CHAPTER FOUR RESULT AND DISCUSSION

In this chapter, the results obtained from the data analysis in the present study will be discussed. First, the overall findings will be presented. Next, I will examine the differences of linguistic behavior between men and women for a better understanding of men’s and women’s speech styles. Afterwards, men’s and women’s linguistic behavior will be discussed in terms of contexts and interlocutors.

Finally, the summary of this chapter will be presented.

4.1 General Findings

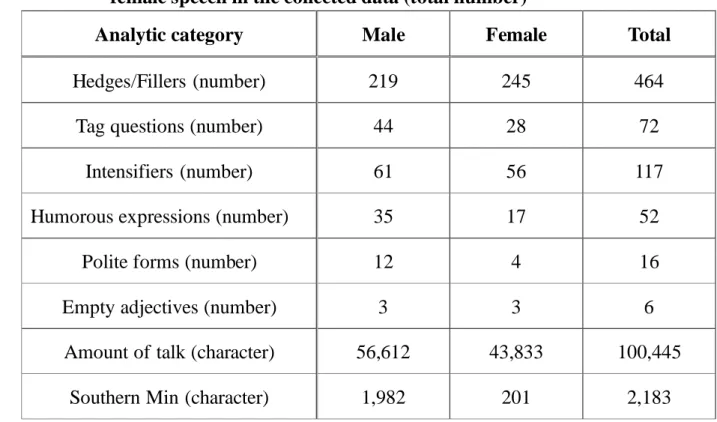

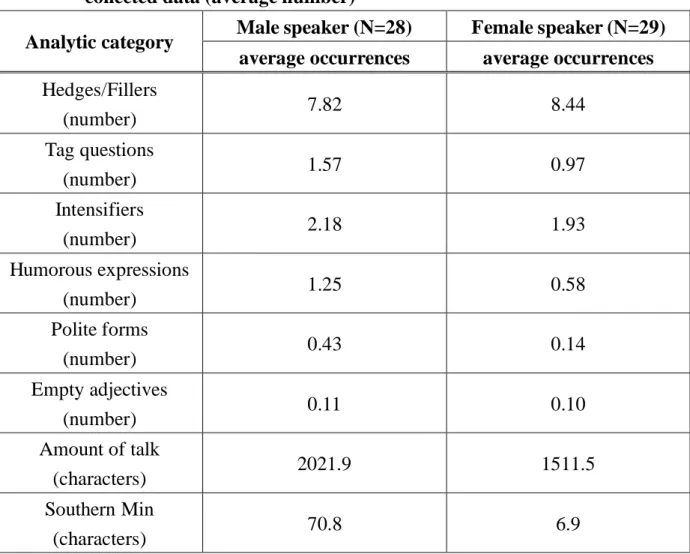

The total number of occurrences of different analytic categories is presented in Table 4.1. In the following, the average occurrences of each analytic category produced by the subjects are illustrated in Table 4.2. Because of the different numbers of male and female subjects in the study, the findings will be discussed according to the average number instead of the real number of occurrences.

The following are the linguistic categories to be observed: (1) hedges/fillers (wojuede“我覺得 ”, worenwei “ 我認為”, woxiang “我想 ”, nizhidao “你知道”, youdian “有點”, and youyidian “有一點”); (2) tag questions (duibudui “對不對”, shibushi “是不是”, houbuhou “好不好”, youmeiyou “有沒有”, bushima “不是嗎”, keyima “可以嗎”, bukeyima “不可以嗎”, haoma “好嗎”, shima “是嗎”, and youma

“有嗎”); (3) intensifiers (ruci “如此”, zheme “這麼”, and name “那麼”); (4)

joke-telling and humorous expressions; (5) polite forms (qing “請”, nikebukeyi “你可

不可以, ninengbuneng “你能不能, and nijiebujieyi “你介不介意); (6) empty

adjectives (keaide “可愛的”, xiyinrende “吸引人的”, mirende “迷人的”, youmeilide

Southern Min Dialect (Taiwanese).

