Chapter Three Directionality in SI

This chapter reviews the previous discussions/debates concerning

directionality as background knowledge to begin with. This study then questions whether working into A is a standard by identifying some of the factors that may have affected interpreting process across language direction.

3.1 Directionality: Is There an Issue?

The task of interpreting always proceeds from one direction to another (From a source language to a target language) and as Bartlomiejczyk (2004b) indicates, whether to simultaneously interpret into one’s A or B language has been a

controversial subject over the years. Before approaching the issue of directionality, one must first ask: is there a difference between working into A and working into B?

3.1.1 Arguments for Interpreting into A

This section presents the views supporting the direction of B-A. There are two major claims for working into A, most oft-cited consideration is B-A renders a better quality of language production. Also, some believe that B comprehension is easier to achieve than B production.

3.1.1.1 Quality Language Production

The first and foremost argument found supporting B-A by is the concern for quality language production. Since the very beginning of interpreting research, most authors were convinced by the superiority of B-A combination (Bartlomiejczyk 2004b). For example, Herber (1953, cited in Bartlomiejczyk 2004b) believed that

strictly applied in simultaneous and consecutive interpreting. In addition, Seleskovitch (1978) claimed that working into B produces inevitably flawed speech and the

interpreter’s native language had an influence on the foreign language production.

With today’s ample opportunities to travel abroad and massive foreign media coverage, the claim that working from one’s A has the advantage of better input comprehension which helps rendering a higher interpreting accuracy cannot effectively convince EMCI (2002) although EMCI does acknowledge interpreting into B on the basis of the concern for market reality. Seleskovitch and Lederer (1998, cited in Szabari 2002) believe B-A generates the best result of a familiar interpretation to the listener or user who does not need to reformulate or reinterpret what is being heard.

Seleskovitch and Lederer further suggest that the ma in problem of A-B is that the mother tongue has an effect on the B language output in which the interpreter strives to “convey it in all of its dressing”, and such interpretation is likely to contain alien tools exist in the source language, making it more difficult for the listener to understand (p. 15). Working into B is also a more energy-consuming direction for interpreters, which leads to more rapid performance deterioration, again according to Seleskovitch and Lederer. In fact, some mention the claim that working into the non- dominant language places an “extra cognitive burden” on the interpreter, leading to

“loss of quality.” (Szabari 2002; Chang 2005, p.15) The drawback of “extra cognitive burden” when working into B may be supported by Kurz (1992, cited in Bartlomiejczyk 2004b), who measured the brain activity (EEG) of an interpreter who only worked mentally without actually uttering the output in both directions.

Interestingly, it was discovered that more brain areas were involved as the interpreter worked from A to B than from B to A. Kurz’s discovery may explain why interpreters

in Donovan’s user survey all show a preference of working into their mother tongue as they feel “it is less tiring, one is less tense and has more flexibility.” (Donovan 2002, p. 7)

The unnatural B language production is also suggested by Campbell (1998, cited in Szabari 2002). Gaiba (1998) mentions that those who do not support working into B suggest that this direction often has the problem of delivery; for instance, the foreign accent perceived in the interpreter’s B production. In fact, it is a commonly held opinion that when interpreting into B, the production is more likely to be problematic under stress (Dornic 1978; Selinker 1972 and Dewaele 2002 cited in Chang 2005). The general assumption based on the argument as reviewed is that when one interprets into A, what he/she also offers is a more fluent and natural production comparing to production in B. In other words, it seems that one is less likely

challenged in the A production with all else being equal, which lead to the next argument in 3.1.1.2.

3.1.1.2 B Production vs. B Comprehension

Another familiar argument for working into A is that accurate comprehension in B can be achieved with a greater likelihood than accurate production in B. This means that B receptive skills are higher than B productive skills, thus it is

“advantageous to have B-language text as the source text to be understood”, while having to produce messages in A (Gerver 1976, cited in Tommola & Helevä 1998, p.178). Others further suggest that it is not only the syntactic structure but also the prosodic features of B that necessarily draws away an interpreter’s attention while interpreting in the direction of A-B (Schweda-Nicholson 1992, cited in Chang 2005).

Alfred Steer also believes that “a refined and elegant delivery” is harder to achieve with B production (Gaiba 1998. p. 48).

To sum up, two general ideas support working into A. First, the linguistic quality of delivery when working into A is much more dependable thus the language production is relatively more natural and familiar to the listener who shares the interpreter’s mother tongue. The additional argument is that accurate B

comprehension is easier to achieve than accurate production in B.

3.1.2 Arguments for Interpreting into B

This section discusses various views and facts supporting the direction of A-B.

This study identifies three major supporting arguments for A-B in the literature review. They are related to market demand, the advantage of native understanding of input and content accuracy as interpreting priority

3.1.2.1 Market Reality

Market reality may be one of the most important arguments for accepting AB retour because it is the most oft-cited concern according to this study’s literature review. In the past, the exponent and translation of Buddhist scripture in China as well as how the Spanish trained the Natives to be the interpreters as mentioned (See 2.1.2) are both good examples for the necessity of working into a foreign language in order to accommodate market in the past.

Today, interpreting into B is known as retour interpreting. “Retour interpreting is particularly useful to provide relays out of less well-known languages into more

wide spread languages.” (SCIC website) Working between A and B (Or interpreting in both directions) is also called AB retour (AIIC website). The reality requires AB retour is based on the fact that as more and more countries establish channels to communicate for various purposes, it is difficult to find interpreters who speak a less well-known language as his/her B or C. Therefore, “A-B combinations are an absolute necessity for some languages”, such as those of the many EU new members (Bartlomiejczyk 2004b, p. 247). It is sometimes “a practical necessity” (EMCI 2002;

Tommola & Helevä 1998) because there may not always be enough interpreters who are the native speakers of a certain language; therefore, those who know the language as a second language may be required to work in both directions. For example, in Taiwan, a shortage of English-native interpreters is a fact so usually a Taiwanese interpreter (Whose A is Chinese and B is English) must work both ways (Chang 2005). A similar problem also exists in other Asian countries such as in Korea since it is difficult to find interpreters whose B or C is Korean while their A is a more well- known language (Lee 2002).

