Article

Financial Mechanisms for Climate Change:

Lessons from the Reform Experiences of the

IMF

Wen-Chen Shih

*ABSTRACT

The “Copenhagen Accord” issued after the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP 15) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), while not unanimously adopted, was nevertheless an important decision relating to further development of the climate change regime. In this twelve-paragraph document, there are seven paragraphs that touch upon issues relating to financial resources and financial mechanisms. Furthermore, COP 16 to the UNFCCC adopted the Cancun Agreements, which also lay down various significant provisions for financial mechanisms, including the newly created Green Climate Fund. This illustrates the importance of financial mechanisms in the adoption and implementation of policies related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. The design and effectiveness of such financial mechanisms—especially the role governance structure plays in ensuring the democratic outcome of producing fair and equitable resources generation and allocation processes—will determine whether any financial mechanism can achieve its goal of assisting developing countries to implement climate change mitigation and adaptation policies.

International financial mechanisms for development assistance have been in

* Professor of Law, Department of International Business, National Chengchi University. E-mail:

wcshih@nccu.edu.tw. This article is based on research from two projects funded by the National Science Council: Financial Mechanisms for Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation (NSC 99-2621-M-004-002) and Governance Reform in the IMF (NSC 99-2410-H-004-153). It was orally presented at the 8th Asian Law Institute Conference on 26 May 2011. The author is thankful for all the

questions and comments raised by the audience.

operation since the establishment of the Bretton Woods institutions, that is, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank Group in 1947. Five decades of intense scrutiny directed at the governance structure of the IMF finally resulted in a series of governance reforms in starting in 2008.

Could the IMF’s experience with these reforms offer valuable input regarding the design of the governance structure of existing or new financial mechanisms for climate change mitigation and adaptation? This will be the main research question this article seeks to answer.

CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION... 584

II. FINANCIAL MECHANISMS FOR CLIMATE CHANGE... 585

A. Definition and Functions of Financial Mechanisms for Climate Change... 585

B. Different Types of Climate Change Financial Mechanisms by Different Yardsticks... 587

1. Purposes of Financial Mechanisms ... 587

2. Scale ... 588

3. Sources of Funding... 588

4. Types of Activities Funded by Financial Mechanisms... 589

C. Design Elements and Guiding Principles of Financial Mechanisms for Climate Change with Particular Focus on Governance Structure... 590

1. Generation: Resource Mobilization ... 590

2. Delivery: Resources Distribution ... 591

3. Administration: Governance of Institutional Arrangement... 592

III. GOVERNANCE REFORM OF THE IMF AND LESSONS LEARNED... 593

A. What Needs to be Reformed ... 593

1. Decision-Making ... 594

2. Organisational Arrangement... 596

B. The Reform Program ... 601

IV. LESSONS LEARNED... 606

A. A Note of Caution ... 606

B. Lessons Learned ... 607

V. CONCLUSION... 610

I.INTRODUCTION

Financial mechanisms have always been an important, yet controversial institutional pillar of the international climate change regime. Early on, negotiations leading up to the United Nation Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) demonstrated the amount of controversy surrounding the design and governance structure of the financial mechanisms under the Convention.1 Under Article 11 of the UNFCCC, a financial mechanism “shall function under the guidance of and be accountable to the Conference of the Parties . . . .” and “shall have an equitable and balanced representation of all Parties within a transparent system of governance.” When developed country Parties (Annex I Parties) undertook concrete legal obligations to reduce six types of greenhouse gases (GHGs) under the Kyoto Protocol, the conceptual scope of financial mechanism was broadened, and the types of such mechanisms became extremely diversified. In the current post-2012 climate change negotiations, financial mechanisms have again become part of the crucial negotiation agenda. While the Copenhagen Accord issued after the COP 15 to the UNFCCC was not unanimously adopted, it nevertheless represents an important decision relating to further development of the climate change regime. In this twelve-paragraph document, there are seven paragraphs that touch upon issues relating to financial resources and financial mechanisms. Furthermore, COP 16 to the UNFCCC adopted the so-called Cancun Agreements, which also lay down various significant provisions relating to financial mechanisms, including the newly created Green Climate Fund. This illustrates the importance of financial mechanisms that holds for adopting and implementing policies related to climate change mitigation and adaptation. Among the highly debated issues concerning the design of financial mechanisms, governance structure has always been a crucial one. The design and effectiveness of financial mechanisms—especially the role governance structure plays in ensuring democratic, fair and equitable resources generation and allocation processes—will determine whether any financial mechanism can achieve its goal of assisting developing countries to implement climate change mitigation and adaptation policies.

International financial mechanisms for development assistance have been in operation since the establishment of the Bretton Woods institutions,

1. This refers to the debate and negotiation over whether the then World Bank-operated Global Environmental Facility (GEF) in its pilot phase should be designated the financial mechanism under the Convention. The ultimate result was to designate the GEF the “interim” financial mechanism, with the condition that the GEF “should be appropriately restructured and its membership made universal to enable it to fulfill the requirements of Article 11.” United Nations the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), art. 21.3, May 9, 1992.

namely the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank Group, in 1947. Both the IMF and the climate change financial mechanisms provide different forms of financial assistance to developing countries according to the objectives of their respective founding legal instruments. Their respective modus operandi and organization structure also differ. The IMF has published a staff position note in 2010 that outline a scheme called the “Green Fund” to help mobilized resources that can be transferred to developing countries to finance climate-related expenditures.2 However, it is also noted that the IMF is not in a position to create, finance or manage such climate change financial mechanism. With such a limited interaction or relationship, there is virtually no existing literature that focuses simultaneously on these two types of financial mechanisms. Nonetheless, this paper notes that, governance issues have always been a crucial but controversial issue for all of these financial mechanisms. Five decades of intense scrutiny directed at the governance structure of the IMF finally resulted in a series of governance reforms starting in 2008. Could the IMF’s experiences with these reforms offer valuable input regarding the design of the governance structure of existing or new financial mechanisms for climate change mitigation and adaptation? This will be the main research question this article seeks to answer.

This article begins with an introduction to the financial mechanisms for climate change, followed by an overview of the IMF’s governance reforms. Part IV provides an analysis of how the IMF’s experience with reforms could offer some lessons for financial mechanisms for climate change, with particular focus on changes to the IMF’s governance structure.

II.FINANCIAL MECHANISMS FOR CLIMATE CHANGE

A. Definition and Functions of Financial Mechanisms for Climate Change Financial mechanisms can be defined as “method[s] or source[s] through which funding is made available, such as bank loans, bond or share issue, reserves or savings, [and] sales revenue.”3 To define financial mechanism, the “Glossary of Climate Change Acronyms” on the UNFCCC website states that

[D]eveloped country Parties (Annex II Parties) are required to provide financial resources to assist developing country Parties

2. HUGH BREDENKAMP & CATHERINE PATTILLO, FINANCING THE RESPONSE TO CLIMATE

CHANGE (2010), available at http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/spn/2010/spn1006.pdf. 3. Financial mechanism, BUSINESSDICTIONARY.COM,(2011)

implement the Convention. To facilitate this, the Convention established a financial mechanism to provide funds to developing country Parties. The Parties to the Convention assigned operation of the financial mechanism to the Global Environment Facility (GEF) on an on-going basis, subject to review every four years. The financial mechanism is accountable to the COP.4

In line with these two definitions, for the purposes of this article, financial mechanisms for climate change will be defined as pre-determined standards and procedures set by an institution through which funding is mobilized and disbursed for the purpose of climate change mitigation and adaptation. Similar terms such as climate finance5 or carbon finance6 are also used in the relevant literature.

