Chapter II Literature Review

Chapter two provides the theoretical background of the present study. This chapter is divided into four parts. Section 2.1 includes pragmatic theories such as Grice’s (1967) theory of Cooperative Principle, Sperber and Wilson’s (1995) Relevance Theory, Brown and Levinson’s (1987) Politeness Principle, and Leech’s (1983) maxims of PP. The above theories accounted for how people communicate in daily conversation. Section 2.2 contains humor theories such as Jones (1970), Schultz (1972), and Suls’s (1972) Incongruity-Resolution Theory, Raskin’s(1985) Semantic Script Theory of Humor, and Raskin and Attardo’s (1994) General Theory of Verbal Humor. These theories presented the structure of humorous texts, and illustrated how people comprehend joke-carrying texts and how people communicate differently in joke-telling from daily conversation. Section 2.3 lists various types of linguistic ambiguity and linguistic strategies used in jokes, categorized by Pepicello and Weisberg (1983), Deneire (1995), and Dienhart (1998), with illustrative examples.

Section 2.4 is further divided into two subsections. Section 2.4.1 reviews related empirical studies on jokes, including Hung’s (2002) linguistic analysis of Mandarin cold jokes and Tsai’s (1997) linguistic analysis of Chinese sexual punning jokes.

Section 2.4.2 reviews empirical studies on sitcoms, including Bubel and Spitz’s (2006) study on the characterization of women through the telling of dirty jokes in Ally

Mcbeal, and Paolucci and Richardson’s (2006) study on how Goffman (1952,1959,1983) reveals Seinfeld’s critique of American culture.

2.1 Pragmatic Theories

In this section, we are going to review Grice’s (1967) theory of Cooperative Principle, Sperber and Wilson’s (1995) Relevance Theory, Brown and Levinson’s (1987) Politeness Principle, and Leech’s (1983) maxims of PP. These pragmatic theories accounted for how people communicate in daily conversation.

2.1.1 Grice’s theory of Cooperative Principle

Grice (1975) argued that speakers intend to be cooperative when they talk, and he formalized the Cooperative principle: make your contribution to the conversation such as is required, committed to truth, relevance, clarity and to providing the right quantity of information at any given time, by the accepted purpose of the talk

exchange which you are engaged in (Grice, 1967). Based on this principle, he brought up four maxims.

1. Quantity:

1) Make your contribution to the conversation as informative as necessary 2) Do not make your contribution to the conversation more informative than necessary.

2. Quality:

1) Do not say what you believe to be false.

2) Do not say that which you lack adequate evidence.

3. Relation:

Be relevant.

4. Manner:

1) Avoid obscurity of expression 2) Avoid ambiguity.

3) Be brief.’

4) Be orderly.

According to Grice, these maxims enable the listener to draw inferences from utterances. Whenever a maxim is flouted, there must be an implicature to save the utterance from merely being a faulty conversational contribution. For instance, self-evidently true or obviously false statements must be uttered for some other purpose than to convey simply their stated meaning. A number of rhetorical strategies, which might be employed in the jokes in the present study, have been considered to flout Gricean maxims. For example, metaphors, overstatements (exaggeration), understatements (euphemism), and sarcasm are said to flout the maxim of quality or quantity. It is worth noticing that in daily conversation, when the speaker flouts the maxim of quality by telling a lie, more often than not, the hearer is not aware that what the speaker said is a lie. Nonetheless, in sitcoms the audience in front of the TV knows the speaker is lying, even though the hearer does not.

Grice also drew a distinction between generalized and particularized

conversational implicature. Generalized conversational implicatures arise irrespective of the context in which they occur while particularized conversational implicature is context-bound. They are inferences we need to draw if we are to understand how an utterance is relevant in some context. In the jokes in sitcoms, the funny lines are usually caused by the context-bound particular implicature. For instance, we could see from the present study that sometimes the hearer may fail to understand the speaker’s particularized implicature due to lack of context. This misunderstanding evokes laughter from the audience.

In addition to the aforementioned conversational implicature, an utterance may obtain conventional implicature, “non-truth conditional inferences that are not derived from super-ordinate pragmatic principles like the maxims but are simply attached by convention to particular lexical items or expressions” (Levinson, 1983:127). For instance, in the sentence I’m happy but she’s sad, the entailment of but is a

coordinating function like and, while the conventional implicature is a contrast between the two conjoined propositions. This can also be illustrated by the following example from Friends.

<1> (from 416) After Rachel confessed her love for Joshua, he told her that he liked her too.

Rachel: You liked me? Oh my god. I can’t believe this. All this time I liked you and you liked me!

Joshua: But…

Rachel: Oh no no no. Don’t say ‘but’. No-no. ‘But’ is never good. Let’s just leave it at you like me and I like you.

Joshua: Ok. Uh…however…

Rachel: Oh, now see? That’s a fancy ‘but’.

In this example, Joshua was trying to tell Rachel that he was interested in her too, but his marriage just ended, and he was not ready for a serious relationship yet. When Rachel heard the word but in Joshua’s line, she immediately interrupted him because she knew but indicates the addition of an adversative proposition. In other words, she sensed that the proposition following but would be contrary to the proposition before it, which had revealed the possibility of Rachel and Joshua going out (since Joshua said he liked Rachel too). That is, she was aware that the following proposition would be rejection. As a result, Rachel tried to stop him from talking. In this example, the conventional implicature of but plays a more important role that its entailment.

Grice’s theory of meaning can be summarized in Figure 2.1.

