Grammar, construction and social action--- A study of the Qishi construction

全文

(2) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. methodological reliance on conversational participants’ displays that certain specific actions types are relevant at specific points in recognizably unfolding sequence types (Schegloff & Sacks 1973, cited in Ford et al. 2002). An investigation of naturally spoken data suggests that conversations are rich in constructions, i.e. symbolically complex schematic representations of recurrent grammatical patterns (Langacker 1987, Goldberg 1995, Bybee 1995, 1998, 2001, Bybee & Scheibman 1999, Taylor 2002, Tomasello 1992, 2000, 2003). Part of the job of interactional linguists is to uncover these grammatical patterns, their roles in social interactions and their positions in sequences. Grammatical knowledge, in this view, consists not only in knowing how to string words into grammatical constructions, but also in knowing how constructions are tied to specific types of social action and specific sequential contexts (Ono & Thompson 1995, Lerner 1996, Schegloff 1996, Couper-Kuhlen & Thompson 2000). It is thus the purpose of this study to investigate how a number of constructions are deployed by Mandarin conversation interactants to accomplish their social ends. Section 2 gives a brief sketch of how constructions are deployed to do social actions by Mandarin conversationists. Section 3 focuses on specifying the schematic representations and the social action formats for the qíshí construction. Section 4 is the conclusion.. 2. Constructions in Mandarin conversations Conversations are never planned in advance. For a conversation to proceed more or less smoothly, interlocutors have to cooperate with and understand each other at a number of different levels (cf. Clark 1996). To understand what her conversation interlocutor says, she needs not only to be equipped with the knowledge of syntactic structures, but to recognize grammaticized recurrent patterns, i.e. constructions, and their intended social actions. As pointed out by CA researchers (cf. Fetzer & Meierkord 2002), whenever social members interact by means of verbal communication, they gain experience about the use of language in a certain type of situation, and part of this experience will be stored as knowledge in their long-term memory (Bybee 1995, 1998, 2001, Bybee & Scheibman 1999, Taylor 2002, Tomasello 1992, 2000). The mental schemata that result constrain their expectations and verbal behavior whenever a similar situation is encountered in the future. Schemata have regulatory functions and are each associated with socially appropriate verbal behavior. It is now common knowledge that most constructions are lexically skewed and show frequency effects based on this skewing, which could not be discovered with constructed data. For instance, nǐxiàng (你像) “you like” and nǐshuō (你說) “you say”. 600.

(3) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. are frequently used by the speaker in the turn-initial position not to report an event, but to involve the co-participant in the construction of discourse (cf. Lin 1999). For example:1 (1) Xiangsheng 68 T: mhm=(0.8)其實因為我們每一檔的這個風格,_ qíshí yīnwèi wǒmen měi yìdǎng de zhège fēnggé,_ 69 ..都不太一樣 uh ,_ dōu bú tài yíyàng uh,_ 70 B: [對].\ [duì].\ 71 T: [有]時候,_ [yǒu]shíhòu,_ 72 ..你像..^蘇小倩的話,\ nǐxiàng..^ sūxiǎoqiàn dehuà,\ 73 ..就是一個 =,_ jiùshì yíge =,_ 74 ...(0.56) 那種=,_ nàzhǒng=,_ 75 ...(0.47)^三八三八的 ,_ ^ sānbā sānbā de,_ 76 ..所以她就--就做兒童嘛 .\ suǒyǐ tā jiù--jiù zuò értóng ma.\ T: “Mhm. In fact, since the style varies in each of our shows.” B: “Yes.” T: “Sometimes, take Suxiaoqian as an example. She is kind of silly and funny; therefore, she (often) plays the role of a child.” 1. Transcription is based on the Du Bois et al. (1993) system. Transcription notations used in this paper: [] speech overlap -truncated utterance : speaker identity . final intonation , continuing intonation \ falling pitch / rising pitch _ level pitch ^ primary accent …(N) long pause … medium pause .. short pause = lengthening (0) latching @ laughter <Q Q> quotation quality (Hx) exhalation <H H> inhalation. 601.

(4) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. (2) Xiangsheng 77 B: eh=,\ 78 T: 那=,\ nà=,\ 79 ...你說我跟^文賓的話,_ nǐshuō wǒ gēn^ wénbīn dehuà,_ 80 ..<F 通常...比較偏傳統一點 F> ,_ <F tōngcháng…bǐjiào piān chuántǒng yìdiǎn F>,_ 81 B: hm .\ 82 ..^非常傳統 .\ ^ fēicháng chuántǒng.\ 83 ..一^上臺就知道 ,\ yí ^ shàngtái jiù zhīdào,\ 84 ..你是從古時候走出來的 .\ nǐ shì cóng gǔshíhòu zǒu chūlái de.\ T: “Then, take me and Wenbin as an example. (Our styles are) usually... closer to the tradition,” B: “hm, (you are) very traditional. As soon as you are on stage, (the audience) immediately recognizes that you hail from the ancient tradition.” The referent coded by the 2nd personal pronoun in these two constructions functions not as the subject of the verb, but as a discourse-mobilizing dative. (cf. Luk Draye’s study on the German dative 1996:183-6, Rudzka-Ostyn on the Polish dative 1996:367ff, Lamiroy & Swiggers on the Polish dative 1993) The dative signals the speaker’s intention to motivate the addressee’s involvement in the dialogue. As pointed out by Langacker (1987) and Scheibman (2002), conversation participants normally remain ‘off-stage’, and when they are explicitly mentioned, i.e. put on the stage of the conversation events, there must be a reason for it. In the two excerpts above, the speaker is motivated by his desire to activate the addressee’s interest in the event reported, while at the same time signaling an intimacy or camaraderie between the speaker and the hearer. Take wǒshuō (我說) ‘I say’, which exhibits a very different function, as another example. The 1st personal pronoun in this construction is the subject of the verb ‘say’ <F F> fast speech <L L> <L2 L2> code switching <A A> <X X> uncertain hearing X <MRC MRC> each word distinct and emphasized (CAPITAL LETTERS) vocal noises. 602. low pitch allegro indecipherable syllable.

(5) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. and the clause following it is the speech act content. Lin (1999:139ff) identifies this construction as self-quotation and proposes that self-quoting has “an objectifying and distancing effect.” Our data show the speaker uses this construction to “go on record”, as an effort to take a stance either toward a specific issue or about some individual, as shown in the following excerpt: (3) Fire 309 F: ..不過,\ búguò,\ 310 ..我想呢,_ wǒxiǎng ne,_ 311 ..這個=,_ zhège=,_ 312 ...十五天的昏迷當中,_ shíwǔtiān de hūnmí dāngzhōng,_ 313 ..我想,_ wǒxiǎng,_ 314 ..你的家人那nǐ de jiārén nà315 ..那段時間一定很難熬喔.\ nàduàn shíjiān yídìng hěn nán’áo oh.\ 316 J: ...喔,\ oh,\ 317 ..對啊._ duìa._ 318 ..他們...<MRC 每=天 MRC>,_ tāmen…<MRC měi=tiān MRC>,_ 319 ..都是在醫院,\ dōushì zài yīyuàn,\ 320 ..在醫院外面等候.\ zài yīyuàn wàimiàn děnghòu.\ 321 F: ..uhhunh._ 322 ..所以我說,_ suǒyǐ wǒshuō,_ 323 ..你是=大難不死必有後福.\ nǐshì=dànàn bùsǐ bìyǒu hòufú.\ 324 ...就這樣.\ jiùzhèyàng.\. 603.