Not only in Asia but in fact as Szabari (2002) points out, a similar need for retour interpreting exists in Europe today. Minns (2002) contributes such reality to

“the accession of new member countries to the EU as well as the overall phenomenon of globalization.” (p. 35) Thus for practical reasons, retour interpreting is now also adopted by some international organizations and private market contracts (EMIC 2002; Donovan 2002). Practicing and teaching techniques of working into B have been receiving increasing attention and discussion than ever. For example, EMCI accepts retour interpreting as a fact and has been in the discussion on issues relating to associated training requirements (Donovan 2004). AIIC also recognizes that the

European Commissions accepts interpreti ng into B provided that the language that is worked into is English, Frenc h or German now also known as retour languages (AIIC website). Apparently, a strict application of working into A is not an option since it is difficult to find native speakers whose A is, for example, one of the retour languages and at the same time also have a less sought-after language as an additional B. The truth is, market demands AB retour is no longer news. AIIC recognizes the need for AB retour. It mentions that Chinese is becoming more important while Japanese is also much in demand but few interpreters can speak either language as an active language except for interpreters who have the language as their mother tongue (AIIC website). Strictly working into A is practically difficult, if not totally impossible, in virtually many parts of the world.

3.1.2.2 Native Understanding

The most difficult part in B-A SI is input/source text comprehension (Weller 1991, cited in Lee 1999; Chang 2005). In addition, Seleskovitch (1978, cited in Lee 1999) believes that the greatest difficulty in SI is that the interpreter is not allowed to work at his/her own speed. In terms of time pressure, Gile (1995) also indicates that SI is however different from “translation work, in which at least some time is generally available for research and consultation of native speakers in case some words or structure are not understood… ” (p. 84); it is a view that is also shared by other scholars such as Hamers & Blanc (1989). Good listening comprehension is important in SI partially because SI is a completely different sociolinguistic setting from reading given that a reader can “pause or go back for further understanding”

(Lee 1999, p. 261) which is simply impossible to do in SI. The way SI is carried out does not allow as much time (As written translation) to think and work, as Gile further

comments, “a translator has the advantage to have the chance to select a text to be worked on but the same advantage does not apply to an interpreter so comprehension of the source language must be very good even though it is not fully put to use.”

(p. 84) In addition, Gile (1995) cautions that working form B into A’s problem is “an uncertainty factor: speeches may be quite easy most of the time but professional ethics require that the interpreter be able to handle difficulties when they do arise.” (p. 84) This piece of comment supports the advantage of native understanding which almost functions as “insurance” for listening comprehension although “accidents” may or may not happen despite whether the interpreter has such insurance when interpreting.

Another advantage of working into B is a better understanding of the source text, which in fact is a crucial stage in interpreting (Szabari 2002; Denissenko 1989, cited in Chang 2005). Studies show that at least 80% of the cognitive effort is put to work at the listening and understanding of a speech during interpreting and only 20%

at the stage of production (Padilla 1995, cited in Rejšková 2002). Szabari (2002) added the fact that Russian interpreters in the days of the Soviet Union also favored working from their mother tongue because of better comprehension in the source language as an additional example supporting this direction. This study considers the advantage of native understanding when working from A as a strongest argument at the cognitive level not only because it is an oft-cited point of view but it is compelled by the fact that comprehension is the first and foremost concern in interpreting

(Seleskovitch 1978, cited in Rejšková 2002). What we have seen here is how the nature of SI works closely with native listening to generate an argument for working into B. Given that SI is an immediate translating mode which does not allow the interpreter to pause for input clarification, the processing advantage of native listening

seems to stand out more than nonnative listening. Comprehension in SI, as crucial and yet difficult as it is, may be best overcome if interpreting is from A to B where native understanding is put to work, as all other things being equal. Based on the word translation task carried out, Kees de Bot (2000) believes that although more time is needed to retrieve the right word from the dominant into the weaker language, “the advantage of a better and deeper understanding of the incoming message more than compensates for this.” (p. 85)

3.1.2.3 Content Accuracy

An additional argument supporting working into B is that content accuracy of an interpretation is more important than style of language production and the possible linguistic flaws in B production should not be used to challenge such priority, as this study sums up for the following studies.

As far as users are concerned, content accuracy is what users expect from an interpreter who should be able to convey the speaker’s message instead of a word-for- word translation of what the speaker said (Donovan 2002). Donovan’s study presents a survey conducted in Paris at around some 30 events at which interpreters worked into English and French, users, in this case delegates, did not perceive directionality, accent or grammatical errors as a quality issue. What the users expected, other than the quality of presentation (i.e. “smooth delivery, synchronicity, lack of hesitation”

(Donovan 2002, p. 5)), was accuracy of the renderings in the sense that the speaker’s message is conveyed. In terms of how users perceive grammatical errors, which B is prone to more so than A (Adams 2002), Kurz (1993) also reports that correct grammatical usage is considered less important or even the least important quality

criterion by certain user groups. Content accuracy is almost viewed as the basic requirement that the users expect from the interpreting service as Donovan noted and thus this study believes content accuracy is the most important criterion to evaluate interpretation quality on the basis of user’s point of view. Donovan indeed marked that users rated content accuracy and presentation quality to be essential and they did not seem to be concerned with interpreter’s language direction. An inference may be drawn on the basis of the above studies and that is, as long as quality justifies, users do not necessarily consider interpreting into B unacceptable.

Denissenko (1989, cited in Szabari 2002) suggests that “conveying a full or near full message even in a somewhat less idiomatic or slightly accented language serves the purpose much better than an incomplete or erroneous message albeit elegantly worded and impeccably pronounced” (p. 15) and Shlesinger (1997, cited in Szabari 2002) who believes in the latter case that the listener may go even unnoticed that the message is distorted or lost.

