Abstract

Background: Fatigue is a common symptom in patients with heart failure that is easy to

ignore. In addition, fatigue may affect patients' physical function and psychosocial conditions that can impair their quality of life. An effective nursing care program is required to alleviate patients’ fatigue and improve patients’ quality of life.

Aim: To investigate the effects of a supportive educational nursing care program on fatigue

and quality of life in patients with heart failure.

Methods: A randomized controlled trial design was used. Ninety-two patients with heart

failure were randomly assigned to an intervention group (n = 47) or a control group (n = 45). The patients in the intervention group participated in 12 weeks of supportive educational nursing care program including fatigue assessment, education, coaching self-care, and evaluation. The intervention was conducted by a cardiac nurse during four face-to-face interviews and three follow-up telephone interviews. Fatigue and quality of life were assessed at the baseline and 4weeks, 8 weeks, and 12 weeks after enrollment in both groups.

Results: The participants in the intervention group exhibited a significant decrease in the

level of fatigue after 12 weeks, whereas those in the control group exhibited no significant changes. Compared with the control group, the intervention group exhibited a significantly greater decrease in the level of fatigue and significantly greater improvement in quality of life after 12 weeks of intervention.

Conclusions: The supportive educational nursing care program was recommended to

alleviate fatigue and improve quality of life in patients with heart failure.

Introduction

Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms experienced by 50%–98% of patients with heart failure.1-3 Fatigue is defined as a subjective, unpleasant feeling that involves the complex interaction of biological processes, psychosocial phenomena, and behavioral manifestations.4, 5 Patients with fatigue experience an overwhelming sustained sense of exhaustion and

decreased capacity to engage in physical and mental activity that is not relieved by rest.4-6 Fatigue was associated with poor functional ability and quality of life, and it could predict a worsening prognosis and increased mortality in patients with heart failure.7, 8 Therefore, knowledge regarding physical and psychosocial mechanisms of fatigue is important for management of fatigue in patients with heart failure.

Research has indicated that fatigue is positively correlated with physical factors including increased disease severity, comorbidity, use of medications, symptoms, sleep disturbance, poor nutrition, and poor functional capacity in patients with heart failure.1, 3, 9 In addition, higher fatigue was also related to psychosocial factors such as higher depression and lower emotional support.9, 10 Therefore, fatigue is multifactorial and may limit patients’ performance of daily activities and self-care that can affect patients' psychological and social conditions, impairing their quality of life.2, 3, 9

Quality of life is a subjective measure of the positive and negative aspects of personal life experience and is a multidimensional concept that includes physical health, psychological health, social relationship, and environmental domains.11, 12 Patients with heart failure were observed to have a lower quality of life, which can predict patient mortality and morbidity outcomes.13, 14 Studies have reported that quality of life is related to age, gender, economic status, disease severity, comorbidity, physical symptoms, medication use, anxiety, and depression in patients with heart failure.15-17 Thus, the nursing care of patients with heart failure should emphasize the comprehensive assessment of patient demographic and clinical

characteristics and management of physical symptoms such as fatigue and mental status to improve the quality of life of these patients.

Informational and emotional support can be provided through supportive care to improve patients’ symptom management and quality of life.18, 19 Ream et al.20 reported that a supportive intervention alleviated fatigue and depression and improved the ability to cope with illness in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy. This supportive intervention consists of four components: assessment and monitoring of fatigue; education on fatigue; coaching in self-care; and provision of emotional support. The supportive intervention could provide both informational and emotional support to the patients. This intervention educated patients how to manage fatigue through energy conservation and management and to optimize activity and functioning. Furthermore, provision of emotional support allowed patients to explore the meaning of fatigue in the lives, their hopes, and future goals20. Therefore, this supportive intervention can reduce fatigue through achieving an optimal balance between restorative rest and restorative energy that can improve patients' physical function, psychosocial conditions, and their quality of life.

In addition, previous studies have only reported the effects of interventions such as muscle relaxation and exercise training on alleviating fatigue in cardiac patients.21, 22

However, little is known regarding the effects of supportive nursing care on fatigue symptoms and quality of life in patients with heart failure. Therefore, this study investigated the effects of a supportive educational nursing care program on fatigue and quality of life in patients with heart failure.

The following hypotheses were tested in this study: (1) Patients who receive 3 months of a supportive educational nursing care (the intervention group) will have significantly greater improvement in the level of fatigue than do patients who receive routine nursing care (the control group). (2) Patients who receive 3 months of a supportive educational nursing care

(the intervention group) will have significantly greater improvement in quality of life than do patients who receive routine nursing care (the control group).

Methods

Study design

This study was a parallel-design randomized controlled trial with a longitudinal research design. Data were collected at baseline, 4 weeks, 8 weeks and 12 weeks after patient’s enrollment in this study for the intervention and control group.

