國立臺灣大學管理學院會計學研究所 碩士論文

Graduate Institute of Accounting College of Management

National Taiwan University Master Thesis

新聞事件多期效果對於會計盈餘認列速度在穩健原則 下的影響性

Multi-Period Effect of Corporate News on the Speed of Earnings Recognition under Conservatism

指導教授:劉啟群 博士 Advisor: Chi-Chun Liu, Ph.D.

學生:陳苡晟

Student: Yi-Chen Chen 中華民國 102 年 6 月

June, 2013

II

I

謝辭

本論文能順利完成,首先要感謝恩師 劉啟群教授的指導。老師平時公事繁

忙,但仍然撥空指導學生論文上的疑惑以及困難,再次感謝老師細心的指導以及 鼓勵。 此外要感謝林純央助理教授對於學生論文的指導,在學生對於論文寫作 的解釋以及描述上產生困惑時,老師總是不厭其煩地對於學生提出的問題進行解 答,在此對於學姊的細心指導表達感謝。並感謝 林維珩教授以及 陳明進 教授 對於本篇論文盡心審閱本篇論文,並對於本篇論文提出諸多寶貴建議,使得本篇 論文更趨於完整,在此致上由衷謝意。

論文寫作的這段時間,感謝張明倫同學在我進行論文寫作時給予我許多幫 助。在進行解釋的同時,和明倫同學討論時經常能有許多不同的想法交流,而使 得於進行論文撰寫的時候,能對於較難以解釋的地方進行分析,並在此對於明倫 同學表達感謝。

陳苡晟 謹識 于台大會計研究所 民國 一百零貳年六月

II

論文摘要

穩健性原則影響會計上對於好消息(收入或利益)以及壞消息(費用或損失) 的認列。近年來,學者進一步將穩健性原則區分為條件性穩健和非條件性穩健 (Beaver and Ryan 2005)。Basu (1997) 使用股票報酬率以及盈餘作為變數,並 使用盈餘對於好(壞)消息認列的不對稱性對於條件性穩健進行衡量。後人並延伸 Basu (1997) 的概念對於不同性質的公司進行會計穩健性的測試。Lin and Liu (2012)根據會計穩健的性質,認為盈餘對於資訊反應的不對稱性會隨著時間經過 而減弱。因此在以不對稱性對於穩健性進行衡量時,應同時考量多期效果的概 念。

經濟事件在會計上的認列,除了依照穩健原則之外,同時也受到事件本身 認列速度的影響。本研究進一步對於各別經濟事件以事件相對認列速度進行分類,

並沿用前人所提出多期效果的概念以嘗試找出事件本身被反應速度對於穩健原 則之下盈餘認列的影響性。

實證研究證實,經濟事件本身的認列速度確實會對於盈餘認列本身產生影 響。代表除了依照穩健原則對於經濟事件進行認列之外,認列速度的增減會使得 會計上對於好消息以及壞消息之認列產生變化,並同時影響會計認列的不對稱性。

顯示前人的研究僅依照好消息以及壞消息之認列的不對稱性對於穩健性進行衡 量的方式不夠完善,而同時應該考量經濟事件本身的認列速度。

關鍵字:穩健原則、認列不對稱性

III

Abstract

Earnings recognition is long affected by conservatism. Firms tend to recognize losses earlier than gains to avoid the overstatement of asset and equity. Recently, researchers further subdivide conservatism into conditional conservatism and unconditional conservatism (Beaver and Ryan 2005). Conditional conservatism is interpreted by Basu (1997) as the lower thresholds for bad news recognition than good news recognition. Basu (1997) measures the different earnings responses to gains and losses, and defines it as conservatism. Piles of studies follow Basu (1997) measurement to test conservatism among companies with different characteristics. Lin and Liu (2012) argue that the asymmetric timeliness of earnings changes with periods (multi-period effect), because Basu (1997) only considers the asymmetric extents in current period. Empirical research shows the asymmetric timeliness is higher in short-term periods than long-term periods, and the multi-period should be considered in measuring asymmetric extents of news recognition.

News contains different recognition speed exclusive of conservatism. This research extends concept of Basu (1997) measurement and measures the effect of different relative recognition speed of news itself on earnings recognition in multi-period.

Key Word: Conservatism、Asymmetric Timeliness of Earnings

List

謝詞... I 摘要... II Abstract ... III

1. Introduction ... 1

2. Literature Review ... 4

3. Hypothesis ... 6

3.1 Multi-Period Effect in Conditional Conservatism ... 6

3.2Concept of Current Group and Future Group ... 8

3.3 Current Group and Future Group in Conservatism ... 11

3.3.1 Asymmetric Timeliness of Earnings in Current Group and Future Group in Multi-Period ... 11

3.3.2 The Magnification Effect on Asymmetric Timeliness of Earnings in Future Group ... 12

4. Data ... 15

4.1 The News Collections and Classifications ... 15

4.2 Data Collections ... 19

5. Model Design and Empirical Results ... 20

5.1 Model Design ... 20

5.2 Empirical Results ... 25

5.3 Robustness Test ... 30

6. Conclusion ... 31

Table

Table 1 News List ... 17 Table 2 Results for Effect of News on Multi-period Earnings Considering Futurity 28

Appendix

Appendix A. Categories of News ... 37 Appendix B. Descriptive Statistics ... 58 Appendix C. Results for Effect of News on Multi-period Earnings in Different

Magnitudes of Samples ... 62 Appendix D. Results for Effect of News on Multi-period Earnings in Different

Periods... 64

1

1. Introduction

Conservatism is one of the main essences of accounting. Under conservatism, firms tend to recognize losses earlier than gains to avoid overstatement of assets and equity. Until recently, conservatism is further divided into two types: the conditional and the unconditional form of conservatism. Under unconditional conservatism, which is called news-independent conservatism, firms underestimate the book value of net assets by policies determined at the initial recognition of assets and liabilities.

Conditional conservatism, also called news-dependent conservatism, is interpreted by Basu (1997) as the lower threshold for recognition of bad news than good news.

Basu (1997) first examines conditional conservatism, and employs positive (negative) returns as proxies of good (bad) news to measure the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. He implies that the linear relation between returns and earnings in concurrent period represents the extent of conservatism, because firms adopt more conservative accountings when earnings recognize news with asymmetric timeliness. Piles of studies follow Basu (1997) measurement to test conservatism among companies with different characteristics.

Basu (1997) considers only the asymmetric timeliness of earnings in concurrent period, but the asymmetric timeliness changes with periods due to different speeds of recognition of good news and bad news (multi-period effect). Lin and Liu (2012) re-examine the impact of attribute of accounting recognition on measuring the extents

2

of conservatism, and suggest that multi-period effect should be considered in Basu (1997) measurement.

Basu (1997) and Lin and Liu (2012) investigate the asymmetric timeliness of earnings, and suggest that the asymmetric news recognition is due to the different recognition speeds of good news and bad news under conservatism. Without considering conservatism, it’s natural that news itself contains different speeds of recognition, because news itself contains different information. I argue that they only capture part of conservatism, and the relative speed of recognition of news should also be considered.

To examine the speed of recognition of news itself, I classify news into Future Group and Current Group according to relative speed of recognition of news itself.