Other arguments favoring A-B point out to a slightly different direction. A theoretical discussion supporting working into B focuses on the role of non-verbal components of discourse. Seel (2005) is another example. The rationale behind Seel’s study is the idea that interpreters working in the direction of B-A do not necessarily have the required knowledge of the source culture and therefore do not have the advantage of taking non-verbal clues as completely and as rapidly as working in A-B.

Another shortcoming of working into A as it is also criticized for is a weaker memory capacity for receiving input in B compared to input received in A (Call 1985). The memory capacity for one’s native language is nine words but only five words for

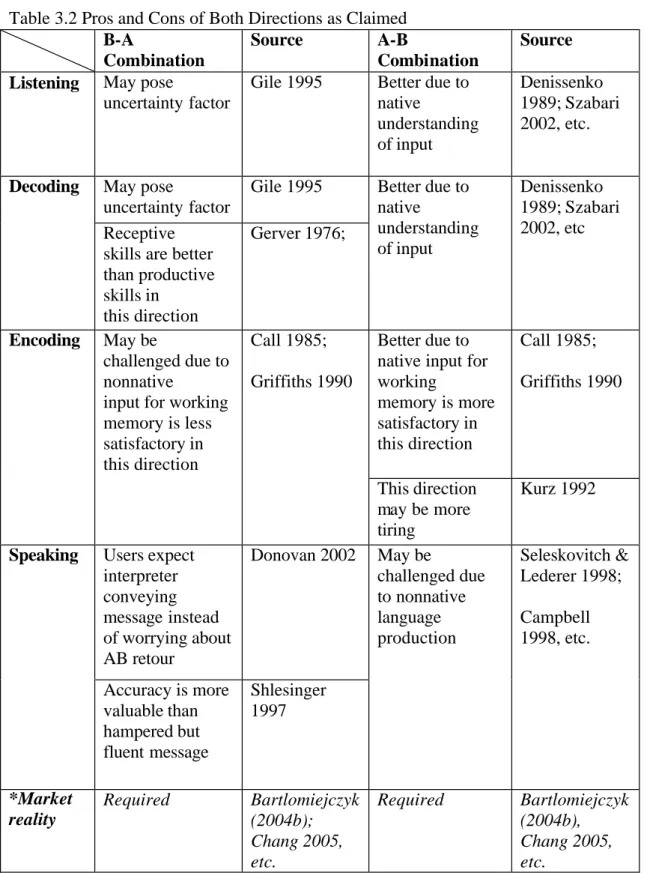

second language (Griffiths 1990). Aided by literature as reviewed, three major arguments and concerns favoring working in to B are sorted out (See Table 3.1) as (1) driven by market reality, (2) a better input comprehension and (3) content accuracy is more important than linguistic flaws. Table 3.2 again uses Yagi’s four tasks in SI (1999) to summarize the arguments supporting both directions respectively.

Table 3.1 Most-cited Claims for working into B

_____________________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________________

1. Market Factor — As market in many parts of the world requires: Not all languages have an equal amount of B or C interpreters 2. Skill Factor — (a) Better input comprehension

(b) Content accuracy is important in interpreting and linguistic flaws, although may be a more likely occurrence in A-B, should not be used to challenge such priority

_____________________________________________________________________

Source: Complied by this study

Table 3.2 Pros and Cons of Both Directions as Claimed B-A

Combination

Source A-B

Combination

Source Listening May pose

uncertainty factor

Gile 1995 Better due to native

understanding of input

Denissenko 1989; Szabari 2002, etc.

May pose

uncertainty factor

Gile 1995 Decoding

Receptive skills are better than productive skills in this direction

Gerver 1976;

Better due to native

understanding of input

Denissenko 1989; Szabari 2002, etc

Better due to native input for working

memory is more satisfactory in this direction

Call 1985;

Griffiths 1990 Encoding May be

challenged due to nonnative

input for working memory is less satisfactory in this direction

Call 1985;

Griffiths 1990

This direction may be more tiring

Kurz 1992

Users expect interpreter conveying message instead of worrying about AB retour

Donovan 2002 Speaking

Accuracy is more valuable than hampered but fluent message

Shlesinger 1997

May be

challenged due to nonnative language production

Seleskovitch &

Lederer 1998;

Campbell 1998, etc.

*Market reality

Required Bartlomiejczyk (2004b);

Chang 2005, etc.

Required Bartlomiejczyk (2004b), Chang 2005, etc.

Source: Compiled by this study

3.2 Factors that Determine SI Directionality

As discussed earlier, a difference exists between working into A and working into B based on the pros and cons of either direction. The issue of directionality is also driven by the availability of interpreters who can speak a certain language

combination so AB retour is inevitable in many parts of the world. As we take the matter one step further, factors which seem to affect SI directionality surface and their existence question the direction of B-A ever assuming the standard role.

The effect of these factors can be observed and assessed in the end product, that is, the SI performance, in terms of content accuracy and presentation quality.

Note that many surveys conducted in the past by numerous authors such as Gile, Kurz, Bühler, Kopczynski and AIIC Research Committee report mentioned by Donovan (2002) have generally indicated an “emphasis on content accuracy and the need to focus on specific requirements of listeners.” For instance, AIIC reported “the criterion most frequently mentioned by participants in evaluating SI is accuracy of content.”

(Donovan 2002, p. 2) Additionally, Seleskovitch (1986, Cited in Kurz 1993) believes that “interpretation should always be judged from the perspective of the listener and never as an end in itself” (p. 314) when the “ultimate goal must obviously be to satisfy our audience.” (Déjean le Féal 1990, cited in Kurz 1993, p. 314) Therefore, this study makes use of Donovan’s findings (2002) regarding user’s expectations and needs in SI as benchmarks to examine the factors which are identified to have an effect on the quality of AB retour. According to Donovan, users have two major expectations of interpretation: content accuracy and quality of presentation (See 3.1.2.3 for more details), this study thus points out how the identified factors may affect the tasks in SI in relation to these expectations.

