Promoting EFL Learners’ Reading Comprehension through Interactive Reading Strategy Instruction

全文

(2) 1. Introduction Since the government in Taiwan carried out the Nine-Year Curriculum, the goal of the English curriculum for junior high school has been to prepare students with four basic communicative competences, in order to gain new knowledge and make successful choices in foreign affairs (The Ministry of Education, 2006). With regard to reading ability in junior high school, the emphasis is put on learning the use of cognitive strategies to independently construct meaning from texts. To cultivate reading as a lifelong ability, junior high school reading programs should thus begin to build students’ reading comprehension abilities, encourage the use of cognitive strategies, and enhance the ability to undertake independent interpretation. However, for various reasons junior high school students face different problems in achieving these aims. First, teachers and parents nowadays over-emphasize listening and speaking abilities in elementary schools, and reading is therefore often neglected (Tsai, 2008). Second, in order to keep up with the curriculum schedule, teachers at junior high schools seldom have enough time to provide students with sufficient opportunities enhance their reading abilities (Tsai, 2008). Third, students know few reading strategies and often experience difficulties in comprehending texts, even though they can read each word, which causes a vicious circle of declining interest, application, and ability (Hsu, 2004). It is thus necessary to develop ways to help students become active and independent readers, and one way to do this is by teaching the use of reading strategies. Although teachers in Taiwan have long perceived the importance of reading strategy instruction, there is still little reading comprehension instruction implemented in the classroom. Indeed, teachers often encounter difficulty when teaching reading comprehension strategies due to several problems. For instance, there is no model of teaching reading strategies that teachers can follow to show students how and when to apply such strategies effectively. In addition, the class size in Taiwanese junior high schools is usually too large for teachers to take care of students’ individual needs, although in recent years the government has tried to alleviate this problem (Tsai, 2008). Furthermore, teaching reading strategies is time-consuming, and if teachers spend time on this then they are likely to fall behind on their regular schedule of school work. This is especially for teachers who work with ninth-graders, as they need to spend most of their class time helping preparing for the Basic Competence Test (Lee, 2003). To achieve the goal of increasing the reading ability of junior high students so to help students become strategic and independent readers, an effective and applicable instructional framework which teaches the use of reading comprehension strategy is required. The purpose of the study was to investigate the effects of the interactive 73.

(3) reading strategy (IRS) instruction on EFL learners’ reading comprehension. Furthermore, this study also examined the effects of IRS instruction on their acquisition of diverse reading strategies as well as explored EFL learners’ responses to the proposed IRS instruction.. 2. Literature Review To cultivate reading ability as a life-long skill, the aim of reading instruction is to help students become active, self-regulated, and independent readers. To achieve this goal, metacognitive training is recommended to give cognitive strategy instruction (Block, Gambrell, & Pressley, 2002; Block & Pressley, 2002; Eilers & Pinkley, 2006). Urquhart and Weir (1999) proposed that metacognitive strategies are “more concerned with thinking about the reading experience itself” (p. 179). Williams and Burden (1997) also found that most of the strategy instructions “generally involve a sequence of first helping students to identify or become aware of strategies (p. 162). Through research on what skilled readers do while reading, a large number of cognitive and metacognitive strategies have been identified and researchers have hypothesized that if students were taught how and when to use comprehension strategies, then students can gradually acquire the strategies to gain understanding. Thereafter these strategies have been taught in strategy training programs to enhance students’ comprehension and in most studies, the results have supported this hypothesis (Ambe, 2007; Brown, 2008; Lapp, Fisher, & Grant, 2008). The above research has also shown that it is impossible to teach too many strategies in one study; however, it is essential to teach students to coordinate the use of multiple strategies. Therefore, to help students become strategic readers, it is necessary to select several strategies and teach them to coordinate the instructed strategies so that they can choose the appropriate strategy to overcome the difficulties they encounter in their own reading. The Basic Competence Test (BC Test) designed on the basis of the objectives of the Nine-Year Integrative Curriculum, has been implemented to replace the Joint Entrance Examination for Senior High School in Taiwan since 2001. The BC Test was held twice a year and students can choose to take either of them or both of the tests. In regard to the English test in the BC Test, the proportion of the reading comprehension questions has increased. Therefore, reading comprehension has become the major concern for both English teachers and students. Due to this, many researchers attempted to analyze the reading comprehension question types, where strategies are assessed, and to find out the frequent distribution of these types of questions so that the findings can be offered to English teachers as guidelines to provide effective strategies and design the reading materials for reading strategy 74.

