漢語兒童請求時的禮貌 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) MANDARIN-SPEAKING CHILDREN’S. POLITENESS IN REQUESTS. 立. 政 治 BY 大. Nat. n. al. Graduate Institute of Linguistics. er. io. sit. A Dissertation Submitted to the. y. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Yupin Chen. i n U. v. In Partial Fulfillment of the. Ch. engchi. Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics. July 2010.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(4) . 立. 政 治 大 . ‧ 國. 學. . ‧. . y. Nat. . n. . Ch. . e n g c h i . Copyright 2010 Yupin Chen All Rights Reserved. er. io. al. sit. . i n U. v.

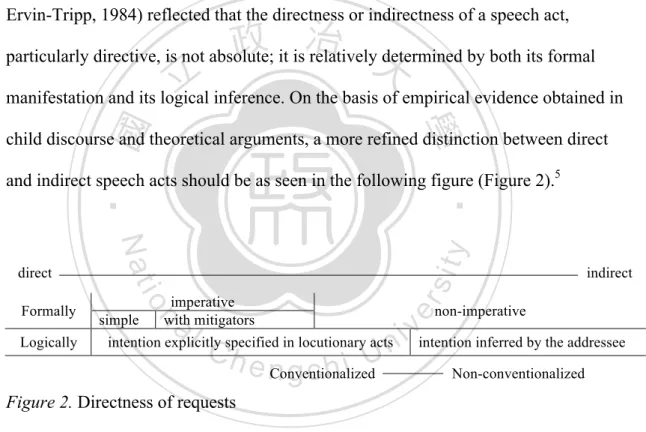

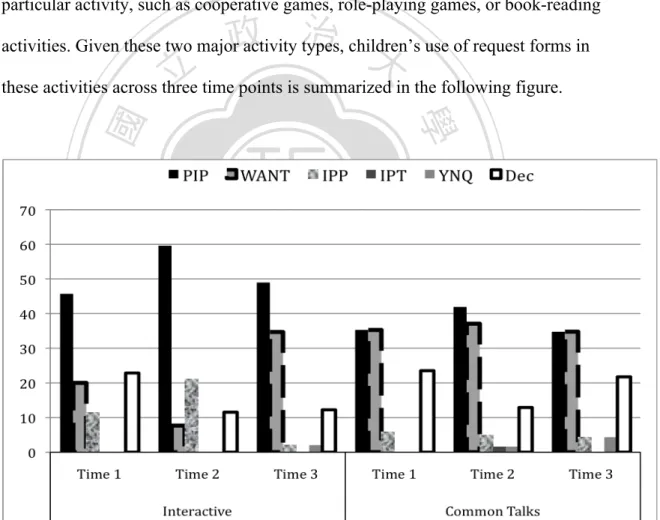

(5) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………...iv Table of Contents …………………………………………………………………..vii. 政 治 大. List of Tables ………………………………………………………………………ix. 立. List of Figures ……………………………………………………………………...xi. ‧ 國. 學. Chinese Abstract …………………………………………………………………...xiii English Abstract ……………………………………………………………………xvii. ‧. Chapter 1 Introduction ………..…………………………………………………….1. y. Nat. Chapter 2 Literature Review ………………………………...……………………..7. sit. 2.1 Politeness ………………………………….……………………………9. n. al. er. io. 2.1.1 Politeness theories …………………….……………….……..9. i n U. v. 2.1.2 Children’s politeness ……………….…………………….….23. Ch. engchi. 2.2 Requests as a Speech Act …………..……………………………….…28 2.2.1 Requests and/or directives …………….………..…………....30 2.2.2 Children’s requests ……………….………….……………....32 2.2.3 Directness of request forms ………..………………………...39 2.3 The Present Study …………………………..…….…………………....49 Chapter 3 Methodology ………………………...………….………………….…...55 3.1 Subjects ……………………………………..………………………….57 3.2 Data ………………..……………………..…………………………….59 3.3 Data Analysis ………………………...…………..…………………….60 3.3.1 Cases of requests …..………………..………..………………61. . vii .

(6) 3.3.2 Cases of politeness ……………………...……..……………...66 3.4 The Coding System ……………………………………………………..69 Chapter 4 Findings ……………………………..…………………………………..81 4.1 Children’s Requests ………………………………..…………………...82 4.1.1 Children’s various request forms ………………………..……83 4.1.2 Request forms and contexts …………………………………..92 4.1.3 Request repertoire across ages ………………………..……..103 4.2 Children’s Politeness in Requests ………………………..……………107 4.2.1 Children’s use of social deixis ………………………..……..107 4.2.2 Directness of request forms and politeness ..………..……….129. 政 治 大. 4.3 Persuasive Tactics ………………………….…………….……………150. 立. 4.4 Effectiveness ……………………………….………………….………153. ‧ 國. 學. 4.5 Summary ………..……………………………..………………………175 Chapter 5 …………………………………………………………………...……...179. ‧. 5.1 Discussion ………………………………………………………...…...180. y. Nat. 5.2 Conclusion ………………………………………………...…………..191. sit. 5.3 Suggestions for Further Studies ……………………………………….193. n. al. er. io. References……………………………………...……………………………..……199. i n U. v. Appendix A ……………………………………………………...………………...209. Ch. engchi. Appendix B ……………………………………………………………...………...211 Appendix C …………………………………………………………...…………...213. . viii .

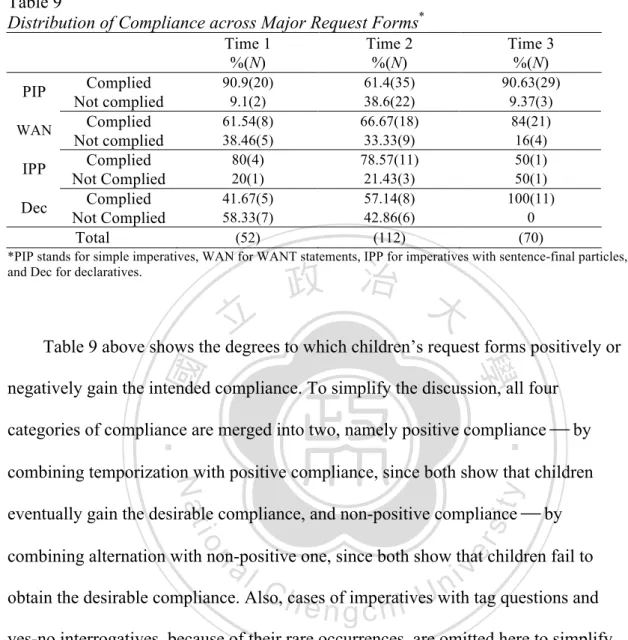

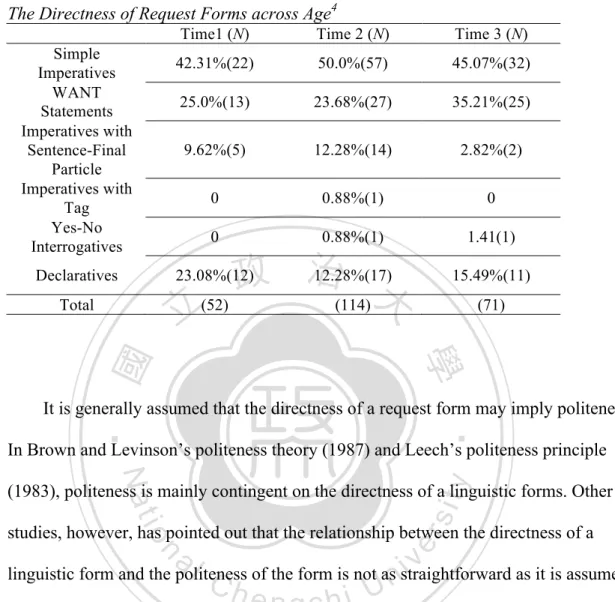

(7) List of Tables. 立. 政 治 大. Table 1. Frequencies of Children’s Request Forms …………………………………84. ‧ 國. 學. Table 2. Distributions of Request Forms within Contexts across Time in Percentage ………………………………………………………………………………………..94. ‧. Table 3 Frequencies of Social Deixis ………………………………………………108. y. Nat. Table 4. The Directness of Request Forms across Age …………………………….131. io. sit. Table 5. The Directness of Request Forms with Respect to Status across Age ……133. er. Table 6. Distributions of Directness of Request Forms Regarding Cost across Age ………………………………………………………………………………………144. al. n. v i n Table 7. Distribution of ToneC ofh Speech with Regard e n g c h i Uto Status across Time ……...147 Table 8. Distribution of Tone of Speech Regarding Cost across Age ……………..149. Table 9. Distribution of Compliance across Major Request Forms …………….... 154 Table 10. Effectiveness of Request Forms with Respect to Status ……………….. 160 Table 11. Effectiveness of Request Forms Regarding Cost ………………………. 163 Table 12. Effectiveness of Different Tone of Speech across Age ………………….172. . ix .

