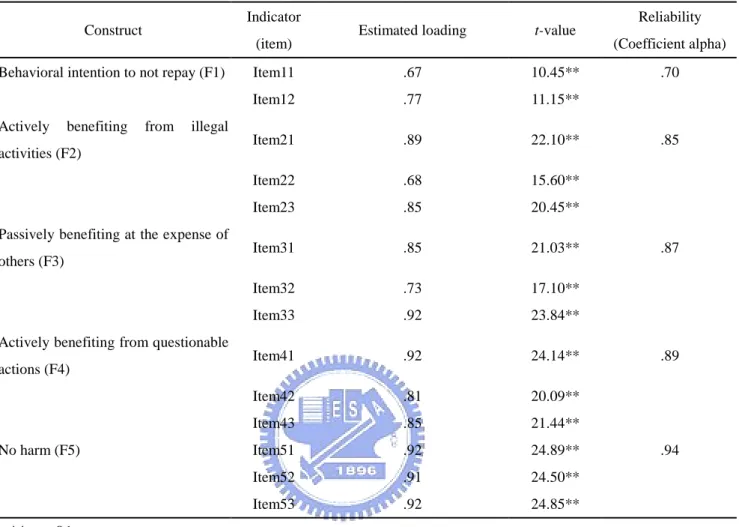

(8) List of Tables Table 3.1 Characteristics of Sample .........................................................................................20 Table 4.1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlation of the Study Variablesa .....................25 Table 4.2 Estimates of Factor Loadings in Measurement Model .............................................26 Table 4.3 Chi-Square Difference Tests .....................................................................................27. vii.

(9) List of Figures Figure 1.1 Research Flow Chart .................................................................................................5 Figure 2.1 Hypothesized Model of Personality Traits, Ethical Judgments, and Behavioral I nt e nt i on……………………………………………. . ............................................10 Figure 4.1 Standardized Parameter Estimates for the Hypothesized Model ............................29. viii.

(10) Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Research Background Concerns for ethical issues in business have dramatically increased over the last two decades. Much of the existing research on business ethics has focused on marketing and marketing related activities (Ferrell & Gresham, 1985; Hunt & Vitell, 1986; Vitell & Muncy, 1992). This is because marketing, in particular, the buyer/seller dyad, is a place where many ethical problems in business arise (Brenner & Molander, 1977; Vitell & Festervand, 1987; Vitell & Muncy, 1992). Thus, much of research concerning ethics in the marketplace has focused primarily on the seller side of the buyer/seller dyad. Relatively few studies have examined ethical issues in the marketplace from the perspective of consumer ethics. However, consumers are major participants in the business process and not considering them in ethics research may result in incomplete understanding of that process. An understanding of why some consumers engage in unethical behavior may be helpful in ultimately curtailing many questionable practices.. Among the first consumer ethics studies in the post-1990 time period were those of Muncy and Vitell (1992) and Vitell and Muncy (1992). In these articles, they established a consumer ethics scale (general ethical judgments) that examined the extent to which consumers believe that certain questionable behaviors are either ethical or unethical. The majority of general ethical judgment research conducted over the years has focused on examining consumer behavior in various countries, which is ethically questioned, in all of its variety (e.g., Rawwas, 1996). More specifically, ethical judgments are generally regarded as dependent variables and explore their antecedents (e.g., individuals’ethical ideologies) or examine the extent to which these ethical judgments related with other variables (e.g., attitudinal characteristics) (Chan et al., 1998; Vitell & Muncy, 1992). The few field studies 1.

(11) consider them as independent variables or mediator and explore their consequences. Vitell (2003) stated that future study in consumer ethics could link the Muncy-Vitell Consumer Ethics Scale to intentions and/ or behavior. Consequently, ethical judgments may play a crucial role in explaining the cause of unethical behavior.. The credit card industry has developed into a major financial service used by most consumers across all income classes. An example of the pervasiveness of credit card use is provided by the U.S. fast food industry. After the U.S. fast food industry began to accept credit payment, credit sales rapidly grew to exceed cash transactions by 50-100% (Ritzer, 1995). The use of credit cards in Taiwan has also grown rapidly during the past decade. Based on recent statistical data, the number of credit cards issued in Taiwan has reached 40 million (Directorate-General of Budget, 2003). Despite their convenience, the wide availability of such cards has created a problem of card user failure to repay the issuing company, creating heavy losses for credit card companies (e.g., banks). “ Ca r ds l a ve , ”at e r mc oi ne di nTa i wa nt or e f e rt oa person who is being tied down with his/her credit card debts, has been hogging the news for months (Kang, 2006). People who fail to manage personal finances can bring serious long-term, negative social consequences (e.g., bankruptcies, suicide). Financial service providers should seriously face a“ mor a l ha z a r d”s i t ua t i onwhe r es omede bt or sma yt r yt oa voi dpa y ba c kst hr oug hade btne g o t i a t i on mechanism or the individual bankruptcy law. By understanding the causes of not repaying credit card expenses, credit card companies should be able to effectively reduce their losses.. 1.2 Research Objective Ross and Robertson (2000) stated that decision-making about ethical issues may harm one or more of the groups or individuals affected by the outcome of the decision. It appears that failure to repay credit card expenses can be regarded as an ethically questionable 2.

(12) behavior (EQB) in consumption (Fukukawa, 2002) due to its harmful outcomes. Because not repaying card expenses involves ethically questionable behavior, consumers’decisions to engage in this action will depend on their ethical judgments. Rallapalli et al. (1994) have explored the relationship between individual personality and general ethical judgments. Additionally, Vitell (2003) suggested that future studies on consumer ethics could examine the link between general ethical judgments and intentions and/or behavior. While interest in the influence of personality on behavior is growing, little attention is paid on the relationship between individual traits and the intentions/behavior of not repaying credit card expenses. The object of this thesis is to propose a model linking personality traits (locus of control and risk-taking propensity), ethical judgments regarding credit card use, and behavioral intention to not repay credit card expenses (hereafter ‘ intention to not repay’ ). External locus of control and risk-taking propensity can predict intention to not repay through ethical judgments. Furthermore, external locus of control can directly affect the intention. Regarding the ethics of credit card use, this study strives to provide beneficial information for credit card companies.. Specifically, the current research is designed to examine the mediating processes which explain the linkages between personality and intention to not repay. That is, we attempt to see how the four dimensions of ethical judgments (actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, actively benefiting from questionable actions, and no harm/no foul) regarding credit card use mediate the relationships between two well-established personality traits associated with ethical issues (locus of control and risk-taking propensity) and intention to not repay. These relationships will be empirically examined by using the data collected from a large and diverse sample in Taiwan. The results will provide evidence regarding how personality traits influence ethical judgments, how ethical judgments make individuals more likely to have intention to not repay, and if personality directly affects intention to not repay. 3.

(13) 1.3 Organization of the Dissertation This dissertation is organized in the following manner as Figure 1.1 shows: Chapter 1 presents the motive and objective of the study. Chapter 2 reviews the relevant literatures, thus forming a conceptual framework and hypotheses. Chapter 3 gives a brief introduction of methods. Chapter 4 shows the results of the study. Chapter 5 provides the detailed discussion for the study. Chapter 6 concludes this dissertation.. 4.

(14) Chapter 1 Introduction ►Research Background ►Re s e a r c hObj e c t i v e. Chapter 2 Literature Review ►Ethical Judgments ►Ethically Questionable Behavior ►Conceptual Framework. Chapter 3 Methods ►Sample ►Measures ►Analysis. Chapter 4 Results ►Measurement Model ►Structural Model. Chapter 5 Discussion. Chapter 6 Conclusions. Figure 1.1 Research Flow Chart. 5.

