Evaluating a Self-Access Learning

Project Utilizing DVDs

Guo, Siao-cing

Abstract

Given the fact that students vary greatly in terms of learning styles, language levels, and studying time, it seems that the best way to improve students’ English is through a learning environment with resources that interest students and help students become autonomous learners. Many studies reveal that modern technology of media and DVDs of films provide an intriguing learning experience for students (Luo, 2003; Murray, 2005; Stempleski, 2003). This paper presents a student self-access learning project, designed for non-English majors, using DVDs of a popular American sitcom. The design, implementation, problems encountered, and students’ learning results are explored. The students’ feedback from the project showed positive results. Participating students expressed a great interest in the DVD materials and found great improvements in comprehension after viewing the episodes with subtitles. The self-access learning project complements classroom teaching and enables students to learn at their own pace.

Keywords: self-access learning, learner autonomy, learning motivation, English materials

I. INTRODUCTION

English instruction in Taiwan has been an important part of the curriculum throughout junior high school, senior high school and into the first years of university. However, the years of stifle English instruction have failed to develop students’ communicative competence and also unfortunately diminished their interest in and quest for English. Teacher-centered and book-centered approaches dominated the classroom in the past and unfortunately retain their popularity today because teachers and students are most accustomed to these traditional teaching methodologies. These traditional ways of teaching with a focus on teaching about language not teaching to use language obviously do not work toward improvement of learner’s communicative ability or development of learning motivation. To improve learning results, English practitioners continue searching for models for improvement (Ha & Huong, 2009). That includes giving serious thought to the needs of students who vary greatly in terms of learning styles, language attainment levels, and available study time. The best way to improve students’ English is through a learning environment that engages and stimulates students’ minds, including resources that allow students to learn autonomously.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

1. Learning Resources & the Use of Technology

Moreover, English instructions do not have to be limited to classrooms (Chu, 2009; Guo, 2011). Most college non-English major students in Taiwan receive no more than two hours a week of English instruction in their freshman year. Some schools may demand additional instruction time. When students leave the English classroom, they probably receive little or no exposure to English. The current EFL settings are not sufficient for English exposure and practice for students (Xiao & Luo, 2009); therefore, researchers suggest utilizing TV programs or DVDs to achieve curricular goals (Perry & Moses, 2011). Thanks to the flexibility and availability of today’s technology, learning can happen after school and beyond classrooms. Teachers can make good use of technology and incorporate technology in planning their courses.

2. Motivation

Research and empirical evidence has shown that interesting materials have a positive effect on learners’ motivation (Gardner & Miller, 2010; Scacco, 2007). Motivation is commonly described as the inner pulse, emotion, or desire that drives a person to a particular action (Brown, 1994). Motivation is correctly understood to be of critical importance in the continuing performance of all learned responses; that is, a learned behavior will not occur unless it is energized (Huitt, 2001). D. Brown (1994), refers to two types of motivation i n second language acquisition as identified by Gardner: instrumental motivation and integrative motivation. Instrumental motivation refers to the desire to learn the language as a means to attain goals such as passing tests or advancing in one ’s career. On the other hand, integrative motivation refers to the desire learners have to identify themselves with the target culture or to assimilate to that culture. Integrative motivation is understood by some theorists as the kind of motivation that leads to student’s high language proficiency, but others hold opposing views and argue that instrumental motivation plays a more significant role in the EFL setting (Makarchuk, 2005; Warden & Lin, 2000). Whether one agrees with the integrative or instrumental construct, there is no doubt that motivation in one form or another contributes to success in learning. Littlewood (1984) asserts that motivation is a critical force that drives learners to the task and determines their level of dedication and persistence. Thus teachers should develop techniques to elevate learners’ motivation and better yet retain that motivation (Cheng & Dörnyei, 2005). English teachers need to carefully design and select materials and tasks that stimulate learning interest and promote language learning.

