The Effectiveness of a Health Education Intervention

on Care of Traumatic Wounds

Abstract

Objective. The purpose of this study is to explore the effectiveness of wound care program for emergency traumatic patient in Taiwan.

Background. Wound care is one of the most major issues for trauma patients at home. Wound infection has been alerted mostly on medical treatment. Little is known about how health care education impact patient care of traumatic wound after discharged from emergency department.

Design. A quasi-experimental design was used by using two groups posttest.

Method. Random sampling was used to recruited participants, 89 participants in each group in emergency department at a medical center in Taiwan. A 25 minuets wound care program was given to patients in the intervention group. A questionnaire was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the program after 72 hours as patient followed up in out-patient department. The data of wound infection was collected from patient’s medical record by followed two weeks after injured.

Results. After wound care program, the knowledge, skills of wounds care, the satisfaction of health education in experimental group are better than the control group (p < .05). Wound infection rate in experimental group (9%) is lower than control group (20.2%), and statistically significant (p < .05).

Conclusion. The wound care program could increase the knowledge, skills of wound care of emergency patient, and reduce the wound infection rate.

Relevance to clinical practice. Wound care requites technical knowledge, thus, practical demonstration of teaching and self-practice is more effectiveness for patients in learning their wound care. An appropriated health program can improve the patients’ wound care and care quality.

Key word: Trauma wound care program, patient in emergency department, patient education, wound infection, knowledge and skill of wound care.

INTRODUCTION

emergency department (ED) seeking health care. Research indicates that approximately 12 million people go to emergency department for traumatic wounds care each year in the United States (Singer & Dagum 2008). Statistics also indicate that over 450 thousand people visit emergency department for trauma wounds; and people with lacerations were the most frequently seeking treatment for external wounds in 2008 in Taiwan (Department of Health Executive Yuan in Taiwan 2006). At least 7.3 million lacerations are treated annually in the US (Singer et al. 2006). In Japan, lacerations account for 14% of the daily clinical practice of those performing medical treatments (Kuwabara et al. 2006). Research suggests that

approximately 20% of patients recuperating at home need wound care (Sturkey et al. 2005); therefore, wound care is one of the most significant issues for trauma patients who return home.

BACKGROUND

The primary goal in the management of traumatic wounds is to achieve healing with optimal functional results. The best accomplished result depends on the prevention of wound infection during healing (Abubaker 2009). Wound infection is the most frequent wound complication, as well as having an important influence on wound healing (Drew et al. 2007, Singer et al. 2000, Sturkey et al. 2005). The incidence of wound infection is from 12% to 20% of the time (Kuwabara et al. 2006, Kumar & Leaper 2007, Vowden & Vowden 2009). There are many factors that influence the rate of wound infections, including the environment

where the injury was caused, the seriousness of the wound, presence of bacteria, toxicity, patient factors such as nutrition, obesity, disease management, socioeconomic status, and wound care methods (Singer & Dagum 2008, Hollander et al. 2001, Yu 2008, London 2007, Flarity & Hoyt 2011). These factors, compounded by the patients’ lack of wound care knowledge and skills, exacerbate the difficulty that patients often experience in managing wounds at home. Recommendations from research state that good execution of wound care would reduce the wound infection rate, decrease the frequency of home visits by medical personnel, and reduce medical costs (Sturkey et al. 2005, London 2007). This highlights the importance of teaching patients how to care for their wounds.

With the short treatment times in the emergency department and lack of the knowledge about caring for wounds, patient often have difficulty understating their care and discharge instructions. Research has shown that 78% of patients who discharged from ED do not understand at least one, and 34% do not understand three of the following categories: the diagnosis and pathogenesis of patient’s condition, emergency care, self-care, and follow-up visits (Engel et al. 2009). Another study by Peng et al. (2008) revealed that approximately 81% of trauma patients hoped that medical staff could provide wound care information, including wound self-care precautions and dressing procedures. Effective information about wound care after discharge from the ED to home is critically important to wound healing. However, related research on wound infections has been focused mainly on medical

treatment (Dire et al. 1995, Pfaff & Moore 2007, Hoyt et al. 2011) and chronic wound care (Rijswijk & Gray 2011). There are currently no studies that provide comprehensive health education especially for emergency trauma, lacerations and abrasions. This study aims to address these issues.