Among the eight analytic categories, as shown in Table 4.2, men surpass women in six categories: tag questions, intensifiers, humorous expressions, polite forms, amount of talk and Southern Min Dialect. The only category which used more by females is hedges. In addition, males and females have no obvious differences in using empty adjectives. More details will be provided in the following sections.

Table 4.1 The total number of occurrences of each analytic category in male and female speech in the collected data (total number)

Analytic category Male Female Total

Hedges/Fillers (number) 219 245 464

Tag questions (number) 44 28 72

Intensifiers (number) 61 56 117

Humorous expressions (number) 35 17 52

Polite forms (number) 12 4 16

Empty adjectives (number) 3 3 6

Amount of talk (character) 56,612 43,833 100,445

Southern Min (character) 1,982 201 2,183

Table 4.2 The average frequency of each analytic category of speakers in the collected data (average number)

Male speaker (N=28) Female speaker (N=29) Analytic category

average occurrences average occurrences Hedges/Fillers

(number) 7.82 8.44

Tag questions

(number) 1.57 0.97

Intensifiers

(number) 2.18 1.93

Humorous expressions

(number) 1.25 0.58

Polite forms

(number) 0.43 0.14

Empty adjectives

(number) 0.11 0.10

Amount of talk

(characters) 2021.9 1511.5

Southern Min

(characters) 70.8 6.9

4.2 Hedges and Fillers

According to Lakoff (1975) and other previous studies (Bolinger, 1980; Holmes, 1992a; Coates, 1993), the expressions such as I think, you know, sort of, I guess, and I wonder are categorized as hedges and fillers. Lakoff suggests that hedges and fillers have the function of conveying uncertainty or of mitigating the degree of force in a statement. She further concludes that women use hedges and fillers more often because they believe that to assert themselves too strongly may be considered as

“unladylike” or “unfeminine.” Similar to Lakoff’s claim, Holmes (1986) has

observed that you know serves two major functions: one expresses the speaker’s

reflects uncertainty on both the speaker’s linguistic imprecision and the addressee’s attitude. In addition, Freed & Greenwood (1996:4) also addresses “the expression you know has often been described as a female hedging device, and interpreted as a marker of both insecurity and of powerless.” Therefore, in order to follow social values, women’s language tends to contain more hedges to avoid stating things too directly.

In Chinese, the counterparts of the hedges mentioned above are wojuede“我覺 得”, worenwei “我認為”, woxiang “我想”, nizhidao “你知道”, youdian “有點”/ and youyidian “有一點”.

