An Investigation of Taiwanese Non-English Major Freshmen’s Perception of Learning English through

Online Edutainment Games

Abstract

This study aims to investigate how non-English major freshmen in Taiwan perceive their English learning through task-based online interactive negotiation games. A large body of evidence suggests that limited time for English learning and a lack of effective learning strategy have caused inadequate and ineffective English learning of non-English major students in Taiwan.

Therefore, this research attempts to draw upon an online edutainment game website to provide 30 non-English major freshmen with remedial instruction. With a qualitative approach, this study was executed during one academic year to investigate students’ perception of instructional uses of edutainment games. Student participants showed that simulation and interactivity of online edutainment games address a need for alternative learning in remediation of vocabulary deficits.

The online negotiation games can model complex worlds where players can witness how targeted words are used by game characters and experiment with those words. Participants agree that online edutainment games add interaction to their learning and provide them with authentic contexts to learn new vocabularies. In addition, prompt feedbacks and risk-free conversation options of online negotiation games engage students in learning vivid word and sentence examples.

Keywords: computer assisted instruction, edutainment games, game-based learning

To-Ken Lee's E-mail: shawnlee@cc.hfu.edu.tw

To-Ken Lee

Assistant Professor, Department of Foreign Language and Literature, Hua Fan University

臺灣大學生對透過寓教於樂型遊戲 學習英文之意見

李多耕電子郵件:shawnlee@cc.hfu.edu.tw

李多耕

華梵大學外國語文學系助理教授摘 要

本研究旨在探究臺灣非主修英語系之大一學生,對於透過網路互動之協商 型遊戲來學習英文的看法。眾多文獻指出,臺灣非英語系大學生英語學習成效不 彰,肇因於英語學習時間的有限和英語學習策略的匱乏。因此,本研究主要調查 一個由三十名非英語系主修的大一學生所參與的補救教學課程。在課程中,研究 者使用網路互動式之寓教於樂型遊戲並佐以教學計畫。本研究使用質性分析方 法,來探討學生對於以寓教於樂型遊戲為英語教學策略的認知。結果顯示,線上 寓教於樂型遊戲中的虛擬性和互動性,能夠補足現行英語教學成效不彰之處。線 上寓教於樂型遊戲可以以生動之介面,讓學生觀看英語單字可以如何應用於實際 生活中。調查結果發現,參與者認為寓教於樂型的遊戲,能為英語學習增添互動 性。除此之外,該類遊戲所提供的擬真環境,亦有助於單字的學習。結論指出,

遊戲的即時回饋和無風險性對話的兩個特色,能使得英語單詞和句子變得生動有 趣,並進而激發學生投注於單詞和句子的學習。

關鍵詞:電腦輔助教學、寓教於樂型遊戲、遊戲教學

Introduction

A burgeoning number of studies are now available to shed some light on the educational potential of games (Gee, 2003; Shaffer, 2007; Squire, 2006; Steinkeuhler, 2006). Due to the fact that mainstream computer games emphasize interactivity, it becomes easier to shape a learning environment in which students can witness how knowledge can be used, receive prompt feedbacks, and take initiatives to trial and error (Barron et al., 1998; Bereiter & Scardamalia, 1993; Kafai, 1995; Hmelo & Williams, 1998; Schwartz, Lin, Brophy, & ,Brandsford, 1999). Such an emphasis on interactivity echoes the focus of computer assisted language learning (CALL) for its capability to encourage student learning by offering immediate feedbacks, clear goals, and challenges that are matched to students’ readiness level (Chapelle, 2005; Egbert, 2005; Miyagi, 2006; Nunan, 2006; Warschauer & Healey, 1998). The development of CALL suggests that the computer enables a variety of uses of language teaching, providing not only a stimulus for interaction and practice, but also a medium for writing and reading (Warchauer, 1996).

Previous studies on CALL have centered on how the application of CALL affects the development of language learners’ four skills in listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Researchers and teachers dedicated in the field of CALL have also been studying how technology-mediated instruction can elevate learners’ motivation (Guthrie &

Richardson, 1995; Liou, 1997; Van Aacken, 1999). One perspective of CALL, integrating online educational games into language learning, has received attention from researchers for its capacity to engage students in language learning. Games have been praised for their capacity to create a learner-centred environment by providing students with opportunities for socialising, awakening the will to win, and satisfying the competitive desire of students (Uzun, 2009).

Although “serious game” researchers such as Johnson (2006), Gee (2005), and Prensky (2006), and have indicated the educational value and learning potential of computer games, ideas and assistances for teachers interested in using entertainment games in a language class are still difficult to find. Johnson (2006) further points out that new generation of students are growing up on computer games, and this is altering their expectations of and demands on education. Likewise, Stanley and Mawer (2008) suggest that teachers and administrators should be able to engage these learners by appealing to their interests and make language teaching relevant to their world.

Edutainment is a combination of education and entertainment and refers to the educational applications which are packaged as games (Beatty, 2003). Pan (2006) argued that edutainment reflects “the union between education and entertainment in a television program, game or website” (p. 1). Rapeepisarn, Wong, Fung, and Depickere (2006) viewed the term edutainment as a bridge to connect two domains, gaming and learning.

Therefore, edutainment games refer to a specific category of games designed to teach the player a real-life subject. This type of game is designed to be used by a teacher or a tutor to make learning more fun and characterized by disguising learning.

Meyer (2008) divides games into three categories in terms of their educational uses for language learning: (1) Edutainment and learning games: Games of this category can be viewed as a combination of education and entertainment. Edutainment games target on triggering and enhancing learning through entertainment. Edutainment games designed for learning inside and outside school are often named “play and fun.”

According to Meyer’s definition, these games invite autonomous learning and thus they are designed for use without teacher intervention. (2) Research-based educational games:

These games are made for educational uses in schools and involve teacher interventions.

Games of this category are also named “serious games”. Research-based educational games are designed on basis of learning theories of modern schooling. (3) Games for entertainment: While games of this category are not designed for educational use, they are sometimes employed in the educational system to cultivate learning in different subjects. However, some ambiguity exists among these three types of games in terms of Meyer’s classification. His definitions fail to discuss the possible transfer among different types of games and such transfer could be associated with teachers’ involvement. In this study, the researcher draws upon edutainment and learning games because English learning is no longer the only purpose in class. Also, the study attempts to examine the need of teachers’ intervention while students process learning through edutainment games.

Although Meyer suggested that edutainment games could provide teachers with an ideal context to engage students in learning, studies on the effectiveness of edutainment online games to facilitate Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) is scarce. In recent years, considerable concern has arisen over the application of educational games in English learning. A number of educational online games, especially designed for vocabulary acquisition, aim to provide learners with repetitive and persistent exercises. Therefore, many educational games are described as more “educational” than

“fun” (Stanley & Mawer, 2008) and how to use non-educational games to facilitate TESOL has started to gain growing attention in the field of foreign language teaching (Ang

& Zaphiris, 2009; Meyer, 2008; Stanly & Mawer, 2008; Suparp, Todd, & Darasawang, 2006).