(8) List of Figures. 立. 政 治 大. Figure 1. Possible strategies for doing FTAs ………………………………………16. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 2. Directness of requests ……………………………………………………43 Figure 3. Children’s uses of reqeust forms in two major activities in percentage …97. ‧. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. . Ch. engchi. xi . i n U. v.

(9) 國立政治大學研究所博士論文提要 研究所別「語言學研究所 論文名稱「漢語兒童請求時的禮貌 指導教授「黃瓊之博士 研究生「陳郁彬. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 論文提要內容「�共一冊︽分五章 . ‧. 本研究主要探討台灣漢語兒童在日常家庭對話中︽對父母行. sit. y. Nat. 使請求時的語言表現及禮貌現象︽以了解漢語兒童的語用發展歷. n. al. er. io. 程與現象〈研究的重點主要是在兒童表達請求的言語行為時所使. i n U. v. 用的語言形式︽以及人際關係中會影響兒童禮貌表現的因素及其. Ch. engchi. 反應在語言形式的使用情形〈透過對兩位以漢語為母語的兒童長 期互動的觀察︽本研究發現︽兒童在表達請求時︽採用多元的語 言形式︽包含祈使句︾直述句︾帶有語尾助詞的祈使句︾以及表 達個人慾望或需求的陳述句〈考量這些語言形式使用的情境後進 一步發現︽兒童傾向在一般的日常對話中多以表達個人慾望的陳 述句為表達請求的主要語言形式︽而在合作互動的情境中︽主要 的請求語言形式則絕大多數為祈使句﹀這樣的語言功能分工︽在 兩歲半左右可以明顯觀察得到〈 . xiii .

(10) 另外︽透過兒童語言形式表達禮貌的觀察顯示︽兒童普遍會 依照人際互動的一些因素來選擇表達請求時所適用的語言形式︽ 尤以有效性及地位高低為主要的兩個考量因素〈觀察中發現︽兒 童大量使用祈使句及表達個人慾望需求的陳述句來表達請求︽而 其他的語言型式相對上則少得許多︽主要的因素很有可能是這兩. 政 治 大. 類的語言型式︽在他們與父母互動中最能有效達到他們的溝通目. 立. 的〈此外︽兒童也會依照他們在表達請求時與他們父母間的地位. ‧ 國. 學. 高低來考量請求所要使用的語言形式〈儘管觀察結果指出︽兒童. ‧. 傾向使用能有效達到溝通互動目的的語言形式來表達他們的請. sit. y. Nat. 求︽必要時︽他們也會依照互動雙方的地位關係進行語言形式的. n. al. er. io. 微調︽這樣的語言表現有明顯的系統性﹀而這樣的系統性︽進而. i n U. v. 突顯了兒童約略在三歲前即對禮貌在語言形式使用的影響有了初 步的系統與了解〈. Ch. engchi. 除了句法結構外︽兒童也會透過詞彙單位來傳達他們在請求 所應注意的禮貌︽例如︽必要時︽他們會使用�幫︾�請︾ 及�我們來修飾或削弱請求時可能對對方所造成的影響〈這些 詞彙的使用在發展上屬於略晚才習得的語言形式〈 最後︽研究的結果也指出︽雖然兒童表達請求時︽使用較為 間接而有禮的語言形式︽未必較能有效地達到他們的溝通目的︽ . xiv .

(11) 但是如果在表達請求的同時︽也進一步說明理由者︽達到溝通目 的的機率則有明顯的增加〈另外︽從語言形式和表達請求的情境 及人際地位的互動中發現︽兒童表達請求的基本語言形式極有可 能為表達個人的慾望與需求的陳述句︽儘管祈使句在所觀察的語 料中使用的頻率最高〈這樣的論點︽不但符合其他文獻中針對兒. 政 治 大. 童語言發展的發現︽也貼近兒童語言發展為連續過程的觀點︽且. 立. 也反應了人類語言發展的基本歷程〈. ‧ 國. ‧. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. . 學. . . Ch. engchi. xv . i n U. v.

(12) Abstract. This study aims to investigate Mandarin-speaking children’s requests and their linguistic politeness so as to contribute to the understanding of children’s pragmatic development as well as linguistic development. The present study is mainly. 政 治 大 spontaneous interactions with their parents and what interpersonal factors may have 立 concerned with what linguistic devices children utilize to issue requests in. ‧ 國. 學. an influence on children’s uses of request forms. These two issues were discussed. through examinations over children’s spontaneous interactions with their parents in. ‧. family settings.. Nat. sit. y. On the basis of the longitudinal data produced by two children, it has been. n. al. er. io. found that when requesting, children draw upon various linguistic devices, primarily. i n U. v. including simple imperatives, WANT statements, imperatives with sentence-final. Ch. engchi. particle, and declaratives. Such a variety of request forms can be observed from an early age on, at around two years old, but demonstrates no remarkable development, judged simply by these formal devices used at different ages. When situational contexts are also taken into account, nevertheless, a developmental pattern regarding the request forms is thus revealed. In terms of situational contexts, children are found to use simple imperatives primarily to convey their requests when involved in interactive activities with their parents, whereas they tend to utilize both simple imperatives and WANT statements when having common talks with their parents.. . xvii .

(13) Such a division of labor can be noticeably observed when children are about two and half years old. As to children’s linguistic politeness when making requests, the results reveal that children are aware of the influence of certain interactional and interpersonal factors on the appropriate use of linguistic forms. Children are inclined to draw upon comparatively more effective forms to issue their requests, and therefore children by. 治 政 大 since these two and large request with pure imperatives and WANT statements, 立. request forms may effectively obtain the desirable compliance from their parents. In. ‧ 國. 學. addition to effectiveness, children may also take interpersonal status and request cost. ‧. into consideration when judging which request forms to use in the immediate context.. y. Nat. Such consideration of interpersonal status when determining the appropriate request. n. al. er. io. three.. sit. forms to use may thus reflects children’s awareness of politeness at around the age of. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. In addition to syntactic structures, children are also found to draw upon lexical items to show their deference to politeness. Children may use such lexical forms as qing ‘please’, bang ‘to help with’ and women ‘let’s; we’ to mitigate the illocutionary force in their requests. These forms, despite their low frequencies in the data, may thus reveal children’s sensitivity to politeness when making such a face-threatening act as requests. The use of these polite lexical forms also discloses a comparatively late development in linguistic politeness; children may not use such polite forms until they reach the second half of their second year. A late development is also observed in the respect of children’s use of reasons to justify their requests. The results show . xviii .

(14) that children’s justification may generally increase the effectiveness of their requests, but such use is infrequent and only observed at a later age, around the age of three. Finally, the results of the investigation into the data may suggest that WANT statements are highly likely an earlier developed request form and the prime linguistic forms children rely on to issue their requests, given the findings that children tend to request with WANT statements when interacting with parents at a lower status as a. 治 政 大 to the effect of interpersonal child and that children’s use of request forms are prone 立 status. Such a suggestion may not only conform to the findings in previous studies. ‧ 國. 學. with regard to children’s linguistic development in requests, but also accord with the. ‧. general developmental pattern of human languages.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. . Ch. engchi. xix . i n U. v.

