Two moralities: Reinterpreting the findings

of empirical research on moral reasoning in

Taiwan*

Kwang-Kuo Hwang

Department of Psychology, National Taiwan University, Taiwan

This paper reinterprets the findings of previous empirical research on moral reasoning and moral judgment conducted in Taiwan using Kohlberg’s research paradigm. It consists of three major parts. The first part explores Kohlberg’s theory of moral development and its limitations. Gibb’s (1979) two-phase model is used to emphasize the necessity of studying cultural heritage in understanding the prevalent moral reasoning of existential phase adults in a given society. The second part presents an analysis of Confucian ethics (Hwang, 1995), and proposes a conceptual scheme for discerning the significant features of Confucian ethics by referring to distinctions between positive/negative and imperfect/perfect duties. The discretionary features of Confucian ethics are further analyzed in terms of Shweder et al.’s (1990) scheme for discerning a rationally defensible moral code. In addition, the Confucian moral dilemma and its modern fate in the New-Culture Movement of the May Fourth period on mainland China, and the 1960s Gong De Movement in Taiwan are discussed. The third part of this paper reinterprets the findings of several empirical studies on moral reasoning in Taiwanese society. Special attention is paid to Cheng’s (1991) data from interviews with a group of college students using Kohlberg’s moral dilemma. The implication of her findings is discussed on the basis of the new conceptual scheme.

The goal of this paper is to reinterpret the findings of previous research on Chinese moral development that used Kohlberg’s paradigm by performing a careful analysis of the Confucian cultural tradition. The paper consists of three main parts. The first part discusses Kohlberg’s rationale for constructing his theory of moral development, its limitations, and Gibb’s (1979) revision of his theory. The second part presents an analysis of Confucian ethics and discusses its mandatory and discretionary features from the perspective of Western ethics. The third part reviews previous empirical research in Taiwan on Chinese moral reasoning. Throughout it is emphasized that an understanding of a particular culture is required for obtaining a comprehensive understanding of moral reasoning in that culture.

* This paper was written while the author was supported by a grant from National Science Council, Republic of China, NSC 87-2413-H-002-002. The author wishes to express his sincere gratitude to Dr Richard Shweder, William Gabrenya, H. K. Ma, and Olwen Bedford for their constructive comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Address correspondence to Kwang-Kuo Hwang, Dept. of Psychology, National Taiwan University, Taipei, 10764, Taiwan.

Kohlberg's theory and its limitations

Kohlberg's rationale

Kohlberg (1981, 1984) published two volumes of essays discussing the philosophy and psychology of moral development. In Chapter 2 of the first volume (Kohlberg, 1981, p. 30), he cited the Platonic view of the nature of virtue, which advocates that virtue is ultimately one not many. According to Plato, virtue always has the same ideal form regardless of climate or culture. This ideal form is called justice. Knowledge of ‘‘the good’’ is virtue, for one who knows the good chooses it. This kind of virtuous knowledge of the good is a philosophical knowledge or intuition of the ideal good, not simply opinion or conventional belief. People at different levels of moral development have differing knowledge of the good. Because many people know it poorly, the good needs to be taught. However, the teaching of virtue requires asking questions and demonstrating the correct way to behave, instead of simply giving rules. The goal of moral education is to enhance people’s inherent moral sense, not to teach them a body of specific moral rules or scripts.

Based on these assumptions, Kohlberg (1984) constructed his theory of moral development with reference to the logico-mathematical structures of Piaget’s (1972/1981) theory of cognitive development. Piaget proposed that the development of cognitive structure originates from interactions between the maturation of the organism and the structure of the environment in which a state of equilibrium between these two systems is sought. The transformation of cognitive structure from one stage to another may result in a reorientation in the organization of the individual’s modes of thinking. Cognitive stages are continuously differentiated and hierarchically integrated to form a sequential order. An individual’s development of moral reasoning and modes of thinking follows an invariant sequence. Cultural factors may facilitate or hinder the speed of development, but they cannot change the sequence. The principle of virtue appears in and unifies all stages of moral development, but only when one reaches the highest stage will one’s moral reasoning evidence the pure form of principled virtue.

In his book Essays on Moral Development, Kohlberg (1981) devoted all of Chapter 5 to illustrating the Western ideal of justice as reversibility. He cited Rawls’ (1971) veil of ignorance concept in laying out the conditions under which impartiality and fairness can be achieved. Rawls’ theory proposed that the principle of justice can be attained only among competing claims made by participants who are negotiating from a veil of ignorance. Under the veil of ignorance, participants know neither their positions in society, nor their places in the distribution of natural talents or abilities. Kohlberg adopted Kant’s maxim of the categorical imperative as the principle of justice: act so that the outcome of your conduct can be the universal will, or, act as you would want all human beings to act in a similar situation. A method of distribution that exemplifies this principle is the practice in which one person cuts the cake and a second person distributes it. Universal justice is the principle of the golden rule: ‘‘It’s right if it’s still right when you put yourself in the other place’’ (Kohlberg, 1981, pp. 196–197).

In short, Kohlberg considered reasoning in accordance with the principle of universal justice to be the final goal of moral judgment that accompanies the development of cognitive capacity at different stages of life. He used this principle as the criterion for evaluating an individual’s moral reasoning. For instance, moral reasoning at Stage 4 is characterized by a law-and-order or rule orientation. When an individual’s capacity for moral reasoning has developed to this stage, there is a tendency to believe that making judgments on the basis of law-and-order is just. It is impossible for an individual at an earlier stage of development to

make such a judgment. On the other hand, when an individual makes a law-and-order judgment, that person’s moral development should be classified as Stage 4 regardless of age. Based on this reasoning, Kohlberg (1971) made his famous claim for the cross-cultural universality of moral development:

All individuals in all cultures use the same 30 basic moral categories, concepts, or principles, and all individuals in all cultures go through the same order or sequence of gross stage development, though they vary in rate and terminal point of development. (Kohlberg, 1971, p. 175)

The claim of cultural universality has been examined by at least 45 studies in 27 cultural areas, including Western societies (e.g., England, Germany, New Zealand), non-Western societies that have been influenced by the West (e.g., India, Japan, Hong Kong, Taiwan), and tribal or village folk populations (e.g., Ladakh Indians, Kalskagamuit Eskimos, rural Kenyan Kipsigis) (Snarey, 1985). After a careful examination of the previous literature, Snarey (1985) indicated that because stage skipping and stage regressions were rare, the proposition of invariant sequence was well supported.

Snarey also found that although the progress from Stage 1 to Stage 3/4 or 4 was virtually universal, the presence of Stage 4/5 or 5 was extremely rare in all populations. Nearly all samples from urban populations or middle-class groups exhibited some Stage 6 principled reasoning, but no tribal or folk cultural groups showed any post-conventional reasoning which upheld social constructs, utility, individual rights, or universal ethical principles. Moreover, much of the moral reasoning data collected in collectivist or communalistic societies either could not be scored according to the standardized manual, or could not be explained in the context of Kohlberg’s theory. Examples of this problem have been reported from research in the Israeli Kibbutz (Snarey, 1982), Turkey (Nisan & Kohlberg, 1982), India (Vasudev, 1983), Papau New Guinea (Tietjen & Walker, 1984), Taiwan (Lei & Cheng, 1984; Cheng, 1991), Kenya (Edwards, 1986), and Hong Kong (Ma, 1997).

