Hopelessness and Loneliness Among Suicide

Attempters in School-Based Samples of

Taiwanese, Philippine and Thai Adolescents

RANDY M. PAGEa, JUN YANAGISHITAa, JIRAPORN SUWANTEERANGKULb, EMILIA PATRICIA ZARCOc,

CHING MEI-LEEdand NAE-FANG MIAOe

aDepartment of Health Science, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, USA, bDepartment of Community Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai,

Thailand, cDepartment of Health Education, Adelphi University, Garden City, NY, USA, dDepartment of Health

Education, National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan and eCollege of Nursing, Taipei Medical University,

Taipei, Taiwan

ABSTRACT The aim of this study was to assess the level of suicide attempts in three school-based samples of Southeast Asian adolescents (Taipei, Taiwan; the Philippines; Chiang Mai, Thailand) and deter-mine whether adolescent suicide attempters score higher on measures of hopelessness and loneliness relative to nonattempters. It was hypothesized that hopelessness and loneliness would be related to suicide attempts, and that hopelessness would continue to be asso-ciated with suicide attempts when controlling for loneliness. The prevalence of suicide attempts across the three samples of Asian youth were not consistent with Taiwanese girls and boys as the most likely to have ever attempted suicide. As expected, results showed that suicide attempters (in past 12 months and ever) scored higher on hopelessness and loneliness than nonattempters across all three samples and for both genders. However, the statistical control of loneliness demonstra-bly weakened the association between suicide attempt behaviour and hopelessness across the samples and for both genders, and resulted in nonsignificant ANCOVA tests for some of the sample-gender groups. Please address correspondence to: Randy M. Page, Brigham Young University, Department of Health Science, 221 Richards Building, Provo, Utah, USA 84602, USA. Email: randy_page@byu.edu

School Psychology International Copyright © 2006 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi), Vol. 27(5): 583–598.

These results attest to the need for more research investigating con-nections between youth suicide attempts, hopelessness and loneliness in adolescent populations. Loneliness should be included as a potential determinant of youth suicidal behaviour in future research.

KEY WORDS: adolescents; hopelessness; loneliness; Philippines; suicide; suicide attempts; Taiwan; Thailand

Suicide attempts represent a potentially lethal health event and a significant risk factor for completed suicide in the future (Borowsky et al., 2001; Committee on Adolescence, 2000). Suicide research on adolescent populations often includes the use of questionnaires in school-based samples to assess the self-report of suicide attempts (Evans et al., 2005). In 1997, Safer reported that data from 29 self-report questionnaire studies from nine countries showed a median of 7–10 percent of adolescent students acknowledge having made one or more suicide attempts. A review of 128 studies comprising over 530,000 adolescents showed that 9.7 percent of adolescents reported they had attempted suicide at some point in their lives (Evans et al., 2005). The National Youth Risk Behavior Survey of US students in grades 9 through 12 indicated that 5.4 percent of boys and 11.5 percent of girls had attempted suicide in the past 12 months (Grunbaum et al., 2004). Among Capetown, South African 11th graders, 6 percent of boys and 14 percent of girls reported attempting suicide in the past 12 months (Wild et al., 2004). A similar prevalence was also true for 6 percent of boys and 10.4 percent of girls in a nationally representative sample of Norwegian students in grades 7–12 (Wichstrom and Rossow, 2002). Higher rates were found among La Paz, Bolivia students with 26.9 percent of girls and 8.9 percent of boys reporting at least one suicide attempt in the past 12 months (Dearden et al., 2005). A study of Caribbean youth reported that 12.7 percent of 13–15 year-olds and 12.9 percent of 16–18 year-olds reported ever attempting suicide in their lifetime, with a slightly higher prevalence among girls than boys (Halcon et al., 2000).

The international literature also includes a few studies of Asian youth. A study of Hong Kong students revealed that 7.3 percent of boys and 7.2 percent of girls in the high school years had attempted suicide in the past 12 months (Yip et al., 2004). A similar rate was found among rural Chinese students (7.1 percent of boys, 7 percent of girls) (Liu et al., 2005). The rate of suicide attempts was lower in a study of Malaysian students (3.7 percent of boys, 5.3 percent of girls) and Korean students (3.4 percent of boys, 7.3 percent of girls), although the prevalence in the Korean study was based on the past two weeks rather than the past 12 months (Chen et al., 2005; Cho et al., 2002). A study of Bangkok, Thailand youth reported a prevalence of suicide attempt of

6.1 percent among students and that girls were more likely than boys to attempt suicide, but did not give the sex-specific percentages (Ruangkanchanasetr et al., 2005).

The predominance of studies investigating adolescent suicidal behaviour have been conducted with Western youth and what is known is primarily based upon white middle-class populations. Liu et al. (2005) point out that the risk factors of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts found in previous Western studies are multiple in origin, including biological, cognitive, psychological, social and family factors. Hopelessness and loneliness are cognitive variables that have also been found to be associated with increased risk for suicide, along with low self esteem, poor problem-solving skills and external locus of control (Gould et al., 2003; Stravynski and Boyer, 2001; Thompson et al., 2005). Cognitive variables are of great interest in suicide research because of the potential for change through intervention strategies (Stewart et al., 2005). According to Stewart et al. (2005: 364) ‘Western theories propose that cognitions are central to mood, that depression is a frequent con-comitant of suicidal ideation and behavior and that hopelessness is the most proximal variable to depression and suicidality’, ‘that hopeless-ness dominates and mediates the effects of other cognitive variables’, and ‘when level of depressive symptoms are controlled, variables such as hopelessness continues to be a risk factor for suicide behavior’.

