國

立

交

通

大

學

教育研究所

博

士

論

文

2×2 成就目標之因素結構與預測效用研究

The Factor Structure and Predictive Utility of

the 2 × 2 Achievement Goal Framework

研 究 生:江羽慈

指導教授:林珊如 教授

2×2 成就目標之因素結構與預測效用研究

The Factor Structure and Predictive Utility of

the 2 × 2 Achievement Goal Framework

研

究 生:江羽慈 Student:Yu-Tzu Chiang

指導教授:林珊如

Advisor:Sunny S. J. Lin

國 立 交 通 大 學

教 育 研 究 所

博 士 論 文

A DissertationSubmitted to Institute of Education

Division of Educational and Counseling Psychology National Chiao Tung University

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy in

Education November 2010

Hsinchu, Taiwan, Republic of China

2×2 成就目標之因素結構與預測效用研究

學生:江羽慈 指導教授:林珊如

國立交通大學教育研究所博士班

摘 要

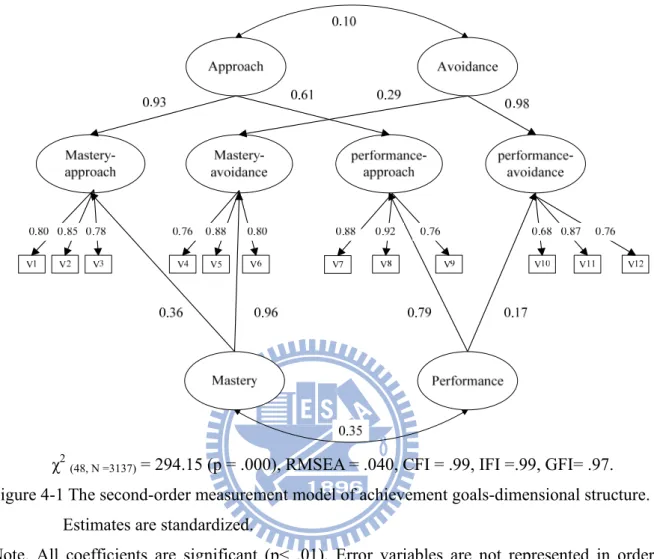

就學習動機的階層而言,成就目標是較具體的動機變項,也是與學習行為最接近、且最直接的 影響變項。過去的研究多以西方學生在數學、自然或歐美語言等領域的成就目標對學習的影響為研 究主題,較少的研究關注我國學生學習國語文的成就動機。本研究以台灣國小到高中的學生為樣本,探討 2×2 成就目標(Elliot & McGregor, 2001)之因 素結構、跨一年的測量穩定度及成就目標在國語文學習歷程的預測效用。首先,以 2007 年的橫斷 資料進行驗證性因素分析,檢驗一階四因素結構適配度是否優於各種選替模式(二、三向度),結果 支持 2×2 成就目標模式的四個因素 (趨向精熟、趨向表現、逃避精熟與逃避表現)是個別存在的。 橫斷資料的二階因素結構適配度也優於各種選替模式,證實 2×2 成就目標符合理論的兩軸因素結 構:第一軸為兩個對能力的定義因素(精熟與表現),第二軸為兩個對能力的定價因素(趨向與逃 避),且此二軸彼此相交,2x2 理論的測量模式受到支持。總之,本研究修訂的成就目標量表(AGQ-C) 在我國國小到高中學生群中具有良好的信度與效度,亦即 2x2 成就目標模式能描述我國學生的學習 目標。此外,研究結果顯示:四個二階因素個別指向其對應的兩個一階因素的徑路係數值大小相差 很多,經由路徑係數的恆等分析檢驗,發現每一對的一階目標對於相對應的二階目標因素有不相同 的效果,亦即每一個二階因素(如:表現)受到特定的一階成就目標(趨向表現)所反映。進一步檢驗 2x2 成就目標在 2007、2008 兩個時段的測量穩定度,指標檢驗指標包括結構穩定度、差異連續性、 平均數穩定度。測量穩定度檢驗結果顯示,兩個時段測量模式的形貌恆等,而模式弱恆等(因素負 荷量恆等)、強恆等(截距恆等)模式也都成立,顯示我國學生的成就目標間隔一年後雖然有所變化, 但具有合理的連續性與穩定度,而且兩個時段的目標均達正相關、只有趨向表現目標平均數有顯著 增加,另三個目標則無顯著差異。預測效用的檢驗以 2007 年的橫斷資料進行共變結構分析,檢驗 成就目標是否能中介國語文自我效能及成績,本研究選擇自我效能,乃因其為社會認知論中重要且 穩固的學習動機指標,長久的國語文學習使自我效能內化為近似於內在穩定的特質,而成就目標與 外在情境的連結較為密切。結果顯示:趨向精熟、趨向表現、逃避表現三個目標可以中介國文自我 效能與國文成績,呼應成就目標理論:成就目標是中介抽象的學習動機與學習行為間的心理建構。 同時,成就目標的定價面向(趨向和逃避因素)之中介效果優於成就目標的定義面向(精熟和表現因 素),比起定義面向,成就目標的定價面向:趨向與逃避因素較能反映台灣學生的成就目標;趨向型 的目標是預測台灣學生國文成績的最有效因子。本研究發現台灣國小到高中學生的實證資料支持 2×2 成就目標模式可以描述國語文學習目標,具有跨年的測量穩定性,成就目標對國文自我效能與 國文成績具有中介效用。本研究提出未來研究的建議及教室教學的實務建議。 關鍵詞:成就目標、成就動機、自我效能、國文成績。

The Factor Structure and Predictive Utility of the 2 × 2 Achievement Goal

Framework

Student:Yu-Tzu Chiang Advisor:Dr. Sunny S. J. Lin

Institute of Education

National Chiao Tung University

ABSTRACT

In terms of hierarchical models of motivation, achievement goals are conceptualized as concrete representations of more abstract motivation dispositions and as the proximal, direct regulators of learning behaviors. The major of research have studied achievement goal endorsement in math, science and language subjects among western students. Unfortunately, little research has been published on Taiwanese students’ adoption of achievement goals in their Chinese language class. The aims of the dissertation were to investigate the measurement structure, cross-year goal-pursuit stability and predictive utility of the 2 × 2 achievement goal model (Elliot & McGregor, 2001) in Taiwanese pre-university students while learning Chinese. Factorial/dimensional structures and internal consistencies provided support for the 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. The 2 × 2 achievement goal structure of the achievement goal items was confirmed, and the four-factor goal structure was found to be a better fit to the data than a series of alternative models with dichotomous/trichotomous goal structures. The results further offered evidence for the two-dimensional structure posited by the 2 (definition) × 2 (valence) achievement goal model. Path coefficient invariance of the dimensional model indicated that each pairs of goal has nonequivalent contribution to correspondent achievement goal dimensional factor: each dimensional factor was mainly derived from different achievement goals. No significant decreases in model-fits (compared to the weak invariant model) when constraints were added to various invariant models. Three stability indexes (structural, differential continuity, and mean-level stability) provided evidence for the stability of achievement goal endorsement over time in a panel sample of Taiwan pre-university students. In terms of predictive utility, three of four achievement goals: mastery-approach, performance-approach, and performance-avoidance were found to be effective mediators between Chinese self-efficacy and Chinese performance. The findings support the rationale that achievement goals are viewed as a direct, proximal influence on achievement-relevant behavior and motives are portrayed as direct antecedents of achievement goals (Elliot & Church 1997). Results of dimensional factor predictive utility, the approach-avoidance factors along the valence dimension seemed to be more successful than the mastery-performance factors along the definition dimension. Approach-based goals were observed for significant predictors of Chinese grades in Taiwanese students. Taken together, my data strongly supports that the 2 × 2 achievement goal framework appears to be empirically as well as conceptually sound for Taiwanese students and have mediating utility on self-efficacy and Chinese grades.