Mandatory and discretionary concepts

Kohlberg’s theory has been criticized as a case of scientific cultural bias (Simpson, 1974). Critics charge the theory treats the values of male, white, American intellectuals as the end point of moral maturation, and point out that the theory was formulated from the perspective of the Western ideology of rationalism, individualism, and liberalism (Shweder, 1982). Its ethical objectivism ignores moral judgments prevailing in many non-Western socio-cultural contexts, and fails to appreciate their substantial underlying ethical philosophies (Kurtines, Alvarez & Azmitia, 1990; Vine, 1986; Weinreich-Haste & Locke, 1983). Imposing Kohlberg’s scoring system on the moral reasoning of non-Western peoples may result in systematic bias leading to ethnocentrism.

Cultural psychologist Richard Shweder stressed that there are ‘‘divergent rationalities’’ in the moral domain, and that more than one rationally defensible moral code exists in the world (Shweder, Mahaptra & Miller, 1990). Every rationally defensible moral code is built from two kinds of concepts: some concepts are mandatory – without them, the code loses its moral appeal. Some concepts are discretionary – they can be replaced or substituted by alternative concepts without diminishing their rational appeal. If a moral code is divested of all discretionary concepts, it becomes empty and its rational appeal is diminished.

According to Shweder et al.’s analysis, there are three mandatory features in Kohlberg’s conceptions of post-conventional morality: (1) The ‘‘abstract idea of natural law’’ implies

that there are certain actions or practices that are inherently wrong no matter how much personal pleasure they might bring us, and despite the existence of positive rules or laws that might permit their occurrence. (2) The ‘‘abstract principle of harm’’ states that a legitimate ground for restricting a person’s liberty is the intention to do harm to someone else. (3) The ‘‘abstract principle of justice’’ states that like cases must be treated alike, and different cases should be treated differently.

These three principles are widely accepted by moral philosophers and are candidates for moral universals. In addition to these three, there are at least six discretionary features of Kohlberg’s theory that are not accepted by all rational thinkers. Substitute concepts or principles can replace these features to construct another moral code. These features include:

1. A right-based conception of natural law. Dworkin (1977) proposed that all moral codes

encompass personal rights, personal duties and social goals, but they may differ in the priority given to these three concepts. Kohlberg’s postconventional morality is premised on the conception of natural rights, rather than natural duties or goals.

2. A natural individualism in the abstract. This principle advocates voluntarism and the

individual over social roles or status.

3. A relative inclusive definition of a person or moral agent. This definition treats all

human beings as moral equivalents and excludes any other non-human living things. 4. Defining boundaries. The boundaries around the ‘‘territories of the self’’ are defined as

the realm worthy of protection.

5. A conception of justice as equality. This principle counts each individual as equal to one

unit, and treats every person’s claim as equal.

6. Secularism. Natural laws are defined as something which human beings can discover for

themselves without the assistance of revealed or handed down truths about right and wrong (Shweder et al., 1990, pp. 145–150).

The existential phase of development

Simpson (1974) complained that Kohlberg blurred the distinction between normative philosophy and empirical psychology by describing post-conventional thinking in terms of Western normative philosophy. This is an important point with which I agree. However, is it really possible to use empirical psychological methods to construct a theory of moral development applicable to all human beings without taking into account their respective normative philosophies? The answer to this question should be ‘‘No.’’ The content of moral reasoning is very likely to be influenced by the normative philosophy of a given culture, especially in the later stages of development.

As a collaborator of Kohlberg, Gibbs (1977, 1979) tried to revise Kohlberg’s theory in terms of Piaget’s phylogenetic perspective. According to Piaget, human intelligence is a holistic phenomenon encompassing social, moral, and logico-physical facts. Its development follows a standard sequence, just like that of other species. This sequence is termed the standard phase of development. Completion of physical maturation provides a foundation for the development of a second existential phase, which is unique to the human species.

Gibbs (1979) proposed four stages of the standard phase that correspond to Stages 1 through 4 in Kohlberg’s theory of moral development: (1) centerings, (2) exchanges, (3) mutualities, and (4) systems. The young child of Stage 1 tends to attend to a temporal state,

spatial segment, or conceptual aspect of a situation, with little relating of these states, segments, or aspects to one another. This tendency for centering causes young children’s thinking to be dominated by a consideration of superficial appearances. For example, a child may cite some salient physical features of an authority figure to justify that person’s moral superiority.

The process of attaining mid-childhood and Stage 2 enables the child to interrelate across spatio-temporal and conceptual aspects of situations. However, the child is still only able to reason on a first-order level, that is, the child makes inferences on the basis of empirical reality. For instance, the intangible values of a social relationship may be understood in terms of concrete considerations such as past or anticipated exchanges of favors and retaliations.

The singular achievement of intellectual development associated with early adolescence in Stage 3 enables one to think on a second-order level. Specifically, one may make inferences not only on the basis of empirical reality, but also on the propositions or values in effect furnished by the first-order thinking. Second-order thinking gives rise to a new way of problem-solving by hypothetico-deductive reasoning in logico-physical task situations. In the social realm, it enables one to remove oneself from one’s immediate interests in the ongoing exchanges of a two-person relationship, and to examine the mutuality of the relationship from the impartial perspective of a third person.

Along with the expansion of second-order thinking over the course of adolescent years, there is a progressive ability for a person at the highest stages of standard development to apply a detached meta-perspective to comprehend complex social systems as represented by modern society. Furthermore, people in this stage may reflect on the very conditions of their existence in the world. As a consequence of reflection upon one’s own existence, one may try to define a moral theory to justify one’s basic moral terms or principles ‘‘from a standpoint outside that of a member of society’’ (Kohlberg, 1973, p. 192). This potential for existential consideration represents the emergence of the second existential phase of development. Unlike the standard phase, no epigenetic change underlies existential development, therefore it follows no necessarily standard sequence.

People all over the world show a wide variety in their philosophies of morality, science, and life. Normative philosophies provide material for meta-ethical reflections or second-order thinking when an individual is trying to define moral theory. Therefore, in second-order to construct a unified theory of moral development for all human beings, it is necessary to incorporate the major normative philosophies found throughout the world into the theory. However, this objective is likely to be impossible. Eastern and Western philosophies are substantially different. It would be amazing if anyone could reconcile their diversity in order to build a synthetic theory of human moral development with any degree of integrity.

In view of this difficulty, Simpson (1974) suggested that a proper way for cross-cultural research on this topic to proceed would be to use ethnographic analysis to describe the patterns of behavior and reasoning that consistently emerge in the process of social interaction in one particular culture. In other words, a series of indigenous theories for interpreting moral reasoning could be constructed for existential phase adults in various cultures all over the world, rather than developing a unified theory of moral development for all humankind.

A few psychologists have made some efforts in this direction with respect to Chinese society. For instance, Lee (1973) and Yeh and Yang (1988) have proposed theories of cognitive development and filial piety, respectively; and Ma (1995, 1997) constructed a theory to describe the seven developmental stages of the cognitive and affective parameters

of Chinese altruism. However, these studies merely provide a starting point. They are a collection of theories addressing specific aspects of moral behavior, not an overall conceptual framework for examining how a young adult in Chinese culture performs meta-ethical reflections. In part two the foundation of such a framework is addressed.

