行政院國家科學委員會專題研究計畫 成果報告

選區、政黨與立法委員的三角關係:選制變遷前後的比較

(第 3 年)

研究成果報告(完整版)

計 畫 類 別 : 個別型 計 畫 編 號 : NSC 95-2414-H-004-046-MY3 執 行 期 間 : 97 年 08 月 01 日至 99 年 01 月 31 日 執 行 單 位 : 國立政治大學政治學系 計 畫 主 持 人 : 盛杏湲 計畫參與人員: 碩士級-專任助理人員:葉怡君 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:黃士豪 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:辜浩維 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:王北辰 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:張正莼 碩士班研究生-兼任助理人員:林明瑩 博士班研究生-兼任助理人員:陳進郁 博士班研究生-兼任助理人員:蔡韻竹 博士班研究生-兼任助理人員:陳蓉怡 處 理 方 式 : 本計畫可公開查詢中 華 民 國 99 年 04 月 20 日

1

The Triangles among Constituencies, Parties, and Legislators:

How Legislators Respond to a New Electoral System

By

Shing-Yuan Sheng Department of Political Science

National Chengchi University

2

The Triangles among Constituencies, Parties, and Legislators:

How Legislators Respond to a New Electoral System

Introduction

When legislators make decisions in the political process, they may face political pressures from two major forces: their party and their constituency. Legislators are influenced by these two forces in different degrees and ways across different electoral systems. Carey and Shugart (1995) have systematically evaluated a variety of

electoral systems under which legislators attempt to enhance either their personal or party reputation. Put simply, if legislators must count on themselves rather than their party to attract voters, they have stronger incentives to promote their personal

reputation. They may attract electoral support through their personal qualities, qualification, activities, and records, rather than through their party affiliation (Cain, Ferejohn, and Fiorina 1984; 1987). On the other hand, if legislators need to count on their party to get elected, they have a stronger intensive to promote their party reputation.

Taiwan’s electoral reform in 2005 provides a rare opportunity to examine how the electoral reform changes legislators’ electoral calculations and representative behavior. Before the reform, Taiwanese electoral system was multi-member district single non-transferable vote (hereafter SNTV) plus closed-list proportional

representation (hereafter PR) system. District legislators under SNTV had strong incentives to build a base of personal vote. They thus tried to attract electoral

support through their personal reputation rather than through their party’s reputation. They tended to be more considerate of their constituency, conducting casework, introducing particularistic interest bills to provide benefits, and supporting the adoption of pork barrel projects in exchange for the electoral support of their constituents (Hawang 1994; Luor 2001; 2004; Luor and Liao 2009; Sheng 2005; 2006). Whenever a conflict between their party and their constituency occurred, legislators would tend to display more loyalty towards their constituency, rather than to their party (Sheng 1996). Even though they seldom opposed their party in public, they might idle in legislation and put more time and resources in constituencies.

3

Occasionally, they might deviate from the party line (Sheng 1996; 2005).

In June 2005, the electoral system had reformed from SNTV plus a closed-list PR to a mixed system of single member district plural system (hereafter SMD) plus a closed-listed PR system. Then, do the triangles among legislators, constituencies, and parties change because of the new electoral system? Do legislators’ representative styles and behavior change because of the change of the triangles? If they do change, then how do they change?

I argue that the triangles among constituencies, parties and legislators are

dynamic and shaped by intra-party and inter-party competition in elections and in the legislative process. Both levels of competition are affected by electoral systems and the party operation in elections and in the legislative process. If legislators face

greater intra-party competition, they cannot get great help from their party so that they have strong incentives to establish a personal vote. However, if legislators face greater inter-party competition, they have strong incentives to establish a party vote. To do so, they may cooperate with their co-partisans to initiate bills and make public policies so as to establish party reputation. In this article, I will show how legislators under a new electoral system have both greater intra-party and inter-party competition than under the old one and how they adjust in respond.

This article explores representative politics from both the old and new electoral system. The electoral reform in Taiwan provides a chance of something like “natural experiment” so that we may observe what impacts a new electoral reform may bring about. This exploration bases on long term observations on legislators’ behavior from 1996 to 2009. Data used in this research include surveys on legislators’ assistants, intensive interviews on legislators and their assistants, legislators’ introduction of bills, and roll call votes. Even though we still need more time to assess the real

consequences of the electoral reform, systematic observations need to be done when changes are going on.

The next section first describes the triangles among constituency, party and legislators, followed by an analysis of the triangles across electoral systems. Next, attention will be focused on the representative politics in the Taiwanese context. I then elaborate on my theory and hypotheses about the change after the electoral reform.

4

Then, I present the empirical evidence. Finally, I will discuss the implications of the empirical findings.

Constituency, Party and Legislators in a Comparative Context

In most democracies, legislative bodies are comprised of representatives elected from different geographical areas. One of the primary goals of the representatives is to articulate and promote the interests of their constituents at the national representative body. However, constituency-oriented legislators might very possibly descend into endorsing excessive pork barrel legislation and projects. Such legislation and projects would benefit legislators’ parochial constituencies to the detriment of the entire country. On the other hand, the function of party in a democracy is to aggregate the interests of different groups of people. Parties thus inherently are more national and collective oriented compared to individual legislators. Parties play an important role in counterbalancing the parochial interests from constituencies. Without parties in the legislative process there would be nothing preventing a nation’s political system from degenerating into parochial and disorder severely impairing a legislature’s ability to efficiently carry out its legislative duties. Given, then, that parties play an important role in the legislative process, the question of how a party is able to play a leading role in the legislative process, becomes relevant. In other words, what motivates legislators to follow the party line? The most basic answer to this question is that the party can provide legislators with sufficient incentives.

In general, these incentives include both tangible and intangible benefits. First, since legislators from the same party have the same electoral fate as their party, they share the success and failure in party’s policy-making and legislation. This may result in a kindred spirit mentality for legislators from the same party thereby ensuring that they keep in step and take the same positions on important legislations (Cox and McCubbins 1993). Second, the party provides an available legislative coalition that makes legislation possible, easy, and efficient (Cox and McCubbins 1993). Thus, if individual legislators support a particular piece of legislation, they can rely on the party to aid them in pushing their agenda. Third, the party provides legislators with important legislative cues so that legislators not familiar with particular legislation or issues may participate in the process and carry out their legislative duties effectively

5

(Kingdon 1989). Fourth, the party possesses power and resources that may be used to reward or punish legislators according to their legislative performance. This is evident through such means as nominating candidates for elections, helping

legislators in their election campaigns, providing benefits to legislators’ constituencies, assigning legislators to particular legislative committees, and arranging legislative schedules.

All of these incentives are directly or indirectly related to legislators’ incentives for election and re-election. The more capable a party is at providing electoral benefits to its legislators, the more likely its legislators will pursue party reputation.

Conversely, if a party provides its members with relatively limited help, its legislators will quite possibly pursue their personal votes. Legislators will thus try and attract electoral support through personal qualities, qualifications, activities, and records, rather than through their party affiliation, voter characteristics, or reactions to national conditions (Cain, Ferejohn and Fiorina 1984; 1987). When legislators pursue such a strategy, they will tend to be more considerate of their constituency, conducting casework or supporting the adoption of pork barrel projects in exchange for the electoral support of their constituents. Whenever a conflict between legislators’ party and their constituency occurs, they would tend to display more loyalty towards their constituency, rather than to their party.

