Chapter Two Literature Review

In this chapter, the review of relevant literature contains five sections. The first section retraces the reform of ELT in Taiwan and its impacts on textbook compilation.

The second section provides an overview of the role of grammar teaching in different ELT approaches. The third section discusses the different positions towards formal grammar instruction. The fourth section deals with communicativeness of grammar activities. Different scales for classifying the level of communicativeness are illustrated in this section. The final part discusses different theoretical viewpoints towards grammar sequencing.

Historical Changes in ELT and Textbook Development in Taiwan

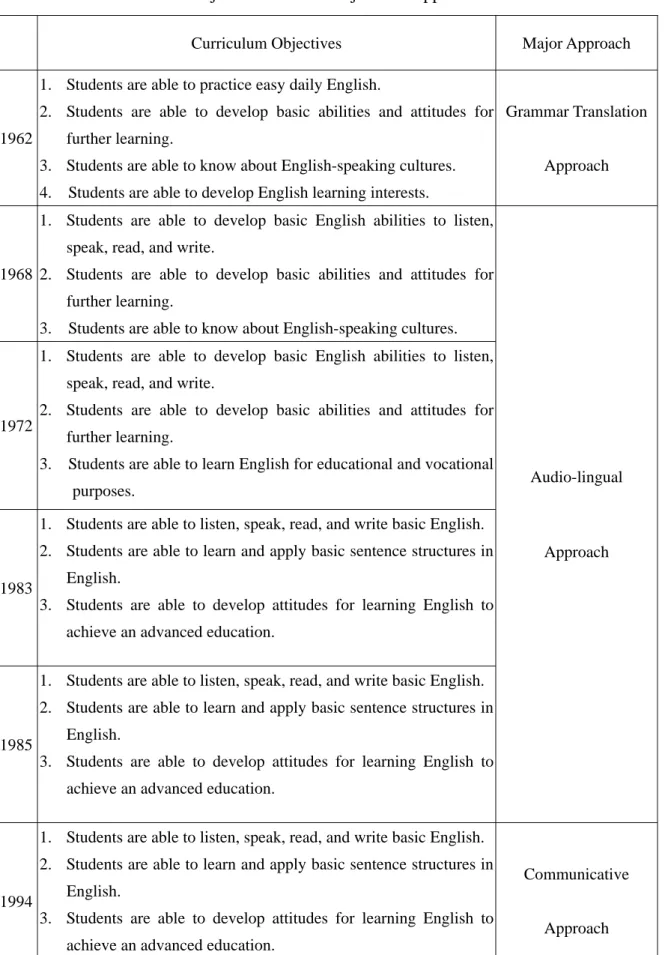

Textbook design develops with time and also shows the main-stream values of the contemporary ELT paradigm. Rubin and Thompson (1982) indicate that different textbooks reflect different approaches to language teaching and learning. It is the same case in Taiwan. According to Cheng (2003), textbook development in Taiwan went through several stages. The first version of the Curriculum Standards for Junior High Schools was promulgated by the MOE in 1962. During that period of time, the dominant approach was the Grammar Translation Method (GTM), which had an influence at the initial stages of ELT in Taiwan. Curriculum Standards in 1962 revealed GTM-oriented curriculum objectives. In later amendments in 1968, 1972, 1983, and 1985, Curriculum Standards added the concept of the four skills. That is to say, techniques used in the GTM were not the only solution for ELT in Taiwan.

Instead, oral and aural practices were highly emphasized. This echoed the trend in world ELT development at that time, namely, the Audio-lingual Approach (AA).

Although listening and speaking gained more attention in this approach, it still

emphasized language structures. The influence of the AA can be found in the curriculum objectives in the Curriculum Standards from 1968 to 1985. Later the Curriculum Standards were amended again in 1994. The 1994 Standards pointed out that ELT should be balanced on the four skills, not just on reading. The Communicative Approach was recommended as the principle for textbook writing.

Textbook content began to focus on communicative functions and topics, which syllabus design is mainly based on, while grammar played a supportive role. Cheng (2003) also lists the development of ELT in Taiwan in terms of curriculum objectives and the main approach adopted contemporarily. From Table 1 adopted from her study and translated into English by the researcher, the evolution of ELT in Taiwan can be clearly realized.

Table 1 Curriculum Objectives and the Major ELT Approaches in Taiwan

Curriculum Objectives Major Approach

1962

1. Students are able to practice easy daily English.

2. Students are able to develop basic abilities and attitudes for further learning.

3. Students are able to know about English-speaking cultures.

4. Students are able to develop English learning interests.

Grammar Translation

Approach

1968

1. Students are able to develop basic English abilities to listen, speak, read, and write.

2. Students are able to develop basic abilities and attitudes for further learning.

3. Students are able to know about English-speaking cultures.

1972

1. Students are able to develop basic English abilities to listen, speak, read, and write.

2. Students are able to develop basic abilities and attitudes for further learning.

3. Students are able to learn English for educational and vocational purposes.

1983

1. Students are able to listen, speak, read, and write basic English.

2. Students are able to learn and apply basic sentence structures in English.

3. Students are able to develop attitudes for learning English to achieve an advanced education.

1985

1. Students are able to listen, speak, read, and write basic English.

2. Students are able to learn and apply basic sentence structures in English.

3. Students are able to develop attitudes for learning English to achieve an advanced education.

Audio-lingual

Approach

1994

1. Students are able to listen, speak, read, and write basic English.

2. Students are able to learn and apply basic sentence structures in English.

3. Students are able to develop attitudes for learning English to achieve an advanced education.

Communicative

Approach

Now

1. Students are able to develop basic communicative competence.

2. Students are able to develop interests and methods for learning English.

3. Students are able to know the difference between their native culture and foreign culture.

(Adapted from Cheng, 2003)