(15) Chapter 2 Literature Review All aspects of consumer behavior (e.g., the acquisition, use and disposition of goods) have an integral ethical component. The Hunt-Vitell Model is a major comprehensive theoretical model that can be readily applied to individual consumer behavior (Ferrell & Gresham, 1985; Hunt & Vitell, 1986, 1993). As depicted in the Hunt-Vitell model (1993), the individual decision maker’ s perception of an ethical problem in a situation is followed by the perception of various possible alternatives that might be used to resolve the problem. When the consumer has determined a set of perceived alternatives or courses of action, two major ethical evaluations might take place: deontological evaluation and/or a teleological evaluation. The deontological evaluation focuses on the specific actions or behaviors of the consumer. In making a deontological evaluation, the individuals attempt to evaluate the inherent rightness versus wrongness of various behaviors or alternatives. On the other hand, teleology focuses on the consequences of the behaviors. The key issue in the teleological evaluation holds that the moral worth of actions or practices is determined solely by the consequences of the actions or practices. A particular behavior is considered the most ethical if the consequences bring a greater balance of good over bad than any other alternative.. 2.1 Ethical Judgments In most situations a consumer’ s ethical judgments are likely to be a function of both the deontological and teleological evaluations. Ethical judgments (the extent of which one believes that an action is moral rightness or wrongness) determine behavior through the intention, but ethical judgments might differ somewhat from intentions because one’ s teleological evaluation also affects intentions directly.. 6.

(16) General ethical judgments refer to an individual’ s subjective probability beliefs concerning various ethically-questioned consumer behaviors represented by four basic consumer ethical dimensions (e.g., Chan et al., 1998; Muncy & Eastman, 1998). To study this construct, Muncy and Vitell (1992) developed a consumer ethics scale in which questions with ethical implications can be divided into four classes. They were used for measuring ethical judgments. The first class, “ actively benefiting from illegal activities” , consists of questions regarding actions that are initiated by the consumer and that are almost universally perceived as illegal (e.g., drinking a can of soda in a supermarket without paying for it). The second class, “ passively benefiting at the expense of others” , includes questions regarding consumers taking advantages of mistakes by sellers (e.g., not saying anything when the waitress miscalculates the bill in your favor). The third class, “ actively benefiting from questionable actions or behaviors” , includes questions regarding situations in which the consumer is actively involved in some deception, but their actions may not necessarily be considered illegal (e.g., using a coupon for merchandise they did not buy). Finally, the last class, “ no harm” , includes questions regarding situations in which consumers perceive their actions as doing little or no harm/foul (e.g., using computer software or games they did not buy). Since the measures of general ethical judgments focus on the actions and consequences of those behaviors, individuals who believed in the teleological concept are more likely to agree with the questionable consumption behaviors, whereas individuals who believed in the deontological concept are more likely to use higher ethical standards in judging the questionable consumption behaviors.. 2.2 Ethically Questionable Behavior There are a number of studies concerning ethically questionable behavior (EQB) in consumption. Research on EQB comprises two streams (Fukukawa, 2002). The first stream concerns specific EQB; investigating the decision-making in relation to a specific issue of 7.

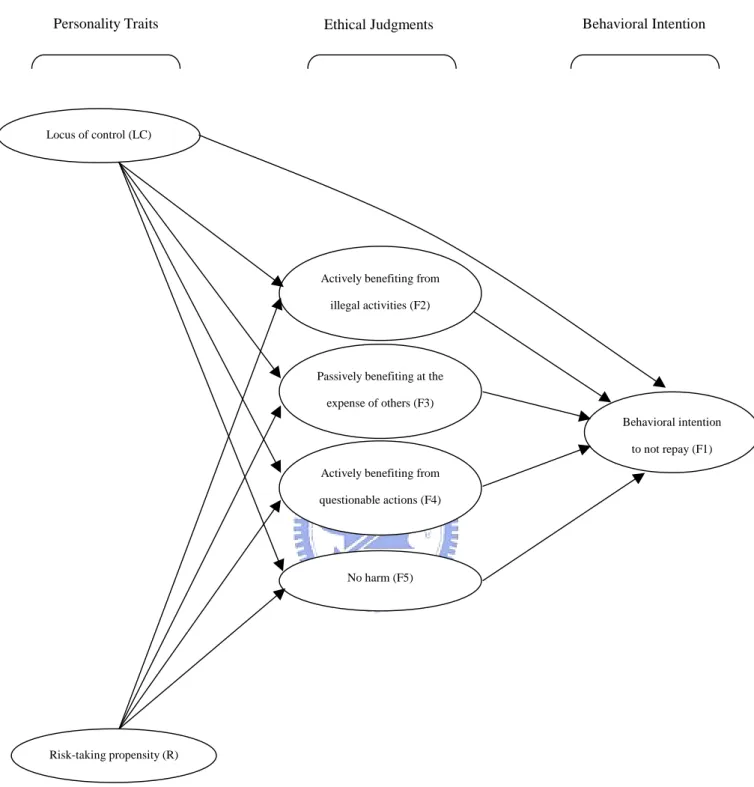

(17) EQB, seeking to understand components of attitude, a formation of intention and causes of behavior in relation to that specific issue, including tax evasion (e.g., Hessing et al., 1988), shoplifting (e.g., Babin & Griffin, 1995; Krasnovsky & Lane, 1998), software piracy (e.g., Glass & Wood, 1996; Wagner & Sanders, 2001), and counterfeiting (e.g., Albers-Miller, 1999). The second stream investigates ethical judgments regarding EQB in different settings (Muncy & Vitell, 1992). That is, Muncy and Vitell (1992) investigated four dimensions of ethical judgments (actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, actively benefiting from questionable actions, and No harm), consisting of 27 different kinds of EQB, in different settings (e.g., Austria, Rawwas, 1996; other EU countries (e.g., Greece, Italy and Spain), Polonsky et al., 2001). However, there is a paucity of research investigating the relationship between general ethical judgments and specific kinds of EQB. Specifically, examining how certain judgments may be related to specific kinds of EQB is valuable.. 2.3 Conceptual Framework Personality, Ethical Judgments, and Behavioral Intention to Not Repay. Figure 2.1 introduces a conceptual model, depicting the relationships among personality, ethical judgments, and intention to not repay. The first part of the model emphasizes the personality traits of locus of control and risk-taking propensity. These traits are selected because they are theoretically related to EQB. According to Mudrack (1993), one individual difference variable worth examining within the ethics literature is locus of control (LOC). Some studies have stated that LOC can influence the unethical behavior of individuals (e.g., Bass et al., 1999). Additionally, Rallapalli et al. (1994) studied the interrelationships between general ethical judgments and personality traits of consumers. Of the many possible. 8.

(18) personality traits (e.g., aggressiveness; achievement), only risk propensity was significantly and positively related with all dimensions of ethical judgments.. The second part of the model depicts that these personality traits will have influence on each of the four dimensions of ethical judgments. An individual’ s ethical judgment is the degree to which he or she considers various ethically-questioned consumer behaviors morally acceptable (e.g., Chan et al., 1998; Muncy & Eastman, 1998). Muncy and Vitell (1992) developed a consumer ethics scale in which questions with ethical implications can be divided into four classes. They were used for measuring ethical judgments, including actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, actively benefiting from questionable actions or behaviors, and no harm.. The third part of the proposed model describes anticipated relationships between ethical judgments and intention to not repay. Actual behavior is ultimately the topic of interest, but this study has difficulty in measuring actual behavior of this nature. That is, we may be violating individuals’rights to privacy by asking about unethical behavior. Though some factors and situations may interfere or constrain an individual’ s ability to act upon his or her intentions, intention is still an important construct found to relate significantly to actual behavior (March & Woodside, 2005). As a result, behavioral intention is used to serve as an adequate surrogate measure (Jones & Kavanagh, 1996). Additionally, the model postulates a direct influence of locus of control on intention to not repay.. 9.

