台灣大學生英文議論文中人稱代名詞使用之功能分析 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) A FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS OF PERSONAL PRONOUN USE IN ARGUMENTATION BY TAIWANESE COLLEGE STUDENTS. A Dissertation Presented to Department of English. 立. 政 治 大. National Chengchi University. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. n. v i n CPartial In h e nFulfillment hi U c g of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. by Yin-ling Chang November, 2011.

(3) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. First and foremost, my deepest and sincerest gratitude goes to my advisor, Prof. Hsueh-ying Yu, who has mentored me through the seven years‘ study, and witnessed my professional growth and personal maturity both as a doctoral student and as an English teacher. Prof. Yu showed me how to analyze and handle research problems independently, and offered me insightful comments on my drafts. Under her guidance, I have come to realize the true meaning of conducting research and successfully. 政 治 大 I would like to extend my great thanks to Prof. Li-Te Lee, who sparked my 立. completed the dissertation.. interest in research and provided me with precious suggestions during my. ‧ 國. 學. professional pursuit. I was also grateful to my colleagues, especially Prof. Carol Wu. ‧. and Prof. Beatrice Yang, for their continued morale and congeniality, from which I. sit. y. Nat. gained high impetus and vitality at most challenging times. My warmest thanks are. io. er. also dedicated to Prof. Weichen Chuang, Prof. Hosong Tang, and Prof. Lydia Tseng for their help with data analysis. I deeply appreciated Prof. Michael Cheng from. al. n. v i n C h from DepartmentUof Applied Foreign Languages Chengchi University and the teachers engchi of my school, who generously allowed me to collect their students‘ essays.. Finally, I want to thank my family, especially my parents, who have an unfailing faith in my ability and tenacity in doing graduate work. Their love and support have sustained me in the course. My achievement in the completion of the doctoral program should be accredited to them. The journey, full of thrills and frustrations, has reassured my belief and value of choosing English education as my life-long career, and equipped me with expertise for further exploit in this area. Without you all, this dissertation would not have been successfully completed. Thank you. iii.

(4) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................iii Chinese Abstract .......................................................................................................... xv English Abstract .......................................................................................................... xvi Chapter 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 Background ................................................................................................... 1. 政 治 大. Statement of the Problem .............................................................................. 3. 立. Statement of the Purpose ............................................................................... 7. ‧ 國. 學. Research Questions ....................................................................................... 8 Significance of the Study .............................................................................. 9. ‧. Organization of the Dissertation.................................................................. 10. y. Nat. io. sit. Definition of Terms ..................................................................................... 11. n. al. er. 2. Literature Review............................................................................................. 14. i n U. v. Writing as a Form of Interaction ................................................................. 14. Ch. engchi. Writer‘s Voice ....................................................................................... 15 Audience Awareness............................................................................. 16 The Role of Voice and Audience in Writing Classroom ...................... 17 Personal Pronouns ....................................................................................... 19 Overview .............................................................................................. 19 Approaches to Analyzing Personal Pronouns ...................................... 21 Pragmatic Functions of Personal pronouns .......................................... 22 First Person Singular Pronoun I ..................................................... 22 First Person Pronoun Plural We ...................................................... 23 iv.

(5) Second Person Pronoun You ........................................................... 25 Third Person Pronoun Plural They and Singular S/he .................... 26 The Co-Text of Personal Pronouns ..................................................... 28 Pronominal Shift ................................................................................. 30 Cross-Cultural Comparisons ............................................................... 31 Argumentative Writing ................................................................................. 34 Argumentative Text Genre ................................................................... 34 Effective Argumentative Writing ......................................................... 34. 政 治 大 Systemic Functional Grammar ..................................................................... 38 立 Previous Studies on Argumentative Writing ........................................ 36. Discourse-Semantic Structure .............................................................. 38. ‧ 國. 學. Lexico-Grammatical Structure ............................................................. 39. ‧. Transitivity ..................................................................................... 39. sit. y. Nat. Mood .............................................................................................. 40. io. er. Theme ............................................................................................. 41 Application of SFG to Research and Pedagogy…………… ............... 42. al. n. v i n C h Perspective ...................................................... Research from a Functional 43 engchi U. 3. Methodology .................................................................................................... 45. Participants .................................................................................................. 45 Instruments .................................................................................................. 47 The Writing Task .................................................................................. 47 Holistic Rating Scale ............................................................................ 48 Post-Writing Questionnaire .................................................................. 50 Post-Writing Oral Interview Questions ................................................ 51 Data Analysis............................................................................................... 52 Text analysis ......................................................................................... 52 v.

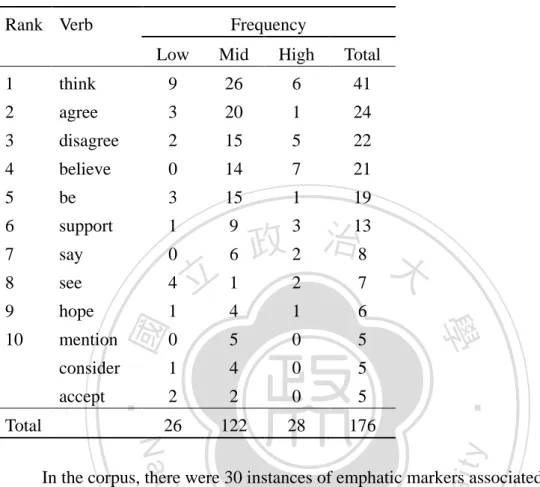

(6) Frequency Analysis ........................................................................ 53 Analysis of the Collocated Linguistic Forms ................................. 54 Principles for Coding the Collocated Forms ............................ 55 Cluster Analysis ....................................................................... 56 Analysis of Discourse Functions .................................................... 59 Analysis of Questionnaires ................................................................... 61 Analysis of Oral Interviews .................................................................. 62 4. Analysis of Pronominal Linguistic Forms and Discourse Functions ............ ..63. 政 治 大 Distribution of Different Types of Personal Pronouns ................................ 64 立 Descriptive Statistics of the Writing Samples ............................................. 63. Overall Frequency of Occurrences of Personal Pronouns ................... 64. ‧ 國. 學. Frequency Distribution in Three Groups ............................................. 67. ‧. Summary of Personal Pronoun Use and Frequency Distribution........ 68. sit. y. Nat. Analysis of Linguistic Forms and Discourse functions............................... 68. io. er. First Person Singular I ......................................................................... 69 The Use of I in Relation to Text Structure..................................... 70. al. n. v i n C h of I in Subject Linguistic Collocations Position ............................ 72 engchi U Main Verbs and Emphatics after I ............................................ 72 Modals after I ........................................................................... 73 Most Frequent Clusters with I .................................................. 74 Discourse Functions of I ................................................................ 75 The Function Distribution of Pronoun I ......................................... 77 Summary of the Use of I ................................................................ 79 First Person Plural We ......................................................................... 80 The Use of We in Relation to Text Structure .................................. 80 Linguistic Collocations of We in Subject Position ......................... 83 vi.