Mayhew (1974) has argued convincingly that legislators focused

single-mindedly on their re-election must behave in some way connected to elections. Further, Carey and Shugart (1995) have systematically evaluated a variety of electoral systems under which legislators attempt to enhance either their personal or party reputation. Put simply, if legislators must count on themselves rather than their party affiliation to attract voters, they have a stronger motivation to promote their personal reputation. On the other hand, if legislators need to count on their party to get elected, they have a stronger motivation to promote their party reputation. According to their analysis, several factors enhance personal vote-seeking: (1) the party leadership is not able to control the ranking of the party’s candidates on ballots; (2) the candidates are elected on individual votes independent of co-partisans; (3) voters cast a single intra-party vote instead of multiple votes or a party-level vote; and (4) if the electoral system itself fosters the value of a good personal reputation,

6

personal-vote seeking will increase as the district magnitude rises; in contrast, if the electoral system itself fosters the value of a good party reputation, personal-vote seeking will decline as the district magnitude rises. Using this rank ordering of electoral formulas, Carey and Shugart indicate that candidates in a single member district system with open endorsement (such as a primary system), candidates in an open-list PR system, or candidates in an SNTV system, have strong incentives to promote their personal reputation in order to obtain electoral success; while, in contrast, the candidates in a single member district plurality system with a party leader endorsement and candidates in a closed-list PR system have strong incentives to promote their party reputations (1995, 425).

The representative styles in Great Britain and the United States provide us with two different prototypes. The representative style seen in Great Britain is based more on a party-orientation because its legislators rely heavily on their party affiliation in order to secure reelection. Therefore, the value to members of providing parochial benefits to their constituencies is curtailed and hence they act collectively more partisan and are more programmatic, nationally oriented and policy-oriented (Shugart and Carey 1992, 168-169). This is the so-called “Efficient Secret” model, named first by Cox (1987). In contrast, the representative style seen in the United States is more constituency-oriented because members rely more heavily on their own resources to get campaign contributions to win primaries and general elections. Therefore, they put their time and resources into their constituencies: (1) to provide casework for their constituents; (2) to bring “pork”—such as federal grants, subsidies, and public works projects—to their constituencies; and (3) to introduce particularistic legislation to please specialized groups while usually avoiding labor-intensive substantial and national policy-making (Mayhew 1974; Fiorina 1980; 1989; Jacobson 1992). Even though they may sometimes be involved in substantial national policy-making to serve more diffuse, general, and unorganized interests, they do this because of electoral calculations, and political leaders provide some benefits to persuade or buy them in (Arnold 1990; Evans 2004).

In addition to the British and American cases, legislative behavior demonstrated in various countries has provided us with many empirical findings to examine the proposition of electoral connection. In some presidential systems other than the

7

United States, the electoral systems do not provide legislators with strong enough incentives to promote their party reputation, so instead they improve their chances at re-election by providing particularistic benefits to their parochial districts (Shugart and Carey 1992, 167-205). Brazil, for example, uses an open-list PR system for legislative elections, so legislators there face intra-party competition and have a strong motivation to build their personal vote bases. Those legislators with domination of local constituencies and with clustered supportive bases have an even stronger motivation to bring pork to their constituencies. Meanwhile, because of the executive dominance over pork-barrel programs, legislators with the incentives to bring pork to their constituencies have motivation to build good relations with the president. Therefore, legislators with dominant votes or clustered votes tend to be more opposed to a stronger congress, and more supportive of the executive in return for special favors for their constituency (Ames 1995; 2002). In addition, doing research on the legislator-introduced bills and those enacted into laws, Amorim Nato and Santos (2003) indicate that legislators with a concentrated vote-getting style have a stronger motivation to introduce bills with parochial benefits.

In addition, research on six Latin America presidential democracies, Crisp et. al (2004) indicate that the focus of individual legislators on parochial or national concerns responds to the incentives provided by the candidate selection process, general election rules, legislators career patterns, and inter-branch relations. They argue that more legislation targeting national issues when legislators do not face co-partisans, while more legislation to deliver local pork barrel projects and particularistic services when personalizing effects are introduced by the party’s candidate selection procedure or by the electoral laws.

Germany provides a good example for examining in one nation the two kinds of legislators from different electoral systems. In Germany, half of legislators are elected from single-member districts under plurality rule and the other half are chosen through party-list PR. Research has shown that district representatives have a stronger motivation to bring pork to their districts and they tend to seek assignments to committees from which they can claim credits more easily (Lancaster and Patterson 1990; Stratmann and Baur 2002).

8

Japan had electoral reform in 1994. Before the reform, Japan was an SNTV system. With a parliamentary system, Japanese legislators had to be supportive of party policies to maintain the ruling party’s position in parliament. However, under the SNTV electoral system, LDP legislators had strong incentives to provide parochial benefits to develop their personal vote. To get support from legislators, the LDP leadership provided campaign funding to its legislators and assigned them to LDP’s particular committees1 related to the legislators’ constituencies so that the legislators could provide pork and took credits easily (Ramseyer and Rosenbluth 1993, 16-37). In this way, the LDP maintained the support of legislators with strong personal-vote incentives. However, around 30 percent of the Japanese budget went to

particularistic allocations, such as subsidies and public works (Shugart and Carey 1992, 169). Even worse, the distribution of the subsidies and public service projects was uneven and financially inefficient. Senior LDP legislators from some parochial areas always got greater specific public service projects and funds for public

constructions. Their voters rewarded them in elections, and hence they won reelection easily. Legislators from other areas who got relatively less pork face more challenges in elections. Consequently, some areas were allocated too many funds and subsidies, leading to underutilized or idle public facilities, while others with limited funds and subsidies had underdeveloped public infrastructure (Fukui and Fukai 1996).

In 1994, Japan changed the electoral system to a mixed system of SMD plus a PR system. The new electoral system permits dual candidacy; that is, the candidates run SMD may also put their names in PR list. This perpetuates the personal vote and personal support organizations. Furthermore, the new system leads PR legislators to be locally-based politicians who rely on personal rather than party-based or

programmatic campaigning (Mckean and Scheiner 2000). Also, Hirano (2006) indicates that legislators in a SMD still make personal rather than policy-oriented appeals to voters. However, since SMD legislators need to get more than 50 percent of votes in the district, they are trying to enlarge their supporting groups. They cultivate ties with organizations and sub-constituency to which they had not been connected in the past.

1 Policy Affairs Research Council (PARC) is LDP’s policy making apparatus. Through their

participation in the PARC’s policymaking deliberations, LDP backbenchers press for policies and budget allocations that benefit their constituency (Ramseyer and Rosenbluth 1993, 31).

9

In conclusion, the governmental system, the electoral system and the role of party in government and elections affect legislators’ behavior decisively. In parliamentary systems and in those in which the party is able to decide legislators’ fate, legislators are motivated to be more partisan, programmatic, nation-oriented, and policy-oriented. However, if legislators need to count on themselves to win elections, they will be motivated to personalized, particularized, and interest-oriented. They tend to bring special interests to their parochial districts. To get support from legislators, the party leaders tend to meet legislators’ needs, such as providing public service projects, subsidies, and funds for construction. The overall effect is financial inefficiency and uneven development across different districts. In presidential systems and those in which the electoral system does not provide legislators with enough motivation to promote their party reputation, legislators have strong

incentives to pursue a personal vote. In elections, candidates may provide campaign promises of particularistic benefits to attract voters. Once they get into the

legislature, they have incentives to bring pork to their parochial districts.

The Old and New Electoral Systems in Taiwan

Before the electoral reform in 2005, Taiwanese legislators were elected based on two formulas. In 225 seats, approximately 75 percent of seats, 168 district

representatives were elected through an SNTV electoral system. Based on the population of the district, districts were allotted 1 to 13 seats.2 In addition, approximately 25 percent of seats are assigned through a closed-list PR system.