(15) Chapter 1. 立. 治 INTRODUCTION 政 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. Children were born to be social animals. Ever since children were born, they. y. Nat. sit. have been exposed to an interactional environment and endowed with the basic need. n. al. er. io. to interact with people in all sorts of social or interpersonal situations (Tomasello,. i n U. v. 1992). To become a capable and competent language user who is able to use language. Ch. engchi. appropriately in social situations, it is indispensible for children to develop their pragmatic ability, in addition to the acquisition of linguistic competence, including phonology, morphology, syntax and semantics. They are required not only to learn the fact that ‘[l]anguage is social behavior’ (Tomasello, 1992, p. 67), but also to develop the ability to convey their communicative intents clearly and appropriately (Ninio & Snow, 1996); in particular, children are called upon to develop the appropriate and well-received ways to issue speech acts or control acts (Ervin-Tripp et al., 1990). Among all speech acts, requests or directives have been well documented and extensively explored by researchers in various disciplines, including sociologists, 1.

(16) 2. psychologists, anthropologist, educators, and linguists. The major issues concerning researchers in this respect include the structure of children’s requests (e.g. Ervin-Tripp, 1977; Ervin-Tripp, 1980; Gordon & Ervin-Tripp, 1984), the directness and indirectness of children’s requests (e.g. Garton & Pratt, 1990), children’ production and comprehension of requests (e.g. Leonard, 1993; Babelot & Marcos, 1999), and children’s strategies of requests (e.g. Wood & Gardner, 1980; Axia, 1996). It is generally agreed among these studies that children’s requests are an. 政 治 大. early-developed communicative ability. Even in prelinguistic stage, children have. 立. already been able to demonstrate their communicative intents with gestures,. ‧ 國. 學. sometimes accompanied with vocatives (Bates et al., 1975; Bates, 1967; Bruner, 1981; 1983; Kelly, 2007). In addition, researchers mostly emphasize that children’s. ‧. development of requests also reveals children’s awareness of socio-interactional. y. Nat. sit. knowledge: context, shared knowledge, politeness, and social relation and status. n. al. er. io. between interlocutors (e.g. Garvey, 1974; Ervin-Tripp, 1977, Wood & Gardner, 1980;. i n U. v. Gordon & Ervin-Tripp, 1984; Ervin-Tripp et al., 1990; Babelot & Marcos, 1999; Chen, 2006).. Ch. engchi. Correlated with requests, politeness is also alluded to by studies on children’s requests. Most studies attribute children’s various strategies to politeness. They point out that children’s utilization of various request strategies may result from their awareness of politeness. In some studies, politeness is even the main focus of investigation. It is pointed out that requests tend to be subject to some socio-interactional factors, and these factors may spur children’s adjustment of linguistic devices drawn upon to issue requests. Such adjustment of linguistic forms can therefore reflect children’s linguistic politeness and thus politeness may be the.

(17) 3. integral factor in the performance of requests (Gordon & Ervin-Tripp, 1984; Ervin-Tripp et al., 1990). Focusing on children’s development or use of politeness, most studies are mainly concerned with developmental stages of children’s politeness. They take pains in exploring how children express or become aware of politeness at a particular age (e.g. Wood & Garnder, 1980; Axia & Baroni, 1985; Axia, 1996). The findings in this respect so far are divergent; some studies suggest a late development (e.g. Axia & Baroni, 1985; Axia, 1996), while others reveal an early systematic use of. 政 治 大. politeness, e.g. Ervin-Tripp et al. (1990). Axia (1999) argues that children’s. 立. development of politeness embarks from five years old on and matures at school age. ‧ 國. 學. around eight years old. However, Ervin-Tripp and her colleagues (Ervin-Tripp et al., 1990) analyzed politeness into three aspects, including social indices, social tactics,. ‧. and persuasion. They found that children at different ages tend to systematically,. y. Nat. sit. though varying across ages, exploit these three aspects of politeness.. n. al. er. io. The above findings and arguments pertaining to either request or politeness,. i n U. v. however, are mostly based on observations and examinations on English-speaking. Ch. engchi. children or children from the western cultures. It seems that studies on Mandarin-speaking children’s directives or requests have long lagged behind. Despite the fact that some studies have proposed an overall discussion of children’s pragmatic development (e.g. Hsu, 1996 & 2000; Zhou, 2002), there remains a lack of systematic analyses of children’s ability of directives or requests, including their request repertoire (linguistic forms or devices utilized by children to issue requests), request strategies, and their social awareness and politeness reflected in their requests or directives. In addition, although politeness has been found to be influential in children’s requests, Mandarin-speaking children’s development or ability in.

(18) 4. performing politeness, nevertheless, has remained underexplored. Children’s politeness in their preschool years is especially neglected, although a few studies has been concerned with school-age children’s politeness, e.g. Hsiao (1999). The present study, therefore, aims to examine Mandarin-speaking children’s repertoire of requests, including strategies, formal variations, and systematic distributions of the formal variations. In addition, since the performance of requests may reflect children’s social and interpersonal knowledge, this study also considers children’s development in this. 政 治 大. respect by observing and examining their politeness when they are making requests.. 立. Two major issues are in question: (a) Mandarin-speaking children’s repertoire of. ‧ 國. 學. requests, including how children convey their requests, what formal variations are utilized by children to encode their requests, and whether systematic distributions of. ‧. the formal variations can be observed and generalized in children’s spontaneous. y. Nat. sit. speech, and (b) Mandarin-speaking preschoolers’ politeness in requests, including. n. al. er. io. their linguistic enactment of politeness, age differences in the development of. i n U. v. politeness, interactional or interpersonal factors that may influence children’s. Ch. engchi. performance of requests, and the relationships between politeness and compliance; that is, whether being politeness is correlatively effective in making requests. The dissertation is structured as follows. Chapter 2 is mainly literature review. In this chapter, a review on speech acts theory and politeness theory is presented. In addition, studies on child language in the respects of requests or directives and politeness are also reviewed. Based on the review, research questions of the present study will be proposed. Chapter 3 introduces subjects and data to be observed in the present study. Moreover, given the findings and suggestions in the literature, Chapter 3 also explicates how the data are managed and analyzed. Above all, in Chapter 3, a.

(19) 5. coding system created to manage the data is presented in detail. Chapter 4 presents the findings and analysis. Chapter 5 discusses the relations between the findings in this study and those in the literature and points out the implications of this study and concludes the entire study. Last but not least, the final chapter, namely Chapter 5, also indicates limitations of this present study and suggests the potential issues or directions for future studies.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. i n U. v.

(20) Chapter 2. 立. 政 治 大. LITERATURE REVIEW. ‧ 國. 學 ‧. This study attempts to explore Mandarin-speaking children’s requests to their mothers and their linguistic enactment of politeness in requests. In such a study on. y. Nat. io. sit. politeness, crucial concepts or theories of politeness should not be neglected.. er. Therefore, a part of the review deals with the major politeness theories, including. al. n. v i n Lackoff’s (1973; 1975), Leech’s C h(1983), and BrownUand Levinson’s (1987). Although engchi these politeness theories are well established, they may not be directly applicable to child politeness. The application of these theories to child discourse is yet to be mature. Further studies concerning such application are desirable. As the following review will show, many studies on child politeness focus on the linguistic enactment of politeness in interactions. They are concerned with what linguistic devices children utilize to encode their politeness in a particular situation at a particular stage of pragmatic development. These studies are based on the belief that politeness is conveyed via a certain degree of formal modification made to linguistic. 7.