Stanley and Mawer (2008) suggested language teachers make use of existing games that have been proven to be fun and to design tasks around them to discover more opportunities to teach language. In order to understand how edutainment games facilitate Taiwanese non-English major freshman’s English learning, this study chose an edutainment game website containing several online negotiation games. The website is designed by Zapdramatic, a multi-award-winning interactive media which designs and produces dramatic simulation games to entertain, educate, and influence opinions.

This company provides interactive services to organizations such as Agriculture Canada and Canadian Tourism Commission to develop online learning applications with an emphasis on negotiations, relationship and ethical practices. It has also created licensed and customized online negotiation games for corporate, professional, and educational markets.

Negotiation games have been utilized to teach useful principles of negotiation, psychology or influence in a fun and interactive environment. For instance, "Diplomacy"

is a classic negotiation game from the 1950s with a setting in Europe prior to World War I. The game is designed for two to seven players and each player controls one of the seven world powers during that time, competing to gain support from each other to win the most battles. Alliances can be negotiated and changed throughout the game.

Players need to negotiate the best alliances for military supports at any specific time during the game. Ally at one time during the game can become enemy later. Unlike most of games concentrating on competition between the computer and player or between players, negotiation games address the win-win settlement between competitors. In other words, most negotiation games leave the decision of what winning or losing means to the players. This study chose negotiation game as an experimental platform because games of this type provide students with multiple possibilities to settle game purposes and with opportunities to witness conversation processes in the context of English as a foreign language.

The simulation interactive negotiation games are more engaging to students, and many of these games have authentic language in a context that is often hard to find in

the educational games (Suparp, et al.,2006). Curriculum designers can utilize this type of games to position students, contents, and contexts for achieving educational goals. In these games, students can play roles of scientists, doctors, or businessmen who engage complex disciplinary content to transform a virtual world (Sasha, Melissa, & Adam, 2010). In this study, the researcher also constructed lesson plans in terms of the games, and provided guidelines to participants regarding how to play online games. During the academic year, interviews, classroom observations, and group discussions were employed to understand students’ perception of using edutainment games to assist their language learning.

The difference between simulation and game is contingent upon the purposes.

Games are designed for fun, and simulation is to provide training experience. However, these two sectors begin to come together with technological advance. The notion of

“serious games” develops because of the attempts to leverage concepts from gaming in order to provide useful training experiences. Ang and Zaphiris (2009) held that simulations model a system instead of representing as traditional media such as texts, pictures, and videos. For instance, a three dimensional environment depicting a car can be constructed to train someone to drive. Such a simulation models the functions of a real car: how to make a car move and stop by stepping on the gas and brakes. As Ang and Zaphiris suggest, simulations are usually top-down by helping users focus on general rules, which they can apply to specific cases. Instead, representations of narratives are bottom up as they describe the events from which people can generalize and infer. Therefore, the claim for serious games is to find some way to merge these two ideas: training experience and fun. In the domain of language learning, educators and researchers have been attempting to capture the essence of a successful game that makes it fun to play, and use that to achieve the same level of engagement in a training environment (Suparp, et al., 2006).

The goal of the present study is to understand how non-English major freshmen perceive integrating online edutainment games into their learning. This study chose non- English major freshman students because studies have shown that transition between school and university can be challenging (Martinez, 2001). Although several reasons can be attributed to these difficulties, such as the adjustment to a new instructional environment, students usually call for a period of readjustment to become more active and progressive learners, and scaffolding and extending their learning experience beyond the classroom (Fry & Ketteridge, 1999). Students at this transitional stage require more

instructional and curricular attention in order to adapt themselves to a new academic journey. Therefore, this study aimed to understand how non-English major freshmen perceive learning English through playing online negotiation games. Also, this study sought to the role and impact of teachers during using online edutainment games.

Furthermore, Huang (2010) points out that non-English major freshmen often fail to find an effective way to enhance their English level. In addition, the limited class hours and the legion of students in class make the design of Freshman English classes more challenging. Since the researcher teaches in the department of Foreign Language and Literatures, studying approaches to blend online interactive negotiation games into English instruction can be seen as venturing into an unknown area. Therefore, the question guiding the proposed study is:

What implications do online edutainment games provide to English instruction and curriculum?

By exploring the research question, using qualitative inquiry help us understand and develop strategies to use edutainment games as pedagogical tools from students’

perspective. The next section provides a review of a literature that summarizes various studies about CALL for language teaching.

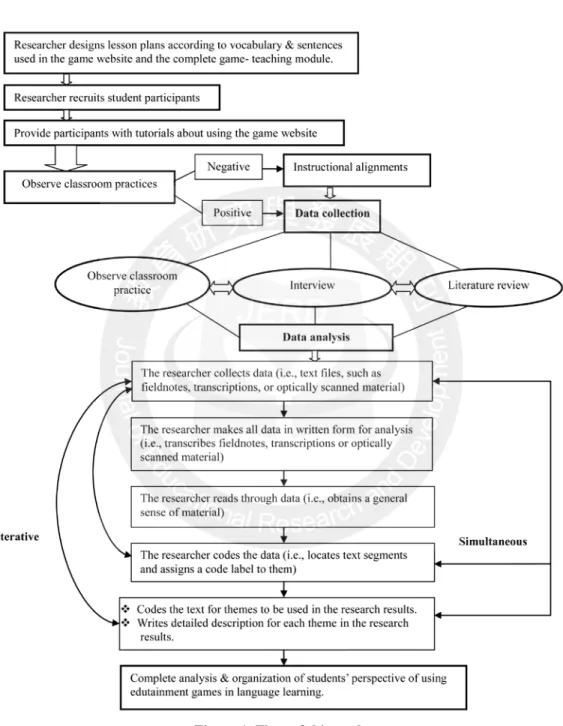

Figure 1. Flow of this study

Adapted from Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research, p. 258, by J. Creswell, 2002, Upper Saddle River: NJ: Pearson Education

Review of literature

According to Bransford (1999), attempts to use computer technologies to facilitate learning began around 1968. With the emergence and popularity of CALL, English as Foreign Language (EFL) teachers have shifted their focus from textbook-centered or teacher-centered instruction to classroom-based or student-centered approaches (Hu &

Deng, 2007). The presence of computer technology in schools has increased dramatically, and it appears that this trend will continue to accelerate (U.S. Department of Education, 1994). The literature on computer-mediated learning shows that computer technology has the potential to advance student achievement and teacher learning, with the assumption that it is appropriately incorporated into instruction (Bransford, 1999). Computer-assisted technology provides students with visualization, presents a modeling that resembles a non-academic setting and exhibits an arena to train students for transferring the knowledge they learn in school to a non-academic setting.