Features of Confucian ethics

In the previous section I argued that the highest stage of moral development in Kohlberg’s theory incorporates an ideal morality of Christian civilization. Since God creates all humans equal, they should all follow a universal and reversible moral code that represents justice. In this section, I contrast these Western ideals with East Asian Confucian ethics in order to provide an appropriate framework for interpreting moral reasoning in Chinese society.

Confucian ethics for ordinary people

In my book Knowledge and Action (Hwang, 1995), I subdivided the ethical arrangements for interpersonal relationships proposed by the Confucian Way of Humanity into two categories: ethics for ordinary people, and ethics for scholars. The former category, which should be followed by everyone including scholars, is best described by the following propositions in The Golden Mean:

Benevolence is the characteristic attribute of a person. The first priority of its expression is showing affection to those closely related to us. Righteousness means appropriateness, respecting the superior is its most important rule. Loving others according to who they are and respecting superiors according to their ranks gives rise to the forms and distinctions of propriety (li) in social life. (Chapter 20)

These statements illustrate the crucial relationship among the concepts of benevolence, righteousness, and propriety (Hwang, 1995). Confucius advised that social interaction should begin with an assessment of the role relationship between oneself and others along two social dimensions: intimacy/distance and superiority/inferiority. Behavior that favors people with whom there is a close relationship can be termed benevolence (ren), respecting others for whom respect is required by the relationship is called righteousness (yi), and acting according to previously established rites or social norms is called propriety (li).

The concept of justice in human society is classified into two categories by Western social psychologists: procedural justice and distributive justice. Procedural justice refers to the types of procedures that should be used by members of a group to determine methods of resource distribution. Distributive justice is the particular method of distribution that is accepted by group members (Leventhal, 1976, 1980).

Confucian ethics for ordinary people can be interpreted in terms of Western justice theory. Confucius advocated that procedural justice in social interaction should follow the principle of respecting the superior. The role of the resource allocator should be played by the person who occupies the superior position. In choosing an appropriate method for resource distributive justice, the resource allocator should follow the principle of favoring the intimate. Furthermore, from the Confucian perspective, it is righteous to determine who has decision-making power by calling on the principle of respecting the superior, and it is righteous for the resource allocator to distribute resources in accordance with the principle

of favoring the intimate. It should be emphasized that the Confucian concept of yi (righteousness) is frequently translated into English as justice. However, the meaning of yi is completely different from the concept of universal justice in Western culture (Rawls, 1971).

Yi is usually used in connection with other Chinese characters like ren-yi (literally,

benevolent righteousness or benevolent justice) or qing-yi (literally, affective righteousness or affective justice).

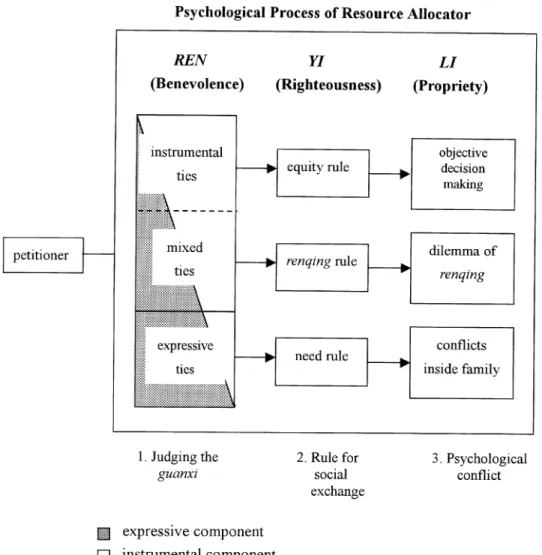

In an earlier article entitled ‘‘Face and favor: The Chinese power game’’ (Hwang, 1987) I diagrammed the dynamics of Chinese social interaction. The Confucian ethics for ordinary people can be mapped into my theoretical Face and Favor Model (Figure 1) in the following way. The expressive component in the relationship (guanxi) corresponds to the concept of

ren. Yi is to choose an appropriate rule for exchange by considering the expressive

component (or affection) between the actors. After careful consideration, the final behavior should follow the social norm of politeness (li).

Figure 1 Confucian ethical system of benevolence-righteousness-propriety for ordinary people (adapted from Hwang, 1995, pp. 233)

In Figure 1, a diagonal bisects the rectangle denoting guanxi (interpersonal relationship). The shaded section represents the instrumental component, and the unshaded section represents the expressive component of the relationship. ‘‘Instrumental’’ refers to the fact that as biological organisms, people have a variety of innate desires. Usually they must interact with others in an instrumental manner to obtain the resources required to satisfy these desires. The expressive component denotes interpersonal affection between two parties. The instrumental component mingles with the expressive component in all interpersonal relationships. There are three types of interpersonal relationships: expressive ties describe relationships within the family, mixed ties include relationships with acquaintances outside the immediate family, and instrumental ties are established between oneself and a stranger simply for the purpose of acquiring a particular resource.

Emphasizing the principle of respecting the superior in procedural justice, and the principle of favoring the intimate in distributive justice constitutes the formal structure of Confucian ethics for ordinary people. While this formal structure is manifested in many types of interpersonal relationships, Confucians also made specific ethical demands on certain special relationships. Confucians conceived five cardinal ethics for the five major dyadic relationships in Chinese society, proposing that the social interaction between members of each pair should be constructed on the basis of the Way of Humanity. However, each of the roles or functions in these five cardinal relationships is distinctive, indicating that the core values that should be emphasized in each are also different:

Between father and son, there should be affection; between sovereign and subordinate, righteousness; between husband and wife, attention to their separate functions; between elder brother and younger, a proper order; and between friends, friendship. (The Works of Mencius, Chapter 3A: Duke Wen of Teng)

Three of these five cardinal ethics were designed for regulating interpersonal relationships with the family (expressive ties). The other two relationships – friends and sovereign/subordinate – are mixed ties. It should be noted that, except for the relationship between friends, the remaining four relationships are vertical ones between superiors and inferiors.

What are the things which humans consider righteous (yi)? Kindness on the part of the father, and filial duty on that of the son; gentleness on the part of the elder brother, and obedience on that of the younger; righteousness on the part of the husband, and submission on that of the wife; kindness on the part of the elders, and deference on that of juniors; benevolence on the part of the ruler, and loyalty on that of the minister. These are the ten things which humans consider to be right. (Li Chi, Chapter IX: Li Yun)

In the above passage, which does not include a reference to relationships between friends, the idea that social interaction in these role relationships should follow the principle of respecting the superior is paramount. Stated more precisely, in accordance with the idea of ‘‘the ten things of righteousness (yi),’’ persons who assume the roles of father, elder brother, husband, elders, or ruler should make decisions in line with the principles of kindness, gentleness, righteousness, and benevolence respectively. And for those who assume the roles of son, younger brother, wife, juniors, and minister, the principles of filial duty, obedience, submission, deference, loyalty and obedience to the instructions of the former group apply.

Positive and negative duties

This section describes the significant features of Confucian ethics in terms of the distinctions between perfect/imperfect and negative/positive duties as proposed by Western scholars. The inadequacy of the Western ethics of rationalism in the understanding of Confucian ethics is explored, and a revised system of concepts to denote the significant features of Confucian ethics constituted on the basis of interpersonal affection is proposed.

