The moderating effect of co-workers’ reactions on

social ties and knowledge sharing in work teams

Chiung Hui Huang*

Department of Business Administration Cheng Shiu University, Taiwan Fax: +886–7–5254599

E-mail: graceh@cm.nsysu.edu.tw *Corresponding author

Ing Chung Huang

Department of Asia Pacific Industrial and Business Management National University of Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Fax: +886–7–5919029 E-mail: ichuang@nuk.edu.tw

Abstract: Researches have indicated that a close relationship among

colleagues (strong social ties) would increase contributors’ willingness to share knowledge. We argue that the contributors’ perception of their co-workers’ reactions would moderate the relationship between social ties and contributors’ willingness to share knowledge. The results of this article are consistent with previous researches that social ties enhance the contributors’ willingness to share knowledge in work teams. In addition, the co-workers’ reactions (attitude/capability) do influence the contributors’ willingness to share knowledge. The positive effect of social ties on contributors’ willingness to share knowledge would be increased when the contributors perceive that their co-workers’ learning attitude is earnest and would be reduced when the contributors perceive that their co-workers’ learning capability is strong.

Keywords: social ties; knowledge sharing; work team; social cognition;

interaction.

Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Huang, C.H. and

Huang, I.C. (2009) ‘The moderating effect of co-workers’ reactions on social ties and knowledge sharing in work teams’, Int. J. Learning and Intellectual

Capital, Vol. 6, Nos. 1/2, pp.156–169.

Biographical notes: Chiung Hui Huang is an Assistant Professor of the

Department of Business Administration at Cheng Shiu University in Taiwan. Her research interests include work teams, knowledge management, organisational change management and human resource management.

Ing Chung Huang is a Professor of the Department of Asia Pacific Industrial and Business Management at the National University of Kaohsiung in Taiwan. His research interests are in the areas of human resource management and organisational behaviour. His research focuses on the general topics of work motivation, job attitudes, job satisfaction and strategic human resource management.

1 Introduction

In today’s highly competitive environment, many companies employ work teams to achieve specific goals and improve performance. In addition, knowledge is important for an organisation to achieve or sustain competitive advantage (Lee and Choi, 2003; Boisot, 1998) and sharing knowledge is important to improve the effectiveness of group work (Storck, 2000). Therefore, the knowledge delivery among co-workers in work teams would be worthy to be explored because the co-workers should deeply cooperate with others and share individuals’ knowledge with others for solving problems in a high-speed changing environment.

Since organisational knowledge is the sum of individual knowledge within an organisation (Zhou and Fink, 2003), knowledge diffusion is important when an organisation manages its knowledge (Hall and Andriani, 2003; Okunoye and Karsten, 2002; Desouza, 2002; Lytras et al., 2002; Grover and Davenport, 2001). While many researches have paid attention to the processes for improving the effectiveness of knowledge diffusion, very few have focused on exploring the implementation of knowledge delivery from an interaction perspective between co-workers. Lytras et al. (2002) indicated that all the knowledge tasks can be viewed from the perspective of the knowledge providers or the knowledge users. Other studies focus on recognising and motivating senders to contribute their knowledge (Wasko and Faraj, 2005; Cabrera and Cabrera, 2005; Currie and Kerrin, 2004; Dyer and Nobeoka, 2000; Appleyard, 1996). However, if a recipient lacked motivation, absorptive capacity and retentive capacity, it could result in poor transfer of knowledge (Lytras et al., 2002). Therefore, it would be suitable that an organisation advances its knowledge delivery by exploring the interaction, cognition and attitude of both sides (knowledge providers and knowledge users).

From the interaction perspective between co-workers, knowledge delivery is not a static entity but the manifestation of a dynamic process of knowing by which human beings make sense of the world and reality (Kakihara and Sorensen, 2002). This article highlights the contributors’ perspective to investigate: Do social ties between co-workers encourage contributors to share their knowledge? Do contributors’ perceptions of co-workers’ reactions (attitude/capability) influence the contributors’ willingness to share their knowledge? Is there any interaction between social ties and contributors’ perception of co-workers’ reactions on contributors’ willingness to share knowledge?