(21) 8. forms. Among them, the framework proposed by Ervin-Tripp and her colleagues (1990) seems convenient for studies on child politeness development. Their framework integrates issues discussed in the theories of politeness as well as studies on child language. Also, the framework is constructed on the basis of observations on children’s politeness in daily conversation. Therefore, a part of the review discusses studies on child politeness, and the framework in Ervin-Tripp et al.’s study is the major focus.. 政 治 大. In addition, a number of studies on child politeness investigate children’s speech. 立. acts to understand their development of linguistic politeness, requests in particular.. ‧ 國. 學. Researchers by and large agree that requests with the inherent face-threatening. ‧. property play a prefect role in the exploration of politeness. Given the property that requests involve one’s desire to be fulfilled by asking the other, whenever one. y. Nat. io. sit. performs such a speech act, s/he places a certain degree of threat on both parties.. n. al. er. Modifications on linguistic forms of requests can reduce or avoid such threat, which. Ch. i n U. v. in turn is believed connected with politeness. In order to elucidate the relationship. engchi. between requests and politeness in child language, this study thus examines requests, following most of the previous studies. Hence, theories of speech acts and studies on child requests are also included in the review. As an outline, this chapter consists of two main subparts. The first part reviews the theoretical proposals of politeness and children’s politeness in their conversations with adults and peers. The second part presents the review of studies concerning requests as a speech act as well as requests in child language use. The last part of the chapter presents the research scope and research questions of this study..

(22) 9. 2.1 Politeness One crucial respect in children’s pragmatic development is to acquire appropriateness of language use. An integral part of appropriate use of language is politeness, particularly in performance of speech acts in interaction. When requesting, for instance, a requester most of the time prefers a compliance to his/her requests. For the compliance to be met, the requester thus needs to perform the request intents appropriately. The requester should pay attention to all potential factors that may. 治 政 influence the appropriateness and effectiveness of the 大request. Among these factors 立 lies politeness. Although politeness may not be the sole determinant factor of the ‧ 國. 學. success of a speech act, it is indeed indispensible. Therefore, for children to. ‧. appropriately and successfully perform a speech act, they are required to acquire politeness in the course of their linguistic development.. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. 2.1.1 Politeness theories. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Although politeness is significant and essential in daily conversation and interaction, not until late 1970s did linguists pay serious attention to the significance of politeness in pragmatics (Kasper, 1990; 1996). Thereafter, politeness has become the main issue concerning many linguists studying pragmatics. Among all the studies concerning politeness, the politeness theories proposed by Lakoff (1973, 1975), Leech (1983), and Brown & Levinson (1987) seem to be the most well-received and provocative ones. Lakoff (1973) adopted Grice’s (1975) Cooperative Principle to account for.

(23) 10. politeness. Lakoff’s politeness theory consists of two main rules: (a) be clear and (b) be polite. Underlying these two rules are three sub-rules or sub-maxims, including (1) don’t impose; (2) give options; and (3) make the hearer feel good. By the rules and sub-rules cited above, it can thus be infer that for Lakoff politeness seems to be a device to avoid offense and displeasure. Despite the maxims, Lakoff did not specify how the degree of politeness should be assessed by the speaker and the hearer in interaction; how the interlocutors should compute with respect to each maxim so as to. 政 治 大. know which maxims to follow at a particular situation.. 立. Leech (1983) also proposed his politeness theory on the basis of Cooperative. ‧ 國. 學. Principle (Grice, 1975). In Leech’s framework, politeness or Politeness Principle (PP. ‧. for short) is considered as a component of Interpersonal Rhetoric (hereafter IR). The other two components of IR, according to Leech, are Grice’s Cooperative Principle. y. Nat. io. sit. (CP, henceforth) and Irony Principle. These three principles are equally important in. n. al. er. Leech’s pragmatic theory. In Leech’s opinion, Grice’s CP regulates how people. Ch. i n U. v. should convey their messages when interacting with one another and how the. engchi. addressee of an utterance should do so as to infer the implicature of the utterance when addressed in an indirect way. In Leech’s opinion, CP, however, fails to explain why people often convey their messages indirectly when they can do so in a direct way. Therefore, in order to redeem CP’s disadvantages, Leech emphasized that PP is a necessary complement to CP. For Leech (1983), PP and CP are complementary to each other. CP and PP, however, do not work completely in isolation. They do not operate individually in an orderly fashion or as alternatives to each other. According to Leech, CP and PP.

(24) 11. interact and they are in a ‘trade-off’ relation (Leech, 1983, p. 82). Basically, PP has a higher status over CP. PP enables interlocutors to maintain ‘social equilibrium and the friendly relations (Leech, 1983, p. 82)’. Nevertheless, CP can win over PP in certain situations. For example, when interlocutors are involved in a highly cooperative activity or discourse, where they may be asked to cooperatively finish a task at hand within a time limit, CP plays the main role instead of PP. Hence, Leech argued that when interacting, interlocutors always face a tension of ‘a clash between the CP and. 政 治 大. the PP so that they have to choose how far to “trade off” one against the other (Leech,. 立. 1983, p. 83)’ in a particular situation.. ‧ 國. 學. Following Grice’s framework, Leech (1983) accounted for politeness with a set. ‧. of maxims and sub-maxims as Lakoff (1973) did. Leech’s PP consists of six maxims and each maxim contains two sub-maxims which form a pair. The maxims are as. y. Nat. n. er. io. al. sit. follows (Leech, 1983, p. 132):. Ch. i n U. v. (I) TACT MAXIM (in impositives and commissives). engchi. (a) Minimize cost to other [(b) Maximize benefit to other]1 (II) GENEROSITY MAXIM (in impositives and commissives) (a) Minimize benefit to self [(b) Maximize cost to self] (III) APPROBATION MAXIM (in expressives and asserttives) (a) Minimize dispraise of other [(b) Maximize praise of other] (IV) MODESTY MAXIM (in expressives and assertives) (a) Minimize praise of self [(b) Maximize dispraise of self] (V) AGREEMENT MAXIM (in assertives) (a) Minimize disagreement between self and other [(b) Maximize agreement between self and other] 1. The square brackets belong to the original text..

(25) 12. (VI) SYMPATHY MAXIM (in assertives) (a) Minimize antipathy between self and other [(b) Maximize sympathy between self and other]. It is clear in the above citation that in Leech’s view politeness seems determined and maneuvered with respect to a set of scales. The set of scales, according to Leech (1983, pp. 123-127), comprises: (a) The Cost-Benefit Scale: refers to the cost or. 政 治 大 refers to the amount of choice which the speaker gives to the hearer when performing 立 benefit of a speech act to the speaker or the addressee; (b) The Optionality Scale:. a speech act; (3) The Indirectness Scale: refers to the effort that the hearer should. ‧ 國. 學. make to infer the intended illocutionary act; (4) The Authority Scale: refers to the. ‧. relative power that the speaker has over the addressee; and (5) The Social Distance. sit. y. Nat. Scale: refers to how familiar the speaker is with the addressee (See also Fraser, 1990,. io. er. p. 226). Hence, when performing a speech act, the speaker may do it in a more direct way as the speaker’s authority is greater over the hearer or the hearer’s cost with. n. al. regard to the speech act is little.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Leech (1983, p. 83) also highlighted a distinction between ‘ABSOLUTE POLITENESS’. and ‘RELATIVE POLITENESS’. ‘ABSOLUTE POLITENESS’ refers to the. degree of politeness that is inherently associated with an illocutionary act. For example, directives, such as orders and commands, are impolite by nature, while commissives, such as offers and invitations, are polite by nature. ‘ABSOLUTE POLITENESS’. is evaluated by the set of scales that has been discussed above. The set. of scales has a positive and negative pole. When the speaker maximizes the inherent politeness of an illocutionary act, ‘positive politeness’ is being performed, and when.

