Relative importance of atherosclerotic risk factors for

coronary heart disease in Taiwan

Kuo-Liong Chien

a,c, Fung-Chang Sung

c,d, Hsiu-Ching Hsu

a, Ta-Chen Su

a,

Wei-Deng Chang

band Yuan-Teh Lee

aa

Department of Internal Medicine,

bDepartment of Emergency Medicine National Taiwan University Hospital,

cInstitute of Preventive Medicine, National Taiwan University College of Public Health and

dInstitute of Environmental Health, China Medical University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Received6 April 2004 Accepted 7 February 2005Background The relative importance of atherosclerotic risk factors, such as hypertension, dyslipidemia, diabetes and smoking, was associated with cardiovascular events and varied among different ethnic groups. For a population with relatively low coronary heart disease (CHD) such as Asian-Pacific countries, it is crucial to differentiate the roles of these risk factors.

Methods We examined the relative importance of various risk factors for CHD in a community-based cohort in Taiwan, consisting of 3602 adults aged 35 and older with a median follow-up time of 9.0 years since 1990. Regular death certificate verification and medical record reviews were performed in the follow-up activities.

Results There were 85 cases defined as CHD. In the Cox proportional hazard analysis, men were at higher risk than women [hazard risk (HR) = 2.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.39–3.56]. Hypertension was the most common risk factor for CHD. Dyslipidemia, especially lowered high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, also played an important role (HR = 2.09, 95% CI = 1.33–3.29) in CHD events. Hypertension had a greater influence in males (HR = 6.08, P < 0.001) than in females (HR = 2.80,P < 0.001). No independent association was found for smoking or body mass index in cardiovascular events. Conclusion This study found that in a community-based cohort, hypertension, and dyslipidemia attribute an important role to cardiovascular events. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 12:95–101 c 2005 The European Society of Cardiology

European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation2005, 12:95–101

Keywords: risk factors, coronary heart disease, cohort study

Introduction

Atherosclerotic risk factors, such as hypertension, dia-betes and dyslipidemia, represent significant predictors for several cardiovascular diseases including coronary heart disease (CHD) [1,2]. Intervention against these risk factors can efficiently reduce the risk of cular diseases [3,4]. Evidence indicates that cardiovas-cular disease can be viewed as a predictable and preventable disease [5–7]. However, the relative impor-tance of the risk factors varies in different ethnic groups. Different events can be related to different risk profiles.

In the Asian-Pacific area, because of relatively low CHD, the associated risk factors and the impact on the disease may differ from western countries [8,9].

Although clinical trials have provided scientific evidence for single risk factor intervention on one primary endpoint [10–12], only a prospective cohort design can elucidate the relative importance of multiple risk factors on multiple outcomes. For example, the Framingham Heart study has contributed substantially to our understanding of the causes of CHD [6]. Risk score algorithms have been developed for predicting CHD events and are useful for Caucasian populations, but implications of these risk scores for Asian-Pacific populations remain undetermined. The present study investigated the risk profiles for CHD in a community cohort in Taiwan. The

Correspondence and requests for reprints to Yuan-Teh Lee, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, No. 7, Chung-Shan S. RD, Taipei, Taiwan, 100.

Tel: + 886 2 2356 2013; fax: + 886 2 2351 9736; e-mail: klchien@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw; ytlee@ha.mc.ntu.edu.tw 1741-8267 c 2005 The European Society of Cardiology

cohort participants were first recruited and examined in 1990 and 1991 and CHD and other cardiovascular diseases (CVD) that have developed subsequently have been documented annually over an 11-year follow-up period. Several statistical parameters for assessing the relative importance of prognostic factors were compared in this community.

Materials and methods

Study population

This community-based cohort has been described else-where [13]. Briefly, the participants were 1703 men and 1899 women aged 35 years and above, homogenous in Chinese ethnicity. The Chin-Shan Community Cardio-vascular (CCC) study cohort was established in 1990 [14,15], approximately 30 km north of metropolitan Taipei, in Taiwan.

