The role of the Universal Periodic Review in advancing human rights in

the administration of justice

March 2016

A report of the International Bar Association’s

Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI) United Nations Programme Supported by the IBAHRI Charitable Trust

Material contained in this report may be freely quoted or reprinted, provided credit is given to the International Bar Association

Acknowledgements

This report was written by Dr Helene Ramos Dos Santos, IBAHRI Senior Fellow Consultant.

The writing, development and publication of this report were overseen and supported by Shirley Pouget, Senior Programme Lawyer. IBAHRI Director Phillip Tahmindjis, Principal Programme Lawyer Alex Wilks and Programme Lawyers Chara de Lacey and Nadia Hardman have

collectively contributed to editing the report. The IBAHRI would also like to thank the following interns and research assistant for their assistance in compiling research data and sections of this report: Yannic Kortgen, Jaka Kukavica, Cecilia Barral Diego and Delphine Canneau. Finally, the IBAHRI would like to thank all individuals and stakeholders who consulted with the IBAHRI Senior

Fellow Consultant via telephone or face-to-face interviews and questionnaire.

Contents

List of Acronyms ... 1

About the IBAHRI United Nations Programme ... 3

Foreword ... 4

Executive Summary ... 6

Chapter One: Introduction ...11

1.1 The role of the Universal Periodic Review in advancing human rights in the administration of justice: definitions and context ... 12

1.2 Terms of reference ... 16

1.3 Research and consultation methodology ... 16

1.4 Scope and limitations of the report ... 17

1.5 Structure of the report ... 25

Chapter Two: The ‘Administration of Justice’ in the International Human Rights System ...27

2.1 The unity of the system, the diversity of mechanisms ... 28

2.2 The Universal Periodic Review: from commitment to compliance? .... 32

2.3 Conclusions of Chapter Two ... 39

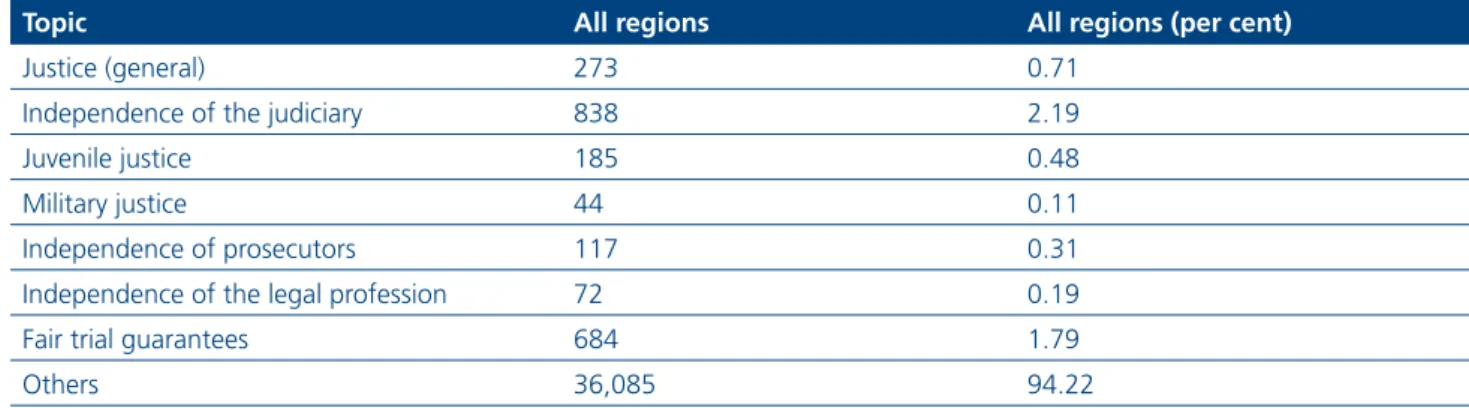

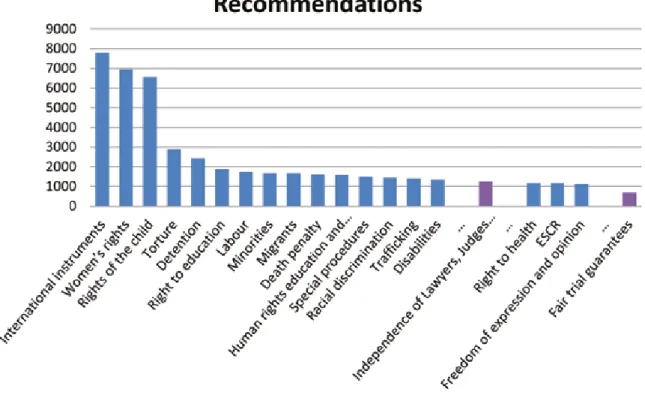

Chapter Three: The ‘Administration of Justice’ in the UPR Recommendations: Quantitative and Qualitative

Insights... 41

3.1 Methodology ... 42

3.2 Findings ... 43

3.3 Conclusions of Chapter Three ... 74

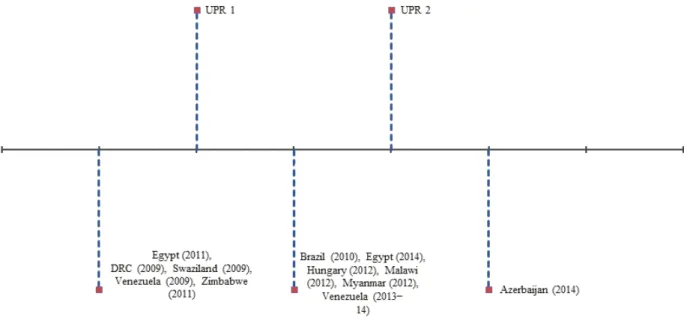

Chapter Four: Country Analyses ... 77

4.1 Methodology ... 78

4.2 Findings ... 80

4.3 Conclusions of Chapter Four ... 109

Chapter Five: Conclusions and Recommendations ... 113

5.1 To recommending states ... 118

5.2 To states under review ... 120

5.3 To lawyers and lawyers’ associations ... 121

5.4 To the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights ...122

Bibliography ... 123

List of Acronyms

BAA Bar Association of the Republic of Azerbaijan CTA call to action

EEG Eastern European Group

GRULAC Latin American and Caribbean Group (Group of Latin America and Caribbean Countries) HRC Human Rights Council

IBA International Bar Association

IBAHRI International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute ICCPR International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights ICJ International Commission of Jurists

LGBTI Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender/transsexual and Intersex LSM Law Society of Malawi

LSS Law Society of Swaziland LSZ Law Society of Zimbabwe

MDG(s) Millennium Development Goal(s) NJP National Justice Programme

OECD Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development ODA Official Development Assistance

OHCHR Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Rec Recommendation

SDG(s) Sustainable Development Goal(s) UDHR Universal Declaration on Human Rights

UN United Nations

UNCT United Nations Country Teams UPR Universal Periodic Review

WEOG Western European and Others Group WJP World Justice Project

ZWLA Zimbabwe Women Lawyers Association ZLHR Zimbabwe Lawyers for Human Rights

About the IBAHRI United Nations Programme

Established in 1947, the International Bar Association (IBA) is the world’s leading organisation of international legal practitioners, bar associations and law societies. The IBA influences the development of international law and shapes the future of the legal profession throughout the world. It has a membership of over 80,000 individual lawyers and 190 bar associations and law societies spanning all continents.

