Intergenerational relations and life

satisfaction among older women

in Taiwan

ijsw_81347..58Lin J-P, Chang T-F, Huang C-H. Intergenerational relations and life satisfaction among older women in Taiwan

Int J Soc Welfare 2011: 20: S47–S58 © 2011 The Author(s), International Journal of Social Welfare © 2011 Blackwell Publishing Ltd and the International Journal of Social Welfare.

This study examined the relationship between inter-generational relations and life satisfaction among older women (aged 55 years and older) in Taiwan. According to intergenerational solidarity theory, intergenerational relations are dictated by various components: living arrangements, intergenerational support exchange, intergenerational affection, and intergenerational norms. Data were obtained from the 2006 Taiwan Social Change Survey (N = 281). The main results show that intergenerational rela-tions have a significant effect on the life satisfaction of older women. Western studies have found that playing the giver’s role increases the life satisfaction of older people. However, the present study found that being mainly a recipient of support from adult children is related to a higher level of life satisfac-tion among older Taiwanese women. This study also underscores the importance of the emotional com-ponent in intergenerational relations to the well-being of older people. In Taiwan, stronger emotional bonds with adult children increases older women’s life satisfaction.

Ju-Ping Lin, Tse-Fan Chang, Chiu-Hua Huang

National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan

Key words: life satisfaction, intergenerational relations, intergenerational support, filial norms, older women, Taiwan

Ju-Ping Lin, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, National Taiwan Normal University, No. 162, Sec. 1, Heping E. Road, Da’an District, Taipei City 106, Taiwan

E-mail: t10016@ntnu.edu.tw

Accepted for publication April 17, 2011

Introduction

Although there is abundant research on life satisfaction among older people, analysis of how social contexts, economic structures, and social policies affect the level of such satisfaction is insufficient despite the impor-tance of these factors (George, 2006). In addition to economic and health factors, rel-evant family variations have also been found

to be of key importance for older people’s well-being (Mancini & Blieszner, 1989). The parent–child tie is a particularly strong source of social involvement and solidarity. Therefore, it seems reasonable to expect that intergenerational relations affect the well-being of elderly parents.

Taiwan is experiencing a rapid aging process. Traditional filial norms are often confronted with the impact of modernization,

Int J Soc Welfare 2011: 20: S47–S58 SOCIAL WELFARE

ISSN 1369-6866

resulting in structural changes in the family and in intergenerational interactions. Research focusing on intergenerational rela-tions is just emerging. The issue examined in the present study is how intergenerational relations with adult children influence life satisfaction for older Taiwanese women today. In particular, because intergenerational relations in actuality involve various aspects, this study explored intergenerational rela-tions by incorporating the essential dimen-sions proposed by the solidarity model (Bengtson & Schrader, 1982; Roberts, Richards, & Bengtson, 1991). By doing so, a more comprehensive picture of intergenera-tional relations in the Chinese society in Taiwan may be captured. It is expected that this study will extend knowledge in the area of intergenerational relations and give us insight into the overall effects of interge-nerational relations on life satisfaction of older people in a society undergoing rapid social change.

Background

In recent decades, Taiwan has experienced steadily declining fertility and increased longevity. As a result of the changing popu-lation structure, the dependency ratio of older people is expected to increase from 13.8 percent in 2006 to 30.3 percent in 2026 and to 67 percent in 2051. With a cultural heritage of strong filial piety, family is one of the major social pillars in Taiwan and remains a crucial source of support during old age (Lin, in press; Lin et al., 2003). The traditional Chinese family regards a three-generational household, or the co-residence of adult children with elderly parents, as the ideal realization of filial piety. Unlike in Western countries, most older people in Taiwan live with their adult children, although their percentage as part of the overall population has decreased in recent years (Tseng, Chang, & Chen, 2006). However, previous studies have also documented that children are less willing to co-reside with parents and would

rather provide financial support for parents’ living expenses while having their own nuclear family (Chang, 1994; Sun, 1991). The interplay of the dominant filial norms with the emerging nuclearization of both young and old generations is expected to produce complicated intergenerational rela-tions. This study thus examined intergenera-tional relations and explored their influence on the life satisfaction of older women.

Most previous studies that have examined how intergenerational relations with adult children influence life satisfaction for older people have focused mainly on one aspect – intergenerational support exchange with adult children. But the findings on the impact that receiving support has on the well-being of older people are mixed. Some have shown that the well-being of older people was improved (e.g. Antonucci & Jackson, 1990; Silverstein & Bengtson, 1994). Other studies found no effects of support on well-being (e.g., Umberson, 1992), and several studies found that support instead increased distress among older people (e.g., Lee, Netzer, & Coward, 1995). More recently, however, the study of elders as providers of support has attracted more attention, and a considerable body of research has examined the reciproc-ity in intergenerational support between older people and their adult children (Lowenstein, Katz, & Gur-Yaish, 2007). Hence, consider-ing the dual role of elderly parents, that is, both as receivers and providers of support, it seems imperative to conceptualize the types of intergenerational support in order to capture the diversity of such support. By doing so, we can clarify the relationship between the patterns of support exchange across generations and the well-being of older people.

