Chapter Three

Experimental Methods and Results

In this chapter, we will talk about the subject and research design of the present study. Section 3.1 describes the background of the subjects recruited for the formal study. In section 3.2, the materials and the research method are reported. Section 3.3 describes the research procedures (including a pilot study, a pretest, and the formal study). The results of the formal study which attempt to answer the four research questions stated in Chapter One are given in section 3.4 followed by a brief summary in section 3.5.

3.1 Subjects

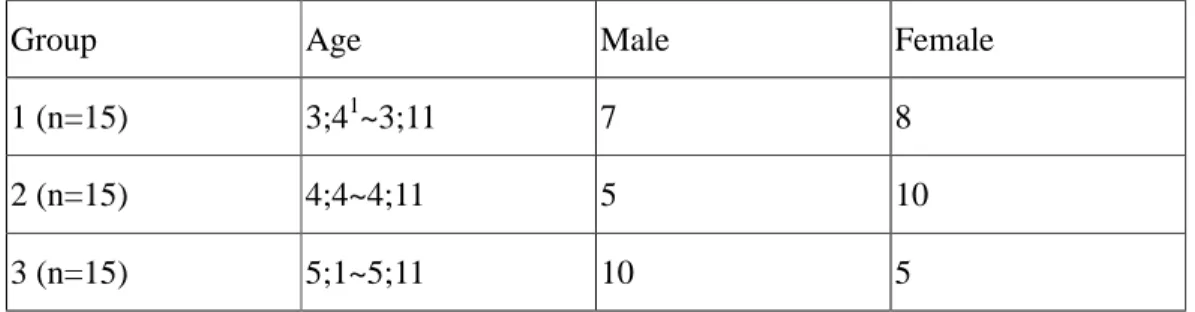

The present study conducted a quantitative experimental method to investigate Chinese-speaking preschoolers’ L1 competence. Forty-five Chinese children aged between three and five years old participated in the present study, as can be seen in Table 3-1:

Table 3-1: Background of Subjects

Group Age Male Female

1 (n=15) 3;41~3;11 7 8

2 (n=15) 4;4~4;11 5 10

3 (n=15) 5;1~5;11 10 5

The subjects in the present study came from two schools2: the affiliated kindergarten of National Taiwan Normal University and the affiliated kindergarten of Chung-Ching Junior High School in Panchiao, Taipei County. The two kindergartens

1 For example, 3;4 refers to three-year-and-four-month old.

2 There were not enough three-year-old subjects in the affiliated kindergarten of Chung-Ching Junior High School in Panchiao, Taipei County, so the researcher decided to recruit all three-year-old subjects from the affiliated kindergarten of National Taiwan Normal University.

selected in the present study were not bilingual (English/Chinese). The major language used for communication was Chinese3. The subjects were native speakers of Chinese, who were currently learning Mandarin Chinese as their first language.

The schoolings in both kindergartens were roughly the same. The subjects attend the kindergarten five days a week. Their schooling was from 8 a.m. to 4 p.m. The class size for both kindergartens was around 25 preschoolers at the age between three to six years old. The subjects spent about one to two hours on reading activities every day. Like most preschoolers in other kindergartens in Taiwan, the subjects had both indoor and outdoor activities. For indoor activities, they drew pictures, watched cartoons, listened to stories and sang some nursery rhymes in Chinese, etc. For outdoor activities, they played in the sand, exercised on the playground and so on.

The results of the performance of each age group were compared to see if any differences were revealed, owing to the length of the time they have been exposed to Chinese.

3.2 Materials and Methods

“In any endeavor to analyze children’s acquisition of a given category, be it syntactic, semantic or functional, and at any given age of acquisition, we should look into both production and comprehension. Looking at only one side of the coin could lead to extrapolations which are only narrowly valid.” (Karmiloff-Smith 1972, p.61) Therefore, both production and comprehension tasks were conducted in the present study with a view to obtaining an unbiased analysis.

Generally speaking, there are three ways of eliciting language samples from preschoolers: (1) Mother-child or experimenter-child talk in the context of “free play”

3 According to one of the teachers at the kindergarten, although some subjects’ mothers were from Vietnam, Thailand, Burma, the dominant language at their homes was nevertheless Chinese.

either at home or in a specially designed laboratory where it is silent; (2) Teacher-child or children talk at preschools, oriented around play, instruction or school-keeping activities; (3) Experimental tasks designed to test “comprehension” of some terms or to elicit “productions” about the use of particular target terms (French and Nelson 1985, p.4). The first approach is more like a longitudinal study, observing a single subject for a longer period of time. To successfully collect “natural” data, it is important for the subjects to feel comfortable to talk to their mother with the researcher present. But it is not easy for the researcher to find such a subject. The second approach is challenging for the researcher to collect accurate data of different subjects in a classroom. If all the subjects are talking at the same time, the language data the researcher obtained will be a mixture of everything, which makes subsequent analysis unreliable. Owing to the drawbacks in the first two approaches, the third approach with specific experimental tasks was adopted in this study.