Conveyed:

1. said/ entailed 2. implicated

1) conventionally 2) conversationally a) generalized

b) particularized

Figure 2.1 Summary of Grice’s theory of meaning

2.1.2. Sperber and Wilson’s Relevance Theory

According to Sperber and Wilson (1995), a single principle of relevance is sufficient to explain the process of utterance understanding. That is, in utterance understanding, addressees should recover the most relevant interpretation from an infinite set of contextual assumptions. They replaced Grice’s implicature with a two-stage process in which the addressee recovers first an explicature—an inference or series of inferences which enrich the under-determined form of an utterance to a full propositional form, and then an implicature—an inference which provides the addressee with the most relevant interpretation of the utterance. Explicatures preserve and elaborate the propositional form of the original utterance, while implicatures are new logical forms.

In Relevance theory, every utterance is guaranteed its own particular relevance.

To understand an utterance is to prove its relevance. In order to prove the relevance of an utterance, the speaker must make assumptions about hearer’s cognitive abilities and contextual resources. When the propositional form of an utterance has been fully elaborated, the utterance will be considered a premise. Then, the hearer will take this premise, together with other available non-linguistic premises as contextual resources, and try to deduce the most relevant understanding. The most accessible interpretation is the most relevant. An assumption is relevant to an individual to the extent that the effort required to achieve these positive cognitive effects is small. It is also noted that in relevance theory, context refers to accessible items of information stored in

short-term and encyclopedic memories or manifest in the physical environment.

According to Grundy (2000), Relevance theory was able to account for

understanding failures, which occur when the processing load is too heavy. Relevance theory explains the fact that not all utterances are successfully understood, and that a particular utterance may be understood in different ways and to different degrees by different hearers.

In the current study, we can see a variety of misunderstandings in Friends resulting from the fact that what the hearer retrieves as the most relevant

interpretation from the speaker’s utterance is different from the speaker’s intended meaning. For example, the hearer may misunderstand the speaker’s implicature due to lack of context or presupposition differences, or s/he may not get the speaker’s

implicature at all because s/he does not take this implicature as the most relevant interpretation. At times, the hearer may retrieve the literal meaning as the most relevant interpretation of the speaker’s utterance while in fact the speaker means the non-literal implicature. Sometimes vice versa (i.e. the speaker means the utterance literally, but the hearer mistakes the non-literal implicature as the most relevant inference.)

2.1.3 Politeness Principle

The most fully elaborated theory on linguistic politeness is Brown and Levinson’s (1987) model of politeness strategies. In their account, politeness strategies can be seen as a way of encoding the power-distance relationship of the conversation participants, and the extent to which a speaker imposes on or requires something of their addressee. Politeness principles reveal that every utterance is uniquely designed for its audience by creating a context intended to match the addressee’s notion of how s/he should be addressed. In other words, politeness is the term we use to describe the extent to which actions, including the way things are said, match addressee’s perceptions of how they should be performed.

Brown and Levinson worked with the notion of face, which refers to a property that all human beings have, and is broadly comparable to self-esteem. They claimed that in most encounters our face is at risk. Therefore, we use redressive language to compensate for the face threat in order to satisfy the face wants of our addressee and our own. Brown and Levinson divided face into two varieties: positive face and negative face. Positive face refers to a person’s wish to be well thought of. For instance, we usually have the desire to be understood by others, to be admired by others, and to be treated like a trustworthy friend and so on. On the other hand, negative face refers to our wish not to be imposed on by others, and to be allowed to go about our business unimpeded. For example, in the sentence, Got the time, my friend (adapted from Grundy, 2000), the familiar term my friend and the informal elliptical form got show that this utterance is geared towards the positive face of the addressee by treating him or her as a friend, while in the sentence, Could I just borrow a little bit of tissue (adapted from Grundy, 2000), the minimizing terms just and a little bit and the euphemistic verb borrow are all oriented to the negative face of the addressee by downplaying the imposition and the possibilities of face loss. According to Brown and Levinson, politeness principles aim to avoid disagreements and

minimize face loss.

In Brown and Levinson’s model, there are three main strategies for us to choose from when we have a face-threatening act to perform.

1. Do the act on record

1) Baldly without redress

2) With positive politeness redress 3) With negative politeness redress 2. Do the act off-record

3. Don’t do the act.

Here, “on the record” means doing the act without attempting to hide it, while “off the record” means doing the act in such a way as to pretend to hide it. In choosing one of the above strategies, speakers work with an equation in which distance differential, power differential, and imposition are computed.

Social Distance+ Power Differential + Degree of Imposition

= Degree of face threat to be compensated by appropriate linguistic strategy According to Grundy (2000), one typical source of humor in television sitcoms is the use of politeness strategies that are not the result of the expected computations of Power, Distance, and Imposition.

In Leech’s (1983) Principles of Pragmatics, he also proposed a very

comprehensive view of the Politeness Principle. He argued that the maxims of the CP can not explain why people are often indirect in conveying their meaning.

Consequently, Politeness Principle should be considered as a necessary complement, which rescues the CP from serious trouble since speakers often suppress the desired information in order to uphold the PP. In other words, the indirectness of the speaker’s utterance is usually motivated by politeness. Accordingly, Leech proposed maxims of PP. These maxims tend to appear in pairs, and they are simplified as follows.

