行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

影響大學生英語外國口音因素之研究 研究成果報告(精簡版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型

計 畫 編 號 : NSC 95-2411-H-011-002-

執 行 期 間 : 95 年 08 月 01 日至 96 年 07 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立臺灣科技大學應用外語系

計 畫 主 持 人 : 鄧慧君

計畫參與人員: 大學生-兼任助理:柯維鴻、吳莉婷

報 告 附 件 : 出席國際會議研究心得報告及發表論文

處 理 方 式 : 本計畫涉及專利或其他智慧財產權,2 年後可公開查詢

中 華 民 國 96 年 08 月 30 日

關鍵詞:英語口語,外國口音,口語教學

本研究之目的為探討影響台灣大學生英語外國口音的因素,特別是與材料、

講者、及聽者相關之因素。主要的研究問題分別是:(1) 受測者唸高度留意及低 度留意口語材料的外國口音是否有顯著之差異?(2) 外國口音與說話者因素之 間是否有顯著的關係 (例如:年齡、性別、語言使用、重要性、相關性向)?(3) 有經驗及無經驗以英語為母語者所評比的外國口音是否有顯著之差異?(4) 外 國口音與理解程度是否有顯著的關係?本研究的受測對象為 120 位台灣的大學

生,所使用的口語材料一為高度留意的「句子朗讀」,包含五個特別編製的短句;

另一為低度留意的「段落朗讀」,包括篇長 111 字的英文故事。所採用的研究工

具為 17 題的問卷,用來評估影響外國腔調的說話者因素。在實驗程序方面,受 測者將於語言實驗教室進行個別錄音,在完成錄音工作後,請他們填寫問卷,以 了解影響講者外國口音之相關因素。

Keywords: EFL Speech, Foreign Accent, Speech Instruction

The purpose of the present study is to examine the factors which affect the

degree of foreign accent in the EFL speech of Taiwanese college students. Specifically, the study is designed to investigate the relationship between foreign accent and the factors associated with texts, speakers, and listeners. The major research questions include: (1) Is there any significant difference of subjects’foreign accents in their EFL speech materials with high monitoring and low monitoring? (2) Is there any

significant relationship between foreign accent and individual speaker variable (e.g., age, gender, language use, perceived importance, related aptitudes)? (3) Is there any significant difference in subjects’foreign accents rated by experienced and

inexperienced native speakers? (4) Is there any significant relationship between foreign accent and comprehensibility? In the study, subjects were 120 college students in Taiwan. Materials include “sentence reading”of high monitoring which is a list of

five specially prepared sentences, and “passage reading”of low monitoring which consists of a 111-word English story. The instrument adopted in the study was a questionnaire of 17 items designed to assess the speaker factors affecting foreign accent. As for experiment procedures, individual recording sessions were held in language labs. After finishing the recording task, subjects filled out the questionnaire of foreign accent factors. Finally, an interview was held with three subjects in each of the three universities to probe their perceptions of foreign accent in EFL speech.

Results of the study provide empirical descriptions on the foreign accents of Taiwanese EFL learners, and contribute to the understanding of the variables

influencing foreign accent. Results can also offer some implications for EFL speech instruction.

INTRODUCTION

Of all aspects of human language, pronunciation seems to be the most immediately observable. A listener usually does not need much time or linguistic sophistication to detect a foreign accent. As indicated by Nishi (2002), many second language (L2) learners wish to communicate as native speakers do. However, due to their foreign accent, L2 learners may be misunderstood. According to Thompson (1991), foreign accent is the pronunciation pattern that is perceived as being different from those of native speakers of the language. Those who learn a second language are often perceived to speak it with a foreign accent. A number of researchers have pointed out the features of foreign accent. For instance, degree of perceived foreign accent increases with the number and severity of segmental misarticulations (Major, 1987). Foreign accent may be influenced by divergences from L2 phonetic norms for implementation of stress and emphasis (Varonis & Gass, 1982). It may also be affected by divergences from L2 rhythmic and intonation patterns (Flege & Eefting, 1987). Besides, a relationship exists between perceived accent and ethnic group loyalty (Magid, 2004). Foreign accents are often associated with low intelligibility and negative personal evaluations of non-native speakers (Flege, 1987a).

Studies of L2 phonology have identified a number of factors that influence the

acquisition of a new sound system. These factors include exposure, gender, motivation, mimic ability, musical ability, modality preference, L2 speaking

proficiency, extraversion, careful versus spontaneous speech, and raters. With regard to most of the factors, no consistent findings and conclusions have been proposed. For example, there has been the widely held belief that a foreign accent in adults’speech stems from a loss of flexibility of the speech organs since a critical period exists for human speech learning. However, Flege (1987b) asserted that there is no conclusive empirical basis to support the critical period hypothesis because it does not take into account a variety of confounding factors. Thus, the present study aims to look into the complex links between these factors and the foreign accents in the EFL speech

produced by Taiwanese college students.

The purpose of the present study is to examine the factors which affect the degree of perceived foreign accent in the EFL speech of Taiwanese college students.