Created in 1995, the International Bar Association’s Human Rights Institute (IBAHRI) provides human rights training and technical assistance for legal practitioners and institutions, building their capacity to promote and protect human rights effectively under a just rule of law. A leading institution in international fact-finding, the IBAHRI produces expert reports with key recommendations,

delivering timely and reliable information on human rights and the legal profession. The IBAHRI supports lawyers and judges who are arbitrarily harassed, intimidated or arrested through advocacy and trial monitoring. A focus on pertinent human rights issues, including the abolition of the death penalty, poverty and LGBTI rights forms the basis of targeted capacity-building and advocacy projects.

Programme overview

On 20 November 2014, the IBAHRI launched its United Nations (UN) Programme, focused on UN recommendations relating to the independence of the judiciary and the legal profession. The programme comprises three complementary components:

1. Advocacy. To advocate for the advancement of human rights in the administration of justice, focusing on UN human rights mechanisms in Geneva.

2. Capacity-building. To train lawyers, judges and bar associations to engage with UN human rights mechanisms, on issues related to their professional independence.

3. Research and analysis. To inform state policies on, and implementation of, UN

recommendations relating to the independence of the judiciary and legal profession.

Programme rationale

Lawyers are at the forefront of the defence for the protection of human rights. Without an independent legal profession, victims of human rights violations are not able to exercise their right to redress. The effective implementation of UN recommendations relating to the independence of the judiciary and legal profession is therefore at the heart of the promotion and protection of human rights.

Lawyers, judges and bar associations have a vital role to play in ensuring their professional

independence, and UN human rights mechanisms provide effective and accessible tools to promote relevant policies and their implementation on the ground.

As part of the world’s leading organisation of international legal practitioners, bar associations and law societies, the IBAHRI is ideally placed to engage the global legal profession with such mechanisms and to advocate for the advancement of human rights and the independence of the legal profession.

Foreword

Through implementation of its varied recommendations, the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) has great potential in bringing about positive change in the human rights situation on the ground. Together with recommendations from other human rights mechanisms, it can create a framework of national engagement for follow-up and implementation purposes, can foster dialogue between the state and all stakeholders in that process and can lead to important advances in the field of human rights. This impact can equally be felt in the area of administration of justice, if the mechanism were to be used effectively to foster a dialogue between states and the legal community. The IBAHRI report usefully guides recommending states, states undergoing review and legal professionals towards that objective, with key reflections in order to make the best use of the potential of the UPR in advancing human rights in the field of administration of justice.

Such a thematic focus in reviewing the work carried out broadly under the umbrella of the UPR is immensely useful. It enables expert and targeted analysis and guidance, which can only lead to strengthened recommendations and better implementation. This is inevitably of great value to all states in such peer review processes.

The report highlights the crucial relevance of involving all relevant stakeholders, including those that have been less engaged to date, such as the judiciary, bar associations, lawyers and the broader legal community, in the UPR process for better assessments and implementation, and as a result, strengthened state engagement in the UPR. It reminds us all of the importance of continued training for lawyers and judges on international human rights law standards, and of the meaningful contribution that they can make not only to better adjudication in line with international standards, but also broadly to law reform in their respective countries.

No doubt recommendations are a key outcome of the UPR process, and their proper formulation is of paramount importance. This would include not only effective use of the appropriate

international standards in their elaboration, but also recommendations that address head-on the challenges that actors of the court system might face in protecting human rights. Formulations can run the gambit touching on the institutional human rights framework involving the court systems and the independence of the judiciary, to concrete fair trial considerations, all the way to substantive calls on effective protection of the rights through legislative reform and effective adjudication with equal access to all. Involving and engaging the legal community in the process can only strengthen the outcomes.

Through the analysis in this report, states are encouraged to reflect on ways in which such key considerations may better be reflected through specific and measurable recommendations that touch on both what the states under review should achieve, as well as on how such changes might best be pursued by involving legal professionals.

The report thus provides important insight on the need for more effective implementation of the standards concerned in the recommendations. It calls for a greater focus on assessing the impact on the realisation of human rights in the country and in particular in the field of

administration of justice, as well on the best means to carry out such an assessment. It highlights some positive evolving practices in the context of the UPR and the field of administration of justice, and further encourages all in this path. With this guidance, and strengthened dialogue and engagement of the broader legal community, the UPR mechanism will be better placed to meet its full potential of improving the human rights situation on the ground and, importantly, in the field of administration of justice.

Shahrzad Tadjbakhsh Chief, UPR Branch Human Rights Council and Special Procedures Division (HRCSPD), United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

Executive Summary

The international environment has evolved and old and new human rights mechanisms now face the challenge of complementing one another. At the same time, the renewed international agenda defined by the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals incorporates human rights, and ‘access to justice for all’ is a goal in itself under Goal 16.1 As a result, the work of international human rights mechanisms will be, even more than before, complementary to the monitoring undertaken by the United Nations (UN) development agencies.

In this context, the contribution of the Universal Periodic Review (UPR) could be unique. The UPR has indeed opened up the international human rights system to non-state actors in an unprecedented manner. It is as such a sui generis human rights mechanism, where the involvement of the primary stakeholders constitutes the best guarantee of impact on the ground.

This report addresses, at the level of the UPR, two interrelated issues, namely the involvement of legal professionals in UN human rights mechanisms and reference to legal professionals in international recommendations. The report advocates for the involvement of legal professionals at the UPR as a key condition in fostering the impact of the process on the administration of justice. The report identifies a number of challenges that need to be addressed for the UPR to realise its full potential.

Recommending states face major challenges, not least of giving necessary attention to legal professionals, in accordance with their role and the specific protection recognised for them in international law. The role of legal professionals in the protection of human rights, and their need for specific protection, were put as key priorities on the international human rights agenda three decades ago. While the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers has evidenced over 20 years the need for further compliance with the UN Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers, the UN Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary and the UN Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors (collectively, the ‘UN Basic Principles and Guidelines’), the UPR recommendations until now have barely mentioned the specific status and need for protection of legal professionals.

