The Prospect of Learning English via Mobile Phones for Junior High School Students in Taiwan

全文

(2) (Prensky 2005). Coincidentally, one of the most distinct advantages of mobile phones is their portability, which enables them to provide the users with timely assistance when desired. If English lessons or practices can be properly incorporated into students’ daily use of their mobile phone, taking advantage of the device that they are most familiar with, it would be possible to increase their exposure to English even when they are not at school. However, it seems that mobile phones have so far not given rise to an equal amount of application in language education, let alone that literature specifically dedicated to this potential use of mobile phones in the curriculum is still rare. In Asia, up until now only a handful of studies had been done regarding the effects of applying mobile phones in language instruction, and most of them were targeting university students in Japan. As for Taiwan, so far there has been only a little research regarding incorporating the use of SMS (short message service) text messages into vocabulary learning, and this was administered in the context of a vocational high school. However, concerning the use of mobile phones to facilitate students’ English learning at junior high school level, the potential remains unexplored. Take one of the most common functions of today’s handsets, Mp3, for example—it could serve as a Walkman to provide learners with audio input to the target language. Also, bite-size lessons could be delivered via mobile Internet or wireless transmission, whereas practices and quizzes could be designed in the form of Java games. Furthermore, interacting with and receiving instant feedback from the teacher through online conferencing is now made possible by the 3G service. On the other hand, having been constantly marketed as ‘cool’ and ‘attractive’ electronic products (Goggin 2006: 41), especially for younger generations, mobile phones could themselves be potentially good incentives for language learning. Learning English via mobile phones is apparently a brand new concept in the world, but in Taiwan is the digital environment favourable for mobile phone learning at junior high school level? Before further experiments concerning the use of mobile phones to enhance English learning can be administered, it is necessary to have a preliminary study about students’ current daily use of mobile phones a their language learning experiences. By investigating current conditions, this research is aimed at getting a picture of possible trends and prospects for local mobile language education.. 2 LITERATURE REVIEW 2.1 M-Learning Compared to PCs, the traditionally dominating learning facilities in the domain of education, what makes mobile phones stand out as potentially powerful learning tools in the future is their mobility and portability, which no longer restricts learning 189.

(3) to fixed classrooms or stationary environments. Featuring the capability to support ‘learning on the move’ (Kukulska-Hulme et al. 2007:.53), acquiring knowledge via mobile phones can be seen as one of the most evident embodiments of the concept of m-learning (or mobile learning). Although for learners, traditional printed media such as books can offer similar qualities of ‘learning on the move’ and therefore arguably to a certain extent can also be seen as a form of m-learning, it is undoubtedly the new potential brought by mobile technology that has really attracted researchers’ attention in recent years. For this reason, m-learning is usually defined as learning with electronic devices that are small enough for users to carry around (O’Malley et al. 2003: 6; Kukulska-Hulme 2005a: 1). The latest definition of m-learning is made by Sharples et al., who conclude that m-learning encompasses not only the mobility of technology but also the mobility in physical space, conceptual space and social space; it also enables ‘learning dispersed over time’ (2009: 235).. 2.2 Mobile Phones—Potentially Powerful Tools in M-Learning In addition to being small and lightweight, meaning greater portability, another advantage that makes mobile phones potentially good learning tools is that they are ‘either “always on” or can be turned on instantly and can consequently respond quickly to learners’ impulses’, which makes learning closer to ‘anytime anywhere’ (Kukulska-Hulme and Traxler 2005: 31). Prensky (2005) lists various activities that can make good use of the existing functions of the handsets, including: voice only, short text messages (SMS), graphic displays, downloadable programs, Internet browsers, cameras and video clips and global positioning systems (GPS). As for learners, it is claimed that mobile technology can make learning more ubiquitous, situated, personal and more learner-centred (Naismith et al. 2004: 36; Kukulska-Hulme and Traxler 2005: 42). Other research shows that when using mobile phones as tools, learners tend to be more sustainable in learning and make better use of their fragmentary spare time, compared to those using computers. In other words, instead of having to ‘make time to use for study’, they ‘make use of the time for study’ (Morita 2003).. 2.3 MALL, SLA Theories and Approaches Probably owing to the fact that MALL (Mobile Assisted Language Learning) is a rather new concept, only until recent years did we begin to see a little more theory-based discussion and terms employed to associate SLA (Second Language Acquisition) with the idea of ‘language learning with mobile devices’. Nah et al. mention that comprehensible input and output as well as negotiation of meaning can be made via MALL activities such as SMS and email exchanging, Internet searching, and through having dialogue with peers or the teacher on the mobile phones (2008: 4). 190.

(4) On the other hand, it is also claimed that collaborative and learner-centred learning can be achieved through the handsets, just like these learning approaches are applicable on computers in the CALL (Computer Assisted Language Learning) activities (Savill-Smith and Kent in ibid; Naismith et al. 2004). One of the most distinctive qualities of MALL is that with the portability and mobility of the mobile devices, learning can be more situated (ibid). That is to say, with mobile technology, learning can occur beyond classrooms and language learners can benefit greatly from having the opportunities to interact with the authentic context surrounding them.. 2.4 The Use of Mobile Phones for Language Learning in Asia In Asia, where English is taught as a foreign language in most countries, Japan was the first to initiate relevant attempts to incorporate the use of handsets into language learning. In late 2002, a commercial English learning system known as ‘Pocket Eijiro’ was made specifically for mobile phone users, sending short English lessons to the subscribers. It was claimed that within just a month the system had already attracted over ten thousand users and received very positive feedback (Morita 2003). Thornton and Houser, on the other hand, conducted a research concerning the use of mobile emails as well as video and web materials in English education at a university. The results showed that mobile devices such as mobile phones and PDAs were rather effective in terms of the ways they helped students to learn new vocabulary and idioms. The advantage of convenience brought by the handsets during language learning was also highly valued by the learners (Thornton and Houser 2005). In recent years, Stockwell (2007; 2008) designed an ‘intelligent tutor system’ that could adapt the difficulty of the content delivered according to the users’ performance via their handsets. In South Korea, an experiment containing Internet-based listening tasks was designed for undergraduate students to access the WAP (Wireless Application Protocol) sites via their mobile phones. According to the findings of this research, the majority of the students felt that using mobile phones did make English learning more convenient and interactive. They also thought that those handhelds helped to promote student-centred and collaborative learning (Nah et al. 2008). In Taiwan, an experiment was administered in a vocational high school using SMS as a means of delivering vocabulary. As revealed by the results, overall the students not only showed positive attitudes towards this new way of learning but also achieved higher grades in the post test (Lu 2008). As for China, the BBC’s World Service section also had a project which provided English instruction in the form of SMS together with radio broadcasting and the Internet, which was aimed at those who were too busy to sit down and learn English (Godwin-Jones 2005: 18). Lately, an experiment was made using mobile phones to broadcast live classroom teaching to create a blended learning 191.

