Recreation conflict of participants in different mode of water-based activities and their adoption choice

Chung-Chi Wu, Ching-Tang James Wang, Hsiou-Hsiang Jack Liu, Wei-Ching Wang

Article information:

To cite this document: Chung-Chi Wu, Ching-Tang James Wang, Hsiou-Hsiang Jack Liu, Wei-Ching Wang. "Recreation conflict of participants in different mode of water-based activities and their adoption choice" In Advances in Hospitality and Leisure. Published online: 2009; 69-87.

Permanent link to this document:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S1745-3542(2009)0000005008 Downloaded on: 25 September 2014, At: 18:34 (PT)

References: this document contains references to 51 other documents. To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com

The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 121 times since NaN*

Users who downloaded this article also downloaded:

Charles A. Stansfield, (1964),"A note on the urban#nonurban imbalance in American recreational research", The Tourist Review, Vol. 19 Iss 4 pp. 196-200

Gordon Foxall, (1984),"The Meaning of Marketing and Leisure: Issues for Research and Development", European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 18 Iss 2 pp. 23-32

Stephen Calver, Wolf Vierich, Julie Phillips, (1993),"Leisure in Later Life", International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, Vol. 5 Iss 1 pp.

-Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by 388200 []

For Authors

If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information.

About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com

Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services.

Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation.

PARTICIPANTS IN DIFFERENT

MODE OF WATER-BASED

ACTIVITIES AND THEIR

ADOPTION CHOICE

Chung-Chi Wu, Ching-Tang James Wang,

Hsiou-Hsiang Jack Liu and Wei-Ching Wang

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this article is to explore the three types of water-based recreationists’ (nonmotorized, motorized, and dual participants) percep-tion on recreapercep-tion conflict as well as their use of coping mechanisms and further understand the influence of specialization level on their choice of coping mechanism. Recreationists were divided into three groups based on the concept of experience use history. Data were collected between June and September 2007 at entry of five intra-site water recreation areas with every five individuals selected. Study findings partly supported the predictive relationships. Among all three groups (motorized, nonmotor-ized, and dual participants), less conflict was reported for nonmotorized participants than motored participants. Moreover, the data also suggest that coping mechanisms are widely employed in outdoor recreation. Implications for future research and practice were discussed.

Advances in Hospitality and Leisure, Volume 5, 69–87 Copyright r 2009 by Emerald Group Publishing Limited All rights of reproduction in any form reserved

ISSN: 1745-3542/doi:10.1108/S1745-3542(2009)0000005008

69

INTRODUCTION

Within limited resources, the rapid growth of demand for outdoor recreation has caused an increasing use level. When participants in different activity groups interacted, conflict may occur (Lee, 1997; Joan, 2002). Perception of crowding or conflict may highly influence on the overall satisfaction of recreationists. Since providing opportunities for quality outdoor recreation experiences and still preserving resources concern issues for park managers, conflict problems between users are gaining manage-ment attention (Todd, 1993). Although intensive and fundamental recrea-tion conflict research and management were issued in the past few decades (Schneider, 2000;Manning & Valliere, 2001), conflict problems still occur, especially when various and technology-advanced recreation activities are introduced. This could be an impediment to enhance the quality of outdoor recreation experiences and management ability.

The asymmetrical phenomenon in recreation conflict has been revealed in conflict-related researches, especially between traditional and new-techno-logical activities and between nonmotorized and motorized activities (Adelman, Heberlein, & Bonnicksen, 1982;Vaske, Carothers, Donnelly, & Baird, 2000;Vaske, Dyar, & Timmons, 2004). Although a few studies have also noted the potential for in-group conflict resulting from recreationists engaging in the same activity (Vaske et al., 2000; Thapa & Graefe, 2004), conflict between different activities is receiving more attention. Out-group conflict was obviously found in much research by exploring behaviors of participants in two different types of activities.

Out-group related researches often divided individuals into two groups (e.g. hiker vs. mountain-biker or skier vs. snowboarder). This can introduce problems in understanding conflict (Watson, Zaglauer, & Stewart, 1996;

Carothers, Vaske, & Donnelly, 2001) because many recreationists partici-pate in multiple activities. To segment recreationists in a more objective way, the concept of experience use history (Schreyer, Lime, & Williams, 1984;

Manning, 1999) has been demonstrated in past studies to be an important concept to employ in categorizing customers, especially recreationists. In this study, experience use history (EUH) was used in categorizing respondents into three groups: nonmotorized, motorized, and dual participants.

To manage outdoor recreation conflict and maintain the quality of outdoor recreation experiences, education and zoning are two general strategies recommended (Carothers et al., 2001;Manning, 1999). Another way to remain relatively high visitor satisfaction even when conflict occurs is

the adoption of coping mechanisms (Schneider & Hammitt, 1995). In

Manning’s (1999) review and synthesis of the literature on coping in outdoor recreation, it is suggested that displacement, rationalization and product shift are three primary coping mechanisms utilized by outdoor recreationists.

The purpose of this article is to explore the three types of water-based recreationists’ (nonmotorized, motorized, and dual participants) perception of recreation conflict as well as their use of coping mechanisms. A goal also understands the influence of specialization level on adoption of coping mechanisms. To achieve the goals of the research: (1) recreationists are divided into nonmotorized, motorized, and dual participants based on the concept of experience use history; (2) difference among these three groups regarding recreation conflict and their adoption of selected coping mechanisms are examined; and (3) influence of specialization level on choice of coping mechanism is examined.