Su (2003) talks about the same developmental stages in Curriculum Standards and ELT approaches. He further mentions the textbook development. The first set of textbooks was designed under the Curriculum Standards in 1968, and the second set followed the Curriculum Standards in 1972. As pointed out by Cheng (2003), Su considers these two sets to reflect the influence of the AA. The third set followed the Curriculum Standards amended in 1983. In contrast with Cheng’s (2003) observation, Su thinks this version of the Curriculum Standards and MOE textbook reflect the communicative orientation of the Natural Approach. In his view, the third set of MOE textbooks is more communication-oriented than the previous ones. The fourth and last set of MOE textbooks was designed according to the Curriculum Standards amended in 1994. This set of textbooks reflects a trend towards the Communicative Approach and also offers a frame of reference in the present study. The last MOE textbooks began to be used by junior high school students in 1997. Later in 1999, the senior high school students started to use the commercial textbooks and began an era of privatization in textbook market.

Although the last set of MOE textbooks is the first set adopting the Communicative Approach as the principle for design and tries to emphasize communicative functions and authentic activities, it does not very much satisfy the students’ communicative needs. Chen (2002) states:

The English teachers criticized that MOE English textbooks could not assure students with the communicative ability even if they had learned everything in the English textbooks. In other words, the MOE English textbooks did not

truly correspond to the Communicative Approach. Therefore, the demand for new English textbooks became even more heated. (p. 2)

Chen’s description points out the need for more communicative orientation of English textbooks. In 1994, educational reform in Taiwan started. Education issues were re-evaluated by the Executive Yuan. As far as textbooks went, the changes were also huge. NICT withdrew from the market of textbook compiling and publishing.

Instead, private publishers got the right to compile textbooks. NICT played the role of a censor. Commercial textbooks compiled by private publishers needed to be approved by NICT, licensed by the MOE and then evaluated, selected and used in schools.

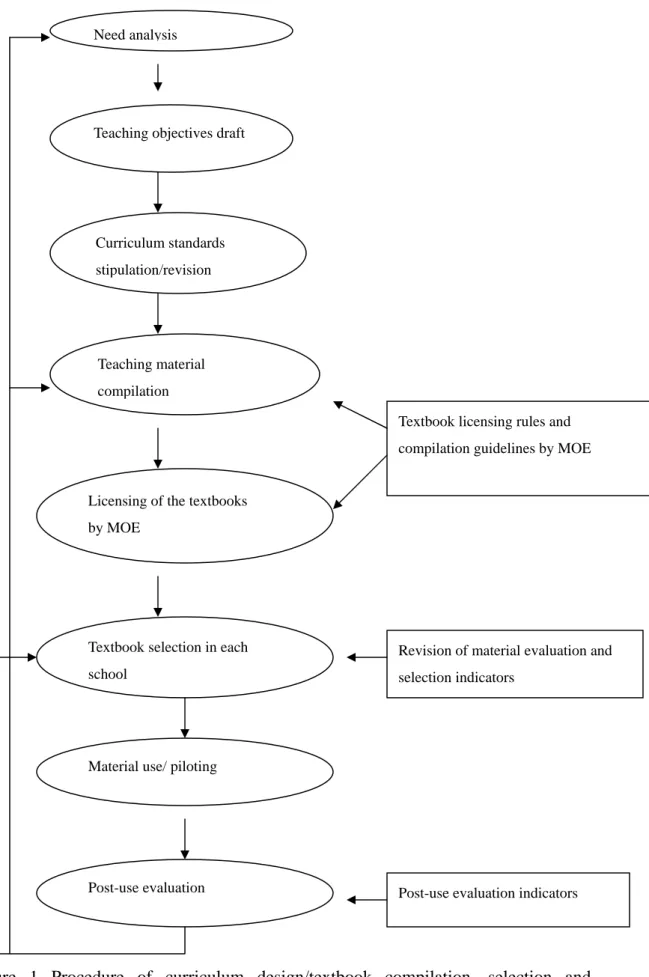

According to Shih (2000), the procedure of English textbook selection has to be in two steps. The first step is the licensing of a textbook by the MOE; the second one is the selection of a textbook in individual schools. The job of NICT is to help the MOE examine if the commercial textbooks meet the principles of the Curriculum Guidelines and compilation requirements. Shih (2000) further illustrates the whole procedure of curriculum design, material compilation, textbook selection and evaluation clearly in Figure 1.

Need analysis

Teaching objectives draft

Curriculum standards stipulation/revision

Teaching material compilation

Licensing of the textbooks by MOE

Textbook licensing rules and compilation guidelines by MOE

Revision of material evaluation and selection indicators

Textbook selection in each school

Material use/ piloting

Post-use evaluation Post-use evaluation indicators

Figure 1 Procedure of curriculum design/textbook compilation, selection and evaluation (Shih, 2000)

Since 1996, the elementary schools have got the right to select their own textbooks. Later, in 1999, senior high school teachers started to choose theirs. In 2002, junior high school teachers began to make their first textbook selections.

Publishers are supposed to design their textbooks on the basis of the Nine-year Integrated Curriculum Guidelines issued by the MOE. Textbooks published in 2001 are based on the Tentative Curriculum Guidelines issued in 2000, and they are known as the tentative version. Junior high school students who enrolled in 2002 used this version. What published in 2002 were compiled according to the new Curriculum Guidelines amended in 2001. Students who enrolled after 2003 used this version. The present study adopts textbooks of the standard version as the subjects for analysis.

The Curriculum Guidelines tend to suggest principles of Communicative Language Teaching to be adopted in textbook design. They also suggest the goal of ELT to be focused on developing students’ communicative competence. Under this precondition, the design of textbook is supposed to use authentic topics and communicative activities to facilitate acquiring communicative competence.