(5) English classroom. The results indicated that the students became not only more engaged in language learning but also ‘intellectually and emotionally involved’ during the learning process (Wang et al. 2009).. 2.5 Challenging Issues Faced—small screens, miniature keypads, cost, psychological and environmental factors From the results of previous research it appears that most of the learners have positive attitudes towards the concept of having mobile phones become learning tools that could help them in certain ways during the process of language learning. However, many of the subjects in the experiments did mention that the miniature screens were rather problematic when they had to read for a longer period of time or tried to input words, which made their learning experiences less enjoyable (Thornton and Houser 2002: 231; Wang and Higgins 2006: 6; Stockwell 2008: 266). Likewise, an experiment was made to test users’ satisfaction level when using mobile phone keypads and the result confirms that there is a counter-correlation between users’ satisfaction with the keypads and their thumb lengths as well as circumferences (Balakrishnan and Paul 2008). In addition, according to Wang and Higgins’ (2006: 7) research, users’ average input speed with keypads is less than 1/10 that of their speed using computer keyboards. It seems that when it comes to input efficiency, handsets would always be outperformed by computers. Also, some researchers found that daily usage of handsets does not necessarily link to users’ acceptance of mobile technology being applied for educational purposes (Dias 2002; Thornton and Houser 2005: 221; Stockwell 2008), while others discovered that the potential charge caused by increased usage of mobile services was also seen by the users as another disincentive that prevent them from perceiving handsets as learning tools (Kiernan and Aizawa 2004: 74; Stockwell 2007: 378). On the other hand, rather than ideally making learning more situated and authentic—as mobile learning is claimed to do—it was also discovered that in real life situations when learning becomes mobile, the surrounding environment may sometimes be more interruptive than helpful for language learning (Wang and Higgins 2007: 378). From the above literature we have seen both the potential and the limitations of mobile phones as learning tools. It seems that if we want to know whether using mobile phones to facilitate language learning is applicable in a certain context, the condition of hardware, users’ own experiences and attitudes, and other practical issues should all be considered. In order to find out what junior high school students in Taiwan think about learning English via mobile phones as well as to get a picture of whether Taiwan’s current digital environment is ready for the above new concept, this study identifies the following questions: 192.

(6) 1. 2. 3. 4.. What are junior high school students’ experiences of mobile phones? What are junior high school students’ experiences of learning English? What are their attitudes towards using mobile phones for English learning? How do their experiences of learning English in general correlate with their attitudes towards learning English with mobile phones? 5. How does their use of mobile phones in general correlate with their attitudes towards learning English with mobile phones? Prior to the administration of the investigation regarding the above questions, a preliminary hypothesis was made that students who like English more and those who like to use their mobile phones more would have more positive attitudes towards this technology being used as a learning tool.. 3 RESEARCH METHODS 3.1 Context Around three years ago, the government of Taiwan decided to advance education in English from fifth grade to as early as first grade. Although students had begun to learn English as a foreign language at the elementary level, English language classes were mainly focused on speaking and listening, which were aimed at bringing out students’ interest towards this language. From seventh grade onwards, English learning became more serious, and with the text and grammar in the textbooks becoming more difficult, reading and writing skills came to be valued more. Also, students are required to memorise vocabulary of a more advanced level and familiarise themselves with more complicated sentence structures. Most of them will take the upcoming BCTEST (Basic Competence Test for Junior High School Students) when they graduate from ninth grade. The three years in junior high schools is a crucial period of time when students gain basic language skills for future development.. 3.2 Participants The members of the target group of this research were from six classes of seventh and eighth grade students in two Taiwanese public schools, Chung Cheng Junior High School in Pintung City and Municipal Tu Cheng High School in Tainan City in the year 2009. The age of the target group ranges from twelve to sixteen years old. The average class size is about 30 to 35 students, with 6 hours of English classes each week. Unlike some private schools, where bilingual education is a feature, usually in public schools like these two, English classes are the only occasion that students actually have the opportunity to speak English. In other classes as well as in daily life, they speak their mother tongue—mostly Mandarin Chinese.. 193.

(7) 3.3 The Questionnaire To find out whether there is a correlation between users’ attitudes towards mobile phones being learning tools and their experiences in learning English as well as using these handhelds, questions contained in the questionnaire were divided into three parts, in which students’ experiences of learning English and mobile phone usage were surveyed in the first two sections before questions concerning their attitudes towards the concept of using mobile phones as tools for English learning were asked in the third part (see appendix). Because this research is also about investigating the current status of ownership of mobile phones in the two junior high schools, all of the students were asked whether or not they owned a handset. Question 1 in section 1 was to investigate students’ fondness for this language, and the six subdivisions of question 2 were designed to analyse students’ motivation for learning English, among which 2A through 2C were more extrinsic factors whilst 2D through 2F were more intrinsic. The second part was to investigate students’ overall usage of their mobile phones as well as their behavioural patterns when using these handsets. In other words, how much they liked using their handsets and how often English was used when they were using their handsets were all included as parts of the interests of this study. Based on the recordings in question 5, a clear picture could be drawn in terms of the sophistication of the mainstream mobile phones among junior high school students. Also, since in the previous research SMS and Internet were the two most exploited functions of handsets in terms of means of delivering learning materials, questions concerning students’ usage of the above two services were included in this section. Section three of the questionnaire was dedicated to query the students’ attitudes towards the prospect of learning English through these handhelds in the future. Based upon the issues brought up in the preceding literature (Stockwell 2008), advantages such as mobility and barriers such as cost and technical factors that could potentially influence users’ willingness to try this new way of learning were incorporated into the design of the questionnaire. Question 16, on the other hand, was intended to find out whether pressure from others would play a part in users’ decisions if it was assumed that they were provided the opportunities to give it a try. The open-ended question at the very end was reserved to offer room for other thoughts in terms of students’ expectations for this newly emerged way of learning that is yet to be further developed and explored.. 3.4 Data Collection Based on the suggestion of Dörnyei (2003), before questionnaires were formally distributed to the target group, a small scale pilot test was administered in advance to a group of five people including ELT major and non-ELT major students. Some 194.