(I) Tact Maxim (in impositives and commissives)

(a) Minimize cost of other [(b) Maximize benefits to other]

(II) Generosity Maxim (in impositives and commissives) (a) Minimize benefit to self [(b) maximize cost to self]

(III) Approbation Maxim (in expressives and assertives)

(a) Minimize dispraise of other [(b) Maximize praise to other]

(IV) Modesty Maxim (in expressives and assertives)

(a) Minimize praise of self [(b) maximize dispraise of self]

(V) Agreement Maxim (in assertives)

(a) Minimize disagreement between self and other [(b) Maximize agreement between self and other]

(VI) Sympathy Maxim (in assertives) (a) Minimize antipathy between self and other [(b) Maximize sympathy between self and other]

Based on Leech (1983), not all of the maxims are equally important. For instance, Tact Maxim seems to be a more powerful constraint on conversational behavior than Generosity Maxim, and Approbation Maxim more powerful than Modesty Maxim.

This phenomenon reflects a more general rule that politeness focuses more strongly on other than on self. Moreover, within each maxim, sub-maxim (b) appears to be less important than sub-maxim (a). This illustrates the more general phenomenon that negative politeness is a more important consideration than positive politeness. Note that politeness towards addressee is generally more important than politeness towards a third party.

In the present study of Friends, we can see the characters violate politeness principles by being too direct to each other, which threatens the negative face of the addressee and violates the maxim of Approbation, or being too proud of themselves instead of complimenting others, which ignores the positive face wants of the addressee and violates the maxim of Modesty.

2.2 Humor Theories

This section provides the review of humor theories such as Jones (1970), Schultz (1972), and Suls’s (1972) Incongruity-Resolution Theory, Raskin’s (1985) Semantic Script Theory of Humor, and Raskin and Attardo’s (1994) General Theory of Verbal Humor. These theories presented the structure of humorous texts and illustrated how people comprehend joke-carrying texts, and how people communicate differently in

joke-telling from daily conversation.

2.2.1 Incongruity –Resolution Theory

One of the most reputable humor theories is the Incongruity-Resolution Theory.

The Incongruity–Resolution Theory (IRT) was proposed by Jones (1970), Schultz (1972), and Suls (1972) to explain how a joke is perceived as funny. It is a two-stage model of joke comprehension and appreciation consisting of incongruity and

resolution. Incongruity refers to the discrepancy between the expectation derived from the set-up of a joke, and the punch line of the joke. The greater the discrepancy

between the set-up and the punch line is, the more surprising the punch line is. Once the perceiver of the joke senses the incongruity, she or he will be motivated to resolve the incongruity. If the incongruity is resolved, that is to say, the punch line makes sense with the text, the perceiver gets the joke and humor is evoked. Without a resolution, the perceiver is puzzled and even frustrated (Suls, 1972).

The incongruity resolution theory can be illustrated by the following example:

<2> Mr. Smith has always been proud of his children. Morris is a professor, Sid is an eminent surgeon and Barbara is a famous actress. But Irving!

Irving has flunked out of high school, can’t get a job, fools around all day, and is ugly and smelly. Mr. Smith has always harbored a secret suspicion.

Finally, he asks his beloved wife of fifty years, ‘Tell me the truth. Doesn’t Irving have a different father than the others?’ Mrs. Smith turns red with embarrassment, ‘You’re right, dear’, she confesses. ‘Irving is yours.’

(Lai, 1992)

Based on the set up of this joke, the perceiver may expect that only Irving is not Mr. Smith’s child. However, the punch line reveals that only Irving is Mr. Smith’s child, which is contrary to our expectation and contributes to the incongruity.

Nonetheless, the incongruity can be resolved because the punch line fits the preceding text of the joke; that is, the fact that only Irving is Mr. Smith’s child fits the statement that Irving has a different father than the others.

The present study lends support to the incongruity resolution theory because most of the funny lines in Friends have an incongruity and a resolution structure.

When the incongruity in the funny lines is resolved and makes sense with previous context, the audience understands the joke and laughs.

2.2.2 Semantic Script Theory of Humor (SSTH)

While the Incongruity-Resolution Theory is essentially a cognitive approach into humor, Raskin’s (1985) Semantic Script Theory of Humor (SSTH) is the first

significant formal linguistic treatment of verbal humor. The distinction between verbal humor and non-verbal humor lies in the fact that non-verbal humor refers to situations in which humor occurs without a text. For example, in sitcoms, the humor may arise from the characters’ dramatic body language, or slapstick humor, in which the characters may trip over a banana peel or fall down the stairs. Such non-linguistic phenomenon falls beyond the scope of Raskin’s theory because they cannot be explained by a linguistic theory of humor. The current analysis will also ignore non-verbal humor such as body language in Friends, and will merely investigate the verbal humor in the TV show.

The Main Hypothesis of Raskin’s theory is as follows: (Raskin, 1985: 99) (I) A text can be characterized as a single joke-carrying text if both of the conditions in (II) are satisfied.

(II) (i) The text is compatible, fully or in part, with two different scripts.

(ii) The two scripts with which the text is compatible are opposite.

The script is “a large chunk of semantic information surrounding the word or evoked by it” (Raskin, 1985: 81). It is “a cognitive structure internalized by the native speaker and it represents the native speaker’s knowledge of a small part of the world”

(Raskin, 1985: 83)

Based on the first condition of the Main Hypothesis, the text of a joke is partially or fully compatible with the two different scripts. A typical example of an overlap of two scripts on a joke is as follows:

<3> ‘Is the doctor at home?’ the patient asked in his bronchial whisper. ‘No,’ the doctor’s young and pretty wife whispered in reply. ‘Come right in.’

(Rakin, 1985: 100)

The above joke involves an overlap of two scripts, DOCTOR and LOVER.

The joke begins innocuously by describing a standard situation which immediately evokes an easy and standard script DOCTOR, as we can see from the three words doctor, patient and bronchial. Nonetheless, the young and pretty wife inviting the man who is not her husband to come into her house while the husband is not home evokes the script LOVER.