誌

謝

將近四年半的博士班求學歷程,一路走來曲曲折折,終於我拿到博士學位。首先我要 把這本論文獻給在天國的媽媽,從您身上我學到吃苦耐勞與堅強獨立,這樣的特質,讓我 即使身兼國小教職及博士班學生,還能積極的面對各種挑戰。在此我要感謝這段日子以來, 愛護我幫助我的人。碩士班以來就是指導教授的珊如教授,您給了我最多的自由讓我探索 有興趣的學術領域,又時不時給我最睿智的指導,指引我迷津,十年亦師亦友的師生情誼, 永難忘懷。感恩芳銘教授,因為您我學了更高階的統計,多虧有您的指導,讓我的博士論 文的統計方法更臻完整。感謝華葳教授給我建議,讓我的論文得以兼具理論與實務的貢獻。 感謝奕蘭教授的建議,讓論文之理論基礎更扎實、更有邏輯性。感謝淑玲教授的教導,讓 我對動機理論有更深入與不同面向的了解。還要感謝旨峰教授,從碩士班起,您鼓勵我投 稿研討會培養了我對論文寫作的信心,到博士班時投稿期刊您也給我許多實用的建議。還 有淑卿姐,要不是你幫我整理報考博士班的資料,否則我可能連備取交大博班的資格都沒 有,每當有什麼可以申請的經費,您總是第一個通知我,真的好感激您。感謝妤貞,協助 我處理問卷資料與進行統計處理,和你討論得到很多成長,也因和你合作期刊論文,博士 論文之雛型也由此誕生。對於好夥伴朝陽,很榮幸能擔任你的實習輔導老師,你也不負眾 望進入交大碩班,現在直升博班。與朝陽一起執行線上遊戲國科會研究時,感恩你總是幫 忙分擔許多雜務,我們合作的論文也終於被期刊所接受;很高興看著你持續進步,長久的 默契,和你討論總激盪出不同火花。感謝思光老師、善媚、志鴻、欣渝、馨黛、羽恬,謝 謝你們,和你們討論課業都能收穫滿滿。最後,我要謝謝我的爸爸,您不會重男輕女,認 為女兒只要有個美滿婚姻即可,反而鼓勵我要拿學位,為將來擔任教授或學校主任、校長 做準備。謝謝哥哥照顧爸爸,讓爸爸在媽媽過世之後還能樂觀的生活。還有我的三個好姊 姊:其樺、季芸、昀安,包容我這愛佔小便宜又任性的小妹,在我沮喪苦悶時,聽我訴苦、 鼓勵我支持我。還有我的公公婆婆,因為您們的支持,我得以在婚後攻讀博士班。還有最 重要最親愛的元育,謝謝你的寵愛與陪伴,讓我可以專心在研究上,不為過多瑣事而分心。 願把這份榮耀與所有幫助過我的人分享,謝謝大家。 羽慈TABLE OF CONTENTS

Chinese abstract...III

English abstract……….…..IV

Acknowledgement………..…….V

Chapter 1 Introduction...1

Chapter 2 Literature Review...4

Achievement goal theory... 5

Self-efficacy and achievement goals ... 15

Achievement goals and academic performance ... 16

Overview of the present research and hypotheses... 19

Chapter 3 Study 1: First-order factor structure of 2 × 2 achievement goal framework...24

Method... 24

Results ... 25

Chapter 4 Study 2: The second-order factorial structure of the 2 × 2 goal framework ...30

Method... 30

Results ... 30

Chapter 5 Study 3: The stability of the 2 × 2 goal endorsement in a panel sample...35

Method... 35

Results ... 36

Chapter 6 Study 4: The predictive utility of the 2 × 2 achievement goal framework...41

Method... 41

Results ... 42

Chapter 7 General discussions, implications and limitations...47

General discussions ... 47

Implications ... 54

Limitation ... 55

Appendix 1: Questionnaires...65

Appendix 2: Back translation for AGQ-C...66

Appendix 3: The invariance across three school levels...66

LIST OF TABLES

Table 3-1 Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of 12 items for four goals. ... 25 Table 3-2 Descriptive statistics, alpha coefficients of and zero order correlations of achievement

goal indicators... 26 Table 3-3 Fit indices of factorial achievement goal model and other alternative models, all with

first-order factor structure ... 29 Table 4-1 Fit indices of dimensional achievement goal model and other alternative models, all

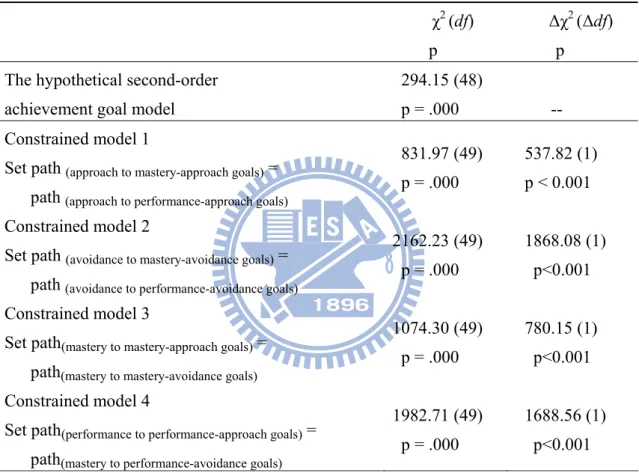

with second-order factor structure ... 32 Table 4-2 Path coefficient invariance analyses of the constrained models nested under

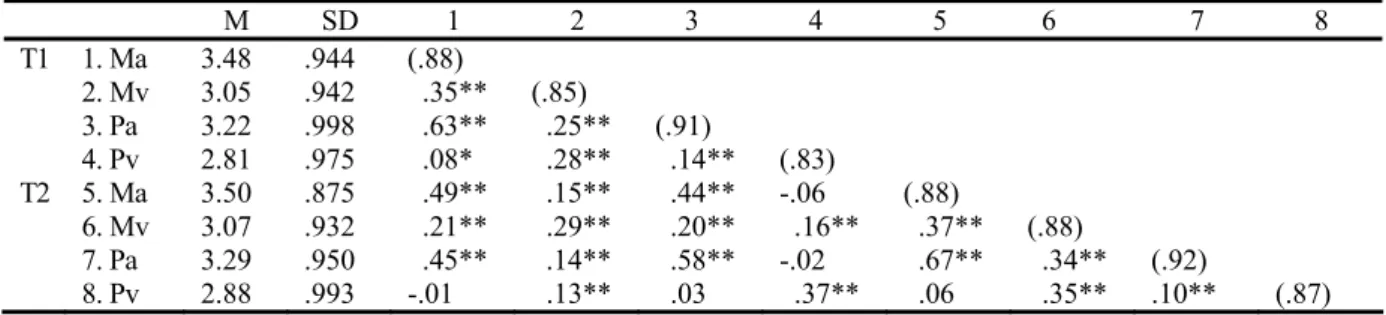

hypothetical second-order achievement goal model... 34 Table 5-1 Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of achievement goal items across Time 1 and Time 2. ... 37 Table 5-2 Descriptive statistics, alpha coefficients of and zero order correlations of indicators of

achievement goals over Time 1 and Time 2 ... 38 Table 5-3 Invariance analyses of four measurement invariance models over time... 39 Table 5-4 Descriptive Statistics, mean-level stability, and differential stability ... 40 Table 6-1 Descriptive statistics, alpha coefficients of and zero order correlations among Chinese

self-efficacy, achievement goals, and Chinese performance ... 43

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 2-1 Hypothetical measurement model of first-order achievement goal structure... 19 Figure 2-2 Hypothetical path diagram of second-order measurement model of achievement goal

dimensional structure... 20 Figure 2-3 Hypothetical path diagram of antecedents and outcomes of four achievement goals. 22 Figure 2-4 Hypothetical structural model of dimensional achievement goals with Chinese

self-efficacy and Chinese performance ... 23 Figure 3-1 The first-order measurement model of achievement goal structure. Estimates are

standardized. ... 27 Figure 4-1 The second-order measurement model of achievement goals-dimensional structure.

estimates are standardized. ... 31 Figure 6-1 The measurement model of Chinese self-efficacy. ... 42 Figure 6-2 The structural model of factorial achievement goals with Chinese self-efficacy and

Chinese performance. ... 44 Figure 6-3 The structural model of dimensional achievement goals with Chinese self-efficacy)

Chapter 1 Introduction

In the areas of student competence and motivation in academic settings, the dominant research interest in the past three decades has been achievement goal theory (Elliot & Church, 1997; Elliot & Murayama, 2008; Middleton & Midgley, 1997; Nicholls, 1984; Pintrich, 2000a). Achievement goals are viewed in terms of the purpose or cognitive-dynamic focus of task engagement and competence-relevant behavior (Elliot & Church, 1997). The specific goal type is thought to establish a framework for how learners interpret and experience achievement settings. Several different achievement goal models have been posited, including dichotomous (e.g., Ames & Archer, 1988; Dweck, 1986), trichotomous (e.g., Elliot & Church, 1997; Middleton & Midgley, 1997), and Elliot and McGregor’s (2001) four-goal model.

Elliot and Church (1997) are among those researchers who have adopted a trichotomous achievement goal model to examine associations among different types of achievement goals, motivational antecedents (e.g., achievement motivation), and learning outcomes (e.g., graded performance). Their model has been extended to associate with antecedents such as self-efficacy (Liem, Lau & Nie, 2008; Pajares, Britner & Valiante, 2000) and outcomes such as task scores (Tanaka, Murakami, Okuno & Yamauchi, 2006; Shih, 2005a). Their works support many important assertions about connections between general motivation, achievement goals, and learning behaviors within different educational contexts.