(8) adjustments were made according to the feedback gained from the pilot survey, including replacing some items with others as well as the ways certain questions were asked or presented, in order to ensure that questions asked were both academically accurate and understandable to those who had no relevant background knowledge. The actual administration of the survey was made at the beginning of a regular English class during term time and took around ten minutes to complete. Questionnaires distributed were collected immediately after the students had finished filling in their responses.. 4 RESULTS Out of the 240 questionnaires given out, 205 of them were successfully retrieved, and 184 of which were completed. The statistics of this study were calculated based on these finished questionnaires. On the other hand, the value of the results of questions 8 to 18 had excluded students who did not have mobile phones. Likewise, questions 16 to 18 will only record the data of those who had used their mobile phone to access the Internet (see appendix).. 4.1 Students’ Profile According to the data collected, there were 103 female and 81 male students involved in this survey, representing 56% and 44% of the total participants respectively (see figure 1). Among the six participating classes, only one was of seventh grade. Consequently, the share of the seventh grade students investigated in this research was less than 15% (see figure 2). With regard to the subjects’ age variety, all of the students surveyed were between twelve and sixteen years old. Most of them were at the age of fourteen (see figure 3).. 195.

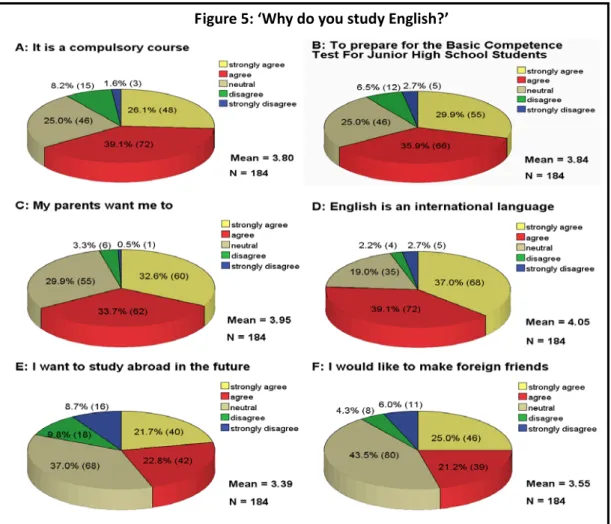

(9) 4.2 Students’ Experiences of English Learning According to the result the survey, over 40% of the students were indifferent towards English learning, (see figure 4). In fact, when turning their responses into scores, with 5 being ‘like it very much’, 4 being ‘like it’, 3 being ‘neutral’, 2 being ‘dislike it’, and 1 being ‘dislike it very much’, the mean score was 2.98, which fell slightly below the theoretical mean of 3. Figure 5: ‘Why do you study English?’ . Moving on to question 2, ‘Why do you study English?’, the students seemed to have the least disagreement on the item of ‘my parents want me to’, with merely seven students showing ‘disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’ (see figure 5). However, rather than conforming to pressure from their parents, even more students appeared to acknowledge the fact that ‘English is an international language’, which resulted in this item having the most positive responses. By contrast, it appears that in general ‘study abroad’ or ‘make foreign friends’ was not currently one of the primary incentives that motivated them to study English. Apart from the options given, some students wrote that they think ‘learning English is cool’, ‘it is beneficial for me when finding a job in the future’, ‘I am interested in it’; others said that they needed this language ‘when playing video games’, ‘for using certain software’, or ‘when using the Internet’.. 4.3 Students’ Experiences of Using Mobile Phones 196.

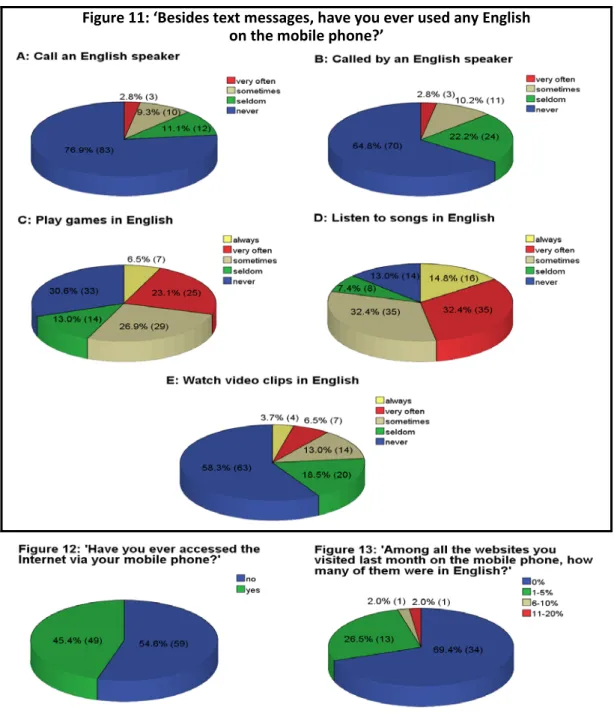

(10) Out of the 184 students, 108 had a mobile phone of their own, representing 58.7% of the total students surveyed (see figure 6). Students who had had their own handset for one to two years were the biggest group (see figure 7).. Concerning what functions students’ mobile phones have other than voice talk and SMS, the result of the survey is shown in figure 8, among which ‘Internet’ and ‘dictionary’, the two functions that are more closely related to language learning, were not as widely reported as the other functions. Only 71 of the students’ mobile phones were web-enabled, and a built-in dictionary was seen in less than 40 handsets.. When asked if they liked using these functions of their mobile phones ‘for fun’, most of the students’ responses were positive, suggesting that in addition to the traditional usage of voice talks and short messages, the supplementary functions on handsets do hold a certain attraction for these youngsters (see figure 9). In terms of English applied when using mobile phones, over 80% of the handset owners reported that none of the text messages sent in the last month were in English (see figure 10). In figure 11, students’ English use in other mobile phone applications is shown in five different categories, among which English seemed to be used the least in voice calls. Contrastingly, listening to English-language songs seemed to be a very common activity for these handset owners. 197.

