CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter reviews the previous studies of learning styles and multiple intelligences. In section 2.1, previous studies on learning styles and their relationship to EFL English learning will be discussed. In section 2.2, the MI theory and its relationship to EFL/ESL English learning will be described. In section 2.3, three in-depth studies (Milgram & Price, 1993; Chang, 1998; Tsao, 2002) of the relationship between EFL English proficiency and learning styles /multiple intelligences will be reviewed. Finally in section 2.4, a summary of this chapter will be given.

2.1 Issues in Learning Styles

Many studies have shown that leaning styles play a vital role in the process of language learning (Dunn & Dunn, 1979; Park, 1997, 2000). The following sections focus on the relationship between EFL English learning and field dependence/independence, perceptual preferences, preferring learning alone/in groups, and motivation.

2.1.1 Field Dependence/ Field Independence1

Field Dependence (FD)/Field Independence (FI) is the construct which has been

1 Field dependence refers to a learning style in which a learner tends to look at the whole of a learning task which contains many items. The learner has difficulty in studying a particular item when it occurs within a field of other items. Field independence refers to a learning style in which a learner can identify or focus on particular items and is not distracted by other items in the context (Richards et al., 1998).

theorized as being related to language learning more than two decades ago (Witkin, 1976). Most researchers have found that a tendency towards FI helps the learner with conventional classroom learning (Alptekin & Atakan, 1990). It has been believed that FI individuals might be good at language learning activities such as finding patterns, organizing data to make generalizations and learning rules. On the other hand, FD individuals are thought to have an interpersonal orientation such as interacting with native speakers. Several studies have been carried out to see if that FI learners do better on language tests that encourages a focus on form while FD learners do better in tests concerning oral communication. Hansen & Stansfield (1981) explored the relationship between field independence and foreign language achievement. Their results indicated that field independence was correlated with linguistic competence, measured by students’ performance on written examinations, as well as integrated competence, measured by students’ final course grades and scores on a cloze test. Hansen (1984) also analyzed the relationship between field sensitivity and cloze test performance for 286 subjects from six Pacific island cultures.

It was found that field independence tended to go with good scores on the cloze test.

Abraham (1985) explored FI/FD in relation to grammar teaching methods and discovered that FI students did well under deductive, rule-oriented instructions.

Another investigation of 61 adult ESL students by Chapelle and Roberts (1985) found that FI was positively correlated with students’ TOEFL scores. Similarly, Jamieson (1992) using 46 adult ESL learners found that FI was positively related to student’s TOEFL scores, though it was not predictive of improvement over a semester of L2 study.

However, a challenge has been posed on the use of FI/FD in second language acquisition by Griffiths and Sheen (1992). They argued that the concept has not been well defined in the research and it is no longer of much interest within the

discipline of psychology (Cook, 2001).

2.1.2 Perceptual Preferences

According to Dunn (1983, 1984) and Reinert (1976), learners have four basic perceptual learning channels: auditory2, visual3, tactile4, and kinesthetic5. Many researchers have explored the perceptual learning styles6 of ESL/ EFL learners. For example, Reid (1987) investigated 1388 ESL college students’ perceptual learning styles and found most of them were strongly kinesthetic and tactile. Paralleling Reid’s (1987) findings, Stebbin (1995) examined 660 ESL college students and found kinesthetic and tactile learning styles were strongly preferred. Similar findings were obtained in Rossi-Le’s (1995) study that the majority of the 147 ESL adult immigrants expressed a major learning-preference for the tactile and kinesthetic learning as well as in Park’s (1997 & 2000) studies that kinesthetic learning was preferred the most.

However, Cheng (1997) explored 140 Taiwanese college students’ learning styles and found that the students did not show particular preferences for their perceptual learning. Similarly, no specific learning styles of the subjects were found in Lin and Shen (1996).

A great number of studies have also been carried out to further investigate the relationship between perceptual learning styles and ESL/EFL English proficiency.

Park (1997) investigated 1,283 ESL students in secondary schools and found that the

2 Auditory learners refer to learners who learn best from ear-hearing. They learn more effectively through listening to lectures, tapes, etc.

3 Visual learners refer to learners who learn well through reading or having visual contact with words.

4 Tactile learners refer to learners who learn well by doing “hands-on” activities, such as working on experiments, building models, etc.

5 Kinesthetic learners refer to learners who learn best by whole-body movement through participating in activities such as role-play.

6 Perceptual learning styles refer to the variations among learners in using one or more senses to understand, organize, and retain experience (Dunn & Dunn, 1979). The sensory channels through which each individual best absorbs and retains new information and skills are identified as “modality strength”, which vary considerably among learners and evolve with age.

high achievers had major preferences for auditory and individual learning. Tsao (2002) used Reid’s (1984) Perceptual Learning Style Preference Questionnaire (PLSPQ)7 to explore the relationship between 346 Taiwanese senior high students’

learning styles and their English achievement. The result showed that the students’

English achievement was significantly correlated to their auditory, visual and individual learning styles. Moreover, similar to Park’s (1997) findings, the high achievers showed a significantly positive preference for auditory and individual learning. Different from Park’s (1997b) and Tsao’ s (2002) findings, Ke (2002) adopted Kinsella’s (1993) Perceptual Learning Preferences Survey8 to examine 161 Taiwanese junior high school students. It was found that the students with preferred visual learning styles performed better on English tests. Chang (1998) investigated 95 Taiwanese English-major freshmen’s learning styles using Oxford’s (1993) Style Analysis Survey9 and their TOEFL scores and found that the students’ TOEFL scores were significantly related to their learning styles. More specifically, there was a significant correlation between global, intuitive, hands-on (tactile) learning style and listening ability. In addition, the total scores of TOEFL were correlated with global and hands-on (tactile) learning styles. Chen (1999) used the Learning Channel Preference Checklist (LCPC)10 designed by O’Brien (1990), discovering that most of the 187 Taiwanese junior high school students preferred a visual learning style.