3.2.1 Language-Specific Combination

Based on the findings of an Arabic/English SI study conducted by Al-Salman

& Al-Khanji (2002), a majority of participants in the SI study showed higher interpreting efficiency (on the basis of the strategies they adopted) in the direction of A-B rather than B-A. When interpreting from English (B) to Arabic (A), more reduction/unsuccessful strategies (i.e. message abandonment, incomplete sentences and literal interpretation, etc.) were adopted than achievement/successful strategies (i.e. anticipation and approximation, etc.). Yet when working from Arabic to English,

“the reduction strategies found in the Arabic interpretation did not appear in English interpretation, and their occurrence here was frequently low.” No incomplete sentences were observed when English/B is the target language. Al-Salman & Al- Khanji also provided questionnaires for the interpreters to fill out. The majority of respondents/interpreters reported to feel more comfortable interpreting from their native langua ge into the nonnative language. Al-Salman & Al-Khanji (2002) also drew the conclusion that “it may not always be the case that people generally perform the same task (in speaking or in interpreting) less well in a second language than in a first.” (p. 624) Based on Donovan’s findings on interpreting quality as users judged, the performance of the interpreters in Al-Salman & Al-Khanji’s study are also considered better when interpreting into English/B for less reduction (unsuccessful) strategies were employed (i.e. lower frequency of literal translation and no incomplete sentences, etc.).

Al-Salman & Al-Khanji brings up an interesting comment by indicating that even in the case when Arabic is the dominant language, production in Arabic may not be as easy as comprehension in it because a difference exists among the use of

colloquial, standard and classical Arabic especially when it is the target language.

This may be further supported by the questionnaires in which 90% of interpreters reported to have better oral fluency when working into English (B) and 70% indicated syntactic demand hampered transfer strategy when interpreting into Arabic (A).

Al-Salman & Al-Khanji took the time to describe the three registers of Arabic.

Colloquial Arabic is what the Arabic native speakers “begin developing as they acquire the language, and it serves as the medium for most spoken interaction throughout life.” (p. 621) Standard Arabic on the other hand, is similar to learning a foreign language because it is “learned rather than acquired.” (p. 621) Therefore, more educated people may be able to orally use the standard form of the language in formal discussions as required more effectively than the less educated ones as Al-Salman &

Al-Khanji suggested. Regarding the third type of Arabic use, the classical Arabic, it is totally a different and even not a “spoken language.” (p. 622) It seems that classical Arabic has its own rules of syntax and vocabulary and the use of it can also depend on context based on Al-Salman & Al-Khanji’s account. The three uses of Arabic are very different phenomenon as the two researchers indicate. When interpreting from English to Arabic, code switching may be required and most of them occur, for example, when the speaker starts to read from the written text which usually has more

“sophisticated vocabularies, more complex syntax and more complex semantic and pragmatic implicatures.” (p. 621)

Al-Salman & Al-Khanji’s study shows that working into A can be more difficult in some cases (i.e. English as the source language & Arabic as the target language) and produce less efficiency in interpreting as reduction (unsuccessful)

strategies are adopted more frequently when interpreting from English to Arabic because the language characteristics can affect the encoding stage in SI. For example, code-switching is more frequently adopted when interpreting into Arabic “as an easy way out to use the informal form of Arabic instead of the demanding standard Arabic”

(p. 619) and interpreters summarized the message they failed to convey in the standard Arabic. This may be additionally supported by the questionnaires which showed 80% of interpreters pointed out that they resorted to non-standard slang when immediate retrieval of an equivalent failed when the target language was Arabic. The possibility is that the issue of directionality may be more complicated than just the discussions between working from and into native language, as Bartlomiejczyk (2004b) stats near the end of the study that such “intrinsic qualities” (language specificity) “may sway interpreters’ opinions and preferences regarding the language combinations they work in quite independently of the given languages being native or non-native for them.” (p. 247) Al-Salman & Al-Khanji’s study shows that working into A can be more difficult in certain language combination (i.e. Arabic A/English B).

Whether this is also true for other languages certainly is a matter that requires future research.

Note that Gile (1997) addresses the same concern by introducing the term

“language specificity”. With other things being equal, some languages may be easier to work into because it requires “fewer processing capacity related problems in production” (p. 210) while others are easier to work from due to “lower requirements in comprehension.” (p. 210) Such differences are contributed to “word length, redundancies, lexical coverage, syntactic flexibility, and so on.” (p. 210) Gile further implies that one should take language specificity into consideration and question

whether work into B necessarily generates poor production quality since language specificity may offset the drawbacks related to an interpreter’s deficiency in his/her B language. To illustrate the “intrinsic requirement of specific languages in terms of listening effort and/or in terms of the production effort”, Gile uses Chinese and Japanese as languages that “could be more vulnerable in the listening effort because of the lack of redundancy” and because the two languages have many “short words and homophones and few grammatical indicators.” On the other hand, languages may pose higher production effort if they have “a limited vocabularies and a rather rigid grammar that imposes strict conditions on order of elements in the sentence as well as grammatical agreement conditions.” (p. 209) The idea of language specific combination determines directionality is further discussed by Bartlomiejczyk (2004b), who also suggests the language-specific factor may be at work in the task of interpreting. AB retour may have been under the influence of what the source and the target language are since various language combinations do not seem to pose equal level of interpreting difficulty in AB retour.