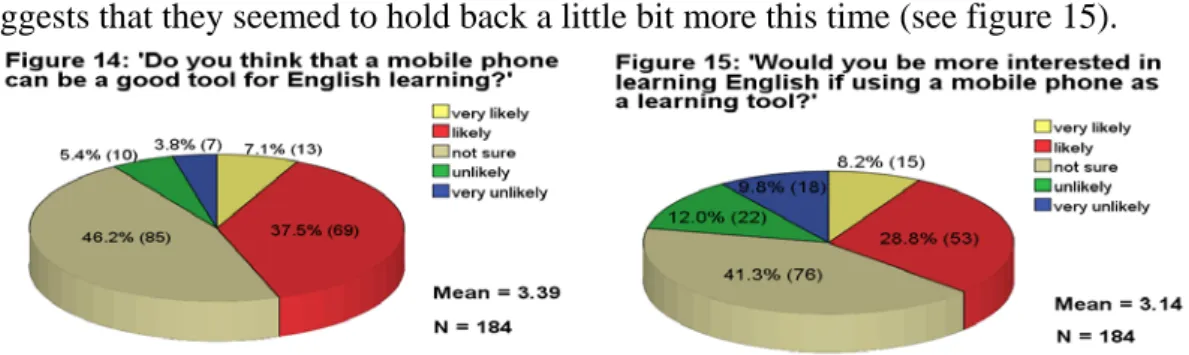

(11) Figure 11: ‘Besides text messages, have you ever used any English on the mobile phone?’ . With regard to students’ experiences of using their mobile phones to access the Internet, despite the fact that in figure 8 there were 71 students whose handsets were web-enabled, only 49 of them reported to have accessed Internet via their mobile phones (see figure 12), and few of the websites visited were in English (figure 13).. 4.4 Students’ Attitudes towards Learning English with Mobile Phones From question 11 onwards, whether or not they had a handset of their own, all of the students’ responses were calculated. When asked if they thought that a mobile phone could be a good tool for English learning, a mean score of 3.39 suggests that overall the students were somewhat optimistic about this concept in the future (see figure 14). However, when it comes to whether they would gain more interest in English if learning this language with their handsets, the lower mean score of 3.14 198.

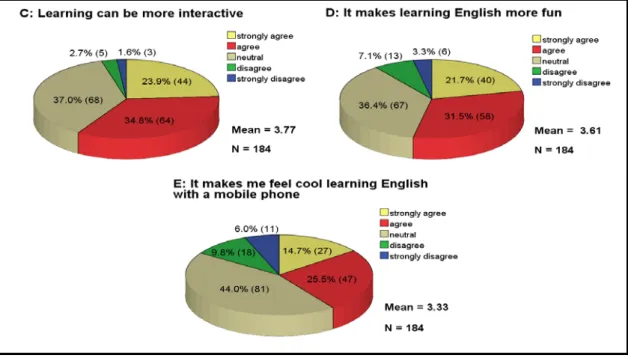

(12) suggests that they seemed to hold back a little bit more this time (see figure 15).. As for aspects which the students would care most about if in the future they were given the opportunity to experience English learning via their handsets, all of the three items received moderate high score, suggesting that these criteria might actually affect their decision making (see figure 16). Figure 16: ‘If you were provided the opportunity to learn English using a mobile phone, what would concern you most?’ . The two subsequent questions were to investigate the students’ attitudes towards the advantages and disadvantages that were mentioned in the previous research. Figure 17 shows the results of students’ responses regarding the strengths of using mobile phones to learn English. The highest mean is 3.77, suggesting that the students were more attracted to the more two-way learning style made possible by handsets. Figure 17: ‘What are the reasons that would make you want to use a mobile phone to learn English?’ . 199.

(13) On the other hand, regarding the possible reasons that might stop the students from trying to use mobile phones as learning tools, apparently the price issue was considered a problem by most of the students. Out of all students, only eleven of them did not think that the charge for such a service was an issue for them (see figure 18). Figure 18: ‘What do you think would make you not want to use a mobile phone for English learning?’ . In addition, other factors such as the miniaturised screens and keypads as well as users’ resistance to using their communication tools for learning purposes were all 200.

(14) recognised as being barriers by more than half of the students. The only item that was perceived to be problematic by less than half of the respondents was the statement of ‘I need to be very focused when learning, using a mobile phone to learn English is too distracting for me’. As a whole, the mean of the scores in the five items were all above 3, the theoretical mean, suggesting that for these handset owners, the barriers listed were indeed challenges that are yet to be overcome if mobile phones are to be applied for learning purposes. As for under what conditions would the students be willing to use their handsets for English learning, a vast majority of the respondents indicated that they would do it only when they felt it necessary (see figure 19). In line with the results of previous questions concerning the price issue, the second most ticked item was ‘when it is cheap enough’, suggesting that capital expenditure will continue to be one of the priority concerns during these users’ decision making. By contrast, the pressure from the teacher or peers did not seem to play an important part in most of the students’ minds. In addition to the given options, some other students wrote other circumstances, including ‘when parents agree’, ‘when I have nothing else to do’, ‘when I am in a foreign country’, and so forth. However, there were still some respondents claiming that they would not try it at all. The last question was open-ended, in which the students were asked about their expectations of mobile phones in terms of ways that this technology could assist their English learning in the future. Many of the students mentioned the function of a translator, which makes it possible to obtain information in an instant. Others suggested that on their mobile phones, English learning in the forms of games, songs and video conferencing with a teacher would be interesting and helpful. However, there were some respondents who remained very much against the idea of using their handsets for language, whether it was because they wanted to keep their handsets purely geared towards communication, or simply because they did not like learning English in the first place as claimed.. 5 DISCUSSIONS With the intention of discovering how students’ past experiences in English learning as well as their use of mobile phones correlate with their attitudes towards the concept of using handsets for the English language, the replies collected were analysed by looking into the composition of the respondents with regard to certain 201.

