http://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/

© Centre for Language Studies National University of Singapore

The L2 Acquisition of Information Sequencing in

Chinese: The Case of English CSL Learners in Taiwan

1Fred Jyun-Gwang Chen

(fredchen@ntnu.edu.tw)

National Taiwan Normal University, Taiwan R.O.C.

Abstract

Research has indicated that L1 transfer appears at early stages of L2 acquisition and decreases as L2 profi-ciency increases. Additionally, it has been shown that learners exhibit different linguistic behavior according to distinct task types. This study employs a cross-linguistic learner performance comparison, encompassing 30 English CSL learners as the experimental group, 30 Korean CSL learners as the control group, and 35 Chinese native speakers as the baseline group. The English and Korean CSL learners are further divided into three L2 proficiency levels. All participants completed sentence and discourse tasks. There are three major findings. First, L1 transfer is found to occur in the English learners’ Chinese interlanguage. Second, L1 trans-fer is mitigated by the English learners’ Chinese L2 proficiency. Third, the discourse function of correlative markers yinwei/suoyi (“because/so”) employed by Chinese native speakers to signal guidepost-echo relation-ship has not been acquired by the two CSL groups, irrespective of their Chinese L2 proficiency.

1 Introduction

Studies in cross-cultural differences and second language acquisition have shown that many in-tercultural miscommunications arise from different perceptions and interpretations of cultural con-ventions and discourse patterns. In his pioneering Contrastive Rhetoric study, Kaplan (1966) ana-lyzes 598 English expository essays written by native speakers of English, Semitic, Oriental, Ro-mance, and Russian languages and identifies five distinct rhetorical patterns of paragraph organi-zation: (1) linear – English; (2) parallel – Semitic languages; (3) indirect and circular – Oriental languages, referring to Chinese and Korean; (4) digressive – Romance languages, and (5) non-linear – Russian. These varied structures arise from systematic differences in the respective first language (L1) cultural mode of thinking, which is reflected in each culture's own rhetorical or-ganization (Kaplan, 1972).

Since Kaplan's seminal work, subsequent research on Contrastive Rhetoric has proliferated in the area of English and other languages with an aim to provide evidence of L1 transfer in language learners’ second language (L2) writing. Additionally, many L2 researchers interested in the con-trastive study of English and Chinese have investigated the role of L1 rhetorics to explain L2 learners’ linguistic behavior. It is suggested that differences in rhetorical preference in English and Chinese often have created a clash between what L2 learners have learned in their native language and what is expected of them from native speakers of the target language (Kaplan, 1966, 1972; Young, 1982; Norment, 1984; Cheng, 1985; Kirkpatrick, 1991, 1993a, 1993b; Scollon & Scollon, 1991, 1995, 2001; Lee, 2003). Thus, in theory, Chinese learners of English as a second language (ESL) and English learners of Chinese as a second language (CSL) alike should be apt to transfer their L1 rhetorical patterns when they write in the L2.

2 inguistic pattern under investigation

ome fundamental issues raised by information sequencing in Chinese and English are high-lig

2.1 Linguistic aspects of information sequencing

has been well documented (e.g. Wang, 1984; Li & Zhang, 1986; Kirkpatrick, 1993a; Scollon, 199

(1) yinwei L

S

hted with reference to linguistic, sociolinguistic, and psycholinguistic aspects.

It

3; cf. Biq, 1995) that, in general language use, the preferred or unmarked sequence in Chinese complex sentences is for the subordinate clause (SC) to precede the main clause (MC). Wang (1984, p. 96), for instance, observes that “in Chinese, the main component comes at the end, and the subordinate component comes at the beginning.” Li and Zhang (1986) also indicate that the natural clause sequence in Chinese complex sentences is subordinate-to-main clauses (SC–MC), although the salient and less common main-to-subordinate clause (MC–SC) sequence is possible (Osgood, 1980). Kirkpatrick provides an example which illustrates the most common SC–MC sequence in Chinese in (1) (Kirkpatrick, 1993a, p. 31).

feng tai da suoyi bisai gaiqi-le

me-A.

th st he n was postponed

xample (1) is a causality sentence in which the conjunction yinwei (“because”) appears in the sen

because Y

here Y is taken to be the cause of X or explanation of X. The marked structure is ecause Y, X

ther researchers also point out that in the sequence of English main and subordinate clauses, the

(2) Because

Because wind too big, so competition change ti ‘Because e wind was too rong, t competitio .’

E

tence-initial position. Additionally, Scollon (1993) indicates that there are two main structures in which because is used in English. The unmarked structure is as follows:

X w B O

unmarked sequence has the main clause first (Clark & Clark, 1977; Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech & Svartvik, 1985; Prideaux & Hogan, 1993). For example, in a study of 40 Chinese letters of re-quest, Kirkpatrick (1991) demonstrates that the unmarked SC–MC sequence in complex sentences is also a fundamental principle for sequencing the information in discourse. He provides the Eng-lish translation of a Chinese letter which reveals the Chinese writing preference for prefacing a request with reasons as noted in (2) (Kirkpatrick, 1991, p. 195).

I was listening to a program last night and heard the news that a lady colleague who had returned from Singapore was offering New Year's gifts, this excited my interest. I hope that she can send me some gifts and a photograph of herself, but because I have rudely [sic] forgotten her name, I hope you can take the trouble ...2

irkpatrick notes that the request – for some gifts and a photograph – in the body of the letter is p

hi-nes

K

receded by the two reasons for the request, both following the because-initial sequencing. Additionally, Wang (1997, p. 471; 2002, p. 150), in her analysis of adverbial clauses in C e discourse, found that, among her written corpus which is drawn from two sources, 56.3% of the casual clauses appear before their associated modified material (SC-MC), whereas 43.7% appear after those they modify (MC–SC). The contrastive descriptive statistics (56.3% vs. 43.7%) in Wang’s written data also reveal the tendency for Chinese native speakers to sequence their in-formation in a because-initial position (i.e. SC–MC sequence).3

The disparate information sequencing in Chinese and English is also consistent with the notion of Principal Branching Direction (PBD)4 in language typology. Chinese and English are catego-rized as typologically distinctive languages with respect to the PBD: Chinese is a left-branching language, while English is largely a right-branching language. This typological distinction ac-counts for the underlying Chinese preference for an SC–MC sequence and the English preference for an MC–SC sequence.

2.2 Sociolinguistic aspects of information sequencing

Young (1982), in her analysis of Chinese native speakers’ spoken English, argues that different ways of structuring information receive different social evaluations or rankings. She demonstrates that Chinese speakers prefer to delay their topic or thesis statement until supporting statements have been given as in the following example (Young, 1982, p. 77).

(3) Theta: One thing that I would like to ask. BECAUSE MOST OF OUR RAW MATERIALS ARE COMING FROM JAPAN AND THIS YEAR IS GOING UP AND UP AND IT’S NOT REALLY I THINK AN INCREASE IN PRICE BUT WE LOSE A LOT IN EXCHANGE RATE AND SECONDLY I UNDERSTAND WE’VE SPENT A LOT OF MONEY IN TV AD LAST YEAR. So, in that case I would like to suggest here: chop half of the budget in TV ads and spend a little money on Mad magazine.

As indicated by Young, the subordinate marker because initiates the listing of reasons in the supporting statements (capitalized), which establish the situational framework for evaluating the significant information to follow in the main clause (italicized). Young argues that Chinese speak-ers tend to minimize confrontation in formal social relationships, and this can be traced to culture-specific notions of acceptable discourse strategies. Chinese speakers find it uncomfortable to in-troduce their request at the outset, and thus by sequencing information differently from English native speakers, Chinese speakers are actually displaying a culturally appropriate discourse strat-egy: i.e. they are minimizing the imposition by exerting ‘negative politeness’ (Brown & Levinson, 1987). Young concludes that there are correspondences between linguistic behavior and social evaluation and that difficulties in cross-cultural interactions will tend to occur when speakers are faced with an unfamiliar sociolinguistic tradition.