(4) instruction. The previous studies have identified the following typical reading comprehension question types: questions for finding detailed information, for guessing the occasion, for identifying the reference, for guessing the vocabulary, for formulating the main idea, and for making inferences. However, there is one thing that is worth paying attention to; the previous studies also showed that the frequency of reading comprehension question types presented an unbalanced distribution (Yang, 2007). Despite the unbalanced distribution, to develop students’ awareness of the effectiveness of strategies in improving their reading comprehension, these six cognitive strategies were selected to teach the students in the present study to acquire effective strategies and to prepare them with the skills needed for the BC Test. The purpose of the intervention in the current study was to teach students to use cognitive strategies so that they can gain more understanding of a text. For educational practitioners, therefore, it is crucial to decide the order of teaching these strategies. Here, it is Bloom’s taxonomy that is most commonly referred to in the literature. Specifically Bloom et al. (1956, cited in Krathwohl, 2002) proposed taxonomy of educational objectives as learning aims for student achievement, and subsequently both academics and practitioners have often used this as the basis for designing a course. Three domains included cognitive, affective, and psychomotor. Under the cognitive domain, Bloom further detailed six stages of learning, starting from the simplest to the most complex: (a) knowledge, where learners are able to recognize or recall specific information; (b) comprehension, where learners are capable of interpreting or understanding ideas and information; (c) application, where learners can use or apply what they have learned to solve problems; (d) analysis, where learners have ability of finding the organizational principles of the material they are working with; (e) synthesis, where learners can put components together to create something new or useful; and (f) evaluation, where learners can make judgments on the arguments or articles they are presented with. The six stages can be seen as a continuum of difficulty, and thus learners have to attain the first stage before they learn the second one, and so on. According to Nentl and Zietlow (2008), Bloom’s taxonomy is widely used not only because of its simplicity, but also because of its versatility. That is, it can be applied at “all levels of education, from kindergarten through higher education” (p.160). Moreover, the order of teaching the selected strategies at all these levels was set according to Bloom’s taxonomy, in the following sequence. Strategy 1: Finding Detailed Information (Knowledge Category) 75.

(5) The knowledge category includes the objectives that learners have to recall or identify specific information. The strategy of finding detailed information utilizes key words to scan for, and it is the first skill that should be taught. Strategy 2: Guessing the Occasion (Knowledge Category) The strategy of guessing the occasion is also part of knowledge category. However, unlike the strategy of finding detailed information, here learners have to recognize key phrases or structures (such as advertisements, notices, and menus) and then activate their background knowledge or experience to guess the possible place where they might see such information. Since this is a more difficult task, it is taught after the strategy of finding detail information. Strategy 3: Identifying Pronoun Reference (Comprehension Category) The objectives in comprehension category involve the understanding of information. The strategy of identifying pronoun reference requires the learners to comprehend the information that comes before the pronoun. Strategy 4: Guessing Vocabulary (Comprehension Category) Though the strategy of guessing vocabulary also falls into the comprehension category, it is more complex than that of identifying the pronoun reference. When guessing vocabulary, learners need to understand not only the preceding information but also the following information, so that they can grasp the meaning of the words in context. That is the reason why the strategy of guessing vocabulary is put after the strategy of identifying the pronoun reference. Strategy 5: Formulating the Main Idea (Comprehension Category) The strategy of formulating the main idea also belongs to the comprehension category. When formulating the main idea, learners need to read through the text quickly and interpret all of it to grasp the basic meaning. Strategy 6: Making Inferences (Analysis Category) The objectives in the analysis category are to enhance the abilities of learners to organize or connect information. The strategy of making inferences is used to identify the related components in the text, connect the information the author provides, and finally to infer information that the author did not explicitly include. Among the six strategies this is the most complex, and so it is taught at the end of the intervention. The major hypothesis of the current study was that the interactive strategy 76.

(6) instruction would have positive effects on Taiwanese junior high school students’ reading comprehension. It was expected that students would have a better performance on the posttest than on the pretest. The second hypothesis was that the interactive strategy instruction would be beneficial for students to acquire the selected strategies. The researcher anticipated that students would get a higher score for each type of question, which represented each type of cognitive strategy, on the posttest than on the pretest. The third hypothesis was that the interactive strategy instruction would foster students’ strategy use and the researcher predicted that students would report higher frequencies of strategy use after the strategy intervention. The fourth hypothesis was that the interactive strategy instruction can be carried out effectively in the Taiwanese junior high classroom. It was expected that students would consider the six teaching methods under the interactive strategy instructional framework as effective ways to acquire the cognitive strategies.. 3. Methodology Participants The effectiveness of the interactive reading strategy instruction was tested in an experiment with a pretest-posttest design. The 68 participants were ninth-graders in a class with a mix of males and females at one of the high schools in Southern Taiwan. The English level of the students varied from high to low in each class. According to the performance in a reading comprehension pretest, the participants with different English proficiency level (EPL) were divided into three groups: high-EPL, intermediate-EPL, and low-EPL. Prior to the intervention, the students were asked for their consent. The objectives of this study were explained and all the students agreed to provide their performance as the data for this project. However, to get authentic data, students were not informed that they would be taking a posttest after the completion of the intervention. Materials Research has indicated that to enhance students’ comprehension, it is essential for teachers to broaden their definition of text into diverse texts and choose the texts that are motivational and appropriate for students so that teachers can prepare students for the future world (Block, Gambrell, & Pressley, 2002; Dunston, 2002). The teaching materials used for strategy instruction in this study were adopted mainly from GEPT Classroom: Reading & Writing (Qi, 2007), Reading: Elementary of Caves Books (Kuhel & Xie, 2008), GEPT Reading: Elementary of Caves Books (Xie & King, 2008), General English Proficiency Test: Elementary of Crane Publishing (Lai, 2008), and People, Places, and Things of Oxford (Book 1, Lin, 2005). 77.