(19) Personality Traits. Ethical Judgments. Behavioral Intention. Locus of control (LC). Actively benefiting from illegal activities (F2). Passively benefiting at the expense of others (F3) Behavioral intention to not repay (F1) Actively benefiting from questionable actions (F4). No harm (F5). Risk-taking propensity (R). Figure 2.1 Hypothesized Model of Personality Traits, Ethical Judgments, and Behavioral Intention. 10.

(20) Although not shown in the model, individual age and level of education are included as control variables. Age appears related to ethical judgments, with older consumers being more ethical (Muncy & Vitell, 1992; Rawwas & Singhapakdi, 1998; Vitell, 2003; Vitell et al., 1991). Studies also indicate that people with high debt levels tend to be younger and less educated (Dessart & Kuylen 1986; Sullivan et al., 1989). To reduce the likelihood that individual demographic characteristics would confound the relations examined in this study, it is necessary to control for these two characteristics.. Personality Influences on Ethical Judgments. The majority of research on ethical judgments (the second stream of research regarding EQB) has focused on examining consumer ethical judgments towards EQB in different settings (e.g., Rawwas, 1996). Previous studies generally regard ethical judgments as dependent variables and explore their antecedents (e.g., individual ethical ideologies) or examine the relationships between these ethical judgments and other variables (e.g., attitudinal characteristics; materialism) (Chan et al., 1998; Muncy & Eastman, 1998; Vitell & Muncy, 1992). Little research has examined the relationship between personality and general ethical judgments. Only Rallapalli et al. (1994) suggested that there were significant interrelationships between consumer ethical judgments and personality traits. Rallapalli et al. (1994) also argued that individual personality traits influenced consumer ethical judgments/actions.. A few studies on ethics have explored individual differences in how people deal with moral judgments. Each of these studies has attempted to delineate the ethical frameworks underlying ethical judgments (e.g., Brady, 1985; Kohlberg, 1984; Velasquez, 1992). Underlying each of these is a belief that the ethical judgments of individuals are affected by relatively stable individual differences in ethical ideologies. In light of the contingency 11.

(21) framework for understanding ethical decision making in marketing (Ferrell & Gresham, 1985), personality traits are an integral part of individual factors that can potentially affect ethical/unethical decision-making. In a related study, Munch et al. (1991) suggested that understanding consumer personalities could help understand the process used by consumers to resolve ethical dilemmas. However, the type of personality traits that influence consumer ethical judgments and how they do so is less clear.. The most widely studied personality in the ethics literature is locus of control, which has gained acceptance through several models of ethical decision-making (e.g., Stead et al., 1990; Treviño, 1986). In accordance with Rotter’ s (1966) argument, LOC is a personality variable manifested by the extent to which individuals believe events are contingent upon their own behavior or characteristics. An individual with an internal LOC perceives outcomes to be a direct result of his or her efforts, whereas an individual with an external LOC perceives outcomes to result from external forces beyond his or her control, such as fate or the actions others. Hence, individuals with an internal LOC are more inclined to take responsibility for the consequences of their behavior than are individuals with an external LOC, and also have higher ethical standards.. Some empirical studies have concluded that individuals with external locus of control probably form intentions to behave unethically because they are inclined to ascribe responsibility to others or to situational factors (Dozier & Miceli, 1985; Hegarty & Sims, 1978, 1979; Lefcourt, 1982; Singhapakdi & Vitell, 1991; Treviño & Youngblood, 1990). Thus, it appears that, generally, individuals with external locus of control may see an increased likelihood of shirking responsibility and thus may display low ethical standards. Thus, this study proposes a positive relationship between external LOC and ethical judgments regarding ethically questionable behaviors.. 12.

(22) H1a: External locus of control is positively related to the ethical judgments regarding actively benefiting from illegal activities.. H1b: External locus of control is positively related to the ethical judgments regarding passively benefiting at the expense of others.. H1c: External locus of control is positively related to the ethical judgments regarding actively benefiting from questionable actions.. H1d: External locus of control is positively related to the ethical judgments regarding no harm/ no foul.. The trait of risk-taking propensity can also be reasonably expected to be associated with ethical decision-making. Fukukawa (2002) suggested that individual attitude towards performing EQB may be influenced by one important explanatory factor: risk-taking. Risk-taking is related to the extent to which a person seeks to be exposed to uncertain situations, especially uncertainty involving financial gains or losses. This factor could be interpreted as a type of personality trait concerned with the inclination of an actor to either seek or avoid risk (Kowert & Hermann, 1997). Studies have shown that risk-taking predicts criteria related to unethical behavior. For example, in Jackson et al. (1972), the relationship between risk-taking and willingness to behave unethically in various hypothetical situational dilemmas reaches 0.44. Rallapalli et al. (1994) suggested that individuals with higher risk propensity tended to have stronger belief in benefiting from both illegal and questionable actions than individuals with lower risk propensity. Such individuals with higher risk propensity are likely to display greater need for sensation seeking, and may seek risk regardless of whether the decisions are framed as gains or losses (Tokunaga, 1993). Vitell et al. (1990) also showed that individuals with high risk taking propensity were more willing to take positions that were less socially desirable or morally questionable. Such individuals 13.

(23) appear to place greater emphasis on “ substance over form” , and may consider breaking rules if doing so would best serve the group (Cohen et al., 1995). On the basis of the above arguments, it is conceivable that under conditions such as an individual possessing higher risk-taking propensity, that individual may be more likely to benefit substantially from unethical behavior. Thus, this study proposes a positive relationship between risk-taking propensity and ethical judgments regarding ethically questionable behaviors.. H2a: Risk-taking propensity is positively related to the ethical judgments regarding actively benefiting from illegal activities.. H2b: Risk-taking propensity is positively related to the ethical judgments regarding passively benefiting at the expense of others.. H2c: Risk-taking propensity is positively related to the ethical judgments regarding actively benefiting from questionable actions.. H2d: Risk-taking propensity is positively related to the ethical judgments regarding no harm/ no foul.. Ethical Judgments and Behavioral Intention. Past studies have identified the link between attitudes or judgments concerning an action and intention to perform that action. For example, Randall (1989) surveyed empirical studies that had examined the Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) model and found that the link between judgments and intentions was substantiated. Furthermore, some studies have argued that ethical judgment for certain behavior influences this unethical behavioral intention/behavior (Barnett & Valentine, 2004; Bass et al., 1999; Kwong et al., 2003). Such studies have examined various ethical scenarios, including the purchase of pirated CDs, and whistleblowing. Hunt and Vitell (1986) described behavioral intentions as the “ likelihood that 14.

(24) any particular alternative will be chosen”and postulated that “ e t hi c a ljudgments impact behavior through the intervening variable of intentions” . Moral evaluation is a key component in the model of ethical decision-making (e.g., Akaah & Riordan, 1989; Hunt & Vitell, 1986). Individuals confronting an ethical dilemma evaluate it on the basis of relevant ethical cognitions about themselves. Interestingly, an individual’ s low ethical standards may be the key variable that breeds unethical behavior (Vitell et al., 1991). Thus, similar to the ethical judgment concerning specific action, general ethical judgments (actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, actively benefiting from questionable actions, and no harm) are also essential in the formation of behavioral intention regarding ethical or moral issues, because they are integral to individual attitudes toward ethical issues (Chiu, 2003). Therefore, this study predicts the following four relationships between ethical judgments regarding ethically questionable behaviors and intention to not repay.. H3a: The ethical judgments regarding actively benefiting from illegal activities are positively related to intention to not repay.. H3b: The ethical judgments regarding passively benefiting at the expense of others are positively related to intention to not repay.. H3c: The ethical judgments regarding actively benefiting from questionable actions are positively related to intention to not repay.. H3d: The ethical judgments regarding no harm/no foul are positively related to intention to not repay.. Personality and Behavioral Intention to Not Repay. There are two reasons for theorizing a linkage between the trait of LOC and intention to 15.