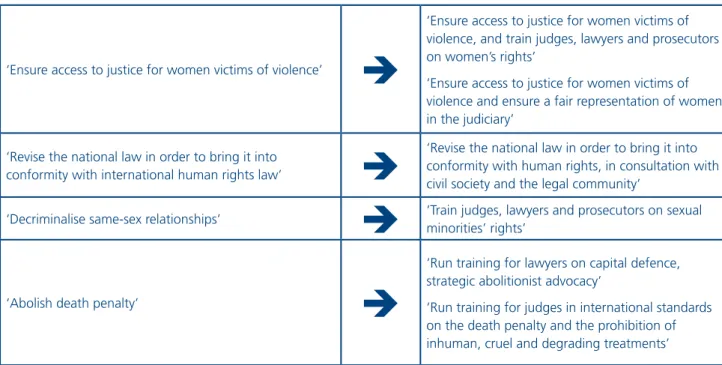

The main challenge facing recommending states is to draft specific and action-orientated recommendations that pinpoint specific shortcomings in the justice system, borrow the agreed international human rights language and build upon the current international human rights

framework. Only a few states have so far referred to the UN Basic Principles and Guidelines. Similarly, only a few states have echoed the recommendations and good practices identified by the Special Rapporteurs in the administration of justice. The rights to freedom of expression, assembly and association for legal professionals are key conditions for the independence of justice systems, but have almost never been addressed. Professional organisations of lawyers – bar associations or law societies – have rarely been mentioned, while they should be counted among the primary institutions of the country charged with the protection of human rights. These organisations should be entrusted with the role of ensuring the protection and education of lawyers in order to promote the rule

of law and an independent court system. The involvement of lawyers in law reform and the fight

1 Under Goal 16, states envision to ‘promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels’ as the backbone of national human rights systems.

against impunity has never been addressed, even though it could facilitate informed legal debates, sustainable democratic change and consistency within legal systems.

For the UPR to be counted among human rights mechanisms, UPR recommendations must be guided by the core human rights principles of non-discrimination, participation, access to information and accountability. This is true for all governance sectors, including the administration of justice. Thus the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers has recommended that the judiciary should be appointed in a participatory and transparent manner; it should be representative of the minorities in the country; and it should integrate a gender-based approach. Specific recommendations that depart from the international human rights framework lose their potential of impact. Specific recommendations can only trigger change if the legal and policy environment, where they are implemented, actively enables the enjoyment of human rights. A recommendation to train legal professionals in human rights, or appoint judges in an objective and transparent manner, will only be meaningful if the state is also being asked more broadly to comply with the UN Basic Principles and Guidelines and other relevant international human rights instruments.

The main challenge facing states under review is to develop a monitoring system that focuses on the impact of the measures they implement in the justice system on the realisation of human rights in the country, and to support a self-performance assessment process by the legal professions. Out of a sample of specific, action-orientated recommendations, the IBAHRI found no information on the implementation of almost 40 per cent of them, and that the monitoring most often found addressed the measures implemented, rather than the actual impact on the administration of justice or access to justice. The absence of implementation or reporting guidelines on the administration of justice is a problem that goes beyond the UPR. Notwithstanding the UN Rule of Law Indicators, there is currently no UN monitoring system measuring adherence to international standards on the independence of justice. The IBAHRI therefore encourages states to use the United Nations Rule of Law Indicators and set up a monitoring system based on the UN Basic Principles and Guidelines to monitor progress in realising access to justice for all, as targeted by Sustainable Development Goal 16 adopted by all UN Member States in September 2015.

Once international recommendations are lifted to the level of protection spelled out in

international standards as currently interpreted by the other human rights mechanisms, the UPR will be able to play its role and foster exchanges on good practice. In that respect, international organisations of legal professionals also share a responsibility in the development of good

practices. In 2009, Special Rapporteur Leandro Despouy encouraged the Human Rights Council (HRC) to ‘draw on the contributions and experience of national and international jurists’

organizations established to defend judicial independence’.2 Good practices in key areas such as training programmes, the protection of legal professionals and the fight against corruption within the justice system will be among the main issues to address in order to foster human rights in the administration of justice. Training material and education programmes are at the core of the activities of many international organisations of legal professionals and there are lessons to be learned from this wide experience. The IBAHRI will soon release a manual compiling current practice in the establishment and functioning of professional organisations

2 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2007) UN Doc A/

HRC/4/25, 2.

of lawyers. Further guidance is currently being developed, especially by the IBAHRI and the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), on judicial accountability and judicial integrity. The IBAHRI is committed to foster the involvement of lawyers in UN human rights mechanisms and in monitoring the independence of judges, lawyers and prosecutors at country level. It is also committed to fostering exchanges between lawyers’ organisations to encourage the development of good practices.

In light of the findings presented in this report, the IBAHRI makes the following recommendations with a view to improving the UPR mechanism and ensuring that relevant stakeholders and

appropriate standards inform that process and states’ recommendations.

To recommending states

1. When assessing a state’s human rights situation, pay specific attention to the information coming from lawyers’ associations.

2. Consider the separation of powers and the independence of legal professionals as priority issues to be addressed at the UPR as a necessary requisite for the protection of all human rights.

3. When making recommendations, refer to the UN Basic Principles and Guidelines and prior

recommendations and good practices in the administration of justice as identified by international human rights mechanisms, especially the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers.

4. Call for judges, prosecutors and lawyers to be recognised as subjects of specific protection measures to ensure that they carry out their professional duties without any external or internal interference.

5. Call for the administration of justice to be transparent, accessible to all (through the provision of legal aid where necessary), participatory and representative of the population it serves as a requirement to ensure access to justice by vulnerable groups.

6. Call for the state under review to allocate material and financial resources to the justice system, and ensure that the judiciary be given an active involvement in the preparation of its budget and enjoy autonomy in the allocation of its resources, while remaining accountable to the other branches of power for any misuse.

7. Call for a national independent, self-governed and self-regulatory bar association to be the primary institution charged with protecting the legal profession and fostering lawyers’ engagement in the protection of the rule of law and human rights.

8. Call for the legal community to receive continuous legal training on key human rights issues encountered in the country, following the recommendations of the Special Rapporteur in the 2010 annual report 14/26, and to be involved in law reform, especially in the revision of criminal legislation.

9. Call for the independence of prosecutors and the respect of international human rights standards in the fight against impunity and terrorism.

10. Cooperate with the state under review to implement the UPR recommendations.

To states under review

11. Involve the judiciary and professional organisations of lawyers in the implementation and monitoring of international human rights recommendations, including the UPR recommendations, especially relating to the administration of justice and legal reforms.

12. Use the Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, the Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers and the Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors as benchmarks for the implementation of the UPR recommendations relating to the administration of justice.

13. Refer to landmark cases of the highest judicial instances concerning human rights held in your country, while reporting to the UPR.

To lawyers and lawyers’ associations

14. Use the Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, the Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers and the Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors and the recommendations of the Special Rapporteur in order to monitor the independence of judges and lawyers in the country.

15. Monitor the independence of the judiciary and independence of lawyers and prosecutors in their country and take part in the UPR process.

16. Foster exchanges on human rights issues and related case law between national bar associations and members of the judiciary, especially between countries receiving similar recommendations at the UPR.

To the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights

17. Disseminate the United Nations Rule of Law Indicators in order to assist states and non-

governmental organisations (NGOs) in the monitoring of human rights in the administration of justice.