In August 2004, the Legislative Yuan passed an initiative of constitution amendment, which included the electoral reform proposal.3 It was unusual for incumbent legislators to initiate a reform on the exiting electoral system, especially for decreasing the number the seats into a half (113 seats). The reason for this pass was because of the coming election in December 2004. Taiwanese people were unsatisfied with the Legislative Yuan and they thought that legislative reform may emerge from the electoral reform.4 If a legislator had disapproved the electoral

2 There was only one legislator in four districts because of the small population in these districts. 3 According to the Constitution, an initiative of constitution amendment needs to be passed by the

Legislative Yuan and seconded by the National Assembly.

10

reform proposal, he/she would be accused of anti-reform and highly possible that he/she could not be re-elected in the next election. This public mood forced

incumbent legislators to approve the reform proposal even though they hesitated in making this decision. The reform proposal passed with more than 90 percent approval by the legislators. The proposal was voted by the National Assembly and

implemented in June 2005.

Because legislators were reelection-oriented and future-oriented, not long after the legislators celebrated the victory of the election, they prepared themselves for the next election; that is, under a new electoral system. They began to rearrange their offices to a new constituency, meeting with not only their old supporters, but also new constituents so that they might expand their supporting groups. Some of them might even change their representative style, such as from a work horse in the legislature to a servant to their constituents, if they thought it was necessary.

The new electoral system is a mixed system of single member district plurality system plus a closed-listed PR system. Voters have two ballots, one for a single candidate, and the other for a party. The party representatives have no dramatic change in terms of their relationship with party and constituents. They were assigned and ranked by party, and thus they have a strong incentive to follow the party line in the legislative process. In this article, I focus on district representatives who encounter a different electoral system from an SNTV to an SMD. Some detailed regulations of the reform are shown in Table 1.

[Table 1 about here]

Background of Representative Behavior in Taiwan

The representative style of Taiwanese legislators experienced dramatic changes, responding to the changes in Taiwanese political development and party competition.

Before the mid-1980s: Limited Inter-Party and Intra-Party Competition

The Nationalist Party (Kuomintang, hereafter KMT) was the dominant party in the Legislative Yuan with more than 80 percent of seats before the mid-1980s. (The Yuan (Sheng and Huang 2006).

11

percentage of votes and seats shared by the parties are shown in Table 2.) Since the KMT nominated more than one candidate per district, there was potential intra-party competition. To maintain its advantage in elections, the KMT used a strategy called the “Responsible Zone system” to limit each of the candidates to campaign in a particular geographical zone. In this way, each of the KMT candidates should get a moderate number of votes and many KMT candidates could be elected. At that time, the KMT could control intra-party competition in a limited scale. Because of the successful strategy, KMT’s nominations almost directly decided the fate of the

legislators’ reelection. Candidates nominated by the KMT had more than a 95 percent probability of being elected at that time. During this period of time, as Ho (1986) noted, the electoral successes of KMT legislators did not hinge on their active participation in policy deliberation or their constituency services, but on their loyalty to the party. Therefore, individual legislators followed the KMT’s leadership and voted for the bills initiated by the executive branch in exchange for reelection.

[Table 2 about here]

1986~2000: Increasing Intra-Party competition and Inter-party Competition. Relatively, KMT legislators face greater intra-party competition but Smaller Inter-party Competition than DPP legislators.

When the Democratic Progressive Party (hereafter DPP) emerged on the political arena in 1986, the KMT legislators started to face intra-party competition inherited in SNTV system. District representatives under an SNTV system had a strong incentive to pursue personal vote because there was strong intra-party competition (Sheng 1996; 2000). It was very likely that the strongest challenge came from co-partisans rather than the candidates of the opposite party. This was for two reasons. First, it was harder to get votes from the opposite party, but was easier to get votes from the same party because many Taiwanese voted according to their party identification. Second, being a dominant party in Taiwan for decades, KMT had lots of votes, while the opposition had limited votes. Because of this fierce intra-party competition, KMT legislators had strong incentives to build their own base of personal vote. They built their own campaign organization, provided special benefits through legislation, and served their constituents through casework (Batto 2005; Hawang 1994; Luor and

12

Hsieh 2008b; Sheng 2000). In pursuing this strategy, KMT legislators would tend to serve their constituency in exchange for the electoral support of constituents. Thus, when a contradiction between party and constituency occurred, some legislators might even deviate from the party line and display loyalty to their respective constituencies (Sheng 2001a).

Compared to KMT legislators, DPP legislators face greater inter-party

competition, but smaller intra-party competition during this period of time. That is because when the DPP entered into the political arena in the mid-1980s, it was small in terms of the percentage of votes and seats. Therefore, DPP legislators needed to grasp votes from the majority party, the KMT. They needed to be cohesive to pass legislation and block legislation from the KMT. In this way, it might be trusted by the electorate. No DPP legislators could free ride on others because of the small size. At that time, party vote was more important than personal vote for them. They needed party’s help in reelection, thus they had strong incentive to be cohesive to establish party’s reputation (Sheng 2008). Relatively, they tended to emphasize legislative work more than constituency services. That is because DPP legislators did not have

powerful organizations or local factions as the established KMT legislators (Sheng 2000).

2000~2004: Large Intra-Party and Inter-Party Competition.

The DPP won the presidential election in 2000 and became the largest party in the legislature in 2001 with 38.7 percent of seats. Relatively, the KMT separated and got only 30.2 percent of seats. At that time, even though the KMT was weak, the KMT and People First Party (PFP) together (the so called pan-blue coalition) still held more than half of the seats in the legislature. Because of the serious partisan conflict during the elections and a divided government organized after the presidential election, the KMT legislators were much more cohesive than usual (Hawang 2003; Sheng 2008). In the meantime, though the legislators of PFP left the KMT, they cooperated with the KMT legislators in most substantial legislations because they shared the same supporting groups (Yu 2005). This made DPP’s new government faced a

political dilemma. Even worse, the DPP faced a challenge from a newly founded party, the Taiwan Solidarity Union (TSU), a party on the same side but more extreme than

13

the DPP on the independence/unification issue dimension (the major issue of political cleavage), emerged and undermined DPP potential supporting groups. The DPP and the TSU sometimes cooperated in legislations. Traditionally these two parties comprised the pan-green coalition. In the meantime, inter-party competition became intense because the heated pan-blue and pan-green conflict. This made legislators cohesive to establish party reputation. As Sheng (2008) indicates, both KMT and DPP legislators maintained a high level of party cohesion after the party turnover in 2000.

Once the DPP’s seats share increased, inter-party and intra-party competition became intense for both DPP and KMT legislators. They had higher incentives to benefit their constituents to pursue a personal vote. They not only spent more time in their constituencies, and conducting more casework, but also introduced bills to provide benefits to their constituency (Sheng 2006). Most of these

legislator-introduced bills were small-impact, narrow scope and non-partisan. Most of them were particularistic interest bills and tried to take a free ride on the national policy which was mostly formulated and introduced by the executive branch. In addition, legislators from smaller districts compared to those from larger districts had an even higher motivation to introduce particularistic interest bills (Luor and Hsieh 2008; Luor and Liao 2009; Sheng 2006). Furthermore, legislators from districts with greater intra-party competition were more likely to introduce bills to bring

particularistic interest to their constituency because they had an even higher

motivation to get personal vote (Sheng 2006). When there was conflict between party interests and constituency interests, legislators facing more inter-party competition were more likely to follow the party lines, while legislators facing more intra-party competition were more likely to deviate from the party lines (Sheng 1996).

According to previous analysis, under SNTV, Taiwanese legislators conducted different representative behavior during different periods of time. However, two major rules guide their behavior: First, the greater the intra-party competition, the greater the possibility legislators need to get personal vote. To get personal vote, they have strong incentives to provide benefits to constituency. Second, the greater the inter-party competition, the greater the possibility legislators need to get party vote. To get party vote, they have stronger incentives to provide support to their party to establish party reputation. In the following, I will base on these two rules to

14

examine legislators’ behavior after electoral reform and establish my hypotheses.

