台灣以中文為母語的小孩的誘發過度泛化現象 - 政大學術集成

全文

(2) Priming Overextensions in Taiwan Mandarin Children. 立. 政 治 大. ‧ 國. 學. BY Tsai-Chun Chen. ‧ er. io. sit. y. Nat. n. a Al Thesis Submitted to the i v n Graduate C hInstitute of Linguistics U i e h n g c of the In Partial Fulfillment Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts. November 2011.

(3) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. ii. i Un. v.

(4) 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. Copyright © 2011 Tsai-Chun Chen All rights reserved. iii. i Un. v.

(5) Acknowledgement 誌謝 寫論文的這一年多的時間,有快樂也有悲傷,我從二下就開始寫了,真正口 試完眨眼已過了一年多的時間,這樣的漫長過程中,想感謝的人很多,因為有這 些人存在在我身邊,才能在我失意時給我力量,在我努力時給我幫助,直到一步 一步達成目標。 首先,想感謝我的指導教授萬依萍老師,在我一開始遍尋不著題目的時候, 給我很好的建議,讓我終於可以定下來好好做一個題目,也因為他開的研究方法 課程,讓我可以在二下就有機會預先處理論文,並且有更多的機會跟老師 meeting. 治 政 討論。雖然二下的時候就已經開始寫論文,但到三年級要提論文計畫的時候還是 大 立 發現自己論文很多問題,讓萬老師費了很多心神替我一次又一次的提點出問題所 ‧ 國. 學. 在,要是沒有老師的指教,我的論文計畫決不會那麼順利就通過,也因為老師一. ‧. 次又一次的指出我論文的問題所在,才能讓我真正了解怎麼樣才是一篇好的論. sit. y. Nat. 文,也讓我了解到真正的學術研究是怎麼一回事,這一年多慢慢的成長,老師的. io. er. 指教真的是不可或缺的因素。. 再來,想要謝謝參與我口試的口委們。提論文計畫書的時候口委是黃瓊之老. al. n. iv n C 師跟張顯達老師,最後的論文口試的口委則是徐東伯老師跟黃瓊之老師。首先, hengchi U 先謝謝各位老師們願意抽時間來參與我的口試,再來想要謝謝老師們提供的意 見,張顯達老師在我提論文計畫書的時候,給了我很多的方向去思考,幫助我可 以在未來更清楚地知道自己的論文應該怎樣修正才會更好;黃老師更是一直在旁 邊給了我實用的意見,讓我知道我論文不足的部分是什麼;徐老師更是在最後的 口試時讓我能從更宏觀的角度去了解自己的論文還有哪些問題是需要改進的。口 委們的意見都很寶貴,因為擁有這些意見,才能讓我更順利地前進。 再來想謝謝提供我受試者的每一位朋友,有些園所是認識的幫忙提供或者介 紹的,有些則是完全不認識的園所,經由接洽而願意讓我進去收實驗,除了園所. iv.

(6) 以外,也謝謝私底下提供自己的小孩子、孫子、姪子讓我做實驗的每位朋友,沒 有你們的幫助,實驗絕對完成不了,我也無法收到那麼多個受試者。另外在這裡, 我想特別謝謝教會的林財川老師,提供我統計上的協助,花私下的時間費心又費 神地了解我的實驗方式跟內容以及統計方法,沒有老師專業的指教,我的統計無 法順利跑出來,感謝林老師的統計教學,這真的是我論文非常重要的一部分。 接著,想要感謝一路走來都陪在我身邊的人,感謝我的父母親總是在我失意 的時候給我打氣跟鼓勵,讓我衣食無虞地寫論文;也感謝身邊的每位朋友,陪伴 我寫論文的每一天生活,有好的結果時陪我一起慶祝,有難過的關卡時,也聽我 訴苦或者幫我一起想方法解決,特別想謝謝怡璇跟孟英,在我口試的時候熱情地. 治 政 幫我送水果上山,另外也想謝謝實驗室的戰友裕台,一直都像前輩一樣給我許多 大 立 幫助跟指引,沒有你們,論文真的沒辦法完成。 ‧ 國. 學. 論文一路走來受到了很多人的恩惠,這本論文不是靠我自己一人就可以完成. ‧. 的了的,很高興能跟大家一起走到今天直到完成論文,因為有你們,所以我才可. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. 以拿到這個學位,真的謝謝!. Ch. engchi. v. i Un. v.

(7) TABLE OF CONTENTS. Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………...iv Chinese Abstract…………………………………………………………………….viii English Abstract……………………………………………………………………….x Chapter 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 2.. 政 治 大 Literature Review……………...…………………………………………………..8 立 2.0 Introduction……………………………………………………………………8 ‧. ‧ 國. 學. 2.1 Three Types of Errors………………………………………………………….8 2.1.1 Category Errors……………………………………………………….....9 2.1.2 Pragmatic Errors……………………………………………………......15 2.1.3 Retrieval Errors………………………………………………………...20 2.2 Comprehension and Production Problems…………………………………...24. y. Nat. sit. n. al. er. io. 2.3 Shape bias…………………………………………………………………….27 2.4 The Study in Gershkoff-Stowe, Connell, and Smith (2006)…………………30 2.5 Characteristics of Mandarin Chinese………………………………………...40 2.6 Summary……………..………………………………………………………42 3. Methodology……………………………………………………………………..45 3.1 Experiment 1………...……………………………………………………….45 3.1.1 Procedure…………………………………………………………….....47 3.1.2 Subjects.………………………………………………………………..48 3.1.3 Materials………………………………………………………………..48 3.1.4 Coding………………………………………………………………….50. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. 3.1.5 Adults‟ Similarity Judgments………..…………………………………52 3.1.6 Word comprehension…………………………………………………...53 3.2 Experiment 2…………………………………………………………………54 3.2.1 Procedure…………………………………………………………….....55 3.2.2 Subjects………………………………………………………………...55 3.2.3 Materials………………………………………………………………..56 3.2.4 Coding………………………………………………………………….57 vi.

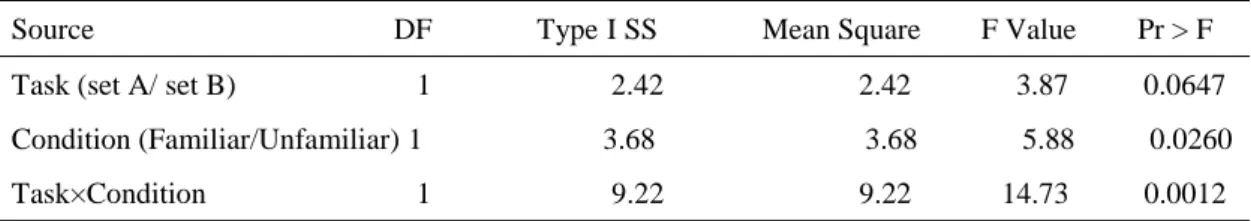

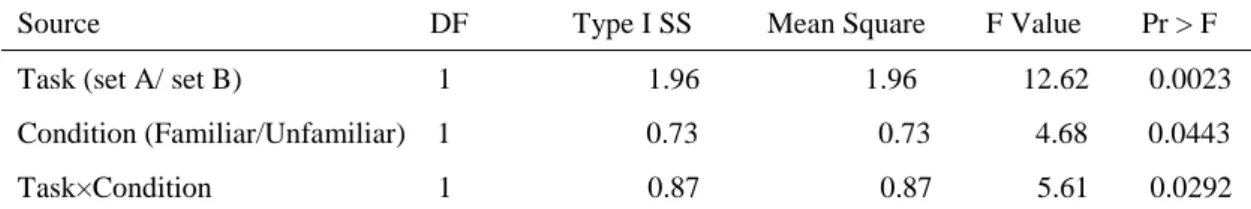

(8) 4. Results and Discussion…………….....…………………………………………..59 4.1 Children‟s Word Comprehension and Production in Experiment 1………….59 4.2 Object Naming in Experiment 1……………………………………………...61 4.3 Priming Effects in Experiment 1……………………………………………..64 4.4 Novel Object Naming in Experiment 2………………………………………69 4.5 Priming Effects in Experiment 2……………………………………………..77 4.6 Perseverative Naming in Experiment 2………………………………………78 4.7 Summary……………………………………………………………………..81 5. Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………83 References……………………………………………………………………………86 Appendix……………………………………………………………………………..97. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. vii. i Un. v.