18. Foster the use of reporting guidelines at the UPR by states and NGOs.

Chapter One

Introduction

1.1 The role of the Universal Periodic Review in advancing human rights in the administration of justice: definitions and context

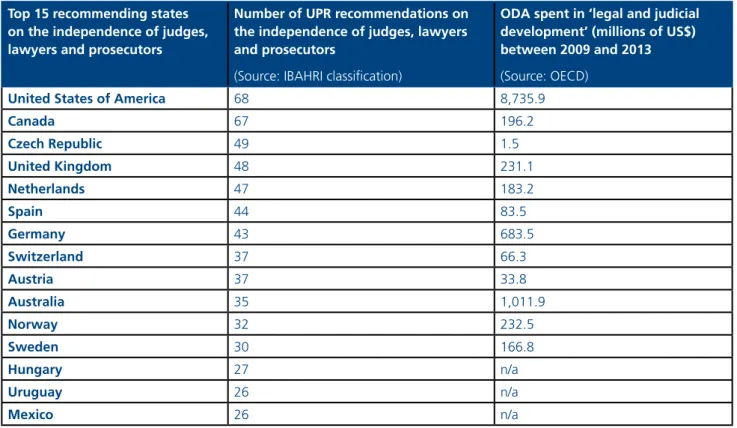

Between 2009 and 2013, bilateral development aid disbursed to foster legal and judicial developments amounted to more than US$12.8bn.3 This is one of the main budget lines in all sectors.4 In itself this constitutes the most tangible evidence of the importance attributed to the justice system’s role in backing any sustainable development. Paradoxically until 2015, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) – a series of time-bound targets adopted for 15 years by the United Nations in 2000 to fight poverty and foster development – retained a ‘narrow economic perspective of development’, excluding both human rights and justice.5

Looking at the interplay between access to justice and human rights protection, the emphasis of the role of the legal professionals6 is the result of a process that took place in the course of the 1980s. 7 The independence of lawyers then received a separate treatment next to the independence of the judiciary and the role of prosecutors, as key preconditions to the right to a fair trial. A number of guidelines were consecutively developed. The 1993 Vienna Conference8 placed the institutionalisation of human rights at international and national levels at the core of the Plan of Action states were then committing to. Legal professionals were put at the frontline of the protection of human rights. The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action recognised that

‘(t)he administration of justice, including law enforcement and prosecutorial agencies and, especially, an independent judiciary and legal profession in full conformity with applicable standards contained in international human rights instruments, are essential to the full and non-discriminatory realization of human rights and indispensable to the processes of democracy and sustainable development’

(emphasis added).9

Since then the international human rights system has continued to evolve. The Universal Periodic Review (UPR), created in 2007, provides a peer-to-peer review mechanism of states’ human rights performance. Complementary to expert bodies, such as treaty bodies and special procedures,

3 OECD Aid Data extracted from http://stats.oecd.org (Sector: ‘legal and judicial development’ (15130)).

4 OECD, Development assistance flows for governance and peace (OECD 2014), 8.

5 UNGA, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Gabriela Knaul (2014) UN Doc A/69/294, 2.

6 ‘Legal professionals’ or ‘legal professions’ in this report refers to ‘judges, lawyers and prosecutor’. ‘Lawyers’ or the

‘legal profession’ refers to ‘the body of lawyers qualified and licensed to practice law in a jurisdiction or before a tribunal, collectively, or any organised subset thereof, and who are subject to regulation by a legally constituted professional body or governmental authority’. (IBA, International Principles on Conduct for the Legal Profession (2011), 34. See also for a definition of lawyers, in the ‘Draft Universal Declaration on the Independence of Justice’

(‘Singhvi Declaration’), reproduced in ICJ, International principles on the independence and accountability of judges, lawyers and prosecutors. A practitioners guide (International Commission of Jurists, 2nd edn, 2007), 107: ‘a person qualified and authorized to plead and act on behalf of his clients, to engage in the practice of law and appear before the courts and to advise and represent his clients in legal matters.’

7 Phon Van Den Biesen, ‘Building on basic principles. Introductory observations’, Building on basic principles, 25 Years, Lawyers for Lawyers (Stichting NJCM-Boekerij 52, 15 April 2011), 2.

8 World Conference on Human Rights, 14–25 June 1993, Vienna, Austria.

9 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action (25 June 1993) A/CONF.157/23, adopted by the World Conference on Human Rights, para 27.

this intergovernmental mechanism has been designed to provide international human rights recommendations with political traction.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) – which were adopted in September 2015 and now define states’ international objectives for the next 15 years in the development arena – include access to justice under Goal 16. Under Goal 16 states envision to ‘promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels’. Among the targets of this goal are to ‘promote the rule of law at the national and international levels’ and ‘substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all its forms’.

These are absolutely crucial elements for creating the legal order that is a prerequisite for achieving all the other goals.10 For the first time, access to justice at country level will therefore be monitored at the international level by the United Nations (UN). Unlike their predecessors – the MDGs – the SDGs make reference to human rights. In light of this renewed international agenda, the UPR will constitute a unique complementary process where states, in an interactive dialogue, share progress realised to provide access to justice to all, in accordance with human rights principles.

It is in that context that this report aims to assess, on the one hand, the extent to which the UPR has, to date, assisted in advancing human rights in the administration of justice, and on the other, the level of participation of the legal community in that process. The IBAHRI believes that the legal community, as main guarantor of human rights on the ground, has a key role to play in the UPR in order to strengthen human rights in the administration of justice, and consecutively the realisation of all human rights.

Human rights in the administration of justice

The ‘administration of justice’ in the present report refers to the court system and its main actors, that is, judges, prosecutors and lawyers, in their mission to ensure the rule of law and protect human rights. The judiciary ensures that the conduct of the executive and administrative branches is consistent with previously enacted laws, with human rights and with the constitution. Prosecutors play a key role in protecting society from a culture of impunity, and function as gatekeepers to the judiciary. Finally, a strong, independent and competent legal profession is fundamental to guaranteeing citizens’ access to independent, skilled and confidential legal advice and protecting citizens’ rights and freedom under the rule of law.

As mentioned above, in the course of the 1980s, the independence of judges, lawyers and prosecutors received a separate treatment as key preconditions to the right to a fair trial, protected by Article 14 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR). Since then a number of standards elaborated on each of the principles. The building block of the independence of justice lies in the 1985 Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary,11 the 1990 Basic Principles

10 Hans Corell, ‘The Independence of the Legal Profession and Bar Associations: International Perspectives’, Presentation at the Conference ‘The Independence of the Legal Profession and Bar Associations: International Perspectives’ (26 July 2015, Tehran), available at www.havc.se/res/SelectedMaterial/20150726thebarandtheruleoflaw.

pdf. This and all other URLs last accessed 26 February 2016.

