行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

英語聽力與口說能力相關性之探究

計畫類別: 個別型計畫

計畫編號: NSC94-2411-H-011-012-

執行期間: 94 年 08 月 01 日至 95 年 07 月 31 日 執行單位: 國立臺灣科技大學應用外語系

計畫主持人: 鄧慧君

報告類型: 精簡報告

處理方式: 本計畫可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 95 年 8 月 7 日

關鍵詞: 英語聽力、口說能力

本研究之目的為探討外語學習者英語聽力理解能力和口語表現之關係。主要的研究 問題分別是:(1)受測者的英語聽解能力與回答問題之間是否有顯著之關係?(2)受測者 的英語聽解能力與覆誦之間是否有顯著之關係?(3)英語聽力高成就和低成就的受測者 在回答問題的表現上是否有顯著的差異?(4)英語聽力高成就和低成就的受測者在覆誦 的表現上是否有顯著的差異?本研究的受測對象將為 40 位就讀於中台灣某所高中的高 一學生。所採用的研究工具為相當於全民英檢初級程度的聽力測驗,測驗結果將用來標 示受測者的英語聽解能力為較高能力及較低能力。另一研究工具則為包含覆誦與回答問 題之全民英檢初級口語測驗。本研究將於高一的「英語會話」課進行,受測者將先接受 聽力測驗、覆誦以及回答問題測驗,然後完成影響覆誦和回答問題表現因素之問卷,最 後,十位受測者將接受訪談,藉以瞭解影響他們口語表現之因素。相關係數及變異數分 析將用來考驗英語聽解能力與口語能力之顯著關係。本研究之結果可提供外語聽力與口 語能力之實驗性證據,及英語聽講教學上的一些啟示。

Keywords: EFL Listening Proficiency, Speaking Performance

The purpose of the present study is to examine the relationship between EFL learners’

listening proficiency and speaking performance. The major research questions explored in the study will be: (1) Is there any significant correlation between EFL listening proficiency and the performance in answering questions? (2) Is there any significant correlation between EFL listening proficiency and the performance in repetition? (3) Are there any significant

differences in the task of answering questions between proficient and less proficient EFL listeners? (4) Are there any significant differences in the task of repetition between proficient and less proficient EFL listeners? Subjects in the study include 40 first grade students from a senior high school in central Taiwan. One instrument adopted in the study is a listening test of GEPT elementary level, which will designate subjects EFL listening proficiency as proficient and less proficient. Another is a speaking test of GEPT elementary level, which consists of repetition and answering questions. A questionnaire is also designed to examine the factors which affect subjects’speaking performance.The study will be conducted during the class

English Conversation. The subjects will first take the EFL listening test, repetition test, and

answering question test and then complete the questionnaire. Finally, an interview will be held with ten of the subjects to probe the possible factors affecting their performances of repetition and answering questions. Significant links between EFL listening proficiency, repetition, and answering questions will be explored using correlational tests and analysis of variance. Results of the study can provide empirical description for the relationship between EFL learners’listening proficiency and speaking performance. Results are also expected to offer some implications for the instruction of EFL listening and speaking.INTRODUCTION

Since communicative approach was adopted and promoted in Taiwan, listening and speaking have received great emphasis. According to Brumfit (1984) and Brown (2001), listening and speaking are treated as intertwined and reticulate conversational skills. However, when concerning the nature of speaking and listening, it would be more reasonable if

speaking tests involve listening components. Repetition task is a variation of the dictation test (Lin, 2003). Test-takers repeat the text orally during the pause between each section after listening to passages. Besides, answering questions is another test type in which after examinees listen to the questions recorded on the tape, they need to make appropriate responses orally in a given short span of time.