For the baseline survey, all study participants were individually interviewed with a structured questionnaire. Trained medical students canvassed door-to-door visits, with the assistance of community leaders, to extend invitations for the baseline survey to collect information including socio-demographic characteristics, lifestyle, dietary characteristics, personal and family histories of diseases and hospitalizations. With the consent of participants, the cardiologists from National Taiwan University Hospital conducted the medical examinations at baseline and follow-up check-up with the approval of the hospital institutional review committee. A 12-lead electrocardiography was also performed for each partici-pant and two cardiologists, who were blinded to the study, evaluated the results. Residents who were very ill were excluded from this study cohort. Persons with previous myocardial infarction were included, but we did not include their survival time for risk measures in the present study. Only newly diagnosed cases of cardiovas-cular disease were used. The non-respondents were 95 refusals and 652 individuals who worked out of the town and so were unavailable to participate (respondent rate 82.8%).

Specimen collection and examination

A venous blood sample of a 12-h overnight fast was taken from each participant, refrigerated and transported within 6 h back to the National Taiwan University Hospital. Serum samples were then stored at – 701C prior to the batch assay for total cholesterol, triglyceride, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, and high-density lipopro-tein (HDL) cholesterol and other biochemical measure-ments. Standard enzymatic tests for serum cholesterol and triglyceride were used (Merck 14354 and 14366, Germany, respectively). High-density lipoprotein choles-terol (HDL-C) levels were measured in supernatants after the precipitation of specimens with magnesium chloride phosphotungstate reagents (Merck 14993) [16].

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentra-tions were calculated as ‘total cholesterol minus choles-terol in the supernatant’ by the precipitation method (Merck 14992) [17].

Definition of binary risk factors

Hypertension was defined according to the criteria established by the Sixth Joint National Committee on Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure [18]. Persons with systolic blood pressure higher than 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure higher than 90 mmHg, and/or receiving anti-hypertensive med-ication were considered as hypertensive. Diabetes mellitus was defined as fasting blood sugar levels higher than 126 mg/dl or use of oral hypoglycemic agents or insulin injections [19]. Dyslipidemia was defined as to have serum cholesterol Z 240 mg/dl, HDL-cholesterol r 40 mg/dl, LDL-cholesterol Z 160 mg/dl or triglycer-ide Z 200 mg/dl. Smoking status was defined by current smoking history. Individuals with a body mass index Z 25 were considered as overweight, and Z 30 as obese, based on the WHO criteria [20], or Z 27 for Taiwanese adult survey data [21].

Ascertainment of incident CHD

Incident cases in the CCC cohort were ascertained by reviewing medical records and death certificates from the local vital statistics office, and by bi-annual follow-up household visits. Individuals with coronary insufficiency during the follow-up period were considered as non-fatal CHD cases, including cardiac intervention procedures such as angioplasty, and stent deployment. Death from acute myocardial infarction, sudden death and coronary artery lesion were considered as fatal CHD. All pre-liminary diagnoses, medical records, death certificates and interviews with patient relatives, for the purpose of gathering information of related events, were presented to this committee. The physicians conducted the conference to clarify causes of events and deaths without knowing the status of the subjects. The study committee members conducted medical record verification and diagnostic meetings on a regular basis [14,22].

Statistical analysis

Sex and age-specific incidence rates of CHD were calculated using person-years at risk between the base-line survey and December 2001. Mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and prevalence rates of binary measures were determined.

The relative importance of risk factors in the Cox regression was measured by several parameters. First, standardized hazard risk and related P values were compared [6]. The age-adjusted coefficients were obtained from the proportional hazard model. Each of the standardized hazard coefficient measures was

compared; its magnitude represented the contribution of a risk factor to the CHD events. The statistical significance (i.e., the P value) also gives an indication of the importance of the risk factor. Second, the area under (the receiver operating characteristic, ROC) curve (AUC) was used to compare the prognostic importance of continuous variables [23]. It can be considered as a global performance indicator of a prognostic factor. Third, we used the parameter, population attributable risk (PAR), in the binary risk factor analysis. Population attributable risk can be used to describe the percentage of the risk reduction if the risk factor was eliminated from the population. It is a useful indicator to evaluate the impact on the overall occurrence of cardiovascular events [24]. Fourth, we used the Gini index (a summary index for the Lorenz curve), to describe the impact fraction of a risk factor and to provide greater prognostic meaning and public health implication [25]. Finally, we used the proportion of explained variation (PEV) in the Cox model – another index for predictive accuracy [26]. In this index, the R-square parallel in the general linear model, can be considered to evaluate the relative importance of risk factors. The best-fit model was chosen