Moreover, script overlap can be further divided into two types: full overlap and partial overlap. Full overlap means that the two scripts involved are perfectly

compatible with the text of a joke, and there is nothing in the text which can be perceived as odd, redundant, or missing with regard to either script. Jokes involving a full overlap are not common. Many jokes create a partial overlap in the sense that once both scripts are evoked, there are some parts of the text which are incompatible with one of them. That is to say, partial overlap refers to the situation that one or both of the evoked scripts are not acceptable as part of the semantic interpretation of the text.

According to the second condition of the Main Hypothesis, the two scripts should be opposite in a specially defined sense. Raskin (1985) proposes three basic types of oppositions between the real and unreal situation in the script-based theory:

actual and non-actual, normal and abnormal, possible and impossible. The actual situation is the one “in which the joke is actually set, whereas a non-actual situation is the one which is not compatible with the actual setting of the joke” (Raskin, 1985:

112). The normal situation refers to the expected state of affairs and the abnormal one refers to the unexpected state of affairs; a possible situation is a plausible one and an impossible situation is a mush less plausible one. Nonetheless, there are no clear-cut boundaries between these three types. In other words, there is still “a certain amount of mutual penetration and diffusion” (Raskin, 1985: 112).

Based on the Main Hypothesis of the Semantic Script Theory of Humor, for a joke to be funny it must possess at least two scripts which are compatible with the text and are opposite in a special sense. The shift from one script evoked by the text of the joke to the other script is achieved by the semantic script switch trigger. A semantic script switch trigger introduces the second script and imposes a different

interpretation of the text of a joke. According to Raskin, there are basically two types of semantic script switch triggers: ambiguity and contradiction. Ambiguity includes regular ambiguity, quasi-ambiguity, figurative ambiguity, syntactic ambiguity, and situational ambiguity. Contradiction includes “contradiction triggers and

dichotomizing triggers” (Raskin, 1985: 114-117). Nonetheless, in the current study, it seems that these two triggers are not the major strategies in our data.

Raskin even revised Grice’s maxims of the CP and proposed the following set of maxims for the communication mode of joke-telling:

(1) Maxim of Quantity: Give exactly as much information as is necessary for the joke.

(2) Maxim of Quality: Say only what is compatible with the world of the joke.

(3) Maxim of Relation: Say only what is relevant to the joke.

(4) Maxim of Manner: Tell the joke efficiently. (Raskin, 1985: 103)

In accordance with these maxims, “the hearer does not expect the speaker to tell the truth or to convey him any relevant information in joke telling” (Raskin, 1985:

103). Nevertheless, the author holds the view that Raskin’s maxims for the

communication mode of joke telling is unnecessary for funny lines in sitcoms, since Grice’s maxims of CP are sufficient to account for the deviation of joke telling from ordinary conversation. In joke telling, Grice’s maxims are usually flouted on purpose in order to create incongruities and achieve humorous effects. That is, deviation from norms and violation of rules are characteristics of jokes.

Raskin also lists four different situations in which the joke-telling mode of communication takes place. The four situations are created by the combination of one of the two possibilities in (1) with one of the possibilities in (2).

(1) (i) The speaker makes the joke unintentionally.

(ii) The speaker makes the joke intentionally.

(2) (i) The hearer does not expect a joke.

(ii) The hearer expects a joke.

In the first situation with the combination of (1)(i) and (2)(i), both the speaker and the hearer are not aware of the ambiguity in the utterance. Thus, the ambiguity passes unnoticed and no humor occurs. In the second situation with the combination of (1) (i) and (2)(ii), the speaker is not aware of the ambiguity, but the hearer perceives the ambiguity. In the third situation with the combination of (1)(ii) and (2)(i), the speaker intends to crack a joke, but the hearer does not expect a joke from the speaker. Only in the last situation with the combination of (1)(ii) and (2)(ii) do both the speaker and the hearer participate in the communication mode of joke-telling. As a result, the hearer will look for the two overlapping and opposite scripts evoked by the text of the joke based on Raskin’s Main Hypothesis.

From the above four situations, we can see that only the last situation is the prototypical situation of joke telling where both the speaker and the hearer sense the joke and humor is derived. However, if we take the audience’s perspective, all four situations may evoke laughter because the audience in front of the TV is provided

with sufficient contextual information, which the speaker or the hearer may not be fully aware of.

In Friends, we may find similar combinations of possibilities, which lead to various types of misunderstandings. For instance, the hearer may not get the speaker’s implicature, or the hearer may take the speaker’s implicature literally. In some cases, the hearer may take what the speaker says as an implicature but the speaker means it literally.

2.2.3 General Theory of Verbal Humor (GTVH)

In order to account for any kind of humorous texts, Raskin and Attardo (1994) revised the Semantic Script Theory of Humor (SSTH) into General Theory of Verbal Humor (GTVH), which broadens the scope by introducing six Knowledge Resources (KR) that must be taken into consideration when a joke occurs. Theses Knowledge Resources are as follows.

1) Script Opposition (SO): This parameter requires that the two scripts evoked by the text of the joke should be opposite in a special sense, which is the script opposition requirement presented in the SSTH.

2) Logical Mechanism (LM): This parameter explains the way in which two senses, i.e. scripts in the joke, are brought together.

3) Situation (SI): Any joke must be about something and must have some situations. The situation of a joke can be thought of as the props of the joke such as the objects, participants, instruments, activities, and so on.

4) Narrative Strategy (NS): The information in NS accounts for the fact that any joke has to come in the form of narrative organization such as a simple narrative, a dialogue, a riddle and so forth.

