http://jcc.sagepub.com

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology

DOI: 10.1177/0022022107305241

2007; 38; 595

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology

I-Ching Lee, Felicia Pratto and Mei-Chih Li

Social Relationships and Sexism in the United States and Taiwan

http://jcc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/38/5/595 The online version of this article can be found at:

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology

can be found at:

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology

Additional services and information for

http://jcc.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts: http://jcc.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions: http://jcc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/38/5/595 SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms):

(this article cites 26 articles hosted on the

THE UNITED STATES AND TAIWAN I-CHING LEE

University of Connecticut, United States, and National Chengchi University, Taiwan FELICIA PRATTO

University of Connecticut, United States MEI-CHIH LI

National Chengchi University, Taiwan

This research examines the cultural origins of sexism and how it is enacted within cultures. The harmo-nious tenor of Taiwanese collectivism and the competitive individualism of American culture are hypoth-esized to afford benevolent sexism and hostile sexism, respectively. Whereas hostile sexism was expected to affect Americans’ bias in favor of men more than benevolent sexism, benevolent sexism should affect Taiwanese bias favoring men more than hostile sexism. Deferential family norms and support for hierar-chical intergroup relationships (social dominance orientation) were hypothesized to increase support of sexism in both cultures. Two studies within each culture confirmed the aforementioned hypotheses. The cultural roots of legitimizing ideologies and the cultural origins of different forms of sexism are discussed. Keywords: social dominance orientation; deferential family norms; hostile sexism; benevolent sexism;

cultural influence

Male dominance is ubiquitous despite the fact that societies differ in many culturally sig-nificant ways: by emphasizing different forms of social relationships, having differing fun-damental belief systems, different histories and collective memories (e.g., Brown, 1991). The ubiquity of gender inequality is supported by cultural products such as socialization, sexist ideologies, and social roles (Best & Williams, 1997; Eagly, Wood, & Johannesen-Schmidt, 2004). We believe that cultural psychology can contribute to the understanding of the ubiquity of gender inequality by revealing variations in sexism both within and between cultures.

Our theoretical analysis uses insights from cultural psychology to expand on an over-arching theory of group-based inequality, social dominance theory (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). Social dominance theory identifies various types of group dominance, among which male dominance is proposed to be uni-versal in cultures with economic surplus. Social dominance theory posits that inequality-legitimizing ideologies (henceforth, inequality-legitimizing ideologies) are often developed to maintain male dominance (e.g., Pratto et al., 2001). By formulating attitudes, values, beliefs, and stereotypes that justify male dominance, legitimizing ideologies make it seem acceptable for men to enjoy privileges over women. Although the social functions of ide-ologies are cross-culturally universal, the contents of ideide-ologies and how they are mani-fested in social interaction can vary with culture. In addition, legitimizing ideologies influence how cultural members behave, especially in whom they favor and disfavor in allocating resources (e.g., Pratto, Tatar, & Conway-Lanz, 1999). In other words, because people learn ideologies from their social contexts and are cued by social situations to JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY, Vol. 38 No. 5, September 2007 595-612

DOI: 10.1177/0022022107305241 © 2007 Sage Publications

reproduce the actions that ideologies prescribe, ideologies are the vehicle for recreating the meaning systems that constitute culture.

According to social dominance theory, how much individuals endorse legitimizing ide-ologies is attributable to their general psychological preference for group-based domi-nance, termed social dominance orientation (Pratto et al., 1994; Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). Cross-culturally, people termed high on social dominance orientation tend to support legit-imizing ideologies (e.g., sexist ideology) and have been found to discriminate and dero-gate subordinate groups (e.g., women; see Pratto et al., 2001).

Social dominance theory also postulates what gives ideologies their appeal and power to influence behavior. The most effective legitimizing ideologies are linked to central cultural val-ues and beliefs, which sometimes entail disguising power as something else (e.g., Sidanius, Levin, Federico, & Pratto, 2001). For example, in the West, racist practices such as slavery were often justified by paternalistic ideologies such as the White Man’s Burden, which declared that dominants’ greater power beneficently saved subordinates from their inferior qualities (van den Berghe, 1967). Ideologies that construe domination as care are particularly useful for organiz-ing and justifyorganiz-ing interdependent power relations, such as those between household servants and their masters, feudal rulers and their serfs, parents and children (see Jackman, 1994; Pratto & Walker, 2001). Other forms of cultural ideologies justify dominance and favoritism by decry-ing the contemptuous nature of some compared with the positive qualities of others. Examples of this ideological form include religious and secular conceptions of “merit” or “virtue” and demeaning national, ethnic, and gender stereotypes. Such ideologies may be more functional at segregating groups that would otherwise be in competition by allocating separate occupa-tions, neighborhoods, and resources to them or by justifying such discrimination.

Both of these general forms of ideologies can be applied to gender relationships to justify male dominance; Glick and Fiske (1996, 1997) termed them benevolent sexism and hostile

sexism. On one hand, benevolent sexism describes female characteristics as complements to

male characteristics, providing an apology for heterosexual intimacy and interdependence. On the other hand, women’s sexuality and other characteristics are devalued when compared to men’s in hostile sexism, providing men with the upper hand in such relationships. Glick and Fiske argued that because heterosexual relations can entail both interdependence and compe-tition between men and women, both kinds of sexist ideologies will be found in most cultures. Indeed, Glick et al. (2004) found that scales measuring endorsement of benevolent and hos-tile sexism have been found to be reliable in numerous cultures, indicating that people in a variety of cultures are familiar with both kinds of sexist ideologies.

To examine how people become familiar with benevolent and hostile sexist ideologies and how they may practice them, we focus on two potential sources: familial relationships and cultural contexts. The present research tests first whether family socialization provides people a template to accept or reject benevolent and hostile sexist ideologies and second whether cultural context cues the use of ideologies to determine discriminatory behavior.

FAMILY SOCIALIZATION FOR HOSTILE AND BENEVOLENT SEXISM The family has been considered a major site for socialization of legitimizing ideologies (e.g., Adorno, Frenkel-Brunswik, Levenson, & Sanford, 1950; Begany & Milburn, 2002; Chodorow, 1978). However, empirical evidence of familial socialization that typically focuses on rigid parenting style or parents’ legitimizing ideologies has yielded mixed

results in predicting children’s legitimizing ideologies (Barry, 1980; Feldman, 2003; Tenenbaum & Leaper, 2002). We suspect that this may be because other agents also participate in familial socialization and that rigid parenting styles are not the only way to teach people legitimizing ideologies.