It is unclear to what extent the association between these cognitive variables and suicidal behaviour among Western adolescents can be generalized to non-Western youth. The aim of this study was to assess the level of suicide attempts in three school-based samples of Southeast Asian adolescents (Taipei, Taiwan; the Philippines; Chiang Mai, Thai-land) and determine whether students who have attempted suicide score higher on measures of hopelessness and loneliness relative to those who have not made attempts. It was hypothesized that hopeless-ness and lonelihopeless-ness would be related to suicide attempts, and that hopelessness would continue to be associated with suicide attempts when controlling for loneliness. This study provides an opportunity to study the association of these cognitive risk factors in samples of non-Western youth and more specifically, the suicidal behaviour of Taiwanese, Filipino and Thai adolescents.

Methods

Subjects and data collection

The subjects for this study were 2,624 students from 21 high schools in Taiwan, 2,519 students from ten high schools in Thailand and 3,320 students from eight Philippine high schools. The 21 Taiwan schools

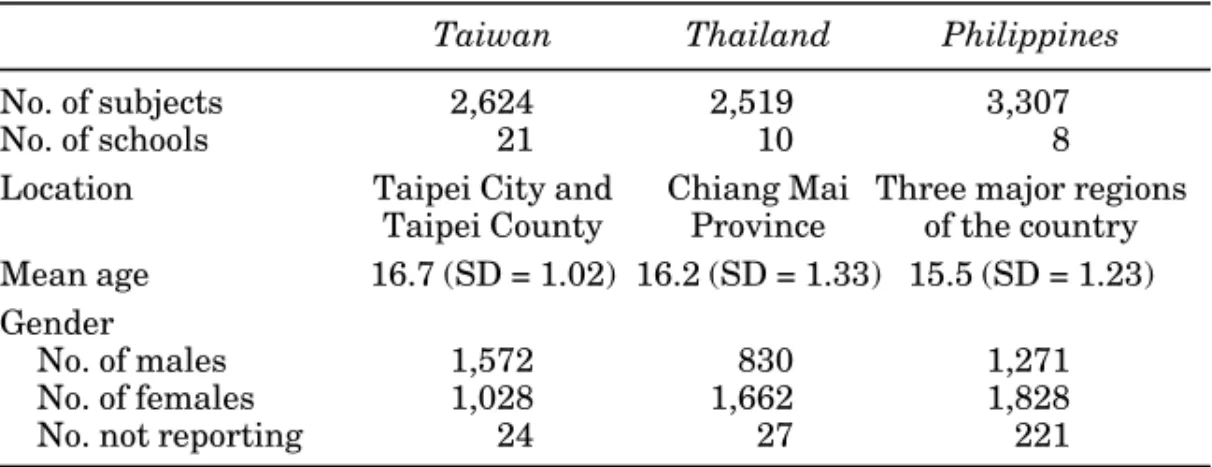

were randomly selected out of the total of 114 senior and vocational schools in the Taipei area. Within each school, one class in each grade (10th, 11th and 12th grade) was randomly selected to be included in the sample which consisted of 63 classes. Of the 21 Taiwanese schools, 14 were located in Taipei City and seven were in Taipei County. Schools in Thailand and the Philippines were not selected randomly, but purpo-sively selected to get a mixture of representation from urban and rural areas and private and public schools. The ten schools in the Thailand sample were located in Chiang Mai City and Chiang Mai Province. The eight Philippine schools represent schools from the three major regions of the country (Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao). Classes included in the Thailand and Philippine samples were those in which teachers volun-teered to allow the survey to be administered in their class. All of schools included in the samples were co-educational. Characteristics of the subjects are presented in Table 1.

Faculty members from three Southeast Asian universities (National Taiwan Normal University, Chiang Mai University and University of the Philippines) coordinated data collection in each respective sample. Questionnaires in each school and in in each of the samples were administered in regularly scheduled classes. Students were instructed not to place their names on questionnaires and to answer all questions honestly. Students were also informed that their participation was voluntary and that the decision to participate would not affect their grade in the class. Questionnaires were placed in envelopes by students after completion and not handed directly to school teachers or school personnel.

Survey instrumentation

The survey instrument for this study included items assessing suicide attempts and scales measuring the two cognitive variables of interest in this study – hopelessness and loneliness. Two items were used to

Table 1 Subject characteristics for the three samples

Taiwan Thailand Philippines

No. of subjects 2,624 2,519 3,307

No. of schools 21 10 8

Location Taipei City and Chiang Mai Three major regions Taipei County Province of the country Mean age 16.7 (SD = 1.02) 16.2 (SD = 1.33) 15.5 (SD = 1.23) Gender

No. of males 1,572 830 1,271

No. of females 1,028 1,662 1,828

assess prevalence of suicide attempts. One item asked respondents whether they had attempted suicide in the past 12 months. This assessment is similar to how suicide attempts are assessed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey (Grunbaum et al, 2004) and other similar studies (Chen et al., 2005; Wild et al., 2004). We also asked respondents whether they have ever attempted suicide and, if yes, how many times. According to Flisher et al. (2004), items asking adolescents about suicide attempts have adequate test–retest reliability over a period of 10–14 days. They observed agreement of suicide attempt prevalence rates over this time period at 95 percent.