5) Target (TA): This KR selects the butt of the joke. The information in

this KR contains the names of groups or individuals with (humorous) stereotypes attached to each. Jokes that do not ridicule someone or something have an empty value for this parameter.

6) Language (LA): This KR contains all the information necessary for the verbalization of a text. It is responsible for the exact wording of the text and includes all the linguistic elements of the text at all levels.

(Attardo 1994)

According to GTVH, every joke can be seen as a six-tuple, which specifies the instantiation of each KR as a parameter. By combining the various values of each parameter, we can generate an infinite number of jokes.

Attardo (1997) claimed that we could draw a parallelism between the

Incongruity-Resolution Theory reviewed before, and the foundations of the GTVH.

The incongruity phase in the IRT model is found to correspond to the Script Opposition in GTVH, and the resolution phase in IRT corresponds to the Logical Mechanism in GTVH. Therefore, Script Opposition and Logical Mechanism are considered crucial in joke analysis. While Script Opposition has been examined in Raskin’s SSTH, Logical Mechanism seems to attract less attention in comparison.

Consequently, Attardo (2002) conducted a survey on Logical Mechanism and brought up a taxonomy. Figure 2.2 is a list of all known Logical Mechanisms.

Role reversals Potency mappings Role exchanges

Vacuous reversal Chiasmus Juxtaposition

Garden path Faulty reasoning Figure ground reversal

Almost situations Self-undermining Analogy

Inferring consequences Missing link Reasoning from false premises

Coincidence Implicit parallelism Parallelism

Proportion False analogy Ignoring the obvious

Exaggeration Cratylism Field restriction

Metahumor Referential ambiguity Vicious cycle Figure 2.2 List of all known Logical Mechanisms. (Attardo, 2002)

A number of the Logical Mechanisms will appear in the present study. For instance, we may find humor resulting from coincidence, exaggeration, referential ambiguity, and juxtaposition in Friends. We can also find funny lines with garden path sentences, which leads to sarcasm; false analogy, most of which surrounds taboo topics; and role exchanges, which will be categorized into deviation from behavioral norm, in the jokes in Friends.

2.3 Linguistic strategies used in jokes

The main goal of the current study is to explore the linguistic strategies used in the funny lines in Friends. Therefore, in this section, we are going to review previous analyses of linguistic strategies used in jokes, such as Pepicello and Weisberg (1983)’s categorization, Deneire’s (1995) classification, and Dienhart’s (1999) continuum and classification. First, Pepicello and Weisberg (1983)’s categorization will be reviewed.

According to Pepicello and Weisberg (1983), linguistic ambiguity is the most frequently used linguistic strategy in jokes. They proposed a classification of linguistic strategies used in verbal humor. Their list is reproduced as follows.

1. Phonological

A. Lexical: Eg: What turns but never moves? Milk.

B. Minimal pairs: Eg: Sign on the gate of a nudist club in October: Clothed for the season.

C. Metathesis: Eg: What’s the difference between a midget witch and a deer fleeting from hunters? One’s a stunted hag, the other a hunted stag.

D. Stress /juncture: Eg: What bird is in lowest spirits? A bluebird.

2. Morphological:

A. Based on irregular morphology: Eg: What’s black and white and red/read all over? A newspaper.

B. Morphologically analyzed: Eg: What bow can no one tie? A rainbow.

C. Exploitation of bound morphemes: Eg: I must say you are looking couth, kempt, and shoveled today.

D. Pseudo-morphological (false analysis of the phonological sequences of one word into morphemes) Eg: What’s the key to a good dinner? A turkey.

3. Syntactic

A. Phrase structure: Eg: How is a duck like an icicle? Both grow down.

B. Transformational: Eg: What do you call a man who marries another man? A minister.

C. Idiom: What goes most against a farmer’s grain? His reaper.

D. Syntactic/ morphological homophony: Eg: Why can you not starve to death in the desert? Because of the sandwiches (sand which is) there.

4. Others

A. Presupposition: Eg: How many balls of string does it take to reach the moon?

One, if it is long enough.

B. Parody (Riddle parody): Eg: Why do elephants paint their toenails red? So they can hide in cheery trees.

Deneire (1995) also proposed his categorization of linguistic triggers in jokes. His classification is similar to Pepicello and Weisberg’s (1983), but differs in that

Pepicello and Weisberg listed “other” as a separate category, while Deneire listed

“lexicon” and “syntax+ lexicon” as separate categories. Deneire’s classification is illustrated as follows.

1. Phonology:

Eg: An American in a British hospital asks the nurse, ‘Did I come here to die?’

The nurse answered, ‘No, it was yesterdie.’

2. Morphology:

Eg: John Kennedy’s famous blunder in Berlin: “Ich bin ein Berliner” (“I am a jelly doughnut.”), instead of “Ich bin Berliner.”

3. Lexicon:

Homonymy, homophony, and polysemy are at the origin of most puns, and thus of classroom humor:

Eg: A: “Waiter, do you serve crabs here?” asks a customer.

B: “We serve everybody. Just have a seat at this table, sir.”

4. Syntax:

Eg: Student 1: “The dean announced that he’s going to stop drinking on campus.”

Student 2: “No kidding! The next thing you know, he’ll want us to stop drinking too.”

5. Syntax +lexicon:

Eg: Q: How do you make a horse fast?

A: Don’t give him anything for a while.

On the other hand, Dienhart (1999) claimed that the similarity in form (i.e.