Participants, recruitment and randomization

The participants were recruited from the cardiovascular ward and outpatient department of a medical center in Taichung City, Taiwan by using convenience sampling. The inclusion criteria for participants were (1) a diagnosis of heart failure with the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification I-IV established by a cardiologist; (2) clear consciousness and the ability to communicate in Mandarin or Taiwanese; and (3) agreement to participate in the study. People who were (1) bedridden and dependent on others or (2) diagnosed with depression or mental illness were excluded. We recruited patients with NYHA functional class I in order to prevent occurrence of fatigue and disease progress. Patients who were diagnosed with depression or mental illness were excluded, because depression patients might have higher fatigue which could overestimate the levels of fatigue. However, no patients were diagnosed with depression in this study.

During the study period from June to November, 2012, a total of 96 patients were recruited by the researcher according to the selection criteria. Four of these patients were not able to participate because they experienced difficulty in communicating or refused to complete the entire questionnaire. Thus, 92 participants were randomly assigned to either the intervention group (n = 47) or the control group (n = 45). Each participant was assigned one

number from 1 to 92. The sequence of intervention and control group was generated by a block randomization method in blocks of 4 with a 1:1 ratio. The researcher chooses the blocks randomly to determine the patient’s assignment into the groups. The allocation was kept in sequentially numbered, opaque envelopes. A total of 75 participants completed the entire 12-week study, yielding an attrition rate of 18.4%. Thirty-eight participants in the intervention group received a 12-week supportive educational nursing care program provided by the researcher, whereas 37 participants in the control group received routine nursing care (Fig. 1).

The sample size estimation was based on a study of Wang et al.23 with an effect size of 0.58. A minimum required total sample size of 96 was required to attain a 0.8 power level for a two-tailed t test study with an effect size of 0.58 and an alpha of 0.05.24

Procedures

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the institutional review board of the study hospital (CE12067). A pilot study was conducted before the formal study to test the procedures. The researcher explained the study purpose, methods, procedure, and the right of free withdrawal to all participants and obtained informed consent from participants who were willing to participate in this study. A structured questionnaire was then administered by a research assistant at the time of enrollment (baseline) at a meeting room of the cardiovascular ward or an education room of the outpatient department. The baseline questionnaire comprised a form on which the participants provided their demographic and clinical characteristics including age, gender, education level, marital status, economic status, and the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification, number of comorbidities, symptom distress, anxiety and depression, social support, the Piper Fatigue Scale, and the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire. The research assistant was a cardiovascular nurse and was

trained by the researcher to be familiar with the instruments. The research assistant was blinded to the patients' intervention allocation.

The control group received routine nursing care which included written material and oral education provided by the discharge planning nurse from the cardiovascular ward at the first and third week after discharge. The discharge planning nurse delivered oral education about self-care of heart failure to patients through two telephone interviews which took place at a meeting room of the cardiovascular ward. The intervention group received the 12-week supportive educational nursing care program provided by the researcher.

All patients were followed for 3 months after enrollment. The research assistant collected information on patients' levels of fatigue and quality of life at an education room of the outpatient department or at home or by telephone interviews. The levels of fatigue of the participants were assessed at four time points: the baseline and 4 weeks, 8 weeks, and 12 weeks after enrollment in both groups. The quality of life was assessed at two time points: the baseline and 12 weeks because patients were noted to have significant changes on quality of life at 12 weeks after intervention in previous studies.25, 26 Subjects completed the

questionnaire provided by a research assistant at 1-2 days after delivery of the face-to-face intervention. Figure 2 shows the intervention and data collection procedure in detail.

Intervention

The 12-week supportive educational nursing care program was designed by the authors based on the supportive intervention developed by Ream et al.20 and the symptom management model proposed by Zambroski and Bekelman.27 This supportive educational nursing care program consisted of three parts: fatigue assessment and monitoring, fatigue management education, and outcome evaluation. The intervention was delivered by one of the authors who was a senior cardiovascular nurse and familiar with the interventions. Participants in the intervention group received four face-to-face education and counseling interventions

performed by the researcher at the first visit and 4weeks, 8 weeks, and 12 weeks after the first visit at a meeting room of the cardiovascular ward or an education room of the outpatient department or at home.Each face-to-face education and counseling intervention was about 30 minutes. During the intervention, the researcher performed nursing assessment, education and counseling, and provided emotional support to patients. At the first visit, the researcher assessed the patients' levels of fatigue, their knowledge and abilities of self-management, their family support system, and their educational and counseling needs including symptoms and self-care of heart failure and fatigue. Then, the researcher would provide the specific educational and counseling to meet the patient’s individualized needs. The researcher assessed patients’ level of fatigue by asking patients to rate their fatigue range from 0 (no fatigue) to 10 (highest fatigue). An educational brochure was also provided to the patients. The educational brochure contained an introduction to heart failure and fatigue, a daily fatigue log, and information on symptom management and monitoring, medication use, and the date of follow up. The content of symptom management of fatigue included eating well, regularly moderate exercise, medications, and tips to save energy such as organizing each day, planning ahead, pacing self, balancing each activity with a rest period, asking for help from family and friends, staying at a comfortable environment. The first face-to-face education and counseling intervention played a crucial role in enhancing participants’ knowledge regarding the factors related to fatigue and strategies for managing fatigue.