Morley (2001) and Yen & Shuie (2004) claimed that listening is regarded as a means to speaking. It involves on-line processing of acoustic input and audible symbols (Buck, 1992;

Brown, 2001) in which the learners have to participate fully in selecting the stimuli to which they will attend to and assign meanings to those stimuli (Berne, 1998). Without listening, people could not produce language (Brown, 2001). According to Clark & Hecht (1983), two distinct processes, production and comprehension, must be coordinated to make the use of language successful. Without coordination, speakers would be unable to communicate and to infer meanings and intentions from interlocutors.

Due to the fact that listening is not a one-way tunneland speaking ability can’tbe evaluated alone, repetition and answering questions are the joint test types which can be used to assessboth ofexaminees’listening and speaking ability atthesametime. As a result, the presentstudy aimed to examinetherelationship between EFL learners’listening proficiency and speaking test performance. The main research questions explored in the study included:

(1) Is there any significant correlation between EFL listening proficiency and the

performance in repetition? (2) Is there any significant correlation between EFL listening proficiency and the performance in answering questions? (3) Are there any significant differences in the test of repetition between proficient and less proficient EFL listeners? (4) Are there any significant differences in the test of answering questions between proficient and less proficient EFL listeners? (5) Which test type, repetition or answering questions, is

influenced more by listening proficiency?

According to Chastin (1976), listening skill serves as the basis for the development of speaking skill, and oral communication is impossible without a listening skill that is much more highly developed than the speaking skill (Yen & Shiue, 2004). However, very few studies have been conducted to examine the relationship between listening and speaking.

Thus, the present study sought to contribute to the understanding of the relationship between EFL learners’listening proficiency and speaking test performance.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Speaking and listening are the instruments people use for performing global activities.

Research has demonstrated that adults spend 40-50% of communication time listening, 25-30% speaking, 11-16% reading, and about 9% writing (Rivers, 1984, cited from Vandergrift, 1999, p. 169). From the statistics, it can be concluded that listening skill is as important as speaking skill because people cannot communicate face-to-face successfully unless the two types of skill are both developed (Anderson & Lynch, 1988).

In speaking, meaning is turned into sounds, and in listening, sounds are turned into meaning. At the meaning end, speakers begin with the purpose of influencing listeners and turn this purpose into a plan of an utterance;atthe otherend,listenersrecognizethespeakers’ plan and infer their intentions (Clark & Clark, 1977). In other words, for speaking, word

meaning is activated prior to information about syntax and phonology. Listening, on the other hand, involves phonological processing before meaning activation (Rodriguez-Fornells et al., 2002). However, when producing an oral message or receiving an aural information, it demands that the speaker and listener must draw upon a knowledge of both the world and the language (Lin, 1998). Through viewing the characteristics of these two skills, speaking and listening has been regarded as two sides of the same coin of communication, in which they share a closely knit relationship (Lin, 1998).

The current study focused on figuring out the correlation between EFL listening

proficiency and performance of repetition and answering questions. Several researchers have conducted studies on sentence-repetition. Firstly, Fabbro et al. (2002) compared the capacity to repeat verbal stimuli in the mother tongue (Italian) and in unfamiliar foreign language (English and German)acrossWilliam’sSyndrome subjects,Down’sSyndromesubjectsand mental-age-matched control subjects. Moreover, Small et al. (2000) studied the sentence repetition and processing resourcesin Alzheimer’sdisease.Finally,Lin’sstudy (2003) examines if repetition can be used as a means of measuring EFL listening comprehension.

The results show that not only the listen & repeat test is highly connected with the listening testbutalso subjects’repetition production isrelated to theirlistening proficiency levels.Asa result,thelisten & repeattestcan beadopted to assesstestee’slistening comprehension.

To sum up, communication is a process involving at least two people. Only when what is said is comprehended by another person can he/she achieve the goal of communication.

With the task of answering questions, testers not only can evaluate if testees understand the questions but also can assess their oral performance. As for repetition, Buck (2001) indicated that the sentence-repetition task is essentially an integrated test, testing not only oral but listening skills.