Representative Behavior Before and after the Electoral Reform:

Theory and Hypotheses

To theorize the impacts of an electoral system on legislators’ behavior, I utilize two concepts: intra-party competition and inter-party competition. I argue that the triangles among constituencies, parties and legislators are dynamic and shaped by intra-party and inter-party competition in elections and in the legislative process. The two levels of party competition are affected by electoral systems and the party operation in elections and in the legislative process. If legislators face greater

intra-party competition, they are unable to get great help from their party so that they have strong incentives to get personal vote. In contrast, if legislators face greater inter-party competition, they need to get party vote, and hence they have strong incentives to promote their party reputation. To pursue personal vote, legislators need to close to their constituency, and hence provide particularistic benefits to

constituency. To pursue party vote, legislators need to close to their party and hence maintain high party cohesion and defend party’s position, as well as vote for the party line.

As mentioned previously, under an SNTV system, legislators facing heated intra-party competition had incentives to pursue personal vote, and thus tended to be particularistic and localized. In the new SMD system, legislators are even more particularistic and localized. Not only because candidates under a candidate-ballot electoral system have a higher incentive to offer particularistic benefits to constituents, as previous literatures well elaborated (Carey and Shugart 1995; Norris 2004,

230-234). This is also because of three major reasons. First, because there is only a single legislator in a district, legislators can claim credit easily while are unable to avoid blame from constituents if they are idle. Research has shown that legislators from smaller districts have a stronger incentive to bring particularistic interests to their constituency (Sheng 2006). Lancaster (1986) provides a convincing rationale that the smaller the districts, the identifiability is higher, and therefore accountability linkage between legislators and constituents is easier. This leads legislators have incentive to provide pork to their constituency. In contrast, when the magnitude of

15

district is greater, the accountability becomes vague, and thus legislators might

encounter free-riding from other legislators of the same district and thus may decrease the incentive of providing pork. In addition, since there is only one legislator per district, legislators are more easily identifiable by constituents with demands. If they refuse or they are idle, they are easily to be found and accused. This leads them to be diligent in providing services and benefits. According to this logic, legislators of single member district have strong incentive to bring benefits to their constituency.

Second, legislators face large intra-party competition when they pursue

reelection. They need to compete with local politicians when they pursue nomination in party. In the last several legislative elections, the major parties, KMT and DPP, conducted primaries in which 70% was based on citizen surveys and 30% on closed primary vote.5 Party leaders have some limitation in deciding the nominees even though popular party leaders may have some impact on nomination. Because the new district is lowered down to a township level, the district of a legislator may be

overlapped with those of the local representatives and local executive officials. When they run in primaries, challengers might come from local politicians who have built close patron-client relationship with their constituents. To compete with these powerful politicians, legislators have a strong incentive to exploit the position and power of legislators to provide particularistic benefits to constituency so as to pave the way for re-election.6

Furthermore, to run a single member district, legislators need to get more than 50 percent of votes to be elected. This means that legislators need to please more than a half of constituents to be elected. This may lead them centripetal in issue positions, or take a vague position in controversial issues (Cox 1990). Given this, legislators have an intention to play a safe game: they serve constituents and introduce particularistic benefits to constituents, rather than take a clear position in an ideological or

controversial issue.

5 Whereas the 70% based on citizen surveys previously included a national sample, the DPP chose in

2008 to exclude those identifying as leaning blue (KMT) from the survey.

6

When legislative assistants were asked (in 2009) whether legislators face greater or smaller intra-party competition when they pursue reelection? About 55.4 percent of assistants thought that legislators face greater intra-party competition. In addition, about 20.7 percent thought that legislators face similar intra-party competition as before. In contrast, only 23.9 percent thought that legislators face less intra-party competition.

16

Given above reasons, two major hypotheses are developed as follows:

H1. Legislators under a SMD system tend to provide more constituency services than those under an SNTV system.

H2. Legislators under a SMD system tend to introduce more particularistic interest bills than those under an SNTV system.

In a single member district, there are usually two major candidates per district. Candidates need to get more than 50 percent of votes to be elected. To get more than 50 percent of votes, they have to count on party vote besides personal vote.

Therefore, inter-party competition is inherently large.7 Large inter-party competition suggests that the other party’s victory might pose a great threat to the political lives of legislators’ themselves (Sheng 2008). Since co-partisan share the same fate of election, legislators have incentive to be cohesive to shape a good party image in elections and in the legislature (Cox and McCubbins 1993). Therefore, one hypothesis is developed as follows:

H3. Legislators under a SMD system have a higher incentive to be cohesive than those under an SNTV system.

However, there is often conflict between constituency and party. It is very often that these conflicts result from the limitation of legislators’ time and resources. When they put more time and resource in constituency, they necessary have less left to put in the party affairs. Occasionally, these conflicts are obvious when parochial interests contradict with party interests. When legislators face a potential conflict between constituency and party, they will try to avoid conflict first, and not let the conflict amplify. Sometimes, conflict will be dealt behind the scene. If the conflict is not avoidable, then legislators may be on the constituency side. After all, constituents are the subjects who cast the ballots and the subjects who legislators are responsible. Therefore, I expect that:

7

When legislative assistants were asked (in 2009) whether legislators face greater or smaller inter-party competition when they pursue reelection? About 52.2 percent of assistants thought that legislators face greater inter-party competition. In addition, about 31.5 percent thought that legislators face similar intra-party competition as before. Relatively, only 15.2 percent thought that legislators face smaller inter-party competition. In addition, only 1.1 percent thought that legislators face small inter-party competition as usual.

17

H4. When there is a conflict between constituency and party, legislators under a SMD system tend to be more on the constituency side than those under an SNTV system.

Data and Empirical Evidence

The following analysis is based on three databases. The first data source is a series of surveys on legislative assistants collected from 1998 to 2009. These surveys were conducted in order to uncover the legislative styles and orientations of legislators through the viewpoints of observers. Those respondents were senior staffs that had worked for their respective legislators for many years and were thus quite familiar with the legislators. Three of the five surveys were collected before the reform, while the other two surveys were collected after the reform. The first four surveys were collected in the end of the term, about one to two months before the election day of the next term. The fourth survey was collected in 2007, before the election first using the new electoral system. However, because legislators were reelection-oriented and future-oriented, they have already faced and behaved under a new electoral system. The last survey was collected in the end of 2009, the middle of the term.

The second data source is all bills introduced by individual legislators from 2001 to 2009. The total number of bills is 4,415. A content analysis was conducted to analyze: (1) Whether the bills were particularistic or national concern, and whether they were to provide interests or put on sanctions? (2) Whether the bills were

introduced by legislators from the same party or cross parties (or blocs)? The results in different periods of time provide an opportunity to compare legislators’ incentives of initiating bills before and after the reform.

Third data source is all roll call votes from 1996 to 2007. The roll call votes were collected to uncover the trend of party cohesion. All data were collected in a

longitudinal way so that it is able to compare legislators’ incentives before and after the reform. In addition, some intensive interviews were conducted to know the insider information and verify some results of the quantitative analysis.