In addition to the aforementioned con-cerns pertaining to support exchanges between generations, intergenerational rela-tions in actuality involve a number of aspects. To understand the complexity of intergenera-tional family relations in later life, Bengtson and Schrader (1982) proposed a model of

intergenerational family solidarity that focuses on family cohesion as an important component of family relations, particu-larly for successful adjustment to old age (Silverstein & Bengtson, 1994). This model emphasizes family solidarity as a multidi-mensional construct with six elements of solidarity: structural, associational, affec-tual, consensual, functional, and normative (Bengtson & Schrader, 1982; Roberts et al., 1991). Researchers have, in the past few decades, used this paradigm widely to study relations between parents and their adult children (e.g. Bengtson & Roberts, 1991; Even-Zohar & Sharlin, 2009; Schwarz et al., 2005; Silverstein, Gans, & Yang, 2006; Voorpostel & Blieszner, 2008; Waites, 2009; Yi & Lin, 2009). Adopting the framework suggested by the solidarity model, when studying the relationship between intergen-erational relations of elderly parents and adult children and parents’ life satisfaction, researchers should take various aspects of intergenerational relations into account. Intergenerational relations and older people’s life satisfaction

Since the 1940s, social gerontologists have conducted research into the relationship between frequency of intergenerational support and an older people’s life satisfac-tion, happiness, morale, and psychological well-being (Mancini & Blieszner, 1989). Many studies reported that frequency of contact between senior parents and their adult children had little impact on the parents’ psy-chological well-being (e.g., Brubaker, 1990; Lee & Ishii-Kuntz, 1987; Lowenstein et al., 2007; Suitor & Pillemer, 1987). Intergenera-tional relations are much more complicated than simply two generations keeping in touch with one another.

Antonucci and Jackson (1990) found that elderly parents enjoyed greater life satisfac-tion when they received more support from their children. Other studies have not sup-ported this finding, however. Several studies

(e.g. Lowenstein, 2007; Lowenstein et al., 2007) found that elderly parents who received assistance from their adult children were less satisfied with life. When elderly parents played the role of “giver,” their level of life satisfaction increased. From a social exchange viewpoint, Dowd (1975) com-mented that older people feel detached from society when they have fewer resources and fail to establish a reciprocal, balanced exchange relation. Lee (1985) expounded on this perspective, noting that an imbalanced exchange relation, which makes the older person feel dependent, has a negative effect on his or her psychological wellbeing. Researchers also found that compared with the need to be supported, the inability to establish a reciprocal relationship could more seriously devastate the older person’s morale (Liang, Krause, & Bennett, 2001; Stoller, 1985).

However, numerous reports have pointed out that patterns of intergenerational support are different between the West and the East. While adult children are likely to receive support from parents in the West (Lowenstein & Daatland, 2006), intergenerational ex-change within Chinese families is usually in the opposite direction (Lin & Yi, 2010). In Taiwan, adult children were found to give more money and assistance to elderly parents than they received from their parents (Chen, 2006; Lin, in press). In addition, gender can influence the provision of such support. Married sons generally provide more assis-tance to their parents than unmarried sons, and unmarried daughters assist their parents more than do married daughters (Lin et al., 2003). Chou (1996) found that the impact of receiving support on older Taiwanese women’s well-being differed depending on the source of the support. The more support (the sum of different types of support) their sons provided, the better psychological health the elderly parents enjoyed. On the other hand, studies in China concur that the posi-tive effects that providing functional support has on well-being are magnified among

parents who adhere to the more traditional norms regarding family support (Chen & Silverstein, 2000). Filial norms are of par-ticular importance in the East Asian region because of their historical and cultural heri-tage. Thus, intergenerational norms, which are influenced by society and culture, warrant further study. In Western society, older people value their independence highly. Even when they need assistance, if they think themselves to be unable to give something in return, they are hesitant to accept their chil-dren’s help. Thus, an imbalanced support exchange, in this context, has a negative effect on the older person’s psychological well-being. However, in Taiwan, under the influence of a culture of Confucian filial piety, supporting elderly parents is consid-ered a necessity to show reverence, and the family is the major source of financial stabil-ity for the older members.