Besides, the students having a similar learning style preference with their teachers tended to have a better academic achievement in English. Oxford et al. (1993)

7 The PLSPQ consists of five groups of statements randomly arranged to cover six learning style preferences: visual, auditory, tactile, kinesthetic, individual, and group learning.

8 The questionnaire consists of 32 statements randomly arranged to cover four learning style preferences: visual, auditory, tactile, and kinesthetic.

9 The SAS is composed of 110 statements classified into three subparts: perceptual (visual, auditory, and hands-on), affective (extroverted/introverted), cognitive (intuitive/concrete, closure/openness, global/analytical).

10 The LCPC consists of 36 statements covering three categories of learning styles: visual, auditory, and haptic learning.

studied 107 high school students learning Japanese, using O’Brien’s LCPC. The results showed that visual learning styles had the strongest correlation with Japanese achievement test scores.

However, Park (2000) investigated the perceptual learning style preferences of 738 Southeast students with Reid’s (1984) PLSPQ and found no differences among high-, middle-, and low-achieving groups, though a major preference for kinesthetic learning was identified. Milgram & Price (1993) looked into the learning styles of 985 Israeli gifted adolescents, using the Learning Style Inventory11 (Dunn et al., 1984) to examine if there were differences in learning styles. It was found that those gifted in foreign language showed no significant preferences for perceptual learning styles.

Thomas et al. (2000) examined the learning style preferences of 44 Japanese ESL college students, using Oxford’s (1993) SAS and Reid’s (1984) PLSPQ to measure the subjects’ learning styles and their achievement was measured by grades and the results of TOEIC (Test of English for International Communication). No strong relationship was found between learning style and TOEIC scores in their study.

However, there was a significant association between a kinesthetic style preference and higher grades in the practical, skill-based English courses. Likewise, Cheng (1997) used Reid’s (1984) PLSPQ to explore 140 Taiwanese college students’

learning styles and found that their learning styles were not directly related to their English academic achievement, but were strongly related to tolerance of ambiguity.

To sum up, it is obvious that the results were not consistent. Therefore, more research on the relationship between perceptual learning styles and ESL/EFL English proficiency is needed.

11 The LSI is a self-report instrument on which each subject is asked to rate 104 items on a five-point Likert scale from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5).

2.1.3. Preferring Learning Alone/ in Groups

In addition to perceptual preferences, students’ school achievement is also influenced by sociological factors; some may prefer group learning style while others enjoy individual learning. Price (1980) found that many students in grades 3-8 learned better in small, well-organized groups than either alone or with the teacher.

However, students from grades 9-12 learned better alone. Milgram & Price (1993) discovered that the academically high achievers expressed greater preference to study alone without the presence of authority figures. Reid (1987) found that ESL students in U.S.A showed a negative preference for group learning. Park’s (1997) study found that the high achievers had major preferences for individual learning while the low achievers preferred group learning. Likewise, Tsao’ s (2002) study indicated that the low achievers preferred group learning styles the most. In sum, most of the researchers found that high achievers preferred individual learning while low achievers preferred group learning.

2.1.4. Motivation

Motivation is considered one of the most important variables in language learning (Brown, 1994; Cook, 2001). There has been a great deal of research on the role of motivation and attitudes in SLA. The overall findings show that positive motivation and attitudes are related to success in SLA (Gardner, 1985). Furthermore, high motivation can compensate considerable deficiencies both in one’s language aptitude and learning conditions (Tremblay & Gardner, 1995). In their seminal work, Gardner and Lamber (1972) emphasized that “motivational factors can override the aptitude effect” (Dornyei, 1998b, p.117). Dörnyei also noted, “ motivation is one of the main determinants as second/foreign language learning achievement” (1994, p.273). Several studies investigated the relationship between motivation and

achievement and a significant correlation between the two has been documented (Clement et al. 1980; Gardner, 1985; Gardner & MacIntyre, 1991). Milgram &

Price’s (1993) study showed that those gifted in foreign language were more highly motivated than their nongifted counterparts. Tremblay & Gardner ’s (1995) results indicated that the motivational behavior was a significant determinant of achievement.

In addition, Cheng (1993) examinined the association between motivation and attitude to English achievement among 107 cadets found a strong association between students’ motivational intensity and their EFL achievement. Similarly, Peng (2002) investigated 326 senior high school EFL learners and discovered that learners’

motivational intensity had a significant and positive correlation with achievement.

All in all, a learning style is a complex, multifaceted construct, and diverse variables highlight different aspects of its complexity. To teach more effectively, instructors need to know more about the differences in learning styles and their effects on students’ English achievement.

2.2 Issues in the MI theory

To have an insight into the theory of multiple intelligences, what follows in this section is the relevant literature. The following sections focus on the theoretical basis, essence and myths of the MI theory.

2.2.1 Theoretical Basis of the MI Theory

Gardner’s theory is based on a synthesis of evidence from diverse sources, including findings from biological science, traditional psychology, developmental psychology, and logical analysis. To provide a sound theoretical foundation for his MI theory, Gardner set up some basic tests that each intelligence had to meet to be considered an intelligence. The criteria he used included the following eight factors:

(Armstrong, 2000, pp. 3-8; Gardner et al., 1996, pp.203-205):

1. Potential isolation by brain damage. Gardner worked with individuals who had suffered accidents or illness that affected specific areas of the brain when working at the Boston Veterans Administration. In several cases, brain lesions seemed to have selectively impaired one intelligence while leaving all the other intelligences intact. For example, some stroke patients may have no problem speaking but lose their senses of direction, which supports Gardner’s notion of the existence of eight relatively autonomous brain systems.