by stepwise selection options (entry P = 0.2, stay P = 0.1). If the selected model fit the data, we checked the assumption if the hazard ratio was proportional over time. All data analyses were performed using SAS (version 8.02; SAS institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina, USA) and STATA version 7.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

As of December 2001, the whole cohort was followed for an average of 8.5 years, with a median of 9.0 years. There were 85 cases defined as CHD events, including 64 non-fatal CHD and 21 non-fatal CHD events. Figure 1 plots the incidence of CHD by gender and age. The CHD rates, with an average 3.92 per 1000 person-years, increased from 1.19–9.01 per 1000 person-years in men as the age increased, and from 0.88–5.41 per 1000 person-years in women.

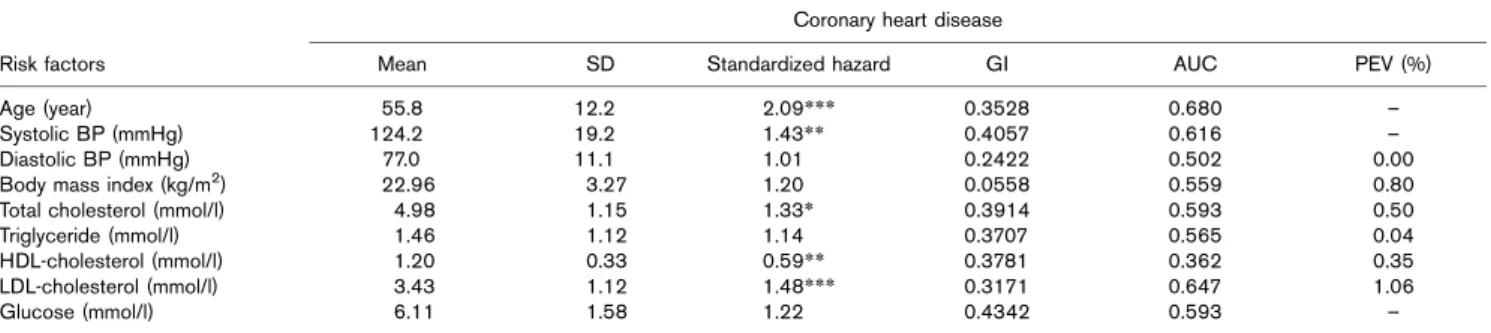

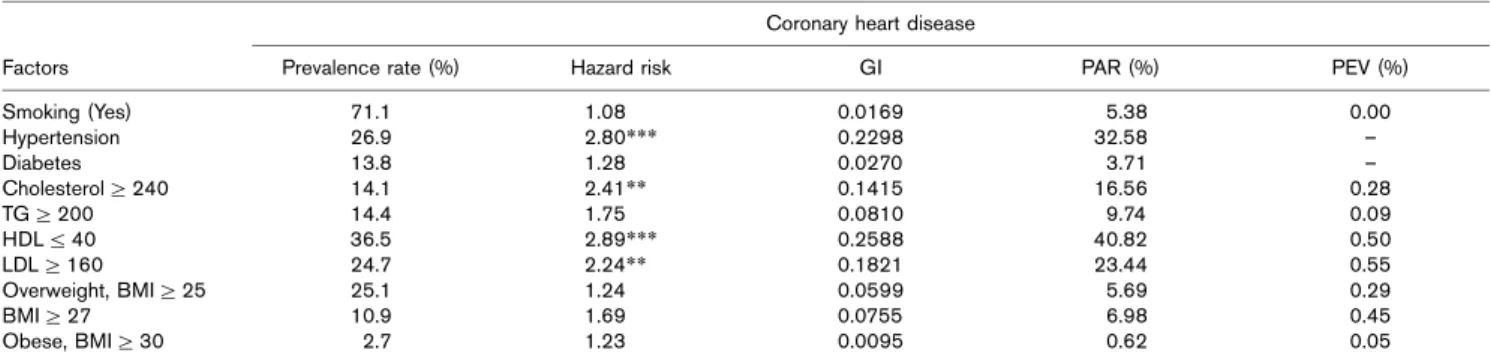

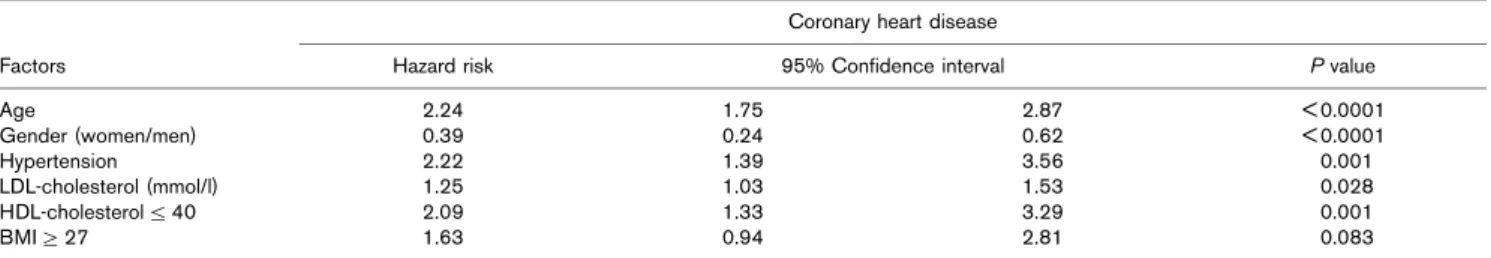

Tables 1–4 summarize the contribution of each selected risk factor on the incidence of CHD events. In the continuous variable model, age, hypertension, and HDL-cholesterol exhibited a significant contribution to CHD events for both men (Table 1) and women (Table 2), while triglyceride was also significant among women and LDL-cholesterol significant among men. In the binary model, also, hypertension, high cholesterol and high LDL cholesterol and low HDL cholesterol were significant predictors of CHD for men (Table 3), while hyperten-sion, low HDL cholesterol, high LDL cholesterol and overweight status significantly predicted a CHD event for women (Table 4). Smoking, diabetes and obesity were not significant factors for predicting a CHD event in both genders Table 5.