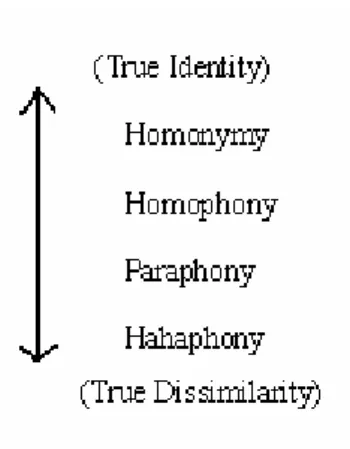

phonetic consonance) is crucial to the classification of linguistic triggers. Thus, he proposed a continuum with phonetic total identity at one end and phonetic true dissimilarity at the other, shown by figure 2.3:

Figure 2.3 Continuum of phonetic consonance

Homonyms are two words that are identical in form and in sound.

Eg: Why couldn’t the leopard escape from the zoo? Because he was always spotted.

Homophones are two words that have the same sound.

Eg: When is a boy like a pony? When he’s a little hoarse/horse.

Paraphony, refers to two words which are similar but not identical in phonological form.

Eg: What do cannibals have for lunch? Baked beings/beans.

Hahaphony refers to an artificial type of (near) homophony whereby similarity of sounds is produced by means of a kind of pseudo-morphemic analysis.

Eg: What did they give the man who invented the door-knockers? The No-bell prize.

While Deneire (1995)’s classification is a more simplified one, both Pepicello and Weisberg (1983)’s and Dienhart (1999)’s categorizations of linguistic strategies used in jokes are very systematic and comprehensive. In the present study of Friends, we also found lexical, pseudo-morphological, transformational, and presupposition types of linguistic triggers from Pepicello and Weisberg’s classification, and homophony, paraphony and hahaphony from Dienhart’s categorization. Note that while most of the examples in the three aforementioned classifications were

well-designed riddles, the funny lines in Friends were similar to natural conversation.

Such difference seems to indicate that Pepicello and Weisberg (1983)’s, Deneire (1995)’s, and Dienhart (1999)’s categorization of linguistic strategies can be applied to different genres of humorous texts.

2.4 Empirical studies

Previous studies on humor encompassed a wide variety of topics. For instance, Laurian (1992) and Antomopoulou (2004) explored the aspects of translation research and humor; Holmes and Marra (2002) analyzed subversive humor between colleagues and friends; Norrick (1993) focused on repetition in canned jokes and spontaneous conversational joking; Attardo, Eisterhold, Hay and Poggi (2003) conducted a

research on multi-modal markers of irony and sarcasm; Schmitz (2002) studied humor as a pedagogical tool in foreign language and translation courses; Oaks (1994)

concentrated his study on the structural ambiguity in humor; Bucaria (2004) analyzed lexical and syntactical ambiguity as a source of humor in newspaper headlines; Wang (1998) conducted a cross-linguistic experiment on Chinese students’ comprehension and appreciation of jokes in English and provided several suggestions for foreign language teaching and learning. Despite the diversity of the relevant literature on humor, this study reviews only linguistic studies on jokes and sitcoms.

2.4.1 Studies on Jokes

In this section, two studies are reviewed. The first one is Hung’s (2002) study of Mandarin cold jokes, which classified humor types into three main categories, compared the differences and the similarities between traditional jokes and the so-called cold jokes, and explored the characteristics of cold jokes. The second one is Tsai’s (1997) linguistic study of Chinese sexual punning jokes, which provided a

thorough analysis of different kinds of puns and taboo topics.

2.4.1.1 Hung’s study of Mandarin cold jokes

Hung’s (2002) study explored the types of humor employed in cold jokes in comparison with traditional jokes (i.e. well-formed, funny jokes), and examined the degree of joke well-formedness in these types of humor in order to account for why cold jokes strike one as ‘cold’.

Based on the Incongruity-Resolution Model reviewed in section 2.1, Hung (2002) divided jokes into three major categories: Metahumor, Nonsense Humor, and

Incongruity-Resolution Humor. Hung adopted Suls’(1983) definition and claimed that metahumor occurs in jokes that are considered humorous but do not possess an

incongruity structure. One example is as follows:

<4> ‘Have you heard the latest news?’ ‘No? Well, neither have I.’ (Attardo 1994) In this joke, there exists no incongruity, as it comes as no surprise that the logical or expected response to the question is either ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

Hung (2002) quoted Ruch’s (1992) definition and referred to nonsense humor as humor having a structure in which the punch line may (a) provide no resolution, (b) provide partial resolution (leaving an essential part of the incongruity unresolved), or (c) actually create new absurdities and incongruities. One example of nonsense humor with no resolution is illustrated by the following cartoon narration (Hung, 2002):

<5> Spectators at a sporting event cheer on the athletes in the

foreground, running a relay race. One athlete, holding a duck by the neck, hands it off to another athlete. The cartoon captioned ‘The duck relays.’

This cartoon does not make sense in the real world because runners in a relay race usually take a baton. Thus, the incongruity lies in the fact that the athletes are running with a duck rather than a baton. However, it does not provide a resolution to explain why a duck is used instead of a baton in this case. Therefore, this is an example of nonsense humor with no resolution.

