1 School and Graduate Institute of Physical Therapy, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan 2 Department of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

3 Department of Surgery, National Taiwan University and Hospital

4 Physical Therapy Center, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan

* Corresponding author: Jau-Yih Tsauo, Graduate Institute of Physical Therapy, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University,

Floor 3, No. 17, Xuzhou Rd., Zhongzheng District, Taipei City 100, Taiwan, ROC Tel: 886-2-33668130 E-mail: jytsauo@ntu.edu.tw

Received: March 31, 2010 Revised: May 4, 2010 Accepted: May 11, 2010

The Effect of Decongestive Lymphatic Therapy with

Pneumatic Compression for

Breast Cancer-related Lymphedema

Han-Ju Tsai

1Hsiu-Chuan Hung

1Jing-Lan Yang

2Chiun-Sheng Huang

3Jau-Yih Tsauo

1,4,*Background and Purpose: Many investigators measured treatment effectiveness of

deconges-tive lymphatic therapy (DLT) combined with pneumatic compression (PC). However, most of

them did not use controls. Objectives: This study aimed to investigate the effectiveness of this

management using the subjects themselves as controls to minimize the influence of spontaneous

change with time. Methods: Subjects with unilateral breast cancer-related lymphedema were

recruited. Each subject went through a control period, an intervention period and three

measure-ments. They were treated with DLT combined with 1-hour PC for 2 hours/session, one session/

day, 5 sessions weekly for 4 weeks. The outcome measures included demographic and medical

information, the severity of swelling, water composition, lymphedema-related symptoms,

qual-ity of life and subjects’ compliance. One-way repeated measures and Friedman tests were used

to examine the differences among three evaluations. Results: There was no significant change

in all of the measurements in the control period. Significant reductions in excess water

displace-ment, excess circumference, excess water composition (p<0.0083) and 5 symptoms after

inter-vention (p<0.0167). Conclusions: The use of DLT combined with PC in treating patients with

lymphedema has shown positive therapeutic responses. (FJPT 2010;35(2):89-97)

Key Words: Breast cancer, Breast cancer-related lymphedema, Decongestive

lymphatic therapy, Lymphedema, Pneumatic compression

Breast cancer-related lymphedema is a common complica-tion occurs through the course of treatments for breast cancer.

It is defined as arm edema in the breast cancer patient is caused by interruption of the axillary lymphatic system by surgery or

radiation therapy, which results in the accumulation of fluid in subcutaneous tissue in the arm, with decreased distensibility of tissue around the joints and increased weight of the extremity.1

According to the survey of Motimer et al., fourth of breast can-cer patients suffered from lymphedema,2 which causes physical,

psychological, and functional impacts and increases the risk of repeated superficial infections.3,4

Decongestive lymphatic therapy (DLT), is also known as complex decongestive therapy, complex lymphedema therapy, multimodel physical therapy, complex decongestive physio-therapy, and complete decongestive physical therapy.1 It is a

comprehensive multidisciplinary lymphedema therapy, has been recommended as a primary treatment by consensus panels and is an effective therapy for lymphedema unresponsive to standard elastic compression therapy. It consists of skin care, manual lymphedema drainage (MLD),5 compression wrapping,6

exercises,7 and followed by maintenance program and

psycho-social rehabilitation.1 Pneumatic compression (PC) is a

me-chanical method to deliver compression to the swollen limbs. It is often combined with DLT to treat patients with breast cancer-related lymphedema.8 Although the use of PC is extensive, the

optimum parameters have not been determined. Some research-ers do not support the use of PC because pressure greater than 50-60 mmHg might injure superficial lymphatic vessels.9 Other

experts support the use of PC, generally suggesting the use of a lower pumping pressure (40 mmHg) as part of a comprehensive program.3,10 It concluded that when DLT is used adjunctively

with pneumatic compression therapy, it enhanced the therapeu-tic response.8

Many studies aimed at measuring effectiveness of DLT or combination of its subsets.7,8,10-17 Most studies were

quasi-experimental designs without real control groups (no treat-ment at all) because once the lymphedema was established, the symptoms had an inexorable tendency to progress,18 and

provision of treatment was necessary. Therefore, conducting a standardized, randomized controlled trial is difficult under ethical consideration. Erickson et al. pointed out that numerous studies focus on the efficacy of DLT, but all were cohort studies that evaluated patients before and after therapy.19 Only tentative

conclusions should be drawn from these studies.