In the same vein, Scollon and Scollon (1991) claim that confusion in intercultural communica-tion often arises as a result of differing discursive strategies in the placement of the topic state-ment. The Chinese discourse convention is an inductive one: i.e. the topic, such as a request, is generally deferred until after a considerable amount of discourse (e.g. “small talk”) which encodes reasons is provided. This reason-request sequence is the inverse of the deductive Western dis-course pattern, in which the topic statement is given first and then followed by the supporting ar-guments, as exemplified by Schiffrin (1987, p. 207) in (4).

(4) Can you work any of this with just the two of us, or you'll have to wait for Irene? Cause I don't know how long she'll be.

In (4), the speaker made a request (accomplished by an indirect question) – can we do without Irene? – and then gave a reason for it. However, to place a request at the beginning is deemed pre-sumptuous in Chinese conversation, where the small talk is valued as a kind of extended ‘face-work’ (Goffman, 1967) that can mitigate the imposition later to appear in the topic statement. Ac-cording to Scollon and Scollon, the Chinese inductive pattern of topic introduction is a natural outcome of interpersonal relationships, and the linguistic structure of SC–MC information se-quencing which facilitates this interpersonal position is thus preferred.

2.3 Psycholinguistic aspects of information sequencing

The psycholinguistic aspects of information sequencing are pertinent to the concept of iconic-ity. For example, Ungerer and Schmid (1996, p. 251) propose the Principle of Iconic Sequencing, namely: “The sequence of two clauses corresponds to the natural temporal order of events.” They provide the example in (5).

(5) He opened the bottle and poured himself a glass of wine. *He poured himself a glass of wine and opened the bottle.

Here the first sentence clearly corresponds to the natural temporal order of events; the second sentence is unacceptable because the order in which the clauses are arranged violates the principle of iconic sequencing, although not ungrammatical according to the rules of syntax.

Sequential iconicity is best illustrated by Clark (1971) in the context of language development in children. Clark proposes that children utilize the Order of Mention Strategy in processing sen-tences. That is, children tend to interpret the order of mention of events as the linear (temporal) order of the events used as the reference point. Several research findings have corroborated that both Chinese and American children encounter comprehension difficulty when the order of men-tion of events conflicts with the temporal order of events specified by the sentence (e.g. Kuo, 1985; Kwoh, 1997). Thus, it appears that children’s comprehension difficulty is largely one of organizing or representing information in the mind, rather than a purely ‘linguistic comprehension’ problem (Chang, 1991).

The notion of sequential iconicity in Chinese is substantively explicated by Tai (1985, 1993), who has posited the Principle of Temporal Sequence (PTS): “the relative word order between two syntactic units is determined by the temporal order of the states which they represent in the con-ceptual world” (1985, p. 50). According to the PTS, when two Chinese sentences are linked by temporal connectives, the first event always precedes the second one and the reverse is not possi-ble as illustrated in (6).

(6) ni gei wo qian cai neng zou

You gave me money then can leave

‘You can’t leave until you give me the money.’

The Chinese sentence in (6) would be ill-formed if the second event (“then can leave”) were ordered before the first event (“You give me the money”). Thus, the iconic nature of information sequencing in Chinese suggests a close parallelbetween surface linguistic behavior and underlying cognitive activities.

The SC–MC information sequencing in Chinese is also consistent with the PTS, since the cause (reason) always precedes the effect (consequence) in real time. However, the English translation in (6) shows that conjoined sentences in English need not incorporate the cognitive structure of the PTS, because the normal clause order in English is not constrained by the sequence of events. Hence, in terms of word order, Chinese is more iconic than English. Although psycholinguistic studies have revealed that human cognition and perception do not seem to vary considerably (e.g. Kwoh, 1997), the linguistic patterns used to encode the conceptual principles in each culture may differ to a great extent, as exemplified by the disparate preferences for sequencing information in Chinese and English.

3 Purpose of the study

Previous research on information sequencing has been primarily concerned with either English or Chinese L1 writing, respectively, or with the typological transfer of Chinese L1 information sequencing to English L2 writing. The present author attempts to investigate further if typological transfer of information sequencing in English and Chinese is bidirectional: that is, not only

Chi-nese-to-English but also English-to-Chinese typological transfer is possible. Additionally, previous research has indicated that L1 transfer is mitigated by L2 proficiency (Chan, 2004; Chen, 2006) and that language users or learners may behave in a linguistically different way according to dif-ferent task types (Chen, 2006). Thus, this paper seeks to address the following three research ques-tions.

1. Will the English CSL learners typologically transfer English L1 information sequencing to their Chinese L2 writing?

2. To what extend does this typological transfer, if it is found to occur, relate to the English learners’ Chinese L2 proficiency?

3. To what extent will task effect, if it is found to occur, constrain the linguistic behavior of the different language groups in this study?

4 Method

4.1 Research design

A cross-linguistic learner performance comparison is employed in this research to investigate if L1 transfer has occurred in the English learners’ Chinese L2 writing and the extent to which this transfer, if found to occur, relates to their Chinese L2 proficiency. This study has an overall quasi-experimental design with a between-groups design and a fixed-effects design nested within. Spe-cifically, the CSL learners who are native speakers of English are assigned to the experimental group, whereas the CSL learners who are native speakers of Korean are assigned to the control group. This crosslinguistic comparison design with non-randomly assigned language groups is necessary to provide cogent evidence for English L1 transfer, if there is any. This is based on the typological distinction that native speakers English (a right-branching language) generally prefer

because-medial (i.e. MC–SC) information sequencing, but native speakers of Korean (a

left-branching language) do not. 4.2 Participants

A total of 95 participants are recruited for this research. They are at least college-level students, many of whom are pursuing or holding an M.A. or doctoral degree. The participants are composed of three main groups: 35 Chinese native speakers as the baseline group, 30 English CSL learners as the experimental group, and 30 Korean CSL learners as the control group. In each CSL group, the participants are further divided into three subgroups across varying Chinese L2 proficiencies: intermediate, high-intermediate and advanced. The 95 participants are recruited from the various departments of National Taiwan Normal University (NTNU) and university-affiliated Chinese language centers in Taiwan, such as Mandarin Teaching Center (MTC) at NTNU and International Chinese Language Program (ICLP) at National Taiwan University (NTU).

4.3 Chinese L2 proficiency

The Chinese L1 baseline data come from 35 Chinese native speakers who are M.A. students at the Graduate Institute of Teaching Chinese as a Second Language at NTNU and who are also pre-vious undergraduates majoring in Chinese at universities in Taiwan. The intermediate CSL learn-ers are students at MTC or ICLP who have studied Chinese for one to two years. The high-intermediate CSL learners are those who have studied Chinese at either of these two language cen-ters for two to four years. The advanced CSL participants are from the various departments of NTNU or ICLP at NTU, who have studied Chinese for a minimum of four years and/or fulfilled the advanced criteria of ICLP. Among the 10 advanced English CSL learners, nine of them are advanced students at ICLP who are also professors or current doctoral students at US universities.

Among the 10 advanced Korean CSL students, seven are M.A. students and three are undergradu-ates at NTNU.

4.4 Instruments

The first instrument is a sentence-combining task (SCT) designed to elicit the non-target-like Chinese L2 pattern of information sequencing in a complex sentence. The second instrument is a discourse task (DT) designed to elicit the same pattern of information sequencing in discourse. 4.4.1 The sentence-combining task (SCT)

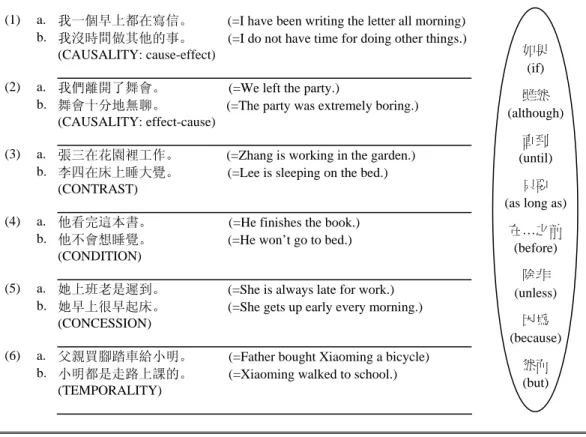

In the SCT, there are a total of 20 test items, encompassing five relationships: i.e. causality, contrast, condition, concession, and temporality. Out of the 20 test items, 12 target items focus on the target semantic relationship of causality – as conveyed by the conjunction yinwei (“because”) – to elicit because-medial information sequencing at the Chinese sentence level. The remaining 8 test items which contain the other four semantic relationships serve as distracters to avoid overtly drawing the participants’ attention to the target items. Additionally, the combining order in the SCT is flexible to allow the present researcher to see if because-medial information sequencing occurs in a Chinese complex sentence. Moreover, the sentence pairs to be combined are all inde-pendent sentences, and the sentence order of potential yinwei (“because”) clause is counter-balanced (i.e. cause-effect vs. effect-cause) lest the participants would combine each pair of sen-tences in the order in which they occur. Example of the SCT are provided in Figure 1.5