The news in Future Group is expected to be recognized more slowly than in Current Group. For example, liability issue and long-term sales agreement, such kinds of news are classified in Future Group, because firms recognize expense (revenue) of such news slowly through periods. Comparatively, if news contains disaster or one-time charge event, such news is classified in Current Group, because the expense (loss) is recognized soon in concurrent year.

I suggest that the news recognition is not only affected by conservatism, but also by relative speed of recognition of news itself. It’s expected that news in Future

3

Group is recognized more slowly than in Current Group, but due to conservatism, the speed of recognition of news might change. Firms would recognize bad news in Future Group even earlier than in Current Group under conservatism. Comparatively, firms need higher threshold, and take more time to verify information of good news in Future Group than in Current Group under conservatism. Hence, good news in Future Group is recognized later than in Current Group

I further find the difference in asymmetric timeliness between Future Group and Current Group. The information of news in Future Group is spread in longer periods, and it’s difficult to measure the information of news in future. Hence, the news in Future Group contains more uncertainties than in Current Group. It’s natural that firms recognize news with more asymmetric timeliness (i.e. more conservative) in Future Group to avoid overstatement of net income. I define the difference in asymmetric timeliness between two groups as magnification effect, and will elucidate the magnification effect in detail in the following chapter.

Considering the multi-period effect, the recognition of news alters in long-term periods. The bad news in Future Group is recognized earlier in short-term periods, and thus earnings responses to bad news decay more in Future Group than in Current Group as time periods increase. In another aspect, information of good news in Future Group is gradually recognized in long-term periods, and thus earnings responses to

4

good news in Future Group increase more than in Current Group. Due to the reverse moving directions (decrease and increase) in recognition of bad news and good news in Future Group, the asymmetric timeliness in Future Group decreases more than in Current Group in long-term periods. Hence, the magnification in Future Group decreases in long-term periods.

The rest of the thesis is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the prior literature of my study. Section 3 describes concepts of models above and the development of my hypotheses. Section 4 discusses the data. Section 5 presents the research methodology and the empirical results. Finally, I conclude my study in Section 6.

2. Literature Review

Under conservatism, firms tend to “anticipate no profits, but recognize all losses”.

Gains are recognized slowly because firms take more time to verify and recognize evidences of good news; instead, losses are recognized early due to the lower threshold under conservatism. Beaver and Ryan (2005) further classify conservatism into two types: the conditional and unconditional form of conservatism. Conditional conservatism, also called news-dependent conservatism, refers to asymmetric recognition of news in earnings, depending on favorable or unfavorable news. Under unconditional conservatism, also called news-independent conservatism, firms underestimate the book value at the initial recognitions of assets and liabilities by

5

using the accounting policy.

Basu (1997) first investigates the news-independent conservatism. He uses reverse regression to measure the asymmetric timeliness of earnings under conservatism, and employs positive (negative) returns as proxies of news. Under the hypothesis of efficient market theory, Ball and Brown (1968) suggest that information of news flows to market fast, and thus stock prices reflect the impact of news quickly.

This provides the fundamental ground for Basu (1997) to use stock returns as proxies of news to capture the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. Under conservatism, bad news is recognized earlier than good news in concurrent earnings, and the asymmetric recognition is interpreted as extent of conditional conservatism. Piles of studies later extend the concept of the asymmetric recognition, and estimate the degree of conservatism among firms with different characteristics (e.g. corporate governance schemes (Ahmed and Duellman, 2007) and countries (Ball, Robin and Wu, 2003).

In Basu (1997) measurement, he implies that the asymmetric timeliness remains constant in each period. Lin and Liu (2012) suggest that the asymmetric timeliness changes with different periods, and argue the bias in Basu (1997) measurement. Under

conservatism, the bad news is recognized earlier in short-term periods, because firms tend to pre-recognize information of bad news at ahead of time to avoid overstatement of net income. Due to the early recognition of information of bad news, the earnings

6

responses to bad news are more likely to decay in long-term periods. Comparatively, good news is recognized steadily and persistently in each period. Under the premise above, the asymmetric timeliness is more in short-term periods, but decreases as time periods increase. Lin and Liu (2012) argue that Basu (1997) measurement contains bias, because he only captures the asymmetric timeliness in concurrent period, but not considers the changes in asymmetric timeliness in multi-period (multi-period effect).

3. Hypothesis

3.1 Multi-Period Effect in Conditional Conservatism

Lin and Liu (2012) extend Basu (1997) measurement, and estimate the asymmetric timeliness changes in multi-period. Under conservatism, firms need more time to verify evidences of good news to recognize gains and revenues, but soon recognize losses to avoid overstatement of net income. Due to the different thresholds in news recognition, bad news is recognized earlier than good news in short-term periods. As time periods increase, earnings responses to bad news decay fast and even become less than good news in long-term periods. Under the premise above, the asymmetric timeliness of earnings is more in short-term period, but gradually decreases as earnings responses to bad news decay.

Lin and Liu (2012) use the following reverse model to measure the asymmetric timeliness in long-term periods.

7

Ei,t = α + α0Di,t-0 + α1Di,t-1 + α2Di,t-2 + α3Di,(t-3,t-4) + α4Di,(t-5,t-7) + β0RETi,t-0

+β1RETi,t-1 + β2RETi,t-2 + β3RETi,(t-3,t-4) + β4RETi,(t-5,t-7) + γ0RETi,t×Di,t

+γ1RETi,t-1×Di,t-1 + γ2RETi,t-2×Di,t-2 + γ3RETi,(t-3,t-4)×Di,(t-3,t-4)

+γ4RETi,(t-5,t-7)×Di, (t-5,t-7) + εi,t

RETi,t-n means stock prices difference between the starting price of year t-n and

the ending price of year t-n for firm i if n=0,1 or 2. RETi,(t-3,t-4) denotes the stock prices difference between the starting year price of year t-4 and the ending price of year t-3 for firm i. RETi,(t-5,t-7) denotes the prices difference between the starting year price of year t-5 and the ending price of year t-7 for firm i. Di,t-n, Di, (t-3,t-4) and Di, (t-5,t-7) denote dummy variable of RETi,t, RETi,(t-3,t-4) and RETi,(t-5,t-7). If RETi,t-n, RETi,(t-3,t-4) and RETi,(t-5,t-7) < 0 (bad news), Di,t-n, Di, (t-3,t-4) and Di, (t-5,t-7) equal 1; instead, Di,t-n, Di, (t-3,t-4)

and Di, (t-5,t-7) equal 0 (good news). Ei,t denotes the earnings of year t deflated by stock dividends factors and stock prices of firm i at beginning of year t.

Lin and Liu (2012) employ returns in prior periods as variables, because they measure the asymmetric timeliness of earnings by analyzing the lagged recognition of news in prior periods. Prior studies (e.g. Sloan 1993) suggest that stock returns contain both signal and noise components, and only signal contents of stock returns are informative. As information of stock returns is gradually reflected on earnings, the noises between earnings and returns increase. To mitigate the noises between earning

8

and returns, Lin and Liu (2012) employ aggregate returns in later periods, including leading three to four (RETi,(t-3,t-4)) and five to seven (RETi,(t-5,t-7)) period returns, as proxies of news.