2 Literature review and hypotheses

2.1 Social ties and knowledge sharing in work teams

Many organisations have concluded that effective knowledge sharing is the crucial way to lever their core competencies and gain competitive advantage (Lin and Lee, 2004). A major advantage of work teams is that teamwork has the capacity to empower people to utilise their abilities, which have relevance for motivation and group cohesiveness (Entrekin and Court, 2001). Many firms are realising the potential contributions of teams in enhancing continuous improvement of quality, innovation, customer satisfaction, improving employee satisfaction, reducing operating costs and improving the response to technological change (Chan et al., 2003). Lippitt (1982) also defined teamwork as the

way a group is able to solve its problems. In addition, groups whose members engage in sharing and learning can improve organisational performance and group work (Lesser and Storck, 2001; Storck, 2000).

The importance of knowledge sharing for collaborative work has already been established in past studies (Kotlarsky and Oshri, 2005). However, individuals would not lightly give their knowledge away if they recognised that knowledge is a form of personal property right (Hunter et al., 2002) or they thought that their knowledge is valuable and important (Bock and Kim, 2002).

Drawing on social cognitive theory, strong social identification would increase in-group perception and elicit cooperative activities in the workplace. Besides, social structures provide the fabric for tacit knowledge diffusion to others (Droege and Hoobler, 2003). In addition, individuals would share their knowledge and experience within in-groups instead of out-groups (Granitz and Ward, 2001). Reagans and McEvily (2003) also indicated that social cohesion affects the willingness and motivation of individuals to invest time, energy and effort in sharing knowledge with others.

The existence of a strong cooperative and collaborative culture is an important prerequisite for knowledge transfer between individuals and groups (Goh, 2002). Bock and Kim (2002) suggested that if employees believe they could improve relationships with other employees by offering their knowledge, they would develop a more positive attitude towards knowledge sharing. Researches proposed that a dense network can provide the opportunity for interaction, increasing the likelihood of knowledge transfer (Droege and Hoobler, 2003; Zack, 1999), and a lack of social interaction reduces knowledge exchange (Tsai and Ghoshal, 1998).

Knowledge sharing is a process that occurs between two persons: the knowledge contributor and the knowledge recipient (Kwok and Gao, 2005/2006). Although the relative advantages of strong ties and weak ties between contributor and recipient are considered debate, it is widely accepted that strong ties increase the likelihood that social actors will share sensitive information with each other, whereas weak ties provide access to a greater amount and diversity of information (Rindfleisch and Moorman, 2001). However, Hansen (1999) found that weak ties are not effective in transferring complex information. Besides, Uzzi and Lancaster (2003) proposed that there is a strong positive relationship between embedded ties and private knowledge transfer. Granovetter (1973; 1974; 1985) also indicated that strong ties refer to an intragroup of social interactions and offer social cohesion while weak ties refer to an intergroup of social interactions and offer new resources (Wu and Choi, 2004).

Consistent with these findings, we suggest that the strength of social ties between knowledge contributors and their co-workers enhances knowledge sharing. Stated formally:

H1 The strength of social ties has a positive effect on the willingness of contributors

to share knowledge in work teams.

2.2 Co-workers’ attitude/capability and knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing requires common understandings, attitudes and beliefs (Busco et al., 2005). It is found that experiential learning and employee interaction enhance tacit knowledge diffusion (Droege and Hoobler, 2003; Zack, 1999; Tsai and Ghoshal, 1998).

Besides, a colleague either through friendship or from working together appears to play an important role in the dissemination of learning (Collinson and Cook, 2004). Since knowledge sharing is an interaction process between contributor and recipient, co-workers’ learning attitude to diffused knowledge would be important for knowledge contributors in work teams. It could be inferred that a contributor would be willing to share his/her knowledge or experience if he/she perceived his/her co-workers were friendly, diligent or grateful for others’ help.

Moreover, knowledge may be freely available or accessible in the organisation but the recipient of that knowledge has to be able to use it (Szulanski, 1996). Kwok and Gao (2005/2006) also proposed that the success of final utilisation of shared knowledge in the context of the recipient is highly associated with the capability of the recipient, whether the recipient can absorb and master the shared knowledge. Besides, to trust in an individual’s ability would be to trust in their skills and competencies to do their job (Farrell et al., 2005). Lytras et al. (2002) also indicated that absorptive and retentive capacity needed to be considered in order to develop effective knowledge transfer. Based on the literatures, we could infer that employees would have a positive intention to share knowledge if they recognised their co-workers were competent or capable of learning new knowledge. In contrast, if employees perceived their co-workers’ capability was insufficient for learning diffused knowledge, contributors would probably reduce their willingness to share knowledge in work teams.