Recreation Conflict

Although recreation related conflict has been extensively studied, ‘‘there has never been agreement on how recreation conflict should be measured’’ (Watson, 1995, p. 237). A single item of question was used in some studies to measure perceived conflict (Ramthun, 1995;Wang & Dawson, 2000). Others have examined the extent to which respondents find encounters with other recreationists to be desirable or undesirable or examined whether there is any goal or enjoyment interference (Thapa & Graefe, 2004; Watson, Williams, & Daigle, 1991; Watson, Niccolucci, & Williams, 1994). There are studies focusing on normative beliefs about unacceptable behaviors measured with multiple items of questions (Vaske et al., 2000, 2004;

Vaske, Needman, & Cline, 2007;Carothers et al., 2001;Vitterso, Chipeniuk, Skar, & Vistad, 2004). Generally speaking, multiple items of questions can avoid possible error caused by single-item measurement.

Recreation conflict can be divided into in-group and out-group conflict. Although some investigations have explored in-group recreation conflict, which occur among individuals engaging in the same activity (Vaske et al., 2000; Thapa & Graefe, 2004), literature of conflict has generally shown that out-group conflict was more obvious because recreationists are more intolerant of individuals participating in different activity with themselves than those in the same one (Jackson & Wong, 1982; Gibbons & Ruddell,

1995;Vaske et al., 2000). Out-group recreation conflict is often asymmetrical. Participants in one activity may object to the behavior of participants in another activity, but the reverse is not to the same degree. Asymmetrical conflict often occurs between traditional and new-technological activities or nonmotorized and motorized activities such as skiers and snowboarders (Vaske et al., 2000, 2004); paddling canoeists and motorboaters (Adelman et al., 1982), oar-powered and motor-powered whitewater rafters (Shelby, 1980), and hikers and mountain bikers (Ramthun, 1995;Carothers et al., 2001).

Coping in Outdoor Recreation

Coping is generally defined as ‘‘any behavior, whether deliberate or not, that reduces stress and enables a person to deal with a situation without excessive stress’’ (Sutherland, 1996). In outdoor recreation, a number of coping mechanisms have also been identified. These include behavioral coping mechanism, displacement, and cognitive coping mechanisms such as rationalization and product shift. Although many studies have focused on the coping behavior triggered by problems of crowding, in the context of recreation conflict, recreationists may also adopt coping mechanisms to deal with conflict problems (Schneider & Hammitt, 1995). In some studies con-cerning water canoeing, it was found that the vast majority of respondents changed their pattern of use such by selecting different entry days or points due to increasing use level, litter, noise, and environmental impacts (Anderson, 1980;Anderson & Brown, 1984).

Among the three coping mechanisms, Displacement is a behavioral shift that involves spatial or temporal changes in use patterns in response to problems. Inter-site displacement is shifting from one recreation site to another. Intra-site displacement is shifting within a recreation site. Temporal displacement is shifting from one time period to another. Activity displacement is shifting from one activity to another are four patterns that may be used. In other words, displacement can manifest itself in multiple ways. Rationalization is the second coping mechanism suggested in outdoor recreation. Since recreation activities may involve a substantial undertaking of time, money, and effort investment, people can refuse to be easily disappointed. To reduce cognitive dissonance, some people report high levels of satisfaction to rationalize an experience that an objective observer would not classify as so highly satisfying. Finally, Product shift is another cognitive coping mechanism that involves in an altering of definition of the recreation opportunity to be consistent with the condition experienced.

Segmentation of Activity Group: Experience Use History

It is possible that as people are involved regularly in outdoor recreation activities, some of them engage in multiple activities. Recreationists who involve in more than one type of activity thus appear. This type of recreationist did not gain much attention in the past researches. There wasCarothers et al.’s (2001)investigation of hikers and mountain bikers. It was recognized in their study that conflict reported by dual participants was found consistently between the other two extremes. However, respondents were divided into dual participant if they have any experiences in both activities without considering their past experience or frequency of par-ticipation. Therefore, more objective ways need to be used for segmentation. To categorize customers or recreationists, the concept of experience use history (Schreyer et al., 1984;Manning, 1999) has been demonstrated in past studies to be an important concept. For example,Petrick, Backman, Bixler and Norman (2001)employed the concept of EUH as segmentation criteria to classified golfers. They found different behaviors among them based on the EUH classification.

Based on above review of previous researches, we advanced the following hypotheses:

H1. Different activity groups (motorized, nonmotorized, and dual

participants) make different evaluations of conflict.

H2. Different activity groups adopt different level of coping strategies.

Adoption of Coping Mechanisms and its Effecting Factor: Recreation Specialization

Recreationists may range from novelists to experts. In past few decades, many outdoor researches have shed lights on the construct of recreation specialization. This concept is used to distinguish both participants engaging in both a single activity and various typologies (Donnelly, Vaske, & Graefe, 1986;Miller & Graefe, 2000;Vaske et al., 2004).