Revising Elliot and Church’s trichotomous model, Elliot and McGregor (2001) developed an extended framework known as the 2 × 2 achievement goal framework, expressed as mastery-approach, performance-approach, mastery-avoidance, and performance-avoidance goals. They examined the feasibility of the four-goal model and used exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses to find empirical supports for goal differentiation. The four-goal model has also been tested with antecedents such as implicit theories of ability (Cury, Elliot, Fonseca & Moller, 2006) and outcomes such as task scores (Elliot & Murayama, 2008). Conroy, Elliot and Hofer (2003), Fryer and Elliot (2007), and Muis and Edwards (2009) offer evidence in support of the trichotomous/2 × 2 achievement goal model stability and change over time.

However, research on how the 2 × 2 achievement goal model influences academic performance is still deficient in several aspects. First, factor analyses have validated the independence of the four-goal construct and the stability of the 2 × 2 achievement goal model over time in western educational contexts. However, to my knowledge the factor structure and stability of the 2 × 2 achievement goal model have not been confirmed in an eastern/Asian context. Second, research in this area has generally used samples of university students (e.g., Elliot & McGregor, 2001; Elliot & Murayama, 2008; Murayama, Zhou & Nesbit, 2009) and overlooked all other students.

Research Aims

Containing four studies, this dissertation uses Taiwanese elementary and secondary school student samples to examine (a) the first- and second-order factor structure of Elliot and McGregor’s (2001) 2 × 2 achievement goal questionnaires (b) the stability of 2 × 2 achievement goal endorsement in a panel sample, and (c) the predictive utility of the 2 × 2 achievement goal framework.

In studies 1 and 2, factor analytic work was performed to validate the independence of the first- and second-order factorial structure of the 2 × 2 achievement goal construct and to make comparisons with several alternative models. In the current dissertation, I applied the 2 × 2 achievement goal framework to Taiwan educational context. The related issues of Chinese achievement motivation and Confucian goals (Chen, 2005; Hwang, 2008) will be explored later.

In study 3, the stability (change) of the 2 × 2 achievement goal endorsement was examined over a two-year period. Fryer and Elliot (2007) provide empirical evidence in support of trichotomous and 2 × 2 achievement goal model stability in college classroom settings, and they acknowledge that their findings may not be generalizable to students at other grade levels. Following up on their research, study 3 used a panel sample of Taiwanese students to focus on the stability of the 2 × 2 achievement goal model. This study is an initial attempt to analyze pre-university students’ stability of achievement goal endorsement across a whole year in which the fast cumulating knowledge is a hallmark for this learning period. The issue of cross-lag/casual associations between achievement goals and related variables will be the focus of a future investigation.

The focus of study 4 was to test the mediating effects of 2 × 2 achievement goals (with first- and second-order factorial structures) between a motive (self-efficacy in learning Chinese) and a learning outcome (performance in Chinese classes). The purpose was to determine whether this framework could be applied to a sample of Taiwanese students learning Chinese—an important functional domain for these students. The study results contribute to the achievement goal literature and make the 2 × 2 achievement goal framework more generalizable.

Chapter 2 Literature Review

In achievement motivation theory, achievement goals represent subjective purposes (Pintrich, 2000a) or cognitive-dynamic focuses (Elliot & Church 1997) of competence-relevant behaviors for executing tasks. Portrayed as concrete representations of more abstract achievement motivational constructs, achievement goals are conceptualized as midlevel constructs situated between global motivational dispositions (antecedents of achievement goals) and specific behaviors (consequences of achievement goals) (Elliot & Church 1997).

Over the past three decades, approaches to achievement goals have undergone considerable development toward understanding motivated behavior in achievement settings. Using undergraduate samples, Elliot and Church (1997), Elliot and McGregor (2001), and Elliot and Murayama (2008) provide their own evidence for the location of achievement goals between global motivational dispositions such as fear of failure or need for achievement, and specific academic behaviors such as study strategies. Other researchers have identified such factors as classroom social environment (e.g., goal structure emphasized in a class, Wolters, 2004), general motives (e.g., need for achievement, Zusho, Pintrich, & Cortina, 2005) and competency expectancies (e.g., self-efficacy, Liem, Lau, & Nie, 2008; Vrugt, Oort, & Zeeberg, 2002) as direct antecedents of achievement goal adoption, with achievement goals directly and proximally influencing achievement-relevant consequences such as task scores, help-seeking behaviors, and self-regulation strategies, among others (Cury et al., 2006; Elliot & McGregor, 2001; Pintrich, Conley, & Kempler, 2003).

The dissertation attempted to examine the factor structure of the 2 × 2 achievement goal framework (Elliot & McGregor, 2001), the stability of achievement goal endorsement, and an achievement goal model with self-efficacy as an antecedent of achievement goals and Chinese performance as a consequence. In the following section I review related studies on (1) achievement goal theory, (2) the stability of achievement goal endorsement (3) achievement goals and self-efficacy, as well as (4) achievement goals and academic performance.

Achievement goal theory

Dichotomous goal model

Various two goal models have been described and established by achievement goal theorists such as Ames and Archer (1988), Elliott and Dweck (1988), and Nicholls (1984). Ames and Archer (1988) emphasize mastery (i.e., the development of ability through task mastery) and performance goals (i.e., demonstrating ability relative to others). Elliott and Dweck (1988) distinguish between learning and performance goals. They suggest that learning goals, in which one seeks to develop competence, facilitate challenge-seeking and mastery-oriented responses to failure regardless of perceived ability. In contrast, performance goals (in which one seeks to gain favorable judgment for competence or avoid negative judgments) are described as causing challenge-avoidance and learned helplessness. Nicholls (1984) emphasizes task goals (developing ability in reference to one's past performance or knowledge) versus ego goals (demonstrating ability as capacity relative to those of others). Pintrich et al. (2003) suggest that despite differences among the dichotomous goal models behind these various terms, the concepts of mastery and performance have become the most commonly used labels in achievement goal research.

When clarifying and integrating mastery versus performance goal definitions, Pintrich et al.(2003) note that mastery goals emphasize competence, learning, and understanding tasks according to self-referenced standards of improvement, while performance goals focus on demonstrating competence and superiority according to comparative or normative standards. Researchers such as Ames and Archer (1988), Elliott and Dweck (1988), and Nicholls (1984) describe mastery goals in terms of adaptive motivational patterns characterized by persistence in the face of failure, the use of increasingly complex learning strategies, and the pursuit of difficult and challenging tasks. Performance goals, however, are viewed as maladaptive motivational patterns characterized by greater propensity to withdraw from tasks, less interest in difficult tasks, and a tendency to seek less challenging tasks for which there is a greater likelihood of success.

In contrast, Harackiewicz, Barron and Elliot (1998) and Pintrich et al. (2003) do not view mastery and performance goals as opposite ends of a continuum, or as mutually exclusive in terms of their original concept formulations. Both research teams have reported Western-based research findings suggesting that mastery goals and performance goals are either unrelated (Ames & Archer, 1988) or positively correlated (Pintrich & Schunk, 2002) in support of a multiple goal

perspective in which individuals pursue either a single predominant goal or multiple goals.

Similarly, Chan (2008) and Ng (2000) found statistically significant and positive correlations between mastery and performance goals in non-Western samples consisting of Hong Kong students aged 9 to 17 and Mainland Chinese secondary school students. Both researchers suggest that social endeavor in Chinese culture connects the two concepts, since the social goals of bringing honor to one’s family by working or studying hard can shape both mastery and performance goals.

Later, goal theorists (Elliot & Church 1997; Middleton & Midgley, 1997) criticize dichotomous goal perspectives and extend them to a trichotomous achievement goal framework. According to Elliot and Church (1997), it may be unproductive to view all performance goals as maladaptive or in opposition to mastery goals. Middleton and Midgley (1997) also point out that dichotomous goals, mastery and performance, are commonly conceptualized as “approach” motivational tendencies rather than “avoidance” motivational tendencies. These goal theorists, as well as Elliot (1997) and Elliot and Church (1997), note that activities in achievement settings may be either directed toward the attainment of success or the avoidance of failure. When reviewing the histories of approach and avoidance motivation theory, Elliot (1999; 2006) found that approach motivation is behavior directed by positive stimuli, whereas avoidance motivation is regarded as behavior directed by negative stimuli; in both cases the stimuli take the form of objects, events, or possibilities.