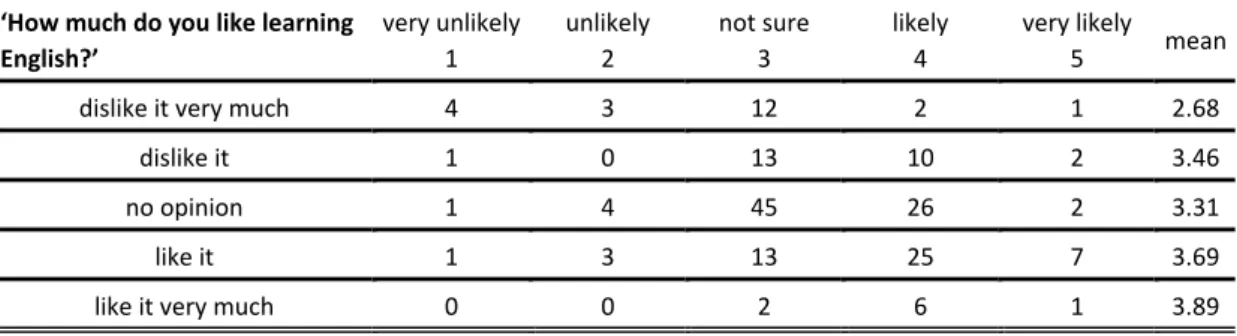

(15) items. The central questions regarding this concept were contained in questions 11 and 12 of the questionnaire, which are ‘Do you think that a mobile phone can be a good tool for English learning?’ and ‘Would you be more interested in learning English if using a mobile phone as a learning tool?’ respectively.. 5.1 Students’ Experiences of English Learning in General and Their Reception of Using Mobile Phones for Language Learning 5.1.1 ‘How much they like learning English’ as a variance With regard to how the students’ fondness of learning English correlates with their attitudes towards the prospect of handsets being learning tools, it seems that their viewpoints were influenced quite significantly by their feelings towards this language. Table 1 and 2 presents the mean scores of what the respondents think of mobile phones being used for learning purposes, based on the various degrees of their like or dislike for the language. When using one-way ANOVA for analysis, the results showed that the variances of the respondents’ reception of English in both their responses to question 11 [F(4, 179) = 7.30, p = 0.00] and 12 [F(4, 179) = 13.76, p = 0.00] differ significantly. Table 1: ‘Do you think that a mobile phone can be a good tool for English learning?’ ‘How much do you like learning very unlikely English?’ 1 . unlikely 2 . not sure 3 . likely 4 . very likely mean 5 . dislike it very much . 4 . 3 . 12 . 2 . 1 . 2.68. dislike it . 1 . 0 . 13 . 10 . 2 . 3.46. no opinion . 1 . 4 . 45 . 26 . 2 . 3.31. like it . 1 . 3 . 13 . 25 . 7 . 3.69. like it very much . 0 . 0 . 2 . 6 . 1 . 3.89 N=184. Table 2: ‘Would you be more interested in learning English if using a mobile phone as a learning tool?’ ‘How much do you like learning very unlikely English?’ 1 . unlikely 2 . not sure 3 . likely 4 . very likely mean 5 . dislike it very much . 13 . 3 . 4 . 1 . 1 . 1.82. dislike it . 0 . 6 . 9 . 10 . 1 . 3.23. No opinion . 4 . 10 . 38 . 20 . 6 . 3.18. like it . 0 . 3 . 22 . 18 . 6 . 3.55. like it very much . 1 . 0 . 3 . 4 . 1 . 3.89 N=184. 5.1.2 ‘The purposes of learning English’ as a variance Another noteworthy phenomenon was that when using one-way ANOVA to examine students’ responses for question 2, ‘Why do you study English’ and the correlation with their attitudes in question 19, strong significant differences were found on the 2D [F(4,179) = 12.00, p = 0.00], 2E [F(4, 179) = 8.01, p = 0.00], and 2F 202.

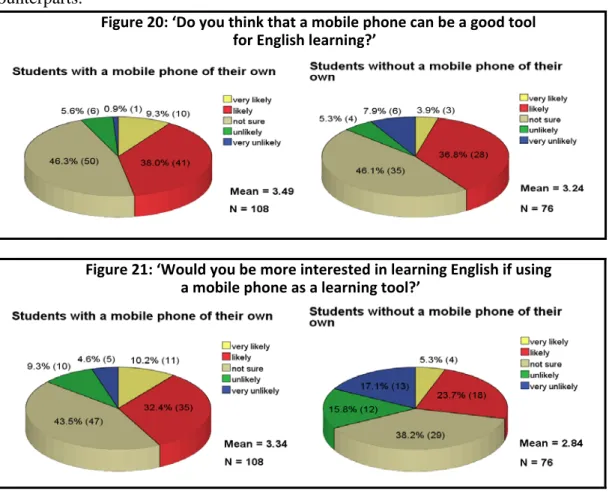

(16) [F(4, 179) = 5.71, p = 0.00]. Likewise, the students’ attitudes in question 20 also seem to be strongly correlated with their responses to question 2D [F(4, 179) = 5.70, p = 0.00], 2E [F(4, 179) = 13.38, p = 0.00], and 2F [F(4, 179) = 6.55, p = 0.00], except this time the variance of 2A was also significant [F(4, 179) = 2.86, p = 0.03]. That is to say, for these students who acknowledged that English was an international language, who wanted to study abroad more, and who would like to make more foreign friends, the advantages of learning English from a mobile phone appeared to be appreciated more.. 5.2 Students’ Experiences of Using Mobile Phones in General and Their Receptions of Using Them as Tools for Language Learning 5.2.1 ‘Ownership of a handset’ as a variance In figure 14 the mean score of all students’ responses for question 11 is 3.39. After separating the students by whether they had a handset of their own or not, the results are presented in figure 20. From the 108 mobile phone owners, the mean score of 3.49 was slightly higher than the 3.24 from the remaining 76 students who did not have one of their own, suggesting that these owners’ overall attitudes towards handsets being used as learning equipment is more positive than their phoneless counterparts. Figure 20: ‘Do you think that a mobile phone can be a good tool for English learning?’ . Figure 21: ‘Would you be more interested in learning English if using a mobile phone as a learning tool?’ . With regard to the likelihood that mobile phones would help to boost the students’ interest in English learning, a bigger discrepancy can be seen when the 203.