METHODOLOGY

Subjects

The subjects were 32 first-grade students from the same class of a vocational high school in central Taiwan, majoring in international trade. All of the subjects have been receiving formal English teaching for at least three years. They were now having six hours of English class at school per week and were 15 or 16 years of age.

Instrumentation

The instruments adopted in the present study included the listening comprehension test, the tests of repetition, answering questions, the questionnaire, and the interview guide. Tests of listening comprehension, repetition, and answering questions were adopted from the elementary level of General English Proficiency Test (GEPT). The listening comprehension test was a 30-item, audio-recorded, three-option multiple-choice listening test. The response options were done in the medium of print. A male and a female American speaker took turns at delivering all of the questions. Besides, according to Pimsleur et al. (1977), the speaking pace of about 140 wpm was moderately slow (cited from LTTC, 2000). Each correct answer was distributed with four points. Thus, the total score of the listening comprehension test was 120 points.

The second instrument was the task of repetition which included 10 sentences. Each sentence, less than five words, was played twice. After receiving the aural stimuli, testees repeated the sentences immediately. The scoring criterion set by the Language Training &

Testing Center (LTTC) wasused to gradetesttakers’performance of repetition. It concerned abouttesttakers’pronunciation,intonation,and fluency,and contains six ranks, 0-5. Each rank was equal to 2 points, except rank 0. Thus, the total score of repetition was 100 points.

The third instrument was the task of answering questions. It comprised of five questions in which each question was played twice. Testees were given 15 seconds to make responses after hearing a beep sound. The scoring criterion set by LTTC wasused to gradethesubjects’ performance of answering questions. It concerned abouttesttakers’correctand appropriate usage of grammar and vocabulary, and also included six ranks, 0-5. Each rank was equal to 4 points, except rank 0. Thus, the total score of repetition was 100 points.

Another instrument was the questionnaire based on Teng (1999) to investigate the possible factors affecting the performance of repetition and answering questions. It was designed with the Likert scale on a five-point scale from strongly agree (SA) to strongly disagree (SD). The main contents of the questionnaire were divided into two parts which included the possible factors affecting the tasks of repetition and answering questions

respectively. Besides, the questionnaire was written in Chinese to be administered easily and to facilitate the validity of questionnaire.

In order to get more specific information aboutthesubjects’perceptionstoward thethree tests and the relationship among them, an interview was also adopted in the present study.

Ten interviewees were randomly selected among the 32 subjects. Furthermore, the interview guide was also written in Chinese to be administered easily and to facilitate the validity of

interview.

Procedures

Thecurrentstudy wasconducted in subjects’English conversation class.Atthe beginning of the study, subjects were informed about the tests they were going to take, the purposes of the tests, and the procedures. Subjects first took the listening comprehension test in the language lab. Then subjects were asked to perform the tasks of repetition and

answering questions. Their oral responses were audio-recorded in order to assess their speaking performance. After taking the tasks of repetition and answering questions, subjects were requested to fill out the questionnaire at the end of the experiment. At the last stage, ten interviewees were randomly selected among the 32 subjects and the ten interviewees were interviewed one by one. The interviews were audio-taped and transcribed.

Data Analysis

Two ratersgraded subjects’performancesin repetition and answering questions separately. Then, Pearson Product-Moment Correlation, Spearman Rank Correlation and one-way ANOVA were employed for analyzing the collected data, i.e., the tests of listening comprehension, repetition, and answering questions in order to figure out the correlation between EFL listening comprehension, repetition, and answering questions and to point out if there is any significant difference between subjects with high and low EFL listening

proficiency. For the questionnaire, the response to every item were counted to calculate the average of agreement to specify the possible factors affecting the tasks of repetition and answering questions. The numberofsubjectswho chose“strongly agree”and “agree”was combined to form anew category “agree”and who chose“disagree”and “strongly disagree” was also put togetheras“disagree”.“Undecided” remained thesame.As to the interview data, they would be transcribed and added to the study as the supplementary information.

