Taiwanese College Te ache r s ’ Attitudes toward English Reading Instruction in their Discipline-Specific Areas

Tzung-yu CHENG

China Medical University, Taiwan Abstract

This study examined the attitudes of 137 Taiwanese college subject-area teachers toward teaching English reading in their discipline-specific areas. The results, based on a 12-item 7-point Likert scale survey, revealed that while college subject-area teachers regard content learning as their teaching priority, they acknowledge the importance of providing English reading instruction. The study found that despite the belief that English reading instruction can be incorporated into their courses and that there is a need for this, most teachers do not feel competent to teach such skills. The study concludes by identifying a direction for future research based on the experiences of college subject-area teachers.

1. Introduction

This study investigates the attitudes of Taiwanese college subject-area teachers

toward English reading instruction in their discipline-specific areas. The study is part

of a series of research designed to find out the best approaches to solving the dilemma

Taiwanese college students are confronted with: increasing demands for and lack of

training in reading discipline-specific texts in English. As Kasper (2000) points out,

the main goal of many ESL or EFL programs is to prepare students to pass the

TOEFL exam so that they may enter the academic mainstream in a native-English

speaking setting. However, once they succeed in entering college, major problems can

arise from the combined pressures of rigorous course content coupled with the

demands of academic English, and many students find their formal ESL/EFL

qualifications have failed to prepare them for survival.

In this paper, the context of this issue is presented, followed by a review of the

relevant research, and finally the study, which was carried out on a sample group of

137 Taiwanese college subject-area teachers. The study may be of interest to

educators in countries where students are facing the need to learn a new language

while simultaneously being required to comprehend texts in that language in order to

succeed academically, and where teachers are often bilingual and using texts written

in their second language. It is hoped that this preliminary research will lead the way to

large-g r oup s t udi e s f or be t t e r i ng not onl y EFL c ol l e ge s t ude nt s ’English proficiency

but also their efficiency in reading to learn from texts in English.

2. The context

The demand for English in Asia has increased dramatically since World War II.

An increasing number of countries, including the Philippines, Hong Kong, and

Singapore, now include English among their official languages, while others, such as

Indonesia and Malaysia, now demand English competence within government and

business (Ives, 2006). The English proficiency of these Southeast Asian countries has

facilitated a significant amount of trade with Australia and India. Across broader Asia,

the increasing use of English is displacing local languages, and it is expected that the

Chinese community will soon generally become bilingual (Pennycook, 2003).

The academic world of Mainland China and Taiwan has favoured the practice of

studying English scholarly works and publishing English papers in internationally

refereed journals (Li, 2002). As reported by Chen, Hu, and Liu (2008) and Hu, Chen,

and Liu (2008), colleges in Taiwan have been proposing the teaching of subject

content courses entirely in English as evidence of campus globalisation and academic

excellence. By the end of 2008, some top-ranked universities, such as National

Taiwan University, had announced that the number of courses instructed entirely in

English had reached 10%.

2.1. Two stages of reading development

Reading development consists of two stages: learning to read and reading to

learn (Singer & Donlan, 1989). During the first and second grades children learn to

read, but when children enter the third and fourth grades more emphasis is placed on

reading to learn from discipline-specific texts (Vacca, Vacca, & Gove, 1991). These

texts commonly include the natural sciences and social studies, which are diverse

fields with their own specialised vocabulary and concepts requiring special reading

skills (Dechant & Smith, 1961). Even within a native English setting, for many

children, the transition to discipline-specific texts leads to their first difficulties with

reading (Anderson, Hiebert, Scott, & Wilkinson, 1985). To cope with this problem,

pre-service and in-service science and social studies teachers are required to complete

a discipline specific reading methods course as a program endorsement (Christiansen,

1986; Stieglitz, 1983) and a number of subject-area reading and teaching strategies

have been proposed for secondary school as well as college and ESL/EFL students

(Echevarria, Vogt, & Short, 2000; Forget, 2004; Singer & Donlan, 1989; Vacca &

Vacca, 2007).

2.2. Stages of English learning in Taiwan

In Taiwan, however, English learning and instruction from elementary to senior high

school remains mainly within the first stage: learning to read. English subjects

represent only a small fraction of the compulsory courses for students. Children

usually begin learning English in Grade 3 and receive two hours of lessons per week

until the end of Grade 6. But as Gluck (2007) reported in the BBC News, over 60% of

families in cities begin private English classes when their children are at or below

kindergarten age. However, these courses are generally quite basic as Mandarin

Chinese is the official school language. Furthermore, the widespread use of local

Taiwanese dialects in the home, such as Min and Hakka, and the focus of elementary

schools on ensuring pupils meet Mandarin Chinese reading and writing standards,

mean that English learners in the 4-7 year old range receive little additional support.