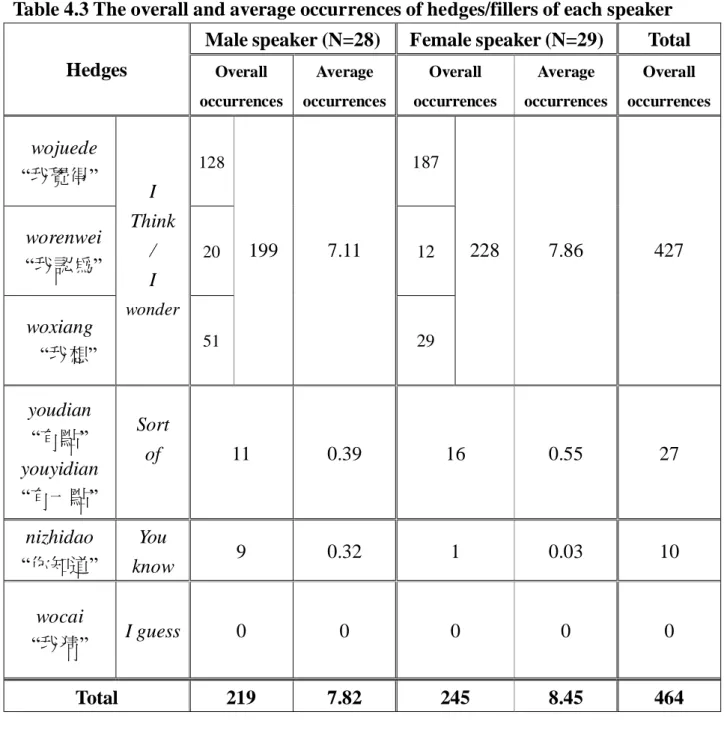

In analyzing hedges, the finding of the present study confirms what Lakoff has proposed: everyone uses hedges in some situations but women use them more frequently. As shown in Table 4.3, totally 464 hedges or fillers are found. In addition to overall occurrences, Table 4.3 also indicates that on the average, each male speaker uses 7.42 hedges or fillers while each female speaker produces 8.45.

Nevertheless, the occurrences of the different types of hedges are not distributed evenly. Among the different kinds of hedges, the ones most frequently used by both sexes are in the category of I think/I wonder (wojuede “我覺得”/worenwei “我認為”

/woxiang “我想”). 90% of the Chinese hedges are wojuede “我覺得”/worenwei

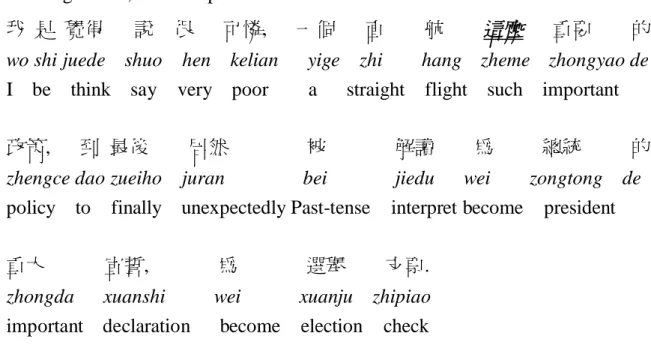

“我認為” /woxiang “我想”, as in the following examples:

(1) TV Program 3, Female speaker 5:

但是 一般 的 女孩子 如果 說 要 用 模特兒 來 做

danshi yiban de nuhaizi ruquo shuo yao yong moteer lai zuo but general girl if say want use model come do

跳板 的 話, 我覺得 , 這 中間 陷阱 很 多.

‘But if general girls want to use model to be springboard, I think there are many traps in it.’

(2) TV Program 3, Male speaker 21:

這 點 我認為 馬 市長 有 責任 要 跟

zhe dian worenweil ma shizhang you zeren yao gen this point I think Ma mayor have responsibility shall to

大家 講 清楚 說 明白.

dajia jiang qingchu shuo mingbai everyone say explicit say clear

‘As for this point, I think Mayor Ma should have the responsibility to make clear to everyone.’

The next type is sort of (youdian “有點”/ youyidian “有一點”). But compared with I think/I wonder (wojuede “我覺得”/worenwei “我認為” /woxiang “我想”) type, this type is less frequent. Only 6% of hedges in the data are youdian “有點”

and youyidian “有一點”. Besides, Only 2% of hedges in the data are you know (nizhisao “你知道”). However, none of the speakers use the counterpart Chinese of I guess (wocai “我猜”). Among these three devices, the Chinese expression wojuede

“我覺得” stands out in the I think category; it is the top device used by both men and women, as Table 4.3 shows.

In brief, the present study has found that women use more hedges than men do,

as Lakoff (1975) has observed. However, the difference is not very huge. On the

average a man uses 7.82 hedges and a woman produces 8.45. Besides, among all the

hedges, the category of I think/I wonder occurs most frequently. Over 90% of the

hedges used by both men and women are in the category of I think/I wonder (wojuede

Table 4.3 The overall and average occurrences of hedges/fillers of each speaker Male speaker (N=28) Female speaker (N=29) Total Hedges Overall

occurrences

Average occurrences

Overall occurrences

Average occurrences

Overall occurrences

wojuede

“我覺得” 128 187

worenwei

“我認為” 20 12

woxiang

“我想”