(6) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. F: “But, I think, during those 15 days when you were in a coma, your family must have gone through a very difficult time.” J: “Oh, yes. They kept waiting in the hospital everyday.” F: “So, I am saying, ‘you can expect the good days to come when you could escape unharmed in such a great calamity.’ ’’ (4) Seating 138 H: ...那=,_ na=,_ 139 ..你目前是從事什麼樣的工作呢._ nǐ mùqián shì cóngshì shémeyàng de gōngzuò ne._ 140 Y: ...(0.8)uN=,_ 141 ..公職.\ gōngzhí.\ 142 H: ...(0.7)haN=./ 143 Y: ...(0.6)公職.\ gōngzhí.\ 144 H: (0)哦公職.\ oh gōngzhí.\ 145 D: [哦公]職.\ [oh gōng]zhí.\ 146 H: [我]聽-,_ [wǒ] tīng-,_ 147 ...聽做是花花公子的公子.\ tīngzuò shì huāhuāgōngzi de gōngzi.\ 148 Y: [<@@@>] 149 H: ..我說還有這個行業啊.\ wǒshuō háiyǒu zhège hángyè a.\ 150 D: [那你現在-],_ [nà nǐ xiànzài-],_ H: “And what is your occupation now?” Y: “Gongzhi. (Public employment)” H: “HaN?” Y: “Gongzhi. (Public employment)” H: “Oh, public employment.” D: “Oh, public employment.” H: “I thought you meant ‘gongzi’ as in huahua-gongzi (playboy).” Y: “@@@.” H: “I was thinking, ‘how come there is still such an occupation now!’”. 604.

(7) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. Constructions often occur in specific social action formats. ‘我問(你)(一下)哦’ wǒwèn(nǐ)(yíxià)ho, as shown in (5), which is used by the conversational participant to do question framing. (5) Restaurant 411 L: .. 兩位好.\ liǎngwèi hǎo.\ 412 C2&C3: ..妳好.\ nǐhǎo.\ 413 L: .. 嗯我想請問一下 ho,_ mh wǒ xiǎng qiǎngwèn yíxià ho,_ 414 .. 就是說,_ jiùshìshuo,_ 415 ..妳們是不是常來=這家..下雨撐傘.\ nǐmen shìbúshì chánglái= zhèjiā.. xiàyǔchēngsǎn.\ L: “Good day.” C2 & C3: “Good day.” L: “mh. I would like to ask (you) a question; that is, ‘Do you often come to this (restaurant)…‘Xia-yu-cheng-san’?” The questions framed by such a construction are usually those that invite the hearer to be involved in an extended discussion or accounting of some state of affairs, rather than simple information exchange. Another functionally similar construction is wǒgēnnǐshuō/ jiǎng (我跟你說/講) ‘I tell you’. This construction often occurs in turn-initial position and frames the subsequent utterances, whose function is exactly like pre’s2 (cf. Schegloff 1980, 1990, 1996), into an extended discourse such as story-telling, as illustrated in (6): (6) KTV 241 B: .. (H)我跟你說<@ hoh @>,_ wǒgēnnǐshuō<@hoh@>,_ 242 ..我今天坐公wǒ jīntiān zuò gōng243 ...<@我今天坐計程車來(H)(H)(H),_ <@wǒ jīntiān zuò jìchéngchē lái (H)(H)(H),_ (11 IUs omitted). 2. We would like to thank Sandy Thompson for pointing this out for us.. 605.

(8) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. 255 B: ..對呀=,_ duì ya=,_ 256 ..因為前yīnwèi qián257 ..昨天就有兩個新聞都是 KTV.\ zuótiān jiù yǒu liǎngge xīnwén dōushì KTV.\ 258 A: (0)昨天啊.\ zuótiān a.\ 259 B: (0)對啊=就是有一個是=,_ duìa=jiùshì yǒu yíge shì=,_ 260 ...(0.84)好像有一個人要尋仇啊,_ hǎoxiàng yǒu yíge rén yào xúnchóu a,_ 261 ..然後就誤殺了兩個人.\ ránhòu jiù wùshā le liǎngge rén.\ B: “I tell you. Today I took a taxi here, because I waited for a long time but the bus did not come.” …. (11 IUs omitted) B: “Yeah, yeah, because yesterday there were two pieces of news related to KTV.” A: “Yesterday?” B: “Yeah. It was reported that one guy wanted revenge and then killed two innocent persons by mistake.” Another pattern is the búshì construction used to do questioning. Chang (1997) examines declarative questions, questions that have the form of a declarative and do not have any overt markers that identify them as questions, and shows that búshì “不是”, though commonly recognized as one of the negators and used to do negation (cf. Li & Thompson 1981, Ernst 1995, Lee & Pan 2001), is just as often used in conversation to formulate questions instead.3 The búshì construction is thus ambiguous when it is de-contextualized. A question that naturally arises is how recipients of declarative questions recognize them as questions. The answer is that interaction of morphosyntactic form and the sequential position within which a declarative question is embedded would lead to appropriate interpretations intended by conversational participants (see Huang 2000 and Weber 1993 for further discussions. Take (7) as an example:. 3. Heritage (2002) reports that in English news interviews negative interrogatives are sometimes used and treated unmistakably as “assertions”.. 606.

(9) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. (7) Schema 19 X: ..可是,_ kěshì,_ 20 ..沒找到.\ méi zhǎodào.\ 21 Y: ...(2.1)天哪,_ tiānna,_ 22 ..妳這樣花書錢,_ nǐ zhèyàng huā shūqián,_ 23 ..不是花很^多.\ búshì huā hěn^duō.\ 24 X: ...沒辦法啊,_ méibànfǎ a,_ 25 ..因為,_ yīnwèi,_ 26 ..我們學校,_ wǒmen xuéxiào,_ 27 ..我們又第一屆,_ wǒmen yòu dìyījiè,_ 28 ..它肯買多少書給我們看.\ tā kěn mǎi duōshǎoshū gěi wǒmen kàn.\ X: “But I couldn’t find one.” Y: “My god. Didn’t you have to spend a lot of money on books in this way?” X: “I had no other choices, because of our school (‘s policy). Besides, we are the first year students, how many books can it (the school) buy for us?” Line 23 has the syntactic form of a declarative, but the negative marker búshì is not used to negate the proposition of the utterance. Instead, it plays the role of a question indicator marking the declarative clause as doing questioning. Y at Line 23 is not saying that it is not the case that X did not spend a lot of money on books. Rather, Y is looking for confirmation that X in fact spent a lot on books. In this section, we have shown that constructions or schemas are pervasive in conversations and that speakers of natural languages have a large number of detailed expectations about how a particular routine sequence might run. As a result of such knowledge of a sequentially sensitive grammar as well as knowledge of a (partially) sequentially sensitive lexicon, language users are able to achieve a wide variety of communicative meaning with a relatively small set of morphosyntactic forms. In the following section we turn to an examination of the discourse-pragmatic functions of a disalignment schema, the qíshí construction.. 607.

(10) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. 3. The qíshí construction In the following sections, we shall specify both the sequential structure of the qíshí construction and how Mandarin conversation interactants deploy it to do various social actions. The present study of the qíshí construction is based on conversational data taken from NTU Corpus of Spoken Chinese. It is a moderate-sized corpus running to 13 hours and 51 minutes. The corpus was searched for utterances containing the word qíshí. A total of 229 tokens of qíshí were collected for the following analysis. Exploring the interactional functions of constructions has been a major focus of research in interactional linguistics and the undertaking of the present study has been inspired by recent scholarship in this area (Schegloff 1996, Bybee et al. 2002, Ford et al. 2002, Couper-Kuhlen et al. 2000, Tanaka 1999, among many references).. 3.1 The schematic representations of the qíshí construction The qíshí construction usually occurs in a three-part sequence, with the qíshí clause itself acting in the second part as a disalignment move against what is claimed in the first part. A statement is presented or implied in the first part, and the qíshí in the second part is used to signal disalignment and to make a counter claim, as in (8): (8) Huimei 167 A: 可是我們看到的你,_ kěshì wǒmen kàndào de nǐ,_ 168 ..都很開心,\ dōu hěn kāixīn,\ 169 ..@ 170 B: ..<X 其實不是 hoN X>.\ <X qíshí búshì hoN X>.\ 171 A: …unh.\ 172 B: ..uh=,_ 173 …(3)因為拍照,\ yīnwèi pāizhào,\ 174 ..<L 這是 L>平面喔,\ <L zhèshì L> píngmiàn oh,\ A: “However, whenever we see you in photos, you always look pretty upbeat..@.” B: “In fact, no.” A: “unh. “ B: “Because photos are just two-dimensional…”. 608.