The face-to-face education and counseling interventions were also conducted by the researcher at 4weeks, 8 weeks, and 12 weeks after the first visit to evaluate patients' levels of fatigue and to provide counseling and support for patients to apply strategies to manage their fatigue. The second face-to-face education and counseling intervention at 4 weeks enabled the researcher to monitor the participants’ use of the educational brochure and improve the participants’ problem-solving skills. Finally, the follow-up evaluations conducted at weeks 8

and 12 enabled the researcher to provide continual nursing care and mental support and, thus, enhance the participants’ ability to self-manage fatigue. The researcher would provide

emotional support to patients including encouraging patients to express their feelings,

listening actively to patients’ response, reassuring patients that their feelings were normal, and supporting patients in taking small steps to resolve the problem. In addition, the researcher has provided 24-hour phone calls for the participants to help them problem-solving. Within one week after each face-to-face education and counseling intervention, the researcher contacted the patients by phone at home to assess potential problems and to make an

appointment for the next intervention. These subsequent follow-up phone calls reinforced the content of education and monitored participants’ symptom management and progress.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was fatigue. It was measured using the Chinese version of the shortened Piper Fatigue Scale (PFS), which was modified from the original PFS by Chiang28 and Chen et al.1 The 15-item shortened PFS consists of two domains, namely the severity and temporal domains. For each item, the score ranges from 0 (never) to 3 (severe). The total possible fatigue score ranges from 0–45, with higher scores indicating higher levels of fatigue. The Cronbach’s alpha of the Chinese version of the PFS has previously been reported to be 0.95 in Taiwanese patients undergoing hemodialysis28 and 0.85 in patients with heart failure.1 The content validity index of the PFS was 0.83 reported by Chen et al.1 In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha of the PFS was 0.88.

The secondary outcome was quality of life. The Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ) was used to measure quality of life. The Chinese version of the MLHFQ contains 21 questions regarding the effects of heart failure on patients’ physical (8 questions), emotional (5 questions), and general (8 questions) dimensions. The possible

answer for each question ranges from 0 (no) to 5 (a lot), and the total score range is 0–105; a higher score indicates lower quality of life. Previous studies have demonstrated that the MLHFQ is a valid tool for measuring quality of life in patients with heart failure.29, 30 The content validity index of the MLHFQ was 0.98 reported by Ho et al. 31 In this study, the Cronbach’s alphas of the overall MLHFQ and the physical, emotional, and general subscales were 0.92, 0.91, 0.85, and 0.75, respectively.

Covariates

Symptomatic distress was measured using the 17-item Symptomatic Distress Index (SDI) developed by Chen et al. 1. Respondents must respond to items regarding symptoms such as dyspnea, lack of energy, sleep disturbance, and edema experienced during the previous 7 days. The score range for each item is 1 (never) to 5 (always). The total possible score ranges from 17 to 85. The content validity and reliability of this index were previously supported by a content validity index of 0.8 and a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.85 1. The Cronbach’s alpha of the SDI in this study was 0.87.

Anxiety and depression were measured using the14-item Hospital Anxiety and

Depression Scale (HADS), which consists of 7-item anxiety and 7-item depression subscales 32. Each item is scored from 0 to 3, yielding a total possible score of 21 for each of the two subscales. Higher scores indicate higher levels of anxiety and depression. For both subscales, scores of 0 to 7 are defined as noncases, scores of 8 to 10 are defined as doubtful cases, and scores of 11 or more are defined as definite cases of anxiety and depression. The internal consistency coefficient for the overall HADS, anxiety subscale, and depression subscale were reported to be 0.78, 0.73, and 0.95, respectively in patients with heart failure 1. In the present study, the Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.84 for the global scale, 0.77 for the anxiety subscale, and 0.74 for the depression subscale of the HADS.

Social Support (MSPSS) 33. The Chinese version of the MSPSS consists of three subscales: family, friends, and health care workers 34. Respondents must score each question from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The total possible score ranges from 12 to 60. Higher scores indicate higher degrees of social support. The content validity and reliability of the MSPSS have been established in psychiatric patients 34, and the Cronbach’s alpha was 0.75 in this study.

Data analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS (Version 18.0). The independent t test and chi-square test were used to examine the homogeneity of participant characteristics and outcome variables between the intervention and control group at baseline. A one-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to assess the effects of intervention on fatigue and quality of life at various time points for each group. Generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used to test the differences in fatigue and quality of life over the 12 weeks between the intervention and control groups, controlling for age, gender, and education. A value of p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