Given the vast array of advantages provided by computer-assisted technologies, the subsequent review of literature focus on two perspectives: computer games used for foreign language vocabulary learning and the application of edutainment games in English teaching.

Computer games used for foreign language vocabulary learning

Although vocabulary building is seen as the foundation of learning a language, the issue is always perceived as being boring for students and challenging for teachers.

A great deal of studies have examined and discussed different aspects of foreign word teaching and learning. With the recent increased interest in adopting computer programs to promote language learning, many researchers have dedicated themselves to exploring how computers and software can facilitate vocabulary learning (de Freitas & Griffiths 2008; de Groot, 2000; Yip & Kwan, 2006). In general, two primary advantages have been identified among studies related to vocabulary building through computer games:

providing multiple ways to satisfy various learning needs and styles, and helping reduce anxiety in classes.

Supporters of games advocate that incorporating games into language instruction helps make language learning more engaging. Games provide a learner-centered environment where students have opportunities to interact with knowledge they learn, thereby improving their autonomous learning (Uzun, 2009). Through game-based

environments, students incline to experiment repetitively with their mistakes because they have control over the content and the pace of learning (Noemi, 2007). Games such as adventures, branching stories, puzzles or logic problems make sense of language learning in a variety of ways, instead of directly presenting students with the target language that they have to learn. Freiermuth (2002) claims that games are learner-centered, since they ask learners to resolve challenges without intervention from teachers. According to Uzun (2009), language learning requires learners’ willingness and enthusiasm for learning from their mistakes, and games help language teachers to develop an energetic, interactive, and interesting atmosphere in their classrooms.

The application of edutainment games in education

Technology-based tools should be properly incorporated into the curriculum and instruction to enhance student performance. The mere existence of these technology- related tools cannot guarantee effective instruction and efficient learning if they fail to be part of a coherent educational method (Bransford, 1999). Thus, understanding students’

perception of using different technology-mediated tools in the classroom helps teachers enhance their pedagogy because effective use of technology involves many teacher- oriented decisions and direct forms of teacher engagement. Questions related with the developmental appropriateness of the technological products are as important as issues that affect those who use them as tools to promote learning. This section provides a summary of advantages of using edutainment games in education.

Firstly, given many commercially available computer games and websites specifically designed for language learning, these educational games or websites fail to encourage autonomous learning (Stanley & Mawer, 2008). Hergenhahn and Olson (2001) indicate that most computer games designed for language learning follow behaviorists’

epistemology, which presents learners with a series of habit-forming modes of learning.

Such a view of language learning influenced the design of educational games and therefore repetitive language practices or drill-and-practice programs became prominent themes. The games incorporating behaviorists’ views of learning can reduce students learning motivation because of its linear emphasis on language per se instead of using language.

Secondly, context is another reason for choosing edutainment games such as online negotiation games as a medium instead of general vocabulary games. Social learning theory further explains how interactions between both environmental and cognitive

factors influence human learning and behavior (Bandura, 1968). It emphasizes that learning occurs within a social context through interacting with one another such as observing, imitation, and modeling (Abbott, 2007). Vygotsky (1978) believes everything is learning on two levels: first through interaction with others and then integrates into the individual’s mental map. Vygotsky unfolds that the socially cultural environment provides people with the cognitive tools required for learning. Likewise, social constructivists emphasize the importance of social interaction and its usefulness for understanding of the acquisition of socio-linguistic and pragmatic language competences.

They believe language competences should be acquired and mastered through interaction, communication, and assimilation of others’ speech.

Finally, exposure to authentic language input has become a key issue for successful language learning (Suparp et al., 2006). Among many different kinds of computer games, the type providing the greatest exposure to English is probably simulation (Suparp et al.,, 2006). These games engage users in role-playing and decision-making. For instance, a simulation game, Football Championship Manager 4 (CM4), was used to facilitate students’ English learning in Thailand (Suparp et al., 2006). Students can play managers of football teams through making decisions of buying or selling players, choosing a team, and selecting tactics. The study concludes that simulation games advance students’

language learning motivation much better than general educational games designed for language learning.

As Stanley and Mawer (2008) argue, the growing interest in the use of games in education in general could provide language learners with a different domain in which they practice targeted language with ease and enjoyment. However, teacher is an extremely significant actor in mediating between the “fun” and “serious” aspects of utilizing games. In his study of learning English as a second language through game- based design, Meyer (2008) emphasizes that the teacher is central to the transformation of edutainment types of games to a profound activity of learning. Gaming in the classroom should be recognized as an activity that sometimes bridges the gap between entertainment and learning as well as the gap between formal and informal learning (Meyer, 2008).

To sum up, the value of the technology is not necessarily measured by its technological excellence or astounding quality, but rather on how well the technology is integrated into the instruction and learning experience (Thornbury, Elder, Crowe,

Bennett, & Belton, 1996). Likewise, Bransford (1999) also highlights that technology- based tools can never augment student performance unless they are carefully integrated into the curriculum and utilized in terms of knowledge about learning. However, a deficiency between pedagogical approaches and game design still exists even though online games can provide engaging learning experiences for students (Kiili, 2005; Yip &

Kwan, 2006).

Methods

A. Subjects

Prospective participants were chosen from students who took the course: English as a Foreign Language (I): Reading and Writing. This class is required for all non- English major students of the researched site. Course objectives include enhancing fundamental knowledge of English grammar, developing sentence structure and written expression, and improving reading comprehension. 132 participants were from four different departments: Fine Arts and Cultural Creative Design, Environmental and Hazards-Resistant Design Introduction, Mechatronic Engineering, and Architecture.

These students are required to take English as a Foreign Language: Reading and Writing and English as a Foreign Language: Listening and Speaking for two academic years.

An after-class remedial instruction program was designed to function as the context for this research, with offering students freedom to stay or leave the program at any time.

30 targeted participants eventually constituted the participant pool because a significant portion of prospective participants were unable to stay after the end of school days.

B. Design of the study

The study took one academic year, eight months for the whole research period. The researcher selected proper cases for students to crack from the online negotiation game website in terms of content, difficulty, and students’ readiness levels. After experimenting all games from the online negotiation game website, six cases were considered proper but a little bit challenging for students. These six cases were presented to two professors with applied linguistics background, and determined appropriate for language learning.

Following with acquiring approvals from experts, a vocabulary list was created for each case. These vocabulary lists focus on listing and specifying several vocabularies and sentence structures justified challenging for student participants. They were created to provide teachers with more instructional time and teachers were informed of their freedom to use these vocabulary lists or not.