(9) 國. 立. 政. 治. 大. 學. 研. 究. 所. 碩. 士. 論. 文. 提. 要. 研究所別: 語言學研究所 論文名稱: 台灣以中文為母語的小孩的誘發過度泛化現象 Priming Overextensions in Taiwan Mandarin Children 指導教授: 萬依萍 研究生: 陳采君. 政 治 大. 論文提要內容: (共一冊,兩萬兩千七百字,分五章). 立. 本篇研究的目的是要去比較中文跟英文小孩的誘發過度泛化現象的不同之. ‧ 國. 學. 處。誘發過度泛化現象指的是小孩子因為受到之前誘發過的字的影響進而造成對. ‧. 物品過度泛化現象的情況而稱之。Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) 認為 Dell (1986). Nat. io. sit. y. 提出的擴散激活機制 (spreading activation mechanisms) 可用來解釋小孩的三種. er. 泛化錯誤類型: 類別錯誤 (category errors) 、語用錯誤 (pragmatic errors) 跟提取. al. n. iv n C hengchi U (retrieval errors),此三種泛化錯誤的基底機制應該都是同樣的。另外,他們. 錯誤. 也認為最近激活跟形狀的類似對小孩的命名應該都扮演了很重要的角色。年紀較 大的小孩也應該會擁有比較成熟的心理詞彙所以會比起年紀較小的小孩比較不 容易受到之前提取過的字的影響。因為中文跟英文心理詞彙的不同,我們想去檢 視是否一樣的理論也可套用在中文小孩身上。實驗方法沿用了 Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006)的相同實驗法,做了與他相同的兩個實驗。第一個實驗是熟悉物與不熟 悉物的命名,兩歲小孩要做六次的試驗,然後我們是用三張圖片做為誘發圖片, viii.

(10) 然後請小孩去命名一個真實的物品。第二個實驗是虛構物品命名,我們在這個實 驗裡比較兩歲小孩跟四歲小孩的不同表現。實驗過程跟實驗一是一樣的,只是實 驗二是看虛構物品不是真實物品,且有八個試驗機會而不是六個。結果顯示有一 個跟英文大致上類似的結果。然而我們仍有發現一些不同之處。第一,我們發現 熟悉物在中文裡比起英文似乎有更強的力量。第二個則是兩個語言不同的構詞法 可能會對於比較成熟的心理詞彙造成不一樣的誘發方式。. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. ix. i Un. v.

(11) Abstract. This purpose of this study is to compare the difference of priming overextension phenomena between Mandarin Chinese children and English children. Priming overextension means that children overextend some words due to the effects of the previously primed words. Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) found that spreading. 政 治 大. activation mechanisms (Dell, 1986) should be the underlying mechanisms of three. 立. ‧ 國. 學. types of children‟s overextension errors, i.e., category errors, pragmatic errors, and retrieval errors. Moreover, they thought that recent activation and perceptual. ‧. similarity both play an important role on children‟s object naming. Besides, older. sit. y. Nat. io. n. al. er. children should have a more mature mental lexicon and thus less susceptible to. i Un. v. previously retrieved words than younger children. Due to the difference of the lexicon. Ch. engchi. networks between Mandarin Chinese and English, we want to examine whether the same theory also could apply to Mandarin children. Two experiments which followed Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) were conducted. The first one was familiar or unfamiliar object naming. 2-year-old Children underwent six trials and were primed by three pictures and then were asked to name a real object. The second experiment was novel object naming. We compared the performances of children aged 2 and aged 4 together. The procedure was the same as the experiment 1 despite the fact that x.

(12) children in experiment 2 named novel objects rather than real ones and they underwent 8 trials rather than six. And results showed a generally similar finding with English. However, there are still something different between these two languages. First, we found that familiar objects should have stronger strengths in Mandarin than in English. Second, different morphology in two languages may result in different priming way for more mature mental lexicons.. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. Ch. engchi. xi. i Un. v.

(13) Chapter 1 Introduction. Children‟s language development has undergone an interesting psycholinguistic process. At around 0;6, children start to babble (Fromkin, Rodman & Hyams, 2003). At first, they may babble some sounds that never appear in their surroundings.. 政 治 大. Gradually, their babbling becomes stable, and the pattern is much more like their. 立. native language no matter when it comes to sounds or sound combinations. About age. ‧ 國. 學. one, children enters another stage, i.e., the holophrastic stage, in which children use. ‧. one-word utterances to express more complex meanings (Fromkin, Rodman & Hyams,. y. Nat. er. io. sit. 2003). And in this stage, children will overextend the meanings of some words so that these words will have different semantic boundaries from adults‟. Between age 1;6. al. n. iv n C and 2;0, they start to say two-wordhutterances e n g c(Clark, h i U1993). And roughly around the end of the two year old, there is a vocabulary spurt showing up among children (e.g., Bloom, 1973; Nelson, 1973; Halliday, 1975; Goldin-Meadow, Seligman, & Gelman, 1976; Corrigan, 1978; Dore, 1978; Ingram, 1978; Benedict, 1979; McShane, 1980; Gentner, 1983a; Nelson, 1985; Khami, 1986; Dromi, 1987; Gopnik & Meltzoff, 1987;. Bates, Bretherton, & Snyder, 1988; Lifter & Bloom, 1989; Fenson et al., 1990; Goldfield & Reznick, 1990). During this period, children have a sharply growth of 1.

(14) lexicon in their production. The vocabulary spurt has been considered to be the evidence that children may have known that language is a symbolic system so that everything around them has a name. Alternatively, maybe the vocabulary spurt suggests that children‟s articulatory plans have achieved a certain level so that children can realize it in their production (Clark, 1993). When children begin to use one-word utterances to express the meanings, we can. 政 治 大. observe that their usages of many words are distinct from adults‟ usage a lot. There. 立. are at least three kinds of phenomena observed in children‟s early language in this. ‧ 國. 學. period (Clark, 1993). Those will include situation-bound uses, under-extensions, and. ‧. overextensions. The first one is situation-bound uses, which means children only use a. Nat. er. io. sit. y. certain word under a very specific context. For example, children may use „bye‟ only in the situation of someone leaving the room. Other examples drawn from many. al. n. iv n C h eusen “car” researchers showed that children may when they see a car on the street i U g c honly below from the window, but don‟t use it in other situations (Bloom, 1973; Bowerman, 1978; Braunwald, 1978; Barrett, 1986; Dromi, 1987; Barrett, Harris, & Chasin 1991). The second one is under-extensions, meaning that children use a certain word to refer to only a subset of a larger category in adult usage (Bloom 1973, Reich 1976). For example, children may use shoes to refer to sneakers only (Anglin, 1977; Reich, 1976). And the final one is overextensions, meaning that children will use a word to 2.

(15) refer to not only its actual referents but also other things with perceptual similarity. For example, the word ball may be used to refer to all kinds of balls, and also to the round hanging lampshades, doorknobs, and the moon. Since there are various stages of phenomena in children‟s early language development, overextensions will be the only focus under this study, based on Gershkoff-Stowe, Connell, and Smith‟s findings (2006).. 政 治 大. Traditionally, overextension errors could be categorized into three types. They. 立. are category error, pragmatic error, and retrieval error. Category error happens. ‧ 國. 學. because children have less defining features as adults for a word. And their. ‧. overextensions often based on perceptual similarity (Clark, 1973). Pragmatic error. y. Nat. er. io. sit. happens because of children‟s limited vocabulary (Bloom, 1973; Hoek, Ingram & Gibson, 1986). Children have not acquired certain words yet so that they use other. n. al. words they have known to. iv n C h e nthem. substitute h i U error g cRetrieval. refers to those errors. affected by previously accessed words. Although children could label the object correctly before, they still make an error due to retrieval problems (Gershkoff-Stowe, 2001). In Gershkoff-Stowe, Connell, and Smith‟s (2006) study, they tried to use adults‟ spreading activation mechanism to test Dell‟s (1986) model and to adopt Rapp and Goldrick‟s (2000) study to explain children‟s overextensions. Spreading activation consists of three parts: spreading, summation, and decay. One word 3.

(16) receives activation strengths from spreading and summation, so it can be retrieved. And finally these strengths will decay to zero again. Errors will happen when the incorrect word receives more strengths than the correct one. Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) used this model to explain children‟s overextension errors. Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) thought actually all of these errors could be explained by Dell‟s (1986), and Rapp and Goldrick‟s (2000) spreading. 政 治 大. activation mechanism. A category error may happen because children activate other. 立. similar items with the target objects. Pragmatic errors may appear because the. ‧ 國. 學. unknown object activates the known words in children‟s lexicons. Finally, retrieval. ‧. errors occur because children are affected by another previously activated object. And. y. Nat. er. io. sit. they used two experiments to argue for their viewpoints: object naming task and novel object naming task. And the findings showed that children‟s naming errors could be. n. al. i n C U h e n g cunitarily. explained by spreading activation mechanism hi. v. Besides, the arguments about the question whether children‟s overextensions come from their comprehension or production problems will be also reviewed. In fact, category error suggests comprehension problems while pragmatic error and retrieval reflect production problems. Huttenlocher (1974), Thompson and Chapman (1977), Fremgen and Fay (1980), Rescorla (1980a), Naigles and Gelman (1995), and Gelman, Croft, Fu, Clausner, and Gottfried (1998) all concluded that children often have better 4.