III. THE SELF-ACCESS LEARNING PROJECT

which the enhancement of English capability is a primary goal (Chung, 2006). Many universities in Taiwan utilized grants from the Ministry of Education and established self-access learning centers to promote foreign language development. Implementing self-access learning “enhances language-learning opportunities and provides learners with the independent learning skills to continue learning language” aside from formal learning (Gardner & Miller, 1999). According to Pang, Zhou, and Fu (2002), institutions can organize self-access centers and after-school activities into better learning environments. Many universities around the world have already established self -access learning center, and Taiwan has followed suit (Cheng & Lee, 2008). According to Hsu and Wu (2010), among 93 universities and colleges, 71 schools (76%) have set up a self-access learning center or provided self-access resources for students by the year of 2009. That was also what this present researcher along with other English teachers did at the university where this current study was conducted. The self-access learning project was one of the subprojects granted to this technical university by the Ministry of Education (MOE) in Taiwan.

The subsidy from the MOE in the year of 2003 was first used to set up a multimedia Self-Access Center (SAC). Following the establishment, the center purchased various language materials in four skills as well as pronunciation a nd grammar. To increase students’ participation and the center’s usability, language learning materials with entertainment value offered the most appealing options. In 2005 and the following years, a large portion of the MOE funding has been allocated to the purchase of films and TV series on DVDs. A number of Oscar award winning films and classic movies were acquired for the enhancement of the media library. Popular situation comedies like Friends also caught teachers’ attention and were added to the media library collections at the center.

Friends series was one of the all-time favorites for several reasons. First of

an understanding of American culture. In addition, each episode of the sitcom lasts only around 25 minutes. Within one hour, students can view an episode twice. Multimedia technology integrating real-life situations with the target language helps students learn language more effectively (Harji, Woods, & Alavi, 2010). The visual images of the DVDs make the language meaningful to language learners and reinforce understanding (Rucynski, 2007). Through DVD viewing, students can enjoy the show and learn the language at the same time. In one relevant study, as the attendance at the self-access center increased, the researcher became interested in learning how students reacted to this self -access learning project and examining the impact of DVD viewing on students ’ language enhancement and learning experience.

IV. METHODOLOGY

1. Instruments

Three measurements were administered to investigate the effects of students learning via DVDs of Friends episodes as well as students’ attitudes toward this self-access learning project: 1) a comprehension test, 2) a survey with an open-ended question, and 3) a likert type survey.

2. Participants

There were 323 visits by the students who were all non-English majors. First-to-third year students participated in this self-access learning project. The first-year students from the two-year college also took part in this study. Some students visited the center several times and took the test and the survey more than once, although they were advised to take the survey and the test just one time. The frequency of visits by the same individual was not recorded.

At the first stage, a total of 300 comprehension tests were collected. Among them, 21 were from freshmen, 157 were from sophomores, and 104 were from first year students of the two-year college. At the end of the term, 222 questionnaires regarding students’ feedback toward the project were also collected. Among them, 191 were usable. At the second stage, 168 surveys were collected. Among them, 159 were usable.

3. Procedures

V. RESULTS

1. First Stage

The results of the comprehension tests showed that most of the participants did well after viewing one or more episodes of Friends. Out of 100 points, 88.9% of the first-year students from the two-year college scored above 60. Among the four-year college students, 57.1% were the freshmen students; 75.2% were the sophomores; 59.6% were juniors. It showed that students had a good understanding of the content and language from the episodes. Since the researchers did not conduct a pre- and post-test on their comprehension, it can not be inferred how much progress students may have made as a result of learning from DVD viewing.