Based on recreation specialization theory (Bryan, 1977;Ditton, Loomis, & Choi, 1992), it can be expected that those with well-developed skills, large investments, and more experience are less likely to make a displacement decision. Some studies have identified that level of past experience, frequency of participation, skill level, and monetary investment were important to

individuals’ willingness to make a displacement (Vaske, Donnelly, & Heberlein, 1980; Snow, 1980; Manfredo & Anderson, 1987; Hammitt, Backlund, & Bixler, 2004). Particular patterns of experience preferences are likely to have influence on recreationists’ willingness to make a displacement. For example, in a study concerning recreational fishing,Ditton and Sutton (2004) have identified the activity-specific motivations for fishing which might lead recreationists to be less willing to involve a shift from the original activity to another activity. The importance of fishing was negatively related to willingness to displace. Another study concerning the influence of activity importance and similarity on perception of recreation displacement for fishing activity, has shown that 95% of the participants were willing to fish in another but similar setting when the original place was not be available (Manfredo & Anderson, 1987). It is consistent with the findings of that compared to the group of fishing ‘‘regulars’’ or ‘‘insiders’’ who have a strong emotional attachment to a specific activity, ‘‘strangers’’ and ‘‘tourists’’ who could identify another outdoor activity or another place more easily. Special-ization could become useful in identifying recreationists’ affecting feelings toward a particular activity or place (Kuentzal & McDonald, 1992;

McIntyre & Pigram, 1992). Therefore, experienced or specialized participants may be less likely to identify another outdoor activity or place that would provide them with the same satisfaction or enjoyment.

On the other hand, there are studies that identify the positive relationship between level of experience and their displacement behavior. Vaske et al. (1980)found that more experienced recreationists can be more sensitive to any changes on the setting or activity, thus, they were likely affected by any change around recreational settings and tended to have displacement.

Schreyer and Lime’s (1984) findings suggested that individuals with more experience are more likely to engage in more problem-focused coping strategies such as displacement and avoidance. On the other hand, the knowledge base of experienced or expert recreationists would offer them more information about places for displacement. Hall and Shelby (2000)

found a higher proportion of displacers among highly experienced visitors as well as non-displacers among relative newcomers. Thus, more experi-enced recreationists are thought to perceive greater knowledge of alter-natives, but at the same time are more prone to be displaced (Havitz & Dimanche, 1997, 1999;Watson et al., 1991;Hammitt et al., 2004). They are more likely to have temporal or resource displacement. However, the rela-tionship was not significant. Anderson (1981) has suggested that the relationship between past experience and displacement of recreationists was not significant because of their attachment to a specific place. Therefore, the

actual influence of past experience on displacement behavior remains unclear although the relationship between the two was confirmed.

Another influence of specialization may be employing rationalization. For example,Heberlein and Shelby (1977) have found that people with higher investment in time, money, fees in a recreational trip might refuse to report dissatisfaction. While in another study (Manning & Ciali, 1980), respon-dents with small investment in their trip seem more likely to report unsatisfactory experience. These findings implied that individuals might try to change their perception for their experiences when facing unexpected problems, especially those involving more within an activity.

Based on above review of previous researches, we advanced the following hypothesis:

H3. Recreationists with high level of specialization will be more likely to

adopt coping strategies.

METHOD

Study Location and Sampling

The study reported in this paper was conducted at Kenting National Park, Taiwan. Kenting National Park, located at the southern tip of Taiwan is one of the most popular places for water-based activities, attracting millions of both domestic and foreign tourists every year. However, zoning that keeps powered boat activities away from powerless activities is not well implemented in this area. Multiple uses of a specific area by different types of activities could usually be observed. The most common water-based activities in Kenting are surfing, swimming, snorkeling, water scooter, and speedboat. Other types of activity such as fishing in a boat, wind surfing, are seldom seen here. Self-owned yachts and powerboats that could carry large numbers of people are not popular here. Therefore, in this case, we want to focus on only a few activities including motorized activities (water scooter and speedboat) and nonmotorized (surfing, swimming, and snorkeling) activities. Data were collected between June and September 2007. On-site surveys were distributed on randomly selected days (including three weekdays and two weekends) at entry of two intra-site water recreation areas and received at the exits. At the entry of recreation areas, every fifth individual was selected. Of the 700 surveys distributed on-site, 440 usable questionnaires were received (response rate ¼ 62.8%).

Measurement Segmentation of Recreationists

To segment recreationists in a more objective way, two questions including: (1) how many total times they participate in nonmotorized and motorized water-based activities last year, (2) how many total years they had participated in nonmotorized and motorized water-based activities, were used to divide respondents into nonmotorized, motorized, and dual participants. In order to account for various combinations of above questions, an index ratio was computed (Hammitt et al., 2004). An account for total score was computed for each recreationist by summing their years with the frequency last year of nonmotorized water-based activity participation and then divided into low and high groups on the median value of the sum. Medians were used as the bases of segmentation rather than means because of some outlier values for some extremely experienced recreationists. The same procedure was done for the years and frequency of motorized participants. Three combinations of low and high levels of EUH on motorized and nonmotorized were identified including:

Motorized participants (n ¼ 62): Recreationists with high scores in motorized and low in nonmotorized activities.

Nonmotorized participants (n ¼ 155): Recreationists with high scores in nonmotorized and low in motorized activities.

Dual participants (n ¼ 233): Recreationists with high scores in both motorized and nonmotorized activities and those with low scores in both kinds of activities.