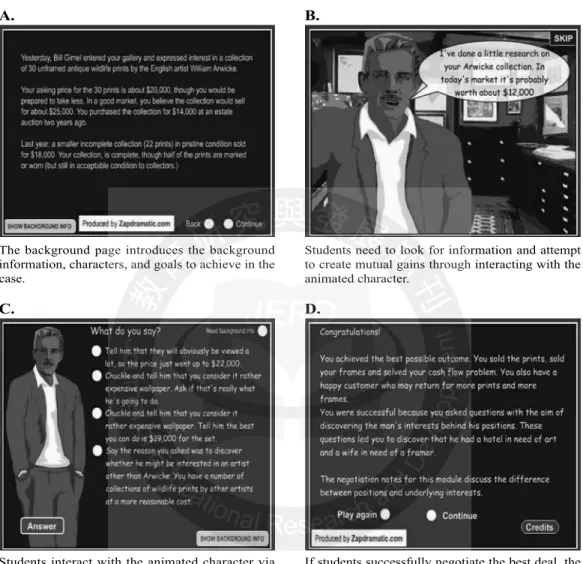

All participants were introduced and instructed details of the website of online interactive negotiation games, Zapdramatics. These games provide several case scenarios in which game stories are proceeded by interaction between players and game characters.

Through interacting with game characters, players can see how English words are used both visually and audibly. Such a game interface provides students with a simulative context to learn English vocabularies in contrast to printed materials.

The online negotiation game is played by interacting with the simulated characters by means of choosing one best method to respond from several options. The animated computer characters make statements, ask questions, use difficult tactics, express strong views, and employ challenging techniques to get the students to settle for less. Students should reach the best deal through carefully examining all given options for responding and tactically choosing ways to interact with the animated character. In each of the cases given, students progressed the game by having conversations with the simulated characters. During each conversation, students were given four choices, only one of which is correct. If students fail the game, reasons of their unsuccessful negotiation will be given. This allows students to monitor their process of making decisions and to learn from their mistakes.

According to the pedagogical perspective of the game, the online negotiation game invites students to play a variety of roles in different scenarios. Students pretend to be an employee to ask for a salary raise, an unsatisfied customer for refund, or a sales anticipating advanced performance. Through negotiating, students are exposed to large amount of English and some of which can be unfamiliar to most EFL students. In the meantime, instructors can draw upon several advanced vocabulary strategies to provide support or scaffolding such as Mandarin definition, English definition, examples of use, and pictures (Beed, Hawkins, & Roller, 1991; Eggen & Kauchak, 1999).

Three weeks are regarded as a learning unit. For the first week, subjects were introduced to the background of the targeted case for negotiation, including being given goals to achieve and were appraised the primary difficulties of the negotiation.

The related lesson plan would be given at this time to help students recognize key vocabularies emerged from the case. After introducing vocabularies and several complex sentences, the researcher demonstrated the case by playing, and attempted to engage students by inquiring their opinions for options of conversations. Throughout the meeting period, students were allowed to use online dictionaries or handouts whenever they encountered unfamiliar words.

After the researcher’s demonstration, students would be asked to try out the games in the classroom by themselves. They were instructed to jot down any unfamiliar words because targeted games cannot be paused during game characters’ dialoguing. During their experimenting with the game, the researcher would observe their interactions with games and provide academic and technical assistances when necessary. In the second week, students would be provided with a checklist that contains all of the vocabulary used in the case. The teacher would give instruction of vocabulary, phrases, and idioms, and continue with students’ case demonstrations. The whole class worked as a group to “crack” the case together. Finally, in the third week, the class would be held in the form of a conference, inviting students to share the feelings and challenges they have encountered in the case. The teacher concluded the case by reviewing the vocabulary, difficult sentences, and the rationale behind the case. A new cycle started again from the fourth week with the introduction of a new case.

The grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, 1990), a qualitative research methodology in the social sciences emphasizing the generation of the theory emerging from the data during the process of conducting research, was drawn upon, adapted, and employed in the study. Grounded theory has been employed in several studies to explore the complexity of the educational contexts involved in teaching and learning English through gaming online (Brown & Cairns, 2004; Pace, 2004; Suparp et al., 2006; Meyer, 2008). It explains an educational process of events, activities, actions, and interactions that occurs over time (Creswell, 2002). A process in grounded theory is a sequence of actions and interactions among people and events pertaining to a topic (Strauss & Corbin, 1998).

Through a systematic procedure, grounded theory helps researchers generate a theory that illustrate, at a broad conceptual level, a process, an action, or interaction about a substantive topic.

C. Interviews

Interviews were carried out in two forms: group and individual interviews. Group interviews, according to Kvale (1996), allow interaction among subjects and thus often lead to spontaneous and emotional statements about the topic being discussed. However, the group interaction can reduce the interviewer’s control of the interview situation and make data collection chaotic, causing difficulties for systematic analysis of the A.

C.

B.

D.

The background page introduces the background information, characters, and goals to achieve in the case.

Students interact with the animated character via choosing one of the options provided by the game.

Students need to look for information and attempt to create mutual gains through interacting with the animated character.

If students successfully negotiate the best deal, the points that he or she makes win the negotiation.

Figure 2. Interface of online interactive negotiation game

Note: Retrieved from http://www.zapdramatic.com. Copyright 2005 by Zapdramatic.

Reprinted with permission.

intermingling voices. To encourage interaction but orchestrate different perspectives from interviewing, this study employed both individual and group interviews as one of tool for data collection.

To avoid issues such as power struggle, a phenomenon in which participants tend to respond positively to a researcher’s questions because of fears of being punished by offering negative opinions, two teaching assistants executed all interviews in the study.

The interviews began with an open-ended question such as “How you perceive English learning through playing online negotiation games” and “Describe both advantages and disadvantages of learning English through playing online negotiation games.”

Subsequent questions were conversational in an attempt to get the interviewee to discuss further something he or she mentioned in an answer. As classroom observations accumulated, new questions arose and added for which the researcher needed answers to confirm observation conclusions and to understand what is going on in the classroom.

Eventually, a set of questions emerged from the evolving data and was used for all remaining interviewees.

Because this study aimed to capture non-English major college students’ perceptions of learning English through online negotiation games, homogenous sampling strategy was employed to select participants for this study. Homogenous sampling, according to Patton, “is the strategy of picking a small, homogenous sample, the purpose of which is to describe some particular subgroup in depth” (Patton, 2001, p. 235). Homogenous sampling strategy was considered a fit to this study because the researcher is interested in understanding how a particular group of participants (first-year and non-English major students) in a particular context (remedial instruction program) react to a treatment (online negotiation games). As Patton addresses, the point of homogenous sampling is to bring together people of similar backgrounds and experiences to participate in a group interview about major issues that affect them.

Emerging design was employed to search for samples of the student population.