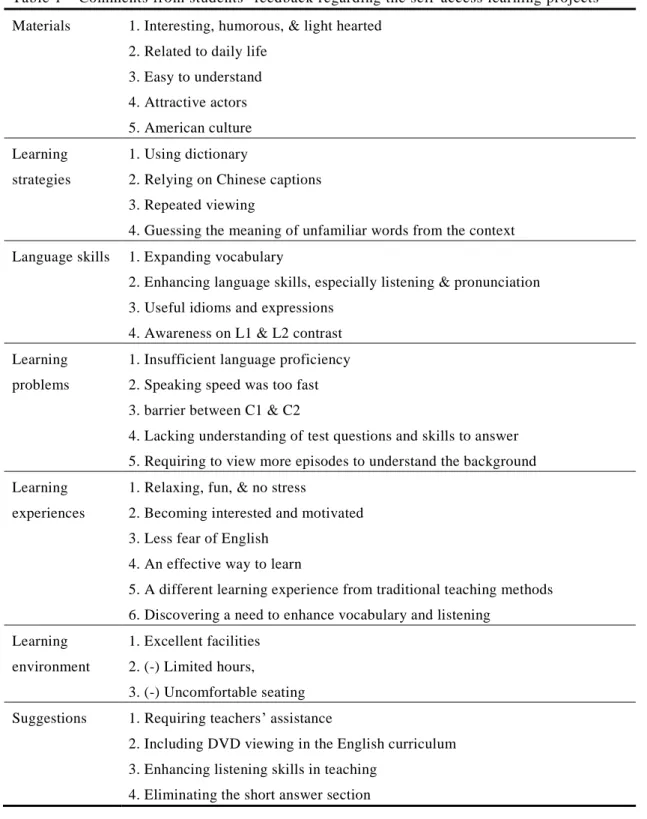

Students’ feedback on this self-access learning project using DVDs of

Friends episodes yielded very positive results. Among 191 questionnaires from

the participants, the majority expressed positive experiences whereas only four indicated negative experiences. The feedback from the students toward using sitcoms for self learning was categorized into seven areas: materials, language

skills, learning experiences, learning strategies, learning problems, tim e and facilities, and suggestions (See Table 1).

Table 1 Comments from students’ feedback regarding the self-access learning projects Materials 1. Interesting, humorous, & light hearted

2. Related to daily life 3. Easy to understand 4. Attractive actors 5. American culture Learning strategies 1. Using dictionary

2. Relying on Chinese captions 3. Repeated viewing

4. Guessing the meaning of unfamiliar words from the context Language skills 1. Expanding vocabulary

2. Enhancing language skills, especially listening & pronunciation 3. Useful idioms and expressions

4. Awareness on L1 & L2 contrast Learning

problems

1. Insufficient language proficiency 2. Speaking speed was too fast 3. barrier between C1 & C2

4. Lacking understanding of test questions and skills to answer 5. Requiring to view more episodes to understand the background Learning

experiences

1. Relaxing, fun, & no stress

2. Becoming interested and motivated 3. Less fear of English

4. An effective way to learn

5. A different learning experience from traditional teaching methods 6. Discovering a need to enhance vocabulary and listening

Learning environment

1. Excellent facilities 2. (-) Limited hours, 3. (-) Uncomfortable seating Suggestions 1. Requiring teachers’ assistance

2. Including DVD viewing in the English curriculum 3. Enhancing listening skills in teaching

4. Eliminating the short answer section * (-) indicates a negative comment

the program Friends certainly fulfills that guideline. Watching DVDs of American sitcoms also allow students to observe some aspects of American cultures and compensate for a lack of access to the target culture (Bureno, 2009; Wang & Liu, 2011). Culture should be integrated into the teaching of the English language (Byram & Risager, 1999; Kachru, 1999; Rucynski, 2007). Second language teachers can broaden students’ perspectives and help students understand themselves and others (Lafayette, 1993). Students not only learned language usage and expressions, but they also learned the cultural aspects of that language including values, beliefs, and customs.

The second highest number of comments addressed language skills. A total of 134 comments refer to the language skills acquired. Students felt that they learned a great deal of language from participating in this self-access learning project via DVDs. Among the skills students felt had been learned or improved were: vocabulary, listening, speaking, pronunciation, reading and writing, (listed according to student-ranked importance). Students identified vocabulary including idioms and useful expressions as the one area in which they learned the most. This was followed by listening skills. Since during this study, students were not asked to interact or speak the language, the speaking component here is interpreted to mean expressions and sentence structures they could use for daily communication. Reading is interpreted to mean their understanding of captions and the test questions; the writing part is interpreted to refer to the sentence writing they had to do for the comprehension test. Another area students felt they improved upon was the awareness of the contrast between American culture and their native culture.

fun.”