Measurement of Conflict

Given the suggestion ofVaske et al. (2007)that more indicators of potential conflict problem situations are needed further exploration, prior to this study an open-ended question was asked for recreationists to identify potential conflict problems caused by motorized/nonmotorized water-based recreationists. Findings were induced into five specific items to ask if motorized/nonmotorized water-based recreationists: (a) made a lot of noise, (b) drove or played with unacceptable speed (too fast or slow), (c) cut others off, (d) were not keeping an adequate distance from others, and (e) made negative impact to environment. Respondents indicated how often these behaviors were seen on this trip. Response categories were: (1) never, (2) rarely, (3) sometimes, (4) frequently, and (5) almost always.

Measurement of Coping Mechanisms

The items contained in this part were asked to measure the number of coping mechanisms adopted by respondents in dealing with conflict on this trip. Items include a variety of questions designed to test for spatial and temporal displacement, rationalization, and product shift. These statements of coping behavior were adapted from previous studies (Hammitt & Patterson, 1991; Robertson & Regula, 1994; Manning & Valliere, 2001). Statements are shown inTable 4.

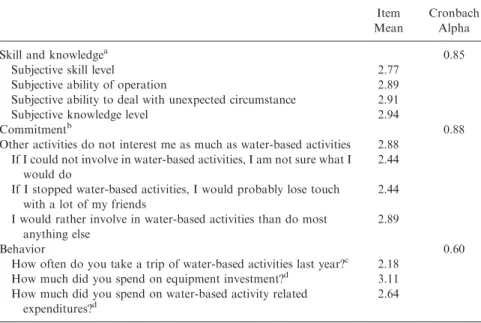

Measurement of Recreation Specialization

Measurement of recreation specialization was adapted from previous studies (Bricker & Kerstetter, 2000;Lee & Scott, 2004) with three dimen-sions. The first dimension, behavior, was addressed by asking respondents about the number of trips of water-based activities taken last year, their overall equipment investment and their overall water-based activity related expenditures. The second dimension, skill and knowledge, was addressed through four separate questions. Respondents were asked to rate their skill level, ability of operation, ability to deal with uncertain circumstance, and knowledge level. The final dimension, commitment, was measured using four questions employed by Lee and Scott (2004) to reflect the rejection of alternative activities and the costs associated with ceasing participation. All of these items were measured using a five-point response format.

Analysis

Analysis of study data was conducted on both descriptive and analytical levels. Descriptive findings indicate the categories of respondents as well as the level and type of coping mechanisms adopted by respondents. One-way analyses of variance were then used to compare the means of in-group and out-group recreation conflict by three kinds of recreationists. Linear regression analysis was used to determine the extent to which adoption of coping mechanisms is statistically related to place attachment and recreation specialization.

RESULTS

Of the 440 responses, about 86% of the respondents were under the age of 35 years and most of them were male (55.3%). Of the three types of

Table 1. Item Means and Reliability of the Conflict Scale. Item Mean Cronbach Alpha Normative beliefs about

Problem motorized participants behaviora 0.86

Made a lot of noise 3.22

Drove with unacceptable speed 3.33

Cut others off 3.38

Were not keeping an adequate distance 3.08 Had negative impact on environment 3.63

Problem nonmotorized participants behaviorb 0.80 Played with unacceptable speed 2.48

Cut others off 2.31

Were not keeping an adequate distance 2.40 Had negative impact on environment 2.79

aMeasured with Likert-type format, where 1 ¼ strongly disagree and 5 ¼ strongly agree. bMeasured on a scale, where 1 ¼ very bad and 5 ¼ very good.

respondents, dual participants had participated in their activities more frequently (M ¼ 6.6 per year) and longer (M ¼ 6.2 years) than had the other two groups. The average costs they invested in the equipment and related expenditures per year were about 63 and 107 USD, respectively. Participants of motorized water-based activity invested the most in their equipment (M ¼ 127 USD per year), while dual participants spent the most on related expenditures (M ¼ 150 USD per year).

The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of recreation conflict for both motorized and nonmotorized participants are above 0.80 (see Table 1). Cronbach’s alpha for the items in recreation specialization is given in Table 2. The alphas for skill and knowledge (0.85), behavior (0.60), and commitment (0.88) in recreation specialization are all above 0.60.

Adoption of Coping Mechanisms

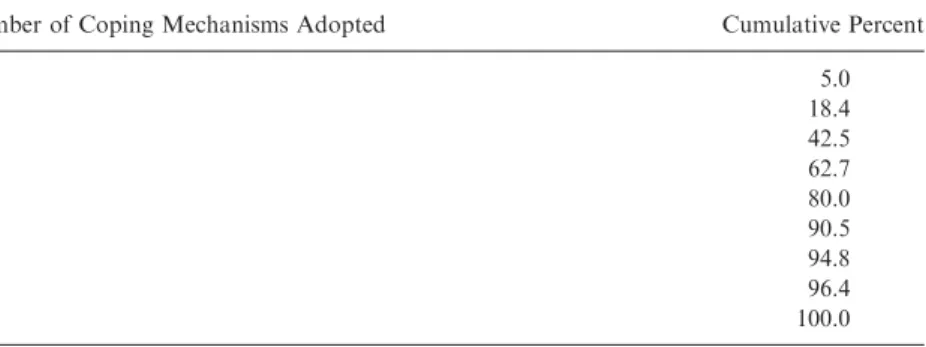

Table 4 shows the cumulative number of coping mechanisms employed by respondents. It can be found that only 5% of respondents did not use any of the coping strategies stated in this study. These data show a pervasive use of coping mechanisms across the sample. Many respondents even chose to adopt more than one coping mechanism when in circumstance with recreation conflict.