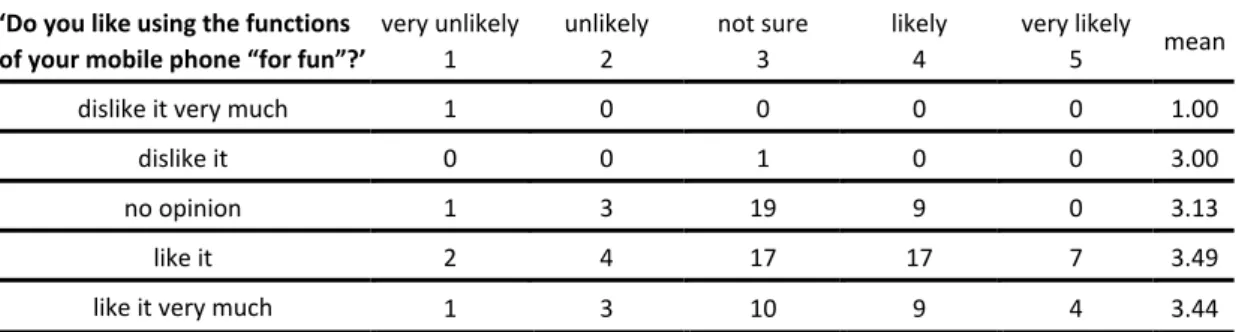

(17) results are analysed according to the state of the handset ownership (see figure 21). Using the t-test for independent samples, a significant difference can be found between those who have a mobile phone of their own and those who do not on their attitudes towards question 11 (t = 2.02, df = 182, p = 0.05). Even stronger significance was found on their attitudes towards question 12 (t = 3.25, df = 182, p = 0.00). 5.2.2 ‘Students’ ‘fondness of using their handsets’ as a variance From the data in table 3, most of the numbers in the mean section seemed to increase steadily along with the users’ growing attachment to their handsets. Although the highest mean occurred in the students who liked using the functions of their mobile phones moderately rather than those who enjoyed it a lot, the overall mounting scores did mark the significance of ‘how much’ they liked using their handsets as an influential factor when they envisioned the future of these technical devices. Table 3: ‘Do you think that a mobile phone can be a good tool for English learning?’ ‘Do you like using the functions very unlikely of your mobile phone “for fun”?’ 1 . unlikely 2 . not sure 3 . likely 4 . very likely mean 5 . dislike it very much . 0 . 1 . 0 . 0 . 0 . 2.00. dislike it . 0 . 0 . 1 . 0 . 0 . 3.00. No opinion . 0 . 1 . 21 . 9 . 1 . 3.31. like it . 1 . 2 . 17 . 20 . 7 . 3.64. like it very much . 0 . 2 . 11 . 12 . 2 . 3.52 N=108. Likewise, in table 4 a ‘quasi-orderly’ distribution can also be found when extracting the mean scores from these groups. The overall average of each group implied that the more they are emotionally attached to their handsets, the more likely they might be motivated to learn English if one day mobile phones are turned into learning tools in the future, and vice versa. Table 4: ‘Would you be more interested in learning English if using a mobile phone as a learning tool?’ ‘Do you like using the functions very unlikely of your mobile phone “for fun”?’ 1 . unlikely 2 . not sure 3 . likely 4 . very likely mean 5 . dislike it very much . 1 . 0 . 0 . 0 . 0 . 1.00. dislike it . 0 . 0 . 1 . 0 . 0 . 3.00. no opinion . 1 . 3 . 19 . 9 . 0 . 3.13. like it . 2 . 4 . 17 . 17 . 7 . 3.49. like it very much . 1 . 3 . 10 . 9 . 4 . 3.44 N=108. Interestingly enough, though, when using one-way ANOVA to calculate the data, the variance of the respondents’ attitudes towards handsets was found to be significant only in question 12 (p value = 0.05) but not question 11 (p value = 0.11). That is to say, how much the students like to use their handsets may not unduly affect their judgments on these handhelds being possible good learning tools, but rather their 204.