(7) Main Verbs and Emphatics after We......................................... 83 Modals after We ........................................................................ 84 Most Frequent Clusters with We .............................................. 85 Discourse Functions of We ............................................................. 85 The Function Distribution of Pronoun We ..................................... 89 Summary of the Use of We ............................................................. 90 Second Person Pronoun You ................................................................ 91 The Use of You in Relation to Text Structure ................................. 91. 政 治 大 Main Verbs and Emphatics after You ....................................... 94 立. Linguistic Collocations of You in Subject Position ........................ 94. Modals after You....................................................................... 95. ‧ 國. 學. Most Frequent Clusters with You ............................................. 96. ‧. Discourse Functions of You ............................................................ 97. sit. y. Nat. The Function Distribution of Pronoun You .................................. 100. io. er. Summary of the Use of You.......................................................... 101 Third Person Plural They ................................................................... 102. al. n. v i n C hin Relation to TextUStructure ............................. 103 The Use of They engchi Linguistic Collocations of They in Subject Position .................... 105 Main Verbs and Emphatics after They.................................... 105 Modals after They ................................................................... 106 Most Frequent Clusters with They ......................................... 107 Discourse Functions of They ........................................................ 108 The Function Distribution of Pronoun They ................................ 111 Summary of the Use of They ........................................................ 112. Third Person Singular S/he ................................................................ 113 The Use of S/he in Relation to Text Structure .............................. 114 vii.

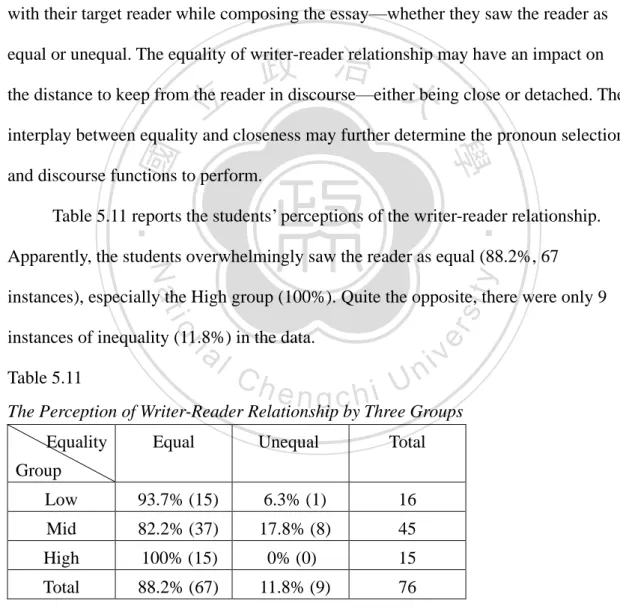

(8) Linguistic Collocations of S/he in Subject Position ..................... 115 Main Verbs and Emphatics after S/he .................................... 115 Modals after S/he.................................................................... 116 Most Frequent Clusters with S/he .......................................... 116 Discourse Functions of S/he ........................................................... 117 Summary of the Use of S/he........................................................... 118 Summary of the Chapter ............................................................................ 118 5. Analysis of Questionnaires and Interviews.................................................... 121. 政 治 大 Question 1: The Purpose of Writing ................................................... 122 立. Results and Analysis of the Questionnaires .............................................. 121. Expressing Purpose ...................................................................... 123. ‧ 國. 學. Convincing Purpose ..................................................................... 123. ‧. Assignment Purpose ..................................................................... 124. sit. y. Nat. The Choice of Personal Pronoun in Relation to Writing. io. er. Purpose ................................................................................... 124 Expressing Purpose ................................................................ 125. al. n. v i n C Purpose Convincing 126 U h e n g............................................................... i h c Assignment Purpose ............................................................... 127. Question 2: The Intended Reader ....................................................... 127 The Choice of Personal Pronoun in Relation to Intended Reader .................................................................................... 129 General Public Group ............................................................. 130 Opponents Group ................................................................... 130 Teachers/Researchers Group .................................................. 131 Question 3: The Writer-Reader Relationship ..................................... 132 Equal Relationship ....................................................................... 132 viii.

(9) Unequal Relationship ................................................................... 134 The Choice of Personal Pronoun in Relation to Writer-Reader Relationship............................................................................ 135 Equal Relationship ................................................................. 137 Unequal Relationship ............................................................. 137 Question 5: The Convincing Strategy ................................................ 138 Direct Strategy ............................................................................. 139 Indirect Strategy ........................................................................... 140. 政 治 大 Strategy .................................................................................. 142 立. The Choice of Personal Pronoun in Relation to Convincing. Direct Strategy ....................................................................... 143. ‧ 國. 學. Indirect Strategy ..................................................................... 143. ‧. Question 4: The Persuasive Effect of the Text ................................... 144. sit. y. Nat. Question 6: The Major Difficulties in Composing the Essay ............ 146. io. er. Results of Oral interview........................................................................... 148 The Choice of I .................................................................................. 148. al. n. v i n The Choice of WeC............................................................................... 150 hengchi U The Choice of You .............................................................................. 152 The Choice of They ............................................................................ 154 The Choice of S/he ............................................................................. 156 Comparison between Text Analysis and Interview Results ....................... 156 Strategic and Cultural Perspectives on Personal Pronoun Use .................. 158 The Students‘ Strategic Use of Personal Pronouns ............................ 158 Writer-Oriented Considerations ................................................... 158 Reader-Oriented Considerations .................................................. 161 Text-Oriented Considerations ....................................................... 163 ix.

(10) Conclusion of the Strategic Use ................................................... 164 Cultural Factors Involved in Personal Pronoun Use .......................... 164 A Humane Approach to Argumentation ....................................... 165 The On-the-Same-Boat Reader .................................................... 166 Little Use of Impersonal One ....................................................... 167 Mixed Strategies to Persuasion .................................................... 168 Different Pragmatic Meanings of Personal Pronouns .................. 169 6. Conclusion ..................................................................................................... 171. 政 治 大 Question 1: The Overall Frequency and Distribution of Personal 立. Answers to Research Questions ................................................................ 171. Pronouns ....................................................................................... 171. ‧ 國. 學. Overall Frequency and Distribution ............................................. 171. ‧. Variance among Groups in Distribution ....................................... 172. sit. y. Nat. Question 2: The Most common Linguistic Forms Collocated with. io. er. Personal Pronouns ........................................................................ 172 Question 3: The Discourse Functions Fulfilled by Types of Personal. al. n. v i n Ch Pronouns ....................................................................................... 174 engchi U Discourse Functions and Types of Personal Pronouns................. 174 Variance among Groups in Function Use..................................... 175. Question 4: The Students‘ Perceptions of Argumentative Writing .... 175 Questionnaire Results................................................................... 175 Oral Interview Results.................................................................. 176 Pedagogical Implications .......................................................................... 177 Teaching Suggestions ................................................................................ 182 Limitations of the Study ............................................................................ 184 Directions for Future Research.................................................................. 185 x.

(11) Appendixes A. Argumentative Writing Task ........................................................................ 187 B. Argumentative Writing Task (Chinese version) ............................................ 188 C. Holistic Rating Scale..................................................................................... 189 D. Post-Writing Questionnaire .......................................................................... 192 E. Post-Writing Questionnaire (Chinese version) ............................................. 194 F. Post-Writing Oral Interview Questions ......................................................... 196 G. Informed Consent Form................................................................................ 197. 政 治 大 I. Collocated Linguistic Forms and Illustrative Examples ................................ 199 立. H. Informed Consent Form (Chinese version) ................................................... 198. J. The Categorization Schemes of Discourse Functions and Illustrations ......... 200. ‧ 國. 學. References ................................................................................................................. 202. ‧. Vita ........................................................................................................................... 219. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xi. i n U. v.