Thus, we propose to examine norms governing family roles that may be taught through dif-ferent parenting styles and from difdif-ferent socialization agents. We name the norms governing family roles deferential family norms. In contrast to authoritarianism theory, which focuses on rigid parenting styles as the impetus for legitimizing ideologies (e.g., Adorno et al., 1950), we postulate that deferential family norms may be learned through either rigid parenting styles or through loving and warm parenting styles. For example, loving Taiwanese parents may teach younger siblings to be respectful to the older siblings and the older siblings to care for the younger siblings as a way to achieve harmony in the family. Second, children may learn def-erential family norms from their parents as well as their neighbors, teachers, and peers. Third, deferential family norms are not only about gender socialization. In most cases, deferential family norms only imply gender in the family roles, thus avoiding the conflation of the con-cepts of gender socialization and sexist ideologies.

Deferential family norms denote hierarchical relationships within families, in which some roles (e.g., parents, husbands, older siblings) are more powerful than other roles (e.g., children, wives, younger siblings). That is, those in more powerful roles (i.e., domi-nants) can set agendas for and have more influence on those in less powerful roles (i.e., subordinates) within the family. Subordinates must defer to the authority of dominants, but dominants are expected to care for subordinates. Thus, deferential family norms include both dominance and caretaking. These complement each other to maintain and enforce hierarchical family relationships.

The domination and caring aspects of deferential familial norms are compatible with hostile and benevolent sexist ideologies. Deferential family norms prescribe that some family members (e.g., parents) should be superior to and control other members (e.g., children), a pattern echoed in the dominant–subordinate positions of men–women within hostile sexist ideology. Practices within families can communicate this ideology. For example, when girls sense that their parents set more rules and limitations on them than on boys (e.g., how late they could stay outside) and learn that children should conform to their parents, girls infer that parents believe boys are more capable of making decisions on their own than girls (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004). Such practices may socialize children to inter-nalize male superiority to females, providing a psychological template for hostile sexism. In addition to communicating who has value, most families also communicate that those who are considered subordinates in families (e.g., children) are to be cared for and loved. Thus, deferential family norms also provide a template for benevolent sexism. That is, the benevolent form of domination–submission exemplified by the parent–child relationship in deferential family norms is structurally compatible with benevolent sexism in which men exert power over women ostensibly for women’s own good (Jackman, 1994). Deferential family norms convey the paternalistic prescription that to protect people from harm or to guide people toward their own good, their freedom and rights should be limited (e.g., Keinig, 1983). As a result, women learn that it benefits them to defer to men (Alumkal, 1999).

Thus, deferential family norms provide a basis for people to endorse both hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. The idea that certain family roles are superior to other family roles should support hostile sexism, whereas the idea that superior family roles should care for subordinate family roles should support benevolent sexism. We argue that which

aspect of deferential family norms, hostile or benevolent, governs people’s behavior should be determined by the social context.

THE INFLUENCES OF CULTURAL STYLE ON THE PRACTICES OF HOSTILE

AND BENEVOLENT SEXISM

Whereas both competitive and interdependent relationships are found within most families and within cultures, cultures place different emphases on competitive versus interdependent relationships. In particular, the contemporary United States, a highly individualistic culture, celebrates each individual’s independence from others. Americans’ sense of self emphasizes competition, self-assertion, and personal responsibility (Block, 1973; Markus & Kitayama, 1991; Triandis, McCusker, & Hui, 1990). As a consequence, Americans often presume that social relationships are competitive and that individuals have to prove their own worth. These basic presumptions about relationships are more compatible with hostile sexism than with benevolent sexism (Barnlund, 1989; Lim & Lay, 2003), and so we expected that in the United States, hostile sexism would have more cultural potency or influence on behavior than benevolent sexism.

In contrast, contemporary Taiwan, a highly collectivist culture, emphasizes interdepen-dence in relationships and the importance of maintaining harmonious relationships in spite of power differences or the conflicting desires of different people (Hofstede, 1998, 2005). In Taiwan, people’s primary sense of self derives from internalizing the expectations of their social roles, and so they are deeply influenced by relational hierarchy and interper-sonal harmony (e.g., Zhang, Lin, Nonaka, & Beom, 2005). Relational hierarchy is learned through the normative structuring of five major hierarchical interpersonal relationships in Taiwan: between sovereign and people, father and son, elder and younger brother, husband and wife, and senior and junior friend.

Relational hierarchy is compatible with both hostile and benevolent sexism. Like hos-tile sexism, relational hierarchy holds an essentialist view of group superiority and deserv-ingness. But relational hierarchy is also consistent with benevolent sexism because it is defined in the role descriptions of five close relationships. Within the close relationships, those in subordinate roles (i.e., subordinates) are taught to trust and show affection toward those in dominant roles (i.e., dominants), whereas dominants are required to take care of subordinates (Han & Ling, 1998).

In Taiwan, the relational hierarchy is in part maintained by obligations within relation-ships. Based in the Confucian precept that people should relate to each other in a support-ive and harmonious manner, the Taiwanese value interpersonal harmony and delineate obligations in different relationships to maintain interpersonal harmony. Thus, whereas the Taiwanese relational hierarchy imposes restrictions on women, it is done in a benevolent way that calls attention to the obligations within the relationship rather than the restrictions placed on subordinates by dominants. For example, a Taiwanese husband may communi-cate that he does not want his wife to work by expressing that it’s his duty to support his family. In Taiwan, where obligations and interpersonal harmony are emphasized, we expect that benevolent sexism has more cultural potency and therefore more influence on sex-discriminatory behavior than hostile sexism.

OVERVIEW AND HYPOTHESES

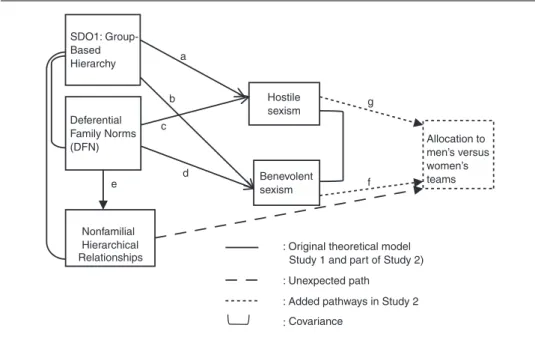

Using structural equation modeling, we tested these ideas in the present research by assess-ing benevolent and hostile sexism and testassess-ing their relations to social dominance orientation and to deferential family norms in the United States and Taiwan. Because sexist ideologies are a form of legitimizing ideologies, support of social dominance orientation should predict support of hostile and benevolent sexism (Paths a and b in Figure 1); deferential family norms should increase support of sexist ideologies (hostile sexism on Path c and benevolent sexism on Path d). To demonstrate discriminant validity for deferential family norms, we also assessed endorsement of nonfamilial hierarchical social relationships (e.g., teachers over students). Because we posit that deferential family norms establish other orientations to hierarchical interpersonal relation-ships, we also tested the path from support of deferential family norms to support of nonfamil-ial hierarchical relationships (Path e). As we did not think that nonfamilnonfamil-ial hierarchical relationships serve as a template for sexism, we tested the fit of models without paths from non-familial hierarchical relationships to the two sexist ideologies.