According to Nunner-Winkler (1984, p. 349), the distinction between perfect and imperfect duties was first introduced by Kant (1797/1963) in his Metaphysik der Sitten, and later elaborated as negative and positive duties respectively by Gert (1973) in his book The

Moral Rules. Negative duties simply require abstention from action (for example, do not

kill, do not cheat, do not steal). They are duties of omission. So long as they are not in conflict with other duties, they can be followed strictly by anyone in any situation with regard to all other persons. In Kant’s metaphysics of morality, they are termed perfect duties. Positive duties are usually stated as maxims that guide actions (for example, practice charity, help needy persons). They are duties of commission, but they do not specify which and how many good deeds have to be performed and whom they are to benefit so that the maxim can be said to have been performed. The application of any positive maxim requires the actor to take into consideration all concrete conditions and to exercise powers of judgment. Because it is impossible for an individual to practice any positive maxim all the time and with regard to everybody, positive duties are called imperfect duties in the terminology of Kantian ethics. In Western theory perfect and negative duties are equivalent, as are imperfect and positive duties.

The theoretical analysis presented above is a meta-ethical reflection on the nature of the Western ethics of rationalism. Trying to understand the properties of Confucian ethics with the same line of reasoning leads to a series of problems. According to Kantian reasoning, all ethical demands emanating from the Confucian Way of Humanity are imperfect duties. However, Confucians believe that the Confucian ethics for ordinary people entails both perfect and imperfect duties. This seeming contradiction is a crucial point in understanding the difference between Eastern and Western philosophies, so it should be elaborated further. The Confucian Way of Humanity consists of both positive and negative duties. The positive duty of benevolence means doing favors by giving various resources to others. But, how can ordinary people with limited resources possibly practice the positive duty of benevolence towards all other people? Mencius proposed a rule of thumb: take care of one’s own aged parents first, and then extend your care to aged people in general; look after one’s own children first, and then extend love to others’ children (The Works of Mencius, Chapter 1A: King Hui of Liang). Mencius advocated hierarchical love, or love with distinction. Love one’s parents who are the origin of one’s life first of all, then extend love to other people in accordance with one’s relationship (degree of intimacy) with them. Practicing this love with distinction is in accordance with the Confucian ethics for ordinary people and represents virtue.

The Confucian Way of Humanity also consists of negative duties as represented by the silver rule: do not do to others what you do not want to be done to you. The term ‘‘others’’ in this sentence denotes other people in general, including those who do not belong to any of the categories in the five cardinal relations. Putting this idea in the terms of the Face and Favor Model (Figure 1), the principle of negative duties is applicable not only to interpersonal relationships consisting of affective ties or mixed ties, but also to those involving instrumental ties.

The silver rule is a negative duty. It can be followed strictly by any person in any situation, so it should also be a perfect duty. However, from the perspective of Kantian ethics, all demands emanating from the Way of Humanity, regardless of whether they are positive or negative duties, are all considered imperfect duties. Kant was a rationalist. He proposed that there is a single categorical imperative applicable to all rationalists: act so that the outcome of one’s conduct is ‘‘the universal will.’’ Principles derived from an individual’s feelings, affections, dispositions, or preferences may not be universally applicable to others, and should be considered merely subjective principles. The fact that an individual following the silver rule must rely on personal feelings and preferences led Kant to include a footnote in his book Metaphysik der Sitten pointing out that this Confucian maxim cannot be a universal law, for it

contains no basis for prescribing duties to oneself or kindness to others (e.g., many people would agree that others should not help him or her if they don’t expect help themselves), or clearly demarcated duties towards others (otherwise, the criminal would be able to dispute the judge who punished him, and so on). (Kant, 1797, 1964, p. 97)

This conflict exemplifies the inappropriateness of simply transferring constructs from a Western ethical system to a Confucian based system. In the following section a new system of concepts to discern the features of Confucian ethics of interpersonal affection with respect to perfect and imperfect duties is proposed.

Ethics of affection

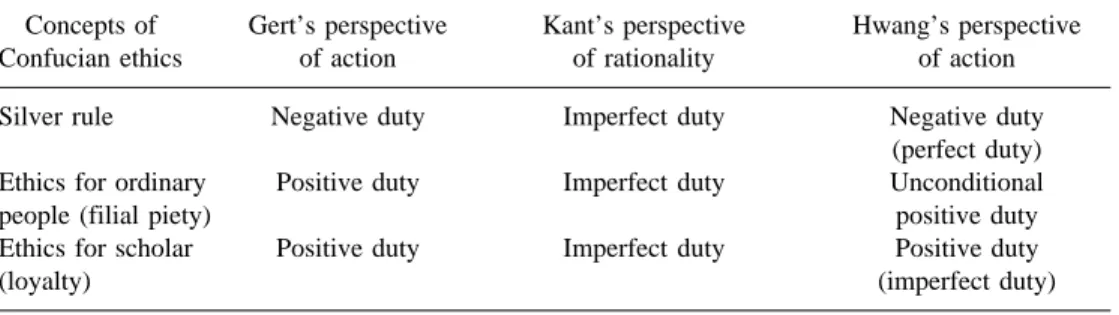

The contents of the Confucian Way of Humanity can be classified into three categories on the basis of the moral agent’s omission/commission of conduct: negative, unconditional positive, and positive duties (Table 1).

As discussed above, the silver rule is a negative duty that serves as a principle of conduct for life (The Analects: Yen Yuan). So long as it is not in conflict with other duties, it can and should be followed by everyone in all situations.

Filial piety, the essential core of the Confucian ethics for ordinary people, is a positive duty. All people should act in a proscribed way towards their parents. However, in the Confucian perspective an individual does not have a choice in deciding whether or not to be filial. The Confucian view of life emphasizes that one’s life is an extension of one’s parents’ lives, so doing one’s filial duty is clearly an obligation, and not behaving in accordance with Table 1 Significant features of Confucian ethics from the perspective of action, rationality, and

affection

Concepts of Gert’s perspective Kant’s perspective Hwang’s perspective

Confucian ethics of action of rationality of action

Silver rule Negative duty Imperfect duty Negative duty

(perfect duty) Ethics for ordinary Positive duty Imperfect duty Unconditional

people (filial piety) positive duty

Ethics for scholar Positive duty Imperfect duty Positive duty

filial piety is an unforgivable fault. Filial piety is not just a positive duty, it is an unconditional positive duty. According to Kant’s definition, since filial piety is a type of positive duty, it must be an imperfect duty; it cannot be a perfect duty. The correlation between positive and imperfect duties does not hold for Confucian ethics.

The idea of unconditional positive duty bears closer examination. The attributes of filial piety can best be understood by looking at the sharp distinction between the Confucian discourses on the relationships of father and son and those on sovereign and minister. During the Warring States Period (403 to 221BC), Confucians requested that everyone practice the ethics for ordinary people, but they did not think that every ordinary person had an equal right to make judgments that could impact public opinion. On the contrary, they endowed intellectuals with a sense of mission to realize Confucian cultural ideals. In order for a scholar to occupy a high position in the government, he must be educated to obtain a desire to practice the Way of Humanity to the best of his ability. The larger the scope in which one exercises the Way of Humanity, the higher one’s moral performance will be. Hence, Confucians encouraged scholars to ‘‘cultivate themselves, manage their families, govern the nation, and soothe the world.’’