Teaching in the emergency department is especially challenging because of highly variable, unpredictable learning needs and little time for teaching. Laidley & Braddock (2000) suggested that the adult learning theory can be applied to evaluate the effectiveness of strategies for teaching patient in ambulatory setting. According to Adult Learning Theory, effective learning is based on the educational needs identified by the learners themselves (Knowles 1980). Since adults learn better through real-life problem and self-directed means, they become involved in the learning process when they come across problems (Bastable 2005). For trauma patients, wounds influence their daily life and thus require immediate attention. Patients can thus be expected to participate in wound care education voluntarily. Educational interventions that incorporate these features are more likely to positively affect learning outcomes (Allabaugh et al. 2008). However, there is little evidence related to the health education for patients in their wound care at emergency department. Thus, a Trauma Wound Care Program (TWCP) was developed to address the gaps in knowledge and abilities to care for wounds at home. This program was empirically evaluated for its effectiveness in improving outcomes.

Aim

The purpose of this study was to explore the effectiveness of a Trauma Wound Care Program (TWCP) on wound care and wound infection rates in patients with trauma-related wounds.

Research Hypotheses

1. Patient will exhibit increased in knowledge and skills of wounds care after Trauma Wound Care Program as compared to those in the routine care.

2. Patient will exhibit decreased in wound infection rates after Trauma Wound Care Program as compared to those in the routine care.

METHODS Design

A quasi-experimental design was used to investigate the effectiveness of Trauma Wound Care Program (TWCP) in subjects with trauma wounds. A two-group posttest design was implemented. Subjects were assigned to either the experimental group or control group by using a block randomization method. Those in the treatment group received the TWCP while those assigned to the control group received routine care. Outcome measures of knowledge and skills related to wound care and wound infection rate were measured for subjects in both groups.

Subjects

department at a hospital in the central district of Taiwan. Patients were 18 years old above and received emergency care for a traumatic wound and were allowed to go home following wound care but required to follow up in the hospital’s outpatient department after two or three days. Patients were excluded from this study if they had other complications such as diabetes mellitus, suicidal ideation or intent, psychiatric diagnosis, and wounds caused by domestic violence. An effect size was calculated to determine sample size. To detect a 10 percentage point difference in the wound infection rate between the groups at á = 0.05, a total of 80 subjects were needed in each group to achieve a power of 90% to detect a statistically significant result.

This study first enrolled 322 patients who had lacerations and abrasions and were admitted to the emergency department; however, only 178 of these returned for out-patient follow-up and 89 in each group completed the survey, a 55.3% completion rate in total. Intervention: Trauma Wound Care Program (TWCP)

The development of TWCP for the emergency patient with traumatic wounds was based on adult learning theory, synthesized literature, and clinical experts’ experience. The program was conducted using health education, skill demonstration, actual practice, and discussion. The Trauma Wound Care Program (TWCP) was a 25 minute program that included the following components: 1. Nurses’ instruction on wound care with a poster (care procedures were presented in realistic pictures with pithy formulaic form); 2. nurses’ demonstration on

the skills of wound care; 3. patients’ practicing on the skill of wound care by using a prosthetic model; and 4. a guideline booklet, a paper flyer in same content of poster’s instruction and a list of supplies for wound (laceration and abrasion) care to bring home. Three instructors were trained for the intervention to maintain consistency throughout the study. Instructor competency in the intervention and consistency in delivering it were evaluated by the researchers.

Patients were randomized into treatment group, in blocks of size 2. Patients were assigned to different groups by allocating random permutations of treatments within each block. Those randomized to the control group received routine care, approximately 10 minutes, which included provision of methods of wound care by verbal communication only, original flyers with information of wound care, and poster with wound care. The content of wound care is the same in both groups. But, the way of delivery the wound care management is different. There is no any demonstration and practicing, and information of supplies of wound care in the control group.

Instrument

The instrument to measure wound care was the developed from a synthesized literature review of wound care. The instrument contained 42 questions divided into five subscales. The first subscale consisted of demographic data including age, education, gender, marriage, occupation, experience of previous injury and wound care, and history of disease etc. The

second subscales gathered the wound characteristics such as the reason of injury, time of admitted ED after injury, and wound management before admitted ED, the type of wound, location of wound, size of wound, sutured, and foreign body in the wound etc. The third subscales consisted 24 true/false items of knowledge of wound care which contained basic knowledge of wound care (6 items), knowledge of wound dressing (11 items), and

knowledge of wound infection (7 items). The fourth subscales focused on skills of wound care. A 11 items with score on being fully implementation (2), partial implementation (1), no/wrong implementation (0) was built. The fifth subscales converged on patients’

satisfaction of program and self care. A seven items with five-point Likert scale, from ‘Strongly agree’ (5) to ‘Strongly disagree’ (1), was constructed. Higher scores indicated better knowledge and skills of wound care and higher level of satisfaction of program and self-care. One open question was given to know “what reasons affect to take care of your wound?” The instrument required 10 minutes to complete.