Trichotomous goal model

Elliot (1999), Elliot and Church (1997), and Middleton and Midgley (1997) all suggest that performance goals should be divided into two categories—approach performance goals and avoidance performance goals—because they have different effects on outcomes, and because some of them are not less adaptive, as predicted by traditional goal theory. This finding leads Elliot and Church (1997) to propose a trichotomous achievement goal framework, which they tested in the context of college classrooms. Their results provide strong support for the framework with three achievement goals: mastery, performance-approach, and performance-avoidance. Mastery goals are emphasized in the development of competence and task mastery, performance-approach goals are oriented toward the attainment of favorable

judgments of competence, and performance-avoidance goals emphasize the avoidance of unfavorable judgments of competence.

Middleton and Midgley (1997) tested their proposed trichotomous achievement goal model in the context of a middle school mathematics classroom. Their results give support to their model with three goals: task (developing ability), performance-approach (demonstrating ability), and performance-avoidance (avoiding demonstrations of lack of ability). Elliot (1999), Middleton and Midgley (1997), and Pintrich (2000a) are among researchers who believe that compared to dichotomous or oppositional goal categories, trichotomous achievement goal models reflect complex goal constructs more precisely.

2 x 2 achievement goal model

Following the logic of separating approach and avoidance performance goals, Pintrich (2000a) suggests that both versions of mastery goals may exist concurrently. He offers a 2×2 matrix that combines mastery and performance goals with approach and avoidance states. He defines two general aspects of achievement goals: general purpose or reason for engaging in a task, and standards or criteria that individuals use to judge their performance. His list of four goals consists of mastery approach, mastery avoidance, performance approach, and performance avoidance.

Based on Elliot and Church’s (1997) trichotomous achievement goal framework, Elliot and McGregor (2001) developed an advanced revision and extension known as the 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. It consists of two pairs of goals crossing over each other to form four achievement goals: mastery-approach, performance-approach, mastery-avoidance, and performance-avoidance. The feasibility of this model was examined by exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses and found empirical support for the differentiation among the four goals.

Elliot and McGregor (2001) and Elliot and Murayama (2008) posit that achievement goals contain components from two independent competence dimensions. The first, mastery versus performance, refers to competence as defined in terms of the standard used to evaluate it (Dweck, 1986; Elliot & Church, 1997; Nicholls, 1984; Pintrich, 2000a; Pintrich et al., 2003). Mastery-based goals reflect a concern for developing competency and the use of self-referential

improvement standards, while performance-based goals reflect a concern for demonstrating competency in terms of social comparisons. The second dimension, approach versus avoidance, indicates how competence can be valenced. Approach-based goals focus on a movement toward positive stimuli such as competence and success, while avoidance-based goals focus on a movement toward negative stimuli such as incompetence and failure.

As Elliot and Church (1997) and Elliot and McGregor (2001) note in their trichotomous achievement goal and 2 × 2 frameworks, performance-approach goals emphasize demonstrations of skill and the attainment of favorable judgments of competency in relation to others. Performance-avoidance goals focus on avoiding unfavorable judgments of competency and poor performance when compared to others. Mastery-approach goals focus on developing knowledge and skills, as well as enhancing competency and mastery in the form of intrapersonal or task-based criteria. Mastery-avoidance goals, which are the least studied in the achievement goal literature (Elliot, 1999; Pintrich, 2000a), focus on avoiding the loss of skills, abilities, or knowledge (and sometimes on avoiding misunderstanding), thus failing in terms of learning or task mastery. Elliot and McGregor (2001) provide two examples of mastery avoidance goals: perfectionists who try to avoid making any mistakes whatsoever, and individuals in the latter parts of their careers (e.g., athletes and businesspersons) or lives (e.g., the elderly) who focus on not losing their skills, abilities, or memory. Elliot and Murayama (2008) suggest that mastery-avoidance goals emerge from both positive (the need for achievement) and negative sources of motivation (fear of failure), and note that the overall effect of mastery-avoidance goals remains unclear.

Under a multiple goal perspective (e.g., Pintrich, 2000b; Elliot & McGregor, 2001), goal theorists note that people often hold multiple goals simultaneously and so four goals are not independent. They therefore examine the intercorrelations among achievement goals. The empirical evidence on zero-order correlations among the four achievement goals is mixed. Results from two Western-based research findings—using samples of American university students (Elliot & McGregor, 2001) and French secondary school students (Cury et al., 2006)— suggested that mastery-avoidance goals were positively associated with mastery-approach and performance-avoidance goals. They also showed positive associations between performance-avoidance goals and mastery-avoidance and performance-approach goals, but no association between mastery-approach goals and performance-approach goals. Using a sample of

Taiwanese junior high school students, Cherng (2003) found positive associations between performance-approach and performance-avoidance goals, as well as between mastery-avoidance goals and both mastery-approach and performance-approach goals. He failed to find any association between mastery-approach and performance-approach goals and between mastery-avoidance and performance-avoidance goals, but did observe a negative association between mastery-approach and performance-avoidance goals (Cherng, 2003).

Mastery-avoidance goals and their related variables

Mastery-avoidance goals represent a fairly new construct to achievement goal theory. Some researchers (e.g., Ciani & Sheldon, 2010; Sideridis & Mouratidis, 2008) suggest that it may be still a conceptually problematic and somewhat controversial construct. In a sample of university baseball players, Ciani and Sheldon (2010) found mastery-avoidance goals were uncommon, and that high ratings may indicate misinterpretation of the items rather than actual mastery-avoidance goals. Sideridis and Mouratidis (2008) investigated nearly 400 elementary to middle school students selecting their most prominent achievement goal. Only 14 students chose mastery-avoidance goals as their primary goal. These results led Sideridis and Mouratidis (2008) to question the existence of mastery-avoidance goals in young students. The debate is likely because of ambiguity and counterintuitive nature of the mastery-avoidance goals (Elliot & McGregor, 2001).

Pintrich (2000a) defines the mastery-avoidance goals as the reasons for engaging in tasks, as well as the standards or criteria that individuals use to judge their performance. The mastery-avoidance goals focus on avoiding misunderstanding, not learning or mastering tasks, and criteria for not doing things incorrectly relative to a task. Elliot and McGregor (2001) transform the definition of the mastery-avoidance goal to a construct in experiencing competence—defined as the absolute requirement of a task or one's own attainment. Incompetence is the central point of regulatory attention, with the main focus being on avoidance of negative possibilities. Elliot and McGregor (2001) provide examples which individuals are striving to avoid misunderstanding and so failing to learn course materials, striving to not make errors in business transactions, making a free throw in a basketball game, not leaving an incomplete crossword puzzle (i.e. someone dislikes/rejects to play a crossword puzzle because he

believe that he may be incapable of completing crossword puzzle to leave an incomplete one), not forgetting what one has learned (i.e., someone refuse to learn something new because he believes it may interfere/confuse what he has learned), and striving not to lose one's physical or intellectual capabilities (i.e., someone rejects to develop new capabilities because he believes these new capabilities may not performing as well as pervious excellent records and even damage or lose his existing capabilities). Pintrich (2000a) offers a prototypical exemplar, perfectionists who struggle to avoid making any mistakes whatsoever and individuals in the latter part of their careers or lives who focus on not performing worse than in the past, not stagnating, and not losing their skills, abilities, or memory.

While Elliot and McGregor (2001) examined the antecedents and consequences of the mastery-avoidance goals in an attempt to develop empirical profiles, their findings indicated mixed mastery-avoidance goal profiles. The results yielded that the mastery-avoidance goals were grounded in the fear of failure, low self-determination, perceived classroom engagement, entity (instead of incremental) view of competence, parental person-focused negative feedback, parental worry induction, and competence valuation. College students’ endorsement of the mastery-avoidance goals has precedent influences from parental socialization. Comparatively, parental socialization was not related to the endorsement of the mastery-approach goals.

The mastery-avoidance goals are associated with adaptive and maladaptive learning consequences. Elliot and McGregor (2001) show they are positive predictors of disorganized study habits, test anxiety, and subsequent mastery-avoidance, mastery-approach, and performance-approach goals. In a group of Taiwanese junior high school students, Cherng (2003) found that mastery-avoidance goals were positive predictors of self-handicapping, help-seeking, effort, persistence, and math grades. In the sport domain, mastery-avoidance goals have been linked to fear of failure (Conroy & Elliot, 2004), amotivation (Nien & Duda, 2008), and negative reactions to imperfection (Stoeber, Stoll, Pescheck & Otto, 2008). Other studies have identified positive associations between mastery-avoidance goals and perceived competence, enjoyment, effort, and physical activity (Wang, Biddle & Elliot, 2007), as well as perceptions of an enjoyable learning climate (Morris & Kavussanu, 2008).