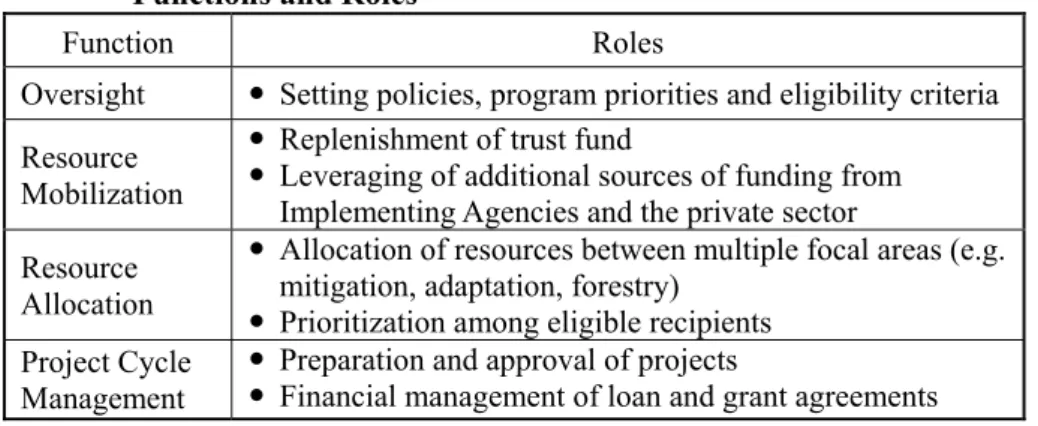

The main function of financial mechanisms for climate change is to assist countries to adopt and to implement policies for climate change adaptation and mitigation. According to the World Resources Institute, the typical functions of such mechanisms include oversight, resource mobilization, resource allocation, project cycle management, standard setting, scientific and technical advice, and accountability. The corresponding roles for such mechanisms are illustrated in Table 1.7

Table 1: What Will a Climate Finance Mechanism Do? Typical Functions and Roles

Function Roles Oversight y Setting policies, program priorities and eligibility criteria Resource

Mobilization

y Replenishment of trust fund

y Leveraging of additional sources of funding from Implementing Agencies and the private sector Resource

Allocation

y Allocation of resources between multiple focal areas (e.g. mitigation, adaptation, forestry)

y Prioritization among eligible recipients Project Cycle

Management

y Preparation and approval of projects

y Financial management of loan and grant agreements

4. UNFCCC, Finacial Mechanism,

http://unfccc.int/cooperation_and_support/financial_mechanism/items/2807.php (last visited Sep. 30, 2011).

5. See, e.g., CLIMATE FINANCE:REGULATORY AND FUNDING STRATEGIES FOR CLIMATE CHANGE AND GLOBAL DEVELOPMENT (Richard B. Stewart et al. eds., 2009).

6. The World Bank Group, for example, uses this term in its “Carbon Finance Unit.” SeeCarbon Finance at the World Bank,THE WORLD BANK, http://go.worldbank.org/9IGUMTMED0 (last visited Sep. 30, 2011).

7 . ATHENA BALLESTEROS ET AL., POWER, RESPONSIBILITY, AND ACCOUNTABILITY: RE-THINKING THE LEGITIMACY OF INSTITUTIONS FOR CLIMATE FINANCE 3 tbl.1 (2010), available at http://pdf.wri.org/power_responsibility_accountability.pdf.

Function Roles Standard

Setting

y Development and approval of performance metrics y Development and approval of environmental and social

safeguards Scientific and

Technical Advice

y Advice on appropriate policies and best available technologies

y Advice on scientific trends and risk assessment Accountability

y Monitoring and evaluation of project and portfolio performance

y Review and inspection of problematic projects

Five out of the seven functions of financial mechanisms for climate change relate to the governance of the mechanisms: oversight, resource mobilization, resource allocation, standard setting, and accountability. This clearly illustrates the importance of institutional design and governance structure of any financial mechanism for climate change.

B. Different Types of Climate Change Financial Mechanisms by Different

Yardsticks

There are a variety of financial mechanisms for climate change. Different types of financial mechanisms for climate change may be variously categorized by using different yardsticks, such as purpose, scale, sources of funding, and the types of activities they fund. The following paragraphs will briefly introduce the broad range of financial mechanisms for climate change by using these four different yardsticks.

1. Purposes of Financial Mechanisms

Based on their purpose, financial mechanisms for climate change can be categorized as for mitigation, for adaptation, or for both purposes. The Emissions Trading Scheme of the European Union (EU ETS) is a type of financial mechanism for mitigation, as its main purpose is to reduce the emissions of GHGs within the EU.8 Under the international climate change regime, the Adaptation Fund set up under the Kyoto Protocol at its third meeting of the parties9 is a financial mechanism for climate change

8. However, the revised EU ETS will become a type of financial mechanism for both climate change mitigation and adaptation. According to the revised ETS Directive adopted on April 23, 2009, member states can determine how to use the proceeds from the auction of allowances. Nevertheless, 50% of the proceeds must be used according to Article 10.3 of the revised Directive, which includes funding for both mitigation and adaptation measures.

adaptation. The GEF mainly funded projects for mitigation purposes, although adaptation projects are funded as well from the Least Developed Countries Fund and the Special Climate Change Fund, both of which were established at COP 7 of the UNFCCC and are administered by the GEF. At the same COP, Parties to the UNFCCC also instructed the GEF to support pilot and demonstration projects for certain adaptation programs.10

2. Scale

Depending on the scale of a financial mechanism or the platform on which, it operates, it may be categorized as an international/multilateral, regional, bilateral, or unilateral financial mechanism for climate change. For example, all of the financial mechanisms under the international climate change regime are international/multilateral financial mechanisms. The EU ETS, as well as certain financial mechanisms supported or administered by regional development banks (e.g. the three different types of carbon finance mechanisms operated by the Asian Development Bank11) are regional financial mechanisms. Bilateral financial mechanisms often involve funding provided by one country (usually a developed country) to support particular types of projects or activities for climate change mitigation or adaptation undertaken by an eligible country (usually a developing country). For example, the International Climate Initiative established by Germany12 in 2008 and the Environmental Transformation Fund set up by the UK13 in the same year are two such bilateral financial mechanisms. Unilateral financial mechanisms are mostly established domestically. Examples include the Brazil Amazon Fund set up by Brazil in 200814 and the Indonesia Climate Change Trust Fund set up by Indonesia15 in 2009.

3. Sources of Funding

The sources of funding for a financial mechanism can come from the

Protocol, Dec. 3-15, 2007, Bali, Decision, at 3, FCCC/KP/CMP/2007/9/Add.1, 1/CMP.3 (Mar. 14, 2008).

10. Adaptation,GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY (GEF), http://www.thegef.org/gef/adaptation (last visited Sep. 30, 2011).

11. Climate Change, ASIAN DEV.BANK, http://beta.adb.org/themes/climate-change/main (last visited Sep. 30, 2011).

12. INTERNATIONAL CLIMATE INITIATIVE, http://www.bmu-klimaschutzinitiative.de/en/home_i (last visited Sep. 30, 2011).

13. Environmental Transformation Fund, WASTE &RESOURCES ACTION PROGRAMME (WRAP), http://www.wrap.org.uk/recycling_industry/information_by_material/organics/etf.html (last visited Sep. 30, 2011).