Summarising these findings and inferences, we suggest that co-workers’ learning attitude and/or learning capability are significant when contributors share their knowledge. Stated formally:

H2 Co-workers’ learning attitude has a positive effect on the willingness of

contributors to share knowledge in work teams.

H3 Co-workers’ learning capability has a positive effect on the willingness of

contributors to share knowledge in work teams.

2.3 Moderating effect of co-workers’ attitude/capability on social ties and knowledge sharing

Drawing on the communication perspective, the interaction and communication between co-workers would influence their attitude, behaviour and consequent interaction (Hackman, 1992; Salancik and Pfeffer, 1978). The exchange of knowledge-based resources is facilitated by social interaction, network ties and trust embedded in network relationships (Vainio, 2005). The findings indicate that learning is located not only in actors’ cognitions or past experiences, but also in relations among actors; and learning is viewed as a social process which helps solve problems encountered during the transformation of knowledge (Uzzi and Lancaster, 2003).

Based on the interaction and communication perspective, knowledge contributors’ perception of their co-workers’ reactions influence the contributors’ attitude or behaviour. Individuals are more likely to compare themselves with those they are closer to than with distant others (Ho and Levesque, 2005). As a result it would be inferred that the close co-workers who have a diligent learning attitude or competent learning capability would help strengthen contributors’ willingness to share knowledge. In

contrast, a contributor would be more reluctant to share knowledge with those who distantly work with him/her even if they have a diligent attitude or competent capability. Consequently, the co-workers’ learning attitude and/or learning capability would influence the relationship between social ties and contributors’ willingness to share knowledge. Stated formally:

H4 Co-workers’ learning attitude moderates the relationship between social ties and

contributors’ willingness to share knowledge.

H5 Co-workers’ learning capability moderates the relationship between social ties

and contributors’ willingness to share knowledge.

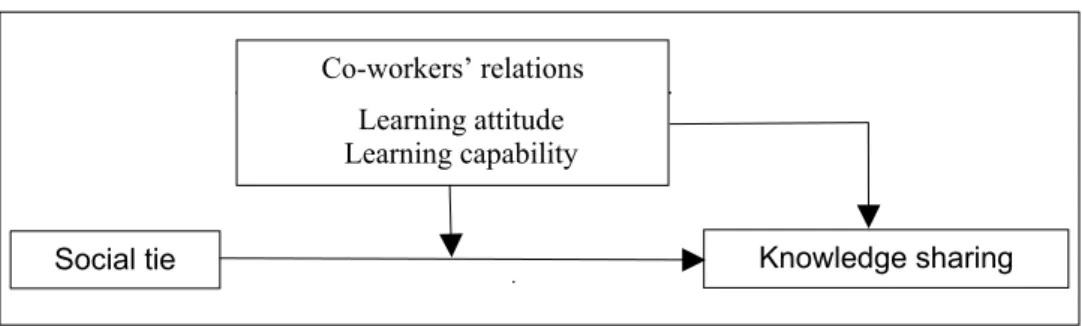

Summarising the literature review and the five hypotheses, a conceptual framework of the relationship between social ties, co-workers’ relations and contributors’ willingness to share knowledge is displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Conceptual framework of the study

Social tie Knowledge sharing

Co-workers’ relations Learning attitude Learning capability

3 Methods

3.1 Sample

The sample was collected from 158 participants in 28 work teams in south Taiwan. There were nine manufacturing and seven service firms in the sample. The manufacturing firms were composed of six electronic and three metallic manufacturing companies, and the service firms were three bank and four insurance companies. These work teams all perform new product development in their firms.

3.2 Dependent variable

The dependent variable, ‘Contributors’ willingness to share knowledge’, was measured by some modified questions from the questionnaire ‘Attitude toward knowledge sharing’ of Kwok and Gao (2005/2006) and by a five-point Likert-type scale. They included ‘I think that knowledge sharing is beneficial’, ‘My feelings towards knowledge sharing are favourable’, and ‘I like the idea of knowledge sharing’. A score of ‘5’ indicated that the respondents identified ‘very strongly agree’ and a score of ‘1’ indicated ‘very strongly

disagree’. The internal consistency reliability for the three items is high (Cronbach’s alpha is .81). In addition, the variable ‘Contributors’ willingness to share knowledge’ was calculated by the average of the three items.