RESULTS

Test Scores of the three Tests

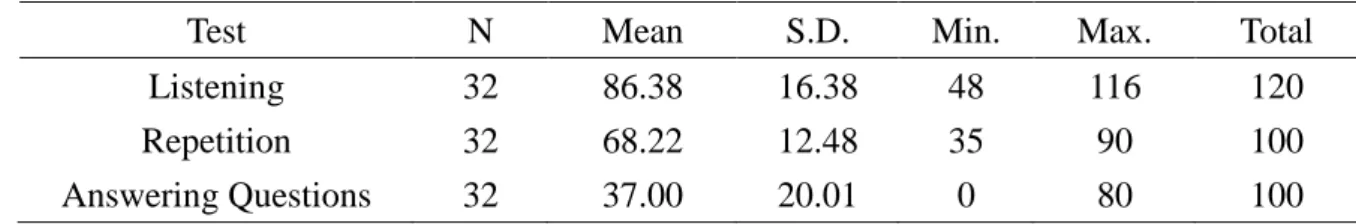

Firstly, Table 1 displayed the descriptive statisticsofthesubjects’performanceson the three tests. The average scores on the listening test is 86.38. Besides, the subjects got higher average scores on the task of repetition (M=68.22) than on the task of answering questions (M=37.00).

Table 1 Descriptive Statistics of Test Scores

Test N Mean S.D. Min. Max. Total

Listening 32 86.38 16.38 48 116 120

Repetition 32 68.22 12.48 35 90 100

Answering Questions 32 37.00 20.01 0 80 100

Next, the results of Pearson Correlation and Spearman Rank Correlation (see Table 2 &

Table 3) indicated thatthesubjects’listening comprehension scoreswereclosely related to their scores of repetition (r =.573, p =.001) and also highly connected with their scores of answering questions (r =.718, p =.000). Besides, the rank of listening comprehension and the rank of repetition were correlated as well (r =.620, p =.000) and the rank of listening

comprehension and the rank of answering questions intertwined with each other (r =.678, p

=.000).