Hopelessness was measured with the Beck Hopelessness Scale. It is a 20-item, true–false inventory designed to measure lack of hope about the future by assessing pessimistic cognitions concerning oneself and one’s future life (Beck et al., 1974). Hopelessness seems to constitute a fairly stable construct of negative expectancies which are often very resistant to change (Holden and Fekken, 1988). Scores on the scale can range from 0 (not hopeless) to 20 (extremely hopeless). The scale has been used frequently with adolescent and young adult samples (Langhinrichsen-Rohling et al., 1998). The literature reports alpha coefficients as high as 0.93 and a test–retest correlation of 0.85 for the scale (Beck et al., 1974; Holden and Fekken, 1988). We found accept-able alpha reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha) in our three samples on the hopelessness scale with coefficients of 0.71 in the Taiwanese sample, 0.72 in the Thai sample and 0.73 in the Philippine sample.

The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (R-UCLA) is a unidimensional index of loneliness, made up of 20 Likert-type items reflecting satisfac-tion and dissatisfacsatisfac-tion with life and social relasatisfac-tionships (Russell et al., 1980). Studies show that scores on this measure are moderately related to depression and low self-esteem, yet loneliness emerges as a distinct construct (Russell, 1982). Scores on this scale range from 20 (not lonely) to 80 (extremely lonely). It has emerged as the most widely accepted scale used to assess loneliness in a wide variety of studies with various populations as well as cross-culturally (Hojat and Cran-dall, 1989; Neto, 1992; Pretorius, 1993; Schumaker and Shea, 1993). Psychometric analyses of the UCLA scale have shown it to be a valid and highly reliable measure of loneliness across varied populations. According to Russell (1996), the scale has shown very high internal consistency with some studies showing a coefficient alpha between 0.89 and 0.94 and favourable test–retest reliability (r = 0 .73). We found acceptable internal consistency for this scale in our three samples with Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of 0.89 in the Taiwanese sample, 0.82 in the Thai sample and 0.75 in the Philippine sample.

The three versions of the survey instrument were translated from English to the respective language for each sample by native transla-tors. Native speakers back-translated survey items to make sure that each translation accurately reflected the meaning and intent of each item in the English version of the survey instrument. These versions of survey instruments are available from the corresponding author.

Data analysis

The two suicide attempt items, ever attempted suicide and attempted suicide in the past 12 months, served as categorical independent vari-ables in the study. Subjects were grouped as either ‘attempters’ or ‘nonattempters’ on these two variables. The dependent variables were the two cognitive variables hypothesized to be associated with suicide attempts – hopelessness and loneliness. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to test whether attempters and nonattempters differed on loneliness and hopelessness. Grade level and age were used as covariates and statistically controlled for in ANCOVA testing. Addi-tional ANCOVA tests were computed for hopelessness as a dependent measure while statistically controlling for loneliness as a covariate. ANCOVA tests were calculated separately for boys and girls in each sample. Descriptive statistics were also calculated to determine suicide attempt prevalence within each sample. Statistical tests were com-puted with SAS version 9.1 for Windows.