(17) comprehension than their performances, and they all tried to answer whether children‟s overextension performances really reflect their comprehension problems or not. When children learn nouns more and more, their attention to shape also increases. Since shape is a crucial cue for children‟s lexical learning, some factors which may affect children to have this kind of bias will be an interest of this study. This may be. 政 治 大. related to the visual systems of human beings (Landau, Smith & Jones, 1998). Shape. 立. actually is a more direct experience than objects‟ functions or concepts for children. In. ‧ 國. 學. addition, shape seems to have some relationship with the quantities of nouns which. ‧. children have learned. English syntactic cues appear to influence children‟s attention. y. Nat. er. io. sit. to shape as well. Count nouns lead children pay more attention to shape while mass nouns lead children to materials.. n. al. There have been a lot. iv n C heng of debates on children‟s c h i U overextension. issue among. literature in Germanic languages (e.g., Clark, 1973; Bloom, 1973; Nelson, 1974; Thomson & Chapman, 1977; Landau, Smith & Jones, 1998). Few studies use Chinese to examine whether the theory will still be right when it applies to another different language. English and Chinese are two different languages. English is an alphabetic language. Every word is composed of several letters (e.g., Toyoda & Scrimgeour, 2009). On the other hand, Chinese is a logographic language. Each word often 5.

(18) represents a phonological and semantic unit. Chinese words are mostly compounds whose meaning often can be analyzed from their components (e.g., Mok, 2009). The characteristics of Chinese may give children category hint when they classify the world, which may cause them to have different priming overextension phenomena. In this study, we will base on Gershkoff-Stowe et al‟s (2006) findings and see whether Taiwan Mandarin children yield the same or different aspects.. 政 治 大. In this paper, two experiments related to object naming tasks are conducted. The. 立. objects shown to children in experiment 1 are familiar or unfamiliar objects while. ‧ 國. 學. experiment 2 involves novel objects. In each trail, children are primed by some. ‧. pictures, which have perceptual similarity with the objects, and then they are asked to. y. Nat. er. io. sit. name the objects presented to them. If Gershkoff-Stowe et al‟s (2006) claim is right, i.e., overextensions actually can be explained unitarily by Dell‟s (1986), and Rapp and. n. al. Goldrick‟s (2000) spreading. iv n C h e nmechanism, activation g c h i Uchildren. will be affected by. previously retrieved words no matter the objects presented are familiar, unfamiliar or novel to them. In experiment 1, 2-year-old children‟s naming of familiar and unfamiliar objects is investigated. And in experiment 2, 2-year-old and 4-year-old‟s naming toward novel objects are compared. The research questions to be discussed are organized as follows: (1) Can category error, pragmatic error, and retrieval error be explained by 6.

(19) spreading activation mechanisms and deemed as a retrieval process unitarily? (2) What is the role of priming and similarity when children label a novel object? (3) What are the differences of the novel objects‟ naming between 2-year-old and 4-year-old children? (4) For the overextension phenomena, are there any differences between Taiwan Mandarin children and English children?. 政 治 大. Under this study, and based on Gershkoff-Stowe et al‟s (2006) study, we might. 立. hypothesize the following results:. ‧ 國. 學. (1) The underlying mechanisms should be the same among three types of errors.. ‧. (2) Priming and similarity should both have an important effect on children‟s. y. Nat. er. io. sit. novel object naming.. (3) 4-year-old children should be less vulnerable to previously retrieved words.. al. n. iv n C (4) Overextension should be ah universal e n g phenomenon. c h i U However, the difference between English and Chinese may still cause some different results of. priming overextension. We assume that Mandarin children might make fewer errors due to the internal meaning which every character brings.. 7.

(20) Chapter 2 Literature review. 2.0 Introduction In this chapter, we will introduce three types of errors of overextensions. The first one is a type of category error, the second one is a type of pragmatic error, and. 政 治 大. the third one is a type of retrieval error, all illustrated in 2.1. The arguments about. 立. overextension where the viewpoints among literature on whether children‟s. ‧ 國. 學. overextensions come from their comprehension or production problems will then be. ‧. shown in 2.2. Subsequently, in 2.3 the importance of shape for children will be. y. Nat. er. io. sit. introduced. And in 2.4, the spreading activation mechanism is used to make an integral account for three types of errors, and we reviewed the experiments and. al. n. iv n C U characteristics of Mandarin findings in Gershkoff-Stowe et al.h(2006). e n gInc2.5, h i some Chinese will be shown. Finally, we will make a brief summary in 2.6.. 2.1 Three Types of Errors In this section, three types of errors are introduced separately. Under each error type, the definition and some examples will be used for illustration.. 8.

(21) 2.1.1 Category Errors The first kind of error type is called category error. Category error is a kind of overextension that children label two objects with the same name due to their similar perception or concept. Clark (1973) was the first researcher to study children‟s overextension. She proposed a hypothesis called „Semantic Feature Hypothesis‟, which assumed that children may learn just one or two features of a new word at first,. 政 治 大. and gradually they add new features to that word until the word gets a bundle of. 立. features that correspond to adults‟ meaning. Thus, according to this hypothesis,. ‧ 國. 學. children will have a broader meaning than adults since their defining features are. ‧. much less than adults. For example, children at first may think that „dogs‟ refer to. Nat. er. io. sit. y. animals which have four legs. Therefore, „dogs‟ may be overextended to refer to many four-legged animals, such as cows, sheep, zebras, llamas, dogs, and anything else.. al. n. iv n C U as the same thing in their h ewith Children may treat all of these animals n gsimilar c h i features mind. According to Clark‟s (1973) hypothesis, children‟s word learning should be in a top-down order, i.e., they learn the most general features in their early stage and then move on to more specific features. For example, when children learn words about order, such as before and after, the first feature they acquire is +Time. And then they know these two words are related to order and do not happen at the same 9.

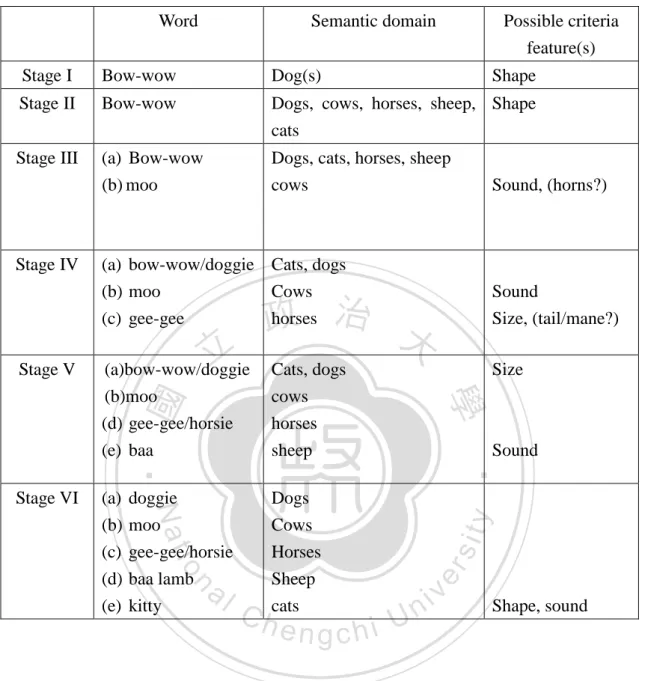

(22) time: –Simultaneous. Next, –Simultaneous implies that the two concepts should have order. Before is +Prior, and after is –Prior. Thus, the more general features that they acquire should be +Time, then they learn more specific ones, i.e., whether these two words are +Simultaneous or –Simultaneous, and finally ±Prior. Clark (1973) also noted that children‟s overextension is based on perceptual similarity between objects and objects. And she further pointed out that the perceptual. 政 治 大. similarity involves six categories, which are movement, shape, size, sound, taste, and. 立. texture respectively. Among these six categories, movement, shape, size, and sound. ‧ 國. 學. appear to be the more prominent norms to affect children‟s overextensions. And. ‧. „shape‟ seems to be the most frequent criterion on which children based to do. y. Nat. er. io. sit. overextensions. However, Clark (1973) still pointed out another fact that children seem not to do overextension based on color criterially. Table 1 is a sample instance of. n. al. i n C U h e 1973): overextension and restructuring (Clark, ngchi. 10. v.