When the mastery-avoidance goals are compared to three other goals, mastery- avoidance goals differ conceptually from mastery-approach goals regarding the valence of competence, from performance-avoidance goals regarding the definition of competence, and from

performance-approach goals regarding both the definition and valence of competence (Elliot & McGregor, 2001). Empirical findings of Elliot and McGregor and Cherng (2003) revealed that mastery-avoidance goals were more negative than the mastery-approach goals, and more positive than the performance-avoidance goals. Mastery-avoidance and performance-avoidance goals have very similar antecedent profiles in terms of non-optimal variables—for example, fear of failure (Conroy & Elliot, 2004) and amotivation (Nien & Duda, 2008). Unlike performance-avoidance goals, and similar to mastery-approach goals, mastery-avoidance goals emerge from individual perceptions that a class (or some other scenario) is engaging and interesting (Elliot & McGregor, 2001). The mastery-avoidance goals share some negative characteristics with the performance-avoidance goals, but they differ from the performance-avoidance goals in that they are neither negative predictors of performance achievement (Cherng, 2003; Elliot & McGregor, 2001) nor positive predictors of health center utilization (Elliot & McGregor, 2001).

Elliot and McGregor (2001) attribute the mixed conceptual profiles of the mastery-avoidance goals to the combination of optimal (mastery) and non-optimal components (avoidance). Mastery has been always viewed as adaptive by educational psychologists (Dweck, 1986; Pintrich, 2000a; Pintrich et al., 2003) while avoidance maladaptive and how do we categorize the combination? Elliot and McGregor (2001) suggest that the adoption of these goals is most likely among individuals with non-optimal motivational dispositions in optimally structured achievement settings that challenge pursuit and foster intrinsic interest. They also suggest that empirical predictions regarding the mastery-avoidance goal antecedents and consequences are difficult to generate for two reasons. First, the mastery component likely results from optimal antecedents and the desire to foster positive consequences (similar to the mastery-approach goals), but the avoidance component likely results from non-optimal antecedents and causes negative consequences (similar to the performance-avoidance goals). Second, it is hard to determine the relative strengths of the two components when combined, or the accurate manner in which each component functions in combination with the other.

Finally, optimal motivation and performance may require combinational types of goals. Empirical evidence has indicated that pursuing one type of goal does not necessarily exclude pursuit of the other (Ames & Archer, 1988; Bouffard-Bouchard, Boisvert, Vezeau, & Larouche, 1995; Harackiewicz et al., 1997; Middleton & Midgley, 1997). Based on a multiple goal

perspective Shih (2005b) found that a group of Taiwanese elementary students who maintained high-mastery/high-performance-approach goals showed more adaptive learning patterns than students who maintained other types of multiple goals.

Measurement for the 2 x 2 achievement goals

Elliot and McGregor (2001) developed an achievement goal questionnaire (AGQ) to measure four goals in the 2 × 2 achievement goal framework. Item pools for mastery-approach goals, performance-approach goals, and performance-avoidance goals were chosen from their previous instruments (Elliot & Church, 1997); new items were designed for mastery-avoidance goals. Three items were generated to represent each of the four achievement goal constructs. In the questionnaires, 3 items in each subscale assessed mastery–approach goals (e.g., “It is important for me to understand the content of this course as thoroughly as possible.”), mastery–avoidance goals (e.g., “I am often concerned that I may not learn all that there is to learn in this class.”), performance–approach goals (e.g., “It is important for me to do well compared to others in this class.”), and performance–avoidance goals (e.g., “My goal in this class is to avoid performing poorly.”). Participants responded to the extent which they believed ranged from 1 (not at all true of me) to 7 (very true of me). AGQ was tested in introductory-level undergraduates’ psychology classes in series of studies. The results of exploratory factor analysis (EFA), confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) empirically supported the separable and internally consistent achievement goal constructs; Cronbach alpha coefficients evidenced good reliability. AGQ was translated into Chinese version and used as the main measurement tool in my dissertation.

Stability of achievement goal endorsement

Do learners endorse the same goals or do they change goal adoption across time? In a review of theoretical perspectives regarding stability in achievement goal adoption over time, Fryer and Elliot (2007) note that achievement goals emerge from stable factors (e.g., personality traits such as achievement motives and temperaments) and remain grounded in these factors throughout goal pursuit and regulation processes. In addition, they claim that goal stability lies in the nature of the goal construct. When individuals face achievement tasks, they adopt goals and

develop cognitive frameworks for interpreting those tasks, experience task involvement, and react to competence-relevant information (Ames, 1992; Dweck, 1986). This framework can result in directional or biased perceptual–cognitive processes that foster subsequent goal seeking behaviors in a self-fulfilling way (Elliot & Harackiewicz, 1996).

Only a few articles focusing on this critical issue of goal stability and change have been available. Of these, some have addressed change in achievement goals across a sequence of similar tasks during several weeks of college classes (Senko & Harackiewicz, 2005; Fryer & Elliot, 2007); some have examined shifts in goal endorsement for school within a school year (e.g., Bong, 2005; Seifert, 1996); still others have examined shifts in goal endorsement for school across the elementary to middle school transition (e.g., Anderman & Midgley, 1997). To my knowledge, there is still short of research about stability of achievement goal endorsement in Asian population.

My question of whether achievement goal endorsement changes in learning Chinese across secondary school year or whether it remains stable can be answered in several ways, depending on what type of change (or stability) one focuses on. Typical parameters are means, variances, and covariances, all of which may be subject to remain stable over time. There are at least three types of stability that can be examined in sample levels using longitudinal panel data: structural stability (or change), differential stability, and mean-level stability. Structural stability refers to the constancy of covariances among a set of constructs across time. In my case, structural change addresses the issue of changing associations among four achievement goals over time. However, this requires that goal constructs are measured in the same way on two measurement occasions. In order to guarantee this, several degrees of measurement invariance must be examined (Meredith, 1993). Configural invariance demands that the number of factors and according significant and non-significant loadings are equal over time, which guarantees that the dimensionality of the goals is identical. For weak measurement invariance (MI) to hold, factor loadings in two measurement occasions must be equal. If so, factor variances and covariances can be compared. If in addition, the intercepts of the observed indicators are equal, strong MI is given, which allows comparing factor means. Moreover, if residual variances are also equal, strict MI holds, implying that all interindividual differences in observed variables stem from the underlying factors (Bollen, 1989; Meredith & Horn, 2001).

achievement goal MI within several weeks. They empirically tested fit indexes in a series of four nested models by increasing constraints: configural invariance (constraints equal only on the factor variances), weak MI (additional constraints equal on the item–factor regression coefficients), strong MI (additional constraints equal on the item intercepts), and strict MI (additional constraints on uniquenesses across measurement occasions). Fit indexes were compared between models, and a significant decrease in model fit suggests that the model with fewer constraints should be chosen (Conroy et al., 2003). Strong MI is considered to be sufficient for the comparison of scores across time points (Sayer & Cumsille, 2001; Zimprich & Mascherek, 2010). Fryer and Elliot (2007) found no significant fits decrease when the constraints were added to form the weak and the strong MIs. However, there was a significant fit reduction when the constraints added to form the strict MI. In their case, changes in achievement goals over time can be explained as true change instead of measurement errors because the strong MI was ensured.

Differential stability (or change) concerns the preservation of an individual’s relative placement (rank order) within a group across time. It is the consistency of individual differences in terms of a particular attribute amongst each other’s attributes in a group of people over time. Different people may change to a different degree across time. Achievement goal researchers have examined the differential stability with the Pearson product–moment correlation (e.g., Fryer & Elliot, 2007; Anderman & Midgley, 1997). Fryer and Elliot (2007) found the intercorrelations among four goals are from .57 to .75. Correlation coefficients reported in their studies were significant and positive with moderate to high magnitudes. In other words, moderate-to-high correlations suggest consistency in individual-related position (goal endorsement) over a relative short period of learning time when college students facing a sequence of similar tasks.

Mean-level stability (or change) describes the extent to which the average amount of a construct changes over time within a sample (Fryer & Elliot, 2007). It refers to sample level change in achievement goal endorsement for the two time points and is typically examined with a paired-samples t test. This index provides information regarding the absolute amount of change in a construct. Fryer and Elliot (2007) provided evidence of mean level stability for the performance–approach and the mastery–avoidance goals but significant shifts for the mastery–approach and the performance–avoidance goals across three time points.

