o r i g i n a l a r t i c l e

The n e w e n g l a n d j o u r n a l of m e d i c i n eAdefovir Dipivoxil for the Treatment

of Hepatitis B e Antigen–Positive

Chronic Hepatitis B

Patrick Marcellin, M.D., Ting-Tsung Chang, M.D., Seng Gee Lim, M.D., Myron J. Tong, Ph.D., M.D., William Sievert, M.D., Mitchell L. Shiffman, M.D.,

Lennox Jeffers, M.D., Zachary Goodman, M.D., Ph.D., Michael S. Wulfsohn, M.D., Ph.D., Shelly Xiong, Ph.D., John Fry, B.Sc., and Carol L. Brosgart, M.D., for the Adefovir Dipivoxil 437 Study Group*

From the Service d’Hépatologie, INSERM Unité 481, and Centre de Recherches Claude Bernard sur les Hépatites Virales, Hôpital Beaujon, Clichy, France (P.M.); the Depart-ment of Internal Medicine, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan (T.-T.C.); the Division of Gastroenterology, National University Hospital, Singapore (S.G.L.); the Liver Center, Huntington Med-ical Research Institutes, Pasadena, Calif. (M.J.T.); the Department of Medicine, Monash University and Monash Medical Centre, Melbourne, Australia (W.S.); the Division of Gastroenterology, Virginia Com-monwealth University Health System, Rich-mond (M.L.S.); the Center for Liver Diseas-es, University of Miami School of Medicine, and the Miami Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Miami (L.J.); the Armed Forces In-stitute of Pathology, Washington, D.C. (Z.G.); and Gilead Sciences, Foster City, Calif. (M.S.W., S.X., J.F., C.L.B.). Address reprint requests to Dr. Marcellin at the Serv-ice d’Hépatologie, INSERM Unité 481, and Centre de Recherches Claude Bernard sur les Hépatites Virales, Hôpital Beaujon, 100 Blvd. du Général Leclerc, 92110 Clichy, France, or at marcellin@bichat.inserm.fr. *Other members of the Adefovir

Dipivox-il 437 Study Group are listed in the Ap-pendix.

N Engl J Med 2003;348:808-16.

Copyright © 2003 Massachusetts Medical Society.

b a c k g r o u n d

In preclinical and phase 2 studies, adefovir dipivoxil demonstrated potent activity against hepatitis B virus (HBV), including lamivudine-resistant strains.

m e t h o d s

We randomly assigned 515 patients with chronic hepatitis B who were positive for hep-atitis B e antigen (HBeAg) to receive 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil (172 patients), 30 mg of adefovir dipivoxil (173), or placebo (170) daily for 48 weeks. The primary end point was histologic improvement in the 10-mg group as compared with the placebo group. r e s u l t s

After 48 weeks of treatment, significantly more patients who received 10 mg or 30 mg of adefovir dipivoxil per day than who received placebo had histologic improvement (53 percent [P<0.001], 59 percent [P<0.001], and 25 percent, respectively), a reduction in serum HBV DNA levels (by a median of 3.52 [P<0.001], 4.76 [P<0.001], and 0.55 log copies per milliliter, respectively), undetectable levels (fewer than 400 copies per millili-ter) of serum HBV DNA (21 percent [P<0.001], 39 percent [P<0.001], and 0 percent, re-spectively), normalization of alanine aminotransferase levels (48 percent [P<0.001], 55 percent [P<0.001], and 16 percent, respectively), and HBeAg seroconversion (12 percent [P=0.049], 14 percent [P=0.01], and 6 percent, respectively). No adefovir-associated resistance mutations were identified in the HBV DNA polymerase gene. The safety pro-file of the 10-mg dose of adefovir dipivoxil was similar to that of placebo; however, there was a higher frequency of adverse events and renal laboratory abnormalities in the group given 30 mg of adefovir dipivoxil per day.

c o n c l u s i o n s

In patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B, 48 weeks of 10 mg or 30 mg of adef-ovir dipivoxil per day resulted in histologic liver improvement, reduced serum HBV DNA and alanine aminotransferase levels, and increased the rates of HBeAg seroconversion. The 10-mg dose has a favorable risk–benefit profile for long-term treatment. No adef-ovir-associated resistance mutations were identified in the HBV DNA polymerase gene.

a d e f o v i r d i p i v o x i l f o r c h r o n i c h e p a t i t i s b

ore than 350 million people worldwide have chronic hepatitis B virus

(HBV) infection.1 Effective treatments

are required to prevent progression of chronic hep-atitis B to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and death. Treatment with interferon alfa requires par-enteral administration and can cause side effects, such as influenza-like symptoms, anorexia, and de-pression, that require an adjustment in the dose or discontinuation of therapy.2 The risk of progressive

liver damage decreases in patients who have hep-atitis B e antigen (HBeAg) seroconversion after in-terferon therapy. Lamivudine suppresses HBV

rep-lication and improves histologic liver findings.3

However, lamivudine resistance has been reported in up to 32 percent of patients after one year of ther-apy4 and in 66 percent after four years.5 Some

pa-tients with lamivudine resistance have had a severe exacerbation of hepatitis and progressive liver dis-ease.6 Therefore, well-tolerated antiviral agents that

provide clinical benefit without inducing resistance are needed to manage chronic hepatitis B.