(25) not repay. First, following Hypotheses 1a~1d and Hypotheses 3a~3d, LOC should indirectly influence intention to not repay through ethical judgments. For example, individuals with external LOC are more likely to attribute responsibility to others or to situational factors, leading to their lower standard of ethics in judging the acceptability of questionable actions, thereby yielding unethical behavioral intentions. Second, external LOC may influence intention to not repay directly in terms of psychological characteristics. Individuals with a strong external LOC are more likely to get into debt, such that they easily suffer credit-related problems, because they view money from a more extrinsic, materialistic perspective than a utilitarian one, and also display anxiety about their inability to handle money (Tokunaga, 1993). In addition, Perry and Morris’ s (2005) findings indicated that, although financial knowledge and income are important, those who believe that financial outcomes are due to chance or powerful others, i.e., externals, will be slightly less likely to take steps to manage their finances. Thus, this study adds a direct link from LOC to intention to not repay.. H4: There is a direct positive relationship between external locus of control and intention to not repay.. Based on the above hypothesis development, ethical judgments (actively benefiting from illegal activity, passively benefiting at the expense of others, actively benefiting from questionable actions and no harm/foul) may play two roles in the relationships between personality (LOC and risk-taking propensity) and intention to not repay. First, ethical judgments may partially mediate the effect of LOC on intention to not repay. This relation suggests that LOC may have a direct influence on intention to not repay, but may also be related to intention to not repay through the role in shaping ethical judgments. Individuals with higher external LOC may be more likely to not repay credit card expenses partly because of their lower ethical standards and partly because they view money from an extrinsic and materialistic perspective, leading to the display of anxiety about their inability to handle 16.

(26) money regardless of ethical judgments. Second, ethical judgments may fully mediate the relationship between risk-taking propensity and intention to not repay. Risk-taking propensity may be associated with the intention only through ethical judgments made during credit card use. Individuals with higher risk-taking propensity may be more likely to seek uncertain situations and to exhibit low uncertainty avoidance, making him or her have lower ethical standard, and in turn more probably lead to intention to not repay.. 17.

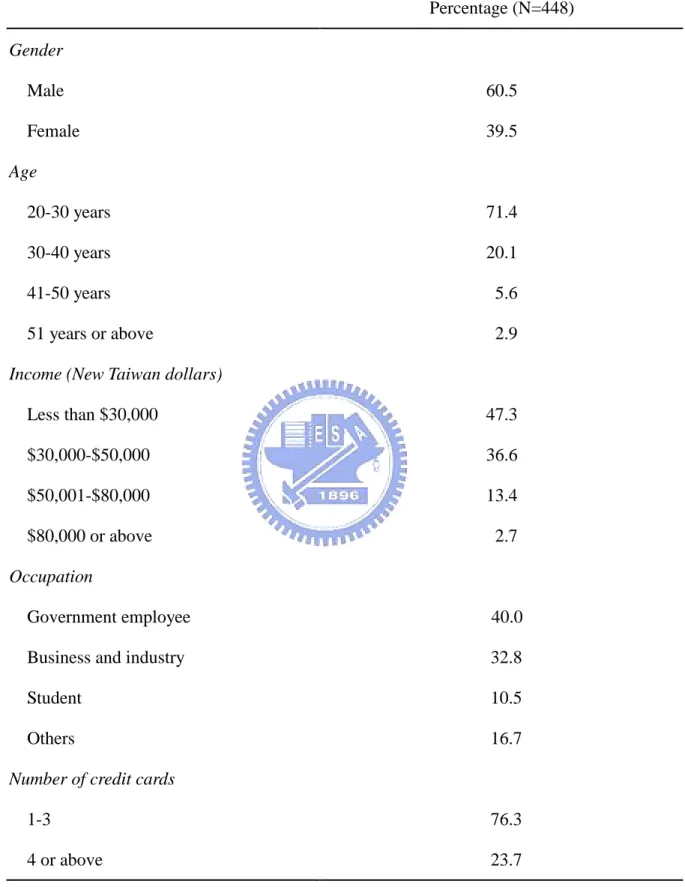

(27) Chapter 3 Methods 3.1 Sample The data were collected by questionnaires, of which 448 usable questionnaires from those holding credit cards in Taiwan (at least 20 years old) were obtained. In recent years, heavy debt levels of cardholders and over unethical marketing practices by credit card solicitors have created many social problems in Taiwan. It appears that samples from Taiwanese cardholders should be appropriate for this study. We sampled four areas in Taiwan (the areas in the North, Middle, South and East) to conduct the field survey. In each area, several representatives helped to distribute questionnaires. A convenience sample was used in this study, but sample diversification (see Table 3.1) and sample relevance have been taken into account (Sackett & Larson, 1990). In our study the sample possessed the essential person and setting characteristics (i.e., using credit cards to consume) that defined membership in the intended target population/universe.. Overall, of the 500 that were distributed, 448 completed questionnaires were received. Of the 448 credit cards consumers, 271 (60.5%) were male and 410 (91.5%) were 20~40 years old. The sample was highly educated, with 69.2% holding a college degree and 12.9% with a graduate degree. During the survey for this study, respondents were assured that all information would be kept strictly confidential in order to increase the response rate and acquire more accurate information.. 3.2 Measures Locus of Control. 18.

(28) We measured locus of control by using an abbreviated scale of LOC having 11 items developed by Barnett and Lanier (1995). Subjects were asked to respond to the items in the original forced-choice format by selecting the statement from each pair which best reflected their thoughts. Scores for each respondent ranged from 0 for an individual who selected all “ internal”statements, to a score of 11 for an individual who selected all “ external”statements. We measured a person’ s LOC by using scores summed on 11 items. The coefficient alpha for the LOC measure was 0.63 in the current study, less than the commonly used criterion of 0.7. However, since the measure items used the 0-1 scale and their items reflected widely different situations, the reliability of our measurements should be acceptable. As argued by Nunnally and Bernstein, the “ heterogeneity would be a legitimate part of the test if it were part of the domain of content implied by the construct”(Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994: 312).. Risk-Taking Propensity. Risk-taking propensity was adapted from the Jackson Personality Inventory (JPI) (Jackson, 1976). A subset of the statements from the original JPI were selected in such a way that they can better reflect culture heterogeneity. After interviewing three scholars with related expertise, the scale for risk-taking propensity was composed of 12 statements. Respondents were asked to indicate “ disagree”or “ agree”to a series of 12 statements. A score of 0 was given for “ disagree”and 1 for “ agree”for each statement. The summation of responses yielded risk-taking propensity scores from 0 to 12. Higher scores reflected individuals who were prone to higher risk-taking. The coefficient alpha for this measure was 0.71.. 19.

(29) Table 3.1 Characteristics of Sample Percentage (N=448) Gender Male. 60.5. Female. 39.5. Age 20-30 years. 71.4. 30-40 years. 20.1. 41-50 years. 5.6. 51 years or above. 2.9. Income (New Taiwan dollars) Less than $30,000. 47.3. $30,000-$50,000. 36.6. $50,001-$80,000. 13.4. $80,000 or above. 2.7. Occupation Government employee. 40.0. Business and industry. 32.8. Student. 10.5. Others. 16.7. Number of credit cards 1-3. 76.3. 4 or above. 23.7. 20.