Reliability and Validity of Instrument

The instrument’s readability, accuracy and adaptability were adequate as determined by the review of expert panel and pilot study with a sample of 31 patients. The face validity of instrument was determined by an expert review with a CVI value of 0.92. Concurrent validity measures the consistency of responses of

the participant by using different measurements or criteria at the same time. In the pilot test, the skill of wound care was also observed by researcher. Using the same 11 items of skill of wound care, nurses measured the patient’s skill of wound care while patient displayed his/her wound care in prosthetic model. The scoring is the same as the patient’s self-measurement from fully implementation (2), partial implementation (1), to no/wrong implementation (0). The measurement of patient’s skill of wound care by nurses served as the criterion for concurrent validity. The moderate

correlation (r = 0.56, p<.001) was found between patient self–report of skill of wound care and nurse measured patient’s skill of wound care,

indicating a good concurrent validity. The reliability of the instrument was

determined from a pilot study. The internal consistency of the instrument was measured using a KR20 0.70 in knowledge of wound care, Cronbach’s alpha 0.87 in skill of wound care, and Cronbach’s alpha 0.90 in satisfaction of program and self-care at pilot study.

Wound infection was defined when wound appear infection sign such as redness, swell, heat, pain and have antibiotic prescription from doctors. The wound infection rate was collected from patient’s medical record by followed two weeks after injured.

Data collection and Analysis

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the university hospital. Once patient meeting admission criteria was admitted to the emergency department, patients

were invited to participate in the study and informed consent was obtained. All participants discharged from the hospital after treatment and were scheduled to return after two or three days for follow-up care. Outcome measures of patient’s self report of knowledge of, skills related to, and satisfaction with wound self-care were collected at patients’ follow up visits at outpatient department. Data related to wound infection were gathered from patients’ medical records two weeks after the date of injury. The data were collected from February to April, 2010.

The data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. T-test analysis was applied to compare means of knowledge and skill of wound care in two groups; and chi-square test was used to compare means of wound infection in two groups. The alpha level of 0.05 was designated as statistical significance.

RESULTS Descriptive data

In this study, 52.8% (n = 94) of the participants were male. The age range was from 18 to 77 years with an average of 33 years old. The majority of participants were single (65.2%) and held college degrees (53.3%). The most frequent cause of trauma was accident (59.6%) and falls (14.6%). Most of the patients were admitted to the hospital by themselves (52.8%). Laceration wounds were 44.9%, abrasion wounds were 39.3% and both combined wounds were 15.8% of wound types in this study. The wounds were mostly located on upper limbs (36.3%) and lower limbs (33.4%). The chi-square test of homogeneity result showed that

participants’ demographic data and wound characteristics were homogeneous between the treatment and control groups.

The effects of Intervention program on patients’ knowledge and skills of wound care

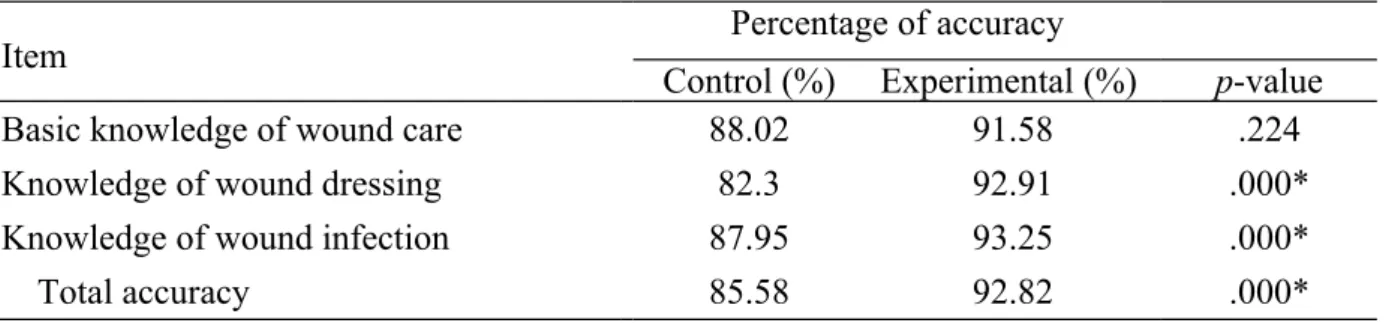

The average score was 21.88 (SD=1.45) in the experimental group and 20.06 (SD=2.39) in the control group. There was a mean accuracy of 92.82% of all questions in the

experimental group while the mean accuracy was 85.58 % in the control group. In order to evaluate the effectiveness of TWCP, t-test was performed. Result showed that patients’ knowledge of wound care was higher in the experimental group than in the control group and resulted in statistically significant (p< .001) (Table 1).