如果 (if) 雖然 (although) 直到 (until) 只要 (as long as)

在…之前 (before) 除非 (unless) 因為 (because) 然而 (but) (1) a. 我一個早上都在寫信。 (=I have been writing the letter all morning)

b. 我沒時間做其他的事。 (=I do not have time for doing other things.) (CAUSALITY: cause-effect)

(2) a. 我們離開了舞會。 (=We left the party.)

b. 舞會十分地無聊。 (=The party was extremely boring.) (CAUSALITY: effect-cause)

(3) a. 張三在花園裡工作。 (=Zhang is working in the garden.) b. 李四在床上睡大覺。 (=Lee is sleeping on the bed.)

(CONTRAST)

(4) a. 他看完這本書。 (=He finishes the book.)

b. 他不會想睡覺。 (=He won’t go to bed.)

(CONDITION)

(5) a. 她上班老是遲到。 (=She is always late for work.) b. 她早上很早起床。 (=She gets up early every morning.)

(CONCESSION)

(6) a. 父親買腳踏車給小明。 (=Father bought Xiaoming a bicycle) b. 小明都是走路上課的。 (=Xiaoming walked to school.)

(TEMPORALITY)

4.4.2 The discourse task (DT)

In the DT, the participants are asked to write a narrative of about 150 words from six sequential pictures. For each picture, the participants are asked to explain why an activity is taking place. It is hoped that by providing a reason for the activity in each picture, they will have at least six oppor-tunities to produce non-target-like L2 pattern of because-medial information sequencing at the Chinese discourse level. The example of the DT is given in Figure 2.

Fig. 2: The discourse task

In sum, the Chinese SCT is highly structured and the participants only need to combine the ex-isting sentences by choosing conjunctions from a list of options. In contrast, the Chinese DT re-quires that the participants generate their ideas in extended discourse. Thus, with different instru-ments, this research also seeks to see if the participants’ linguistic behavior differs according to the nature of instruments.

5 Results

5.1 The three language groups’ overall performance

Before addressing the research questions, it is informative to get a general picture of how the Chinese, English, and Korean participants in the present research use the target-like Chinese

be-cause-initial information sequencing (alternatively termed bebe-cause-initial structure) in their

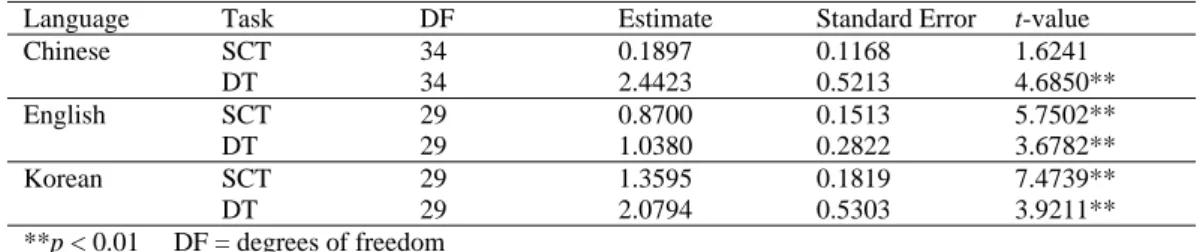

writ-ing at both the Chinese sentence and discourse levels. The overall performance of because-initial structure produced by these three language groups is first provided in relative frequencies and fol-lowed by significance tests as indicated in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Task The SCT The DT Language Groups because- initial because- medial because- initial because- medial Chinese 162 54.7% 134 45.3% 46 92% 4 8% English 148 70.5% 62 19.5% 48 75% 17 25% Korean 151 74.4% 52 25.6% 32 86.5% 5 13.5%

Table 1: Relative frequencies of because-initial vs. because-medial information sequencing from the three language groups in the SCT and DT

As indicated by the descriptive statistics (boldface) in Table 1, all three language groups appear to use more of because-initial structure than of because-medial structure in both the SCT and the DT. However, statistically speaking, the number of because-initial structure produced by the Eng-lish and Korean CSL learners must significantly exceed that of because-medial structure in order to argue for their mastery of the target-like because-initial structure in their Chinese L2 writing. Thus, significant tests are conducted to assess the evidence provided by the sample data as given in Table 2.

Language Task DF Estimate Standard Error t-value

Chinese SCT DT 34 34 0.1897 2.4423 0.1168 0.5213 1.6241 4.6850** English SCT DT 29 29 0.8700 1.0380 0.1513 0.2822 5.7502** 3.6782** Korean SCT DT 29 29 1.3595 2.0794 0.1819 0.5303 7.4739** 3.9211** **p < 0.01 DF = degrees of freedom

Table 2: Significance results of because-initial information sequencing from the three language groups in the SCT and DT

As revealed by the t-test, there is a statistically significant difference within each of the three language groups (p < 0.01) to produce the pattern of because-initial structure at both the sentence and discourse levels, except the Chinese group at the sentence level, who, nevertheless, shows a very strong statistical trend (p = 0.05) toward the use of because-initial structure, virtually achiev-ing the 0.05 level of statistical significance. Thus, it follows that both English and Korean groups are rather proficient in using the target-like because-initial structure to sequence information in their Chinese L2 writing.

However, do the statistical results suggest that the English CSL group has completely over-come the possible L1 transfer effect in their L2 writing, given that the literature has shown that English speakers prefer to use because-medial information sequencing in their L1? Not necessar-ily. Simply because the English CSL learners produce significantly more of because-initial struc-ture than of because-medial strucstruc-ture in their Chinese L2 writing, it does not mean that L1 transfer effect has been completely eliminated from their Chinese interlanguage. It is necessary to further conduct a cross-linguistic learner performance comparison in order to determine whether or not L1 transfer effect has occurred in their Chinese L2 writing. In what follows, the statistical results of the three research hypotheses are presented with respect to the CSL learners’ use of

because-medial structure in both the sentence and discourse tasks.

5.2 The first research hypothesis

The first research question concerns the extent to which because-medial structure in the L2 writing of English learners is a function of L1 transfer. In order to address this question, it is hy-pothesized that

(1) English CSL learners, when writing in Chinese L2, will supply significantly more of be-cause-medial structure at both sentence and discourse levels, which resembles that of their L1, than will Korean CSL learners, who typologically do not use this pattern as much in the L1.

The overall performance of because-initial structure and because-medial structure produced by the English and Korean CSL groups in the SCT and DT is first provided in relative frequencies and then followed by significance tests as indicated in Table 3 and Table 4.

CSL Groups SCT DT

Information

Sequencing because-medial because-initial because-medial because-initial

English 62 29.5% 148 70.5% 14 16.2% 48 73.9%

Korean 38 20.4% 151 79.6% 4 11.1% 32 88.9%

Table 3: Relative frequencies of because-initial vs. because-medial information sequencing from the English and Korean CSL groups in the SCT and the DT

DF Estimate Standard Error t-value

Task Type

SCT 1 0.2447 0.1183 2.0685*

DT 1 0.5206 0.3003 1.7336*

*p < 0.05 DF = degrees of freedom

Table 4: Significance results of because-medial information sequencing from the English and Korean CSL groups in the SCT and the DT

As indicated by the results of inferential statistics, the English CSL group appears to exhibit significantly more of because-medial structures than the Korean CSL group to sequence their in-formation in their Chinese L2 writing at both sentence and discourse levels (p < 0.05). Hypothesis (1) is therefore supported. Thus, despite the fact that both the English and Korean CSL groups appear to have produced significantly more of because-initial information in their Chinese L2 writing, the statistical results have revealed that the phenomenon of L1 transfer – i.e. the expected L1 tendency of native English speakers to use because-medial information sequencing – has been “secretively” couched in the English learners’ Chinese interlanguage and would have gone unno-ticed, if a cross-linguistic learner performance comparison had not been conducted.