The Role of Grammar Teaching and the Shift of ELT Approaches

ELT in Taiwan has gone through several stages of historical change. These changes reflect contemporary educational policy and pedagogical trends. In the development of the ELT approach, a crucial issue is the role of grammar. The following sections discuss the role of grammar in different ELT approaches and whether grammar instruction facilitates language learning from different perspectives.

Grammar teaching in Grammar Translation Method

The goal of the Grammar Translation Method (GTM) is to teach learners the

formal properties of target language and thus grammar is taken as the basic component and starting point for instruction. The focus of teaching is on grammatical analysis while little attention is paid to the content of texts. The syllabus consists of a list of selected grammar points and vocabulary to be learned. This approach adopts the most traditional way of grammar teaching, namely, grammar explanation and error correction. Thornbury (1999) states, “ Grammar translation courses following a grammar syllabus and lessons typically begin with an explicit statement of the rule, followed by exercises involving translation into and out of the mother tongue”.

In the GTM, pedagogical situations in classrooms are just like the ones described by Celce-Murcia (1991):

1. Instruction is given in the native language.

2. The teacher does not have to be able to speak the target language fluently.

3. Focus is on the grammatical parsing, i.e., the form and inflection of words.

4. A typical exercise is to translate sentences from the target language.

The result is usually that students are unable to use the language for communication because they cannot get sufficient communicative practice and pay too much attention to grammatical forms.

Grammar teaching in Audio-lingual Approach

Audiolingualism is based on behaviorist theory and considers language as a kind of habit formation. The historical background is during and after World War II when the development of spoken fluency was required and thus is basically a reaction against the GTM, which only emphasizes the knowledge of grammar rather than the use of it. However, in the Audio-lingual Approach (AA), the spoken language taught is still presented in a highly structured sequence of forms and accompanied by a

formal grammar explanation. Grammatical structures are sequenced from simple to complex. Grammar still plays an important role here although not so straightforwardly presented as in the GTM.

The Audio-lingual syllabus consists of a list of sentence patterns and thus is also grammatical or structure-based in origin. Using lots of pattern-practice drills and repetitions for accurate production of target language is the distinguishing feature of its classroom practice. Repetition, memorization, and error correction of grammatical items are the basic methods of grammar instruction in the AA.

The GTM and the AA belong to the kind of approach termed by Long &

Robinson (1998) as “focus on forms”, which may still be a common approach in the junior and senior high school classrooms in Taiwan. (Li, 2003; Su, 2003). This approach entails the isolation and extraction of linguistic features from context or communicative activity, and emphasizes classroom practice like translation exercises, error correction, repetition of models, and explicit negative feedback. (Long &

Robinson, 1998)

Grammar teaching in Communicative Approach

In contrast to the GTM and the AA, the Communicative Approach has shifted the emphasis from solely grammatical knowledge to communicative competence. That is to say, the functional face of language is emphasized, and thus grammar is no longer the main focus in the Communicative Approach.

Communicative competence

In the GTM and the AA, linguistic competence is the major concern in ELT. Here linguistic competence refers to grammatical competence. Chomsky (1965) defines linguistic competence as “the intuitive grammatical knowledge” owned by native

speakers with which speakers are able to create an infinite numbers of grammatical sentences and to understand each other’s speech. Later Hymes (1971) reacts to Chomsky’s definition of the linguistic competence and proposes the term

“communicative competence” to emphasize the use of language in social context. In his view, a person who acquires communicative competence gets both knowledge and ability for language use with respect to:

1. whether (and to what degree) something is formally possible;

2. whether (and to what degree) something is feasible in virtue of the means of implementation available;

3. whether (and to what degree) something is appropriate (adequate, happy, successful) in relation to a context in which it is used and evaluated;

4. whether (and to what degree) something is in fact done, actually performed, and what its doing entails. (Hymes, 1971, p.281)

Hymes mentions, “Communicative competence involves interaction among grammatical, psycholinguistic, sociocultural and probabilistic subsystems” (Canale &

Swain, 1980, p.16).

In Canale and Swain’s study (1980), they further identify four dimensions of communicative competence: grammatical competence, sociolinguistic competence, discourse competence, and strategic competence. For Canale and Swain, grammatical competence means the mastery of language code. Socioliguistic competence refers to appropriateness of utterances with respect both to meaning and form. Discourse competence indicates the mastery of combining grammar and meaning to achieve unity in speech or written texts. Strategic competence is the mastery of verbal and non-verbal communication strategies used to compensate for breakdowns in communication and to make communication more effective. Figure 2 elucidates their theoretical scheme.

Communicative Competence

Grammatical Sociolinguistic Discourse Strategic

Competence Competence Competence Competence

Figure 2 Canale and Swain’s theoretical scheme of communicative competence (Canale and Swain, 1980)

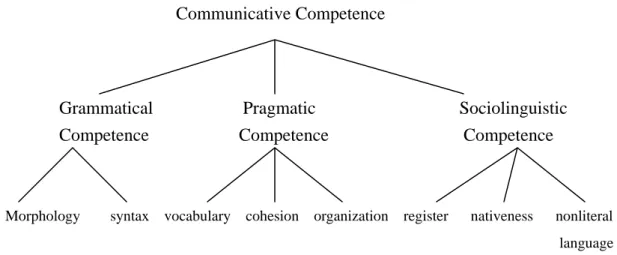

Based on Canale and Swain’s study (1980), Bachman and Palmer (1982) propose three elements to communicative competence: linguistic competence, pragmatic competence, and sociolinguistic competence. Figure 3 illustrates their theoretical scheme.