By stepwise selection for the best subset model to predict a CHD event, we found that age, gender, continuous LDL cholesterol, hypertension, low HDL cholesterol and a body mass index (BMI) greater than 27 kg/m2 were included in the model, and global test of proportional hazard assumption was not rejected (P = 0.317). In this

Fig. 1 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 35−44 45−54 55−64 ≥65 Age group Incidence rate (/1000 person-year) Men Women

Age- and gender-specific incidence rates of CHD in the Chin-Shan Community cohort, 1990–2001.

Table 1 The estimated standardized hazards, Gini index (GI), area under receiver operating curve and proportions of explained variance of various continuous factors for coronary heart disease in men: the Chin-Shan Community Cardiovascular Cohort study

Coronary heart disease

Risk factors Mean SD Standardized hazard GI AUC PEV (%)

Age (year) 55.8 12.2 2.09*** 0.3528 0.680 –

Systolic BP (mmHg) 124.2 19.2 1.43** 0.4057 0.616 –

Diastolic BP (mmHg) 77.0 11.1 1.01 0.2422 0.502 0.00

Body mass index (kg/m2) 22.96 3.27 1.20 0.0558 0.559 0.80

Total cholesterol (mmol/l) 4.98 1.15 1.33* 0.3914 0.593 0.50

Triglyceride (mmol/l) 1.46 1.12 1.14 0.3707 0.565 0.04

HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) 1.20 0.33 0.59** 0.3781 0.362 0.35 LDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) 3.43 1.12 1.48*** 0.3171 0.647 1.06

Glucose (mmol/l) 6.11 1.58 1.22 0.4342 0.593 –

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; – , negative value; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PEV, proportion of explained variance; AUC, area under receiver operation curve.

model, age, hypertension and low HDL cholesterol had the highest hazard risk of more than 2.0.