Constituency Services

18

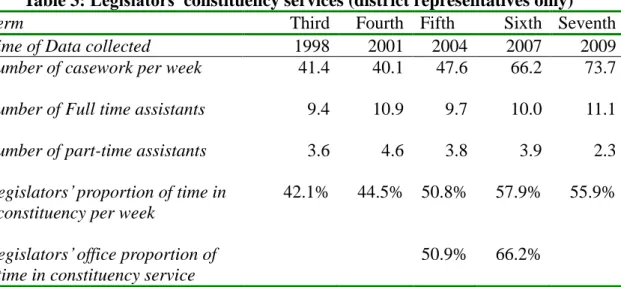

serve their constituents to get personal vote (Hawang 1994; Sheng 2000, 2001a). Legislators pursuing a personal vote tend to build patron-client relationship with their constituents. Legislators provided constituency services in ordinary times in exchange for the support of the constituents at the election time (Kitschelt and Wilkinson 2007). Serving the constituency rather than focusing on public policy is an easy way to take credit in an executive controlling the public policies. From results of the Table 3, both the legislators in 1998 and 2001 had an average about 40 pieces of casework per week. The average number was raised to 47.6 pieces in 2004. Furthermore, in a new

electoral system, legislators had an even higher incentive to conduct casework. The average number of casework increased sharply from about 20 pieces and attained to 66.2 pieces in 2007 and 73.7 pieces in 2009. This means that legislators on average conducted 10 pieces of casework every day. Besides, both legislators and his/her office put more time in constituency services after the reform. Legislators spent about 60% of time in constituency, and legislators’ offices put around two-third time in constituency services.

[Table 3 about here]

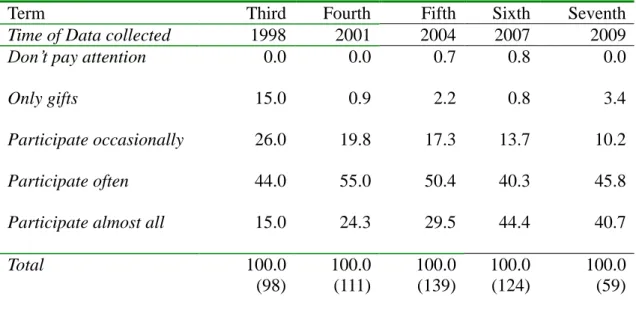

The emphasis of constituency services can also be observed from legislators’ attitudes towards invitations of wedding and funeral ceremonies from their

constituents. To attend ceremonies is the most common way of casework in Taiwan (Hawang 1994). From Table 4, before the reform, around 50 percent of legislators attended often when they were invited to weddings and funeral ceremonies, and around 30 percent of legislators attended almost all ceremonies when they were invited. After the reform, legislators even more attended to ceremonies. Around 40 percent of them almost attended to all ceremonies. This figure was even greater than previous periods. A senior legislative assistant explained for me:

To invitations of wedding and funeral ceremonies from constituents, we might shirk in past days. However, now… if you do not show up in ceremony but your competitor does, then you are going to lose those votes in the ceremony.

In addition, to the legislators who serve both in the Fifth and the Sixth

Legislative Yuan (2002-2007), I asked their assistants to locate their positions on a continuum, with most focus on constituency services 0, and most focus on legislation 10, in the Fifth Legislative Yuan and in the Sixth Legislative Yuan respectively.

19

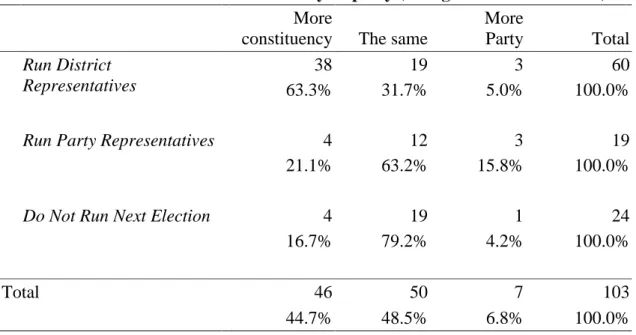

Then I compare two locations for each of the legislators and categorized legislators into three categories: more focus on constituency services, the same, and more focus on legislation. The result has shown in Table 5. It is obvious, for the legislators who were going to run in SMDs in the next election, about three quarters of them focused more on constituency services. In contrast, only 3.4% of them focused more on legislation.

[Table 4 about here] [Table 5 about here]

Besides the quantity of constituency services increasing, a senior assistant told me that the types of constituency services were numerous. Some trivial matters which legislators did not deal with before, they willingly conducted after the electoral reform. That is because the area of their district is reduced to a township level, and it is natural to have many trivial matters in local politics. For example, a legislators’ assistant told that he was busy to find a missing dog for a constituent one day and he asked electric power company to move the electricity box from the neighborhood of his constituents several times a week. Sunday morning, he had to get up early to say goodbye to his constituents’ tour travel. According to his observation in the Seventh Legislative Yuan, he was not the only one who spent much more time and energy in serving constituents. This shows that when the area of the electoral district decreases, legislators need to deal with trivial matters to build close relationship with their constituents. All of this may lead legislators parochial oriented rather than national oriented, and run-errands oriented rather than policy oriented.

In summary, legislators under a single member district tend to provide more constituency services than those under an SNTV system. This has verified the first Hypothesis.

Legislators’ Introduced Bills

To identify the characteristics of bills introduced by legislators, I classify bills into seven categories according to two criteria: First, is the bill related to diffuse or general interests or is it related to a narrowly constituted, organized or unorganized

20

group of people? Second, does the bill involve interests or sanctions? The seven categories are as followings:8

(1) Particularistic interest bills: bills which provide special interests to a particular group of people, district, or occupation.

(2) Particularistic sanction bills: bills which impose regulatory or financial burdens on a particular group of people, district, or occupation.

(3) Particularistic mixed-interest/sanction bills: bills which benefit some people and sanction the same group of people or sanction another group of people at the same time.

(4)General interest bills: bills which provide interests to all people in the whole country.

(5) General sanction bills: bills which impose regulatory or financial burdens to all people in the whole country.

(6) General mixed-interests/sanction bills: bills which benefit and sanction all people in the country at the same time.

(7) Neutral bills: bills which do not involve interests or sanctions.

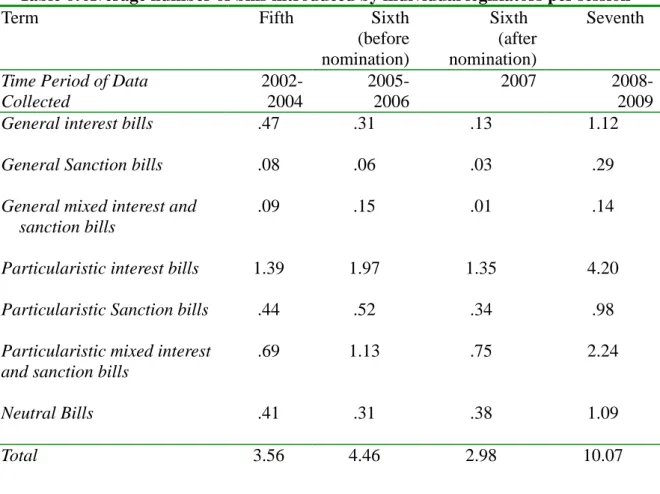

Table 6 shows the average number of bills individual legislators introduce per session. The data in the Sixth Legislative Yuan were shown before and after the nomination. The most noteworthy message in Table 6 is that the average number of the particularistic interest bills is much greater than that of other categories of bills in all periods of time. It is obvious that legislators have a clearly parochial concern: they

8

Notice that I classify bills based on the content of the bills rather than on the legislation. This is because there is always more than one bill considered in the same legislation. For example, in the Fifth Legislative Yuan, around 30 bills were considered in the legislative process for the “Provisional Statue for Welfare and Sustenance Allowance for Showing Respect to the Aged”. Some bills specified that one particularistic group, such as aged 65 years or older government employees or educational personnel who have received endowment insurance payments, would get a monthly pension of NT$3000. Some bills specified that aboriginal people aged 55 years or older would get a monthly pension of NT $3000. Some bills raised the monthly pension to NT$10000. These bills benefiting some particularistic groups of people are classified as particularistic benefits bills. Another example, if a revision benefits some group of people, and deprives some group of people (the same group or different group) at the same time, it is classified as a particularistic mixed-benefit/sanction bill.