(7) Furthermore, the reading comprehension question types in GEPT elementary are similar to the question types in the Basic Competency Test (BC Test). GEPT was often used to measure students’ English proficiency and the BC Test was considered as a criterion for entering senior high school. Therefore, the passages chosen as materials in this study would motivate the students to read the new information and stimulate the students to use the six selected strategies. Instruments Since there is no standardized reading comprehension test in Taiwan, a mock test of the elementary level of GEPT was used in the present study. The test of the elementary level of GEPT was chosen because the requirements with regard to vocabulary, grammar, and reading comprehension are equal to what students should learn at the end of junior high school. The mock test consists of 11 short passages, including figures, each followed by one to three multiple-choice questions, for a total of 25 questions. There were four questions each for detailed information, pronoun references, vocabulary, finding the main idea, and guessing the occasion, and five questions for making inferences. All 25 questions have to be answered within 45 minutes. In addition, there were two questionnaires in this study: one was used before (Pre-study Questionnaire) the instruction and the other was used after the instruction (Post-study Questionnaire). The difference between Pre-study Questionnaires and Post-study Questionnaires was the third part, which only appeared in the Post-study Questionnaire. The first part of the questionnaire was designed to collect demographic information, including the students’ gender, English learning experience, and English learning background. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of 17 items designed to understand the frequencies of students’ strategy use in the process of reading before and after the instruction. The third part of the questionnaire was designed to investigate students’ perception of the effectiveness of the interactive reading strategy instruction. Procedures Prior to the intervention, the researcher administered a reading comprehension test as the pretest and administered the questionnaire concerning the frequencies of students’ strategy use in the process of English reading. Each strategy was taught through a variety of methods: explicit instruction, teacher’s modeling, teacher’s scaffolding, writing recording sheets, group discussion, and independent reading as follows.. 78.

(8) Teaching method 1: Explicit strategy instruction. The teacher introduced the students to the importance, the purpose, and the use of a specific cognitive strategy to the whole class. Students here were interacting with the specific strategy so that they knew more about it and could recognize it while reading. Teaching method 2: Teacher’s modeling. The teacher used think-aloud to report her inner process of reading by completing a whole text in front of the whole class after an explanation of the strategy use. In this stage, the students were interacting with their teacher’s thinking. Teaching method 3: Teacher’s scaffolding. After the teacher’s modeling, she invited students to think aloud the process of comprehending a text. Whenever the students encountered the difficulty and stopped their reading, the teacher provided clues that cued specific strategy use and led students to apply the strategy. In this process, the students were interacting with the texts with the teacher’s guidance. Teaching method 4: Writing recording sheets. The teacher used sticky notes to show how she monitored her reading. The students were trained to interact with themselves, which means they were trained to ask questions and to talk to themselves. Teaching method 5: Group discussion. In the group discussion, students were asked to read four to five passages and find the answers together. In other words, during the group discussion, students were interacting with their classmates. Teaching method 6: Independent reading. During the repeated practices, the teacher provided no supports at all. That is, the students had to monitor their reading, think about the useful messages, utilize the strategy to figure out the information they needed, and then gain an understanding of the passage by themselves while reading, so students were interacting with texts. At the end of the experiment, students took a reading comprehension test as the posttest. Also, the questionnaire concerning the frequencies of students’ strategy use and students’ evaluation of the interactive reading strategy instruction were applied to the students.. 4. Results and Discussion 4.1 Effects of IRS Instruction on EFL Learners’ Reading Comprehension To examine the effects of the interactive reading strategy instruction on the reading comprehension test, there is a need to compare students’ scores on the posttest with the scores on the pretest. Because there is only one group (N = 68), the collected data in this study were analyzed with pair-sampling t-test. Pair-sampling t-test in SPSS for windows 8.0 was applied to analyze the data to compare students’ performance on the pretest with their performance on the posttest within the group. In addition to the outcomes of all students’ performance, the outcomes of the students with different 79.