Table 2 Pearson Correlation of Test Scores

Repetition Answering Questions

Pearson (r) .573** .718**

Listening

Comprehension p value .001 .000

** p<0.01

Table 3 Spearman Rank Correlation of Test Scores Rank of

Repetition

Rank of Answering Questions

Pearson (r) .620** .678**

Rank of Listening

Comprehension p value .000 .000

** p<0.01

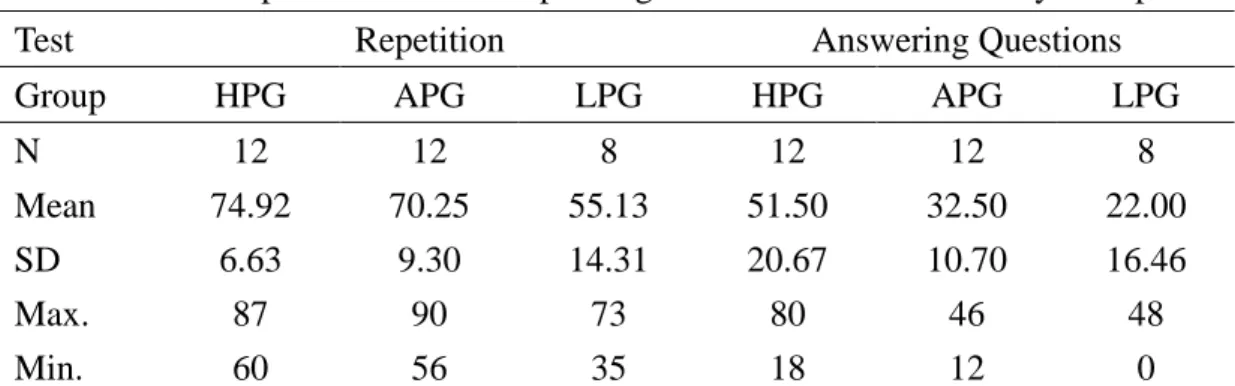

Furthermore, the subjects were classified into three groups, i.e., high-proficient group (HPG), average-proficient group (APG), and less-proficient group (LPG) according to their scores of listening comprehension. Both HPG and APG had 12 subjects and LPG included eight subjects because there were several subjects who got the same scores in listening comprehension. It was inappropriate to divide the subjects who got the same scores into different groups. Thus, LPG only had subjects of 12 students. Descriptive statistics in Table 4 below displayed that high-proficient subjects (M=74.92; M= 51.50) outperformed

average-proficient subjects and less-proficient subjects on the tasks of repetition and answering questions.

Table 4 Descriptive Statistics of Speaking Test Scores for Proficiency Groups

Test Repetition Answering Questions

Group HPG APG LPG HPG APG LPG

N 12 12 8 12 12 8

Mean 74.92 70.25 55.13 51.50 32.50 22.00

SD 6.63 9.30 14.31 20.67 10.70 16.46

Max. 87 90 73 80 46 48

Min. 60 56 35 18 12 0

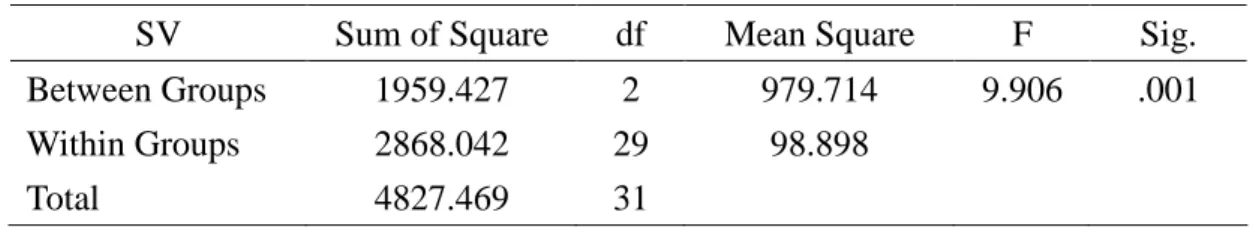

Moreover, one-way ANOVA was conducted to determine if there were any significant differencesin subjects’performanceson thetestsofrepetition,answering questions,and subjects’listening proficiency. As Table 5 & Table 6 revealed, scores on the tasks of

repetition and answering questionswerediscriminated significantly by thesubjects’listening proficiency levels (p = .001).

Table 5 Results of One-Way ANOVA for Repetition

SV Sum of Square df Mean Square F Sig.

Between Groups 1959.427 2 979.714 9.906 .001

Within Groups 2868.042 29 98.898

Total 4827.469 31

Table 6 Results of One-Way ANOVA for Answering Questions

SV Sum of Square df Mean Square F Sig.

Between Groups 4566.000 2 2283.000 8.434 .001

Within Groups 7850.000 29 270.690

Total 12416.000 31

Finally, the tasks of repetition and answering questions formed the speaking test in the presentstudy.Both ofrepetition and answering questionswereused to evaluatethesubjects’ speaking proficiency. As the result indicated, the tasks of repetition and answering questions also correlated remarkably (r =.623, p =.000).

Results of the Questionnaire

In terms of the possible factors affecting repetition, findings revealed that among the 14 items,“Feelnervous”ranked thehighest,followed by “Ican’trepeatsentencesfluently”and

“Short-memory is too limited”.In addition,as for the possible factors affecting answering questions, results showed that“Can’texpressmy ideabecauseoflimited vocabulary” and

“Limited timebeforeresponding”had thehighestdegreeofagreement.Nextwas“Notused to speak in English”,followed by “Ican’texpressmyselffluently”.