Self-efficacy and achievement goals

Bandura (1986) defines self-efficacy as “people’s judgments of their capabilities to organize and execute courses of action required to attain designated types of performances” (p. 391). In another article he asserts that

self-efficacy contributes to motivation in several ways: determining the goals people set for themselves, how long they persevere in the face of difficulties, and their resilience to failures. Self-efficacy operates personal cognized goals which motivate and guide the present behaviors. (Bandura 1993, p. 131)

Pintrich and DeGroot (1990) and Schunk (1981) postulate that self-efficacy has motivational effects that are especially germane to student achievement. Social cognitive theorists such as Bandura (1986) and Shunk (1990) claim that students who have low self-efficacy for learning a certain subject are more likely to form avoidance goals and make limited effort, while those who perceive themselves as efficacious tend to form approach goals and participate in tasks at which they can succeed. In accordance with this assertion, Elliot’s (1999) hierarchical model of achievement motivation suggests that self- and competence-based variables such as self-efficacy exert a direct effect on achievement goals, which in turn serve as a proximal precursor to achievement-related processes and outcomes. With regard to associations between dichotomous achievement goals and self-efficacy, most findings indicate that mastery (learning) goals are positively associated with self-efficacy (see, for example, Bell & Kozlowski, 2002; Kaplan & Midgley, 1999; Middleton & Midgley, 1997). However, results for any association between performance goals and self-efficacy are mixed. Some findings indicated that performance goals were negatively associated with self-efficacy (Bell & Kozlowski, 2002; Kaplan, & Midgley, 1999; Middleton & Midgley, 1997), while others indicated positive relationships (Daniels et al., 2008; Wolters, Yu & Pintrich, 1996).

Regarding the effects of self-efficacy on trichotomous achievement goals, Pajares et al. (2000) provides empirical evidence from elementary, middle school, and high school writing and science courses with students raging from 9 to 17 year-old. They found a strong positive association between self-efficacy and mastery goals across three school levels, a weak positive association between self-efficacy and performance-approach goals at the middle and high school

levels, and a negative association between self-efficacy and performance-avoidance goals at all levels. A consistent result have been reported for samples of Singaporean adolescents (Liem et al., 2008), Australian high school students (Smith, Sinclair & Chapman, 2002), Korean middle/senior high school students (Bong, 2001), and American junior high school students (Wolters, 2004). To my knowledge, little research have examined the relationship between self-efficacy and 2 × 2 achievement goals. Accordingly, one of my aims was to examine relationships between self-efficacy and 2×2 achievement goals.

Achievement goals and academic performance

In terms of the effects of dichotomous achievement goals on outcome performance, research results are inconsistent. Bell and Kozlowski (2002) found that for American university students, mastery/learning goals were positive predictors and performance goals were negative predictors of course performance. Daniels et al. (2008) found that both mastery goals and performance goals were positively correlated with final grades in Canadian university students. Kozlowski et al. (2001), who observed American undergraduate psychology course students, suggest that performance goals and mastery goals are not related to outcome performance.

Regarding the effects of trichotomous achievement goals on academic performance, several research groups have found that the performance-approach goals are positive predictors of undergraduate course grades and the performance-avoidance goals are negative predictors; null results were observed for mastery goals (Elliot & Church, 1997; Elliot, McGregor & Gable,1999; Harackiewicz et al., 1998; Zusho et al., 2005). Observing Hong Kong secondary school students, Chan and Lai (2007) found that performance-approach goals were positive predictors of grades, while performance-avoidance goals were negative predictors; null results were observed for mastery goals. Although Chan and Lai’s data are in agreement with findings for undergraduates, other data for various samples of pre-university students are mixed. Lopez (1999) investigated middle school students in South America, and found that three goals were not significant predictors of grades. Tanaka et al. (2006) examined associations between trichotomous achievement goals and task performance for a group of Japanese junior high school students. Mastery goals were the only possible predictors of task scores.

in academic subjects for a group of gifted Hong Kong students ranging from ages 9 to 17. Using a sample of American junior high school students, Wolters (2004) found that mastery goals and the performance-approach goals were positively associated with math course grades, and performance-avoidance goals were negatively associated. Shih (2005a) found that mastery goals and performance-approach goals exerted positive effects on academic performance for Taiwanese sixth grade students, but performance-avoidance goals exerted no effects.

Regarding effects of 2 × 2 achievement goals on academic performance, Elliot and McGregor (2001) and Elliot and Murayama (2008) observed American undergraduates and found that performance-approach goals were positive predictors of course grades and performance-avoidance goals were negative predictors; null results were observed for mastery-approach and mastery-avoidance goals. For a sample of French secondary school students, Cury et al. (2006) found that mastery-approach goals and performance-approach goals were positively correlated with math grades, and performance-avoidance goals were negatively correlated with math grades; no significant correlation was noted for mastery-avoidance goals. Kaplan, Lichtinger and Gorodetsky (2009) reported a positive association between mastery-approach goals and writing achievement among a group of Israeli ninth graders (most 14 years of age). In sum, although past research on trichotomous achievement goals suggest that performance-approach goals are positive predictors and performance-avoidance goals are negative predictors of undergraduate course grades, results for pre-university students are mixed; in both cases null results have been observed for mastery goals. Thus, patterns regarding the effects of 2 × 2 achievement goals on academic performance are yet unclear.

Culture effects on achievement goals and academic performance

Lu, et al. (2001) and Hwang (2008) suggest that achievement goals have cultural roots—for example, Confucian principles in Chinese populations. Hwang observes that achievement motivation among Taiwanese students is significantly influenced by Confucian cultural traditions: adolescents in Taiwan are expected to study hard to develop knowledge and skills as a means of fulfilling social and family obligations (see also Shih, 2005b). Hwang also notes that hard work and good performance are accepted indicators of fulfilled filial responsibility in Confucian terms, which also emphasizes a personal obligation to make an effort toward success. Thus, Taiwanese

students are socialized to value effort—an “effort-as-virtue” model—and to believe that hard work facilitates attainment (Chen, 2005; Hwang, 2008; Shih, 2005b).

Taiwanese students are also taught that their competence will improve as long as they study hard enough (Hwang, 2008). Accordingly, they may view incremental competence in academic tasks in terms of mastery goals, and positive social evaluation in terms of performance goals, and therefore adopt mastery-oriented behaviors. In contrast, goal theorists such as Harackiewicz and Elliot (1998) and Kaplan and Middleton (2002) note that the performance-approach goal endorsement is generally reflected in competitive learning environments and Taiwanese schools are notorious for a highly competitive atmosphere resulting from the national system of entrance examinations (Shih, 2005a; Yang, 1988). Accordingly, many Taiwanese students feel compelled to pursue performance-approach goals and to struggle for achievement relative to others. According to Confucian thought, learners must try their best to achieve mastery through persistence and comprehensive knowledge of a subject, with the hope of eventually demonstrating performance in a manner that brings them wealth (Ho, 1994; Xiang, Lee & Solmon, 1997; Yang, 1988).

This competitive context, influenced by cultural values, likely supports the development of an achievement motivation based on simultaneously studying hard for higher achievement (task mastery) and outperforming others (a performance approach) (Shih & Alexander, 2000). Shih (2005a) reported that Taiwanese sixth graders maintained performance-approach and mastery goals concurrently, and also reported her observations of more adaptive learning patterns relative to students with other goal profiles. In a sample of Taiwan junior high school students, Cherng (2003) found that mastery-approach, mastery-avoidance, and performance-approach goals were all positive predictors of math grades, and that the performance-avoidance goals were negative predictors—evidence that the mastery-approach and performance-approach goals have positive effects on grades (Barron & Harackiewicz, 2001; Pintrich, 2000a; Shih, 2005a). Among trichotomous goals, mastery goals are the most adaptive for evoking beneficial learning patterns (Shih, 2005a). In accordance with mastery goals, Shih also reported that the performance-approach goals positively predicted Taiwanese students’ strategies and intrinsic motivation, and negatively predicted test anxiety. She attributes the positive effects of the performance-approach goals to Taiwanese students’ motivation and strategy, both of which are good matches with goals associated with an intensely competitive learning environment

(Harackiewicz & Elliot, 1998). The pursuit of the performance-approach goals in such performance-oriented and competitive context likely leads to adaptive learning behaviors. Shih’s (2005a) findings imply that stress on competition and/or performance does not necessarily undermine learning, as long as students are oriented to the approach and not to avoidance.

Overview of the present research and hypotheses

This dissertation is a collection of five studies I worked on between 2009 and 2010.

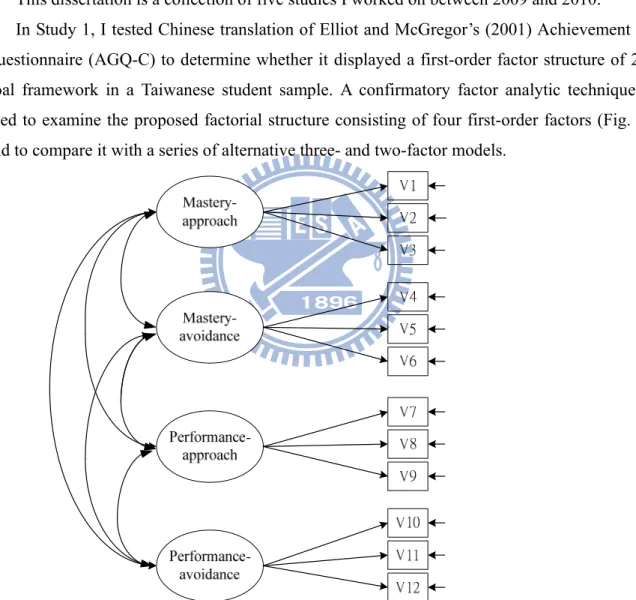

In Study 1, I tested Chinese translation of Elliot and McGregor’s (2001) Achievement Goal Questionnaire (AGQ-C) to determine whether it displayed a first-order factor structure of 2 × 2 goal framework in a Taiwanese student sample. A confirmatory factor analytic technique was used to examine the proposed factorial structure consisting of four first-order factors (Fig. 2-1), and to compare it with a series of alternative three- and two-factor models.