3.3 Predictor variables

The independent variable, the strength of ‘social tie’, was measured using the Brown and Konrad (2001) questionnaire on Granovetter’s (1974) four dimensions. The four dimensions are ‘Frequency of contact’, ‘Emotional intensity’, ‘Intimacy’ and ‘Reciprocal services’. Some questions were modified to simplify the questionnaire. The respondents were asked to consider only the colleagues with whom they cooperate within a recent project. ‘Frequency of contact’ expresses how often a respondent talks to his/her co-workers. The response categories were as follows: 1 = less than once a day, 2 = once a day, 3 = several times a day but less than once an hour, 4 = once an hour, and 5 = more than once an hour. ‘Emotional intensity’ indicates how long a respondent has known his/her co-workers. The response categories were as follows: 1 = less than 1 year, 2 = 1–3 years, 3 = 3–5 years, 4 = 5–10 years, 5 = more than 10 years. Moreover, ‘Intimacy’ was measured by a five-interval scale to evaluate participants’ perception of whether he/she feels comfortable discussing with his/her co-workers. A score of ‘5’ indicated that the respondents feel ‘very comfortable’ and a score of ‘1’ indicated ‘very uncomfortable’. Finally, ‘Reciprocal services’ was measured by a five-interval scale to evaluate respondents’ expectation of a return from his/her co-workers. A score of ‘5’ indicated that the respondents ‘have no expectation for an immediate return’ and a score of ‘1’ indicated they ‘have expectations for an immediate return’. The internal consistency reliability for the four items is high (Cronbach’s alpha is .78). In addition, the variable ‘Social tie’ was calculated by the average of the four items.

‘Co-worker’s learning attitude’ was measured by a five-point Likert-type scale. The items are ‘My co-workers are willing to learn new knowledge’, ‘My co-workers are active to learn new knowledge’ and ‘My co-workers have a positive learning attitude when I share knowledge’. A score of ‘5’ indicated that the respondents identified ‘very strongly agree’ and a score of ‘1’ indicated ‘very strongly disagree’. The internal consistency reliability for the three items is high (Cronbach’s alpha is .85). In addition, the variable ‘Co-worker’s learning attitude’ was calculated by the average of the three items.

‘Co-worker’s learning capability’ was measured by some modified questions from the questionnaire of Kwok and Gao (2005/2006) and a five-point Likert-type scale. They were as follows: ‘My co-workers are able to recognise the value of knowledge I shared’, ‘My co-workers are able to assimilate the knowledge I shared and turn it into their own knowledge base’, and ‘My co-workers are able to apply the knowledge I shared to solve their problems’. A score of ‘5’ indicated that the respondents identified ‘very strongly agree’ and a score of ‘1’ indicated ‘very strongly disagree’. The internal consistency reliability for the three items is high (Cronbach’s alpha is .82). In addition, the variable ‘Co-worker’s learning capability’ was calculated by the average of the three items.

3.4 Control variables

We controlled some individual and team variables in order to purify the relationship between predictor variables and the dependent variable. The control variables were respondents’ gender, years of education and team size. ‘Gender’ included: 1 = male and 0 = female. ‘Years of education’ was measured by the formal years of education of the respondents. In addition, ‘Team size’ was calculated by the total number of employees in work teams.

3.5 Data analysis

The descriptive statistics and correlation are adopted to portray the distribution and correlation of/between variables. In addition, since the hierarchical multiple regression is the best method that deals with the interactions and multiplicative composite (Evans, 1991), we used hierarchical multiple regression to analyse the data. Besides, the test of multicollinearity indicated that the variance inflation factors for all predictor variables were between 1.03 and 1.15 (far less than the standard cut-off of 10), which indicates there is no evidence of collinearity between all predictor variables.

4 Results

Variable means, standard deviations and correlations are shown in Table 1. According to the results, there were 90 male and 68 female participants in the sample. The correlations between ‘Willingness to share knowledge’ and ‘Social tie’, ‘Co-worker’s learning attitude’, ‘Co-worker’s learning capability’ are significantly positive as predicted.