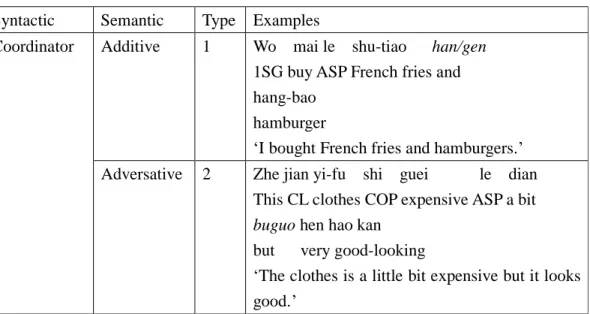

The present study included two experimental tasks: picture identification task (PI task) and story-retelling task (SR task). We adopted the classification of conjunctions below (see Table 3-2):

Table 3-2: Conjunctions Examined in the Present Study Syntactic Semantic Type Examples

Additive 1 Wo mai le shu-tiao han/gen 1SG buy ASP French fries and hang-bao

hamburger

‘I bought French fries and hamburgers.’

Coordinator

Adversative 2 Zhe jian yi-fu shi guei le dian This CL clothes COP expensive ASP a bit buguo hen hao kan

but very good-looking

‘The clothes is a little bit expensive but it looks good.’

Syntactic Semantic Type Examples

Causal NA4

Temporal NA

Additive NA

Adversative 3 Sui-ran ta hen qong buguo ta mei Although 3SG very poor but 3SG each ge yue juan qiang gei gueryuan CL month donate money give orphange

‘Although he is not rich, he still donates some money to the orphanage every month.’

Causal 4 Yinwei taifon yao lai le Because typhoon want come ASP suoyi dajia mang zhe fang tai so everyone busy ASP against typhoon

‘Because the typhoon is coming, everyone is busy taking some precautionary steps.’

Subordinator

Temporal 5 Bishi guo le yihou Pencil test pass ASP after ranhou zai qu mianshi then DUR go interview

‘After you pass the paper-and-pencil test, you will be interviewed.’

Additive NA

Adversative NA

Causal NA

Macro-syntac tic

conjunctions

Temporal 6 ……suiran zaoyu hen duo kunnan Although endure many difficulties Zhuihou tamen guo zhe kuaile de shenghuo At last 3PL live ASP happy DE life

‘…although they endured lots of difficulties, at last (finally), they lived a happy life thereafter.’

Supposedly, there should be twelve types of conjunctions based on the syntactic and semantic classifications. However, some types are not possible. For example, coordinators in Chinese are usually used to connect phrase-level elements (NPs, VPs, etc.), which are never involved with causal or temporal relations. As for subordinators,

4 NA means “not applicable.” That is, there is no proper example for the given type.

they are used to connect clauses involved with adversative, causal, temporal relations but never additive relations. Moreover, macro-syntactic types are intrinsically at a higher level beyond phrasal and sentence levels. The only macro-syntactic conjunction which involves temporal relations in the present study is zhuihou. There are no appropriate conjunctions denoting the rest three semantic relations. Therefore,

“NA” was given in the table to indicate the nonexistence of these types. Totally, there were six types of conjunctions examined in the present study.

After carefully classifying the conjunctions based on their syntactic and semantic properties, let us look at the procedures of the two tasks. The PI Task (see Appendix A) was a comprehension task used to test whether the subjects can comprehend the use of conjunctions connecting phrases, clauses, and sentences. In this task, we presented six comic strips to the subjects one by one.

The SR Task (see Appendix B), was a production task, which explored how the subjects used conjunctions to connect clauses, phrases, or even paragraphs in a larger discourse context. Some preschoolers may have some basic ideas in their mind what conjunctions are. However, when asked to orally produce some sentences such as story-retelling, they may not use conjunctions properly. Our SR task was intrinsically different from the PI Task because it required the subjects to produce longer utterances, more like a discourse. We would like to see which conjunction(s) appear(d) to be more frequent in their story-retelling.

The storybook adopted in the story-retelling task will be The Adventure of the Big Wolf. Below is a summary of the story:

Long time ago, there was a big wolf living in the forest. However, he often felt lonely because there were not many animals in the forest. When he felt bored or hungry, he had no animals to talk to or to eat. Therefore, he decided to leave the forest to a nearby grange.