14. AMAZON FUND, http://www.amazonfund.org/ (last visited Sep. 30, 2011).

15. INDONESIA CLIMATE CHANGE TRUST FUND (ICCTF), http://www.icctf.or.id/ (last visited Sep. 30, 2011).

public sector and the private sector.16 At the international scale, public sources can come from the traditional Overseas Development Aid (ODA), concessional debt, loan guarantee, or technology transfer arrangements. At the domestic level, funding from public sources may include government budget allocation (a carbon tax, for example), or special levy (for example, an air pollution control fee). Funding from the private sector might include credit offsets in developed countries (for example, the EU ETS), insurance, or foreign direct investment. Currently, most of the financial mechanisms for climate change, including all of those under the international climate change regime, receive funding from the public sectors of different nations. However, some financial mechanisms such as most of the carbon funds administered by the World Bank Group, receive funding from both the public and private sectors. The Prototype Carbon Fund, for instance, raises funds from seven private companies and six governments.17

4. Types of Activities Funded by Financial Mechanisms

Financial mechanisms for climate change can support a wide range of activities, including project lending and program or policy lending, and may also be used for investment only. Financial mechanisms for project lending entail providing funding and/or technologies for a specific project such as a solar power plant. Financial mechanisms for program or policy lending are meant to support a program of action or a set of policies, for example, a set of subsidy programs to support the renewable energy sector. Financial mechanisms for investment only use their funds to purchase offsets generated by emissions reduction projects, such as the certified emissions reductions (CERs) generated by the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) projects. The CDM under the Kyoto Protocol is a typical financial mechanism for project lending. The GEF started as a financial mechanism for project lending as well, but began program/policy lending in 2008 when it started to provide “a long-term and strategic arrangement of individual yet interlinked projects that aim at achieving large-scale impacts on the global environment.”18 Some of the carbon funds administered by the World Bank Group are financial mechanisms for investment purposes.

16. RICHARD B.STEWART ET AL., CLIMATE FINANCE:KEY CONCEPTS AND WAYS FORWARD 3 (2009),http://belfercenter.ksg.harvard.edu/files/Stewart%20Final.pdf.

17. Prototype Carbon Fund, supra note 6.

18 . GLOBAL ENV’T FACILITY (GEF), ADDING VALUE AND PROMOTING HIGHER IMPACT

THROUGH THE GEF’S PROGRAMMATIC APPROACH5(2009),

C. Design Elements and Guiding Principles of Financial Mechanisms for

Climate Change with Particular Focus on Governance Structure

Based on the foregoing definition of financial mechanisms for climate change, as well as drawing on relevant research work relating to climate change financial mechanisms,19 a financial mechanism for climate change should comprise the following three key elements: resource mobilization (generation), resource disbursement (delivery), and governance of institutional arrangements (administration). The guiding principles in each element will be briefly introduced below.

1. Generation: Resource Mobilization

This element refers to how the resources/funding of a financial mechanism are generated. As indicated in the previous section, sources of funding may be derived broadly from both the public and private sectors. According to Article 4.3 of the UNFCCC and paragraph 1(e) of the Bali Action Plan adopted at the COP 13, five principles are crucial for resources mobilization: adequacy, predictability, sustainability, equity and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, and measurability.20

These five guiding principles are equally important when designing the methods by which resources are to be generated under a financial mechanism for climate change. However, the importance and role of each of these guiding principles will differ depending on a given mechanism’s timeframe, sources of funding, and objective and purpose. For example, if the source of funding comes from the ODA through a governments’ annual budget, the principles of measurability and predictability will both be satisfied for the particular year of that budget’s approval. But from a long-term perspective, such a source of funding might be incompatible with these same two principles because each government’s annual budget is hard to predict. Furthermore, Article 4.3 of the UNFCCC requests that the Annex II Parties provide “new and additional” financial resources, which means that an Annex II Party cannot rely on its existing ODA to meet this financial obligation under the UNFCCC. On the other hand, when the source of funding comes from the private sector, as in the case of private investment,

19. E.g., Neil Bird & Jessica Brown, International Climate Finance: Principles for European

Support to Developing Countries (Eur. Dev. Co-operation to 2020 (EDC 2020), Working Paper No.6,

2010), available at

http://www.edc2020.eu/fileadmin/publications/EDC_2020_Working_Paper_No_6.pdf; CHARLIE PARKER ET AL.,THE LITTLE CLIMATE FINANCE BOOK:AGUIDE TO FINANCING OPTIONS FOR FORESTS AND

CLIMATE CHANGE (2009).

such funding might be more “adequate.” Nevertheless, it might also be more difficult to achieve measurability and predictability, since the availability of such types of funding depends largely upon the willingness and capacity of private investors to provide the necessary resources.

2. Delivery: Resources Distribution

Resources distribution refers to the ways in which the resources of financial mechanisms are delivered. First, it may refer to modes of distribution. Funds can be delivered through grants, concessional loans, or an investment channel such as a CDM project. Second, it may refer to the types of activities that the resources will fund, that is, projects or programs/policies. Third, it may also refer to the channel through which funding reaches its target recipients. Here the recipients can have direct access to the fund, or may have to apply for the use of funds via an appropriation or review mechanism. According to Article 11 of the UNFCCC, paragraph 1(e) of the Bali Action Plan, and the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, the following five principles are crucial in the delivery of resources: effectiveness, efficiency, equity, appropriateness, 21 and, national ownership.22

These five guiding principles are equally important when designing the distribution channel of resources for a financial mechanism for climate change. However, the importance and role of each of these guiding principles will vary depending on the given modes of resource disbursement, funding activities, and channels of disbursement. For example, when funding is provided in the form of a loan to support certain types of programs or policies, conditions might be imposed to ensure that the recipient country can use such funding effectively. This is, however, very likely to run counter to the principle of national ownership. When the resources come from a private sector source that wants to deliver the funding in the most effective and efficient manner, the funding might be directed specifically toward one particular type of activity, a particular sector, or even toward a particular region or country. Under these circumstances, the principle of equity might be compromised.23

21. Id. at 84.

22. National ownership refers to the extent to which recipients exercise leadership over their climate change policies and strategies. See Bird & Brown, supra note 19, at 9.

23. The uneven distribution of the current CDM projects is one such example. More than 70% of the registered CDM projects are in only three countries, China, India and Brazil. China alone has attracted more than 40% of the CDM projects.