(26) 13. the speaker minimizes the inherent impoliteness of an illocutionary act, ‘negative politeness’ is being performed. The set of scales that has been reviewed above, according to Leech, basically deals with the ‘ABSOLUTE POLITENESS’. On the other hand, ‘RELATIVE POLITENESS’ refers to the degree of politeness that may be shifted with respect to the context or situation, culture, or language community in which a particular illocutionary act is performed. In terms of ‘ABSOLUTE POLITENESS’, such utterances as Tell me what you see in the map is. 政 治 大. inherently more impolite than those as Would you mind telling me what you see in the. 立. map, but there may be situations in which the latter instead appears to be less polite. ‧ 國. 學. than the former, e.g., when both parties of the dyad are involved in a cooperative task. ‧. with a time limit. Therefore, despite the fact that a particular illocutionary act may. Nat. io. sit. relative situations where an illocutionary act is carried out.. y. have inherent ‘ABSOLUTE POLITENESS’, the actual degree of politeness varies with the. n. al. er. Apparently, Leech’s (1983) PP seems to be a very refined proposal and able to. Ch. i n U. v. accommodate actual language use. It is, however, not immune from criticism. As. engchi. pointed out by Fraser (1990), Leech’s PP seems too complicated for interlocutors to assess and compute. When the speaker is making a speech act, it appears difficult for the speaker to know what maxims s/he should apply, what pragmatic scale is immediately relevant, how the speaker should formulate the maxims and scales, and so on. In addition, it is also pointed out by other researchers that Leech’s framework also implies that the number of maxims and scales that are required to explain politeness may not be limited; there may be an infinite number of maxims and scales, as many as it needs to account for a particular situation involving politeness. It seems.

(27) 14. that new maxims or sub-maxims can always be added to Leech’s PP (Brown & Levinson, 1987; Dillons et al., 1985; Fraser, 1990; Lavandera, 1988; Reiter, 2000; Turner, 1996). The politeness theory proposed by Brown and Levinson (1987) seems probably to be the best received and known among all recent theories or accounts of politeness. Brown and Levinson (1987, p.61) based their politeness theory on the notion of ‘face’, or ‘the public self-image’, posited by Goffman (1967). They stated that:. 立. 政 治 大. face is something that is emotionally invested, and that can be. ‧ 國. 學. lost, maintained, or enhanced, and must be constantly attended to in interaction. In general, people cooperate (and assume. ‧. each other’s cooperation) in maintaining face in interaction,. such cooperation being based on the mutual vulnerability of. Nat. n. sit er. io. al. y. face (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p.61).. v. Brown and Levinson (1987, p. 62) further divided face into two categories on the. Ch. engchi. i n U. basis of interlocutor’s desires or wants. One is ‘negative face: the want of every “competent adult member” that his actions be unimpeded by others’, and the other is ‘positive face: the want of every member that his wants be desirable to at least some others.’ To put it simply, the former pertains to the reduction of imposition on the addressee or both interlocutors in interaction, and the latter pertains to our ‘desire to be ratified, understood, approved of, liked or admired (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p. 62).’ Based on these two aspects of face, Brown and Levinson (1987) organized their politeness theory and accounted for politeness with the idea that certain speech acts.

(28) 15. are intrinsically threatening to ‘the face wants of the addressee and/or of the speaker. They thus dubbed speech acts of this sort as ‘face-threatening acts (or FTAs)’ (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p. 65). According to Brown and Levinson, for example, orders, requests, advice, warnings, and threats are basically threatening to the addressee’s negative face. Speech acts, such as disapproval, criticism, challenges, and interruption are threatening to the addressee’s positive face. On the other hand, a speech act can also be threatening to the speaker’s negative or positive face. As pointed out by. 政 治 大. Brown and Levinson, such acts as thanking, accepting one’s apology and accepting. 立. one’s offers are threatening to the speaker’s negative face, and apologizing,. ‧ 國. 學. confessing, and accepting compliments are threatening to the speaker’s positive face.. ‧. In order to avoid or at least to mitigate the force of an FTA, language users may thus exploit politeness. From politeness, language users in turn develop a set of linguistic. y. Nat. io. sit. devices or linguistic strategies. By using these linguistic devices or strategies,. n. al. er. according to Brown and Levinson, language users can not only successfully get their. Ch. i n U. v. message across but also conform to politeness without (unintentionally) threatening anyone’s face.. engchi. A primary part of Brown and Levinson’s (1987) politeness theory is to utilize linguistic strategies to minimize the potential threats underlying an FTA. Brown and Levinson claimed that interlocutors should attend to the potential face risk to each other in interaction and use appropriate linguistic strategies to avoid the imposition on interlocutors’ negative face and/or positive face. The implementation of FTAs is schematized as follows by Brown and Levinson:.

(29) 16. without redressive action, baldly positive politeness. on record Do the FTA. with redressive action negative politeness. off record Don’t do the FTA. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. Figure 1. Possible strategies for doing FTAs (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p. 69). ‧. As shown in Figure 1, when performing an FTA, according to Brown and Levinson,. y. Nat. io. sit. one can choose to do the FTA ‘on record’ or ‘off record’ (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p.. n. al. er. 69). By performing the FTA ‘on record’, one clearly and unambiguously conveys the. Ch. i n U. v. intended act for the addressee to do. In other words, performing an FTA ‘on record’. engchi. means to explicitly encode the communicative intention in the utterance and the addressee of the FTA needs not infer to deduce the intended act. Brown and Levinson further argued that when performing an FTA one can further do so with or without ‘redress’ (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p. 69). Performing an FTA without redress means to convey one’s communicative intent straightforwardly via clear, unambiguous, concise linguistic forms, such as, “Don’t stop!” Such FTAs without redress can be utilized, according to Brown and Levinson, only when both parties of the interaction agree on the suspension of face demand..

(30) 17. In other cases, an FTA can be performed on record as well as with redress. Such ‘redressive action’ (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p. 69) shows that one puts into consideration potential damage to face and attempts to eschew the damage. Redressive FTAs can be achieved through modifications or addition of linguistic forms. FTAs of this sort can involve ‘positive politeness’ and ‘negative politeness’ (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p. 70). Positive politeness is oriented to the positive face of the addressee; that is, what the speaker wants agrees with what the addressee wants.. 政 治 大. Negative politeness, in contrast, is oriented to the addressee’s negative face; in other. 立. words, the speaker assures that what s/he wants does not interfere with what the. ‧ 國. 學. addressee wants. The avoidance of interference can be achieved via ‘conventionalized. ‧. indirectness, for whatever the indirect mechanism used to do an FTA’ (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p. 70). The indirect mechanism can be exemplified with such indirect. y. Nat. io. sit. requests as Can you pass the salt (questioning the addressee’s ability to do an act or. n. al. er. the preparatory condition of a request) and Would you mind closing the window. Ch. i n U. v. (questioning the addressee’s desire or the sincerity condition of a request).. engchi. In addition, an FTA can also be performed ‘off record’ (Brown & Levinson, 1987, p.69). Doing an FTA off record means to convey one’s communicative intention ambiguously with more than one potential candidate for the intended meaning. Attaining the intended meaning of an off-record FTA requires the addressee to make some efforts. Examples are like hints. The speaker can hint to the addressee and ask him/her to perform the intended act through metaphor, irony, or rhetorical questions (e.g., Is there any juice left?). Performing an FTA off record thus, according to Brown and Levinson, leaves the intended meaning of the FTA negotiable to some.