Specifically, the study is designed to investigate the relationships between foreign accent and the factors associated with texts, listeners, and speakers. The major

research questions explored in the study include: (1) Is there any significant difference of subjects’foreign accents in their EFL speech materials with high monitoring and low monitoring? (2) Is there any significant difference in subjects’foreign accents rated by experienced and inexperienced native speakers? (3) Is there any significant relationship between foreign accent and individual speaker variable (e.g., age, gender, language use, perceived importance, related aptitudes)? (4) What are EFL learners’

perceptions of foreign accent or accurate pronunciation?

LITERATURE REVIEW

For the past decades, there have been a number of studies conducted to examine the various factors on foreign accent with the aim to establish the predictors of pronunciation accuracy. Suter (1980) studied the correlations between English

pronunciation accuracy scores and a battery of 20 variables for 61 nonnative speakers of English. He found that only four variables are useful in accounting for the

variability. “First language”was the most important predictor to contribute

significantly to the explanation of the criterion’s variance, “aptitude for oral mimicry”

was the second most important factor, followed by “length of residency in an English speaking environment”, and the last was “strength of concern for pronunciation accuracy.”A study by Flege (1988) used interval scaling to assess degree of perceived

foreign accent in English sentences spoken by native and non-native talkers. Results show that native English listeners gave significantly higher pronunciation scores to native speakers of English than to Taiwanese adults who began learning English at an average age of 7.6 years. It was also found that the more experienced Taiwanese listeners differentiated native and non-native talkers to a significantly greater extent than a less experienced group, even though the subjects in both groups spoke English with equally strong foreign accents.

Moreover, Thompson’s study (1991) investigated factors associated with the acquisition of L2 pronunciation and methodological problems associated with the study of foreign accents. Results suggest that factors affecting the acquisition of L2 pronunciation depend on the type of primary exposure to L2, and that perception of a foreign accent depends on language samples presented for judgment and on the linguistic experience of listeners. In a study by Flege & Fletcher (1992), four

experiments were carried out to examine listener- and talker-related factors that may influence degree of perceived foreign accent. Findings reveal that the degree of accent is influenced by range effects. The larger the proportion of native speakers included in a set of sentences being evaluated, the more strongly accented listeners judged

sentences spoken by non-native speakers to be. Foreign accent ratings were not stable.

Listeners judged a set of non-native-produced sentences to be more strongly accented after they became familiar with those sentences. Results also show that adults’

pronunciation of an L2 may improve over time. Late L2 learners who had lived in U.S.

for an average of 14.3 years received significantly higher scores than late learners who had resided in U.S. for 0.7 years. Besides, Piske, MacKay, & Flege (2001) studied the factors related to the foreign accent of Italian-English bilinguals. They found that both age of L2 learning and amount of continued L1 use affected degree of foreign accent. On the other hand, gender, length of residence in a L2-speaking country and self-estimated L1 ability were not found to have a significant effect on overall L2 pronunciation accuracy.

In addition to these researches exploring the general factors on foreign accent, some studies have conducted to explore the effects of specific variables on

pronunciation accuracy. In regard to age of language acquisition, Tahta, Wood, &

Loewenthal (1981) examined predictors of transfer of accent from L1 to L2, in a group of people whose acquisition of English as an L2 had begun at ages ranging from 6 to 15+. The effect of age of L2 acquisition is very marked. Between 7 and 11,

accent transfer may be affected by factors other than biological maturation. The only such factor was whether L2 was used in the home, suggesting a shift of identification from L1 to L2 culture. Tahta, Wood, & Loewenthal (1981) conducted another study looking at the abilities of 5-15 year old monolingual English schoolchildren to replicate foreign pronunciation and intonation. They found that ability to replicate intonation declined fairly steadily over the whole age-range studied. By contrast, ability to replicate intonation remained steadily good until 8, and then dropped rapidly until 11.

In terms of language attitude, Brennan & Brennan (1981) examined the

relationship between degree of accent in the English of Mexican American speakers as assessed by naive raters, and the evaluative judgments of the raters toward accented speakers was explored. Findings indicated that the Accentedness Index was highly correlated with the status scale and that the assignment of status by raters was found to be a gradual rather than categorical phenomenon. In regard to text type, Munro &

Derwing (1994) investigated whether the utterances of L2 learners are likely to be perceived as more foreign accented when the speech material has been read or produced extemporaneously. An analysis of accentedness ratings from native English judges revealed no advantage for the speakers in the extemporaneous speaking condition. However, familiarity with particular non-native speech samples and speakers may lead to perceptions of greater foreign accentedness. Furthermore, Gass

& Varonis (1984) investigated the effect of various types of familiarity on native speaker comprehension of nonnative speaker speech. The assessed effects included familiarity with topic, familiarity with nonnative speech in general, familiarity with a nonnative accent in particular, and familiarity with a particular nonnative. It was found that while the most important variable was familiarity with topic, the other variables all had a facilitating effect on comprehension.

Since there is little empirical evidence regarding the role of pronunciation in determining intelligibility, Munro & Derwing (1995) conducted a study to examine the interrelationships among accentedness, perceived comprehensibility, and

intelligibility in the speech of L2 learners. It was suggested that although strength of foreign accent was correlated with perceived comprehensibility and intelligibility, a strong foreign accent did not necessarily reduce the comprehensibility or intelligibility of L2 speech.