Communicative Competence

Grammatical Pragmatic Sociolinguistic Competence Competence Competence

Morphology syntax vocabulary cohesion organization register nativeness nonliteral language

Figure 3 Bachman and Palmer’s theoretical scheme of communicative competence (Bachman and Palmer, 1982)

From these theoretical points of view, communicative competence has multiple perspectives, and thus the goal of ELT is to help learners achieve these multiple abilities. Linguistic competence is only a part of it. Littlewood (1981) further explains communicative competence from the speakers’ perspective:

1. The learner must attain as high a degree as possible of linguistic competence in order to express his intended message.

2. The learner must distinguish between the forms which he has mastered as part of linguistic competence, and the communicative functions that they perform.

3. The learner must develop skills and strategies for using language to communicate meaning as effectively as possible in concrete situations.

4. The learner must become aware of social meaning of language forms. (p. 6) Littlewood still mentions the importance of linguistic competence although regards it as a tool to achieve communicative competence rather than the goal of learning.

Davies (1989) further defines communicative competence as “the use of language rules which are in part knowledge of ritual interchanges and in part control of fluency”. Linguistic competence is more emphasized here in his interpretation.

Likewise, Gumperz (1982) gives a linguistic-oriented definition to communicative competence. He defines it as “the knowledge of linguistic and related communicative conventions that speakers must have to create and sustain conversational cooperation, and thus involves both grammar and contextualization.”

In the GTM and the AA, grammatically sequenced curricula were usually used;

whereas in the Communicative Approach, achieving communicative competence becomes the main goal for ELT. The rise of Communicative Approach is the reaction against traditionally grammar-based teaching. This shift of paradigm also shows the need to pay more attention to communicative proficiency rather than mere structures and forms. The Communicative Approach is a trend that requires students engaged in real communication in the classroom setting. As Richards (2002) points out, ”The goal of language teaching is communicative competence” (p. 146).

Linguistic competence has its own value in these positions. It is a construct

independent from overall communicative competence. Politzer and McGroarty (1983) conducted a correlational study to see the communicative competence of Spanish-speaking students in bilingual education programs. Their results show that (a) low levels of linguistic competence appear incompatible with high levels of communicative competence; (b) high linguistic competence does not guarantee a high degree of communicative competence; and (c) different levels of communicative competence are possible at the same level of linguistic competence. The results suggest the tendency for high linguistic competence to correlate with high communicative competence. That points to the importance of developing linguistic competence and also the distinction between linguistic and communicative competence. That is to say, the Communicative Approach does not suggest the rejection of grammatical knowledge. As we can see from the different definition of communicative competence, grammatical competence remains a crucial element.

Features and principles of Communicative Language Teaching

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) is a method based on the Communicative Approach. With the shift of the ELT paradigm, CLT has become the most widely adopted methodology in ELT. Brown (1994) asserts:

We can look back over a century of foreign language teaching and observe the trends as they came and went. How will we look back 100 years from now and characterize the present era? Almost certainly the answer lies in our recent efforts to engage in Communicative Language Teaching. (p.3)

The primary focus in CLT, as Savignon (1990) indicates, has been “the elaboration and implementation of programs and methodologies that promote the development of L2 functional competence through learner participation in communicative events” (p.210).

Littlewood (1985) thinks one identical feature of CLT is that it systematically introduces about language functions and language structures. He claims that, “CLT is

referred to the goals of second language teaching in which teachers want to equip learners with the ability to communicate.” That is to say, CLT aims to help students build up communicative competence as well as linguistic competence. Richards and Rodgers (1986) point out that grammar should have its functional and communicative uses. That is, grammar offers help for communication to happen in the process of interaction.

These features suggested by scholars show that CLT emphasizes language

functions and communication. Meanwhile, materials and syllabuses suggested in CLT are not structure-oriented. Grammar or language form serves a supportive role or tool in achieving communicative competence. Although grammar is a distinct and crucial element in communicative competence, whether or not to teach it remains controversial in CLT. Different positions proposed by scholars are described below.

Strong version vs. weak version of CLT

Howatt (1984) thinks there is a need to take a “strong” and a “weak” line on CLT.

He explains that:

The weak version, which has become more or less standard practice in the last ten years, stresses the importance of providing learners with opportunities to use their English for communicative purposes and, characteristically, attempts to integrate such activities into a wider program of language teaching. (p.279) The “strong” (termed by Thornbury as deep-end) version of CLT assumes that linguistic knowledge is acquired through communication rather than through direct instruction. It rejects both grammar-based syllabuses and formal grammar instruction.

In his Bangalore Project, Prabhu attempts to put students in natural acquisition processes through a syllabus of task where there is no formal grammar instruction provided. This is also known as task-based learning, which requires successful completion of the task rather than successful application of a rule of grammar.

The “weak” (termed by Thornbury as shallow-end) version of CLT means

accepting the value of grammatical explanation, error correction, and drill (Nunan, 1987). As Thornbury (1999) points out, “grammar was still the main component of the syllabus of CLT courses, even if it was dressed up in a functional label: asking the way, talking about yourself, making future plans etc” (p.22). In this weak version of CLT, grammar retains its value after all. The issue is not whether to teach grammar but how to teach it. Way of grammar presentation and communicative practice are the main concerns when it comes to grammar teaching in weak CLT.