2. The existence of savants, prodigies, and other exceptional individuals.

Savants are people who demonstrate superior abilities in one intelligence while their other intelligences function at a low level. Among these special populations, certain capacities are operating in isolation from others. For instance, some savants may be able to do well on calculating numbers or composing music but have poor peer relationship, low language functioning, and a lack of insight into his/her own life.

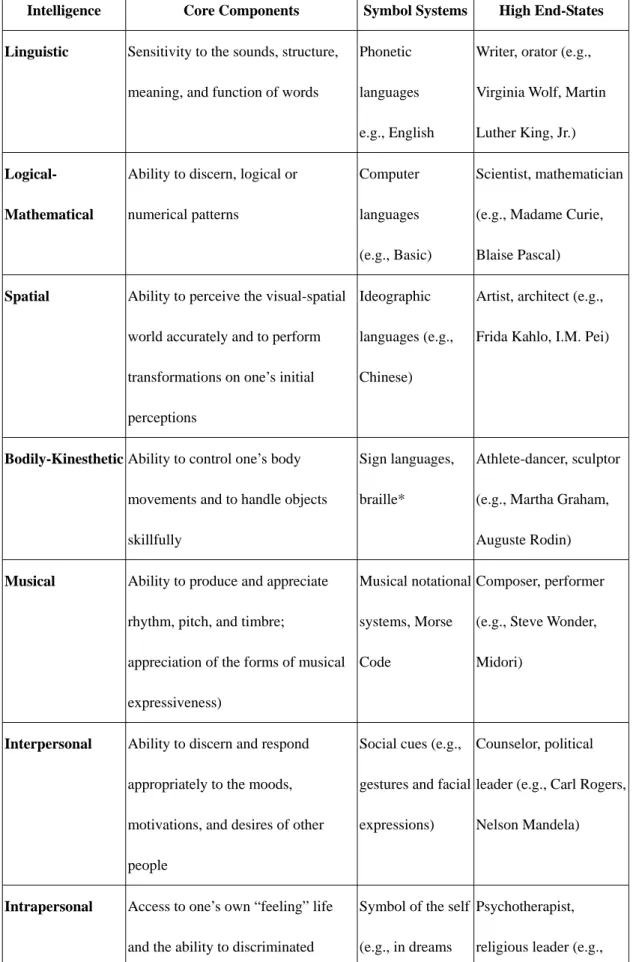

3. An identifiable core operation or set of operations. Gardner also looked for evidence in information processing mechanisms. He believed that the proposed intelligences have some core information processing operations, such as sensitivity to pitch in music intelligence or ability to imitate others’ physical movements in bodily-kinesthetic intelligence. Table 2-1 shows examples of the core components for each intelligence:

Table 2-1 MI Theory Summary Chart (cited from Armstrong, 2000, p.4)

Intelligence Core Components Symbol Systems High End-States

Linguistic Sensitivity to the sounds, structure,

meaning, and function of words

Phonetic

languages

e.g., English

Writer, orator (e.g.,

Virginia Wolf, Martin

Luther King, Jr.)

Logical- Mathematical

Ability to discern, logical or

numerical patterns

Computer

languages

(e.g., Basic)

Scientist, mathematician

(e.g., Madame Curie,

Blaise Pascal)

Spatial Ability to perceive the visual-spatial

world accurately and to perform

transformations on one’s initial

perceptions

Ideographic

languages (e.g.,

Chinese)

Artist, architect (e.g.,

Frida Kahlo, I.M. Pei)

Bodily-Kinesthetic Ability to control one’s body

movements and to handle objects

skillfully

Sign languages,

braille*

Athlete-dancer, sculptor

(e.g., Martha Graham,

Auguste Rodin)

Musical Ability to produce and appreciate

rhythm, pitch, and timbre;

appreciation of the forms of musical

expressiveness)

Musical notational

systems, Morse

Code

Composer, performer

(e.g., Steve Wonder,

Midori)

Interpersonal Ability to discern and respond

appropriately to the moods,

motivations, and desires of other

people

Social cues (e.g.,

gestures and facial

expressions)

Counselor, political

leader (e.g., Carl Rogers,

Nelson Mandela)

Intrapersonal Access to one’s own “feeling” life

and the ability to discriminated

Symbol of the self

(e.g., in dreams

Psychotherapist,

religious leader (e.g.,

among one’s emotions; knowledge of

one’s own strengths and weaknesses

and artwork) Sigmund Freud, the

Buddha)

Naturalist Expertise in distinguishing among

members of a species; recognizing

the existence of other neighboring

species; and charting out the relations

of several species

Species

classification

systems; habitat

maps

Naturalist, biologist,

animal activist (e.g.,

Charles Darwin, Jane

Goodall)

* Recent research suggests that many sign languages, such as American Sign Language, have a strongly linguistic basis as well (see Sacks, 1990)

4. A distinctive developmental history, along with a definable set of expert

“end-state” performances. Gardner suggested that an intelligence has its own developmental trajectory. That is, each intelligence has its own time of arising, peaking, and declining. Musical composition, for instance, is among the earliest activities to develop to a high level of proficiency and seems to remain relatively robust into old age. By studying the “end-states” of intelligences in the lives of exceptional individuals, we can see best see the intelligences working at their zenith (Gardner, 1994). Table 2-1 includes examples of the end-states for each intelligence.

5. An evolutionary history and evolutionary plausibility. Gardner looked for origins of intelligences in the evolution of human beings or other species that predate humans. For example, spatial intelligence can be studied in the cave drawings of Lascaux. Similarly, the existence of bird songs supports the notion of a separate human musical intelligence.

6. Support from experimental psychological tasks. Gardner suggested that intelligences function independently from one another. For example, in studies

of cognitive abilities such as memory and perception, we can see that some people may have a superior memory for words but not for faces; others may have acute perception of musical sounds but not for numbers. Each of these cognitive faculties is intelligence-specific.