(31) 18. extent. In addition, Brown and Levinson also suggested that off-record FTAs can become on-record ones once they are conventionalized between interlocutors or even in a speech community. In addition to the possible strategies for doing FTAs, Brown and Levinson (1987) proposed three factors that they claim to influence the seriousness of an FTA. They argued that people, perhaps of all cultures, assess the imposition or intrusiveness of an FTA according to the following factors:. 立. 政 治 大. (i) the ‘social distance’ (D) of S and H (a symmetric relation). ‧ 國. 學. (ii) the relative ‘power’ (P) of S and H (an asymmetric relation) (iii) the absolute ranking (R) of impositions in the particular culture (Brown. ‧. & Levinson, 1987, p. 74).. Nat. sit. y. In this model, politeness is a function of the sum of the three variables, each of them. n. al. er. io. ranging from 1 to n. Interlocutors thus determine the potential threat to each other’s. i n U. v. faces and the degree of politeness required in the context by computing the values of. Ch. engchi. these three variables with respect to the context. Therefore, the decision to convey an FTA with a particular linguistic form is considered in terms of the outcome of interlocutor’s calculation of these factors with respect to context. The essence of Brown and Levinson’s (1987) politeness theory can be summarized as follows: when interlocutors are performing FTAs, they consider both parties’ positive and negative faces and they utilize indirect linguistic means or convey FTAs ambiguously so as to avoid intrusion on each other’s positive and/or negative faces. According to Brown and Levinson, their politeness theory is universally applicable..

(32) 19. A number of studies, however, have argued that Brown and Levinson’s theory failed to account for politeness in such cultures as Israeli, Japanese, Chinese cultures. Fellow researchers who are concerned with the universality of Brown and Levinson’s politeness theory argued that the concept of negative face is neither cross-linguistically valid nor universally applicable. As pointed out by Clancy (1986), negative face wants appear to be insignificant and insufficient to explain Japanese politeness behavior, given the fact that Japanese culture is a collective one. 政 治 大. emphasizing conformity and reciprocity and that it is a social norm for Japanese. 立. people to be polite according to its cultural value. According to Gu’s (1990). ‧ 國. 學. discussion on the comparison between Chinese and western concepts of face, such. ‧. concepts as lian and mian-zi, although they may be rendered as counterparts to the concept of face in the western society, seem not congruous with the negative face in. y. Nat. n. al. Ch. er. io. the conformity of negative face, either.. sit. Brown and Levinson’s framework. The enactment of politeness appears not to lie in. i n U. v. Moreover, Brown and Levinson (1987) also claimed that a crucial part of the. engchi. framework is to avoid interfering others’ desire. One major way to do so is to utilize indirect way to perform FTAs. According to Brown and Levinson, interlocutors can encode their FTAs with particular linguistic forms so as to conform either on-record or off-record politeness. Nevertheless, studies on languages other than English revealed that no absolute politeness value is correlated with a specific linguistic enactment of politeness. It has been shown that indirectness is not absolutely polite cross-culturally and that politeness value correlated with a linguistic device is subject to contexts and discourse. Blum-Kulka (1987; 1990) demonstrated that Israeli people.

(33) 20. consider indirect speech acts insincere and rude rather than polite. In addition, Israeli people judge indirectness differently. A linguistic device, on- or off-record, to redress an FTA may be view as direct FTAs, while direct FTAs without redress may be indirect ones in Israeli culture. In Japanese culture, a certain degree of indirectness and politeness should be maintained in social interaction; Japanese people rely heavily on such conventional forms as honorifics and speech formulas to convey politeness (Ide, 1989; Matsumoto, 1988).. 政 治 大. Furthermore, the correlation between indirect linguistic enactment and politeness. 立. is not absolute and fixed; it may be altered or shifted by situational factors. For. ‧ 國. 學. instance, when interlocutors are involved in a highly cooperative task, being indirect. ‧. may thus hinder the accomplishment of the task, which in turn is not polite in this particular situation (Kasper, 1990; Leech, 1983). As suggested by Kasper (1990), in. y. Nat. io. sit. order to adequately describe and assess the correlation between linguistic indirectness. n. al. er. and politeness, one has to consider the context where an exchange occurs.. Ch. i n U. v. In light of the lack of absolute correlation between linguistic politeness and. engchi. politeness, other scholars thus propose alternative accounts of politeness. Wolfson (1989) argued that situational factors such as power and social distance have an influence on the extent of politeness. With power and social distance as the two axes, the degree of politeness in a particular situation may thus form a bulgy curve, instead of a diagonal straight line. In other words, the effect of power and distance on politeness is not in a positive correlation. She demonstrated that intimate interlocutors enact politeness the same way as those who are not equal in status and as those who are strangers, whereas non-intimate interlocutors, friends in equal status, and.

(34) 21. co-workers remain a certain degree of politeness when interacting. Fraser (1990, p. 232), in contrast, proposed a ‘conversational-contract’ model of politeness. Fraser argued that the requirement and the degree of politeness is negotiated and renegotiated in the immediate exchanges of conversation. Interlocutors judge, on the basis of current utterance and situation, and then determine how polite they should be in the immediate context. In addition, Pan (2000) proposed a situation-based model of politeness to account for the enactment of politeness in Chinese culture. She pointed. 政 治 大. out that Chinese politeness is highly subject to situations. Politeness in Chinese. 立. culture does not have an absolute value. The value of politeness is determined by the. ‧ 國. 學. communicative goal of the current interaction and the situation in which the current. ‧. interaction occurs. It is found that Chinese people pay attention to such situational factors as face, setting, goal, role relationship, and power relations between. y. Nat. io. sit. interlocutors. Therefore, Pan argued that Chinese people seem to enact politeness with. n. al. er. respect to the situation they are in and use politeness strategies accordingly.. Ch. i n U. v. While Brown and Levinson (1987) claimed their face-based framework to be. engchi. universally applicable and explicable, studies by other scholars, as reviewed above, showed that the face-based theory apparently fails to be universal; Brown and Levinson’s theory seems unable to accommodate the politeness behaviors observed in non-western cultures. This disparity may result from the failure to observe the discrepancy between ‘first-order’ and ‘second-order’ politeness (Fraser, 1990; Pedlow et al., 2004, p. 348; Watt et al., 1992). (Brown and Levinson seem to consider both altogether within their theory.) In Watt et al.’s terms, ‘first-order’ politeness refers to the linguistic enactment of politeness in daily social interaction. ‘Second-order’.

(35) 22. politeness, on the other hand, refers to the basis on which the linguistic enactment of politeness is established or the social norm of politeness within a particular society. This basis of politeness may vary across cultures and/or societies. In my opinion, the on- and off-record politeness strategies in Brown and Levinson’s theory are in fact the first-order politeness, which in turn are anchored on the face wants between interlocutors, namely, the second-order politeness. Given the distinction between two types of politeness, i.e., the first-order. 政 治 大. politeness or linguistic enactment of politeness and the second-order politeness or the. 立. conceptualization of politeness (Fraser, 1990; Pedlow et al., 2004; Watt et al., 1992),. ‧ 國. 學. studies on politeness should thus heed the distinction. This distinction should as well. ‧. apply to studies on children’s pragmatic development. In the course of pragmatic development, children may first learn to enact politeness appropriately with particular. y. Nat. io. sit. linguistic forms, and then as time goes by, they form or generalize the cultural norm. n. al. er. of face wants on the basis of linguistic enactment of politeness. One may, however,. Ch. i n U. v. contend that children, particularly those in the early childhood, may yet to be. engchi. socialized with the concept of politeness. Even so, children may have been able to enact politeness with linguistic devices in the early childhood, as pointed out by studies to be reviewed below in the following section. It is thus worth of exploring how children perform their politeness strategies before they become fully socialized with the concept of politeness. Therefore, the present study mainly focuses on how preschool children enact politeness with linguistic devices in the process of pragmatic development; what linguistic devices they utilize to encode politeness and whether a developmental difference can be revealed in their linguistic enactment of politeness..