The partial resolution type of nonsense humor can be explained by the following example:

<6> The bedroom of a pair of dragons: A picture of a fire-breathing dragon hangs over the headboard of a bed, slightly crowded with the two dragons underneath the covers, their heads and tails poking out from under the blankets. One dragon faces the other, propped up with its mouth closed and a look of embarrassment on its face. The other faces away, clutching the covers and saying, ‘I’m sorry Irvin…It’s your breath. It’s fresh and minty.’ (Larson, 1983)

In this example, the incongruity lies in the fact that in real world having a fresh and minty breath is usually considered a positive quality. Nonetheless, the dragon in the cartoon was embarrassed by his fresh and minty breath, and his lover apologized and implied that his fresh and minty breath turned her off and made her not want to have sex with him. However, this incongruity can be partially resolved by considering the fact that dragon’s world is supposed to be different from human’s world, as we can see from the picture of the fire-breathing dragon hanging over the headboard of the bed in the cartoon, which gives us a clue that a male dragon is supposed to have a fiery, maybe even smelly, breath rather than a fresh and minty breath. But this cartoon does not explain why these dragons share human characteristics. Thus, this is an example of nonsense humor with partial resolution.

A typical example of the nonsense humor which creates new incongruity is as follows:

<7> One day, a cat stole a fish from a shop in the market and was enjoying this delicious food. While the cat was about to leave, it was caught by the shop owner. The owner asked the cat to pay for the fish, but it didn’t want to. So the cat said, ‘I am the King of cats (Elvis Presley)’

Then, it thought to itself, ‘It’s strange. I am a cat, right? How can I talk?’

(Hung, 2002)

This Mandarin cold joke provides an incongruity by describing a talking cat, which is incongruous with the real world. However, at the end when the cat wonders

why it can talk, a new incongruity is created, which is contradictory to the fact that it did talk in the story.

Finally, Incongruity-resolution humor is characterized by having an incongruity structure, that is, a punch line, which can be completely resolved. The following example can be used to illustrate this type of humor:

<8> ‘Doctor, come at once! Our baby swallowed a pen!’ ‘I’ll be right over. What are you doing in the meantime?’ ‘Using a pencil.’

Using a pencil seems incongruous as it does not really answer the doctor’s question about ways to deal with the baby. The incongruity is resolved because the question ‘What are you doing in the meantime?’ also means ‘What are you using as a substitute for the pen?’

Hung’s (2002) study revealed that cold jokes made use of several types of humor:

meta-humor, nonsense humor, and incongruity-resolution humor, while traditional jokes employed only the humor of incongruity-resolution and partial resolution. Since sitcoms and jokes belong to different forms of humorous text, that is, the former belongs to the spoken form of the conversations and the latter belongs to the written form of the story, it comes as no surprise that the funny lines in sitcoms will

demonstrate different types of humor. The funny lines in sitcoms are expected to illustrate mostly incongruity-resolution humor since the funny lines have to corroborate with the plot line of the story. Without a resolution, the story cannot continue smoothly and the audience will be left puzzled.

2.4.1.2 Tsai’s analysis of Chinese sexual punning jokes

Tsai’s (1997) study analyzed sexual punning jokes used in Taiwan. According to Tsai, the most common linguistic humor is pun, and sexual puns are an everyday happening in language communication. He provided a taxonomy of puns: punning

jokes in which the pun is in the punch-line are called end-puns; those in which the pun appears in the build-up are called garden-path jokes; and those where no overt pun is provided are called implied punning jokes. In implied punning jokes, the hearer has to infer a pun from what he or she hears. In Tsai’s study, sexual punning joke was

defined as the text insinuating sexual behaviors and sexual organs. Issues of sex are rarely mentioned explicitly by people and regarded as a taboo in civilized societies.

However, from sex suppression to sex release, people may have a kind of pleasant sensation and they may burst into laughter. This is because taboo topics comprise the major stream of impulse people will normally try to control; therefore, it should come as no surprise that they fuel our gustiest laughter. The current study verifies this hypothesis by showing that jokes with taboo topics contributes to a high percentage of funny lines in Friends.

On the basis of Raskin’s script theory, Tsai divided sexual punning jokes into four types: the first type contains an overt sexual /nonsexual opposition with the unavailability of any specific sexual script for the joke. The second type contains an overt sexual /nonsexual opposition with a specific sexual script for the joke. Four kinds of binary distinction are often involved in this type: genital size, sexual prowess, sexual exposure, and sexual ignorance or inexperience. The third type is based on the implied sexual/ nonsexual opposition and an overt nonsexual opposition. And the

fourth type is characterized by a specific sexual opposition in explicitly sexual humor.

Tsai conducted three experimental studies and one survey. The result of

experiment one indicated that the violation of the Cooperative Principle decreases the funniness degrees of the joke. The result in experiment two showed that the properties of the sexual puns and their funniness degrees are positively correlated. In experiment three, the extroversion or introversion of the personality of the subjects made

significant differences in accepting explicit and direct sexual punning jokes, but

non-significant differences in accepting the implicit and indirect ones. The survey conducted on the university campus focused on two social variables: gender and age.

Tsai’s analysis took the perspectives of the speaker’s intentionality, which includes deceptive violations of the Cooperative principles, and the speaker’s entrapping of the hearer; and the acceptability of the hearer, which includes the intention to avoid unwelcome questions or to retort the speaker, to quibble about the speaker’s accusation, and to supply a seemingly possible explanation, often at the hearer’s own expense. He also listed the triggers in Chinese sexual punning jokes, including linguistic triggers such as regular ambiguity, quasi-ambiguity, figurative ambiguity, syntactic ambiguity, and situational ambiguity, and non-linguistic triggers such as social meaning devices and meaning association devices.

Based on Raskin’s (1985) humor act theory and Tsai’s(1997) taxonomy, the categorization in the present study on Friends will also adopt the perspectives of the speaker’s use of expressions, the hearer’s interpretation, and the hearer and speaker’s interaction.