Taiwanese middle and high schools offer six to ten hours of English instruction

per week as a compulsory foreign language course along with mathematics, biology,

physics, chemistry, Mandarin Chinese, history, geography, and civics, which are

instructed in Mandarin Chinese. It is common for students to seek additional private

English classes after school. However, Gluck (2007) reported that due to the design of

English exams in Taiwan, particularly the Na t i on’ s J oi nt High School and the

Na t i on’ s J oi nt Col l e ge Ent r a nc e Exa mi na t i ons , English instruction focuses on simple

rote-learning methods with students being required to memorise vocabulary and

grammar.

As Liaw (2007) points out, EFL students i n Ta i wa n “ may ha ve ye a r s of

experience being asked to engage in conversations and reading simple texts related to

functional language, but not necessarily higher-level thinking and content reading”(p.

57). Children in the EFL context do not study science, social studies, and mathematics

in English from Grade 1 to Grade 12 as do their peers in English-speaking countries.

Yet, Taiwanese students after entering college are faced with reading to learn from the

English-language discipline-specific textbooks that are not prepared for

non-first-language students, but were originally written for native English speakers.

No empirical studies, however, have documented whether the process of reading to

learn from Mandarin and English discipline-specific texts is identical and

interchangeable.

2.3. English te ac he r s ’ ability to teach discipline-specific reading

In the United States, college-trained English teachers are expected to know how

to teach reading skills to students despite only being trained in English content (Bintz,

1997). However, 5 out of 19 studies revealed that pre- and in-service English

teachers believe they are not appropriately qualified to effectively teach reading to

their students (Bintz, 1997). Similarly in Taiwan, junior and senior high school

English teachers are trained in English literature, linguistics, or TEFL methodologies

that focus on grammar, listening, writing, speaking, and reading. But they simply do

not have the required training for readying high school graduates for reading to learn

from content-area texts in English.

In light of the deficiencies in the current EFL educational framework, Taiwanese

college subject-area teachers should be invited to contribute to shaping a new teaching

model for tackling this dilemma. The reason for this is that many college teachers in

Taiwan have obtained their masters and doctoral degrees in foreign countries, in most

cases the United States, and in the process, they have had to develop their own

strategies for developing competence in reading English subject texts in order to

successfully graduate. Their experience in transitioning from the learning-to-read

phase to the reading-to-learn phase may provide valuable insights to assist current

students to successfully make the transition in the respective fields.

3. Review of the literature

Reading educators suggest that reading instruction in discipline-specific areas is

intended to help students acquire and refine the reading-to-learn strategies; to enable

students to learn faster, to retain and retrieve more information contained in different

styles of writing across the curriculum (Moore, Readence & Rickleman, 1983); to

provide students with the best avenue for learning (Simonson & Singer, 1992); and to

cope with the increasing literacy demand on jobs and in society (Clifford, 1984).

Studies on EFL students have documented that instructing through integrating reading

strategies while reading for content sign i f i ca nt l y i mpr ove s c ol l ege s t ude nt s ’ t e xt

comprehension as well as grammar and reading ability (Hudson, 1991). Many

content-based ESL programs have been offered to ensure a less abrupt transition from

the ESL classroom to the academic programs instructed entirely in English (Kasper,

2000; Mohan & Beckett, 2003; Montes, 2002).

3.1. Subject-area tea c her s ’ at t i t ude s t owar ds r eadi ng

In the native English setting, there has been a considerable amount of research

produced on subject-a r e a t e ac he r s ’ a t t i t ude s t oward reading instruction in their

discipline-specific areas. Research has documented that most elementary and

secondary school subject-area teachers in North America reported having positive

attitudes toward teaching reading in their major fields (Gillespie & Rasinski, 1989;

Lloyd, 1985; Shymansky, Yore, & Good, 1991; Yore, 1991). Yore (1991) surveyed

215 British Columbia secondary science teachers and found that science teachers

placed high value on reading as an important strategy to promote learning in science.

Science teachers generally accepted responsibility for teaching content reading skills

to science students. Shymansky, Yore, and Good (1991) also reported that most

kindergarten to eighth grade teachers had positive attitudes about science reading.