21

tend to introduce particularistic interest bills instead of general interest bills. Two major reasons account for this phenomenon. First, general interest bills provide public goods to everyone in the whole country so that relatively few people care who

provides these public goods. It is not easy for legislators to count on this legislation to build close relationships with the beneficiaries. Second, legislators involved in

passing general interest legislations need to spend much time and resources.

However, most legislators have an average of only about 14 personal staff members, with an average of 10 full-time assistants (about 4 dealing with legislation) and 4 part-time assistants. Given the limited time and resources they possess, most

legislators prefer to adopt a free-ride strategy. Sheng (2006) focuses on the legislators of the Fifth Legislative Yuan and finds that approximately half of all

legislators-introduced bills are only one article, and two-thirds of them are three or less than three articles. Legislators may sometimes introduce a narrowly-scope and few-article bill and wait others (especially the executive branch) to introduce a complete bill. It is very often that they introduce a bill with a slight revision that brings particularistic benefits to their constituents and claim credits for this revision.

[Table 6 about here]

It is understandable that legislators avoid introducing sanctioning bills because people bearing the burden created by the bill will remember who was responsible. Even though constituents easily forget, the legislator’s foes don’t forget and will remind the constituents at election time. Consequently, the legislator may be involved in a hard battle in the future elections. Therefore, legislators tend to avoid introducing sanctioning bills. If they cannot avoid this, they may introduce mixed bills, that is, depriving some people and benefiting some people at the same time. In this way, they may avoid infuriating their constituents because they not only sanction, but also benefit them. In other situations, even though they may infuriate some groups of people, they please other group of people at the same time.

Comparing the bills introduced in the first period, the second period of the Sixth Legislative Yuan, and the Seventh Legislative Yuan, we may find that the impact of electoral reform has a delay effect. The reason for this delay impact on legislators’ introduction is because legislators focus more on their election and constituency

22

services in the last two sessions. Comparing legislators in earlier periods, legislators of the Seventh Legislative Yuan have an even higher incentive to introduce bill, they introduce more than 10 bills per session. It is much greater than the number of bills in the fifth Legislative Yuan and sixth Legislative Yuan. The impact of the electoral reform on legislators’ introduction is quite obvious. It has verified the second

hypothesis, that is, legislators under SMD have an even higher incentive to introduce particularistic interest bills than the legislators under the SNTV system.

Party Cohesion

As mentioned, legislators facing SMD have an incentive to build close relationship with constituents. They put more time and resources in constituency, conduct more casework, and introduce bills more actively to provide particularistic benefits to their constituents. An interesting question deserves to be answered: Are legislators more centripetal to or centrifugal from their party when they are more constituency-oriented?

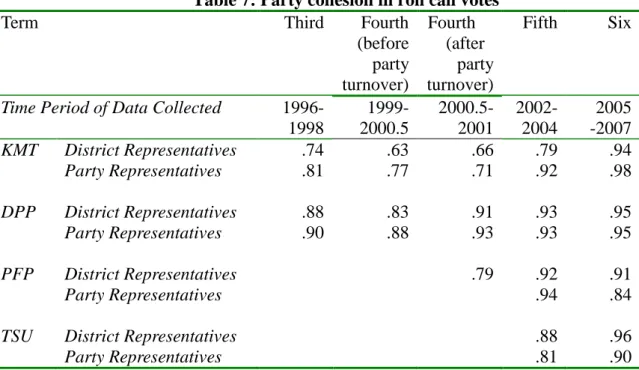

Since there is only a single candidate to run in a district in a party, the party label is more important for the fate of legislators’ election than before. Therefore,

co-partisan legislators have an incentive to be cohesive to build the party reputation under the new electoral system. In Table 7, we may find that the party cohesion in the Sixth Legislative Yuan was at a high level. The most important is that KMT district representatives attained a much higher level of party cohesion than previously. This may be partly attributed to the electoral reform. However, the high level of party cohesion could not be entirely attributed to the electoral reform because the party cohesion has already in a high level before the reform, especially for DPP and PFP legislators. Because the high level of cohesion in roll call votes has occurred before the electoral reform, other information besides roll call votes will be useful to confirm the high cohesion because of the electoral reform.

[Table 7 about here]

Since a legislator-introduced bill requires at least one major author and joint sponsors of no less than a quorum, we may observe the party combination of the major authors and sponsors to measure party cohesion. Notice this quorum has been

23

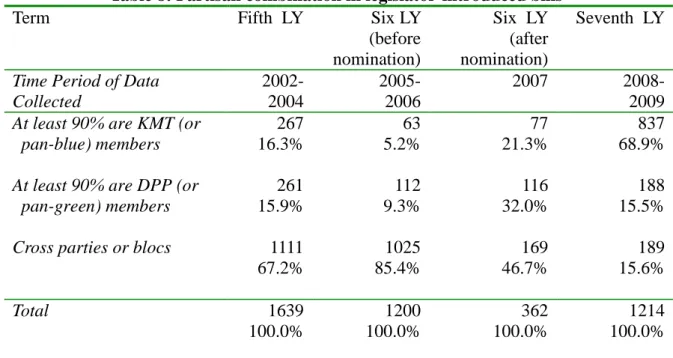

lowered from 30 to 20 in the Seventh Legislative Yuan because of the total number of legislators was cut into a half. Table 8 shows the party combination of

legislators-introduced bills during different periods of time. We may find the dramatic change across periods. In the Fifth Legislative Yuan, most legislator-introduced bills were introduced with coauthors and sponsors across parties (or blocs). A low percent of legislators’ bills were clearly partisan: only about 15 percent of legislator bills were jointly sponsored by at least 90 percent KMT (or pan-blue) legislators. Also, only about 15 percent of legislator bills were jointly sponsored by at least 90 percent DPP (or pan-green) legislators. In contrast, approximately 70 percent of

legislators-introduced bills were introduced with sponsors across parties and blocs. This shows that the legislators’ bills were usually nonpartisan before the electoral reform. This non-partisan characteristic continued in the first period of the Sixth Legislative Yuan. One reason for this nonpartisanship was that legislators evaded party ideology and tended to provide specific benefits to constituents. Also, they tried to broaden their cosponsor list to different parties and blocs so that the bills might have a better chance to be considered and passed (Sheng 2006).

[Table 8 about here]

However, starting approximately from the second period of the Sixth Legislative Yuan, during the period that legislators campaigned for the next election, co-partisan legislators cooperated to introduce bills. This is because under an SMD system, co-partisan legislators shared the same electoral fate. They thus had a higher intention to introduce bills with their co-partisans so as to build a party reputation. Around 50 percent of legislators’ bills were introduced by legislators with the co-partisans (or bloc). The tendency is even more salient in the Seventh Legislative Yuan. About 85 percent of legislators’ bills were co-partisan, with KMT 68.9% and DPP 15.5%.

This has verified Hypothesis 3; that is, legislators under a SMD system tend to be more cohesive than those under an SNTV system.

Constituency-Party Conflict

Legislators may encounter difficulties when their party and constituency have conflicts. These conflicts may result from the fact that legislators’ time and resources

24

are limited. When they put more time and resource in constituency affairs, they are necessary have less left to the party affairs. Occasionally, these conflicts are obvious when parochial interests contradict with national interests. For example, when legislators pursue parochial interests for their constituencies may endanger the party image and reputation. When legislators face a potential conflict in constituency and party, they may try to avoid first, and do not let the conflict amplify. Sometimes, conflict is able to be dealt behind the scene. However, if the conflict is not avoidable, then legislators may be on the constituency side. Some evidence shows as follows.