Adefovir dipivoxil (Hepsera, Gilead Sciences) is an oral prodrug of adefovir, an analogue of adeno-sine monophosphate. The active intracellular me-tabolite, adefovir diphosphate, inhibits HBV DNA polymerase at levels much lower than those needed to inhibit human DNA polymerases. In phase 2 studies, daily doses of 30 mg and 60 mg of adefovir dipivoxil inhibited HBV replication, reducing serum HBV DNA by approximately 4 log copies per mil-liliter after 12 weeks.7 Adefovir dipivoxil has also

been efficacious in patients with lamivudine-resist-ant HBV.8

We elected to evaluate in a double-blind, placebo-controlled study the effects of 10-mg and 30-mg doses of adefovir dipivoxil in patients with HBeAg-positive chronic hepatitis B on the basis of the re-sults of phase 2 studies, which showed that the an-tiviral activity of doses greater than or equal to 30 mg was similar. During the long-term, phase 2 study, data indicated that the 30-mg dose was associated with mild, reversible nephrotoxicity after 32 weeks. Therefore, we amended the primary end point for this study before the analysis and unblinding, to compare a 10-mg dose of adefovir dipivoxil with placebo. We report the 48-week results, but the study is ongoing and will continue for up to 5 years. When the study was designed, lamivudine was still an investigational agent; therefore, placebo was se-lected as the control.

s t u d y d e s i g n

From March 1999 to March 2000, patients were re-cruited from 78 centers in North America, Europe, Australia, and Southeast Asia and randomly as-signed in a 1:1:1 ratio to receive 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil per day, 30 mg of adefovir dipivoxil per day, or placebo. The central randomization scheme was stratified according to seven geographic regions. Permuted blocks (with a block size of six) were used in each stratum. The placebo and adefovir dipivoxil tablets were formulated to be indistinguishable from one another in appearance and taste.

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by appropri-ate local regulatory bodies. All patients provided written informed consent. Liver biopsy was per-formed at base line and week 48. Biopsy specimens obtained within six months before randomization could be used if they had been obtained more than six months after the completion of prior hepatitis B therapy. Patients were evaluated every four weeks.

Clinical data were collected, monitored, and en-tered into a data base by Quintiles. Laboratory tests were conducted by Covance. The sponsor held the data and conducted the statistical analyses, which were predefined; the academic investigators had full access to the data and contributed substantially to the design of the study, the collection of the data, the analysis and interpretation of the data, and the draft-ing of the manuscript. All authors approved the fi-nal draft of the manuscript.

p a t i e n t s

Male and female patients 16 to 65 years of age who had hepatitis B e antigen–positive chronic hepati-tis B and compensated liver disease were eligible for the study. Chronic hepatitis B was defined by the presence of serum hepatitis B surface antigen for at least six months, a serum HBV DNA level of at least 1 million copies per milliliter (measured with the Roche Amplicor Monitor polymerase-chain-reac-tion [PCR] assay), and a serum alanine aminotrans-ferase level that was 1.2 to 10 times the upper limit of the normal range. Patients were required to have a prothrombin time that was no more than one sec-ond above the normal range, a serum albumin level of at least 3 g per deciliter, a total bilirubin level of no more than 2.5 mg per deciliter (43 µmol per li-ter), a serum creatinine level of no more than 1.5 mg

The n e w e n g l a n d j o u r n a l of m e d i c i n e

per deciliter (133 µmol per liter), and an adequate blood count. Women of childbearing potential were eligible if they had a negative pregnancy test and were using effective contraception.

Criteria for exclusion included a coexisting seri-ous medical or psychiatric illness; immune globu-lin, interferon, or other immune- or cytokine-based therapies with possible activity against HBV disease within 6 months before screening; organ or bone marrow transplantation; recent treatment with systemic corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, or chemotherapeutic agents; a serum alpha-fetopro-tein level of at least 50 ng per milliliter; evidence of a hepatic mass; liver disease that was not due to hep-atitis B; prior therapy for more than 12 weeks with a nucleoside or nucleotide analogue with activity against HBV; and seropositivity for human immu-nodeficiency virus or hepatitis C or D virus.

e n d p o i n t s

The primary efficacy end point was histologic im-provement, defined as a reduction of at least two points in the Knodell necroinflammatory score with no concurrent worsening of the Knodell fibrosis

score 48 weeks after base line.9 The liver-biopsy

specimens were evaluated by an independent histo-pathologist who was unaware of the patients’ treat-ment assigntreat-ments or of the timing of liver biopsy. Ranked assessments of necroinflammatory activity and fibrosis were also performed (and scored as im-proved, no change, or worse).

Secondary end points included the change from base line in serum HBV DNA levels, the proportion of patients with undetectable levels of HBV DNA, the effect of treatment on the alanine aminotrans-ferase level, and the proportion of patients with loss or seroconversion of HBeAg. Serum HBV DNA lev-els were measured by the Roche Amplicor HBV Monitor PCR assay (lower limit of detection, 400 copies per milliliter), and the values were log-trans-formed with use of a base 10 scale.

s a f e t y a n a l y s i s

The primary safety analysis included all patients who received at least one dose of study medication and all events that occurred during treatment or within 30 days after the discontinuation of study drug. The severity of adverse events and laboratory abnormalities was graded according to the Com-mon Toxicity Criteria of the National Institute of Al-lergy and Infectious Diseases.10

d e t e c t i o n o f h b v p o l y m e r a s e m u t a t i o n s

All serum samples obtained at base line and week 48 were examined in a blinded fashion. HBV DNA was isolated and amplified by PCR. The positive and negative strands of the HBV polymerase gene span-ning the polymerase–reverse-transcriptase domain (amino acids 349 to 692) were sequenced. The HBV sequences of the samples obtained at base line and week 48 from the same patient were aligned with the MegAlign program (DNAStar).