Discussion

To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first paper detailing a systematic investigation for the relative importance of risk factor profiles in CHD for the ethnic Chinese based on a community cohort. This study demonstrated that systolic blood pressure and age are shared risk factors for

CHD in the population. High-density lipoprotein cho-lesterol played an important role in CHD events for both men and women. Occurrence of CHD events was also associated with LDL-cholesterol in men, and obesity in women. (We observed increasing CHD events among men and women with diabetes mellitus, but not to any level of significance).

A national health interview survey has indicated that the mortality rates from CHD were prevalent among ethnic

Table 2 The estimated standardized hazards, Gini index (GI), area under receiver operating curve and proportions of explained variance of various continuous factors for coronary heart disease in women: the Chin-Shan Community Cardiovascular Cohort study

Coronary heart disease

Risk factors Mean SD Standardized hazard GI AUC PEV (%)

Age (year) 54.1 12.4 3.06*** 0.3338 0.793 –

Systolic BP (mmHg) 126.9 21.8 2.15*** 0.5123 0.757 2.14

Diastolic BP (mmHg) 77.3 11.2 1.58** 0.4092 0.620 –

Body mass index (kg/m2) 23.93 3.51 1.28 0.0649 0.603 –

Total cholesterol (mmol/l) 5.24 1.18 1.25 0.2844 0.593 0.94

Triglyceride (mmol/l) 1.39 1.04 1.30* 0.3499 0.615 –

HDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) 1.25 0.32 0.52** 0.3166 0.364 –

LDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) 3.67 1.15 1.35 0.3874 0.610 1.27

Glucose (mmol/l) 6.12 1.89 1.03 0.3905 0.475 –

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; – , negative value; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PEV, proportion of explained variance; AUC, area under receiver operation curve.

Table 3 The prevalence rate, estimated hazards, Gini index (GI), population attributable fraction, and proportions of explained variance of various binary factors for coronary heart disease in men: the Chin-Shan Community Cardiovascular Cohort study

Coronary heart disease

Factors Prevalence rate (%) Hazard risk GI PAR (%) PEV (%)

Smoking (Yes) 71.1 1.08 0.0169 5.38 0.00 Hypertension 26.9 2.80*** 0.2298 32.58 – Diabetes 13.8 1.28 0.0270 3.71 – Cholesterol Z 240 14.1 2.41** 0.1415 16.56 0.28 TG Z 200 14.4 1.75 0.0810 9.74 0.09 HDLr 40 36.5 2.89*** 0.2588 40.82 0.50 LDL Z 160 24.7 2.24** 0.1821 23.44 0.55 Overweight, BMI Z 25 25.1 1.24 0.0599 5.69 0.29 BMI Z 27 10.9 1.69 0.0755 6.98 0.45 Obese, BMI Z 30 2.7 1.23 0.0095 0.62 0.05

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; – , negative value; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; BMI, body mass index; PAR, population attributable risk; PEV, proportion of explained variance; TG, triglycerides.

Table 4 The prevalence rates, estimated hazards, Gini index (GI) population attributable fraction, and proportions of explained variance of various binary factors for coronary heart disease in women: the Chin-Shan Community Cardiovascular Cohort study

Coronary heart disease

Factors Prevalence rate (%) Hazard risk GI PAR (%) PEV (%)

Smoking (Yes) 5.3 1.46 0.0115 2.39 – Hypertension 32.4 6.08*** 0.4252 62.18 0.73 Diabetes 12.6 1.52 0.0361 6.14 – Cholesterol Z 240 19.8 1.71 0.0942 12.31 0.58 TG Z 200 12.0 2.32 0.1072 13.71 – HDLr 40 27.0 2.64** 0.2001 30.67 – LDL Z 160 31.5 2.24* 0.2217 28.11 1.87 Overweight, BMI Z 25 34.4 2.11* 0.1921 27.65 – BMI Z 27 17.7 2.17 0.1251 17.15 – Obese, BMI Z 30 4.9 0.73 0.0163 – 1.35 0.12