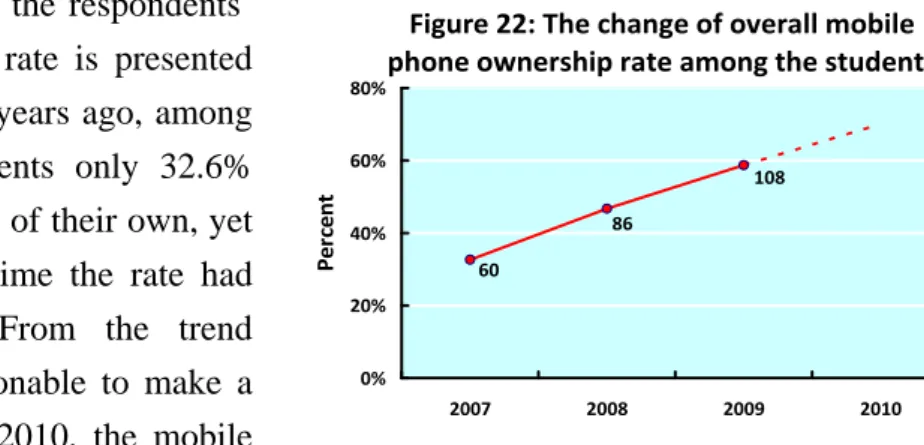

(18) fondness of the devices seemed to give them increased optimism about being more interested in English if they could learn it using mobile technology.. 5.3 The Change of the Respondents’ Mobile Phone Ownership Rate. Percent. The change of the respondents’ Figure 22: The change of overall mobile handset ownership rate is presented phone ownership rate among the students 80% in Figure 31. Two years ago, among 60% these 184 respondents only 32.6% 108 86 had a mobile phone of their own, yet 40% 60 in just two years time the rate had 20% soared to 58%. From the trend 0% revealed, it is reasonable to make a 2007 2008 2009 2010 prediction that by 2010, the mobile phone penetration rate among these students will be marching towards 70%.. 6 CONCLUSIONS Looking at the overall results of this study it is clear that the students’ attitudes towards using mobile phones to learn English are strongly correlated with their original attitude to this language, which confirms the hypothesis made earlier in this study. On the whole, the respondents who had a mobile phone of their own seemed to be more receptive to this new technology being used for learning purposes than those who did not have one. With regard to the benefits and the drawbacks of learning English though handsets that were brought up in the previous research, most of the respondents seemed to acknowledge the potential advantages brought by handsets in terms of ways to facilitate learning. They also agreed with most of the factors such as technical, psychological, and price issues which might impede users from making use of this new technology for learning purposes. On the other hand, it is worth noting the discrepancy existing between the students’ responses regarding the questions ‘Do you think that a mobile phone can be a good tool for English learning’ and ‘Would you be more interested in English if using a mobile phone as a learning tool?’ For some reason, on the whole the students seemed to hold a more positive view on the former question than the latter. In other words, in their minds, believing in the capacity of mobile phones is one thing but when it comes to how much these devices could actually enhance their attraction to learning the language, they were not so sure. Whether it was psychological concerns or pedagogical factors that caused such a phenomenon, more research is needed in the future to probe into the exact causes lying in between that affect learners’ attitudes. As for the prevalence of mobile phones, based on the findings it seems that in 205.

(19) Taiwan at this moment the popularisation of handsets at junior high school level has not quite reached the extent that every student has a handset of their own. Yet, according to the tendency revealed, a promising rapid expansion of ownership among these early teenagers seems to forecast that in probably just a handful of years the digital environment will be ready for educators to think seriously about incorporating the use of mobile phones into language instruction. What the future might hold for learning with mobile technologies is yet to be understood. What kinds of practice and materials are more suitable for the interface of handsets, how should the use of handsets be incorporated in the process of language education, and to what extent are the students supposed to rely on these devices? These questions still leave a lot of room for discussion and investigation. This study, however, is simply a snapshot of the current digital environment for the target group rather than an experiment or a longitudinal observation over a long period of time. Nevertheless, based upon the findings of this preliminary investigation, designers and developers of mobile language learning software can still more or less anticipate what reactions ‘could’ be seen in Taiwan’s current junior school campus. Living in an era where a few short years can make a huge difference, it is quite likely that what seems to be impossible today may no longer be a far-fetched dream by tomorrow. Until the day that handheld devices like mobile phones really become part of our learning experience, there is no reason why we should not keep trying. After all, seeking ways to assist learning is what has been driving designers to create new material in the first place. From what was observed in this research, the students who had more exposure to mobile phone use were prone to be more receptive about the educational usage of these communication tools—if this finding can withstand the test of time and maintain its validity across various contexts as well as different circumstances, then it is quite conceivable that with the mobile phone penetration rate mounting around the world, increased application of handsets in the domain of English learning will be witnessed in the foreseeable future.. BIBLIOGRAPHY Balakrishnan, V. and H.P.Y. Paul. 2008. ‘A study of the effect of thumb sizes on mobile phone texting satisfaction’. Journal of Usability of Studies 3(3): 118-128. Dias, J. 2002. ‘Cell phones in the classroom: boon or bane? Part 2’ C@lling Japan, 10(3): 8-13 http://jaltcall.org/cjo/10_3.pdf (visited 22/04/10). Dörnyei, Zoltán. 2003. Questionnaires in second language research: construction, administration, and processing. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Foreseeing Innovative New Digiservices (FIND) of the Institute for Information Industry (III). 2009. ‘Mobile phone subscribers Q1 2008’ http://www.find.org. tw/eng/news.asp?msgid=396&subjectid=13&pos=1 (visited 22/04/10). Godwin-Jones, R. 2005. ‘Messaging, Gaming, Peer-to-peer Sharing: Language 206.

(20) Learning Strategies & Tools for the Millennial Generation’. Language Learning & Technology 9(1): 17-22. Goggin, G. 2006. Cell Phone Culture: Mobile technology in everyday life. London; New York: Routledge. GSM Association. 2009. ‘4 bln mobile connections worldwide in 2008’ http://www.itfacts.biz/4-bln-mobile-connections-worldwide-in-2008/12656 (visited 22/04/10). Kiernan, P.J. and K. Aizawa. 2004. ‘Cell phones in task based learning: are cell phones useful language learning tools?’ ReCALL 16(1): 71-84. Kukulsky-Hulme, A. 2005a. ‘Introduction’, in Kukulska-Hulme, A. and J. Traxler (eds.). Mobile Learning: a handbook for educators and trainers. London: Routledge. Kukulska-Hulme, A. and J. Traxler. 2005. ‘Mobile teaching and learning’, in Kukulska-Hulme, A. and J. Traxler (eds.). Mobile Learning: a handbook for educators and trainers. London: Routledge. Kukulska-Hulme, A., J. Traxler and J. Pettit. 2007. ‘Designed and user-generated activity in the mobile age’. Journal of Learning Design 2(1): 52-65. Lu, M. 2008. ‘Effectiveness of vocabulary learning via mobile phone’. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 24: 515-525. Morita, M. 2003. ‘The Mobile-based Learning (MBL) in Japan’. Proceedings of the First Conference on Creating, Connecting and Collaborating through Computing (C5’03). http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber= 1222348&isnumber=27456 (visited 22/04/10). Nah, K. C., P. White, R. Sussex. 2008. ‘The potential of using a mobile phone to access the Internet for learning EFL listening skills within a Korean context’. ReCALL 20 (3): 331-347. Naismith, L., P. Lonsdale, G. Vavoula, and M. Sharples. 2004. ‘Literature Review in Mobile Technologies and Learning’. FutureLab Report 11. http://www.futurelab. org.uk/resources/documents/lit_reviews/Mobile_Review.pdf (visited 22/04/10). O’Malley, C., G. Vavoula, J. Glew, J. Taylor, M. Sharples and P. Lefrere. 2003. Guidelines for learning/ teaching/ tutoring in a mobile environment. Mobilearn project deliverable. http://www.mobilearn.org/download/results/guidelines.pdf (visited 22/04/10). Prensky, M. 2005. ‘What Can You Learn from a Cell Phone? Almost Anything!’ Innovate 1(5) http://www.innovateonline.info/index.php?view=article&id=83 (visited 22/04/10). Quinn, C. 2000. ‘mLearning: Mobile, wireless, in your pocket learning’. LineZine Fall 2000 http://www.linezine.com/2.1/features/cqmmwiyp.htm (visited 22/04/10). Stockwell, G. 2007. ‘Vocabulary on the Move: Investigating an intelligent mobile phone-based vocabulary tutor’. Computer Assisted Language Learning 20(4): 365-383. Stockwell, G. 2008. ‘Investigating learners preparedness for and usage patterns of mobile learning’. ReCALL 20(3): 253-270. Thornton, P. and C. Houser. 2005. ‘M-learning: learning in transit’, in Lewis, P.N.D. (ed.). The Changing Face of CALL: A Japanese Perspective. Lisse, Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger Publishers. Thornton, P. & C. Houser. 2005. ‘Using mobile phones in English education in Japan’. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning 21 (3): 217-228. Traxler, J. 2005. ‘Mobile Learning - Its Here But What Is It?’ Interactions Journal 9(1) http://www2.warwick.ac.uk/services/ldc/resource/interactions/archive/issue25/tr axler (visited 22/04/10). Wang, S. and M. Higgins. 2006. ‘Limitations of mobile phone learning’. The JALT CALL Journal 2(1): 3-14. Wang, M., R. Shen, D. Novak, X. Pan. 2009. ‘The impact of mobile learning on students’ learning behaviours and performance: Report from a large blended classroom’. British Journal of Educational Technology 40(4): 673-695.. 207.