(30) Ethical Judgments. General ethical judgments are originally used to examine various questionable consumer practices which they perceived these behavior as being wrong or not wrong, and then be extracted four different dimension, namely consumer ethical scale (CES). Many researchers employ ethical judgments only regarding specific action rather than on variety of questionable behavior (e.g., Barnett & Valentine, 2004; Bass, et al., 1999; Chiu, 2003). It may be based on a viewpoint of level of specificity (Bowen et al., 1991). If we use the four dimensions of general ethical judgments to predict some criterion, it would be best a global criteria. That is, all kinds of questionable behaviors, rather than one specific criterion such as theft. In contrast, ethical judgments for specific actions only comprise particular and narrower scope resulting in being used to predict defined behavior. Nonetheless, one purpose of our study is to investigate the influence of the four dimensions of ethical judgments on behavioral intention to not repay. In terms of this situation, the notion “ ethical judgments regarding credit cards used”are arguably an adequate surrogate measure. In other words, it still remains the construction and spirit of ethical judgments (the four dimension) and simply substitutes ethical scenarios concentrating credit card for miscellaneous ethical questionable behaviors.. The four basic consumer ethical dimensions given by Muncy and Vitell (1992) were used to represent the four subconstructs of ethical judgments, based on which four scenarios regarding the ethics of credit card use were then developed. Scenario 1 was associated with credit card use of ‘ actively benefiting from illegal activities’initiated by the consumer. Scenario 2 was associated with credit card use of ‘ passively benefiting at the expense of others’initiated by the seller; that was, consumers benefited by a seller’ s mistake. Scenario 3 was associated with credit card use of ‘ actively benefiting from questionable actions’ ,in which the consumer was actively involved, but it was probably not deemed illegal. Scenario 4 was associated with credit card use of ‘ no harm/foul’where there existed indirect rather than 21.

(31) direct immediate injury to the seller. These four scenarios were examined by interviewing five credit card business representatives and three scholars with related expertise for appropriateness and clarity. Additionally, pretests were conducted with ten business school graduate students. For each ethical scenario, we used three items in making ethical judgments (Reidenbach & Robin, 1990) (see Appendix A), and the order of the four scenarios was randomnized in order to avoid order effects. Respondents were asked to say whether they perceived each ethical scenario as unjust/just, not morally right/morally right, and unacceptable/acceptable on a 7-point scale. Moreover, we applied indirect questioning in designing each ethical scenario, which could reduce social desirability response bias (Fisher & Tellis, 1998). Respondents were asked to interpret the behavior of others, rather than directly asked to report their beliefs and feelings (Kinnear & Taylor, 1991) so that they would give a more honest answer (Fisher & Tellis, 1998). Coefficient alphas for actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, actively benefiting from questionable actions, and no harm/foul were 0.85, 0.87, 0.89, and 0.94, respectively.. Behavioral Intention to Not Repay. Individual behavioral intentions can be measured by asking individuals to read scenarios that contain ethical dilemmas and then asking them to express the likelihood in a probability sense that they would perform the behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Hunt & Vitell, 1986). Following Hunt and Vitell, respondents were asked to read one scenario regarding not repaying credit card expenses and then assessed the likelihood that they would engage in this behavior. It was measured using a five-point scale anchored with “ highly unlikely”(1) to “ highly likely”(5). The other was a statement regarding actual intention to not repay anchored by “ never”(1) to “ always”(5). The two items were combined into a single scale to measure the intention (α= 0.70).. 22.

(32) Control Variables Two control variables were included in the analysis-consumers’age and level of education. To control for differences among the four types of age and the two levels of education, we created three dummy variables for age (aged1, aged2, and aged3) and one dummy variable for education (edud1), respectively.. The measurement of Chinese version is presented in Appendix B.. Analysis. The hypothesized relationships were tested by structural equation modeling (SEM). SEM was chosen for the analyses because it allowed us to take into account measurement error, simultaneously estimated all path coefficients, and evaluated the fit of the overall model to the data. Following the two-step approach recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), the measurement model was evaluated first by using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), and then the structural model was analyzed to test the hypotheses and to perform a simultaneous test that determined whether the combined model (consisting of a measurement model and a structural model), as a whole, provided an acceptable fit to the data (Hatcher, 1994).. 23.

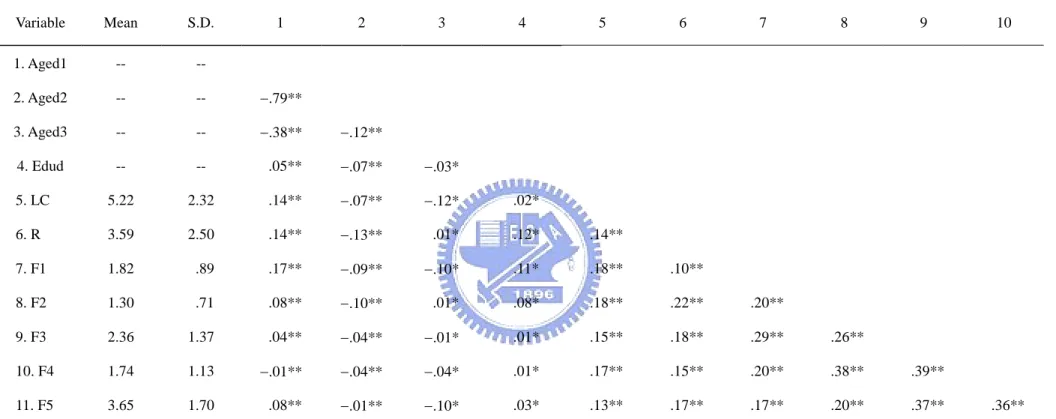

(33) Chapter 4 Results Means, standard deviations, and correlations of all variables are provided in Table 4.1 Looking at the scale means, we found that F2 (actively benefiting from illegal activities) was the lowest of all four dimensions of ethical judgments. As in prior research, respondents seemed to believe that the action was illegal and therefore unethical. Comparatively, F5 (no harm) had a mean of 3.65. Even though the act described in this factor was legal and did not cause great harm to the seller, respondents were somewhat neutral with regard to this behavior. Table 4.1 also shows that all the main variables were significantly positively correlated with each other except for the control variables.. 4.1 Measurement Model Convergent and discriminant validities of the measurements were assessed with confirmatory factor analysis. There were two indicators for intention to not repay and three indicators for each dimension of the ethical judgments. It can be seen that the loadings of the indicators on their corresponding constructs were all significant at 0.01 level (see the t-test results in Table 4.2), demonstrating convergent validity. Convergent validities for LOC and risk-taking propensity were not evaluated since the scores for LOC and risk-taking propensity were obtained by adding the values of their associated items. The fit statistics resulting from 2 CFA were a sf ol l ows :χ = 243.35 (df = 85); GFI = .94; AGFI = .90; NFI = .94; CFI = .96; and. RMSEA = .06.. 24.

(34) Table 4.1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlation of the Study Variablesa Variable. Mean. S.D.. 1. 2. 3. 4. 1. Aged1. --. --. 2. Aged2. --. --. .79**. 3. Aged3. --. --. .38**. .12**. 4. Edud. --. --. .05**. .07**. .03*. 5. LC. 5.22. 2.32. .14**. .07**. .12*. .02*. 6. R. 3.59. 2.50. .14**. .13**. .01*. .12*. .14**. 7. F1. 1.82. .89. .17**. .09**. .10*. .11*. .18**. .10**. 8. F2. 1.30. .71. .08**. .10**. .01*. .08*. .18**. .22**. .20**. 9. F3. 2.36. 1.37. .04**. .04**. .01*. .01*. .15**. .18**. .29**. .26**. 10. F4. 1.74. 1.13. .01**. .04**. .04*. .01*. .17**. .15**. .20**. .38**. .39**. 11. F5. 3.65. 1.70. .08**. .01**. .10*. .03*. .13**. .17**. .17**. .20**. .37**. a. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. N = 448. Aged1, Aged2, Aged3 = three dummy variables for age; Edud = the dummy variable for education; F1 = behavioral intention to not repay; F2 = actively benefiting from illegal activities; F3 = passively benefiting at the expense of others; F4 = actively benefiting from questionable actions; F5 = no harm; LC = locus of control; R = risk-taking propensity. * p <.05. ** p<.01.. 25. 10. .36**.