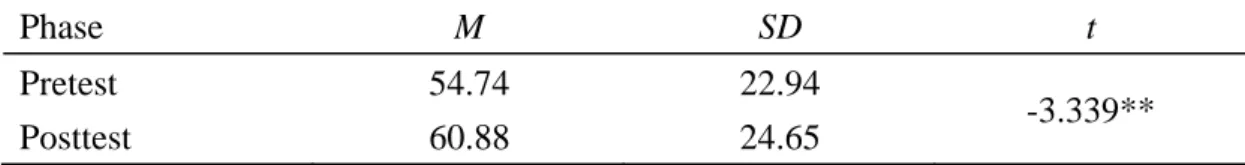

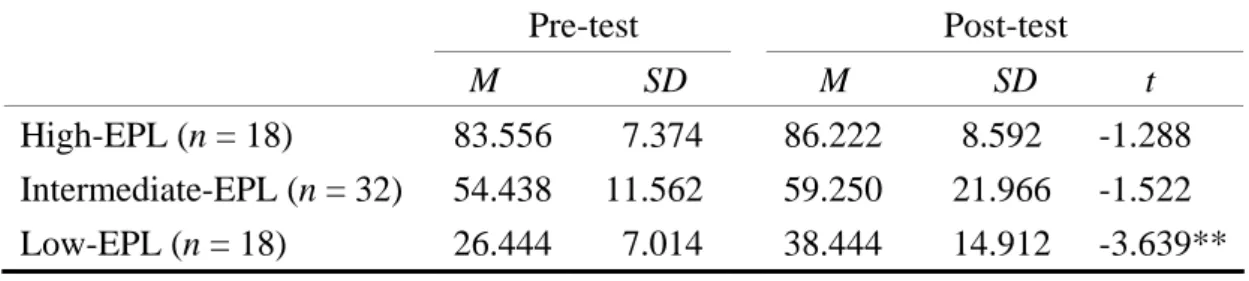

(9) English proficiency levels are also respectively adopted to scrutinize the effects of the interactive reading strategy instruction. Table 4.1 reports the means and standard deviation of the pretest and posttest scores for reading comprehension. The mean scores in Table 4.1 present that students performed better on the reading comprehension part of the posttest (M = 60.88) than on the reading comprehension part of the pretest (M = 54.74). In addition, the scores on the posttest showed a significant difference after being analyzed by pair-sampling t-test (t = -3.339, p <.01). The result indicates that junior high school students did make progress on the reading comprehension after the two-month reading strategy instruction. In other words, the interactive reading strategy instruction is an effective approach and has positive effects on developing students’ reading comprehension. Table 4.1 Participants’ Performance on Pre- and Post-test Reading Comprehension Phase Pretest Posttest. M. SD. t. 54.74 60.88. 22.94 24.65. -3.339**. Note. N = 68. *p <.05; **p <.01; ***p <.001. In view of a more precise analysis, students’ performances on reading comprehension performances of students with high English proficiency level (high-EPL), intermediate-EPL, and low-EPL are analyzed respectively to see if students in each level make progress after the reading strategy intervention. To achieve this goal, pair-sampling t-tests were applied to analyze the data in three levels respectively. As Table 4.2 indicates, high proficiency students performed better on the posttest (M = 86.222) than on the pretest (M = 83.556), but the difference did not reach a significant level (t = -1.288). Intermediate proficiency students also gained better scores on the posttest (M = 59.250) than on the pretest (M = 54.438). Though intermediate proficiency students did make progress on the posttest, the t-test still did not demonstrates a significant difference (t = -1.522). As for the low proficiency students, they made somewhat more progress on the posttest (M = 38.444) than on the pretest (M = 26.444) and the t-test demonstrates there is a significant difference (t = -3.639). The results indicated that low proficiency students benefited most among the three levels since their difference between the pre- and post-test reached a significant level. Undoubtedly, the result of low proficiency students’ reading comprehension performance again strongly supports that interactive reading strategy instruction has positive effects on students’ reading comprehension. Table 4.2 EFL Learners’ Performance on Reading Comprehension 80.

(10) Pre-test M High-EPL (n = 18) Intermediate-EPL (n = 32) Low-EPL (n = 18). 83.556 54.438 26.444. Post-test SD. M. 7.374 11.562 7.014. SD. 86.222 59.250 38.444. 8.592 21.966 14.912. t -1.288 -1.522 -3.639**. Note. *p <.05; **p <.01; ***p <.001 4.2 Effects of IRS Instruction on the Acquisition of Different Strategies As shown in Table 4.3, all students got higher scores for the six types of questions on the posttest than on the pretest. The mean scores for the six types of questions show that students did make progress in the six types of questions after the intervention (M = 7.474 < 8.706; 11.000 < 12.118; 8.118 < 9.294; 7.118 < 8.471; 7.647 < 7.882; 10.259 < 11.247). The participants’ overall performances show that the interactive reading strategy instruction has positive effects on participants’ acquisition of strategies. However, to be more specific, the t-test indicates that the difference between the posttest and the pretest reached a significant level for finding detailed information, guessing the occasion, guessing the vocabulary, and making the inferences (t = -2.001, -2.227, -2.185, and -2.241). There is no significant difference for indentifying the reference (t = -1.842) and formulating the main idea (t = -0.497). In other words, the results in Table 4.3 illustrate that the interactive reading strategy instruction is effective and useful for participants to acquire strategies for finding detailed information, guessing the occasion, guessing the vocabulary, and making inferences so that the difference reach a significant level. On the contrary, since the participants made less progress for identifying the reference and formulating the main idea, it implies that interactive reading strategy instruction is not effective enough for participants to acquire these two strategies so the difference is not significant. Table 4.3 Participants’ Performance of Pre- and Post-test Scores for Each Type of Strategy Strategy FDI GO IPR GV FMI MI. M. SD. Pretest. Posttest. Pretest. Posttest. 7.474 11.000 8.118 7.118 7.647 10.259. 8.706 12.118 9.294 8.471 7.882 11.247. 4.682 5.454 4.538 4.679 4.674 4.869. 4.684 5.216 5.373 5.242 4.686 4.642. Note: 1. N = 68. *p <.05; **p <.01; ***p <.001. 81. t -2.001* -2.227* -1.842 -2.185* -0.497 -2.241*.