At first, he went into a hen house and found some little chicks. As the big wolf thought that he might have a wonderful “chicken feast,” a brave zebra came and rescued the chicks. Feeling hungry and frustrated, the wolf walked to a swamp where he found many little pigs taking a shower. As he opened his big mouth, the piglets were frightened and ran away immediately. The wolf then comforted himself, expecting there must be some delicious animals ahead. Indeed, there were some such as the ducks, the cows, and the rhinoceros. But the wolf’s attempt to eat them failed.

He was later attacked by the fierce crocodile and the giant elephant.

The wolf found himself seemed not popular among the animals. He believed that he was so weak that he could never find food to eat. At this moment, a rabbit with a cart of carrots walked by. The rabbit asked him what happened. After knowing what happened, the rabbit treated the wolf with one carrot. From then on, the wolf found the taste of vegetable was not bad. Finally, he decided to stay in this grange. Most important of all, he became a “vegetarian” so that other animals were not afraid of making friends with him.

3.3 Procedures

In this section, the procedures of a pilot study as well as the pretest of the formal study will be reported.

3.3.1 Pilot Study

In the pilot study, two tasks (picture description (PD) and story-retelling (SR)) were conducted to 45 subjects. In the PD task, the subjects were asked to take a look at a comic strip (see Appendix E). The words in the “dialogue bubble” of each picture had been erased first. Later, the children had to guess and complete the possible dialogue between the two characters in the comic strip. In the SR task, each age group first listened to the story told by the researcher; soon afterwards, they were required to

retell the story with the picture book one by one in a corner. For other children waiting to retell the story to the researcher, they were asked by their homeroom teacher to draw pictures of the animals they had just heard so as to refresh their memory.

It was found that very few conjunctions were produced by the subjects in the PD task, probably because the sequence of the picture was not clear to them. In addition, ranhou was found to be the most frequent conjunction in both tasks.

A causal conjunction like yinwei (and) and the adversative conjunctions such as keshi (but) were also frequently produced in the SR task. Other conjunctions such as jieguo (as a result), erche (moreover), buguo (however), and danshi (but) were found in some subjects’ utterances, but there was an individual difference. For example, erqie (moreover) was used by 2 four-year-old and 2 five-year-old subjects and danshi (but) was used only by 1 five-year-old subject. The results of the SR task using The Adventure of the Big Wolf showed that the subjects at the age of five generally used more conjunctions than the three-year-olds. Our older children were generally capable of presenting the story in a more temporally and causally related manner.

Conjunctions such as zhongeryienji (to sum up), budan (not only) were not found in their production data. Adversative conjunctions such as keshi (but), danshi (but) were occasionally used. Among these low-frequency conjunctions, erqie (moreover) was occasionally used by 2 subjects at the age of four and five. Another finding was that one five-year-old subject always used nage (that) in the sentence-initial position, but never used other conjunctions except for ranhou (and then) whenever he started a new sentence.5

Indeed, there are a lot to be desired in the pilot study. The first problem was with the age differences of the subjects. We encountered some difficulties collecting data

5 Nage was considered a kind of “filler” instead of demonstrative or maker in the pilot study.

from the three-year-old kids. Although there seemed to be a developmental progression according to the subjects’ use of conjunctions, most if not all, the three-year-old subjects were not ready for the two tasks. The subjects who were too young often did not know what was going on and naively looked at the researcher with few words produced. The second problem was with the task itself. The SR task was generally fine because retelling the story was far easier than telling a new story all by the subjects. However, there was a big problem with the PD task. The picture consisted of several sequences and some subjects just said ‘they saw a dog and a cat and they are playing.’ No conjunction was produced for some obvious reasons. Since both the PD and the SR tasks were production tasks, we had no way to know how much the subjects comprehended conjunctions. Therefore, there is a need of a comprehension task for the follow-up study. Moreover, without a solid classification of conjunctions, the question about what types of conjunctions are acquired earlier is still left unexplored.

3.3.2 Formal Study

In the pretest, a PI task was given to the subjects to ask them to identify the correct picture (one out of the two) after they heard a sentence describing the picture.6

For the PI task, to decide the best way to elicit the subjects’ responses, we read one sentence to the subjects. The subjects had to first judge whether the sentence was OK or not (all six test sentences are grammatical). If the subject said the sentence was OK, then he/she would proceed to choose the picture. If the subject said the sentence was NOT OK, then he/she would NOT be given the chance to choose the picture (thus got zero point) and would proceed to the next question. For the subjects who said the sentence sounds OK (i.e., grammatical), then they had to choose one picture out of the

6There were 3 subjects (their age ranging from four to six years old) participating in the pretest.

two that corresponded to the sentence they heard. It was found that the older subjects tended to have better comprehension of conjunctions in Chinese (for more details, please see Appendix F).