Since “meaningful principle” (Brown, 2001) is the main focus in CLT, people thus get the impression that grammar is not important, or communicative practice should be undertaken without regard for forms, while Su (2003) suggests that ELT in Taiwan is suitable for the weak version of CLT because of the EFL environment in Taiwan. He thinks at the initial stages of English learning, classroom English teaching should be focused more on grammar than communicative function. According to Savignon (1991), grammar is also important in communication and helps to achieve communicative needs. He states, “Communication cannot take place in the absence of structure or grammar, a set of shared assumptions about how language works, along with a willingness of participants to cooperate in the negotiation of meaning.” (p.268)

Empirical studies also point out the problem of strong CLT. Swain (1985) notices that although learners in the research program make impressive strides, they continued to make errors in morphology and syntax. This reveals the weakness of strong CLT. That is, the lack of form focusing on input and feedback may only lead to fluency, not accuracy. Higgs and Clifford (1982) and Hammerly (1987) argue that if learners are exposed to a natural language setting in CLT without form focusing and error correction, they would inevitably level off in target language. Moreover, they would still produce error-filled speech when learners under form-focused instruction had overcome the same types of error. Gradually, voices promoting weak CLT and

even form-focused instruction are now numerous. Celce-Murcia et al. (1991) observe that “there has been a move away from strong CLT to a weaker (more direct) version and new linguistic information is passed on and practiced explicitly”. (p.141)

Form-focused instruction

Form-focused language teaching is evidence for the weak version of CLT proposed by Long (1991). He distinguishes the traditional synthetic approach, the

“focus on forms” (Long & Robinson, 1998) from what he calls “focus on form”. He defines it as “… overtly drawing learners’ attention to linguistic elements as they arise incidentally in lessons whose overriding focus is on meaning or communication”

(p.45-46). That is to say, it attempts to draw learners’ attention to language forms but its major purpose is to provide opportunities to practice communication.

Lightbown (1992) also recognizes that it needs to be complemented with form-focused instruction of some kind in the environment of CLT. Studies of immersion programs (Genesee, 1987; Swain, 1985) show that even under ample meaning-focused instruction, learners still fail to develop high levels of grammatical or sociolinguistic competence. They suggest there is a need to focus more on linguistic form. “Learners who experience only meaning-focused instruction typically do not achieve high levels of proficiency, as measured by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages Test” (Higgs & Clifford, 1982).

By examining viewpoints offered by many scholars (Ellis, 1993; Fotos, 1993;

Fotos & Ellis, 1991; Long & Crookes, 1992; Schmidt & Frota, 1986; White, 1991), some features of form-focused instruction can be found. Error correction, consciousness-raising, and input enhancement are the mostly adopted techniques.

Error correction can make learners’ inter-language and fossilized forms become

destabilized. Consciousness-raising tasks help to draw learners’ attention to the target formal properties by providing salient positive evidence and thus facilitate leading input to intake. Input enhancement helps learners “unlearn” incorrect analyses of target language by providing negative evidence, which means information on forms that are not possible in target language (Lightbown & Spada, 1991).

Ellis (1997) points out that form-focused instruction can help bridge the gap between what they receive from input and the current state of their inter-language, and then further transfer intake into acquisition.

As emphasized by Littlewood (1981), “One of the most characteristic features of communicative language teaching is that it pays systematic attention to function as well as structural aspects of language, combining these into a more fully communicative view” (p.1), form-focused teaching reasserts the value of attention toward linguistic properties while still holding the precondition that it should be implemented communicatively. Form-focused instruction seems ideal for teachers to implement in an EFL environment since it connects the value of linguistic form and communication at the same time. Whereas some issues regarding its implementation remain vague such as the selection of pedagogical forms in the syllabus, the level of explicitness of instruction, timing, instruction treatment, etc. The former two issues provide dimensions for the researcher to examine the grammar content in target textbooks.

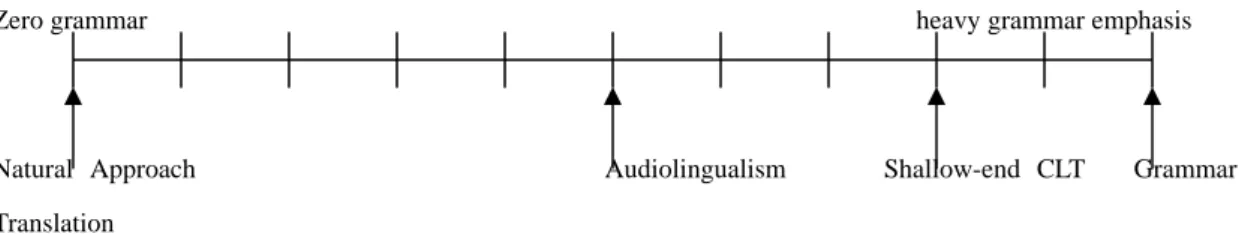

To sum up, grammar in language teaching has gone through different developmental stages with the shift of language teaching approaches. As mentioned above, the status of grammar varies in different ELT approaches. Figure 4 shows different levels of emphasis on grammar. Just as Thornbury (1999) points out, even in the strong version of CLT, where grammar instruction is rejected, there is a tendency that it has “recently relaxed its approach to grammar through recognition of the value

of a focus on form” (p.22).

Zero grammar heavy grammar emphasis

Natural Approach Audiolingualism Shallow-end CLT Grammar Translation

Deep-end CLT Direct Approach Approach

Figure 4Continuum for levels of grammar emphasis (Adopted from Thornbury, 1999, p.23)

The Role of Formal Grammar Instruction

As the role of grammar gradually regains attention, the main concern is shifting to whether explicit grammar instruction makes any contribution to language acquisition. Debates concerning the value of formal grammar instruction can be broadly divided into two sides, namely, for and against explicit grammar instruction.

Cons for grammar instruction

The position of advocating the abandonment of grammar instruction claims that form-focused instruction does not have an effect on language acquisition. Such a de-emphasis of the value of grammar instruction is harbored by Krashen’s Monitor Model and the Natural Approach proposed by Krashen and Terrell (1983). Krashen (1982) posits out that acquired knowledge is different from learned knowledge. The former is gotten through natural communication where the focus is on meaning and can be used automatically and naturally. The latter is gotten from information focusing on formal properties of language and can only be used for monitoring output.