In the Warring States Period, the sovereign of a state held the highest power. According to the principle of respecting the superior, he also had the highest power of decision-making. Therefore, Confucians thought that once a scholar became an official, the most important way for him to act on Confucian ideals would be to ‘‘serve (guide) the sovereign in the Way of Humanity.’’ Speaking in Confucian terms, serving the sovereign in the Way of Humanity shows loyalty, and the most important duty for a minister was to ‘‘rectify what is wrong in the sovereign’s mind’’ (The Works of Mencius, Chapter 6B: Kao Tze).

‘‘Benevolent sovereign with loyal minister’’ is an ideal relationship advocated by Confucians. However, when a sovereign wants to behave in a manner contradictory to the principle of benevolence, what should a loyal minister do? Although the Confucians proposed the principle of respecting the superior, and advocated the social relationships of kind father and filial son, benevolent sovereign and loyal minister, when the superior violates a moral principle, the subordinate should try to correct him.

However, the relationships between father/son and sovereign/minister belong to two distinctly different categories. If the superior in each of these two social relationships is engaged in morally wrong activities, the subordinates’ reactions involving suggestions for correction will be different. Parents are the origin of one’s life; the blood relationships between parents and children are inseparable. Therefore,

If a parent has a fault, (the son) should with bated breath, and bland aspect, and gentle voice, admonish him . . . If the parent becomes angry and (more) displeased, and beats him until blood flows, he should not presume to be angry and resentful . . . he should follow (his remonstrance) with loud crying and tears . . . showing an increased degree of reverence, but without abandoning his purpose. (Li Chi)

In other words, showing filial piety to one’s parents is an unconditional positive duty, which should be carried out in spite of any fact one finds out about one’s parents.

The relationship between sovereign and minister is completely different. There was a time when King Hsun of Chi asked Mencius for advice about the office of high ministers. Mencius remarked that there is a distinction between a relationship in which the high ministers are in the nobility and are relatives of the prince, and those in which they have different surnames from the prince. For those in the first category who have a blood connection with the prince, if

the prince makes serious mistakes and does not respond to their respected admonitions, the minister should supersede the prince if he might do harm to the state.

High ministers with different surnames from the prince have no inseparable connection with him. If the prince makes mistakes and does not accept their repeated advice, they can just leave the state for another one. If the only emperor is tyrannous and does not practice benevolent government, then powerful chiefs of state should step forward and ‘‘punish the tyrant and console the people’’ (The Works of Mencius, Chapter 1B: King Hui of Liang).

It is obvious that, although being a benevolent sovereign and being a loyal minister are defined by the Confucians as positive duties for both roles, a minister should take into account all the objective conditions to determine whether the sovereign deserves loyalty. In other words, being loyal is a typical imperfect duty in the Kantian sense, and may be termed a ‘‘conditional positive duty.’’

The term ‘‘conditional’’ is redundant, because all positive duties are conditional according to the original definition. The redundant label is proposed here merely to signify the sharp contrast between conditional and unconditional positive duties, the latter being a unique attribute of filial piety. Loyalty is labeled as a positive duty in Table 1.

Discretionary features

A core component of the Way of Humanity is filial piety. Confucians conceived fulfillment of filial duty as a mandatory natural law of ethics. In comparison with Kohlberg’s postconventional morality, the Confucian ethics for ordinary people also has several discretionary features which can be described with reference to Shweder’s analysis presented in the Mandatory and discretionary concepts section. (1) Confucians recognized that one’s life is an inheritance from one’s ancestors, and they never conceived of the existence of a creator independent of human beings. Therefore, one’s whole family is conceptualized as a ‘‘great self’’ (da wo), and boundaries of the self are extended to include other family members. The physical self is only a part of the great self, and it is the great self that the individual is obligated to protect against any threat from outside. (2) The natural law of Confucian ethics was built on conceptions of natural duties and goals rather than on natural rights (Huang, 1997). (3) Natural law was based on social roles and statuses rather than on a notion of the individual who is prior to society. Individualism is devalued in Confucianism. (4) Although Confucians conceived every person as a moral agent, moral performance was evaluated on the basis of how broadly benevolence was applied. Thus, all people were not seen as morally equivalent. (5) For this reason Confucians endowed scholars with the mission to practice the Way of Humanity when they had a chance to serve government offices. (6) Confucians strongly opposed secularism. They believed that moral principles could be revealed and handed down to ordinary people by a sage or prophet.

This comparison between Kohlberg’s postconventional morality and the Confucian ethics for ordinary people indicates that each has its own mandatory and discretionary features. They represent two rationally defensible moral codes or divergent rationalities. Put in terms of Max Weber’s (1978) classification system, the former is a formal rationality, while the latter is a substantive rationality (Brubarker, 1984). The question remains as to whether it is possible for two divergent rationalities to be in conflict with each other.

The Confucian dilemma

The answer to this question should be ‘‘Yes.’’ As discussed above, the abstract idea of natural law, the abstract principle of harm, and the abstract principle of justice in Kohlberg’s

postconventional morality are mandatory to most rational thinkers. They are also accepted by Confucians. However, Confucians also conceptualize filial piety as a mandatory unconditional positive duty. This addition makes it very likely that these two divergent rationalities will be in conflict with each other. Several stories about this kind of conflict can be found in Confucian classics.

Duke Yeh boasted to Confucius: ‘‘In my state virtue was such that once when a father stole his neighbor’s sheep, his son reported the crime to the state.’’ Confucius replied: ‘‘In my state virtue was different from that, for a son would cover up his father’s misbehavior, and vice versa.’’ (The Analects: Tze-lu)

‘‘Do not steal’’ is a universal negative duty, as the conduct of stealing violates the abstract principle of harm. But, according to Confucian ethics doing one’s filial duty is a person’s first priority. When these two mandatory principles are in conflict with each other, Confucius sided with the fulfillment of filial piety instead of not stealing.

The Works of Mencius also recorded a story about the resolution of a similar dilemma.

Once a pupil asked Mencius a hypothetical question: When Sage King Shun ruled the country and Kao-yao was his minister, if Shun’s father Ku-sou had murdered somebody, what would have been done? (The Works of Mencius, Chapter 7A: Use All Your Heart and Mind).

Mencius’ answer represented a Confucian resolution to the moral dilemma. As a sovereign of the state, Sage King Shun should not forbid a legal officer from arresting his father who had committed a murder. But, as a filial son to his father, he could not permit his father to be punished. Mencius suggested he give up the post of sovereign and escape with his criminal father to a far place beyond the power of law. To Confucius it seemed that such a resolution must be most appropriate. It is reasonable (li) on the one hand, and it protects both personal preference (qing) and laws of the state (fa) on the other.

This resolution might be challenged by a Kantian demand for universal moral judgment. What if everyone else did the same as the sovereign (Fu, 1973)? This is an insoluble question to the substantive ethics of Confucianism.

Adjustment of Confucian ethics

In traditional Chinese society, people may not have been fully aware of the problems inherent in Confucian ethics. However, when people’s consciousness of human rights was raised by the importation of Western culture into Chinese society, the Confucian Dilemma brought Confucianism to a crisis. The invasion of China by Western forces that began at the end of nineteenth century produced drastic changes in various aspects of Chinese society, including its economy, politics, and culture. Confucian ethics were no exception to this process. Confucianism was affected by several important Chinese social movements during the early part of the twentieth century, including the New Culture Movement and the Gong

De (Public Virtue) Movement. These two events deserve attention because both resulted in

adjustments to the structure of Confucianism.