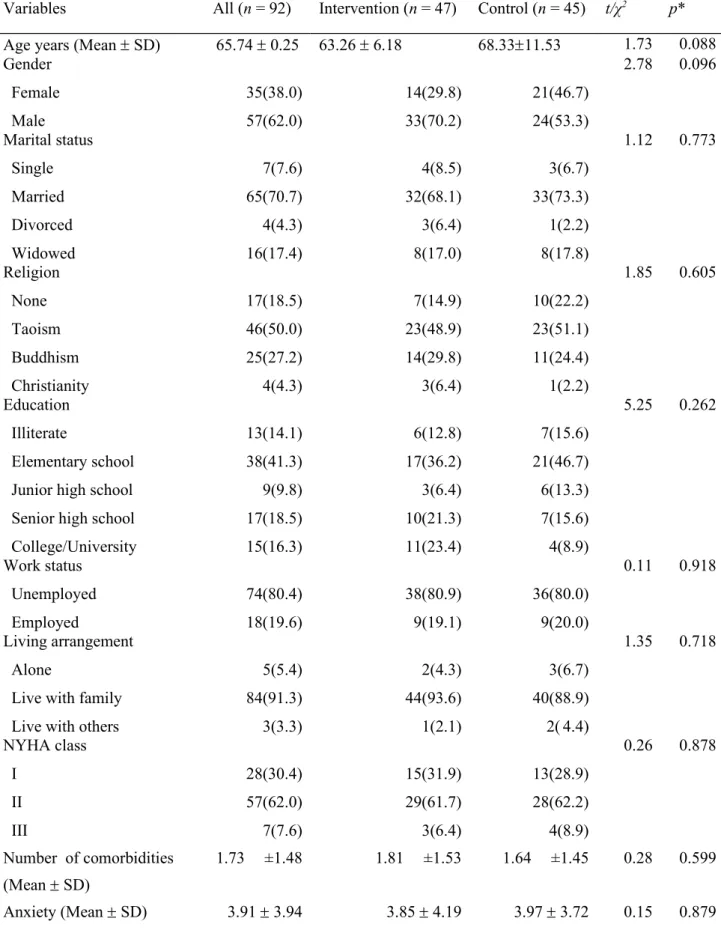

Table 1 presents the participants’ characteristics and differences between the intervention and control groups at baseline. The mean age of the participants was 65.7 years. Most

participants were male, married, unemployed, Buddhist, and had an elementary-level

education. Most had a general economic status and lived with their families. Most participants belonged to NYHA class II. There were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups at baseline in demographic and clinical characteristics, and covariates including comorbidities, symptom distress, anxiety and depression, and social support as well as in the fatigue and quality of life scores (p > 0.05).

Primary outcome

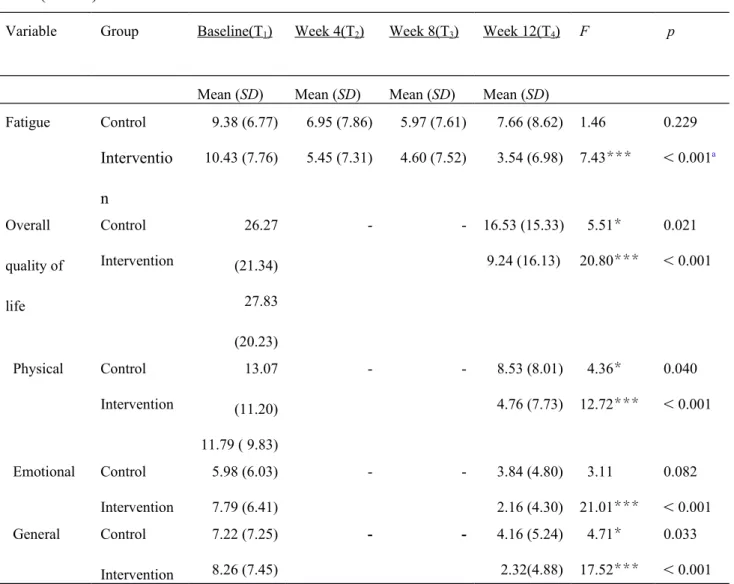

The level of fatigue significantly decreased in the intervention group (p < 0.001), whereas no significant differences were observed in the control group over the 12-week period (Table 2).

The GEE analysis indicated that compared with the control group, the intervention group exhibited a significant greater improvement in the level of fatigue after 12 weeks supportive educational nursing care program after adjusted for age, gender, and education (Table 3).

However, no significant differences in fatigue alleviation between the intervention and control group were observed 4 weeks and 8 weeks after enrollment. Figure 3 shows that the level of fatigue gradually decreased over time in the intervention group, whereas that of the control group decreased only slightly at week 4 and week 8, and even increased at week 12.

Secondary outcome

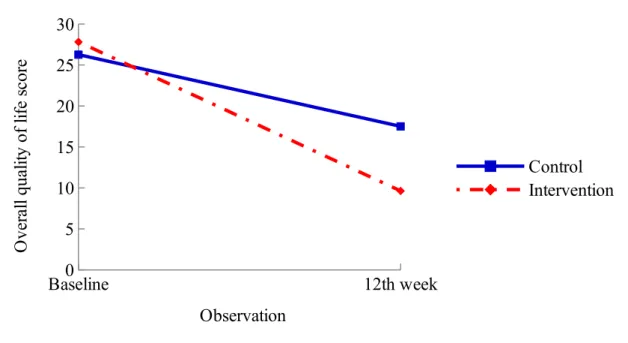

Both the intervention and control group had a significant improvement in overall quality of life, the physical and general subscales of the MLHFQ after the 12-week intervention except emotional subscale was not improved significantly in the control group (Table 2).