3. Administration: Governance of Institutional Arrangement

The governance structure of a financial mechanism is crucial to ensuring that the generation and delivery of resources can be designed and implemented in accordance with the aforementioned guiding principles. It is thus not surprising that most of the research on climate change financial mechanisms focuses on institutional arrangement and governance. The legitimacy of a financial mechanism from the perspective of its governance has been analyzed in three dimensions: power, responsibility, and accountability.24 Power is “the capacity to determine outcomes. Power is distributed both formally and informally among Parties, and between Parties and the institutions they create.”25 This includes decisions regarding membership, decision-making rules, governing bodies, and administrative and management staff.26 Responsibility refers to “the exercise of power for its intended purposes, specifically, to ensure that resources entrusted to a financial mechanism are programmed effectively and equitably.”27 This includes responsibility exercised in allocating resources and in leading the design and implementation of projects and programs, as well as ensuring country ownership in the host country.28 Accountability refers to “the standards and systems for ensuring that power is exercised responsibly.”29 This is the key element in gauging the degree of legitimacy in a financial mechanism. Institutions entrusted with climate finance must be accountable both to contributors and recipients. Accountability begins with a determination of an institution’s precise goals and objectives, as well as agreement on measurable indicators of successful performance. It also includes fiduciary standards, the specific duties attributable to the trustee of a trust fund holding money for the beneficiary of that fund. Furthermore, environmental and social risks and impacts of projects and programs supported by the financial mechanism must also be managed responsibly.30

Four guiding principles are crucial for a governance structure according to Article 7 of the UNFCCC. These are transparency, efficiency, effectiveness, and balanced representation of all parties.31 These principles determine whether financial mechanisms are perceived as legitimate and impartial, and are equally important when designing the governance structure of a financial mechanism for climate change. Depending on the

24. BALLESTEROS ET AL., supra note 7, at 4-6. 25. Id. at 4. 26. Id. 27. Id. 28. Id. at 4-5. 29. Id. at 4. 30. Id. at 43-48.

scale of the financial mechanism (international, regional, bilateral, or unilateral) as well as the type of activity supported (projects, programs and policies, or investment), there can be a variety of institutional arrangements. Thus, the importance and roles of each of these guiding principles varies. For example, for a financial mechanism operating at the international level, such as the GEF, the principle of balanced representation of all parties plays a bigger role in the design of the governance structure. The principle of efficiency might be compromised, however, should such a financial mechanism adopt a large decision-making body or a complex decision-making mechanism in order to balance representation of all parties. Similarly, in the case of the Prototype Carbon Fund where the World Bank as trustee bears fiduciary duty toward all investors, transparency of the governance structure might come second to the principles of effectiveness and efficiency.

As shown in this Part, financial mechanisms for climate change can take a variety of forms. In addition, each of the three design features of a financial mechanism for climate change, i.e. generation, delivery, and administration, possesses its own set of guiding principles. The effectiveness of a mechanism in achieving its objectives depends mostly on whether its governance structure entails a democratic process for producing fair and equitable resources generation and allocation. Some of the financial mechanisms for climate change, such as the GEF, have already adopted a novel governance structure different from the traditional international financial mechanisms for development assistance, which began their operations in the 1940s. After more than five decades of calls for reform, the leading international financial mechanism for development assistance, the IMF, finally began governance reform in 2008. It is too soon to evaluate whether these reforms will be effective in addressing all of the concerns behind the calls for reform, as the reform process is still underway. Nevertheless, there might be valuable lessons to be learned from this process with the potential to guide many of the emerging financial mechanisms for climate change that are still “under construction.” The next Part will discuss the IMF’s experience with governance reform and the lessons learned.

III.GOVERNANCE REFORM OF THE IMF AND LESSONS LEARNED A. What Needs to be Reformed

The governance structures of the IMF, and in particular the weighted voting system, have been heavily criticised since the 1970s. Since that time, developing countries have campaigned rigorously for a new international economic order within the UN system, and called for reforms of the

governance structure of international economic organisations. 32 This imbalanced governance structure has been called the “legitimacy deficit” or “democratic deficit” of the IMF that, in term, undermined the legitimacy and efficiency of the Fund.33 These early and repeated calls for reform were only taken up by the members after over thirty years, when in early 2000, the IMF finally began a series of reform programs targeting its governance structure. Comprehensive reform of IMF governance encompasses issues relating to quotas, ministerial engagement and oversight, the size and composition of the Executive Board, voting rules, management selection, and staff diversity.34 The most criticized aspects of the Fund’s governance were its decision-making rules, and in particular with regard to how votes were distributed (the “quota” system), the voting rules, and its organizational arrangement, in particular the role of the Executive Directors.

1. Decision-Making

According to Article XII, Section 5(a) of the Articles of Agreement of the IMF (hereinafter IMF Agreement), each member has 250 votes “plus one additional vote for each part of its quota equivalent to one hundred thousand special drawing rights.” The 250 votes number represents the basic votes of each IMF member. According to J. Gold, the basic votes were designed in recognition of the doctrine of the equality of states, as well as to avoid too close an adherence to the concept of a private business corporation. Furthermore, some members might have otherwise had such a small quota that they would possess virtually no sense of participation in the affairs of the Fund.35 The basic votes accounted for 11.26% of the total votes in 1994 when the IMF was created. However, the IMF Agreement does not specify the ratio of basic votes to total votes. As a result, the proportion of basic votes to total votes has decreased significantly over the last five decades as the membership of the IMF expanded and increases to the regular quota continued since 1965. The basic votes accounted for only 2% of total votes in 2005.36 This erosion of basic votes means that members with small quotas

32. Developing countries have tried to push through a series of declarations/resolutions under the UN Assembly to achieve this goal. Two such examples are the “Programme of Action on the Establishment of a New International Economic Order” adopted by the UN Assembly in 1974, and the “Charter of Economic Rights and Duties of States” adopted in 1975.

33. Hector R. Torres, Reforming the International Monetary Fund-Why its legitimacy is at stake, 10 J.INT’L ECON.L. 443, 445 & n.9 (2007).

34 . IMF, EXECUTIVE BOARD PROGRESS REPORT TO THE IMFC: THE REFORM OF FUND GOVERNANCE, para. 1 (April 21, 2010), http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2010/042110a.pdf.

35. JOSEPH GOLD, VOTING AND DECISIONS IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND:AN

ESSAY ON THE LAW AND PRACTICE OF THE FUND 18-19(1972).

36. Vijay L. Kelkar et al., Reforming the International Monetary Fund: Towards Enhanced

wield decreasing influence over the Fund’s decision-making process, which undoubtedly raises controversy over the legitimacy of the Fund’s decisions.

In addition to basic votes, the quota system raises more concerns within the reform agenda. As Article XII, Section 5 stipulates, the more quota a member is allocated, the more votes that member can have. According to Article III, Section 1, the quotas of the original members of the IMF are stipulated in Annex A. As for other members, the quotas shall be determined by the Board of Governors. The subscription of each member shall be equal to its quota and shall be paid in full to the Fund. Section 2 sets down rules for quota adjustment, including a regular five-year general review and an ad hoc review at the request of any member. An 85% majority of the total voting power is required for any change in quotas. The quota of an IMF member not only determines voting power, but also the extent to which the member can use the resources of the Fund without any conditions, as well as how many special drawing rights (SDRs) can be allocated to it. In other words, a quota determines the rights and obligations of an IMF member. Quotas are designed to represent the relative economic power of each member globally, so the quota formula should reflect the economic status of each member. However, the initial quota formula was designed with a political objective, that is, to give the U.S. the highest quota share.37 This so-called Bretton Woods formula has been revised several times, but only with minor changes, and has remained unchanged since 1983.38 Both developing and developed members have raised the criticism that this quota formula no longer reflects the real economic power and status of members globally. The revision of the quota formula is, thus, called for in the reform program.

Voting rules are another contentious issue within the reform program. According to Article XII, Section 5(c) of the IMF Agreement, “Except as otherwise specifically provided, all decisions of the Fund shall be made by a majority of the votes cast.” “Otherwise specifically provided” is understood to refer to those provisions of the IMF Agreement that require special majorities for certain decisions. There are two types of special majorities (70% and 85%), and both are calculated in terms of the total voting power within the Fund.39 Another type of special majorities rule is the double-majority rule that applies to only one type of decisions of the Fund,

BANK 45, 62 (Ariel Buira ed., 2005).