(21) APPENDIX Questionnaire (English) Section I: Experiences of learning English 1. 2.. How much do you like learning English? like it very much like it no opinion dislike it dislike it very much Why do you study English? A. It is a compulsory course strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree B. To prepare for the Basic Competence Test For Junior High School Students strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree C. My parents want me to strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree D. English is an international language strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree E. I want to study abroad in the future strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree F. I would like to make foreign friends strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree Other: _________________________________ . . Section II: Experiences of using mobile phone 3. 4. 5.. 6. 7. 8.. Do you have a mobile phone of your own? yes no (if no please go to question 11) How long have you had your own mobile phone? <1 year 1‐2 years 2‐3 years 3‐4 years >4 years What functions does your current mobile phone have? (more than one answer can be chosen) mp3 camera Internet dictionary voice recording video recording bluetooth Java games 3G other (please specify): _________________________________ Do you like using the functions of your mobile phone ‘for fun’? like it very much like it no opinion dislike it dislike it very much Among all the text messages you sent last month, how many of them were in English? 0% 1‐5% 6‐10% 11‐20% >20% Besides text messages, have you ever used any English on the mobile phone? A. Call an English speaker: always very often sometimes seldom never B. Called by an English speaker: always very often sometimes seldom never C. Play games in English: always very often sometimes seldom never D. Listen to songs in English: always very often sometimes seldom never E. Watch video clips in English: always very often sometimes seldom never Other (please specify): _________________________________ . 9.. Have you ever accessed the Internet via your mobile phone? yes no (if no go to question 11) 10. Among all the websites you visited last month on the mobile phone, how many of them were in English? 0% 1‐5% 6‐10% 11‐20% >20% . Section III: Attitudes towards ‘using a mobile phone to learn English’ 11. Do you think that a mobile phone can be a good tool for English learning? very likely likely not sure unlikely very unlikely 12. Would you be more interested in learning English if using a mobile phone as a learning tool? very likely likely not sure unlikely very unlikely 208.

(22) 13. If you were provided the opportunity to learn English using a mobile phone, what would concern you most? A. The price (ex: how much does it cost?) strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree B. Convenience (ex: is it easy to use?) strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree C. Effectiveness (ex: will it really improve my English?) strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree D. Other (please specify): _________________________________ 14. What are the reasons that would make you want to use a mobile phone to learn English? A. I can learn English anytime anywhere strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree B. It can increase my chances to learn English strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree C. Learning can be more interactive (similar to using computers) strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree D. It makes learning English more fun strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree E. It makes me feel cool learning English with a mobile phone strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree F. Other(please specify): _________________________________ 15. What do you think that would make you not want to use a mobile phone for English learning? A. The screen of the mobile phone is too small strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree B. The keypad of the mobile phone is inconvenient for inputting strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree C. Using a mobile phone to learn English is too expensive strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree D. I need to be very focused when learning, using a mobile phone to learn English is too distracting for me strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree E. I am more accustomed to using a mobile phone as a tool for communication as opposed to learning purposes strongly agree agree neutral disagree strongly disagree F. Other (please specify): _________________________________ 16. In the future under which circumstances would you consider using a mobile phone as a tool for English learning? (more than one answer can be chosen) when required by the teacher after friends or classmates had used it when it is cheap enough only when I feel that I need to other: _________________________________ 17. In what ways do you expect mobile phones help you to learn English in the future? Please briefly write them down: _______________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________ . Personal information Age: 12 13 14 15 Gender: male female Grade: seventh grade eighth grade ninth grade . 209.

(23)

數據

相關文件

• e-Learning Series: Effective Use of Multimodal Materials in Language Arts to Enhance the Learning and Teaching of English at the Junior Secondary Level. Language across

In the context of the English Language Education, STEM education provides impetus for the choice of learning and teaching materials and design of learning

Building on the strengths of students and considering their future learning needs, plan for a Junior Secondary English Language curriculum to gear students towards the learning

• e‐Learning Series: Effective Use of Multimodal Materials in Language Arts to Enhance the Learning and Teaching of English at the Junior Secondary Level. Language across

Objectives To introduce the Learning Progression Framework LPF for English Language as a reference tool to identify students’ strengths and weaknesses, and give constructive

Specifically, the senior secondary English Language curriculum comprises a broad range of learning targets, objectives and outcomes that help students consolidate what they

Students are introduced to the writing task - a short story which includes the sentence “I feel rich.” They are provided with the opportunity to connect their learning

Building on the strengths of students and considering their future learning needs, plan for a Junior Secondary English Language curriculum to gear students towards the