5.3 The second research hypothesis

The second research question addresses to what extent the L2 use of because-medial informa-tion sequencing, as a result of English L1 transfer, relates to Chinese L2 proficiency. It is hypothe-sized that

(2) There is a negative relationship between Chinese L2 proficiency and the use of because-medial information sequencing in the English learners’ Chinese L2 writing at both the sentence and discourse levels.

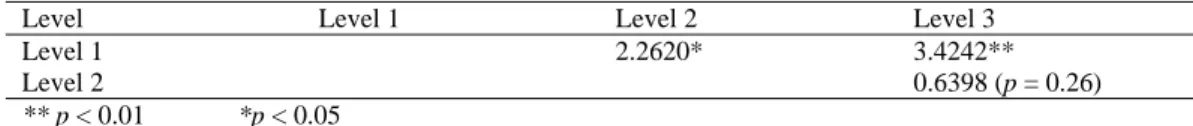

5.3.1 The sentence-combining task (SCT)

Inferential statistics reveals a statistically significant difference across the three Chinese L2 proficiencies in the English CSL learners’ use of because-medial information sequencing in the SCT (p < 0.01). Detailed statistical results using the Chi-square test are displayed in Table 5.

Level Effect DF Wald Chi-Square

SCT 2 13.7599**

**p < 0.01 DF=degrees of freedom

Table 5: Relationship between Chinese L2 proficiency and the English CSL learners’ use of

because-medial information sequencing in the SCT

As indicated by the statistical result, the English CSL learners’ use of because-medial informa-tion sequencing in the SCT appears to be related to Chinese L2 proficiency in the SCT. Further statistical tests are conducted to locate the exact differences among the three L2 Chinese profi-ciency levels in the SCT. The occurrence of because-medial structure among the three levels of the English CSL learners is first provided in relative frequencies and then followed by significance tests as indicated in Table 6 and Table 7.

CSL Groups SCT

English Learners because-medial because-initial

Level 1 31 47% 35 53%

Level 2 16 24% 51 76%

Level 3 15 19.5% 62 80.5%

Total 62 29.5 148 70.5%

Table 6: Relative frequencies of because-medial information sequencing across the three proficiencies of the English CSL learners in the SCT

Level Level 1 Level 2 Level 3

Level 1 2.2620* 3.4242**

Level 2 0.6398 (p = 0.26)

** p < 0.01 *p < 0.05

Table 7: Pairwise comparisons of the three Chinese proficiency levels on the use of because-medial information sequencing in the SCT

As indicated by the results of inferential statistics using the t-test, a significant difference is found between the Level 1 and Level 3 (p < 0.01) and between the Level 1 and Level 2 English CSL learners (p < 0.05). Moreover, there is a statistical trend in the difference between the Level 2 and Level 3 English CSL learners (p < 0.26).

Thus, the relationship between Chinese L2 proficiency and English L1 transfer is generally in a negative direction. That is, it is found that the more advanced the English learners are in their Chi-nese L2 proficiency, the less of because-medial structure they tend to produce in their L2 ChiChi-nese writing, and vice versa. Hypothesis (2) is therefore supported at sentence level.

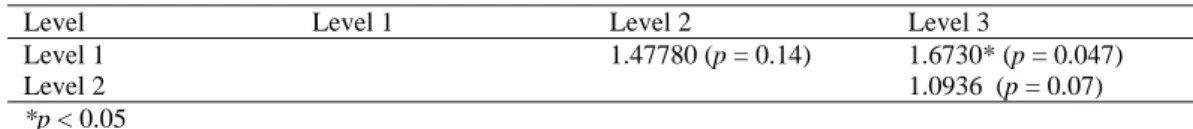

5.3.2 The discourse task (DT)

As noted in Table 8 below, the results of the Chi-square test indicate that there is a statistical trend (p = 0.2411) with respect to the English CSL learners’ use of because-initial information sequencing in the DT.

Level Effect DF Wald Chi-Square

DT 2 2.8451 (p = 0.2411)

DF = degrees of freedom

Table 8: Relationship between Chinese L2 proficiency and the English CSL learners’ use of because-medial information sequencing in the DT

To locate the exact differences among the three L2 Chinese proficiency levels in the DT, fur-ther statistical tests are conducted. The occurrence of because-medial structure among the three levels of the English CSL learners is first provided in relative frequencies and followed by signifi-cance tests as indicated in Table 9 and Table 10.

ESL Groups The Discourse Task (DT)

because-medial because-initial English Learners Level 1 9 36% 16 64% Level 2 6 26.1% 17 73.9% Level 3 2 10.5% 18 90.5% Total 17 25% 51 75%

Table 9: Relative frequencies of because-medial information sequencing across the three proficiencies of the English CSL learners in the DT

Level Level 1 Level 2 Level 3

1.47780 (p = 0.14) 1.6730* (p = 0.047) Level 1

1.0936 (p = 0.07) Level 2

*p < 0.05

Table 10: Pairwise comparisons of the three Chinese proficiency levels on the Use of because-medial information sequencing in the DT

As indicated by the results of the t-test in Table 10, a statistically significant difference is found between the Level 1 and Level 3 English CSL learners (p < 0.05), and there is a very strong statis-tical trend between the Level 2 and Level 3 English CSL learners (p = 0.07), approaching the 0.05 level of statistical significance. Moreover, there is a statistical trend in the difference between the Level 1 and Level 2 English CSL learners (p = 0.14). Thus, although the test result of hypothesis (2) does not exhibit a statistical significance at the 0.05 level in discourse6, it does show a statisti-cal tendency regarding the negative relationship between L2 Chinese proficiency and English L1 transfer.

5.4 The third research hypothesis

As aforementioned, previous research has shown that the participants’ linguistic behavior dif-fers according to the nature of instruments (Chen, 2006). Thus, it is hypothesized that

(3) The CSL learners or Chinese native speakers, when writing in Chinese, will exhibit dif-ferent use of because-initial information sequencing between sentence and discourse lev-els.

The occurrence of because-initial structure produced by the three language groups is first pro-vided in relative frequencies (Table 1 reiterated) and followed by significance tests as indicated in Table 11 and Table 12, respectively.

Task Type SCT DT Language Groups Relative Frequency because- initial because- medial Relative Frequency because- initial because- medial Chinese 55% 162 134 92% 46 4 English 70.5% 148 62 75% 48 17 Korean 74% 151 52 86.5% 32 5

Table 11: Relative frequencies of because-initial vs. because-medial information sequencing among the three language groups in the SCT and the DT

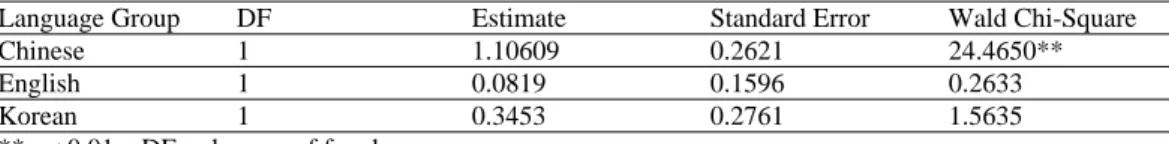

Language Group DF Estimate Standard Error Wald Chi-Square

Chinese 1 1.10609 0.2621 24.4650**

English 1 0.0819 0.1596 0.2633

Korean 1 0.3453 0.2761 1.5635

**p < 0.01 DF = degrees of freedom

Table 12: Use of because-medial information sequencing by the three language groups in the SCT and DT

As shown in Table 11 (boldface), Chinese native speakers predominantly use because-initial structure in the discourse task (92% of the time), but they appear to use the same L1 pattern much less in the sentence task (only 55% of the time). It is therefore not surprising that previous statisti-cal results in Table 2 only show that the Chinese native speakers only have a strong statististatisti-cal trend (p = 0.05), rather than a significant difference at the 0.05 level, toward the use of

because-initial structure at the sentence level, as compared to their high frequency of use in the same

Chi-nese L1 pattern at the discourse level (p <0.01).