In addition to the aforementioned con-cerns of support exchanges between genera-tions and the effects of filial norms, most of the research has failed to analyze the effects of affectual aspects on the older person’s life satisfaction. Mancini (1989) regarded the feeling of emotional intimacy between elderly parents and adult children to be an index to “intergenerational relation quality” because it was thought to help develop stronger ties among family members. In one study of farmer parents in Taiwan, Lin (2000) used qualitative data to analyze the affection that older persons have for their adult children. The affection of adult chil-dren, the consideration they show to their parents in daily life, and parents’ expecta-tions of care are all essential elements in intergenerational affection. Affection stems from attachment, caretaking, and expecta-tions. In contrast to Western cultures, in patri-archal Asian societies, roles and their fulfillment are more important than emotions and their effects for the formation of the intergenerational affection. The impact of intergenerational affection on the psycho-logical well-being of older people in Chinese

society is still unknown because less research has been carried out. Hence, this study ana-lyzed the potential influence of intergenera-tional affection ties with children on older persons’ life satisfaction.

In Taiwan, 77 percent of older women were found to rely financially on their adult children (Wang, 1997). Compared with men, who tend to play the more distant, authorita-tive role of traditional Chinese fathers, aging women have been shown to have a closer relationship with their adult children than aging men have (Baker, 1979; Cohen, 1976; Lin, 2000). Considering the special social and cultural situation of the older woman in Asian society in general, the focus of the present study was on older women in Taiwan. In brief, the study examined how intergenera-tional relations with adult children influenced life satisfaction for older Taiwanese women today. In particular, the study focused on four subdimensions of intergenerational rela-tions: living arrangements, intergenerational support type, intergenerational affection, and intergenerational norms. Based on the afore-mentioned literature review, we proposed that co-residence, receiving support, and strong emotional ties between older women and their adult children would increase older women’s life satisfaction. In addition, older women’s filial responsibility expectations toward adult children would be negatively associated with well-being because of con-flicts and disappointments that may occur if older parents’ expectations are not met. Method

Sample

Data were taken from the 2006 Taiwan Social Change Survey, phase five, wave two (Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan, 2006). The Family Module consists of an island-wide sample of 2,102 adults aged 20 years old and above who were ran-domly chosen using a multistage stratified sampling method and were interviewed.

Since the subject of this study was relations between elderly women and their adult chil-dren, only subjects aged 55 and above with at least one adult child (aged 19 and above) were included. After deleting subjects with no adult children, the final sample included 281 older female respondents. The average age of the older women in the sample was 66.52 years. The Taiwan Social Change Survey adopted the “focal child” strategy for measuring intergenerational relations between elderly women and their adult chil-dren, asking elderly women to choose the child she saw most frequently. Our selection strategy ensured that the focal child was the one with whom the parent had the maximum opportunity for interaction; thus, we have not underestimated the parent’s involvement with the children, because we did not ran-domly select against this child.

Measurements

Dependent variable.

The life satisfaction of the older women in this study was mea-sured by the question: “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?” The answers to this ques-tion were rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 to 5, in which a higher score indicates higher life satisfaction. The life satisfaction score for this sample aver-aged 3.75 out of a possible five points.Independent variables.

The firstinde-pendent variable was socio-demographic characteristics. Two dummy variables were used for marital status: married and unmar-ried. A total of 60.1 percent of the sample was married. Regarding family income, the respondents were asked, “How does your family income compare with that of aver-age households in our society?” The five response choices were: far below average,

below average, average, above average, and far above average. Self-reported health was

also measured on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from very bad (1) to very good

(5). The average score for self-reported health was 3.24 out of a possible 5 points. The number of children reported was the total number of living children. The older women in this study had an average of 3.84 surviv-ing children.

The second independent variable was intergenerational living arrangements. Living arrangement types were divided into two categories: co-residing or not co-residing with the focal child.

The third independent variable was

intergenerational affection. Intergenerational affection is the feeling of emotional intimacy between older women and their adult chil-dren. The respondents were asked to judge whether “you and your focal child are getting along at the moment.” The scores ranged from poor (1) to excellent (5).

The fourth independent variable was inter-generational norms. Based on the intergen-erational solidarity model, intergenintergen-erational norms were defined as the extent to which young and middle-aged family members are expected to assist their aging parents (Lee, Netzer, & Coward, 1994). In traditional Con-fucian culture, for adult children to provide financial support to their elderly parents is regarded as an act of filial piety. The present study defined intergenerational norms as the parent’s expectation for financial support from their adult children. The norm was mea-sured by a three-item scale a) that an unmar-ried adult man ought to provide financial support to his parents, b) that an unmarried adult woman ought to provide financial support to her parents, and c) that a married adult man ought to provide financial support to his parents. The items were administered in a Likert-type scale with seven options ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly

agree (7) so that high scores represent high

expectations pertaining to filial support. The fifth independent variable was inter-generational support. Three dimensions of support were distinguished: financial, emo-tional, and help with household chores. For each of these dimensions, support giving and

support receiving were measured separately. A six-item scale asked “How frequently did you do each of the following things for your focal child during the past 12 months?: (a) provided financial support, (b) took care of household chores, and (c) listened to the child’s ideas and shared your feelings.” The converse was: “How frequently did your (focal) child do each of the following things for you during the past 12 months?: (a) pro-vided financial support, (b) took care of household chores, and (c) listened to your ideas and shared your feelings.” The respon-dents rated each item on a five-point Likert-type scale corresponding to the following categories: not at all, seldom, sometimes,

often, and very frequently. The older women

who answered not at all or seldom were put in the “Give Less” category; the “Give More” group was composed of those who answered

sometimes, often, or very frequently.