The GEE results revealed that the intervention group exhibited significant greater improvement in the overall quality of life score and the score on the emotional subscale of the MLHFQ compared with the control group after 12 weeks supportive educational nursing care program after adjusted for age, gender, and education (Table 3). Figure 4 shows that

participants in the intervention group exhibited greater improvement in overall quality of life than did those in the control group after participating in the 12-week supportive educational nursing care program.

Our results revealed that the 12-week supportive educational nursing care program was effective in alleviating fatigue and improving the quality of life of patients with heart failure. The effect size index (Cohen's d) between the intervention and control group was medium in fatigue (d = 0.53) and quality of life (d = 0.46). 35After the 12-week intervention, the mean

scores of fatigue ( = -5.01, p < 0.05) and quality of life ( = -10.58, p < 0 .05) were significantly improved with time in the intervention group than the control group after adjusted for age, gender, and education (Table 3). Previous studies on cancer patients have reported similar findings which reported that informational education and mental support can assist patients in managing cancer-related fatigue.20, 36-38

The effect of nurse-led supportive educational intervention on quality of life in patients with heart failure was tested in previous studies. Johansson et al.39 reviewed the literature, reporting that nurse-led interventions providing education and support play a crucial role in improving the quality of life of patients with heart failure. However, a study by Jaarsma et al.40 failed to show effectiveness of a supportive educational intervention in improving quality of life. A recent study of Cockayne et al.41 also found that nurse facilitated self-management support had no significant effect on quality of life over 12 months. The inconsistent findings could be explained by the differences on sample’s disease severity, instruments used, and delivery of intervention. For example, patients participating in the study of Jaarsma et al.40 were NYHA class III-IV which could limit the improvement of quality of life. A meta-analysis by

Samartzis et al.25 found that a face-to-face approach had greater benefit for patients’ quality of life compared with telephone-based approaches. They also reported that the effect of

intervention may be moderated by development of a supportive relationship or established of a patient-expert alliance.

In the current study, our supportive educational nursing care program was developed based on empirical practice and the symptom management model proposed in previous

studies.20, 27 The nurse-led supportive care program consisted of comprehensive assessment and education on managing fatigue, continual monitoring and consultation, and mental support. However, unlike the study of Ream et al.20 that delivered the supportive intervention by one-to-one in person, we provided the intervention by two different approaches with intensive education sessions: four face-to-face education and counseling interventions and three follow-up telephone calls. These face-to-face education and counseling interventions provided individualized education and consultation to enhance participants’ knowledge and ability to manage fatigue. The subsequent follow-up telephone calls not only reinforced the education but also provided continual emotional support and facilitated a good patient-nurse relationship. In addition, the researcher has provided 24-hour phone calls for the participants. Thus, the participants received immediate consulting and support when required, enabling them to cope with their disease-related stress, alleviate their fatigue, and improve their quality of life. In addition, the researcher provided supportive nursing care that was tailored to individualized health care demands during various disease stages. This person-centered intervention assisted patients in coping with their disease and managing with fatigue which could also promote their quality of life.

The educational brochure developed in our study can be applied in empirical practice to enhance the knowledge and ability of patients with heart failure regarding disease self-management. In addition, we recommended that nurses could provide an individualized supportive nursing care to give a positive emotional support, enhance the patients’ knowledge of self-management, and meet the patients’ physical and psychosocial needs through

continuous assessment, counseling, and education for patients with heart failure.

The attrition rate was 18.4% in this study. The selective attrition may compromise the internal validity of this study. However, Miller and Hollist 42 stated that if the dropout rates were comparable between the treatment and control groups and there were no unique

characteristics among those who drop out, then the threats to internal validity due to attrition were minimal and there was no attrition bias even though the sample decreased in size between waves of data collection. In our study, the dropout rates in the intervention group (9 out of 47) are comparable to the control group (8 out of 45). The characteristics of those who drop out of the study were not significantly different from those who remain in the study. Therefore, there was no attrition bias and the threats to internal validity due to attrition were minimal. In addition, we used the SAS GLMPOWER procedure, F test for multivariate model to calculate a post-hoc statistical power analysis. The results shown that a sample size of 75 was sufficient to have enough power (>0.8).

Limitations

Our study had several limitations. First, most of our participants were recruited from the outpatient department of a medical center and were categorized into NYHA functional classes I to III. Patients who were NYHA functional class I (30%) might have no or mild fatigue. In addition, the study patients were fairly young. Thus, most participants were independent in their daily living activities, limiting the generalizability of our study results to heart failure patients with severe functional impairment. Therefore, we suggest that future studies may include patients with all levels of functional impairment to test the effects of this type of intervention on fatigue and quality of life in those who have more serious functional

impairment as well as those who have less severe functional impairment. Second, our study assessed the effect of intervention on fatigue and quality of life over a 12-week follow-up period. However, previous studies reported that a case management intervention could effectively improve patients’ quality of life at 3 months,23 12 months,4344 and 2 years.45 A future longitudinal study can examine the long-term effect of this supportive educational nursing care program over 6–12 months. In addition, we suggest examining the effect of this

program on other outcome variables, such as emergency room visit, readmission, and

mortality rates. Finally, the structured questionnaire used in our study was comprehensive and reliable, but it required considerable time to administer, thereby limiting patients’ willingness to participate in our study. Thus, we suggested using other simple and reliable instruments to measure fatigue and quality of life in a future study to enhance patients’ motivation to participate.