As further indicated by the results of the Chi-square test in Table 12, the Chinese native speak-ers are also found to use significantly more of because-initial structure in the discourse task than they do in the SCT (p < 0.01). However, no such statistical significance is found on the perform-ance of either the English (p = 0.61) or Korean (p = 0.21) CSL learners between the two task lev-els. Thus, it appears that the Chinese native speakers’ linguistic behaviors do vary according to the two distinct task types. In contrast, English and Korean CSL learners behave consistently in both task types.

6 Discussion

6.1 The first research question and hypothesis

To address the first research question on L1 transfer, hypothesis (1) predicts that English CSL learners, when writing in Chinese L2, will exhibit more of because-medial structure (MC–SC), as influenced by their L1 (right-branching), than will Korean CSL learners who do not prefer this pattern in the L1 (left-branching, SC–MC) . The results, as shown in Table 4, indicate a statisti-cally significant difference between the two CSL groups in both the SCT and DT (p < 0.05). That is, the English learners are found to produce significantly more of because-medial structure than the Korean learners at both the sentence and discourse levels. Thus, the finding of the present re-search provides evidence to support that English because-medial information sequencing is trans-ferable to Chinese L2 writing. In conjunction with Chen’s (2006) finding that Chinese

because-initial information sequencing is transferable to English L2 writing, the data in this research study

support the bidirectionality of L1 transfer.

6.2 The second research question and hypothesis

To address the second research question on L2 proficiency, hypothesis (2) predicts that there is a negative relationship between the English CSL learners’ L1 transfer and their Chinese L2 profi-ciency. As Table 7 indicates, a statistically significant difference is found between Level 1 and Level 3 English learners in the SCT (p < 0.01), and a statistical trend between the Level 2 and Level 3 English learners in the SCT (p = 0.26). In addition, as revealed in Table 10, there is a sta-tistically significant difference between Level 1 and Level 3 English learners in the DT (p < 0.05), and there is a strong statistical trend between the Level 2 and Level 3 English learners in the DT (p = 0.07). Thus, the results of the findings in this study generally support the research claim that L1 transfer appears primarily at the early stages of interlanguage development and decreases

chrono-logically as L2 proficiency increases (e.g. Taylor, 1975; Kellerman, 1979; Major, 1986; Maeshiba et al., 1996; Chan, 2004).

The statistical results of this study together with previous research (Chen 2002) have contrib-uted to the findings that typological transfer of information sequencing is bidirectional and is miti-gated by L2 proficiency. That is, the more proficient the learners are in an L2 (either English or Chinese), the less they will tend to transfer their L1 typological features to their L2 interlanguage. 6.3 The third research question and hypothesis

This section will discuss at greater length the issue of task effect (i.e. the notion that learners behave in a linguistically different way between distinct task types) on the three language groups. 6.3.1 The disparate linguistic behavior of Chinese native speakers at the two different task

types

As indicated in Table 11, the Chinese native speakers use because-initial structure in the DT 92% of the time, but this reverts to 55% of the time in the SCT. How can one account for the dis-parate use of because-initial structure by the Chinese native speakers in the sentence and discourse tasks?

Such a discrepancy, however, can be readily interpreted from the perspectives of discourse functions and cognitive constraints, as suggested by a number of researchers. For example, as Young (1982) and Kirkpatrick (1993b) have suggested, Chinese tends to use subordinating clauses (SC) to set the frame for the main clause (MC) to come, and what are embedded within the Chi-nese SC—MC sequence are yinwei (“because”) and suoyi (“so”), which are often used together as a pair of correlative connectors to mark their mutual relationship in discourse. In addition, Chafe (1984) indicates that a subordinating clause with because occurring in the discourse-initial position is often used as a guidepost for the following discourse. In a similar vain, Sperber and Wilson (1995) propose a relevance theory of human communication in which they posit: (a) the more in-formation a person can gather from an utterance, the more relevant it will be; (b) the higher the processing efforts required, the smaller the relevance. Moreover, Prideaux (1989) and Prideaux and Hogan (1993) suggest that subordinating clauses with because occurring in the

discourse-initial position has a larger scope than those with “because” occurring intersententially (=

inter-clausally).

Accordingly, the Chinese discourse-initial maker yinwei (“because”) can be used as a discourse device to display relevance and provide connection for the following discourse, thus contributing to a minimal effort in terms of cognitive processing cost. It follows that the reason why the Chi-nese native speakers use significantly more of because-initial structure in the DT may have re-sulted from their considerations to employ the discourse-initial marker yinwei (“because”) as a

guidepost or relevance device to be echoed by the discourse marker suoyi (“so”) in the following

discourse. On the other hand, in the SCT in which the discourse scope is only a complex sentence, it would be less required, both cognitively and discoursally, for the Chinese speakers to use the sentence-initial marker yinwei (“because”) as a guidepost to draw the reader/hearer’s attention to the main point which follows. Hence, the Chinese native speakers may choose to drop yinwei (“because”) in the sentence-initial position and only use suoyi (“so”) interclausally in a discourse scope which involves only a complex sentence. The present researcher’s argument can be further supported by the following excerpt taken from the discourse task completed by a Chinese native speaker in the study.

Ø Dajia jucan zhihou zheng yao huijia, suoyi ta qu kaiche. Ø Jiche qishi he pengyou liaotian, suoyi mei kandao dangshi de lukuang. Zai daoche deshihou, youyu zhuanjiao shi ge sijiao, ta mei kandao houmian you yi tai jiche, er jiche ye mei kandao daoche de jiaoche, liangtai che jiu yinci zhuangshang le.7

“Everyone was going home after the dinner party, so he went to get the car. A motorcycle rider was chatting with his friends, so he didn’t pay attention to the road situation at the time. When the driver was backing up his car, he didn’t see a motorcycle behind him because there was a blind spot on the corner, and the motorcycle rider also did not see the car backing up (in front of him), so the two vehi-cles collided.”

In the first two sentences of the Chinese excerpt, the Chinese speaker does not use the dis-course-initial marker yinwei (“because”) (marked as Ø) but only provides interclausal conjunction

suoyi (“so”), presumably because the scope of the first two sentences is small and the discourse

function of yinwei (“because”) as discourse marker of guidepost or relevance marker would not be motivated. However, in the third and fourth sentences which form a unit with a larger discourse scope, the Chinese native speaker naturally employs the discourse marker youyu (synonymous to

yinwei “because”) to initiate the listing of reasons and establish the situational framework for the

coming event – i.e. the two vehicles collide, and is followed by another echoing discourse marker

yinci (synonymous to suoyi “so”) to signal the mutual relationship of cause-effect.

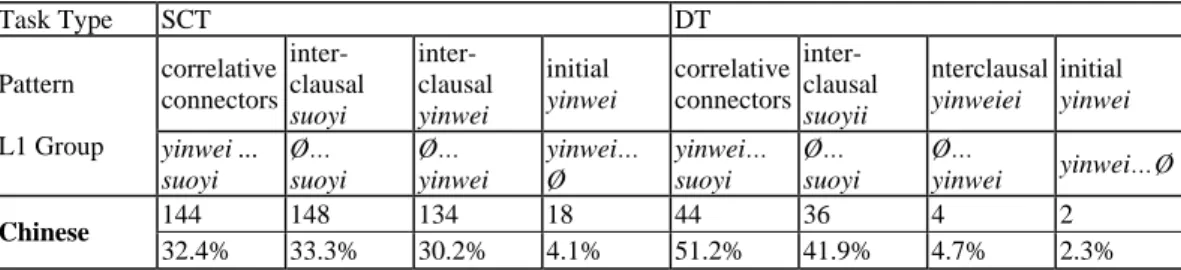

6.3.2 Different patterns of information sequencing by Chinese native speakers

As indicated in the preceding section, in a complex sentence in which the discourse scope is small, the Chinese native speakers often opt for the interclausal connector suoyi or yinci (“so”), rather than a pair of correlative markers, such as “yinwei…suoyi” or “youyu…yinci” (“be-cause…so”), which they reserve for a more extended discourse environment. To further illustrate this point, this section continues to examine different patterns of information sequencing used by the Chinese native speakers at the sentence and discourse levels. The relative frequencies of differ-ent patterns of information sequencing are displayed in Table 13.