To test the hypotheses that benevolent sexism is more potent in Taiwan and hostile sexism is more potent in the United States, in Study 2, we provided participants with an opportunity to allocate financial resources to men and to women. We expected endorsement of benevolent sex-ism to predict discriminatory resource allocation in Taiwan (Path f) but not hostile sexsex-ism (Path g set to 0). We expected endorsement of hostile sexism to predict discriminatory resource allo-cation in the United States (Path g) but not benevolent sexism (Path f set to 0). Finally, accord-ing to our cultural analysis, we did not expect gender difference on the magnitudes of the pathways in the model. However, because participant sex has been shown to affect support of sexism (e.g., Swim & Stangor, 1998), we tested for gender differences in the levels of the vari-ables and in the relations of sexism measures to other varivari-ables.

Figure 1: A Theoretical Model of Deferential Family Norms, Social Dominance Orientation, Hostile Sexism, Benevolent Sexism, and Monetary Allocation

: Original theoretical model Study 1 and part of Study 2) : Unexpected path

: Added pathways in Study 2 SDO1: Group-Based Hierarchy Deferential Family Norms (DFN) Nonfamilial Hierarchical Hostile sexism Allocation to men’s versus women’s teams d c b a e f g Benevolent sexism : Covariance Relationships

STUDY 1: SOCIAL DOMINANCE ORIENTATION AND DEFERENTIAL FAMILY NORMS TO SEXIST IDEOLOGIES

The primary purpose of Study 1 was to examine indirect evidence that sexist ideologies are socialized from family values by testing whether young adults who endorse deferential family norms were more likely to endorse hostile and benevolent sexism. Moreover, to confirm that inequality-legitimizing ideologies could predict both kinds of sexism, we tested whether social dominance orientation was positively related to the endorsement of hostile and benevolent sexism. We also tested whether men were higher on hostile and benevolent sexism, deferential family norms, and social dominance orientation and whether the predicted pathways in the model were the same for men and women in the United States and Taiwan, respectively.

METHOD

Respondents

Undergraduate students were recruited from a national university in Taipei, Taiwan, and a state university on the East Coast of the United States. There were 216 female and 133 male students in the Taiwanese sample and 194 female and 126 male students in the American sample. The mean age was 20 years for both the Taiwanese (SD = 1.9) and for the Americans (SD = 1.1). The ethnic composition of the Taiwanese sample was Min-nan (61.4%), Mainlander (21.2%), and Ha-ka (11.8%). In the U.S. sample, the majority was Euro-Americans (81.3%), followed by Asian Americans (8.9%) and Afro-Americans (3.2%).

Measures

Participants responded anonymously to the scales described in the following from 0 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Except for the Hierarchical Social Relationship Scale, all measures were developed in English and translated into Chinese by previous researchers. All scales had acceptable reliabilities (see Table 1).

Hierarchical Social Relationship Scale (HSR). Appropriate items for both Taiwanese

and Americans assessing deferential family norms and norms about nonfamilial hierarchi-cal relationships were revised from shierarchi-cales that measure Taiwanese cultural characteristics, including the Individual Traditionality-Modernity Scale (Yang, 1992; Yang, Yu, & Yeh, 1989) and Social Orientation Scale (Cheng, 2001). Participants rated how much they agreed with appropriate manners in different social relationships, including toward family members (parents vs. children, husbands vs. wives, siblings) and nonfamily targets (man-agers vs. workers, supervisors vs. subordinates, and teachers vs. students). Example items included “Younger brothers should respect their elder brothers in all circumstances” and “Whatever managers ask for, their subordinates should do it immediately without argu-ment.” Correlations between the two subscales ranged from .55 (among Taiwanese men) to .70 (among Taiwanese women). To test whether deferential family norms are different from authoritarianism, we examined correlations between right-wing authoritarianism (RWA), a revised scale of authoritarianism, deferential family norms, and hostile and

benevolent sexism in another U.S. sample. The correlations between deferential family norms and the two types of sexism were significant after controlling for RWA, r(N = 238) = .28, p < .001 for hostile sexism and r(N = 238) = .17, p < .01 for benevolent sexism, showing that deferential family norms and RWA are not the same.

Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI). Half of the 22 items of this scale measure hostile

sexism, and half assess benevolent sexism (Glick & Fiske, 1996). Example items are “Men seek to gain power by getting control over women” (hostile) and “A good woman should be set on a pedestal by her man” (benevolent). The correlation between the two subscales ranged from .02 (Taiwanese men) to .38 (U.S. women).

Social Dominance Orientation Scale (SDO). The Social Dominance Orientation

Scale includes 16 statements (Pratto et al., 1994), half endorsing group-based hierarchy (e.g., “To get ahead in life, it is sometimes necessary to step on other groups”) and half assessing anti-egalitarianism (e.g., “We should strive to make incomes as equal as pos-sible;” reverse-coded). We correlated both scale halves with benevolent and hostile sex-ism and found that anti-egalitariansex-ism did not correlate significantly with both types of sexism in the Taiwanese samples. To avoid introducing cultural specificity about Taiwan, we only used the group-based hierarchy subscale (SDOgb) in the model. The group-based hierarchy subscale was found to correlate modestly with deferential familial norms and with nonfamilial hierarchical relationships, rs < .4, validating the proposition that those were different constructs.

TABLE 1

Reliabilities of the Scales in Taiwan and U.S. Male and Female Samples

Taiwan United States

Scales Male Female Male Female

Study 1

Deferential family norms .82 .77 .69 .73

Nonfamilial hierarchical relationships .81 .83 .71 .75

ASI hostile sexisma .80 .79 .85 .84

ASI benevolent sexismb .73 .69 .72 .78

SDO (group-based hierarchy)c .84 .82 .86 .89

SDO (anti-egalitarianism)d .76 .75 .81 .81

Study 2

Deferential family norms .70 .66 .81 .72

Nonfamilial hierarchical relationships .77 .61 .53 .76

ASI hostile sexisma .82 .84 .84 .76

ASI benevolent sexismb .77 .59 .65 .77

SDO (group-based hierarchy)c .76 .75 .85 .88

SDO (anti-egalitarianism)d .66 .68 .90 .82

NOTE. ASI = Ambivalent Sexism Inventory. SDO = Social Dominance Orientation Scale.

a. Eight items for hostile sexism: Items 2, 4, 5, 10, 11, 14, 15, 16 (Glick & Fiske, 1997). b. Ten items (excluding Item 3) for benevolent sexism.

c. Seven items for group-based hierarchy: Items 3, 6, 7, 10, 12, 14, 15 (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). d. Seven items for anti-egalitarianism: Items 1, 2, 5, 8, 9, 11, 16.