(12) LIST OF TABLES Table. 4.1. Number of Papers and Words for Each Group…………………….... 63. 4.2. The Raw Number, Percentage, and Normalized Frequency per 100 Words…………………………………………………………… 65. 4.3. Frequency of Personal Pronoun per 100 Words (%)…………........... 67. 4.4. Density of I in Relation to Text Structure (per 100 Words)……….... 70. 4.5. Main Verbs that Most Frequently Collocated with I……….............. 73. 4.7. Top 10 Clusters Associated with I………………………………….. 74. 學. ‧ 國. 4.6. 政 治 大 Modal Distribution after I…………………………………………... 74 立 Distribution of Functions of I (Percentage and Raw Number) …….. 78. 4.9. Density of We in Relation to Text Structure (per 100 Words) ……... 80. 4.10. Main Verbs that Most Frequently Collocated with We……………... 83. 4.11. Modal Distribution after We………………………………………… 84. 4.12. Top 10 Clusters Associated with We………………………………... 85. 4.13. 89. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. v i n C h of We (Percentage Distribution of Functions and Raw Number) ….. engchi U n. 4.14. ‧. 4.8. Density of You in Relation to Text Structure (per 100 Words) …….. 92. 4.15. Main Verbs that Most Frequently Collocated with You…………….. 95. 4.16. Modal Distribution after You……………………………………....... 95. 4.17. Top 7 Clusters Associated with You………………………………… 96. 4.18. Distribution of Functions of You (Percentage and Raw Number) …. 101. 4.19. Density of They in Relation to Text Structure (per 100 Words) …… 103. 4.20. Main Verbs that Most Frequently Collocated with They…………… 105. 4.21. Modal Distribution after They………………………………………. 106. xii.

(13) 4.22. Top 10 Clusters Associated with They……………………………… 107. 4.23. Distribution of Functions of They (Percentage and Raw Number) ... 111. 4.24. Density of S/he in Relation to Text Structure (per 100 Words) ……. 115. 4.25. Main Verbs that Most Frequently Collocated with S/he……………. 115. 4.26. Top 6 Clusters Associated with S/he………………………………... 116. 4.27. The Linguistic Forms and Discourse Functions Associated with Types of Personal Pronouns……………………………………. 120. 5.1. The Purposes of Writing by Three Groups (Percentage and Raw. 政 治 大 Density of Pronouns in Relation to Writing Purpose……………….. 125 立 Number) ……………………………………………………..…. 122. 5.3. Pronoun Use (%) by Three Groups for Expressing Purpose……….. 125. 學. ‧ 國. 5.2. Pronoun Use (%) by Three Groups for Convincing Purpose………. 126. 5.5. Pronoun Use (%) by Three Groups for Assignment Purpose………. 127. 5.6. The Intended Readers Chosen by Three Groups (Percentage and. ‧. 5.4. sit. y. Nat. io. er. Raw Number)…………………………………………………… 128 5.7. Density of Pronouns in Relation to Reader Group…………………. 129. 5.8. 130. v i n C Three Pronoun Use (%) by for General Public…………….. U h e nGroups i h gc n. 5.9. al. Pronoun Use (%) by Three Groups for Opponents…………………. 131. 5.10. Pronoun Use (%) by Three Groups for Teachers/Researchers…….... 131. 5.11. The Perception of Writer-Reader Relationship by Three Groups…... 132. 5.12. Density of Pronouns in Relation to Writer-Reader Relationship…… 135. 5.13. Pronoun Use (%) by Three Groups for Equal Relationship………... 137. 5.14. Pronoun Use (%) by Three Groups for Unequal Relationship……... 138. 5.15. The Convincing Strategies Adopted by Three Groups……………... 138. 5.16. Density of Pronouns in Relation to Convincing Strategy…………... 143. xiii.

(14) 5.17. Pronoun Use (%) by Three Groups for Direct Strategy…………….. 143. 5.18. Pronoun Use (%) by Three Groups for Indirect Strategy…………... 144. 5.19. Perception of Text Persuasiveness by Three Groups……………….. 145. 5.20. The Difficulties in Composing the Essays by Three Groups……….. 147. 5.21. Consistent Findings from Text Analysis and Oral Interview……….. 157. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xiv. i n U. v.

(15) 國立政治大學英國語文學系博士班 博士論文提要. 論文名稱:台灣大學生英文議論文中人稱代名詞使用之功能分析 指導教授:尤雪瑛 教授 研究生:張銀玲 論文提要內容:. 治 政 (一種明顯的人際關係標記)在議論文中的使用功能來探討不同程度的台灣大學 大 立 生如何使用人稱代名詞建構作者與讀者之間的關係。本研究的第一部份著重在七 為了呼應將人際層面融入寫作教學的趨勢,本論文將透過分析人稱代名詞. ‧ 國. 學. 十六篇文章的文本分析。首先,這些文章按照評分結果將其分成高、中、低三組, 然後分析人稱代名詞最常出現的搭配語言形式,並歸納出不同人稱代名詞的篇章. ‧. 功能。第二部份則是分析學生問卷及訪談學生,藉以作進一步的闡述。問卷的目 的在找出學生對議論文寫作的看法,而訪談學生則是想找出使用不同人稱代名詞. y. Nat. sit. 的原因。本研究發現不同程度的三組學生在人稱代名詞的整體使用數量、種類、. er. io. 及頻率分配上都有不同,程度高的一組明顯少於中間程度及較低組。同時,結果. al. n. v i n Ch 使不同的篇章功能,而且不同程度的學生在功能運用上也會有所差異。整體而 engchi U. 也顯示這些學生會搭配不同的語言形式(例如動詞、助動詞、加強標記等)來行. 言,低組同學呈現較多的自我投射,中間組同學比較注重與讀者和其他外人的關 係,而高組同學在呈現觀點時較為客觀。在選擇人稱代名詞時,學生會從自己本 身、讀者、文章寫作等三方面的相互關係作出考量,決定採取主觀或客觀的觀點、 表達權威或謙卑的態度、顯示親近或疏離的關係、使用直接或間接的策略。大致 上來說,這些學生使用較多的人性訴求來凝聚跟讀者之間的關係,同時也強化自 己論點的力道。這樣的策略充分反映出台灣文化中的人道主義和集體主義。本研 究發現學生在議論文寫作中會以功能和人際關係為導向來選擇和使用人稱代名 詞。 關鍵字:人稱代名詞、人際關係標記、篇章功能. xv.

(16) ABSTRACT In response to the call for the incorporation of interpersonal dimension into the writing pedagogy, this study provides a functional analysis of personal pronouns—an explicit interpersonal marker—used in argumentative texts by Taiwanese college students. The purpose is to see how students of different proficiency levels construct the writer-reader relationship through personal pronouns during the composition. The first part of the study centers on the analysis of 76 learner essays. They are first rated and sorted into three groups of different quality—High, Mid, and Low. Later, the. 政 治 大 functions personal pronouns 立fulfill in contexts are also identified. The results of the. linguistic forms associated with personal pronouns are examined, and the discourse. ‧ 國. 學. text analysis are further supplemented by the post-writing questionnaires and the oral interviews on students to obtain more in-depth discovery and interpretation. While the. ‧. questionnaire aims to reveal how the students perceive argumentative writing, the. sit. y. Nat. interview intends to find out the reasons for their choices of personal pronouns.. n. al. er. io. The results have shown that the use of personal pronouns in the three groups. i n U. v. differs in quantity, type and distribution. The High group writers use significantly. Ch. engchi. fewer pronouns than the other two. Moreover, the students use personal pronouns with salient accompanying linguistic forms (e.g. verbs, modals, emphatic markers) to perform various discourse functions, and students of different levels also vary in maneuvering the functions. Overall, the Low group writers tend to be more self-involved, and the Mid group writers are more likely to include in-group and out-group members in discourse. The High group writers, however, present their arguments more objectively. In selecting personal pronouns, the students usually take account of the interrelationship among the writer, the reader and the text, on whose basis the alternatives between subjectivity and objectivity, authority and modesty, xvi.