(23) Table 1. A Sample Instance of Overextension and Restructuring (Clark, 1973) Word. Semantic domain. Possible criteria feature(s). Stage I. Bow-wow. Dog(s). Stage II. Bow-wow. Dogs, cows, horses, sheep, Shape cats. Stage III. (a) Bow-wow (b) moo. Dogs, cats, horses, sheep cows. 政 治 大. (b) (c) (d) (e). Cows Horses Sheep cats. io. moo gee-gee/horsie baa lamb kitty. n. al. Ch. engchi. y. Dogs. Sound. sit. (a) doggie. Size. ‧. Cats, dogs cows horses sheep. 學. (a)bow-wow/doggie (b)moo (d) gee-gee/horsie (e) baa. Nat. Stage VI. 立. Sound Size, (tail/mane?). er. Stage V. Sound, (horns?). (a) bow-wow/doggie Cats, dogs (b) moo Cows (c) gee-gee horses. ‧ 國. Stage IV. Shape. i Un. v. Shape, sound. Table 1 shows children‟s change of word domain. According to Clark, at the first stage, children seem to use „bow-wow‟ to refer to „dog‟ correctly for some unknown reasons. At stage II, „bow-wow‟ is overextended to mean many other animals with four legs based on shape similarity. And then at the third stage, children start to broaden their vocabulary. In order to add a new word, children must add some different features to distinguish two words. Thus, they use new features, i.e, sound or 11.

(24) horns to make „bow-wow‟ and „moo‟ different. At stage IV, horses are separated from „bow-wow‟. Due to their intention of separation, children add new features to distinguish „gee-gee‟ from „bow-wow‟, and the feature is size. At this time, children may think horses are bigger dogs. And the next stage indicates that children use „baa‟ to mean sheep. Children may have found that „baa‟ is different from other four-legged animals since they make different sounds. And finally, at the stage V, children add. 政 治 大. „kitty‟ to make „bow-wow‟ and „kitty‟ into two totally distinctive lexicons. Children at. 立. this stage finally developed a more specific vocabulary system.. ‧ 國. 學. In fact, Clark‟s (1973) view has been subject to criticisms. The first one is that. ‧. she thought that children‟s overextensions often base on perceptual similarity,. y. Nat. er. io. sit. especially shape. This kind of shape bias has been in a debate among literature. What feature is the most decisive one when children do overextension is a question that. al. n. iv n C h e nAgnumber researchers have been trying to answer. c h i ofUresearchers agree with Clark‟s (1973) view, including Landau, Smith and Jones (1988), Imai, Gentner and Uchida (1994), and Samuelson and Smith (2005), while others do not, such as Rescorla (1980b), and Gelman, Croft, Fu, Clausner, and Gottfried (1998) because they thought that shape should not be the dominant element for overextensions. The second one which is subject to criticisms is Clark‟s (1973) „Semantic Feature Hypothesis‟, while Nelson (1974) has argued against it and proposed „Functional Core Hypothesis‟. She 12.

(25) thought when children are forming a new concept, what they focus on is the objects‟ functional relations with people. We will introduce these debates in the following paragraphs elaborately. As for shape bias debate, Landau, Smith and Jones (1988) agreed with Clark‟s (1973) view. They believed that children have shape bias, and they thought that although children focus on shape more than other features, such as texture and size,. 政 治 大. they do not neglect texture and size entirely. Similarly, Samuelson and Smith (2005). 立. also believed that shape is the key cue for children to name an object despite the fact. ‧ 國. 學. that there are still some other factors involved, such as features or material substance.. ‧. Imai, Gentner and Uchida (1994) proposed a hypothesis in which they stated that. y. Nat. er. io. sit. children should undergo a shift from shape to taxonomy. They argued that when children have little knowledge about an object, they will use perceptual similarity,. al. n. iv n C U more familiar with a certain h e nwhile especially shape, to do overextension, h i get g c they category and concept, overextension based on taxonomy will increase. Thus, young children depend on shape similarity strongly on word extension firstly and take taxonomic relations into consideration gradually when they grow up. On the other hand, Rescorla (1980b) argued that children‟s overextensions should be based on taxonomic relatedness. She tested some children aged between 1;0 and 1;8 and found that overextensions have a tendency towards falling into proper 13.

(26) taxonomic boundaries. For example, children used truck for a lot of vehicles. Besides, Gelman, Croft, Fu, Clausner, and Gottfried (1998) also pointed out that maybe shape is not the dominant element to override others to result in overextensions despite the fact that it is really salient. Other elements such as objects with taxonomic relatedness are also an important factor to affect children‟s overextensions. Regarding the „Semantic Feature Hypothesis‟ proposed by Clark (1973), this is. 政 治 大. still not the only explanation for children‟s overextensions. Nelson (1974) disagreed. 立. with Clark‟s (1973) viewpoint, and proposed another hypothesis, namely, „Functional. ‧ 國. 學. Core Hypothesis‟, in which she stated that children may learn a new concept from. ‧. their interacting experiences with that object. In Nelson‟s (1974) study, she argued. y. Nat. er. io. sit. that when children learn a new concept, they will focus on objects‟ important functional relations between the object itself and people who act upon it. And. al. n. iv n C h efrom perceptual analysis should be derived h i U core of the object instead of n gthecfunctional a priori one. Therefore, when children first confront a new object, they may notice various kinds of relations between the object and self or other people, places, actions. and so on. And subsequently, they will gradually synthesize all the information they have collected and abstracted a core function about that object so that they understand the true concept of that word. To corroborate her viewpoints, Nelson (1974) mentioned that children‟s early vocabulary of clothing items are mostly shoes and 14.

(27) other footwear which are objects that children act upon. Moreover, objects like furniture seldom appear in children‟s early vocabularies because those items are static and children just see them but do not have interactions with them. Thus, Nelson does not agree with Clark‟s (1973) view. She thought that the dominant feature children notice should be function rather than semantic features. 2.1.2 Pragmatic Errors. 政 治 大. The second kind of overextension errors happens when children use certain. 立. known words to replace the names of some unknown objects. Thus, some researchers. ‧ 國. 學. pointed out that this may be a strategy for children to compensate for their insufficient. ‧. vocabulary, and is called „pragmatic errors‟ in the previous literature (Bloom, 1973;. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Hoek, Ingram & Gibson, 1986). Hoek, Ingram and Gibson (1986) supported the view that children‟s insufficient vocabulary indeed will affect the phenomena of. al. n. iv n C h eoverextended overextensions. In their study, children known words to unknown words ngchi U. in 33% of comprehension, and 45% of production. Notably, this was just one third of the whole data. Thus, Hoek, Ingram & Gibson (1986) proposed that still other factors may result in children‟s overextension. And there are at least six factors involved as follows: (1) Some unknown words would be substituted for other known words by children. This is the pragmatic error in question. 15.

(28) (2) Children would substitute some words acquired earlier for some words acquired later. This is called „retrieval errors‟, which will be introduced in the next error category. (3) The fact that children have not acquired the whole knowledge of the words‟ criterial features yet would lead to their wrong use of two or more words with similar meanings. And this is so-called the „category error‟ which has been mentioned before.. 立. 政 治 大. (4) Children may in some cases use their preferred word to overextend. This. ‧ 國. 學. phenomenon which was called „Preferred Word Hypothesis‟ in Hoek, Ingram. ‧. and Gibson‟s study (1986) means that children may have preference toward. y. Nat. er. io. sit. certain word, thus using it to overextend to various contexts. (5) Some words are phonologically difficult for children to pronounce. Thus,. al. n. iv n C h e n g ceasier children may use some phonologically words instead of harder ones. hi U. (6) Children may substitute a word for a more natural class than its meaning in adults‟ lexicon. This is the „Semantic Naturalness Hypothesis‟ that Hoek, Ingram and Gibson (1986) proposed in their study. This hypothesis stated that some words should be part of a more natural semantic class than some other words for some reasons which researchers have not been able to find out. And those words with more natural classes would be less vulnerable to be 16.