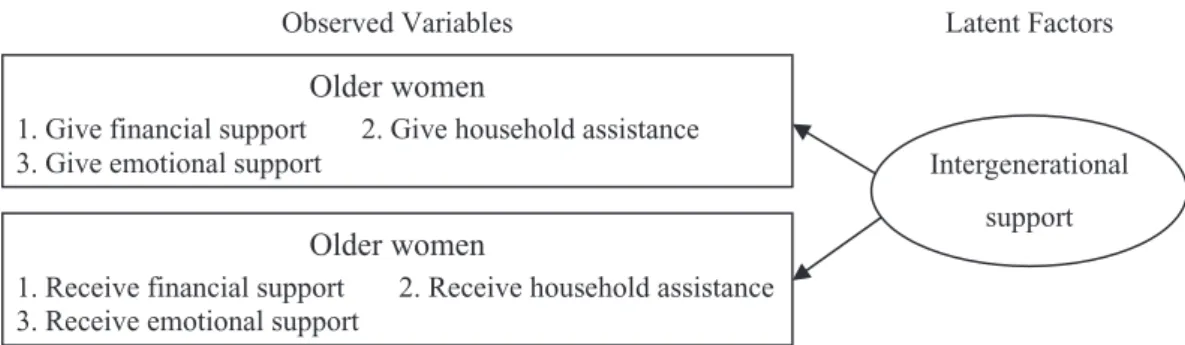

Regard-ing receivRegard-ing support from children, the same logic applied to this variable and resulted in the “Receive Less” and “Receive More” categories. Latent class analysis (LCA) was used to examine the underlying patterns of intergenerational support. As stated earlier, six indicators of intergenerational support were dichotomized to explore the latent structural pattern in intergenerational support (Figure 1). This study used the program Latent GOLD 3.0 (Statistical Innovations Inc, Belmont, MA) developed by Vermunt and Magidson (2003) to conduct the analysis.

Data analytic sequence

To examine how intergenerational relations influenced elderly women’s life satisfaction, we used the ordinary least squares regression analysis with life satisfaction as a dependent variable. In model 1, the socio-demographic variables of the elderly women were taken into account; in model 2, intergenerational relations variables were further added, such as intergenerational living arrangement, types of support, degree of intergenerational affection, and intergenerational norms. Results: intergenerational relations between the elderly women and their adult children

Living arrangement, intergenerational affection, and norms

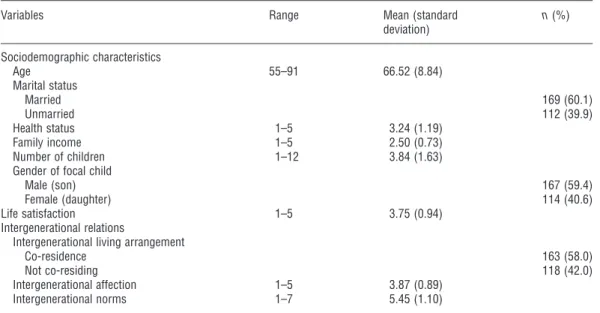

Table 1 shows that at the time of the study, over 58 percent of the older women were living with adult children. Regarding the intergenerational affection, our data demon-strate that there is a high degree of emotional ties between the older women and their chil-dren (mean= 3.87). On the other hand, in this study, intergenerational norms were defined as the parent’s expectation for financial support from adult children. The mean of the intergenerational norms scale exceeded 5 on a seven-point scale (mean = 5.45). This shows that there was a high expectation for

s r o t c a F t n e t a L s e l b a i r a V d e v r e s b O Older women

1. Receive financial support 2. Receive household assistance 3. Receive emotional support

Intergenerational support

Older women

1. Give financial support 2. Give household assistance 3. Give emotional support

financial support from adult children among the older women.

Intergenerational support types

We used the LCA to investigate the types of intergenerational support. The first step in this analysis is to determine the number of latent classes needed to characterize the data. As indicated in Table 2, the model dif-ferentiated the number of latent patterns as one, two, three, and four patterns. Condi-tional dependence diagnostics show that the assumption of local dependence holds for a four-type solution (L2 = 53.062, df = 36, p = 0.0332). The model that assumes four latent patterns represents the best fit for the

observed joint distribution among the six indicators of intergenerational support.

Table 3 displays the maximum likelihood estimates of the latent class proportions for the four-type model, and the conditional probabilities of item responses for each latent class for each of the six indicators of inter-generational support (probabilities greater than 0.6 are shown indicated with an aster-isk). The task of labeling the latent classes requires inspection of the conditional prob-abilities associated with the manifest indica-tors within each class. Using the pattern of these probabilities, we assigned the labels to describe the latent classes.