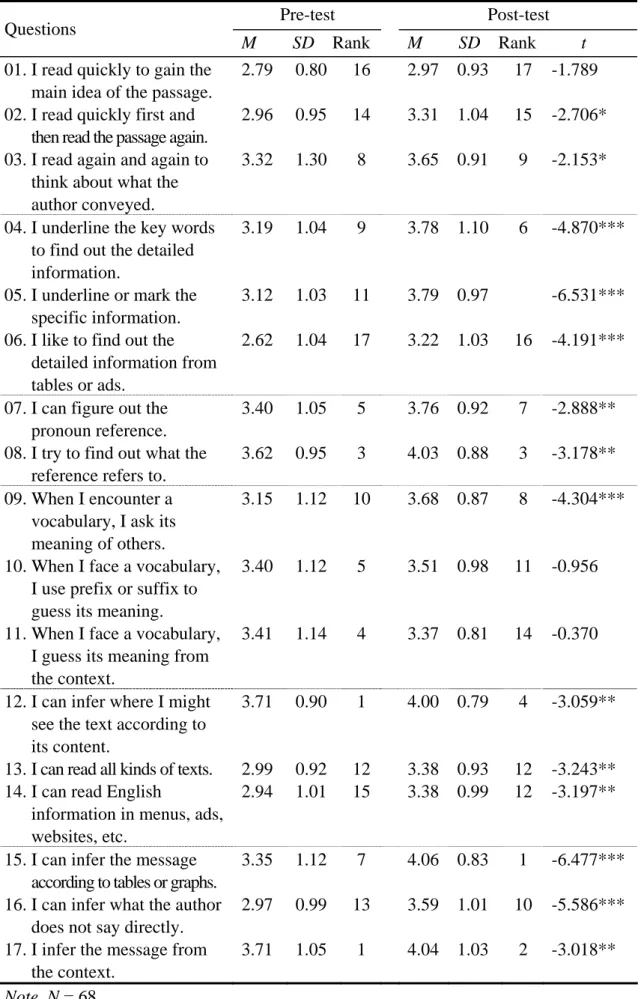

(11) 2. FDI refers to the finding detailed information strategy, GO refers to the guessing the occasion strategy, IPR refers to the identifying the pronoun reference strategy, GV refers to the guessing the vocabulary strategy, FMI refers to the formulating the main idea strategy, and MI refers to the making inferences strategy. 4.3 The Frequency of Students’ Use of Reading Strategies before and after the Interactive Reading Strategy Instruction To compare the frequencies of students’ strategy use before and after the instruction, the second part of the questionnaire was applied to the 68 participants before and after the instruction. Participants gave their answers from number 1, which represented “never used” to number 5, which represented “always used.” Participants’ answers were calculated and analyzed. The statistical results of their strategy use before and after the instruction are presented as follows. Table 4.4 shows that the frequencies of students’ strategy use were lower before the instruction. The mean value for the students’ strategy use ranged from 2.62 to 3.71. Students’ answers to their strategy use often fell into “seldom used” and “sometimes used.” In other words, when asked about the frequencies of strategy use in the process of reading, students often replied “seldom” or “sometimes” used. The possible explanations are as follows. First, students originally did not know or did not recognize these reading strategies. They are used to doing translations from English to Chinese word by word in the process of reading. Second, students know the strategies but seldom have enough experience of applying strategies to gain understanding when facing difficulties. In their previous English instruction, they may be seldom given the strategy instruction or seldom provided with opportunities to apply them. Therefore, the results of the questionnaire display low frequencies of strategy use in the pretest. Compared to the frequencies of students’ strategy use before the instruction, Table 4.4 indicates that students used reading strategies more often in the posttest than they did in the pretest. The mean values for the students’ strategy use after the instruction ranged from 2.97 to 4.06. This shows that the overall frequency of strategy use in the posttest increased. The frequency of strategy use reached “sometimes used” and “often used” level, even the “always used” level. In other words, when asked for the frequencies of strategy use in the process of reading, students often responded with “sometimes” “often” or “always” used. The results of the frequency of strategy use in the posttest imply that students acquired these strategies and were more capable 82.

(12) of applying these strategies to gain understanding. This indicates that they used these strategies more frequently and had performed better on each type of questions than they did in the pretest.. 83.

(13) Table 4.4 Frequencies of the Students’ Strategy Use before and after the Instruction Questions 01. I read quickly to gain the main idea of the passage. 02. I read quickly first and then read the passage again. 03. I read again and again to think about what the author conveyed. 04. I underline the key words to find out the detailed information. 05. I underline or mark the specific information. 06. I like to find out the detailed information from tables or ads. 07. I can figure out the pronoun reference. 08. I try to find out what the reference refers to. 09. When I encounter a vocabulary, I ask its meaning of others. 10. When I face a vocabulary, I use prefix or suffix to guess its meaning. 11. When I face a vocabulary, I guess its meaning from the context. 12. I can infer where I might see the text according to its content. 13. I can read all kinds of texts. 14. I can read English information in menus, ads, websites, etc. 15. I can infer the message according to tables or graphs. 16. I can infer what the author does not say directly. 17. I infer the message from the context. Note. N = 68.. Pre-test. Post-test. M. SD Rank. M. SD Rank. 2.79. 0.80. 16. 2.97. 0.93. 17. -1.789. 2.96. 0.95. 14. 3.31. 1.04. 15. -2.706*. 3.32. 1.30. 8. 3.65. 0.91. 9. -2.153*. 3.19. 1.04. 9. 3.78. 1.10. 6. -4.870***. 3.12. 1.03. 11. 3.79. 0.97. 2.62. 1.04. 17. 3.22. 1.03. 16. -4.191***. 3.40. 1.05. 5. 3.76. 0.92. 7. -2.888**. 3.62. 0.95. 3. 4.03. 0.88. 3. -3.178**. 3.15. 1.12. 10. 3.68. 0.87. 8. -4.304***. 3.40. 1.12. 5. 3.51. 0.98. 11. -0.956. 3.41. 1.14. 4. 3.37. 0.81. 14. -0.370. 3.71. 0.90. 1. 4.00. 0.79. 4. -3.059**. 2.99 2.94. 0.92 1.01. 12 15. 3.38 3.38. 0.93 0.99. 12 12. -3.243** -3.197**. 3.35. 1.12. 7. 4.06. 0.83. 1. -6.477***. 2.97. 0.99. 13. 3.59. 1.01. 10. -5.586***. 3.71. 1.05. 1. 4.04. 1.03. 2. -3.018**. 84. t. -6.531***.