7. Support from psychometric findings. Although Gardner has criticized psychometric assessment (1993a, 1993b) and has been an ardent supporter of alternatives to formal testing, he suggests that we can look at many existing standardized tests for support of the MI theory. For example, the Wechsler Intelligence Sale for Children includes sub-tests that assess linguistic intelligence, logical-mathematical intelligence, spatial intelligence (e.g., picture arrangement), and bodily-kinesthetic intelligence (e.g., object assembly).

8. Susceptibility to encoding in a symbol. According to Gardner, one of the best indicators of intelligent behavior is the ability to use symbols or notational systems. For instance, linguistic intelligence includes a number of spoken and written languages, such as English and Chinese. Table 2-1 shows examples of the symbol systems for the eight intelligences.

2.2.2 Essence of the MI Theory

To have a deeper insight into the MI theory, four key points are summarized as follows (Armstrong, 2000, pp.8-9; Gardner, 1993b, pp.5-12; Krechevsky & Seidel, 1998, pp.19-21):

1. Each individual possesses all eight intelligences. Gardner believed that everyone possesses the eight intelligences to some extent and most people appear to excel within one or two intelligences. Furthermore, he proposed, “ We are all so different largely because we all have different combinations of intelligences”

(Gardner, 1993b, p.12). In developing the eight intelligences, most people are in the middle of the situation—being highly developed in some intelligences, modestly developed in others, and relatively underdeveloped in the rest.

2. Intelligences change and grow in response to a person’s experiences.

According to Gardner, most people can develop each intelligence to an adequate level of performance if given the appropriate encouragement, enrichment, and instruction.

That is, intelligences are educable, resulting from “a constant interaction among biological and environmental factors”(Krechevsky & Seidel, 1998, p.21).

3. Intelligences are highly contextualized, working together in complex ways.

Although each of the intelligences is relatively independent of the others, they always complement each other and any sophisticated adult role will need a combination of several of them. An intelligence never exits in isolation from other intelligences, because all tasks, roles, and products in our society require a combination of intelligences, with one or more highlighted. Therefore, intelligences always interact with one another.

4. There are many ways to be intelligent within each intelligence. There is no standard set of attributes that one must have in order to be considered intelligent in a specific intelligence. The rich diversity of ways needs to be developed for people to show their gifts within intelligences as well as between intelligences.

2.2.3 Myths of the MI Theory

Since there have emerged over the years several understandings and misunderstanding about the MI theory since Gardner (1983) proposed it, it is necessary to clarify the ideas of the MI theory for teachers and educators. Eight common myths that have grown up about multiple intelligences, accompanied by corresponding realities are as follows (Gardner, 1995):

1. Now that seven intelligences have been identified, one can create seven tests and secure seven scores. In Gardner’s opinion, traditional paper-and pencil IQ tests are a decontexualized exercise using materials that are unfamiliar to the testees by design. He suggested that intelligences be assessed “in ways that examine the intelligence directly rather than through the lens of linguistic or logical intelligences”(Gardner, 1995, p.202). In addition, it is best to assess intelligences in a comfortable setting with materials and cultural roles that are familiar to the testees.

2. An intelligence is the same as a domain or a discipline. According to Gardner, an intelligence is a biological and psychological potential while a domain is an organized set of activities within a culture than can be realized through the use of several intelligences. That is, a particular intelligence can be put to work in numerous domains. Hence, an intelligence is different from a domain.

3. An intelligence is the same as a “learning style”, a “cognitive style,” or a

“working style.” A style refers to a general approach that an individual can apply equally to all manner of content. In contrast, an intelligence is a capacity that is geared to a specific content in the world. In Gardner’s view, the relationship between the concept of intelligence and that of style needs more empirical evidence.

4. The MI theory is not empirical. Gardner argued that the eight intelligences were identified and described based on hundreds of empirical studies concerning brain science, psychology, anthropology, and related fields. Nevertheless, the MI theory is being reconceptualized and revised in light of new findings from the laboratory and actual classroom experiences.

5. The MI theory is incompatible with general intelligence, with hereditarian accounts, or with environmental accounts of the nature and causes of

intelligence. The MI theory questions the province and explanatory power of intelligence instead of the existence of it. Therefore, the MI theory is neutral on the question of heritability of particular intelligences, focusing on the interaction between genetic and environmental factors.

6. Broadening the notion of intelligence, the MI theory includes all the psychological constructs and weakens the useful and usual connotation of intelligence. Gardner believed that the traditional definition of intelligence narrowly constricts people’s view of human capacities. However, the MI theory makes no claims to deal with issues beyond the intellect, such as personality, will, morality, attention, motivation, and other psychological constructs.

7. There is a ninth (or tenth) intelligence. Gardner has recently discussed the possibility of a ninth intelligence - existential intelligence12 (Gardner, 1999b).

In spite of this, he has not fully qualified the existential intelligence for entry into his MI theory because it is not a “perfect fit” in terms of his criteria (Armstrong, 2000).

8. There is a single educational approach based on the MI theory. Gardner argued that there always existed “a gulf between psychological claims about how the mind works and educational practices” (Gardner, 1995, p.206). Educators should determine the use to which the MI theory can and should be put. They should bear in mind that the MI theory is by no means an educational prescription.

To sum up, the MI theory provides a framework for individualizing education by helping us understand the full range of students’ intellectual strengths. There have

12 Gardner defines existential intelligence as “a capacity to locate oneself with respect to the furthest reaches of the cosmos—the infinite and the infinitesimal—and the related capacity to locate oneself with respect to such existential features of the human condition as the significance of life, the meaning of death, the ultimate fated of the physical and the psychological worlds, and such profound experiences as love of another person or total immersion in a work of art” (Gardner, 1999b, p.60).

been a few scholars examining their relationship to second language learning. In fact, Gardner attached some important attributes crucial to L2 success. For instance, bodily-kinesthetic intelligence has been discussed related to the learning of phonology.

