CHAPTER FIVE: DISCUSSION

This chapter discusses results based on the analyses of the writing sections in the three textbook series and the semi-structured interviews.

Discussion of the Instructional Variables in the Three Series

This section discusses the major results regarding the focuses of instruction in the three series, the textbook authors’ underlying beliefs, and several phenomena that emerged in a cross-examination of these instructional focuses.

Instructional Focuses and Underlying Composition Pedagogies

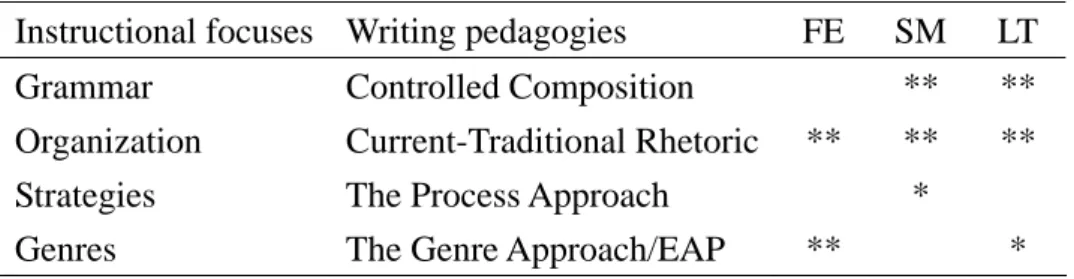

The current study explored the writing sections in three senior high school English textbook series. The four instructional variables identified in the three series represented pedagogical manifestations of the four prominent pedagogies reported in the history of ESL writing, i.e. Controlled Composition, Current Traditional Rhetoric, the Process Approach, and the Genre Approach/EAP. These instructional focuses

could then be mapped onto the writing pedagogies the three series each reflected, as summarized in Table 23.

Table 23. Writing Pedagogies in the Three Textbook Series

Instructional focuses Writing pedagogies FE SM LT

Grammar Controlled Composition ** **

Organization Current-Traditional Rhetoric ** ** **

Strategies The Process Approach *

Genres The Genre Approach/EAP ** *

Note.

** = major focus; * = secondary focusAs suggested in Table 23, the four pedagogies surfaced in the three textbook

series in varying degrees to guide and shape their instructional focuses. Each series

was found to recycle two or more of the four instructional orientations salient, or once

salient, in ESL composition history. The FE series was characterized by an almost

exclusive focus on rhetorical organization and genres. The SM series, on the other

hand, focused mainly on grammar and rhetorical organization, and gave some weight to writing strategies. The LT series also laid particularly heavy emphasis on grammar and rhetorical organization and yet, unlike the SM series, had its third focus placed on genres rather than strategies. Evidently, each series featured multiple focuses adopted from different instructional approaches.

The implementation of a compound approach appears to suggest that the writers of the three series are aware of the existing writing pedagogies in the ESL discipline.

It also implies that they are cognizant of the potential inadequacies of relying on one single approach to writing instruction. In other words, writing instruction, to these textbook writers, entails teaching different components of writing.

Textbook Writers’ Underlying Beliefs About Writing Instruction

The multiple focuses of each textbook series and their sequence, furthermore, reveal the authors’ underlying beliefs about what constitutes good writing instruction.

The FE series’ emphasis first on paragraph structure and later on genres indicates an attempt to introduce the structural elements of a paragraph as a rhetorical basis for preparing learners for their acquisition of genres. This arrangement suggests that the authors of the series believe that students need to acquire the structure of a paragraph before ultimately performing various communicative functions (i.e. genres).

The SM series, on the other hand, familiarized learners initially with basic paragraph structure and then with a range of linguistic constructions. Following this, different text types were presented to introduce rhetorical possibilities for organizing a paragraph. To the authors of this series, learning to write appears to be a process of mastering basic paragraph structure and various grammatical patterns, followed by the development of the ability to construct different text types.

In addition, the SM series, different from the other two series, gave much greater

emphasis to invention and editing strategies. This strategic emphasis seems indicative

of the textbook writers’ belief that aside from linguistic and rhetorical forms, it is necessary to equip students to generate ideas for drafting and eradicate errors in written products. Researchers (e.g. Silva, 1990) have highlighted the need, however, for learners to postpone treating linguistic errors to smooth their drafting process. In the SM series, unfortunately, no effort was made to train students to delay error treatment. As a result, students might end up focusing on error correction throughout, and this might impede the efficiency of their composing process.

Finally, as shown in Chapter Four, the LT series started with various grammatical patterns, and then proceeded directly to several paragraph writing tasks

14. Next, it presented certain genres and text types before dealing with the basic structure of a paragraph and, finally, introduced some more genres and text types. This sequence suggests that learning to write, in the view of the LT textbook authors, first entails creating a preliminary linguistic basis. It then involves attaining communicative goals by means of various genres, and familiarizing students with basic paragraph structure and different text types.