During the early Republican years, President Yuan Shih-kai (term of office 1912–1916) attempted to restore the imperial monarchy. Towards this goal, he ordered that the Confucian classics be studied in the educational system, and tried to establish Confucianism as the national religion, generating bitter debate among intellectuals. The controversy provoked strong criticism of Confucianism in the New Culture Movement, especially of the

Confucian theory of the Three Bonds, which requires subordinates to follow the guidance of superiors in three major human relationships: father and son, sovereign and minister, and husband and wife. Proponents of the New Culture Movement argued that the request for submission precluded sons, ministers, and wives from having independent personalities, and charged that the Three Bonds concept was a ‘‘morality for slaves,’’ rather than a ‘‘morality for masters.’’ Confucian ethical requirements were even condemned as a ‘‘dinner set for eating humans.’’ The socio-political atmosphere of China at that time led young intellectuals to believe that ‘‘Mr Science’’ and ‘‘Mr Democracy’’ from the West were the new saviors for the nation, and any cultural tradition that was contradictory to this new Zeitgeist should be eliminated. The New Culture Movement soon evolved into a zeal of totalistic anti-traditionalism and radical iconoclasm (Lin, 1979), and laid the foundation for the Cultural Revolution after the Communists took control of mainland China.

The Gong De Movement also produced remarkable stimulation for the transformation of the Confucian ethical system. A historical study on this topic by J. S. Chen (1997) indicated that the concept of gong de (literally, public morality or public virtue) originated from the Japanese concept of kotoku, which emerged in the Meiji era. The concept of kotoku was used by Japanese to denote the moral responsibilities one has towards public interests and other individuals in society. It was introduced by Liang Qi-chao to his Chinese readers in 1902 as part of a campaign advocating sacrificing oneself for the sake of society. It emerged after the Chinese defeat in the 1894 Sino-Japanese War. In his interpretation of this idea, Liang emphasized an individual’s devotion to the general welfare of one’s nation. However, the collectivistic or nationalistic connotation of this concept soon weakened and its meaning became increasingly similar to its counterpart in Japan.

After the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan, an exchange student from America whose Chinese name was Di Renhwa published an article in the Central Daily

News in 1963. In it he cited many examples of his personal experiences in Taiwan in order to

denounce the Chinese people for their lack of public morality. This paper prompted a widespread response from Taiwanese society, and students at National Taiwan University soon initiated the ‘‘The May 20th Social Movement for Self-Awakening.’’ J. S. Chen (1997) examined the concepts related to gong de mentioned in the mass media at that time. His analysis revealed that these concepts were usually used to denote negative civic behavior or restraints on citizens from damaging the public interest and interfering with the social behavior of others. They had nothing to do with social and political participation in the public sphere.

Both the revolution of the Three Bonds and the movement for Gong De have significant implication for the transformation of the Confucian cultural tradition. As mentioned previously, the Confucian ethics for ordinary people upheld the principle of respecting the superior in its procedural justice, and emphasized the principle of favoring the intimate in its distributive justice. The Three Bonds are in fact manifestations of the aforementioned formal structure of ethics for ordinary people in the three sets of role relations between father and son, sovereign and minister, and husband and wife, with special emphasis on the principle of respecting the superior. The revolution on the Three Bonds implies a tendency to de-emphasize the vertical quality of these three relationships, and to rearrange them in a more egalitarian way.

In addition to this shift in power relations, the revolution on the Three Bonds also changed the principle of favoring the intimate. Viewed from the perspective of the Face and Favor Model (Figure 1), after people are liberated from their families, they have increasing opportunities to interact with persons with whom they have instrumental ties, and to follow

certain universal standards in these interactions. Gong de is one kind of universal standard. Although it is essentially a set of negative duties that originated through the stimulation of foreign cultures, most of its ideas are compatible with the Confucian silver rule, and can be viewed as practical elaborations of that maxim.

Reinterpreting empirical findings

Cultural ideas

The analysis of Confucian ethics thus far has described the Confucian cultural ideas for guiding people’s social interactions. These core cultural ideas constitute the collective reality that is reflected in philosophical or ideological texts telling people what is good, what is moral, and how to be a person. They are transmitted to individuals through the social-psychological processes of child-rearing practices, educational systems, customs, legal systems, and become the individual’s reality (Markus & Kitayama, 1994). For instance, the social communication theory of moral development (Shweder & Much, 1991; Shweder et

al., 1990) advocated that in order to maintain the routine activities of social life, guardians of

the moral order (for example, parents, teachers, peers) present and convey to children powerful morally relevant interpretations of events through verbal exchanges in the context of daily life situations.

The collective reality, just like the collective conscience (Durkheim, 1989/1953), can exist independently of any particular individual. Only a few experts on culture can explicitly state the meanings of core cultural ideas (Menon & Shweder, 1994), while most ordinary people can only recognize and deliberate parts of their collective or individual realities. Once cultural ideas are articulated, they may become objects of consciousness and reflective thought, and form the basis for intentional acts.

Because the culture of contemporary Taiwan is a hybrid of Chinese tradition and foreign commercial civilizations, children there grow up in an atmosphere of cultural pluralism, and may shape their self-ideals in terms of Western ideas of individualism. With this expectation in mind, we begin an examination of the findings of previous research on moral reasoning in Taiwan.

Postconventional thinking

Kohlberg’s Moral Judgement Interview (MJI) is used to assess moral development. The procedures typically used in research on Chinese moral reasoning require translating Kohlberg’s dilemmas of life vs. law, conscience vs. punishment, and contract vs. authority into Chinese with some adjustments to accommodate domestic culture, administering them to Chinese subjects who are in different developmental stages, asking subjects a series of questions, and then evaluating their responses in accordance with the standardized scoring system. Fu & Lei (1991) aggregated empirical data from several studies using this procedure (Figure 2), and compared them with longitudinal data from American subjects collected by Kramer (1968) and Turiel (1974) (Figure 3). Several trends emerge from a comparison of these two figures:

1. Preconventional stage. The obedience and punishment orientation of Stage 1 and the

instrumental purpose and exchange orientation of Stage 2 were consistently decreased in both Chinese and American samples. After age 16, both stages had disappeared in the

Chinese sample, but some American subjects still used moral reasoning from these stages on. These findings suggest that the moral reasoning of Chinese children matured earlier than that of American children.

2. Conventional stage. The interpersonal accord and conformity orientation of Stage 3

decreased continuously for the American sample, but the social accord and system maintenance orientation of Stage 4 increased constantly and became the dominant stage in their later adolescence. The Chinese samples were different. Prior to age 14, there was no Stage 4 thinking. Stage 3 increased from age 8, and became the dominant stage after age 13, reaching a peak of 90% usage at age 16. After that, Stage 3 decreased quickly, while Stage 4 increased rapidly and became the dominant stage at age 18. Compared with their American counterparts, Chinese subjects reached Stage 4 of moral development later.