The result indicated that patients in the experimental group performed the skills of wound care better than those in the control group. As shown in Table 2, the average score of skill performance of wound care was 20.91 (SD=1.77) in the experimental group and 16.74 (SD=5.52) in the control group; which revealed a statistically significant difference in two groups (p < .05). Those who received the TWCP had better skills of wound care than did those who received routine care. These findings support the hypothesis that the patient will exhibit increased in knowledge and skills of wounds care after Trauma Wound Care Program as compared to those in the routine care. In the open question, 18% (n=32) of patients

indicated that they avoided exerting force when cleaning their wounds, especially when gauze was stacked on their wound or when they were afraid of pain.

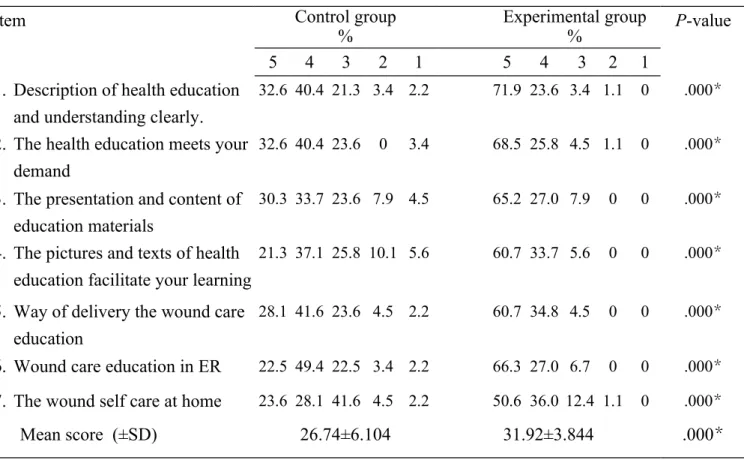

Table 3 showed patients’ satisfaction with the program and wound self-care at home. Results indicated higher scores on satisfaction in the experimental group (31.92 ± 3.844) as compared to the control group (26.74 ± 6.104) and this difference was statistically significant (p< .05). Moreover, each question showed statistically significant difference (p< .05).

Table 4 showed that wound infection rates were different between the two groups. The wound infection rate was 9% (n=8) in the experimental group and was 20.2% (n=18) in control group, which was statistically significant difference (p < .05). These findings support the hypothesis that the patient will exhibit decreased in wound infection rates after Trauma Wound Care Program as compared to those in the routine care.

DISSCUSSION

Patients’ knowledge of wound care

This study evaluates the impact of a wound care program on trauma patients admitted through the emergency department. The study shows that patients who received the TWCP have better knowledge of wound care than those in the control group. The patients in the control group had a low level of correct answers on Question 6 “The wound can be

disinfected only by using mercurochrome or hydrogen peroxide” (48.3%) and Question 13 “If the wound has discharge, using povidone-iodine is better than saline in cleaning the wound” (48.5%); more than half of those in the control group did not know how to select a disinfectant solution. In contrast, patients in the experimental group had better knowledge of selecting disinfectant solutions (82%, 83.1%), which was statistically significant difference

from control group. Many researchers have established and updated knowledge on wound dressing (Singer & Dagum 2008, Dire et al. 1995, Fernandez & Griffiths 2008). In the traditional aspect of wound care, povidone-iodine or other disinfectants were provided for wound care. However, studies have shown that applying povidone-iodine to exposed tissue prolongs the time of wound healing (Yu 2008, Aronoff et al. 1980, Shetty & Duthie 1990). Studies also show that wound infections can be reduced with the use of saline water, boiled water, or distilled water (Fernandez & Griffiths 2008), and antibiotic ointment (Dire et al. 1995, Singer & Dagum 2008). Although those updated knowledge of wound care were all provided in two groups, people in experimental group, with realistic care demonstration and practicing the wound care with saline water and antibiotic ointment in the TWCP, tend to remember more new knowledge. Thus, when educate patients the new knowledge, specially changing the preserved traditional methods of wound care, it is critical to teach patients the correct methods and knowledge by appreciated method.