RESULTS

All scales were validated by a confirmatory factor analysis on their respective items conducted using AMOS 5.0 in the two cultural samples separately. Each confirmatory model fit the data well, with Comparative Fit Index (CFI) over 0.90 (0.92 for HSR and ASI and 0.93 for SDO) and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than 0.1 (0.05 for HSR and SDO, 0.04 for ASI) (see the note in Table 1). A list of included items is available on request.

We first tested for gender differences within each sample using multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVAs) on all measures. Two patterns emerged: (a) On most variables, men scored higher than women, and (b) gender differences on most variables were much stronger in the United States than in Taiwan (see means and test statistics in Table 2).

We then used AMOS 5.0 to test the proposed model (Figure 1, correlation matrix in appendix). For Study 1, this model tests whether deferential family norms and SDOgbpredict both benevolent and hostile sexism. Error variances of hostile sexism and benevolent sexism were assumed to covary positively because both assessed sexism. Error variance of SDOgb was assumed to covary positively with error variances of deferential family norms and non-familial hierarchical relationships because all represented hierarchical relationships.

We also tested whether sexism had the same relationships to other variables for men and women by testing the fit of the model when we fixed Paths a, b, c, d, and e for men and women to be equivalent within the same culture. For example, Path a in the American male

TABLE 2

Gender Difference on Hierarchical Social Relationship Scale (HSR), Social Dominance Orientation Scale (SDO), and Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI)a

Taiwan United States

Male Female Male Female

Study 1 M SD M SD F Test M SD M SD F Test

Deferential family norms 1.96 0.85 1.74 0.69 7.51** 2.33 0.77 1.85 0.80 28.29**** Nonfamilial hierarchical relationships 2.32 0.75 2.17 0.71 3.67b 2.64 0.67 2.52 0.71 2.47 SDO group-based hierarchy 2.46 0.91 2.26 0.80 4.54* 1.85 1.02 1.36 1.01 17.76****c SDO anti-egalitarianism 1.50 0.73 1.52 0.63 < 1.00 1.53 0.87 1.11 0.79 19.37****c ASI hostile sexism 2.91 0.70 2.49 0.72 28.41****c 2.83 0.83 1.89 0.90 88.03****c ASI benevolent sexism 2.54 0.59 2.62 0.69 1.32 2.70 0.69 2.51 0.80 4.75**d N 133 216 126 194

a. Based on MANOVAs, with participant sex as independent variable and the reported measures as dependent variables.

b. p< .06.

c. Also significant in Study 2.

d. Marginally significant (p< .08) in Study 2.

TABLE 3

Unstandardized Paths for Deferential Family Norms, Social Dominance Orientation Scale (SDO), and Ambivalent Sexism

Taiwan SE United States SE

Study 1

Deferential family norms ´ Hostile sexism 0.22**** 0.05 0.26**** 0.06

SDOgb´ Hostile sexism 0.24**** 0.04 0.33**** 0.04

Deferential family norms ´ Benevolent sexism 0.19**** 0.04 0.29**** 0.05

SDOgb´ Benevolent sexism 0.13**** 0.04 0.12*** 0.04

Deferential family norms ´ NFHR 0.64**** 0.04 0.56**** 0.04

Study 2

Deferential family norms ´ Hostile sexism –0.03 0.14 0.33**** 0.08

SDOgb´ Hostile sexism 0.40**** 0.12 0.34**** 0.06

Deferential family norms ´ Benevolent sexism 0.22** 0.11 0.14* 0.08

SDOgb´ Benevolent sexism .04 0.10 0.19**** 0.06

Deferential family norms ´ NFHR 0.55**** 0.09 0.48**** 0.05

NFHR ´ Monetary allocation –5,288.11**a 2,185.11 –870.97b 560.24

Hostile sexism ´ Monetary allocation 0.00c 1,275.07****b 388.48

Benevolent sexism ´ Monetary allocation 5,758.60***a 2,097.47 0.00c

NOTE: SDOgb= SDO group-based hierarchy; NFHR = nonfamilial hierarchical relationships.

a. The unstandardized coefficients are in New Taiwan dollars. b. The unstandardized coefficients are in U.S. dollars. c. This path was fixed to 0.

*p< .10. **p < .05. ***p < .01. ****p < .001.

and female samples was fixed to the same magnitude but could differ from the corre-sponding path in the Taiwanese samples. Failure of such models to fit would indicate that there are substantially different relations among the variables for men and women.

The model fit the data well. Despite a significant chi-square value,χ2

(28, N= 669) = 58.11, p= .001, its chi-square ratio was acceptable, suggesting that the significant result was due to the large sample (HOELTER .05 = 480). The fitness indices for the model were good, CFI = .96, and RMSEA = .04, suggesting that the relations among the variables were the same for men and women in the same culture (see statistics in Table 3).

As expected, we found reliable positive effects of SDOgbon both types of sexism (Paths a and b) in Taiwan (β = .28 for hostile sexism and β = .18 for benevolent sexism) and in the United States (β = .39 for hostile sexism and β = .16 for benevolent sexism). This sug-gests that support of general group dominance positively predicts hostile and benevolent sexism in both nations.

Also as expected, support of deferential family norms was associated positively with support of both forms of sexism (Paths c and d) and nonfamilial hierarchical relationships (Path e) in Taiwan and the United States. In Taiwan, support of deferential family norms increases support of hostile sexism (β = .23) and nonfamilial hierarchical relationships (β = .63), whereas in the United States, positive pathways were also found (β = .23 for hos-tile sexism and β = .67 for nonfamilial hierarchical relationships). These pathways suggest that although deferential family norms are defined in interpersonal role descriptions, those norms contain an essentialist view of gender differences as male superiority (hostile sex-ism). Likewise, those who endorsed deferential family norms also had higher support of benevolent sexism in Taiwan (β = .22) and in the United States (β = .32). The significant pathways suggest that deferential family norms educate people in paternalistic ideologies that lead to support of benevolent sexism.

As predicted, all the proposed covariances were positive and significant, except for the covariance between hostile sexism and benevolent sexism in the U.S. men (p= .2) and among the Taiwanese men (p= .4) and the covariance between SDOgb and deferential fam-ily norms in the Taiwanese men (p= .1). This result indicates that after controlling for sup-port of SDOgband support of deferential family norms, men who support hostile sexism may not necessarily support benevolent sexism. Taiwanese men also distinguish between deferential family norms and SDOgbafter controlling for support of hierarchical nonfam-ily relationships.