(17) intimacy and detachment, or directness and indirectness are weighed. In general, the students use more personal appeals to achieve mutual solidarity with the reader and to intensify their convictions as well, which reflects humaneness and collectivism that have been highly valued in Taiwanese culture. The study has found that the students‘ strategic choices of personal pronouns in argumentative writing are usually functionally and interpersonally-oriented.. Key Words: Personal Pronouns, Interpersonal Marker, Discourse Functions. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xvii. i n U. v.

(18) CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION Background Writing is a cultural activity embedded in a wider social context, whose purpose is for communication and interaction (Grabe & Kaplan, 1996; Hyland, 1998; Hyland, 2002c; Intaraprawat & Steffensen, 1995; Kuo, 1999; Ramanathan & Kaplan, 1996). In other words, any act of writing is context-based and socially constructed with its. 政 治 大 people. A proficient writer, therefore, has to know the rhetorical situation, project 立. conventionalized forms and assumptions recognized by a particular community of. himself in the writing, address the audience, and interact appropriately and effectively. ‧ 國. 學. in a specific culture (Wu & Rubin, 2000).. ‧. In a post-process writing period (Kroll, 2003), it is claimed that an effective. sit. y. Nat. writing pedagogy should include several essential elements: the writer (awareness of. io. er. the composing process and knowledge of the topic), the text (the purpose of the writing and consciousness raising of rhetorical and lexico-grammatical forms) and the. al. n. v i n C and reader (knowledge of engagement strategies) (Hyland, 2002a). The h einteraction ngchi U. multi-dimensional integration of writer-, reader-, and text-oriented instruction reflects the view that writing is a joint endeavor between the writer and the reader, requiring the writer to recognize the text requirement and the reader‘s potential responses. Therefore, how the writer engages and negotiates the reader while simultaneously achieving his writing purpose is an area of study that have sparked teachers and researchers great interests (Camiciottoli, 2003; Hyland, 1998, 2001a, 2002a; Thompson, 2001; Thomspon & Theltela, 1995). In response to the trend, there has been a call for the incorporation of interpersonal dimension of writing in the classroom, where the focus has expanded 1.

(19) 2. beyond the textual dimension to include an interactional one. To explicitly mark the interpersonal features, metadiscourse markers are often introduced in that they help the writer organize the propositional content on one level, and facilitate the reader-writer interaction on the other (Abdi, 2002; Crismore, 1984; Hyland, 1998, 2002a, 2002d; Krause & O‘Brien, 1999). The term ―metadiscourse‖ is defined as ―discourse about discourse,‖ which does not add propositional information but ―help our readers organize, classify, interpret, evaluate, and react to such materials‖ (Vande Kopple, 1985, p. 83). Despite the different sets of taxonomy proposed by researchers,. 政 治 大 and interpersonal metadiscourse. While textual metadiscourse markers such as logical 立 metadiscourse is generally categorized into two major groups: textual metadiscourse. connectives and sequencers are used to organize and guide propositional content,. ‧ 國. 學. interpersonal metadiscourse markers such as hedges, attitude markers, and personal. ‧. pronouns allow the writer to explicitly project his stance and attitude, and involve the. sit. y. Nat. audience through the unfolding text (Connor, 1996; Jalilifar & Alipou, 2007; Vande. io. er. Kopple, 1985; Williams, 1981). With metadiscourse markers, the writer is doing more than just creating a textually cohesive text; he is further maneuvering his position and. al. n. v i n interaction with the reader. FromCthis perspective, metadiscourse is interpersonal in hengchi U nature (Hyland & Tse, 2004; Thompson 2001; Thompson and Thetela, 1995).. Researchers have attempted to identify the overt linguistic resources for signaling interpersonal positioning in academic texts. One of the major contributors is Hyland (2005c), who, having examined academic writing across disciplines, proposes an interactional model, where both the writer‘s stance and the reader‘s engagement are attended to. In this model, the writer‘s stance can be expressed by hedges (indicating the writers‘ commitment to the propositional information), emphatics (emphasizing the force of proposition), attitude markers (expressing the writer‘s affective attitude to the proposition), and self-mention (reflecting the degree of.

(20) 3. importance of the writer, encoded by I or we). On the other hand, reader engagement is encoded by reader pronoun you, directives (including imperatives such as ―consider that‖ or ―note that,‖ obligation modals, and adjectival predicates such as ―it is important to understand‖), questions (real or rhetorical), appeals to shared knowledge, and personal asides (addressed to the reader, e.g. ―as you know‖). The writer-oriented features are aimed to present the writer‘s credibility, confidence and evaluations, whereas the reader-oriented features serve to claim solidarity and explicitly maneuver the reader into a particular line of argument.. 政 治 大 Statement of the Problem 立. ‧ 國. 學. Although the interpersonal dimension of writing has been increasingly emphasized in writing pedagogy, examinations of the current composition textbooks. ‧. adopted in the tertiary classroom in Taiwan have revealed that there seems to be no. y. Nat. io. sit. comprehensive coverage of interpersonal features in the presentation of argumentative. n. al. er. genre (e.g. Donald, 1996; Oshima & Hogue, 2006; Smalley, et al., 2001). In these. i n U. v. materials, students are told to take a stand of an issue, be acutely aware of the reader,. Ch. engchi. and try to understand the opponent‘s points of view (Smalley, et al., 2001). There are discussions on how to refute and concede the oppositions, and how to organize the arguments logically. Students are also advised to be ―objective‖ in presenting their arguments, and thus, personal pronouns—very inter-subjective markers—should be discouraged. But the reasons for dealing with the reader‘s counterclaims are far from clear. The strategies for making the writer as an arguer and a persuader are not emphasized, either. The concepts of objectivity and subjectivity could be also abstract to students. Students may not have clues to any linguistic forms or discoursal norms that can be used for explicit marking of subjectivity and objectivity..

(21) 4. Some books (e.g. Donald, et al., 1996) further point out the powerful effect of using emotional appeals in text, such as vivid and moving examples. In addressing the reader, students are reminded of being courteous and stating their ideas in a language as simple and clear as they can make for the audience to understand. However, there is no guidance on how to construct arguments carrying emotional appeals, nor is there any information of how many examples should be included in order to ensure the best effect. Moreover, there is no illustration of what it means to be ―polite‖ and ―simple‖ in text construction. Obviously, there are still parts that have not been fully accounted. 政 治 大 be put together. This is the point of departure that this study intends to move from. 立. for in the textbooks as well as in the classroom, and there are still missing puzzles to. On the other hand, it has been found that in general, Anglo-American texts are. ‧ 國. 學. comprised of more explicit textual rhetoric and are more reader-oriented, while the. ‧. texts of other cultures focus more on propositional content (Crismore, et al., 1993).. sit. y. Nat. Also, L2 writers use far less interpersonal resources than textual ones in research. io. er. articles (Gao, 2005), but more professional and experienced writers tend to use a higher number of interpersonal markers, especially engagement markers and. al. n. v i n C h Even though L2 U self-mentions (Hyland & Tse, 2004). writers have acquired engchi. native-like proficiency in academic writing, they seem to be less interactive in their. academic discourse (Lau, 2004; Hyland & Tse, 2004; Yang, 2006). Clearly, compared with native writers, the linguistic resources for signaling interpersonal relationship are found to be less mature and quite limited in the texts written by L2 writers. As Grabe (2003) argues, in the reading-writing research, ―cultural and language differences among L2 students create complexity that are not accounted for by L1 research‖ (p. 242), such as the sense of author and reader, preferences for text organization, differing cultural socialization, belief systems and functional uses of writing. Silva (1993) also contends that for effective writing instruction, teachers have.