Table 1 Means, standard deviations and correlations

Variable Mean SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 Gender .57 .50 – 2 Years of education 13.51 1.79 –.173* – 3 Team size 10.92 9.37 –.106 –.181* – 4 Social tie 3.27 .59 –.105 –.243** .235** – 5 Co-worker’s attitude 3.44 .96 .160* .027 .018 .051 – 6 Co-worker’s capability 2.86 1.07 .006 .001 .052 .059 .137+ – 7 Sharing willingness 3.66 .92 –.059 –.091 .156* .623*** .364*** .267*** –

Notes: Two-tailed tests; +p < .1; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Table 2 reveals the hierarchical regression results (Equations 1–5). As predicted by H1,

social ties do have a positive and significant (p = .000) effect on the willingness of contributors to share knowledge (Equation 2). H1 is supported. In addition, co-worker’s

learning attitude and learning capability also have positive and significant (p = .000 and p = .096) effects on the willingness of contributors to share knowledge (Equation 3). Thus, H2 and H3 are also confirmed.

Moreover, there is interaction between social ties and co-worker’s learning attitude towards the willingness of contributors to share knowledge (p = .035) and the strength of interaction is positive. Besides, there is also interaction between social ties and co-worker’s learning capability on the willingness of contributors to share knowledge

(p = .007) but the strength of interaction is negative (Equation 5). H4 and H5 are

supported. Furthermore, the full model (Equation 5) explains 58% of the variance about the dependent variable (contributors’ willingness to share knowledge).

Table 2 OLS regression results

Sharing willingness

Variable Equation 1 Equation 2 Equation 3 Equation 4 Equation 5

Gender .003 .054 –.096 –.049 –.044

Years of education –.069 .096 –.104 .049 .032

Team size .119 .065 .087 .045 .028

Social tie .653*** .629*** .638*

Co-worker’s attitude (CA) .392*** .345*** –.378

Co-worker’s capability (CC) .135+ .111+ 1.011** Social tie × CA .910* Social tie × CC –1.064** Model F .965*** 22.78*** 6.349*** 27.052*** 23.403*** R2 = .022 .416 .201 .567 .605 Adjusted R2 = .001 .398 .170 .546 .580

Notes: Two-tailed tests; +p < .1; *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

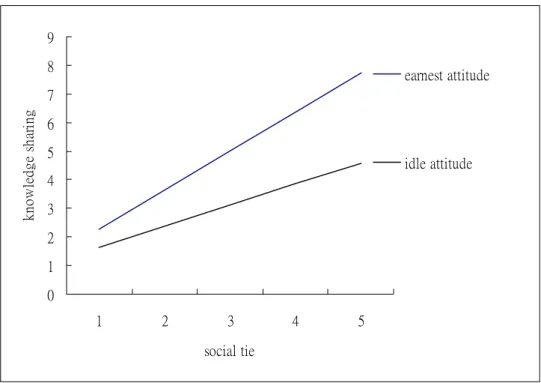

In addition, we inserted high and low values (as plus and minus one standard deviation from the mean) for co-workers’ reactions (learning attitude and learning capability) into Equation 5 to examine the specific nature of the interactions. The results indicate that the co-workers’ reactions moderate the relationship between social tie and sharing willingness.

Figure 2 Interaction: social tie and co-worker’s attitude (see online version for colours)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 1 2 3 4 5 social tie kn ow le dge s ha ri n g earnest attitude idle attitude

The positive effect of social ties on the willingness of contributors to share knowledge would increase when the contributors perceive that their co-workers’ learning attitude is high (Figure 2) and would decrease when the contributors perceive their co-workers’ learning capability is strong (Figure 3).

Figure 3 Interaction: social tie and co-worker’s capability

strong capability weak capability knowle dge sharing social tie 5 4 3 2 1 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 0

5 Conclusion and discussion

Although the social relationship has universally been recognised as having an important effect upon knowledge sharing, studies on the interaction between social relationship and co-workers’ attitude or capability to learn shared knowledge in work teams are relatively scarce. This article highlights the perspective of contributors to investigate the relationship between social tie, the reactions (attitude/capability) of contributors’ co-workers, and the contributors’ willingness to share knowledge. The results indicate that the strength of the social ties between co-workers and contributors’ perceptions of their co-workers’ learning attitude or learning capability have positive effects on contributors’ willingness to share knowledge. In addition, the effect of social ties on contributors’ willingness to share knowledge is moderated by the learning attitude or capability of the contributors’ co-workers. The positive relationship between the strength of social tie and contributors’ willingness to share knowledge would enlarge when the contributors perceive that their co-workers’ learning attitude is earnest and would reduce when the contributors perceive that their co-workers’ learning capability is strong.