(11) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. Speaker A, a radio program host, is interviewing B, a singer, talking about the difficulties of being a celebrity, who often refrains from revealing his/her true feelings. Whenever they faced the camera, they had to put on a façade, which was not true to themselves. At 170 B shows his disalignment, with a qíshí clause, against what was claimed by A at 167 and 168, “But whenever we see you, you look pretty upbeat.” Then at 173, B provides an account for his disalignment by using a yīnwèi clause (cf. Ford 1993, 2001a, 2001b). The qíshí construction can therefore be schematized as a three-part sequence as shown below: (9) The qíshí schema a. A: X: a statement about something or offers some assumed shared knowledge or belief b. B: Y: a disalignment with X’s statement (a qíshí clause) c. Z: post-expansion: provides an account for Y’s disalignment (yīnwèi or kěshì clause) In this schema, A makes a statement about something, or offers some assumed shared knowledge or belief. In the second move, B uses the qíshí construction to signal his/her disalignment with A’s move. When what is claimed is Speaker A’s own opinion or stance, the disalignment made against the X part is at the same time a disalignment with the interlocutor. In the course of a joint project (cf. Clark 1996: Chapter 7 & 8), to do a disalignment with one’s interlocutor is a face-threatening act, which is why such disalignment markers as pauses, hesitators, and hedges are often found accompanying the qíshí clauses in the corpus (cf. Excerpts 11 and 15). However, when the disalignment is made with a third-party’s statement, the qíshí clause may be seen as doing alignment with the interlocutor. That is why such alignment markers as duìa, búcuò, and yě are often found to occur with the qíshí clause (cf. Excerpt 10). The third part of the sequence is an optional expansion in which B offers his/her account for saying what s/he says in the second move. Whether a third explanatory move is justified depends largely on local contingencies in the interaction between A and B. When the qíshí clause is aimed at doing alignment, the Z part is usually not overtly expressed. In (10) below, M in fact aligns with H and prefaces her contribution with an alignment marker duìa ‘yeah’ and at the same time disaligns with H’s friend by using the qíshí construction.. 609.

(12) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. (10) Matchmaking 572 H: ..反正每次都差不多一樣.\ fǎnzhèng měicì dōu chābùduō yíyàng.\ (3 IUs omitted) 576 ...我每次都跟她說,_ wǒ měicì dōu gēn tā shuō,_ 577 eh 打麻將沒什麼關係啦.\ eh dǎ-májiàng méishéme guānxì la.\ 578 ..偶而啦 hoN.\ ǒu’ér la hoN.\ (22 IUs omitted) 596 ..偶而打,_ ǒu’ér dǎ,_ 597 ..沒有關係啦.\ méiyǒu guānxì la.\ 598 M: [對啊.\] [duìa.\] 599 ..其實,_ qíshí,_ 600 ..打麻將也不錯啊.\ dǎ-májiàng yě búcuò a.\ H: “Anyway, each time, she did the same thing….Each time I told her that it was alright to play mahjong sometimes…It was alright to play (it) occasionally.” M: “Exactly. In fact, playing mahjong is not bad.” However, if what the interactant intends to do is to disalign, it is much more common for him/her to add the post-expansion part as an explanatory device, as shown in (11):4 (11) Movie 298 T: ..<@ 我們常常覺得,_ <@ wǒmen chángcháng juéde,_ 299 ...(H)新電影就代表著=@>,_ (H) xīndiànyǐng jiù dàibiǎo zhe=@>,_ 300 ...<@好像是票房毒藥喔@>.\ <@hǎoxiàng shì piàofáng dúyào oh@>.\. 4. This excerpt will be discussed in detail in §3.2.1.2.. 610.

(13) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. (15 IUs omitted) ..究竟,\ jiūjìng,\ 317 ..uh=,_ 318 ...票房能不能反映,\ piàofáng néngbùnéng fǎnyìng,\ 319 ..我們一般人民,_ wǒmen yìbān rénmín,_ 320 ..對於所謂的台灣新電影跟新新電影,\ duìyú suǒwèi de táiwān xīndiànyǐng gēn xīnxīndiànyǐng,\ 321 ..他的支持的程度,\ tā de zhīchí de chéngdù,\ 322 ..或..參與的程度呢._ huò..cānyǔ de chéngdù ne._ 323 H: ...(0.88)uhm,_ 324 ...其實,\ qíshí,\ 325 ...(0.74)的確啦,\ díquè la,\ 326 ..這些電影在台灣,_ zhèxiē diànyǐng zài táiwān,_ 327 ..都=賣得=不是很[好].\ dōu=màide=búshì hěn[hǎo].\ (3 IUs omitted) 331 ..但是,\ dànshì,\ 332 ..uh=,_ 333 ..我不是怪=,\ wǒ búshì guài=,\ 334 ..我不是怪聽眾.\ wǒ búshì guài tīngzhòng.\ (7 IUs omitted) 342 ..(1.12) <TSK>觀眾啦,\ guānzhòng la,\ 343 T: ..@@ 344 H: ..有一點反制=的=現象.\ yǒu yìdiǎn fǎnzhì=de=xiànxiàng.\ 316. 611.

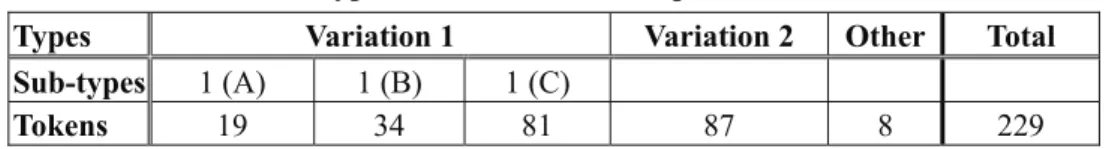

(14) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. T: “We always have the feeling that the new movies means poison for the box office….Does the box office actually reflect the degree to which ordinary people support or are committed to the Taiwan new and new-new movies?” H: “In fact, it is true that those movies do not sell well….I am not blaming the audience….In all fairness, …the audience…has an anti-cultural sentiment.”. 3.2 Variations on the qíshí schema Having illustrated the canonical schema of the qíshí construction, we shall in this and the following sections further specify a number of interesting variations on the basic format of the construction. From the corpus we extracted a total of 229 instances of the qíshí construction, which are classified into the following variations shown in Table 1: Table 1: Types of variations on the qíshí construction Types Sub-types Tokens. 1 (A) 19. Variation 1 1 (B) 34. 1 (C) 81. Variation 2. Other. Total. 87. 8. 229. These variations are classified in accordance with the social actions they perform: Variation 1 is very often used by the speakers to do either disalignment or alignment, while Variation 2 is used to do an A-event disclosure or confession. As to the ‘other’ type, a total of 8 instances were found in the corpus, and they are used by the speakers to create a light or humorous effect in the verbal interaction. In §3.2.1 we shall first specify the schematic representations for instantiations of Variation 1 and then demonstrate how they are deployed to do disalignment or alignment. In §3.2.2 Variation 2 will be illustrated. Section 3.2.3 will deal with the humorous usage of the qíshí construction. In §3.2.4 a brief summary of the various types of the qíshí construction will be given.. 3.2.1 Variation 1: disalignment and alignment Three subtypes of Variation 1 can be further distinguished as follows:. 612.