Results of the Interview

Seven out of ten subjects agreed that their performances of repetition were influenced by their listening proficiency because they firstly needed to pay attention to the intonation and pronunciation of the vocabulary and to connect the vocabulary into sentences. Then, they could repeat the sentences. Besides, eight out of ten interviewees considered that their

listening proficiency played important roles when performing the task of answering questions becauseifthey didn’tunderstand themeaningsofthequestions,they couldn’tanswerthem.

Moreover, nine out of ten subjects regarded the task of answering questions was more difficult than the task ofrepetition forthey stillcould repeatthesentencesifthey didn’t understand the meanings of these sentences. However, in the task of answering questions, subjects must first understand the meanings of the questions, search for the answers and sentence patterns and then make responses. Additionally, eight out of ten interviewees reflected the task of answering questions was influenced more significantly by their English listening proficiency. In their opinions, they must know what the sentences were asking. Then,

they could try to answer the questions.

DISCUSSION

The results of Pearson Correlation and Spearman Rank Correlation revealed that there was a significant correlation between EFL listening proficiency and the performance in repetition. The result was congruent with the research conducted by Lin (2003), which indicated that the seniorhigh schoolstudents’repetition scoreswereclosely related to their English listening comprehension scores. Moreover, the findings showed that there was a significant correlation between EFL listening proficiency and the performance in answering questions as well. In other words, there could be no production unless linguistic input became comprehensible intake for a listener (Byrnes, 1984).

According to the results of one-way ANOVA, there were significant differences in proficientand lessproficientEFL listeners’performanceson thetask ofrepetition.In thetask of repetition, HPG (M=74.92) outperformed APG (M=70.25) and LPG (M=55.13). The results from the present study might be parallel to the findings of Lin (2003). As Lin

mentioned, high-proficiency subjects outperformed in the Listen & Repeat test, implying that the discrepancy of language proficiency levels still distinguished the performances on the Listen & Repeat test. Based on Aitchison (1994), the process of listening comprehension can be divided into two stages: recognizing and grasping. That is, recognizing words which have been spoken, and grasping their meanings. However, the repetition task in the present study concerned with the first stage of listening comprehension. So, subjects still could repeat the sentences even though they did not successfully interpret the meanings of the sentences.

Furthermore, from the results of one-way ANOVA, it uncovered the facts that there were significant differences in the task of answering questions between proficient and less

proficient EFL listeners. Namely, high proficient listeners seemed performed significantly better on the task of answering questions than average proficient and low proficient listeners.

Differently from the task of repetition, EFL listeners must first recognize the word which has been spoken and grasp its meaning as well in the task of answering questions. Hence, EFL listeners have to fully comprehend the questions, and that is considered the most important thing in the task of answering questions. Then, they can proceed to the second step by providing appropriate responses.

According to the results of Pearson Correlation, answering questions (r =.718, p =.000) was more highly intertwined with English listening proficiency than the task of repetition (r

=.573, p =.001). That is, the task of answering questions was influenced more by listening proficiency than repetition was. The findings may be attributed to the process of listening comprehension in which the subjects need to receive the sounds of the words and assign meanings to them. As a result, the subjects could achieve full comprehension of the sentences and make further responses.

The present study used questionnaire as the instrument to probe into the possible factors affecting thesubjects’performancesin repetition,“Feelnervous”ranked the highest.

According to the previous studies (Phillips, 1992; Sato, 2003), speaking in the foreign language produced the most anxiety. The anxiety they experienced might have a debilitating impacton theirability to speak.Based on Phillips’study (1992),there was a significant

inverserelationship between thestudents’expression oflanguageanxiety and theirability to perform on the oral exam. Sato (2003) also declared that reducing learner anxiety enhances students’learning to speak.