(22) 5. to grasp a clear and comprehensive understanding of the unique nature of L2 writing and their noticeable contrasts with the target language and culture. It follows that there is a need to analyze learner writing samples in order to understand the extent to which student writers are familiarized with interpersonal features and how they deal with them in different contexts. Informed by the learner corpora, teachers will be able to emphasize the essential features that are often overlooked due to different cultural conventions, and to evaluate the writing difficulties L2 students may encounter. Among all the rhetorical devices for signaling interpersonal relationship in text,. 政 治 大 the most explicit and familiar markers to students (Crismore, et al., 1993; Hyland, 立. personal pronouns, which serve to address both the writer and the reader, are probably. 2002a, 2005a, 2005c; Vande Kopple, 1985). Although personal pronouns have been. ‧ 國. 學. discouraged in formal academic writing and in composition textbooks, recent research. ‧. into academic research papers (e.g. Harwood, 2005a, 2007; Hyland, 2001a, 2002b,. sit. y. Nat. 2005b; Inigo-Mora, 2004; Kuo, 1999) have revealed that the use of personal pronouns. io. er. is not uncommon, and that they are well distributed into various sections of research papers, each fulfilling different discourse functions across genres and disciplines.. al. n. v i n C h and textbooks doUnot satisfactorily address the Unfortunately, composition research engchi. issue, nor do teachers pay due attention to this specific interpersonal facet in writing class. Moreover, despite a bourgeoning body of research has started to explore the use of personal pronouns and other interpersonal features in published and unpublished academic writing across disciplines (e.g. Duenas, 2007; Gordon, 2007; Harwood, 2005a, 2005b; Hyland, 2001b, 2002b; Inigo-Mora, 2004; Kuo, 1999; Martinez, 2005; Vassileva, 1998), lectures or classroom talk (e.g. Dafouz, et al., 2007; Fortanet, 2004; Morell, 2004; Rounds, 1987), political interviews (e.g. Fetzer & Bull, 2008), sports commentary (Kuo, 2003) or dissertation defense (Recski, 2005), investigations of the.

(23) 6. actual use of personal pronouns by nonnative writers of English remain inadequate, particularly in the area of school writing (Cobb, 2003; Hyland, 2005a; McCrostie, 2008, Petch-Tyson, 1998). Furthermore, constrained by the genres, the previous studies have mostly focused on the use of self-mention I and we in academic writing, and audience-addressed you has been cursorily explored. Comparatively, very little attention has been paid to the third personal pronouns they and s/he (e.g. Kamio, 2001; Kuo, 2002). Therefore, more research is needed to examine the EFL undergraduate writers for their understanding and management of writer-reader relationship through. 政 治 大 On top of that, the linguistic features associated with personal pronouns have 立. the use of personal pronouns of different types.. not been a major focus, either. Research has centered on the semantic references in. ‧ 國. 學. context, pronominal shifts, and the discourse or pragmatic functions performed by. ‧. these personal pronouns. Only a handful of research has touched upon the combining. sit. y. Nat. collocational analysis—the associated lexico-grammatical or syntactical forms (e.g.. io. er. Dafouz, et al., 2007; Flottum, et al., 2006; Gledhill, 2000; McCrostie, 2008). Still little is known about how EFL writers make linguistic choices in the construction of. al. n. v i n C htowards the propositional their attitudes, beliefs and opinions content presented. engchi U. Furthermore, analysis of personal pronoun functions among the numerous. corpus-based studies has mainly been provided by the researchers themselves. There is a lack of first-hand information from the writers themselves about why they choose a certain personal pronoun in a specific discourse context (Harwood, 2007). It will be very insightful to interview L2 writers for more direct information. For these reasons, it seems worthwhile to extend the previous research by considering how Taiwanese EFL students use personal pronouns to perform multiple discourse functions in order to achieve the overall impression and effect of the text. Also, there is a need to examine the collocating discursive features that contribute to.

(24) 7. the characterization of discourse functions. In addition to the written text analysis, the incorporation of informant interview and questionnaire would help construct a more complete picture. The understanding of all these aspects is believed to provide a basis for future academic writing instruction, especially in the management of interpersonal interaction.. Statement of the Purpose. Given the interactive nature of texts, establishing a connection with the reader. 政 治 大. is of paramount importance in creating academic writing and argumentative writing. 立. (Hyland, 2005b). The purpose of the study, therefore, is to investigate how Taiwanese. ‧ 國. 學. EFL college students establish their interpersonal relations with the reader while constructing their arguments for its persuasive effects in argumentative writing.. ‧. Specifically, this study focuses on when, where, how, and why person pronouns—a. y. Nat. io. sit. type of interpersonal metadiscourse marker—are employed to present the writer‘s. n. al. er. voice and engage the reader. Furthermore, it also intends to explore whether the. i n U. v. choices of personal pronouns and their associated linguistic forms vary among. Ch. engchi. students of different proficiency levels.. In this study, all types of personal pronoun (I, we, you, they, and s/he) will be dealt with in order to get a complete portrait of how Taiwanese EFL learners interact with the reader during the composing process. To this end, an argumentative essay format is selected because this genre has been identified as crucial component of college writing (Crowhurst, 1990; Ramanathan & Kaplan, 1996), and it involves a stronger interaction and dialogue with the audience as well as the writer‘s personal voice (Connor, 1987; Zainuddin & Moore, 2003; Williams, 1981). Writers are expected to employ explicit interpersonal markers to reflect their own positions.

(25) 8. towards both the content and the reader, and further influence cooperation and identification with the reader for effective text persuasiveness. This study sees personal pronouns as a rhetorical device, whose use is contextually-bound and fulfills diverse communicative purposes. A pragmatic choice of a certain personal pronoun and its clustering linguistic forms encodes the writers‘ attitudes, beliefs and opinions towards the proposition presented and the audience addressed.. 政 治 大. Research Questions. 立. To respond to the question of how Taiwanese EFL learners build the bond with. ‧ 國. 學. the reader in argumentative writing by personal pronouns, the following four major questions are addressed:. ‧. 1. What are the overall frequency and distribution of different personal. y. Nat. io. sit. pronouns used by Taiwanese EFL college students in argumentative writing?. n. al. er. Furthermore, do the frequency and distribution vary among students of various proficiency levels?. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 2. What are the most common lexico-grammatical forms associated with each type of personal pronoun, including lexical verbs, modals, emphatic markers, attitude markers, and clusters? 3. Together with the collocated linguistic forms, what discourse functions does each type of personal pronoun perform in the argumentative essay? Is there any difference in the distribution of functions among groups of various proficiency levels? 4. How do Taiwanese EFL students perceive argumentative writing and writer-reader relationship in text? What are their reasons for choosing different personal pronouns?.

(26) 9. While question 1 presents the overall picture of pronoun use in EFL learner corpus, question 2 deals with the lexico-grammatical level, the choice of which realizes the communicative functions the writer aims at. Based on the analysis of question 2, question 3 addresses the discourse-semantic level of language use—how forms and functions are inter-related. The answer to question 4 is mainly provided by the post-writing questionnaires and student oral interviews for first-hand information and discovery.. 政 治 大. Significance of the Study. 立. This study provides a multi-dimensional analysis of personal pronouns in. ‧ 國. 學. argumentative texts by exploiting both from lexico-grammatical (linguistic forms) and discourse-semantic (discourse functions) levels. First of all, the analysis of frequency,. ‧. functions and associated linguistic forms will reveal what college writers actually do. y. Nat. io. sit. with personal pronouns—their perceptions, linguistic choices, and performance. The. n. al. er. text analysis will also expose how students strategically use personal pronouns to. i n U. v. express their own voice and simultaneously engage the reader. It may further explain. Ch. engchi. how linguistic choices and function preferences are influenced by Taiwanese cultural norms and rhetorical conventions. Moreover, insights into the variations in personal pronoun use among groups of different proficiency levels will indicate what differentiates a good-quality argumentative essay from a low-quality one. More broadly, this study is to bridge the current gap in writing instruction and transcend from writer-oriented approach to the inclusion of reader-oriented perspective in the composition of texts. The results will inform teachers of the missing puzzles that should be put into the picture of ESL/EFL writing instruction. As a consequence, teachers will be in a better position in designing appropriate activities to.