(15) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. (12) The schematic representations of Variation 1 Schema Variation 1(A) Speaker A: X Speaker B: Y (Z5). Variation 1(B) Speaker A: X Speaker B: Y Z. Variation 1 (C) Speaker A: (X) Y Z. Instantiation X: Claim Y: alignment maker + qíshí (Z). X: Claim Y: hedge, hesitator, pause + qíshí Z: yīnwèi/kěshì. X: Statement/description of other’s opinion (An assumed shared belief or knowledge) Y: qíshí (disalign with X) Z: yīnwèi/kěshì (elaboration/account). In (12) the X part is a statement, the Y part, i.e. the qíshí clause, signals a disalignment with what is claimed in the X part, and Z is a possible post-expansion, which in Variation 1(A), is often absent. When what is at issue is some claim attributed to a third party instead of to the interlocutor, the qíshí construction is frequently preceded by an alignment marker such as duìa “對啊” ‘Yeah’, or búcuò “不錯” ‘Exactly’.6 This is illustrated below. 3.2.1.1 Alignment: Variation 1(A) We use Excerpt (10), which is repeated below as (13), to demonstrate this usage. In Excerpt (13), H, a high school teacher in her mid-50s who often doubles as an amateur matchmaker, is telling M about one couple whose marriage was made possible through her matchmaking effort. The husband likes to play mahjong, which upsets the wife and leads her to complain to H about why she failed to forewarn her against his bad habit before the marriage. At the start of the excerpt, H says that it is alright to play mahjong sometimes; after all, everyone is entitled to some hobbies. At 598 M, H’s friend and colleague, concurs with an agreement marker duìa to show her alignment with H and then adds an assessment clause headed by qíshí. Here the qíshí construction signals an indirect disalignment with the stance taken by the wife in the reported event. 5. 6. Note that the dark shading means that this part is often absent, i.e. linguistically unrealized, from the conversation. Note that the presence of an alignment marker is not a criterial indicator indexing the speaker’s social action. As shown in Excerpt (14) below, the qíshí clause is used to do alignment even when it is not preceded by any alignment marker.. 613.

(16) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. (13) Matchmaking 572 H: ..反正每次都差不多一樣.\ fǎnzhèng měicì dōu chābùduō yíyàng.\ (3 IUs omitted) 576 ...我每次都跟她說,_ wǒ měicì dōu gēn tā shuō,_ 577 eh 打麻將沒什麼關係啦.\ eh dǎ-májiàng méishéme guānxì la.\ 578 ..偶而啦 hoN.\ ǒu’ér la hoN.\ (17 IUs omitted) 596 ..偶而打,_ ǒu’ér dǎ,_ 597 ..沒有關係啦.\ méiyǒu guānxì la.\ 598 M: [對啊.\] [duìa.\] 599 ..其實,_ qíshí,_ 600 ..打麻將也不錯啊.\ dǎ-májiàng yě búcuò a.\ H: “Anyway, each time, she did the same thing….Each time I told her that it was alright to play mahjong sometimes…It was alright to play (it) occasionally.” M: “Exactly. In fact, playing mahjong is not bad.” Doing alignment not only moves a conversation as a joint project forward, but also shapes the course in which the project is developed. Passage (14) is another illustration. (14) Kayun 60 A: [[@@]] 61 …結果這件事情,_ jiéguǒ zhèjiàn shìqíng,_ 62 …竟然還被老師說出來.\ jìngrán hái bèi lǎoshī shuō chūlái.\ 63 … <Q ha 你們要去做什麼 Q>._ <Q ha, nǐmen yào qù zuò shéme Q>._ 64 … <Q 矮靈祭是什麼啊 Q>.\ <Q ǎilíngjì shì shéme a Q>.\. 614.

(17) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. 65 66 67 68 69 70 A:. B:. … @ 結果全班都知道了.\ @ jiéguǒ quánbān dōu zhīdào le.\ …本來只是想偷偷去的.\ běnlái zhǐshì xiǎng tōutōu qù de.\ … (H) 對.\ (H) duì.\ B: …其實,\ qíshí,\ ..矮靈祭對賽夏族而言,\ ǎilíngjì duì sàixiàzú éryán,\ ..是非常重要的祭典.\ shì fēicháng zhòngyào de jìdiǎn.\ “@@ And it was unexpectedly disclosed by the teacher. ‘Ha, what did you go there for? What is ailingji?’ (he said). As a result, all the class knew about it. We had planned to go there secretly.” “In fact, for the Saisiyat people, ailingji is a very important religious rite.”. In the above excerpt, A and B, two female graduate students in linguistics, are talking about an important religious rite of the Saisiyat tribe in Northern Taiwan, the ailingji. A first says she had planned to go to the ailingji without being open about it, but then, unexpectedly, one of her professors asked in class “What do you go there for? What is the ailingji?” So this made her plan known to everyone in the class. At this point, B has a number of ways of continuing the conversation. She could have opted to make ailingji her topic, or the professor, or A’s trip. Here she chooses to continue the conversation with a qíshí statement, stating that “qíshí, ailingji is a very important religious rite for the Saisiyat people.” By using this statement, she implies that, “Even I, a student, knows that it is a very important religious rite, so how come the professor did not know it?” Furthermore, this qíshí statement signals both the speaker’s moral support to A’s plan (it is an important rite and it is absolutely correct of your plan to go) and her indirect, subtle comments on the professor. It is the professor’s open inquiry in the class that somehow disturbed A’s plan (no matter whether she did go eventually or not, it is not like what she originally planned); had the professor not asked those questions, Speaker A’s plan would not be disturbed. Here the social actions B is doing are multiple: she is making an indirect comment on the professor’s blatant lack of knowledge about the ailingji, and is redirecting the talk to the rite itself. By using the qíshí construction, she also expresses her alignment with her conversation partner.. 615.

(18) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. 3.2.1.2 Disalignment: Variations 1(B) and 1(C) As we have seen, the typical function of the qíshí construction is to do disalignment. The most common situations where participants are found to use it are: (a) in disaligning with what is claimed in the previous turn, as in (15); (b) in trying to answer a somewhat complicated question toward which the speaker has to take a stance, as in (16); and (c) in disaligning with commonly assumed belief, as in (17) and (18). Instances of (a) and (b) fall under Variation 1(B), while those of (c) Variation 1(C). The logic underlying such classification is that the X part of Variation 1(C) is assumed shared knowledge and is thus very often linguistically covert. In Excerpt (15) two teaching assistants in an English department are talking about how to manage the janitors in their department and do job assignments. First, Speaker M says she is going to write down specific job assignments for each janitor so that she can ‘find’ the person responsible for any job left unfinished. (15) Department 23 M: ...我這樣寫說,_ wǒ zhèyàng xiě shuō,_ 24 ..七樓燈管換新,_ qīlóu dēngguǎn huànxīn,_ 25 ..那就是誰負責.\ nà jiùshì shéi fùzé.\ 26 ...那這樣的話,_ nà zhèyàng dehuà,_ 27 ..就比較會去做了.\ jiù bǐjiào huì qù zuò le.\ 28 ...對啊,_ duìa,_ 29 ..因為,_ yīnwèi,_ 30 ..我現在是希望說,_ wǒ xiànzài shì xīwàng shuō,_ 31 ...把這些東西很^明確的寫下來,_ bǎ zhèxiē dōngxī hěn^ míngquè de xiěxiàlái,_ 32 ..把它印出來.\ bǎ tā yìnchūlái.\ 33 ...那這樣的話,_ nà zhèyàng dehuà,_. 616.

(19) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 M:. F: M: F:. ..誰要是沒做好,_ shéi yàoshì méi zuòhǎo,_ ..那我就說,_ nà wǒ jiùshuō,_ ..ei 是你要做的.\ ei shì nǐ yào zuòde.\ F: ..mm.\ M: ..我現在就是=想這個樣子啊.\ wǒ xiànzài jiùshì= xiǎng zhège yàngzi a.\ F: ...(0.9)其實,_ qíshí,_ ..有時候yǒu shíhòu..有時候對老林,_ yǒushíhòu duì lǎolín,_ ..對朱媽媽來講,_ duì zhūmāmā lái jiǎng,_ ..其實也=,_ qíshí yě=,_ ...(0.8)我覺得是不公平的事情.\ wǒ juédé shì bùgōngpíng de shìqíng.\ “I would write thus: ‘Someone or other is responsible for changing the light-bulbs of the 7th floor.’ This way, they (the janitors) will do their jobs much more actively (since each job is explicitly assigned to a certain person). Yes. Because I want to explicitly mark each assignment and have it printed out. This way, if anyone who does not do his assigned job, I could say, ‘Hey, that is what you have to do.’” “mm.” “That’s what I intend to do now.” “In fact, sometimes, sometimes for Old Lin, for Zhu Mama, I think this would be unfair.”. Note that M’s turn takes all of 14 IUs and yet F at 37 shows no intention to take over speakership. Speaker M repeats what she intends to do again at 38, and F’s next turn contribution begins with a long pause at 39, a repair at 41, a truncation at 43 and a long pause and a hedge at 44, showing F’s reluctance to disalign with her interactional partner. Another situation where the speaker uses the qíshí construction to do disalignment. 617.