As has been noted, in the LT series, several writing tasks, genres, and text types were presented before a formal introduction to paragraph structure. This arrangement can be problematic in that knowledge of the elements of a paragraph, to the authors, does not seem to be a prerequisite for approaching writing tasks or acquiring text types and genres. In other words, linguistic patterns, in their opinion, are more

important as a basis for writing than a rudimentary knowledge of paragraph structure.

In sum, the textbook writers’ differential adoption of instructional focuses revealed their different beliefs about the optimal way to teach writing. For the FE textbook writers, learning to write seems to entail learning paragraph structure for the purpose of performing different communicative functions. To the SM textbook writers,

14

These were paragraph writing tasks that stood alone without following any preceding instruction.

developing one’s writing ability appears to be a process of mastering paragraph structure, consolidating a linguistic basis, and learning various text types along with invention and editing strategies. The LT textbook writers seem to believe that writing instruction starts with building a preliminary linguistic basis and continues with the learning of basic paragraph structure, genres, and a range of text types.

Cross-Examination of Instructional Focuses

A cross-examination of the focuses of the three series revealed several important phenomena, including the dominance of rhetorical instruction, general neglect of strategy training, controversy over grammar instruction, and differential impacts of the genre approach.

Dominance of the Rhetorical Approach

In the present study, Current Traditional Rhetoric was found to be the most dominant approach. This appears to suggest that the central concern of the authors of all three series was “the composed product rather than the composing process” (Silva, 1990, p. 13). This finding is congruent with Silva’s (1990) observation of the

continuing influence of the rhetorical approach as reflected in myriads of well-known ESL writing textbooks.

The effects of this emphasis in the three series on rhetorical forms, however, can be far-reaching. Given EFL teachers and students’ heavy reliance on textbooks (Kulm, Roseman & Treistman, 1999), the textbook authors’ underlying assumptions can exert a direct impact on teaching and learning outcomes. The three series may hence direct teachers and students to view writing essentially as a process of “identifying,

internalizing and executing” predetermined rhetorical forms (Silva, 1990, p. 14).

Under this instructional framework, meaning does not seem to determine form. Rather,

it appears to be shaped in conformity to form. Students may just consolidate their

manipulation of paragraph elements and discourse patterns but neglect their actual

experiences and personal meanings (Hyland, 2003).

Several observations regarding rhetorical instruction merit further discussion.

First, compared to the other two series, the FE series’ treatment of paragraph structure appears relatively brief and rough in that it merely serves as a basis for the subsequent focus on genres. Moreover, the FE series gave very limited attention to text types.

Due to these weaknesses, the FE series may fail to assist students sufficiently in the acquisition of rhetorical forms, which are important for future essay exams.

Regarding text types, results of the study suggested that the SM series attended mainly to expository writing and the LT series mainly to descriptive writing. The many expository text types included in the SM series—e.g. definition, cause and effect, and classification—reflect the authors’ belief about the ability to explain being the most important rhetorical skill for EFL learners. The purpose of this focus on expository writing may be to prepare students to deal with writing of an academic nature, or to handle the Department Required English Test (DRET) in the future.

It has been suggested that expository and argumentative text types in general are more challenging than narrative text types (Richards & Schmidt, 2002). Yet in the SM series, numerous complex expository text types such as definition and causation as well as persuasion were all presented prior to narrative writing. This presentation sequence seems to be inconsistent with the aforestated view on the supposed difficulty levels of text types. Hence students’ initial encounter with text types may be rendered unnecessarily effortful in that those more challenging ones are presented first.

The thorough treatment of descriptive writing in the LT series, on the other hand,

appears to signify the weight the authors give to writers’ capacity to describe. It is

likely that to these authors, in writing, it is more essential for students to learn to

describe different people or objects from multiple viewpoints. This emphasis may also

imply that the textbook authors are rather concerned with students’ ability to deal with

the same subject with flexibility and diversity. The repeated treatment of this text type apparently gives it greater depth and hence may allow students to express themselves more adequately in descriptive writing.

Aside from text types, also worth attention is the special emphasis on the use of transitional devices in the SM and LT series. This emphasis seems to illustrate that using appropriate transition devices is an important quality of an effective writer.

Another implication is that transitional devices may represent an area of special difficulty for learners and, consequently, deserve greater instructional attention.

Finally, essay writing was practically unaddressed across the three series. This lack of attention to essay writing apparently ensued from a consideration of the length, complexity, and resulting challenge it might pose to senior high school students. Yet since college entrance exams usually require students to produce multiple paragraphs, neglect of essay writing in the three series will fail to prepare students in this regard.

Clearly, greater attention in future textbook compilation is required on essay writing.

To sum up, focusing on rhetorical forms appears necessary given the reality of essay exams and the need for writers to meet reader expectations. However, it is also very important to focus on meaning and processes so that writing will not turn into an exercise of manipulating rhetorical patterns.