s t a t i s t i c a l a n a l y s i s

The study was designed to enroll 166 patients per group, with 90 percent power to detect an absolute difference of 20 percent (50 percent vs. 30 percent) between the group given 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil and the placebo group, assuming that 25 percent of patients would have missing biopsy specimens that would be considered treatment failures and that 8 percent of patients would have missing base-line biopsy specimens, on the basis of a two-sided type I error rate of 0.05. The study had 79 percent power to detect an absolute difference of 10 percent (16 percent vs. 6 percent) in the rate of seroconversion between the group given 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil and the placebo group, assuming that 10 percent of patients would have missing values (which were counted as treatment failures). Patients who re-ceived at least one dose of study medication were included in the analyses. Patients with missing or unassessable base-line liver-biopsy specimens were prospectively excluded from the primary efficacy analysis. Patients with missing or unassessable data at 48 weeks were considered not to have had re-sponses. The unstratified Cochran–Mantel–Haen-szel test was used to compare each of the adefovir dipivoxil groups with the placebo group. All P val-ues were two-sided. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons. All serum HBV DNA results below the lower limit of detection (less than 400 copies per milliliter) were analyzed as being 400 copies per milliliter. No interim analyses were per-formed other than safety-data summaries, which were prepared every six months for a review by the independent external data-monitoring committee.

c h a r a c t e r i s t i c s o f t h e p a t i e n t s

Among the 515 patients who were enrolled, 172 were randomly assigned to receive 10 mg of

a d e f o v i r d i p i v o x i l f o r c h r o n i c h e p a t i t i s b

ovir dipivoxil per day, 173 to receive 30 mg per day, and 170 to receive placebo. Four patients took no study medication (one in the 10-mg group and three in the placebo group). Of the remaining 511 pa-tients, base-line biopsy specimens were available for 168 patients in the 10-mg group, 165 in the 30-mg group, and 161 in the placebo group. There were no significant differences in demographic or HBV dis-ease characteristics (Table 1) or previous anti-HBV treatments among the groups. A total of 123 pa-tients (24 percent) had received treatment with in-terferon alfa.

h i s t o l o g i c r e s p o n s e

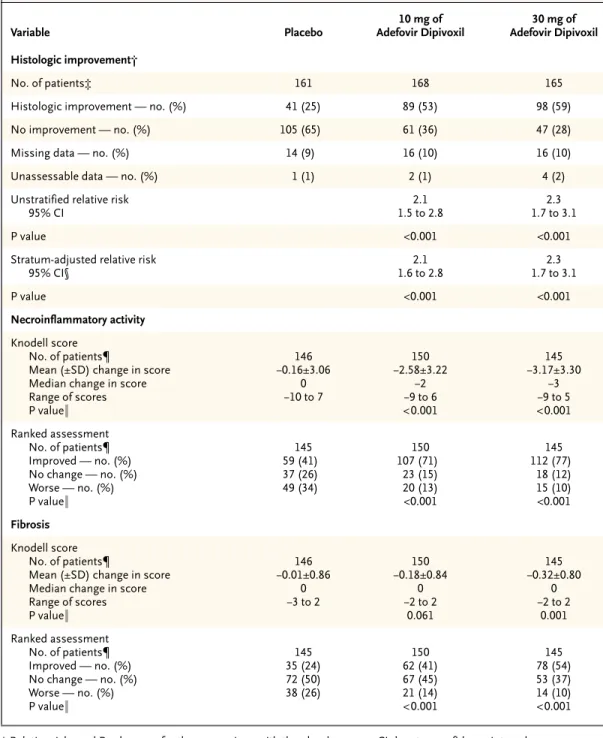

The primary analysis was based on the 329 patients (97 percent) in the group given 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil and the placebo group for whom base-line liver-biopsy specimens were available. Histologic improvement was seen in 53 percent of patients in the group given 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil, 25 per-cent of those in the placebo group (P<0.001) (Ta-ble 2), and 59 percent of those in the group given 30 mg of adefovir dipivoxil (P<0.001). The results were not changed by the addition of the four pa-tients who underwent randomization but who did not take any study medication.

After 48 weeks, patients who received 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil per day had a median reduction in the Knodell necroinflammatory score of two points and those who received 30 mg per day had a median reduction of three points, as compared with no change in the placebo group (P<0.001 for both com-parisons) (Table 2). On ranked assessment, higher percentages of patients in the 10-mg group and the 30-mg group than in the placebo group had im-provements in necroinflammatory activity and fi-brosis, and a higher percentage of patients in the placebo group had worsening of necroinflamma-tory activity and fibrosis (P<0.001 for each com-parison).

v i r o l o g i c r e s p o n s e

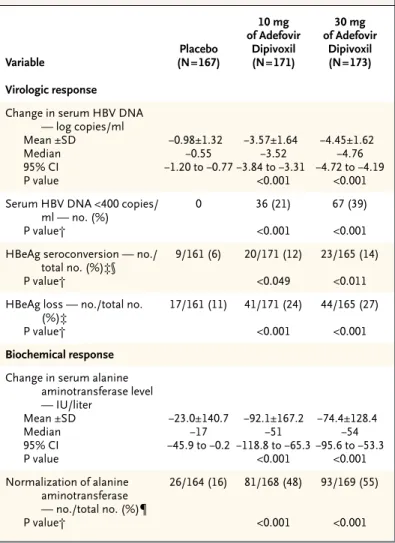

At week 48, serum HBV DNA levels had decreased by a median of 3.52 log copies per milliliter in the group given 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil and 4.76 log copies per milliliter in the 30-mg group, as com-pared with 0.55 log copies per milliliter in the pla-cebo group (P<0.001 for each comparison) (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Twenty-one percent of the patients in the 10-mg group and 39 percent of those in the 30-mg group had undetectable serum levels of HBV DNA, as compared with 0 percent of the patients in the

placebo group (P<0.001 for each comparison). Loss of HBeAg occurred in 24 percent of the patients in the 10-mg group and 27 percent of those in the 30-mg group, as compared with 11 percent of the patients in the placebo group (P<0.001 for each comparison). HBeAg seroconversion occurred in 12 percent of the patients in the 10-mg group and 14 percent of those in the 30-mg group, as compared

* ULN denotes upper limit of the normal range, and HBV hepatitis B virus. † Values were log-transformed with use of a base 10 scale.