The fourth highest number of comments (62) was in regard to learning strategies. Students who participated in this project had to rely on themselves to accomplish the required tasks including comprehending the episode and answering the comprehension test. Since there was almost no instruction or assistance provided, students incorporated strategies to support their individual learning needs. The most frequent strategy utilized was viewing the episodes in both languages, which was suggested to them. Most of them indicated that their English was too limited to acquire a high level of understanding; hence, they had to rely on their native language. Moreover, it was time efficient for students to do the second viewing in L1. Other frequently used strategies were guessing and viewing repetitively. Since each episode has its context, students often guessed the meaning of words based on what was happening, the actions, and facial expressions. Students also view a particular part many times to help them acquire the language. In addition, they relied on their English -Chinese dictionary for unfamiliar words.

In addition to materials, learning skills, strategies, and experiences, the re were 43 comments revealing the problems students encountered. The number one problem was their insufficiency in vocabulary words and listening ability. Students mentioned that it required a higher level of English in order to accomplish this project more effectively. The second problem was the complexity of the materials. Each of the six main characters in the series has his/her own clan and friends with whom s/he is involved. Students felt that they needed to watch a few more episodes to be familiar with the characters and the story line. They also lacked an understanding of American humor as different cultures have their own presentations or interpretations of humor (Roell, 2010). The other problem had to do with the test design. A few students complain ed about the difficulty of the test. They could easily understand the plot with visual clues and especially if they had watched it in L1, but some of them had trouble understanding the test questions, which might have resulted from their low English proficiency.

earphones and seats. One student said that it would have been nicer if they had been able to watch the sitcoms from their living room couch. What worked best for the students was that they could view videos at a time that was convenient for them and at the rate they preferred. A couple of students appreciated the helpfulness of the part-time student working as a lab assistant.

Students also brought out a few suggestions. Ten students found this project interesting and effective and specifically suggested this method be included as a formal curricular activity. Some preferred some instruction in vocabu lary prior to viewing and an explanation of the test questions. A few students suggested eliminating short answers and keeping the true and false section and multiple choices. Some students thought it would have been better if there were no tests at all.

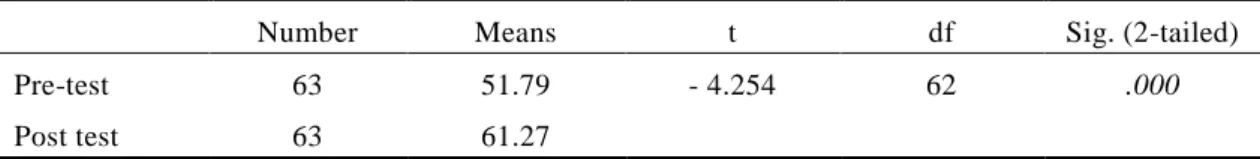

2. Second Stage

The second part of this study consisted of the pre- and post-comprehension test and a likert-scaled survey. A total of 63 students completed both pre- and post-test of the comprehension questions regarding the episode they watched. The means score from the pre-test was 50.79 and the post-test was 61.27 out of 100. The results of the t-test comparing the pre-test and the pos-test can be found in Table 2. It shows a significant difference in their test scores between the first viewing with no subtitles and two or several viewing with subtitles. The results indicated that students made a considerable improvement on their comprehension toward the content of the episode. The significance here is not on the rising test score. The purpose of this self-access learning project is not to boost testing results but to increase the opportunities for English exposure and self learning.