Therefore, we have modified the study design by using the subjects themselves as controls, and aim to investigate the effectiveness of DLT when combined with PC.

METHODS

Study Design

A prospective study design with a 4-week control period (the first month) followed by a 4-week intervention period (the second month) was administered. Subjects maintained ordinary management for their lymphedema throughout the whole study period. The ordinary management is defined as the management that subjects received and did concurrently in the hospital such as pneumatic compression and self management at home such as elevation or MLD. The study protocol was approved by the hospital ethics committee and all participants provided written consent.

Subjects

Subjects were referred from hospitals, foundations and associations from August 2004 to June 2005. These organiza-tions are around the Taipei area and serve patients with breast cancer. Those who fulfilled the following criteria were eligible for the study: 1) unilateral breast cancer-related lymphedema for at least 3 months, 2) moderate to severe lymphedema (excess circumference of the affected limb larger than 2 cm at least on one measured site).20 The exclusion criteria were as follows:

1) active cancer or disease that might lead to swelling, or on diuretic therapy or other lymphedema-influencing drugs, 2) port-A catheter on chest wall of affected side with adhesion, 3) skin disease, 4) irremovable bracelet or ring on affected upper extrimities, 5) the restriction of active range of motion in af-fected upper extremity was greater than half range.

Sample Size Estimation

Based on previous studies which had similar interven-tion,8,13,15 the effect sizes for limb volume reduction of these

re-search were 0.46,8 1.15,13 1.20,15 the estimated sample size was

8, 8, and 39 respectively when setting a power of 80%, and an α of 5% was used to detect any difference between groups. The intervention in the current study was a combination of interven-tions of those studies. So we averaged the estimated sample size calculated from the data of these three studies. The average of the estimated sample size was 18.

Interventions

educa-tion for skin care, 2) a 30-minute manual lymphatic drainage (MLD), 3) 1-hour of pneumatic compression therapy (at 40 mm Hg) (Lympha-Mat, German), 4) short-stretch bandage applica-tion (Rosidal® K, German), and, 5) 20-minute remedial exer-cises. Subjects were treated two hours per session, one session per day, five days weekly for 4 weeks (20 sessions of treatment in total).

MLD treatments were performed by four certified physi-cal therapists (PT) following a procedure that drain the anterior trunk firstly, followed by drainage of the posterior trunk and affected arm. To make sure all the therapists offered similar massage pressure on patient, all the therapists experienced the massage pressure by setting a sphygmomanometer cuff on their own arms and practiced massage on their arms at the same time before commencement of this research. A gradient-sequential pneumatic pump (Lympha-Mat, German) with a twelve cham-bers sleeve was used for pneumatic compression therapy.

A short-stretch bandage was applied to the treated arm by the physical therapist after MLD and PC. The technique of ap-plying the short-stretch bandage was also taught to the patients and/or their family in case they needed to re-apply it such as after bathing or intolerance of the pressure. We instructed all subjects to wear the bandage as long as possible.

After the bandage was applied, subjects then commenced exercises. The 20-minute exercise program included relaxation exercises, breathing exercises, and manual lymphatic drainage exercises.7 Patients were instructed to execute exercise at least

twice per day at home.

Outcome Measures

All data were collected by one licensed PT. Three evalu-ations were carried out. The first was at the beginning of the control period. The second was at the transition between the control and intervention periods, and the third was at the end of the intervention period. Baseline and demographic data were recorded for each subject at the first evaluation, which included: 1) history of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, 2) surgery type, 3) number of excised lymph nodes, 4) post-operation duration, 5) time of lymphedema onset, 6) previous and concurrent treat-ment for lymphedema (Table 1.).