5.1 Theoretical implications

Our findings extend the effects of co-workers’ interactions on the willingness to share knowledge. Three important findings can be addressed. Firstly, the finding that contributors’ perceptions of co-workers’ learning attitude and learning capability have positive and significant effects on the willingness of contributors to share knowledge is less addressed in other studies. From the viewpoint of communication, knowledge sharing is an interaction process between contributors and recipients. The reactions of both sides (knowledge contributors and recipients) would influence others’ perception, attitude and behaviour. In addition, since knowledge sharing is thought of as an extra role in an organisation (Kwok and Gao, 2005/2006), employees would not lightly share their knowledge. Consequently, if contributors perceived that recipients did not have a studious attitude or were incapable to learn the shared knowledge, the contributors would possibly decrease their enthusiasm to share knowledge. Therefore, the finding that the contributor would be willing to share knowledge when he/she perceives that co-workers have an earnest attitude or good absorptive capacity to learn new knowledge is reasonable and understandable.

Secondly, the finding that contributors perceiving a positive learning attitude from co-workers would enhance the positive relationship between the strength of social ties and contributors’ willingness to share knowledge is expected. Workers who are in strong social ties usually have positive identification from and affective support to others. In addition, individual cognition and behaviour are shaped by the attitudes and behaviours of others with whom one closely works (Edmondson, 2002) and individuals tend to perform social cognitive behaviour and avoid unexpected action (Stajkovic and Luthans, 2001). It is predictable that workers would be more willing to share if they recognised that their close colleagues (strong tie co-workers) are learning-active.

Thirdly, we are surprised about the finding that the positive relationship between the strength of social ties and contributors’ willingness to share knowledge would reduce when the contributors perceive their co-workers’ learning capability is strong. From the perspective of interaction, perceiving a positive learning capability of co-workers seems to increase the contributor’s intention to share knowledge. However, individuals recognise that knowledge is a form of personal property, so that a person will not lightly give it away. Therefore, if co-workers’ learning capability were too strong, the contributor would possibly think the competent co-worker as a threat to his/her job and decrease his/her willingness to share knowledge.

5.2 Managerial implications

The findings, that perceiving co-workers’ learning attitude/capability has a direct effect on knowledge sharing and a moderate effect on social tie-knowledge sharing, are meaningful for the management practice of knowledge sharing. First of all, according to the results, co-workers’ learning attitude directly and moderately encourages the contributors to share knowledge; learning culture is very important in work teams, not only to put pressure on recipients’ learning, but also to encourage contributors’ intention to share. Consequently, sharing and learning interact with each other in work teams and form a positive loop for work teams’ operation. In the management practice, managers

should encourage team members to learn and create a learning culture to simultaneously elicit contributors’ willingness to share knowledge and recipients’ willingness to learn the shared knowledge.

In addition, the results that co-workers’ learning capability has a positive direct effect on knowledge sharing and negative moderate effect on social tie-knowledge sharing, are particularly attention-getting. Competent team members are usually considered important and advantageous to teams’ operation. The absorptive capacity of team members was thought of as an influential factor to improve knowledge diffusion. Based on the result of this article, perceiving co-workers’ learning capability does directly increase contributors’ intention to share knowledge. However, perceiving capable co-workers simultaneously decreases the positive effect of social ties on contributors’ willingness to share. Consequently, competent team members are not absolutely good for knowledge dissemination in a team. The identification that knowledge is power probably increases team members’ alertness when they face competitive co-workers even though they work closely.

5.3 Limitations

The main variables, social ties, co-worker’s learning attitude, co-worker’s learning capability and contributors’ willingness to share knowledge, derived from the same survey, therefore the possibility of common method bias must be considered. However, we used a confirmatory factor analysis on all these variables’ items (Srivastava et al., 2006); the result indicated that these concepts were distinct from each other.

Another limitation of this article is that we did not include all possible factors which influence contributors’ willingness to share knowledge. Drawing on the perspective of interaction, we found some interesting results. However, many other variables would affect the contributors’ willingness to share knowledge, such as team components, the incentive implement of sharing, and individual difference between team members, so that we could not infer these variables’ influence on knowledge sharing.