Task Type SCT DT correlative connectors inter-clausal suoyi inter-clausal yinwei initial yinwei correlative connectors inter-clausal suoyii nterclausal yinweiei initial yinwei Pattern L1 Group yinwei ... suoyi Ø… suoyi Ø… yinwei yinwei… Ø yinwei… suoyi Ø… suoyi Ø… yinwei yinwei…Ø 144 148 134 18 44 36 4 2 Chinese 32.4% 33.3% 30.2% 4.1% 51.2% 41.9% 4.7% 2.3%

Table 13: Different patterns of information sequencing used by Chinese speakers in the SCT and the DT

As shown in Table 13, the Chinese native speakers, at the sentence-level information sequenc-ing, appear to use correlative connectors yinwei/suoyi (32.4%), the interclausal conjunction suoyi (“so”) (33.3%), and the interclausal conjunction yinwei (“because”) (30.2%) approximately the same, with the discourse-initial marker yinwei (“because”) without suoyi (“so”) being the lowest (4.1%). On the other hand, the frequency with which the Chinese native speakers use to sequence information at the discourse level is highest (51.2%) in the correlative connectors yinwei/suoyi (“because/so”), followed by the interclausal conjunction suoyi (“so”) (41.9%), and then the inter-clausal conjunction yinwei (“because”) (4.7%), with the single discourse-initial marker yinwei (“because”) being the lowest (2.3%).

Based on the comparative performance data in Table 13, the use of the correlative discourse marker yinwei/suoyi (“because/so”) by the Chinese native speakers appears to be significantly higher in the DT (51.2%) than in the SCT (32.4%). Additionally, the Chinese native speakers at the discourse level appear to use correlative connectors (51.2%) much more often than the inter-clausal conjunction suoyi (“so”) (41.9%), but their frequency of use in these two linguistic pat-terns levels off in the SCT (32.3% vs. 33.3%). The possible reason for this disparate use has been

provided in the preceding section. To recapitulate, Chinese native speakers in extended discourse would tend to use discourse-initial yinwei (“because”) as a guidepost for the main point to come, which is echoed by another discourse marker suoyi (“so”) to signal mutual relationship, but such a discourse function would not be called for in the SCT which involves only a limited discourse scope. Moreover, the interrelated discourse functions of guidepost and echo, as respectively sig-naled by yinwei (“because”) and suoyi (“so”), accounts for the extremely low frequency of use in the Chinese native speakers’ sentence (4.1%) and discourse (2.3%) data: i.e. it sounds abrupt in Chinese discourse to invoke a relevance/guidepost marker yinwei (‘because”) without a subsequent echoing marker suoyi (“so”) to signal the interrelatedness of the two elements being linked.

Another point worthy of note is the Chinese speakers’ distinctive use of the interclausal con-junction suoyi (“so”) and the interclausal concon-junction yinwei (“because”) in the DT. As aforemen-tioned, in English discourse, an interclausal “because” will be preferentially chosen by English native speakers. However, as clearly indicated in Table 13, the Chinese native speakers rarely use the interclausal yinwei (“because”) (4.7%) in the DT, but predominantly select the interclausal

suoyi (“so”) (41.9%) to sequence information. This is because Chinese often uses the interclausal

conjunction suoyi (“so”) to connect a following main clause (MC) in a complex sentence which involves a sequence of cause and effect, thus observing the Principle of Temporal Sequence (PTS) as noted in sentence (a). Unlike English, Chinese less often uses the interclausal conjunction

yin-wei (“because”) to connect a subordinate clause (SC) to reflect an effect-to-cause sequence at

sen-tence level, as indicated in sensen-tence (b).

(a) Yinwei Xiaozhang bing-le, suoyi bu lai shang-ke le. Because little Zhang sick so not come attend-class Ptcl “Because little Zhang is sick, he won’t come to the class.”

CAUSE EFFECT (SC–MC)

(b) Xiaozhang bu lai shang-ke le, yinwei bing-le. Xiaozhang not come attend-class Ptcl because sick Ptcl “Little Zhang won’t come to the class, because he is sick.”

EFFECT CAUSE (MC–SC)

This result further attests to Kirkpatrick’s (1991) contention that the unmarked SC—MC se-quence in Chinese complex sentences is also a fundamental principle for sequencing information in Chinese discourse.

On the other hand, the Chinese native speakers generally level off in the use of correlative markers yinwei/suoyi (32.33%), the interclausal conjunction suoyi (33.33%), and the interclausal conjunction yinwei (30.2%) at the sentence level. This is only natural since sentences as such are without a context, and the Chinese native speakers would presumably be more or less subject to random choices among the three linguistic patterns.

Thus, based on the results of the findings in this study, the Chinese native speakers’ prefer-ences for sequencing information can be summarized in the following four patterns.

1. The Chinese native speakers are more apt to opt for the correlative markers yinwei/suoyi (“because/so”) to signal interrelatedness in a more extended discourse environment. 2. The Chinese native speakers tend to use the interclausal conjunction suoyi (“so”) more

of-ten than the interclausal yinwei (“because”), observing the unmarked SC—MC discourse convention (originating from the PTS).

3. The Chinese native speakers seldom invoke a discourse-initial marker yinwei (“because”) without being followed by an echoing discourse marker suoyi (“so”).

4. The Chinese native speakers either use the correlative connectors yinwei/suoyi (“be-cause/so”), the interclausal conjunction yinwei(“because”), or the interclausal conjunction

suoyi (“so”) in a complex sentence in which there is no obvious context and the discourse

6.3.3 The consistent behavior of the CSL group at the two different task types

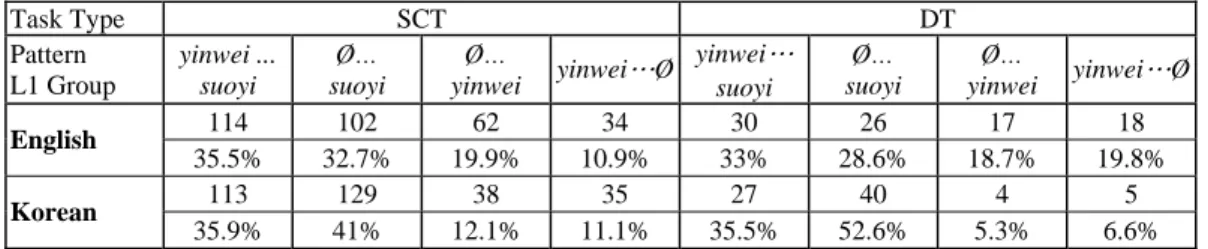

This section will compare the two CSL groups’ linguistic behavior at the two task types with that of the Chinese native speakers. The percentage of the different options in sequencing informa-tion by the English and Korean CSL learners are summarized in Table 14.

Task Type SCT DT Pattern L1 Group yinwei ... suoyi Ø… suoyi Ø… yinwei yinwei…Ø yinwei… suoyi Ø… suoyi Ø… yinwei yinwei…Ø 114 102 62 34 30 26 17 18 English 35.5% 32.7% 19.9% 10.9% 33% 28.6% 18.7% 19.8% 113 129 38 35 27 40 4 5 Korean 35.9% 41% 12.1% 11.1% 35.5% 52.6% 5.3% 6.6%

Table 14: Consistent patterns of information sequencing used by the two CSL groups in the SCT and the DT

As indicated from Table 14, the English and Korean CSL learners generally behave consis-tently in both task types. For example, the English learners produce the highest frequency of use (35.5% and 33%) in the correlative discourse markers yinwei/suoyi (“because/so”) at both the SCT and DT, followed by the interclausal conjunction suoyi (“so”) in both task types (32.7% and 28.6%), with the interclausal conjunction yinwei (“because”) (19.9% and 18.7%) and the single discourse-initial yinwei (“because”) (10.9% and 19.8%) being the lowest in both task types. Addi-tionally, the Korean CSL learners produce the highest frequency of use in the interclausal conjunc-tio suoyi (“so”) in both the SCT and DT (41% and 52.6%), followed by the correlative connectors

yinwei/suoyi (because/so”) at both task types (35.9% and 35.5%), with the interclausal conjunction yinwei (“because”) (12.1% and 5.3%) and the single discourse-initial yinwei (“because”) being the

lowest in the rank in both task types (11.1% and 6.6%).