(36) 23. 2.1.2 Children’s politeness One of the essential goals for children in the course of their pragmatic development is to develop the knowledge of politeness at the same time they acquire their linguistic competence. The development of politeness includes a process of linguistic socialization in which children gradually become competent of being polite according to the social norm of politeness in the culture they were born in. This development also includes a process in which children develop the ability to enact. 治 政 politeness with appropriate linguistic devices in daily 大social interaction (Pedlow et al., 立 2004). The former takes children longer time to accomplish, while the latter can be ‧ 國. 學. observed from an early age on, as pointed out by Ervin-Tripp et al. (1990). By. ‧. observing children’s enactment of politeness at different stages of development, researchers can observe not only children’s pragmatic and linguistic development but. er. io. sit. y. Nat. also their development in the socialization of politeness.. Studies on children’s politeness mostly focus on children’s linguistic enactment. al. n. v i n C h strategies. TheseUstudies are concerned with how of politeness as well as politeness engchi children utilize linguistic devices to encode politeness. They have pointed out that children have been able to demonstrate politeness at an early age and that when enacting politeness, they seem to utilize different politeness strategies at different stages or ages. The various politeness strategies and linguistic enactments can thus mirror children’s development of politeness, particularly their linguistic politeness. In the development of linguistic politeness, age is found to be a function of. politeness development (Axia, 1996; Leonard, 1993; Ervin-Tripp et al., 1990; Wood & Gardner, 1990). In her study on Italian children’s requests to ask their parents to.

(37) 24. buy them toys, Axia (1996) reported that as children grow older, they not only are more competent to use politeness, but use more politeness in their requests. Axia, however, noted that Italian children generally seem impolite when requesting to the relatives, particularly their parents, although they have the ability to be polite.2 In addition, age is found to be influential in children’s politeness use. Wood and Gardner (1990) found that children rely on the ages between their interlocutors and themselves to determine the relative status between them; older children are considered to be at a. 政 治 大. higher status in comparison to younger children when interacting with their peers.. 立. With such status difference, older children tend to make requests or orders in a direct. ‧ 國. 學. way while younger children tend to do so in a more indirect way. As pointed out by. ‧. Wood and Gardner, the status between interlocutors influences the politeness of a request. Therefore, as children grow older, they become more competent of. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. has an influence on politeness.. sit. performing politeness and they also know that age difference between interlocutors. Ch. i n U. v. Moreover, it has also been found that children’s politeness strategies and. engchi. linguistic enactment of politeness are sensitive to contexts (Axia, 1996; Ervin-Tripp; Garton & Pratt, 1990). How children perform politeness may not remain the same cross-contextually. This contextual sensitivity of politeness is also supported by children’s judgments of politeness, not just by their performance. Garton and Pratt (1990) found that children during the period from 8 to 12 years old may have developed the knowledge that the degree of politeness associated with a particular request form is not absolute. They are aware of the fact that direct requests are not. 2. Axia (1996) also pointed out that although older children are generally more competent in the enactment of politeness, they seem not to be polite constantly..

(38) 25. always impolite and indirect requests are not polite all the time. The association between politeness and request forms are relative; it may change with respect to the context in which a particular request is conveyed. Therefore, contextual differences have an effect on politeness and children may be aware of this before they turn twelve. A study conducted by Hsiao (1990) also argued for the contextual sensitivity of politeness in child language. She investigated school-age Chinese-speaking children’s. 政 治 大. request styles and polite strategies. In her questionnaires and interviews, Hsiao found. 立. that children’s requests and polite strategies formally vary with the addressees’ social. ‧ 國. 學. status and social distance or familiarity. Children were found to use more polite. ‧. requests to people with higher social status and greater social distance. Apart from contextual-sensitivity of politeness, the studies reviewed above (Axia,. y. Nat. io. sit. 1996; Graton & Pratt, 1990; Hsiao, 1990) also indicated a late development of. n. al. er. children’s politeness. Not until they are in grade school can children show a little awareness of politeness.. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. However, findings in other studies suggested that children demonstrate their politeness in an early age. The study conducted by Ervin-Tripp and her colleagues (1990) can be an excellent example. Ervin-Tripp et al.’s (1990) fine-grained study integrated the key issues concerned in many studies on politeness, such as social distance, power, cost, interactional role, age, status, as well as linguistic redress. They found that children’s use of polite forms could be observed from an early age on, around two years old. Children at an early age were found to rely on on-record polite.

(39) 26. forms to convey their control acts.3 As they grew older, children became able to perform control acts via off-record strategies such as hint. In the respect of age as a function of politeness, Ervin-Tripp and her colleagues, on a par with other studies, reported that children’s polite forms develop with age. Children were found to first use conventional or on-record forms and then develop the ability to use non-conventional or off-record forms. In addition, Ervin-Tripp et al. (1990) observed that children’s performance of. 政 治 大. control acts is subject to contexts. Contextual factors have an influence on the. 立. linguistic forms they draw upon to encode their intended control acts, when deferring. ‧ 國. 學. to politeness. They demonstrated that such contextual factors as rights and costs of a. ‧. control act influence how children enact their politeness. By rights, Ervin-Tripp et al. meant the ownership of goods, and by costs, they meant the degree of intrusion of a. y. Nat. io. sit. control act. They found that children tend to use polite forms when their control acts. n. al. er. affect the owner of goods or when the control act costs the addressee much effort to. Ch. i n U. v. accomplish. Overall, they suggested that children have demonstrated their ability to. engchi. utilize linguistic politeness properly since an early age, and their use of polite forms grows even more refined in accordance with social and/or contextual factors at around age five. On top of that, Ervin-Tripp et al. (1990) were also concerned with the correlation between being polite and being persuasive. They examined the effectiveness (or efficacy in their terms) of polite forms used by children in control acts. Their findings showed that the effectiveness of polite forms is sensitive to the power relationship 3. ‘Control acts count as attempts to produce change in the actions of others…. The terms “request”, “order”, and “command” are used in everyday English to indicate types of directives to another person to act.’ (Ervin-Tripp, et al., 1990, p. 308).

(40) 27. between interlocutors. Young children were found to fail to have their control acts complied even though they used polite forms. On the contrary, older children were found to rely on persuasive tactics to obtain the desired compliance rather than polite forms. Older children may justify their control acts by providing reasons. Ervin-Tripp et al. argued that older children often obtain the desired compliance because they tend to justify their control acts while younger children seldom provide reasons to justify their control acts and thus seldom have their interlocutors comply with their desired. 政 治 大. intention. Hence, Ervin-Tripp et al. suggested that persuasion should be considered as. 立. a separate feature of politeness, apart from social indices and tactics, since persuasion. ‧ 國. 學. was found to determine the effectiveness of a control act while politeness (social. ‧. indices and social tactics) seemed not to guarantee the intended compliance; social indices and social tactics mainly serve to identify and indicate one’s deference to. y. Nat. io. sit. social relationships and statuses. As suggested by Ervin-Tripp et al., politeness should. n. al. er. not be considered as one simple inalienable concept. It should be analyzed into three. Ch. i n U. v. aspects, including social indices, social tactics, and persuasive tactics. With such. engchi. analysis, Ervin-Tripp and her colleagues maintained that politeness mainly serves to indicate socio-dynamic relationship between interlocutors, while persuasion functions as determinant of the success of a control act. Hence, being polite may not necessarily entail the success of the intended requests. They therefore suggested that only with the distinction between politeness and persuasion can one explain the non-absolute correlation of politeness and effectiveness. Based on the findings in Ervin-Tripp et al.’s (1990) study, it can be inferred that the development of politeness may involve a process in which a child first learn to use.

(41) 28. social indices and then other linguistic devices tactically to defer to the social relationship, namely, social tactics, and finally to be able to offer appropriate or valid justifications for their control acts so as to obtain the desired compliance (i.e., persuasive tactics). Moreover, as pointed out by Ervin-Tripp et al. (1990), although children are able to be polite — use social indices in their control acts as well as social tactics to tactically deliver a control act, in the development of politeness, they seldom attain the intended compliance; most of the time, their control acts are. 政 治 大. temporized or neglected. The provision of persuasion, however, seems to increase the. 立. effectiveness of children’s control acts. Apparently, there exists a split between. ‧ 國. 學. politeness and effectiveness; being polite seems to manifest only one’s deference and. ‧. adherence to social/interpersonal relationship, while to make a request effective, the provision of justifications appears to be determinant. Therefore, children also have to. y. Nat. n. al. er. io. compliance.. sit. learn that using polite forms does not necessarily entail the obtaining of their intended. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. 2.2 Requests as a Speech Act Ever since Austin (1975) proposed the idea that we can have something done by saying something, speech acts have long been one of the mostly and widely explored areas in the field of pragmatics. Following Austin’s proposal (1975), Searle (1975; 1976) further pointed out that speech acts are the minimal units of communication and they are mainly what Austin called the illocutionary acts of an utterance. He further classified speech acts into five basic types and requests or directives are included, as.