11 Adopted by the Seventh United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders held at Milan from 26 August to 6 September 1985 and endorsed by General Assembly Resolutions 40/32 of 29 November 1985 and 40/146 of 13 December 1985, available at www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/

IndependenceJudiciary.aspx.

on the Role of Lawyers,12 the 1990 Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors,13 the 1999 Standards of Professional Responsibility and Statement of the Essential Duties and Rights of Prosecutors and the 2002 Bangalore Principles for Judicial Conduct.

At the core of the independence of legal professionals is the recognition that judges, prosecutors and lawyers must carry out their professional duties without any external or internal interference and must be protected, in law and in practice, from attacks, harassment and persecution. The legal professionals (also referred as ‘the legal community’ thereafter) are protected as guarantors of the rule of law and human rights. They are in turn accountable to the people for enhancing human rights, and maintaining the highest level of integrity, in accordance with national and international law and ethical standards.

The institutionalisation and specific role and attributes of each legal profession trigger distinct rights and duties. As stated by Rapporteur Singhvi in 1985 and reiterated by Special Rapporteur Despouy in 2004,

‘[t]he duties of a juror and an assessor and those of a lawyer are quite different but their

independence equally implies freedom from interference by the executive or legislative or even by the judiciary as well as by others… Jurors and assessors, like judges, are required to be impartial as well as independent. A lawyer, however, is not expected to be impartial in the manner of a judge, juror or assessor, but he has to be free from external pressures and interference. His duty is to represent his clients and their cases and to defend their rights and legitimate interests, and in the performance of that duty, he has to be independent in order that litigants may have trust and confidence in lawyers representing them and lawyers as a class may have the capacity to withstand pressure and interference.’14

As to prosecutors, their relationship with the executive power can differ drastically from one system to another, insofar as they can be an integral part of that power, or completely independent from both the judiciary and executives branches. The Basic Principles and Guidelines purport however to establish an adequate system of checks and balances, notwithstanding differences among systems.

UN human rights protection mechanisms, namely the special procedures, treaty bodies and the UPR, play a key role in monitoring the implementation of human rights by states in the administration of justice. They provide states with guidance as to the implementation of these standards in order to enhance the independence of the judiciary and increase access to justice on the ground. The

12 Adopted by the Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders held at Havana, Cuba, from 27 August to 7 September 1990, available at www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/

RoleOfLawyers.aspx.

13 Adopted by the Eighth United Nations Congress on the Prevention of Crime and the Treatment of Offenders, Havana, Cuba, 27 August to 7 September 1990, available at www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/

RoleOfProsecutors.aspx.

14 ‘Study on the independence and impartiality of the judiciary, jurors, assessors and the independence of lawyers prepared by L.M. Singhvi Special Rapporteur’ (1985) UN Doc E/CN.4/Sub.2/1985/18 and Add.1-6, para 81;

UNCHR, ‘Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy’ (2003) UN Doc E/CN.4/2004/60, para 48.

effective implementation of UN recommendations relating to the independence of the judiciary and legal profession is therefore at the heart of the promotion and protection of human rights.

Universal Periodic Review

The Universal Periodic Review (UPR) was created in 200615 by the UN to ‘complement’16 pre-existing human rights mechanisms in order to improve state adherence to and encourage the fulfilment of human rights obligations through the implementation of recommendations. The UPR – currently undergoing its second cycle – is an intergovernmental process and the recommendations accepted by states on this occasion are tantamount to political commitments, that is, commitments taken by the executive as its initiative and as to its own action. It is as such a sui generis UN human rights mechanism with several characteristic attributes presented below.

First, the UPR operates as a peer-review assessment, driven by states, ensuring that all countries are reviewed, assessed and reported on an equal footing, notwithstanding political weight or any presumption of championing human rights. While the treaty bodies may only scrutinise human rights records of states that are parties to the relevant treaty, the UPR subjects every member of the UN to the universal review. Up until now, almost every state has presented a report and thereby recognised and reaffirmed the legitimacy of the UPR process. What is more, in some cases the UPR does not merely ‘complement’ other mechanisms, as stated in Resolution 5/1,17 but is the only dialogue on human rights the state is taking part in at the international level. Maintaining the willingness of UN Member States to cooperate with this mechanism is therefore a matter of utmost importance.

Then, the UPR constitutes the widest existing information-gathering process in the area of human rights. By involving a distinctly wide array of actors, the mechanism produces a large dataset of human rights compliance records of the involved states. It is framed by human rights information gathered by states, civil society, treaty bodies and UN specialised agencies. The information gathered is easily accessible to everyone through the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) website. It is the first time that information coming from UN human rights mechanisms and development agencies can be used in a consolidated manner.18 This unicity of the ‘interactive dialogue’19 constitutes a unique opportunity to discuss key human rights issue in all countries in a truly universal forum.

Finally, in sharp contrast to other human rights mechanisms, which mostly limit dialogue to between states and independent experts, the UPR provides human rights issues with unprecedented visibility.

Its outcome-orientated recommendations reach an extremely wide audience, including the highest levels of government. The process is transparent and debates are broadcasted, making inter-state dialogues subject to review by their citizens.

15 UNGA, ‘Human Rights Council’ (15 March 2006) UN Doc A/RES/60/251.

16 UNHRC, ‘Institution-building of the United Nations Human Rights Council’ (18 June 2007) UN Doc A/HRC/

RES/5/1, para 3(f).

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 UNGA, ‘Human Rights Council’ (15 March 2006) UN Doc A/RES/60/251, para e.

It is still too early to reach conclusions as to the full impact of the UPR mechanism on the global situation of human rights. The 2014 UPR Info report, Beyond promises, notes that there has been increased engagement of UPR stakeholders over the course of the first cycle, although engagement – particularly with reference to recommendations’ follow-up – is still lacking.20 The UPR has gained significant political traction, with recommendations reaching the line of ministers. The OHCHR, the Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie (OIF) and the Commonwealth Secretariat, among others, actively support states at different steps of the process. On the NGO front, much has been done to foster civil society participation and linkages between NGOs and states.

The UPR recommendations’ implementation, however, is the most critical and important step in the process, correlating directly to the ultimate goal of improving the human rights situation in every country. In this regard, the UPR Info report indicates that approximately 49 per cent of all commented first-cycle recommendations were not implemented more than two-and-a-half years after the first cycle (mid-term). With ‘justice’ representing one of the top five non-implemented categories,21 there is cause for alarm at the effectiveness and practicality of UPR recommendations as well as their impact on improving access to justice and strengthening the independence of legal systems across the globe.

1.2 Terms of reference

The terms of reference of the report are:

1. to examine the relevance of UPR recommendations in relation to the judiciary and the legal profession;

2. to assess the involvement of the legal profession in the UPR process and identify opportunities for the legal profession to be further involved; and

3. to publish the report indicating the findings of the research and making recommendations.

1.3 Research and consultation methodology

The methodology used in defining the terms of reference for the research project included a dual process of expert research and consultation. The Geneva-based IBAHRI Senior Fellow gathered, reviewed and analysed current reports and documentation related to the UPR and the protection of the independence of the judiciary by human rights protection mechanisms. She also engaged in consultation with approximately 30 civil society organisations, diplomatic missions and intergovernmental organisations present in Geneva.