On the basis of the data summarized in Table 14 above, the two CSL groups generally do not appear to distinguish the discourse functions of the correlative markers yinwei/suoyi (“be-cause/so”) from their sentence-level use, unlike the Chinese speakers who show a discretional use of correlative connectors according to different task types at different linguistic levels. Addition-ally, both the English (10.9% vs.19.8%) and Korean (11.1% vs. 6.6%) CSL learners produce more of the single discourse-initial yinwei (without suoyi) than the Chinese speakers (4.1% vs. 2.3%). Based on these two findings, it is obvious that the CSL learners, especially the English learners, have not quite mastered the dual functions of the guidepost/echo in discourse, as signaled together by yinwei/suoyi, (“because/so”) but have tended to leave out the echoic marker suoyi (“so”) in both tasks types. Thus, as indicated by the results of data comparison [the comparison of the data] in Table 13 and Table 14, despite the fact that the English CSL learners appear to use significantly more of because-initial structure in both the SCT and DT (70.5% and 75%), a large number of it is of a problematic type, i.e. a discourse-initial yinwei (“because”) is inappropriately used without an accompanying suoyi, (“so”) leading to sentence anomaly, especially so at the discourse level (19.8%).

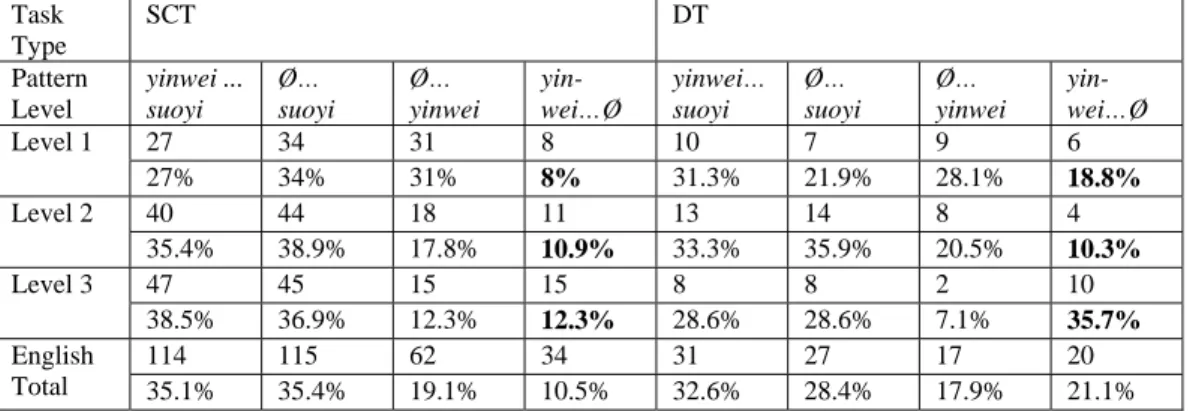

Additionally, such an anomalous use does not appear to decrease as their Chinese L2 profi-ciency increases, as indicated in Table 15 below. This may have resulted from the fact that “be-cause/so” do not function as correlative conjunctions in English. “Because” typically functions as a subordinating conjunction and is not accompanied by a correlative conjunction in another clause (Lay, 1975); Halliday & Hasan, 1976; Chen, 2002).

Task Type SCT DT Pattern Level yinwei ... suoyi Ø… suoyi Ø… yinwei yin-wei…Ø yinwei… suoyi Ø… suoyi Ø… yinwei yin-wei…Ø 27 34 31 8 10 7 9 6 Level 1 27% 34% 31% 8% 31.3% 21.9% 28.1% 18.8% 40 44 18 11 13 14 8 4 Level 2 35.4% 38.9% 17.8% 10.9% 33.3% 35.9% 20.5% 10.3% 47 45 15 15 8 8 2 10 Level 3 38.5% 36.9% 12.3% 12.3% 28.6% 28.6% 7.1% 35.7% 114 115 62 34 31 27 17 20 English Total 35.1% 35.4% 19.1% 10.5% 32.6% 28.4% 17.9% 21.1%

Table 15: Different patterns of information sequencing used by the English CSL learners

As can be seen from Table 15 (boldface), frequencies in both the SCT and DT types, the Level 3 (advanced) English learners (12.3% and 35.7%) appear to produce more of this anomalous type than the Level 1 (low intermediate) learners (8% and 18.8%) and the Level 2 (high intermediate) learners (10.9% and 10.3%). It is possible that the advanced English learners may experience a phenomenon termed fossilization or stabilization8 (Long, 2003). Thus, the interrelated discourse function of the correlative markers yinwei/suoyi (“because/so”) has posed a particular problem for the English learners9, irrespective of their Chinese L2 proficiency.

7 Implications

7.1 Theoretical implications

Theoretically, the present study has been set out to investigate the linguistic pattern of informa-tion sequencing in terms of typological transfer and L2 proficiency. The results of the findings as presented in this paper appear to lend further support to the idea that typological transfer is bidirec-tional. It also attests to previous research claims that L1 transfer appears primarily at the early stages of IL development and decreases chronologically as L2 proficiency increases.

7.2 Methodological implications

The methodological advantage of the present study lies in two areas. For one thing, it employs a cross-linguistic learner performance comparison to investigate the possible phenomenon of L1 transfer. For another, it includes tasks at two different linguistic levels. As has been pointed out by researchers (e.g. Felix, 1980; Meisel, 1983; Fakhri, 1994), the fact that a pattern occurs in both L1 and L2 writing does not constitute sufficient evidence that L1 transfer has taken place. Conversely, simply because the fact that L2 learners use significantly more of a target-like L2 pattern in their L2 writing does not automatically justify the argument that L1 transfer does not exist. It would take a cross-linguistic learner performance comparison to disentangle the mystery as to the exis-tence or non-exisexis-tence of an L1 transfer. As revealed by the statistical results based on the per-formance of the English and Korean CSL learners, L1 transfer does appear to occur in the English learners’ Chinese interlanguage.

Additionally, the inclusion of two tasks at different linguistic levels also reveals the Chinese native speakers’ discretional use of the correlative discourse markers yinwei/suoyi (“because/so”) between the sentence and discourse levels, and such a disparate use would have gone unnoticed if the research focus had been only directed at one linguistic level. Moreover, the fact that the Chi-nese native speakers frequently use a pair of correlative connectors in extended discourse envi-ronments to mark the dual function of guidepost and echo does not seem to be picked up by the

English and Korean CSL learners, who appear to have approached both task types in the same manner.

7.3 Pedagogical implications

The pedagogical purpose of the present research is to provide authentic information for CSL/CFL teachers and textbook writers in order to enable them to devise more effective methods and materials for teaching Chinese information sequencing. As indicated earlier, the Chinese speakers in the present study have different preferences for sequencing information in the sentence and discourse. Furthermore, as indicated in the raw data of the study, some Chinese speakers do not use any explicit connectors of either yinwei (“because”) or suoyi (“so) to convey the semantic relationship of cause and effect in the DT. These Chinese native speakers may opt to utilize con-textual or situational cues to convey their message coherently without overt cohesive ties. Such a use is considered natural and succinct by Chinese native speakers, as indicated by He (1994, p. 52), who provides the following example:

Ø Xiaozhang bing-le, Ø bu lai shangke le. Little Zhang sick not come attend-class Ptcl Because Little Zhang is sick, he can’t/won’t come to class.

However, Chinese sentences like the above without the use of either yinwei or suoyi, even in a complex sentence, can cause comprehension problems for CSL learners and even for young Chi-nese native-speaking children, who rely more on syntactic than semantic cues in processing a mes-sage (Chang & Cheng, 1988). Therefore, it is advisable to teach this particular pattern of informa-tion sequencing (i.e. one with zero conjuncinforma-tion) to the CSL learners only at a later stage of an in-structional continuum based on the principles of sequentiality and cumulativeness. It has been suggested that grammatical points should be properly sequenced and introduced to the learners, and that the sequence should be based on factors such as communicative frequency, structural and semantic complexities, pragmatic issues, L1/L2 transfer, and natural sequence (Teng, 1997, 2003).

Thus, based mainly on the factors of frequency occurrences, semantic complexity, and discourse considerations, a possible pedagogical presentation of Chinese information sequencing is outlined below in five cumulative stages with English CSL learners as the target group.