Conclusion

This study confirmed that a supportive educational nursing care program can effectively alleviate fatigue and improve quality of life in patients with heart failure. We suggest applying this safe and noninvasive program in clinical practice to alleviate the fatigue and improve the quality of life of patients with heart failure. Nurses are encouraged to provide continual supportive nursing care, monitor patients’ disease progress, and serve as a patient coordinator and advocate for patients with heart failure.

References

1. Chen L-H, Li C-Y, Shieh S-M, et al. Predictors of fatigue in patients with heart failure. J Clin Nurs. 2011; 26: 487-496.

2. Evangelista LS, Moser DK, Westlake C, et al. Correlates of fatigue in patients with heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008; 23: 12-17.

3. Fink AM, Sullivan SL, Zerwic JJ, et al. Fatigue with systolic heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009; 24: 410-417.

4. Ream E and Richardson A. Fatigue: a concept analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 1996; 33: 519-529.

5. Aaronson LS, Teel CS, Cassmeyer V, et al. Defining and measuring fatigue. Image J Nurs Sch. 1999; 31: 45-50.

6. Rodrigue JR, Nelson DR, Reed AI, et al. Fatigue and sleep quality before and after liver transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2010; 20: 221-233.

7. Falk K, Swedberg K, Gaston-Johansson F, et al. Fatigue and anaemia in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2006; 8: 744-749.

8. Fink AM, Gonzalez RC, Lisowski T, et al. Fatigue, inflammation, and projected mortality in heart failure. J Card Fail. 2012; 18: 711-716.

9. Fini A and Cruz DALM. Characteristics of fatigue in heart failure patients: a literature review. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2009; 17: 557-565.

10. Tang WR, Yu CY and Yeh SJ. Fatigue and its related factors in patients with chronic heart failure. J Clin Nurs. 2010; 19: 69-78.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQOL) 2011.

12. The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Development and general psychometric properties. Soc Sci Med. 1998; 46: 1569-1585.

13. Franzen K, Saveman BI and Blomqvist K. Predictors for health related quality of life in persons 65 years or older with chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007; 6: 112-120.

14. Carson P, Tam SW, Ghali JK, et al. Relationship of quality of life scores with baseline characteristics and outcomes in the African-American heart failure trial. J Card Fail. 2009; 15: 835-842.

15. Shih M-L, Chen H-M, Chou F-H, et al. Quality of life and associated factors in patients with heart failure. J Nurs. 2010; 57: 61-71.

16. Santos JJ, Plewka JE and Brofman PR. Quality of life and clinical indicators in heart failure: a multivariate analysis. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2009; 93: 159-166.

17. Heo S, Moser DK and Widener J. Gender differences in the effects of physical and emotional symptoms on health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2007; 6: 146-152.

18. Hui D. Definition of supportive care: does the semantic matter? Curr Opin Oncol. 2014; 26: 372-379.

19. Hui D, De La Cruz M, Mori M, et al. Concepts and definitions for "supportive care," "best supportive care," "palliative care," and "hospice care" in the published literature, dictionaries, and textbooks. Support Care Cancer. 2013; 21: 659-685.

20. Ream E, Richardson A and Alexander-Dann C. Supportive intervention for fatigue in patients undergoing chemotherapy: a randomized controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006; 31: 148-161.

21. Lin J-S and Liao Y-C. The effects of muscle relaxation in improving fatigue reduction among cardiac surgery patients Tzi Chi Nuis J. 2003; 2: 46-54.

22. Pozehl B, Duncan K and Hertzog M. The effects of exercise training on fatigue and dyspnea in heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2008; 7: 127-132.

23. Wang SP, Lin LC, Lee CM, et al. Effectiveness of a self-care program in improving symptom distress and quality of life in congestive heart failure patients: a preliminary study. J Nurs Res. 2011; 19: 257-266.

24. Soper DS. A-priori Sample Size Calculator for Student t-Tests [Software]. 2014. 25. Samartzis L, Dimopoulos S, Tziongourou M, et al. Effect of psychosocial

interventions on quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Card Fail. 2013; 19: 125-134.

26. Dunbar SB, Butts B, Reilly CM, et al. A pilot test of an integrated self-care

intervention for persons with heart failure and concomitant diabetes. Nurs Outlook. 2014; 62: 97-111.

27. Zambroski CH and Bekelman DB. Palliative symptom management in patients with heart failure. Prog Palliative Care. 2008; 16: 241-249.

28. Chiang W-Y. Hemodialysis patients' fatigue relating to depression, social support and blood biochemical data. The Kaohsiung Medical University, 1995.

29. Heo S, Doering LV, Widener J, et al. Predictors and effect of physical symptom status on health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. Am J Crit Care. 2008; 17: 124-132.