The interactive coefficient (γn) is the difference in earnings responses (DERs) between good news (βn)and bad news (βn + γn). Positive γ indicates that earnings respond to bad news in a lager magnitude than to good news, vice versa. In multi-period, firms recognize bad news earlier than good news, and hence the DERs are more in short-term periods. As the lagged periods (time lags) increase, the DERs are supposed to decline due to the decrease in earnings responses to bad news. Hence, the coefficient γ is considered positive in short lagged periods (short-lags), but decays in long lagged periods (long-lags).

Empirical results find that the different earnings responses (DERs) are positive and more in short lags, but gradually decrease (γ0 >γ1 >γ2 > 0) as time lags increase.

DERs turn negative in γ4 and γ5, indicating the earning responses to bad news turn less than good news in long lags. The results show that asymmetric timeliness of earnings is higher in short lags, but decreases as time lags increase. Lin and Liu (2012) suggest that the multi-period effect should be considered in estimating the asymmetric timeliness in Basu (1997) measurement.

3.2 Concept of Current Group and Future Group

9

Due to different characteristics of news, firms recognize news in different speeds.

To measure the impact of relative speed of recognition of news itself in Basu (1997) measurement, I classify news into Current Group and Future Group according to relative speed of news recognition without considering the possible impact of accounting conservatism on earnings recognition. The speed of news recognition in Future Group is expected to be slower than in Current Group. Namely, the news in Future Group is recognized in longer-term periods, and the news in Current Group is recognized in shorter-term periods.

For example, the following news describes the analysis of fourth-quarter profit of Airgas Inc. Due to the cost fluctuations, Airgas Inc. might fall below the expectation of earnings. The news of cost fluctuation is soon recognized in concurrent earning, and thus such news is classified in Current Group.

“Airgas Inc. warned that its fiscal fourth-quarter profit will fall well short of expectations, because of rising fuel, health and wage costs, some related to electronic commerce initiatives and the integration of regional operations.

The news sent the shares of the Radnor, Pa., company down 27%, or

$2.1875, to $5.875 in 4 p.m. New York Stock Exchange composite trading Friday, the distributor of medical and industrial gasses said it expects earnings for the quarter ended March 31 to be between eight cents to 10

10

cents a diluted share, well below the 16 cents a share expected by analysts surveyed by First Call/Thomson Financial. In the 1999 fiscal fourth quarter, Airgas earned $8.1 million, or 11 cents a share, on revenue of $383.5 million. Excluding one-time items, the profit was 10 cents a share.” (The

Wall Street Journal, 2000/05/01)

Another example shows that AT&T Wireless will issue liabilities and preferred securities to raise capital. Such news is classified in Future Group, because AT&T Wireless will recognize interest expense and preferred stock dividends through periods.

“As part of the deal, AT&T Wireless will assume $2.1 billion in net debt plus about $221 million in preferred securities. AT&T Wireless said it will offer Tele Corp shareholders 0.9 share of AT&T Wireless stock for each share of Tele Corp. For Tele Corp, the deal caps a two-year history as a publicly traded firm. Tele Corp, which is already 23%-owned by AT&T Wireless and is one of its affiliates, has long been considered a potential takeover target for the national firm. "AT&T Wireless is the most logical exit strategy for Tele Corp," said Mike Hannon, a board member of Tele Corp and a founding investor in the firm.” (The Wall Street Journal,

2001/10/9)

11

Examples above show different speeds of recognition of news. One is recognized soon in concurrent year, and the other is recognized in long-term periods. The different speeds of recognition exist even in the same type of news (bad news or good news), and the different in speed of news recognition would affect earnings responses of good news and bad news under conservatism.

3.3 Current Group and Future Group in Conservatism

3.3.1 Asymmetric Timeliness in Current Group and Future Group in

Multi-Period

This study extends the Basu (1997) measurement and further elaborates the relative speed in Future Group and Current Group in news recognition. It’s natural that news in Future Group is recognized more slowly than in Current Group, but considering conservatism, the nature changes. Under conservatism, firms would oppositely recognize information of bad news in Future Group even earlier than in Current Group. Namely, the speed of news recognition in Future Group changes when facing bad news.

But the reverse recognition phenomenon doesn’t exist in all condition. In another aspect, good news in Future Group is expected to be recognized more slowly than in Current Group. Under conservatism, firms recognized only “realizable” and “earned”

revenues and gains. In Future Group, the information of news is spread in longer

12

periods than in Current Group, and hence firms take more time to verify evidences of good news in Future Group.

To sum up, news recognition is not only influenced by classification of good news and bad news, but also by the relative recognition speed of news itself. Basu (1997) measurement considers only different speeds of recognition of news in different types (good news or bad news), but not considers that the different speeds of news recognition even exist in the same type of news. Hence, I argue that Basu (1997) measurement only captures part of conservatism, and the different speeds of recognition of news should be considered in Basu (1997) measurement.

3.3.2 The Magnification Effect on Asymmetric Timeliness in Future Group

The classification of news in Future Group and Current Group not only affects news recognition under conservatism, but also changes the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. The information of news in Future Group is spread in longer periods than news in current group. It’s difficult to measure the information in the future, and thus the news in Future Group contains more uncertainties than the news in Current Group.

Hence, it’s natural that firms take more conservative accounting (i.e. more asymmetric timeliness) to recognize the news in Future Group than in Current Group. Namely, firms recognize bad news in Future Group earlier than in Current Group, but good news in Future Group is recognized later than in Current Group. The reverse moving

13

direction (increase and decrease) in recognition of bad news and good news magnifies the asymmetric timeliness of earnings in Future Group. I suggest that the magnification effect in Future Group is extent of conservatism.

As mentioned above, firms would take more conservative accountings (i.e. more asymmetric timeliness) to recognize news in Future Group than in Current Group because news in Future Group contains more uncertainties than in Current Group.

Under the premise, firms would pre-recognize information of bad news in Future Group in shorter-term periods than in Current Group to avoid overstatement of net income. Namely, the information of bad news in Future Group is recognized more than in Current Group in short-term periods. Hence, the earnings responses to bad news in Future Group decline faster than in Current Group as time periods increase (i.e. in long-term periods). In another aspect, firms need more time to verify the evidences of good news in Future Group, and thus good news in Future Group is recognized in longer-term periods than in Current Group. As time-periods increase, the information of good news is gradually recognized by periods, and thus the earnings responses to good news in Future Group become more than in Current Group.

Due to the different moving directions (decrease and increase) in recognition of bad news and good news in long-term periods, the asymmetric timeliness in Future Group decreases more than in Current Group. Hence, the magnification effect decreases as

14

time periods increase (i.e. in long-term periods).

In summary, the recognition of news in Future Group is expected with more asymmetric timeliness of earnings (i.e. magnification effect) in short-term periods, and the magnification effect decreases as time periods increase. I argue that Basu (1997) measurement contains bias, because he only captures the asymmetric timeliness of earnings between good news and bad news, but not considers the speed of recognition of news itself which also affects asymmetric timeliness of earnings.

In prior chapter, I describe the different earnings responses to good (bad) news in Future Group and Current Group, and measure the asymmetric timeliness in Future Group and Current Group based on conservatism measurement as following hypotheses.

H1: Bad news in Future Group is recognized earlier than in Current Group.

H2: Good news in Future Group is recognized more slowly than in Current Group.

H3.a: The recognition of news in Future Group magnifies asymmetric timeliness in

Current Group in short-term periods.

H3.b: Magnification effect of asymmetric timeliness in Future Group declines in

long-term periods.