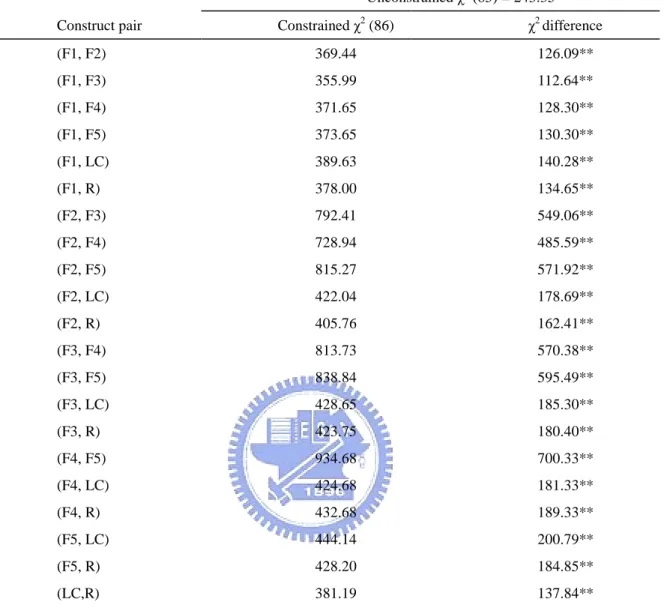

(35) Table 4.2 Estimates of Factor Loadings in Measurement Model Indicator Construct. Reliability Estimated loading. t-value. (item) Behavioral intention to not repay (F1). Actively. benefiting. from. (Coefficient alpha). Item11. .67. 10.45**. Item12. .77. 11.15**. Item21. .89. 22.10**. Item22. .68. 15.60**. Item23. .85. 20.45**. Item31. .85. 21.03**. Item32. .73. 17.10**. Item33. .92. 23.84**. Item41. .92. 24.14**. Item42. .81. 20.09**. Item43. .85. 21.44**. Item51. .92. 24.89**. Item52. .91. 24.50**. Item53. .92. 24.85**. .70. illegal .85. activities (F2). Passively benefiting at the expense of .87. others (F3). Actively benefiting from questionable .89. actions (F4). No harm (F5). .94. ** p<.01 We sequentially assessed discriminant validity for each pair of constructs by constraining the correlation coefficient between them to be 1.0 and then performing a chi-square difference test on the constrained and unconstrained models. Discriminant validity is demonstrated if the difference of the two chi-square statistics resulting from the constrained and unconstrained models is significant (Anderson & Gerbing, 1988). Since we need to assess the discriminant validity for every pair of the seven constructs, we should control the experimentwise error rate. 2 Under the experimentwise error rate of 0.01, the critical value of the chi-square test is χ (1,. 0.01/21) = 12.19 by using the Bonferroni method. As shown in Table 4.3, the chi-square difference statistics for all pairs of constructs exceed 12.19, showing that discriminant validity is successfully achieved. 26.

(36) Table 4.3 Chi-Square Difference Tests 2 Unconstrained χ (85) = 243.35 2 Constrained χ (86). 2 χ difference. (F1, F2). 369.44. 126.09**. (F1, F3). 355.99. 112.64**. (F1, F4). 371.65. 128.30**. (F1, F5). 373.65. 130.30**. (F1, LC). 389.63. 140.28**. (F1, R). 378.00. 134.65**. (F2, F3). 792.41. 549.06**. (F2, F4). 728.94. 485.59**. (F2, F5). 815.27. 571.92**. (F2, LC). 422.04. 178.69**. (F2, R). 405.76. 162.41**. (F3, F4). 813.73. 570.38**. (F3, F5). 838.84. 595.49**. (F3, LC). 428.65. 185.30**. (F3, R). 423.75. 180.40**. (F4, F5). 934.68. 700.33**. (F4, LC). 424.68. 181.33**. (F4, R). 432.68. 189.33**. (F5, LC). 444.14. 200.79**. (F5, R). 428.20. 184.85**. (LC,R). 381.19. 137.84**. Construct pair. ** Significant at the .01 overall significance level by using the Bonferroni method. Notes: F1 = behavioral intention to not repay; F2 = actively benefiting from illegal activities; F3 = passively benefiting at the expense of others; F4 = actively benefiting from questionable actions; F5 = no harm; LC = locus of control; R = risk-taking propensity.. It deserves to be mentioned that, based on the above results, we further conclude that we have obtained strong evidence for the convergent validity and discriminant validity of the ‘ ethical judgments regarding credit card use scale. This provides support for the four-factor structure.. 27.

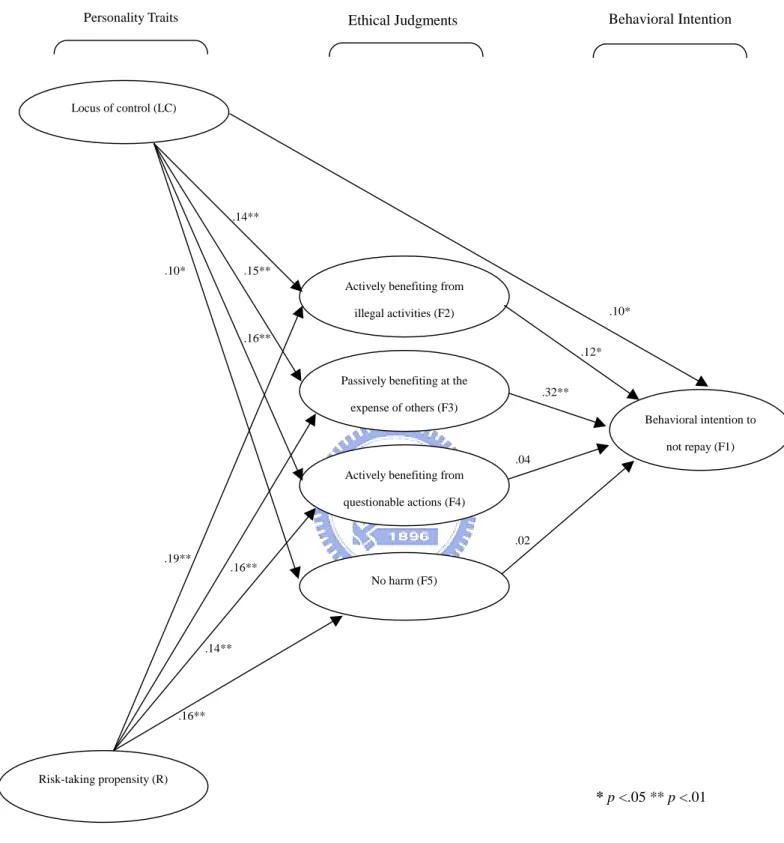

(37) 4.2 Structural Model We tested the hypotheses by using a structural model (a simultaneous test on the combined model). In addition to the interesting main variables, we also introduced control variables (age, education) that potentially influence intention to not repay and ethical judgments to refine our research results. Figure 4.1 shows the path coefficients for this 2 analysis. The hypothesized structural model displayed in Figure 4.1 is acceptable, χ = 482.45. (df = 128); GFI = .90; AGFI = .83; NFI = .91; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .07. Consistent with Hypotheses 1a~1d, the effect of external LOC on each of the four dimensions of ethical judgments was positive (actively: β= .14, p < .01; passively: β= .15, p < .01; questionable: β = .16, p < .01; no harm: β= .10, p < .05), as was the influence of risk-taking propensity (Hypotheses 2a~2d) (actively: β= .19, p < .01; passively: β= .16, p < .01; questionable: β = .14, p < .01; no harm: β= .16, p < .01). These results indicated that personality traits of individuals influenced their ethical judgments that they had in consumption. In other words, individuals with high levels of external LOC and risk-taking propensity were more likely to judge a particular questionable behavior morally acceptable than their counterparts.. 28.