7.3.1 Cumulative stages of Chinese information sequencing Stage I:

In this initial stage, the English CSL learners are made aware of the fact that the correlative conjunctions yinwei/suoyi (“because/so”) are grammatically well-formed in Chinese (although ungrammatical in English). Learners at this stage are instructed to treat the correlative use of

yin-wei/suoyi as a rhetorical chunk and are advised not to omit either of the pair. Example 1. (a) Yinwei Xiaozhang bing-le, suoyi bu lai shang-ke le。

because little Zhang sick so not come attend-class (b) *Because little Zhang is sick, so he won’t come to the class.

Stage II:

In this stage, the English learners are introduced to the discourse function of yinwei/suoyi as a pair of markers in larger discourse context. Moreover, they are instructed that the discourse-initial marker yinwei (‘because’) can be omitted, especially at the sentence level.

Example 2. (a) Ø Xiaozhang bing-le, suoyi (ta) bu lai shang-ke le。 Little Zhang sick so he not come attend-class (b) Zhang is sick, so he won’t come to the class.

Stage III:

The English learners are introduced to the idea of markedness. That is, they are told that be-cause-medial information sequencing is possible but is a marked form in Chinese, although it is an unmarked one in the corresponding English.

Example 3. (a) Xiaozhang bu lai shang-ke le, yinwei (ta) bing-le。 Little Zhang not come attend-class, because (he) sick (b) Little Zhang won’t come to the class, because he is sick.

Stage IV:

In this stage, the English learners are instructed that in the pair of correlative conjunctions

yin-wei/suoyi (“because/so”), the interclausal echoic suoyi (“so”) cannot be omitted unless some

spe-cific constraints are met. For instance, when there is presence of a post-subject conjunction, con-junctive adverb jiu (‘then’), or negative marker bu (not).

Example 4. (a) ? yinwei Xiaozhang bing-le,Ø(ta) hui-jia qu le。 because little Zhang sick he return-home go ptcl.

(b) Xiaozhang yinwei bing-le, Ø hui-jia qu le。 (post-subject) Little Zhang because sick return-home go ptcl.

(c) Yinwei Xiaozhang bing-le, Ø(ta) jiu hui-jia qu le。 (conjunctive adverb) because little Zhang sick he then return-home go ptcl.

(d) Yinwei Xiaozhang bing-le, Ø bu lai shang-ke le。 (negative marker) because little Zhang sick not come attend-class ptcl.

Stage V:

The English CSL learners, at this final stage, are introduced to the notion of zero connectors in Chinese information sequencing.

Example 5. (a) Ø Xiaozhang bing-le,Ø bu lai shang-ke le。

little Zhang sick not come attend-class ptcl. (b) *Little Zhang is sick, won’t come to the class.

Throughout the stages in the instructional continuum, the target L2 Chinese patterns are juxta-posed against the corresponding English L1 patterns in order to raise the L2 learners’ metalingus-tic and crosslinguismetalingus-tic awareness. This follows an essential principle of Pedagogical Grammar: that is, the design of grammatical instruction is L1-L2 oriented (i.e. implemented against the L2 learn-ers’ L1) and relies on the use of contrastive analysis (Teng, 2003).

8 Conclusion

Functioning as a pair of correlative markers, yinwei/suoyi (“because/so”) is used in Chinese to contribute to the relevance and coherence of extended discourse. The discourse-initial marker

yin-wei (“because”) is employed by Chinese native speakers as a guidepost or relevance device for the

discourse to come, which is followed by the echoing marker suoyi (“so”) to signal mutual relation-ship in extended discourse. Based on the findings of this study, English CSL learners have gener-ally acquired the target-like because-initial information sequencing in their Chinese L2, as op-posed to preference for because-medial information in their English L1. Nevertheless, the correla-tive markers yinwei/suoyi (“because/so”), which are situated within the because-initial information sequencing to signal relevance in extended discourse, have not been taken up by the English CSL learners, nor by the Korean CSL learners, irrespective of their Chinese L2 proficiency.

Notes

1 The original version of this paper was presented at the Second CLS International Conference (CLaSIC

2006), December 7-9, 2006, Holiday Inn Atrium, Singapore.

2(因為)我於昨天晚上在收聽節目時,聽到一位剛從新加坡回去的小姐贈送新年禮物的消息,引起

我興趣,我希望能得到一份新年禮物,以及一張那位小姐的照片,可是由於粗心,沒有記住她的名字 ,望您多費心…….。

3

Wang’s (1997, 2002) spoken data yield a different picture. It has been found that only 23.3% of the casual clauses appear before their associated modified material (SC–MC), whereas 66.1% appear after those they modify (MC–SC). The results, however, are hardly surprising due to the highly interactive factors (e.g. immi-nence and spontaneity) inherent in conversation. In face-to-face interaction, it is often more effective prag-matically to first present the main point (MC), which is then followed by supporting statement (SC). By con-trast, in written discourse where there is more time for plannedness, the unmarked SC–MC sequence is natu-rally opted for. Thus, in face-to-face conversation, the predominant use of MC–SC sequence by Chinese na-tive speakers is a case of pragmatic conformity overriding structural conformity (Biq, 1995, p. 354).

4

Principal Branching Direction (PBD) is defined by Lust (1983, p. 138) as “the branching direction which holds consistently in unmarked form over major recursive structures of a language, where ‘major recursive structures’ are defined to include relative clause[s], adverbial subordinate clause and sentential complementa-tion.”

5

The English translations and semantic relationships provided in Figure 1 do not appear in the original tasks administered to the participants.

6

This result might have been in part due to the uneven number of potential occurrences of because-medial structure in the SCT and the DT. As mentioned in the section on Instruments, the SCT contains 12 target items to elicit because-medial structures (12 x 30 =360) in the English CSL learners’ L2 written production, whereas in the DT, there are only six pictures to elicit such use (6 x 30 =180). Hence, the number of opportu-nities to produce because-medial structure in the DT is only half the SCT. In addition, as opposed to the highly structured SCT, the DT requires that participants generate their own sentences, which might or might not yield the intended because-medial structure, thus further reducing potential number. In fact, the English and Korean CSL groups each produce a total of 62 (17.2%) and 38 (10.6%) tokens of because-medial struc-ture out of the potential 360 tokens in the SCT, but they only produce 14 (2.4%) and 4 (2.2%) tokens out of the 180 potential tokens in the DT.

7

大家聚餐之後正要回家,所以他去開車。機車騎士和朋友聊天,所以沒看到當時的路況。在倒車的 時候,由於轉角是個死角,他沒看到後面有一台機車,而機車也沒看到倒車的轎車,兩台車就因此撞 上了。

8

‘Fossilization’ or ‘stabilization’ refers to a process in which incorrect linguistic features become a perma-nent part of the way a person speaks or writes a language (Richards & Schmidt, 2002; Long, 2003).

9

Korean CSL learners appear to have fewer problems than the English CSL group with the correlative mark-ers yinwei/suoyi (“because/so”) in Chinese, presumably because they have a corresponding form in their L1, but such a correlative form is absent and considered ungrammatical in English (Halliday & Hasan, 1976).

References

Biq, Y-O. (1995). Chinese clausal sequencing and yinwei in conversation and press reportage. The Proceed-ings of the 21st Annual Meeting of the Berkley Linguistics Society (pp. 47–59). Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Linguistic Society.

Brown, P., & Levinson, C.S. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Chen, F.J. (2002). Correlative connectors in Chinese ESL/EFL writing: Intralingual or interlingual factors? Proceedings of the Nineteenth International Conference on English Teaching & Learning in the Republic of China. (pp. 101–106). Taipei: Crane Publishing Co.

Chen, F.J. (2006). Interplay between Forward and Backward Transfer in L2 and L1 Writing: The case of Chinese ESL Learners in the US. Concentric: Studies in Linguistics, 32(1), 147–196.

Chafe, W. (1984). How people use adverbial clause. In C. Brugman & M. Macauley (Eds.), Proceedings of the Tenth Annual Meeting of Berkeley Linguistics Society (pp. 437–450). Berkeley, CA: Berkeley Linguis-tics Society.

Chan, A.Y.W. (2004). Syntactic transfer: evidence from the interlanguage of Hong Kong Chinese ESL learners. The Modern Language Journal, 88(1), 56–74.