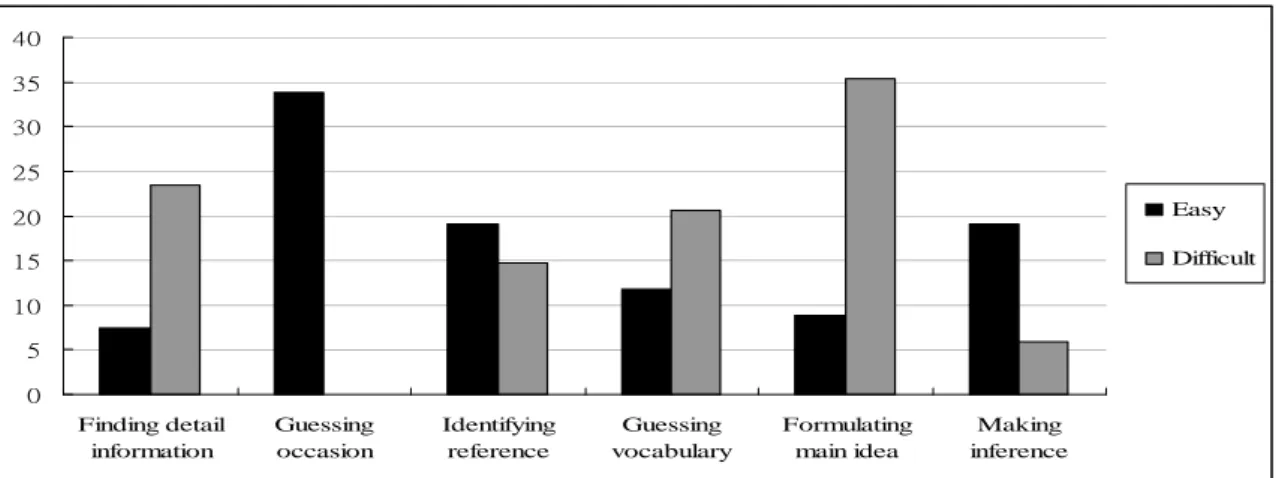

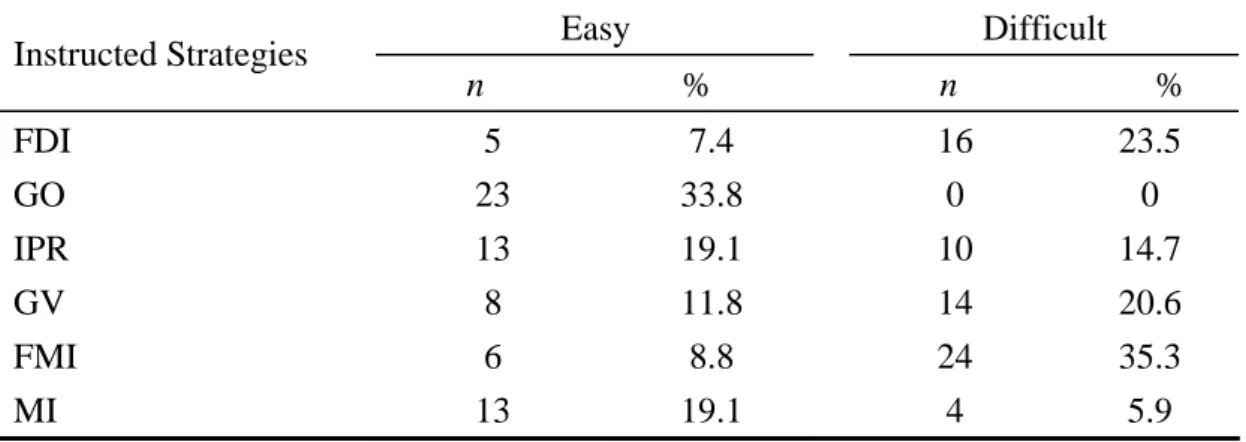

(14) To provide pedagogical implications for the future, the open-ended questions were designed to explore what problems or difficulties students encountered when using these strategies. The participants were asked to decide which strategy they considered the easiest strategy and which strategy they considered the most difficult. This section displays students’ responses and elaborates the difficulties they encountered. Participants’ responses were calculated in the form of numbers and percentages, which are reported in Table 4.5. The results are presented in Figure 4.1. As Figure 4.1 demonstrates, for the easiest strategy, to the highest percentage is for “guessing the occasion.” About 33.8% of the students regarded “guessing the occasion” as the easiest strategy. On the other hand, the most difficult strategy, according to Figure 4.1, is “formulating the main idea.” About 35.3% of the students reflected that finding out the main idea of a text was the most complex and difficult. The reasons why they can not successfully apply the strategy for formulating the main idea are as follows. First, students can not choose the best answer choice from similar ones. Students complained that they still could not decide which one was the best even though they deleted the two irrelevant answer choices. They often faced a dilemma choosing the first one or the second one. It implies that the participants focused on the details, but could not organize the related information. Second, students can not differentiate the main idea from the supporting details. Students were often confused by the supporting details. It implies that the participants failed to identify the main passage in the text and could not check if it is backed up by the other information in the text. Table 4.5 Students’ Responses to the Easiest and Most Difficult Strategies after the Instruction Instructed Strategies FDI GO IPR GV FMI MI. Easy. Difficult. n. %. n. 5 23 13 8 6 13. 7.4 33.8 19.1 11.8 8.8 19.1. 16 0 10 14 24 4. Note. N = 68.. 85. % 23.5 0 14.7 20.6 35.3 5.9.