These two kinds of knowledge cannot be transformed into each other. This assumption rejects the need for grammar instruction by positing that learned knowledge cannot be converted into acquired knowledge and be used

communicatively. Krashen and Terrell (1983) assert explicit knowledge about language does not improve linguistic fluency and consequently they propose the natural approach in language teaching. Terrel et al. (1980) investigated whether rules for interrogatives can be successfully developed by 43 classroom learners of Spanish as a foreign language without having received any explicit teaching in them. The result was that among the questions they elicited, 82% from higher-grade pupils and 74% from lower grade pupils were well formed. Prabhu (1987) argues that focusing learners’ attention on grammatical form is “unhelpful” because he thinks the knowledge for using language is too complex. He suggests that instruction should be concerned with “creating conditions for coping with meaning in the classroom” (p.2) by following a task-based syllabus.

There are two central findings of empirical research in SLA indicating that there is no effect of formal instruction. One is that language learning in formal educational contexts reveals the same developmental sequences as SLA that proceeds

“naturalistically” and formal instruction has no influence on this process (Felix, 1981;

Ellis, 1984; Lightbown, 1983). The other is that developmental sequences cannot be changed in any serious way by pedagogical intervention.

Pros for grammar instruction

There are lots of scholars who admit to the value of formal instruction in helping facilitate linguistic competence. Schmidt (1990) proposes the “noticing hypothesis” to argue that learners must be aware of the forms and their meanings in the input in order for acquisition to take place. Dekeyser (1995) and Johnson (1996) suggest that practice included in formal instruction helps convert a declarative knowledge into a procedurized one.

Fotos and Ellis (1991) use a task-based approach to teach grammar

communicatively and further develop explicit knowledge of L2 grammar through information-focused interaction. Thompson (1996) proposes a retrospective approach of grammar instruction to help teachers introduce the new language in a meaningful context. Students thus can understand the usage and meaning before focusing on the grammatical structures used to bring out the message.

Littlewood (1981) suggests that students can master some specific elements of grammar to help the processing of communicative activities. Communication happens after students integrate the pre-communicative language knowledge with existing language skills.

Hubbard, Jones, Thornton, and Wheeler (1983) agree on grammar instruction by talking about controlled and free practice. The former one gives intensive practice to new structures; the production of language is heavily controlled by the teacher to prevent errors. The latter emphasizes the free production of language.

Widdowson (1990) regards the natural acquiring of language to be a “long and rather inefficient business”. He sees the effect of language pedagogy and expresses the belief that making learners aware of formal properties of language can greatly increase the rate of language attainment.

These scholars consider that communication cannot take place in the absence of grammar instruction. Whereas they also point out that grammar instruction does not mean getting back to the traditional way but to proceed under the principles of meaningful, communicative, and task-based instruction. Just as Sandra J. Savignon (1991) states:

Grammar is important, and learners seem to focus best on grammar when it relates to their communicative needs and experiences. Nor should explicit attention to form be perceived as limited to sentence-level morphosyntactic features. Broader features of discourse, sociolinguistic rules of appropriacy, and communication strategies themselves may be included. (p.268)

Explicitness of instruction

Among approaches to grammar instruction, explicitness is one issue the researcher aims to explore in target textbook evaluation. The explicit and implicit distinction means the degree of exposure to explanation on linguistic rules during the process of acquiring grammatical competence. The explicit approach claims that learners learn to use grammatical forms under the help of explanation or example illustration, while the implicit one offers adequate exposure to target forms without explanation.

Ellis (1988) posits the essence of grammar teaching is “consciousness-raising”

(termed by Sharwood-Smith, 1981) and practice. Consciousness-raising can be explained by the degree of explicitness and elaboration in grammar teaching.

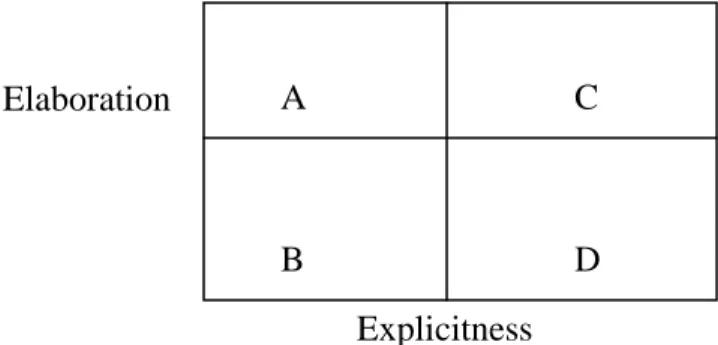

According to Sharwood-Smith (1981), explicitness refers to the extent to which the teacher makes use of the metalanguage of grammar. That is, teachers’ explanation about grammar rules, examples, or explicit hints for grammatical items. Elaboration means the amount of space and time taken up by the presentation of the rule. Using these two dimensions, Sharwood-Smith presents an explanation in Figure 5. He distinguishes four basic types of “consciousness-raising” and further points out, before judging whether formal instruction works in grammar teaching, these four types of consciousness-raising should be first considered.

Elaboration

Explicitness Explicitness

A C

B D

Figure 5 Consciousness-raising in language learning (Sharwood-Smith, 1981)

Following Sharwood-Smith’s (1981) position, the researcher thinks it necessary to look at the explicitness in the presentation of grammar activity in textbook. This dimension is more related to the present study and forms one part of the inquiry of the study; whereas elaboration depends more on the level of emphasis and time spending with techniques used by different teachers. As for the material part, the researcher will examine it by looking at the proportion of grammar content to offer some information for discussing the effect of formal instruction.