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; – , negative value; BP, blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; BMI, body mass index; PAR, population attributable risk; PEV, proportion of explained variance; TG, triglycerides.

populations in Taiwan [27]. Therefore, CHD prevention in the community should be a first priority for any public health promotion [14]. Blood pressure control has been considered as the most important risk factor in prevent-ing CHD [18,28]. In the Framprevent-ingham study, diastolic blood pressure was not considered a dependent risk factor [29,30]. Our study showed that diastolic blood pressure could add more information in explaining CHD events. Consistent with other Taiwanese studies, as well as the Framingham study, this study clearly demonstrates a strong inverse relationship between HDL-cholesterol and CHD risk [31–33]. Hypertension appeared a greater population attributable risk of CHD than hypertension. Furthermore, LDL cholesterol played a more important role as contributor to CHD events than did total cholesterol by AUC criteria.

Diabetes mellitus played a non-significantly independent role in CHD events. Effects of diabetes on CHD might be blunted by other atherosclerotic risk factors such as hypertension and dyslipidemia, due to clusters of metabolic syndrome. Although having no independent role in CHD, multifactor intervention on diabetes is still mandatory to prevent atherosclerosis progress. Also, the role of diabetes in women’s health has been clearly demonstrated [34,35]. A recent study clearly showed that lifestyle intervention could slow diabetes progression in a high-risk population; so aggressive intervention by exercise and lifestyle modifica-tion is strongly recommended [36].

In this study, smoking rate was much higher in men than in women (71.1 versus 5.3%). We cannot find smoking as an independent risk factor for CHD. The direction of hazard risk was still more than one (1.08 in men and 1.46 in women), indicating that smoking was an insignificant risk factor for CHD. We did not specify the amount of smoking per day. The binary variable of smoking status reduced the power of the predictive model. Lack of association of smoking and CHD events might be the result of a failure to define lifelong non-smokers as the reference group, and non-differential misclassification of smoking status also decreased the magnitude of risk estimation. The recent meta-analysis showed wide hazard risk ranges for smoking on CHD events [37].

Associated with hypertension, dyslipidemia, and adult-onset diabetes, obesity makes a significant contribution to metabolic syndrome. But, many population-based cohort studies cannot demonstrate an independent role for obesity in cardiovascular events [37]. Consistent with findings observed in the Framingham and PROCAM studies, we barely found a moderate effect by either continuous BMI or binary obesity index, [38,39]. It implied that obesity might serve as an intermediate factor for atherosclerosis. Body weight control is an essential element in any preventive program in the community and should still be emphasized.

In this study, we used several methods to evaluate the relative importance of risk factors for CHD, and we found that standardized hazards gave more consistent results for continuous variables. The Gini index, a global indictor for prognostic factors, also provided comparable results. However, the method of proportions of explained variance did not show good discrimination. This might have been due to the censored data for CHD events (up to 90%). The amount of predictive accuracy is often low even if there are high significant risk factors [26]. This study had several limitations. First, we could not separate the independent effects of various risk factors due to correlation among these risk factors. Sophisticated statistical methods such as a classification tree may provide another way to handle dependency and interac-tion between risk factors. Second, we used a single baseline measure for risk factors to assess their impact on further events. Time-dependent covariate models or composite risk factors such as metabolic syndrome have a higher power for causation reference. Furthermore, because risk factors were measured once in this cohort, issues of regression to mean and regression–dilution bias should be considered [40]. Intra-individual variability of risk factor profiles and correction for regression–dilution bias should be implemented if the intervals of measure-ments were long [41]. Third, the effects of lifestyle pattern change on the cohort since 1990 due to economic progress in Taiwan were not estimated. In addition, the effectiveness of treatment regimens for hypertension,

Table 5 The best selection subset for prediction of coronary heart disease in Chin-Shan Community Cohort follow-up

Coronary heart disease

Factors Hazard risk 95% Confidence interval P value

Age 2.24 1.75 2.87 < 0.0001 Gender (women/men) 0.39 0.24 0.62 < 0.0001 Hypertension 2.22 1.39 3.56 0.001 LDL-cholesterol (mmol/l) 1.25 1.03 1.53 0.028 HDL-cholesterolr 40 2.09 1.33 3.29 0.001 BMI Z 27 1.63 0.94 2.81 0.083

hyperlipidemia and diabetes greatly modified the indivi-dual outcomes. Finally, although biological mechanisms suggested independent causal roles for each risk factor, only clinical trial interventional studies can confirm the causal inferences generated by observational studies. Although this cohort population cannot fully represent the Taiwanese population, the results can still be generalized to adult Taiwanese, and is particularly suitable to identify risk factors responsible for precipitat-ing CHD in this country, which has a relatively lower incidence then western countries.