(38) Personality Traits. Behavioral Intention. Ethical Judgments. Locus of control (LC). .14**. .10*. .15** Actively benefiting from .10*. illegal activities (F2) .16** .12* Passively benefiting at the .32** expense of others (F3). Behavioral intention to not repay (F1) .04 Actively benefiting from questionable actions (F4) .02 .19**. .16** No harm (F5). .14**. .16**. Risk-taking propensity (R). * p <.05 ** p <.01. Figure 4.1 Standardized Parameter Estimates for the Hypothesized Model. 29.

(39) The second set of predicted relationships described links between consumer ethical judgments and intention to not repay. Hypotheses 3a~3d predicted that ethical judgments of individuals regarding credit card use would influence their intention to not repay. Figure 4.1 reports that the ethical judgments regarding actively benefiting from illegal activities and passively benefiting at the expense of others were significantly positively related to intention to not repay (β= .12, p < .05; β= .32, p < .01), supporting Hypotheses 3a and 3b. However, neither the ethical judgments regarding actively benefiting from questionable actions nor the ethical judgments regarding no harm had significant effect on intention to not repay (β= .04, n.s.; β= .02, n.s.). Thus, Hypotheses 3c and 3d were not supported.. For the final set of predicted relationships, this study predicted that intention to not repay would be directly influenced by LOC. Figure 4.1 shows that the path coefficient for LOC was statistically significant (β= .10, p < .05), supporting Hypothesis 4. Although not specifically hypothesized, we wonder whether risk-taking propensity has a direct effect on intention to not repay. Thus, we estimated an alternative model that included a direct link between risk-taking propensity and intention to not repay. Results showed that the fit of this partially mediated model was not significantly better than the hypothesized (fully mediated) model. The 2 difference of two chi-square statistics was 0.07, much less than the critical value χ (1, 0.05) =. 3.84. This suggests that individual ethical judgments do fully account for the relationship between risk-taking propensity and intention to not repay.. In sum, these results provide some evidences that personality traits (LOC and risk-taking propensity) influence consumer ethical judgments for credit card use, and that the two dimensions of ethical judgments, actively benefiting from illegal activities and passively benefiting at the expense of others, influence their intention to not repay. Additionally, LOC still has a direct effect on the intention. Specifically, on the basis of the test for mediation (James & Brett, 1984), our findings indicated that the ethical judgments regarding actively 30.

(40) benefiting from illegal activities and passively benefiting at the expense of others partially mediated the relationship between LOC and the intention, whereas these two ethical judgments completely mediated the relationship between risk-taking propensity and the intention.. 31.

(41) Chapter 5 Discussion Extending existing research on specific kind of EQB and ethical judgments, the proposed model suggests that personality traits impact intention to not repay by affecting individual ethical judgments. Specifically, this study examines how locus of control and risk-taking propensity influence individual ethical judgments concerning credit card use, and how these ethical judgments affect the intention. Besides the indirect effect through ethical judgments, locus of control can directly affect the intention. Building on previous research, this study provides evidence that certain personality traits are related to consumer ethical judgments. Moreover, these results confirm the positive relationship often reported between ethical judgment for specific action and that behavioral intention (e.g., Barnett & Valentine, 2004; Bass et al., 1999; Chiu, 2003) in which ethical judgment regarding specific action is further extended to four dimensions of ethical judgments and their influences on specific unethical action concerning credit card use (i.e., intention to not repay credit card expenses) are investigated. Taken together, this study provides more detailed evidence of the variety of connections between personality, ethical judgments, and intention to not repay.. Personality and Ethical Judgments. This study first examined the influence of personality traits, including LOC and risk-taking propensity, on the ethical judgments of individuals regarding credit card use. Both LOC and risk-taking propensity were found to predict all dimensions of ethical judgments. As predicted, external LOC individuals were more likely to judge ethically ambiguous actions as ethical. This relationship likely occurred because such individuals easily attribute responsibility to others or to situational factors (e.g., Treviño & Youngblood, 1990), in turn leading to their low ethical standards for making judgments. Similarly, risk-taking propensity was related to each of four dimensions of ethical judgments. It seemed that when an 32.

(42) individual possessed a higher risk-taking propensity, he or she was more likely to seek and be exposed to uncertain situations and to exhibit low uncertainty avoidance, and thereby was less sensitive to ethical problems, leading to lower ethical standards. Particularly, four types of low ethical standards existed-actively benefiting from illegal activities, passively benefiting at the expense of others, actively benefiting from questionable actions, or no harm (behavior that is questionable but causes no harm).. Ethical Judgments and Behavioral Intention to Not Repay. The second portion of this study examined the relationship between the four dimensions of ethical judgments and intention to not repay. As hypothesized, the ethical judgments regarding actively benefiting from illegal actions and passively benefiting at the expense of others were both significantly positively related to intention to not repay. The findings contrasted with the non-significant relationship between the other two ethical judgments, actively benefiting from questionable actions and no harm, and intention to not repay. The relationships between ethical judgments and the intention can be further stated in the three aspects. First, this study found that individuals who possessed the ethical judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities were likely to take part in the action of not repaying credit card expenses. The result appeared to be consistent with Vitell and Muncy’ s (1992) argument, indicating that the actions for actively benefiting from illegal activities were mostly initiated by consumers, and these activities were more likely to be perceived as illegal by most consumers. Second, the ethical judgments of passively benefiting at the expense of others showed a stronger positive effect on the intention than the ethical judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities. Most of actions regarding passively benefiting at the expense of others may benefit due to the mistakes of seller (Vitell & Muncy, 1992), and therefore the resulting benefits are likely to be accepted. The thought may be explained by the technique of consumer justifications of “ denial of injury”- a state in which individuals 33.

(43) contend that their misconduct is not really serious, because no party directly suffers as a result (Sykes & Matza, 1957; Strutton et al., 1994). This result seems to suggest that if credit card companies had not sent bills or informed payment notices to the holders, holders also cannot actively repay payments, because they do not see the mistake as their fault and do not believe the credit card companies will suffer any loss as a result. Third, the other two dimensions of ethical judgments, actively benefiting from questionable actions and no harm/foul, both failed to contribute significantly to intention to not repay. The results may be traced back to the definitions of them. Actively benefiting from questionable actions indicates consumers who are actively involved in some deception, but whose actions are not as likely to be seen as illegal as those actively benefiting from illegal activities and almost seem to be considered as “ perceived legality”(Vitell & Muncy, 1992). Since individuals with the ethical judgments of actively benefiting from questionable actions could consider the action of not repaying as unethical and illegal, they are less likely to breed intention to not repay. Further, the actions of no harm/foul, which appear acceptable to many, may be so rated, because no direct harm is done to anyone (although indirect harm may occur). Individuals with the ethical judgments of no harm/foul may think that the action of not repaying can directly injure the credit card companies, and thus they are less likely to have intention to not repay.. Personality and Behavioral Intention to Not Repay. The final portion of this study examined the direct relationship between personality and intention to not repay. Regarding the trait of LOC, two possible ways were found for the linkage between LOC and the intention. First, LOC indirectly influenced the intention through the ethical judgments regarding actively benefiting from illegal activities or passively benefiting at the expense of others. Second, LOC directly influenced the intention. In other words, the influence of LOC on the intention was partially mediated by ethical judgments. On the other hand, the trait of risk-taking propensity did not have direct effect on the intention. 34.