I Think

/ I wonder

51

199 7.11

29

228 7.86 427

youdian

“有點”

youyidian

“有一點”

Sort

of 11 0.39 16 0.55 27

nizhidao

“你知道”

You

know 9 0.32 1 0.03 10

wocai

“我猜” I guess 0 0 0 0 0

Total 219 7.82 245 8.45 464

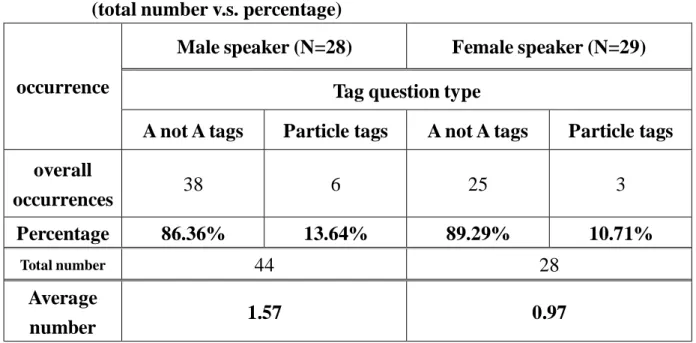

4.3 Tag Questions

According to Lakoff, tag questions such as isn’t it, don’t I, wasn’t there and so on are “used when the speaker is stating a claim but lacks full confidence in the truth of that claim” (1975:15). In Chinese, two general types of tag questions were observed by Hu (2002): (1) A not A tags (e.g. houbuhou “好不好”) and (2) particle tags (e.g.

keyima “可以嗎”). Based on these two basic types, the tag questions identified in

youmeiyou “有沒有”, bushima “不是嗎”, keyima “可以嗎”, bukeyima “不可以嗎”, haoma “好嗎”, shima “是嗎”, youma “有嗎”.