37. See Raymond F. Mikesell, The Bretton Woods Debates: A Memoir, 192 ESSAYS IN INT’L FIN. 22 (1994).

38. Abbas Mirakhor & Iqbal M. Zaidi, Rethinking the Governance of the International Monetary

Fund 8-9 (IMF WP/06/273, 2006), available at

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=956736.

39. Francois Gianviti, Decision-Making in the International Monetary Fund, in 1 CURRENT

i.e. amendments to the IMF Agreement. According to Article XXVIII, an amendment to the IMF Agreement requires the acceptance of three fifths of the members, having 85% of the total voting power. An abstention or a vote not cast has the same effect as a negative vote.40 The types of decisions requiring special majorities have increased significantly since the Second Amendment to the IMF Agreement,41 resulting in greater veto power afforded to those Members holding, collectively or individually, 25% or 15% of the total voting power. For example, with 17.023% of the total voting power,42 the U.S. alone holds the power to veto any type of decision that requires an 85% majority. Despite the existence of these formal voting rules in the IMF Agreement, decisions within the IMF are often adopted by consensus without formal votes. According to Rule C-10 of the Rules and Regulations, the Chairman shall “ordinarily ascertain the sense of the meeting in lieu of a formal vote,” unless a member of the Executive Board requests one. “Sense of the meeting” is defined in Rule C-10 as “a position supported by executive directors having sufficient votes to carry the question if a vote were taken.”43 It has been observed that: “…when there is no explicit decision to be taken, and a range of views have been expressed on a particular issue, the Chair has significant discretion as to how to interpret the silence of an executive director.”44 Formal votes are rare in meetings of the Executive Board. However, “the formal procedures may profoundly affect the de facto decision-making process.”45 Even where decisions are often taken informally, the resort to formal voting procedures remains a possibility and may have a significant effect on the willingness of members to arrive at a consensus. Consequently, the voting rules, coupled with the imbalance of votes (both the basic votes and the weighted votes based on quotas), represent another aspect of IMF decision-making that requires reform.

2. Organisational Arrangement

According to Article XII, Section 1 of the IMF Agreement, the IMF

40. Alexander Mountford, The Formal Governance Structure of the International Monetary Fund 19 (Int’l Indep. Evaluation Org., BP/08/01, 2008),

http://www.ieo-imf.org/ieo/files/completedevaluations/05212008BP08_01.pdf.

41. Leo Van Houtven,GOVERNANCE OF THE IMF:DECISION-MAKING,INSTITUTIONAL OVERSIGHT, TRANSPARENCY, AND ACCOUNTABILITY, at 73 (IMF Pamphlet Ser. No. 53, 2002).

42. This is the U.S. quota before 2006.

43. This is also the observation from an Alternate Executive Director of the IMF. Torres, supra note 33, at 446.

44. Jeff Chelsky, Summarizing the Views of the IMF Executive Board 8 (Int’l Indep. Evaluation Org., BP/08/05, 2008), available at

http://www.ieo-imf.org/ieo/files/completedevaluations/052108CG_background6.pdf.

45. Stephen Zamora, Voting in International Economic Organizations, 74 AM.J.INT’L.L. 566, 568 (1980).

shall have a Board of Governors, an Executive Board, a Managing Director, and a staff, as well as a Council if the Board of Governors so decides by an 85% majority. In addition to these formal governing bodies, the Board of Governors can also set up various committees for specific tasks or advisory purposes, such as the Interim Committee (set up in 1974 and renamed the International Monetary and Financial Committee in 1999). Other informal alliances, such as G-7, G-20 or G-24, formed by different IMF members also interact with the IMF. The IMF’s governance is illustrated in the following chart.

Organs set up under the IMF Agreement Alliances outside the IMF’s institutional structure Formal linkages/relationship under the IMF Agreement Informal relationship

Adapted from: http://www.imf.org/external/about/govstruct.htm

Board of Governors IMFC Executive Board Managing Director Staff G-7, G-20, G-24…

According to Article XII, Section 2(a), all power under the IMF Agreement not conferred directly to the Board of Governors, the Executive Board, or the Managing Director shall be vested in the Board of Governors. Although the Board of Governors is the IMF’s highest decision-making organ, since 1946 most of its power has been delegated to the Executive Board.46 As a result, the Executive Board is the most important organ in the daily operations and decisions of the Fund, and has been the center of focus in the call for governance reform.

According to Article XII, Section 3(a), the Executive Board is responsible for conducting the business of the Fund, and for this purpose, it shall exercise all the powers delegated to it by the Board of Governors. The Executive Board consists of Executive Directors with a Managing Director as the chairman of the Executive Board. Five of the Executive Directors shall be appointed by the five members having the largest quotas (appointed Directors), and another fifteen shall be elected by the other members (elected Directors). The number of elected Directors can be changed by the Board of Governors using an 85% majority of total voting power. The Executive Board shall function in continuous session at the principal office of the Fund, i.e. its Headquarters in Washington, D.C. Regarding voting, appointed Directors are to cast the number of votes allotted to the member appointing him or her, whilst the elected Directors cast the number of votes which counted toward his or her election. In other words, split voting is not permitted for elected Directors. Two major reform issues relating to the Executive Board are the electoral system and the role of the Executive Directors under the IMF.

Currently there are twenty-four Executive Directors, including five appointed ones (the U.S., Japan, Germany, France, and the UK) and nineteen elected. Elected Directors serve a two-year term. Since three elected Directors come from constituencies that have only one member (China, Saudi Arabia,47 and Russia), only sixteen elected Directors come from multi-member constituencies. While there are three elected Directors coming from constituencies consisting of only one member, two Directors elected by most of the African members come from constituencies of twenty-one and twenty-four members, respectively.48 Because not all members have an appointed Director representing them at the meeting of the Executive Board, Article XII, Section 3(j) provides that when a member is not entitled to appoint an Executive Director, that member can send a representative to attend any meeting of the Executive Board when a request is made by the

46. Mountford, supra note 40, at 7.

47. According to art. XII, § 3(c), Saudi Arabia became entitle to appoint its own Director in 1978 when its currency became widely used by the members.

member or a matter particularly affecting that member is under consideration.

The IMF Agreement does not specify how the constituencies are formed. Thus, a constituency may be based on an informal arrangement or a written agreement among participating members.49 However, as the IMF Agreement does not contain specific rules on constituencies, the legal effect or status of these informal arrangements or written agreement amongst members remain questionable and uncertain. There are diverging views regarding the role of mixed multi-country constituencies, as well as the related issue of whether constituencies containing a dominant country allow for proper representation of small countries.50 The Executive Board began as a compact body in 1945 where multi-country constituencies represented, on average, around 5.6 members. As the Fund membership expanded, the average size of a multi-country constituency grew to the 10.8 members of today. When the single-country constituencies increases from five to eight, accounting for a third of the Board’s seats, crowded constituencies became even more apparent.51 Controversies have arisen over how best to ensure that elected Directors from constituencies of members with divergent interests (for example, a creditor member vis-à-vis a member using the Fund’s resources) reflect the positions of all the constituent members.