DISCUSSION

Study 1 found cultural differences in the magnitude of gender differences on deferential family norms, social dominance orientation, hostile sexism, and benevolent sexism. Gender differences were larger in the United States, where gender can be drawn on as a source of individual expression, than in Taiwan, where people are expected to keep their thoughts and behavior in line with social norms (see also Guimond, Chatard, Martinot, Crisp, & Redersdorff, 2006). However, gender differences were not found when examining the strength of pathways among constructs. For example, a person who supports general group dominance is likely to endorse sexist ideology (Paths a and b in Figure 1) regardless of his or her gender. The lack of gender difference on the strength of the associations supports our claim that cultural socialization, not one’s gender per se, legitimizes gender inequality. People learn to endorse sexism from the understanding of certain groups that are dominant (e.g., men) and other groups that are subordinate (e.g., women), as suggested by the positive pathways from SDOgbto two forms of sexism. In addition, support of gender inequality may be socialized through norms governing familial relationships, as we found that support for deferential family norms increased support for benevolent and hostile sexism in both cultural samples. Thus, one’s orientation to group dominance in general and socialization of domi-nant and subordinate family roles enable the adoption of sexist beliefs.

If hostile and benevolent sexist ideologies both serve to govern behavior in ways that recreate gender inequality, then both should be found to predict sexist discrimination. Some contend, however, that benevolent sexism is not sexism at all (e.g., Sax, 2002). To some, wanting to protect women is not as biased as hating or resenting women gaining more power than men. This “positive” orientation toward women might be expected to result in favoritism toward women rather than discrimination against them. If benevolent sexism is a bias against women, however, benevolent sexists should be found to discrimi-nate in favor of men over women.

In Study 2, we examined how discriminatory behavior follows from benevolent and hostile sexist ideologies by asking participants to allocate a fixed amount of money to men’s and women’s groups. Because we believe that cultural ideologies serve as scripts to guide behavior (e.g., Pratto et al., 2001), we expected whichever version of sexism is more culturally potent to predict how much participants would discriminate in favor of men over women. In particular, because Confucianism emphasizes that people should relate to each other in a supportive and harmonious manner, we expect support of benevolent sexism would determine the Taiwanese biased decision for men. In contrast, based on Americans’ seemingly contradictory emphases on egalitarianism, competition, meritocracy, and personal responsi-bility, we expected support of hostile sexism would determine the Americans’ decisions in favor of the men’s group. Also, we expected to replicate the findings in Study 1 concern-ing relations among the variables.

STUDY 2: HOW BENEVOLENT AND HOSTILE SEXISM PREDICT SEX DISCRIMINATION IN TAIWAN AND THE UNITED STATES

METHOD

Participants

In Study 2, 42 female and 24 male participants were recruited from a national univer-sity in Taipei, Taiwan. From a state univeruniver-sity on the East Coast of the United States, 91 female and 38 male participants agreed to participate in exchange for research credit in a general education course. The mean age in each cultural context was comparable, about 19 years of age.

Measures

The Hierarchical Social Relationship Scale, Social Dominance Orientation Scale, and Ambivalent Sexism Inventory used in Study 1 were measured in Study 2. Reliabilities of those scales were acceptable and are reported in Table 1.

Sex discrimination. Institutionalized sex discrimination takes different forms in Taiwan

and the United States, so we used different cover stories for the discrimination experiments in Taiwan and the United States. In Taiwan, participants were told that their school was conducting a study on how the school should allocate current funding to two newly formed groups, a group for male employment studies and a group for female employment studies. In the United States, the groups of male/female employment studies were replaced by men’s and women’s sports teams because employment rates in general are not as disparate in the United States as in Taiwan (Bowen, 2003; Davison & Burke, 2000), but support for men’s and women’s athletics remains both disparate and in dispute in the United States. Participants in Taiwan were told they could allocate a total of NT$100,000 and participants in the United States were told they could allocate a total of US$20,000. In blanks provided, participants wrote down how much money they wished to allocate to the men’s group (team) and to the women’s group (team).

Procedure

Participants first completed the scales and were invited back to participate in a funding allocation experiment on a different date. Before participants began to allocate funding, they were told that dividing the money in half for the male/female groups (teams) would not provide enough for either group (team). To help them become familiar with the process, participants were provided with a third party’s decision and reasons for how that person allocated money. To reduce the social desirability of a half–half split, the third party’s decision and reasons were designed to favor the men’s group (team). Participants were told to carefully consider their own reasons and then to write in the amount they wished to allocate to each group (team).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

A new dependent variable, differential monetary allocation in favor of men’s groups over women’s groups, was added to the model tested in Study 1. Because we hypothesized that in

Taiwan endorsement of benevolent sexism should predict allocation of more monetary resources in favor of men, we fixed the pathway from hostile sexism to monetary allocation to 0 for the Taiwanese sample. Conversely, because in the United States endorsement of hostile sexism should predict allocation of more monetary resources in favor of men, we fixed the pathway from benevolent sexism to monetary allocation to 0 for the U.S. sample. Thus, the model fit indices suggest whether these restrictions were acceptable.

We argued that relationships among our constructs result from cultural upbringing rather than from one’s gender per se. Our Study 1 results supported this claim, so we collapsed male and female samples within each cultural context for Study 2. After adding an unpredicted pathway from nonfamilial hierarchical relationships to monetary allocation in favor of men, the model fit the data,χ2(10, N= 195) = 14.48, p = .15, CFI = .98, and RMSEA = .05 (see Table 3). We also tested the model incorporating participant sex as a moderating variable; this more complicated model did not explain the data better than our proposed model, the dif-ferential χ2(10, N = 195) = 13.56, p = .19.

Replicating Study 1, we found a positive pathway from deferential family norms to benevolent sexism in the Taiwanese sample (β = .24) and marginally significant pathway in the U.S. sample (β = .15, p = .07). Moreover, deferential family norms were found to affect hostile sexism in the United States (β = .31) but not in Taiwan (p = .83). Deferential family norms were also found to affect support of nonfamilial hierarchical relationships for the United States (β = .64) and for Taiwan (β = .63). The results found robust pathways to the types of sexist beliefs potent in particular cultures (benevolent sexism in Taiwan and hostile sexism in the United States). Moreover, the results verified that support of hierar-chical relationships (interpersonal relationships or gender relationships) might be social-ized through learning family roles.