(42) 29. shown below (See also Levinson, 1983):. (i). representatives, which commit the speaker to the truth of the expressed proposition (paradigm cases: asserting, concluding, etc.). (ii). directives, which are attempts by the speaker to get the addressee to do something (paradigm cases: requesting, questioning). (iii). commissives, which commit the speaker to some future course of action (paradigm cases: promising, threatening, offering). (iv) (v). 政 治 大 thanking, apologizing, welcoming, congratulating) 立 declarations, which effect immediate changes in the institutional. expressives, which express a psychological state (paradigm cases:. ‧ 國. 學. state of affairs and which tend to rely on elaborate extra-linguistic institutions (paradigm cases: excommunicating, declaring war,. ‧. christening, firing from employment) (Levinson, 1983, p. 240). y. Nat. er. io. sit. According to the typology, requests or requesting is paradigmatic cases of the speech act directives. Levinson (1983), however, noted that this classification is not only in. al. n. v i n lack of a systematic criterionCto identify an illocutionary h e n g c h i U act, but also away from. completeness. In fact, many other classifications of speech acts have been proposed (e.g. Bach & Harnish, 1979; Ballmer & Brennenstuhl, 1981; Leech, 1983). For example, Leech (1983) considered illocutionary acts in terms of their relative social goals of establishing and maintaining comity, and considered such illocutionary acts as ordering, asking, demanding, begging as competitive, since ‘[t]he illocutionary goal competes with the social goal’ (Leech, 1983, p. 104). In addition, Ballmer & Brennenstuhl (1981) categorized speech acts into four basic linguistic functions in correspondence to four different types of linguistic behavior serving different.

(43) 30. communicative functions. They termed the linguistic function by which the speaker gets control over the hearer as appeal. Apparently, different researchers dub such directive function with different terms, but no matter which term they use to label the illocutionary act, they all are actually dealing with the directive or request illocutionary act. As a result, the present study will consider the illocutionary act that the speaker attempts to get the hearer to do something as requests.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. 2.2.1 Requests and/or Directives. According to the taxonomy by Searle (1975), requests are a subtype of directives;. ‧. another subtype is commands. Theoretically speaking, the difference between. sit. y. Nat. requests and commands is fourfold. They are different with respect to the speaker’s. n. al. er. io. status or position, extra-linguistic institution, paralinguistic features, and linguistic. i n U. v. forms (Searle, 1979). First of all, when a directive is conveyed by a person who is at. Ch. engchi. higher status or position towards one who is at a lower status or position, it is thus a command, or otherwise it is a request. Secondly, a directive is considered as a command when a speaker performs it with an institutionalized power, for example, an authorized armed guard to a common person. Thirdly, commands are usually conveyed with emphatic intonation contour while requests are not. Lastly, commands are by default conveyed via imperatives, usually accompanied with emphatic intonation pattern, whereas requests are by default conveyed via interrogatives (Searle, 1975; 1976; 1979; Levinson, 1983). Although both requests and commands belong to one category of speech acts, the slight distinction between them distinguishes one.

(44) 31. from the other as two different paradigmatic types of directives. Studies concerned with children’s development of speech acts or communicative intents, however, consider in different ways how children have the addressee to do things with language. Some researchers, following Searle’s (1969; 1975; 1976) taxonomy of speech acts, consider the intention to have an act done by using the other person as an instrument as directives (e.g. Wood & Gardner, 1980; Elrod, 1983; Babelot & Marcos, 1999). Others see such intention as requests, which according to. 政 治 大. Searle (1975, 1976) are a subtype of directives. Still others dub such illocutionary acts. 立. as instrumental acts or control acts (e.g. Gordon & Ervin-Tripp, 1984; Ervin-Tripp et. ‧ 國. 學. al., 1990). Even though these researchers name such a speech act in different terms. ‧. without literal and lucid explanations, it can be sure that they all refer to and are concerned with one similar illocutionary act; i.e. the speaker’s wish or desire to have. y. Nat. io. sit. one thing done is fulfilled by using the addressee as the instrument.. n. al. er. Nevertheless, various terms found in the literature on children’s speech acts can. Ch. i n U. v. be justified. The discrepancy in the terminology may result from the uncertainty. engchi. whether children are able to distinguish requests finely from directives as adults do. Also, it is not clear at what age children develop the ability to distinguish these two types of speech acts. Garvey (1975) commented that children may not be able to finely distinguish requests from commands. She clearly stated that the adult distinction among requests, orders, and commands, could not be fairly observed and identified in her child corpus. In addition, it is pointed out in the literature that when requesting, children may use imperative forms (Garvey, 1974; Gordon & Ervin-Tripp, 1984; Wood & Gardner, 1980) as well as interrogative forms. Moreover, studies on.

(45) 32. children’s comprehension of directives also concur with children’s inability to tell requests from commands (Babelot & Marcos, 1999; Elrod; 1983). Elrod (1983) specifically noted that young children tended to interpret different subtypes of directives as one type. From the above review, it is obvious that children at an early age may yet to have the ability to tell commands from requests. Therefore, it seems reasonable to consider all young children’s directive illocutionary acts as one single type.. 政 治 大. Whether children distinguish requests from commands, however, still requires. 立. further studies to clarify. In order not to complicate the issues in question here, the. ‧ 國. 學. present study thus considers the illocutionary acts to get the addressee to perform an. ‧. act desired by the speaker as requests.. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat 2.2.2 Children’s requests. Ch. engchi. i n U. v. Despite the various terminologies read in previous studies, researchers generally reported that children demonstrate their communicative intents, requests in particular, in their early infancy, even before they are able to produce any linguistic elements (Bates, 1976; Bates et al., 1975; Bruner, 1981; 1983; Gordon & Ervin-Tripp, 1984; Ervin-Tripp, 1977; Hsu, 1996; Kelly, 2007; Marcos, 2001; Ninio & Snow, 1996; 1999; Zhou, 2002).4 Bates et al. (1975) argued that in the prelinguistic stage children have been able to produce such illocutionary acts as requests, or proto-imperatives in their. 4. Dore (1978), however, on the basis of Searle’s (1969) speech act theory, rejected the argument to consider prelinguistic communicative behavior or gestures as speech acts, since these communicative behavior lacked grammatical elements associated with the illocutionary acts..

數據

相關文件

Finally, we want to point out that the global uniqueness of determining the Hartree po- tential (Theorem 2.5) and the determination of the nonlinear potential in the

You are given the wavelength and total energy of a light pulse and asked to find the number of photons it

Wang, Solving pseudomonotone variational inequalities and pseudocon- vex optimization problems using the projection neural network, IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks 17

volume suppressed mass: (TeV) 2 /M P ∼ 10 −4 eV → mm range can be experimentally tested for any number of extra dimensions - Light U(1) gauge bosons: no derivative couplings. =>

Define instead the imaginary.. potential, magnetic field, lattice…) Dirac-BdG Hamiltonian:. with small, and matrix

incapable to extract any quantities from QCD, nor to tackle the most interesting physics, namely, the spontaneously chiral symmetry breaking and the color confinement..

• Formation of massive primordial stars as origin of objects in the early universe. • Supernova explosions might be visible to the most

The difference resulted from the co- existence of two kinds of words in Buddhist scriptures a foreign words in which di- syllabic words are dominant, and most of them are the