Table 1. Base-Line Characteristics of the Patients.*

Characteristic Placebo (N=167) 10 mg of Adefovir Dipivoxil (N=171) 30 mg of Adefovir Dipivoxil (N=173) Age — yr Mean ±SD Median Range 37±11.8 35 16–66 34±11.2 32 16–65 34±10.8 32 17–68

Male sex — no. (%) 119 (71) 130 (76) 129 (75)

Race or ethnic group — no. (%) White Black Asian Other 60 (36) 3 (2) 101 (60) 3 (2) 60 (35) 8 (5) 102 (60) 1 (1) 64 (37) 5 (3) 101 (58) 3 (2) Weight — kg Mean ±SD Median Range 70±14.9 70 41–134 72±15.9 71 43–118 69±15.9 67 40–129 Alanine aminotransferase Mean ±SD — U/liter Median — U/liter ≤ULN — no. (%) >ULN — no. (%) Multiples of ULN Mean ±SD Median 139±131 94 3 (2) 164 (98) 3.4±3.1 2.4 139±154 95 3 (2) 168 (98) 3.4±4.0 2.3 124±96 92 4 (2) 169 (98) 3.0±2.3 2.3 HBV DNA — log copies/ml†

Mean ±SD Median 8.12±0.89 8.33 8.25±0.90 8.40 8.22±0.84 8.34 Total Knodell score

Mean ±SD Median Range 9.65±3.45 10.0 1–17 9.01±3.33 9.5 0–17 9.55±3.33 10.0 0–16 Knodell necroinflammatory score

Mean ±SD Median Range 7.83±2.89 8.0 1–14 7.37±2.75 7.0 0–14 7.84±2.82 8.0 0–12 Knodell fibrosis score

Mean ±SD Median Range 1.83±1.12 1.0 0–4 1.64±1.09 1.0 0–4 1.71±1.06 1.0 0–4

The n e w e n g l a n d j o u r n a l of m e d i c i n e

* Relative risks and P values are for the comparison with the placebo group. CI denotes confidence interval.

† Histologic improvement was defined as a decrease of at least two points in the Knodell necroinflammatory score from base line to week 48, with no concurrent worsening of the Knodell fibrosis score. Patients who did not satisfy this defini-tion were considered not to have histologic improvement. Patients with missing or unassessable data at week 48 were considered not to have had histologic improvement in the comparison between each adefovir dipivoxil group and the placebo group.

‡ The number of patients is the number with assessable liver-biopsy specimens at base line.

§ Values were adjusted for the seven geographic regions involved in the study (Europe, the United States, Canada, Australia, Taiwan, Thailand, and other parts of Asia [Singapore, the Philippines, and Malaysia]).

¶ The number of patients is the number with assessable liver-biopsy specimens at base line and week 48.

¿ P values are from the general-association Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel statistic for comparisons of the 10-mg group or the 30-mg group with the placebo group. All P values are two-sided at a significance level of 0.05, with no adjustments for multiple comparisons.

Table 2. Histologic Improvement and Changes in Necroinflammatory Activity and Fibrosis from Base Line to Week 48.*

Variable Placebo 10 mg of Adefovir Dipivoxil 30 mg of Adefovir Dipivoxil Histologic improvement† No. of patients‡ 161 168 165

Histologic improvement — no. (%) 41 (25) 89 (53) 98 (59)

No improvement — no. (%) 105 (65) 61 (36) 47 (28)

Missing data — no. (%) 14 (9) 16 (10) 16 (10)

Unassessable data — no. (%) 1 (1) 2 (1) 4 (2)

Unstratified relative risk 95% CI 2.1 1.5 to 2.8 2.3 1.7 to 3.1 P value <0.001 <0.001

Stratum-adjusted relative risk 95% CI§ 2.1 1.6 to 2.8 2.3 1.7 to 3.1 P value <0.001 <0.001 Necroinflammatory activity Knodell score No. of patients¶

Mean (±SD) change in score Median change in score Range of scores P value¿ 146 ¡0.16±3.06 0 ¡10 to 7 150 ¡2.58±3.22 ¡2 ¡9 to 6 <0.001 145 ¡3.17±3.30 ¡3 ¡9 to 5 <0.001 Ranked assessment No. of patients¶ Improved — no. (%) No change — no. (%) Worse — no. (%) P value¿ 145 59 (41) 37 (26) 49 (34) 150 107 (71) 23 (15) 20 (13) <0.001 145 112 (77) 18 (12) 15 (10) <0.001 Fibrosis Knodell score No. of patients¶