Directors representing an individual member can be held directly accountable by their authorities and in effect dismissed and replaced at will. An elected Director, on the other hand, serves a fixed two-year term once elected, which might give him or her little incentive to be accountable to his or her constituency.52 In fact, when members in a constituency select a Director, he or she is not obligated to defer to the views of those members or to cast his or her votes in accordance with their instructions. His or her votes are valid even if they are inconsistent with any instructions he or she may have received from the members in the constituency.53

Another criticism related to the electoral system is that, two multi-country constituencies representing African countries, with twenty-one and twenty-four members respectively, are too large. In contrast, the average size of multi-country constituencies is eleven members. This increases the

49. Murilo Portugal, Improving IMF Governance and Increasing the Influence of Developing

Countries in IMF Decision-making, in REFORMING THE GOVERNANCE OF THE IMF AND THE WORLD

BANK 75, 94 (Ariel Buira ed., 2005). 50. Id. at 95.

51 . Leonardo Martinez-Diaz, Executive Boards in International Organizations: Lessons for Strengthening IMF Governance 18-19 (Int’l Indep. Evaluation Org., BP/08/08, 2008), available at

http://www.ieo-imf.org/ieo/files/completedevaluations/05212008BP08_08.pdf.

52. Ngaire Woods & Domenico Lombardi, Uneven Patterns of Governance: How Developing

Countries Are Represented in the IMF, 13 REV. OF INT’L POL.ECON. 480, 492 (2006). 53. Gianviti, supra note 39, at 48.

burden of these two Directors, especially considering that they represent members that usually engage in long-term borrowing, which is quite demanding in terms of workload.54

As has been stated previously, the Board of Governors has delegated most of its powers to the Executive Directors. Therefore, the Executive Directors possess great power, with duties including approval of relevant policies of the Fund, discussion of bilateral surveillance under Article IV, as well as multilateral surveillance of the international monetary system, approval of all decisions relating to the use of Fund’s resources, approval of the selection of the Managing Director, approval of the IMF budget and personnel, etc. In other words, the Executive Directors carry out most, if not all of the important day-to-day operational decisions of the Fund.

The second reform issue relating to the Executive Board concerns the role and character of the Executive Directors. Are they officials of the IMF or representatives of member governments? This is a crucial question since the way in which it is answered determines to whom the Executive Directors should be held accountable. During the drafting of the IMF Agreement, the UK was primarily of the view that Executive Directors are international officials. The U.S., however, preferred to grant more political power to the Executive Directors. The U.S. view seemed to have prevailed, as the result was a resident, twelve-member board based at the IMF Headquarters that meets in continuous sessions.55 Nevertheless, the IMF Agreement does not specify whether the Executive Directors should be fully or partially accountable to their appointed or elected members.

After analysing the functions and duties of the Executive Directors, Grancois Gianviti, the former General Counsel of the IMF, concludes that “an Executive Director of the IMF is an official of the organisation, legally accountable to the IMF for the discharge of his duties.”56 Yet, appointed Directors can be recalled at will by their capitals. And in the case of both appointed and elected Directors, the potential impact of their voting behavior on their future careers in their home countries provides an incentive to listen to their authorities’ guidance.57 It is, thus, impossible that Executive Directors should ignore instructions or guidance from members and act as independent officials of the IMF. As a result, the character of the Executive Directors remains controversial. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that the Executive Board itself lacks any process of self-evaluation. Furthermore,

54. Portugal, supra note 49, at 96. 55. Martinez-Diaz, supra note 51, at 15-16. 56. Gianviti, supra note 39, at 45-48.

57. Indep. Evaluation Office,GOVERNANCE OF THE IMF:AN EVALUATION 16 (2008), available

its performance is not evaluated by any other body, meaning that it is only subject to members’ evaluation of the performance of the Directors that represent them.58

B. The Reform Program

Calls for reform did not stop after the 1970s. In 1983, the Group of Twenty-Four, composed of representatives of developing countries, issued a communiqué stating that the “Ministers…underscored the fact that current monetary and financial system suffers from many shortcomings and inequities, notably, the inadequate share of developing countries in decision-making….”59 The “International Conference on Financing for Development” convened by the UN in March 2002 adopted the Monterrey Consensus regarding development finance. The delegates to this conference stressed “the need to broaden and strengthen the participation of developing countries and countries with economies in transition in international economic decision-making and norm-setting,” and encouraged the IMF and World Bank to “enhance the effective participation of developing countries and countries with economies in transition in international dialogues and decision-making.”60 In the spring of 2003, the Development Committee repeated this recommendation. Still, no action had been taken to reform the allocation of voting power within both the IMF and the World Bank by the fall of 2004. In October 2004, the Ministers of the G24 declared that “enhancing the representation of developing countries requires a new quota formula to reflect the relative size of developing countries’ economies.” The Chair of the Deputies of G24 also asked that the G24 Secretariat focus its research efforts over the coming months on governance issues.61 These are the background events leading up to the series of reform programs finally taken up by the IMF starting in 2006. These will be briefly discussed below. The IMF governance reform kicked off in 2006 when the Executive Board recommended a package of reforms related to quotas and voice to the Board of Governors.62 This recommendation was adopted by the Board of Governors on September 18, 2006. Members representing 90.6% of total

58. Martinez-Diaz, supra note 51, at 20.

59. Joseph Gold, Public International Law in the International Monetary System, 38 SW.L.J. 799, 835 (1984).

60. International Conference on Financing for Development, Monterrey, Mexico, March 18-22, 2002, Monterrey Consensus of the International Conference on Financing for Development, ¶¶

62-63, U.N. Doc. A/CONF.198/11 (2003).

61. Gil S. Beltran, Governance in Bretton Woods Institutions 3-4, Paper presented at XX G24 Technical Group Meeting (Mar. 17-18, 2005), http://www.g24.org/ResearchPaps/GBeltran.pdf. 62. Press Release, IMF, IMF Executive Board Recommends Quota and Related Governance Reforms, IMF Press Release No. 06/189 (Sept. 1, 2006).

voting power voted in favor of Resolution 61-5,63 Resolution on Quota and Voice Reform (also called the Singapore Resolution).64 The reform program was designed to be an integrated two-year program including several changes.65 First, ad hoc quota increases for some of the most clearly underrepresented countries, namely China, South Korea, Mexico, and Turkey. These increases represented 1.8% of the total quota. Second, the Executive Board was asked to reach agreement on a new quota formula by 2007. The formula was to provide a simpler and more transparent means of capturing members’ relative positions in the world economy. Third, the Executive Board was also requested to propose an amendment to the IMF Agreement to provide for at least a doubling of the basic votes that each member possesses. This again was to ensure an adequate voice for low-income countries. In addition, the amendment was to also safeguard the proportion of basic votes in total voting power. Fourth, the Resolution called on the Executive Board to act expeditiously to increase the staffing resources available to those Executive Directors elected by a large number of mostly African members whose workload was particularly heavy. Furthermore, the Executive Board was to consider the merits of another amendment that would enable Executive Directors to appoint more than one Alternate Executive Director.

The first reform agenda could be implemented immediately as long as the four members that receive the ad hoc quota increases completed the legal requirement in Article III, Section 2(d) of the IMF Agreement. As for the third part of the reform agenda, the Executive Board approved an increase in staffing resources for the two African Executive Directors’ offices through the allocation of an additional advisor position in May 2007.66 The Executive Directors were requested to address all the other reform issues as a package deal by 2008.