Based on the literature reviewed above, very few studies have been found

directly related to the current study. Although Flege (1988) studied the foreign accent of adult native Taiwanese learners of English, the subjects were EFL learners residing in U.S.A. rather in Taiwan. Recently, there has been a number of research on English pronunciation of Taiwanese students, such as Chiou (1998) on English vowels, Cheng (2002) on intonation, Sun (2003) on rhythm, Chen (2003) on English liquids, and Chang (2003) on voiceless interdental fricative. However, these studies did not look into the perceived foreign accent of Taiwanese EFL learners, and most of their

subjects were high school students. Thus, it is the aim of the present study to fill in the gap for the research literature on foreign accent by examining the factors associated with texts, listeners, and speakers.

METHODOLOGY Subjects

The speech samples used in the present study were elicited from 120 college students in Taiwan. There were approximately equal numbers of male and female subjects. They came from two universities in northern and central Taiwan,

respectively. Among the 60 subjects in each of the two schools, 20 were

engineering/science majors, 20 were humanity/management majors, and the other 20 were English majors.

Materials

In the current study, the speakers were instructed to perform two tasks as follows.

One was “sentence reading”which included a list of five specially prepared sentences.

They were seeded with English sounds known to be difficult for Chinese students to pronounce and have been adopted in the previous research which also aimed to examine the degree of foreign accent in English sentences (Flege, 1988; Thompson, 1991; Flege & Fletcher, 1992). These sentences could best be described as phonetic mine fields designed to elicit the most heavily monitored speech sample. The other was “passage reading”which consisted of a 111-word English story, the North Wind.

The text was a modified version of one appearing in The Principles of the

International Phonetic Association, and has been used by Gass & Varonis (1984) in

their study for investigating the comprehensibility of nonnative speech. The passage was intended to elicit a speech sample with less degree of monitoring.Instrument

To examine the speaker effects on perceived foreign accent, a questionnaire was designed based on the related variables which have been proposed in research

literature (Suter, 1976; Purcell & Suter, 1980; Thompson, 1991; Flege & Fletcher, 1992; Munro & Derwing, 1995). The questionnaire consisted of 17 items designed to assess the speaker factors affecting foreign accent. There are mainly four parts in the questionnaire, including Background Information (Item 1~5), Percent of English Use (Item 6~10), Importance of English (Item 11~13), and Related Aptitude (Item 14~17), and the information of each item and its abbreviation was shown below:

1. The subject’s sex (Sex) 2. The subject’s major (MAJ)

3. The subject’s native language (L1) 4. The subject’s present age (Age)

5. Age at which the subject started learning English (AOL)

6. Number of months the subject has stayed in English speaking countries (MESC) 7. Percent of time for the subject to use English at school (PES)

8. Percent of time for the subject to use English at home (PEH) 9. Percent of time for the subject to use English with friends (PEF)

10. Percent of the subject’s teachers who were native speakers of English (PTNS) 11. The subject’s perceived importance of English for work (IEW)

12. The subject’s perceived importance of English for school (IES) 13. The subject’s perceived importance of having a good accent (IGA) 14. The subject’s perceived level of EFL proficiency (EFL)

15. The subject’s perceived ability of oral mimicry (MIM) 16. The subject’s perceived level of musical ability (MUA) 17. The subject’s perceived degree of extroversion (EXT)

Procedures

Before the experiment begins, subjects were told in detail what they were required to do in the study. Individual recording sessions were held in a language lab with high fidelity of audio equipment. Subjects were instructed to read at their normal rate and volume and were allowed to look over the printed materials before reading them into the microphone. Only one attempt at recording wasw made. The

presentation order of the two speech materials, i.e., sentence list and story passage, were counterbalanced across speakers. After finishing the recording task, subjects filled out the questionnaires of foreign accent factors. Finally, an interview were held with three subjects in each of the two universities to probe their perceptions of foreign

accent in EFL speech.

Raters

For the past 40 years, most of the English textbooks in Taiwan have adopted the phonetic symbols from A Pronouncing Dictionary of American English by John Samuel Kenyon & Thomas Albert Knott who were known as K.K.. Therefore, in the current research, the rating criteria of foreign accent in EFL speech were mainly based on the pronunciation standards of American English. Two raters were included in the present study. The experienced rater was a native speaker of American English who majored in language related fields and has taught EFL in Taiwan for at least two years.

The inexperienced rater is a native speaker of American English. But he had little or no knowledge of foreign languages and has stayed in Taiwan for less than one year.

Scoring

Global foreign accent for each speech sample were calculated from ratings of both raters. They were asked to determine the degree of foreign accent by marking on a 9-point scale that ranges from 1 (no foreign accent) to 9 (very strong foreign accent), which has been employed in a study by Munro & Derwing (1995). Southwood &

Flege (1999) indicated that it is appropriate to use an equal-appearing interval (EAI) scale with 9-point (or 11-point) to rate L2 speech samples for degree of foreign accent.