(20) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. is seen in excerpt (11), repeated below as (16). Here speaker T raises a question about the status of new movies, a question embodying T’s implicit stance about the new movies. H’s response consists of a long pause, a pause filler followed by another long pause, elements which all index H’s reluctance to disalign with T. H’s disalignment at 324 begins with acknowledging some truth about the new movies, which in effect is an alignment with T’s prior observation, but in the end H’s disaligning stance is never made explicit. (16) Movie 298 T: ..<@ 我們常常覺得,_ <@ wǒmen chángcháng juéde,_ 299 ...(H)新電影就代表著=@>,_ (H) xīndiànyǐng jiù dàibiǎo zhe=@>,_ 300 ...<@好像是票房毒藥喔@>.\ <@hǎoxiàng shì piàofáng dúyào oh@>.\ (15 IUs omitted) 316 ..究竟,\ jiūjìng,\ 317 ..uh=,_ 318 ...票房能不能反映,\ piàofáng néngbùnéng fǎnyìng,\ 319 ..我們一般人民,_ wǒmen yìbān rénmín,_ 320 ..對於所謂的台灣新電影跟新新電影,\ duìyú suǒwèi de táiwān xīndiànyǐng gēn xīnxīndiànyǐng,\ 321 ..他的支持的程度,\ tā de zhīchí de chéngdù,\ 322 ..或..參與的程度呢._ huò..cānyǔ de chéngdù ne_ 323 H: ...(0.88)uhm,_ 324 ...其實,\ qíshí,\ ...(0.74)的確啦,\ 325 díquè la,\ 326 ..這些電影在台灣,zhèxiē diànyǐng zài táiwān,_ 327 ..都=賣得=不是很[好].\ dōu=màide=búshì hěn [hǎo].\. 618.

(21) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. (3 IUs omitted) ..但是,\ dànshì,\ 332 ..uh=,_ 333 ..我不是怪=,\ wǒ búshì guài=,\ 334 ..我不是怪聽眾.\ wǒ búshì guài tīngzhòng.\ 335 …我不是怪觀眾.\ wǒ búshì guài guānzhòng.\ (2 IUs omitted) 338 ..我摸著良心講,_ wǒ mōzhe liángxīn jiǎng,_ (3 IUs omitted) 342 ..(1.12) <TSK>觀眾啦,\ <TSK> guānzhòng la,\ 343 T: ..@@ 344 H: ..有一點反制=的=現象.\ yǒu yìdiǎn fǎnzhì=de=xiànxiàng.\ T: “We always have the feeling that the new movies mean poison for the box office….Does the box office actually reflect the degree to which ordinary people support or are committed to the Taiwan new and new-new movies?” H: “In fact, it is true that those movies do not sell well….I am not blaming the audience….In all fairness, …the audience…has an anti-cultural sentiment.” 331. As mentioned previously, when the X part is assumed shared knowledge, it may be linguistically covert, as in Excerpt (17), or overt, as in Excerpt (18). (17) Cosmetics 327 H: ...(1.1)你有什麼問題.\ nǐ yǒu shéme wèntí.\ 328 C2: ...(0.6) oh 我想請問一下,\ oh wǒ xiǎng qǐngwèn yíxià,\ 329 ..那個=,_ nàge=,_ 330 ...(0.8)黑斑啊,_ hēibān a,_. 619.

(22) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. 331. ..不知道要擦什麼,_ bùzhīdào yào cā shéme,_ (25 IUs omitted) 357 K: [哦=],_ [oh=],_ 358 ..所以是屬於比較妊娠斑 oN.\ suǒyǐ shì shǔyú bǐjiào rènchénbān oN.\ 359 ...(0.5)那黑斑的問題,_ nà hēibān de wèntí,_ 360 ..其實很簡單.\ qíshí hěn jiǎndān.\ 361 ..就是 hoN,_ jiùshì hoN,_ 362 ..你平常也是一樣,_ nǐ píngcháng yěshì yíyàng,_ 363 ..可以選擇含蜂膠成分的這個,_ kěyǐ xuǎnzé hán fēngjiāo chéngfèn de zhège,_ 364 ...(0.7) [再生]霜 hoN.\ [zàishēng]shuāng hoN.\ H: “What is your question?” C: “I’d like to know what one should apply when she has a dark-spot problem.” (25 IUs omitted) K: “Oh, that could be a problem caused by pregnancy spot. (0.5) As to the dark-spot problem, it is rather easy (to fix). You just choose the cream that contains the element of royal jelly, even in daily care.” This excerpt is taken from a radio call-in program where H is the program host, and K an invited dermatologist, who is there to answer incoming questions about the skin, and C2 is a caller-in asking about her skin problems. C2 first asks, “What should one apply when one has dark spots?” In the following 25 omitted IUs, K asks C2 a series of questions to get a better understanding about her problem. At Line 358, he concludes that her problem is caused by pregnancy. Then K goes back to C2’s initial question and states that, “The dark spot problem is in fact very easy to handle.” In the exchange prior to Line 359, no argument was made about the issue of the dark spot problem, nor did anyone take any specific stance toward this issue. The qíshí construction is used by the dermatologist here to disalign with the assumed shared knowledge that the dark spot problem is quite complex.. 620.

(23) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. In (18), L, a radio DJ, is interviewing R, a female singer and movie star, who often plays the character of feminine girls always with long straight hair in movies. In reality, R also wears long hair; L thus wonders whether R is really that kind of girl. At Line 183, Y disaligns with such a claim, saying she is not that kind of person. Here the assumed shared belief is overtly stated. (18) Show 175 Y: ... 有一個錯誤觀念就是,_ yǒu yíge cuòwù guānniàn jiùshì,_ 176 .. 妳長頭髮,_ nǐ cháng tóufǎ,_ 177 .. 你這個[樣子],_ nǐ zhège [yàngzi],_ 178 .. 你一定是(H)很女孩子,_ nǐ yídìng shì (H) hěn nǚháizi,_ 179 L: HuNHuN.\ 180 Y: .. 很柔,_ hěn róu,_ 181 .. 很柔弱,\ hěn róuruò,\ 182 .. 或者怎麼樣.\ huòzhě zěmeyàng.\ 183 .. 其實我不是.\ qíshí wǒ búshì.\ Y: “There is an incorrect notion that if one wears long hair, she must be a real girl, very feminine, or something like that. But in fact, I am not (that kind of person).”. In the following excerpt from a radio program, R, a local radio program DJ, is talking over the phone with her colleague L, another DJ on a business trip overseas. The interview with L has come to an end here and another DJ, Chén Xīlín, who is also R and L’s mutual friend, is ready to interview, signaling the beginning of a new discourse segment. It is an international phone call, and, most importantly, there is no part for L to play in the subsequent conversation. L is thus expected to hang up the phone and end the talk there. In 174 R is saying something, then she self-interrupts and abruptly tells L that she does not need to hang up the phone by using a qíshí clause. This qíshí clause is abrupt in that it is not related to any previous utterance in syntax, in semantics, or in pragmatics. The only plausible account to such a seemly abrupt act/utterance is that. 621.