Mean (±SD) change in score Median change in score Range of scores P value¿ 146 ¡0.01±0.86 0 ¡3 to 2 150 ¡0.18±0.84 0 ¡2 to 2 0.061 145 ¡0.32±0.80 0 ¡2 to 2 0.001 Ranked assessment No. of patients¶ Improved — no. (%) No change — no. (%) Worse — no. (%) P value¿ 145 35 (24) 72 (50) 38 (26) 150 62 (41) 67 (45) 21 (14) <0.001 145 78 (54) 53 (37) 14 (10) <0.001

a d e f o v i r d i p i v o x i l f o r c h r o n i c h e p a t i t i s b

with 6 percent of the patients in the placebo group (P=0.049 and P=0.011, respectively).

b i o c h e m i c a l r e s p o n s e

Median reductions in serum alanine aminotransfer-ase levels at week 48 were 51 IU per liter in the 10-mg group and 54 IU per liter in the 30-10-mg group, as compared with 17 IU per liter in the placebo group (P<0.001 for each comparison) (Table 3). Forty-eight percent of the patients who received 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil per day and 55 percent of those who received 30 mg per day had normal alanine aminotransferase values at week 48, as compared with 16 percent of those who received placebo (P< 0.001 for both comparisons).

r e s i s t a n c e p r o f i l e

The polymerase–reverse transcriptase domain of the HBV polymerase gene was sequenced from se-rum samples obtained at base line and week 48 in 381 patients with detectable serum HBV DNA at both times. No mutations occurred at higher than background frequencies (less than 1.6 percent). Seven different novel substitutions were found at conserved sites in the HBV polymerase in seven pa-tients (four of whom received adefovir dipivoxil and three of whom received placebo). All four of the pa-tients who received adefovir dipivoxil had signifi-cant reductions in serum HBV DNA levels at week 48. In vitro phenotypic analyses demonstrated that viruses containing any of the seven substitutions re-mained fully susceptible to adefovir.

s a f e t y

Similar percentages of patients in each group dis-continued the study prematurely: 7 percent of those given 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil per day and 8 per-cent of those given 30 mg per day and those given placebo. The incidence of severe (grade 3 or 4) clin-ical adverse events was similar: 10 percent in pa-tients who received 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil per day, 9 percent in those who received 30 mg per day, and 8 percent in the placebo group. The safety pro-file of the 10-mg group was similar to that of place-bo with respect to all reported adverse events except asthenia (25 percent in the 10-mg group vs. 19 per-cent in the placebo group) and diarrhea (13 perper-cent vs. 8 percent) (Table 4). Anorexia (10 percent) and pharyngitis (40 percent) occurred more frequently in the 30-mg group. Adverse events leading to the discontinuation of the study drug occurred in 2 per-cent of the patients in the 10-mg group, 3 perper-cent of

those in the 30-mg group, and less than 1 percent of those in the placebo group. These events included increased alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase levels, weight loss, and rash in the 10-mg group; nausea, abdominal pain, headache, Fanconi-like syndrome, amblyopia, and myocardial infarction in the 30-mg group; and nausea in the placebo group.

There was no significant change in median se-rum creatinine levels at week 48 in the 10-mg group

* HBV denotes hepatitis B virus, and CI confidence interval.

† P values are from the general-association Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel statistic for comparisons of each adefovir dipivoxil group with the placebo group. All P values are two-sided at a significance level of 0.05, with no adjustments for multiple comparisons.

‡ Patients who were positive for hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) at base line were included in the analysis.

§ Seroconversion was defined as loss of HBeAg and concurrent gain of antibody against HBeAg at 48 weeks.

¶ Patients with base-line alanine aminotransferase levels that exceeded the up-per limit of the normal range were included in the analysis.

Table 3. Virologic and Biochemical Responses at Week 48.*

Variable Placebo (N=167) 10 mg of Adefovir Dipivoxil (N=171) 30 mg of Adefovir Dipivoxil (N=173) Virologic response

Change in serum HBV DNA — log copies/ml Mean ±SD Median 95% CI P value ¡0.98±1.32 ¡0.55 ¡1.20 to ¡0.77 ¡3.57±1.64 ¡3.52 ¡3.84 to ¡3.31 <0.001 ¡4.45±1.62 ¡4.76 ¡4.72 to ¡4.19 <0.001 Serum HBV DNA <400 copies/

ml — no. (%) P value† 0 36 (21) <0.001 67 (39) <0.001 HBeAg seroconversion — no./

total no. (%)‡§ P value† 9/161 (6) 20/171 (12) <0.049 23/165 (14) <0.011 HBeAg loss — no./total no.

(%)‡ P value† 17/161 (11) 41/171 (24) <0.001 44/165 (27) <0.001 Biochemical response

Change in serum alanine aminotransferase level — IU/liter Mean ±SD Median 95% CI P value ¡23.0±140.7 ¡17 ¡45.9 to ¡0.2 ¡92.1±167.2 ¡51 ¡118.8 to ¡65.3 <0.001 ¡74.4±128.4 ¡54 ¡95.6 to ¡53.3 <0.001 Normalization of alanine aminotransferase — no./total no. (%)¶ P value† 26/164 (16) 81/168 (48) <0.001 93/169 (55) <0.001

The n e w e n g l a n d j o u r n a l of m e d i c i n e

and the placebo group; the 30-mg group had a me-dian increase of 0.2 mg per deciliter (18 µmol per li-ter). There were no increases from base line of 0.5 mg per deciliter (44 µmol per liter) or greater in the serum creatinine level (confirmed by two consecu-tive laboratory assessments) in the 10-mg group or the placebo group, but 8 percent of patients in the 30-mg group had such an increase (P<0.001). In all cases, renal function normalized with a dose reduc-tion or an interrupreduc-tion of treatment. The maximal reported serum creatinine level was 1.8 mg per deci-liter (159 µmol per deci-liter) in a patient in the 30-mg group. There was a median increase in serum phos-phorus of 0.1 mg per deciliter (0.03 mmol per liter) in the 10-mg group and the placebo group and a me-dian decrease of 0.1 mg per deciliter in the 30-mg group. There were no confirmed instances of serum phosphorus levels below 2.0 mg per deciliter (0.65 mmol per liter). The incidence of grade 3 or 4 lab-oratory abnormalities was similar in the adefovir dipivoxil and placebo groups, except that aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase lev-els were higher in the placebo group.