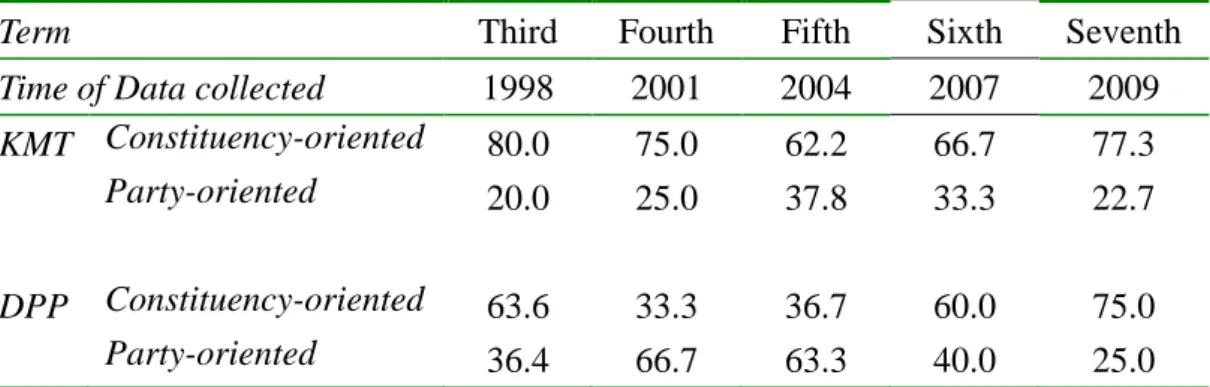

From the Third to the Seventh Legislative Yuan, I asked the legislators’ assistants: “When the legislator you worked for faces conflicting pressures from his/her party and constituency, which side do you think he/she will take?” The research findings have shown in Table 9. In Table 9, we may find that KMT and DPP legislators have different patterns of constituency-oriented or party-oriented before the electoral reform. But after the reform, the patterns become identical. Before the reform, the trend of KMT legislators was increasing party-oriented and decreasing

constituency-oriented because of the intense inter-party conflict. Intense inter-party conflict strengthened party cohesion because other party’s victories posed a greater threat to individual legislators’ political lives (Sheng 2006). In contrast, when the DPP stood as an increasing established opposition party in the 1990s, its legislators needed the party reputation to garner votes because most DPP legislators were short of local connections as their KMT colleagues. Therefore, DPP legislators were party-oriented before the reform. However, after the reform, legislators of both parties have become much more constituency-oriented. In the Sixth Legislative Yuan, more than 60 percent of legislators were constituency-oriented. Furthermore, in the Seventh Legislative Yuan, more than 75 percent of legislators were constituency-oriented.

[Table 9 about here]

Furthermore, I will verify that the dramatic transformation of legislators’

constituency-orientation does not because of different legislators across terms. For the legislators who serve both in the Fifth and the Sixth Legislative Yuan, I asked their assistants to locate their positions on a continuum, in the Fifth and the Six Legislative Yuan respectively, when there is conflict between constituency and party, with 0 as

25

strongly siding with the constituency position 0, and 10 strongly siding with the party position. Then I compare two locations for each of the legislators and categorized them into three categories: care more about constituency position, the same, and care more about party position. The result has shown in Table 10. It is obvious, for the legislators who are going to run in SMDs in the next election, more than 60 percent of them more care about constituency position. In contrast, only 5% of them more care about party position, with around 30 percent of them viewing both the same.

[Table 10 about here]

In the same way, I asked them when there is limitation in time and resources, whether legislators will priority use in constituency affairs or party affairs in the fifth term and the sixth term respectively? Again, legislators were categorized into three categories: more constituency affairs, the same, and more party affairs. The result has shown in Table 11. It is obvious, for the legislators who are going to run district representative in the next election, around three quarters of legislators put time and resources more on constituency, about one quarter of legislators the same, and only one legislator put more time and resource in party. Given the above evidence, when there is conflict in constituency and party, legislators under a SMD system tend to be more on the constituency side than those under an SNTV system. It has verified the hypothesis 4.

[Table 11 about here]

Party’s Response to Constituency-Oriented Legislators

Previous evidence has shown that legislators are constituency-oriented in the SNTV system, and this orientation has been reinforced after the reform of electoral system. To constituency-oriented legislators, party leaders most of time fully

understand and consider it into policy-making. Being leaders of legislative coalition, party leaders need to provide legislators with sufficient incentives to avoid legislators’ free riding. Following is a case to show party leaders’ consideration and

leader-legislator compromise.

26

than 70 percent of seats, while DPP has less than 25 percent of seats. KMT party leaders know quite well that its legislators have incentives to serve the constituency and have motives to free ride on the party’s performance. However, leaders need legislators to pass legislation to establish good party reputation. Therefore, the leaders set up the following institutions for KMT legislators’ attendance in meetings and roll call votes: (1) KMT legislators take turns attending the meetings and roll call votes. Each time a half of KMT legislators attend to the meetings and votes. (2) KMT legislators are assigned to attend before the meeting. If they are absent from the meeting, they will be punished by party discipline. (3) An individual legislator is allowed to exchange attendance date with other legislator if the issue discussed or the roll call vote contradicts with the interest of his /her constituents. In this way,

legislators can fulfill his duty to be a party member and a representative of constituency at same time. The party leaders fulfill their political goals to achieve legislation and establish party reputation, and also fulfill legislators’ desire of constituency services.

Conclusion

What do my findings tell us about the triangles among constituency, party and legislators? First of all, legislators’ representative behavior is affected by the electoral system. Taiwan’s electoral reform in 2005 provides a rare opportunity to examine how the electoral reform changes legislators’ electoral calculations and representative behavior. In this paper, I have shown that Taiwanese legislators under a new system are more particularistic and localized than those under the old system. This is so because legislators need to garner votes by themselves, and they easily claim credits and hardly avoid constituent’s blames. Also, legislators face large intra-party competition when they pursue nomination within party. Furthermore, legislators need to get more than 50 percent of votes so that they have an incentive to move centripetally in issue positions or take a vague position in controversial issues. Legislators thus have strong incentives to exploit the position and power of legislators to provide particularistic benefits to constituency so as to pave the way for reelection.

Second, when legislators are more particularistic and localized, they are not necessarily more likely to deviate from their party. On the contrary, legislators have

27

incentives to stand together with their partisans to establish party reputation. This is because legislators under an SMD face large inter-party competition and party label is important for their own political life.

Third, besides the electoral system, I find that intra-party and inter-party politics bring important impacts on legislators’ behavior. If legislators face greater intra-party competition, they have strong incentives to establish a personal vote. In contrast, if legislators face greater inter-party competition, they have strong incentives to establish a party vote. Of course, the inter-party and intra-party politics may partly shaped by the electoral system. However, they are also shaped by the political history of a country, the inherent political culture and habit of a party, and the relative

strength among different parties. Without fully considering the party politics, we may not explain why legislators under the same electoral system behave in different ways. In conclusion, the electoral system matters, but the intra-party and inter-party politics matters too.

28

References

Ames, Barry. 1995. “Electoral Rules, Constituency Pressures, and Pork Barrel: Bases of Voting in the Brazilian Congress.” The Journal of Politics. 57 (2): 324-343. Ames, Barry. 2002. “Party Discipline in the Chamber of Deputies.” In Scott

Morgenstern and Benito Nacif. eds. Legislative Politics in Latin America. Cambridge University Press.

Amorim Neto, Octavio and Fabiano Santos. 2003. “The Inefficient Secret Revisited: The Legislative Input and Output of Brazilian Deputies.” Legislative Studies

Quarterly 28 (4): 449-479.

Arnold, R. Douglas. 1990. The Logic of Congressional Action. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Batto, Nathan F. 2005. “Electoral Strategy, Committee Membership, and Rent

Seeking in the Taiwanese Legislature, 1992-2001.” Legislative Studies Quarterly 30(1): 43-62.

Cain, Bruce, John Ferejohn, and Morris Fiorina. 1984. “The Constituency Service Basis of the Personal Vote for U. S. Representatives and British Members of Parliament.” The American Political Science Review 78: 110-125.