15

4. Data

4.1 The News Collections and Classifications

Different from prior studies which employ returns as proxies of news, I collect and read 5,196 pieces of news of S&P 500 companies covering the periods between years 2000 and 2010 from The Wall Street Journal to classify news into Future Group and Current Group. Thompson II, Olsen and Dietrich (1987) classify news of The

Wall Street Journal into 12 categories depending on characteristics of news. I drop 3

categories1 of 12, which don’t affect earnings, and classify news into main 9 categories to measure the earnings responses to returns. To analyze the signal contents of news, I subdivide 9 main categories of news into subcategories to observe the contents of news in main categories.

I classify news into “Current Group” and “Future Group” from each category.

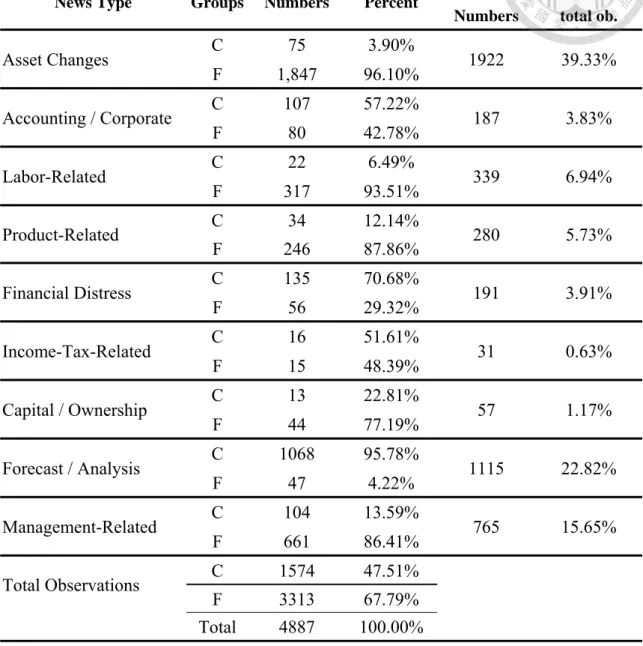

Table 1 shows 9 main categories of news, and different ratio of “C” (Current Group) and “F” (Future Group) in each category. Due to different characteristics in 9 categories, the ratio of “C” and “F” differ in all categories. For example, Asset Change consists of 96.1% “F” and 3.9% “C”, because the news in Asset Change mostly concerns future operations, and is recognized in long-term periods.

Comparatively, news in Forecast / Analysis is often classified as “C”, because the

1 Three categories include “Earnings announcement”, “dividend announcements” and “not classifiable”.

16

news in the classification is about comment on performance or changes in revenue (cost) of firms, and is soon recognized in concurrent period.

Although most news is definitely identified in “F” and “C”, some news contains obscure information and is ambiguous to be classified, and thus such news is classified into “N” to be separated from “F” and “C”. I drop the 309 pieces of N (5.9% of total news), and keep only “F” and “C” news (4,887 samples of news) in database to mitigate the bias due to subjective determination, and Appendix A presents the subcategories of news and the selected examples.

17

Table 1 News List

Panel A. Categories of New

News Type Groups Numbers Percent Total Numbers

Percent of total ob.

Asset Changes C 75 3.90%

1922 39.33%

F 1,847 96.10%

Accounting / Corporate C 107 57.22%

187 3.83%

F 80 42.78%

Labor-Related C 22 6.49%

339 6.94%

F 317 93.51%

Product-Related C 34 12.14%

280 5.73%

F 246 87.86%

Financial Distress C 135 70.68%

191 3.91%

F 56 29.32%

Income-Tax-Related C 16 51.61%

31 0.63%

F 15 48.39%

Capital / Ownership C 13 22.81%

57 1.17%

F 44 77.19%

Forecast / Analysis C 1068 95.78%

1115 22.82%

F 47 4.22%

Management-Related C 104 13.59%

765 15.65%

F 661 86.41%

Total Observations C 1574 47.51%

F 3313 67.79%

Total 4887 100.00%

Notes: The column “percent” denotes the percentage of news in “C” or “F” in the category.

18

Table 1 News List

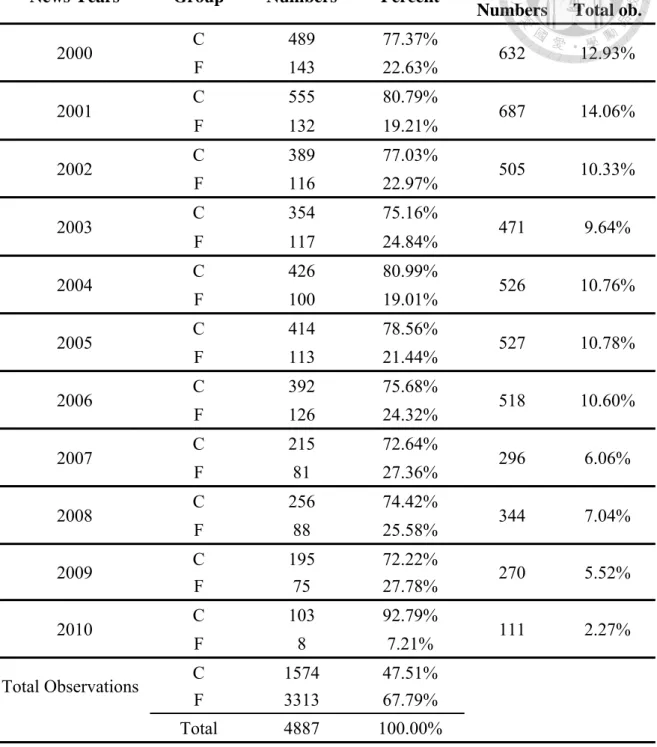

Panel B. News Divided by Year

News Years Group Numbers Percent Total Numbers

Percent of Total ob.

2000 C 489 77.37%

632 12.93%

F 143 22.63%

2001 C 555 80.79%

687 14.06%

F 132 19.21%

2002 C 389 77.03%

505 10.33%

F 116 22.97%

2003 C 354 75.16%

471 9.64%

F 117 24.84%

2004 C 426 80.99%

526 10.76%

F 100 19.01%

2005 C 414 78.56%

527 10.78%

F 113 21.44%

2006 C 392 75.68%

518 10.60%

F 126 24.32%

2007 C 215 72.64%

296 6.06%

F 81 27.36%

2008 C 256 74.42%

344 7.04%

F 88 25.58%

2009 C 195 72.22%

270 5.52%

F 75 27.78%

2010 C 103 92.79%

111 2.27%

F 8 7.21%

Total Observations C 1574 47.51%

F 3313 67.79%

Total 4887 100.00%

Notes: The panel above shows the categories of news distributions among years. The news in 2010 is less than other years, because the categories of news in 2010 consists more N than other year, so news in 2010 contains less samples than other years. From the panel above, it shows 67.8% of total news contains “F”, much higher than “C” (32.2%), because news itself provides future information to people.

19

4.2 Data Collections

As an event-study approach, I examine conservatism in an event-based data structure similar to Shroff, Venkataraman and Zhang (2013). They re-examine Basu (1997) measurement by using material three-day returns and quarterly earnings.