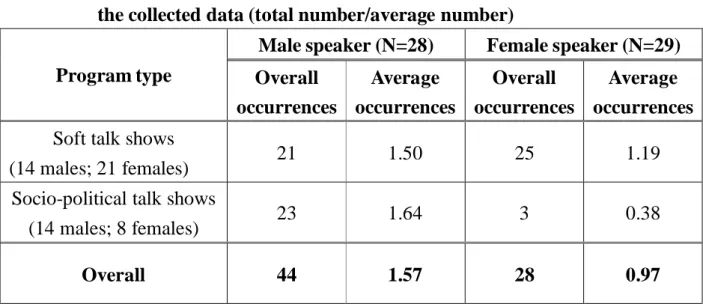

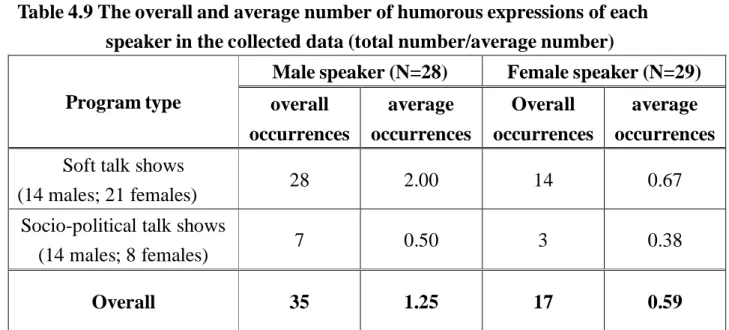

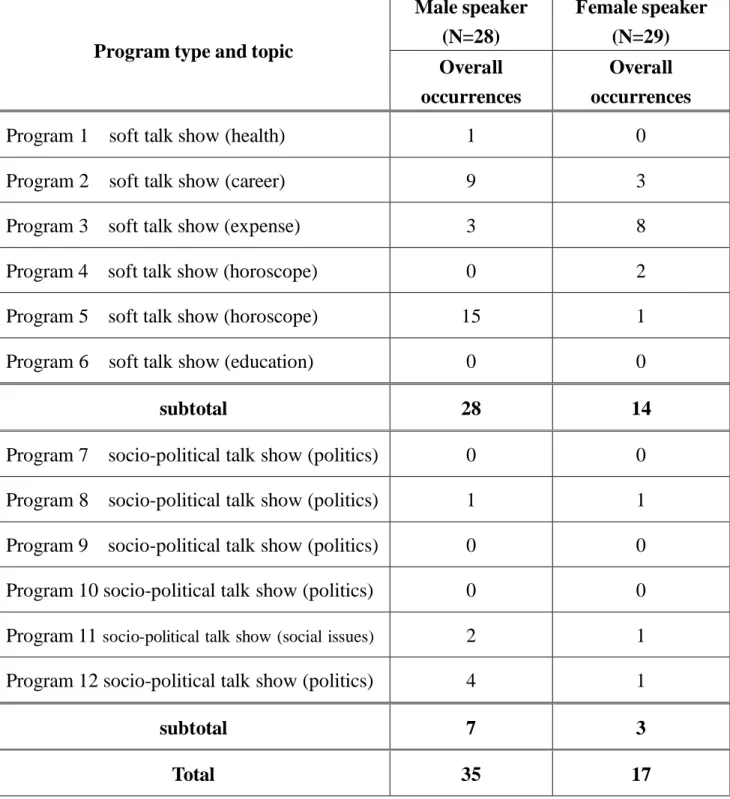

Lakoff (1975) asserts that tag questions occur more frequently in women’s speech than in men’s speech; however, the result of the present study seems to contradict her observation. That is, men use tag questions more frequently than women do. The result of the present study shows that regarding tag questions, each male produces an average number of 1.57 whereas each females 0.97, as shown in Table 4.4. Besides, as Table 4.4 shows, in not only soft talk shows but also socio-political talk shows, on the average men use more tag questions than women do.

On the average, each man uses 1.5 tag questions in soft talk shows and 1.64 in socio-political talk shows. By contrast, each woman uses such question to a much lesser degree than men do in both types of programs, 1.19 and 0.38, individually.

What’s worth noting is that when women’s frequency of tag questions in soft and

socio-political talk shows is compared, it is found that women use much fewer tag

questions in socio-political talk shows than in soft talk shows (3:1). Such ratio may

suggest that in socio-political talk shows, the topics under discussion are about social

and socio-political issues, which are masculine-oriented. Therefore, females tend to

avoid using too much “women’s language” in such programs. Instead, they change

their ways of talk to make their speech styles more similar to men’s.

Table 4.4 The overall and average occurrences of tag questions of each speaker in the collected data (total number/average number)