In summary, this study confirmed the presence of a consistent and strong relationship between elevated blood pressure and lower HDL-cholesterol in cardio-vascular risk.

Acknowledgements

The study was partly supported by National Science Council (NSC 90-2314-B-002-089) and National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH 91-S063).

References

1 Grundy SM, Balady GJ, Criqui MH, Fletcher G, Greenland P, Hiratzka LF, et al. Primary prevention of coronary heart disease: guidance from Framingham: a statement for healthcare professionals from the AHA Task Force on Risk Reduction. American Heart Association. Circulation 1998; 97:1876–1887.

2 Dyken ML, Wolf PA, Barnett HJM, Bergan JJ, Hass WK, Kannel WB, et al. Risk factors in stroke: a statement for physicians by the subcommittee on risk factors and stroke of the stroke council. Stroke 1984;

15:1105–1111.

3 Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Risk factor changes and mortality results. Multiple risk factor intervention trial. JAMA 1982; 248:1465–1477.

4 Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial Research Group. Mortality after 16 years for participants randomized to the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Circulation 1996; 94:946–951.

5 Cholesterol, diastolic blood pressure, and stroke: 13,000 strokes in 450,000 people in 45 prospective cohorts. Prospective studies collaboration. Lancet 1995; 346:1647–1653.

6 Stokes J 3rd, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, Cupples LA, D’Agostino RB. The relative importance of selected risk factors for various manifestations of

cardiovascular disease among men and women from 35 to 64 years old: 30 years of follow-up in the Framingham Study. Circulation 1987; 75:65–73.

7 Wilson PWF, Castelli WP, Kannel WB. Coronary risk prediction in adults (the Framingham Heart Study). Am J Cardiol 1987; 59:91–94. 8 An epidemiological study of cardiovascular and cardiopulmonary disease

risk factors in four populations in the People’s Republic of China baseline report from the P.R.C.-U.S.A. collaborative study. Circulation 1992; 85:1083–1098.

9 Lawes CM, Rodgers A, Bennett DA, Parag V, Suh I, Ueshima H, et al. Blood pressure and cardiovascular disease in the Asia Pacific region. J Hypertens 2003; 21:707–716.

10 Major outcomes in moderately hypercholesterolemic, hypertensive patients randomized to pravastatin vs. usual care: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT-LLT). JAMA 2002; 288:2998–3007.

11 Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, Whitney E, Shapiro DR, Beere PA, et al. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA 1998; 279:1615–1622.

12 The Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study Group. Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Lancet 1994; 344: 1383–1389.

13 Lee YT, Lin RS, Sung FC, Yang CY, Chien KL, Chen WJ, et al. Chin-Shan Community Cardiovascular Cohort in Taiwan: baseline data and five-year follow-up morbidity and mortality. J Clin Epidemiol 2000; 53:836–846.

14 Chien KL, Sung FC, Hsu HC, Su TC, Lin RS, Lee YT. Apolipoprotein A1 & B, and stroke events in a community-based cohort in Taiwan: Report of Chin-Shan Community Cardiovascular Study. Stroke 2002; 33:39–44.

15 Su TC, Jeng JS, Chien KL, Sung FC, Hsu HC, Lee YT. Hypertension status is the major determinant of carotid atherosclerosis: a community-based study in Taiwan. Stroke 2001; 32:2265–2271.

16 Warnick GR, Benderson J, Albers JJ. Dextran sulfate-Mg2 +precipitation

procedure for quantitation of high-density-lipoprotein cholesterol. Clin Chem 1982; 28:1379–1388.