Raters were instructed to listen only to pronunciation and to ignore any other mistakes or deviations. The stimuli were presented to each rater over earphones at

approximately 80 decibels. A practice session with two speech samples not included in the study followed. Then, raters listened to the speech samples in random order on four separate sessions. According to Thompson (1991), an interval of a week or more will make it more likely that raters will forget individual voices and the accent rating they have previously given them. As a result, the whole scoring task included eight sessions and take two months, with one session in each week. A typical session lasted about 75 to 90 minutes with a rest break halfway through it.

Data Analysis

In the study, data analysis involved three stages. First, Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were computed between the mean scores of accent rating and the independent measures in the questionnaire. Next, a 2×2 ANOVA were utilized with text type (sentence, passage) and rater group (experienced, inexperienced) as

independent–measure factors. Finally, subjects’answers to the interview were not analyzed statistically, but they were transcribed and included in the discussion section.

CONCLUSION

As indicated by Thompson (1991), there are a number of reasons for studying foreign accent. At the theoretical level, an understanding of accent retention contributes to the continuing debate over the viability of the Critical Period

Hypothesis as a physiological threshold beyond which mastery of a new phonological system is usually impossible. At the practical level, an improved understanding of factors influencing the acquisition of L2 phonology can guide curricular and

pedagogical decisions on teaching pronunciation and speech. McLendon (1999) also suggested that L2 teachers with the knowledge of foreign accent can help students become aware of how their speech is perceived by native speakers and thus better prepare them for productive experiences interacting with native speakers.

Considerable research literature has been found to explore the speaker and listener effects on the foreign accent in L2 speech. However, very few studies have been conducted to investigate the foreign accent of EFL students in Taiwan. Thus, by providing empirical descriptions on the foreign accents of Taiwanese EFL learners, the present study can contribute to the understanding of the relationship between foreign accent and speaker variables, and further offer implications for EFL speech instruction.

REFERENCES

Anderson-Hsieh, J., Johnson, R., & Koehler, K. (1992). The relationship between native speaker judgments of nonnative pronunciation and deviance in

segmentals, prosody, and syllable structure. Language Learning, 42, 529-555.

Anderson-Hsieh, J. & Koehler, K. (1999). The effect of foreign accent and speaking rate on native speaker comprehension, Language Learning, 38, 561-613 Brennan, E., & Brennan, J. (1981). Accent scaling and language attitudes: Reactions

to Mexican American English speech. Language and Speech, 24, 207-221.

Bresnahan, M.J., Ohashi, R., Nebashi, R., Liu, W. Y., & Shearman, S. M. (2002).

Attitudinal and affective response toward accented English. Language &

Communication, 22, 171-185.

Chang, H. (2003). Phonological variation of (th) among EFL learners in Taiwan.

Master Thesis, Providence University.

Chen, H. (2003). A study of Chinese students’

pronunciation problems in English

liquids. Master Thesis, National Taiwan Normal University.

Cheng, H. (2002). Acoustic properties of Taiwanese high school students’

English intonation. Master Thesis, National Kaohsiung Normal University.

Chiou, T. (1998). An acoustic study of English vowels produced by Chinese speakers.

Master Thesis, National Chung Cheng University.

Derwing, T. M., & Munro, M.J. (1997). Accent, intelligibility, and comprehensibility:

evidence from four L1s. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19, 1-16 Derwing, T. M., Munro, M. J., & Wiebe, G.. (1998). Evidence in favor of a broad

framework for pronunciation instruction. Language Learning, 48, 393-410.

Derwing, T. M., & Rossiter, M.J. (2002). ESL learners’perceptions of their pronunciation needs and strategies. System, 30, 155-166.

Flege, J. (1987a). The production and perception of speech sounds in a foreign language in Human Communication and Its Disorders (ed.) by H. Wintz, Northwood, NJ: Ablex. Vol. III,

Flege, J. (1987b). A critical period for learning to pronounce a foreign language?

Applied Linguistics, 8, 162-177.

Flege, J., & Eefting, W. (1987). Cross-language switching in stop consonant perception and production by Dutch speakers of English. Speech

Communication, 6, 185-202.

Flege, J. (1988). Factors affecting degree of perceived foreign accent in English sentences. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America, 84, 70-79.

Flege, J., & Fletcher, K. (1992). Talker and listener effects on degree of perceived foreign accent. Journal of the Acoustic Society of America, 91, 370-389.

Gass, S., & Varonis, E. (1984). The effect of familiarity on the comprehensibility of nonnative speech. Language Learning, 34, 65-89.

Magen, H.S. (1998). The perception of foreign-accented speech. Journal of Phonetics,

26, 381-400

Magid, M. (2004). The attitudes of Chinese people towards fluent Chinese second

language speakers of English. Doctoral Dissertation, Concordia University.

Major, R. (1987). English voiceless stop production by speakers of Brazilian Portuguese. Journal of Phonetics, 15, 197-202.

McLendon, M. E. (1999). Language attitudes and foreign accent: A study of Russians’

perceptions of non-native speakers. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Texas

at Austin.Munro, M., & Derwing, T. (1994). Evaluations of foreign accent in extemporaneous and read material. Language Testing, 11, 253-266.

Munro, M., & Derwing, T. (1995). Foreign accent, comprehensibility, and intelligibility in the speech of second language learners. Language Learning,

45, 73-97.