Interpersonal intelligence obviously plays an important role in communication with others. “Even spatial intelligence may assist the second culture learner in growing comfortable in new surroundings” (Brown, 1994, p.94). Nevertheless, most of the ESL studies related to multiple intelligences involve the application or verification of the MI theory to English teaching in the classroom (Chang, 2002; Tai, 2002). Few empirical studies deal with the direct link between multiple intelligences and ESL/

EFL English proficiency. In the next section, in-depth studies of the relationship between EFL English proficiency and learning styles /multiple intelligences will be reviewed.

2.3 Previous Studies of the Relationship between English Proficiency and Learning Styles /Multiple Intelligences

In this section, three empirical studies of the relationship between EFL English proficiency and learning styles /multiple intelligences are discussed.

2.3.1 Milgram & Price (1993)

Milgram & Price’s (1993) study probed into the learning styles in Israeli gifted adolescents13 characterized by a wide variety and range of abilities postulated by Milgram in her 4 x 4 model14 (1989, 1991a). Their purpose was to examine if there

13 According to Dunn et al. (1992), giftedness is different from intelligence. When talent, a developed potential, is unusual and has been demonstrated over time, it is recognized as giftedness.

14 Milgram postulated a 4x4 model of the Structure of Giftedness (1989, 1990a, 1991a) in which giftedness is depicted in terms of four categories (general intellectual ability, specific intellectual ability, general creative thinking, and specific creative talent), four ability levels (non-gifted, mild, moderate, profound), and three environments (school, home and community) embedded in a framework of individual differences.

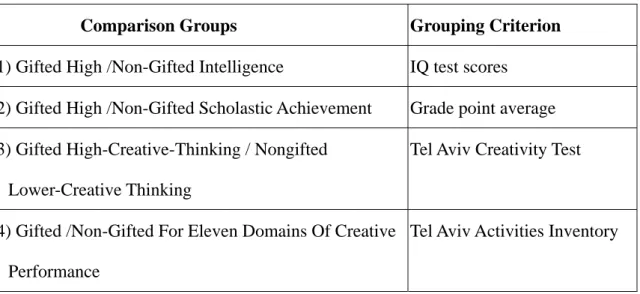

were differences in learning styles by conducting fourteen separate analyses: IQ, school grades, creative thinking, and eleven domains of creative performance (“multiple intelligences”): science, mathematics, computer, social leadership, dance, music, art, literature, foreign languages, drama, and sport.

The subjects were the entire student population (N=985) in grades 7-12 of a Israeli Tel Aviv junior-senior high school. They were further divided into four groups according to their performances on the four criterions (See Table 2-2): the Learning Style Inventory15 (Dunn et al., 1984), the Tel Aviv Activities Inventory16 (Milgram, 1990b), the Tel Aviv Creativity Test17 (Milgram & Milgram, 1976a), the Milta Measure of General Intelligence18 (Ortar 1980), and school grades in Hebrew literature, Hebrew language, mathematics, and foreign language (English). The subjects with a score in the upper 20 percent of each distribution were designated as gifted.

Table 2-2 The Grouping of the Subjects

Comparison Groups Grouping Criterion

(1) Gifted High /Non-Gifted Intelligence IQ test scores (2) Gifted High /Non-Gifted Scholastic Achievement Grade point average (3) Gifted High-Creative-Thinking / Nongifted

Lower-Creative Thinking

Tel Aviv Creativity Test

(4) Gifted /Non-Gifted For Eleven Domains Of Creative Performance

Tel Aviv Activities Inventory

15 The LSI was a self-report instrument on which each subject was asked to rate 104 items on a five-point Likert scale from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (5).

16 The instrument was a self-report biographical questionnaire designed to measure the extracurricular interests, activities and accomplishments of adolescents. It consisted of two parts: Part A contained 62 items that assess nonacademic accomplishments in 11 areas and Part B had items in which the subjects had to elaborate on the activities they reported in Part A.

17 In TACT, the subjects were asked to generate as many responses as they could to a variety of verbal and figural stimuli.

18 It consisted of tests on general information and vocabulary.

Table 2-3 presents the results of the major learning style elements19 differentiating between the gifted and nongifted learners in Israel. For group (1), it was found that the gifted high-intelligence learners were less conforming, had stronger preference for independent learning without peers or authority figures present, and expressed a higher preference for visual and kinesthetic–oriented learning.

Table 2-3 Learning Style Elements That Differentiate Between Gifted and Nongifted Learners in Israel: Relative Contribution to Differentiation (cited from Milgram & Price, 1993, p. 145)

Elements

IQ Academic Creative Science Math Computer Social Music Art Dance Drama Sport Literature Foreign**

Overall Motivation 8 2* I* 9 4 3 5 I*

Parent Figure Motivated 10 3 4 4 8 6 7 8*

Teacher Motivated 9 4* 8* 8* 8* 9* 5* 9* 12* 7*

Persistence 5 6* 10 1 2* 5

Responsibility /Conformity 7 10* 6 2* 4* 9*

Structure 2 8 2

Alone/Peer 13 1 11* 5* 5 10

Authority Figures 4 7 8 7 7 3 3* I* 3 6

Auditory 2 5* 2* 5*

Visual 3* 6* 6 4

Tactile 11 I* I* 2* 2* I* I* 9* I* 6

Kinesthetic 12* 4* 3* I* 11* 6* 10 4* 6 2*

19 Table 2-9 only lists the 12 learning style elements which are more related to the present study.

* indicates gifted higher than nongifted.