From September 2014 to June 2015 a number of bilateral interviews were conducted with states’

representatives in Geneva. Among the consulted states were the 20 countries that made the most recommendations on the judiciary through the UPR.

20 UPR Info, Beyond promises: The impact of the UPR on the ground (UPR Info 2014), 5. Available at: www.upr-info.org/sites/

default/files/general-Doc.ument/pdf/2014_beyond_promises.pdf.

21 Ibid, 30–31.

The objective of the consultations was to understand, first, states’ agenda and strategy on the independence of the judiciary at the UN and, then, the importance given to the UPR to adapt the judiciary system.

A questionnaire was developed as a starting point for interviews and consultation meetings with states’ in-country contact points. Four out of the ten countries under scrutiny in the report provided information on the in-country UPR process. A number of in-country consultations were organised to obtain further information and inputs from lawyers and other stakeholders as to their involvement in the UPR and the impact of the IBAHRI recommendations, on the one hand, and recommendations of the UPR process, on the other hand.

1.4 Scope and limitations of the report

Thematic scope: key assessment areas and international standards in the administration of justice

The overriding principles of justice, namely the principles of independence of judges, lawyers and prosecutors, and principle of a fair trial, postulate ‘individual attributes as well as institutional conditions’,22 the absence of which leads to a ‘denial of justice and makes the credibility of the judicial process dubious’.23

The list of these individual attributes and institution conditions has been developed under the aegis of the UN Office on Drugs and Crime by means of the UN Basic Principles and Guidelines. The Human Rights Committee then clarified in its General Comment No 32 the content of Article 14 of the ICCPR on the right to a fair trial. The Human Rights Council in recent resolutions reassessed a number of these attributes and conditions.24 None of these instruments is legally binding per se. They however all contribute, with a lesser or greater authoritative force, to interpret states’ obligations under Article 14 of the ICCPR on the right to a fair trial. In addition, international organisations of legal professionals, like the International Bar Association,25 the International Association of Judges26 and the International Association of Prosecutors,27 have adopted professional standards, which reiterate and develop the standards spelt out at the level of the UN.28

22 UNCHR, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2003) UN Doc E/

CN.4/2004/60, para 65.

23 Ibid.

24 See in particular UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/HRC/11/41 (on the independence of judges); UNGA, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/64/181 (on the independence of lawyers); and UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Gabriela Knaul (2012) UN Doc A/HRC/20/19 (independence of prosecutors).

25 See in particular the IBA Standards for the Independence of the Legal Profession (1990) and the IBA International Principles on Conduct for the Legal Profession (2011).

26 International Association of Judges, the Universal Charter of the Judge (1999).

27 International Association of Prosecutors, Standards of professional responsibility and statement of the essential duties and rights of prosecutors (1999).

28 See also Judicial Group on Strengthening Judicial Integrity, The Bangalore Draft Code of Judicial Conduct (2001), as revised at the Round Table Meeting of Chief Justices held at the Peace Palace, The Hague, 25–26 November 2002.

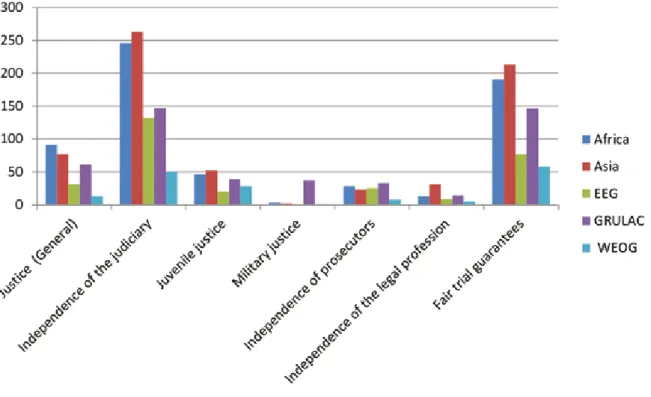

The Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers contributes to the unity of the human rights system by interpreting all these international instruments, in light of the recommendations of international and regional human rights mechanisms and country practice.29 In order to assess ways in which the UPR has so far advanced human rights in the administration of justice, the UPR recommendations were classified following the main list of attributes and conditions related to the independence of judges, lawyers and prosecutors respectively, and taking into account the terminology used in the UPR recommendations.

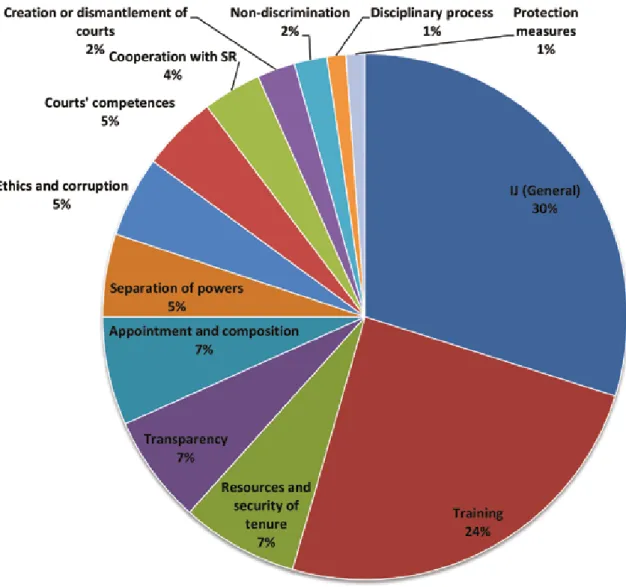

Regarding the independence of the judiciary, the recommendations addressing the independence, impartiality and/or efficiency of the judiciary system or the non-interference with the judicial process in general terms were classified as addressing the independence of the judiciary in general terms.

Recommendations calling for the separation of powers between the legislature, the executive and the judiciary branches were included in the analysis insofar as it constitutes ‘the bedrock upon which the requirement of judicial independence and impartiality are founded’.30

Specific recommendations were clustered around the following individual attributes and institutional conditions to the independence of judges: appointment process of judges and composition of the judiciary; the disciplinary process against judges; training of judges in human rights; security of tenure of judges; adequate financing, material and human resources of the judiciary; protection measures concerning judges; courts’ competences (including the issue of special courts and the oversight of the judiciary over administrative and security authorities) and transparency in the set-up and functioning of the court system. Some UPR recommendations also addressed the ‘fight against corruption’ within the judiciary and the adoption of ‘code of ethics’ for the judiciary, and these topics were added to the list.

Table 1 provides a list of topics on the independence of judges and the main international standards related thereto outlined in the Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary and the recommendations of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers.