(27) 10. enhance their students‘ management of personal interaction in argumentative writing with the aid of pronouns and other interpersonal markers such as modals and attitude markers. A good command of argumentative genre in the interpersonal aspect will help students move to the next stage of academic writing more smoothly and successfully. Finally, the present study gains insights into EFL learner writing output, which is expected to form a basis for future contrastive interlanguage analysis. Although it can make no claims to provide generalizations about pronoun use by all EFL learners,. 政 治 大 overall patterns in the Taiwanese cultural context and to add an interpersonal 立. it really intends to provide teachers and researchers alike with an understanding of the. dimension into the writing classroom.. ‧ 國. 學. Nat. y. ‧. Organization of the Dissertation. io. sit. The structure of the dissertation is as follows: In Chapter 2, a review of the. n. al. er. literature on current writing pedagogy and personal pronouns is presented. There is a. i n U. v. detailed discussion on approaches to analyzing personal pronouns, and the pragmatic. Ch. engchi. functions performed by all types of personal pronouns that have been concluded from academic and school writing research. The examination is followed by an overview of argumentative genre—its measurement of quality and the cross-cultural comparison of rhetorical strategies employed by native and nonnative writers. The last part introduces Systemic Functional Grammar, from which the metadiscourse theory is drawn. The focus is on how the meanings of a language are realized by the lexico-grammatical forms, for example, subjects, verbal constructions, adjuncts, etc. The student profiles and the study methodology are portrayed in Chapter 3, including the instruments adopted, the process of data collection, and the data analysis..

(28) 11. Some criteria relevant to data scrutiny are explained by examples. Chapter 4 presents the results of the student text analysis. It first reports the descriptive statistics of the writing samples, including the overall frequency of occurrence and distributions of personal pronouns. Next, the examination of linguistic forms associated with types of personal pronouns is conducted. Following the two sections is the identification of the discourse functions realized by different personal pronouns. Chapter 5 reports the questionnaire results that reflect the students‘ perceptions of argumentative writing and the writer-reader role relationship. There is also an. 政 治 大 use. Then, the results of oral interviews will be offered. The main focus is on why the 立. investigation of the relationship between each answer category and personal pronoun. students choose to or not to use specific personal pronouns in a particular context.. ‧ 國. 學. Finally, the integrated findings on the students‘ strategic choices of personal pronouns. ‧. and the cultural perspectives revealed in the data are presented.. sit. y. Nat. The final Chapter 6 concludes the study by summarizing the research findings. io. er. in relation to the four research questions. Some pedagogical suggestions are subsequently made to the writing teachers in L2 classroom. The last part proposes. al. n. v i n C hof making the understanding directions for future study, in hopes of personal pronoun engchi U. use more global and complete.. Definitions of Terms. The definitions of the key terms used in this study are as follows: Metadiscourse marker An explicit signal that does not add propositional information to the discourse but rather helps the writer organize the content and facilitate the reader-writer interaction. One type is textual marker, which contributes to the text.

(29) 12. organization, and the other is interpersonal marker, which attends to both the writer‘s projection and reader engagement. Attitude marker An interpersonal marker that expresses the writer‘s attitudes to and evaluations on the propositions, such as importantly, unfortunately, amazingly, interestingly, etc. Emphatic marker An interpersonal marker that serves to reinforce the entire proposition,. 政 治 大 strongly, firmly, definitely, deeply, etc. 立. exaggerate the state of affairs, and project credible image of authority, such as. Modal. ‧ 國. 學. An item used with a verb to convey ideas of possibility or necessity. Each. ‧. modal can have two different types of meaning—epistemic and deontic. An. sit. y. Nat. epistemic modal expresses possibility or prediction of occurrences, or indicate. io. of ability, permission and obligation.. n. al. Ch. Systemic Functional Grammar (SFG). engchi. er. the writer‘s commitment to a proposition. A deontic modal expresses an attitude. i n U. v. A linguistic theory that sees language as a tool of making meanings, and the process involves a series of choices from a lexico-grammatical system of linguistic resources. What makes SFG distinctively different from the other approaches is its functional view of language, whose use is influenced by the social and cultural contexts. Mood In SFG, Mood is the element of a language that enables the writer to express his attitudes and influence the attitudes or behaviors of the reader so as to establish the social relationship. It is composed of the subject and finite (e.g. modal.

(30) 13. operator, positive/negative polarity). For example, in the clause ―Bob could help you with the math problems,‖ the constituent ―Bob could‖ is termed as Mood of the clause, whereas the rest of the clause ―help you with the math problems‖ is labeled as Residue. Transitivity In SFG, Transitivity is the element of a language which concerns ―who did what to whom in what circumstances.‖ It is mainly about how the meanings of the outside world are represented through types of verb process and participant. 政 治 大 the subject ―Bob‖ is the participant—an actor, and the verb ―help‖ is a material 立. roles. For example, in the clause ―Bob could help you with the math problems,‖. (action) verb.. ‧ 國. 學. Theme. ‧. In SFG, Theme is the element of a language which comes first in a clause and. sit. y. Nat. serves as the departure of the message—what the clause is going to be about. A. io. er. clause may contain three kinds of themes: topical, interpersonal, and textual. For example, in the clause ―And maybe Bob could help you with the math. al. n. v i n C―and‖ problems,‖ the conjunction textual U theme, whereas the adverb h e nis the i h gc. ―maybe‖ is the interpersonal theme. The subject ―Bob‖ is the topical theme. The rest of the clause ―could help you with the math problems‖ is called as Rheme. Co-text The contiguous lexical or linguistic items that surround the key word in context..

(31) CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW. An inquiry into personal pronoun use in students‘ texts needs to draw on some theoretical constructs, empirical results and pedagogical applications that have been established for the past few decades. The aim of this chapter, therefore, is to review the role of personal pronouns in the interactive writing paradigm, and also to present a conceptual framework in which personal pronouns are grounded. First, the view of. 政 治 大 features—writer‘s voice and audience awareness. Then, the pragmatic functions of 立. writing as a form of interaction is provided, focusing on two essential. personal pronouns will be closely reviewed, followed by empirical studies on personal. ‧ 國. 學. pronoun use in academic and school writing, oral discourses, and other genres. Next,. ‧. the argumentative genre required of the study is introduced, and the measurements of. sit. y. Nat. writing quality are reviewed. Finally, the theoretical construct of Systemic Functional. io. er. Grammar, from which the metadiscourse theory is developed, will be presented. The chapter will conclude with the approach the present study adopts.. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Writing as a Form of Interaction. For the past few decades, writing paradigm has shifted from text-oriented approach to writer-oriented approach and currently to social constructivism approach (Matsuda, 2003). The traditional text-oriented approach in the 1960s focuses on the forms and written products. In the 1970s, influenced by L1 writing research on composing process, a writer-oriented approach was developed. It describes writing as an expressive and cognitive process, with an emphasis on the cycling procedures of revising, editing, and feedback given both by the teacher and peers (Flower & Hayes, 14.