As the researcher learned about and make sense of the events in the classroom and its meaning to the participants, he also looked for negative data as well as positive data by emerging theory. In other words, the researcher determined how many samples he would do by conducting interviews until nothing new was discovered. The researcher purposely selected students known to be active to express their opinions.

Ten individual interviews and six group interviews, lasting 30-45 minutes for former and 60-90 minutes for latter each, were conducted. Each interview would be concluded with the final statement that students’ opinions would not affect their grades.

Interviews occurred in student cafeteria, student lounge, or student center, and were audiotaped and later transcribed. Moreover, classroom observations were also conducted to crosscheck results obtained from interviews.

Data analysis

Open Coding

The procedures for data analysis in grounded theory involve three types of coding procedures: open coding, axial coding, and selective coding. Open coding comprises of labeling and categorizing data. Analysis of transcribed interviews and classes was coded during data collection as soon as transcriptions were available. As interview transcriptions were reviewed, concepts or themes with similar properties were grouped together. During open coding, each sentence in interview transcripts was assigned a color in terms of its topic. After all sentences of transcripts were marked, topics were then compiled, organized, and relabeled. Subsequently, these labeled sentences were developed into categories. Categories were firstly examined, then those ones with similar properties were grouped together, and finally properties of all grouped categories were reexamined as well as dimensions or ranges of the properties. Finally, matrices were constructed from the data and were used to identify patterns, comparisons, trends, and paradoxes.

In the final phase of open coding data analysis, the researcher conducted short summaries for each interview. These interview summaries allowed the researcher to restore the context for the quotes, and used them as examples in writing up the study. The researcher selected quotes from all interview transcripts, and the compilation for each quote was used to present trends, contrasts, and similarities. Matrices were constructed to reexamine the validity of emerging themes. Finally, the researcher constructed a narrative description and visual display of the findings for the research report. In this study, three major categories emerged in the open coding process were labeled because of their frequent emergences in interviews: (1) real-life related contexts, (2) underlying motivation, and (3) lack of multimedia learning experience.

Axial Coding

Once major themes were developed, a second level coding procedure named axial coding was executed. Axial coding places the data back together in new ways by associating categories. Axial coding includes identifying a single category as the central phenomenon and navigating its relationship to the other categories. The central phenomenon is identified as well as other conditions that have influences on it, the contexts in which it is embedded, the interactional approaches which it is handled, and the consequences of these approaches. In axial coding a paradigm model is created which visually portraits the relationship among the categories (Strauss & Corbin, 1990).

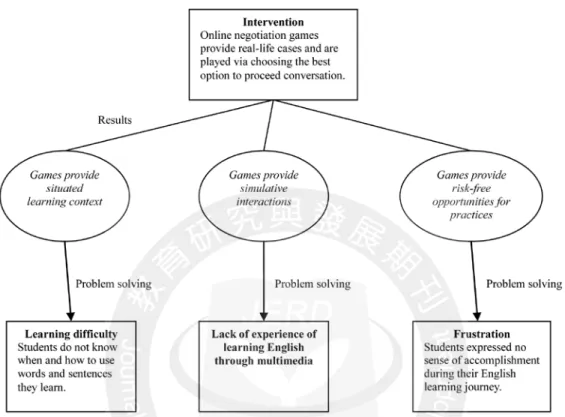

Through axial coding, we found that online edutainment games can be utilized to facilitate language learning in terms of three dimensions: providing situated context, simulative interactions, and risk-free practices.

The axial coding paradigm model for this study demonstrates the relationship between participants’ perceptions of English learning challenges and their experiences of learning English through playing the targeted games. Categories obtained in this phase indicate three potential advantages of edutainment games: situated learning context, simulative interaction, and risk-free opportunities for retry. Situated learning contexts the games show students how an English word or sentence should be used through visual and audio demonstrations. Simulative interactions encourage those students without multimedia learning experiences to explore the games more, and risk-free opportunities guarantee students of zero physical and affective setbacks if they make any “mistake”

during playing. The diagrammatic result of the axial coding for this study is shown in Figure 2.

Selective Coding

The third set of coding procedures is selective coding. In this analytic phase, the researcher attempted to develop a theory by establishing a story to connect the categories. By connecting categories, a discursive set of propositions is generated and verify the story (Strauss & Corbin, 1990). During this process, the researcher selected the core category, the central phenomenon emerged from the data, related it systematically to other categories, validated those relationships, and filled in categories that need further refinement and development. In summary, this set of coding procedures was comprised of five steps: (1) explicating the story line; (2) relating subsidiary categories around the core category, (3) relating categories, at the dimensional level, (4) validating those relationships against data, and (5) filling in categories that require further refinement or development.

Figure 3. Axial Coding Paradigm Model of non-English major freshmen’s perception of the relationship between English learning and game playing.

The researcher also established intra-rating reliability and inter-rating reliability to confirm that the coding of data is consistent across time and people. Firstly, the researcher randomly chose few of the original data (around 10 to 15 pages) and made three copies. Secondly, the researcher coded the first copy of the sample data by the devised coding scheme. Thirdly, after two weeks, the researcher coded the second copy of the same sample data. The correlation between the two coding yielded intra-rating reliability if differences between them are not significant. During the data analysis, the researcher reiterated this process to ensure the differences between each coding were negligible.

To establish inter-rating reliability, the study employed member checking to ensure that the coding is not significantly different if other people coded the same data. After the researcher completed coding two copies of sample data and confirmed intra-rating reliability, a professor specialized in qualitative inquiry was invited to code the third copy of sample data with the devised coding scheme. After the second coder completed the coding, the correlation between the researcher’s coding and the second coder’s coding served as an index of inter-coder reliability. The researcher examined whether there was any critical difference between two codings for subsequent analyses. The researcher embarked on coding all data as long as intra-rating and inter-rating reliability was established. Both inter-rating and intra-rating reliability of research results was checked and confirmed during the data analysis process in this study.

Results

In ascertaining students’ perception of experiencing online negotiation games, several saliencies emerged from interviewing data. The research question investigated participants’ perceptions toward learning English vocabularies through online negotiation games. Three major categories emerged in the open coding process were labeled:

(1) real-life related contexts, (2) underlying motivation, and (3) lack of multimedia learning experience. Furthermore, each of the three categories was positioned at the center of the exploring process and related to other categories. As a result, three themes were generated through axial coding: (1) situated learning context ameliorates English learning, (2) simulative interaction improves students’ lack of multimedia learning experience, and (3) risk-free opportunities for retry encourages stu dents to engage in exposing in edutainment context. Finally, selective coding, a process of forming a theory based on interrelationship of categories in the axial coding model, reflects students’

perceptions of learning vocabularies through online negotiation games and implications that online edutainment games provide to English instruction and curriculum.