Table 1: List of topics for recommendations addressing the independence of judges and lawyers

Key topics

(independence of judges)

Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary

With some of the main recommendations of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers (in italics)

Independence of judges (general principle)

‘The independence of the judiciary should be guaranteed by the State and enshrined in the Constitution or the law of the country. It is the duty of all governmental and other institutions to respect and observe the independence of the judiciary.’31

Impartiality of judges (general principle)

‘The judiciary shall decide matters before them impartially, on the basis of facts and in accordance with the law, without any restrictions […].’32

29 UNHRC, ‘Independence and impartiality of the judiciary, jurors and assessors, and the independence of lawyers’

(19 June 2013) UN Doc A/HRC/RES/23/6. UNHRC, ‘Independence and impartiality of the judiciary, jurors and assessors, and the independence of lawyers’ (2 July 2015) UN Doc A/HRC/RES/29/6.

30 UNCHR, ‘Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers’ (1995) UN Doc E/

CN4/1995/39, para 55.

31 Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, Principle 1.

32 Ibid, Principle 2.

Appointment process of judges and composition of judges

‘Persons selected for judicial offices shall be individuals of integrity and ability with appropriate training or qualifications in law. Any method of judicial selection shall safeguard against judicial appointments for improper motives. In the selection of judges, there shall be no discrimination against a person on the grounds of race, colour, sex, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or status […].’33 Member States should ‘consider establishing an independent body in charge of the selection of judges, which should have a plural and balanced composition, and avoid politicization by giving judges a substantial say’.34 ‘Special temporary measures can be adopted and implemented to achieve greater representation for women and ethnic minorities until fair balance has been achieved.’35

Disciplinary process against judges

‘Judges shall be subject to suspension or removal only for reasons of incapacity or behaviour that renders them unfit to discharge their duties.’36 ‘All disciplinary, suspension or removal of judges shall be determined in accordance with established standards of judicial conduct.’37 ‘Decisions in disciplinary, suspension or removal proceedings should be subject to an independent review.’38

‘Disciplinary measures to be adopted must be in proportionality to the gravity of the infraction committed by the judge.’39 ‘[T]he procedures before such a body must be in compliance with the due process and fair trial guarantees.’40

Training of judges in human rights

‘Persons selected for judicial offices shall be individuals of integrity and ability with appropriate training or qualifications in law […].’41

‘States should give priority to strengthening judicial systems, particularly through continuous education in international human rights law for judges, prosecutors, public defenders and lawyers.’42

Adequate financing, material and human resources

‘It is the duty of each Member State to provide adequate resources to enable the judiciary to properly perform its functions.’43

‘The judiciary [should] be given active involvement in the preparation of its budget.’ ‘The administration of funds allocated to the court system [should] be entrusted directly to the judiciary or an independent body responsible for the judiciary.’44 Judges should be remunerated ‘with due regard for the responsibilities and the nature of their office’.45 Security of tenure of judges ‘The term of office of judges, their independence, security, adequate remuneration,

conditions of service, pensions and the age of retirement shall be adequately secured by law.’46 ‘Judges, whether, appointed or elected shall have guaranteed tenure until a mandatory retirement age or the expiry of their term of office, where such exists.’47

‘Promotions of judges […] should be based on objective factors, in particular ability, integrity and experience.’48

33 Ibid, Principle 10.

34 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/

HRC/11/41, para 97.

35 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/

HRC/11/41, para 34.

36 Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, Principle 18.

37 Ibid, Principle 19.

38 Ibid, Principle 20.

39 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/

HRC/11/41, para 58.

40 Ibid, para 61.

41 Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, Principle 10.

42 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Gabriela Knaul (2010) UN Doc A/

HRC/14/26, para 99(e).

43 Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, Principle 7.

44 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/

HRC/11/41, para 101.

45 Ibid, para 75.

46 Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, Principle 11.

47 Ibid, Principle 12.

48 Ibid, Principle 13.

49 Ibid, Principle 8.

50 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/

HRC/11/41, para 102.

51 Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, Principle 2.

52 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/

HRC/11/41, para 51.

53 Basic Principles on the Independence of the Judiciary, Principle 3.

54 Ibid, Principle 5.

55 Ibid, Principle 4.

56 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/

HRC/11/41, para 97.

57 Ibid.

Fundamental freedoms of judges

‘In accordance with the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, members of the judiciary are like other citizens entitled to freedom of expression, belief, association or assembly;

provided, however, that in exercising such rights, judges shall always conduct themselves in such a manner as to preserve the dignity of their office and the impartiality and independence of the judiciary.’49

‘The establishment of a judges’ association [should] be supported by Member States on account of its importance as guarantor of an independent judiciary.’50

Protection measures concerning judges

States shall put in place the necessary safeguards to ensure that judges can fulfil their mission and ‘decide matters before them impartially on the basis of facts and in accordance with the law, without any restrictions, improper influences, inducements, pressures, threats or interferences, direct or indirect, from any quarter of for any reason’.51

‘Allegation of improper interference [should] be inquired be independent and impartial investigations in a thorough and prompt manner.’52

Courts’ competences ‘The judiciary shall have jurisdiction over all issues of a judicial nature and shall have exclusive authority to decide whether an issue submitted for its decision is within its competence as defined by law.’53 ‘Everyone shall have the right to be tried by ordinary courts or tribunals using established legal procedures. Tribunals that do not use the duly established procedures of the legal process shall not be created to displace the jurisdiction of ordinary tribunals.’54 There shall be no interference with the judicial process, other than judicial review.55 Transparency in the set-up

and function of the court system

‘Selection and appointment procedures [should] be transparent and public access to relevant records be ensured.’56 ‘Decisions related to disciplinary measures against judges should be made public.’57

Recommendations addressing the military or juvenile justice systems were respectively compiled under the tag ‘military justice’ and ‘juvenile justice’. Most of the recommendations addressing military justice revolve around cases of civilians and human right cases brought to military courts, or judges appointed by the military. The issues addressed under ‘juvenile justice’ cover a wide spectrum of issues, from specific criminal sanctions to specific courts and detention conditions.

The recommendations addressing the independence of prosecutors were tagged using the list of topics in Table 2.

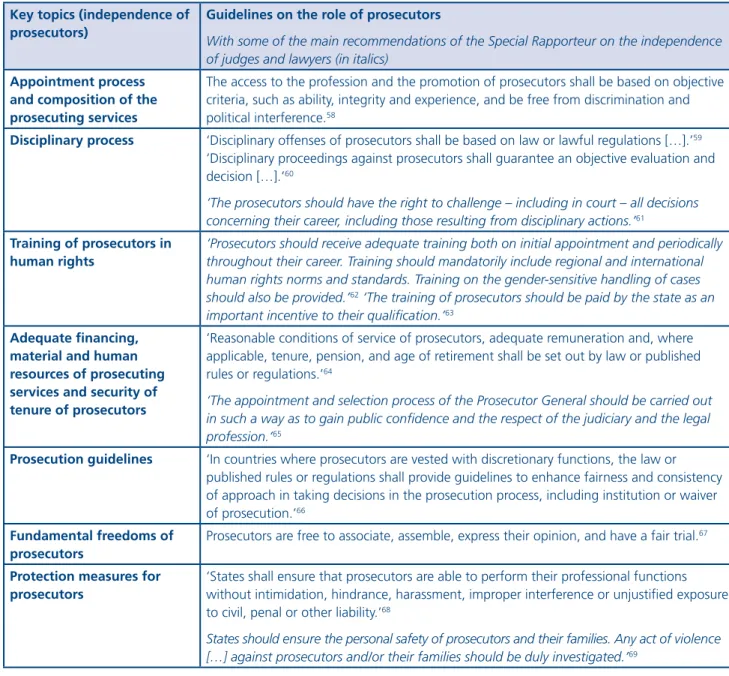

Table 2: List of topics for recommendations addressing independence of prosecutors