Fotos (1998) also talks about the concept of implicit and explicit grammar instruction. She thinks implicit grammatical instruction does not provide any overt mention of the target grammar point. It just provides abundant communicative materials and activities containing the target grammar point. Through learners’ access to these materials and activities, their awareness of the target grammar point can be raised. Explicit instruction, in contrast, provides a formal explanation for the target grammar point and activities practicing the correct use of it. Fotos points out that explicit instruction is necessary to promote accuracy while the implicit one is not sufficient for the EFL situation.

Similarly, Harmer (1986) talks about two kinds of grammar teaching: overt and covert. He defines covert grammar teaching as “where grammatical facts are hidden from the students”. In this kind of grammar teaching, students’ attention will be drawn to the activity or to the text and not to the grammar. Overt grammar teaching means that teacher actually provides the students with grammatical rules and explanations, and also the information is openly presented to students.

To sum up, whether or not to adopt formal grammar instruction in ELT is still in debate. As for the teaching materials, different levels of consciousness-raising and presentation of grammar included in materials serve as a reasonable viewpoint for the discussion of the effect of grammar instruction. That is why one part of the present

study aims to examine the target textbooks by looking at their presentation of grammar activity according to the concept of elaboration and explicitness.

The Communicativeness of Grammar Activity

Despite the debate on formal grammar instruction, an agreement among scholars is that language teaching should be meaningful, communicative, and task-based.

These principles are also the core value of CLT. Just as summarized by Richards (2002), “authentic and meaningful communication should be the goal of classroom activities”, communicativeness is a crucial principle for ELT activity design.

Among the seven principles that can be used for evaluating textbooks proposed by William (1983), the one for grammar part is to offer meaningful situations and a variety of techniques for teaching structural units. That means grammar should be introduced meaningfully and communicatively through different activities.

“Communicativeness” is an important criterion to evaluate grammar activities in a textbook. Grant (1987) also addresses the communicative face of grammar content in a textbook by saying that “textbooks should emphasize the communicative functions of language, not just forms”.

Activities in textbooks have the purpose of providing learners with opportunities for communication practice. Whether activities in textbooks are communicative is important because they influence how teachers conceptualize teaching and how they organize their lessons (Pan, 2004). Likewise, grammar activities also should be able to help learners achieve communicative goals. Although grammar activities are mainly designed for form-focused practice, their level of communicativeness is still important because the goal of CLT is helping learners to acquire linguistic as well as communicative competence.

Chang (2001) mentions, “The gap between linguistic competence and communicative competence is difficult to bridge, especially in the EFL environment, where the classroom is almost the only source of language.” In other words, communicativeness of grammar activity is crucial for students especially in EFL environment.

Pan (2004) conducts a study to examine the communicativeness of activities in five sets of approved tentative versions of textbooks. She adopts Dubin and Olshtain’s (1986) scale of classification, which offers a scale from 1 (the most communicative) to 7 (the least communicative). She finds that the activities in these five sets of textbooks mainly fall into the categories/ scales of 4, 5, and 6. Specifically, Textbook L has the most communicative activities. The activities she analyzes are the general activities in textbooks. But the researcher is curious about whether it is also the case in the grammar activity parts. Based on Pan’s (2004) findings, the present study further aims at grammar activities, and tries to find out if the result conforms to the one in her study. Furthermore, the target textbooks in her study are tentative versions while the present study examines the standard versions of them to see if there is any progress.

Dubin and Olshtain’s (1986) scale of communicative activities adopted in Pan’s (2004) study provides seven scales for assessing the communicative potential of activities from 1 (the most communicative) to 7 (the least communicative):

1. New information is negotiated.

2. New information is expressed.

3. New information is used or applied.

4. New information is transferred.

5. New information is received, but there is no verbal reaction.

6. No information is processed; focus is on form.

7. New information is received.

This scale offers a continuum and the activities may fall on any point of it. This scale focuses on learners’ process of dealing with new information. That is, it takes meaning and form into consideration during the dealing process of new information, but mostly, the meaning part.

While according to Thornbury (1999), the primary objective of the grammar practice activity is accuracy that refers to focusing on forms. He thinks only when accuracy is built up, learners’ focus will be shifted to meanings, namely, fluency.

VanPatten (1990) also considers it difficult to focus on form and meaning at the same time. Grammar practice needs to focus on form rather than meaning. Dubin and Olshtain’s (1986) scale is not suitable for grammar activity and thus not adopted in the present study.

Paulston and Bruder (1976) propose three categories of grammar drills - mechanical, meaningful, and communicative. They posit that these three classes can be distinguished from one another by analyzing (1) expected terminal behavior, (2) degree of response control, (3) type of learning process involved, and (4) criteria for the selection of utterance responses.

Mechanical drills completely control the response, and there is only one way of responding. In this type of activity, students don’t even need to understand the drill;

they just follow the pattern example and repeat it correctly. Paulston and Bruder (1976) further divide this type of activity into two sub-types: mechanical memorizing drills and mechanical testing drills. The purpose of the former one is to help students memorize patterns correctly, while the latter one aims not only to provide feedback for teachers but also to help students organize the information they have learned into wholes or contrasts. Paulston and Bruder (1976) further point out the ability to practice mechanical drills without necessarily understanding them is an important

criterion in distinguishing them from meaningful ones.

Meaningful drills control less than mechanical ones do, although there is still control of response in them. In this type of drill, students can express their ideas more fluently in more than one way, so this type of drill contains no more choral drilling.

Students have to fully understand the drills structurally and semantically to produce one correct answer. Although the interaction is more flexible with the increase in number of responses, the answers are still predictable by teachers. Strictly speaking, there is only some degree of meaningful information exchanged but no real communication involved.