In response to Question 21 “Traumatic wounds are vulnerable to infection unless oral antibiotics are taken”, in total only 36% in control group and 40.0% in experimental group of participants answered the question correctly. Studies have shown that simple traumatic wounds don’t need to be treated with routine prophylactic antibiotics given either orally or by injection (Cummings & Del Beccaro 1995; Zehtabchi et al. 2011). The low number of correct answers remained even after the experimental group underwent health education, suggesting

that many patients are unfamiliar with the timing of antibiotic usage. The oral antibiotics were not used by the time discharged in the two groups. All patients only got the antibiotic ointment for wound care while discharged. Patients rarely attempt to understand the effects of the medications prescribed to them. Palmer and Bauchner (1997) indicated that the general public held misconceptions about the type of conditions that require antibiotics. The use of oral and injected antibiotics for traumatic wounds is currently recommended only when the wound is visibly infected, for deep leg wounds, and for people with immune dysfunction (Singer & Dagum 2008). Wound care education further should be more focused on the reason and timing of taking antibiotics.

Patients’ skill of wound care

The result indicates that patients’ wound self-care skills in TWCP more effectively than those in the control group. Different way of conveying wound care from control group, wound care demonstration and practicing were performed in the TWCP. The results of this study echo the research of Hsu et al. (2007), indicating that learning demonstrations and personal practices can be effective in learning. Specially, the complex process of dressing wounds needs real experience for clinical outpatients. The self-care skills relating to wound care include: knowing how a wound should heal, keeping the wound moist, keeping the wound clean and infections free, and identifying the problems (London 2007). When looking at skills of wound cleaning in Question 5 and 6, ways of using a cotton swab in cleaning

wound, only over half of participants (60.7%, 51.7%) in control group were fully competent as compared to the experimental group (87.6%, 96.6%). The results reveal the evidence that patients are uncertain about the proper procedures of wound cleaning. Most of the patients mistook the eschar that forms from the wound discharge as a new skin and do not think these need to be cleaned. They were also unsure of the level of pressure to use for wound cleaning with saline and usually just wiped the wound lightly. Most of the wounds inspected in the control group were covered with a mixture of eschar and ointment with dirt, which could lead to the wound infection. The patients in the experimental group, on the other hand, were having actual experience in using cotton with wound care before discharge had better skills of wound care. Based on the adult learning theory, the intervention included patients’ actual practice with the prosthetic model, which incorporated the preferences and needs of patients with trauma wounds. People learn best when they are engaged in practical experience of learning how to do their own care.

The result of open-ended questions shows that another obstacle in wound dressing is fear of pain. Eighteen percent (n=32) of the participants in this study indicated that they were afraid to exert force when cleaning their wounds. This leads to wound discharge forming into eschar, which in turn of covered the granulation tissue causing redness and swelling. Studies indicate that patients experience moderate to severe pain which is the biggest obstacle to overcome when dressing the wound (Meaume et al. 2004, Moffatt et al. 2003). The pain is at

its worst specially when lifting the gauze from the wound. A painkiller can be used before wound dressing to alleviate pain (Briggs & Torrai Bou 2003; Flarity & Hoyt 2011). Other alternatives to ease the pain are local anesthetic EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics cream) or lidocaine injections (Evans & Gray 2005). In addition, the material of non-adhesive dressings such as acticoat, mepial, and urgotul to eliminate the pain was also suggested (Chin 2007). Using appropriate pain relief prior to dressing wounds may be effective in wound care.

Satisfaction with traumatic wound care program and self-care

The results show that following the TWCP intervention patients were more satisfied with the information received that those received routine care; the difference was significant. The results are consistent with studies about the satisfaction with the proper education for learners (Allabaugh et al. 2008, Bastable 2005). In this study, only 51.7% of patients in the control group indicated that they were satisfied with their wound self care at home. The results reflect that many patients do not understand the discharge instructions for wound care provided in the emergency department (Engel et al. 2009). With only orally instruction and related flyers would not satisfy the patients’ wound self-care at home.