(32) 15. 1981; Frodesen & Holten, 2003; Grabe & Kaplan, 1996; Johns, 2003). A more recent trend sees writing as a social activity situated in a culturally defined context. The transitions to the social stage of writing in 1980s and discourse community stage in 1990s point to the fact that there is an increasing stress on discourse communities and the role of social construction, especially in academic and professional contexts (Grabe & Kaplan, 1996; Johns, 1990). The social context defines the meaning and purpose of writing, and thereby confines the writing conventions a writer has to follow. The writer, with his intentions to convey, is expected to maneuver the. 政 治 大 in response to the needs of the reader in the defined discourse (Hyland, 2002a). The 立. messages in a conventionally-accepted fashion and more importantly, to build rapport. appropriateness and effectiveness of messages are hence determined by the extent to. ‧ 國. 學. which the writer balances his purposes with the reader‘s potential responses and. ‧. cultural frames.. sit. y. Nat. Simply put, writing is not just the expression of the writer‘s personal. io. er. experiences and propositions; it also performs an interpersonal function in that it maintains the expected relationship between the writer and the reader, and even with. al. n. v i n Cand the members in a broader cultural community. In other words, writing is h ediscourse ngchi U. an act of negotiation between the writer and the reader for achieving a certain. common communicative purpose. It is seen as a dialogic nature of interaction—a form of social communication (Beaugrande and Dressler, 1981; Carrell, 1987; Thompson, 2001).. Writer’s Voice. The concept of ―textual interaction‖ (Kim, 2009) is demonstrated by two major features in writing: (1) writer‘s voice and (2) audience awareness (Hyland, 2005b)..

(33) 16. Voice, although diversely defined, is strongly associated with the writer‘s essential inner self and personal identity (Matsuda & Tardy, 2007). Ramanathan & Atkinson (1999) further link voice to the ―ideology of individualism,‖ and define the notion as a ―linguistic behavior which is clear, overt, expressive and even assertive and demonstrative‖ (p.48), indicating the writer‘s unique and distinctive personal authority. By explicitly and clearly voicing his opinions and evaluations, the writer constructs credible representation of himself and his arguments, making himself recognized by members of his discourse community (Hyland, 2002b).. 政 治 大 markers of stance (Breeze, 2007), which convey how the writer relates himself to the 立 Authorial voice in writing has been mainly expressed through the linguistic. content message, both personally and socially, and how he emotionally interacts with. ‧ 國. 學. his audience—distantly or intimately (Reilly, et al., 2005). For example, personal. ‧. pronoun I highlights the writer‘s presence in discourse. The use of hedging device (e.g.. sit. y. Nat. perhaps, someone, anything) can decrease the writer‘s responsibility for the truth. io. er. value of claims and display his hesitation, uncertainty or indirectness (Crismore & Vande Kopple, 1988; Crompton, 1997; Hinkel, 2005; Salager-Meyer, 1994).. al. n. v i n C h (e.g. will, must, clearly, Conversely, intensifiers or emphatics always) can imply engchi U. certainty or emphasize the force of accompanying propositions (Brown & Levinson, 1987; Hinkel, 2005; Lau, 2004; Levinson, 1987). Attitude markers (e.g. agree, prefer, essential, unfortunately) reflect the writer‘s affective attitude to propositions (Hyland, 2005a). These rhetorical devices altogether express the writer‘s personal voice with a strengthening or weakening force (Dafouz-Milne, 2008). Audience Awareness Of equal importance attached to effective interactive writing is the notion of audience awareness—how the writer connects to his reader by recognizing his.

(34) 17. presence and engaging him in discourse (Ramanathan & Kaplan, 1996). In fact, the writer‘s self-presentation hinges greatly on his awareness of audience. The recognition of audience presence marks the distinction of what Bereiter and Scardamalia (as cited in Grabe & Kaplan, 1996) term ―knowledge telling‖ and ―knowledge transforming‖ in their writing process model. Less mature writers tend to focus on the topic alone and strive for self-expression. The ideas that they express are retrieved from their long-term memory and transferred directly into the written text. However, expert writers take both their writing purposes and audience into account.. 政 治 大 conflict between their ideas and the rhetorical goal. Therefore, they are more capable 立 The ideas retrieved from memory are transformed by their efforts to resolve the. of creating an internal image of the reader, responding to the audience‘s expectations. ‧ 國. 學. and objections, and taking adaptive moves to present more persuasive arguments. ‧. (Zainuddin & Moore, 2003).. sit. y. Nat. As with authorial voice, audience awareness in the text can be overtly signaled. io. er. by some linguistic forms, such as reader pronoun you, questions and directives (Hyland, 2005b, 2005c). Pronoun you explicitly marks the reader‘s presence, and. al. n. v i n questions have a direct appeal inCbringing the reader into h e n g c h i U a dialogue. The writer could either challenge the reader into thinking about the topic or encourage the reader to. accept the direction the text is taking (Thompson, 2001). Questions can also function as a distancing and hedging technique or serve to refute other authors or theories (Webber, 1994, p.266). Directives, also contributing to the dialogic dimension, instruct the reader what to see and are often accompanied by obligation modals (Hyland, 2005b). The Role of Voice and Audience in Writing Classroom Both writer‘s voice and audience awareness are recognized as significant.

(35) 18. indicators of good writing (Carvalho, 2002; Cheng, 2005; Krause & O‘Brien, 1999; Thompson, 2001). An overt marking of writer‘s voice and individuality facilitates the writer‘s credibility, and appealing to the reader‘s views and emotions contributes to the construction of mutual bond (Crismore, et al., 1993). Hines‘ study (2004) clearly points out good-quality papers tend to have a higher degree of effective use of voice. For example, the personal voice of I enables the writer to show the relevance of the propositions to his personal opinions and attitudes, and we includes the reader as a member of a discourse community and as a friend, making the writer sound closer and. 政 治 大 English incorporates a good awareness of audience. By appealing to the reader‘s 立. intimate. On the other hand, Hyland (2001) posits that successful academic writing in. empathy, well-beings, concerns, and values, the writer attaches an interpersonal tone. ‧ 國. 學. to the text, and the overall quality can thus be improved (Hines, 2004).. ‧. It has been argued that self-expressive voice and audience-related strategies. sit. y. Nat. should be explicitly modeled and taught. As a consequence, many American. io. er. universities are currently teaching students to address the audience and to express their own voice in writing classroom in order to sound persuasive to the intended. al. n. v i n C&hAtkinson, 1999). U reader (Hines, 2004; Ramanathan Unfortunately, the two notions engchi are culture-bound, and they may not translate themselves automatically into L2. writing (Ramanathan, & Kaplan, 1996; Zainuddin & Moore‘s, 2003). Most EFL students, especially those from collectivistic cultures, do not usually write to express themselves but to become integrated into a scholarly community most of the time. They tend to say what they believe will not disturb the group or threaten the positive faces of their peers (Ramanathan & Atkinson, 1999). Given this, EFL students often find it difficult to create a new self—a confident, assertive and distinctive one. They do not know when to intrude their personal assertions during the interactive process (Duenas, 2007; Hyland, 2002b). Nor do they have a clear sense of audience and the.