“Some languages, (e.g. English) seem to pose fewer difficulties and involving less production effort as target language than others, and some require extra listening effort (e.g. Chinese and Japanese) or an extra strain on the memory effort (e.g. German) as source language.” (p. 247)

Chang (2005) conducted an SI study focusing on the impact of interpreting direction on SI performance and interpreters’ strategy use. Chang uses propositional analysis (for semantic content) and error analysis (for linguistic quality) as criteria to measure participants’ SI performance. Seven out of nine interpreters showed

consistently better performance in terms of higher output propositional accuracy when interpreting from English to Chinese. On the other hand, in terms of error analysis of

language (errors per minute), all interpreters made more errors when interpreting from Chinese to English, although those who reported equal dominance in both languages showed a smaller gap in the number of language error across language direction. For all except one participant, “the frequency of presentation errors did not seem to be affected very much by interpreting direction.” (p. 64) Again when content accuracy is used to measure the interpreters’ performances in Chang’s study, performance yielded better results when interpreting from English to Chinese on the basis of more correctly rendered propositions. Note that Chang (2005) also mentions the language effect on directionality as observed and it echoes with Gile and Bartlomiejczyk in suggesting how Chinese may be a language more difficult to listen to (i.e. compared to English) as follows:

“The language in which the source text was delivered, i.e. Chinese or English, appeared to be more important to the interpreters’

processing of information. As already exemplified above, Chinese and English require the interpreters’ attention to different

areas, both in terms of comprehension and production. Without exception, all participants claimed they needed to “listen harder” for Chinese.” (p. 102)

It is interesting that all participants who were professional interpreters in Chang’s study were indeed native speakers of Chinese with three of them actually either reported dominance in English or reported equal dominance in both languages.

However, all of them unanimously indicated that Chinese was harder to listen to compared to English, regardless in which language direction they performed better.

When interpreting from Chinese to English, interpreters made more inferences as the participants described “many words left unsaid” and sometimes “illogical”.” (p. 106) Change’s study serves as empirical evidence that supports Gile (1997) and Bartlomiejczyk (2004b) who are convinced that some languages, such as Chinese,

require more listening effort as a language-specific factor that may thus influence the task of interpreting. In other words, directionality may be subject to the type of language involved since some languages do not seem to pose equal or similar levels of difficulty regarding interpreting tasks. A-B or B-A may not always be a better or a worse direction to work in for it may involve the actual language combination at work.

3.2.2 Context

Chang (2005) presented her Chinese/English SI research findings, which suggest interpreter use different strategic approaches to deal with different requirements of interpreting into A and interpreting into B; this result concurs with that of Bartlomiejczyk (2004a) in a Polish/English SI study. The majority of interpreters in Chang’s study received a higher score in terms of prepositional accuracy while interpreting into Chinese. Chang additionally presents three important determinants affecting directionality in SI as observed. They are contextual factors, personal factors and norms.

The first condition, the contextual factors, refers to the context of interpreting.

For instance, time, place, and participants that are involved in the interpreting situation are found to pose more effect on the direction of interpreting from Chinese to English than the other way around (Chang 2005). For example, the place where the experiment took place in Chang’s study was an artificial setting and when the Chinese speaker started by greeting which literally translated as “‘Hello, everyone’, almost all participants recalled “for not being able to decide whether to say ‘good morning’ or

‘good afternoon’” as hesitation occurred. Note that according to Donovan (2002), one of the two major expectations from users is presentation quality which includes

fluency (i.e. lack of hesitation). It seems that as Chinese being a more difficult source language, hesitation can arise during the stage of encoding and thus the performance may be penalized by users’ standard. Chang also mentioned that many participants felt “uncertain about which pronoun to use for many of the Chinese null-subject sentences because of a lack of sufficient information about the composition of the audience.” (Chang 2005, p. 101) Al-Salman & Al Khanji’s findings also seems to echo with Chang on the part that context can also influence directionality. The three varieties of Arabic (the colloquial, standard and classical Arabic), which shift from one to another based on context, creates more interpreting difficulty when Arabic is the target language (As opposed to English). Evidence of such difficulty is that the interpreters in Al-Salman & Al-Khanji study also filled out a questionnaire and 70%

indicated that their switch mechanism was at its best when interpreting from Arabic to English.

Features of the source text are also considered as contextual factors. For example, numbers were found to be problematic in both directions as far as the Chinese/English language combination is concerned as Chang records that the

“interpreters made more errors and omissions when it came to numbers.” (p.102) In addition, what seems to make Chinese harder to listen to, other than the factor of language specificity as Gile and Bartlomiejczyk point out, may also be contributed to one of the contextual factors (Who the speaker is) as Chang sees it. All interpreters/participants in Chang’s study on the part of retrospective interview commented on the problem of “Chinese speakers in general being ‘bad speakers’.” (p.

101) “For example, the interpreters reported to have more experience with “bad speakers” of Chinese texts in the way that the speeches were disorganized and lack of

logical connections.” (p. 96) Many even mentioned the challenge posed by interpreting from Chinese to English when it comes to Question and Answer sections.

“They had to consciously process the disorganized comment form the audience and produced a coherent English interpretation” (p. 97), as one participant even believed that the English listeners might in fact understand the message through the interpretation better than the Chinese listeners. Also on the basis of the opinions of the participants, Chang (2005) further specifies that Chinese as a language is harder to listen to (Comparing to English) due to the fact that the language itself has the tendency of “omission of subjects, loose use of connectives, and the rich meaning encoded in some Chinese usage” (p. 97), resulting in one of the reasons for Chinese speakers being considered bad speakers in general, as unanimously indicated by Chang’s participants (Regardless of their English proficiency) that “one needs to spend more effort understanding Chinese in order to interpret it into English.” (p. 98) This piece of evidence reflects what Gile and Bartlomiejczyk mention how Chinese may pose more listening effort as a source language under the consideration for language specificity. In other words, Chinese is more difficult to listen to as a source language because of its specific language characteristics which subsequently creates a negative impact on the way Chinese speakers conduct their speeches in general (As one of the contextual factors affecting directionality).

3.2.3 Personal Factor

Chang’s account for the second factor which determines directionality is a personal factor, including the interpreter’s language proficiency in the source and the target languages and his/her prior knowledge to the speaker, the topic and the

characteristics of the two languages that the interpreter works with. For instance, most

interpreters in Chang study “also reported adjusting their lag during interpreting based on their confidence in their memory in either language.” (p. 102) In terms of language proficiency, most of the participants in Chang’s study reported to have made use of various interpreting strategies because they were aware of their B language deficiency.