(29) overextended. Accordingly, Hoek, Ingram and Gibson (1986) contended that the factors to cause children‟s overextensions may not be just one, but should be a combination of those factors. The phenomenon that children may choose a known word to replace another unknown and novel word is because they have finite resources available to say the. 政 治 大. objects in the world. Therefore, they use an old and acquired word from a different. 立. category to refer to another new object despite the fact that they may have the same. ‧ 國. 學. cognition of this object as adults. However, many researchers thought that some. ‧. overextensions actually should be classified as a metaphor (Carlson & Anisfeld, 1969;. y. Nat. er. io. sit. Bloom, 1973; Thomson & Chapman, 1977; Nelson et al., 1978; Winner, 1979; Billow, 1981; Hudson & Nelson, 1984). When children call apple as ball, they are expressing. al. n. iv n C that apples are like balls (Naiglesh&eGelman, i UThis is a different but related n g c h1995). phenomenon with children‟s overextensions. Winner (1988) pointed out that it‟s hard to distinguish between an overextended error and a metaphor since they are both based on similarity. For instance, in Winner‟s study (1988), a child may say the “skywriting” as “scar” since the skywriting reminded him/her of the scar on his/her mother. He/she may want to express that the “white line in the sky with its adjacent dots” is very like “the white line on her mother‟s body with its adjacent stitch marks”. 17.

(30) Thus, this is not a kind of overextension error. Instead, it should be a metaphor based on the perceptual similarity between two objects. Hence, some criteria are needed to distinguish overextensions from metaphors. Winner (1979) explained that the differences between an overextension error and metaphor. An overextension usage is from children‟s belief that two objects should have the same name and belong to the same category. For example, children may. 政 治 大. think that string and tail are the same thing due to their similar appearances. This kind. 立. of situation should be an overextension error. On the other hand, if children extend. ‧ 國. 學. one word to another „on purpose‟ and they know the correct name of both objects. ‧. respectively, this should be deemed as a metaphor. Besides, Clark (1983) proposed. y. Nat. er. io. sit. that as children have acquired the correct name of an object as adults, its wrong and overextended name will be abandoned. Thus, an overextended error fills children‟s. al. n. iv n C lexical gap while a metaphor doeshnot. i U exemplified that as long as a e nWinner g c h(1988) child knows the name of “apple”, the overextended name “ball” will be no longer used. On the contrary, metaphorical names are still used even if children have acquired a correct name of that object. Children‟s metaphors can be classified into two categories (Winner, 1979; Winner, 1988). The first one is “symbolic play metaphors”. This kind of metaphors often happens when children are doing symbolic plays. When playing, they pretend 18.

(31) some objects just like another one through actions. For example, if a child put his leg into a wastebasket and says „boot,‟ wastebasket becomes a boot because of the child‟s pretending action. However, in other situations, wastebasket will not be a boot. Furthermore, for the symbolic play metaphor, the main properties on which children based are the object‟s function, or mainly on its function but accompanied with physical similarity at the same time (Winner, 1979; Hudson & Nelson, 1984; Winner,. 政 治 大. 1988). Thus, the renaming of an object does not necessarily take the features of it into. 立. consideration. The features here are neutral for naming.. ‧ 國. 學. The second one is “sensory metaphors,” which means that children do metaphors. ‧. based on perceptual resemblance rather than pretending actions. For this kind of. y. Nat. er. io. sit. metaphor, children turn their focus from actions to the features of the object itself. Children can do metaphors just based on the properties of the thing solely rather than. al. n. iv n C h eThus, with the support of pretending actions. i U of objects here are essential n g cthehfeatures for naming. And the features on which children based are most frequently shape (Winner, 1988). Taken together, children‟s early metaphors result from either pretend action or physical similarity. The function and sensory resemblance are very important for children to classify the world (Clark, 1973; Nelson, 1974). Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) pointed out that the overextension and metaphors together show not only that language has open and flexible properties, but also that 19.

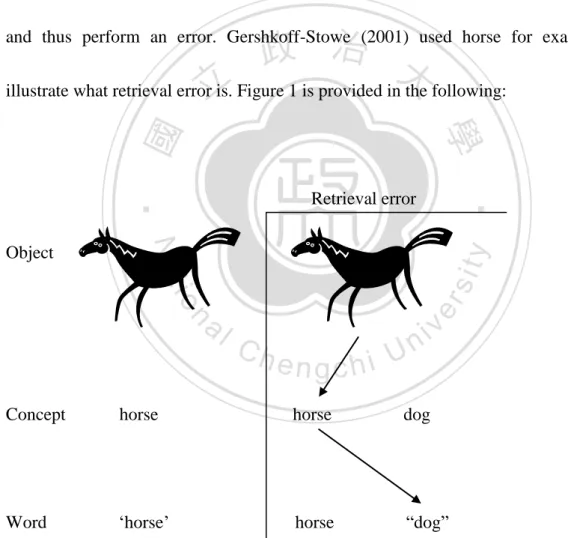

(32) words‟ boundaries are not unchanged. Instead, they undergo a fast and imaginative alteration. 2.1.3 Retrieval Errors The third error is the retrieval error. This kind of errors means that children may temporarily have difficulties in accessing certain words which in fact they have known and understood before, but for somewhat reasons, they fail to recall that word. 政 治 大. and thus perform an error. Gershkoff-Stowe (2001) used horse for example to. 立. illustrate what retrieval error is. Figure 1 is provided in the following:. ‧. ‧ 國. 學. n. al. er. io. sit. y. Nat. Object. Retrieval error. Ch. engchi. i Un. v. Concept. horse. horse. dog. Word. „horse‟. horse. “dog”. Figure 1. Illustration of Retrieval Error (Gershkoff-Stowe, 2001); arrows indicating the direction where information goes during production.. Figure 1 shows the explanation of retrieval error. Retrieval error happens when a child 20.

(33) first sees an object, in this case, a horse, and although he/she understands the knowledge of that word, he/she still chooses a wrong word „dog‟ for the correct one „horse‟. And this kind of errors often show up during the period of vocabulary spurt, i.e., around the end of the two year old, and typically in their 18-to-20-months ages. (Gershkoff-Stowe & Smith, 1997; Dapretto & Bjork, 2000). Gershkoff-Stowe and Smith (1997) mentioned two possible reasons why. 政 治 大. vocabulary spurt often accompanies with retrieval errors. First, it‟s easier to access a. 立. word for adults when the target is in the region with sparse density in one‟s lexicon.. ‧ 國. 學. Namely, if the target word has a lot of similar related words as neighbors, the chance. ‧. of making errors will enhance (Charles-Luce & Luce, 1990). The same situation can. y. Nat. er. io. sit. also be applied to children. At first, children‟s lexicons are sparsely existing in their memory. However, when their vocabulary starts to grow up sharply, namely, entering. al. n. iv n C h lexicons the period of vocabulary spurt, their e n g cbecome h i Udenser abruptly. As long as the. neighborhood density becomes stronger, it is hard to access a lexicon correctly. Thus, children have to make retrieval process catch up to the speed of the sharp growth of vocabulary. Second, some studies have shown that the frequency of the use of target words (Forster & Chambers, 1973) and the age of acquisition (Walley, 1993) are very important to affect lexical access for adults. Therefore, word retrieval will benefit from repetitive practice through speaking and hearing words. Dapretto and Bjork 21.

(34) (2000) assumed that every act of retrieval will fortify the links involved in retrieving a certain lexicon, therefore making every entry in the vocabulary less vulnerable to being interfered. Based on this assumption, it is logical that a child will have difficulty to retrieve words during the period of vocabulary spurt since he/she does not have enough practicing experiences for every new word rapidly adding to his/her lexicon. Furthermore,. Gershkoff-Stowe. and. Smith. (1997),. Dell. (1986). and. 政 治 大. Gershkoff-Stowe (2001) also pointed out that the incorrect retrieval from neighboring. 立. related words often involves those words with either phonological similarity or. ‧ 國. 學. semantic/perceptual similarity. And the result showed that errors involving. ‧. semantic/perceptual (conceptual) similarity happen more frequently than phonological. y. Nat. er. io. sit. similarity, which corresponded with previous research where they contended that naming is semantically intervening but not phonologically (Vitkovitch, Humphreys &. al. n. iv n C h eonly Lloyd-Jones, 1993). In addition, not n gconceptual c h i Usimilarity but also the rate of. speaking will affect children to make errors. Errors will have higher chances to happen when two objects are from the same semantic category and the naming time between two utterances is short. Researchers (Dapretto & Bjork, 2000; Gershkoff-Stowe, 2001) also found that children‟s retrieval errors may happen because of the disturbance of previous word which they just articulated. Take an example in Gershkoff-Stowe‟s study (2001). A 22.