Increases in alanine aminotransferase levels to more than 10 times the upper limit of the normal range occurred in 10 percent of patients in the group given 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil per day, 8 percent of those given 30 mg per day, and 19 percent of those given placebo. Concurrent changes in total bilirubin levels, serum albumin levels, or the prothrombin time were not seen in any patient in the 10-mg or 30-mg group. In the placebo group, one patient had a concurrent increase in the total bilirubin level to greater than 2.5 mg per deciliter and to at least 1 mg per deciliter (17.1 µmol per liter) above the base-line value, and one had a concurrent decrease in the se-rum albumin level (to less than 3.0 g per liter).

After week 48, all patients were reassigned to new treatment groups for the second 48 weeks of the study. All patients in the placebo group received 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil per day. Patients in the 10-mg group were randomly assigned to receive ei-ther continued treatment with 10 mg per day or placebo. All patients in the 30-mg group received placebo.

An interim analysis of data from the second 48-week period showed a continued antiviral, serolog-ic, and biochemical response in patients who con-tinued to receive 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil per day (median duration of additional therapy, 16 weeks). By week 72, 46 percent of patients had fewer than 400 copies of serum HBV DNA per milliliter, 75 per-Figure 1. Mean Change from Base Line in Serum Levels of Hepatitis B Virus

(HBV) DNA.

I bars are 95 percent confidence intervals. P values are for the comparison with placebo. No. of Patients Placebo 10 mg 30 mg 167 171 173 164 164 169 162 170 168 162 168 164 158 164 161 158 164 161 156 160 159 156 165 162 153 156 161 153 150 156 152 157 161 150 157 157 148 152 146

Change in HBV DNA (log copies/ml)

Week of Study 1 0 ¡1 ¡2 ¡3 ¡4 ¡5 ¡6 Base line 4 8 12 16 20 24 28 32 36 40 44 48 Placebo P<0.001 P<0.001 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil 30 mg of adefovir dipivoxil

Table 4. Adverse Events Reported by at Least 10 Percent of Patients in the Group Given 30 mg of Adefovir Dipivoxil per Day.

Adverse Event Placebo (N=167) 10 mg of Adefovir Dipivoxil (N=171) 30 mg of Adefovir Dipivoxil (N=173) number of patients (percent)

Body as a whole Headache Asthenia Abdominal pain Flu-like syndrome Pain Back pain 37 (22) 32 (19) 32 (19) 31 (19) 21 (13) 11 (7) 43 (25) 42 (25) 31 (18) 28 (16) 19 (11) 11 (6) 45 (26) 45 (26) 38 (22) 32 (18) 13 (8) 17 (10) Digestive tract Nausea Diarrhea Dyspepsia Flatulence Anorexia 23 (14) 13 (8) 14 (8) 10 (6) 9 (5) 17 (10) 23 (13) 15 (9) 13 (8) 6 (4) 31 (18) 25 (14) 19 (11) 18 (10) 18 (10) Nervous system Dizziness 13 (8) 9 (5) 18 (10) Respiratory tract Pharyngitis Increased cough 54 (32) 21 (13) 44 (26) 11 (6) 70 (40) 19 (11)

a d e f o v i r d i p i v o x i l f o r c h r o n i c h e p a t i t i s b

cent had normalization of alanine aminotransfer-ase levels, 44 percent had loss of HBeAg, and 23 per-cent had HBeAg seroconversion. Safety data from the second 48-week period were similar to those in the first 48 weeks.

In patients with chronic hepatitis B, 48 weeks of treatment with adefovir dipivoxil resulted in signif-icant histologic improvement, reduced serum HBV DNA levels, and increased normalization of alanine aminotransferase levels and HBeAg seroconversion, as compared with placebo. These results are similar to those in the 52-week pivotal clinical trials of la-mivudine.3,4 Lai et al. reported significant

histolog-ic improvement in 56 percent of patients after one year of treatment with lamivudine, although the development of serum HBV DNA polymerase mu-tations was associated with increases in alanine

aminotransferase and HBV DNA.3 Dienstag et al.

reported histologic improvement in 52 percent of patients who received 100 mg of lamivudine per day; anti-HBeAg antibodies developed in 17 percent, and

32 percent lost serum HBeAg.4

The patients in this study were from North Amer-ica, Europe, Australia, and Southeast Asia; the ma-jority were Asian. The two pivotal trials of lamivu-dine included predominantly white patients in the United States4 or only Chinese patients.3 Several

studies have found regional and ethnic differences in response to both HBV infection and treatments for hepatitis B.11 The histologic improvement in our

patients was similar among the geographic regions; therefore, our results may be more representative of the global population of patients with chronic hepatitis B. However, black patients were not well represented.