** indicates the gifted students in foreign language.

With regard to group (2), the academically achieving gifted were more self and teacher motivated, expressed greater preference for studying alone without the presence of authority figures, and preferred visual-oriented learning. It is reasonable to view high academic achievement as reflecting both ability and motivation. The findings supported the notion that high scholastic achievers were found to be more highly self- and teacher-motivated than the low-achieving comparison groups.

However, the findings were reversed with the higher-IQ gifted groups. That is, the higher IQ group was lower in self- and teacher-motivation than the lower-IQ comparison group. Taken together, the learning style preferences reported by the high-IQ gifted did not match the conventional classroom situation well, showing that some factors are needed for explaining the academic failure of many highly able students as a result of the conflict between their preferred learning styles and learning environment.

As for group (3), the gifted creative-thinking students preferred less structure and reported strong tactile and kinesthetic preferences.

As for group (4), the most remarkable finding of these eleven groups was that neither of learning style was the same. For instance, two groups (mathematics and foreign language) were more highly motivated than their nongifted counterparts, whereas four others were less motivated (computer, dance, music, and drama). Five of the eleven gifted groups were less motivated by their parents, whereas only the gifted students in foreign language were more parent-motivated. Besides, a majority of the groups showed strong preferences for tactile-oriented and kinesthetic-oriented learning, whereas those who were gifted in foreign language showed no significant

preferences for perceptual learning styles.

Milgram & Price’s study provides insight into the impact of learning styles on the interrelationship between learning styles and multiple intelligences. Their findings indicate that those gifted in foreign language were more highly motivated and parent- motivated than their nongifted counterparts. Nevertheless, those gifted in foreign language showed no significant preferences for perceptual learning styles.

2.3.2 Chang (1998)

Chang (1998) investigated the relationship between Taiwanese college students’

language learning styles and their EFL proficiency. The following nine hypotheses were testified:

1. The score of section I (listening) is lower than the score of section III (vocabulary and reading comprehension).

2. The score of section I (listening) is lower than the score of section II (structure and written expressions).

3. The scores of section II, III, and the total TOEFL scores of 18-yr students are significantly higher than those of 19-yr students.

4. The scores of each section and the total TOEFL scores of 18-yr students are significantly higher than those of 20-yr students.

5. The visual learning style is significantly correlated with the score of section II (structure and written expressions).

6. The global learning style is significantly correlated with the score of section I (listening).

7. The global learning style is significantly correlated with the score of section III (vocabulary and reading comprehension).

8. The global learning style is significantly correlated with the total score of

TOEFL.

9. The intuitive learning style is significantly correlated with the score of section I (listening).

10. The hands-on learning style is significantly correlated with the score of section I (listening).

11. The hands-on learning style is significantly correlated with the score of section II (structure and written expressions).

12. The hands-on learning style is significantly correlated with the total score of TOEFL.

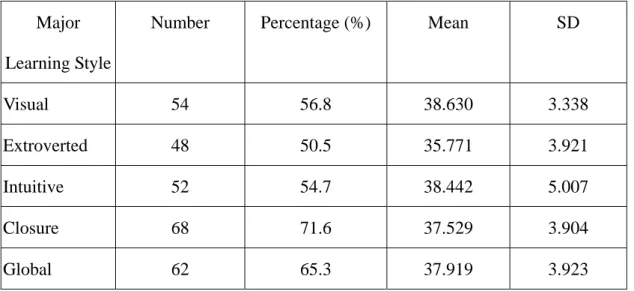

The subjects were 95 Taiwanese freshmen (18 males and 77 females) majoring in English. There were 51 students of 18 years, 26 students of 19 years, and 17 students of 20 years, with one unspecifiedg age. All the subjects took the TOEFL test and a questionnaire. TOEFL as the proficiency instrument was administered to assess the subjects’ performance on listening comprehension (section I), structure and written expressions (section II), and vocabulary and reading comprehension (section III). Style Analysis Survey (Oxford, 1993) was administered to examine the subjects’ perceptual learning styles (visual/auditory/hands-on), cognitive learning styles (intuitive/concrete; closure/openness; global/analytic), and affective (extroverted/introverted) learning styles.

The results of the SAS questionnaire are shown in Table 2-4:

Table 2-4 Taiwanese College Students’ Major Learning Style on SAS Major

Learning Style

Number Percentage (%) Mean SD

Visual 54 56.8 38.630 3.338

Extroverted 48 50.5 35.771 3.921

Intuitive 52 54.7 38.442 5.007

Closure 68 71.6 37.529 3.904

Global 62 65.3 37.919 3.923

For the perceptual learning style part, 56.8% of the subjects tended to use a visual learning style. For the affective learning style part, 50.5% of the subjects were found to be extroverted learners, which meant they “enjoyed a wide range of social, interactive learning tasks” (Oxford, 1995, p.213). With regard to the cognitive learning style part, 54.7% of the subjects were intuitive learners; 71.6%

were closure learners; 65.3% were global learners.

Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported in that the subjects’ score of section I (Mean=437) was lower than that of section II (Mean=488) and section III (Mean=448).

For Hypotheses 3 and 4, concerning the correlation between age and total TOEFL scores, a high correlation was found (p< .01). The 18-year-old students performed better than the 19-year-old ones in sections II, III, and total TOEFL scores, and they also scored higher in each section and the total TOEFL score than the 20-year-old ones. The hypotheses were supported.