(35) child may see a duck on a picture and call it duck, but subsequently, he/she may confront another picture, in this case, a shoe which is a known word for this child and was correctly articulated in the past, but now he/she may fail to name it correctly and call it duck due to the effect of the previous retrieved word „duck‟. Similarly, Naigles and Gelman (1995) used preferential-looking paradigm to look into the phenomena of children‟s overextensions. The finding in their study showed that the cause of. 政 治 大. children‟s overextensions may come from the effect of another word they said before,. 立. which has a higher frequency for use for them. Thus, the word‟s higher frequency in. ‧ 國. 學. use to children may make children access that word easier than the other correct one. ‧. which is used less for children. For example, children in Naigles and Gelman‟s (1995). y. Nat. er. io. sit. study used dog to name cow. Since frequency has a strong effect on word accessing (Forster, 1990), it is reasonable to expect that children will make more errors when. al. n. iv n C h e nsince new words i Uof those g c hmost. they are producing many. words are used less. frequently by children (Gershkoff-Stowe, 2001). This kind of errors which children make affected by previously spoken words is the so-called perseveration errors. Stemberger (1989) observed that children under age of 3 make perseveration errors in a high rate compared with adults. And he ascribed this kind of phenomenon to the factor that children may need more time to decay the previously retrieved word. According to Gershkoff-Stowe and Smith (1997), this kind of perseveration errors 23.

(36) will decline when children grow up because of their more practice of retrieving words. Taken together, the researchers mentioned in the previous paragraph (Naigles & Gelman, 1995; Dapretto & Bjork, 2000; Gershkoff-Stowe, 2001) all agreed that children‟s retrieval errors come from the influence of the previous accessed word. And importantly, retrieval errors reflect the fact that the occurrence of overextensions may. 政 治 大. be because children have temporary difficulties to access the correct word in their. 立. vocabulary (i.e., a production problem), rather than their incorrect understanding of. ‧ 國. 學. that word (Huttenlocher, 1974; Thompson & Chapman, 1977; Fremgen & Fay, 1980;. y er. io. sit. Nat. 2.2 Comprehension and Production Problems. ‧. Rescorla, 1980a; Naigles & Gelman, 1995).. The three error types mentioned in the previous sections actually reflect the. al. n. iv n C h eabout diverging viewpoints of researchers n gchildren‟s c h i Ucomprehension or production problems. In category error, the Semantic Feature Hypothesis which is proposed by Clark (1973) suggests that children‟s overextensions are from the fact that their comprehension is different from adults‟. Thus, their performance errors reflect their comprehension problems. For example, when a child calls „cow‟ as „dog‟, he/she thinks that they both refer to the same thing. In their lexicon, dogs and cows may have the same defining boundary which results in their errors. In pragmatic error, 24.

(37) researchers (Bloom, 1973; Hoek, Ingram & Gibson, 1986) maintain that children use a known word to replace another unknown word because of their limited vocabulary, which means that this is a strategy for children to compensate for their lexical gaps and this strategy can make communication more effective. Thus, this viewpoint implies that children‟s errors should be just a production error without comprehension problems. In retrieval error, researchers (Huttenlocher, 1974; Thomson & Chapman,. 政 治 大. 1977) contend that children make an error although they know the correct word, they. 立. still choose a wrong word due to retrieval problems. This kind of viewpoint still. ‧ 國. 學. implies that children make a performance error without comprehension problems.. ‧. Due to the discrepancy of three viewpoints, many researchers have tried to. y. Nat. er. io. sit. understand whether children‟s overextension errors result from comprehension or just production problems (Huttenlocher, 1974; Thompson & Chapman, 1977; Fremgen &. al. n. iv n C h&eGelman, Fay, 1980; Rescorla, 1980a; Naigles i UGelman, Croft, Fu, Clausner & n g c h1995; Gottfried, 1998). Gelman, Croft, Fu, Clausner and Gottfried (1998), Naigles and Gelman (1995), Rescorla (1980a), and Thompson and Chapman (1977) all reported similar results about this issue. Their studies show that children‟s comprehension and production are often in an inconsistent situation. Sometimes their comprehension is correct but they still make errors in their production; sometimes both of their comprehension and 25.

(38) production have problems. Namely, children overextend certain concepts in both comprehension and production. And, children often have a better performance in their comprehension than their production. Most of time, they have no problems in comprehension but perform an error in production. Rescorla (1980a) displays some examples of this kind of inconsistency. In her study, a child can respond to Mommy correctly, but calls both of his/her parents Daddy in production. She claimed that the. 政 治 大. word and children involved affect the diverse relations between comprehension and. 立. production.. ‧ 國. 學. Naigles and Gelman (1995) think that this kind of inconsistency between. ‧. children‟s comprehension and production should be retrieval errors. Although they. y. Nat. er. io. sit. cannot eliminate the possibility of pragmatic error, they assume that the possibility of retrieval error is higher than the possibility of the other one. Similarly, Thomson and. al. n. iv n C U h third Chapman (1977) also agree with the view,hi.e., error, and disagree with eng c i retrieval Clark‟s (1973) view because it cannot explain that some errors just appear in production. They also disagree with the second view (limited vocabulary) because it cannot explain why some words are overextended both in comprehension and production. However, Fremgen and Fay (1980) think that the inconsistency in comprehension and production as literature has shown is due to problems of. methodology. They used another method and argued that children „always‟ perform 26.

(39) errors just in their production without comprehension problems. Children know the correct referent although they make an error when producing it. Therefore, Fremgen and Fay (1980) contended that the reasons to cause children‟s overextensions should come from two: limited vocabulary and retrieval error. When children do not know the correct word of an object, they will make an error due to their insufficient vocabulary. On the other hand, when children know the correct word of the object,. 政 治 大. their overextension errors will be attributed to retrieval difficulty. And other. 立. researchers like Gershkoff-Stowe and Smith (1997) stated that overextensions should. ‧ 國. 學. not be an integral phenomenon. Instead, it should sometimes reflect a category error,. Nat. y. ‧. sometimes a pragmatic error, and sometimes a retrieval error.. er. io. sit. Taken together, all the researchers mentioned above agree that children have better competences than their performances. Hence, we cannot consider children‟s. al. n. iv n C h eproduction overextension phenomenon based on i Ualone since production does not n g c hdata necessarily reflect children‟s true competences. 2.3 Shape bias. In the literature, shape is a very important factor to influence children‟s naming and lexical acquisition. It is also a major cue for children‟s overextensions. Thus, some viewpoints about shape bias among literature will be introduced here. Tomikawa and Dodd (1982) indicated that 2- and 3-year-old children will learn 27.

(40) the names of objects with similar shape easier than the names of objects with functions in common. Similarly, Landau, Smith and Jones (1998) also pointed out that shape will dominate children‟s naming while functions are weaker cues. But with their growing up, the importance of function will increase. According to Landau, Smith and Jones (1998), the reasons for the importance of shape in object naming may be attributed to three factors. First, the visual system of human beings is sensitive to the. 政 治 大. shape of 3-dimensional objects. Second, perception of shape is a very intuitive. 立. behavior and need not additional experiences about that thing. Third, shape is a good. ‧ 國. 學. predictor of the object kind. Similarly, Smith and Heise (1992) also proposed that. ‧. although both conceptual and perceptual structures are essential for children‟s. y. Nat. er. io. sit. category learning, perceptual similarity is still more prominent than conceptual structure at the beginning. Children‟s developmental direction is from perception to. al. n. iv n C h e nangimportant structure plays c h i U role. concept. Perceptual. in children‟s category. development. Although function is not that prominent as shape for young children, it still plays an important role in object recognition. Actually, both function and shape are related to people‟s psychological judgments of shape sameness between two objects (Gershkoff-Stowe & Smith, 2004). For example, Biederman (1987) mentioned that objects are recognized by „geons‟ (geometric icons). Thus, that different chairs can be 28.

(41) thought to have the same shape is because they share the same component structure, which is often relevant to the way that people use them. Therefore, to define shape, function of the object is also important. Perceptual similarity is dynamic rather than static (Smith & Heise, 1992). Perceptual similarity is changed with people‟s attention to objects‟ different attributes. This is a kind of psychological process. People shift their attention to certain. 政 治 大. perceptual features between two objects, which results in the variability of perceptual. 立. similarities. And with development, children will change their attention from overall. ‧ 國. 學. similarity to single dimension when comparing objects (Smith, 1989).. ‧. Many studies have shown that shape also contribute to children‟s noun learning. y. Nat. er. io. sit. (Landau, Smith & Jones, 1988; Baldwin, 1989; Jones, Smith & Landau, 1991; Soja, Carey & Spelke, 1991; Baldwin, 1992; Smith, Jones & Landau, 1992; Imai, Gentner. al. n. iv n C U that children would extend h e1999). & Uchida, 1994; Samuelson & Smith, h i found n g cThey the name of a novel thing to other solid things with the same shape. The relation between shape and noun learning can be observed from the following two points, which were found in Gershkoff-Stowe and Smith‟s study (2004). Firstly, the nouns that children acquire at the very beginning are often some items with similar shapes. Secondly, children‟s attention to objects‟ shapes in experimental tasks seems to enhance with the quantities of nouns that they‟ve learned. Shape and the quantities of 29.