Limb size

Water-displacement volumetry and circumference

mea-surement were used to quantify limb size. Water-displacement is a simple and direct method to measure the volume of ir-Table 1. Characteristics of Patients

Items

Mean±SD [median]

Age 57.9±9.8

Body Mass Index 24.5±3.9

Average dose of radiotherapy

(cGy) 3938±2261 [5000]

Number of dissected lymph

nodes 18.4±4.6 [18.5]

Post-op duration (months) 68.2±60.9 [53.5] Lymphedema duration (months) 26.3±28.8 [16.5] Number (percentage) Subjects underwent radiotherapy 15 (83.3%) Subjects underwent

chemothera-py 16 (88.9%)

Surgery type

Radical mastectomy 1 ( 5.6%)

Modified radical mastectomy 13 (72.2%)

Simple mastectomy 1 ( 5.6%)

Breast conservation 3 (16.7%)

Lymphedema on dominant side 11 (61.1%) Previous treatment for

lymph-edema 17 (94.4%)

Pharmacologic treatment 3 (16.7%)

Manual lymphatic drainage 8 (44.4%)

Short-stretched bandage 0 ( 0.0%)

Elastic bandage 5 (27.8%)

Compression garment 10 (55.6%)

Remedial exercise 1 ( 5.6%)

Pneumatic compression

ther-apy 17 (94.4%)

Other physical therapy

mo-dality 6 (33.3%)

Chinese pharmacologic

treat-ment (herbal treattreat-ment) 2 (11.1%)

Chinese massage (heavy

ma-neuver) 1 ( 5.6%)

Concurrent treatment for

regular limbs.8,12,16,21,22 The limb was vertically immersed in a

water-filled tank until the web space between index and middle fingers touched a bar across the tank, and the displaced fluid was collected and measured by measuring cups (3000 c.c. and 5000 c.c.) and cylinders (100 c.c.) with various volume and graduated scale. The value of each scale were 50 c.c. for mea-suring cups and 1 c.c. for the cylinder. The measurement of water-displacement was conducted twice for each limb and the average data was used to analyze. The circumference of both arms was also measured, starting from the wrist and measured every 3 cm proximally to the axilla. We calculated the average circumference of the whole arm and specific parts of the arm by averaging the individual circumferences of the whole upper extremity, the upper half of the upper arm, the lower half of the upper arm, and the forearm. If there were n above-elbow circumference measurements, the upper n/2 measurements were used in calculation of the circumference of the upper half of the upper arm; the other n/2 circumference measurements were used for circumference of the lower half of the upper arm. If there were an odd number of above-elbow circumference measurements, the upper (n+1)/2 circumference measurements were used for the upper half of the upper arm. According to the previous studies, both the inter-rater and intra-rater reliability of water displacement measurement and circumference mea-surement were high (r = 0.99).23,24

Water composition of the upper extremity

Water composition represents the volume percentage of water in the upper extremity. Too much water content repre-sents the edema. Decreased excess water composition means improvement after intervention. An eight-polar tactile-electrode impedance meter (Inbody 3.0, Biospace, Seoul, Korea) was used for the water composition analysis. Resistance (R) of the arms, trunk, and legs could be measured and reported respec-tively. According to Bedogni’s study, the coefficients of varia-tion calculated from repeated measurement were 1.7~2.8% for all segments and frequencies. The validity study of Inbody has been conducted using deuterium oxide dilution as the gold standard of body water measurement. There was a significant correlation between the total body water estimated by Inbody and by deuterium oxide dilution.25

Lymphedema-related symptoms

Researchers have described various physiological symp-toms associated with lymphedema. Williams et al. used 11 lymphedema-related symptoms to evaluate the effects of in-tervention.14 We revised the outcome variables from Williams’

study after discussion with seven lymphedema patients and three experienced physical therapists. The final symptoms used in this study were tightness, heaviness, pain, hardness, sore-ness, discomfort, heat, fullsore-ness, tingling, weaksore-ness, and numb-ness. These symptoms were assessed by a visual analog scale (VAS) from 0 to 10 (0 = none and 10 = worst possible). These eleven arm symptoms have good content validity.11,14,17,26,27

Health-related quality of life

We used the global HRQL item in The European Or-ganization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) to represent patients’ HRQL.28 It was originally a likert scale with seven point and

changed to a 0-100 score. A higher score indicates a better health status.

Compliance

We recorded the compliance of applying bandage and home exercise during the intervention period. The former re-corded the daily length of time of bandage application, and the latter recorded the daily home exercise frequency. A calendar was given to each subject to record the hours they wore the bandage, daily frequency of self-exercise, and any other side effect (wounds developed or feeling itchy due to usage of ban-dage).