Table 2. Item Means and Reliability of the Recreation Specialization Scale.

Item Cronbach Mean Alpha

Skill and knowledgea 0.85

Subjective skill level 2.77

Subjective ability of operation 2.89 Subjective ability to deal with unexpected circumstance 2.91

Subjective knowledge level 2.94

Commitmentb 0.88

Other activities do not interest me as much as water-based activities 2.88 If I could not involve in water-based activities, I am not sure what I 2.44

would do

If I stopped water-based activities, I would probably lose touch 2.44 with a lot of my friends

I would rather involve in water-based activities than do most 2.89 anything else

Behavior 0.60

How often do you take a trip of water-based activities last year?c 2.18 How much did you spend on equipment investment?d 3.11 How much did you spend on water-based activity related 2.64

expenditures?d a

Measured on a scale, where 1 ¼ very bad and 5 ¼ very good. b

Measured with Likert-type format, where 1 ¼ strongly disagree and 5 ¼ strongly agree. c

Measured on a scale, where 1 ¼ never and 5 ¼ very often. d

Measured on a scale, where 1 ¼ none and 5 ¼ very much.

Responses to the adoption of each coping mechanism are shown in

Table 4. Statements 1 through 4 describe use of the coping strategies of displacement. As suggested in the literature review, displacement can include temporal, spatial, and activity ones. Thirty-seven percent of the participants responded in temporal displacement, while 25.2% in activity displacement. Spatial displacement behaviors included shifting use to other place within the same site (intra-site displacement, 54.2%) and shifting use to other place out of the original site (inter-site displacement, 30.2%). Responses to statements 5 and 6 describe use of the cognitive coping mechanisms of rationalization. More than 35.5% of respondents engage the mechanism of rationalization in that their use of the place has not changed much, but they are not as satisfied with their experiences. More than 43.2% of the respondents reported the use of product shift, which means they believe the type of experience provided by the place has changed although their use of this place has not changed a lot (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3. Cumulative Number of Coping Mechanisms Adopted. Number of Coping Mechanisms Adopted Cumulative Percent

0 5.0 1 18.4 2 42.5 3 62.7 4 80.0 5 90.5 6 94.8 7 96.4 8 100.0

Table 4. Adoption of Coping Mechanisms.

Statement Response (%)

Yes No

1. I go here for water-based activities at another time 37.0 63.0 2. I go other place within Kenting area for water-based activities 54.2 45.8 3. I go other place away from Kenting area for water-based activities 30.2 69.8 4. I do other leisure activities at the same place 25.2 74.8 5. I still stay at the same place, but I am not as satisfied with my 40.0 60.0

experience here

6. Since I had been here, I accept it 35.5 64.5 7. I still stay at the same place, but the type of experience provided by 43.2 56.8

this place has changed

8. I think use level of this place is not as low as before 49.1 50.9

Evaluation of Conflict and Adoption of Coping Mechanisms among Different Groups

Consistent with hypothesized, we found significant differences among motorized, nonmotorized, and dual participants for unacceptable behaviors of motorized participants (F ¼ 4.14, p ¼ 0.02). The post-hoc (least significance difference, LSD method) comparisons suggested that the main differences in perceived conflict occurred between nonmotorized and dual participants in which the conflict evaluation of nonmotorized participants toward motorized participants is significantly higher than dual participants’ evaluation. Moreover, although not significant in the post-hoc comparisons,

Table 5. Different Activity Group Influences on Conflict Evaluations. Conflict Evaluation for Motorized

Participants

Conflict Evaluation for Nonmotorized Participants A. Motorized participants B. Dual participants C. Nonmotorized participants 3.37 3.23 3.45 2.65 2.49 2.43 LSD test F-value p-value CWB 4.14* 0.02 1.56 0.21 *po0.05.

the conflict evaluation of nonmotorized participants toward motorized participants is also higher than motorized participants themselves. These findings indicate that nonmotorized participants reported more unaccep-table behaviors for motorized participants than fellow motorized partici-pants. This is congruence with previous studies that out-group conflict is found more obviously than in-group conflict. It is interesting that the conflict evaluation toward motorized participants by dual participants is lower than expected and even lower than fellow motorized participants.

On the other hand, although the mean score of conflict evaluation for nonmotorized participants ranged from high to low are motorized, dual, and nonmotorized participants as hypothesized, no significant differences were found among motorized, nonmotorized, and dual participants for unacceptable behaviors of nonmotorized participants (F ¼ 1.56, p ¼ 0.21). However, these data show that motorized participants will be more likely than nonmotorized and dual participants to experience conflict when evaluating nonmotorized water-based activities. In general, out-group conflict is found more obviously than in-group conflict (Table 5).