30. Middel B, Bouma J, de Jongste M, et al. Psychometric properties of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHF-Q). Clin Rehabil. 2001; 15: 489-500. 31. Ho C-C, Clochesy JM, Madigan E, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese

version of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire. Nursing research. 2007; 56: 441-448.

Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983; 67 361-370.

33. Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, et al. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1988; 52: 30-41.

34. Shu SF. Community adjustment, self-concept and social support of schizophrenic patients. Kaoshiung: Kaoshiung medical university, 1997.

35. Sullivan GM and Feinn R. Using Effect Size—or Why the P Value Is Not Enough. J Grad Med Educ. 2012; 4: 279-282.

36. Wanchai A, Armer JM and Stewart BR. Nonpharmacologic supportive strategies to promote quality of life in patients experiencing cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2011; 15: 203-214.

37. Yennurajalingam S, Urbauer DL, Casper KL, et al. Impact of a palliative care

consultation team on cancer-related symptoms in advanced cancer patients referred to an outpatient supportive care clinic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010; 41: 49-56.

38. Yates P, Aranda S, Hargraves M, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an educational intervention for managing fatigue in women receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005; 23: 6027-6036.

39. Johansson P, Dahlstrom U and Brostrom A. Factors and interventions influencing health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure: a review of the literature. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006; 5: 5-15.

40. Jaarsma T, Halfens R, Tan F, et al. Self-care and quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure: The effect of a supportive educational intervention. Heart Lung. 2000; 29: 319-330.

41. Cockayne S, Pattenden J, Worthy G, et al. Nurse facilitated Self-management support for people with heart failure and their family carers (SEMAPHFOR): a randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2014; 51: 1207-1213.

42. Miller RB and Hollist CS. Attrition Bias. Faculty Publications: (2007).

43. Sisk JE, Hebert PL, Horowitz CR, et al. Effects of nurse management on the quality of heart failure care in minority communities: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006; 145: 273-283.

44. Lainscak M and Keber I. Heart failure clinic in a community hospital improves outcome in heart failure patients. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006; 136: 274-280.

45. Del Sindaco D, Pulignano G, Minardi G, et al. Two-year outcome of a prospective, controlled study of a disease management programme for elderly patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Med. 2007; 8: 324-329.

Table 1. Test of the homogeneity of participant characteristics, fatigue and quality of life at baseline between the two groups (n = 92).

Variables All (n = 92) Intervention (n = 47) Control (n = 45) t/χ2 p*

Age years (Mean SD) 65.74 0.25 63.26 6.18 68.3311.53 1.73 0.088

Gender Female Male 35(38.0) 57(62.0) 14(29.8) 33(70.2) 21(46.7) 24(53.3) 2.78 0.096 Marital status Single Married Divorced Widowed 7(7.6) 65(70.7) 4(4.3) 16(17.4) 4(8.5) 32(68.1) 3(6.4) 8(17.0) 3(6.7) 33(73.3) 1(2.2) 8(17.8) 1.12 0.773 Religion None Taoism Buddhism Christianity 17(18.5) 46(50.0) 25(27.2) 4(4.3) 7(14.9) 23(48.9) 14(29.8) 3(6.4) 10(22.2) 23(51.1) 11(24.4) 1(2.2) 1.85 0.605 Education Illiterate Elementary school Junior high school Senior high school College/University 13(14.1) 38(41.3) 9(9.8) 17(18.5) 15(16.3) 6(12.8) 17(36.2) 3(6.4) 10(21.3) 11(23.4) 7(15.6) 21(46.7) 6(13.3) 7(15.6) 4(8.9) 5.25 0.262 Work status Unemployed Employed 74(80.4) 18(19.6) 38(80.9) 9(19.1) 36(80.0) 9(20.0) 0.11 0.918 Living arrangement Alone

Live with family Live with others

5(5.4) 84(91.3) 3(3.3) 2(4.3) 44(93.6) 1(2.1) 3(6.7) 40(88.9) 2( 4.4) 1.35 0.718 NYHA class I II III 28(30.4) 57(62.0) 7(7.6) 15(31.9) 29(61.7) 3(6.4) 13(28.9) 28(62.2) 4(8.9) 0.26 0.878 Number of comorbidities (Mean SD) 1.73 ±1.48 1.81 ±1.53 1.64 ±1.45 0.28 0.599 Anxiety (Mean SD) 3.91 3.94 3.85 4.19 3.97 3.72 0.15 0.879

Depression (Mean SD) 5.05 4.14 5.10 3.96 5.00 4.35 -0.12 0.903

Social Support (Mean SD) 45.67 6.75 45.76 6.48 45.57 7.09 -0.13 0.895

Outcome Variables Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD) t p

Fatigue 9.91 (7.27) 10.36 (7.77) 9.06 (6.71) -0.85 0.396

Quality of life scores 27.06 (20.67) 27.82 (20.22) 26.26 (21.33) -0.36 0.719

Physiological 12.41 (0.50) 11.79 (9.83) 13.07 (1.20) 0.58 0.561

Emotional 6.90 (6.26) 7.79 (6.41) 5.98 (6.03) -1.39 0.167

General 7.75 (7.33) 8.26 (7.45) 7.22 (6.41) -0.67 0.502

Note: *p is the difference between the control and intervention group from t test and chi-square test. A