(24) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. Speaker R has the assumed shared knowledge that when one plays no part in telephone conversation she should hang up the phone and end the conversation. Such an assumed knowledge is also shared by Speaker L, which is attested in her question in 177. (19) Reporter 1 (Rebecca) 152 R: 好啦,-\ hǎo la,\ 153 ..陳希林說,_ chénxīlín shuō,_ 154 ..叫我們跟你講話要短一些,_ jiào wǒmen gēn nǐ jiǎnghuà yào duǎn-yì-xiē,_ 155 ..因為他說他準備了差不多=,_ yīnwèi tā shuō tā zhǔnbèi le chābùduō=,_ (18 IUs omitted) 174 R: 我們應該讓他有多一點的時間來=,\ wǒmen yīnggāi ràng tā yǒu duōyìdiǎn de shíjiān lái=,\ 175 …妳其實可以不要掛斷,\ nǐ qíshí kěyǐ búyào guàduàn,\ 176 ..聽他怎麼講妳.\ tīng tā zěme jiǎng nǐ.\ 177 L: <A 因為 A>我要--我要掛斷嗎._ <A yīnwèi A> wǒ yào--wǒyào guàduàn ma._ 178 ..我不要掛斷.\ wǒ búyào guàduàn.\ R: “O.K. Chen Xilin said we had better cut it short here, because he is almost ready.”... “We should leave him more time to…In fact, you don’t need to hang up the phone. (You can) listen to what he says about you.” L: “Because I want...Should I hang up the phone? I don’t want to hang up.” In this subsection, we have demonstrated that certain specific actions types are relevant at specific points in recognizably unfolding sequence types (Schegloff & Sacks 1973, cited in Ford et al. 2002). We have also illustrated how the constructions are tied to specific types of social action in specific sequential contexts. In the next sub-section we shall demonstrate the social actions that Variation 2 is used to do.. 622.

(25) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. 3.2.2 Variation 2: A-event disclosure and confession The schematic representation of Variation 2 is as follows: (20) Variation 2 X: (Speaker A’s mental state is assumed by Speaker B) Y: qíshí clause (an A-event) In Variation 2, the qíshí clause very often appears as the first part of the sequence, since the X part is usually linguistically non-realized, which stands for Speaker B’s assumption about her addressee’s mental state or knowledge. The pattern in Variation 2 is used by the speaker to disclose an A-event; namely, a fact previously known only to the speaker herself. In this sense, the qíshí construction is not used to do simple ‘fact-telling’, but rather to do fact-disclosing.7 In other words, what the speaker does when she deploys the qíshí construction is “I know what is on your mind, I know that it is not true, and I will tell you what the truth is.” Since the X part is linguistically unrealized, the use of the qíshí construction sounds like a confession if it concerns the veracity of a claim about the speaker herself. Linguistically, Variation 1 looks quite similar to Variation 2. The differences between these two patterns lie in (1) the X part: in Variation 1 it is shared knowledge (by the community or, at least, by the conversation interlocutors), while in Variation 2, it is assumed by the speaker only (assumption about the addressee’s mental state or knowledge); (2) their social functions and the speaker’s intention: Variation 1 is used by the speaker to disalign with what is claimed or some assumed shared knowledge or belief in previous utterances, while Variation 2 is used to disclose an A-event or to do confession when the speaker believes that the addressee does not know what s/he is going to disclose. The typical social function of doing A-event disclosing in Variation 2 is illustrated in (21). (21) Reporter 1 (Rebecca) 473 C: 後來我就強忍著睡眠又出門了.\ hòulái wǒ jiù qiángrěnzhe shuìmián yòu chūmén le.\ 474 …那我當時去的地方呢,_ nà wǒ dāngshí qù de dìfāng ne,_. 7. The difference between telling a fact and disclosing a fact is that in doing the latter, the speaker has the pre-assumption that her addressee does not know the fact. We therefore identify this as an A-event disclosing.. 623.

(26) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. 475. …就是發生這個聯考舞弊案的[考場].\ jiùshì fāshēng zhège liánkǎo wǔbì’àn de [kǎochǎng].\ (5 IUs omitted) 481 C: 我就去找它主任,_ wǒ jiù qù zhǎo tā zhǔrèn,_ 482 …大概兩個聊了聊了聊.\ dàgài liǎngge liáoleliáole liáo.\ 483 R: …聊這個過程.\ liáo zhège guòchéng.\ 484 C: …聊這個過程.\ liáo zhège guòchéng.\ 485 …然後主任又跟我講說,_ ránhòu zhǔrèn yòu gēn wǒ shuō,_ 486 ..<Q 噯呀其實呀在另外一個地方 hoN 也有舞弊案 Q>.\ <Q ai-ya qíshí ya zài lìngwài yíge dìfāng hoN yěyǒu wǔbì’àn Q>.\ 487 ..也有舞--就說也有這個同樣一批人的舞弊案.\ yěyǒu wǔ--jiùshuō yěyǒu zhège tóngyàng yìpī-rén de wǔbì’àn.\ C: “I forced myself to stay awake and went out. The place I went to was the Examination Center where the scandal was reported to occur….I went to talk to the director. We talked, talked, talked.” R: “Talked about the consequence of the scandal.” C: “Talked about the consequence of the scandal. Then the director told me that, ‘Ai-ya, in fact, there is another scandal.’ Another scandal; in other words, another scandal done by the same group of people.” In (21) Speaker C is a reporter describing how he scooped the scandal at the government examination center. He went there and had an interview with the director of the Examination Center. During the interview, the director used the qíshí construction at Line 486 to disclose yet another scandal. If what is disclosed is an A-event about the speaker herself which she has kept secret for years, then what the speaker does with the qíshí construction is a confession, as further illustrated in (22): (22) Singer 2 95 B: ..不對的時候,_ búduì de shíhòu,_ 96 ..自己會很不好意思.\ zìjǐ huì hěn bùhǎoyìsi.\. 624.

(27) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. 97. ..但我一直到現在都還沒講,\ dàn wǒ yìzhí dào xiànzài dōu hái méi-jiǎng,\ 98 ..其實雲河有一段,\ qíshí yúnhé yǒu yíduàn,\ 99 ..有一個咬字,\ yǒu yíge yǎozì,\ (8 IUs omitted) 108 ..沒有捲舌,\ méiyǒu juǎnshé,\ 109 ..可是呢,_ kěshì ne,_ 110 ..可是劉家昌說,\ kěshì liújiāchāng shuō,\ 111 ..<Q 嗯這次錄得很好 Q>.\ <Q unh, zhècì lù-de-hěn-hǎo Q>.\ 112 ..那次我也不敢講,\ nàcì wǒ yě bùgǎn jiǎng,\ B: “When there was any error occurring, we would all feel very sorry. But there is something I had never told anyone about. In fact, in one of the stanzas in the song ‘Yúnhé’ (The Cloud River), I mis-pronounced one sound, which should have been a retroflex sound. But Liú Jiāchāng said, ‘Unh, very good.’ I dared not tell him this.” In (22) Speaker B, a famous singer invited to a radio interview, is talking about the experience of recording an album in the early stage of her singing career. She mentions that her supervisor was so strict and picky that every staff member, as well as the singer herself, was afraid of him. If there were ever the slightest error or even minor mis-articulation made, recording would have to start all over again. At Line 98 she used a qíshí construction to disclose a secret which she said at 97 she had kept for years. The excerpt below is another very interesting example in which there is no first move and the speaker J does the action of confession with the qíshí construction. (23) Fire 7 F: …(0.96)你的這個火災的經驗,\ nǐ de zhège huǒzāi de jīngyàn,\ 8 …是=[1 怎麼樣 1].\ shì=[1 zěmeyàng 1].\. 625.

(28) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 F: J: F: J:. J:. [1 這個喔.\ 1] [1 zhège oh.\1] …這個要講到三年前了.\ zhège yào jiǎngdào sānnián qián le.\ F: ..三年前發生的.\ sānnián qián fāshēng de.\ J: ..heNh.\ F: …m.\ J: … (1.06) 那一=,_ nà yí=,_ ..eNh=,_ …那一次 hoN,\ nà yí cì hoN,\ F: ..unheN,_ J : ..其實是我=,_ qíshí shì wǒ=,_ …可能是我自己不小心啦.\ kěnéngshì wǒ zìjǐ bùxiǎoxīn la.\ “How was your experience of that fire?” “Well, it was three years ago.” “It happened three years ago.” “HeNh.” F: “m.” J: “(1.06) Well, that time…in fact, it was I.. It probably was my carelessness that caused the fire.”. In (23), J is describing his own experience in a fire which was suspected to have been caused by someone’s careless handling of the gas heater, and a formal investigation by the police was undertaken. In other words, J was a victim but at the same time was the one who could have been charged with negligence for the accidental fire. Note that at Line 18 J first uses qíshí to start his talk, but then repairs and reformulates his description with the epistemic expression kěnéngshì (可能是) “probably”, which indexes the speaker’s awareness of the confession function of the qíshí construction.. 3.2.3 The humorous usage of the qíshí construction The examples of the qíshí construction that we have considered so far have had to do with doing alignment or disalignment with the conversation participant or doing confession. There are occasions, however, where the Mandarin speaker uses it to create a light and sometimes humorous effect. Such an effect is usually created by the. 626.