As expected, the Taiwanese participants who endorsed benevolent sexism more strongly were more likely to allocate money in favor of men over women (β = .32). This result confirms that benevolent sexism is sexism against women, not a bias in favor of women. Conversely, American participants who supported hostile sexism were more likely to allocate money in favor of the men’s team over the women’s team (β = .29). Hence, as expected, the version of sexism most culturally potent predicted discriminatory behavior against women in its cultural context. Because the model fit the data without allowing benevolent sexism to predict discriminatory behavior in the United States and without allowing hostile sexism to predict discriminatory behavior in Taiwan, one can conclude that these ideologies, respectively, were not necessary to account for participants’ sex dis-crimination in their respective cultural contexts. We also tested a cultural invariance model in which the paths from respective types of sexism to monetary allocation in favor of men were fixed to be the same across cultures. The model did not fit the data well,χ2(10, N= 195) = 18.94, p < .05, suggesting that hostile and benevolent sexism did not function sim-ilarly in Taiwan and the United States. Moreover, we tested whether the loadings of the two paths differ within cultures. In the U.S. sample, the difference of the two loadings reached statistical significance,β = .29 for hostile sexism to β = .01 for benevolent sexism,

z= 3.14, p < .01. A reversed trend was observed in the Taiwanese sample, β = .30 from

support of benevolent sexism to biased monetary allocation and β = .16 from support of hostile sexism to biased monetary allocation, although it did not reach statistical signifi-cance, z= 1.11, plausibly due to the small sample size.

The differential associations of hostile and benevolent sexist ideology with unequal allocation in favor of men in Taiwan and the United States suggest that when discussing

how ideologies legitimize gender inequality, one should examine associations between, not the mean level support of, sexist ideologies and gender inequality. Mean levels of sexism may not be indicative of how normative sexist discriminatory behavior is. Associations between sexist ideologies and sexist behavior can test whether those who endorse sexism also discriminate in their behavior or not. Given that people’s actions do not always follow from their beliefs and that people’s endorsement of ideologies depends in part on which stan-dards or reference groups they have in mind (Biernat & Vescio, 2002) and whether they think endorsement of ideologies is socially accepted, it may be that two ideologies are endorsed to the same extent on scale measures but that only one corresponds with behavior. Instead of examining mean levels by culture to learn what ideologies are important within a culture, we believe that testing whether endorsement of ideology corresponds to discriminatory behavior is the way to tell whether in practice an ideology is culturally potent.

Moreover, it is worth considering whether our result that different forms of sexist ide-ology influenced participants’ discriminatory behavior in Taiwan versus the United States was due to the different cover stories we provided in Taiwan and the United States. To accept this interpretation, one would have to assume that benevolent sexism is particularly germane to working environments and that hostile sexism is particularly germane to sports. This is not plausible, in part because Americans’ support of hostile sexism has been found to predict how people perceive sexual harassment cases in a working setting (Wiener, Hurt, Russell, Mannen, & Gasper, 1997). Rather, we believe that the two settings we examined are each very important to people in the respective culture and that the dif-ferences in which kind of sexism best predicts sex discrimination in each culture reflects the more potent form of sexism in each culture.

The unexpected pathway only existed in the Taiwanese sample (β = –.14) between the support of nonfamilial hierarchical relationships and monetary allocation in favor of men’s groups, suggesting that those who support nonfamilial hierarchical relationships oppose biased monetary allocation in favor of men’s groups. The women’s movement in Taiwan has been most successful in promoting equal rights at school (Wang, 1999), whereas the prosperous Taiwan economy has resulted in increasing numbers of women in the work-force (Jao, Lai, Tsai, & Wang, 2003). In school and in the workwork-force (measured in nonfa-milial hierarchical relationships) in which nondiscrimination policy is enforced and where no cultural emphasis on competition and individuality exists in Taiwan (e.g., in academia), the effects of nondiscrimination policy may exhibit itself in the negative pathway (bias in favor of women). Further studies are needed to clarify reasons for such a relation.

The use of college students and the relatively small Taiwanese sample suggest caution in generalizing the results of Study 2, especially when interpreting the mean levels of vari-ables. However, our theorizing mainly pertains to relationships among variables, and we suspect that finding evidence of those in small samples implies such relations would also be found in larger and more diverse samples. Replication of these results in broader samples is, of course, important.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

This article addresses how cultural psychology can help account for ubiquitous gender inequality. Consideration of the role of culture in sexism should lead one to want to see evidence that sexist ideologies are socialized and that such ideologies are linked to sexist

practices and particular forms of social relationships. The present studies provided such evidence.

Marriage and family practices have been theorized by many to be the core origin of sexism and gender inequality (e.g., Collier, 1988; Okin, 1989). Expanding on structural– functionalist approaches by incorporating cultural ideologies into our theoretical under-standings of social relationships, the present research illustrates how cultural ideologies and norms governing family relationships help to recapitulate sexism by influencing people to discriminate against women. We showed indirect evidence that being socialized to accept deferential family norms helps prepare people to accept both hostile and benevolent sexism. Furthermore, Study 2 found that both sexist ideologies can lead to sex-discriminatory behavior. This kind of evidence for the mediational role of cultural ideologies emphasizes the importance of social learning as compatible with social structure in understanding the origins of sexism.

Social dominance theory has argued that many cultural ideologies help legitimize group dominance. People who endorse group-based dominance in general tend to endorse sexist ideologies, regardless of their gender. Group-based hierarchy can be legit-imized both by devaluing subordinate groups and by describing subordinate groups as in need of care and guidance. Paternalistic ideologies may seem positive or appear con-cerned with subordinates’ well-being; thus, it has been difficult for some to identify benevolent sexism and other paternalistic ideologies as supporting group dominance. Indeed, despite several kinds of independent scholarship arguing that paternalistic ide-ologies may be tools of oppression (e.g., Glick & Fiske, 1996; Jackman, 1994; Pratto & Walker, 2001), some people still question whether benevolent sexism is in fact harmful to women (e.g., Sax, 2002). The present research demonstrates that benevolent sexism does legitimize women’s subordination in three ways. First, both in the United States and in Taiwan, endorsement of benevolent sexism correlated positively with people’s general endorsement of group-based hierarchy. Second, benevolent sexism correlated positively in the United States and in Taiwan with endorsement of deferential family norms. Third, in Study 2 in Taiwan, those who endorsed benevolent sexism were more likely to allocate more resources to men’s groups than to women’s groups. In addition, although Study 2 demonstrated that benevolent sexism is the more culturally potent form of sexism in Taiwan, the gender empowerment measure, a general index of women’s sit-uations (e.g., income shares, professional opportunities, etc.) compared with men’s, indicates more inequality against women in Taiwan than in the United States (Jao et al., 2003). Hence, one cannot argue that benevolent sexism being more potent in Taiwan than in the United States has not led to structural sexism in Taiwan.