Results

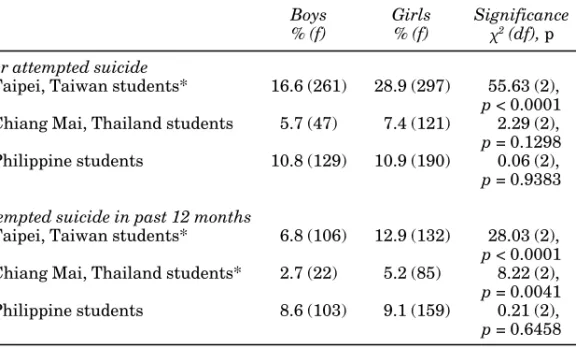

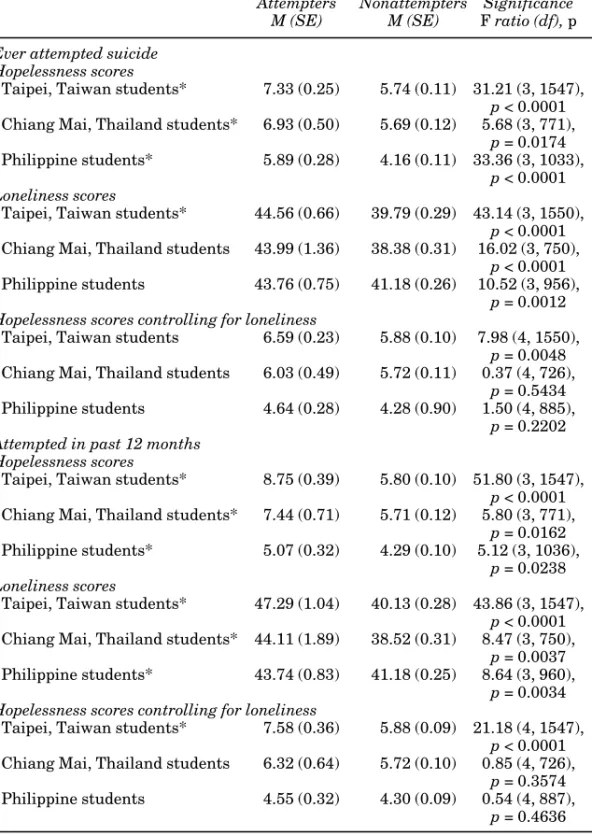

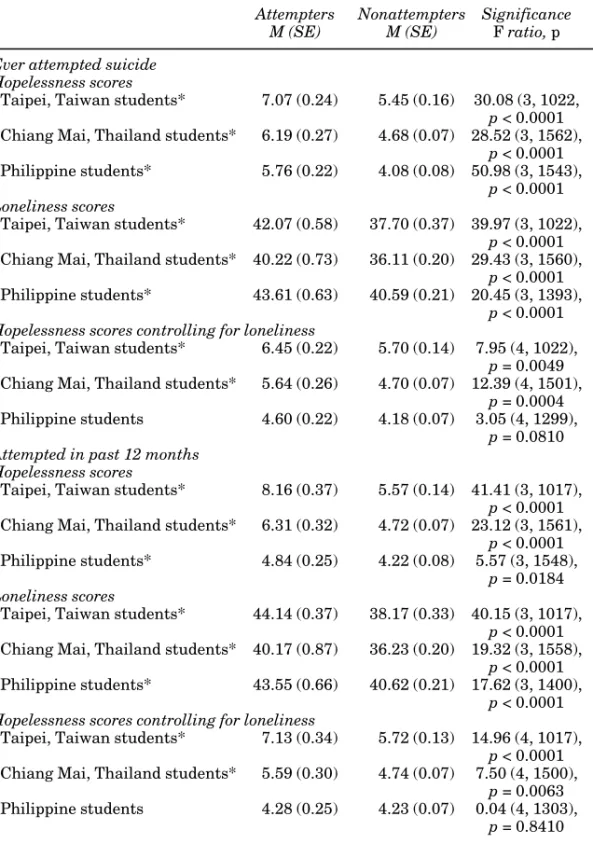

The prevalence of suicide attempts by sample and gender is presented in Table 2. Hopelessness and loneliness mean scores by sample and gender are displayed in Table 3. ANCOVA results showing differences between suicide attempters and nonattempters on hopelessness, loneli-ness and hopelessloneli-ness controlling from loneliloneli-ness are shown in Table 4 for boys and Table 5 for girls. Tables 2 through 5 provide test statistics, degrees of freedom and significance levels (p) for each statistical test used in the study.

Discussion

Prevalence of suicide attempt

Recent studies of the prevalence of suicide attempts among adolescents in various areas of the world show a wide range of prevalence figures (Chen et al., 2005; Dearden et al., 2005; Grunbaum et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2005; Wichstrom and Rossow, 2002; Wild et al., 2004 ). Therefore, it was not surprising that the prevalence of suicide attempts across the

Table 2 Prevalence of suicide attempters by sample and gender Boys Girls Significance % (f) % (f) c2(df), p

Ever attempted suicide

Taipei, Taiwan students* 16.6 (261) 28.9 (297) 55.63 (2), p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students 5.7 (47) 7.4 (121) 2.29 (2), p = 0.1298 Philippine students 10.8 (129) 10.9 (190) 0.06 (2), p = 0.9383 Attempted suicide in past 12 months

Taipei, Taiwan students* 6.8 (106) 12.9 (132) 28.03 (2), p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students* 2.7 (22) 5.2 (85) 8.22 (2), p = 0.0041 Philippine students 8.6 (103) 9.1 (159) 0.21 (2), p = 0.6458

*Boys differed significantly (p < 0.05) from girls on Chi-square tests.

Table 3 Hopelessness and loneliness mean scores by sample and gender

Boys Girls Significance M (SE) M (SE) F ratio (df), p Hopelessness

Taipei, Taiwan students 5.99 (0.10) 5.93 (0.13) F(3, 2576) = 0.12 p = 0.7292 Chiang Mai, Thailand 5.69 (0.10) 4.84 (0.07) F(3, 2356) = 3.98

students* p < 0.0001

Philippine students 4.35 (0.90) 4.28 (0.07) F(3, 2642) = 0.36 p = 0.5485 Loneliness

Taipei, Taiwan students 40.53 (0.26) 39.08 (0.33) F(3,2576) = 11.36 p = 0.7292 Chiang Mai, Thailand 38.47 (0.29) 36.49 (0.20) F(3,2330) = 30.50

students* p < 0.0001

Philippine students 41.37 (0.24) 40.88 (0.20) F(3,2414) = 2.35 p = 0.1254

*Boys differed significantly (p < 0.05) from girls on ANCOVA tests controlling for age and grade. Mean scores adjusted for age and grade.

Table 4 ANCOVA results testing the difference between suicide attempters and nonattempters on hopelessness, loneliness, and hopelessness controlling for lonelines – boys

Attempters Nonattempters Significance

M (SE) M (SE) F ratio (df), p

Ever attempted suicide Hopelessness scores

Taipei, Taiwan students* 7.33 (0.25) 5.74 (0.11) 31.21 (3, 1547), p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students* 6.93 (0.50) 5.69 (0.12) 5.68 (3, 771),

p = 0.0174 Philippine students* 5.89 (0.28) 4.16 (0.11) 33.36 (3, 1033),

p < 0.0001 Loneliness scores

Taipei, Taiwan students* 44.56 (0.66) 39.79 (0.29) 43.14 (3, 1550), p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students 43.99 (1.36) 38.38 (0.31) 16.02 (3, 750),

p < 0.0001 Philippine students 43.76 (0.75) 41.18 (0.26) 10.52 (3, 956),

p = 0.0012 Hopelessness scores controlling for loneliness

Taipei, Taiwan students 6.59 (0.23) 5.88 (0.10) 7.98 (4, 1550), p = 0.0048 Chiang Mai, Thailand students 6.03 (0.49) 5.72 (0.11) 0.37 (4, 726),

p = 0.5434 Philippine students 4.64 (0.28) 4.28 (0.90) 1.50 (4, 885),

p = 0.2202 Attempted in past 12 months

Hopelessness scores

Taipei, Taiwan students* 8.75 (0.39) 5.80 (0.10) 51.80 (3, 1547), p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students* 7.44 (0.71) 5.71 (0.12) 5.80 (3, 771),