Figure 2-1 The hypothetical measurement model of first-order achievement goal structure.

reasonable to expect that none of the alternative models would provide a better fit. In addition, maximum-likelihood ratio test results would indicate that the hypothetical first-order model provide a good fit—better than the alternative models.

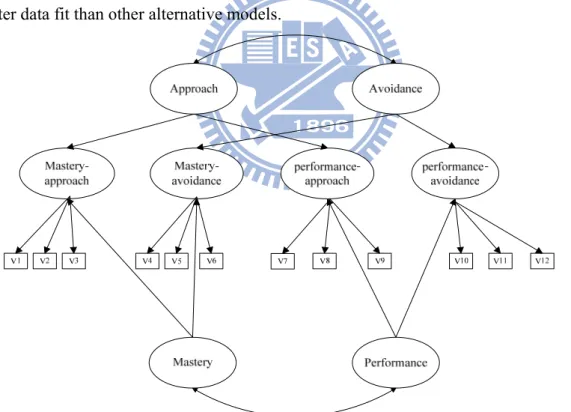

In Study 2, I used a Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) process to analyze, namely, the dimensional structure. First-order latent variables in this model were four achievement goals (from mastery-approach goals to performance-avoidance goals), and second-order latent variables were four factors associated with two competence dimensions (from mastery-based goals to avoidance-based goals) (Fig. 2-2). While factors within each dimension (e.g. approach versus avoidance) were assumed as correlated, factors across dimensions (e.g., approach versus mastery) were assumed as not being correlated. The hypothetical model was compared to alternative second-order models. As a new application of the AGQ-C, it was predicted that maximum-likelihood ratio tests would reveal that the hypothetical second-order model provided a better data fit than other alternative models.

Figure 2-2 The hypothetical path diagram of second-order measurement model of achievement goal dimensional structure.

In Study 3, I examined the stability of the 2 × 2 achievement goal endorsement in a Taiwanese student panel sample. I examined the stability of achievement goal endorsement with three indexes, structural stability, differential stability and mean-level stability. It was expected the AGQ-C could demonstrate measurement invariance, at least to hold strong measurement invariance and the structural stability of achievement goal could be confirmed. No significant decreases in model-fits when constraints were gradually added to various invariance models. Moderate to high correlations were expected to indicate the differential stability over time. It was also expected that the mean-level stability could be confirmed so that paired t tests would show no significant differences of four achievement goals measured over two time points.

The predictive validity of the AGQ-C was the major concern in study 4, with performance of Chinese language arts as the consequence of 2 × 2 achievement goals. This decision was made because Chinese is the official medium of instruction in Taiwan, as well as the country’s official language. Taiwanese students are repeatedly told that Chinese language mastery is important in itself, and has instrumental value for passing senior high school and university entrance exams (short-term goals) and for getting good jobs and enhancing social status (long-term goals). Chinese is the only subject course taken by every Taiwanese student from primary through high school. Taiwanese students spend more than four hours weekly on Chinese reading, essay writing, grammar, rhetorical, and other skills in preparation for entrance exams. Students have various learning experiences with this subject and so they could have formed their achievement goals.

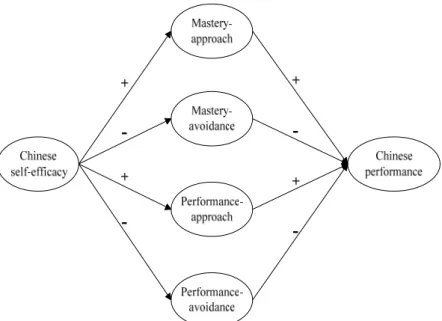

In Study 4, I analyzed the mediating effects of achievement goals between self-efficacy and Chinese performance. Specifically, I investigated a structural model based on first-order achievement goals, and assumed that the four goals acting as mediators between Chinese self-efficacy and Chinese performance (Fig. 2-3). It was expected that Chinese self-efficacy would have positive effects both on the mastery-approach goals and the performance-approach goals, which in turn would be positive predictors of Chinese performance. Chinese self-efficacy would have negative effects on the performance-avoidance goals that in turn would be negative predictors of Chinese performance. Considering the lack of research on the mastery-avoidance goals in Asian samples, I established a tentative hypothesis that Chinese self-efficacy would negatively affect the mastery-avoidance goals, which in turn would be negative predictors of Chinese performance.

Figure 2-3 The hypothetical path diagram of antecedents and outcomes of four achievement goals (with factorial structure).

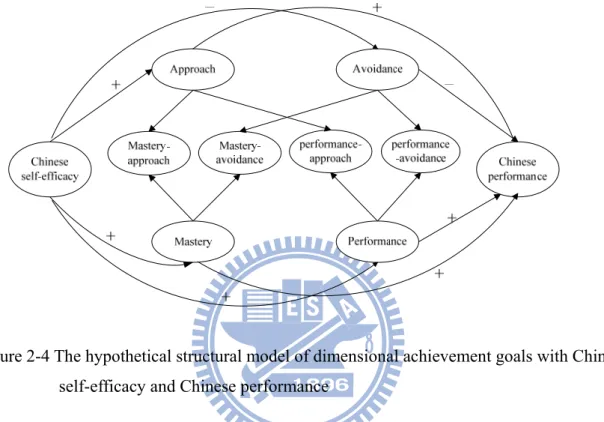

Also in Study 4, I investigated a structural model based on second-order achievement goals, predicting that four factors associated with valence and definition dimensions were mediators between Chinese self-efficacy and Chinese performance (Fig. 2-4). Elliot (2006) provides an overview of approach-avoidance distinctions based on a collection of psychology studies. He notes that positively evaluated stimuli are inherently correlated with an approach orientation that moves the direction of behavior toward it. In contrast, negatively evaluated stimuli are inherently correlated with an avoidance orientation that moves the direction of behavior away from it. It was therefore expected that Chinese self-efficacy would have a positive effect on the approach factor but a negative effect on the avoidance factor. Consequently, the approach factor would have a positive effect on Chinese performance, while the avoidance factor would have a negative effect on Chinese performance. In addition, empirical findings on the association between performance/mastery goals and self-efficacy have been mixed. As stated above, mastery goals focus on the development of ability through task mastery, while performance goals focus on demonstration of ability relative to others. However, Shih (2005a) and Shih and Alexander (2000) found that Taiwanese students are encouraged to endorse performance and mastery goals simultaneously, and that the two goals both facilitate academic performance. It was therefore predicted that Chinese self-efficacy would have positive effects on mastery and performance

factors, and that mastery factor and performance factors would have positive effects on Chinese performance.

Figure 2-4 The hypothetical structural model of dimensional achievement goals with Chinese self-efficacy and Chinese performance

Chapter 3 Study 1: The first-order factorial structure of the 2 × 2 achievement

goal framework

The aim of study 1 was to examine the first-order factor structure of the Chinese translation of Elliot and McGregor’s (2001) Achievement goal questionnaires (AGQ-C). Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) procedures were used to validate the independence of the four achievement goals; CFA was also used to test the fit of alternative three- and two-factor models and to compare the fit of the hypothesized model to these alternatives.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were drawn from the list of respondents to a 2007 national adolescent survey funded by the Taiwan National Academy for Educational Research. Survey questions were designed to collect demographic, exam performance, and physical and mental development data. Regional clusters were classified according to Taiwan official territorial divisions (northwest, midwest, southwest, and east/islands). The numbers and percentages of participating schools and students in each region were determined according to 2006 educational statistics published by the ROC Ministry of Education (n.d.). Schools were randomly selected in each region, and one class was randomly selected from each school. The sample consisted of 3,137 students (934 fifth graders, 29.8%; 1,074 seventh graders, 34.2%; and 1,129 tenth graders, 36%) who completed questionnaires assessing their achievement goals.