In type 1, the older women in the study were highly involved in exchanges with

Table 1. Description of analytic variables (N= 281).

Variables Range Mean (standard

deviation) n (%) Sociodemographic characteristics Age 55–91 66.52 (8.84) Marital status Married 169 (60.1) Unmarried 112 (39.9) Health status 1–5 3.24 (1.19) Family income 1–5 2.50 (0.73) Number of children 1–12 3.84 (1.63)

Gender of focal child

Male (son) 167 (59.4)

Female (daughter) 114 (40.6)

Life satisfaction 1–5 3.75 (0.94)

Intergenerational relations

Intergenerational living arrangement

Co-residence 163 (58.0)

Not co-residing 118 (42.0)

Intergenerational affection 1–5 3.87 (0.89)

Intergenerational norms 1–7 5.45 (1.10)

Table 2. Model fit for the optimal number of classes in the latent class analysis.

Number of types 1 2 3 4

L2(likelihood ratio statistic) 279.713 99.921 73.113 53.062

df 57 50 43 36

p value 0.0000 0.0000 0.0028 0.0332

Bayesian Information Criterion 2215.046 2080.133 2134.240 2153.879

their adult children, both giving and receiv-ing support on several dimensions. They

were labeled “high exchangers.” The

number of “high exchangers” was the highest: 37.7 percent of older women engaged in reciprocal financial, household, and emotional support relations with their adult children. Type 2 was associated with a high likelihood that the older women received support from adult children. These (23.5%) were labeled “receivers.” Type 3 was associated with a high likelihood that the older women give support to adult chil-dren but have a low likelihood of receiving support from adult children. These (5.0%) were labeled “givers.” Type 4 was associ-ated with a low probability of giving and receiving on each of the three dimensions of exchange. These (33.8%) were labeled “low exchangers.”

In summary, different types of intergen-erational support were found to take place between the older women and their adult chil-dren in Taiwan. The most common type was “high exchangers.” The next most common type was “low exchangers,” followed by “receivers.” A large number of studies in Taiwan have documented that aged parents receive instrumental and emotional support from their offspring (e.g. Chou, 1996; Lin et al., 2003). However, it is not true that older persons are primarily recipients of intergen-erational exchange. Nearly 5 percent of the older women in the study were “givers.” They

provided more financial assistance, help with household chores, and emotional support to their adult children than they received from their children.

Intergenerational relations and the life satisfaction of older women

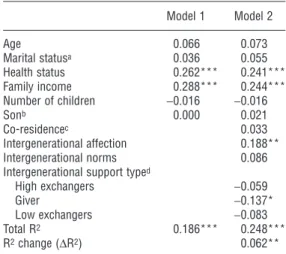

Table 4 presents standardized estimates pre-dicting life satisfaction of the older women. In the first equation, the socio-demographic variables of the women were taken into account (model 1). Model 1 shows that older women who enjoy good health (b = 0.262,

Table 3. Conditional probabilities of item responses for each latent class for indicator of intergenerational support

(N= 281).

Type Dimensions of support n (%) Label

Gives money Gives household assistance Gives emotional support Receives money Receives household assistance Receives emotional support 1 0.239 1.000a 0.884a 0.725a 0.746a 0.956a 106 (37.7) High exchangers 2 0.031 0.242 0.669a 0.705a 0.659a 1.000a 66 (23.5) Receiver 3 0.622a 0.692a 1.000a 0.000 0.000 0.449 14 (5.0) Giver 4 0.039 0.374 0.151 0.529 0.456 0.000 95 (33.8) Low exchangers a > 0.6

Table 4. Standardized ordinary least squares regression coefficients for the life satisfaction of older

women (N= 218). Model 1 Model 2 Age 0.066 0.073 Marital statusa 0.036 0.055 Health status 0.262*** 0.241*** Family income 0.288*** 0.244*** Number of children -0.016 -0.016 Sonb 0.000 0.021 Co-residencec 0.033 Intergenerational affection 0.188** Intergenerational norms 0.086

Intergenerational support typed

High exchangers -0.059

Giver -0.137*

Low exchangers -0.083

Total R2 0.186*** 0.248***

R2change (DR2) 0.062**

aUnmarried.bDaughter.cNon-co-residence.dReceiver. * p< 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

p < 0.001) and higher family incomes (b = 0.288, p< 0.001) are more satisfied with life. This finding supports relevant findings in the past – for older people, health is the most important factor contributing to a satisfying life, with income coming second (Kirby, Coleman, & Daley, 2004; Pinquart & Sörensen, 2000).