Moreover, patients in the experimental group had over a 90% rating of satisfaction with the design of health instruction and material as compared to 60% in the control group. Printed materials are widely used in health education because they are consistent, reusable, portable, and affordable (Hoffmann & Worrall 2004; Cutilli 2006). Although the control group

received verbal instruction of wound care, flyers with procedure of wound care, and viewed the poster of wound care, their learning outcomes were less favorable and they were less satisfied. With the real practicing in the wound care, the participants in the TWCP were provided with a flyer in same content of poster’s instruction and a guideline list of supplies for wound care. The materials to bring home in the TWCP were familiar for patient while at emergency room. When designing written heath care materials, the content of health

information should be conform to patient perceptions and needs. That is congruent with adult learning theory, which contends that people learn when they realize the information is

relevant to them (Knowles 1980). The wound care education in adults is on the integration of available knowledge and experience to make the learning process more convenient and applicable. That is, learning methods that increase motivation and comprehension also increased patient care satisfaction (Fernsler & Cannon 1991). Health education integrated the principles of adult learning to provide health knowledge and skills acquisition for patients in order to achieve optimal self-care. Thus, this study supports that a well-designed wound care manual that not only facilitate patient learning also can satisfy patients’ needs.

Wound infection

With routine wound care, the infection rate was 20.2% in the control group. This finding falls into the high range of infection rate (10 to 20%) contracted in acute traumatic wounds (Kuwabara et al. 2006, Kumar & Leaper 2007). The wound infection rate in the experimental

group following TWCP was 9%. The difference between the wound infection rates of two groups was statistically significant ((p < .05). This supports the assertion that proper wound care education and application can decrease the wound infection rate (Sturkey et al. 2005, London 2007). Hollander (1995) pointed out that although factors that lead to wound

infections are already present once the wounds are sustained. But, proper wound care can still play a crucial role in preventing wound infections. A patient-centered approach intervention, an evaluation of outcomes that patients care about, would provide a high quality not only in management of chronic wounds (Rijswijk & Gray 2011), but also acute wound care in emergency department. With actual practice in the prosthetic model, patients with traumatic wounds (laceration and abrasion care) performed better wound self-care at home. In this study, only 15 minutes more of time consuming in interventions in the experimental group, the outcome of patients’ wound self-care was evidently distinction. The factors that lead to wound infections are varied and hard to control (Singer & Dagum 2008, Flarity & Hoyt 2011). An intervention such as TWCP in the emergency department can improve patients’ wound self-care which result a lower wound infection rate.

Limitations

There are some limitations of the study. The study is only focused on patients with acute trauma laceration and abrasion wound and cannot be generalized to patients with other types of wound. Second, the study did not include a pre-test and a follow-up test, and thus there is

no comparison of differences before and after the program, and know how well patients retained the wound care acquired. Finally, the researchers only collected data on the patients’ self-care and wound infection; other long-term effects of the injuries were not studied.

CONCLUSION

The results of this study reveal that participants who received the TWCP intervention had greater knowledge, skills and satisfaction related to self care of wounds than those who received routine discharge instructions in emergency department. This finding illustrates that it is more effective to provide health education with actual demonstrations and skill

development rather than to simply verbal instruction and hand out health flyers. Following the TWCP intervention, the patients display better knowledge and skills of wound self-care and lower wound infection rates. This finding on the effects of health education on wound care can be used as empirical evidence to support the provision of health education to improve patient self-care.

Relevance to clinical practice

Patients can only absorb limited amounts of information in an urgent situation such as receiving treatment in an emergency department. An appropriated component of health education is needed to address patients’ care. This should be supplemented with proper health education to increase learning outcomes and health care after discharge.

The correct and new knowledge of wound care has to be spread out for the general population. The application of new knowledge of wound care, such as using of saline water

or distilled water result better wound care, need to be taught by clinical nurses. Besides, the reason and timing of taking antibiotics for wound infection need to be clarified while caring traumatic wound. Patient learning self care by the real demonstration and actuarial experience will enhance their skills and have better care quality of their wounds which diminished the wound infection. A well designed health care education will provide better wound care and improve the quality of patient’s life.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all of the participants who took part in this study. We also sincerely thank the China Medical University Hospital, Taiwan, for financially supporting this research (DMR100-144).

Contributions

Study Design: LH, YC; Data Collection and Analysis: LH, YC, WC, HH; Manuscript Preparation: LH, YC. MS.

Conflict of interest: None

References

Abubaker AO (2009) Use of prophylactic Antibiotics in Preventing Infection of Traumatic Injuries. Dental clinics of North America 53, 707-715.

Teens: Using Trauma Nurses Talk Tough Presentation with Pretest and Posttest Evaluation of Knowledge and Behavior Changes. Journal of Trauma Nursing 15, 102-111.