For the SR task7, each age group first listened to the story told by the researcher, which lasted for about 15 minutes; soon afterwards, they were asked one by one to retell the story The Adventure of the Big Wolf8 with the picture book in a separate corner. All the subjects seemed to use more temporal conjunctions than the other types of conjunctions during their retelling. The six-year-old subject was the most fluent speaker and used all four types of conjunctions. On the contrary, the five-year-old subject only used temporal and adversative conjunctions whereas the four-year-old subject used only temporal and additive conjunctions.

In the formal study, we had two tasks: picture identification (PI) and story retelling (SR). The PI task were done first as it is easier for the subjects to complete.

Once the subjects finished choosing one picture, they proceeded to the next picture.

The overall time for the PI task was about three to five minutes for each subject. A tape recorder was used to record everything the subjects said throughout both tasks.

In the SR task, the researcher first read the story to the subject for about ten to fifteen minutes. Afterwards, each subject had to retell the story he/she heard with the storybook to the researcher individually. In other words, the researcher told the story to the subjects each by each and the subject retold the story immediately. The subjects

7 Originally, the researcher wanted to change the storybook in the pilot study “The Adventure of the Big Wolf” to “Frog, Where Are You? (Meyer, 1969)” because the frog story had been extensively used by previous researchers in first language acquisition and we could compare the results with previous findings. Below are some detailed descriptions of the two tasks (PI task and SR task) done by three subjects in the pretest of the formal study.

8 This storybook is rich in its illustrations and indeed attracts the subjects’ attention. The main idea of this story is chiefly about a big and hungry wolf hunting for other animals as food. Unlike the traditional impression we have on “wolf”, this wolf is awkward in catching animals as food and encounters some problems in the forest. Eventually, some animals such as giraffes and rabbits helped the wolf when he is in trouble. The wolf finally realizes two things: that helping others who are in need is valuable and that bullying those weaker is shameful.

were presented with the storybook The Adventure of the Big Wolf and were asked to tell the story back to the researcher. When the subjects encountered any difficulty to continue retelling the story, the researcher used some guided questions like “what happened to the wolf?” to help the subjects move on. Their narrations were tape-recorded, later transcribed, and calculated for data analysis.

3.3.3 Scoring and Coding

In this section, we will briefly explain how the subjects’ performances were scored in the PI task and how we counted the conjunctions based on their syntactic and semantic types in the SR task. The details are shown below.

In the PI task, if the subject could correctly identify the picture, then he/she got one point for the particular category of conjunction. If the subject did not have any response or respond incorrectly9 to the picture, no point was given. Since there were six questions, the score for this task ranged from zero to six.

In the SR task, the occurrences of all the conjunctions, which were coded according to their types, were counted and presented in percentages. As we mentioned earlier, we want to know which types of conjunctions were frequently or rarely produced in a longer narrative.

After the scoring in the PI task, two raters first classified the occurrences of conjunctions into syntactic and semantic types. Each rater was asked to classify the occurrence of a conjunction with a syntactic label and a semantic label. If they disagreed, a third rater was consulted for a final decision. The data of each task were then entered into SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Science) and processed by the computer.

3.4 Results

9 If the subject(s) showed hesitations, not knowing which picture to choose, then he/she will still be given zero point for that test item.

This section presents the results of the PI and SR tasks. In each task, the group effects on the syntactic and semantic properties will be discussed.

3.4.1 The PI Task

3.4.1.1 Subjects’ Performances on Syntactic Conjunctions

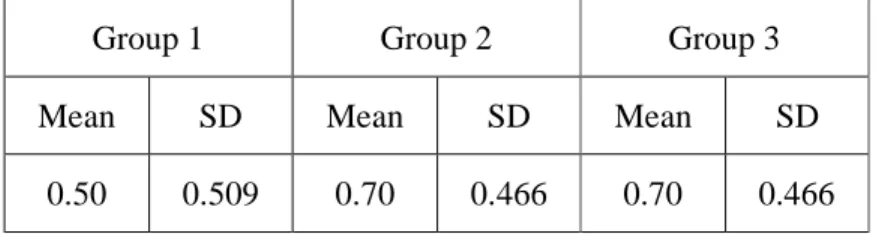

In the PI task, for each test item, the subjects were given two pictures together with one stimuli question. If the subject chose the correct picture with no hesitation, which meant he/she could comprehend the meaning of that conjunction and identify the correct picture, then he/she would be given one point. However, if the subject failed to choose the correct picture, no point would be given for that test item. Later, the subjects’ scores were added up and then divided by 15. The average mean of each group was calculated and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and the post hoc Scheffe were used to analyze the data. The results of the subjects’ comprehension of coordinators are shown in Table 3-3:

Table 3-3: Subjects’ Comprehension of Coordinators (in means)

Group 1 Group 2 Group 3

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

0.50 0.509 0.70 0.466 0.70 0.466

Table 3-3 shows that Group 3 and Group 2 generally outperformed Group 1. The average score of correct responses by Group 3 and Group 2 was higher than that by Group 1. One-way ANOVA showed that the three groups did not perform significantly differently in the comprehension of coordinators (Coordinator: F (2, 42)=2.545, p=0.090).

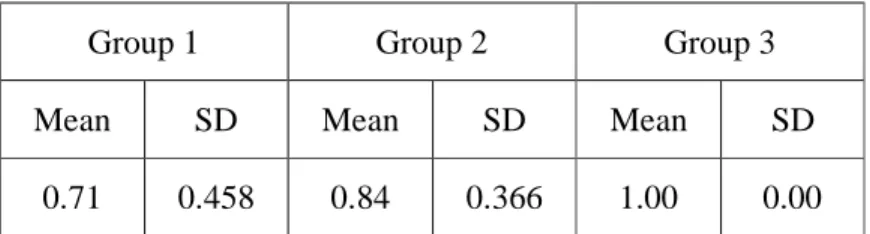

Table 3-4: Subjects’ Comprehension of Subordinators (in means)

Group 1 Group 2 Group 3

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

0.71 0.458 0.84 0.366 1.00 0.00

As for subordinators (Questions 3, 4 and 5), it remained the same that Group 3 outperformed Group 1. A developmental progress was found in answering questions 3 and 5, “Although Snoopy is sleeping, the little yellow bug is not” and “The dog kept running and he fainted away as soon as he saw the cat”. However, such tendency does not hold true in question 4 where we found some subjects failed to identify the picture correctly. All subjects of Group 1 and Group 3 could identify the correct picture with ease, but four subjects of Group 2 failed to do so. When we take a close look at these four subjects’ individual performance on the PI task, we found three of them got only 3 points (the highest point was 6) whereas the other one got 4 points10. Although some subjects in Group 2 seemed to perform poorly, we could only attribute such a result to individual differences.

Table 3-5 illustrates the comprehension of macro-syntactic conjunction among three age groups:

Table 3-5: Subjects’ Comprehension of Macro-syntactic Conjunctions (in means)

Group 1 Group 2 Group 3

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

0.47 0.516 0.60 0.507 0.80 0.414

Again, there was a gradual improvement on the comprehension of this type of conjunctions for those who were older (Macro-syntactic conjunction: F (2, 42)= 7.545, p=0. 174). One-way ANOVA showed that the three age groups did not perform differently in response to coordinators and macro-syntactic conjunctions (Coordinator:

F (2, 42) = 2.545, p=0.090; Macro-syntactic conjunction: F (2, 42) = 7.545, p=0. 174).

10 See Appendix F for each subject’s performance from the three age groups in the PI task.

However, they differed significantly in response to subordinators and in overall performance (Subordinator: F (2,42) = 6.786, p=0.003; Overall performance: F (2,42)

= 7.545; p=0.002).

One-way ANOVA showed that there was a significant difference between the three-year-olds and five-year-olds in terms of their comprehension of subordinators in Chinese. However, the difference between three-year-olds and four-year-olds was not significant (p=0.248), nor was it between four-year-olds and five-year-olds (p=0.153)11.

3.4.1.2 Subjects’ Performances on Semantic Conjunctions

In this section, we will discuss how our subjects comprehended the semantic conjunctions. Table 3-6 presents our subjects’ performance on the additive conjunctions.

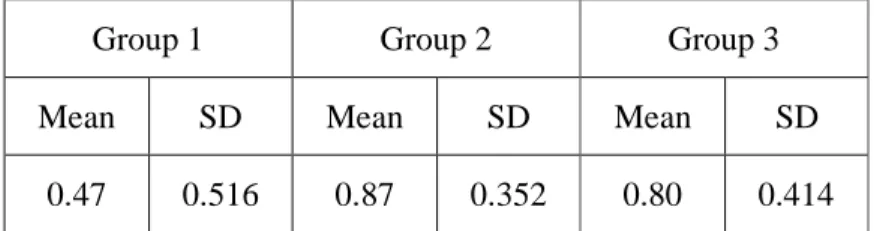

Table 3-6: Subjects’ Comprehension of Additive Conjunctions (in means)

Group 1 Group 2 Group 3

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

0.47 0.516 0.87 0.352 0.80 0.414

Evidently, Groups 2 and 3 performed well. However, half of the subjects in Group 1 failed to get the correct answer. We can see from Table 3-6 that some three-year-old subjects did not know that additive conjunctions could be used to combine NPs. One-way ANOVA showed that there was indeed a significant difference among the three groups (Additive: F (2, 42) =3.678, p=0.034).