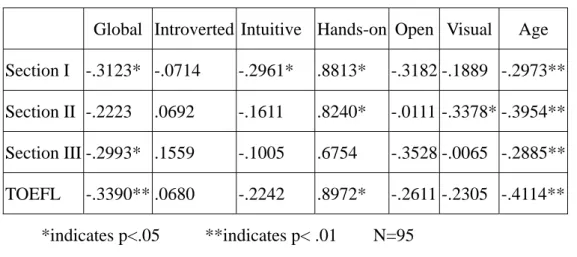

For Hypothesis 5, visual learning style was found to be correlated with the score of section II, structure and written expression (p<.05), as can be seen in Table 2-5:

Table 2-5 Pearson Coefficients between Taiwanese College Students’ Learning Style on SAS and their TOEFL Scores

Global Introverted Intuitive Hands-on Open Visual Age Section I -.3123* -.0714 -.2961* .8813* -.3182 -.1889 -.2973**

Section II -.2223 .0692 -.1611 .8240* -.0111 -.3378* -.3954**

Section III -.2993* .1559 -.1005 .6754 -.3528 -.0065 -.2885**

TOEFL -.3390** .0680 -.2242 .8972* -.2611 -.2305 -.4114**

*indicates p<.05 **indicates p< .01 N=95

For Hypotheses 6, 7 and 8, global learning style was found to be correlated with the scores of section I (listening) (p<.05), section III (vocabulary and reading comprehension) (p<.05), and the total TOEFL score (p<.01), as can be seen in Table 2-5. Therefore, the three hypotheses were supported.

For Hypothesis 9, Table 2-5 shows that a correlation was found between the intuitive learning style and the score of section I (listening) (p<.05).

For Hypotheses 10, 11, and 12, Table 2-5 shows that there was a significant correlation between the hands-on learning style and the score of section I, section II, and the total scores (p<.05). So, the three hypotheses were all supported.

In sum, the results of the study indicated a significant relationship between the subjects’ English proficiency and their learning styles. More specifically, their listening ability was correlated with global and hands-on learning styles; reading ability with the global learning styles; grammar ability with the visual and hands-on learning styles. Besides, their total TOEFL scores were correlated with their global and hands-on learning styles.

However, there are some problems with Chang’s study. First, questionnaires were the only data collection instrument used in her study, which is not sufficient to provide practical insights into the relationship between leaning styles and EFL English proficiency. In addition, the subjects’ English proficiency was determined by their TOEFL scores, which only measured receptive skills and might not reflect the students’ integrative English proficiency.

2.3.3 Tsao (2002)

Tsao (2002) explored the relationship between English academic achievement and learning styles/learning strategies at senior high school level. The subjects were 346 senior high school students of first and second year, 173 male and 173 female included. Her research questions20 were as follows: (a) What are the perceptual learning style preferences of Taiwanese senior high school students? (b) How do Taiwanese senior high school students’ language learning strategy use and their perceptual learning style preferences relate to their background variables, such as English achievement, gender, and grade level?

Two questionnaires, the PLSPQ (Reid, 1987), and the SILL21 (EFL/ESL 7.0 version, Oxford, 1989), were administered to examine the subjects’ perceptual learning styles and learning strategies. Besides, the subjects’ final course grades, determined by the average scores of the three monthly English exams, were collected to assess their English achievement.

With regard to the subject’ perceptual learning style preferences, the results

20 The other two questions were as follows: (i) How are English learning strategies used by Taiwanese senior high school students? (ii) How are perceptual learning style preferences related to English learning strategies?

21 The SILL( Strategy Inventory for Language Learning) developed by Oxford (1989) is a self-reporting survey that consists of 50 items classified into six strategy categories: (a) memory, (b) cognitive, (c) compensation, (d) metacognitive, (e) affective, and (f) social strategies.

showed that the subjects preferred auditory learning the most (M=3.20), followed by kinesthetic learning (M=3.10), group learning (M=3.09), tactile learning (M=2.94), visual learning (M=2.80), and individual learning (M=2.70). However, since the highest maximum for each style was five and the minimum was one, with 3.20 on a 5-point scale being the highest mean among the six learning styles, the result indicated that the subjects didn’t express strong preferences for any of the learning styles.

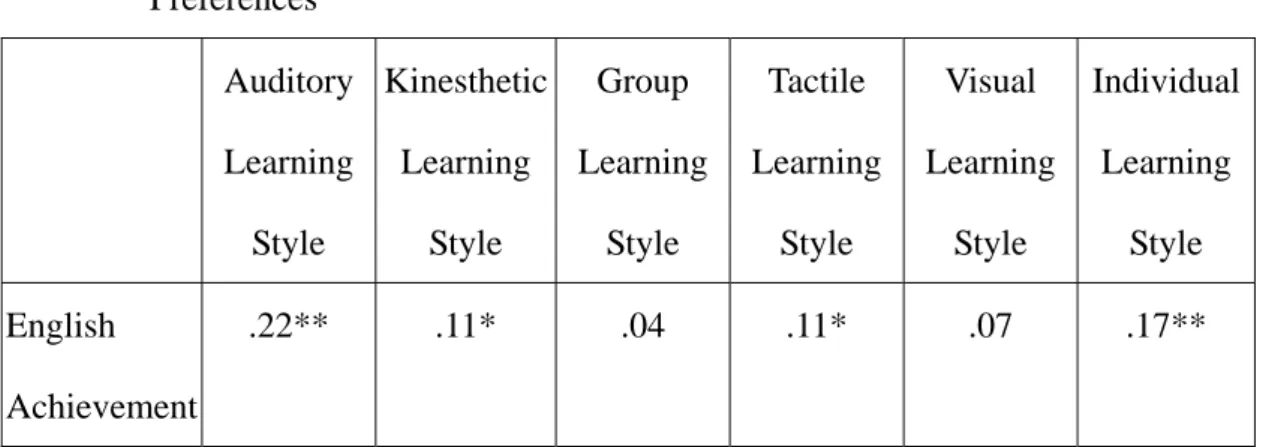

As for the connection between the subjects’ perceptual learning style preferences and English achievement, as Table 2-6 shows, the subjects’ English achievement was significantly correlated with their perceptual learning styles except for group and tactile learning. And the correlation between auditory learning style and English achievement was the highest (r=.22, p<.01), though it was not very high.