In my study, the annual EPS is employed as variable rather than quarterly EPS, because the news generally contains annualized information rather than quarterly information. I get year-end EPS of S&P 500 firms between the years 2000 and 2010 from COMPUSTAT, and the EPS is further deflated by stock prices at the beginning of the year to exclude the effect of stock prices fluctuation. Companies generally issue stock dividends to replace cash dividends. If firms issue stock dividends after the event date, the EPS in future periods can be diluted comparative with the current period, and hence I adjust EPS by deflating stock dividends factors. To drop the effect of outliers, the samples of EPSit and aggregate EPSit+n in the top or bottom extreme 0.5% of total samples are excluded.

The short-window returns (three-day returns) are employed in event-based approach, because annual returns might contain information of news in full year and obscure the information of specific news. I collect returns covering one day before event date to one day after event day of 4,887 samples. The holding returns represent the changes in returns caused by news during three-day periods.

20

Further, the three-day returns which are 15% greater or 15% less than median are selected and defined as material returns, and those material three-day returns are employed as proxies of good (bad) news. To avoid the effect of outlier, three-day returns fall in the top or bottom 0.5% of the distributions are excluded from samples, and the descriptive statistic results are shown in Appendix B.

5. Model Design and Empirical Results

5.1 Model Design

Lin and Liu (2012) measure the multi-period effect in reverse regression as Basu (1997), and employ multi-period annual returns as proxies of good (bad) news to measure the asymmetric timeliness of earnings. Comparatively, in the event-based approach, I measure the impact of specific news by using short-window returns as proxies of good (bad) news because the annual returns might contain information of news in whole year and obscures the information of specific news. To consider the multi-period effect, I refer to regression in Warfield and Wild (1992), who use regression to measure the explanatory power of earnings over multi-period in explaining specific returns. The following equation is to examine impact of speed of news recognition itself on news recognition and asymmetric timeliness in multi-period under conservatism (i.e. H1, H2, H3.a and H3.b).

21

RETi, t = α0Di,t + β0Ei,t + β1∑ Ei,t+n +γ0Et ×Di,t +γ1∑ Ei,t+n × Di,t

+δ0Fi,t + ζ0Fi,t×Di,t +θ0 Ei,t ×Fi,t + θ1∑ Ei,t+n ×Fi,t

+ λ0Ei,t ×Di, t× Fi,t + λ1∑ Ei,t+n ×Di,t×Fi,t

RETi,t are short-window (three-day) stock returns of firm i at year t. Ei,t are the earnings of firm i at year t, deflated by the starting stock prices of the year. ∑ Ei,t+n

are the aggregating earnings of firm i in mutli-period. I use different lengths of periods as proxies of future periods. If max n =1,2,3 or 4 , the aggregate earnings are EPSt+1, (EPSt+1 + EPSt+2), (EPSt+1 + EPSt+2+ EPSt+3) or (EPSt+1 + EPSt+2+ EPSt+3+ EPSt+4). Di,t denotes dummy variables of RETi,t, if RETi,t < 0 (bad news), Di,t equals 1;

instead, Di,t equals 0 (good news). Fi,t denotes dummy variables of Future Group, if news is classified in Future Group, Fi,t equals 1; instead, Fi,t equals 0.

To measure the news recognition in multi-period, I employ Ei,t and ∑ Ei,t+n

as proxies of earnings in current (short-term) period and in future (long-term) periods.

Aggregate earnings are employed as variable rather than multi-period earnings for two reasons. (i) The regression is to measure the recognition of news in short-term and long-term periods, rather than recognition of news in each period. (ii) As time periods increase, the noise of news in earnings-returns relation increases, but the information of news is less recognized. Hence, aggregate earnings are employed as

22

proxies to reduce the noises in the earnings-returns relation.

The information of news in Future Group is recognized in longer-term periods, and it’s difficult to measure the information in future. Hence, news in Future Group contains more uncertainties than in Current Group. Due to the uncertainties of news in Future Group, it’s natural that firms take more conservative way (i.e. more asymmetric timeliness of earnings) to recognize news in Future Group. Namely, the bad news in Future Group is recognized earlier, and the good news in Future Group is recognized more slowly than in Current Group to avoid overstatement of net income.

In the following, I measure the different earnings responses (DERs) to good (bad) news between Future Group and Current Group, and explain the changes in DERs in multi-period.

The coefficient (θ + λ) denotes the DERs of bad news between Future Group (β + θ + γ + λ) and Current Group (β + γ) in different periods. Due to uncertainties of news in Future Group, firms would pre-recognize bad news earlier than in Current Group to avoid overstatement of net income. Namely, the information of bad news in Future Group is recognized more than in Current Group in current period. Hence, the coefficient in current period (θ0 + λ0) is considered positive.

In long-term periods, the earnings responses to bad news in Future Group decay

23

more than in Current Group as time periods increase, because the information of bad news in Future Group is recognized more in short-term periods than in Current Group.

Hence, the coefficient (θ1 + λ1) would decreases and turns negative in future periods.

To test H1, I expect that DERs of bad news between Future Group and Current Group are positive in current period, and decrease in future periods.

The different earnings responses (DERs) of good news between Future Group (β+ θ) and Current Group (β) are denoted by value (θ). Firms need more time to verify the good news in Future Group, and recognize good news in Future Group in longer-term periods than in Current Group. Hence, good news in Future Group is recognized less than in Current Group in short-term periods, and the coefficient in current period (θ0) is considered negative in short-term periods.

As time periods increase, information of good news in Future Group is gradually recognized, and thus earnings responses to good news in Future Group increase in long-term periods. Comparatively, the information of good news in Current Group is recognized in shorter-term periods, and thus earnings responses to good news in Current Group gradually decay in long-term periods. Due to the increase and decrease in recognition of good news in Future Group and Current Group, the earnings responses to good news in Future Group would be more than in Current Group in

24

long-term periods. Hence, the DERs in future periods (θ1) to good news between Future Group and Current Group are considered positive. To test H2, I expect that DERs of good news between Future Group and Current Group are negative in current period, and turn positive in future periods.

It’s natural that firms take more conservative accountings (i.e. more asymmetric timeliness) to recognize news in Future Group, because the news in Future Group contains more uncertainties than in Current Group. Namely, the bad news in Future Group is recognized earlier, and the good news in Future Group is recognized more slowly than in Current Group to avoid overstatement of net income. The reverse moving direction (increase or decrease) in recognition of bad news and good news magnifies the asymmetric timeliness in Future Group in short-term periods. The asymmetric timeliness of earnings in Future Group (γ+ λ) would be more than in Current Group (γ) in current period. I define the difference in asymmetric timeliness of earnings in Future Group and Current Group as magnification effect. To test H3.a, I expect that magnification effect (λ0) in Future Group is positive in current period.

Considering the multi-period effect, the magnification effect in Future Group decays in future periods. The information of bad news in Future Group is recognized more in short-term periods. Hence, the earnings responses to bad news decay more in

25

Future Group than in Current Group in long-term periods. In another aspect, information of good news in Future Group is gradually recognized in long-term periods, and thus the earnings responses to good news in Future Group are more than in Current Group. Due to the increase and decrease in recognition of good news and bad news in Future Group, the asymmetric timeliness in Future Group decreases more than in Current Group. To test H3.b, the magnification effect (λ1) in Future Group is expected to decrease compared with λ0.