(42) nouns display a corresponding increase. However, sometimes children‟s lexical learning may come from other strategy, like „fast mapping‟ (Carey, 1983). For example, that children can response to „bus‟ correctly when asked may be attributed to the fact that they know the other two items are not bus (e.g, train and pig), but not because they truly know that the item is the so-called „bus‟ (McDonough, 2002). In addition, shape bias also seems to have relations with syntactic cues (Smith,. 政 治 大. 2005). In English, count nouns and mass nouns can be differentiated by syntax. For. 立. example, count nouns are often preceded by „a‟ or „an‟ and often refer to discrete. ‧ 國. 學. items, such as „an apple‟ or „a ball‟. On the other hand, mass nouns are accompanied. ‧. with „some‟ or „much‟ and often cannot be counted, such as „some water‟. Count-noun. y. Nat. er. io. sit. syntax will lead children‟s attention to objects‟ shapes while mass-noun syntax will lead children‟s attention to objects‟ materials in the noun generalization experiments.. al. n. iv n C U in English but not in all h edifference And this kind of mass-count syntactic n g c h iis existent languages. 2.4 The Study in Gershkoff-Stowe, Connell, and Smith (2006) In our study, we want to examine whether the assumptions in Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) could be applied into Mandarin Chinese as well. The following are the rationale in their study. Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) thought that overextensions could be deemed as a 30.

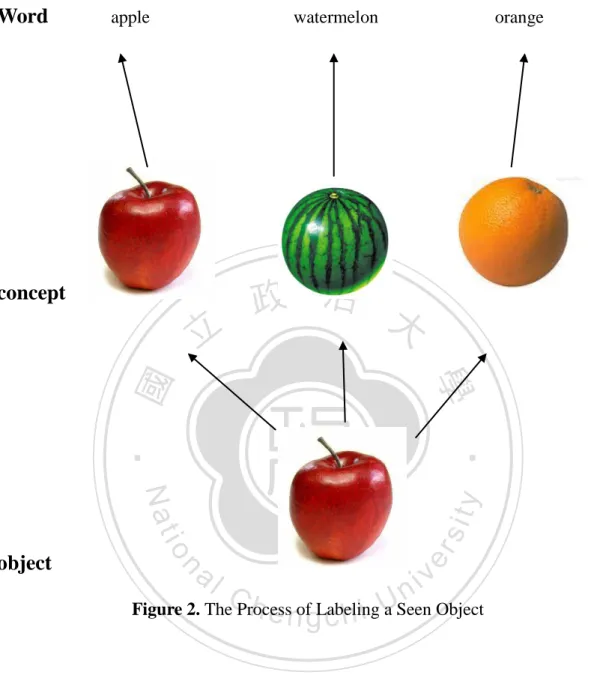

(43) retrieval process. They used the model proposed by Dell (1986) and also followed by Rapp and Goldrick (2000) to explain their assumptions. Dell (1986) and Rapp and Goldrick (2000) tested the adults‟ spreading activation mechanism in their studies. Spreading activation consists of three parts: spreading, summation and decay. When the activation level of one node goes beyond zero, it will “spread” some parts of its activation level to other nodes which are linked to it. After “spreading”, the activation. 政 治 大. will move to its terminal node, and then adds its activation level to the present node,. 立. which is called “summation”. And finally, “decay” is needed to make all the activation. ‧ 國. 學. levels down until they reach zero again. With this mechanism, the occurrence of an. ‧. Nat. er. io. sit. correct one and is finally chosen and tagged.. y. error could be explained. An error happens because it receives more activation than a. Naming an object involves three steps (Johnson, Pavio & Clark, 1996). First,. al. n. iv n C U seeing an object must make otherhsimilar Second, people have to e n gthings c h iactivated.. retrieve an appropriate word for that item from their lexicons. And finally, the articulatory mechanisms must be executed for a response.. 31.

(44) Word. apple. watermelon. concept. 立. 政 治 大. ‧. ‧ 國. 學 er. io. sit. y. Nat. al. iv n C h e nofgLabeling Figure 2. The Process a Seen Object chi U n. object. orange. For example, as illustrated in the figure 2 (Gershkoff-Stowe et al., 2006), when people see an object first, e.g., an apple, other related concepts would be activated, such as orange and watermelon, which are both from the same category. And then all the concepts which have been activated will activate their specific words from the lexicon. At last, among the three words, the word which receives most activation will win so 32.

(45) that is produced finally. As we have mentioned previously, there are two factors to affect children to make retrieval errors during the vocabulary spurt period: lexical density and the frequency of the use of the target words. Besides, semantic/perceptual and phonological similarity between two words often results in incorrect retrieval. Actually, the reason for the occurrences of all of these phenomena is related to the. 政 治 大. activation strengths. When the activation strength is strong, retrieval process is less. 立. vulnerable to making errors. Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) mentioned that three. ‧ 國. 學. factors affect activation strengths. First, activation strengths would be stronger when. ‧. the perceived thing is semantically/perceptually similar to the image in our concept. y. Nat. io. sit. (Huttenlocher & Kubicek, 1983; Martin, Weisberg & Saffran, 1989). For example, a. er. typical bird, like sparrow will activate both the concept and the word “bird” easier. al. n. iv n C U activation strengths will h eornagchicken. than an untypical one, like an ostrich c h i Second, become stronger through repetitive practice (Dapretto & Bjork, 2000). Thus, a high frequency word will receive stronger activation than a low one. That is why adults‟ word retrieval is less susceptible to be interfered. Finally, the third factor is context. The fact that context will affect activation strengths is based on two reasons. The first one is that activation is not a phenomenon which happens and disappears simultaneously. Rather, it will last for a period of time (Cohen & Dehaene, 1998). The 33.

(46) second one is that activation does not only activate a concept or a word. Instead, it also spreads to other related things at the same time (Dell, Burger & Svec, 1997). Accordingly, the activation strength is decided by not only the object which is perceived but also the lingering activation from the previously uttered word. Lingering activation will affect a certain word or concept which is activated and add more activation levels to it so that it would become a stronger competitor. The fact. 政 治 大. that children are susceptible to making retrieval errors from the effect of context is. 立. because they have sparse lexicons and less practice in their very young life, which. ‧ 國. 學. will cause that many words or concepts are weaker competitors (Gershkoff-Stowe &. ‧. Nat. er. io. sit. naming errors and overextension phenomena.. y. Smith, 1997). Therefore, young children in the period of vocabulary spurt have many. Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) thought that all three explanations resulting in. al. n. iv n C h e ninvolve should jointly g c h iin Uthe process. children‟s overextension. in children‟s word. selections. A category error may happen when children see an object and activate another similar item. For example, upon seeing a dog may activate the concepts of a cat. Moreover, pragmatic errors may appear when children see an unknown object and activate another name in their lexicons to substitute for it. Finally, retrieval errors result from the fact that children would be affected by contexts. Young children‟s utterances would be interfered by previously activated object. Thus, children‟s word 34.

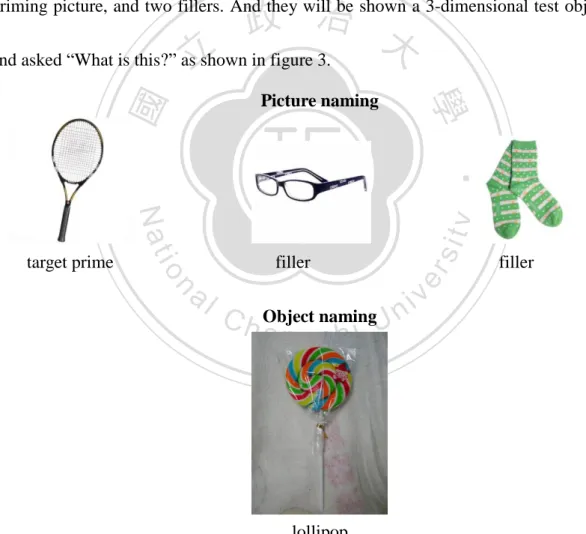

(47) access could be explained unitarily. In Gershkoff-Stowe et al‟s study (2006), they conducted two experiments. The first one is object naming task, and the second one is novel object naming task. In the first experiment, they proceeded six trials to 18 2-year-old children. In each trial, children were primed by three pictures and after priming, they would be shown one 3-dimensional test object and asked to name it. Of three priming pictures,. 政 治 大. one is the target prime and the other two are fillers. Target priming pictures have. 立. perceptual similarity with the test objects while fillers do not have any similarity with. ‧ 國. 學. the test objects. Target priming pictures were divided into two sets. The purpose of. ‧. this was to check that target primes would indeed affect children‟s naming. And the. y. Nat. er. io. sit. test objects were also divided into two sets. One is familiar set; the other is unfamiliar set. They used this to check that no matter which conditions children were involved in,. al. n. iv n C U regard to the order of three children would be affected by thehtarget e n gprimes. c h i With priming pictures, their showing sequences were not fixed. Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) pointed out two reasons. First, the target priming pictures were arranged to. appear equally in the first, second, and third position in case that children simply repeated the previous word just named. Second, in this way, the possibility that children may find out the similarity between the target priming picture and the test object would decrease. Although this may have the effect of reducing the influences 35.