The efficacy profile of the 10-mg and 30-mg doses of adefovir dipivoxil was similar, except for differences in the magnitude of the decrease in se-rum HBV DNA levels and the percentage of patients with undetectable serum HBV DNA levels at 48 weeks. Both doses were well tolerated. However, the increases in serum creatinine levels in the 30-mg group limit the long-term use of this dose and in-stead favor the 10-mg dose. No adefovir-associat-ed resistance mutations were identifiadefovir-associat-ed during 48 weeks of treatment, which is consistent with find-ings from other studies evaluating up to 60 weeks of treatment.12,13

In our study, treatment with 10 mg of adefovir dipivoxil daily was well tolerated and significantly improved histologic findings in the liver, reduced serum HBV DNA levels, normalized alanine amino-transferase levels, and induced HBeAg loss and ser-oconversion in a diverse population. The favorable resistance profile of adefovir dipivoxil during 48 weeks of therapy is an advantage, since many pa-tients with chronic hepatitis B require long-term therapy.

Supported by Gilead Sciences.

Drs. Wulfsohn, Xiong, and Brosgart and Mr. Fry are employees of Gilead Sciences and report equity ownership in Gilead Sciences. Drs. Marcellin, Tong, and Goodman report having served as con-sultants to Gilead Sciences. Dr. Marcellin reports having served as a paid lecturer for Gilead Sciences.

d i s c u s s i o n

a p p e n d i x

In addition to the authors, the Adefovir Dipivoxil International Investigator 437 Study Group includes the following: N. Afdhal and C. O’Conner (Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston); P. Andreone and C. Cursaro (Policlinico S. Orsola, Bologna, Italy); P. Angus and R. Vaughan (Austin and Repatriation Medical Centre, Melbourne, Australia); V. Bain and K. Gutfreund (University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alta., Canada); K. Barange and M. Duffant (Hôpital Purpan, Toulouse, France); E. Barnes (Royal Free Hospital, London); M. Bennett and J. Pressman (Medical Association Research Group, San Diego, Calif.); D. Bernstein (North Shore University Hospital, Manhasset, N.Y.); F. Bonino and B. Coco (Azienda Ospedaliera Pisana, Pisa, Italy); M. Borum and S. Schuck (George Washington University Medical Center, Washington, D.C.); M. Bourliere and S. Benali (Hôpital Saint Joseph, Marseilles, France); N. Boyer and C. Castelnau (Hôpital Beaujon, Cli-chy, France); R. Brown and S. Scales (Columbia–Presbyterian Medical Center, New York); P. Buggisch and J. Peterson (Universitätskranken-haus Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany); G. Cooksley and G. MacDonald (Royal Brisbane Hospital, Brisbane, Australia); P. Couzigou and D. Foucner (Hôpital Haut-Leveque, Pessac, France); D. Crawford (Princess Alexandra Hospital, Brisbane, Australia); A. Der (Monash Medical Center, Melbourne, Australia); P. Desmond and A. Boussioutas (St. Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne, Australia); A. DiBisceglie and B. Bacon (Saint Louis University Medical Center, St. Louis); D. Dieterich and D. Goldman (Liberty Medical Group and New York University School of Medicine, New York); G. Dusheiko and the Royal Free Viral Hepatitis Group (Royal Free Hospital, London); J. Enriquez and A. Gallego (Hospital Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Barcelona, Spain); S. Esposito and J. Lemieszewski (Hepatobiliary Associates of New York, Bayside); R. Es-teban and M. Buti (Hospital Vall d’Hebron, Barcelona, Spain); T. Faust and K. Wherity (University of Chicago Hospital Medical Center, Chi-cago); A. Francavilla and F. Malcangi (Azienda Ospedaliera Consorziale Policlinico, Bari, Italy); M. Fried and C. Nakayama (University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill); R. Gilson and M. Lascar (University College of London Medical Centre, London); R. Gish and H. Trinh (California Pacific Medical Center, San Francisco); S. Gordon and S. Colar (William Beaumont Hospital, Royal Oak, Mich.); M. Gregor and S. Kaiser (Eberhard-Karl-Universität, Tübingen, Germany); J. Heathcote (Toronto Western Hospital, Toronto); D. Imagawa (University of California, Irvine, Orange); I. Jacobson (Cornell University School of Medicine, New York); J. Rooney, C. James, R. Fallis, A. Jain, S. Chen, J. Ma, A. Hsing, S. Nonaka-Wong, and M. Kraus (Gilead Sciences, Foster City, Calif.); C.-M. Jen (National Cheng Kung Uni-versity Hospital, Tainan, Taiwan); K. Kaita (UniUni-versity of Manitoba Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg, Man., Canada); G. Koval and H.

Par-a d e f o v i r d i p i v o x i l f o r c h r o n i c h e p Par-a t i t i s b