Table 2 Means comparison of the pre-test and post test

The first part of the likert-scaled survey was the background information about the participants. Of a total of 168 surveys collected, 159 were usable. Among the survey participants, 64 were male and 93 female. All four years of students participated in the survey studies, among them, 31 freshmen, 114 sophomores, 12 juniors, and 1 senior. The junior and senior parti cipants probably took part in order to pass their English courses, a requirement for graduation. Students were asked about their English grades from the previous semester. The results show that out of 100 points, only about 32% of students reached grades higher than 70 whereas 68% of them scored lower than 70. Nearly 29% of them failed their previous English course. The results demonstrate students’ low English proficiency. As for their reasons for participating in this project, participants could choose multiple answers such as grade bonus, interest in the TV programs, help in English improvement, curiosity, prior experience in using the self-access center, and others. The results made it manifest that most of them came in for the grade bonus for their Engl ish course, followed by interest in the TV program, help in English improvement, prior experience with the SLC, and curiosity. A couple of students indicated another reason, which was to come in for a laugh.

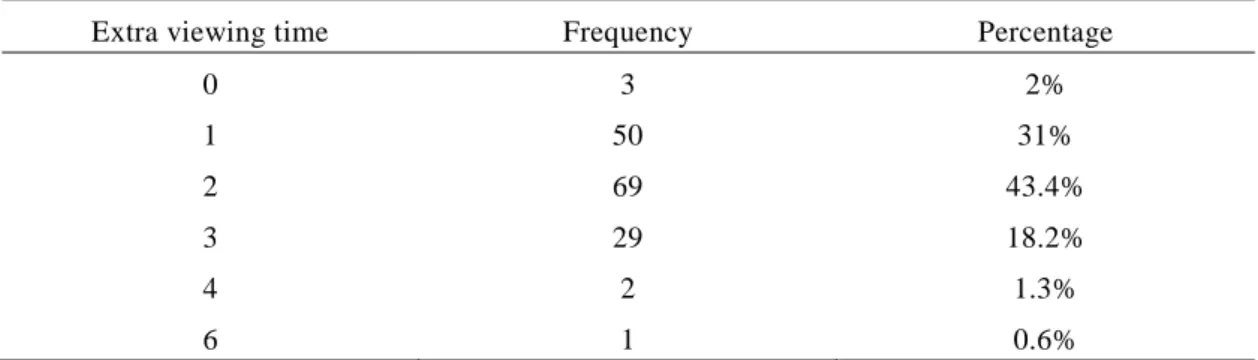

When asked about the extra times they watched the episode after the first viewing, the highest frequency was 6 times. A majority of them (62%) watched an additional 2-3 times whereas 31% watched just one more time, and only 2% did not watch a second time (See Table 3). The results show an incredible amount of effort students put into this learning task. Repeat viewing not only enhances clarity but also reinforces the language students acquire from the episodes. The opportunity for the second comprehension test fosters further and greater learning.

Table 3 The frequency and percentage of extra episode viewing times

Extra viewing time Frequency Percentage

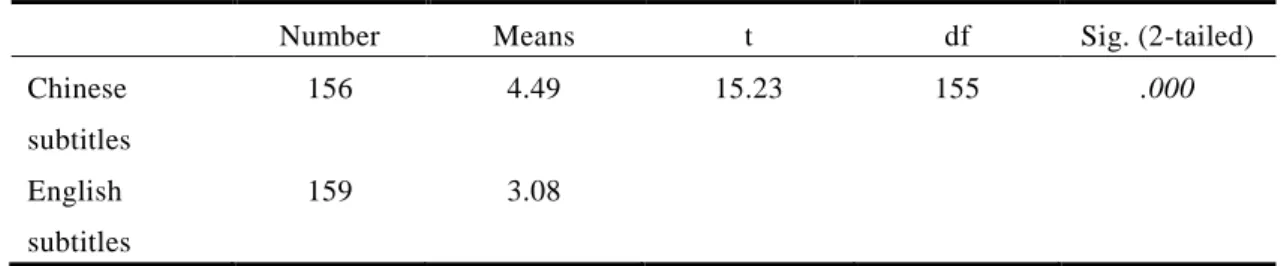

The language in the Friends episodes, aimed for American audience, is not tailored for students of other languages; nevertheless, students were asked to first watch the episode in the target language without any subtitles so that they did not rely on written language or translation. However, after the first viewing, students could watch it with English subtitles or Chinese subtitles. In the questions regarding their comprehension with or without subtitles, the likert scale value 1 indicates less than 10% comprehension, 2 indicates 11 -30%, 3 means 31-50%, 4 indicates 51-70%, and 5 represents over 70%. According to the survey results, viewing the episode without any subtitles posed a challenge to our students (M= 2.41), which means they only understood less than 30%. On the other hand, the mean score roared to 4.49 after they watched it with Chinese subtitles, which represents over 70% of understanding (See Table 4).