2.4.2 Studies on sitcoms

Previous studies on sitcoms mainly focused on the sociolinguistic aspects. Here, we will review Bubel and Spitz’s (2006) study on the characterization of women through the telling of dirty jokes in Ally Mcbeal, and Paolucci and Richardson’s (2006) study on Seinfeld’s critique of American culture

2.4.2.1 Ally Mcbeal

Bubel and Spitz’s (2006) study on the characterization of women through the telling of dirty jokes in Ally Mcbeal analyzed an episode of the US sitcom Ally Mcbeal in which two women told dirty jokes. Their study showed that although the structure of both jokes as well as their respective performance equally met the

demands of good telling of jokes, the screenplay was constructed in such a way that one of them failed to elicit laughter. This was achieved through creating expectations in the audience before the telling of the jokes, and through having the two speakers structure their jokes in different ways. In this episode, while Ally set the wrong mood before telling her joke by challenging her audience, Rene established rapport with her audience. In addition, Ally’s uptight and prudish personality and Rene’s self-assertive and provocative characteristics also contributed to the failure of Ally’s joke

performance and the success of Rene’s.

Bubel and Spitz’s study also had implications for gender research. They analyzed three levels of the relationship between gender and humor. On the individual level, their study revealed that there is a continuum of human’s gendered practices: at one end, there is the stereotypical female who is not able to present and enjoy dirty jokes, illustrated by Ally’s character; at the other end, there is the provocative, tomboyish female displaying stereotypical male behavior who knows how to tell and appreciate dirty jokes, illustrated by Rene.

On the interactional level, the bar audience’s responses to the two joke telling were apparently both rooted in pre-existing gender stereotypes. Their positive reaction to Rene’s joke performance seemed to be grounded in her representing black woman Jezebel archetype while their negative reaction to Ally’s telling could be seen as a consequence of the pervasive stereotype of the humorless woman.

On the social structural level, the mediated humor of this episode reproduced dominant views of gender. Although Rene seemed to subvert the stock image of the humorless female in successfully telling a dirty joke in public, she corroborated another hypersexual, lascivious hedonistic and immoral stereotype of a black woman.

The failure of Ally’s attempt at telling a dirty joke more obviously reproduced stereotypical gender expectations.

Bubel and Spitzs also pointed out that television discourse is built around the insight that the interaction portrayed is designed to be overheard by the audience in front of the TV. That is to say, the model of television discourse is audience centered, and the mental processes in the viewers are taken as a starting point. Since the audience, like the over-hearers, are unlikely to fully share the participants’ common ground and they can not directly negotiate meaning with the participants, dialogues of sitcoms must be designed in such a way that the participants’ common ground is available to the audience in front of the TV, i.e., the audience has access to the underlying knowledge the utterances are based on. Therefore, the present study will be conducted based on the audience-perspective, rather than on the conversation participants’, i.e. the speaker’s and the hearer’s, point of view.

2.4.2.2 Seinfeld

Paolucci and Richardson’s (2006) study on Seinfeld’s critique of American culture showed that the US sitcom Seinfeld had often been considered as being non-political in nature. However, Paolucci and Richardson revealed the sitcom’s hidden critique of the rules dominating modern American society. Based on their study, humor in sitcoms not only functions to exhibit human foibles in such a way as to connect an audience to its humanness, it also specializes in indicating the

nonsensical nature of the institutional rules in American society. Paolucci and

Richardson stated that comedians have a role as licensed spokespersons who identify and discuss contradictions in society that other people may be unaware of or reluctant to acknowledge openly. They center on everyday life, asking questions about how its rules are negotiated. Thus, Seinfeld combines two forms: humorous commentary and an examination of often undiscussed aspects of everyday life. “Through its focus on social life and their misarrangement, it is possible to reveal how its social critique

pokes through official reality’s thin sleeve” (Paolucci and Richardson, 2006: 30).

Paolucci and Richardson pointed out that commentators on comedies had

traditionally understood it as a presentation of an unexpected departure from the norm where humor disturbs our definition of reality. They used incongruity theory to

explain this phenomenon, which focuses on the divergence between an unexpected and an actual state of affairs. The audience must understand the two realities involved to perceive the incongruity and get the humor. Comic discourse often plays with familiar meanings in a way where the setting often contains some sort of incongruity between expectations and the reality. For instance, Seinfeld often forces its audience to think about incongruous attitudes towards norms in daily life by making fun of its characters’ failure to negotiate the incongruities between social change and the norms that are supposed to guide social intercourse.

According to Paolucci and Richardson, the humor in Seinfeld rests on two concerns. The first one is the examination of how failures in controlling the situation often result in incongruous events, meanings coming out quite differently than expected, and a loss of normalcy in daily situations. The second one is the focus on how characters use what is called impression management to make themselves appear to have complied with social norms, despite their real intentions. The characters often play with meanings to create humor and to change the normalcy of the situations. In order to maintain familiarity across audience, comedy can play with generalized character traits, ordinary situations such as pursuing shallow relationships for sex or changing jobs for money, and social rules as its characters embarrass themselves and misread other’s intentions through “role reversals, funny actions, double meanings, word distortion, parody, and unexpected answers” (Paolucci and Richardson, 2006:

32). These strategies reveal “incongruities, unnoticed ironies, and contradictions in social life through constructing absurd situations, unexpected events, and exaggerated

or ironic conclusions of a plot line” (Paolucci and Richardson, 2006: 32). These techniques show us rarely discussed aspects of our social relationships.

As we can see from the review, previous studies on sitcoms mainly focused on the sociolinguistic aspects such as gender issues and critique of the American society, instead of the linguistic characteristics of the funny lines in the TV show, the present study takes the linguistic perspective and aims to investigate the linguistic strategies used in the funny lines in Friends.