For the adoption of coping mechanisms, significant differences were found in different activity groups only in the adoption of displacement (F ¼ 3.87, p ¼ 0.02). The post-hoc (LSD method) comparisons suggested that the main differences in the adoption of displacement occurred between motorized and the other groups. That is, motorized participants tend not to adopt displacement to cope with conflict problems than the other two groups. It was recognized in the study that coping mechanisms adopted by dual participants was found between the other two extremes (seeTable 6).

Table 6. Different Activity Group Influences on Coping Mechanism. Overall Coping Product Shift Displacement Rationalization A. Motorized participants 2.87 1.03 1.10 0.74 B. Dual participants 3.14 0.94 1.47 0.73 C. Nonmotorized participants 3.25 0.85 1.61 0.79 LSD test B,CWA F-value 1.03 1.19 3.87* 0.35 p-value 0.36 0.31 0.02 0.71 *po0.05.

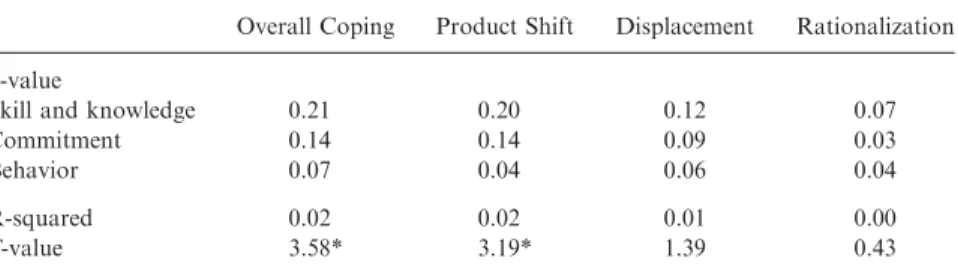

Table 7. Relationships between Specialization and Adoption of Coping Mechanisms.

Overall Coping Product Shift Displacement Rationalization b-value

Skill and knowledge 0.21 0.20 0.12 0.07

Commitment 0.14 0.14 0.09 0.03

Behavior 0.07 0.04 0.06 0.04

R-squared 0.02 0.02 0.01 0.00

F-value 3.58* 3.19* 1.39 0.43

*po0.05.

Relating Specialization to Adoption of Coping Mechanisms

Linear regressions were used to explore relationships between specialization and adoption of coping mechanisms (Table 7). The first regression analysis explored specialization and the overall coping mechanisms, while the second series of regression analyses were used to explore the construct and adoption of subsets of coping mechanisms: displacement, rationalization, and product shift. Responses to the eight items of coping mechanisms were added to a cumulative index so that the higher the index scores, the more coping mechanisms were adopted. Linear regression equation was statistically significant, however, only 2% of the variation in adoption of overall coping mechanisms was explained by two dimension of specialization: ‘‘skill and knowledge’’ (b ¼ 0.21) and ‘‘commitment’’ (b ¼ 0.14). Similar results were found for subset coping mechanisms of product shift (2%, b ¼ 0.20 and 0.14, respectively). The higher the level of respondents’ skill and knowledge as well as their commitment to water-based activities, the more likely they

were to adopt coping mechanisms. As we found in previous studies, more experienced recreationists were more sensitive to any changes on the setting or activity, thus, they are more likely to engage in more problem-focused coping strategies such as displacement and avoidance. On the other hand, the broader knowledge base of experienced or expert recreationists would also offer them more information about ways for coping.

DISCUSSION

This paper examined conflict reported by motorized, nonmotorized, and dual participants and further explored the influence of their specialization level on the adoption of coping mechanisms. As technological advances change the ways in which people enjoy the outdoors, they also introduce more potential problems for recreation conflict given that they may (Schneider, 2000;Vaske et al., 2004), especially when new activity groups share the same resources with traditional recreationists. Based on this research, motorized and nonmotorized water-based activities are practical examples for the conflict between new technological and traditional activity players.

First, unlike previous work, respondents in this study were segmented further according to their past experiences into motorized, nonmotorized, and dual participants. Study findings supported the predictive relationships. Among all three groups, less conflict was reported for nonmotorized participants than motored participants. When evaluating motorized activity behavior, nonmotorized participants were more likely than motorized and dual participants to experience conflict (Hypothesis H1). To the extent conflict

existing for nonmotorized water-based activities, motorized and dual participants were more likely than nonmotorized participants to report unacceptable behaviors (Hypothesis H2). In congruence with previous

research (Jackson & Wong, 1982; Gibbons & Ruddell, 1995; Vaske et al., 2000;Carothers et al., 2001), higher perceptions of conflict were reported by respondents engaging in different activities (out-group conflict), while dual participants fell in between the other two extremes. The asymmetrical conflict between motorized and nonmotorized activities suggested by past studies was also revealed in this paper. Nonmotorized participants were found to report higher perception of conflict to motorized participants than vise versa.

Second, the data suggest that coping mechanisms are widely employed in outdoor recreation. Various choices were adopted by recreationists. In this research, adoption of any of the eight mechanisms stated in this study ranged from 25.2 to 54.2%. In an overall perspective, 95% of respondents

employed more than one coping mechanism. Some of them even employed all three types, namely, displacement, rationalization, and product shift, to avoid or reconcile conflict problems. It is noteworthy that the adoption of coping mechanisms may help recreationists remain their satisfaction when encountering unacceptable conflict problems, but also that too much coping may result in diminished diversity of outdoor recreation opportunities as mentioned by Manning and Valliere (2001). For example, displaced users may shift their use to previously low-use times or places, so that the use level of these times or places may increase and they are no longer identified as ‘‘low-use.’’ Without proper conflict management strategies, conflict may occur in these new areas. Therefore, to reduce the level of recreation conflict should be a fundamental objective for park managers.