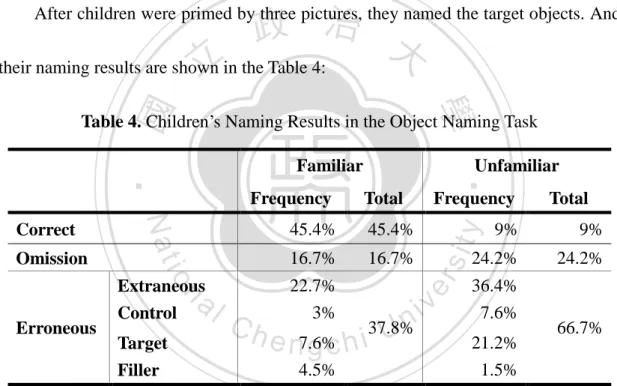

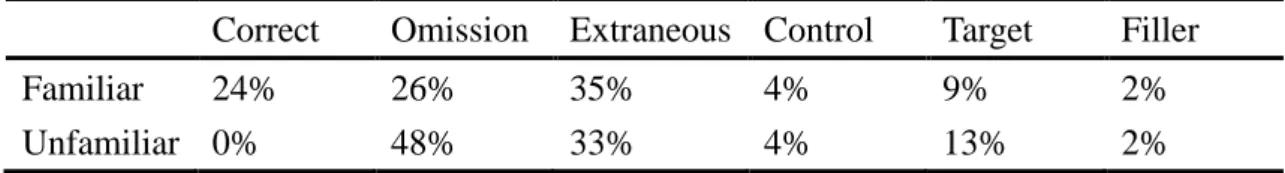

(48) of the target primes, previous researchers have pointed out that the rate of decay of a previously retrieved lexicon for young children is very low (Stemberger, 1989). As for the stimuli in Gershkoff-Stowe et al‟s study (2006), they used adult similarity judgments to rate the similarity between 12 test objects and 24 priming pictures. The rating was from 1 to 10. Scale one means low similarity and 10 means high similarity. And after the object naming task had been conducted to children, each child would do. 政 治 大. the word comprehension task to examine whether they knew the objects‟ names which. 立. they had seen before. And the result showed that children have better comprehension. ‧ 國. 學. in the familiar test object condition. And Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) also compared. ‧. children‟s comprehension performances with their production performances. In. y. Nat. er. io. sit. comprehension, children‟s correctness proportions were 0.63 in familiar test object condition and 0.24 in unfamiliar test object condition. In production, children‟s. n. al. correctness proportions were. iv n C 0.24h e in n familiarh test g c i Uobject. condition and 0.00 in. unfamiliar one. Children‟s comprehension was better than production. As for the object naming task, Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006) made a classification to analyze their data. The answers that children gave were classified into “Correct”, “Omission”, “Extraneous”, “Control”, “Target”, and “Filler” types. And among the six types, the last four could be deemed as children‟s error type together. The results in their study are shown in the Table 2: 36.

(49) Table 2. Children‟s Naming Results in Gershkoff-Stowe et al‟s study (2006:472) Correct Familiar 24% Unfamiliar 0%. Omission. Extraneous Control. Target. Filler. 26% 48%. 35% 33%. 9% 13%. 2% 2%. 4% 4%. Children replied the correct answers in the familiar condition more often than the unfamiliar one (24% vs. 0%). Children also had higher chances to omit the answers in the unfamiliar condition (48%) than in the familiar condition (26%). And of the. 治 政 children‟s error naming type, children gave extraneous大 answers most often both in the 立 ‧ 國. 學. familiar (35%) and unfamiliar conditions (33%). And the different tasks in which children participated did not have different impact on children‟s target error naming.. ‧. sit. y. Nat. Besides, no matter which conditions that children participated in, they were affected. n. al. er. io. by the target primes. Therefore, Gershkoff-Stowe el al. (2006) thought that the. Ch. i Un. v. underlying mechanism among three kinds of errors should be the same.. engchi. In the experiment 2 (i.e., novel object naming task), the performances of novel object naming between 2-year-old and 4-year-old children were compared. According to Gershkoff-Stowe et al. (2006), experiment 2 is based on the theory that word retrieval is a process of competition. When children start to access a word from their lexicons, several related words are activated and compete. And the one which receives most strength will win and be spoken out finally. Gershkoff-Stowe (2001) mentioned that two factors would affect activation. The first one is lingering activation. That is, 37.

(50) children will be affected by previously retrieved words or concepts. The second one is that a present object may activate other related perceptually similar items from one‟s vocabulary. In their experiment 2, these two factors were put together to compare further children‟s word retrieval between 2- and 4-year-old children. And they assumed that it is more difficult for older children to be influenced by the previously retrieved words. This belief came from the theory mentioned before that activation. 政 治 大. strength affects children‟s word selection, and this strength comes from the frequency. 立. of a word to be used (Forster & Chambers, 1973) and lexical density (Charles-Luce &. ‧ 國. 學. Luce, 1990). Repetitive practice could enhance the activation strength of a word. ‧. (Dapretto & Bjork, 2000). Accordingly, older children could have better performances. y. Nat. er. io. sit. for inhibition of other competitors when they retrieved a lexicon and be less susceptible to be influenced by previously activated words.. al. n. iv n C Novel object naming task had h eight i Utrial, children were also primed e ntrials. g cInheach. by three pictures (one target prime and two fillers) and then shown a novel test object. Children‟s task was to label the objects that they saw. The target priming pictures were divided into three groups: high similarity, low similarity, and unrelated group to test the effects of similarity on children‟s naming. Children at each age level were participated into one of three groups at random. Unrelated groups served as a control group to compare with the other two groups to examine children‟s naming when they 38.

(51) were not primed by pictures with perceptual similarity to the test objects. The test objects and target priming pictures were chosen from children‟s spontaneous overextension naming in the experiments of Landau, Smith and Jones (1988) and Samuelson and Smith (2005). Children sometimes gave an English name for the novel objects in their studies. And the novel objects which had been gave a name were used for the high and low similarity priming pictures and the test objects in. 政 治 大. Gershkoff-Stowe et al‟s (2006) study. They selected pictures as high similarity, low. 立. similarity, or unrelated primes by their intuitions. To check whether their intuitions. ‧ 國. 學. were right, adult similarity judgments were conducted. In the experiment 2, all the. ‧. procedures were the same as the experiment 1. The differences were that experiment 2. y. Nat. er. io. were nonce.. sit. had 8 trials and children did not do the word comprehension task since all the objects. al. n. iv n C U And they classified the data h into four types: extraneous, target, and en g c h i omission,. filler. Target naming was further classified into three subcategories: high similarity, low similarity, and unrelated target naming. Besides, they reported another naming type “perseverative naming” which did not show up in the experiment 1. Their findings showed that children‟s naming would be affected by recent activation and perceptual similarity. Sometimes, they are combined together to influence children‟s naming. Therefore, different degree of similarity will affect children to different 39.

數據

相關文件

6 《中論·觀因緣品》,《佛藏要籍選刊》第 9 冊,上海古籍出版社 1994 年版,第 1

According to the historical view, even though the structure of the idea of Hua-Yen Buddhism is very complicated, indeed, we still believe that we can also find out the

You are given the wavelength and total energy of a light pulse and asked to find the number of photons it

Reading Task 6: Genre Structure and Language Features. • Now let’s look at how language features (e.g. sentence patterns) are connected to the structure

volume suppressed mass: (TeV) 2 /M P ∼ 10 −4 eV → mm range can be experimentally tested for any number of extra dimensions - Light U(1) gauge bosons: no derivative couplings. =>

incapable to extract any quantities from QCD, nor to tackle the most interesting physics, namely, the spontaneously chiral symmetry breaking and the color confinement..

• Formation of massive primordial stars as origin of objects in the early universe. • Supernova explosions might be visible to the most

the composition presented by T101 〉, “ First, the style of writing: by and large, these s ū tras are translated into prose.. Even though there are some verse-like renderings,