In model 2, we controlled for sociode-mographic variables. The model shows that intergenerational relations were significantly associated with the life satisfaction of elderly women (DR2= .062, p< 0.01). Intergenera-tional affection significantly predicted life satisfaction (b = 0.188, p< 0.01), and stronger emotional cohesion with adult children increased older women’s life satisfaction. The effect of intergenerational support types, in contrast to the “receivers,” is that the life satisfaction of older women was significantly lower (b = -0.137, p< 0.05) for those who were “givers.” In other words, older women who mainly provided support to their children were less satisfied. In addition, although the extended family model is culturally dominant in Taiwan, this study found no effect on life satisfaction stemming from co-residence with children (b = 0.033, ns (not significant)). Fur-thermore, the effect of older women’s beliefs about intergenerational norms on their life satisfaction was not significant (b = 0.086,

ns (not significant)). Discussion

Based on the intergenerational solidarity model and by analyzing intergenerational living arrangements, mutual support, expec-tation of filial norms, and intergenerational affection, we have examined how intergene-rational relations are related to life satisfac-tion for older women in Taiwan. This study found that older women do not merely rely on their adult children to provide financial or household chores support. Four types of older women were found in Taiwan: “high exchangers, “receivers,” “givers,” and “low exchangers.” The number of “high

exchangers” was the highest: 37.7 percent of the older women in Taiwan are highly involved in mutual support with their adult children. This is quite different from the research findings of Hogan, Eggebeen, and Clogg (1993) on American families. In that study, only 11 percent of the research subjects frequently exchanged support with their adult children, and nearly half of the American older people were “low exchangers.” In Taiwan, an Asian society, a relatively high proportion of older women retain a reciprocal support relationship with their adult children. Notably, 5 percent of the older women gave support to their adult children rather than received assistance. Mainland Chinese and Japanese scholars have discussed in recent years the dependence tendency of the younger generation. They speak of the Not in Employ-ment, Education, or Training group (NEET), meaning young people between 15 and 34 who are not in employment, education, or training, and “parasite singles,” referring to adult children who live with their parents after high school graduation and financially rely on them for living expenses (Yamada, 1999). Yieh, Tsai, and Kuo (2004) also found that in Taiwan, adult children who are young, have a low income, and are single are more likely to live with their parents after gradua-tion, relying on their parents to provide finan-cial support. This was found to occur more often with sons than with daughters.

What impact did the intergenerational relations between older women and their adult children in Taiwan have on the older person’s psychological well-being? Intergen-erational affection significantly predicted life satisfaction, and stronger emotional cohesion with adult children increased older women’s life satisfaction. Compared with the older women who mainly received support, those who mainly provided support to their chil-dren were less satisfied. By contrast, accord-ing to studies from the West, playaccord-ing the giver’s role was found to facilitate life satis-faction, while imbalanced intergenerational support had a negative influence on the older

person’s psychological wellbeing when this support was provided mainly by the adult child to the parent (Lowenstein, 2007; Lowenstein et al., 2007; Stoller, 1985). Such differences between the East and the West can be explained from a sociocultural per-spective. In American society, older people highly value independence. When they are in imbalanced exchange relations with their children, the inability to reciprocate means that the older person becomes dependent and feels powerless and is thus demoralized (Lee, 1985). In Asian settings, because traditional Chinese values highlight the importance of filial piety and of responsibility of adult chil-dren in taking care of parents in old age, most adult children support their older parents. What is more, family interactions in Asia are based on “the rule of demand” rather than “the equity rule” or “the equality rule” (Hwang, 1985, 1988). As the old saying goes, “storing crops for famine time and rearing children for senior days,” meaning that just as one stores up grain against lean years, parents bring up children for the purpose of being looked after in old age. The emphasis in Chinese communities on the “invest–return” dimension during a person’s lifespan has been shown to differ from the “symmetric reciprocity” rule of the intergenerational support mechanism of the West (Akiyama, Antonucci, & Campbell, 1990). Cultural values reinforce the meaning and expecta-tions of intergenerational support and shape the outcomes. In the present study, the more support older women in Taiwan received from their adult children, the more satisfied they were with life.

Previous researchers have generally assumed that in cultures where intergenera-tional ties are highly valued, co-residence with children has a positive influence on the psychological well-being of elders. However, this study found no such positive effect of co-residence with children on life satisfac-tion. Whether this finding reveals a social transition in Taiwan from multigenera-tional co-residence as a standard living

arrangement to a more Westernized family lifestyle, with heightened values of privacy and independence as well as of individuality, requires further investigation.

The use single-item measure-to-measure life satisfaction and intergenerational affec-tion as variables was a limitaaffec-tion in the present study. The findings and their inter-pretations should therefore be regarded with some caution. Despite these limitations, the contribution of this study is that it has examined intergenerational relations on older people’s life satisfaction in the context of multidimensional intergenerational solidarity (living arrangements and intergenerational support, affection, and norms). Additionally, the study employed LCA to examine the underlying patterns of intergenerational support. The research design of this study should help paint a clearer picture of the intergenerational relations between older people and their adult children. We suggest that future research utilizes the findings of the study as a basis for delving into the minds of adult children, discussing how the relations between the two generations influence adult children’s psychological well-being. Furthermore, the finding that the emotional component in intergenerational family relations is a crucial aspect of the subjective well-being of older people in Taiwan suggests that the emotional aspect of intergenerational relations is an important area for policy consideration.