Some interpreters avoided unfamiliar expression by adopting strategies such as omission, paraphrasing or generalization. Such awareness of AB language gap affects their use of strategies in different directions “especially in terms of producing B language… .” (Chang 2005, p. 93)

“Moreover, there was a strong correlation between the interpreters’

self-perceived gaps in their A and B language proficiency and the gaps in the percentage of propositions they actually rendered when interpreting in different directions.” (p.120 & p.121)

3.2.4 Interpreting Norms

Last but not least, the third factor that is identified to pose impact on

directionality is the interpreting norms, which refers to what the interpreters believe their interpreting output should be like and what strategies are available to achieve the goal (Chang 2005). The interpreters in Chang’s study were found to share very similar ideas towards their interpreting output; for example, they believed interpreting should be “fluent, understandable, without long pauses, and in complete sentences.” (p. 104) They also indicated that literal translation should be avoided and the focus to convey important messages was the goal which Chang believed was the result of their training and years of experience.

The linkage here is, when interpreters hold a certain belief towards how to perform in a certain direction, such belief no doubt has an impact on that particular

direction. Donovan (2002) also mentions that most interpreters in the survey tend to focus on getting the message across instead of worrying too much about the style of their delivery as they worked into B. This may be the result of one of the teaching strategies adopted for interpreting into B known as the KISS principle: “Keep in short and simple.” (Adams 2002; Minns, 2002; Rejšková 2002)

“Stay away from colloquial expressions, they may be too colloquial or simply wrong for the native speakers of the language (including the interpreter relying on your input), and - replace idiomatic phrases,

proverbs with a more straightforward, less embellished message.”

(Rejšková 2002, p.33)

“However, a ‘B’ remains a B, when in doubt, students should “KISS”.”

(Minns 2002, p.37)

“When working into B, he is best advised to use only previously “verified" solutions, i.e. those which he had already heard uttered by native speakers. The booth is not the place to test whether the listeners understand linguistic solutions the interpreter tries out for the first time .” (Szabari 2002, p.17)

Interpreting norms like these which have been implemented to interpreters since they were beginners definitely shape the way they interpret in a certain direction.

This may also explain why Chang (2005) observed that the interpreters in her study were inclined to avoid unfamiliar phrases and adopt various strategies, such as paraphrasing and generalization, when work into B as mentioned earlier. Chang additionally marks the observation of the “language norms of the source and the target languages which also affect the interpreters’ comprehension and production process.”

(p. 105) The interpreters in Chang’s study paid more attention to their grammar, sentence structure and logical links when working into B. They also considered it was

“important to go beyond the surface of the original Chinese text and to express both the explicit and implicit message obtained in the text” when interpreting from Chinese

to English (p. 105). The present study suspects the fact that Chang reports more attention is allocated to “making cultural adaptations” when working into A (p. 105) may be due to the fact that B-A is less restricted to the effect of KISS principle as a possible explanation.

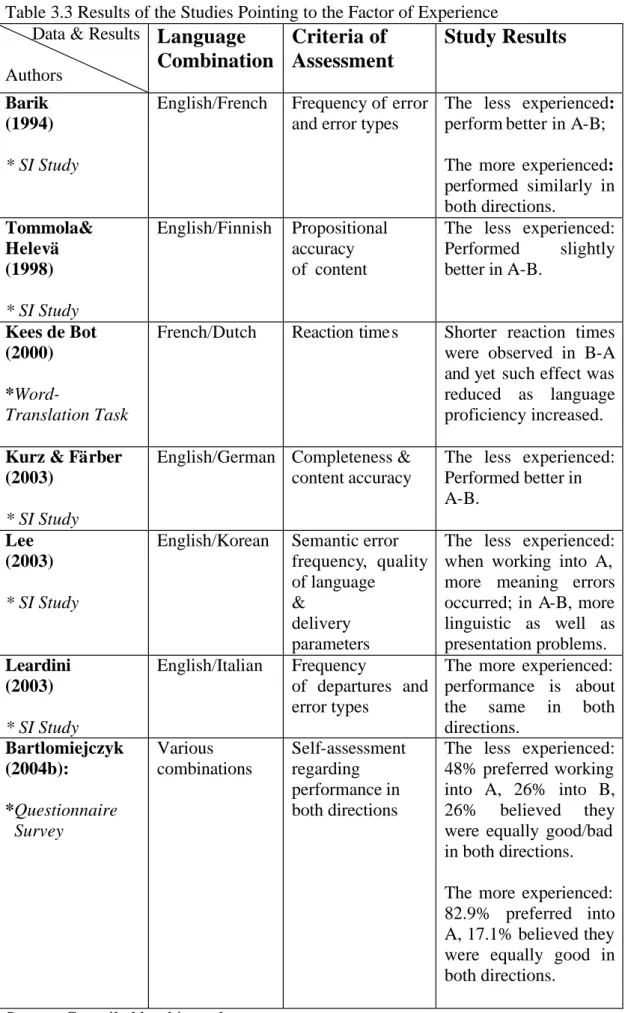

3.2.5 Experience

Compared to the inexperienced interpreters, Lawson (1967) believes the more experienced are less sensitive to the effect of directionality. Barik (1994) carried out a SI study examining the relationship between various proficiency levels of interpreters and omissions, additions and substitutions they make. Although directionality was not a concern in the study, Barik did reported an observation in which he discovered that the more experienced interpreters made “about the same omission measures” in both language directions, while the less experienced interpreters interestingly did better interpreting from A to B, “making fewer omissions and omitting less material in that situation than when translating from their weaker into their dominant language… … ” (p. 134) The amateurs were in fact even more likely to render a word-for-word

translation instead of “interpretation” of the source message in B-A comparing to A-B, while the professionals were “substantially more in agreement with the idiom of the target language.” (p. 135) Once again in terms of interpreting quality from user’s standpoint, let us not forget Donovan (2002), who clearly indicates that users do not want a literal translation from the interpreter; instead, they expect task be done in

“getting the speaker’s point across.” (p. 5) Therefore, Barik’s findings here may be referred to the fact that the less experienced interpreters rendered a better interpreting quality in A-B as far as users are concerned. Also when working in A-B, the less experienced interpreters on average showed fewer disruption and fewer serious errors

(p. 136) based on Barik’s error index (See Appendix I for Barik’s error index as summarized by this study). Although the experienced interpreters might be more seriously penalized by the error index compared to the less experienced in some cases, Barik did put foreword the fact that the error index itself was mostly concerned with changes in meaning, not the overall interpreting performance. This meant that the amateurs’ translations were less intelligible and those of the professionals were more flexible and thus prone to paraphrasing which was something that the error coding system could not reflect. Barik did admit that the error index was not to be taken as a perfect one since it only calculated errors in a general way and could not reflect the overall quality of the interpretation. In general, Barik’s study may suggest that the more experienced interpreters performed relatively steady in AB retour but the less experienced were less so in that A-B seemed to generate more satisfactory results.