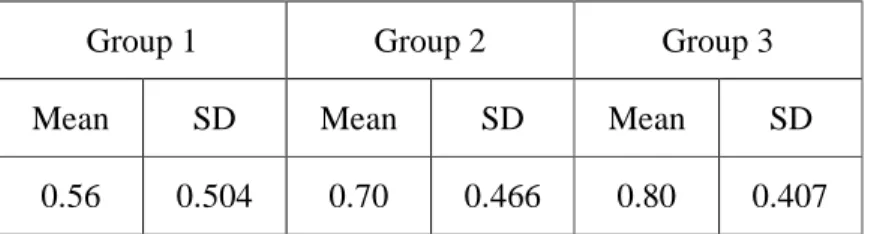

Table 3-7: Subjects’ Comprehension of Adversative Conjunctions (in means)

11 See Appendix G for one-way ANOVA table.

Group 1 Group 2 Group 3

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

0.56 0.504 0.70 0.466 0.80 0.407

In Table 3-7, we can see that the older subjects could generally comprehend the use of adversative conjunctions than the younger ones. After a close look at the test items in the two questions (Questions 2 and 3), we found that the subjects showed no significant difference in comprehending the use of buguo, but there was a significant difference in their use of suiran…keshi… For example, Question 2 asked the subjects’

use of adversative conjunction buguo, it was found that there was no performance difference between Group 1 and Group 2. However, for the performance in Question 3 which examined the subjects’ use of suiran… keshi…, Group 3 could comprehend this set of conjunctions and they outperformed Group 2 and Group 2 outperformed Group 1. One-way ANOVA showed that there was no significant difference among the three age groups (Adversative: F (2, 42) =1.824, p=0.174).

Table 3-8: Subjects’ Comprehension of Causal Conjunctions (in means)

Group 1 Group 2 Group 3

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

1.00 0 0.73 0.457 1.00 0

Similarly, there was a sharp difference among the three groups. All subjects in Group 1 and Group 3 could fully understand the set of conjunctions yinwei…suoyi….

Four subjects of Group 2 failed to answer the comprehension. The reason why only some subjects of Group 2 failed to identify the correct picture whereas the subjects of Group 1 and Group 3 could easily get the correct answer was out of our expectation.

One-way ANOVA showed that the difference among the three groups was significant (Causal: F (2, 42) =5.091, p=0.010).

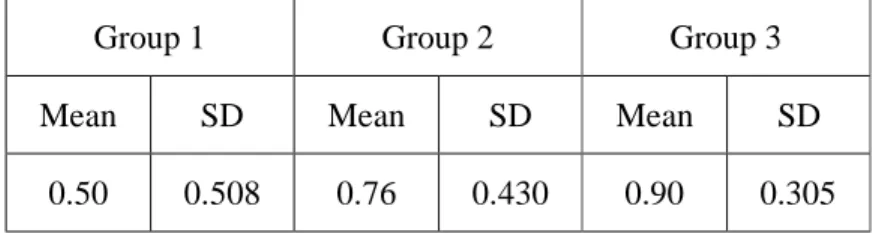

Table 3-9: Subjects’ Comprehension of Temporal Conjunctions (in means)

Group 1 Group 2 Group 3

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

0.50 0.508 0.76 0.430 0.90 0.305

As for temporal conjunctions, a group difference was found. The meaning of both temporal conjunctions at the sentence level and macro-syntactic levels were gradually mastered by those subjects who were older. The average mean scores of Questions 5 and 6 were 0.90, indicating that when the subjects reached age five, about 90% of them had already known the meaning of the temporal conjunctions. One-way ANOVA showed that there was a significant statistical difference among the three groups (Temporal: F (2, 42) =7.396, p=0.002). Once again, Group 3 outperformed than Groups 1 and 2.

Overall, one-way ANOVA indicated that the three age groups responded significantly differently to additive (p=0.034), causal (p=0.010), and temporal (p=0.002). The significant difference, however, was not found in their response to adversative conjunctions. Again, the tendency that the older subjects outperformed the younger subjects was obvious. The Scheffe post hoc further indicated that a significant difference existed in response to the “causal” conjunctions between Groups 1 and 2 (p=0.03) as well as between Groups 2 and 3 (p=0.03). In addition, there was a significant difference in response to the “temporal” conjunctions between Groups 1 and 3 (p=0.02).