17 Wieland H, Seidel D. A simple specific method for precipitation of low-density lipoproteins. J Lipid Res 1983; 24:904–909.

18 Joint National Committee. The sixth report of the Joint National Committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med 1997; 157:2413–2446.

19 Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care 1997; 20:1183–1197.

20 World Health Organization. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report on a World Health Organization consultation on obesity, Geneva, 3–5 June, 1997. 1998. Geneva,

WHO/NUT/NCD/98.1.

21 Huang PC, Yu SL, Lin YM, Chu CL. Body weight of Chinese adults by sex, age and body height and criterion of obesity based on body mass index. J Chinese Nutr Soc 1992; 17:157–172.

22 Wang TD, Chen WJ, Chien KL, Seh-Yi Su SS, Hsu HC, et al. Efficacy of cholesterol levels and ratios in predicting future coronary heart disease in a Chinese population. Am J Cardiol 2001; 88:737–743.

23 Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 1982; 143:29–36.

24 Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern epidemiology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 1998.

25 Lee WC. Characterizing exposure-disease association in human populations using the Lorenz curve and Gini index. Stat Med 1997; 16:729–739.

26 Schemper M, Henderson R. Predictive accuracy and explained variation in Cox regression. Biometrics 2000; 56:249–255.

27 Huang ZS, Chiang TL, Lee TK. Stroke prevalence in Taiwan. Findings from the 1994 National Health Interview Survey. Stroke 1997; 28:1579–1584.

28 World Health Organization-International Society of Hypertension Guidelines Subcommittee. 1999 World Health Organization-International Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension. Guidelines Subcommittee. J Hypertens 1999; 17:151–183.

29 Kannel WB. Hypertension and the risk of cardiovascular disease. Hypertension: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. 1990; 101–117.

30 Stokes IJ, Kannel WB, Wolf PA, D’Agostino RB, Cupples LA. Blood pressure as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The Framingham study- 30 years of follow-up. Hypertension 1989; 13(Suppl I):I-13–I-18. 31 Lien WP, Lai LP, Shyu KG, Hwang JJ, Chen JJ, Lei MH, et al. Low-serum,

high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration is an important coronary risk factor in Chinese patients with low serum levels of total cholesterol and triglyceride. Am J Cardiol 1996; 77:1112–1115.

32 Lyu L, Shieh M, Ordovas JM, Lichtenstein AH, Wilson PWF, Schaefer EJ. Plasma lipoprotein and apolipoprotein levels in Taipei and Framingham. Atheroscler Thromb 1993; 13:1429–1440.

33 Shieh SM, Shen M, Fuh MMT, Chen YDI, Reaven GM. Plasma lipid and lipoprotein concentrations in Chinese males with coronary artery disease with and without hypertension. Atherosclerosis 1987; 67:49–55.

34 Beckman JA, Creager MA, Libby P. Diabetes and atherosclerosis, epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management. JAMA 2002; 287:2570–2581.

35 Grundy SM, Benjamin IJ, Burke GL, Chait A, Eckel RH, Howard BV, et al. Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation 1999; 100:1134–1146.

36 Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, Valle TT, Hamalainen H, Ilanne-Parikka P, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001; 344:1343–1350.

37 Smoking, body weight, and CHD mortality in diverse populations. Prev Med 2004; 38:834–840.

38 Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation 1998; 97:1837–1847.

39 Assmann G, Cullen P, Schulte H. Simple scoring scheme for calculating the risk of acute coronary events based on the 10-year follow-up of the prospective cardiovascular Munster (PROCAM) study. Circulation 2002; 105:310–315.

40 MacMahon S, Peto R, Cutler J, Collins R, Sorlie P, Neaton J, et al. Blood pressure, stroke, and coronary heart disease. Part 1, Prolonged differences in blood pressure: prospective observational studies corrected for the regression dilution bias. Lancet 1990; 335:765–774.

41 Lewington S, Thomsen T, Davidsen M, Sherliker P, Clarke R. Regression dilution bias in blood total and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and blood pressure in the Glostrup and Framingham prospective studies. J Cardiovasc Risk 2003; 10:143–148.