With selective coding, four sequent themes emerge and unfold students’ perceptions of learning vocabularies through online negotiation games: (1) vocabularies learned from online negotiation games are connected to authentic contexts, (2) simulation of online negotiation games provides interactions between students and vocabularies, (3) vocabularies beyond students’ current readiness levels diminish their motivations to continue exploring games, and (4) participants’ lack of experiencing learning English through multimedia platform in their previous English learning.

Vocabularies learned from online negotiation games are connected to authentic contexts.

Through this theme, participants revealed that vocabularies used in games are commonly used in daily life. Games provided participants with a context in which they could see how certain vocabularies could be used in the real life. Moreover, games provide scenarios such as asking for raise, refund, and make-up exam to reinforce students’ recognition of usages of words. One participant deliberated:

Learning vocabularies through online games help you see how a word should be used in a dramatic way. We used to learn English vocabularies by rote memorization and repetition, and to be honest, this method will not do any good at all but decrease your motivation of English learning (20101211, interview 9).

Such a phenomenon reflects a series of learning principles of videogames that often miss in traditional classrooms (Gee, 2004). Effective learning allows students to play the role of experts who have to deal with the subject matter. Similar feedback was also reflected in another interview:

Vocabularies in the paper materials are boring, and you will not want to know those words unless teachers or parents tell you to do. However, negotiation games create a link between English words and we students.

You have to know what each word means to negotiate for the best result. Such an approach, more or less, provides me with incentives to know unfamiliar words seriously (20101212, Interview 10).

Students did not merely learn targeted vocabularies to develop their English competencies but to resolve some tasks. Since videogames require players to “play” a role, games become a good demonstration of how learning can occur in a contextualized, meaningful setting where people learn by doing and knowledge is not isolated into discrete facts but is connected to action.

Simulation of online negotiation games provides interactions between students and vocabularies.

Another salient theme emerged from data is that the interaction provided by the online negotiation games helps engage participant in vocabulary learning. The relationship between participants and vocabulary learning has been unidirectional since they started their English learning. They have been relying on rote and memorization to acquire a new word but have rarely been provided with contexts to see how certain words should be used in formal writing or conversation. In a traditional English classroom, vocabularies are learned while teachers instruct reading. Students are always given a list of English words they need to know before reading instruction. However, several interview responses expressed that learning vocabularies from negotiation games can enhance their words recognition. For instance, one of students addressed:

Learning vocabularies from simulative negotiation games is different from reading articles. Firstly, articles are not inactive but simulative environment creates dialogues between words and us. Secondly, I often get confused why certain words are used here and there in some articles but games give us a simulative environment to understand why words are used by this way.

(20101208, interview 2).

The statement above highlights students’ need of learning vocabulary through a more interactive and impressive platform. Games provide students not only with a different portal to learn vocabularies but also a different learning experience.

Furthermore, negotiation games exhibit vocabularies in a comparatively more holistic context: visual, audio, interactive, and goal-oriented context. Students can also have access to pronunciation through game character and therefore consolidate their vocabulary acquisition.

Vocabularies beyond students’ current readiness levels diminish their motivations to continue exploring games.

For this theme, participants feel that games are not interesting as they should be while more and more unfamiliar vocabularies emerge. Initially I found the game was fun. However, the more new vocabularies I encountered, the more difficult the game turns to be (20101223, interview 6).

Since the online negotiation games are not designed for EFL students, words and sentences beyond students’ current readiness levels may appear and therefore lose their power of engaging students. Although this study invited two scholars with Teaching English as a Foreign Language backgrounds to ensure educational creditability and appropriateness of the online negotiation game, several participants found numerous words in games were too challenging for them. Games can be fun but fail to stratify and differentiate words in terms of difficulty levels. For instructional implications of employing edutainment games in vocabulary acquisition, it is crucial to select and annotate words suitable for students’ levels. Therefore, games alone cannot promise students’ autonomous learning even though they are designed for this purpose. Teachers play a significant role in maximising games’ educational potential such as choosing proper games according to students’ interests, readiness levels, and learning profiles or designing lesson plans and instructional activities.

Results suggest that a more comprehensive and scaffolding curriculum and instruction should be integrated into games. In other words, more pedagogical consideration should be given to using games to introduce vocabularies in terms of the growth of students’ readiness levels. Games should not be valued merely because its capability of capturing students’ interest, time, commitment, and passion. Instead, discussions among designers of edutainment games should include students, teachers, and parents to find out how to best deliver knowledge through games. Barab, Gresalfi, and Ingram-Goble (2010) argue that designing games for academic uses should focus on creating an academically engaging environment in which students are willing to take initiatives to search for patterns in terms of disciplinary concepts and learn from mistakes. However, students’ learning styles, needs, and readiness levels should be carefully examined and understood while EFL teachers choose games for vocabulary learning. Vocabularies which are too difficult or easy for students can diminish motivation no matter how they are presented. Games appear to capture students’ attention initially but fail to sustain students’ motivation while more new words emerge.

Although the last theme below does not directly answer both research questions, it is worth noting that participants stressed the desire for having more opportunities of multimedia English learning.

Participants expressed the lack of experiencing learning English through multimedia platform in their previous English learning.

For this theme, participants point out that they had limited experience of learning English through multimedia presentation. Two mostly common multimedia used in the classroom are Microsoft PowerPoint and audio compact discs. However, utilizing software and Internet application to facilitate vocabulary learning appears to be scant in terms of participants’ past experience of English learning. As one participant unfolds:

My secondary school English teachers were so concerned about test results, and this concern made everything in their teaching extremely test-oriented.

We had to use every second of the class time efficiently, and there was no time for teachers and us to try other alternatives to learn English. We did everything in the classroom for tests. Teachers started each class with quizzes, continued with a lecture, and concluded the class with announcements for the quiz of next week. It was a routine and everything centered around standardized tests (20101227, interview 16).

This statement unfolds that most participants’ insufficient experience of learning English through multimedia could be attributed to test-oriented curriculum and instruction. Students in secondary schools are required to take standardized tests to acquire admissions to ideal senior high schools and colleges. Such an educational policy limits teachers’ instructional time allocation and implementations of activities.

Furthermore, teachers could be discouraged from attempting instructional and curricular innovation but turn to comply with conservative but promising methods such as rote memorization and drill.

Teachers and administrators’ unwillingness to try out new technologies in the classroom can be another reason to students’ lack of learning through multimedia.

Leander and Zacher (2007) find that it is often challenging to implement new technologies into classroom instruction because they entail a different spatial and temporal configuration that runs counter to the structure of traditional schools. Leander further explains that teachers who are familiar with having control over the distribution

of knowledge and the instructional order of a traditional classroom might resist technologies that redistribute their control. As one of interviewed student indicated that her high school English teachers had tight instructional schedule:

I think they (high school English teachers) would love to try something different in the classroom. However, we had lots of readings to cover at that time and daily quizzes and subsequent reviews allowed very little time to try something different. Otherwise, I believe they would try something new (20111228, interview 17).