Aronoff GR, Friedman SJ, Doedens DJ & Lavelle KJ (1980) Increased serum iodide concentration from iodine absorption through wounds treated topically with povidone-iodine. The American Journal of The Medical Sciences 279, 173-176. Bastable SB (2005) Essentials of patient education. Boston: Jones and Bartlett. Briggs M & Torra i Bou JE (2003) Understanding the origin of wound pain during

dressing change. Ostomy Wound Manage 49, 10-12.

Chin YF (2007) Nursing management of wound care pain. Journal of Nursing 54, 87-91. Cummings P & Del Beccaro MA (1995) Antibiotics to prevent infection of simple

wounds: a meta-analysis of randomized studies. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 13, 396-400.

Cutilli CC (2006) Do your patients understand? Providing culturally congruent patient education. Orthopaedic Nursing 25, 218-224.

Department of Health Executive Yuan, R.O.C. (Taiwan). Available on website://

http://www.doh.gov.tw/CHT2006/DM/DM2_2.aspx?now_fod_list_no=10910&clss_n Dire DJ, Coppola M, Dwyer DA, Lorette JJ & Karr JL (1995) Prospective evaluation of

topical antibiotics for preventing infections in uncomplicated soft-tissue wounds repaired in the ED. Academic Emergency Medicine 2, 4-10.

England. International Wound Journal 4, 149-155.

Engel KG, Heisler M, Smith DM, Robinson CH, Forman JH & Ubel PA (2009) Patient comprehension of emergency department care and instructions: are patients aware of when they do not understand? Annals of Emergency Medicine 53, 454-461 e15. Evans E & Gray M (2005) Do topical analgesics reduce pain associated with wound

dressing changes or debridement of chronic wounds? Journal of Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nursing 32, 287-290.

Fernandez R & Griffiths R (2008) Water for wound cleansing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD003861.

Fernsler JI & Cannon CA (1991) The whys of patient education. Seminars in Oncology Nursing 7, 79-86.

Flarity LK & Hoyt KS (2011) Wound care and laceration repair for nurse practitioners in emergency care part I. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal 32, 360-372.

Hoffmann T & Worrall L (2004) Designing effective written health education materials: Considerations for health professionals. Disability And Rehabilitation 26, 1166-1173. Hollander JE, Singer AJ, Valentine S & Henry MC (1995) Wound registry: development

and validation. Annals of Emergency Medicine 25, 675-685.

Hollander JE, Singer AJ, Valentine SM & Shofer FS (2001) Risk factors for infection in patients with traumatic lacerations. Academic Emergency Medicine 8, 716-720. Hoyt KS, Flarity K & Shea SS (2011) Wound care and laceration repair for nurse

Hsu JF & Lai HR (2007) A Study of The fifth and sixth Grade Elementary School Students’ Knowledge, Attitude, Behavior Intention, and Educational Need toward CPR in Taipei City. Jian Kang Cu Jin Yu Wei Sheng Jiao Yu Xue Bao 28, 127-148.

Knowles MS (1980) The modern practice of adult education. New York: Adult Education. Kumar S & Leaper DJ (2007) Classification and management of acute wounds. Surgery

26, 43-47.

Kuwabara K, Imanaka Y & Ishizaki T (2006) Quality and productive efficiency in simple laceration treatment. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 12, 164-173.

Laidley TL & Braddock CH (2000) Role of Adult Learning Theory in Evaluating and Designing Strategies for Teaching Residents in Ambulatory Settings. Advances in Health Sciences Education 5, 43-54.

London F (2007) Patient education: teaching patients about wound care. Home Healthcare Nurse 25, 497-500.

Meaume S, Teot L, Lazareth I, Martini J & Bohbot S (2004) The importance of pain reduction through dressing selection in routine wound management: the MAPP study. Journal of Wound Care 13, 409-413.

Moffatt CJ, Franks PJ & Hollinworth H (2003) An international perspective on wound pain and trauma. Ostomy Wound Manage 49, 12-14.

Palmer DA & Bauchner H (1997) Parents’ and physicians’ views on antibiotics. Pediatrics 99, 862-863.

suture wound care for emergency department patients. VGH Nursing 25, 284-292. Pfaff JA & Moore GP (2007) Reducing risk in emergency department wound

management. Emergency Medicine Clinics of North America 25, 189-201.

Rijswijk LV & Gray M (2011)Evidence, Research, and Clinical Practice: A Patient-Centered Framework for Progress in Wound Care. Ostomy Wound Management 57, 26-38. Shetty KR & Duthie EH Jr. (1990) Thyrotoxicosis induced by topical iodine application.

Archives of Internal Medicine 150, 2400-2401.