It has been argued that ideologies are most effective in governing relationships when the form of ideology corresponds closely to the form of relationship and even to the norms of the relationship in question. For example, Glick and Fiske (2001) hypothesized that hos-tile sexism pertains mainly to women competing with men in the workforce (e.g., profes-sional women) or in the political arena where power is contested (e.g., feminist activists) and benevolent sexism pertains mainly to women within families (e.g., housewives, mothers). Our argument and data substantially extend this analysis by identifying cul-tural psychological variables that may make either demeaning and hostile ideologies or paternalistic, benevolent ideologies more pertinent. We argued that hostile sexism would be more culturally potent in the United States, whereas benevolent sexism would be more culturally potent in Taiwan. This original theoretical contribution could be extended and

replicated in several ways. First, other forms of demeaning versus paternalistic ideologies besides sexism could be assessed. Second, differences among individuals within a culture, particularly variations in how much they construe themselves as independent from or inter-dependent with others, could be examined, as could differences in the norms of relation-ships. Finally, experiments that manipulate whether participants identify collectively or feel competitive with others could govern the kinds of ideologies they draw on to deter-mine their actions or justify their behavior. Such studies could usefully indicate the gen-eral social circumstances in which different ideologies are employed.

Our results also have implications for gender inequality. On practical grounds, our results imply that when promoting ways to counter sexism or to raise awareness of sexism, it would be useful to be sensitive to the form of sexism that is more potent in the culture. In particular, it would appear that arguing against hostile sexism to people who believe they cherish and revere women will be confusing at best and perhaps engender resentment that they are being accused of sexist hostility that they do not have. Likewise, arguments against hostile sexism may only seem right and proper to hostile sexists whose individu-alism leads them to reject special consideration of women and whose priority for a “level playing field” may lead them to overlook the structural situations of women. In fact, Americans may justify hostile sexism by resorting to meritocracy and derogating those who argue for a level playfield (e.g., feminists or affirmative action activists) as asking for “special” treatment (Crosby & Clayton, 2001).

Second, the fact that benevolent and hostile sexism, with different apparent stances toward women, both result in perpetuating gender inequality in two quite different cultures indicates something of the broad cultural–ideological wall that feminists face. However, the affective inconsistency between the two kinds of ideologies might be rhetorically used to undermine the legitimacy of both. Furthermore, the fact that sexist practices are bol-stered by ideologies with contradictory contents (benevolent and hostile sexism) helps speak against the “naturalness” of sexism.

Another way our results speak to the cultural embeddedness of sexism is that we found that endorsement of benevolent sexism is compatible to deference within the family in both cultures. We suggest that benevolent sexism and other paternalistic ways of legit-imizing inequality are likely to be potent in cultures with predominantly paternalistic hier-archical relationships. Such cultures are of course neither unusual nor peculiar. Social arrangements wherein people in certain roles are mandated to make decisions, control material resources, receive homage, and to care for subordinates, who in turn were denied freedom and provided service, have been found on every continent and in many eras (e.g., feudal Japan and feudal Europe, slaveholding United States, Muslim societies in the Middle East). Perhaps every society has at least some pairs of roles for which paternalism is understood to be proper. Our results suggest that the paternalistic ideologies that help prescribe and legitimize oppression within such relationships provide a schema that makes adopting a related ideology that much easier (e.g., Jackman, 1994; Pratto & Walker, 2001). This process helps create cultural continuity among members of a culture, among belief systems in a culture, and between a culture’s belief systems and its social structure. By examining such cultural beliefs with reference to cultural meanings but also with reference to social structure, we are able to understand culture not as peculiarity but as the level of analysis wherein one can understand the interplay of individual psychology, social struc-ture, and social meaning.

APPENDIX

Corr

elation Matrix f

or Study 1 and Study 2 (Upper Diagonal f

or Males, Lo wer Diagonal f or F emales in Study 1) T aiwanese Samples U .S. Samples Social Social Dominance Defer ential Nonfamilial Dif fer ential Dominance Defer ential Nonfamilial Dif Orientation F amily Hier ar chical Hostile Bene volent Monetary Orientation F amily Hier ar chical Hostile Bene volent Monetary Constructs Scale (SDO) Norms Relationships Se xism Se xism Allocation Scale Norms Relationships Se xism Se xism Allocation Study 1 Group-based hierarchy (SDO gb ) 1.00 0.11 0.25 0.26 0.22 1.00 0.36 0.39 0.51 0.33 Deferential f amily norms 0.25 1.00 0.55 0.18 0.24 0.37 1.00 0.68 0.45 0.32 Nonf amilial hierarchical relationships 0.34 0.70 1.00 0.10 0.31 0.38 0.67 1.00 0.35 0.31 Hostile se xism 0.36 0.36 0.37 1.00 0.02 0.44 0.33 0.29 1.00 0.30 Bene v olent se xism 0.24 0.29 0.29 0.30 1.00 0.24 0.39 0.29 0.38 1.00 Study 2 means 2.20 1.96 2.51 2.63 2.58 4,257.58 1.70 2.10 2.64 2.36 2.68 Standard de viations 0.80 0.68 0.60 0.83 0.63 1,1234.99 1.03 0.79 0.61 0.87 0.70 Group-based hierarchy (SDO gb ) 1.00 1.00 Deferential f amily norms 0.16 1.00 0.20 1.00 Nonf amilial hierarchical relationships 0.27 0.63 1.00 0.20 0.64 1.00 Hostile se xism 0.38 0.04 0.19 1.00 0.46 0.38 0.27 1.00 Bene v olent se xism 0.09 0.25 0.32 0.14 1.00 0.31 0.21 0.24 0.34 1.00 Dif

ferential monetary allocation

0.15 0.01 –0.18 0.15 0.23 1.00 0.18 0.10 –0.06 0.25 0.07

REFERENCES

Adorno, T. W., Frenkel-Brunswik, E., Levenson, D. J., & Sanford, R. N. (1950). The authoritarian personality. New York: Norton.

Alumkal, A. W. (1999). Preserving patriarchy: Assimilation, gender norms, and second-generation Korean American Evangelicals. Qualitative Sociology, 22, 127-140.

Barnlund, D. C. (1989). Communicative styles of Japanese and Americans: Images and realities. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Barry, R. J. (1980). Stereotyping of sex role in preschoolers in relation to age, family structure, and parental sex-ism. Sex Role, 6, 795-806.

Begany, J. J., & Milburn, J. A. (2002). Psychological predictors of sexual harassment: Authoritarianism, hostile sexism, and rape myth. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 3, 119-126.

Best, D. L., & Williams, J. E. (1997). Sex, gender, and culture. In J. W. Berry, M. H. Segall, & C. Kagitcibasi (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (3rd ed., pp. 163-212). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Biernat, M., & Vescio, T. K. (2002). She swings, she hits, she’s great, she’s benched: Implications of gender-based shifting standards for judgment and behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 28, 66-77. Block, J. H. (1973). Conceptions of sex roles: Some cross-cultural and longitudinal perspectives. American

Psychologist, 28, 512-526.