Data Analysis

Difference of measured value between the affected side and the sound side was calculated as excess limb volume, ex-cess circumference and exex-cess water composition. The quality of life score was calculated with the transformation formula provided by the EORTC QLQ-C30 Scoring Manual.

SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) v11.0 was used in this study. One-way repeated measures for normal distributed data and Friedman tests for non-normal distributed data were used to compare the differences among the three evaluations. The level of statistical significance was set at 0.05. Six ANOVAs were conducted on excess water displacement, execss circumferences on upper part, lower part of upper arm

and forearm, excess water composition, and then the confidence value was set to be 0.05/6=0.0083. Considering the issue of multiple comparisons in the post hoc test of one-way repeated measures for the symptoms, we used Bofferoni correction, α was set at 0.0167 (0.05/3).

RESULTS

Eighteen subjects aged 57.9±9.8 years (ranging from 43 to 74) fulfilling the inclusion and exclusion criteria were recruited. Baseline and demographic data are shown in Table 1. Most of the subjects (72.2%) received a modified mastectomy and un-derwent radiotherapy and chemotherapy. The average duration between onset of lymphedema and our intervention was 26.3± 28.8 months. Over 90% of subjects had received previous treat-ment for lymphedema.

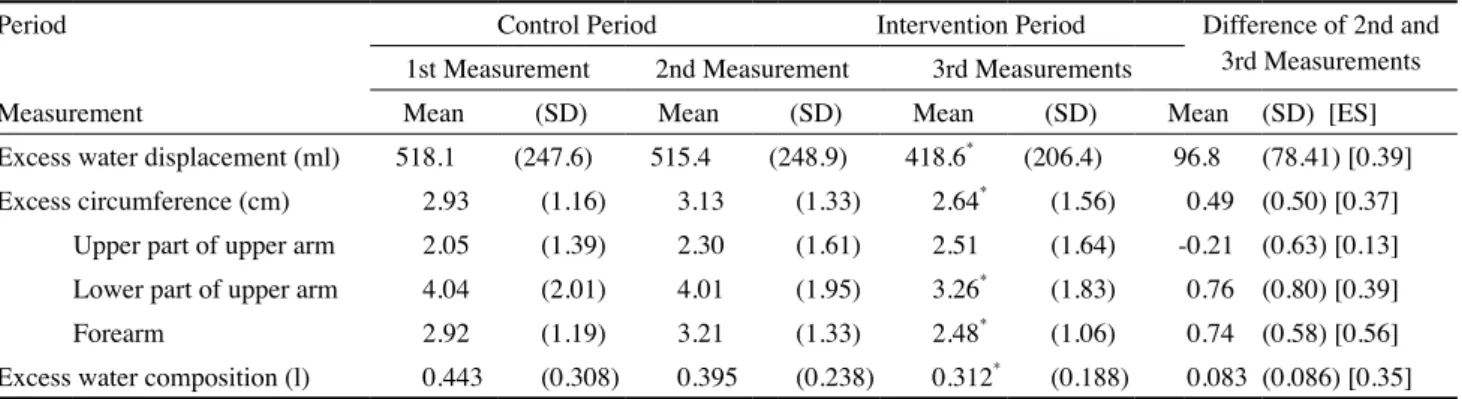

The measurements of excess limb size and water compo-sition are shown in Table 2. There were significant reductions of excess limb size and excess water composition after the intervention period (p<0.0083) except on the upper half of the upper arm. The volume reduction after the intervention period averaged 18.8%. The effect sizes of these measurements ranged from 0.35~0.56 for the statistically significant changes (small to medium effect size).29

The data for the lymphedema-related symptoms are pre-sented in Table 3. The three highest mean score symptoms at the initial evaluation were discomfort (4.40±3.80), fullness (4.37±3.79) and tightness (4.36±3.64). Most of the symptoms

seemed to be worsened during the control phase but no sta-tistically significant difference. At the end of the intervention period, five symptoms were found to be significantly reduced. These were tightness (p=0.006), heaviness (p=0.003), soreness (p=0.005), discomfort (p=0.001) and fullness (p=0.002).

Global HRQL score decreased from 64.4±21.0 to 61.6± 22.2 during control period and increased to 64.4±21.4 after in-tervention period. There was no significant change among the 3 evaluations.