p = 0.0162 Philippine students* 5.07 (0.32) 4.29 (0.10) 5.12 (3, 1036),

p = 0.0238 Loneliness scores

Taipei, Taiwan students* 47.29 (1.04) 40.13 (0.28) 43.86 (3, 1547), p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students* 44.11 (1.89) 38.52 (0.31) 8.47 (3, 750),

p = 0.0037 Philippine students* 43.74 (0.83) 41.18 (0.25) 8.64 (3, 960),

p = 0.0034 Hopelessness scores controlling for loneliness

Taipei, Taiwan students* 7.58 (0.36) 5.88 (0.09) 21.18 (4, 1547), p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students 6.32 (0.64) 5.72 (0.10) 0.85 (4, 726),

p = 0.3574 Philippine students 4.55 (0.32) 4.30 (0.09) 0.54 (4, 887),

p = 0.4636 *Suicide attempters differed significantly (p < 0.05) from nonattempters on ANCOVA tests controlling for age and grade (hopelessness also controlled for on designated tests displayed on this Table). Mean scores adjusted for age and grade.

Table 5 ANCOVA results testing the difference between suicide attempters and nonattempters on hopelessness, loneliness, and hopelessness controlling for loneliness – girls

Attempters Nonattempters Significance

M (SE) M (SE) F ratio, p

Ever attempted suicide Hopelessness scores

Taipei, Taiwan students* 7.07 (0.24) 5.45 (0.16) 30.08 (3, 1022, p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students* 6.19 (0.27) 4.68 (0.07) 28.52 (3, 1562),

p < 0.0001 Philippine students* 5.76 (0.22) 4.08 (0.08) 50.98 (3, 1543),

p < 0.0001 Loneliness scores

Taipei, Taiwan students* 42.07 (0.58) 37.70 (0.37) 39.97 (3, 1022), p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students* 40.22 (0.73) 36.11 (0.20) 29.43 (3, 1560),

p < 0.0001 Philippine students* 43.61 (0.63) 40.59 (0.21) 20.45 (3, 1393),

p < 0.0001 Hopelessness scores controlling for loneliness

Taipei, Taiwan students* 6.45 (0.22) 5.70 (0.14) 7.95 (4, 1022), p = 0.0049 Chiang Mai, Thailand students* 5.64 (0.26) 4.70 (0.07) 12.39 (4, 1501),

p = 0.0004 Philippine students 4.60 (0.22) 4.18 (0.07) 3.05 (4, 1299),

p = 0.0810 Attempted in past 12 months

Hopelessness scores

Taipei, Taiwan students* 8.16 (0.37) 5.57 (0.14) 41.41 (3, 1017), p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students* 6.31 (0.32) 4.72 (0.07) 23.12 (3, 1561),

p < 0.0001 Philippine students* 4.84 (0.25) 4.22 (0.08) 5.57 (3, 1548),

p = 0.0184 Loneliness scores

Taipei, Taiwan students* 44.14 (0.37) 38.17 (0.33) 40.15 (3, 1017), p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students* 40.17 (0.87) 36.23 (0.20) 19.32 (3, 1558),

p < 0.0001 Philippine students* 43.55 (0.66) 40.62 (0.21) 17.62 (3, 1400),

p < 0.0001 Hopelessness scores controlling for loneliness

Taipei, Taiwan students* 7.13 (0.34) 5.72 (0.13) 14.96 (4, 1017), p < 0.0001 Chiang Mai, Thailand students* 5.59 (0.30) 4.74 (0.07) 7.50 (4, 1500),

p = 0.0063 Philippine students 4.28 (0.25) 4.23 (0.07) 0.04 (4, 1303),

p = 0.8410 *Suicide attempters differed significantly (p < 0.05) from nonattempters on ANCOVA tests controlling for age and grade (hopelessness also controlled for on designated tests displayed on this table). Mean scores adjusted for age and grade.

three samples of Asian youth represented in this study were not consis-tent. Among girls, prevalence was highest among girls in the Taiwan sample (12.9 percent in the past 12 months, 28.9 percent ever attempt-ing) and lowest among Thai girls (5.2 percent in the past 12 months, 7.4 percent ever attempting), with Philippine girls in-between (9.1 percent in the past 12 months, 10.9 percent ever attempting). Philippine boys (8.6 percent) reported the highest prevalence of attempted suicide, followed by Taiwanese boys (6.8 percent) and Thai boys (2.7 percent). Among boys, the order was different for ever attempted suicide, with Taiwanese boys showing the highest prevalence (16.6 percent), followed by Philippine boys (10.8 percent) and Thai boys (5.7 percent). When interpreting these estimates of suicide attempt prevalence, it is important to keep in mind that there may be unaccounted factors that could cause inaccurate self-reporting. Social desirability bias is one factor to consider. It is possible that samples may have differed in terms of hesitancy or reluctance to report information on a written survey instrument about such a sensitive topic as suicidal behaviour. Cultural differences could certainly account for possible differences in willingness to report personal information about suicidal behaviour, even when the young people were assured that their information would remain anonymous and not be seen by school personnel. The conceptu-alization of ‘suicide attempt’ may have also differed between the samples.