(29) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. incongruity between the typical functions associated with the qíshí construction and the content actually conveyed in it, as shown in (24): (24) Reporter 1 (Rebecca) 60 R: ..你們今天旅館很奇怪耶,_ nǐmen jīntiān lǚguǎn hěn qíguài ye,_ 61 ..一直<L2 busy L2>耶,_ yìzhí <L2 busy L2> ye,_ 62 ..是不是有什麼大人物住進去了.\ shìbúshì yǒu shéme dàrénwù zhù jìnqù le.\ (5 IUs omitted) 68 L: ..這個旅館每天都客滿.\ zhège lǚguǎn měitiān dōu kèmǎn.\ 69 ..好像.\ hǎoxiàng.\ 70 C: Ha= 71 R: (0)可能有很多kěnéng yǒu hěnduō72 C: (TSK) 這旅館很好.\ zhè lǚguǎn hěnhǎo.\ 73 R: 其實這個旅館[<@很便宜或很好@>].\ qíshí zhège lǚguǎn [<@hěn piányí huò hěnhǎo@>].\ 74 C: [@@@] 75 R: ..有兩種可能.\ yǒu liǎngzhǒng kěnéng.\ R: “The hotel you are staying is very strange today. (The line) has been busy all day. Are there big shots staying there?” … (5 IUs omitted)... L: “This hotel seems to be fully booked everyday.” C: “Ha-” R: “It could be-” C: “This hotel is quite good.” R: “In fact, (it might be that) this hotel is very cheap or very good. Two possibilities.” In (24), an excerpt of a live radio program, R and C, two local radio DJs, are talking over the phone with their co-worker, L, who is now on an overseas business trip and staying in a hotel. R first complains to L about the phone line in the hotel being busy all day and asks her whether there are big shots staying in the hotel. L replies that the hotel. 627.

(30) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. is full every day, implying that it is not any specific big shot but that it is too many people staying in this hotel that causes the line to be always busy. At Line 70, C is about to say something, but R takes over the turn to comment on the hotel. Not waiting for R’s turn to come to an end, C interrupts R’s turn by saying that “This hotel is terrific,” which sounds like an explanation for why the hotel is fully booked everyday. Here R and C seem to engage in a verbal competition: They both rush to see who will be the first in delivering his comments on the hotel. At Line 73, Speaker R says, “In fact, (it could be the case that either) the hotel is cheap or is terrific”. He deploys a qíshí construction seemingly to disalign with Speaker C. He seems to mean that “it could be either A or B; in other words, the situation is not as simple as you thought/described.” A closer scrutiny reveals, however, that although the statement that “the hotel is cheap” is possible in the objective world, it is incongruent with the shared knowledge they possess. In other words, part of the content conveyed in the qíshí construction is in fact known to parties to the conversation to be untrue or incongruent, contrary to the usual function of the qíshí construction. And it is this incongruity between the social function and semantic content that creates the humorous effect perceived by C at Line 74.. 3.3 Summary and conclusion The schematic representations of the various instantiations of the qíshí construction and their corresponding social action formats can thus be diagrammed as below: (25) The schema of the qíshí construction X: makes a claim Y: disaligns with X by using the qíshí clause Z: justifies by using the yīnwèi/kěshì clause. Variation 1 (A) X: claims Y: an alignment marker, e.g. duìa + qíshí (disaligns with X) (Z). Variation 1 (B) X: claims Y: hedge, pause, or hesitator + qíshí (disaligns with X) Z: accounts by using the yīnwèi/kěshì clause. Corresponding Social Action Formats To do alignment or To do disalignment disalignment. 628. Variation 1 (C) (X: statement of assumed shared belief or knowledge) Y: qíshí (disaligns with X) Z: yīnwèi/kěshì. Variation 2 X: assumed addressee’s mental state (usu. not realized linguistically) Y: discloses an A-event by using the qíshí clause. Humorous usage X: makes a claim Y: gives an obviously known fact by using the qíshí construction. To do disalignment. To do A-event disclosing or confession. To create humorous effect.

(31) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. As shown in Schema (25), the qíshí is an interactionally motivated construction: It is used to disalign with what is claimed or assumed in the prior turn and is usually produced in the second part of a three-part sequence. The qíshí in Variation 1(A), but not in 1(B) or 1(C), is quite often preceded by an agreement marker, showing speaker B’s intention to do alignment with speaker A, or less frequently, with some third party. Note that the justification, the third part of the sequence, namely a yīnwèi or kěshì clause, normally occurs in Variation 1(B) and 1(C), but not in 1(A), since disalignment is usually a dispreferred move which needs justification or explanation. When speaker B is about to do disalignment with the other party, as in Variation 1(B), his/her turn is often prefaced by an obvious pause, hesitator, or hedge. In Variation 2, the qíshí clause usually occurs in the turn-initial position. As our data reveal, however, the clause is interpretable as a second move in social interaction: First some assumed belief of A’s is made relevant to the ongoing interaction and then B is prompted to do confession in order to address A’s belief. Finally, the social action formats of the qíshí construction can clearly be seen to be part of the competence of Mandarin speakers, since parties to conversation perform actions with their turns oriented towards the action sequence, as demonstrated by the incongruity and thus the humorous effect, perceived by the speaker C at Line 74 in (24). The wide heterogeneity of the qíshí construction as instantiated in the corpus attests to the rich and complex social actions that each can be deployed to perform. Analyses of naturally spoken data reveal that grammar is an inventory of grammaticized recurrent patterns, i.e. constructions, emerging from the crucible of social interaction. Grammatical knowledge resides not only in the knowledge of syntactic structure, but also in the knowledge of how each construction is intended to carry out what social action. By examining how conversation interactants are mutually attuned to various constructions to accomplish intended social actions, we can get a better picture of the socially shared nature of grammatical knowledge (cf. Schegloff 1991).. 629.

(32) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. References Bybee, J. 1995. Regular morphology and the lexicon. Language and Cognitive Processes 10.5:425-455. Bybee, J. 1998. The emergent lexicon. CLS 34:421-435. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society. Bybee, J. 2001. Phonology and Language Use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Bybee, J. 2003. Mechanisms of change in grammaticization: the role of frequency. Handbook of Historical Linguistics, ed. by B. Joseph and R. Janda, 602-623. Malden: Blackwell. Bybee, J., and P. Hopper. (eds.) 2001. Frequency and the Emergence of Linguistic Structure. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Bybee, J., and J. Scheibman. 1999. The effect of usage on degrees of constituency: the reduction of don’t in English. Linguistics 37.4:575-596. Chang, Chung-yin. 1997. A Discourse Analysis of Questions in Mandarin Conversation. Taipei: National Taiwan University MA thesis. Clark, H. H. 1996. Using Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Couper-Kuhlen, E., and Sandra A. Thompson. 2000. Concessive patterns in conversation. Cause, Condition, Concession, Contrast: Cognitive and Discourse Perspective, ed. by E. Couper-Kuhlen and B. Kortmann, 381-410. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Draye, Luk. 1996. The German dative. The Dative, Vol. 1: Descriptive Studies, ed. by William van Belle and Willy van Langendonck, 155-216. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Du Bois, John W., Stephan Schuetze-Coburn, Susanna Cumming, and Danae Paolino. 1993. Outline of discourse transcription. Talking Data: Transcription and Coding in Discourse Research, ed. by Jane A. Edwards and Martin D. Lampert, 45-89. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Ernst, Thomas. 1995. Negation in Mandarin. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 13:665-707. Ford, Cecilia E. 1993. Grammar in Interaction: Adverbial Clauses in American English Conversations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ford, Cecilia E. 2001a. Denial and the construction of conversational turns. Complex Sentences in Grammar and Discourse, ed. by J. Bybee and Michael Noonan, 61-78. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Ford, Cecilia E. 2001b. At the intersection of turn and sequence: negation and what comes next. Studies in Interactional Linguistics, ed. by Margret Selting and E. Couper-Kuhlen, 51-79. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Ford, Cecilia E., Barbara A. Fox, and Sandra A. Thompson. 2002. The Language of. 630.