Munro, M., & Derwing, T. (2001). Modelling perceptions of the comprehensibility and accentedness of L2 speech: the role of speaking rate. Studies in Second

Language Acquisition, 23, 451-468.

Nishi, K. (2002). Perceptual characteristics and intelligibility of Japanese-accented

English. Doctoral Dissertation, University of South Florida.

Piske, T., MacKay, I. R. A., & Flege, J. E. (2001). Factors affecting degree of foreign accent in an L2: A review. Journal of Phonetics, 29, 191-215.

Purcell, E., & Suter, R. (1980). Predictors of pronunciation accuracy: A reexamination.

Language Learning, 30, 271-287.

Scovel, T. (1969). Foreign accents, language acquisition, and cerebral dominance.

Language Learning, 19, 245-252.

Southwood, M. H., & Flege, J. E. (1999). Scaling foreign accent: Direct magnitude

estimation versus interval scaling. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 13, 335-449.

Sun, K. (2003). The effects of teaching rhythm as a means of pronunciation

instruction in secondary EFL classes in Taiwan. Master Thesis, National Tsing

Hua University.Suter, R. (1976). Predictors of pronunciation accuracy in second language learning.

Language Learning, 26, 233-253.

Tahta, S., Wood, M., & Loewenthal, K. (1981). Foreign accents: Factors relating to transfer of accent from the first language to a second language. Language and

Speech, 24(3), 265-272.

Tahta, S., Wood, M., & Loewenthal, K. (1981). Age changes in the ability to replace foreign pronunciation and intonation. Language and Speech, 24(4), 363-372.

Thompson, I. (1991). Foreign accents revisited: The English pronunciation of Russian immigrants. Language Learning, 41, 177-204.

Varonis, E., & Gass, S. (1982). The comprehensibility of non-native speech. Studies of

Second Language Acquisition, 4, 114-136.

EVALUATION of RESULTS

The results of the present study are expected to have the following contributions:

(1) In the area of speech studies, to provide empirical descriptions on the foreign accents of Taiwanese EFL learners;

(2) In the area of second language acquisition (SLA) research, to investigate the relationship between foreign accent and various factors; and

(3) In the area of instructional implications, to help university students effectively improve their EFL speaking performance through the understanding of

pronunciation accuracy.

出席國際學術會議心得報告

計畫編號 NSC 95-2411-H-011-002

計畫名稱 影響大學生英語外國口音因素之研究

出國人員姓名 服務機關及職稱

鄧慧君

國立台灣科技大學教授

會議時間地點 2007 年 4 月 2 日至 4 日 美國夏威夷

會議名稱 2007 Conference of International Society for Language Studies 發表論文題目 A Study of Task Types for L2 Speaking Assessment

一、參加會議經過

本人於 2007 年 4 月 1 日搭乘華航班機前往夏威夷,4 月 2 日及 3 日兩天前往凱悅飯 店會議廰出席會議。4 月 4 日早上參加大會精心安排的參訪活動,參觀夏威夷當地頗富 盛名的 Kamehameha Schools, 了解該校教導夏威夷本地語言及文化之概況。中午回到會 場後,下午 2 點由本人口頭發表論文,並回答在場聽講者之提問。4 月 5 日搭機返台,6 日抵達台灣。

二、與會心得

此次能獲得國科會計畫補助,前往夏威夷參加國際學術會議,收穫頗多,除了能有機 會和與會各國學者交換研究心得,令外,藉由參訪當地學校,深感夏威夷政府對推動多 元文化之用心,頗值得台灣借鏡。

三、發表論文

A Study of Task Type for L2 Speaking Assessment

Teng, Huei-Chun

National Taiwan University of Science & Technology

The purpose of the present study is to investigate the effect of task type on the performance of EFL speaking tests for Taiwanese college students. The major research questions explored in the study include: (1) Will test takers perform differently on various task types of EFL speaking tests? (2) Are there any differences in the accuracy, complexity,and fluency oftesttakers’discoursein terms of different task types? (3) Whataretesttakers’perceptionstoward thethreespeaking tasks? Subjectsin thestudy were 30 students of English major at a university in Taiwan. The three task types adopted in the study consisted of answering questions, picture description, and presentation. The subjects were tested in a language-lab setting and responded on an audiotape. After completing the speaking test, subjects answered a questionnaire designed to elicit their affective reactions toward the three tasks. The tapes were scored independently by two English teachers of native speaker. The taped protocols were also transcribed for the analysis of accuracy, complexity, and fluency. Results of the study can provide empirical evidences for the effects of L2 speaking assessment tasks. Results are also expected to offer some implications for designing EFL speaking tests.

Introduction

With the prevalence of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT), a considerable amount of the teaching and learning of a second language (L2) today is done orally. Consequently, developing speaking proficiency rates high among the objectives of most L2 programs. As pointed out by Shohamy, Reves, and Bejerano (1986), the earlier tests of oral proficiency can be termed

‘precommunicative’sincethe speaking tasksthe test-takers were required to perform were mostly mechanical repetition of words and sentences, the supplying of pattern answers to pattern questions, and substitution drills. However, these tests were viewed as unauthentic by language teachers and testers with the growing emphasis on CLT. As a result, direct tests of speaking proficiency have been developed by involving a test setting in which the examinee and one or more human interlocutors engage in communicative oral interactions. (Clark, 1975). Yet, according to Shohamy (1994) a number of variables in direct speaking tests tend to affect test-takers’scores,including the role relationship, personality and grades of testers and respondents, the purpose of the interaction, the topic, and the setting. Therefore, there is a need to control those variables by conducting oral tests in a more uniform way.