A slight advantage of working in A-B was recorded by Tommola and Helevä (1998), who conducted a SI study (English/Finish) on directionality concerning linguistic complexity of the text with trainee interpreters. Tommola and Helevä (1998) assessed their performa nces with propositional accuracy. The results indicated a slightly higher accuracy in the interpreters’ renderings while in A-B than B-A.

“… linguistically more complex source texts produced a lower propositional accuracy score than did linguistically simpler and more redundant texts. However, there was no statistically

significant effect of the language direction in which interpretation proceeded, although the data revealed a slight trend suggesting that when the subjects were interpreting from their mother tongue into their B language, more propositions were correctly rendered.” (p. 184)

The two authors also suggest it is possible that source text complexity may pose less negative impact on more experienced interpreters because their lexical access and

syntactic parsing “are more automatized and modularized.” (p. 184) The implication here is that experienced interpreters can process a message more effectively than inexperienced interpreters “who may be faced with information overload which has an adverse effect on the quality of the performance.” (p. 184)

More recent psycholinguistic researchers, such as Kees de Bot (2000) who also believes that such asymmetry effect across language direction can be reduced with increased proficiency of the interpreter. Kees de Bot conducted a word

translation task (Dutch/French) for the groups of intermediate participants, advanced participants and near-native participants in terms of their language proficiency. While each group has 14 subjects, they “sat in front of a screen on which a stimulus word was presented. They had to say the translation of that word as quickly as possible” (p.

81). The results showed that a clear effect on translation direction but the “difference diminishes with increasing proficiency.” (p. 82) A verification task was also

conducted to test if participants had the lexical knowledge of the words tested but had difficulty rendering the translation in due course. The verification task had the same grouping but involved different individuals who mus t indicate if the Dutch word and the French word both shown on the screen were translation equivalents. The results showed a “significant effect of level of proficiency, in particular for the lowest level of proficiency” the reaction times were significantly prolonged (p. 83). What is important about Kees de Bot’s study is that although shorter reaction times were observed in the direction from the weaker into the dominant language, such effect was reduced as proficiency increased. Again Kees de Bot discusses the possibility that experience may be a factor that influences directionality; the more experienced

interpreters may be less sensitive to the effect of interpreting direction compared to the inexperienced.

In addition, Kurz and Färber (2003) conducted a SI study which involves seven native German interpreting students and seven native English interpreting students. Unlike Barik who applied error index as assessing criteria, Kurz and Färber measured the performance in terms of completeness and content accuracy. The results showed that students performed better in A-B and supported those of Barik in 1994 on the part that the less experienced interpreters seemed to perform more satisfactorily when working into B.

Lee (2003) had nine beginning SI students from Monterey Institute of International Studies to interpret a Korean speech into English and another speech in the opposite direction. Semantic error frequency, language quality & delivery parameters were the assessing criteria. Lee discovered that whe n student interpreters working into A, more meaning errors were observed than working into B. More language and presentation problems were found in A-B for these student interpreters.

Lee’s observation may also suggest that experience does play a part in the quality of directionality and that students are prone to producing more meaning errors in B-A.

Again to translate the results into Donovan’s findings based on users’ standpoint, the interpreting efficiency is probably higher in the A-B direction in this particular study since content accuracy is considered the basic requirement (As Donovan indicates) that a good interpretation cannot do without.

Leardini (2003) conducted an observational study investigating SI at two medical conferences. All the SIs were performed by the same group of interpreters who had English A and Italian B as they worked both ways. Frequency of departures and error types were measured in the study and the findings indicated that directionality did not affect these interpreters in the completeness and fidelity of their renderings. Once again more proof pointing to the direction that the more experienced interpreters seem less influenced by language directions. In other words, interpreters with more experiences seem less affected by AB retour while the less experienced ones generally show a more desirable performance in the A-B direction.

Bartlomiejczyk (2004b), after conducting a directionally study using questionnaires survey, provided results which showed that most professional interpreters preferred working into A but only half of the student interpreters felt the same way while 26% indicated they preferred A-B. Bartlomiejczyk attempted to offer an explanation for the phenomenon. Such a difference between the two groups “might be explained as a result of students having too high an opinion in their own mastery of their B language.” (p. 246) This means that students may not know the many errors they make in B but they do notice them when working into A. A second possibility contributing to the difference is that “there is a stage in interpreting training where students do perform better interpreting into a foreign language.” (p. 246) Professional interpreters generally thought that they performed better when working into A as 82.9% indicated so. No professional interpreters seem to suggest they perform better when working into B. More important, 39% of those professional interpreters who indicated a preference working into A actually reported that such difference (into A and into B) was small for them (reflected in grades by only one point).

This study found something interesting in Bartlomiejczyk’s study and before the discussion proceeds, the researcher of this study wishes to first explain why taking the group of student interpreters as an example for the following discussion instead of using the professional ones. The truth is, 35 out of the 40 professional interpreters involved in Bartlomiejczyk’s questionnaire survey were indeed AIIC members and whether their opinions regarding directionality stood neural was unclear but it was a concern noted also by Bartlomiejczyk. Therefore, this particular group of respondents was disregarded in the following discussion. The student interpreters were recruited from two different schools that did not particularly encourage work into A or into B and students were required to be able to work in both directions by the schools so their opinions were more likely to remain neutral on the issue.