General Neglect of Strategy Training

Contrasted with the heavy emphasis on rhetorical patterns in the three series is their general neglect of composing processes and strategies. The Process Approach, as evidenced in the three series analyzed in the current study, appears to be the most underrepresented pedagogical orientation. Its translation into pedagogical practices was found to be largely partial and limited. This shows that even with its merits widely reported in the literature (e.g. Akyel & Kamisli, 1996; Graham & Harris, 2003;

Sengupta, 2000), strategy training still does not seem to have resonated much with

these textbook publishers and authors in Taiwan.

As reported in Chapter Four, slightly more weight was given to strategies in the SM series. However, strategy training in this series was confined to the initial and concluding stages of writing. That is, student attention was guided only toward idea generation and editing. No effort was made to address planning, intermediate drafts, subsequent teacher/peer feedback, or multiple revisions. This appears indicative of the textbook writers’ inattention to writing as a creative and recursive process involving meaning discovery, self-expression and problem solving (Silva, 1990). Students using the SM series, as a result, are still offered little guidance during their drafting. It is significant that both the SM series and the other two series—aside from editing and invention techniques—also include strategies that help navigate students through their composing processes. Meanwhile, different teachers may conceptualize strategies differently. Hence the textbook writers of the threes series are advised to elaborate in teacher’s manuals on the definition and teaching of strategies.

Another problem is the little attention given in the series to the importance of postponing treating linguistic inaccuracies until the final editing stage. Students might be led, therefore, to edit their texts throughout their drafting process, a typical feature of EFL/ESL unskilled writers (Raimes, 1985). Efforts should be made in future textbook compilation to direct student attention first to the arrangement of ideas before the correction of errors.

To sum up, the common focus on rhetorical forms and general inattention to

strategies substantiates Kim’s (2001) observation that writing in EFL classrooms is

still taught in “traditional ways.” By and large, rhetorical forms remain the focus of

instruction in the three series. To assist students to compose more effectively, the

textbook writers of the three series are encouraged to devote greater attention to

strategy instruction than is currently paid.

Controversy Surrounding Grammar Instruction

Controlled Composition was found to be the second most dominant pedagogy in the three series. Nevertheless, the role of grammar in the three series still appears somewhat controversial. In the current study, the SM and LT series were found to contain abundant grammar teaching. The FE series, however, featured a complete lack of such instruction. This result is in accordance with Chan (2001). She found that of the three ESL composition textbooks she analyzed, two devoted more than 40%, whereas one less than 5%, of their total space to grammar instruction. Chan’s research and the present study therefore illustrate that debate to this date probably still remains as to whether to treat linguistic issues while teaching writing.

This controversy over grammar implies two different perspectives on the role of grammar in writing. First, the emphasis on grammar in the SM and LT series may be indicative of the authors’ perceived need for EFL writers to address formal correctness in their texts. At the same time, grammar may appear to them the one part of writing that is easier to teach and, as a result, frequently taught (Raimes, 1979). On the other hand, the FE textbook writers seem to believe that linguistic knowledge does not translate into good writing directly (Frodesen & Holten, 2003). Teaching grammar, in their view, simply cannot produce effective writers and, for this reason, is probably unnecessary.

Further analysis of the SM and LT series, however, identified attempts in both

series to justify their incorporation of grammar into writing instruction. In the SM

series, one portion of grammar (almost 20%) was taught to assist students to edit and

polish written products. This result corresponds to Muncie’s (2002) suggested need

for an explicit link between grammar and editing. Another portion (more than 30%)

was presented in tandem with instruction in text types to relate sentence patterns to

paragraph writing. These findings indicate that about half of the linguistic instruction

was taught intentionally in association with writing, as opposed to for its own sake.

The grammar instruction in the SM series nonetheless was not without its

inadequacies. As shown in the content analysis, the series focused mainly on different complex clause types. This emphasis suggests that the authors consider it essential for learners to acquire a repertoire of complex clausal constructions to express their ideas unambiguously. These constructions for the most part, however, were presented in isolation, without any effort to contextualize them. Thus much of the linguistic

instruction in the SM series, due to this decontextualization, may not really contribute to students’ actual composing ability. Grammar, as underscored by Celce-Murcia (1991), is of little avail to writers when learned in a decontextualized manner.

The LT series, on the other hand, dealt with a range of relatively simple grammatical constructions. Unlike the SM series, the LT series made a concerted effort to contextualize these constructions, highlighting their communicative functions.

Each construction was usually preceded by a situational context that required the use of the construction to be communicatively effective. This style of presentation appears to typify a focus on form rather than forms (Muncie, 2002)

15, and will more likely increase students’ chances of transferring learned structures into writing. It suggests that the textbook writers of the LT series construe grammar as a tool for facilitating communication and expressional efficacy.

In brief, the examination of linguistic instruction in the three series yielded some evidence for its contentious nature. It is suggested that grammar, when incorporated, be directly linked to strategies for editing composed products. Also important is the need to contextualize grammar instruction and relate each construction to its function.

15