Table 2. Comparisons of fatigue and quality of life within each group at various time points (n = 75)

Variable Group Baseline(T1) Week 4(T2) Week 8(T3) Week 12(T4) F p

Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Mean (SD) Fatigue Control Interventio n 9.38 (6.77) 10.43 (7.76) 6.95 (7.86) 5.45 (7.31) 5.97 (7.61) 4.60 (7.52) 7.66 (8.62) 3.54 (6.98) 1.46 7.43*** 0.229 < 0.001a Overall quality of life Control Intervention 26.27 (21.34) 27.83 (20.23) - - 16.53 (15.33) 9.24 (16.13) 5.51* 20.80*** 0.021 < 0.001 Physical Control Intervention 13.07 (11.20) 11.79 ( 9.83) - - 8.53 (8.01) 4.76 (7.73) 4.36* 12.72*** 0.040 < 0.001 Emotional Control Intervention 5.98 (6.03) 7.79 (6.41) - - 3.84 (4.80) 2.16 (4.30) 3.11 21.01*** 0.082 < 0.001 General Control Intervention 7.22 (7.25) 8.26 (7.45) - - 4.16 (5.24) 2.32(4.88) 4.71* 17.52*** 0.033 < 0.001 Note: *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p <0.001. a: post-hoc analysis, T 1 > T2, T1 > T3, T1 > T4.

Table 3. Comparisons of the differences on fatigue and quality of life between groups over time using GEE analysis (n = 75).

Variables Time × group β SE 95% CI p Fatigue Baseline Week 4 Week 8 Week 12 0a -2.73 -2.08 -5.01 1.56 1.79 2.20 -5.79, 0.34 -5.58, 1.42 -9.31, -0.70 0.081 0.244 0.023 Overall quality of life

Baseline Week 12 0a -10.58 4.96 -20.30, -0.86 0.033 Physical Baseline Week 12 0a -3.25 2.57 -8.28, 1.79 0.206 Emotional Baseline Week 12 0a -4.32 1.51 -7.28, -1.37 0.004 General Baseline Week 12 0a -3.01 1.72 -6.38, 0.36 0.080

Note: Adjusted for age, gender, and education

.

a: It is set to zero because this parameter is redundant.

22 Assessed for eligibility (n = 96)

Excluded (n = 4)

Refused to participate (n = 2) Incomplete questionnaire (n = 1) Unable to communicate (n = 1)

Allocation to intervention (n = 47) Received allocated intervention (n =47)

Allocation to control (n = 45) Received allocated control (n =45) Analysed (n = 42)

Lost to follow-up (n = 5): Readmission (n = 4), Loss of contact (n = 1)

Analysed (n = 38)

Lost to follow-up (n = 7): Death (n = 2), Readmission (n = 3), Analysed (n = 41)

The first week (Before discharge or at outpatient department) 4th week 8th week 12th week Randomized Control group Intervention group

Fill out the questionnaire provided by a research assistant Fill out the questionnaire provided by a research assistant

Location: meeting room at ward 1. Routine nursing care provided by

discharge planning nurses The first face-to-face education and counseling intervention

Location: meeting room at ward or education room at outpatient department

1. Researcher provided supporting nursing care including assessment of patients' needs, education and counseling, emotional support.

2. Researcher provided fatigue self-care brochure

Two telephone interview provided by discharge planning nurses (First and third week after discharge)

The first telephone interview

(Three to four days after firstintervention)

Location: education room at outpatient or at home

1. Fill out the questionnaire provided by a research assistant

The second face-to-face education and counseling intervention Location: education room at outpatient or at home

1. Researcher provided supporting nursing care

2. Fill out the questionnaire provided by a research assistant at 1-2 days after intervention

The second telephone interview (One week after second intervention)

Location: education room at outpatient or at home

1. Fill out the questionnaire provided by a research assistant

The third face-to-face education and counseling intervention Location: education room at outpatient or at home

1. Researcher provided supporting nursing care 2. Fill out the questionnaire provided by a research

assistant at 1-2 days after intervention

The third telephone interview (One week after thirdintervention) The fourth face-to-face education and counseling intervention Location: education room at outpatient or at home

1. Researcher provided supporting nursing care 2. Fill out the questionnaire provided by a research

assistant at 1-2 days after intervention

Location: education room at outpatient or at home

1. Fill out the questionnaire provided by a research assistant

Baseline0 4th week 8th week 12th week 2 4 6 8 10 12 Control Intervention Observation F at ig ue s co re

Fig. 3. Comparison of fatigue scores between the two groups over the 12–week follow-up period Baseline0 12th week 5 10 15 20 25 30 Control Intervention Observation O ve ra ll qu al ity o f lif e sc or e

Fig. 4. Comparison of overall quality of life scores between the two groups after 12 weeks of follow up