Now, what’s interesting about Bartlomiejczyk’s survey results is that an indication of the 53 student respondents who show mixed opinions towards directionality is made. “26% of the students respondents thought themselves to be equally good (or equally bad) in both directions, and 74% made a distinction in their estimation depending on the direction: 48% though they interpreted better from B into A, 26% from A into B.” (Bartlomiejczyk’s 2004b, p. 242) The research of this study finds the disagreement intriguing and subsequently looks into the background information of these student respondents. Most of them had learnt interpreting for 3-4 terms and were between the age of 22~24. The only significant difference posed by these 53 student interpreters as could be viewed from the study was that they had different language combinations. As Bartlomiejczyk’ stated, 32 of the student respondents (From the University of Silesia) had Polish A and English B while some of them also had an additional B or C language(s). The other 21 subjects (From the

Vienna Institute) in fact had “a wide variety of A, B and C languages” (p. 242) while all of them had German as A or B. Other A and B involved including English, French, Hungarian, Polish, Russian and Spanish as listed by Bartlomiejczyk. While respondents/participants in many other studies as reviewed earlier in this study often indicated a consistent agreement concerning directionality and their language combination in each of these studies did not vary (Meaning only one language combination in each study was tested), the researcher became curious again in the possibility that specific language combination may be another factor at work when it comes to the issue of language direction in interpreting. The general observation in Bartlomiejczyk’s study is that students’ opinions are not similar to those of the professional interpreters in terms of interpreting across language direction and it remains consistent with what this study is inclined to suggest that experience as a factor is very likely to have affected interpreting across language direction.

It is important to note that this study certainly is not suggesting all inexperienced interpreters necessarily perform better in A-B (although it appears to be the general trend in the studies as reviewed) or all experienced ones always come up with nearly equal performance in both directions, but merely discussing the possibility that the less experienced interpreters can be more “sensitive” to the effect of language direction in SI in comparison to the more experienced ones who seem to perform more “steadily” and reduce the “gap” more effectively in AB retour. SI performance thus seems to be affected by their interpreting experience. Table 3.3 organizes the above studies that point to the direction suggesting experience may be a factor at work in AB retour.

Note that Donovan (2002) specified that users, other than demanding presentation quality, “went to the trouble” (p. 5) of pointing out by accuracy they expected an interpreter to convey the speaker’s message instead of rendering a literal translation. Such expectation for production is also found in the self-constructed norms that interpreters develop as their experiences increase and gradually change the way interpreters approach how they want to interpret/speak according to Chang (2005). To probe further into the matter, Chang states that self-constructed norms of interpreters can be established as the interpreter becomes more experienced and these norms have an impact on how interpreters wish to approach the task of interpreting.

For instance, many interpreters in Chang’s retrospective interview indicated that as they became more experienced in interpreting, they began to focus on the need of the audience (users) and the need to get the message across instead of worrying about how well they could translate the words or every word (Better quality in terms of content accuracy according to Donovan’s users expectations), as they gradually came to believe what interpreting should be like. Whether this may be one of the reasons that the more experienced interpreters perform more steadily in both directions than the inexperienced is another interesting point that no doubt deserves further research attention.

Table 3.3 Results of the Studies Pointing to the Factor of Experience Data & Results

Authors

Language Combination

Criteria of Assessment

Study Results

Barik (1994)

* SI Study

English/French Frequency of error and error types

The less experienced:

perform better in A-B;

The more experienced:

performed similarly in both directions.

Tommola&

Helevä (1998)

* SI Study

English/Finnish Propositional accuracy of content

The less experienced:

Performed slightly better in A-B.

Kees de Bot (2000)

*Word-

Translation Task

French/Dutch Reaction times Shorter reaction times were observed in B-A and yet such effect was reduced as language proficiency increased.

Kurz & Färber (2003)

* SI Study

English/German Completeness &

content accuracy

The less experienced:

Performed better in A-B.

Lee (2003)

* SI Study

English/Korean Semantic error frequency, quality of language

&

delivery parameters

The less experienced:

when working into A, more meaning errors occurred; in A-B, more linguistic as well as presentation problems.

Leardini (2003)

* SI Study

English/Italian Frequency

of departures and error types

The more experienced:

performance is about the same in both directions.

Bartlomiejczyk (2004b):

*Questionnaire Survey

Various combinations

Self-assessment regarding performance in both directions

The less experienced:

48% preferred working into A, 26% into B, 26% believed they were equally good/bad in both directions.

The more experienced:

82.9% preferred into A, 17.1% believed they were equally good in both directions.

Source: Compiled by this study

3.3 Directionality: An Issue More than Native vs. Non-native

This chapter presents the discussion on directionality. Market reality for one, was and still is a fact today that AB retour in many parts of the world. Working into A could not have been a standard practice or a tradition if strictly putting it to work is practically difficult, if not totally impossible. Some places indeed consider working into B as a dominant practice under certain situations (i.e. Major international events) in Central and Eastern Europe (Szabari 2002) and there are those who basically stand neutral on the issue by indicating the necessity for AB retour (i.e. the Institute of English, University of Silesia, Poland and the Institute for Translation and Interpreting, University of Vienna, Austria, Bartlomiejczyk 2004b).

Directionality may be affected by various factors so the quality of AB retour, (content accuracy and presentation quality based on users’ account (Donovan 2002)), may not be consistently better or worse in either direction. Other than the fact that market reality demands AB retour in many places around the world, the interpreter’s experience, specific language combination, interpreting context, personal factors and norms together may determine SI directionality to a large extent. In other words, SI directionality is a complex issue rather than simply tangling on native and non-native languages can explain; the depth of the issue is very likely to have gone beyond the discussion of native vs. nonnative languages. Neither A-B nor B-A always produces a better interpreting quality; therefore under this rationale granting interpreting into A the standard status cannot effectively convince this study. All these raise further doubt that working into A was ever a worldwide standard put into practice by members in the interpreting community as it was suggested in the literature.