Instruments

Achievement Goals. Elliot and McGregor’s (2001) AGQ was translated into Chinese

(AGQ-C). Each achievement goal was comprised of three items (for a total of 12 items) with responses given along a 5-point checklist (1 = “not at all true of me,” 5 = “very true of me”). Instead of using the 7-point Likert scale in the original questionnaire; all items in the AGQ-C are on a 5-point Likert scale because students who participated in my study were younger than the

sample in Elliot’s study. For example, the statement, “I want to learn as much as possible in my Chinese language class,” was used to measure mastery-approach goals. I used, “In my Chinese course, it is important for me to do better than other students,” to measure performance-approach goals, and “I worry that I may not learn all that I possibly can in my Chinese language class” for mastery-avoidance goals. Finally, “My goal in Chinese classes is to avoid performing poorly” was used to measure performance-avoidance goals.

An educational measurement expert was invited to back-translate AGQ-C. The AGQ, the back translation, and AGQ-C were compared. Geisinger (1994) noted that the issue of cultural adaptation may make it difficult to directly translate and use items from some measures. Considering cultural sensitivities, the current study adopt wordings related to Chinese common phrases instead of translating items linguistically. It is believed that these procedures may improve the validation of AGQ-C. Reliability coefficients for the four achievement goal subscales were .85, .89, .85, and .81, respectively.

Results

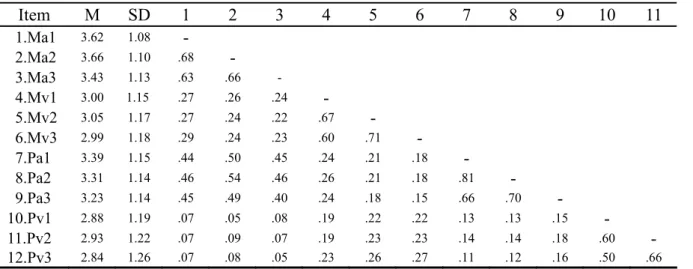

The descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of 12 items for four achievement goals were shown in Table 3-1. The descriptive statistics, alpha coefficients of and zero order correlations of achievement goals indicators were shown in Table 3-2.

Table 3-1 Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of 12 items for four goals. (N = 3137)

Item M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1.Ma1 3.62 1.08 - 2.Ma2 3.66 1.10 .68 - 3.Ma3 3.43 1.13 .63 .66 - 4.Mv1 3.00 1.15 .27 .26 .24 - 5.Mv2 3.05 1.17 .27 .24 .22 .67 - 6.Mv3 2.99 1.18 .29 .24 .23 .60 .71 - 7.Pa1 3.39 1.15 .44 .50 .45 .24 .21 .18 - 8.Pa2 3.31 1.14 .46 .54 .46 .26 .21 .18 .81 - 9.Pa3 3.23 1.14 .45 .49 .40 .24 .18 .15 .66 .70 - 10.Pv1 2.88 1.19 .07 .05 .08 .19 .22 .22 .13 .13 .15 - 11.Pv2 2.93 1.22 .07 .09 .07 .19 .23 .23 .14 .14 .18 .60 - 12.Pv3 2.84 1.26 .07 .08 .05 .23 .26 .27 .11 .12 .16 .50 .66

Ma1-3 = Mastery-approach goal items; Mv1-3= Mastery-avoidance goal items; Pa1-3 =Performance-approach goal items; Pv1-3 =Performance-avoidance goal items

Table 3-2 Descriptive statistics, alpha coefficients of and zero order correlations of achievement goal indicators (N = 3137) M SD 1 2 3 4 1. Mastery-approach goals 3.57 .97 (.85) 2. Mastery-avoidance goals 3.01 1.03 .33 (.85) 3. Performance-approach goals 3.31 1.03 .59 .26 (.89) 4. Performance-avoidance goals 2.88 1.04 .09 .30 .18 (.81)

Note.All correlations were statistically significant at <.01.

( ) : alpha coefficients of internal consistency

Factorial structure of achievement goals: The first-order factor structure

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFAs) were conducted to the AGQ-C items using LISREL 8.80 according to procedures described by Jöreskog and Sörbom (1993). Five fit indices were used to assess the overall fit of the model: the chi-square statistics, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), the incremental fit index (IFI), and the Akaike information criterion (AIC). The chi-square statistic provides an asymptotically valid significance test of model fit. An RMSEA of .08 or less is considered to be a reasonable fit (Steiger, 1989; Browne & Mels, 1990). The values of the CFI range from 0 to 1 with values greater than .95 indicating an acceptable model fit (Bentler, 1990; Hu & Bentler, 1995). The value of the IFI ranges from 0 to 1 with values greater than .90 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993). When multiple models were compared, the value of AIC was the lower the better.

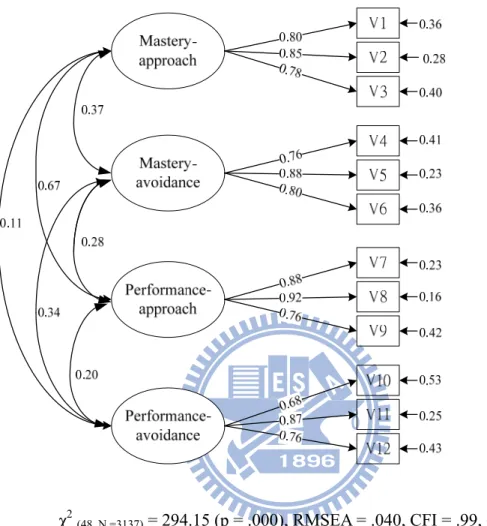

The first CFA examined the hypothetical model with 12 items loaded on their respective first-order latent factors (Fig. 3-1): mastery-approach, mastery-avoidance, performance-approach, and performance-avoidance goals. The results strongly supported the first-order hypothetical model (Figure 3-1) in which all factor loadings were pretty high (ranging from .68 to .92, p < .01)

and each fit statistic met the criteria for a good fitting model: χ2

(48, N=3137) = 294.15 (p = .000);

distinctly perceived by Taiwanese students while learning Chinese.

χ2

(48, N =3137) = 294.15 (p = .000), RMSEA = .040, CFI = .99, GFI =.97

Figure 3-1 The first-order measurement model of achievement goal structure. Estimates are standardized.

Note. All coefficients are significant (p < .01). Error variables are not represented in order to simplify the presentation. V1 to V12 represent the individual items of the scale.

Model comparison

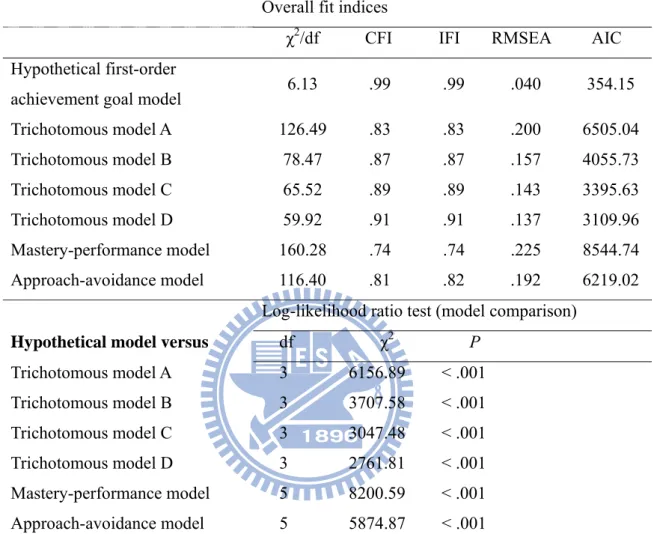

Additional CFAs examined the fit of alternative models (all are of first-order factor structure) and compared the fit indices of the hypothesized and alternative models. Six alternative models were tested: (a) trichotomous model A in which the performance-approach and performance-avoidance items load on their respective latent variables, and the mastery-approach and mastery-avoidance items load together on a third latent variable; (b) trichotomous Model B, in which the mastery-approach and mastery-avoidance items load on their respective latent variables, and the performance-approach and performance-avoidance items load together on the third latent variable; (c) trichotomous Model C in which the mastery-approach and performance-approach items load on their respective latent variables, and the mastery-avoidance and performance avoidance items load together on a third latent variable; (d) trichotomous Model D in which the performance-avoidance and mastery-avoidance items load on their respective latent variables, and the performance-approach and mastery-approach items load together on a third latent variable; (e) a mastery-performance model in which the mastery-approach and mastery-avoidance items load together on one latent variable, and the performance-approach and performance-avoidance items load together on another; and (f) an approach-avoidance model in which the mastery-approach and performance-approach items load together on one latent variable, and the mastery-avoidance and performance-avoidance items load together on another.

As displayed in Table 3-3, the results of these analyses indicated that none of the alternative dichotomous or trichotomous models provided a good fit to the data, and the hypothetical model displayed a far better fit than any of the alternative models. The results were accorded with findings of Elliot and McGregor (2001) and Elliot and Murayama (2008).