With these limitations in mind, the high prevalence of suicide rate among the Taiwanese youth, particularly girls, was concerning. Our findings showed that nearly one in three Taiwanese girls and one in six Taiwanese boys have attempted suicide in their lifetime (and about one in eight girls and one in 15 boys in the past year). Recent news-paper articles in Taiwan cite that the number of youths committing suicide has increased dramatically in the past decade and that suicide has become the second-leading cause of death among Taiwanese youth aged 15–24 (‘Youth Suicide Rate’, 2006). The health professional litera-ture and the Taiwan Department of Health also note that an increasing suicide rate in Taiwan for all age groups has become a critical mental health and public health issue (Department of Health, 2004; Sun et al., 2005). There are important cultural meanings associated with suicidal behaviour in Taiwan and other Chinese societies that can cause those who have attempted suicide tremendous embarrassment and social pain in their social and family relationships. Two Chinese cultural values, mientze (saving face) and hsiao (filial piety), might increase suicide risk after surviving attempts and distinguish Chinese suicide experiences from those of other cultural groups (Tzeng, 2001; Tzeng and Lipson, 2004).

al., 2001; Wichstrom and Rossow, 2002), we found a higher prevalence of suicide attempts among girls than boys in two of our samples (see Table 2). This was true for the Taiwan and Thailand samples, but not for the Philippine sample in which boys and girls prevalence did not differ statistically. Most research on gender differences in suicidal behaviour across several cultures and age groups shows a ‘paradoxical’ effect, in which females are more likely to attempt suicide, but males are more likely to commit suicide (Evans et al., 2005; Lewinsohn et al., 2001; Wichstrom and Rossow, 2002). A study of suicide in North Thai-land also shows this trend (Lotrakul, 2005). This is an important phenomenon to keep in mind when studying suicidal behaviour, but beyond the scope of the current study because we did not attempt to collect additional information on actual suicides in the geographical areas represented by the study samples.

Hopelessness and loneliness

Hopelessness or pessimistic attitude about the future has been shown to be associated with suicidality and identified as an important risk factor for suicidal behaviour (Haatainen et al., 2004). A recent study of Hong Kong Chinese and Caucasian American adolescents found hope-lessness to be the strongest cognitive variable linking suicidal ideation in both cultures and in both boys and girls (Stewart et al., 2005). In our study, hopelessness scores ranked highest among the Taiwanese stu-dents and lowest among the Philippine stustu-dents, with Thai stustu-dents in-between (see Table 3). It is interesting that this pattern also largely matched the rankings of the three samples in terms of suicide attempts. For example, Taiwanese boys and girls scored the highest on hopelessness and also had the highest prevalence of ever attempting suicide, while the lowest scores on hopelessness were found for Philip-pine students who correspondingly reported the lowest prevalence of ever attempting suicide. Hopelessness has been identified to be associ-ated with suicide completion in both adults and youth, but it is unclear whether hopelessness per se or depression accounts for this association in studies differentiating suicidal from nonsuicidal youth (Gould and Kramer, 2001). Our results also found an association with suicidal attempt behaviour (in past 12 months and ever) and hopelessness across all three samples and both genders (see Tables 4 and 5). Boys and girls in the Taiwanese, Thai, and Philippine samples who attempted suicide scored significantly higher on ANCOVA tests with hopelessness as the dependent variable than those not attempting suicide.

Social isolation and the lack of social relationships represents an area within the literature on adolescent suicidal behaviour that deserves more attention (Ayyash-Abdo, 2002; Bearman and Moody,

2004; Perez-Smith et al., 2002). Young people who are missing out on the emotional and social support offered by peer and/or family relation-ships are at risk for loneliness. Loneliness is rarely a major focus of attention in studies of adolescent suicide, although it has been linked to suicide ideation and suicide attempt (Stravynski and Boyer, 2001). We examined the relationship between suicide attempt behaviour and loneliness and found significant association of loneliness for attempted suicide in the past 12 months and ever attempted suicide across all three samples and both genders (see Tables 4 and 5). Boys and girls in the Taiwanese, Thai and Philippine samples who attempted suicide scored significantly higher on ANCOVA tests with loneliness as the dependent variable relative to those not attempting suicide.

A major focus of our study was to determine the impact of statistic-ally controlling loneliness in the examination of the relationship between hopelessness and suicide attempt in the three samples. Research has shown that the relationship between hopelessness and suicide risk is often minimized or not maintained when depression is statistically controlled (Thompson et al., 2005). Lewinsohn et al. (1993) found that hopelessness did not predict adolescent suicide attempts when depression was controlled in statistical analyses. Cole (1989) found that hopelessness was not related to suicidal ideation for males, but was so for females, when depression and a measure of social desir-ability was controlled for. Yet, Mazza and Reynolds (1998) noted that hopelessness remained as a predictor of suicidal ideation for both males and females when controlling for depression and a number of socio-environmental factors. Although we did not measure depression in our study, we desired to determine the result of statistically control-ling for loneliness in suicide attempt-hopelessness relationships. We found that statistically controlling for loneliness demonstrably weakened F-ratios on ANCOVA tests across samples and for both gen-ders. In fact, ANCOVA tests of suicide attempters and nonattempters (in the past 12 months) on hopelessness, with loneliness controlled, were no longer significant for Thai and Philippine boys and Philippine girls. In a likewise fashion, concerning ever attempted suicide, ANCOVA tests of attempters and nonattempters on hopelessness were also no longer significant, with loneliness controlled, for Thai and Philippine boys and Philippine girls. Taiwanese boy and girl and Thai girl suicide attempters continued to score significantly higher on hope-lessness than non attempters, when loneliness was controlled. However, the strength of the relationship was considerably reduced when statistically removing the effect of loneliness.