Key topics (independence of prosecutors)

Guidelines on the role of prosecutors

With some of the main recommendations of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers (in italics)

Appointment process and composition of the prosecuting services

The access to the profession and the promotion of prosecutors shall be based on objective criteria, such as ability, integrity and experience, and be free from discrimination and political interference.58

Disciplinary process ‘Disciplinary offenses of prosecutors shall be based on law or lawful regulations […].’59

‘Disciplinary proceedings against prosecutors shall guarantee an objective evaluation and decision […].’60

‘The prosecutors should have the right to challenge – including in court – all decisions concerning their career, including those resulting from disciplinary actions.’61

Training of prosecutors in human rights

‘Prosecutors should receive adequate training both on initial appointment and periodically throughout their career. Training should mandatorily include regional and international human rights norms and standards. Training on the gender-sensitive handling of cases should also be provided.’62 ‘The training of prosecutors should be paid by the state as an important incentive to their qualification.’63

Adequate financing, material and human resources of prosecuting services and security of tenure of prosecutors

‘Reasonable conditions of service of prosecutors, adequate remuneration and, where applicable, tenure, pension, and age of retirement shall be set out by law or published rules or regulations.’64

‘The appointment and selection process of the Prosecutor General should be carried out in such a way as to gain public confidence and the respect of the judiciary and the legal profession.’65

Prosecution guidelines ‘In countries where prosecutors are vested with discretionary functions, the law or published rules or regulations shall provide guidelines to enhance fairness and consistency of approach in taking decisions in the prosecution process, including institution or waiver of prosecution.’66

Fundamental freedoms of prosecutors

Prosecutors are free to associate, assemble, express their opinion, and have a fair trial.67

Protection measures for prosecutors

‘States shall ensure that prosecutors are able to perform their professional functions without intimidation, hindrance, harassment, improper interference or unjustified exposure to civil, penal or other liability.’68

States should ensure the personal safety of prosecutors and their families. Any act of violence […] against prosecutors and/or their families should be duly investigated.’69

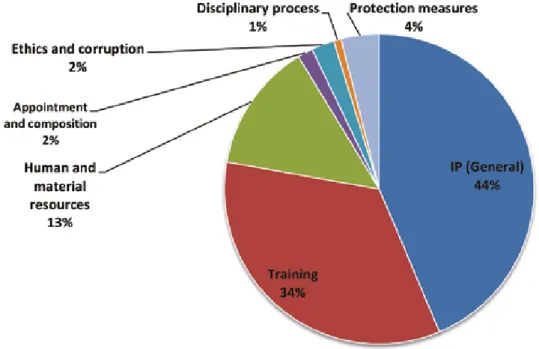

Similarly, the recommendations addressing the independence of lawyers were tagged using the list of issues in Table 3.

58 Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors, Guidelines 1–2 and 7.

59 Ibid, Guideline 21.

60 Ibid, Guideline 22.

61 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Gabriela Knaul (2012) UN Doc A/

HRC/20/19, para 114.

62 Ibid, para 124.

63 Ibid, para 126.

64 Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors, Guideline 6.

65 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Gabriela Knaul (2012) UN Doc A/

HRC/20/19 (Independence of prosecutors), para 109.

66 Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors, Guideline 17.

67 Ibid, Guidelines 21–22. See also UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Gabriela Knaul (2012) UN Doc A/HRC/20/19, para 81.

68 Guidelines on the Role of Prosecutors, Guideline 4.

69 UNHRC, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Gabriela Knaul (2012) UN Doc A/

HRC/20/19, para 118.

70 UNGA, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/64/181, para 105(c).

71 Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers, Principle 10.

72 UNCHR, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/

HRC/64/181, para 105(c).

73 Ibid, para 105(f).

74 Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers, Principle 11.

75 UNGA, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/64/181, para 112(a).

76 Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers, Principle 28.

77 Ibid, Principle 9.

78 UNGA, Report of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers, Leandro Despouy (2009) UN Doc A/64/181, para 112(d).

Table 3: List of topics for recommendations addressing independence of lawyers

Key topics

(independence of the legal profession)

Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers

With some of the main recommendations of the Special Rapporteur on the independence of judges and lawyers (in italics)

Independence of the legal profession (General principle)

‘Legislation regulating the role and activities of lawyers and the legal profession [should]

be developed, adopted and implemented in accordance with international standards;

such legislation should enhance the independence, self-regulation and integrity of the legal profession; in the process leading to the legislation’s adoption, the legal profession should be effectively consulted at all relevant stages of the legislation process.’70 Access to the legal profession ‘Governments, professional associations of lawyers and educational institutions shall

ensure that there is no discrimination against a person with respect to entry into or continued practice within the legal profession on the grounds of race, colour, sex, ethnic origin, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth, economic or other status, except that a requirement, that a lawyer must be a national of the country concerned, shall not be considered discriminatory.’71

‘In those Member States where the admission to the legal profession is conducted or controlled by the authorities, such responsibility should be gradually transferred to the legal profession itself within a determined time frame.’72 ‘In those Member States where there is a re-licensing or re-registration requirement for lawyers to continue practicing, that scheme be discontinued.’73

Composition of the legal profession

‘In countries where there exist groups, communities or regions whose needs for legal services are not met, particularly where such groups have distinct cultures, traditions or languages or have been the victims of past discrimination, Governments, professional associations of lawyers and educational institutions should take special measures to provide opportunities for candidates from these groups to enter the legal profession and should ensure that they receive training appropriate to the needs of their groups.’74

‘Lawyers’ associations strive to ensure a pluralistic membership of their executive bodies in order to prevent political or any other third-party interference.’75

Disciplinary process of lawyers ‘Disciplinary proceedings against lawyers shall be brought before an impartial disciplinary committee established by the legal profession, before an independent statutory authority, or before a court, and shall be subject to an independent judicial review.’76

Training of lawyers in human rights

‘Governments, professional associations of lawyers and educational institutions shall ensure that lawyers have appropriate education and training and be made aware of the ideals and ethical duties of the lawyer and of human rights and fundamental freedoms recognized by national and international law.’77

‘Legal professions should adopt a uniform and mandatory scheme of continuing legal education for lawyers, which should also include training on ethical rules, rule of law issues and international and human rights standards, including the Basic Principles on the Role of Lawyers.’78