Communicative drills offer a meaningful context related to the real world for students to communicate for problem-solving purposes. The expected terminal behavior of students is a crucial factor to distinguish meaningful drills from communicative ones. In meaningful drills, there is only automatic use of language manipulation, while in this type there is free transfer of learned language patterns to appropriate situations or contexts.

For Larsen-Freeman (1979), Paulston and Bruder’s classification provides a continuum and considers characteristics of the progression in language teaching. She also thinks it’s a process to go through these three kinds of drills when learning a new language. She mentions that at the beginning level, mechanical types of drills mainly preoccupied learning time. After becoming familiar with the target structure, learners can use it more creatively and communicatively. Paulston and Bruder’s (1976) classification targets mainly form practicing, thus the researcher adopts this scale to examine grammar activities in textbooks evaluated.

Littlewood (1981) proposes a concept of distinguishing activities between pre-communicative and communicative ones. The former asks learners to perform language fluently and appropriately but does not require them to perform it for

communicative purposes. The latter, on the contrary, deals with real communication.

He further identifies two sub-types of communicative activities: functional communication activities and social interaction activities. The former one asks learners to exchange information or solve a problem. The latter one asks learners not only to convey meaning effectively but also to pay attention to the social situations where the interaction happens. They include activities like role-plays, simulations, and conversation or discussion sessions. There is no clear dividing line between these categories and they may lead to confusion. They also deal much with the meaning part. So this scale of classification is excluded in the present study.

Considering how to tell the communicativeness of activities, Johnson (1982) also suggests five principles for communicative activities to follow:

1. The information transfer principle 2. The information gap principle 3. The jigsaw principle

4. The task dependency principle

5. The correction for content principle

To sum up, the present study adopts Paulston and Bruder’s (1976) classification to examine the communicativeness of grammar activities in five target textbook series.

The purpose is to see if their design is in accordance with the principle of CLT, namely, communicative and meaningful.

Sequencing of Grammatical Items

The principle for grammar teaching sequence in Nine-year Integrated Curriculum Guidelines is teaching the grammatical items in order from easy to difficult. Although this concept is easy to understand at first glance, the definition of

“simplicity” or “difficulty” can be controversial. There are several divergent viewpoints towards simplicity or difficulty. Larsen-Freeman (1991:220-221) summarizes these opinions as follows:

1. An audiolingual-oriented judgment is that the most difficult structure for a learner would be the most easily interfered one from his or her native language.

Thus before constructing a pedagogical sequence, a contrastive analysis should be first conducted to identify the troublesome areas.

2. Intra-lingual linguistic complexity serves a base for sequencing grammar.

Intra-lingual complexity is commonly identified from the number of transformations needed to derive the surface form of a structure. Before deciding the pedagogical order, the concept of generative grammar can offer a means of analysis.

3. A pedagogical sequence in which learners learn the structures of their native language can be a basis for a pedagogical sequence of target language. Some researchers believe that the processes of first and second language acquisition are similar. Learners can benefit if the sequence is ordered on the basis of the one in their native language.

4. Learners of ESL, regardless of the native language background, encounter difficulty on certain grammatical morphemes. A difficulty order can be established to offer a reference for a pedagogical grammar sequence.

5. Another viewpoint is on a heuristic stance. For example, regular rules are assumed easier to learn than exceptional ones. The sequence would be to teach regular past tenses before irregular ones.

6. The structures that are not widely found in other languages are emphasized when sequencing grammatical items.

7. Frequency with which native speakers of the target language use the structures

is another principle for sequencing pedagogical grammar. The assumption is that those structures that appear most are the most useful ones for learners.

8. The utility of some particular structures relevant to learners’ daily life is also a criterion.

As we can see from the divergent viewpoints mentioned above by Larsen-Freeman (1991), what an optimum grammar sequence should be like remains controversial. Since there is no one standard for deciding on a pedagogical grammar sequence, how the textbook writers select and sequence their grammatical items is an interesting question to explore. Furthermore, the topics and communicative functions they choose in a syllabus can probably result in a different order of grammatical items.

Wilkins (1976) illustrates the arrangement of content and forms in the ideal procedure of syllabus design. He states, “… the first step in the creation of a syllabus should be consideration of the content of probable utterances and from this it will be possible to determine which forms of language will be most valuable to the learner.” If the writing procedure of target textbooks in the present study reflects similar thinking as Wilkins’, one assumption can be made that the pedagogical grammar sequence among them can vary identically.

In conclusion, different viewpoints about the sequence of pedagogical grammar explain differences in textbook syllabus design on grammar. Practically speaking, the researcher expects the divergence among these target textbooks to a certain extent.

For showing the divergences by comparison, she uses the MOE textbook as a referential prototype. The MOE textbook is adopted in the present study for the following reasons:

1. The MOE textbook has been used for a long time. Although they went through several modifications due to the changes in Curriculum Standard Amendments, In ELT history in Taiwan, it has built up long-term credit and stability.

2. The grammar coverage in the List of Suggested Grammar and Sentence Structures (LSGSS) in the revised Curriculum Guidelines by the MOE in May, 2004 conforms to the grammar coverage in the MOE textbook to a great degree. LSGSS is made to provide a reference for commercial textbook writing. Therefore the grammar coverage in commercial textbooks following the Guidelines could be similar to the one in the MOE textbook.

3. Most teachers are used to the MOE textbook and get the impression and presumption that the commercial textbooks are similar to them. They mostly adopt the same teaching method as before even when they are faced with commercial textbooks now. Is it really true that there is no significant difference between grammar activities in the MOE and commercial textbooks?

Are the impressions and presumption correct? These are the questions for the researcher to answer in the present study.