Our results showing a prominent relationship between suicide attempt behaviour and loneliness are an important addition to the literature. These results support the inclusion of loneliness, as well as

hopelessness and depression, as a potential cognitive risk factor in studies of adolescent suicidal behaviour. It is likely that loneliness is associated with depression in these samples of Asian youth. In studies of Western youth, loneliness is a known correlate of depression (Brage et al., 1995; Seigner and Lilach, 2004) and this may also be true of Chinese adolescents (Anderson, 1999). Loneliness is sometimes viewed as a subtype of depression that is more restricted to interpersonal prob-lems. Loneliness is considered primarily a social problem, whereas depression can be nonsocial or a mixture of social and nonsocial prob-lems (Anderson, 1999). The greater emphasis typically placed on the social group in Asian cultures (interdependent cultures) is likely to impact how loneliness emerges within the samples of young people that we studied than what might be true for adolescents in Western nations characterized by more independent cultural patterns. In other words, the psychosocial variables that we measured – loneliness and hopeless-ness – may manifest themselves differently in various cultures of youth. While the Western view of self emphasizes separateness, auton-omy, independence, individualism and distinctness, Asian societies have adopted a more socio-centric, collectivistic, connected and interde-pendent construal of self. Thus, it would be interesting to examine the impact of controlling for loneliness in the suicide attempt-hopelessness relationship in additional samples of adolescents.

This study suffers from certain methodological limitations. The three samples of adolescents do not fairly represent all adolescents within a specific nation or geographic area of the nation. The psychosocial variables included in this study, although used widely in Western nations, need more validation in Asian and cross-cultural studies. We have addressed how notions of suicide attempt, hopelessness and lone-liness may manifest differently between and among the three samples and in comparison to Western youth populations. Social desirability of response may have also been a factor. Young people in these samples may have differed in willingness to report suicide attempt behaviour and/or feelings related to hopelessness and loneliness.

References

Anderson, C. A. (1999) ‘Attributional Style, Depression, and Loneliness: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of American and Chinese Students’, Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 25(4): 482–499.

Ayyash-Abdo, H. (2002) ‘Adolescent Suicide: An Ecological Approach’, Psychol-ogy in the School 39(4): 459–75.

Bearman, P. S. and Moody, J. (2004) ‘Suicide and Friendships Among Ameri-can Adolescents’, AmeriAmeri-can Journal of Public Health 94(1): 89–95.

Beck, A. T., Weissman, A., Lester, D. and Texler, L. (1974) ‘The Measurement of Pessimism: The Hopelessness Scale’, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 42: 861–65.

Borowsky, I. W., Ireland, M, and Resnick, M. D. (2001) ‘Adolescent Suicide Attempts: Risks and Protectors’, Pediatrics 107(3): 485-93.

Brage, D., Campbell-Grossman C. and Dunkel, J. (1995) ‘Psychological Corre-lates of Adolescent Depression’, Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing 8(4): 23–30.

Chen, P., Lee, L. K., Wong, K. C. and Kaur, J. (2005) ‘Factors Relating to Adolescent Suicidal Behavior: A Cross-Sectional Malaysian School Survey’, Journal of Adolescent Health 37(6): 460–66.

Cho, S. J., Jeon, H. J., Kim, J. K., Suh, T. W., Kim, S. U., Hahm, B. J., Suh, D. H., Chung, S. J. and Cho M. J. (2002) ‘Prevalence of Suicide Behaviors (Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempt) and Risk Factors of Suicide Attempts in Junior and High School Adolescents’, Journal of Korean Neuro-psychiatriatric Association 41(6): 142–1155.

Cole, D.A. (1989) ‘Psychopathology of Adolescent Suicide: Hopelessness, Coping Beliefs, and Depression’, Journal of Abnormal Psychology 98: 248–55.

Committee on Adolescence, American Academy of Pediatrics (2000) ‘Suicide and Suicide Attempts in Adolescents’, Pediatrics 105(4): 871–74.

Dearden, K. A., De La Cruz, N. G., Crookston, B. T., Novilla, M. L. B. and Clark, M. (2005) ‘Adolescents at Risk: Depression, Low Academic Perform-ance, Violence, and Alcohol Increase Bolivian Teenagers’ Risk of attempted Suicide’, The International Electronic Journal of Health Education 8: 104–19.

Department of Health, Taiwan. Executive Yuan (2004) Health and Vital Statistics. Taipei: Taiwan.

Evans, E., Hawton, K., Rodham, K. and Deeks, J. (2005) ‘The Prevalence of Suicidal Phenomena in Adolescents: A Systematic Review of Population-Based Studies’, Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 35(3): 239–50. Flisher, A. J., Evans, J., Muller, M. and Lombard, C. (2004) ‘Brief Report:

Test–Retest Reliability of Self-Reported Adolescent Risk Behavior’, Journal of Adolescence 27: 207–12.

Gould, M. S., Greenberg, T., Velting, D. and Shafer, D. (2003) ‘Youth Suicide Risk and Preventive Interventions: A Review of the Past 10 Years’, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 42: 386–405. Gould, M. S. and Kramer, R. A. (2001) ‘Youth Suicide Prevention. Suicide and

Life-Threatening Behavior’, 31 (Suppl): 6–31.

Grunbaum, J. A., Kann, L., Ross, J., Hawkins, J., Lowry, R., Harris, W. A., McManus, T., Chyen, D. and Collins, J. (2004) ‘Youth Risk Behavior Sur-veillance – United States, 2003’, SurSur-veillance Summaries 53(No.SS-2):1–96. Haatainen, K., Tanskanen, A., Kylma, J., Honkalampi, K., Kiovumaa-Honka-nen, H., Hintikka, J. and Viinamaki, H. (2004) ‘Factors Associated With Hopelessness: A Population Study’, International Journal of Social Psychia-try 50(2): 142–52.

Halcon, L., Beuhring, T. and Blum, R. W. (2000) A Portrait of Adolescent Health in the Caribbean. Washington, DC: WHO Collaborating Centre on Adoles-cent Health, University of Minnesota and Pan American World Health Organization.