5.2 Empirical Results

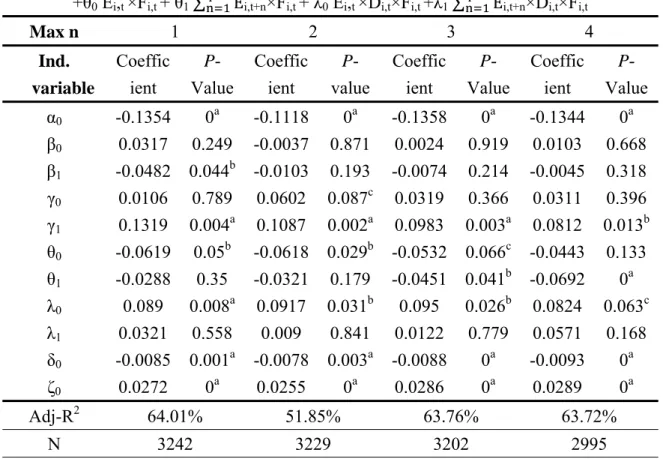

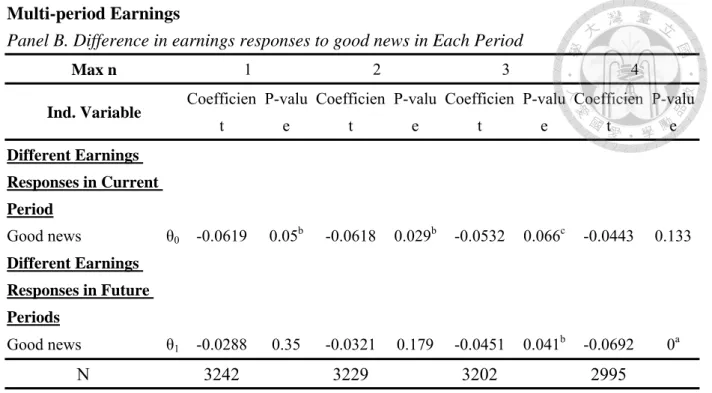

My main results are shown in Panel A, Table 2, and the coefficients of each variable are shown above in four lengths of periods. To simplify the coefficient listed in Panel A and analyze the different earnings responses (DERs) of good (bad) news, the incremental coefficients in current period and future periods are listed in Panel B.

Panel B shows the different earnings responses to bad news between Future Group and Current Group. The DERs of bad news between two groups are positive in current period (θ0 + λ0), denoting that bad news in Future Group is recognized earlier than in Current Group in current period. In future periods, DERs of bad news between Future Group and Current Group in future periods (θ1+ λ1) are positive in shorter-term periods (max n=1), and turn negative in longer-term periods (max n=2, 3 or 4). The

26

results show that information of bad news in Future Group is still recognized more than in Current Group next year, and is recognized less than in Current Group as time periods increase. These results are consistent with H1.

The different earnings responses (DERs) of good news between Future Group and Current Group (θ0) in current period are shown in Panel A. The value of θ0 is negative and statistically significant in current period. This indicates that good news in Future Group is recognized less than in Current Group in current period, consistent with H2. In future periods, the DERs of good news between Future Group and Current Group (θ1) remain negative, inconsistent with H2. Under conservatism, good news in Future Group is recognized in longer periods than in Current Group, but due to constraints2, the time lengths in regression are only up to five years. Hence, the good news in Future Group might not be fully recognized in five years, but is reflected in longer periods.

Due to different speeds of recognition of good (bad) news in Future Group and Current Group, it’s suggested that the asymmetric timeliness of earnings is different in Future Group and Current Group. The following paragraph measures the difference in asymmetric timeliness between Future Group and Current Group in current period and future periods. The empirical results are shown in Panel A, Table 2.

2 To avoid data missing due to long lags, I refer to Lin and Liu (2012), and adopt the time lags (5 years), containing more signal contents of news.

27

The results show the bad news in Future Group is recognized in even faster pace than in Current Group, and earnings responses to bad news in Future Group are more than in Current Group in current period (θ0 + λ0). In another aspect, good news in Future Group is recognized in slower pace than in Current Group, and thus earnings responses to good news in Future Group are less than in Current Group in current period (θ0). Such reverse moving directions (increase or decrease) in recognition of bad news and good news magnify the asymmetric timeliness in Future Group. The difference in asymmetric timeliness (λ0) between Future Group (γ0 + λ0) and Current Group (γ0) remains positive and statistically significant, indicating that the magnification effect exists in Future Group in current period. The results are consistent with H3.a.

As mentioned above, the results show the good news in Future Group is still recognized less than in Current Group after 4 years from current period (θ1). But due to more decay in earnings responses to bad news in Future Group than in Current Group (θ1 + λ1), the asymmetric timeliness in Future Group decays more than in Current Group in long-term periods. Hence, the magnification effect in Future Group in future periods (λ1) still exists but decreases. The results are consistent with H3.b.

28

Table 2 Results for Effect of News in “Future Group” and “Current Group” on Multi-Period Earnings

Panel A. Choosing Positive (Negative) 35% Samples of 3-Day Return and Using 3 Day Return

RETi, t = α0Di,t + β0 Ei,t + β1∑ Ei,t+n +γ0 Ei,t ×Di,t +γ1 ∑ Ei,t+n× Di,t +δ0Fi,t + ζ0Fi,t×Di,t

+θ0 Ei,t ×Fi,t + θ1 ∑ Ei,t+n×Fi,t + λ0 Ei,t ×Di,t×Fi,t +λ1∑ Ei,t+n×Di,t×Fi,t

Max n 1 2 3 4

Ind.

variable

Coeffic ient

P- Value

Coeffic ient

P- value

Coeffic ient

P- Value

Coeffic ient

P- Value α0 -0.1354 0a -0.1118 0a -0.1358 0a -0.1344 0a β0 0.0317 0.249 -0.0037 0.871 0.0024 0.919 0.0103 0.668 β1 -0.0482 0.044b -0.0103 0.193 -0.0074 0.214 -0.0045 0.318 γ0 0.0106 0.789 0.0602 0.087c 0.0319 0.366 0.0311 0.396 γ1 0.1319 0.004a 0.1087 0.002a 0.0983 0.003a 0.0812 0.013b θ0 -0.0619 0.05b -0.0618 0.029b -0.0532 0.066c -0.0443 0.133 θ1 -0.0288 0.35 -0.0321 0.179 -0.0451 0.041b -0.0692 0a λ0 0.089 0.008a 0.0917 0.031b 0.095 0.026b 0.0824 0.063c λ1 0.0321 0.558 0.009 0.841 0.0122 0.779 0.0571 0.168 δ0 -0.0085 0.001a -0.0078 0.003a -0.0088 0a -0.0093 0a ζ0 0.0272 0a 0.0255 0a 0.0286 0a 0.0289 0a

Adj-R2 64.01% 51.85% 63.76% 63.72%

N 3242 3229 3202 2995 Notes: RETi,t means short window(3-day) stock return of firm i at year t. Eit indicates the

earnings of firm i at year t deflated by starting stock price of year t . ∑ Eit+n mean the aggregate EPS of firm i at future periods. Eit+n are each deflated by starting stock price of year t+n, and the stock dividend factors. In this model, I drop the 3-day return samples fall in median

±15% to capture the effect of one piece of news on multi-period earnings. To eliminate the effect of outliers, I separately drop 1% of outliers in 3-day return. Eit and ∑ Eit+n.A superscript of

‘a’,’b’ or ‘c’ indicates that result is significant at 0.01,0.05 and 0.1 level in a one-tail test if the coefficient has the predicted sign.