Third, due to the range of past experience and skill levels among all the respondents, the influences of recreation specialization on their adoption of coping mechanisms were examined. Results revealed that only the dimensions ‘‘skill and knowledge’’ and ‘‘commitment’’ of specialization were significant predictors for the adoption of coping mechanisms. These indicate that level of recreationists’ skill, knowledge, and commitment may slightly influence their willingness to adopt coping mechanisms. Individuals with better-specialized level may be more sensitive to conflict and thus be more likely to engage in more problem-focused coping strategies. Their broader knowledge base may also help them to seek for adequate coping strategies. Although significant relationships are found between specialization and coping behaviors, low percentage of variance explanation suggests that there shall be more factors influencing the adoption of coping mechanisms by recreationists and needed further exploration. For example, Anderson (1981) suggested that the relationship between past experience and displacement of recreationists may not be significant because of their attachment to a specific place.

Finally, as this study was conducted within a national park, problem of recreation conflict may be more troubling at a broader level. Although promotion of recreational activities in national parks seems to make many efforts on economic aspect, it deserves more concern in the compatibility between ecological and economical objectives of park management. Reviewing recreation literature, zoning, and education are two general strategies suggested to deal with conflict (Thapa & Graefe, 2004; Vaske et al., 2007). In this research, we found that conflict problems caused by motorized participants are generally reported as higher, especially for their negative impact on the environment. We think that not only education programs have to be continued, but also zoning combined with rotated (Pigram & Jenkins, 1999) or limited use of motorized activities can be

considered, especially in areas with precious and vulnerable resources to ensure the balance between recreational use and natural resources.

REFERENCES

Adelman, B., Heberlein, T., & Bonnicksen, T. (1982). Social psychological explanations for the persistence of a conflict between paddling canoeists and motorcraft users in the Boundary Waters Canoe Area. Leisure Sciences, 5, 45–61.

Anderson, D. H. (1980). Long-time boundary waters’ visitor change use patterns. Naturalist, 31, 2–5.

Anderson, D. H. (1981). The effect of user experience on displacement. Paper presented at the Applied Geography conference, Binghamton, NY.

Anderson, D., & Brown, P. (1984). The displacement process in recreation. Journal of Leisure Research, 16, 61–73.

Bricker, K. S., & Kerstetter, D. L. (2000). Level of specialization and place attachment: An exploratory study of whitewater recreationists. Leisure Sciences, 22, 233–257. Bryan, H. (1977). Leisure value systems and recreational specialization: The case of trout

fishermen. Journal of Leisure Research, 9, 174–187.

Carothers, P., Vaske, J. J., & Donnelly, M. P. (2001). Social values versus interpersonal conflict among hikers and mountain bikers. Leisure Sciences, 23(1), 47–61.

Ditton, R. B., Loomis, D. K., & Choi, S. (1992). Recreation specialization: Re-conceptualization from a social worlds perspective. Journal of Leisure Research, 24, 33–51.

Ditton, R. B., & Sutton, S. G. (2004). Substitutability in recreational fishing. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 9(2), 87–102.

Donnelly, M. P., Vaske, J. J., & Graefe, A. R. (1986). Degree and range of recreation specialization: Toward a typology of boating related activities. Journal of Leisure Research, 18, 81–95.

Gibbons, S., & Ruddell, E. (1995). The effect of goal orientation and place dependence on select goal interferences among winter backcountry users. Leisure Sciences, 17, 171–183.

Hall, T., & Shelby, B. (2000). Temporal and spatial displacement: Evidence from a high-use reservoir and alternate sites. Journal of Leisure Research, 32(4), 435–456.

Hammitt, W., & Patterson, M. (1991). Coping behavior to avoid visual encounters: Its relationship to wildland privacy. Journal of Leisure Research, 23, 225–237.

Hammitt, W. E., Backlund, E. A., & Bixler, R. D. (2004). Experience use history, place bonding and resource substitution of Trout Anglers during recreation engagements. Journal of Leisure Research, 36(3), 356–378.

Havitz, M. E., & Dimanche, F. (1997). Leisure involvement revisited: Conceptual conundrums and measurement advances. Journal of Leisure Research, 29, 245–278.

Havitz, M. E., & Dimanche, F. (1999). Leisure involvement revisited: Drive properties and paradoxed. Journal of Leisure Research, 31, 122–149.

Heberlein, T., & Shelby, B. (1977). Carrying capacity, values, and the satisfaction model: A reply to Greist. Journal of Leisure Research, 9, 142–148.

Jackson, E. L., & Wong, R. (1982). Perceived conflict between urban cross-country skiers and snow-mobilers in Alberta. Journal of Leisure Research, 14, 47–62.

Joan, K. (2002). Understanding wilderness land use conflicts in Alaska and Finland. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Idaho, College of Graduate Studies, Idaho. Kuentzal, W. F., & McDonald, C. D. (1992). Differential effects of past experience,

commitment, and lifestyle dimensions of river use specialization. Journal of Leisure Research, 29, 320–341.