High-staked testing and possible technological problems of using multimedia diminish teachers’ readiness to associate digital technologies into their teaching. Such a phenomenon is also reflected in Scollon and Scollons’ (1981) report in which they described teachers’ difficulties of early use of the Internet in a university setting. For instance, games tend not to be easily customizable for teachers, and those that tend to be time-consuming require a relatively high level of technical knowledge. As Leander notes, teachers and administrators are inclined to expect technologies to fit into their structure, instead of working around the new possibilities opened up by the reconfigured social organization. According to positive feedbacks received from participants, this study reveals the likelihood and necessity of designing a blended learning method by integrating online games into language learning. For instance, language teachers can design a variety of EFL contexts in which students can practice their language techniques through negotiations such as car purchase or salary raise. Since exposure to authentic use of the target language is necessary for language, negotiation games invite language learners to use targeted language to resolve potential problems in EFL contexts.

To sum up, online edutainment games can be used to facilitate language learning better with language instructors’ proper intervention. With advanced interface and multimedia presentation, numerous online games are able to trigger students’ interests for the first time but fail to sustain students’ motivation. This study found that students’

motivation of completing games diminished if the cases they chose contained many vocabularies beyond their competencies. For instance, some participants revealed that too many challenging vocabularies could impede their further exploration of cases even though they expressed strong desires to find out a solution to reach a deal. However, with teachers’ interventions, participants indicated that the interactive interface of the game can assist them to learn a new word better because they witness how the word

is used in certain context. With teachers as facilitators or coaches, online edutainment games not only enable students’ autonomous learning but also ensure their effective and efficient utilizations. Although the purpose of edutainment games is to invite autonomous learning, teachers’ interventions and alignments are necessary to ensure the extension and continuance of students’ learning. With teachers’ instructional activities, writing down favorite sentences in student journals for instance, students can not only acknowledge new vocabularies but also make their learning solid during play.

Conclusion

This study attempted to find what pedagogical implications can be generated through implementing the edutainment games in the college level remedial classes.

Results indicate the simulative and interactive characteristics render online edutainment games a useful medium for pedagogical purposes. Participants in this study specified that their vocabulary acquisition were promoted because online negotiation games provide them with a real-life scenario to witness how a word should be used. Through interacting with characters in games, students can situate themselves in a real conversation with a native speaker. Participants in this study reflect that more sample sentences and translations are unable to help them ‘acquire” the targeted words. With the games presented in the study, they are involved in the learning process and thus acquire vocabularies through monitoring, imitating, and using them in response to the simulative characters.

Results of the study can be helpful for language teachers and educational game designers. Salabery (2001) urges researchers who concern about the pedagogical effectiveness of different technologies to contemplate what technical attributes specific to the new technologies can be profitably exploited for language teaching. In this study, no participants accredit that visual display or sound effect of games help elevate their language learning. On the contrary, participants indicate the difference between games and textbooks in terms of the way they learn. This study expects to find out specific features of edutainment games and discover those factors that affect the choice of instructional medium for pedagogical purposes. With voices of participants in this study, more studies are demanded to examine and categorize different specific attributes of technologies that can be integrated into language teaching.

Furthermore, in contrast to educational games which aim to enhance language learning, edutainment games emphasize problem solving. Designers of educational games for language learning emphasize the significance of drills in certain linguistics principles such as sentences patterns, pronunciations, or spellings, and most educational games feature funny and hilarious interfaces to ensure constant and repetitious practices.

However, such a linear and monotonous design could fail to sustain and extend students’

motivation (Yip & Kwan, 2006). Furthermore, rare educational games for language learning are attractive enough to maintain sustained learning for students in the college level. The two features, game plots and significance of English as a survival tool (i.e.

a medium to obtain useful information), are overlooked in educational games. In this study, online negotiation games can trigger students’ desire to know sequences to settle a case or senses of accomplishment after solving a case. Proper edutainment games present a situated context in which students need to improve their English for survival in games.

In general, many games designed for mere entertainment have potentials of facilitating classroom instruction and enriching instructional materials (Suparp et al., 2006). Edutainment games can come from the entertainment ones if teachers find factors from the entertainment games that can be incorporated into their instruction.

However, there are two perspectives that call for our attention and more studies. Firstly, students’ positive feedbacks toward games could be caused by a shift from a traditional instructional context to something new, instead of games per se. For this reason, it is crucial to note the influence of Hawthorne effect, which illustrates subjects’ improvement or modification of their behavior due to their awareness of being experimentally measured (Mayo, 1949). Such a response could be generated from the situation that students know they are being studied, and make efforts to exhibit positive performances.

In other words, students did not actually reflect in response to any particular experimental manipulation. To diminish Hawthorne effect in this study, we adopted other multimedia instructional materials such as video clips of news or informative programs in the classroom. However, it is necessary to acknowledge the possible influence of Hawthorne effect on participants. For instance, participants’ positive feedbacks toward the game use may partially be caused by their preferences of the shift from textbooks to game, instead of the game itself. Therefore, long-term studies are required to examine whether language teaching or learning through games has significant impact on students’

performance to diminish Hawthorne effect. One potential direction for the future game study can be observing students’ language development through monitoring variations of their academic performance.

Secondly, teachers play dominant role during using games to facilitate language teaching. Games should be used to assist language teaching instead of replacing teachers. Teachers need to design instructional activities to better associate games into their language teaching and explore factors in games that can be used for educational purposes. By doing so, teachers can not only have a variety of game options but also further their knowledge of exploiting games to assist their teaching. Yip and Kwan (2006) encourage language teachers to navigate games that students feel interested and figure out how those games can be drawn upon to elevate their instruction.

Throughout the study, several game characteristics can be used to trigger students’

motivations to nurture their EFL communicative practices. The game is played by selecting one of the best conversational options in response to the game character.

These conversational options can be associated with conversational practices in the EFL classroom, and demonstrate models of making responses. Also, negotiation-oriented activities can be used in the conversation classes to improve students’ engagement.

Students practice their communicative competencies through playing different sides with conflicting interests and attempt to create a win-win result by negotiation. Finally, the ubiquity of online negotiation games extends students’ learning and makes anywhere and anytime learning possible. With teachers’ deliberately designed tasks, students’

autonomous learning is likely to trigger although they are not situated in the classroom.