3.4.2 The SR Task

The SR task, as mentioned earlier, is a production task. The amount of conjunctions used by the subjects was counted and analyzed further.

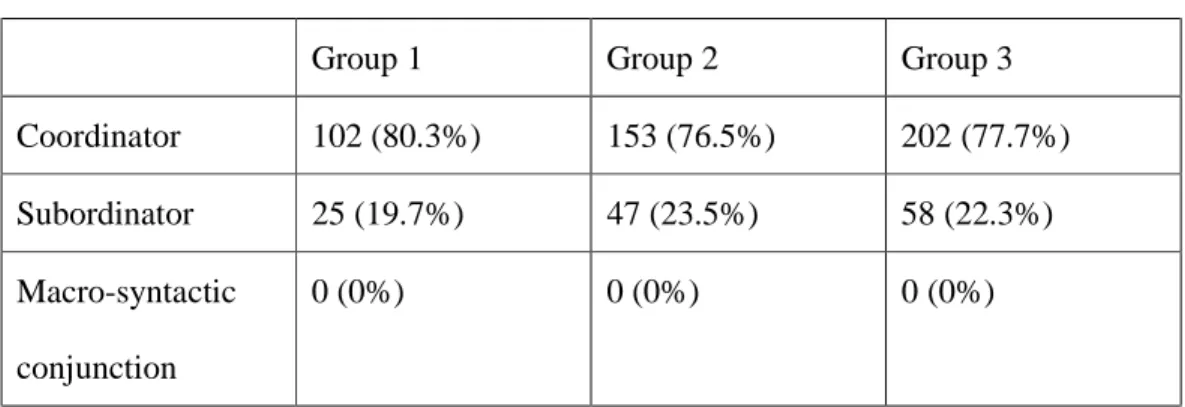

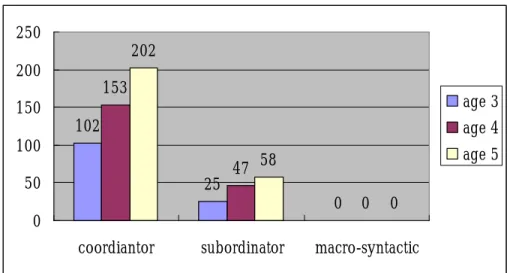

3.4.2.1 Subjects’ Performances on Syntactic Conjunctions

In this section, we will present the results (frequency counts) of the conjunctions that the subjects used in the SR task. We will first present the findings concerning the syntactic conjunctions and then the semantic ones. The frequency of syntactic conjunctions12 used by the subjects is shown in Table 3-10:

Table 3-10: Each Groups’ Use of the Syntactic Conjunctions (in frequency and percentages)

Group 1 Group 2 Group 3

Coordinator 102 (80.3%) 153 (76.5%) 202 (77.7%)

Subordinator 25 (19.7%) 47 (23.5%) 58 (22.3%)

Macro-syntactic conjunction

0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%)

In the SR task, it was found that ranhou was the most frequently produced conjunctions by the three-to five-year-old subjects. In the pilot study, similar results were also found. Since the events in the story were all temporally related, it was not surprising to find the high frequency of the occurrences of additive conjunctions ranhou to string various events in the story together. In the subsequent classification, if ranhou were evidently used to connect phrases or clauses of equivalent syntactic status, then it would be treated as coordinators. If ranhou functioned in the subjects’

utterances more like a subordinator, connecting clauses that are not equivalent, then its function in that particular context would be treated as subordinator. As is shown in Table 3-10, coordinators which were used to link two phrases or clauses of the same status were commonly observed in the subjects’ production throughout the three age groups. On the contrary, subordinators which were used to link linguistic units which

12 According to Crystal (1997), co-ordination refers to the process of result of linking linguistic units which are usually of equivalent syntactic status, e.g. a series of clauses, or phrases, or words. In this respect, it is usually distinguished from subordinate linkage, where the units are not equivalent. A wide range of subordinators in English includes although, since, because, while, after, etc.

are not equivalent were found to be less productive than coordinators which link linguistic units of equivalent syntactic status.

In Figure 3-1, it was found that coordinator was the highly frequently used compared with the other conjunctions.