(36) 19. way to recognize the reader‘s counter-positions (Cheng & Steffensen, 1996). For example, the majority of Hong Kong L2 students in Krause & O‘Brien‘s (1999) study failed to have a dialogic talk with the reader due to their false assumption of cultural commonality with the reader. In response to the problem, Ramanathan & Kaplan (1996) propose a discipline-oriented approach, arguing that if students are aware of the writing conventions that are unique in their chosen disciplines, they will be capable of expressing their voice and attending to the reader‘s needs more appropriately. Other. 政 治 大 al., 2008) also claim that a carefully designed and sequential instruction could 立. researchers (e.g. Berkenkotter, 1984; Hays, et al., 1988; Hyland, 2005a; Midgette et. 學. ‧ 國. sensitize learners to their own voice and the audience they are addressing, which would improve the overall quality of the essay writing.. ‧. Personal Pronouns. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Overview. i n U. v. As has been reviewed above, writer‘s voice and audience awareness can be both. Ch. engchi. overtly reflected in personal pronouns used in texts. Personal pronouns are defined as ―items used to refer to the speaker-writer (I), the addressee (you) and other person and objects whose references are presumed to be clear from the context (he, she, it, they)‖ (Hell, et al., 2005, p.242). They are central to face-to-face interaction, and able to help the writer state personal opinions, acknowledge claims, and guide the reader through the arguments (Harwood, 2007). Thompson and Thetela (1995, p.108) argue that personal pronouns are employed as ―projected roles‖ which function as the textual personae of the intended writer and reader. For example, the first and second person pronouns reflect how the reader is conceptualized by the writer and the degree of.

(37) 20. rapport the writer intends to establish with the reader (Kim, 2009). The implied social meanings of self-projection and reader-conception vary in accordance with the discourse contexts where they occur. Although there is evidence that personal pronouns in general are sparingly used in academic writing due to the dominant values of critical objectivity or scientific neutrality (Biber, et al., 1999), there is growing acknowledgement that personal pronouns play an important role in constructing the relations with the reader and the research community, especially in soft disciplines such as humanities and social. 政 治 大 intersection of the grammatical and pragmatic subsystems of language‖ (Rounds, 立. sciences (Breeze, 2007; Kuo, 1999). As a matter of fact, ―personal pronouns are at the. 1987, p. 14). Apart from their cohesive function in text discourse, personal pronouns. ‧ 國. 學. have multiple semantic references and are polypragmatic, especially in the. ‧. construction of interpersonal relationship (Fetzer & Bull, 2008; Lau, 2004; Rounds,. sit. y. Nat. 1987). When the writer seeks to represent himself, he is also defining the others in a. io. er. close or distant manner, and revealing the cultural and discourse community he belongs to. Implicit in this view is that personal pronouns embody the assumptions of. al. n. v i n C hother(s), the culturalUcontext, and discourse the writer made about himself, the engchi. community.. Pennycook (1994) makes the point that from discursive perspectives, all personal pronouns are ―political‖ in that they are strategically contrived to represent either the writer or the others. The choice of a specific personal pronoun reflects the writer‘s egocentricity or solidarity, sympathy or indifference, involvement or detachment in the discourse (Muhlhausler & Harre, 1990; Wales, 1996). In other words, personal pronouns can be used to indicate authority or rejection but also express modesty or acceptance, like the two sides of a coin. The selection of personal pronouns is not determined so much by grammatical concerns as by the.

(38) 21. sociolinguistic and pragmatic/rhetorical considerations. Approaches to Analyzing Personal Pronouns Personal pronouns have been examined from several approaches: (1) grammatical approach, (2) textual/endophoric approach, (3) deictic/discourse approach, and (4) pragmatic/sociolinguistic approach (Tian, 2001a; Wales, 1996). The grammatical approach is a linguistic one; for example, we refers to more than two first persons, and he names a third person singular. The textual approach identifies. 政 治 大 research views personal pronouns from deixis—a reference point whose interpretation 立 personal pronouns anaphorically and cataphorically for the textual cohesion. Other. is determined by the context of the utterance, i.e. time or space, for example, the first. ‧ 國. 學. person in self-reference, the second person in addressee-reference, and the third. ‧. person in other-reference. The pragmatic approach stems from interactional. sit. y. Nat. pragmatics and sees personal pronouns as interpersonal markers. A pragmatic use of. io. er. personal pronouns can convey the interactants‘ power, egocentricity, objectivity or solidarity, make generalizations, and realize other interpersonal functions.. al. n. v i n C hare typically referential Although personal pronouns and deictic—a canonical engchi U. and unmarked use, they may be non-referential or impersonal, where no specific. person is identified. Kitagawa & Lehrer (1990) assert that impersonal pronouns (e.g. you and we), often interchangeable with everyone or one, can be used to describe structural knowledge and universal events in everyday life. The shifts between referential and impersonal uses can be regarded as rhetorical or pragmatic strategies for fulfilling some specific communicative functions as the discourse flows. Currently, there are increasing interests in the pragmatic approach to personal pronouns. Research has attempted to explore the discourse functions performed by types of personal pronouns in various disciplines and genres, especially academic.

(39) 22. research papers and scientific writing (e.g. Fortanet, 2004; Hyland 2001a, 2001b; Inigo-Mora, 2004; Kuo, 1999; Luzon, 2009; Tang and John, 1999; Vassileva, 1998). For example, Hyland (2001b) points out that self-mention in research articles highlights the authors‘ contribution in a field. Kuo (1999) identifies some major discourse functions of we in scientific journals, such as explaining what is done, stating a goal, showing results, justifying a proposition, etc. Some studies (e.g. Biber, et al., 1999; Dafouz, et al., 2007, Flottum, et al., 2006, Harwood, 2005b) have further explored the discourse stance as expressed by personal. 政 治 大 cannot be studied alone; the co-text (co-occurring linguistic features) that 立. pronouns with their collocated linguistic forms. It is argued that personal pronouns. accompanies them have to be investigated simultaneously. Reilly, et al. (2005). ‧ 國. 學. contend that it is the constellation of forms, including the morphological, lexical,. ‧. syntactic, and discourse levels, that dynamically but subtly characterizes the writer‘. sit. y. Nat. stance. In addition to research on pragmatic use of English pronouns, other studies. io. er. (e.g. Kuo, 2002, 2003; Lin, 1993; Martinez, 2005) have compared personal pronouns in different languages in terms of frequency distribution and discourse functions.. n. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Pragmatic Functions of Personal Pronouns As mentioned earlier, personal pronouns are polyvalent and potentially fulfill a wide range of communicative functions. In the following, the various pragmatic meanings of different personal pronouns will be reviewed in depth: First Person Singular Pronoun I Self-mention pronoun I is the most common resource to represent authorial self and denote an ego. By placing himself in the deictic center, the writer can express his very subjective, personalized views and affective attitudes. He can also establish his credibility and confidence by including his personal experiences (Baumgarten &.

數據

相關文件

6 《中論·觀因緣品》,《佛藏要籍選刊》第 9 冊,上海古籍出版社 1994 年版,第 1

The aim of the competition is to offer students a platform to express creatively through writing poetry in English. It also provides schools with a channel to

We explicitly saw the dimensional reason for the occurrence of the magnetic catalysis on the basis of the scaling argument. However, the precise form of gap depends

Experiment a little with the Hello program. It will say that it has no clue what you mean by ouch. The exact wording of the error message is dependent on the compiler, but it might

To convert a string containing floating-point digits to its floating-point value, use the static parseDouble method of the Double class..

IPA’s hypothesis conditions had a conflict with Kano’s two-dimension quality theory; in this regard, the main purpose of this study is propose an analysis model that can

For obtaining the real information what the benefits of a KMS provides, this study evaluated the benefits of the Proposal Preparation Assistant (PPA) system in a KMS from a case

Therefore, this study intends to combine the discussion method with the interactive response system of Zuvio IRS for flipped teaching in the course "Introduction to