Lloyd (1985) found that most high school teachers also strongly agreed that teaching

reading skills is not a waste of time, and that reading teachers should not be the only

people to teach students how to study textbooks.

Other studies have documented that almost all undergraduate and graduate

students (Christiansen, 1986; Stieglitz, 1983) and junior and senior high school

teachers (Jackson, 1978) saw the benefits of completing a subject-area reading

methods course. They believed that a course in teaching reading should be required.

Moreover, pre-service teachers who had enrolled in a course in reading methods

changed their negative view toward teaching reading in the subject areas

(Christiansen, 1986; Stieglitz, 1983; Welle, 1981). Bean (2000) concluded that in

essence, pre-service teachers are likely to respond positively to strategies learned in

their university classes, but jettison most of these approaches in favour of more

didactic modes of instruction once they are at the school site.

Gillespie and Rasinski (1989) summarised that subject-area t e ac he r s ’attitudes

decrease with the increase of grade levels. They found this pattern of attitude shift:

elementary school teachers > middle school teachers > senior high school teachers.

This pattern is also an indication of the shift of the teaching priority between content

and reading instruction. Yet, as Singer and Donlan (1989) pointed out, subject-area

teachers who do teach reading contribute to both stages of reading development in

their students.

This review on subject-area t ea c her s ’ a t t i t ude s t owa r d r ea di ng i ns t r uc t i on reveals

that the studies are dated, but the results have been well-established, and are naturally

biased toward junior and senior high school teachers of science and social studies in

the English native setting. Hence we find a dearth of studies on this same topic in an

EFL context, particularly in college subject-area teachers who are also EFL learners

in Asian countries. For this reason, I have chosen to research this issue in the

Taiwanese context, as a step toward narrowing that research gap.

4. Methodology

4.1. The attitude scale

The survey consisted of a 12-item, 7-point Likert scale, which measures degrees

of agreement and disagreement. The items were chosen and adopted from Smith and

Ot t o’ s At t i t ude I nve nt or y ( 14 i t e ms ) ( Smi t h & Ot t o, 1969) , Us ova ’ s At t i t ude Sc a l e

(20 items) ( Us ova , 1979) , Va ugha n’ s Re a di ng Attitude Scale (15 items) (Vaughan,

1979) , a nd Si nge r ’ s At t i t ude s Sc a l e s f or Te achi ng St ude nt s Re a di ng ( 14 i t e ms )

(Singer & Donlan, 1989). The correlations among the four scales are at the 0.001

level of significance (Gillespie & Clements, 1991).

The items among the four scales are overlapping in nature and were written for

kindergarten to twelfth grade teachers in the United States. Therefore, in the present

study, to increase the content validity of the attitude scale, a panel discussion

consisting of the researcher and three college English teachers was held to select and

adopt the items believed to be the most appropriate for the teaching context in Taiwan.

Twelve items were finally agreed upon as the result of the discussion. The panel

discussion also suggested that “ r e a di ng t e a c he r s ” be changed i nt o “ Engl i s h t e a c he r s ”

a nd “ s ec onda r y s c hool ” i nt o “ c ol l e ge .” A field testing of the 12 items was further

executed on 10 college subject-area teachers (5 masters and 5 doctorates) to ensure

questions were easily comprehended and unambiguous.