Lee, C. M. (1997). Conflicts between recreationists at Elk/Beaver Lake, Saanich, British Columbia: A study in attitudes and awareness to lake use and management. Unpublished thesis, University of Victoria, Department of Geography, Canada.

Lee, J. H., & Scott, D. (2004). Measuring birding specialization: A confirmatory factor analysis. Leisure Sciences, 26(3), 245–260.

Manfredo, M., & Anderson, D. (1987). The influence of activity importance and similarity on perception of recreation substitutes. Leisure Sciences, 9, 77–86.

Manning, R. (1999). Studies in outdoor recreation: Search and research for satisfaction. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press.

Manning, R., & Ciali, C. (1980). Recreation density and user satisfaction: A further exploration of the satisfaction model. Journal of Leisure Research, 12, 329–345.

Manning, R., & Valliere, W. A. (2001). Coping in outdoor recreation: Causes and consequences of crowding and conflict among community residents. Journal of Leisure Research, 33(4), 410–426.

McIntyre, N., & Pigram, J. J. (1992). Recreation specialization reexamined: The case of vehicle-based campers. Leisure Sciences, 14, 3–15.

Miller, C. A., & Graefe, A. R. (2000). Degree and range of specialization across related hunting activities. Leisure Sciences, 22, 195–204.

Petrick, J. F., Backman, S. J., Bixler, R., & Norman, W. C. (2001). Journal of Leisure Research, 33(1), 56–70.

Pigram, J. J., & Jenkins, J. M. (1999). Outdoor recreation management. New York, NY: Routledge. Ramthun, R. (1995). Factors in user group conflict between hikers and mountain bikers.

Leisure Sciences, 17, 159–169.

Robertson, R., & Regula, J. (1994). Recreational displacement and overall satisfaction: A study of central Iowa’s licensed boaters. Journal of Leisure Research, 26(2), 174–181. Schneider, I., & Hammitt, W. (1995). Visitor response to outdoor recreation conflict: A

conceptual approach. Leisure Sciences, 17, 223–234.

Schneider, I. E. (2000). Revisiting and revising conflict research. Journal of Leisure Research, 32(1), 129–132.

Schreyer, R., & Lime, D. (1984). A novice isn’t a novice: The influence of experience use history on subjective perceptions of recreation participation. Leisure Sciences, 6, 131–149. Schreyer, R., Lime, D., & Williams, D. (1984). Characterizing the influence of past experience

on recreation behavior. Journal of Leisure Research, 16, 34–50.

Shelby, B. (1980). Contrasting recreational experiences: Motors and oars in the Grand Canyon. Journal of Soil and Water Conservation, 35, 129–131.

Snow, R. (1980). A structural analysis of recreation activity substitution. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX.

Sutherland. (1996). The international dictionary of psychology. New York: Crossroad. Thapa, B., & Graefe, A. R. (2004). Recreation conflict and tolerance among skiers and

snowboarders. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 22(1), 37–52.

Todd, Z. R. (1993). Trail bicycling: A study of recreation conflict in national parks. Unpublished thesis, University of Alberta, Department of Recreation and Leisure Studies, Canada.

Vaske, J. J., Carothers, P., Donnelly, M. P., & Baird, B. (2000). Recreation conflict among skiers and snowboarders. Leisure Sciences, 22, 297–313.

Vaske, J. J., Donnelly, M. P., & Heberlein, T. A. (1980). Perceptions of crowding and resource quality by early and more recent visitors. Leisure Sciences, 3(4), 367–381.

Vaske, J. J., Dyar, R., & Timmons, N. (2004). Skill level and recreation conflict among skiers and snowboarders. Leisure Sciences, 26(3), 215–225.

Vaske, J. J., Needman, M. D., & Cline, R. C., Jr. (2007). Clarifying interpersonal and social values conflict among recreationists. Journal of Leisure Research, 39(1), 182–198. Vitterso, J., Chipeniuk, R., Skar, M., & Vistad, O. I. (2004). Recreational conflict is affective:

The case of cross-country skiers and snowmobiles. Leisure Sciences, 26(3), 227–243. Wang, C. & Dawson, C. (2000). A comparison of recreation conflict factors for different

water-based recreation activities. In: G. Kyle (Ed.). Proceedings of the 2000 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium(pp. 121–130). Newtown Square, PA: USDA, Forest Service, Northeastern Research Station.

Watson, A. E. (1995). An analysis of recent progress in recreation conflict research and perceptions of future challenges and opportunities. Leisure Sciences, 17, 235–238. Watson, A. E., Niccolucci, M. J., & Williams, D. R. (1994). The nature of conflict between

hikers and recreational stock users in the John Muir wilderness. Journal of Leisure Research, 26(4), 372–385.

Watson, A. E., Williams, D. R., & Daigle, J. J. (1991). Sources of conflict between hikers and mountain bike riders in the Rattlesnake NRA. Journal of Park and Recreation Administration, 9, 59–71.

Watson, A., Zaglauer, H., & Stewart, S. (1996). Activity orientation as a discriminant variable in recreation conflict research. In: Proceedings of the 1995 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium(Gen. Tech. Rep. NE-218, pp. 103–108). Saratoga Springs, NY: USDA Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station.