Table 4 Means comparison of comprehension with no subtitles and Chinese subtitles

Number Means t df Sig. (2-tailed) No subtitles 159 2.41 -20.89 155 .000 Chinese subtitles 156 4.49

Table 5 Means comparison of comprehension with Chinese subtitles and English subtitles Number Means t df Sig. (2-tailed) Chinese subtitles 156 4.49 15.23 155 .000 English subtitles 159 3.08

Table 6 Means comparison of comprehension in expression with Chinese subtitles and English subtitles

Naturally students’ comprehension with L1 would be higher than with L2. In terms of the content of the episode, there is a significant difference in students’ comprehension with Chinese subtitles (M=4.49) and with English subtitles (M=3.08) and also their comprehension in language usages (See Table 5 & 6). Even with English subtitles, students could infer the story line and grasp the gist of the plot by visual clues such as facial expressions. Herron, Hanley and Cole (1995) contend that visual support in the form of descriptive pictures significantly enhances comprehension. Although the statistical significance of the use L1 or L2 subtitles is not that important in this case, the underlined message is that students at a lower level need to be aided by supporting materials. The use of subtitles adds to the improvement of comprehension and results in the retention of learning interest. Students’ choice of language subtitles will increase their enjoyment and eventually contribute to language learning.

VI. PROBLEMS AND SUGGESTIONS

At the earliest stage, some problems emerged while implementing this project. In order to encourage students’ voluntary participation in this self-access learning project, all English teachers announced this project in their classes. Promotion ads were also written on the board in the classroom, and posters could be seen around the campus. However, the attendance rate was far from satisfactory. Similar results of a low turn-out rate were also reported by teachers at Japanese universities in Heath’s study (2007) on the use of self-access learning facilities. A few weeks passed after the implementation of the project, and there was no sign of the “crowd”. When asked why students didn’t visit the SAC, many of them mentioned that they didn’t like the test part. Another reason for a low turn-out rate was that students were all non-English majors. Although they recognized the important role English played in their future careers, they did not see an immediate need to improve their English.

However, based on the results from students’ feedback, this stimulating learning experience has motivated them to continue visiting the center and viewing more DVDs. If they had not come to the center for the class requirement or an incentive, they would not have had this experience to begin with.

As the number of students who came to watch the sitcoms increased, problems about the test questions and other elements of the study emerged. Some students, especially those who were at low proficiency level and came for extra points, were discouraged by the testing part of the project, especially if they failed the test. The biggest problem they faced was an inability to understand the test questions even after they checked the dictionary. The problem usually occurred when they read articles in their textbooks. Of the three types of test questions—true or false, multiple choices and short answers, more than 95 percent of these students complained about the short answers. They found themselves incompetent in comprehending and answering those questions. Quite a few students chose to answer the questions in their native language—Chinese. Many students also relied heavily on Chinese captions, which took away their English learning opportunity. However, for lower level students, some help from L1 may reduce their frustration and keep them on task. What teachers should be aware of when assigning work like this is to ascertain at some point students’ production in L2 whether in a written or an oral form.