In conclusion, this study argues that simulative interaction provided by online edutainment games encourages students’ vocabulary acquisition and requires further investigation. The online negotiation games used in this study model complex worlds where players can experiment with their prior knowledge and expectations, and where skills are used to solve problems within a context meaningful to the game. However, the effectiveness of online negotiation games can be diminished without proper teacher- oriented instruction and curricular planning. Although games have great potential of stirring up reactions, there are still numerous attributes of games that require our further exploration and articulation. For the future study, identification and analysis of specific attributes of different types of games that serve pedagogical purposes will be investigated. As Hung (2011) cautions, what games are depends on who we are as users and what we do with them. The success of using technologies in language learning is contingent upon successful accomplishment of related activities than on the technology itself. Furthermore, understanding the relationship between participants’ backgrounds such as majors in schools and degrees of students’ receptions of learning English via online games is another direction for the future exploration.

References

Abbott, L. (2007). Social learning theory. Retrieved from http://teachnet.edb.utexas.edu/~lynda_

abbott/Social.html

Ang, C. S. & Zaphiris, P. (2009). Simulating social networks of online communities: Simulation as a method for sociability design. Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT, 5727, 443- 456.

Bandura, A. (1968). A social learning interpretation of psychological dysfunctions. In P. London

& D. L. Rosenhan (Eds.), Foundations of Abnormal Psychology, 293-344 New York, NY:

Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Barab, S., Gresalfi, S, & Ingram-Goble, A. (2010). Transformational play: Using games to position person, content, and context. Educational Researcher, 39(7), 525-536.

Barron, B.J., D.L. Schwartz, N. J. Vye, A. Moore, A. Petrosino, L. Zech., J. D. Bransford, and Cognition and Technology Group at Vanderbilt. (1998). Doing with understanding: Lessons from research on problem and project-based learning. Journal of Learning Sciences 7 (3 and 4): 271-312.

Beatty, K. (2003). Teaching and researching computer-assisted language learning, 2nd edition.

London, England: Pearson Education.

Beed, P. L., Hawkins, E. M., & Roller, C. M. (1991). Moving learners toward independence; the power of scaffolded instruction. Reading Teacher, 44(9), 648-655.

Bereiter, C. & Scardamalia, M. (1993). Surpassing ourselves: An inquiry into the nature and implications of expertise. Chicago and La Salle, IL: Open Court.

Bransford, J. (1999). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC:

National Academy Press.

Brown, E. & Cairns, P. (2004, April). A grounded investigation of game immersion, Paper presented at the CHI '04 extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems, Vienna, Austria (pp. 1297-1300). New York, ACM Press.

Chapelle, C. (2005) Computer-assisted language learning. In E. Hinkel (ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning, (pp. 743-755). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Creswell, J. (2008). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle Creek, NJ: Pearson Education.

de Freitas, S. & Griffiths, M. (2008). The convergence of gaming practices with other media forms: What potential for learning? A Review of the Literature. Learning, Media and Technology, 33(1), 11-20.

de Groot, A. (2000). What is hard to learn is easy to forget: The roles of word concreteness, cognate status, and word frequency in foreign-language vocabulary learning and forgetting.

Language Learning, 50, 1-56.

Egbert, J. (2005). CALL essentials: Principles and practice in CALL classrooms. Alexandria, VA: TESOL.

Eggen, P. D., & Kauchak, D. (1999). Educational psychology. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Freiermuth, M. (2002). Connecting with computer science students by building bridges.

Simulation & Gaming, 3(3), 299-315.

Fry, H. & Ketteridge, S. (1999). A handbook for teaching and learning in higher education:

London, England: Kogan Page.

Gee, P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. New York, NY:

Palgrave Macmillan.

Gee, P. (2004). Situated language and learning: A critique of traditional schooling. New York, NY: Routledge.

Gee, P. (2005). Learning by Design: good video games as learning machines. E-Learning, 2(1):

5–16.

Ghani, J. A. (1991). Flow in human-computer interactions: test of a model. In J. Carey (Ed.), Human factors in management information systems: emerging theoretical bases. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Guthrie, L. & Richardson, S. (1995). Turned on to language arts: Computer literacy in primary grades. Educational Leadership, 53(2), 14-17.

Hergenhahn, R. & Olson, H. (2001). An introduction to theories of learning (6th ed). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hmelo, C., & William, S.(1998). Special issue: Learning through problem solving. The Journal of the Learning Sciences 7(3 and 4).

Hu, H. P. & Deng, L. Y. (2007). Vocabulary acquisition in multimedia environment. US-China Foreign Language, 5(8), 55-59.

Huang, C. P. (2010). Making English remedial instruction work for low-achieving students : An empirical Study. Journal of Lunghwa University of Science and Technology, 29, 167-183.

Hung, C. Y. (2011). The Work of Play: Meaning-Making in Videogames. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Johnson, S. (2006). Everything bad is good for you: How today’s popular culture is actually making us smarter. London, England: Riverhead.

Kafai, Y. B. (1995). Minds in play: Computer game design as a context for children’s learning.

Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kiili, K. (2005). Digital game-based learning: Towards an experiential gaming model. Internet and Higher Education, 8, 13-24.

Kvale, S. (1996). Interviews: An introduction to qualitative research interviewing. London, England: Sage.

Leander, K. M. & Zacher, J. (2007). Literacy, identity, and the changing social spaces of teaching and learning. In L. S. Rush, A. J. Eakle, & A. Berger (Eds.), Secondary school literacy:

What research reveals for classroom practices (pp. 138-164). Urbana, IL: National Council of Teachers of English.

Liou, C. (1997). The impact of WWW texts on EFL learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 10(5), 455-478.

Martinez, P. (2001). Improving student retention and achievement: What we know and need to find out. London, England: Learning Skills Development Agency.

Mayo, E. (1949). Hawthorne and the western electric company. The social problems of an industrial civilisation. Oxford, England: Routledge.

Meyer, B. (2008). Learning English through game-based design - reflections on p e r f o r m a n c e and teacher/learner roles: Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on E-learning, Agia Napa, Cyprus.

Miyagi, T. (2006, May). Technology-enhanced collaborative projects and Internet-based instruction. Paper presented at the conference of the MATESOL program, San Francisco State University, San Francisco, CA.

Noemi, D. (2007). Computer-assisted language learning: Increase of freedom of submission to machines? Retrieved December 30, 2011, from http://www.terra.es/personal/nostat.

Nunan, D. (2006, March). TESOL’s most daring ideas. Paper presented at Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages, Tampa, FL.

Pace, S. (2004). A Grounded Theory of the Flow Experiences of Web Users. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 60(3), 327-363.

Pan, Z. (2006). Special issue on edutainment (E-learning and game). Computers & Graphics, 30, 1-2.

Patton, M. (2001). Qualitative research and evaluation methods (3rd Ed). Thousands Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Prensky, M. (2006). “Don’t bother me Mom, I’m learning!” How computer and video games are preparing your kids for twenty-first century success and how you can help! St. Paul, MN:

Paragon.