As to the questionnaireexamining thesubjects’perceptionstoward thepossiblefactors affecting answering questions,“Can’texpressmy ideabecauseoflimited vocabulary” and

“Limited timebeforeresponding”ranked thehighest.Wilkin (1972)pointed outthatin conversations, people can only convey little information without the knowledge of grammar butwithoutvocabulary nothing can beconveyed (cited from Huang,2000).In Huang’sstudy (2003), senior high school students in Taiwan, on the average, recognized nearly 2,000

high-frequency words and only 112 general academic terms. The result revealed that their vocabulary size failed to reach the required threshold. Moreover, both Huang (1999) and Lin (1995) found that Taiwanese students at the senior high instructional level do not have good English performance due to the deficiency of vocabulary knowledge (cited from Huang, 2003). Denton and Tang (2004) indicated the lack of internalized vocabulary may be a significant factor in conversational skill deficiencies for many Taiwanese students of EFL intermediate levels as well. On the other hand, speakers were not fluent when they had

difficulty planning within the time limits expected of them (Clark, 2002). In the current study, the subjects were given 15 seconds to make responses after hearing the questions. Through the questionnaire, it can be concluded that the time prior to responding should be longer than 15 seconds in order for the subjects to organize their ideas more thoroughly.

Some limitations can still be noted on the design of the present study. First, with the limit on the sample size, the findings may be difficult to be generalized to other population of EFL learners. Hence, future researches could enlarge the sample size of subjects and recruit the subjects from different majors in vocational high schools and different areas in Taiwan.

Moreover, it could be recommendable to adopt senior high school students as the subjects in the future study.

The other limitation is that the study focuses on grading the subjects’repetition performances. It is recommended that after repeating the sentences, subjects can write down the meanings of the sentences in order to check if they indeed comprehend the sentences or just make rote repetition. Similarly, after subjects provide responses to the questions in the task of answering questions, they may note down the meanings of the sentences. By doing so, it can help the researcher clarify if the subjects fail to provide responses owing to the fact that the subjects do not understand the meanings of the sentences. Moreover, the researcher could

tell if the subjects lack of oral skills to express their ideas thoroughly although they can comprehend the questions played on the tape or CD.

CONCLUSION

Based on the findings derived from the present study, several pedagogical implications are proposed for teaching and learning EFL oral skills. Firstly, listening proficiency should be developed on the basis of other language skills through face-to-face interaction and through focusing on meaning. As James (1984) indicated, listening cannot be learned without reference to other language skills.

Secondly, according to the above statement, teachers can adopt either the task of

repetition or the task of answering questions to assess students’English listening proficiency because the results of the present study revealed that the speaking tests are highly correlated with EFL listening proficiency. Thus, through the speaking tests, teachers not only can evaluatestudents’listening proficiency but also their speaking skills at the same time.

Finally, it was evident that many of the subjects have insufficient vocabulary sizes. So, even they understood the meanings of the sentences in the task of answering questions, they did not know how to convert their ideas into English sentences owing to lack of vocabulary knowledge. English teachers could encourage students to do extensive reading to enlarge their vocabulary sizes because learning from context can facilitate vocabulary knowledge (Sternberg and Powell, 1983). Moreover, when memorizing vocabulary, students need to know how to pronounce the words instead of doing rote memorization.

REFERENCES

Aitchison, J. (1994). Understanding words. In G. Brown, K. Malmkjær, A. Pollitt & J.

Williams (Eds.), Language and Understanding (pp. 83-95). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, A., & Lynch, T. (1988). Listening. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Berne, J. E. (1998). Examing the relationship between L2 listening research, pedagogical theory, and practice. Foreign Language Annals, 31(2), 169-190.

Brown, H. D. (2001). Teaching by principles: An interactive approach to language pedagogy, 2nd ed. NY: Pearson Education.

Brumfit, C. (1984). Communicative methodology in language teaching: The Roles of Fluency

and Accuracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Buck, G. (1992). Listening comprehension: Construct validity and trait characteristics.

Language Learning, 42(3), 313-357.

Buck, G. (2001). Assessing listening. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Byrnes, H. (1984). The role of listening comprehension: A theoretical base.

Foreign Language Annals, 17(4), 317-329.