Male speaker (N=28) Female speaker (N=29) Program type Overall

occurrences

Average occurrences

Overall occurrences

Average occurrences Soft talk shows

(14 males; 21 females) 21 1.50 25 1.19

Socio-political talk shows

(14 males; 8 females) 23 1.64 3 0.38

Overall 44 1.57 28 0.97

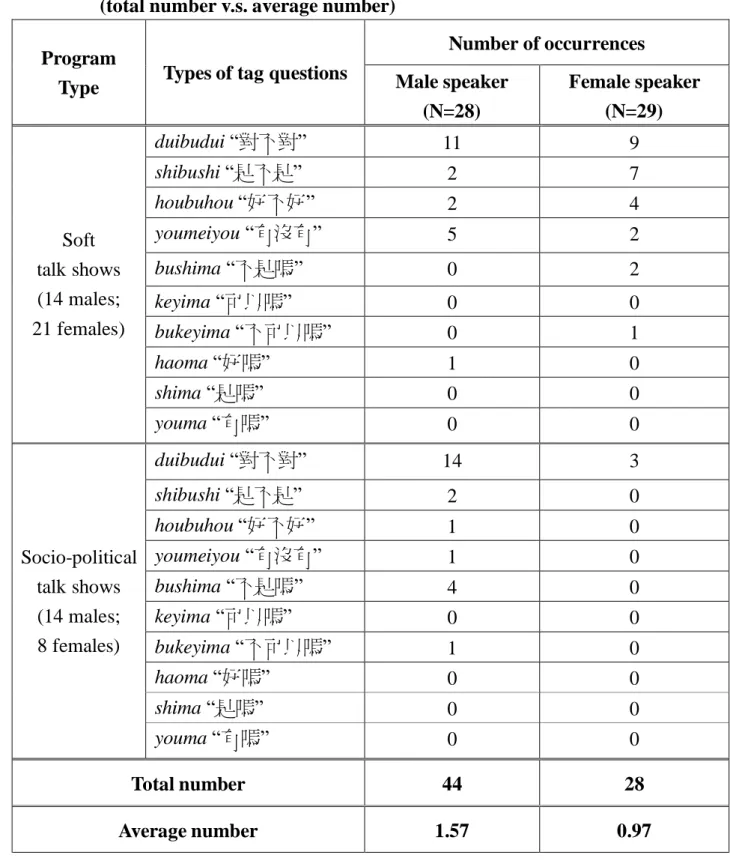

Among all these tag question types, the present study asserts that A not A tag is the most popular form used in males’ as well as females’ speech, as Hu (2002) has suggested. In Hu’s (2002) corpus, 89.89% of the tags are in A not A forms, 7.76 % are particle tags and 4.35% are others. In the present study, as Table 4.5 shows, about 86% of the tag questions in males’ speech fall into A not A forms (duibudui “對 不對”, shibushi “是不是”, houbuhou “好不好”, youmeiyou “有沒有”). Similarly, 89% of the tag questions in females’ speech are in A not A forms, too, as the following examples show:

(3) TV Program 3, Female speaker 7:

所以 你 盡量 選 有 綠 燈 的 時候

Suoyi ni jinliang xuan you lu deng de shiho so you try best choose have green light time

才 開, 對不對 ?

Cai kai duibudui?

just drive, right no right

‘So you try your best to drive when the lights are green, don’t you?’

(4) TV Program 11, Male speaker 27:

後來 章孝嚴 走 的 時候, 是 好像 小 男生 做 錯

holai Zhangxiaoyen zuo de shiho, shi haoxiang xio nansheng zuo cuo later PN go time is like little boy do wrong

事情, 躲 在 媽媽 後面 喔, 媽媽 幫 他 開 道 擋住

shiqing, duo zai mama huomian mama bang ta kai dao dangzhu thing hide at Mom back Mom help he open road block

所有 的 記者, 那 時候 還 有 丁遠超 在 前面

suoyou de jizhe na shiho hai you Dingyuanchao zai qianmian all reporter that time still have PN at front

推 記者, 有沒有 ?

tuei jizhe youmeiyou push reporter have no have

‘Later when Zhangxiaoyen was leaving, he was like a little boy doing something wrong. It seemed that he hid behind his mom and his mom opened up a road for him, blocking all the reporters. At that time there was Dingyuanchao pushing the reporters in the front, wasn’t there?’

On the contrary, particle tags (bushima “不是嗎”, keyima “可以嗎”, bukeyima

“不可以嗎”, haoma “好嗎”, shima “是嗎”, youma “有嗎”) are occasionally used, nearly 14% in men’s speech and 11% in women’s. The following is an example of particle tag.

(5) TV Program 3, Female speaker 10:

這 是 美德, 不 是 嗎 ?

zhe shi meide, bushima this is virtue no yes PR

‘This is virtue, isn’t it?’

Table 4.5 The distribution of two tag question types in the collected data (total number v.s. percentage)

Male speaker (N=28) Female speaker (N=29) Tag question type

occurrence

A not A tags Particle tags A not A tags Particle tags overall

occurrences 38 6 25 3

Percentage 86.36% 13.64% 89.29% 10.71%

Total number