Semi-direct oral tests were developed to ensure reliability and validity without compromising the communicative features of oral tests. In these tests, test-takers respond to authentic recorded and visual tasks which require the production of discursive reactions. The oral tests are uniform tests because all test-takers perform similar language tasks. On the other hand, they involve a variety of communicative characteristics as they elicit a wide range of oral interactions and discourse strategies.

For the past decades, a great deal of attention has been devoted to the development of tests of oral language proficiency for use with foreign language learners. However, compared with paper and pencil testing, the field has been largely neglected. Due to the practicability of oral testing (Cohen, 1980). As a result, many problems remain to be examined, such as the subjectivity of the

rating process, the noninterval nature of the scales adopted for rating, the absence of high demonstrated validity across a variety of instruments and language abilities, and a paucity of testing methods beyond the oral interview (Henning, 1987).

The purpose of the present study is to investigate the effect of task type on the performance of EFL speaking test for Taiwanese college students. The major research questions explored in the study will be: (1) Will test takers perform differently on various task types of EFL speaking test? (2) Arethereany differencesin theaccuracy,complexity,and fluency oftesttakers’discoursein terms ofdifferenttask types? (3)Whataretesttakers’perceptionstoward thethreespeaking tasks?

A major goal of foreign language learning is to acquire oral facility in the target language.

Although a great deal of attention has been devoted to the assessment of L2 oral proficiency, scant efforts has been paid to developing valid and reliable oral testing methods (Robinson, 1992).

According to Skehan & Foster (1999), one area for language testing research seems very promising is to see whether task characteristics have interesting effects on the nature of speaking performance.

It is important to conduct research on task types, and to explore the predictability of the language characteristics associated with such tasks. In the last few years, only some studies have looked into the impact of task type on L2 speaking assessment. Among them, very few have dealt with the implementation of EFL speaking tests to Taiwanese students. Thus, by providing empirical evidences and descriptions of speaking assessment tasks, the present study will seek to contribute to our understanding of L2 speech performance, and further to offer implications for designing EFL speaking tests.

Literature Review

As indicated by Bachman & Palmer (1981), one of the areas of most persistent difficulty in language testing continues to be the measurement of oral proficiency. From the review of research literature, a number of studies have been conducted on the validation of oral tests. For example, Dandonoli & Henning (1990) examined the construct validity of the ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines and oral interview procedures. The results provided strong support for the use of the Guidelines as a foundation for the reliability and validity of the Oral Proficiency Interview (OPI). Stansfield &

Kenyon (1992) conducted a study to develop and validate a simulated oral proficiency interview (SOPI) as an alternative method to the face-to-face procedure employed by OPI. Moreover, Shohamy (1994) examined the validity of direct versus semi-direct oral tests. Results showed that concurrent validity of the two types of tests was high, yet the two tests still differed in a number of aspects,such astheelicitation tasksand thelanguagesamplesobtained.A study by O’Sullivan, Weir, & Saville (2002) addressed the relatively neglected area of validating the match between intended and actual test-taker language with respect to the language functions representing the construct of spoken language ability.

One of the main problems associated with oral tests is that they are subjective in nature and that there are no clear criteria for correctness. Some researchers on second language testing have looked into the issue of oral test rating. Shohamy (1983) examined inter-and intra-rater reliability of the oral interview test. She suggested that speaking tests such as the Oral Interview can be used reliably by decision-makers in spite of their subjective nature. Besides, Chalhoub-Deville’sstudy (1995) contended that researchers might need to reconsider employing generic component scales.

She recommended a research approach that derives scales empirically according to the given tests and audiences, and the purpose of assessment. Halleck (1995) also investigated the relationship between holistic and objective measures in the OPIs of 107 EFL students in China. Results indicated significant main effects for proficiency level and interview task, and provided some

support for the holistic rating system put forth in the ACTFL proficiency guidelines. Furthermore, Kenyon & Tschirner (2000) compared test reliabilities for the German Speaking Test, a semi-direct tape-mediated oral proficiency test, and the ACTFL OPI. Results revealed a high score equivalency between ACTFL proficiency ratingsobtained on both tests.In O’Loughlin’sstudy (2002),eight female and eight male test-takers undertook a practice IELTS interview on two different occasions, once with a female interviewer and once with a male interviewer. Results showed that gender did not have a significant impact on the IELTS interview.

In addition, several studies were found to be related to the purpose of the present research, i.e., to examinetheeffectsoftask typefororalassessment.First,in Henning’sstudy (1983)thethree oral testing methodologies of imitation, completion, and interview were compared for reliability and validity by employing an initial sample of 143 adult Egyptian EFL learners. He found that the pronunciation component of the imitation method exhibited highest overall validity across all indexes. Comparison of the three oral testing methods showed the ranking order in terms of available validity indexes, i.e., (1) imitation, (2) interview, and (3) completion. Carpenter, Fujii, &

Kataoka (1995) designed a new oral interview procedure for eliciting a representative sample of spontaneous Japanese language abilities from children aged 5-10. The test included six subtests and made use of realia, role playing, information gap activities and naturalistic conversation, all designed to comprise an oral interview. Results showed that the procedure elicits a language sample that is superior in quality and quantity to other existing Japanese oral test instruments for children.