All subjects attended all scheduled sessions for treatment. During the intervention period, the average exercise frequency was 1.8 times per day. Duration of bandage application was 7.7 ±3.9 hours in the daytime and 5.8±2.0 hours in the night. Six patients felt itchy, no wound was present during the interven-tion period.

DISCUSSION

The use of DLT combined with PC in this study has shown positive therapeutic responses. There was a statistically significant reduction in the excess limb volume and circumfer-ence of the lower half of the upper arm and the forearm. Sig-nificant changes in water composition and five symptoms were also noted.

The excess circumference change of the upper half of the upper arm was not significant. Possible explanations might be insufficient clearance of the proximal part, insufficient cover-age of the bandcover-age (bandcover-ages were applied to the upper arm, Table 2. Excess Limb Size and Water Composition among Three Measurements

Period Control Period Intervention Period Difference of 2nd and

3rd Measurements 1st Measurement 2nd Measurement 3rd Measurements

Measurement Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD) [ES]

Excess water displacement (ml) 518.1 (247.6) 515.4 (248.9) 418.6* (206.4) 96.8 (78.41) [0.39]

Excess circumference (cm) 2.93 (1.16) 3.13 (1.33) 2.64* (1.56) 0.49 (0.50) [0.37]

Upper part of upper arm 2.05 (1.39) 2.30 (1.61) 2.51 (1.64) -0.21 (0.63) [0.13]

Lower part of upper arm 4.04 (2.01) 4.01 (1.95) 3.26* (1.83) 0.76 (0.80) [0.39]

Forearm 2.92 (1.19) 3.21 (1.33) 2.48* (1.06) 0.74 (0.58) [0.56]

Excess water composition (l) 0.443 (0.308) 0.395 (0.238) 0.312* (0.188) 0.083 (0.086) [0.35] SD: standard deviation; ES: effect size

Table 3. Lymphedema-related Symptoms among Three Measurement

Period Control Period Intervention Period

Symptoms 1st measurement 2nd measurement 3rd measurement

Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD)

Tightness 4.36 (3.64) 4.71 (3.36) 2.29* (2.33) Heaviness 4.27 (3.38) 4.11 (3.22) 1.86* (2.07) Pain 2.16 (3.28) 1.93 (3.41) 1.30 (2.29) Hardness 4.30 (3.38) 3.69 (3.38) 2.27 (2.62) Soreness 3.18 (3.32) 3.84 (3.55) 1.73* (2.43) Discomfort 4.40 (3.80) 3.61 (3.42) 1.76* (2.35) Heat 1.35 (2.58) 2.06 (3.06) 1.48 (2.43) Fullness 4.37 (3.79) 4.58 (3.51) 2.17* (2.33) Tingling 1.63 (2.89) 1.74 (3.13) 1.18 (2.27) Weakness 3.17 (3.47) 2.61 (3.68) 1.46 (1.86) Numbness 2.29 (3.74) 2.39 (3.66) 1.26 (1.87)

*a significant difference with previous measurement result (p<0.0167)

but they tended to slide down), and the impact of pneumatic compression therapy (bring the lymphatic fluid from the distal part of limb to the proximal part).

It was not significant in the change of VAS measurement of the symptoms in every item. Although patients felt good sub-jectively after the intervention, six symptoms (pain, hardness, heat, tingling, weakness and numbness) showed no significant change after intervention period. The reason should be studied further.

Comparing our result (reduction in volume = 18.8%) with previous studies, the volume reduction is less than others’ (19.3%~67%)7,8,10-17 except in William’s study (9.15%).14 There

are several factors that might contribute to this finding, includ-ing the chronicity of our participants, this might make their improvement within one month being difficult, the delay in evaluation after the final treatment session, poor compliance in bandage application of subjects, previous lymphedema-related treatments and the muscle bulk in the affected limb might be larger because of exercise when intervention, this also can make the difference become smaller.