Other problems included the complexity of plots and lack of cross culture understanding. Students tended to get confused with the characters and their relations with one another. This problem could be eliminated as they watched more episodes and got better acquainted with the roles in the sitcom. Culture barriers were another problem students mentioned in their feedback. Rucynski Jr. (2011) mentions American TV series as a rich source for cultural learning but at the same time, an obstacle too (also see Scacco, 2007). Students often were not aware of the humor the playwrights intended to convey. Some of the humor was so subtle and culture-oriented that people who had not been immersed in American culture long enough could not catch the gist of it.

during class or outside of class. Some of them even tried to find out ways to download the episodes from the Internet. Quite a number of students kept coming for viewing even though the deadline for them to get extra points was passed. Another interesting finding was that other than the expected language skill, listening, many students thought watching Friends DVDs also benefited them in vocabulary, reading, and pronunciation. In regard to learning new words, one student wrote, “I don’t have to check the dictionary. I could guess the meaning of a word from the facial expressions and body languages of the characters or from their conversation.” The strategy, learning a word from context, which is normally used in reading practices, could be applied to viewing the sitcom as well. Additionally, a few students also spoke of the skills and knowledge they obtained beyond language, for instance, culture difference, interpersonal relationship and contrast between genders.

Another significant finding was that, despite almost half of the participants participating for extra points, in their feedback only two mentioned the incentive as the main reason for their visit in the feedback. They not only enjoyed the DVDs but also learned a great deal from viewing it.

The purpose of the project implemented at the self-access center was to expose students to English by utilizing media facilities and DVDs with episodes from a sitcom. The last thing the researcher wanted to see was that the participants were scared away by the test questions as one of the complaints among the participating students. The comprehension test can be renamed as a comprehension check list or worksheet to reduce anxiety from a test. Different types of exercises such as character relationship diagrams and time lines for major events can be included instead of traditional multiple choice and true or false items.

Teachers can also utilize the latest technology to facilitate language acquisition. Well-equipped facilities are of the utmost importance as Gardner and Miller point out, “attractive technology, furnishings and services” in a self-access center are contributors to student motivation for utilizing these facilities (2010, 167).

VII. CONCLUSION

REFERENCES

Brown, H. D. (1994). Principles of language learning and teaching. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Bureno, K. (2009). Got film? Is it a readily accessible window to the target language and culture for your students. Foreign Language Annals, 42(2), 318-339.

Byram, M, & Risager, K. (1999). Language teachers, politics and cultures. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters LTD.

Cheng, H. F. & Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The use of motivational strategies in language instruction: The case of EFL teaching in Taiwan. Innovation in Language

Learning and Teaching, 1(1), 153-174.

Cheng, W. W., & Lee, M. L. (2008). Student perspectives of self-access in a multimedia English learning center. Journal of Organizational Innovation,

1(1), 89-105.

Chu, S. C. (2009). The use of computer technology in language classroom.

Foreign Languages and Literature Studies, 115-127. National Taipei College

of Business.

Chung, K. P. (2006). Promoting academic excellence at universities.

Technological and Vocational Newsletter, 171.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (2010). Beliefs about self-access learning: Reflections on 15 years of change. SiSAL Journal, 1(3), 161-172.

Gardner, D., & Miller, L. (1999). Establishing Self-Access: From Theory to

Practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Guo, S. C. (2011). Impact of an out-of-class activity on students’ English awareness, vocabulary, and autonomy. Language Education in Asia, 2(2), 246-256.

Ha, N. T., & Huong, T. T. (2009). A study of EFL instruction in an educational context with limited resources. CamTESOL Conference on English Language

Teaching: Selected Papers, 5, 205-229.

37-42.

Heath, R. (2007). Jump-starting students’ motivation to use self-access facilities in high-anxiety learning environments. Kanda Journal, 19, 171-188.

Heinich, R, Molenda, M, Russell, J. D., & Samldino, S. (1999). Instructional

Media and Technologies for Learning. Prentice Hall, Inc.: New Jersey.

Hill, C. (2003). Assessing students in a digital age. The Twelfth International

Symposium and Book Fair on English Teaching, 65-80. Taipei: Crane

Publishers.

Herron, C, Hanley, J., & Cole, S. (1995). A comparison study of two advance organizers for introducing beginning foreign language students to video .

Modern Language Journal, 79(3), 387-394.