3. Postconventional stage. As found in previous research (Kohlberg et al., 1983, p. 60),

Stage 6 thinking involving universal ethical principles was not empirically identifiable in either group, so it was dropped from the final analysis. Some of the American samples began to use a Stage 5 orientation, valuing social contracts, utility, and individual rights after the age of 13, but the Chinese samples did not do so until age 20. If we accept Gibbs’ (1997) argument that Stages 1 to 4 are genuine stages of cognitive development, the differences between Chinese and American samples in the preconventional and conventional stages can be attributed to cultural differences in child-rearing practices (for examples see Ho, 1986; Wu, 1996). The findings partially supported Kohlberg’s (1981) hypothesis. Individuals in both cultures go through the same sequence of Figure 2 Percentage of moral reasoning at various stages by different age groups of Chinese

gross stage development, although they vary in their rate of development. However, differences in moral reasoning between the two groups emerge after age 13 when the American subjects begin to use a Stage 5 orientation. This difference may reflect a contrast in divergent rationalities or normative philosophies rather than in cognitive development or maturation.

This explanation is consistent with the definitions of the standards for evaluating the stages of moral development. According to Kohlberg (1981), an individual at Stage 5 may be aware that people hold a variety of values and opinions, and that most values and rules are relative to one’s group, but should usually be upheld because they are part of a social contract. However, some non-relative values like life and liberty must be upheld in any society regardless of the majority opinion. This standard clearly reflects the Western value of individualism that considers the human rights of life and liberty to be non-relative values, while collectivist values or positive duties towards specific targets are disregarded as relative values.

Considering the Confucian perspective that one’s family is an inseparable part of one’s life, and relationships between parents and children are construed as one’s own flesh and blood, it is very hard for an individual in a Confucian culture to conceive of positive duties to family members (especially towards parents) as part of a relative social contract. The standard for scoring imposes Western cultural values on non-Western cultures.

Principled thinking

The above conclusions are also supported by empirical research findings using other measurement methods. For example, Rest and his colleagues constructed the Defining Issues Figure 3 Percentage of moral reasoning at various stages by different age groups of American

Test (DIT) which presents subjects with six moral dilemmas. For each of these stories, subjects have to read a set of twelve statements defining the crucial issue of the hypothetical moral dilemma, and then identify and rank the four most important issues (Rest, 1976; Rest, Cooper, Coder, Masanz & Anderson, 1974). Because some of the issue statements define the dilemma according to a principled moral perspective of Kohlberg’s Stage 5 and 6, a score of principled moral thinking (P-score) can be computed for each subject by assessing the extent to which that subject selects and ranks principled statements across the six dilemma situations.

Rest’s DIT method has been used by a number of psychologists to collect data in Taiwan (Chen, 1980; Gendron, 1981; Sang, 1980) and Hong Kong (Ma, 1988; Ma & Cheung, 1996). A cross-cultural study indicated that though all samples showed increasing levels of principled judgment with higher age/education, Taiwan and Hong Kong samples tended to show a flatter rate of developmental increase than American samples (Rest, Thoma, Moon & Getz, 1986). Fu & Lei (1991) aggregated the findings of previous studies and compared their principled values with their American age-mates (Figure 4).

The mean difference between P-scores for the two cultural groups was small (only 1.7%) but significant (t (1645) = 3.93, p<.01). The discrepancy between these two groups increased with age. It was 5.3% for high school students, and 6.8% for college students. The age trend indicates that the extent to which principled thinking was used in the Chinese sample increased more slowly than among their American counterparts.

Rest’s DIT is different from Kohlberg’s Moral Judgement Interview (MJI) in nature. The MJI is a spontaneous production test for qualitative assessment of the structure of moral development, while the DIT is a recognition test for quantitative assessment of a person’s probabilistic usage of each of the six stages in Kohlberg’s system. In his cross-cultural research, Ma found a cultural difference in perceiving the Stage 4 issue-statements between the Hong Kong Chinese and the English and American subjects (Ma, 1988; Ma & Cheung, 1996). The Chinese tended to regard the Stage 4 statements as more similar to those of Stage 5 and 6, whereas the English and Americans tended to regard Stage 4 statements as more like those of Stage 2 and 3. The significant cultural difference lies in statements that refer to absolute authority such as God or institutionalized legal authority. A deletion of those items from Hong Kong data provided much stronger support for the hierarchical structure of Kohlberg’s stages of moral development (Ma & Cheung, 1996). Ma concluded that the MJI is suitable for tackling basic issues in cross-cultural studies, and that the DIT may not be appropriate for this purpose.

Ma’s argument is quite plausible. The DIT is certainly a culturally biased instrument of measurement. But, the question of how to explain the aforementioned findings remains.

An adequate interpretation of these findings requires acknowledgment that principled thinking does not imply a tendency for insisting on universal principles of negative duties or the perfect duties in Kant’s ethics. This point is illustrated by an issue raised by Gilligan’s criticism of Kohlberg’s theory. Gilligan (1977), a feminist, differentiated two categories of morality; namely, an ethic of care and responsibility, and an ethic of rights and justice. The eminent goals of the ethic of care are to help and take care of others, to have a feeling of concern and compassion for others, to meet one’s obligations and responsibilities, and to discern and alleviate others’ troubles. In contrast, the ethic of rights and justice is concerned with the protection of invulnerable rights of individuals. Such absolute rights are valid for all persons at all times and places. An appropriate practice of the ethic of care and responsibility has to take into consideration the contextual particularities of the situation, while the application of principles of justice is context free.

The characteristics enumerated by Gilligan (1977) indicate that the ethic of care and responsibility tends to correspond to imperfect duties, while the ethic of rights and justice tends to correspond to perfect duties. Therefore, Gilligan accused Kohlberg of constructing his theory based on the rights and justice orientation of an autonomous, independent, and individuated self which is characteristic of males, and neglecting the contribution of the alternative approach to morality. She criticized the fact that Kohlberg’s ‘‘principles of justice [are] context free and [can] generate objectively right solutions to moral problems’’ (Murphy & Gilligan, 1980, p. 83). These context-free principles replace the social act of moral thinking by ‘‘structures of formal thought that provide a rational system for decisions that is autonomous and independent of time and place.’’

It is interesting to find that Yeh (1996, 1997) followed a similar way of thinking. She examined the characteristics of the concept of Chinese jen, and found that it is similar to Gilligan’s ethic of care, and contrasts with Kohlberg’s ethic of justice. The ethic of care and responsibility addressed by Gilligan is primarily oriented towards imperfect duties while the ethic of rights and justice is primarily concerned with perfect duties.

Actual duties and prima facie duties

Nunner-Winkler (1984) argued that Gilligan misunderstood Kohlberg’s position. He cited the differentiation between actual duties and prima facie duties introduced by W. D. Ross Figure 4 Means and SDs of P-index by Chinese and American students (adapted from Fu and

(1930), and emphasized the point that moral rules are valid only prima facie; that is, under normal circumstances, when there are no other moral considerations that bear on the decision (Nunner-Winkler, 1984, p. 352). In fact, consideration of the situational context is a prerequisite for all actual moral judgments. Kohlberg’s scoring system was constructed on the assumption of a clear hierarchy of duties and obligations. For instance, in the case where Heinz steals a drug in order to save his wife’s life, he argued that the right to life supersedes the right to property.

For Kant, the hierarchical ordering of duties is based on their formal characteristics (for example, perfect duties are superior to imperfect duties). However, Kohlberg arranged his hierarchy of rights by content. The right to life is treated as if it were a perfect duty of the highest priority. It must be granted universally regardless of concrete circumstances. For Kohlberg, to steal for a stranger is as much a duty as to steal for one’s spouse. The duty would be accorded universally to all humans whose lives can be saved regardless of personal ties (Colby et al., 1979, p. 82; cited in Nunner-Winkler, 1984, p. 354).