The timing of the final evaluation might be a contribut-ing factor affectcontribut-ing the result. To eliminate the influence of any fluctuation of severity of the lymphedema, we arranged a fixed time point for all three evaluations (e.g., if the subject received

her first evaluation at 9 a.m., her other evaluations were at 9 a.m. as well). This meant that the schedule of third evaluation might have been arranged one or two days after the final treatment session. In order to understand how the timing of the evaluation affected the results, we compared the results of five subjects who were evaluated twice – once right after the final treatment session and again, one to two days after the final treatment according to the usual schedule. Their volume reduction mea-sured immediately after the last treatment was higher (26.9%) than that measured at our scheduled time (21.4%). This might be an evidence that the evaluation time was a factor which in-fluenced the final measurements. It is possible that many of the other researchers measured the effectiveness of the intervention right after the treatment, whereas there was a delay of one to two days in this study. Aside from the time of evaluation, we did not control the patients’ activities before the evaluation, this may also cause the fluctuation of measured outcomes.

Although attending to the treatment was perfect, poor compliance of bandage application might also limit the treat-ment effect. Aside from attending the treattreat-ment, patients did home exercise less than twice per day, this might hinder their improvement. Most of the researchers did not evaluate patient compliance in using bandage. The subjects in our study used bandages according to the individual’s tolerance. The average

duration of bandage use was 7.7±3.9 hours during the day and 5.8±2.0 hours at night. The limited duration of bandage use might curtail the reduction of lymphedema. It is important to find an alternative treatment for those patients.

Lymphedema is a progressive condition, the subjects were influenced by their previous treatment. Four of our subjects even underwent concurrent treatments. These might also make our treatment effects less prominent. Most researchers did not mention any previous treatment history prior to their study except in Szuba’s and Mcneely’s study.8,15 Szuba’s study was

undertaken into two phases. The first phase was designed for patients with previous untreated lymphedema, the second phase was designed for patients completed previous treatment for at least one month and less than 1 year.8 None of subjects in

Mc-neely’s study received active treatment for lymphedema within the 6 months prior to entering the study.15 In our study, 94.4%

of the subjects received previous lymphedema-related treat-ment, which might cause a ceiling effect and limit the effective-ness of our treatment.

We used the subjects themselves as controls, tried to make up for the ethical limitations of the former quasi-experimental studies.7,8,10-17 Moreover, we recruited subjects who had been

suffering from lymphedema for at least 3 months to assure the chronicity. However, slow progression of lymphedema in con-trol period in most parameters was still noted. The duration of the control period might need to be lengthened in future stud-ies.

In conclusion, although the effect was not prominent, the use of DLT combined with PC in this study has shown positive therapeutic responses.

ACkNOwLEgEMENT

The authors thank all the participants and the National Science Council of the Republic of China for financial sup-port under grant no. NSC93-2314-B-002-118, which made this study possible.

REFERENCES

1. Erickson VS, Pearson ML, Ganz PA, Adams J, Kahn KL. Arm

ede-ma in breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001 93(2):96-111. 2. Motimer PS, Bates DO, Brassington HD, Stanton AWB, Strachan

DP, Levick JR. The prevalence of arm oedema following treatment for breast cancer. Q J Med 1996;89:277-80.

3. Cohen SR, Payne DK, Tunkel RS. Lymphedema: Strategies for management. Cancer 2001;92(4 Suppl):980-7.

4. Pain SJ, Purushotham AD. Lymphoedema following surgery for breast cancer. Br J Surg 2000;87:1128-41.

5. Kasseroller RG. The Vodder school: The Vodder method. Cancer 1998;83(12 Suppl American):2840-2.

6. Reul-Hirche H. Physiotherapy management of lymphedema. In: Sapsford R, Bullock-Saxton J, Markwell S, editors. Women’s Health: A Textbook for Physiotherapists. Philadelphia: Sauders; 1998:474-97.

7. Ko DS, Lerner R, Klose G, Cosimi AB. Effective treatment of lymphedema of the extremities. Arch Surg 1998;133:452-8. 8. Szuba A, Achalu R, Rockson SG. Decongestive lymphatic therapy

for patients with breast carcinoma-associated lymphedema. A randomized, prospective study of a role for adjunctive intermittent pneumatic compression. Cancer 2002;95:2260-7.

9. Eliska O, Eliskova M. Lymphedema: Morphology of the lym-phatics after manual massage. In: Witte MH, Witte CL, editors. International Society of Lymphology. Vol XIV. Zurich: Progress in Lymphology 1994:132-5.

10. Leduc O, Leduc A, Bourgeois P, Belgrado JP. The physical treat-ment of upper limb edema. Cancer 1998;83(12 Suppl Ameri-can):2835-9.