Bowen, C. C. (2003). Sex discrimination in selection and compensation in Taiwan. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 14, 297-315.

Brown, D. E. (1991). Human universals. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Cheng, B. S. (2001). [The social orientation in the Chinese societies: A comparative study between Taiwan and Mainland China]. Chinese Journal of Psychology, 43, 207-221.

Chodorow, N. J. (1978). The reproduction of mothering. Berkeley: University of California Press. Collier, J. (1988). Marriage and inequality in classless societies. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Crosby, F. J., & Clayton, S. (2001). Affirmative action: Psychological contribution to policy. Analyses of Social

Issues and Public Policy, 1, 71-87.

Davison, H. K., & Burke, M. J. (2000). Sex discrimination in simulated employment contexts: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56, 225-248.

Eagly, A. H., Wood, W., & Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C. (2004). Social role theory of sex differences and similar-ities: Implications for the partner preferences of women and men. In A. H. Eagly, A. E. Beall, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The psychology of gender (pp. 269-295). New York: Guilford.

Feldman, S. (2003). Enforcing social conformity: A theory of authoritarianism. Political Psychology, 24, 41-74. Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491-512.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1997). Hostile and benevolent sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 119-135. Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). Ambivalent stereotypes as legitimizing ideologies. In J. T. Jost & B. Major (Eds.),

The psychology of legitimacy (pp. 278-306). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., et al. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 713-728.

Guimond, S., Chatard, A., Martinot, D., Crisp, R. J., & Redersdorff, S. (2006). Social comparison, self-stereotyping, and gender differences in self-construals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 221-242.

Han, J., & Ling, L. H. M. (1998). Authoritarianism in the hypermasculinized state: Hybridity, patriarchy, and cap-italism in Korea. International Studies Quarterly, 42, 53-78.

Hofstede, G. (1998). The cultural construction of gender. In G. Hofstede (Ed.), Masculinity and femininity: The taboo dimension of national cultures (pp. 77-105). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2005). Geert Hofstede™ cultural dimensions. Retrieved March 20, 2005, from http://www.geert-hofstede.com

Jackman, M. (1994). The velvet glove: Paternalism and conflict in gender, class, and race relations. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jao, C., Lai, H., Tsai, W., & Wang, Y. (2003). Gender statistics and women’s status in Taiwan: An international comparison approach. Taipei, Taiwan: Bureau of Statistics, DGBAS.

Keinig, J. (1983). Paternalism. Totowa, NJ: Rowan and Allanheld.

Lim, C., & Lay, C. S. (2003). Confucianism and Protestant work ethic. Asia Europe Journal, 1, 321-322. Markus, H. R., & Kitayama S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation.

Okin, S. M. (1989). Justice, gender, and the family. New York: Basic Books.

Pratto, F., Liu, J. H., Levin, S., Sidanius, J., Shih, M., Bachrach, H., et al. (2001). Social dominance orientation and the legitimization of inequality across cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31, 369-409. Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality

vari-able predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741-763. Pratto, F., Tatar, D., & Conway-Lanz, S. (1999). Who gets what and why? Determinants of social allocations.

Political Psychology, 20, 127-150.

Pratto, F., & Walker, A. (2001). Dominance in disguise: Power, beneficence, and exploitation in personal rela-tionships. In A. Y. Lee-Chai & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The use and abuse of power: Multiple perspectives on the causes of corruption (pp. 93-114). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Raffaelli, M., & Ontai, L. L. (2004). Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles, 50, 287-299.

Sax, L. (2002). Maybe men and women are different. American Psychologist, 57, 444-456.

Sidanius, J., Levin, S., Federico, C. M., & Pratto, F. (2001). Legitimizing ideologies: A social dominance approach. In J. T. Jost & B. Major (Eds.), The psychology of legitimacy (pp. 307-331). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Swim, J. K., & Stangor, C. (1998). Introduction. In J. K. Swim & C. Stangor (Eds.), Prejudice: The target’s per-spective (pp. 1-8). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Tenenbaum, H. R., & Leaper, C. (2002). Are parents’ gender schemas related to their children’s gender related cognitions? A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 38, 615-630.

Triandis, H. C., McCusker, C., & Hui, C. H. (1990). Multimethod probes of individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1006-1020.

van den Berghe, P. (1967). Race and racism: A comparative perspective. New York: John Wiley. Wang, Y. K. (1999). [Women’s movement in Taiwan]. Taipei, Taiwan: Chu-Liu.

Wiener, R. L., Hurt, L., Russell, B., Mannen, K., & Gasper, C. (1997). Perceptions of sexual harassment: The effects of gender, legal standard, and ambivalent sexism. Law and Human Behavior, 21, 71-93.

Yang, K. S. (1992). [The social orientation of the Chinese: A perspective of social interactions]. In K. S. Yang (Ed.), [Chinese psychology and behavior: Theory and methodology] (pp. 87-142). Taipei, Taiwan: Guiguan Book Co. Yang, K. S., Yu, A. B., & Yeh, M. W. (1989). [The Chinese individual traditionality and modernity]. In K. S. Yang

& K. K. Hwang (Eds.), [Chinese psychology and behavior] (pp. 241-306). Taipei, Taiwan: Guiguan Book Co. Zhang, Y. B., Lin, M. C., Nonaka, A., & Beom, K. (2005). Harmony, hierarchy, and conservatism: A cross-cultural comparison of Confucian values in China, Korea, Japan, and Taiwan. Communication Research Report, 22, 107-115.

I-Ching Lee received her PhD in social psychology at the University of Connecticut in 2006, along with graduate certificates in women’s studies and quantitative research methods. She has received research grants from the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues (SPSSI) to study gender issues and intergroup relations. She is now assistant professor of psychology at National Chengchi University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Felicia Pratto is a professor of psychology at the University of Connecticut. She earned her PhD in social and personality psychology from New York University in 1988. She researches the dynamics of power and intergroup conflict, prejudice, discrimination, and cultural ideologies as pertinent to gender relations, interethnic relations, warfare, and substate terrorism. She currently serves on the Governing Council of the International Society of Political Psychology.

Mei-chih Li received her master’s degree in experimental psychology and social psychology separately from National Taiwan University and the University of Florida, Gainesville. Her PhD in social psychol-ogy was received from Pennsylvania State University. She has been the chief editor of Chinese Journal of Psychology, sponsored by Taiwanese Psychological Association, since 2003. Her research interests mainly focused on the perspective of Chinese indigenous culture and has spanned over to sex roles, five ethic interpersonal relationships, ethnic identification, and group relations.