After starting the first step of reform in Singapore, the Executive Board continued to implement the reform program as instructed by the Board of Governors. It should be noted that at the IMFC Meeting in September 2006, the U.S. announced that it would not request an increase in its voting share even if it is entitled to under the new quota formula. The U.S. also urged other industrial members to follow suit.67 The Executive Directors adopted

63. Press Release, IMF, IMF Board of Governors Approves Quota and Related Governance Reforms, IMF Press Release No. 06/205 (Sept. 18, 2006).

64. The text of Resolution 61-5 can be found in: Legal Dep’t & Quota & Voice Working Grp.,

Proposed Amendment of the Articles of Agreement Regarding Basic Votes-Preliminary Considerations,

app. I (Dec. 22, 2006).

65. IMF, supra note 62; IMF, supra note 63.

66. IMF, REFORM OF QUOTA AND VOICE IN THE INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND—REPORT OF THE EXECUTIVE BOARD TO THE BOARD OF GOVERNORS 6 n.5 (Mar. 28, 2008), http://www.imf.org/external/np/pp/eng/2008/032108.pdf.

the reform package on quota and voice and recommended the program to the Board of Governors on March 28, 2008.68 On April 28, 2008, the Board of Governors, with 175 members representing 92.93% of total voting power voted for the package, adopted Resolution 63-2, Resolution on Reform of Quota and Voice in the International Monetary Fund.69 As the 2008 reform program required an amendment to the IMF Agreement, a double-majority was needed. That is, it requires the approval of three fifths of the members representing 85% of the total voting power. After almost three years, the 2008 reform package finally came into force on March 3, 2011 after 117 members representing more than 85% of total voting power had accepted the amendment proposal.

The 2008 reforms included the following main elements.70 First, a new quota formula was adopted, and the second round of ad hoc quota increases was set to be allocated on the basis that members underrepresented under the new quota formula would be eligible for increases. This second round of ad hoc quota increases was to account for approximately 9.55% of the total quota in order to enhance representation for dynamic economies. Several underrepresented industrial members (Germany, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Luxembourg, and the U.S.) agreed to forgo part of the quota increase for which they were eligible. Furthermore, underrepresented emerging markets and developing economies, whose combined share in global PPP GDP was over 75% greater than their actual pre-Singapore quota share, could receive a minimum nominal quota increase of 40% over their pre-Singapore levels. In addition, because the four members that received quota increases in the first round of ad hoc increases in 2006 remain substantially underrepresented, they will receive a minimum nominal second round increase of 15%.

Second, the Resolution approved the proposed amendment to the IMF Agreement to triple the number of basic votes—the first such increase since the establishment of the Fund in 1944. The amended Article XII, Section 5(a)(i) provides that “the basic votes of each member shall be the number of votes that results from the equal distribution among all the members of 5.502 percent of the aggregate sum of the total voting power of all the members, provided that there shall be no fractional basic votes.” This was the first time that basic votes would be determined by a fixed proportion to the total votes, so that basic votes for members receiving fewer quotas would not have their basic votes “diluted” in the future round of regular or ad hoc quota increases.

Reform, POL’Y BRIEFS INT’L ECON., Feb. 2007, at 7, 10.

68. Press Release, IMF, IMF Executive Board Recommends Reforms to Overhaul Quota and Voice, IMF Press Release No. 08/64 (Mar. 28, 2008).

69. Press Release, IMF, IMF Board of Governors Adopts Quota and Voice Reforms by Large Margin, IMF Press Release No. 08/93 (Apr. 29, 2008).

Third, the Resolution recommended that Executive Directors representing constituencies with more than nineteen members be entitled to appoint another Alternative Director in addition to the single position granted to all Executive Directors. This would enhance the capacity of the two Executive Directors’ offices representing African constituencies. In sum, fifty-four members will see their quota shares increase from pre-Singapore levels by between 12 and 106%.71 The aggregate shift in quota shares for these fifty-four members amounts to 4.9 percentage points. If the increase in basic votes is included, a total of 135 members have seen their voting shares increase. Although these 2008 reforms have provided for a fixed proportion of basic votes to the total voting power, that percentage is less than 6%, far below the 11.26% when the IMF was established in 1944.72

The communiqué of the IMFC issued on October 4, 2009 states that the IMF is and should remain a quota-based institution. It also emphasized that quota reform is crucial for increasing the legitimacy and effectiveness of the Fund, and expressed support for a transfer in quota share of at least 5% from over-represented countries to under-represented developing countries and dynamic emerging markets.73

Accordingly, the Executive Directors adopted a third reform program on quotas and governance on November 5, 2010, and recommended it to the Board of Governors.74 Governors representing 95.32% of total voting power voted in favor of this recommendation, adopting the Resolution on Quota and Reform of the Executive Board on December 16, 2010.75 Under this 2010 reform program, the 14th General Review of Quotas was proposed with an unprecedented doubling of quotas and a major realignment of quota shares among members. This will result in a shift of more than 6% of quota shares to dynamic emerging markets and developing countries, as well as more than 6% from over-represented to under-represented members.76 Half of this is to be transferred from advanced economies, and one third comes from oil producers. 110 of the current 185 members, including 102 emerging

71. For example, Korea will see its quota increase by 106%, Singapore by 63%, Turkey by 51%, China by 50%, and India, Brazil and Mexico all by 40%. See IMF Staff, Reform of IMF Quotas and

Voice: Responding to Changes in the Global Economy, IMF (Apr., 2008),

http://www.imf.org/external/np/exr/ib/2008/040108.htm.

72. For example, G4 has suggested that the percentage of basic votes to the total voting power should be fixed at the level of 1944 when the IMF was established. Beltran, supra note 61, at 21. 73. Press Release, IMF, Communiqué of the International Monetary and Financial Committee of the Board of Governors of the International Monetary Fund, IMF Press Release No. 09/347 (Oct. 4, 2009).

74. Press Release, IMF, IMF Executive Board Approves Major Overhaul of Quotas and Governance, IMF Press Release No. 10/418 (Nov. 5, 2010).

75. Press Release, IMF, IMF Board of Governors Approves Major Quota and Governance Reforms, IMF Press Release No. 10/477 (Dec. 16, 2010).

or developing members, will see their quota share increased or maintained.77 The changes will also protect the quota shares and voting power of the poorest members, that is members eligible to borrow from the low-income Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust. Members whose per capita income falls below the IDA threshold (US$1,135 in 2008) will have their voting shares preserved.78 Furthermore, the Board also agreed that a new quota formula should be decided on by January 2013, and that the next quota review should be completed by January 2014, two years ahead of schedule.79 In addition to these reforms to the quota system, the 2010 reform program also proposed another amendment to the IMF Agreement in order to change the system of Executive Directors. The number of Executive Directors will remain at the current twenty-four, but the Executive Directors will consist only of elected Executive Directors, doing away with the category of appointed Directors. This means that there will be further leeway for appointing second Alternate Executive Directors to enhance the representation of multi-country constituencies.80 These reforms to the system of Executive Directors were made possible when the EU agreed to give up two seats.81 Furthermore, the composition of the Board will be reviewed every eight years, starting when the quota reform takes effect.82

For this third reform package to take effect, two procedures must be completed. First, the amendment to the IMF Agreement regarding the composition of the Executive Directors must be accepted by at least three fifths of the members, representing 85% of total voting power. Second, the 14th general quota review must be accepted by members representing at least 70% of the total quota number on November 5, 2010 with members giving their consent in writing to their quota increases.83 When both the 2008 and 2010 reform packages take effect, the top ten shareholders of the IMF will represent the top ten countries in the world, namely the U.S., Japan, the four main European countries, and the four BRICs—Brazil, Russia, India, and China.84

77. IMFSurvey Online, IMF Board Approves Far-reaching Governance Reforms, IMF (Nov. 5, 2010), http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2010/new110510b.htm.