References

Akiyama H, Antonucci TC, Campbell R (1990). Exchange and Reciprocity Among Two Gene-rations of Japanese and American Women. In: Sokolovsky J, ed. Cultural Context of Aging:

Worldwide Perspectives, pp. 127–138. Westfort,

CT, Greenwood Press.

Antonucci TC, Jackson JS (1990). The Role of Reciprocity in Social Support. In: Sarason BR, Sarason IG, Pierce GR, eds. Social Support: An

Interactional View, pp. 173–198. New York, John

Wiley and Sans.

Baker H (1979). Chinese Family and Kinship. New York, Columbia University Press.

Bengtson VL, Roberts REL (1991). Intergenera-tional Solidarity in Aging Families: An Example of Formal Theory Construction. Journal of

Mar-riage and the Family 53(4): 856–870.

Bengtson VL, Schrader SS (1982). Parent–Child Relations. In: Mangen DJ, Peterson WA, eds.

Research Instruments in Social Gerontology,

pp. 115–186. Minneapolis, MN, University of Minnesota Press.

Brubaker TH (1990). Families in Later Life: A Bur-geoning Research Area. Journal of Marriage and

the Family 52(4): 959–981.

Chang YH (1994). Family Studies in Taiwan: From the Household to Family Relations. Journal of

Community Development 68: 35–40. (In Chinese)

Chen C (2006). A Household-Based Convoy and the Reciprocity of Support Exchange between Adult Children and Noncoresiding Parents. Journal of

Family Issues 27(8): 1100–1136.

Chen X, Silverstein M (2000). Intergenerational Social Support and the Psychological Well-Being of Older Parents in China. Research on Aging 22(1): 43–65.

Chou YJ (1996). Social Support From Different Sources and Psychological Well-Being of the Elderly. In: Yang WS, Lee ML, eds. Population

Change, Health and Social Security, pp. 219–

246. Taipei, Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences, Academia Sinica. (In Chinese) Cohen ML (1976). House United, House Divided:

The Chinese Family in Taiwan. New York,

Columbia University Press.

Dowd JJ (1975). Aging as Exchange: A Preface to Theory. Journal of Gerontology 30(5): 584–594. Even-Zohar A, Sharlin S (2009). Grandchildhood: Adult Grandchildren’s Perception of Their Role Towards Their Grandparents From an Intergen-erational Perspective. Journal of Comparative

Family Studies 40(2): 167–185.

George KL (2006). Perceived Quality of Life. In: Binstock RH, George LK, eds. Handbook of

Aging and the Social Sciences, 6th edn, pp. 320–

336. New York, Academic Press.

Hogan DP, Eggebeen DJ, Clogg CC (1993). The Structure of Intergenerational Exchanges in American Families. American Journal of

Sociol-ogy 98(6): 1428–1458.

Hwang KK (1985). Face and Favor: The Chinese Power Games. American Journal of Sociology 92(4): 994–974.

Hwang KK (1988). Confucianism and East Asian

Modernization. Taipei, Liwen Publishing. (In

Chinese)

Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica, Taiwan (2006). Taiwan Social Change Survey, Phase Five, Wave Two, the Family Module. Available at http://www.ios.sinica.edu.tw/sc/en/home2.php [last accessed 10 March 2011].

Kirby SE, Coleman PG, Daley D (2004). Spirituality and Wellbeing in Frail and Non-Frail Older

Adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B 59(3): P123–P129.

Lee GR (1985). Kinship and Social Support of the Elderly: The Case of the United States. Ageing

and Society 5: 19–38.

Lee GR, Ishii-Kuntz M (1987). Social Interaction, Loneliness, and Emotional Well-Being Among the Elderly. Research on Aging 9(4): 459–482. Lee GR, Netzer JK, Coward RT (1994). Filial

Responsibility Expectations and Patterns of Intergenerational Assistance. Journal of

Mar-riage and the Family 56(3): 559–565.

Lee GR, Netzer JK, Coward RT (1995). Depression Among Older Parents: The Role of Intergenera-tional Exchange. Journal of Marriage and the

Family 57(3): 823–833.

Liang J, Krause NM, Bennett JM (2001). Social Exchange and Well-Being: Is Giving Better Than Receiving? Psychology and Aging 16(3): 511–523.

Lin JP (in press). The Change Trend of Intergenera-tional Relations in Taiwan. In: Chang YH, Chang LY, eds. Taiwan Social Change, Taipei, Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica. (In Chinese) Lin JP (2000). Intergenerational Solidarity Between

the Rural Elderly and Their Adult Children.