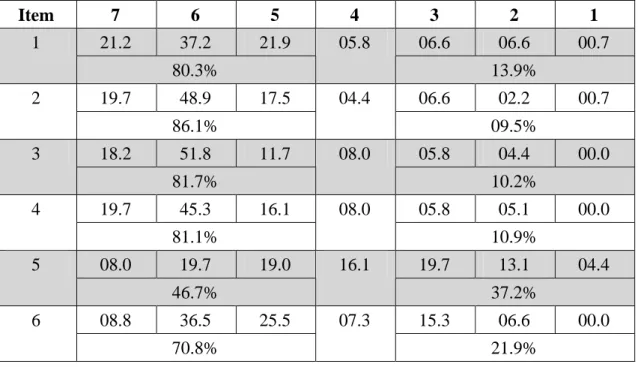

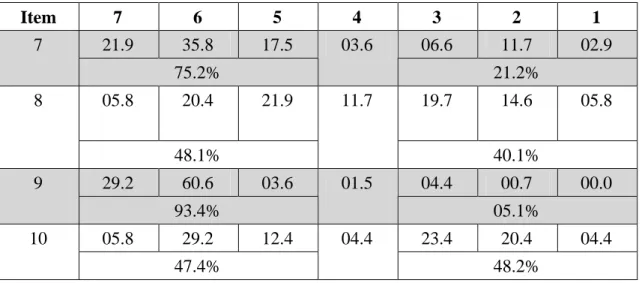

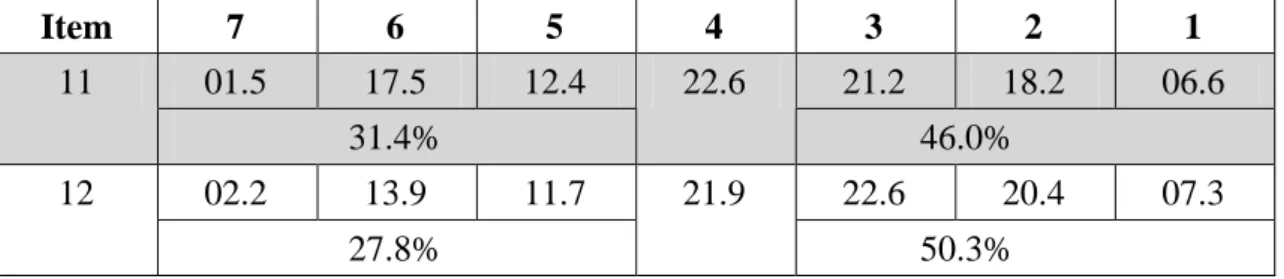

The 12 items addressed three areas: importance of English reading instruction in

the subject areas (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, & 6); responsibility of teaching priority (items 7,

8, 9, & 10); and competence in teaching English reading in the subject areas (items 11

& 12). Items 8, 9, and 10 were negative statements that addressed a teaching focus on

either content or reading/study skills. The final questionnaire was printed on a piece

of A4 paper with the following information listed on the top as the r es ponde nt ’ s

personal data: Highest Degree, Country Where Highest Degree Obtained, Years of

Teaching, Percent of English Texts Used in Class, and Major Field of Study. A space

at the bottom was also provided for the participants to make comments in the

language they felt comfortable and expressive.

4.2. Participants

The subjects were drawn from a public university in Taiwan. The university

accepts the upper 35% of high school and vocational high school graduates from the

Na t i on’ s J oi nt Col l e ge Ent r a nc e Exa mi na t i onheld annually in July. In the process of

selecting the pool of participants, first excluded were teachers who teach Chinese

literature, Chinese history, Chinese philosophy, arts, and English. Then 200 teachers

or about 70% were randomly selected from the pool of 282 teachers.

In gathering the data, a questionnaire with a cover letter and a return envelope

was d e l i ve r e d t o e a c h of t he t e a c he r s ’ of f i c e s . Two we e ks l a t er , 143 teachers returned

their questionnaires. The return rate was 71.5%, and 137 questionnaires were found

useful for the final data analysis. Ta bl e 1 pr e s e nt s a de s c r i pt i on of t he r es ponde nt s ’

characteristics.

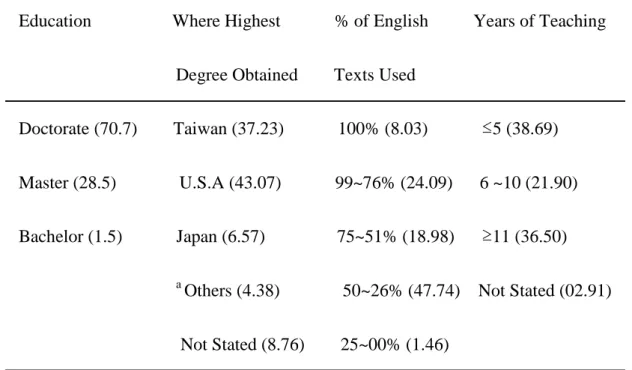

Table 1: Respondents’Characteristics by Percent (N = 137)

Education Where Highest % of English Years of Teaching

Degree Obtained Texts Used

Doctorate (70.7) Taiwan (37.23) 100% (8.03) ≤5 (38.69)

Master (28.5) U.S.A (43.07) 99~76% (24.09) 6 ~10 (21.90)

Bachelor (1.5) Japan (6.57) 75~51% (18.98) ≥11 (36.50)

a

Others (4.38) 50~26% (47.74) Not Stated (02.91)

Not Stated (8.76) 25~00% (1.46)

a