29

Table 2 Results for Effect of News in “Future Group” and “Current Group” on Multi-period Earnings

Panel B. Difference in earnings responses to good news in Each Period

Max n 1 2 3 4

Ind. Variable Coefficien t

P-valu e

Coefficien t

P-valu e

Coefficien t

P-valu e

Coefficien t

P-valu e Different Earnings

Responses in Current Period

Good news θ0 -0.0619 0.05b -0.0618 0.029b -0.0532 0.066c -0.0443 0.133 Different Earnings

Responses in Future Periods

Good news θ1 -0.0288 0.35 -0.0321 0.179 -0.0451 0.041b -0.0692 0a

N 3242 3229 3202 2995

Notes: Panel C. shows the difference in earnings responses between Future Group and Current Group.

The difference between incremental coefficients shows asymmetric timeliness of good news in two groups. A superscript of ‘a’,’b’ or ‘c’ indicates that result is significant at 0.01,0.05 and 0.1 level in a one-tail test if the coefficient has the predicted sign.

Panel C. Difference in earnings responses to bad news in Each Period

Max n 1 2 3 4

Ind. Variable Coefficien t

P-valu e

Coefficien t

P-valu e

Coefficien t

P-valu e

Coefficien t

P-valu e Different Earnings

Responses in Current Period

Bad news θ0+λ0 0.0271 0.41 0.03 0.4076 0.0418 0.2344 0.0381 0.2636 Different Earnings

Responses in Future Periods

Bad news θ1+λ1 0.0032 0.94 -0.0231 0.5572 -0.033 0.4029 -0.0121 0.7693

N 3242 3229 3202 2995

Notes: Panel C. shows the difference between incremental coefficients shows asymmetric timeliness of bad news in two groups. A superscript of ‘a’,’b’ or ‘c’ indicates that result is significant at 0.01,0.05 and 0.1 level in a one-tail test if the coefficient has the predicted sign.

30

Table 2 Results for Effect of News in “Future Group” and “Current Group” on Multi-period Earnings

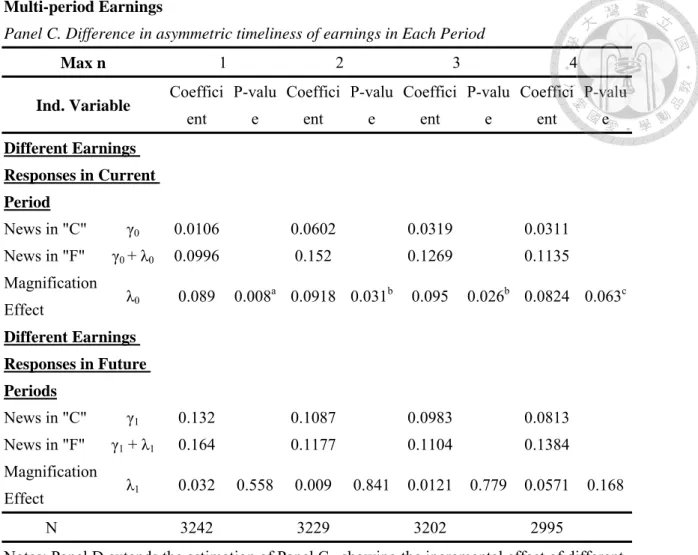

Panel C. Difference in asymmetric timeliness of earnings in Each Period

Max n 1 2 3 4

Ind. Variable Coeffici ent

P-valu e

Coeffici ent

P-valu e

Coeffici ent

P-valu e

Coeffici ent

P-valu e Different Earnings

Responses in Current Period

News in "C" γ0 0.0106 0.0602 0.0319 0.0311 News in "F" γ0 + λ0 0.0996 0.152 0.1269 0.1135 Magnification

Effect λ0 0.089 0.008a 0.0918 0.031b 0.095 0.026b 0.0824 0.063c Different Earnings

Responses in Future Periods

News in "C" γ1 0.132 0.1087 0.0983 0.0813 News in "F" γ1 + λ1 0.164 0.1177 0.1104 0.1384 Magnification

Effect λ1 0.032 0.558 0.009 0.841 0.0121 0.779 0.0571 0.168

N 3242 3229 3202 2995

Notes: Panel D extends the estimation of Panel C., showing the incremental effect of different kinds of news s. I use the incremental coefficient to estimate the asymmetric timeliness of different kinds of news recognition. A superscript of ‘a’,’b’ or ‘c’ indicates that result is significant at 0.01,0.05 and 0.1 level in a one-tail test if the coefficient has the predicted sign.

5.3 Robustness Test

The results are robust under standard of different magnitudes of returns besides positive (negative) extreme 35% of total observations. Other magnitudes of samples, such as positive (negative) extreme 30% and 25% of total samples, are adopted to measure the validity in my study. The results are robust as shown in Appendix C. Further, to measure if the result is consistent in different years, I further subdivide the samples in 3 periods, inclusive of 2000~2003, 2004~2007 and 2008~2010. The results are robust as shown in Appendix D.

31

6. Conclusion

The paper extends Basu (1997) measurement, and further examines the relative recognition speed of news itself in extent of conservatism. Basu (1997) first investigates the conditional conservatism, and employs positive (negative) returns as proxies of good (bad) news. Under conditional conservatism, firms recognize bad news earlier than good news.

Hence, he suggests that the different earnings responses (DERs) to the news are extent of conservatism.

Basu (1997) considers only the asymmetric timeliness of earnings in concurrent period, but the earnings responses to good (bad) news change in each period. Lin and Liu (2012) find that asymmetric timeliness changes in each period (multi-period effect), and suggest that multi-period effect should be considered in measurement of conservatism.

The main empirical research in the paper is to measure relative recognition speed of news itself in asymmetric timeliness under conservatism. Basu (1997) and Lin and Liu (2012) measure the different speeds of news recognition between good news and bad news, but they don’t consider the relative recognition speed of news itself. The difference in speed of news recognition exists even in the same type of news (good news or bad news), and affects the news recognition under conservatism.

To measure the impact of speed of recognition of news itself, I classify news into Future Group and Current Group. The news in Future Group is expected to be reflected in longer-term periods than in Current Group. But it’s difficult to measure the information in

32

future periods, and thus the news in Future Group contains more uncertainties than in Current Group. Hence, Firms take more conservative accountings (i.e. more asymmetric timeliness) to recognize news in Future Group. Namely, firms take more time to verify the good news, but pre-recognize bad news in shorter-term periods to avoid overstatement of net income in Future Group. Due to the uncertainties of news in Future Group, the asymmetric timeliness in Future Group is magnified more than in Current Group. I argue that Basu (1997) measurement only captures part of conservatism, and the different recognition speeds of news itself should also be considered.