Table 2-6 shows the correlation between the subjects’ English achievement and learning style preferences:

Table 2-6 Correlation between the Subjects’ English Achievement and Learning Style Preferences

Auditory Learning

Style

Kinesthetic Learning

Style

Group Learning

Style

Tactile Learning

Style

Visual Learning

Style

Individual Learning

Style English

Achievement

.22** .11* .04 .11* .07 .17**

** Correlation is significant at the .01 level (2-tailed)

* Correlation is significant at the .05 level (2-tailed)

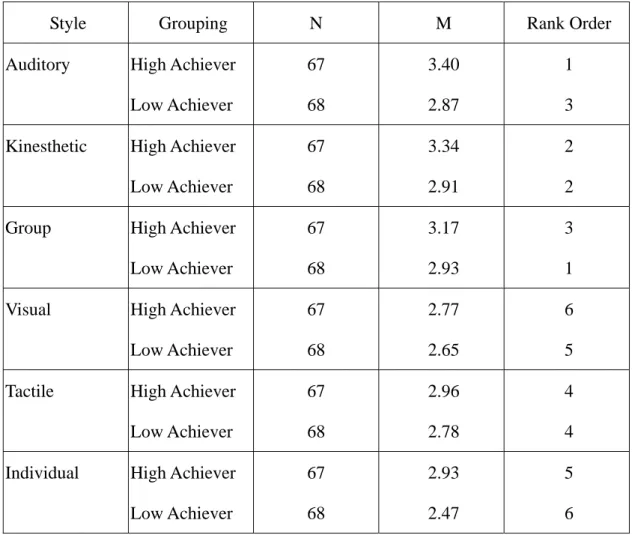

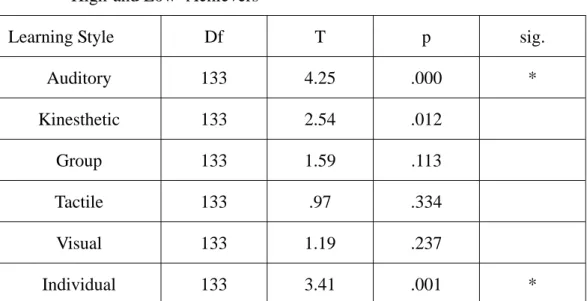

In addition, as shown in Table 2-7, the high achievers preferred auditory learning

the most while low achievers preferred group learning the most. Moreover, according to the t-tests results, there were significant differences only in preferences for auditory and individual learning styles between the high achievers and the low achievers, as can be seen in Table 2-8. That is to say, the high achievers showed a significantly stronger preference for auditory and individual learning styles.

Table 2-7 Learning Style Preferences between the High-and Low- Achievers

Style Grouping N M Rank Order

Auditory High Achiever

Low Achiever

67 68

3.40 2.87

1 3 Kinesthetic High Achiever

Low Achiever

67 68

3.34 2.91

2 2

Group High Achiever

Low Achiever

67 68

3.17 2.93

3 1

Visual High Achiever

Low Achiever

67 68

2.77 2.65

6 5

Tactile High Achiever

Low Achiever

67 68

2.96 2.78

4 4 Individual High Achiever

Low Achiever

67 68

2.93 2.47

5 6 Notes: 1. The maximum mean for each style is five.

2. Learning style is ranked in order of preference, for high-and low- achievers respectively.

Table 2-8 T-tests for Differences in Learning Style Preferences between the High-and Low- Achievers

Learning Style Df T p sig.

Auditory 133 4.25 .000 *

Kinesthetic 133 2.54 .012

Group 133 1.59 .113

Tactile 133 .97 .334

Visual 133 1.19 .237

Individual 133 3.41 .001 *

Note: Because a Bonferroni adjustment was made, the t-test was declared significant at .05 level when

it produced a t-value significant at .0037 level.

Generally speaking, the results showed that the subjects did not express very strong preference for any learning style, with auditory learning preferred the most and individual learning preferred the least. In addition, their English achievement was correlated with auditory, kinesthetic, visual, and individual learning styles.

Furthermore, the high achievers showed a significantly higher preference for auditory and individual learning styles.

Similar to the problems found in Chang (1998), Tsao used questionnaires as the only data collection instrument, qualitative surveys like interviews were excluded.

Besides, the subjects’ English achievement was determined by their final course grades instead of a standardized test, which lacked in reliability and validity as a measure of language proficiency.

2.4 Summary of Chapter Two

In this chapter, the researcher has reviewed some related studies of learning styles, multiple intelligences, and the relationship between EFL English proficiency and learning styles /multiple intelligences.

Milgram & Price (1993) explored the relationship between learning styles and multiple intelligences. The results indicated that the gifted in foreign language were more parent-motivated than their nongifted counterparts. Besides, those gifted in foreign language showed no significant preferences for perceptual learning styles.

Chang’s (1998) study investigated the relationship between learning styles and EFL English proficiency, with TOEFL scores as the index of students’ English proficiency. Her findings indicated that learning styles were correlated with the students’ English proficiency. The results also showed that listening ability was correlated with global and hands-on learning styles while reading ability was correlated with the global learning style.

Tsao (2002) examined the relationship between English academic achievement and learning styles/ strategies. On the whole, the results demonstrated a negligible correlation between the subjects’ English achievement and perceptual learning styles.

It was found that English achievement was correlated with auditory, kinesthetic, visual, and individual learning styles. Besides, significant differences between the high achievers and the low achievers were only found in response to auditory and individual learning styles.

All in all, due to that fact that most studies of the relationship between learning styles and EFL English proficiency covers only part of the English proficiency, studies of more integrated English proficiency are needed. On the other hand, owing to the paucity of empirical studies on the relationship between multiple intelligences and EFL English proficiency, an investigation into the relationship between multiple

intelligences and EFL English proficiency is particularly necessary. In the next chapter, the researcher will present the experimental design of the pres