This article highlights the perception of interaction between team members on knowledge sharing. The findings extended previous researches in knowledge management. Knowledge sharing does not depend only on contributors, but the results of interaction between contributors and recipients are also a key to knowledge sharing. The recipients’ reactions, learning attitude and learning capability influence contributors’ intention to share knowledge.

References

Appleyard, M.M. (1996) ‘How does knowledge flow? Interfirm patterns in the semiconductor industry’, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 17, pp.137–154.

Bock, G.W. and Kim, Y.G. (2002) ‘Breaking the myths of rewards: an exploratory study of attitudes about knowledge sharing’, Information Resources Management Journal, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp.14–21.

Boisot, M.H. (1998) Knowledge Assets: Securing Competitive Advantage in the Information

Economy, New York: Oxford University Press.

Brown, D.W. and Konrad, A.M. (2001) ‘Job-seeking in a turbulent economy: social networks and the importance of cross-industry ties to an industry change’, Human Relations, Vol. 54, No. 8, p.1015.

Busco, C., Frigo, M.L., Giovannoni, E., Riccaboni, A. and Scapens, R.W. (2005) ‘Beyond compliance: why integrated governance matters today’, Strategic Finance, Vol. 87, No. 2, pp.34–43.

Cabrera, E.F. and Cabrera, A. (2005) ‘Fostering knowledge sharing through people management practices’, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 16, No. 5, pp.720–735.

Chan, C.C.A., Pearson, C. and Entrekin, L. (2003) ‘Examining the effects of internal and external team learning on team performance’, Team Performance Management, Vol. 9, Nos. 7–8, pp.174–181.

Collinson, V. and Cook, T.F. (2004) ‘Learning to share, sharing to learn: fostering organisational learning through teachers’ dissemination of knowledge’, Journal of Educational

Administration, Vol. 42, No. 3, p.312.

Currie, G. and Kerrin, M. (2004) ‘The limits of a technological fix to knowledge management: epistemological, political and cultural issues in the case of intranet implementation’,

Management Learning, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp.9–29.

Desouza, K.C. (2002) ‘Knowledge management in hospitals: a process oriented view and staged look at managerial issues’, Int. J. Healthcare Technology & Management, Vol. 4, No. 6, p.478.

Droege, S.B. and Hoobler, J.M. (2003) ‘Employee turnover and tacit knowledge diffusion: a network perspective’, Journal of Managerial Issues, Vol. 15, No. 1, p.50.

Dyer, J.H. and Nobeoka, K. (2000) ‘Creating and managing a high-performance knowledge-sharing network: the Toyota case’, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp.345–367. Edmondson, A.C. (2002) ‘The local and variegated nature of learning in organizations: a

group-level perspective’, Organization Science, Vol. 13, No. 2, pp.128–147.

Entrekin, L. and Court, M. (2001) Human Resource Management: Adaptation and Change in an

Age of Globalization, Geneva: International Labor Office.

Evans, M.G. (1991) ‘The problem of analyzing multiplicative composites’, The American

Psychologist, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp.6–15.

Farrell, J.B., Flood, P.C., Curtain, S.M. and Hannigan, A. (2005) ‘CEO leadership, top team trust and the combination and exchange of information’, Irish Journal of Management, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp.22–40.

Goh, S.C. (2002) ‘Managing effective knowledge transfer: an integrative framework and some practice implications’, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp.23–30.

Granitz, N.A. and Ward, J.C. (2001) ‘Actual and perceived sharing of ethical reasoning and moral intent among in-group and out-group members’, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 33, No. 4, pp.299–322.

Granovetter, M. (1973) ‘The strength of weak ties’, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 78, No. 6, pp.1360–1380.

Granovetter, M. (1974) Getting a Job: A Study of Contacts and Careers, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Granovetter, M. (1985) ‘Economic action and social structure: the problem of embeddedness’,

American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 91, pp.481–510.

Grover, V. and Davenport, T. (2001) ‘General perspectives on knowledge management: fostering a research agenda’, Journal of Management Information Systems, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp.5–21. Hackman, J.R. (1992) ‘Group influences on individuals in organizations’, in M.D. Dunnette and

L.M. Hough (Eds.) Handbook of Industrial and Organizational Psychology, Inc., Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Hall, R. and Andriani, P. (2003) ‘Managing knowledge associated with innovation’, Journal of

Business Research, Vol. 56, No. 2, p.145.