Clark, H. H., & Clark, E.V. (1977). Psychology and language: An introduction to

psycholinguistics. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Clark, E. V., & Hecht, B. F. (1983). Comprehension, production, and language acquisition.

Annual Reviews Psychology, 34, 325-349.

Clark, H. H. (2002). Speaking in time. Speech Communication, 36, 5-13.

Denton, J. E., & Tang, H. F. (2004). Core English vocabulary: The missing factor. The 21st

International Conference on English Teaching & Learning in the Republic of China,

117-126. Taipei: the Crane Publishing Co., Ltd.Fabbro, F., Alberti, B., Gagliardi, G., & Borgatti, R. (2002). Differences in native and foreign languagerepetition tasksbetween subjectswith William’sand Down’ssyndromes.

Journal of Neurolinguistics, 15, 1-10.

Huang, C. C. (2000). A threshold for vocabulary knowledge on reading comprehension.

Proceedings of the Seventeenth Conference on English Teaching and Learning in the Republic of China (pp. 132-144). Taipei, Taiwan: Crane.

Huang,C.C.(2003).Seniorhigh students’vocabulary knowledge,contentknowledge,and reading comprehension. Selected papers from the twelfth International Symposium on

English Teaching, 391-4

02.Taipei:English Teachers’Association.James, C. J. (1984). Are you listening? The practical components of listening comprehension.

Foreign Language Annals, 17, 129-133.

Lin, L. Y. (1998). Improving listening comprehension using essential characteristics of oral production. Hwa Kang Journal of TEFL, 4, 55-71.

Lin, Y. L. (2003). Repetition as a Means of Measuring EFL Listening Comprehension. Master Thesis: National Kaohsiung Normal University.

LTTC. (2000). Research report for GEPT elementary level. Available:

http://www.lttc.ntu.edu.tw/academics/research.htm

Morley, J. (2001). Aural Comprehension Instruction: Principles and Practices. In

Celce-Murica, M. (ed.), Teaching English as a Second Foreign Language, 3rd ed.

Boston: Heinle & Heinle.

Phillips,E.M.(1992).Theeffectsoflanguageanxiety on students’oraltestperformanceand attitudes. The Modern Language Journal, 76(1), 14-26.

Rodriguez-Fornells, A., Schmitt, B. M., Kutas, M., & Munte, T. F. (2002).

Electrophysiological estimates of the time course of semantic and phonological encoding during listening and naming. Neuropsychologia, 40, 778-787.

Sato,K.(2003).Improving ourstudents’speaking skills:Using selectiveerrorcorrection and group work to reduce anxiety and encourage real communication.

ERIC Digest. ERIC, ED 475518.

Small, J.A., Kemper, S., & Lyons, K. (2000). Sentence repetition and processing resources in Alzheimer’sdisease.

Brain and Language, 75, 232-258.

Sternberg, R. J., Powell, J. S. (1983). Comprehending verbal comprehension. American

Psychologist, 38(8), 878-893.

Teng, H.C. (1999). The Effects of syntactic modification and speech rate on EFL listening

comprehension. Taipei: the Crane Publishing Co., Ltd.

Yen, A. L., & Shiue, S. M. (2004). A study on English listening difficulties encountered by FHK students. Selected papers from the twelfth International Symposium on English

Teaching, 699-7

07.Taipei:English Teachers’Association.EVALUATION of RESULTS

The results of the present study are expected to have the following contributions:

(1) In the area of listening research, to provide empirical evidences for the effect of listening proficiency on speaking performance;

(2) In the area of second language acquisition (SLA) research, to investigate the relationship between EFL listening comprehension and speaking ability; and (3) In the area of instructional implications, to help EFL students effectively improve

their performance in speaking tests through facilitating their listening skills.

The expected training for the working members involved in the present study includes the following tasks:

(1) To learn how to administer EFL listening and speaking tests;

(2) To know how to design the format of questionnaires;

(3) To study how to conduct statistical analysis; and (4) To practice how to transcribe the interview.