11. Andersen L, Hojris I, Erlandsen M, Andersen J. Treatment of breast-cancer-related lymphoedema with or without manual lym-phatic drainage. Acta Oncologica 2000;39:399-405.

12. Liao SF, Huang MS, Li SH, Chen IR, Wei TS, Kuo SJ, et al. Com-plex decongestive physiotherapy for patients with chronic cancer-associated lymphedema. J Formos Med Assoc 2004;103:344-8. 13. Szuba A, Cooke JP, Yousuf S, Rockson SG. Decongestive

lymphat-ic therapy for patients with cancer-related or primary lymphedema. Am J Med 2000;109:296-300.

14. Williams AF, Vadgama A, Franks PJ, Mortimer PS. A randomized controlled crossover study of manual lymphatic drainage therapy in women with breast cancer-related lymphoedema. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2002;11:254-61.

15. Mcneely ML, Magee DJ, Lees AW, Bafnall KM, Haykowsky M, Hanson J. The addition of manual lymph drainage to compression therapy for breast cancer related lymphedema: A randominzed con-trolled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2004;86:95-106.

16. Diem K, Ufuk YS, Serdar S, Zumre A. The comparison of two dif-ferent physiotherapy methods in treatment of lymphedema after breast surgery. Breast Cancer Res Treats 2005;93:49-54.

17. Mondry TE, Riffenburgh RH, Johnstone PA. Prospective trial of complete decongestive therapy for upper extremity lymphedema after breast cancer therapy. Cancer J 2004;10:42-8.

18. Pecking A, Lasry S, Boudinet A, et al. Postsurgical physiothera-peutic treatment: Interest in secondary upper limb lymphedemas prevention. In: Partsch H, editors. Progress in Lymphology-Proceedings of the XIth Congress in Vienna. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 1988:561-4.

19. Erickson VS, Pearson ML, Ganz PA, Adams J, Kahn KL. Arm edema in breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:96-111. 20. Norman SA, Miller LT, Erickson HB, Norman MF, McCorkle R.

Development and validation of a telephone questionnaire to char-acterize lymphedema in women treated for breast cancer. Phys Ther 2001;81:1192-205.

21. McKenzie DC, Kalda AL. Effect of upper extremity exercise on secondary lymphedema in breast cancer patients: A pilot study. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:463-6.

22. Sander AP, Hajer NM, Hemenway K, Miller AC. Upper-extremity volume measurements in women with lymphedema: A comparison of measurements obtained via water displacement with geometri-cally determined volume. Phys Ther 2002;82:1201-12.

23. Chen YW, Tsai HJ, Hung HC, Tsauo JY. Reliability study of

mea-surements for lymphedema in breast cancer patients. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2008;87:33-8.

24. 蔡涵如,劉毓修,曹昭懿。淋巴水腫評估法之信度研究。物 理治療 2005;30:124-31。

25. Bedogni G, Malavolti M, Sveri S, Poli M, Mussi C, Fantuzzi AL, et al. Accuracy of an eight-point tactile -electrode impedance method in the assessment of total body water. Eur J Clin Nutr 2002;56:1143-8.

26. Caban ME. Trends in the evaluation of lymphedema. Lymphology 2002;35:28-38.

27. Hladiuk M, Huchcroft S, Temple W, Schnurr BE. Arm function after axillary dissection for breast cancer: A pilot study to provide parameter estimates. J Surg Oncol 1992;50:47-52.

28. Chie WC, Chang KJ, Huang CS, Kuo WH. Quality of life of breast cancer patients in Taiwan: Validation of the Taiwan Chinese version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and EORTC QLQ-BR23. Psy-chooncology 2003;12:729-35.

29. Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale(NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum; 1988.

1 臺灣大學醫學院物理治療學系暨研究所 2 臺灣大學醫學院附設醫院復健部物理治療技術科 3 臺灣大學醫學院暨附設醫院外科部 4 臺灣大學醫學院附設醫院物理治療中心 通訊作者:曹昭懿 臺灣大學醫學院物理治療學系暨研究所 台北市徐州路17號3樓 電話:02-33668130 E-mail:jytsauo@ntu.eud.tw 收件日期:99年3月31日 修訂日期:99年5月4日 接受日期:99年5月11日