102

25

0 153

47

0 202

58

0 0

50 100 150 200 250

coordiantor subordinator macro-syntactic

age 3 age 4 age 5

Figure 3-1: Frequency of the Syntactic Conjunctions in the SR Task

After we analyzed the frequency counts of the coordinator, we found that there was a high proportion of this type of additive conjunctions. However, Chi-square analysis indicated that the difference was not significant in the subjects’ use of the three syntactic conjunctions (p>0.05).

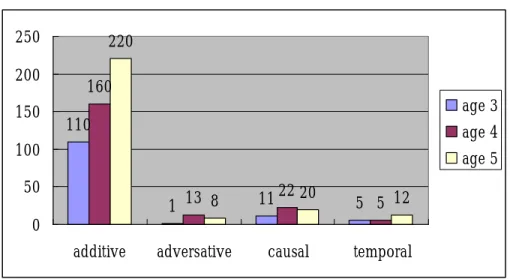

3.4.2.2 Subjects’ Performances on Semantic Conjunctions

In this section, we will focus on the four semantic types of conjunctions defined in Chapter Two and see which type(s) appears to be the frequently used one(s) by the subjects in the SR task.

As shown in Figure 3-2, the additive conjunctions were used the most frequently during their story-retelling.

110

1 11 5

160

13 22

5 220

8 20 12

0 50 100 150 200 250

additive adversative causal temporal

age 3 age 4 age 5

Figure 3-2: Frequency Counts of the Semantic Conjunctions in the SR Task

There were 110 occurrences of the additive conjunctions from the three-year-olds;

160 occurrences of the additive conjunctions from the four-year-olds and 220 occurrences of the additive conjunctions from the five-year-olds. The occurrences of the other types of conjunctions such as adversative, causal and temporal ones were comparatively low. The causal conjunctions were the second frequently used ones in the SR task (11 occurrences from the three-year-olds, 22 occurrences from the four-year-olds, and 20 occurrences from the five-year-olds). Despite the low frequency of the other types of conjunctions (adversative and temporal), the subjects’

uses of them were generally accurate. That is to say, the subjects as young as three-year-old had learned how to express additive, adversative, causal and temporal relationships with conjunctions. It was also found that only some of the subjects’

utterances included the use of causal conjunctions while some of the subjects did not.

Similarly, in Figure 3-2, the results of the Chi-square analysis turned out that there was no significant difference in the subjects’ use of the four types of semantic conjunctions (p>0.05):

Table 3-11: Each Groups’ Use of the Semantic Conjunctions (in frequency and percentages)

Group 1 Group 2 Group 3

Additive 110 (86.6%) 160 (80%) 220 (84.6%)

Adversative 1 (0.78%) 13 (6.5%) 8 (3.1%)

Causal 11 (8.7%) 22 (11%) 20 (7.7%)

Temporal 5 (3.9%) 5 (2.5%) 12 (4.6%)

As shown in Table 3-11, the temporal conjunctions were the most preferred ones in the SR task. Additionally, in the SR task, the Chi-square analysis indicated that all the subjects performed similarly in their use of the syntactic and semantic conjunctions (p>0.05)13.

3.5 Summary of Chapter Three

In this chapter, we have presented the subjects, the materials and the methodology as well as the results of the present study. The results obtained in both tasks are briefly summarized in Table 3-12:

Table 3-12: Summary of the Results of the Two Tasks Tasks

Properties

PI SR

Coordinator G3=G2>G1 77.9%

Subordinator G3>G2>G1 22.1%

Syntax

Macro-syntactic conjunction

G3>G2>G1 0%

Additive G2>G3>G1 83.5%

Adversative G3>G2>G1 3.7%

Causal G3=G1>G2 9%

Semantics

Temporal G3>G2>G1 3.7%

13 See Appendix H for Chi-square analysis table.

Generally speaking, in syntactic classification, the results showed that Group 3 did significantly better than Group 1 in response to almost all conjunctions (coordinators, subordinators and macro-syntactic conjunctions) in the PI task. In semantic classification, the results still showed that Group 3 did significantly better than Group 1 in response to almost all conjunctions (adversative, causal, and temporal), except for additive conjunctions (with Group 2 slightly outperformed Group 3) in the PI task. In addition, a significant difference was found in response to Causal conjunctions among the three age groups. Overall, in the PI task, there was a significant difference in response to the six test items among the three age groups (F (2, 42) = 7.545, p= 0.002).

In the SR task, however, such difference was not significant. Although the differences in the three age groups were not statistically significant, we found that the older subjects (i.e., Group 3) tended to use more conjunctions to connect clauses to make their story more coherent. However, Groups 1 and 2 used fewer conjunctions in the SR task. Based upon the results in Chapter Three, the issues of the acquisition of syntactic and semantic conjunctions, age differences, and task effects will be discussed in Chapter Four.