(33) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. Turn and Sequence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Goffman, E. 1976. Replies and responses. Language in Society 5.3:257-313. Goldberg, Adele E. 2003. Constructions: a new theoretical approach to language. TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences 7.5:219-224. Heritage, J. 2002. The limits of questioning: negative interrogatives and hostile question content. Journal of Pragmatics 34.10-11:1427-1446. Huang, Shuanfan. 2000. The story of heads and tails─on a sequentially sensitive lexicon. Language and Linguistics 1.2:79-107. Lamiroy, B., and P. Swiggers. 1993. Patterns of mobilization: a study of interaction signals in Romance. Conceptualizations and Mental Processing in Language, ed. by R. A. Geiger and B. Rudzka-Ostyn, 649-678. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Langacker, Ronald W. 1987. Foundations of Cognitive Grammar, Vol. 1. Stanford: Stanford University Press. Lee, Peppine Po-Lu, and Haihua Pan. 2001. The Chinese negation marker bu and its association with focus. Linguistics 39.4:703-731. Lerner, Gene H., and T. Takagi. 1999. On the place of linguistic resources in the organization of talk-in-interaction. Journal of Pragmatics 31.1:49-75. Li, Charles, and Sandra A. Thompson. 1981. Mandarin Chinese: A Functional Reference Grammar. Berkeley: University of California Press. Lin, Hsueh-o. 1999. Reported Speech in Mandarin Conversational Discourse. Taipei: National Taiwan Normal University dissertation. Meierkord, Christiane. 2002. Recurrent sequences and mental processes. Rethinking Sequentiality: Linguistics Meets Conversational Interaction, ed. by Anita Fetzer and Christiane Meierkord, 99-119. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Ono, Tsuyoshi, and Sandra A. Thompson. 1995. What can conversation tell us about syntax? Alternative Linguistics: Descriptive and Theoretical Models, ed. by P. Davis, 213-271. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Ostyn, Rudzka. 1996. The Polish dative. The Dative, Vol. 1: Descriptive Studies, ed. by William van Belle and Willy van Langendonck, 341-394. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Pomerantz, Anita. 1984. Agreeing and disagreeing with assessments: some features of preferred/dispreferred turn shapes. Structures of Social Action, ed. by J. Atkinson, J. Maxwell, and J. Heritage, 152-163. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Pomerantz, Anita. 1990. Mental concepts in the analysis of social action. Research on Language and Social Action 24:299-310. Schank, R. C., and R. P. Abelson. 1977. Scripts, Plans, Goals, and Understanding: An Inquiry into Human Knowledge Structures. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.. 631.

(34) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1980. Preliminaries to preliminaries: ‘Can I ask you a question?’. Sociological Inquiry 50.3-4:104-152. Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1990. On the organization of sequences as a source of ‘coherence’ in talk-in-interaction. Conversational Organization and Its Development, ed. by B. Dorval, 51-77. Norwood: Ablex. Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1991. Conversation analysis and socially share cognition. Perspectives on Socially Shared Cognition, ed. by Lauren B. Resnick, John M. Levine, and S. D. Teasley, 150-171. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1996a. Issues of relevance for discourse analysis: contingency in action, interaction and co-participant context. Computational and Conversational Discourse: Burning Issues, an Interdisciplinary Account, ed. by E. Hovy and D. Scott, 3-35. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1996b. Turn organization. Interaction and Grammar, ed. by E. Ochs, E. Schegloff, and Sandra A. Thompson, 52-133. New York: Cambridge University Press. Schegloff, Emanuel A., and H. Sacks. 1973. Opening up closings. Semiotica 8.4:289-327. Scheibman, Joanne. 2002. Point of View and Grammar: Structural Patterns of Subjectivity in American English Conversation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Tanaka, Hiroko. 1999. Turn-taking in Japanese Talk-in-interaction: A Study in Grammar and Interaction. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Taylor, John R. 2002. Cognitive Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Tomasello, M. 1992. First Verbs: A Case Study in Early Grammatical Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Tomasello, M. 1998. Introduction: the cognitive-functional perspective on language structure. The New Psychology of Language: Cognitive and Functional Approaches to Languages Structure, ed. by M. Tomasello, 1-25. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Tomasello, M. 2000. Do young children have adult syntactic competence? Cognition 74.3:209-253. Tomasello, M. 2003. Introduction: some surprises for psychologists. The New Psychology of Language: Cognitive and Functional Approaches to Languages Structure, Vol. 2, ed. by M. Tomasello, 1-14. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Weber, E. 1993. Varieties of Questions in English Conversation. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Wu, Ruey-Jiuan Regina. 2004. Stance in Talk: A Conversation Analysis of Mandarin Final Particles. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.. 632.

(35) Grammar, Construction, and Social Action: A Study of the Qíshí Construction. [Received 30 March 2005; revised 1 September 2005; accepted 6 September 2005] Fuhui Hsieh Graduate Institute of Linguistics National Taiwan University 1, Sec. 4, Roosevelt Road Taipei 106, Taiwan hsiehfh@ms64.hinet.net Shuanfan Huang sfhuang@ntu.edu.tw. 633.

(36) Fuhui Hsieh and Shuanfan Huang. 語法、結構及社會行動:「其實」結構的研究 謝富惠. 黃宣範. 國立台灣大學. 近年來,會話分析研究者及互動語言學者的研究顯示,在分析言談時應 該加入社會行動及互動的因素考量,以便能使言談分析有更進一步的發展。 在本篇論文中,我們探討社會行動在結構佈局以及語法呈現中所扮演的角 色。仔細研究日常言談語料,可知日常會話中充滿了結構;所謂結構也就是 「符號學上複雜、其表徵具有基模形式,而且一再重複出現的語法句式」 。結 構經常出現在特定的社會行動格式。本文中我們專注於探討「其實」結構及 其社會行動格式。這個「其實」結構經常出現在帶有三個步驟的結構系列中 的第二個步驟,而且經常被用來作以下的社會行動:(1) 不認同聽者對方或第 三方的立場或論述,有時是表認同;(2) A-事件的揭露、或招認告解;(3) 製 造幽默效果。藉由探究會話參與者如何使用不同的結構來達到社會行動目 的,我們可以更加了解語法結構如何經由社會互動的各種行動中浮現。 關鍵詞:結構,語法,社會互動,社會行動,「其實」. 634.

(37)

數據

相關文件

We would like to point out that unlike the pure potential case considered in [RW19], here, in order to guarantee the bulk decay of ˜u, we also need the boundary decay of ∇u due to

• One technique for determining empirical formulas in the laboratory is combustion analysis, commonly used for compounds containing principally carbon and

• helps teachers collect learning evidence to provide timely feedback & refine teaching strategies.. AaL • engages students in reflecting on & monitoring their progress

Robinson Crusoe is an Englishman from the 1) t_______ of York in the seventeenth century, the youngest son of a merchant of German origin. This trip is financially successful,

fostering independent application of reading strategies Strategy 7: Provide opportunities for students to track, reflect on, and share their learning progress (destination). •

Strategy 3: Offer descriptive feedback during the learning process (enabling strategy). Where the

How does drama help to develop English language skills.. In Forms 2-6, students develop their self-expression by participating in a wide range of activities

By correcting for the speed of individual test takers, it is possible to reveal systematic differences between the items in a test, which were modeled by item discrimination and