Cain, Bruce, John Ferejohn, and Morris Fiorina. 1987. The Personal Vote:

Constituency Service and Electoral Independence. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard

University Press.

Carey, John and Mathew S. Shugart. 1995. “Incentives to Cultivate a Personal Vote: A Rank Ordering of Electoral Formulas.” Electoral Studies 14: 419-439.

Cox, Gary. 1987. The Efficient Secret: The Cabinet and the Development of Political Parties in Victorian England. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press. Cox, Gary. 1990. “Centripetal and Centrifugal Incentives in Electoral Systems.”

Electoral Studies 10:118-132.

Cox, Gary W. and Mathew D. McCubbins. 1993. Legislative Leviathan: Party

29

Crisp, Brian et.al. 2004. “Vote Seeking Incentives and Legislative Representation in Six Presidential Democracies.” The Journal of Politics 66( 3): 823-846. Evans, Diana. 2004. Greasing the Wheels: Using Pork Barrel Projects to Build

Majority Coalition in Congress. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fiorina, Morris. 1980. “The Decline of Collective Responsibility in American Politics.” Daedalus 109: 25-45.

Fiorina, Morris. 1989. Congress: Keystone of the Washington Establishment. Second edition. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Fukui, Haruhiro and Shigeko N. Fukai. 1996. “Pork Barrel Politics, Networks, and Local Economic Development in Contemporary Japan.” Asian Survey 36 (3): 268-286.

Heitshusen, Valerie, Garry Young and David M Wood. 2005. “Electoral Context and MP Constituency Focus in Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom.” American Journal of Political Science. 49 (1): 32-45. Hirano, Shigeo. 2006. “Electoral Institutions, Hometowns, and Favored Minorities:

Evidence from Japanese Electoral Reforms.” World Politics 58: 51-82. Ho, Szu-Yin Benjamin. 1986. "Legislative Politics of the Republic of China:

1970-1984." Dissertation of University of California, Santa Barbara.

Jacobson, Gary C.1992. The Politics of Congressional Elections. Third edition. Boston: Little, Brown, and Company.

Hawang, Shiow-Duan. 1994. Constituency Services: The Basis of Re-election for the

Legislators. Taipei: Tang-Shan.

Hawang, Shiow-duan. 2003. “The Predicament of Minority Government in the Legislative Yuan.” Taiwanese Political Science review 7 (2): 3-49.

Kingdon, John W. 1989. Congressmen’s Voting Decisions. Third edition. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press.

Kitschelt, Herbert and Steven I. Wilkinson. 2007. “Citizen-Politician Linkage: An Introduction.” In Herbert Kitschelt and Steven I. Wilkinson. eds. Patrons, Clients, and Policies. Cambridge: The Cambridge University Press. pp. 1-49.

30

International Political Science Review 7 (1): 67-81.

Lancaster, Thomas D. and David Patterson. 1990. “Comparative Pork Barrel Politics: Perceptions from the West German Bundestag.” Comparative Political Studies 22: 458-477.

Luor, Ching-jyuhn. 2001. Distributive Politics in Taiwan. Taipei: Avanguard Publishing Company.

Luor, Ching-jyuhn. 2004. “The Political Analysis on the Decision-Making of Distributive Policies and Budgets.” Political Science Review 21: 149-188. Lour, Ching-jyuhn and Ying-Shih Hsieh. 2008. “The Association of District Size and

Pork Barrel Related Bills Initiated by Legislators: An Analysis on the 3rd and 4th Legislative Yuan in Taiwan.” Public Administration & Policy 46: 1-48.

Luor, Ching-jyuhn and Chien-liang Liao. 2009. “The Impact of Upcoming Changes in the Electoral System on the Initiation Behavior of Pork Barrel-related Bills from Legislators.” Taiwanese Political Science Review 13 (1): 3-53.

Mayhew, David. 1974. Congress: The Electoral Connection. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

McKean, Margaret and Ethan Scheiner. 2000, Japan’s New Electoral System: la plus ca change …” Electoral Studies 19:447-477.

Norris, Pippa. 2004. Electoral Engineering: Voting Rules and Political Behavior. Ramseyer, J. Mark and Frances McCall Rosenbluth. 1993. Japan’s Political

Marketplace. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Sheng, Shing-Yuan. 1996. “Electoral Competition and Legislative Participation: The Case of Taiwan.” Dissertation of University Michigan.

Sheng, Shing-Yuan. 1999. “Representative Behavior of Taiwan’s Legislators.” Research Project supported by the National Science Council in Taiwan. Project ID: NSC88-2414-H-004-023.

Sheng, Shing-Yuan. 2000. “Law-Making and Constituency Service: A study on representative Behavior of Taiwan’s Legislators Elected in 1995.” Journal of

Electoral Studies 6 (2): 89-119.

31

Representative Orientations and Representative Behavior of Taiwan Legislators.”

Journal of Electoral Studies 7 (2): 37-70.

Sheng, Shing-Yuan. 2001b. “Representative Behavior of Taiwan’s Legislators.” (III) Research Project supported by the National Science Council in Taiwan. Project ID: NSC89-2414-H-004-057.

Sheng, Shing-Yuan. 2003. “Representatives and Representative Institutions.” Research Project supported by the National Science Council in Taiwan. Project ID: NSC92-2414-H-004-019.

Sheng, Shing-Yuan. 2005. Constituency Representative and Collective Representative: The Representative Roles of Taiwanese Legislators.” Soochow Journal of

Political Science 21:1-40.

Sheng, Shing-Yuan. 2006. “The Personal Vote-Seeking and the Initiation of Particularistic Benefit Bills in the Taiwanese Legislature.” Legislatures and Parliaments in the 21th Century Conference, Soochow University, Taiwan. Sheng, Shing-Yuan and Shih-Hao Huang. 2006. “Why does the Taiwanese Public

Hate the Legislative Yuan?” Taiwan Democracy Quarterly 3(3): 85-128. Sheng, Shing-Yuan. 2006-2009. “The Triangle among Constituency, Party, and

Legislators: A Comparison Before and After the Change of Electoral System,” Research Project supported by the National Science Council in Taiwan. Project ID: NSC95-2414-H-046-MY3.

Sheng, Shing-Yuan. 2008. “Party Leadership and Cohesion in the Legislative Yuan: Before and After the First Party Turnover in the Executive Branch.” Taiwan

Democracy Quarterly 5(4): 1-46.

Sheng, Shing-Yuan and Shih-Hao Huang. 2006. “Why does the Taiwanese Public Hate the Legislative Yuan?” Taiwan Democracy Quarterly 3(3): 85-128. Schugart, Mathew Soberg and John M Carey. 1992. President and Assemblies:

Constitutional Design and Electoral Dynamics. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge

University Press.

Stratmann, Thomas and Martin Baur. 2002. “Plural Rule, Proportional Representation, and the German Bundestag; How Incentives to Pork-Barrel Differ Across

32

Yu, Ching-hsin. 2005. “The Evolving Party System in Taiwan, 1995-2004.” Journal

33

Table 1: Taiwanese electoral system for legislators before and after reform

Old system New system

Total seats 225 113

Formula 168 from SNTV

49 from closed list PR 8 aboriginal representatives

73 from SMD

34 from closed list PR 6 aboriginal representatives

Magnitude of a district

One to ma

(m= magnitude of the district)

One

Area per district (number of population)

a county depending on the number of the

population

Number of eligible voters per district

four districts less than 200,000, 25 districts more than 200,000 the biggest district more than 1,200,000

most districts around 200,000 to 300,000

Percentage of votes to be elected

1/m percent of votes plus one vote

50 percent of votes plus one vote

Note: a. Four districts with one legislator because of small population in 2004 legislative elections.