Hansen, M.T. (1999) ‘The search-transfer problem: the role of weak ties in sharing knowledge across organizational subunits’, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 44, March, pp.82–111.

Ho, V.T. and Levesque, L.L. (2005) ‘With a little help from my friends (and substitutes): social referents and influence in psychological contract fulfillment’, Organization Science, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp.275–290.

Hunter, L., Beaumont, P. and Lee, M. (2002) ‘Knowledge management practice in Scottish law firms’, Human Resource Management Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp.4–21.

Kakihara, M. and Sorensen, C. (2002) ‘Exploring knowledge emergence: from chaos to organizational knowledge’, Journal of Global Information Technology Management, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp.48–66.

Kotlarsky, J. and Oshri, I. (2005) ‘Social ties, knowledge sharing and successful collaboration in globally distributed system development projects’, European Journal of Information Systems, Vol. 14, No. 1, p.37.

Kwok, S.H. and Gao, S. (2005/2006) ‘Attitude towards knowledge sharing behavior’, The Journal

of Computer Information Systems, Vol. 46, No. 2, pp.45–51.

Lee, H. and Choi, B. (2003) ‘Knowledge management enablers, processes, and organizational performance: an integrative view and empirical examination’, Journal of Management

Information Systems, Vol. 20, No. 1, p.179.

Lesser, E.L. and Storck, J. (2001) ‘Communities of practice and organizational performance’, IBM

Systems Journal, Vol. 40, No. 4, pp.831–841.

Lin, H.F. and Lee, G.G. (2004) ‘Perceptions of senior managers toward knowledge-sharing behavior’, Management Decision, Vol. 42, Nos. 1–2, p.108.

Lippitt, G.L. (1982) Organization Renewal: A Holistic Approach to Organization Development, 2nd ed., Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Lytras, M.D., Pouloudi, A. and Poulymenakou, A. (2002) ‘Knowledge management convergence – expanding learning frontiers’, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp.40–51. Okunoye, A. and Karsten, H. (2002) ‘Where the global needs the local: variation in enablers in the

knowledge management process’, Journal of Global Information Technology Management, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp.12–31.

Reagans, R. and McEvily, B. (2003) ‘Network structure and knowledge transfer: the effects of cohesion and range’, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 48, No. 2, p.240.

Rindfleisch, A. and Moorman, C. (2001) ‘The acquisition and utilization of information in new product alliances: a strength-of-ties perspective’, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 65, No. 2, pp.1–18.

Salancik, G. and Pfeffer, J. (1978) ‘A social information processing approach to job attitudes and task design’, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 23, pp.224–253.

Srivastava, A., Bartol, K.M. and Locke, E.A. (2006) ‘Empowering leadership in management teams: effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance’, Academy of Management

Journal, Vol. 49, No. 6, pp.1239–1251.

Stajkovic, A.D. and Luthans, F. (2001) ‘Differential effects of incentive motivators on work performance’, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 44, No. 3, pp.580–590.

Storck, J. (2000) ‘Knowledge diffusion through “strategic communities”’, Sloan Management

Review, Vol. 41, No. 2, pp.63–74.

Szulanski, G. (1996) ‘Exploring internal stickiness: impediments to the transfer of best practice within the firm’, Strategic Management, Vol. 17, pp.27–43.

Tsai, W. and Ghoshal, S. (1998) ‘Social capital and value creation: the role of intrafirm networks’,

Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 41, pp.464–477.

Uzzi, B. and Lancaster, R. (2003) ‘Relational embeddedness and learning: the case of bank loan managers and their clients’, Management Science, Vol. 49, No. 4, p.383.

Vainio, A.M. (2005) ‘Exchange and combination of knowledge-based resources in network relationships: a study of software firms in Finland’, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 39, Nos. 9–10, pp.1078–1096.

Wasko, M.M. and Faraj, S. (2005) ‘Why should I share? Examining social capital and knowledge contribution in electronic networks of practice’, MIS Quarterly, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp.35–57. Wu, W.P. and Choi, W.L. (2004) ‘Transaction cost, social capital and firms’ synergy creation in

Chinese business networks: an integrative approach’, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 21, No. 3, p.325.

Zack, M.H. (1999) ‘Managing codified knowledge’, Sloan Management Review, Vol. 40, pp.45–58.

Zhou, A.Z. and Fink, D. (2003) ‘The intellectual capital web: a systematic linking of intellectual capital and knowledge management’, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp.34–48.