Hsu, J. J. & Wu, C. T. (2010). A primary study of practice and management of self-access foreign language learning centers: case study of Southern Taiwan University. Journal of Southern Taiwan University, 35(2), 53-72.

Huitt, W. (2001). Motivation to Learn: An Overview. Educational Psychology

Interactive. Retrieved February 5, 2007, from

http://www.chiron.valdosta.edu/whuitt/col/motivation/motivate.html

Ishihara, N., & Chi, J. C. (2004). Authentic video in the beginning ESOL classroom: Using a full-length feature film for listening and speaking strategy practice. English Teaching Forum, 42(1), 30-35.

Kachru, Y. (1999). Culture, context, and writing. In E. Hinkel (Ed), Culture in

second language teaching and learning, 75-89. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Kellner, D. (2005). The changing classroom: Challenges for teachers. THE

Journal. Retrieved March 25, 2005 from http://www.thejournal.com.

Lafayette, R. C. (1993). Subject-matter content: what every foreign teacher needs to know. In G. Guntermann (Ed), Developing language teachers for a

changing world (pp. 124-158). Lincolnwood, IL: National Textbook

Company.

and Book Fair on English Teaching/Fourth Pan Asian Conference, 449-450.

Taipei: Crane Publishers.

Lin, H. C., & Lee, Z. H. (2003). Practical instructional technology development for teachers. The Twelfth International Symposium and Book Fair on English

Teaching, 459-466. Taipei: Crane Publishers.

Littlewood, W. (1984). Foreign and Second Language Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lo, M. L., Wang, D. C., & Hsia, C. S. (2005). A investigation on English learning motivation of the second-year students at a five-year college. Proceedings of

2005 Conference in ELT at Technical Colleges and Universities, 15-30.

Taipei: National Taiwan University of Science and Technology.

Luo, Chia-chen. (2003). Using DVD films to enhance college freshmen’s English listening comprehension. The Twelfth International Symposium and Book

Fair on English Teaching, 103-111. Taipei: Crane Publishers.

Makarchuk, D. (2005). Integrative motivation and EFL learning in South Korea.

The Korea TESOL Journal, 8(1), 1-25.

Murray, Denise E. (2005). Teaching for learning using new technology. The

Fourteenth International Symposium and Book Fair on English Teaching.

Taipei: Crane Publishers.

Pang, J., Zhou, X., & Fu, Z. (2002). English for international trade: China enters the WTO. World Englishes, 21(2), 201-216.

Perry, K. H., & Moses, A. M. (2011). Television, language, and literacy practices in Sudanese refugee families: “I learned how to spell English on Channel 18.” Research in the Teaching of English, 45(3), 278-307.

Rucynski, Jr., J. (2011). Using The Simpsons in EFL classes. English Teaching

Forum, 49(1), 8-17.

Rucynski, Jr., J. (2007). Cross-cultural understanding in the Japanese EFL classroom: Beyond natto. In K. Bradford Watts, T. Muller, & M. Swanson (Eds.), JALT 2007 Conference Proceedings, 808-819. Tokyo: JALT.

Scacco, J. (2007). Beyond Film: Exploring the content of movies. English

Teaching Forum, 45(1), 10-15.

Stempleski, S. (2003). Integrating video into the class curriculum. The Twelfth

International Symposium and Book Fair on English Teaching, 134-142.

Taipei: Crane Publishers.

Teeler, D., and Gray, P. (2000). How to use the Internet in ELT. Essex, England: Longman.

Wang, K., & Liu, H. (2011). Language acquisition with the help of captions. Studies in Literature and Language, 3(3), 41-45.

Warden, C.A., & Lin, H.J. (2000). Existence of integrative motivation in an Asian setting. Foreign Language Annals, 33(5), 535-547.

Wu, H. Y. (2002). Teaching techniques that keep university students interested in English learning. Selected Papers from the Eleventh International Symposium

on English Teaching/Fourth Pan Asian Conference, 565-571. Taipei: Crane

Publishers.

Xiao, L., & Luo, M. (2009). English co-curricular activities: A gateway to developing autonomous learners. CamTESOL Conference on English