78. IMF, supra note 74.

79. IMF Survey Online, supra note 77. 80. IMF, supra note 74.

81. IMFSurvey Online, Important Milestone Reached to Reinforce IMF Legitimacy, IMF (Mar. 3, 2011), http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/survey/so/2011/new030411a.htm.

82. IMF Survey Online, supra note 77.

83. IMF Quota and Governance Publications: June 2006-March 2011, IMF (Sept. 30, 2011), http://www.imf.org/external/np/fin/quotas/pubs/index.htm.

IV.LESSONS LEARNED A. A Note of Caution

Before analyzing the ways in which the IMF’s experience with governance reform may offer lessons for financial mechanisms for climate change, it must be noted that these two types of financial mechanisms differ in many ways. These differences might render some of the IMF’s reform experiences inapplicable or inappropriate to the case of climate change financial mechanisms.

First, the IMF is an international organization possessing a full juridical personality, as stated in Article IX, Sec 1 of the IMF Agreement. Financial mechanisms for climate change, on the other hand, exhibit very diverse organizational structures and legal forms, ranging from a trust fund-type to a full-scale organization such as the GEF. Second, the IMF has full capacity to make its own policies and decisions regarding, for example, how members can use its resources. Financial mechanisms, especially those under the international climate change regime, have to “function under the guidance of and be accountable to” the COP. Third, the IMF operates at the international level, while many of the climate change financial mechanisms operate at the regional or even domestic level. Fourth, the IMF only supports programs and not projects, while most, if not all of the climate change financial mechanisms support mainly project activities and only a few (the GEF, for example) support program and policies, and then only recently. Fifth, as an international organization, the IMF’s membership is only open to sovereign states. Some of the climate change financial mechanisms, for example, most of the carbon funds administered by the World Bank, permit private sectors and non-governmental entities to take part. Finally, in terms of resource mobilization, the IMF draws all of its resources from the public sector, i.e. the paid-in subscriptions of its members. The climate change financial mechanisms, on the other hand, rely on a variety of channels to generate resources.

Despite these differences, the IMF and climate change financial mechanisms both serve as funding channels to support activities for specific purposes. In addition, they both possess a set of institutional arrangements through which standards and procedures are laid out on how to generate and deliver resources. Moreover, whether the mechanism itself can be perceived as legitimate and effective is determined, to a large extent, on how the governance structure is arranged. In terms of governance structure, then, the aforementioned differences between the IMF and the climate change financial mechanisms are not as stark as they first appear.

B. Lessons Learned

Interestingly, the current governance structure of one of the climate change financial mechanisms, the GEF, was designed with the aim of reforming its governance structure when the GEF pilot phase (GEF-P) was operated by the World Bank in 1991. As mentioned in Part III, developing countries have long felt dissatisfied with the governance structure of the two Bretton Woods institutions. When the UNFCCC was negotiated from 1990 to 1992, developed countries would have preferred to designate the GEF-P as the Convention’s financial mechanism. Notably, this ran into strong opposition from developing countries because of the close relationship between the GEF-P and the World Bank. As a result, the GEF-P was restructured between 1992 and 1994, with clear instructions from the UNFCCC that its financial mechanism should have in mind “an equitable and balance[d] representation of all Parties within a transparent system of governance.”85 The decision-making mechanism of the GEF does not make use of IMF quota-type weighted votes, and adopts a novel set of double-majority voting rules in the Council where decisions need to be approved by both a 60% majority of the total member participants and a 60% majority of the total contributions. This organizational arrangement also establishes a more balanced structure that may represent the interests of both donor and recipient participants. The Council, very similar to the Board of Executive Directors of the IMF in terms of its functions, consists also of constituency groupings, sixteen of which are from developing countries, fourteen of which are from developed countries, and two of which are from countries in Central and Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union.86

While calling for reform, some commentators have prevailed upon the IMF to adopt a set of GEF-like double majority voting rules so that decisions may better represent the interests of both donor and recipient members.87 But reform programs have not taken up this proposal. Among the proposed reforms discussed in Part II.1, the distribution of votes, including basic votes and quotas, and the composition of the Executive Directors are most significant, with particular focus on the distribution of votes.

When the first step of the reform programme took place in 2006, there

85. For more on the GEF, see e.g., Stephen A. Silard, The Global Environment Facility: A new

development in international law and organization, 28 GEO.WASH.J.INT’L L.&ECON. 607 (1995); Jake Werksman, Consolidating Governance of the Global Commons: Insights from the Global

Environment Facility, 6 Y.B. INT’L ENVTL.L. 27 (1995).

86 . See GLOBAL ENV’T FACILITY, INSTRUMENT FOR THE ESTABLISHMENT OF THE

RESTRUCTURE GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY, ¶ 16 & Annex E (2004).

87. See e.g., Woods & Lombardi, supra note 52, at 495; United. Nation. Conference on the World Financial and Economic Crisis and Its Impact on Development, June 24-26, 2009, Report of the

Commission of Experts of the President of the United Nations General Assembly on Reforms of International Monetary and Financial System 42, 94 (Sept. 21, 2009).

were reservations from developing countries and commentators questioning whether such a reform could help to address the “legitimacy deficit” of the IMF.88 However, the reform programmes kept rolling after 2006. The latest reform programmes were only adopted in 2010 and several key reform agenda, especially those that involve the amendment of the IMF Agreement, still await further implementation. The overall evaluation of the whole reform programme, thus, cannot be undertaken at this moment. Nevertheless, from the process of observing the evolution of the reform programmes, it seems approriate to draw the following lessons.

First, as most, if not all criticism had to do with how votes were distributed. The mixture of basic votes and quotas is premised upon the notion that weighted votes exist to balance the principle of sovereign equality of states against the effective functioning of a financial institution. However, when the proportion of basic votes to the total voting power decreased, the principle of sovereign equality of states faltered. In addition, when quota formulas no longer reflected the real economic status of each member, the effectiveness of the institution also suffered. Both of these sites of discontent affected members’ perception of the IMF’s as a legitimate and effective body. This was a powerful driving force behind the determination to push for reform in the distribution and the design of votes.

These reforms to basic votes might be somehow disappointing, as the fixed proportion (5.502%) is less than half of the percentage when the IMF was established (11.26%). Nevertheless, the distribution of total voting power between advanced economies (donors) and emerging markets and developing countries (potential recipients) has improved. Before the 2006 reforms (pre-Singapore), the advanced economies possessed 60.6% of voting shares while emerging market and developing economies had only 39.4%, with Asian countries only accounting for 10.4%. When the 2010 reform program takes effect, this proportion will become 55.3% to 44.7%, with Asian countries possessing 16.1%. This illustrates that, even if a balanced representation of all individual members cannot be achieved, at least the distribution of power between donor members, as a group, and recipient members, as a group, must be maintained.

Second, as one commentator has noted, the proposal for quota reform within the IMF should follow three basic principles. First, reform must be simple and transparent. Second, creditors, as financial institution, need to have a decisive voice in policy-making so as to ensure that creditors remain confident in the institution’s lending decisions. Third, any proposed reform must not seek to remove the veto power of the largest individual creditor, the