Furthermore, I argue that Lin and Liu (2012) measurement should consider the concept of speed of news recognition itself to capture full conservatism. Considering the different speeds of news recognition itself, the recognitions of bad news and good news alter in each period. Firms recognize more information of bad news in Future Group in short-term periods, and thus the earnings responses to bad news in Future Group decay in faster pace than in Current Group. In another aspect, information of good news in Future Group is recognized in longer-term periods than in Current Group. Namely, the earnings responses to good news in Future Group is more than in Current Group in long-term periods. Due to the different moving directions (decrease and increase) in earnings responses to bad news and good news, the magnification effect of asymmetric timeliness decays in long-term periods. It’s suggested that when measuring extent of conservatism, the news should be compared in the same group and the same period. Otherwise, the asymmetric timeliness of earnings might contain bias

33

due to magnification effect in Future Group in multi-period.

There are some limitations in my research. First, I collect earnings data of S&P 500 firms between years 2000-2010.Firms recognize gain and loss depending on the accounting system, but the accounting system might alter with periods. Hence, the changes in accounting system might cause the data of earnings in my research loss consistency. Second, the earnings data is collected from WRDS. Although I get the complete and audited earnings data of S&P 500 firms, it’s difficult to ascertain that firms don’t make fraud or accounting mistakes in financial statement. Hence, the limitation in correctness of earnings data might affect my research.

The following lists some suggestion in my research. First, it’s difficult to diagnose the pure “Current Group” and “Future Group” in real world. To measure the speed of recognition of news in Basu (1997) measurement, I classify the news directly into “Current Group” and

“Future Group”, but I don’t further measure the degree of speed of news recognition in samples. The later studies may further measure “Current Group” and “Future Group” by the degree of relative news recognition speed. The second suggestion is that three-day returns and annual earnings are employed as variables to capture the earnings-returns relation in multi-period in my study. Due to the difference in daily and annual information, there might contain noise between short-window returns and annual earnings. Employing short-term earnings might mitigate the noise between short-windows returns and earnings, but annual earnings are employed due to annualized news data. Though I still captured the relation

34

between long-term period earnings and returns, but if it’s possible, I suggest that the later studies would adopt quarterly earnings for specific news to reduce the noise between short-window returns and yearly earnings in multi-period.

35

Reference

Ball, R. and P. Brown, 1968. An empirical evaluation of accounting income numbers.

Journal of Accounting Research 6: 159-178.

Basu, S., 1997. The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings.

Journal of Accounting and Economics 24: 3-37.

Basu, S., 2005. Discussion of Conditional and Unconditional Conservatism:Concepts and

Modeling Review of Accounting Studies 10: 311-321.

Beaver, W. H., R. A. Lambert, and S. G. Ryan, 1987. The information content of security prices: a second look. Journal of Accounting Research 9: 139-157.

Beaver, W. H. and S. G. Ryan, 2005. Conditional and unconditional conservatism:

concepts and modeling. Review of Accounting Studies 10: 269-309.

Lin, C. Y. and C. C. Liu, 2012. Effects of nonlinearity and multi-period lags on Basu (1997) measure. Journal of Financial Studies 20: 1-32.

Shroff, P. K., R. Venkataraman, and S. Zhang, 2013. The conservatism principle and the asymmetric timeliness of earnings: an event-based approach. Contemporary Accounting

Research 30: 215-241.

Thompson II, R. B., C. Olsen, and J. R. Dietrich, 1987. Attributes of news about firms: An analysis of firm-specific news reported in the Wall Street Journal Index. Journal of

Accounting Research 25: 245-274.

36

Warfield, T. D. and J.J Wild. 1992. Accounting recognition and the relevance of earnings as an explanatory variable for returns. The Accounting Review 4:821-842

Watt, R. L. 2003a. Conservatism in accounting part I: Explanations and implications

Accounting Horizons 17:207-221

37

Accounting Mistakes C 55

Tyco International Ltd. is investigating allegations of "improper" payments made by a non-U.S. subsidiary. Without disclosing the location of the unit, Tyco said the alleged misconduct took place from 1999 to 2003, according to a Securities and Exchange Commission filing. The Bermuda-based conglomerate said it is also trying to determine whether the payments were correctly recorded in the subsidiary's books.

Appendix

Appendix A. Categories of News Panel A. Accounting / Corporate

Description of News Categories: The changes in companies’ accounting system, fiscal year and corporate by laws The category contains 187 samples (including 80 “F” and 107 “C”)

News Type Group N Example

Accounting Principle

change F 39

BB&T Corp.'s second-quarter net income fell 3.3%, hurt by a lease- accounting adjustment, though the Winston-Salem, N.C., bank-holding company said core operations benefited from growth in loans and fees and improved credit quality. BB&T reported net of $386.8 million, or 70 cents a share, compared with $400.1 million, or 72 cents a share, a year earlier. The latest quarter included a charge of $26.6 million, or five cents a share, related to property and equipment leases.

Accounting Fraudulence C 22

A former Bank of America Corp. executive alleged in an arbitration filing that the bank used "creative accounting" in booking financial losses and that executives were

inappropriately ordered to make charitable and political contributions at the behest of the bank. The allegations are part of a claim filed yesterday by former Bank of America executive Duncan Goldie-Morrison with the National Association of Securities Dealers, which hears employment claims and other disputes in the securities industry. Until March, Mr. Goldie-Morrison was one of the highest-ranking executives at the bank's corporate- and investment-banking division. He ran the debt-raising business for bank clients foreign- exchange products and fixed-income research.

38

F 5

NEW YORK -- Avon Products Inc., the big direct seller of cosmetics and jewelry, said the Securities and Exchange Commission is investigating a $10 million charge the company took in 1999 related to the write-off of computer software. The company "firmly believes that it was properly treated as a special charge," said Brian Martin, an Avonspokesman. "It appears to us that the SEC may be questioning more the size -- whether it should have been a larger or a smaller charge -- and the timing of the charge.

Accounting Policies (of corporation)

C 6

Tenet has struggled since disclosing in October that its once-robust growth depended largely on outlier payments. The payments are intended to offset the cost of treating the sickest patients, but Tenet's use of them effectively gouged the Medicare system. Stop-loss payments serve a similar function for private insurers. The disclosure triggered a

management shake-up, a change in the company's billing policies, various government investigations and sharply reduced earnings forecasts.

F 10

AOL Time Warner Inc. will reclassify $1.5 billion of its mandatory convertible preferred stock issued to Comcast Corp. as liabilities, reducing shareholder equity. The New York media conglomerate said the reclassification in the quarter ending Sept. 30 is required to comply with a new accounting rule. The rule, FAS 150, mandates that an issuer classify certain financial instruments as a liability, or an asset in some circumstances.

Accounting Disputes

Settlement C 24

Citigroup Inc. agreed to settle a lengthy federal investigation into its accounting of

Argentina bonds during the debt crisis earlier this decade, a move that will resolve another of the bank's outstanding legal issues. In reaching the settlement with the Securities and Exchange Commission, Citigroup agreed to cease and desist from future securities-law violations, a relatively light sanction. The SEC alleged Citigroup failed to keep accurate books and records and didn't maintain sufficient internal controls over accounting.

39

F 5

Wall Street has a lot riding on the financial industry's effort to ease frozen credit markets by creating an $80 billion rescue fund -- but no company more than Citigroup Inc.

Supporting these off-balance-sheet funds, known as structured investment vehicles or SIVs, is the heart of the rescue effort led by Citigroup, J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. and Bank of America Corp. Accounting groups have raised the question of whether Citigroup and other managers of the SIVs should account for the funds, many of which face potential losses, on their own balance sheets.

Other Information F 6 Audit Regulation

F 15 Corporate Bylaw