Hojat, M. and Crandall, R. (1989) Loneliness: Theory, Research, and Applica-tions, Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Holden, R.R. and Fekken, G. C. (1988) ‘Test–Retest Reliability of the Hopeless-ness Scale and its Items in a University Population’, Journal of Clinical Psychology 44: 40–43.

Langhinrichsen-Rohling, J,. Lewinshohn, P., Rohde, P., Seeley, J., Monson, C. M., Meyer, K. A. and Langford, R. (1998) ‘Gender Differences in the Suicide-Related Behaviors of Adolescents and Young Adults’, Sex Roles: A Journal of Research 39(11/12): 839–54.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Rohde, P. and Seeley, J. R. (1993) ‘Psychosocial Characteris-tics of Adolescents With a History of Suicide Attempt’, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 32: 60–68.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Rohde, P., Seeley, J. R. and Baldwin, C. L. (2001) ‘Gender Differences in Suicide Attempts From Adolescence to Young Adulthood’, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 40: 427–34.

Liu, X., Tein, J., Zhao, Z. and Sandler, I.N. (2005) ‘Suicidality and Correlates Among Rural Adolescents of China’, Journal of Adolescent Health 37(6): 443–51.

Lotrakul, M. (2005) ‘Suicide in the North of Thailand’, Journal of the Medical Association of Thailand 88(7): 944–48.

Mazza, J. J. and Reynolds, W. M. (1998) ‘A Longitudinal Investigation of Depression, Hopelessness, Social Support, Major and Minor Life Events and Their Relationship to Suicidal Ideation in Adolescents’, Suicide and Life-Threatening Behaviors 28: 358–74.

Neto, F. (1992) ‘Loneliness Among Portuguese Adolescents’, Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal 20(1): 15–22.

Perez-Smith, A., Spirito, A. and Boerges, J. (2002) ‘Neighborhood Predictors of Hopelessness Among Adolescent Suicide Attempts: Preliminary Investiga-tion’, Suicide and Life-Threatening Behaviors 32(2): 139–45.

Pretorius, T. B. (1993) ‘The Metric Equivalence of the UCLA Loneliness Scale for a Sample of South African Students’, Educational and Psychological Measurement 53(1): 233–39.

Ruangkanchanasetr, S., Plitponkarnpim, A., Hetrakul, P. and Kongsakon, R. (2005) ‘Youth Risk Behavior Survey: Bangkok, Thailand’, Journal of Adoles-cent Health 36(3): 227–35.

Russell, D. (1982) ‘The Measurement of Loneliness’, in L. A. Peplau and D. Perlman (eds) Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research, and Therapy, pp. 81–104. New York: John Wiley.

Russell, D. W. (1996) ‘UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): Reliability, Validity, and Factor Structure’, Journal of Personality Assessment 66(1): 20-40. Russell, D., Peplau, L. and Cutrona, C. E. (1980) The Revised UCLA Loneliness

Scale: Concurrent and Discriminant Validity Evidence’, Journal of Person-ality and Social Psychology 39(3): 472–80.

Safer, D. J. (1997) ‘Self-Reported Suicide Attempts by Adolescents’, Annals of Clinical Psychiatry 9(4): 263–69.

Schumaker, J. F. and Shea , J. D. (1993) ‘Loneliness and Life Satisfaction in Japan and Australia’, Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied 127(1): 65–71.

Seginer, R. and Lilach, E. (2004) ‘How Adolescents Construct Their Future: The Effects of Loneliness on Future Orientation’, Journal of Adolescence 27: 625–43.

Stewart, S. M., Kennard, B. D., Lee, P. W. H., Mayes, T., Hughes, C. and Emslie, G. (2005) ‘Hopelessness and Suicidal Ideation Among Adolescents in Two Cultures’, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 46(4): 364– 72.

and Parasuicide: A Population-Wide Study’, Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 31(1): 32–40.

Sun, F.-K, Long, A., Boore, J. and Tsao, L.-I. (2005) ‘Suicide: A Literature Review and its Implications for Nursing Practice in Taiwan’, Journal of Psy-chiatric and Mental Health Nursing 12: 447–55.

Thompson, E. A., Mazza, J. J., Herting, J. R., Randell, B. P. and Eggert, L. L. (2005) ‘The Mediating Roles of Anxiety, Depression, and Hopelessness on Adolescent Suicidal Behaviors’, Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 35(1): 14–34.

Tzeng, W.-C. (2001) ‘Being Trapped in a Circle: Life After a Suicide Attempt in Taiwan’, Journal of Transcultural Nursing 12: 302–09.

Tzeng, W.-C., and Lipson, J. G. (2004) ‘The Cultural Context of Suicide Stigma in Taiwan’, Qualitative Health Research 14(3): 345–58.

Wichstrom, L. and Rossow, I. (2002) ‘Explaining the Gender Difference in Self-Reported Suicide Attempts: A Nationally Representative Study of Norwegian Adolescents’, Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 32(2): 101–16.

Wild, L. G., Flisher, A. J. and Lombard, C. (2004) ‘Suicidal Ideation and Attempts in Adolescents: Associations With Depression and Six Domains of Self-Esteem’, Journal of Adolescence 27(6): 611–24.

Yip, P. S., Liu, K. Y., Lam, T. H., Stewart, S. M., Chen, E. and Fan, S. (2004) ‘Suicidality Among High Schools in Hong Kong, SAR’, Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 34(3): 284–97.

‘Youth Suicide Rate Climbs’, (2006, January 3) Taipei Times [Online version]. Retrieved March 3, 2006 from http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/ archives/2006/01/03/2003287195.