(44) There existed only indirect effect through the ethical judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities or passively benefiting at the expense of others. The influence of risk-taking propensity on the intention was completely mediated by ethical judgments.. Managerial Implications. The results of our study have some managerial implications. First, credit card companies’ losses may be reduced if customers’personality traits can be paid more attention. For example, credit card companies can give a simple personality test (LOC and risk-taking propensity) to credit card applicants before deciding credit limit, although some countries have rules against such implementation due to discrimination. This suggestion can help credit card companies set up a more mature credit card management system. In addition, we find that individuals having the ethical judgments of actively benefiting from illegal activities or the ethical judgments of passively benefiting at the expense of others are likely not to repay credit card expenses. Thus, for those showing the tendency of actively benefiting from illegal activities, credit card companies should further carefully examine their backgrounds and history about credit card use and avoid unethical marketing practices so as to reduce heavy bad debts due to the wide availability of credit cards. Additionally, for those having tendency of passively benefiting at the expense of others, credit card companies should not only provide better management on the credit card business such as customers’bills, but also add some severe rules in order to restrain those having the tendency of passively not repaying (e.g., evading the duty of repayment deliberately and ascribing the blame to suppliers).. Steenhaut and Van Kenhove (2005) examined the relationship between relationship commitment and the reaction of shoppers to receiving too much change (passively benefiting). They found that, when the amount of excess change is larger, the less committed consumer is less likely to report receiving too much change, whereas the consumer with a high 35.

(45) relationship commitment towards the retailer is more likely to report it. Thus, in addition to adding more rules, developing a closer bond between the credit card company and the consumer is imperative. From this point of view, relationship marketing strategies can be seen as a type of “ blocking”strategy of credit card company against the action of passively not repaying (Van Kenhove et al., 2003). In other words, enhancing the affective commitment of the consumer towards the credit card company lowers an individual’ s tendency to apply the techniques of neutralization as a mean of assuaging guilt, thus lowers the tendency to engage in passively not repaying. We suggested that credit card companies should make effort to provide satisfactory tangible and intangible inputs. The consumers’perception about the inputs of the credit card company may influence their relationship commitment to the credit card company, which may in turn have impacts on their decision to act ethically or unethically (e.g., their reaction to not receiving credit card bills or payment notices or bill errors beneficial to consumers).. Limitations and Future Directions. Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, we used indirect questioning to reduce the distortion of private opinions that are revealed to the researcher by asking respondents to report on “ the nature of the external world”rather than about themselves. It is expected that respondents project their unconscious biases into ambiguous response situations and reveal their own attitudes (Campbell, 1950). In other words, the technique of indirect questioning can mitigate the effects of social desirability bias. However, rather than provide insights into the self, indirect questions may actually reveal what respondents predict a “ typical other”might do or think (Maccoby & Maccoby, 1954). The validity of indirect questioning can be examined in future research. Second, since respondents (cardholders) provide the ratings of personality traits, ethical judgments, and intention to not repay, it is possible that relations among these constructs may have been inflated by common method 36.

(46) variance. However, while it is difficult to obtain data from different sources in the present study, the technique for procedural remedies can be used to partially mitigate this concern. The potential remedy is to proximally or methodologically separate the measures by having respondents complete the measurements of the predictor and criterion variables under different conditions (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In our study, we use different item characteristics (e.g., different response formats and different scale anchors) for the measurement of the predictor and criterion variables that may reduce this problem. Future work should incorporate more procedural designs such as creating a temporal separation by introducing a time lag between the measurement of the predictor and criterion variables. Third, the data used are cross-sectional. Nonetheless, since the theoretical argument indicates that personality traits affect an individual’ s ethical judgments for something, which in turn lead to behavioral intentions, our interpretation of the results has proceeded with theoretical causal order. Future work should use longitudinal methodologies to confirm these relations. Finally, we conduct the research in Taiwan. Different results may be obtained in different countries. How the influence of ethical judgments by their determinants and the influence on unethical behavior intention (e.g., behavior intention to not repay) differ across cultures and countries can be studied in future research.. To expand on the current findings, future research may need to examine whether additional determinants could influence intention to not repay. For example, according to Fukukawa (2002), perceived unfairness may moderate the relationship between ethical judgments and EQB. That is to say, under certain situations, consumers might perceive the potential to redress this unfair balance and so become ethically permissive, allowing the lowering of their ethical judgments. In addition, the linkage of intention to actual behavior should be further examined so as to recognize whether other factors interfere with the two associations. Finally, different or additional personality traits (e.g., Machiavellianism) and the 37.

(47) four dimensions of ethical judgments perhaps could apply to other unethical behavioral intentions.. 38.

(48) Chapter 6 Conclusions Ethical behavior on the part of both buyers and sellers is tantamount to effectiveness of the marketplace. Regardless of the degree of competition, the successful functioning of the marketplace rests on a foundation of mutually agreed-upon rules of conduct and shared interests (Solomon, 1992). Loucks (1987) argues that even though both sides of the exchange dyad can be expected to act in their own best economic self-interest, the system itself is based upon mutual trust among participating individuals and organizations. More importantly, ethical behavior on the part of both buyer and seller is implicit in establishing and continuing the relationships between the two parties. For a relationship to continue as mutually beneficial, both parties must value it. Unethical behavior by either party disrupts the relationship and produces exchanges that are both unproductive and ineffective (Morgan & Hunt, 1994).. In conclusion, our results support previous research demonstrating the importance of the relationship between the ethical judgments and unethical behavioral intentions. It appears that the ethical judgments regarding actively benefiting from illegal activities or passively benefiting at the expense of others have impacts on individual’ s intention to not repay. Additionally, the results provide compelling evidences that external LOC and risk-taking propensity can predict ethical judgments, and in turn lead to intention to not repay. External LOC can also directly affect the intention. Implications derived from this study are useful for credit card companies.. Our findings provide insight regarding the actions of consumers. Given the results, it is clear that personal factors (e.g., personality and ethical judgments) should be part of any future study concerning consumer ethics. Though consumers tend to be ethical, they are potentially worrisome groups which could have a detrimental impact on a firm’ s performance. Businesses must develop a long term strategy to deal with and overcome these obstacles. 39.

(49) Appendix A The Scales for Ethical Judgments Regarding Credit Card Use Actively Benefiting from Illegal Activities Someone (A) picks up another person’ s lost credit card and uses it. In your opinion, the above behavior is: (1) unjust : : : : : : just (2) not morally right : : : : : : morally right (3) unacceptable : : : : : : acceptable Passively Benefiting at the Expense of Others Someone (B) uses a credit card to consume, but has not received the credit card bill. He/she has no intention to check with the credit card company and still continues using the card. In your opinion, the above behavior is: (1) unjust : : : : : : (2) not morally right : : : : (3) unacceptable : : : : :. just : : morally right : acceptable. Actively Benefiting from Questionable Actions When the credit card company calls to press for payment of the credit card expenses, someone (C) declares that he/her has not received the credit card bill (although he/she has received it in fact). In your opinion, the above behavior is: (1) unjust : : : : : : just (2) not morally right : : : : : : morally right (3) unacceptable : : : : : : acceptable No Harm/ No Foul Someone (D) applies for many credit cards but hardly uses them. In your opinion, the above behavior is: (1) unjust : : : : : : just (2) not morally right : : : : : : morally right (3) unacceptable : : : : : : acceptable. 40.

數據

Outline

相關文件

remember from Equation 1 that the partial derivative with respect to x is just the ordinary derivative of the function g of a single variable that we get by keeping y fixed.. Thus

vice versa.’ To verify the rule, you chose 100 days uniformly at random from the past 10 years of stock data, and found that 80 of them satisfy the rule. What is the best guarantee

vice versa.’ To verify the rule, you chose 100 days uniformly at random from the past 10 years of stock data, and found that 80 of them satisfy the rule. What is the best guarantee

(1) The MOJ invited experts and scholars from both academia and in the field relating to combating money laundering to actively organized education and training

Reading Task 6: Genre Structure and Language Features. • Now let’s look at how language features (e.g. sentence patterns) are connected to the structure

• Teaching grammar through texts enables students to see how the choice of language items is?. affected by the context and how it shapes the tone, style and register of

In this paper, we have shown that how to construct complementarity functions for the circular cone complementarity problem, and have proposed four classes of merit func- tions for

volume suppressed mass: (TeV) 2 /M P ∼ 10 −4 eV → mm range can be experimentally tested for any number of extra dimensions - Light U(1) gauge bosons: no derivative couplings. =>