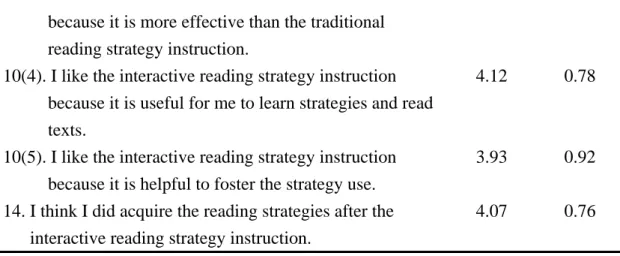

(15) 40 35 30 25 20. Easy. 15. Difficult. 10 5 0 Finding detail information. Guessing occasion. Identifying reference. Guessing vocabulary. Formulating main idea. Making inference. Figure 4.1. Students’ responses to the easiest and most difficult strategies after the instruction 4.4 Students’ Responses to the IRS Instruction To explore participants’ attitudes toward the interactive reading strategy instruction, the third part of the questionnaire was applied to the participants after the instruction. As indicated in Table 4.6, the results show that in general, most students had a positive attitude toward the effects of the interactive reading strategy instruction. The mean scores of the students’ attitudes toward the effects of the whole implementation of the interactive reading strategy instruction ranged from 3.93 to 4.22. Students thought that they did acquire the instructed reading strategies through reading strategy intervention because, as their responses expressed, reading texts became easy and interesting under this framework. That is, compared with the traditional reading strategy instruction, the interactive reading strategy instruction was an effective, useful approach that enhanced their reading comprehension. Table 4.6 Students’ Attitudes toward the Effects of the Whole Implementation of the Interactive Reading Strategy Instruction Item 08. I like to learn these strategies because they enhance my reading comprehension. 10(1). I like the interactive reading strategy instruction because it is easy and interesting to read texts under this framework. 10(2). I like the interactive reading strategy instruction because I feel comfortable to read under this framework. 10(3). I like the interactive reading strategy instruction 86. M. SD. 4.22. 0.86. 3.96. 0.7. 4.03. 0.65. 4.12. 0.97.

(16) because it is more effective than the traditional reading strategy instruction. 10(4). I like the interactive reading strategy instruction because it is useful for me to learn strategies and read texts. 10(5). I like the interactive reading strategy instruction because it is helpful to foster the strategy use. 14. I think I did acquire the reading strategies after the interactive reading strategy instruction.. 4.12. 0.78. 3.93. 0.92. 4.07. 0.76. Note. N = 68. To explore more deeply which teaching method the participants considered as the most effective, participants’ responses were calculated in the form of number and percentage, as shown in Table 4.7. According to Table 4.7, most students (42.6%) regarded group discussion as the most effective teaching method that can help their acquisition of the instructed strategies. Obviously, the percentage of the students who took group discussion as the most effective method exceeded the other methods implies that group discussion played an important role in the process of acquiring strategies. To the contrary, students responded that writing recording sheets was least effective teaching method, which reveals that reveal that students seldom monitor their thinking in the process of reading. In other words, the students in the current study did not have the habit of thinking about the reading process. Table 4.7 Ranking of the Percentages of Students’ Responses to the Most Effective Teaching Method Teaching Methods. N. %. Rank. Explicit strategy instruction Teacher’s modeling Teacher’s scaffolding Recording sheets Group discussion Independent reading. 10 7 8 1 29 13. 14.7 10.3 11.8 1.5 42.6 19.1. 3 5 4 6 1 2. Note. N = 68.. 5. Conclusion Overall, the results above clearly indicate that the interactive reading strategy instruction has positive effects on high school students’ reading comprehension, which supports the first hypothesis that the interactive reading strategy instruction 87.

(17) enhances EFL junior high school students’ reading comprehension. The result corroborates the previous studies on EFL reading comprehension that reading strategy instruction results in the improvement of performance on reading comprehension (Lee, 2003; Tsai, 2008; Yang, 2007; Yeh, 2006). Furthermore, the results show that the IRS instruction is most beneficial for low proficiency students, which was surely consistent with the previous studies that the use of reading strategy not only compensates for low proficiency students’ lack of vocabulary and grammar knowledge but also closes the gap on reading comprehension between high and low proficiency students (Ambe, 2007; Lee, 2003; Tsai, 2008). With regard to students’ acquisition of the six selected strategies, students’ performances for each type of questions present that IRS was useful for EFL learners to acquire the strategies for finding detailed information, guessing the occasion, guessing the vocabulary, and making the inferences; however, it was not effective enough for students to identify the reference and formulate the main idea of a text. When analyzing students’ responses toward their strategy use before and after the interactive reading strategy instruction, the results report that students use the instructed strategies to comprehend texts more frequently after the intervention. This finding is consistent with Yeh’s (2006) study which found the frequencies of strategy use did increase after reading strategy instruction. It is speculated that the IRS instruction increases students’ acquisition of reading strategies and fosters students’ strategy use. Therefore, the finding that students’ acquisition of reading strategy resulted in the improvement on the reading comprehension in the current study also support the hypothesis that that strategy instruction has a positive effect on the frequencies of the strategy use, which can enhance students’ comprehension. As for the students’ comments on the interactive reading strategy instruction, most students had positive attitudes toward strategy instruction because the instruction facilitated their reading comprehension. The participants also responded that group discussion as the most effective way that helped them acquire and apply the instructed strategies. The result is in accordance with previous studies (Lee, 2003; Tsai, 2008), where students mostly responded that group discussion can help them solve the problems they encounter, improve their reading comprehension, and appreciate different viewpoints. It was suggested that English teachers in Taiwan can take advantage of the effects of group discussion in the future practical strategy instruction.. References Alfassi, M. (2004). Reading to learn: Effects of combined strategy instruction on high school students. The Journal of Educational Research, 97(4), 171-184. Ambe, E. B. (2007) Inviting reluctant adolescent readers into the literacy club: Some 88.