Moreover, Foster & Skehan (1996) investigated the effects of planning time and three different tasks (personal information exchange, narrative, and decision-making) on the variables of fluency, complexity, and accuracy. Interactions were found between task types and planning conditions, such that planning had more influence on narrative and decision-making tasks than on personal information exchange task. Skehan & Foster (1999) also explored the effects of inherent task structure and processing load on the performance on a narrative retelling task. They suggested that more structured tasks generated more fluent language, and complexity of language was influenced by processing load. A study by Jeng et al (2000) used experimental design methods to compare three tasks of oral assessment. Results show that individual interviews took more time and effort, but were perceived to have higher value largely due to its interactive features between examinees and examiners. There were more problems with paired discourse and taped recording methods.

Besides, Wu, R. (2002) investigated the effects on task difficulty of performance conditions associated with the code complexity of written input in the read-aloud tasks of a semi-direct speaking test.

Finally, there are a number of studies which can provide useful information for the current research. Some studies have looked into the affective reactions to speaking tests (e.g., Scott, 1986;

Orr, 2002). Several researchers have analyzed the discourse in speaking test performance, such as Gelderen (1994),Douglas(1994),and O’Loughlin (1995).A few studieshavebeen conducted to examine the influence of planning time (e.g., Mehnert, 1998; Ortega, 1999). Teng (2002) and Wu, H.

(2002) have also studied the implementation of EFL speaking tests to Taiwanese students.

Method Subjects

Subjects in the current study were 30 students at a university in Taiwan. They studied at the Department of Applied Foreign Languages. They had approximately a high-intermediate level of EFL proficiency.

Instrumentation

The instruments used in the present study consisted of an EFL speaking test and an affective questionnaire. The test was a semi-direct speaking test with Chinese instructions printed in the test

booklet and recorded on the audiotape. There were three task types adopted in the speaking test, including answering questions, picture description, and presentation. In the first task, the test taker was required to respond to three questions recorded on the test tape, each question being heard once.

The test taker was given 30 seconds to answer each of the questions. In the second task, the test taker studied a picture accompanied by three guided questions written in Chinese. The test taker was given 30 seconds to look over the picture and questions, and the given 90 seconds to complete

a description of the picture. In the third task, the test taker read the statement printed on the test paper. The test taker was given 90 seconds to think about what he/she planned to say about the

statement, and then given 90 seconds to make a presentation on the statement.

The second instrument adopted in the study was an affective questionnaire, which was mainly based on Scott’s (1986) work. The questionnaire was designed to elicit test takers’ affective reactions toward the speaking test and the three assessment tasks, ie., answering questions, picture description, and presentation. The questionnaire included four parts and 35 questions in total.

Procedures

Before the experiment begins, subjects were be told in detail what they were required to do in the study. In order to counterbalance the practice effect of task type, the 30 subjects were randomly assigned to three groups with different presentation order of the three speaking tasks. Each of the three subject groups were tested in a language-lab setting and responded in an audiotape. It took about 10 minutes for the subjects to complete the speaking test. Then subjects answered the affect questionnaire.

Data Analysis

Two English teachers of native speakers, who are both trained raters, independently assessed each subject’sanswertapeand assigned ascorebased on Shohamy’s(1985)holisticrating scale for speaking test. The computed interrater reliability was 0.76. Besides, the present study adopted the analytic approach to analyze subjects’ performance data. The recorded speech samples were transcribed and coded to measure the accuracy, complexity, and fluency ofsubjects’performance. Accuracy was measured by calculating the number of error-free clauses as a percentage of the total number of clauses (Skehan & Foster, 1999). Complexity was indexed by dividing the number of clauses by the number of c-units (communication units). Accordning to Foster & Tonkyn (1997), c-unit is defined as a simple clause, or an independent subclausal unit, together with the subordinated clauses associated with them. Fluency was measured by dividing the number of syllables in a given speech sample by the time taken to produced them (measured in seconds) and multiplying the result by 60 (Mehnert, 1998). The statistical procedure, ANOVA, was conducted to test the hypotheses concerning the research questions.