Kohlberg’s arguments represent his position on Western individualism and rationalism without ambiguity. By the same token, when Chinese people make an actual moral judgment, they certainly take into account the overall situational context. However, the positive duty of utmost priority for most Chinese is not the individual’s right to life, rather it is the ethic of filial piety along with the accompanying idea of love with distinction. With this sharp contrast in mind, we may begin our task of reinterpreting Chinese moral reasoning that was unscorable according to Kohlberg’s scoring manual.

Filial piety and love with distinction

Previous research using Kohlberg’s paradigm to collect moral reasoning data in Chinese society frequently encountered the problem that many of the subjects’ responses could not be scored according to Kohlberg’s standardized scoring system. Most of these unscorable responses were related to the concept of filial piety and hierarchical love with distinction (Cheng, 1991; Lei & Cheng, 1984; Ma, 1997). Lei found that the Chinese traditional values of filial piety and collective utility were misrepresented in criterion judgments given under Stage 3, and no examples were given under Stage 5. The misclassification was made in ignorance of the pre-eminent value of filial piety in Chinese culture. As a consequence, the selection of scorable interview judgments tended to concentrate subjects’ responses into conventional levels (Lei & Cheng, 1984, p. 11). Lei also noted that a ‘‘judgment which resolves the dilemma between the fulfillment of filial piety and the commitment to personal principles has not appeared in the scoring manual’’ (Lei & Cheng, 1984, p. 14). Lei did not systematically analyze the unscorable moral judgments, and felt it premature to make specific claims about the cultural patterning of the unscorable responses (Snarey, 1985, p. 224).

In an article entitled ‘‘Cross-cultural investigation on development of moral

judgment,’’ Shall-way Cheng (1991) used four dilemmas to interview 160

undergraduate students at National Taiwan University. She analyzed the responses of 40 seniors, and classified the unscorable moral reasoning into two categories: filial piety, and hierarchical love with distinction. She presented her data in a systematic way and tried to interpret the findings:

Is the cultural significance of my data fully accounted for by my arguments on love with distinction stated above? Could my viewpoints be incorporated into the framework of Kohlberg’s theory? I can not give a definite answer to these questions. (Cheng, 1991, p. 365)

Cheng’s assessment is quite illuminating, but not sufficient to provide a comprehensive interpretation of her findings. Her data are so valuable that a satisfactory reinterpretation is urgently needed so that they can make the contribution to the literature that they warrant.

As Shweder and Much (1991) suggested, the statements given by informants about their reasons for making their moral judgments may seem ‘‘thin’’ and obvious, but analysis can discern their implied meanings by way of what Geertz (1973) called ‘‘thick description.’’ The reasoning elicited by subjects is first-degree interpretation of moral judgments, while a researcher may make second-degree interpretation from a particular perspective (Schutz, 1967).

This section of the article attempts to perform a thorough description or second-degree interpretation of the unscorable data collected by Cheng (1991) in terms of my analysis of the structure of Confucianism. Using this analysis, the discursive data collected by Cheng (1991) may be reclassified and reinterpreted as follows.

1. Reasons based on love with distinction. We are related by blood; we share the same blood.

An individual’s life is meaningful only to those who care about him. If they don’t care about him, his life is completely meaningless to them.

Every life is precious. But, the meaning of every life is not the same to a person. In the case where one has to steal drugs for saving someone’s life, one has to consider what the meaning of that life is to oneself. One may sympathize with an outsider, but genuine love should be reserved [for somebody whose life is more meaningful].

Living with close relatives, you certainly have affection for them. But, you can hardly have affection for strangers. Their existence is of no importance to you.

When a close relative, for example, Mr. Chen’s wife, is sick, he sees her painful situation every day. The strong external stimulation may elicit his concern about her. If she is not as close to him, his feelings may not be so intense. Intimacy of relationships is not unchanging; it is determined by frequency of contact. (Cheng, 1991, p. 355)

In the statements presented above, subjects attempted to support the idea of love with distinction with various reasons, including blood relationships, the meaning of the other person’s life to the individual, residing together, and frequency of contact. Those and other reasons can be used to support the idea that the affective component (love) should be different for distinctive relationships. This idea can be traced to the Confucian advocacy of extending benevolence from the near to the distant.

2. The norm of reciprocity.

Interpersonal relationships are different in their intimacy and remoteness: Everybody has some dear ones who are more helpful, and many indifferent persons who never help him.

Your close relatives have extraordinary devotion to you. Interpersonal relationships should be reciprocal and complementary. You have a heavier duty to repay those who gave you more. Of course you may do a favor for a stranger, but you certainly have a stronger tendency to take care of those who go through life with you. Because I know him, our hearts already connected.

If you received more favors from them, you have a stronger moral duty to repay them. Interpersonal relationships should be reciprocal with each other.I have been educated to love without distinction since I was young, but I found that I can not do so. Doing so is unfair to my close relatives. (Cheng, 1991, p. 356)

Reciprocity is a universal norm for social interaction in any human society (Gouldner, 1960). Confucian society is no exception to this pattern. An individual’s personal network of social relationships is constructed on the basis of reciprocal interactions (Hwang, 1987). However, cultures vary in providing reasons for the necessity of reciprocating with others. In my paper ‘‘A reconstruction of Confucian perspective on self and interpersonal relationships,’’ I stressed that Confucians conceptualized an individual’s life as part of a great body (da ti); that is, one’s life is one’s family (Hwang, in press). Resource allocators in a family should do their best to satisfy the needs of others by following the need rule, while recipients are obligated to reciprocate favors.

Parents are the origins of one’s life. People have the utmost filial obligation to repay the unending debt to their parents. Compared with this obligation, one’s moral obligation to reciprocate with other family members may be decreased according to the affective component of that relationship. One should interact with acquaintances in one’s social network in accordance with the renqing rule; that is, one should help others when they are in need of assistance. When one receives a favor from another person, one should make an effort to repay. However, there is no moral obligation for the positive duty to do favors for strangers outside one’s network.

3. Positive duties and negative duties.

A person has a limited capacity to help. One meets a huge number of people in daily life. If one has to offer the same amount of energy for moral duties to everybody, one will be exhausted. (Cheng, 1991, p. 358)

Interpersonal affection emerges from mutual understanding through social interaction. The reason I am concerned about somebody is that I have affection for him. I don’t have any affection for a stranger. I don’t know him. I don’t understand him, so I am not concerned about him. I don’t have any duties to him. I won’t hurt him, but I don’t have an obligation to do anything for him. (Cheng, 1991, p. 355)

In the section of this paper entitled ‘‘Positive and negative duties’’, I discussed the distinction between positive duties and negative duties, as well as that between imperfect duties and perfect duties. I argued that the five core Confucian ethics require that an individual practice benevolence by giving various resources to a target who is in a specific role, and that this is essentially a positive duty. The concept of public morality (gong de) basically consists of duties that are negative in nature. A subject in Cheng’s study mentioned the limitation of resources under one’s control. ‘‘If one undertakes the same positive duties for everybody, one will be exhausted.’’ Another subject stated his attitude towards strangers: ‘‘I won’t hurt him, but I don’t have an obligation to do anything for him.’’ In other words, he considered himself to have negative duties of gong de towards strangers, but to have no positive duties for doing anything for them.

4. Fulfilling one’s own positive duties.

Strangers should have their own family members or friends do this for them. It is impossible for a person to take care of everything.