(18) comprehension strategies to tutor individuals or small groups of reluctant readers. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 50(8), 632-639. Anderson, N. J. (1999). Exploring second language reading. Boston: Heinle & Heinle. Anderson, V. (1992). A teacher development project in transactional strategies instruction for teachers of severely reading-disabled adolescents. Teaching and Teacher Education, 8, 391-403. Block, C. C., Gambrell, L. B., & Pressley, M. (2002). Improving comprehension instruction: Rethinking research, theory, and classroom practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Block, C. C., & Pressley, M. (2002). Comprehension instruction: Research-based best practices. New York, NY: The Guilford Press. Brown, R. (2008). The road not yet taken: transactional strategies approach to comprehension instruction. The Reading Teacher, 61(7), 538-547. Casteel, C. P., Isom, B. A., & Jordan, K. F. (2000). Creating confident and competent readers: Transactional strategies instruction. Intervention in School & Clinic, 36(2), 67-74. Cohen, A. D. (1998). Strategies in learning and using a second language. London: Longman. Collins, C. (1991). Reading instruction that increases thinking abilities. Journal of Reading, 34, 510-516. Duffy, G. G., Rochler, L. R., Sivan, E., Rackliffe, G., Book, C., Meloth, M., Vavrus, L. G., Wesselmann, R., Putmam, J., & Bassiri, D. (1987). The effects of explaining the reasoning associated with using reading strategies. Reading Research Quarterly, 22, 347-368. Dunston, P. J. (2002). Instructional components for promoting thoughtful literacy learning. In C. C. Block, L. B. Gambrell, & M. Pressley (Eds.), Improving comprehension instruction: Rethinking research, theory, and classroom practice (pp. 135-151). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Eilers, L., & Pinkley, C. (2006). Metacognitive strategies help students to comprehend all text. Reading Improvement, 43(1). Retrieved July 2007 from Proquest. Gersten, R., & Carnine, D. (1986). Direct instruction in reading comprehension. Educational Leadership, 43(7), 70-78. Greenway, C. (2002). The process, pitfalls and benefits of implementing a reciprocal teaching intervention to improve the reading comprehension of a group of year 6 pupils. Educational Psychology in Practice, 18(2), 113-137. Hsu, S. C. (2004). Reading comprehension difficulties and reading strategies of junior high school EFL students in Taiwan. Unpublished master’s thesis, 89.

(19) National Kaohsiung Normal University, Taiwan. Krathwohl, D. R. (2002). A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 212-218. Lapp, D., Fisher, D., & Grant, M. (2008). “You can read this text-I’ll show you how”: Interactive comprehension instruction. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 51(5), 372-383. Lee, C. L. (2003). Promoting reading comprehension ability and vocabulary learning through collaborative strategic reading. Unpublished master’s thesis, National Taipei Teacher College, Taiwan. Nentl, N., & Zietlow, R. (2008). Using Bloom’s taxonomy to teach critical thinking skills to business students. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 1(2), 159-172. Palincsar, A. S., & Brown, A. L. (1984). Reciprocal teaching of comprehension-fostering and comprehension-monitoring activities. Cognition and Instruction, 1, 117-175. Pressley, M., El-Dinary, P. B., Gaskin, I., Schuder, T., Bergman, J., Almasi, L., & Brown, R. (1992). Beyond direct explanation: Transactional instruction of reading comprehension strategies. Elementary School Journal, 92, 511-554. Scharlach, T. D. (2008). START comprehending: Students and teachers actively reading text. The Reading Teacher, 62(1), 20-31. Spörer, N., Brunstein, J. C., & Kieschke, U. (2009). Improving students’ reading comprehension skills: Effects of strategy instruction and reciprocal teaching. Learning and Instruction, 19, 272-286. Takala, M. (2006). The effects of reciprocal teaching on reading comprehension in mainstream and special (SLI) education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(5), 559-576. Tsai, Y. J. (2008). A case study of cultivating junior high students’ English reading comprehension through cooperative strategy-based instruction. Unpublished master’s thesis, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan. Urquhart, S., & Weir, C. (1999). Reading in a second language: Process, product, and practice. London and New York: Longman. Williams, M., & Burden, R. L. (1997). Psychology for language teachers: A social constructivist approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Yang, C. Y. (2007). An analysis of the English reading comprehension tests in the basic competence test and the instruction of the reading skills and strategies in class. Unpublished master’s thesis, National Chengchi University, Taiwan. Yeh, I. C. (2006). The effects of reading strategies instruction on junior high school students’ reading comprehension in Taiwan. Unpublished master’s thesis, National Chengchi University, Taiwan.. 90.

(20)

數據

相關文件

reading and creating multimodal texts, promoting Reading across the Curriculum (RaC) and developing students’ self-directed learning capabilities... “Work as a team to identify the

● develop teachers’ ability to identify, select and use appropriate print and non-print texts of a variety of text types and themes to enhance students’ motivation and confidence in

• Extending students’ learning experience through promoting Reading across the Curriculum (RaC) & using Writing across the Curriculum (WaC) activities as a

understanding the features of academic genres (or text types) and detailed reading strategies. This could work in all school contexts, including

help students develop the reading skills and strategies necessary for understanding and analysing language use in English texts (e.g. text structures and

understanding the features of academic genres (or text types) and detailed reading strategies. This could work in all school contexts, including

Passage: In social institutions, members typically give certain people special powers and duties; they create roles like president or teacher with special powers and duties

Making use of the Learning Progression Framework (LPF) for Reading in the design of post- reading activities to help students develop reading skills and strategies that support their