Singer AJ, Thode HC & Hollander JE (2006) National trends in ED lacerations between 1992 and 2002. The American journal of emergency medicine 24, 183-188.

Singer AJ & Dagum AB (2008) Current management of acute cutaneous wounds. The New England Journal of Medicine 359, 1037-1046.

Singer AJ, Mach C, Thode HC, Jr, Hemachandra S, Shofer FS & Hollander JE (2000) Patient priorities with traumatic lacerations. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine 18, 683-686.

Sturkey EN, Linker S, Keith DD & Comeau E (2005) Improving wound care outcomes in the home setting. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 20, 349-355.

Vowden KR & Vowden P (2009) The prevalence, management and outcome for acute wounds identified in a wound care survey within one English health care district. Journal of Tissue Viability 18, 7-12.

Yu PJ (2008) The Wound Nursing.Taipei: Farseeing publishing.

Logistics,Limitations, and Contributions to Emergency Medicine Research. Emergency Medicine 18, 637-643.

Table 1. The difference of knowledge of traumatic wound care between two groups

Item Percentage of accuracy

Control (%) Experimental (%) p-value

Basic knowledge of wound care 88.02 91.58 .224

Knowledge of wound dressing 82.3 92.91 .000*

Knowledge of wound infection 87.95 93.25 .000*

Total accuracy 85.58 92.82 .000*

*P<.05 t –test

Table 2. The difference of skills of wound care between two groups

Item Control group

% Experimental G% p-value

2 1 0 2 1 0

1. Materials preparation: sterile cotton swab, sterile gauze, saline, antibiotic ointment, adhesive tape.

60.7 27.0 12.3 92.1 7.9 0 .000*

2. Wash hands before change dressing 79.8 9.0 11.2 95.5 4.5 0 .002* 3. When remove the gauze, first using the saline

for moist if the gauze stick on the wound.

66.3 12.4 21.3 94.4 2.2 3.4 .000*

4. Observe whether the appearance of swelling, pain or pus-like discharge on the wound.

79.8 11.2 9.0 95.5 4.5 0 .003*

5. Using a cotton swab dipped with saline to clean and disinfect the wound.

60.7 13.5 25.8 96.6 1.1 2.2 .000*

6. A cotton swab should be used to clean the wound in concentric circles from the inside out

and not back and forth to swab the wound. 7. After cleaning the wound, using a cotton swab

wiped with antibiotic ointment on the wound.

83.1 7.9 9.0 98.9 0 1.1 .001*

8. the size of gauze is at least 1cm behind the wound edge.

70.8 7.9 21.3 87.6 9.0 3.4 .001*

9. When cover the wound, the hand should avoid contacting the covering side of gauze.

73.0 6.7 20.2 93.3 3.4 3.4 .001*

10. Use ventilated adhesive tape to fix gauze. 76.4 3.4 20.2 95.5 1.1 3.4 .001*

11. Wash hands after change dressing 33.1 16.9 16.9 83.1 10.1 6.7 .000*

Mean score (±SD) 16.74±5.518 20.91±1.769 .000*

*P<.05 t –test

Table 3. The difference of satisfaction in wound care and self-care between two groups

Item Control group

% Experimental group% P-value

5 4 3 2 1 5 4 3 2 1

1. Description of health education and understanding clearly.

32.6 40.4 21.3 3.4 2.2 71.9 23.6 3.4 1.1 0 .000*

2. The health education meets your demand

32.6 40.4 23.6 0 3.4 68.5 25.8 4.5 1.1 0 .000*

3. The presentation and content of education materials

30.3 33.7 23.6 7.9 4.5 65.2 27.0 7.9 0 0 .000*

4. The pictures and texts of health education facilitate your learning

21.3 37.1 25.8 10.1 5.6 60.7 33.7 5.6 0 0 .000*

5. Way of delivery the wound care education

28.1 41.6 23.6 4.5 2.2 60.7 34.8 4.5 0 0 .000*

6. Wound care education in ER 22.5 49.4 22.5 3.4 2.2 66.3 27.0 6.7 0 0 .000*

7. The wound self care at home 23.6 28.1 41.6 4.5 2.2 50.6 36.0 12.4 1.1 0 .000*

Mean score (±SD) 26.74±6.104 31.92±3.844 .000*

P<.05 t –test

Table 4. The comparison of wound infection between two groups

Items Control group Experimental group p-value*

Wound infection .034*

yes 18 (20.2) 8 (9.0)

no 71(79.8) 81 (91.0)