rish (West Hills Gastroenterology Associates, Portland, Oreg.); K. Kowdley (University of Washington Hepatology Center, Seattle); I. Kron-borg and A. Nicoll (Western Hospital, Melbourne, Australia); P. Kullavanijaya and J. Amonrattanakosol (Chulalongkorn University Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand); J. Lao-Tan and L. Garcia (Cebu Doctors Hospital, Cebu City, Philippines); Y.-F. Liaw and R.-N. Chien (Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan); A. Lok and P. Richtmyer (University of Michigan Medical Center, Ann Arbor); P. Luengrojanakul and T. Tanwandee (Siriraj Hospital, Bangkok, Thailand); M. Manns and A. Schueler (Medizinische Hochschule Hannover, Hannover, Ger-many); P. Martin and V. Peacock (UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles); G. McCaughan and S. Strasser (Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia); J. McHutchison and P. Pockros (Scripps Clinic, La Jolla, Calif.); I. Merican and S. Lachmanan (Hospital Kuala Lumpur, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia); R. Mohamed (University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia); R. Naccarato and S. Fagiuoli (Azienda Ospedaliera di Pa-dova, Padua, Italy); M. Nelson and C. Higgs (Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London); G. Pastore (Azienda Ospedaliera Consorziale, Bari, Italy); R. Perrillo and C. Denham (Alton Ochsner Medical Clinic, New Orleans); S. Pol and H. Fontaine (Hôpital Necker, Paris); C. Riely and D. Litley (University of Tennessee Medical Group, Memphis); M. Rizzetto and M. Lagget (Azienda Ospedaliera San Giovanni Battista, Turin, Italy); M. Rodriguez and M. Espiga (Hospital Central de Asturias, Oviedo, Spain); V. Rustgi and P. Lee (Metro Clinical Trials, Fairfax, Va.); S. Sacks and J. Farley (Viridae Clinical Sciences, Vancouver, B.C., Canada); D. Samuel and C. Feray (Hôpital Paul Brousse, Villejuif, France); J. Sasadeusz and M. Gioupouki (Royal Melbourne Hospital, Melbourne, Australia); D. Shaw and M. Le Mire (Royal Adelaide Hos-pital, Adelaide, Australia); D. Shelton (Hunter Holmes McGuire Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Richmond, Va.); M. Sherman and A. Bar-tolucci (Toronto General Hospital, Toronto); E. Schiff and A. Siebert (University of Miami, Miami); J. Sollano and F. Dy (Santo Tomas Uni-versity Hospital, Manila, Philippines); P. Thuluvath (Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore); L. Tong (Huntington Medical Research Institutes, Pasadena, Calif.); C. Trepo and M. Maynard (Hôtel Dieu, Lyons, France); J.-C. Trinchet and N. Carrie (Hôpital Jean Verdier, Bondy, France); D. Vetter and S. Metzger (Hôpital Civil de Strasbourg, Strasbourg, France); J. Vierling and J. Clarke-Platt (Cedars–Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles); E. Wakil and N. Bzowej (Sutter Institute for Medical Research, Sacramento, Calif.); T. Warnes (Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester, United Kingdom); T. Wright and A. Kwong (San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center, San Francisco); Y.-Y. Young (Na-tional University Hospital, Singapore); and J.-P. Zarski and V. Leroy (Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Grenoble–Hôpital Albert Michal-lon, Grenoble, France).

r e f e r e n c e s

1. Hepatitis B. Fact sheet WHO/204. Geneva: World Health Organization, Octo-ber 2000. (Accessed January 7, 2003, at http: //www.who.int/inf-fs/en/fact204.htm.)

2. Intron A. Kenilworth, N.J.: Schering, 2001 (package insert).

3. Lai C-L, Chien R-N, Leung NWY, et al. A one-year trial of lamivudine for chronic hepatitis B. N Engl J Med 1998;339:61-8.

4. Dienstag JL, Schiff ER, Wright TL, et al. Lamivudine as initial treatment for chronic hepatitis B in the United States. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1256-63.

5. Leung NW, Lai C-L, Guan R, Liaw Y-F. The effect of longer duration of harbouring lamivudine-resistant hepatitis B virus (YMDD mutants) on liver histology during 3 years lamivudine therapy in Chinese patients. Hep-atology 2001;34:348A. abstract.

6. Kim JW, Lee HS, Woo GH, et al. Fatal submassive hepatic necrosis associated

with tyrosine-methionine-aspartate-aspar-tate-motif mutation of hepatitis B virus after long-term lamivudine therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2001;33:403-5.

7. Heathcote EJ, Jeffers L, Wright T, et al. Loss of serum HBV DNA and HBeAg and seroconversion following short-term (12 weeks) adefovir dipivoxil therapy in chronic hepatitis B: two placebo-controlled phase II studies. Hepatology 1998;28:Suppl:317A. abstract.

8. Schiff ER, Neuhaus P, Tillman H, et al. Safety and efficacy of adefovir dipivoxil for the treatment of lamivudine resistant HBV in patients post liver transplantation. Hepa-tology 2001;34:446A. abstract.

9. Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, et al. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hep-atitis. Hepatology 1981;1:431-5.

10.Common toxicity criteria, version 2. Bethesda, Md.: National Cancer Institute, 1999. (Accessed February 4, 2003, at http:// ctep.info.nih.gov.)

11.Chien R-N, Liaw Y-F, Atkins M. Prether-apy alanine transaminase level as a determi-nant of hepatitis B e antigen seroconversion during lamivudine therapy in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology 1999;30: 770-4.

12.Yang H, Westland CE, Delaney WE IV, et al. Resistance surveillance in chronic hepa-titis B patients treated with adefovir dipiv-oxil for up to 60 weeks. Hepatology 2002; 36:464-73.

13.Benhamou Y, Bochet M, Thibault V, et al. Safety and efficacy of adefovir dipivoxil in patients co-infected with HIV-1 and lamivu-dine-resistant hepatitis B virus: an open-label pilot study. Lancet 2001;358:718-23.

New England Journal of Medicine

CORRECTION

Adefovir Dipivoxil for the Treatment of Hepatitis B e Antigen–Negative Chronic Hepatitis B

Adefovir Dipivoxil for the Treatment of Hepatitis B e Antigen–Positive Chronic Hepatitis B

Adefovir Dipivoxil for the Treatment of Hepatitis B e Antigen–Negative Chronic Hepatitis B and Adefovir Dipivoxil for the Treatment of Hepati-tis B e Antigen–Positive Chronic HepatiHepati-tis B . On page 801, in line 10 of the right-hand column, and on page 809, in the first line of the second paragraph, the trade name for adefovir dipivoxil should be ``Hepsera´´ rather than ``Preveon.´´ We regret the error. The Web versions of the articles have been corrected.