Journal of Taiwan Home Economics 29: 32–58.

(In Chinese)

Lin IF, Goldman N, Weinstein M, Lin YH, Gorrindo T, Seeman T (2003). Gender Differences in Adult Children’s Support of Their Parents in Taiwan.

Journal of Marriage and Family 65(1): 184–200.

Lin JP, Yi CC (2010). A Comparative Perspective on Intergenerational Relations in East Asia. Paper presented at the XVII ISA World Congress of Sociology, Gothenburg, Sweden, 11–17 July. Lowenstein A (2007). Solidarity–Conflict and

Ambivalence: Testing Two Conceptual Frame-works and Their Impact on Quality of Life for Older Family Members. Journals of Gerontology

Series B 62(2): S100–S107.

Lowenstein A, Daatland SO (2006). Filial Norms and Family Support in a Comparative Cross-National Context: Evidence From the OASIS Study. Ageing and Society 26(2): 203–223. Lowenstein A, Katz R, Gur-Yaish N (2007).

Reciprocity in Parent–Child Exchange and Life Satisfaction Among the Elderly: A Cross-National Perspective. Journal of Social Issues 63(4): 865–883.

Mancini JA (1989). Family Gerontology and the Study of Parent–Child Relationship. In: Mancini JA, ed. Aging Parents and Adult Children, pp. 3–13. Lexington, MA, Lexington Books. Mancini JA, Blieszner R (1989). Aging Parents and

Adult Children: Research Themes in Intergene-rational Relations. Journal of Marriage and the

Family 51(2): 275–290.

Pinquart M, Sörensen S (2000). Influences of Socioeconomic Status, Social Network, and

Competence on Subjective Well-Being in Later Life: A Meta-Analysis. Psychology and Aging 15(2): 187–224.

Roberts REL, Richards LN, Bengtson VL (1991). Intergenerational Solidarity in Families: Untan-gling the Ties That Bind. Marriage and Family

Review 16(1/2): 11–46.

Schwarz B, Trommsdorff G, Albert I, Mayer B (2005). Adult Parent–Child Relationships: Relationship Quality, Support, and Reciprocity.

Applied Psychology 54(3): 396–417.

Silverstein M, Bengtson VL (1994). Does Inter-generational Social Support Influence the Psychological Well-Being of Older Parents? The Contingencies of Declining Health and Widowhood. Social Science and Medicine 38(7): 943–957.

Silverstein M, Gans D, Yang FM (2006). Intergen-erational Support to Aging Parents: The Role of Norms and Needs. Journal of Family Issues 27(8): 1068–1084.

Stoller EP (1985). Exchange Pattern in the Informal Support Networks of the Elderly: The Impact of Reciprocity on Morale. Journal of Marriage and

the Family 47(2): 335–342.

Suitor JJ, Pillemer K (1987). The Presence of Adult Children: A Source of Stress for Elderly Couple’s Marriages. Journal of Marriage and the Family 49(4): 717–725.

Sun TH (1991). The Chinese Family in a Changing Society: The Cases of Taiwan. In: Chiao C, ed.

Chinese Family and Its Change, pp. 33–52. Hong

Kong, The Faculty of Social Science of the Chinese University of Hong Kong and the Hong

Kong Institute of Asia-Pacific Studies. (In Chinese)

Tseng LY, Chang CO, Chen SM (2006). An Analysis on the Living Arrangement Choices of the Elderly: A Discussion on Intergenerational Relationships. Journal of Housing Studies 15(2): 45–64. (In Chinese)

Umberson D (1992). Relationships between Adult Children and Their Parents: Psychological Consequences for Both Generations. Journal of

Marriage and the Family 54(3): 664–674.

Vermunt JK, Magidson J (2003). Latent GOLD 3.0

User’s Guide. Belmont, MA, Statistical

Innova-tions, Inc.

Voorpostel M, Blieszner R (2008). Intergenerational Solidarity and Support between Adult Siblings.

Journal of Marriage and Family 70(1): 157–167.

Waites C (2009). Building on Strengths: Intergenera-tional Practice With African American Families.

Social Work 54(3): 278–287.

Wang LR (1997). A Study on the Elderly Women’s Bio-Psycho-Social Adjustment. Research Report of National Science Council, Taipei, Taiwan. (NSC84-2411-H002-028) (In Chinese)

Yamada M (1999). The Age of Parasite Singles. Tokyo, Chikuma Shinsho. (In Japanese) Yi CC, Lin JP (2009). Types of Relations Between

Adult Children and Elderly Parents in Taiwan: Mechanisms Accounting for Various Relational Types. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 40(2): 305–324.

Yieh K, Tsai YF, Kuo CY (2004). An Exploratory Study of “Parasites” in Taiwan. Journal of Family