Results

Subj e c t s ’ Pe r f or manc e s on Spe aki ng Tas ks

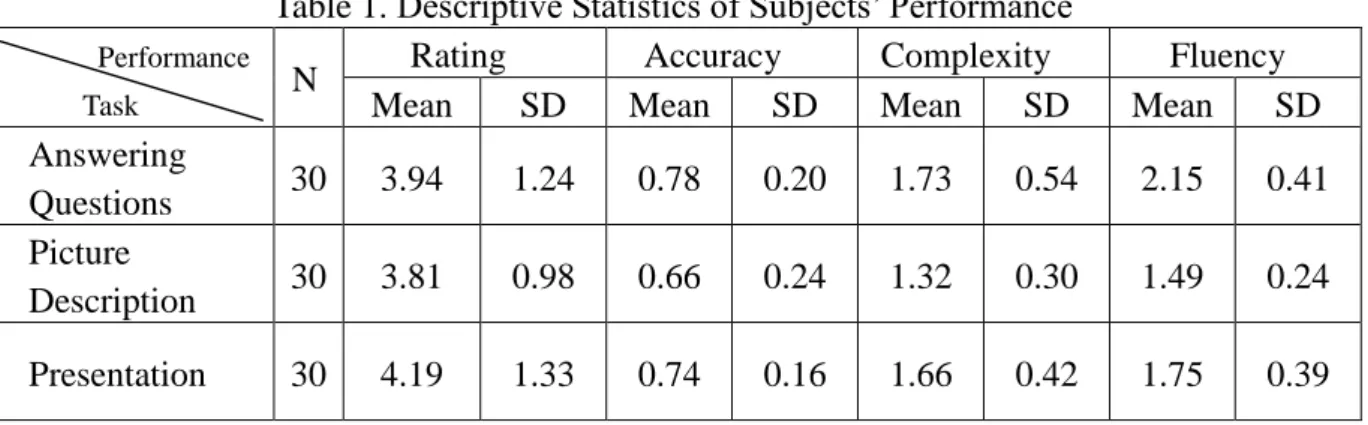

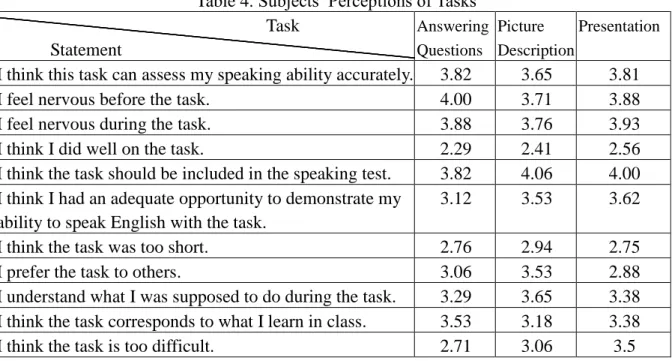

The main intent of the present study is to empirically investigate the effect of task type on the performances of EFL speaking tests for Taiwanese college students. Based on the research purpose, subjects’performanceswereanalyzed in termsofrating,accuracy,complexity,and fluency. Table 1 demonstratesthedescriptivestatisticsofsubjects’speaking testperformances.In termsofrating assessed by two raters on a 7-point scale, subjects got the highest average score (M = 4.19) for the

task of presentation, followed by answering questions (M = 3.94), and then picture description (M

= 3.81).Besides,threeanalyticscoring methodswereadopted to analyze subjects’performance. With regard to accuracy measured by calculating the number of error-free clauses as a percentage of the total number of clauses, subjects got the highest score (M = 0.78) for the task of answering questions, followed by presentation (M = 0.74) and then picture description (M = 0.66). As for complexity indexed by dividing the number of clauses by the number of c-units, subjects got the highest score (M = 1.73) for the task of answering questions, followed by presentation (M = 1.66) and then picture description (M = 1.32). In regard to fluency measured by dividing the number of syllables by the seconds to produce them, subjects got the highest score (M = 2.15) for answering questions, followed by presentation (M = 1.75) and then picture description (M = 1.49).

Table 1.DescriptiveStatisticsofSubjects’Performance

Rating Accuracy Complexity Fluency

Performance

Task N

Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD Mean SD

Answering

Questions 30 3.94 1.24 0.78 0.20 1.73 0.54 2.15 0.41

Picture

Description 30 3.81 0.98 0.66 0.24 1.32 0.30 1.49 0.24 Presentation 30 4.19 1.33 0.74 0.16 1.66 0.42 1.75 0.39

To determine iftherewereany significantdifferencesin subjects’speaking testperformance due to the effect of task type, a one-way ANOVA on the four dependent variables was conducted respectively. Results in Table 2 show that there are significant main effects for the two variables, i.e., complexity (F = 3.286, p = 0.023) and fluency (F = 14.140, p = 0.000).

Table 2.ANOVA ofSubjects’Performance

SV Variable SS df MS Error F p-value

Rating 1.167 2 0.583 63.812 0.411 0.665

Accuracy 0.118 2 0.014 1.795 1.481 0.238

Complexity 1.317 2 0.66 8.411 3.286* 0.023

Task

Fluency 3.551 2 1.776 5.650 14.140** 0.000

* p<0.05 ** p<0.01

With significant main effects for complexity and fluency, to further investigate the difference among the three task types of speaking test, post-hoctestswith Tukey’sprocedurewere conducted to make pairwise comparisons of group means. As shown in Table 3, subjects got significantly higher complexity scores for answering questions than for picture description (p = 0.028). As for the performance on fluency, subjects scored significantly higher for answering questions than for the other two task types (p = 0.000, p = 0.008).

Table 3.PostHocTestofSubjects’Performance

Performance Task Comparison Mean

Difference SE p-value Answering Questions vs. Picture Description 0.407* 0.153 0.028 Complexity

Answering Questions vs. Presentation 0.066 0.153 0.904